ABSTRACT

The transcription factor sex determining region Y-box 2 (SOX2) is required for the formation of hair cells and supporting cells in the inner ear and is a widely used sensory marker. Paradoxically, we demonstrate via fate mapping that, initially, SOX2 primarily marks nonsensory progenitors in the mouse cochlea, and is not specific to all sensory regions until late otic vesicle stages. SOX2 fate mapping reveals an apical-to-basal gradient of SOX2 expression in the sensory region of the cochlea, reflecting the pattern of cell cycle exit. To understand SOX2 function, we undertook a timed-deletion approach, revealing that early loss of SOX2 severely impaired morphological development of the ear, whereas later deletions resulted in sensory disruptions. During otocyst stages, SOX2 shifted dramatically from a lateral to medial domain over 24-48 h, reflecting the nonsensory-to-sensory switch observed by fate mapping. Early loss or gain of SOX2 function led to changes in otic epithelial volume and progenitor proliferation, impacting growth and morphological development of the ear. Our study demonstrates a novel role for SOX2 in early otic morphological development, and provides insights into the temporal and spatial patterns of sensory specification in the inner ear.

KEY WORDS: Otocyst, Inner ear, SOX2, Sensory, Specification, Cochlea, Mouse

Summary: The transcription factor SOX2 has a novel early role in promoting progenitor proliferation and in the growth and morphogenesis of the otocyst before its sensory-specific function during inner ear development.

INTRODUCTION

The mammalian inner ear labyrinth detects auditory and balance information via six sensory organs. These sensory regions comprise three fundamental cell types: the sensory hair cell, supporting cells and innervating neurons, which transmit auditory and balance information to the brain. Each sensory organ is housed in a nonsensory structure that facilitates the perception of hearing and balance. Examples include the coiled cochlea, which contains the sensory hearing organ (the organ of Corti), and the three semicircular canals, at the base of each is a sensory crista housed in a nonsensory ampulla, which is crucial for detecting rotational movements of the head (Harada, 1983).

Derivatives of the mature inner ear descend from a transient ectodermal thickening, or otic placode, which forms adjacent to the hindbrain at approximately E8.5 in the mouse (Noramly and Grainger, 2002). Subsequently the placode invaginates to form an epithelial sphere known as the otocyst (E9.0-E10), which expands dorsally to form the semicircular canals and ventrally to form the coiled the cochlea (Cantos et al., 2000; Morsli et al., 1998). The specification of sensory otic progenitors is thought to occur during otocyst stages (Groves and Fekete, 2012; Morsli et al., 1998). However, how and when the sensory progenitors are specified, or their relationship to their nonsensory counterparts, is not well established.

The HMG-box transcription factor sex determining region Y-box 2 (SOX2) is a member of the group B family of SOX transcription factors and marks several stem cell populations (Arnold et al., 2011; Avilion et al., 2003; Graham et al., 2003). SOX2/Sox2 is a core pluripotency gene (Boyer et al., 2005; Takahashi and Yamanaka, 2006) and is also required for numerous specific lineages during development (Bani-Yaghoub et al., 2006; Goldsmith et al., 2016; Graham et al., 2003; Que et al., 2009; Taranova et al., 2006). In the inner ear, SOX2 is required for sensory development (Dvorakova et al., 2016; Kempfle et al., 2016; Kiernan et al., 2005), and is widely used as a sensory progenitor marker (Dabdoub et al., 2008; Neves et al., 2013; Puligilla and Kelley, 2016). Moreover, SOX2 has been suggested to act upstream of the basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) factor atonal bHLH transcription factor 1 (ATOH1) (Kempfle et al., 2016), a factor both necessary and sufficient for hair cell development (Bermingham et al., 1999; Woods et al., 2004; Zheng and Gao, 2000). Several studies have shown that SOX2 is also important for the development of inner ear neurons (Ahmed et al., 2012b; Evsen et al., 2013; Neves et al., 2011; Puligilla et al., 2010; Steevens et al., 2017). However, despite the requirement for SOX2 in sensory development, its exact role is not well defined.

Here, using a fate-mapping and timed-deletion approach, we examine the spatiotemporal requirements of SOX2 in early inner ear development. We found that, consistent with Gu et al. (2016), SOX2 does not selectively mark the sensory progenitors at early otic time points, but rather contributes extensively to nonsensory tissues. Moreover, fate mapping revealed novel patterns of SOX2 expression, providing insights into sensory specification. Timed-deletion experiments from E8.5 to E12.5 revealed that early deletion of SOX2 severely impaired gross morphological development of the inner ear while preserving some sensory development, whereas later SOX2 deletions specifically impaired sensory formation. Fate mapping at otocyst stages demonstrated that the SOX2 expression dramatically shifted from a lateral to medial domain between E9.5 and E11.5. Analysis of early SOX2-deleted otocysts showed an important requirement for SOX2 in growth of the otic vesicle. Together, these data reveal a novel early role for SOX2 in nonsensory development in the inner ear, and provide insights into the patterns and timing of sensory specification.

RESULTS

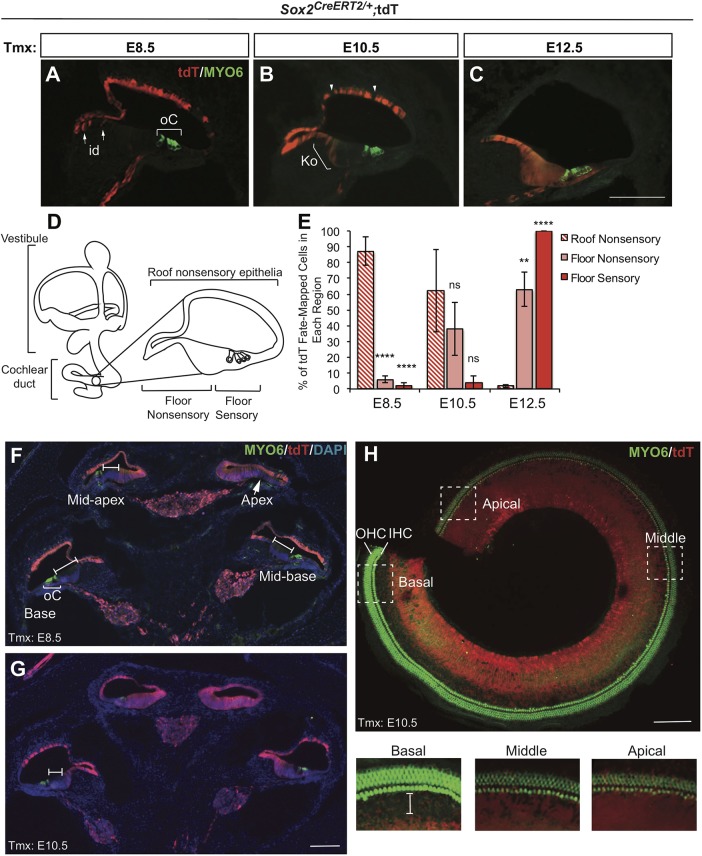

Early (E8.5-E10.5) tdT/SOX2 primarily fate-maps to nonsensory regions in the cochlea

To understand how SOX2 marks the sensory progenitors during ear development, we used a tamoxifen (Tmx)-inducible Cre recombinase system in the mouse to fate-map (Joyner and Zervas, 2006) SOX2 throughout ear development. The Sox2-CreERT2 line, which has been demonstrated to faithfully recapitulate SOX2 expression (Arnold et al., 2011; Gu et al., 2016), was crossed with a reporter line, ROSA26-CAGtdT, which expresses the fluorescent protein tdTomato (tdT) upon Cre induction (Madisen et al., 2010). We performed timed matings and Cre was induced in pregnant dams with intraperitoneal Tmx at either E8.5 (placode stage), E10.5 (otocyst stage) or E12.5 (late otocyst stage). Embryos were harvested at E18.5 and stained for hair cells (MYO6) and tdT, which reflects SOX2 expression at the time of injection (hereafter referred to as tdT/SOX2).

Surprisingly, we found that, at E8.5, tdT/SOX2 was excluded from the organ of Corti in most cochlear turns and from the sensory organ of Corti in the more middle and basal turns at E10.5 (Fig. 1A,B,E; E8.5: n=4, E10.5: n=4). In the analysis of the developmentally more mature basal region (Chen et al., 2002; Chen and Segil, 1999) at E8.5-E12.5, the domain of early SOX2 expression shifted over time from the nonsensory roof of the cochlea to the cochlear floor. Specifically, from E8.5 injections, tdT/SOX2 primarily mapped to the nonsensory roof of the cochlear duct, including stria vascularis and Reissner's membrane, with little cochlear floor expression except in the extreme apical regions (Fig. 1A,E, arrows). E10.5 injections showed that tdT/SOX2 expression was reduced in the nonsensory cochlear roof cells compared with E8.5 (Fig. 1B,E, arrowheads) and expanded in the nonsensory floor of the cochlea (Fig. 1B,E, bracket). By contrast, E12.5 tdT/SOX2 expression exclusively contributed to the floor of the cochlear duct, encompassing all sensory cells of the organ of Corti (Fig. 1C,E; n=3).

Fig. 1.

SOX2-expressing cells initially contribute to nonsensory regions in the cochlea but later contribute exclusively to the cochlear floor regions, including organ of Corti. (A-C) Cross-section through the E18.5 cochlea showing tdT/SOX2 expression and hair cell labeling (MYO6). (A) E8.5 tdT/SOX2-expressing cells primarily contributed to the roof of the cochlear duct with the exception of a few interdental (id) cells (arrows). oC, organ of Corti (bracket). (B) E10.5 tdT/SOX2 was downregulated in some cells in the roof of the cochlear duct (arrowheads), and expanded into the floor of the nonsensory cochlea, including the id cell region and some cells in Kölliker's organ (Ko, bracket). (C) By E12.5, expression of tdT/SOX2 was exclusively in the floor of the cochlea, including the oC. (D) Illustration of a cochlea cross-section with respect to the entire inner ear anatomy. (E) The area of nonsensory and sensory regions labeled by tdT/SOX2 was quantified. A trend is apparent, in which SOX2 initially contributes to the nonsensory regions, but switches over time to contribute exclusively to the floor of the cochlea. Comparison of roof nonsensory E8.5 tdT/SOX2 with E8.5 floor nonsensory tdT/SOX2: ****P<0.00001. Comparison of nonsensory E8.5 tdT/SOX2 with E8.5 sensory tdT/SOX2: ****P<0.00001. Comparison of roof nonsensory E12.5 tdT/SOX2 with E12.5 floor nonsensory tdT/SOX2: **P=0.004. Comparison roof nonsensory E12.5 tdT/SOX2 with E12.5 sensory tdT/SOX2: ****P<0.00001. Significance determined using a two-tailed Student's t-test. ns, not significant. Data are mean±s.e.m. (F-G) Midmodiolar regions in Sox2CreERT2/+ E18.5 control cochleae showed that the contribution of tdT/SOX2-expressing cells to the cochlea at E8.5 (F) and E10.5 (G) decreased along the apical–basal axis. At E8.5, tdT/SOX2 was largely excluded from the oC (bracket), with the exception of the apical domain, in which a much smaller negative floor region is observed (arrow) (F). At E10.5, tdT/SOX2 expression expanded along the cochlear floor but remained excluded from the oC in the middle and basal turns (I-bars) (G). (H) Whole-mount cochlea showed E10.5 tdT/SOX2 expression with respect to the sensory region. Boxed areas from different apical and/or basal regions are shown at a higher magnification below. In the apex, tdT/SOX2 was extensively expressed throughout the sensory region, but was gradually excluded more basally (I-bar). IHC, inner hair cell; OHC, outer hair cell. Scale bars: 100 µm.

Fate mapping of the sensory region of the cochlea (organ of Corti) reveals an apical-to-basal gradient of SOX2 expression

In E18.5 midmodiolar sections from samples injected at E8.5 and 10.5, a clear apical-to-basal gradient was observed in the extent of cochlear floor expression of tdT/SOX2 (Fig. 1F,H; E8.5, n=4; E10.5, n=4). At E8.5, tdT/SOX2 expression was largely excluded from the cochlear floor, including the organ of Corti, in all turns except the extreme apical region (Fig. 1F, brackets, arrow). By contrast, at E10.5, SOX2 was reported extensively in the cochlear floor in both apical turns, became more restricted to the interdental cell region and Kölliker's organ by the mid-basal turn, and was excluded from the organ of Corti in the base (Fig. 1G,H, bracket). These results show that as the cochlea developed, SOX2 expression shifted from the nonsensory cochlear roof, including Reissner's membrane and stria vascularis, to the cochlear floor, including nonsensory regions, such as interdental cell regions and Kölliker's organ as well as the organ of Corti. By E12.5, tdT/SOX2 expression almost exclusively mapped to the cochlear floor, including the organ of Corti, in all turns, although tdT/SOX2 expression was still absent or reduced in the lateral region of the floor of the cochlear duct. Interestingly, the apical-to-basal gradient of SOX2 expression between E8.5 and E12.5 in the organ of Corti mirrors the gradient of cell cycle exit observed in this sensory region (Chen et al., 2002; Chen and Segil, 1999).

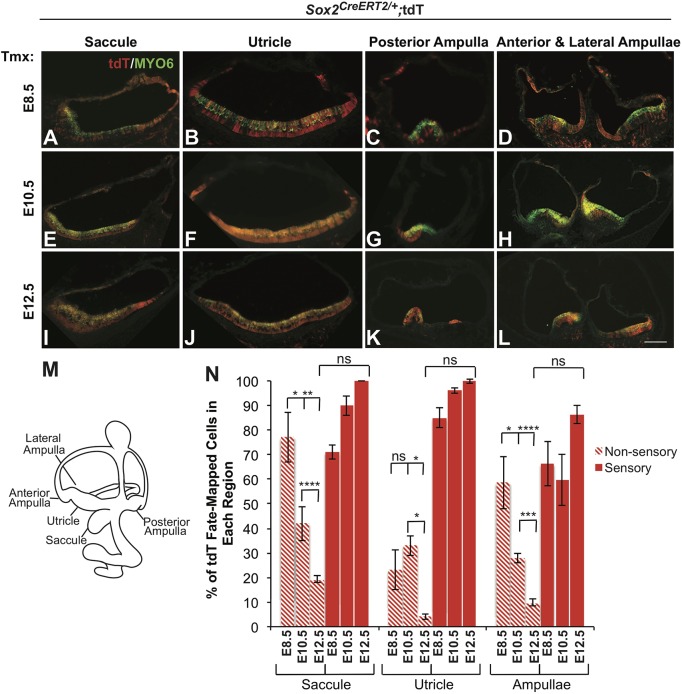

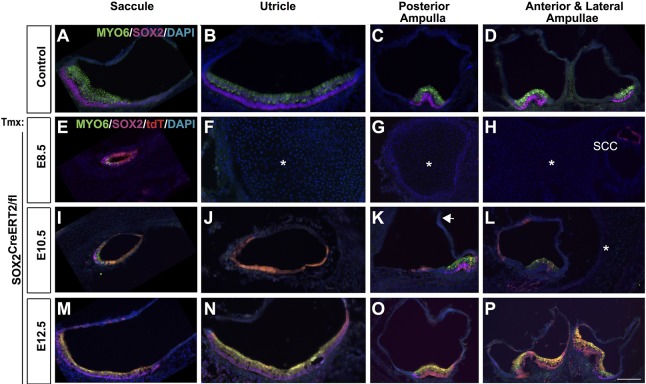

Early (E8.5-E10.5) SOX2 fate-maps to both sensory and nonsensory regions in the vestibule

We next analyzed tdT/SOX2 expression in the vestibule, and found that early SOX2 contributes to both nonsensory and sensory regions. At E8.5, tdT/SOX2 contributed to a greater extent to nonsensory regions in the saccule than to the sensory region (Fig. 2A,N; n=4), whereas, in the utricle, it contributed predominantly to the sensory macular region (Fig. 2B,N; n=4). In the ampullae, tdT-positive cells were scattered throughout both sensory and nonsensory regions (Fig. 2C,D,N; n=4). Additionally, SOX2 expression was extensively reported in the semicircular canals [not shown (Gu et al., 2016)]. The pattern of fate-mapped tdT/SOX2 described for the E8.5 time point was similar at E10.5; however, the degree to which SOX2 contributed to the nonsensory regions decreased, and tdT became more focused in the sensory organs (Fig. 2E-H,N; n=4). By E12.5, tdT/SOX2 was almost exclusively confined to the sensory regions (Fig. 2I-N; n=3).

Fig. 2.

SOX2-expressing cells contribute initially to both sensory and nonsensory regions in the vestibule, but later are specific to the sensory regions. (A-L) Cross-sections through the E18.5 vestibular regions showing tdT/SOX2 expression and hair cell labeling (MYO6). (A-D) E8.5 tdT/SOX2-expressing cells (red) contributed widely to both nonsensory tissue and sensory regions (marked by MYO6, green). (E-H) The extent of E10.5 tdT/SOX2-expressing cells marking nonsensory tissue was reduced, and more cells contributed to the sensory regions. (I-L) E12.5 tdT/SOX2 fate-mapped cells almost exclusively contributed to the sensory regions in the vestibule. (M) Illustration of the vestibular regions shown in cross-section. (N) Quantification of the area of tdT/SOX2 expression in nonsensory and sensory regions over time showed a substantial contribution of SOX2 to vestibular nonsensory regions that decreased over time; by contrast, labeling in the sensory regions increased over time and became specific to these regions. No significant difference was detected in sensory tdT/SOX2 in the vestibule over time. Comparison of nonsensory tdT/SOX2 in the saccule: E8.5-E10.5, *P<0.05; E8.5-E12.5, **P<0.001; E10.5-E12.5, ****P<0.0001. Comparison of nonsensory tdT/SOX2 in the utricle: E8.5-E10.5, ns; E8.5-E12.5, *P<0.05; E10.5-E12.5, *P<0.05. Comparison of nonsensory tdT/SOX2 in the ampullae: E8.5-E10.5, **P<0.001; E8.5-E12.5, ****P<0.0001; E10.5-E12.5, ***P<0.001. Significance determined using a two-tailed Student's t-test. Data are mean±s.e.m. ns, not significant. Scale bar: 100 µm.

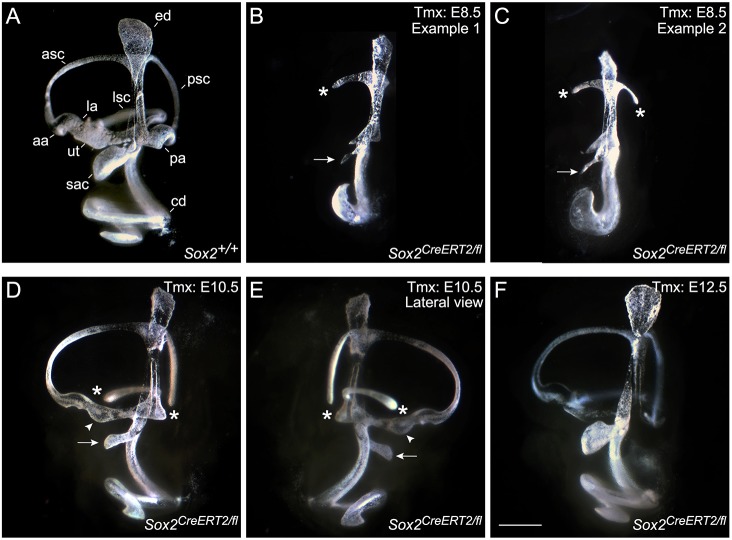

Early (E8.5-E10.5) deletion of SOX2 leads to severe morphological defects in the inner ear but retains some sensory development

We next investigated the functional significance of the changes in SOX2 expression using a timed-deletion approach. Specifically, we deleted Sox2 at particular time points (E8.5, E10.5 and E12.5) using Sox2-CreERT2-inducible Cre and a Sox2 conditional allele (Sox2fl/fl) (Shaham et al., 2009) to generate Sox2-deleted embryos (Sox2CreERT2/fl).

To visualize nonsensory development, inner ears were analyzed by paint filling (Kiernan, 2006) at E15.5 and sensory development was analyzed via cryosectioning at E18.5. The paint-filling analysis revealed a striking similarity between E8.5 Sox2-deleted mutant ears and Sox2Lcc/Lcc inner ears (Fig. 3B,C; n=6) (Kiernan et al., 2005), including a severely undercoiled cochlea, minimal canal development and rudiments of the macular regions (Fig. 3B,C). The E10.5 Sox2-deleted paint-filled inner ears demonstrated an intermediate phenotype, displaying significantly more nonsensory development compared with E8.5 deletions. Interestingly, all semicircular canals formed, although the lateral (4/4), and sometimes posterior cristae and ampullae (3/4) were missing. A smaller utricle and saccule were observed, and the cochlea was shortened by approximately a half turn (Fig. 3B,E; n=4). Despite the severe morphological phenotypes and in contrast to Sox2Lcc/Lcc mutants (Kiernan et al., 2005), some sensory formation occurred in all early-deleted Sox2 cochleae (Fig. 4E-G″; E8.5: n=4, E10.5: n=5), although the patterns were clearly abnormal. When hair cells were present, as in the more basal turns of the E8.5 and 10.5 mutants, SOX2 was also present, indicating that it is required for sensory development.

Fig. 3.

Paint-filling reveals a severe inner ear malformation resulting from the early deletion of SOX2, whereas later deletion has little effect on the overall morphology. (A-F) Paint-filled E15.5 inner ears with SOX2 deletion at indicated time points during development. Control (A) and two examples of E8.5 Sox2-deleted mutants (B,C) demonstrate severe loss of otic tissue caused by early loss of SOX2. (D,E) Medial and lateral views of an E10.5-deleted mutant show loss of the lateral and posterior ampullae, smaller maculae and an undercoiled cochleae. (F) Deletion of SOX2 at E12.5 did not show overt morphological defects. The smaller saccule (sac) is marked by an arrow (B-E), the utricle (ut) is marked by an arrowhead (D,E), missing ampullae or truncated canals are indicated by an asterisk (B-E). aa, anterior ampulla; asc, anterior semicircular canal; cd, cochlear duct; ed, endolymphatic duct; la, lateral ampulla; lsc, lateral semicircular canal; pa, posterior ampulla; psc, posterior semicircular canal. Scale bar: 500 μm.

Fig. 4.

Despite severe morphological defects in early Sox2-deleted cochlea, sensory development still occurs. (A) Time points for deletion (E8.5 or E10.5) and harvest (E18.5). (B-G″) Sections through midmodiolar regions of E18.5 ears. (B) Midmodiolar section in Sox2+/+ controls. The number of openings seen in cross-section reflects the length of the cochlear spiral. Loss of SOX2 at E8.5 (C) or E10.5 (D) resulted in shortened cochleae that still developed sensory regions in the more basal regions, although the patterning was abnormal. Sensory formation was abolished in more apical cochlear turns (arrows) in which SOX2 was deleted. Hair cells only formed where SOX2 was present in the otic epithelium (E-G″, magnification of boxed areas in C and D). Scale bars: 100 µm (in D, representing B-D); 50 µm (in F″, representing E-G″).

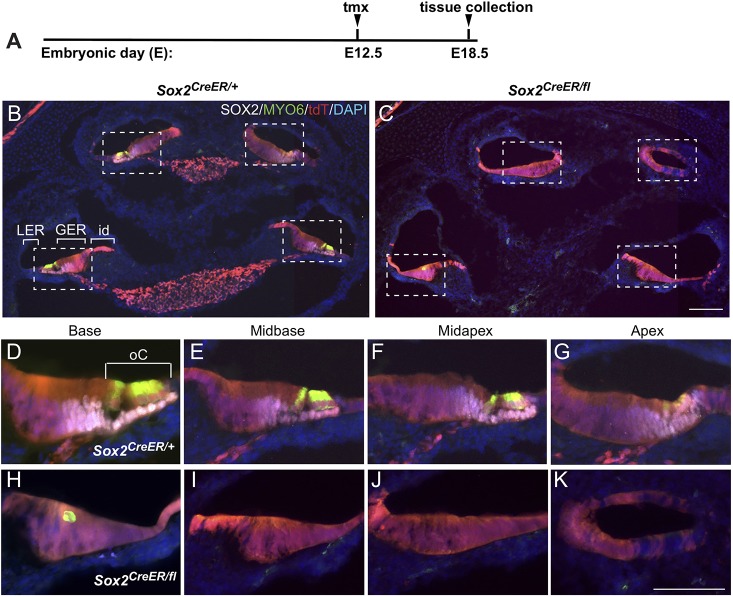

Later deletion (E12.5) of SOX2 has little impact on morphological development but severely affects sensory development in the cochlea

Analysis of the E12.5 Sox2-deleted inner ears by paint-fill showed no obvious malformations and appeared similar to controls (Fig. 3F; Sox2+/+ n=7, Sox2CreERT2/fl, n=4). However, sections showed that deletion at E12.5 resulted in cochleae (Fig. 5C; n=4) that were completely devoid of an organ of Corti in all four turns (Fig. 5H-K), with the exception of a few aberrant myosin VI (MYO6)-positive cells in the basal turn (Fig. 5C,H). Despite the absence of hair cells and supporting cells, the morphology of the cochlear floor appeared relatively normal in the E12.5-deleted mutants, with thickened regions corresponding to the location of the greater epithelial ridge and thinner regions to the interdental and lesser epithelial ridge regions (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Later deletion of SOX2 severely impairs sensory development in the cochlea but has little impact on cochlear morphology. (A) Time point for deletion (E12.5) and harvest (E18.5). (B) Low power section through the midmodiolar region of a Sox2CreER/+ control at E18.5 shows that E12.5 tdT/SOX2 contributed exclusively to the floor of the cochlear duct in all turns, overlapping with the normal SOX2 protein expression in the supporting cells (white). (C) Section through an E12.5 Sox2-deleted mutant shows relatively normal cochlear morphology but an absence of sensory formation. The missing ganglia in the mutant (tdT labeled in the modiolus in B, marking SOX2-expressing glia at E18.5) probably occurred because of the missing sensory regions, given that it was present earlier at E14.5 (not shown). Magnification of the cochlear turns from the boxed areas in control (D-G) and E12.5-deleted Sox2 mutant (H-K) show the absence of the organ of Corti in all turns, with the exception of an occasional abnormally shaped MYO6-positive cell in the basal turn (H). GER, greater epithelial ridge; id, interdental cell area; LER, lesser epithelial ridge; oC, organ of Corti. Scale bars: 100 µm (in C, representing B,C); 50 µm (K, representing D-K).

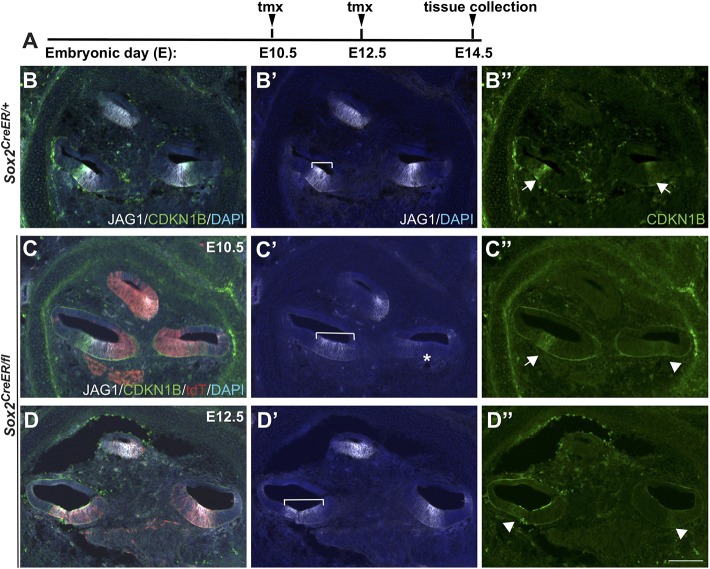

Marker analysis in the cochlea indicates that SOX2 is required for both prosensory specification and sensory cell differentiation

The lack of sensory development in the cochlea was interesting because it was unclear whether it was the result of a failure in sensory specification or differentiation, given that SOX2 has been implicated in both processes. To distinguish these possibilities, we deleted SOX2 at both E10.5 and E12.5 and analyzed prosensory markers at E14.5 (Fig. 6A), including the Notch ligand Jagged 1 (JAG1) and the cell cycle inhibitor, cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1B (CDKN1B). JAG1 has previously been shown to be required for prosensory development (Brooker et al., 2006; Kiernan et al., 2001, 2006) and CDKN1B is a widely used prosensory marker. Although CDKN1B is initially expressed apically at E12.5, by E14.5 it demonstrates stronger expression basally and we did not reliably detect expression in the apex (Chen and Segil, 1999). In E10.5 Sox2-deleted mutants, JAG1 and CDKN1B were present in the basal turn, although the domain appeared expanded and mildly weaker (Fig. 6C′, bracket, arrow; Sox2CreERT2/fl n=3). By contrast, in the middle turn, both JAG1 and CDKN1B were almost undetectable (Fig. 6C′,C″, asterisk and arrowhead). Intriguingly, when SOX2 was deleted at E12.5, JAG1 was expressed similar to control levels in all cochlear turns (Fig. 6D′, bracket; Sox2+/+ n=5, Sox2CreERT2/fl n=3). However, CDKN1B was downregulated in E12.5-deleted cochleae compared with controls (Fig. 6D, D″, arrowheads). These results suggest that, based on JAG1 expression, prosensory specification is altered in the middle turn by deleting SOX2 at E10.5, but largely unaffected by deletion at E12.5. Thus, the lack of sensory formation in the E12.5-deleted inner ears is probably because of the failure of differentiation.

Fig. 6.

Marker analysis in the cochlea indicates that SOX2 is required for both prosensory specification and sensory cell differentiation. (A) Time points for deletion (E10.5 or E12.5) and harvest (E14.5). (B-B″) Control E14.5 midmodiolar region shows typical expression of JAG1 and CDKN1B (marking the future organ of Corti). Unlike JAG1, CDKN1B expression was not always present in control cochlea in the apex. (C-C″) Representative sections of a midmodiolar region of E14.5 cochlea after deletion at E10.5, with indicated prosensory markers and tdT, reflecting SOX2 expression at E10.5. JAG1 expression was mildly expanded in the basal turn of the cochlea (compare brackets in C′ and B′ control) and was significantly downregulated from the middle turn (asterisk) (C′). The shifted JAG1 expression in the apical domain was frequently observed in controls, probably because of a difference in the plane of sectioning rather than a shifted domain. CDKN1B expression was also downregulated in the middle turn (arrowhead) (C″). (D-D″) Representative section of an E14.5 midmodiolar cochlea deleted for SOX2 at E12.5. After deletion of SOX2 at E12.5, JAG1 expression was present in all turns, although, again, mildly expanded in the basal turn of the cochlea (compare bracket in D′ with B′ control). In the absence of SOX2 at E12.5, CDKN1B expression was significantly downregulated in both middle and basal turns (arrowheads) (D″). Arrows and arrowheads indicate either the presence or absence of CDKN1B, respectively. Scale bar: 100 µm.

Early SOX2 is important for both nonsensory and sensory formation in the vestibule

Analysis of E8.5 SOX2-deleted vestibular development by immunohistochemistry showed near-complete vestibular agenesis. The only exception was a small saccule (Fig. 7E; Sox2CreERT2/fl n=4), which contained a few MYO6-positive cells in which SOX2 was still present (Fig. 7E). Other structures, including utricle, maculae, ampullae, cristae and most of the semicircular canals, were completely lacking (Fig. 7F-H), confirming the paint-filling analysis (Fig. 3). Analysis of E10.5-deleted vestibular regions demonstrated an intermediate phenotype that varied between samples in the extent of the morphological deficit (Fig. 7I-L; Sox2CreERT2/fl n=5). Significantly more of the vestibule formed compared with the E8.5 deletion; however, some structures were smaller or sometimes absent. Specifically, the saccule was larger than the E8.5 deletion but still significantly underdeveloped and contained some sensory cells (Fig. 7I). Similarly, the utricle was larger than E8.5 but devoid of sensory cells (Fig. 7J). The posterior crista formed in some samples, but was often misshapen (Fig. 7K, arrow). In a few E10.5 Sox2-deleted samples, both the lateral and anterior cristae were missing (2/5) (not shown), but in all mutants analyzed, the lateral crista was consistently missing (5/5) (Fig. 6H, L). By contrast, although the fate-mapping results showed that, by E12.5, SOX2 expression was specific and widespread in the vestibular sensory regions at E12.5 (Fig. 2), loss of SOX2 expression at this time did not lead to detectable sensory or structural defects in the vestibule (Fig. 6M-P; Sox2CreERT2/fl n=4).

Fig. 7.

Early SOX2 deletion results in both nonsensory and sensory loss in the vestibule, whereas later deletion has few effects on the vestibular regions. (A-D) Sections through the vestibular organs of an E18.5 control. Sensory regions are marked by MYO6 (hair cells) and SOX2 (supporting cells). (E-H) In the absence of SOX2 at E8.5, the vestibule largely failed to form, with the exception of a very small saccule (E), which contained a few MYO6- and SOX2-positive cells. Asterisks indicate missing vestibular sensory organs (F-H). (I-L) The vestibule from E10.5 deletion resulted in a significantly underdeveloped saccule (J), a smaller utricle devoid of sensory formation (K), a posterior crista lacking an ampulla and fused to the common crus (arrow), and a missing anterior crista and ampulla (asterisk) (L). (M-P) Deletion of SOX2 at E12.5 did not produce an overt phenotype in any of the vestibular organs. SCC, semicircular canal. Scale bar: 100 µm (in P, representing A-P).

To further understand the loss of canal development in the E8.5 Sox2-deleted inner ears, we examined otocysts earlier at E11.5 using JAG1 to examine sensory development and at E12.5 to examine semicircular canal development by paint filling (Fig. S1). Results of the E11.5 analyses showed that the Sox2-deficient otic epithelium was markedly thinner than in controls in both the sensory and nonsensory regions (Fig. S1A-D; Sox2+/+ n=6, Sox2CreERT2/fl n=6). JAG1 expression was consistently absent in the dorsal posterior region, whereas weak JAG1 expression could be detected in the anterior dorsal region (Fig. S1D,D′; arrowheads). Paint-filling results at E12.5 revealed outpockets of the canal despite the severe canal agenesis at E15.5 (Fig. S1F,H) in the E8.5 SOX2-deleted mutants, although the overall size of the canal pouches was smaller (Fig. S1F,H, small arrowheads; Sox2+/+n=4; Sox2CreERT2/fl n=6). Canal fusion was observed consistently in the mutant anterior canal, but was not present in the posterior and lateral canal regions (Fig. S1F,H, arrows). These results indicate that canal genesis initiates in E8.5 Sox2-deleted otocysts, but subsequently fails, probably because of insufficient numbers of cells for canal formation or loss of canal-specific gene expression. Similar smaller canal outpockets and lack of fusion at E12.5 have been reported for CHD7 mutants that also resulted in canal truncations and ablations (Hurd et al., 2007; Kiernan et al., 2002).

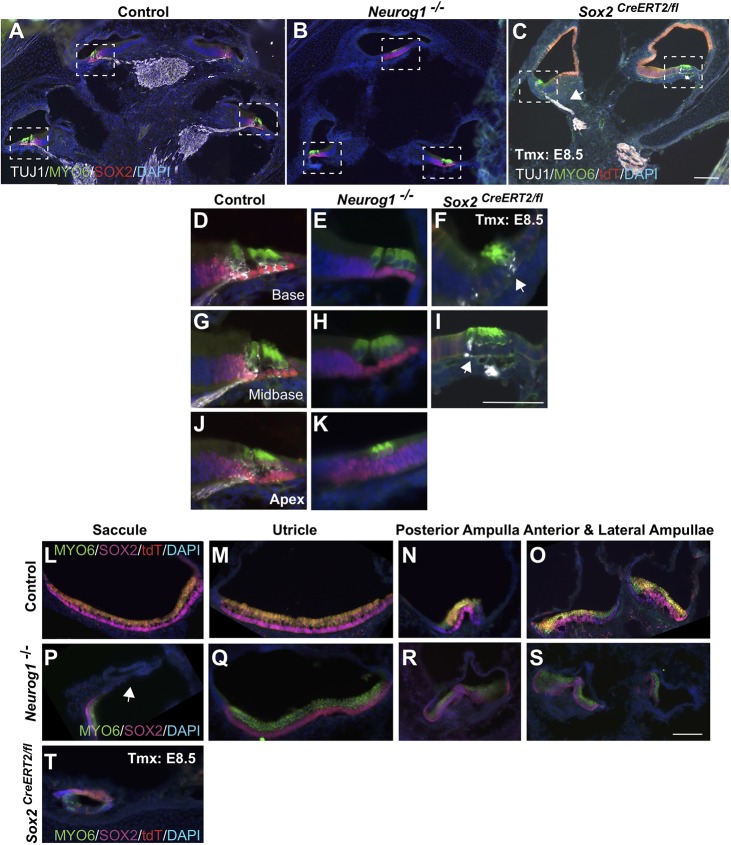

Analyses of NEUROG1-deficient ears indicate that the nonsensory defects are not caused secondarily by reductions in the otic ganglion

Cochlear morphogenesis is influenced by secreted factors from the otic neurons (Bok et al., 2013), including sonic hedgehog (SHH). Given that early SOX2 is also an important factor for inner ear neurons (Ahmed et al., 2012b; Evsen et al., 2013; Neves et al., 2011; Puligilla et al., 2010; Steevens et al., 2017), it is conceivable that the severe morphological defects observed in the E8.5-deleted SOX2 mutants arose secondarily from reductions in the otic ganglia. To investigate this possibility, we compared the phenotype of the E8.5 Sox2-deleted mutants with neurogenin 1 (Neurog1)−/− ears, in which the otic ganglia does not form (Ma et al., 2000, 1998). E18.5 Neurog1−/− and E8.5 Sox2-deleted ears and controls were analyzed using sensory markers (MYO6 for hair cells and SOX2 for supporting cells) and the neuron-specific class III beta-tubulin (TUJ1) to label otic neurons. NEUROG1-deficient cochleae, although undercoiled compared with controls (Fig. 8A,B; Neurog1+/+ n=2, Neurog1−/− n=3), were significantly more developed than E8.5 Sox2-deleted ears, despite some otic ganglia still forming in the E8.5-deleted SOX2 mutants (Fig. 8C,F,I, arrows). Additionally, sensory formation occurred relatively normally in the NEUROG1-deficient cochleae, with most regions showing recognizable inner and outer hair cell patterns (Fig. 8E,H,K) (Ma et al., 2000), whereas sensory formation was aberrant in the E8.5-deleted SOX2 mutant cochleae (Fig. 8F, I).

Fig. 8.

Analysis of NEUROG1-deficient ears indicates that the nonsensory defects are not caused secondarily from reductions in the otic ganglion. (A-C) Low-power midmodiolar sections from control (A), Neurog1−/− (B) and E8.5 Sox2-deleted cochleae (C). The nonsensory phenotype was more severe in the absence of E8.5 SOX2 than of NEUROG1, and some neuronal formation still occurred [arrows mark neuronal expression (TUJ1; white) in C,F,I]. (D-K) Higher magnification views of the boxed regions in A-C highlight that sensory formation occurred fairly normally in the Neurog1-deficient mutant. (L-T) Examples of cross-sections through each vestibular organ in control (L-O), Neurog1−/− mutant (P-S) and E8.5 SOX2-deleted inner ears (T). The vestibule forms relatively normally in Neurog1-deficient mutants, with the exception of a smaller saccule devoid of sensory markers (arrow, P). By contrast, the only vestibular structure seen in E8.5 SOX2-deficient inner ears was an underdeveloped saccule (T). Scale bars: 50 µm.

The vestibule also showed a striking difference between Neurog1−/− and E8.5 Sox2-deleted ears. In the absence of NEUROG1, the cristae and utricle developed comparably with those of the control (Fig. 8L-O; Q-T); however, the NEUROG1-deficient saccule was significantly smaller and contained no hair cells (Fig. 8P, dotted lines). Interestingly, the size of the NEUROG1-deficient saccule was similar to the E8.5 SOX2-deficient saccule, although the latter contained a few sensory cells. These results indicate that the severe morphological defects in the early Sox2-deleted inner ears do not result secondarily from reductions in the otic ganglia.

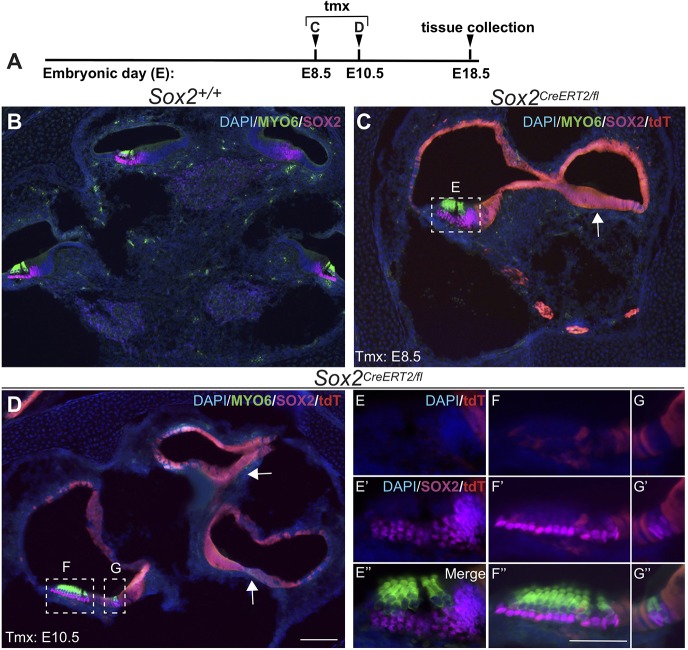

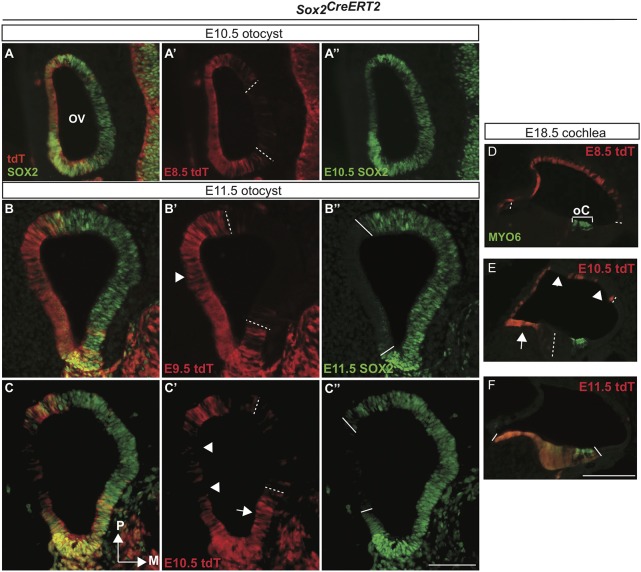

Simultaneous fate mapping and expression of SOX2 demonstrate a dynamic shift in otic expression between E8.5 and E11.5

Given that the fate mapping and timed-deletion analysis at E18.5 indicated that SOX2 was expressed in different progenitor populations during development, we analyzed both SOX2 lineage and protein expression during otocyst stages to correlate otocyst domains with later inner ear lineage domains. Cre was induced at E8.5, E9.5 or E10.5, and embryos were harvested at either E10.5 or E11.5, and examined for expression of tdT/SOX2 (representing past SOX2 expression at Cre-induction time points) or current SOX2 expression, using SOX2 antibodies. At E8.5-E9.5 inductions, we observed tdT/SOX2 expression broadly along the lateral wall of the otocyst, extending anteriorly to posteriorly, (Fig. 9A′,B′; Sox2CreERT2 n=9), a region previously associated with nonsensory formation (Abelló et al., 2010; Kiernan et al., 1997; Raft et al., 2004). Surprisingly, after 48 h, between E10.5 and E11.5, the mainly lateral domain of SOX2 protein expression switched dramatically to the medial region of the otocyst, with little overlap between the two (Fig. 9A″, B″; Sox2CreERT2 n=5). Taken together, early SOX2 fate-mapping results showed that the lateral domains of the otocyst contribute mainly to nonsensory inner ear structures, and that SOX2 labels largely different progenitor populations between E9.5 and E11.5. The mechanism for this shift is unclear; however, the ear undergoes dramatic morphological changes between E8 and E11, given that the ear is changing from a placode to spherical otocyst. Thus, changes in the otic apposition to the ectoderm or neural tube might mediate changes in SOX2 domains during this time.

Fig. 9.

Simultaneous fate mapping and expression of SOX2 demonstrate a dramatic shift from nonsensory to sensory progenitors in the otocyst between E8.5 and E11.5. (A-C″) Sections at indicated ages demonstrating previous fate-mapped SOX2 expression (tdT; red) versus current SOX2 expression (green). The SOX2 expression domain switched from a lateral, primarily nonsensory associated tdT/SOX2 domain at E8.5/E9.5 (A-B′) to a medial, sensory-associated domain of SOX2 protein expression at E11.5 (A″,B″,C″). (B′) The contribution of E9.5 SOX2-expressing cells labeled by tdT/SOX2 decreased in the lateral otocyst (arrowhead), and increased medially (B″). At E10.5, the contribution of tdT/SOX2 to nonsensory progenitors in the cochlear roof decreased (arrowheads in C′ and E) and began to contribute to cochlear floor nonsensory progenitors (arrows in C′ and E). (D-F) Demonstration of how the pattern of early SOX2 expression in the otocyst contributes to the mature cochlea. The region in the posterior medial otocyst negative for tdT/SOX2 tdT early on (dashed lines in A′,B′,C′) probably contributes to the future organ of Corti (bracket in D), which was positive by E11.5 (solid lines in B″,C″,F). M, medial; OV, otic vesicle; P, posterior. Scale bars: 100 µm.

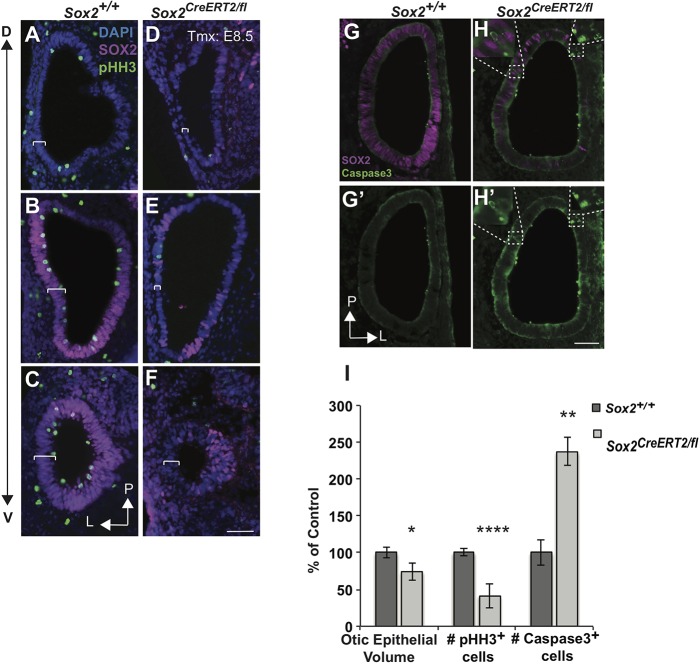

SOX2 is required for otic growth, progenitor proliferation and survival

Given the thinner otic epithelium observed at E11.5 (Fig. S1B) and the known role of SOX2 in proliferation and viability in several different systems (Arnold et al., 2011; Cavallaro et al., 2008; Ferri et al., 2004; Goldsmith et al., 2016; Graham et al., 2003; Hagey and Muhr, 2014; Que et al., 2009; Takahashi and Yamanaka, 2006), we assessed the possibility that SOX2 has similar roles in the early otocyst. Short-harvest experiments were performed in which Cre was induced at E8.5 and tissue was harvested at E10.5. The Sox2-deficient otic epithelium appeared thinner (Fig. 10A-F, brackets) and quantification confirmed a significant reduction in volume of 26% compared with controls (Fig. 10I; Sox2+/+ n=15, Sox2CreER/fl n=12; P=0.04). To test whether a failure of proliferation could account for the smaller otocyst size, E10.5 Sox2+/+ and Sox2CreER/fl samples were analyzed using the mitotic marker phospho-Histone H3 (pHH3) (Hans and Dimitrov, 2001; Tapia et al., 2006). Results showed that the number of pHH3-positive cells in SOX2-deficient otocysts was 41% of control (Fig. 10I; Sox2+/+ n=9, Sox2CreERT2/fl n=6; P<0.0001). We also examined whether cell death contributed to the decreased otocyst size, using cleaved caspase 3 as a marker of cell death. Results showed increased cleaved caspase 3-positive cells in Sox2CreER/fl mutants compared with controls (Fig. 10G-H′,I; Sox2+/+ n=7, Sox2CreER/fl n=6; P=0.008). These results demonstrate a role for SOX2 in otic progenitor viability, as well as in promoting proliferation during otic growth.

Fig. 10.

SOX2 is required for otic growth and progenitor proliferation and/or viability. (A-F) Sections through E10.5 otocysts of a Sox2+/+ control (A-C) and an E8.5 Sox2CreERT2/fl mutant (D-F) showing a decrease in the proliferation marker pHH3 along the dorsoventral axis (D↔V) in Sox2-deficient mutants. Brackets indicate the thickness of the otic epithelium. (G-H′) The increase in cleaved caspase 3 in the E8.5 Sox2-deleted mutant. Insets show magnification of areas within dashed boxes that display caspase 3-expressing cells in areas where SOX2 was deleted. (I) Quantifications of the reductions in otic epithelium volume (Sox2+/+ n=15; Sox2CreERT2/fl n=12; *P<0.05), pHH3-expressing cells (Sox2+/+ n=9; Sox2CreERT2/fl n=6; ****P<0.0001) and a corresponding increase in caspase 3 (Sox2+/+ n=6; Sox2CreERT2/fl n=6; **P<0.01) in Sox2CreERT2/fl mutants after deletion at E8.5 compared with controls. Significance determined using a two-tailed Student's t-test. Data are mean±s.e.m. L, lateral; P, posterior. Scale bars: 100 µm.

Overexpression of SOX2 expands the number of otic progenitors

To further interrogate the role of SOX2 in the early otocyst, we analyzed the effects of overexpressing SOX2. To drive broad ectopic expression of SOX2 throughout early otocyst stages, we crossed FoxG1-Cre mice (Hbért and McConnell, 2000) with a line that overexpresses SOX2 under the ubiquitous Rosa26 promoter [Rosa26SOX2 (Lu et al., 2010)]. Inner ears were harvested at E10.5 and otocyst volume was quantified. We found that overexpression of SOX2 significantly expanded the volume of otic epithelium in both dorsal and ventral sections (Fig. S2B,B′, D,D′, brackets, 10E; FoxG1+/+ n=6, FoxG1-Cre;Rosa26SOX2 : n=8, P=0.02). Moreover, the number of pHH3 cells increased by ∼25% in FoxG1-Cre;Rosa26SOX2 samples (Fig. S2E; n=6; P=0.03), indicating that the otocyst volume increased through enhanced proliferation.

DISCUSSION

Our study demonstrates that the expression and function of SOX2 changes dramatically during inner ear development. As SOX2 was initially characterized as being expressed in the sensory regions and affecting sensory development (Dabdoub et al., 2008; Kiernan et al., 2005; Neves et al., 2007, 2012), it has been primarily viewed as a sensory marker. Our fate-mapping results demonstrated that, at early time points (E8.5-E9.5), SOX2 is expressed primarily in the lateral otocyst and contributes to nonsensory regions of the cochlea and vestibule, while also contributing to a smaller proportion of sensory cells throughout the vestibular regions and very apical cochlea. However, over a period of 24-48 h between E9.5 and E11.5, the domain of SOX2 dramatically shifts to the medial otocyst, where it contributes to the organ of Corti and sensory regions in the vestibule. Importantly, we showed by deleting SOX2 at different times that loss of the early lateral otic domain leads to severe dysmorphogenesis of the inner ear, while preserving some sensory development. By contrast, deletion of the medial domain of SOX2 at later otocyst vesicle stages leads to loss of the organ of Corti while largely preserving the normal morphogenesis of the inner ear. Our fate-mapping results, combined with deletion analyses, showed that the severe morphological defects caused by early deletion probably result from SOX2 expression in the lateral regions that contribute widely to nonsensory tissues. Our fate-mapping results also showed that SOX2 becomes localized to the organ of Corti in an apical-to-basal gradient, mirroring the gradient of cell cycle exit and not differentiation, and supporting a role for SOX2 in sensory specification. We further demonstrated that the severe effects on morphogenesis caused by early deletion of SOX2 lead to growth defects in the otocyst. Taken together, our results demonstrate a novel requirement for SOX2 in the growth of the otic vesicle that occurs before its role in sensory specification and differentiation.

Sox2 in sensory specification and differentiation

Between E8.5 and E12.5, we demonstrated that SOX2 expression shifts from the roof of the cochlea towards the floor in an apical-to-basal gradient, ultimately localizing in the organ of Corti and Kölliker's organ in all turns by E12.5. The organ of Corti demonstrates opposing gradients of cell cycle exit and differentiation, with terminal mitosis occurring apically to basally (Chen and Segil, 1999; Ruben, 1967), whereas differentiation occurs in a basal-to-apical gradient (Chen et al., 2002; Montcouquiol and Kelley, 2003). Thus, our SOX2 fate-map mirrors the gradient of cell cycle exit and not differentiation. Given that expression of SOX2 occurs several days before cell cycle exit, these results suggest that SOX2 promotes sensory specification and/or competence in these regions, similar to its role as a competence factor in different systems (Amador-Arjona et al., 2015; Taranova et al., 2006). Previously, SOX2 has been implicated in both sensory specification (Kiernan et al., 2005) and differentiation (Kempfle et al., 2016), in which it is proposed to act upstream of ATOH1, a transcription factor required for hair cell development (Bermingham et al., 1999). To dissect these potential roles, we deleted SOX2 at E10.5 and E12.5, and used the prosensory markers JAG1 and CDKN1B to assess specification in the cochlea. Results showed that JAG1 was only significantly downregulated in the E10.5 Sox2 deletion, and only in the middle turn. Whereas the expression of JAG1 in the E10.5-deleted basal domain is probably explained by incomplete deletion (Sox2-Cre is not yet expressed there), the continued presence of the JAG1 domain in the apical domain after E10.5 deletion, and in all turns after E12.5 deletion, indicates that SOX2 expression is only required for a short period of time for specification and/or competence. A different result was observed for CDKN1B, which was significantly downregulated at both E10.5 and E12.5. This might be because CDKN1B is directly downstream of SOX2, and any perturbation of SOX2 will also affect CDKN1B. In support of this possibility, it has been shown that SOX2 acts upstream of CDKN1B in neonatal supporting cells (Liu et al., 2012), and that CDKN1B is a direct target of SOX2 in immortalized otic progenitor cells (Kwan et al., 2015). CDKN1B also demonstrates an apical-to-basal gradient in the cochlea (Chen and Segil, 1999; Lee et al., 2006), supporting the idea that SOX2 regulates CDKN1B during organ of Corti development. However, SOX2 must also regulate other genes, because deletion of CDKN1B does not lead to loss of sensory specification (Chen and Segil, 1999).

SOX2 and the generation of the sensory regions

Our study provides a unique perspective of the generation of sensory organs and their respective dependence on SOX2 for development. It is interesting that, whereas SOX2 was almost completely excluded from the organ of Corti initially, SOX2 was expressed throughout the vestibular sensory regions at the earliest time points, albeit in a scattershot pattern. Within the vestibular sensory regions, SOX2 expression gradually increased over time and, by E12.5, was concentrated and specific to each vestibular sensory region. Previous studies of sensory specification using markers or transplantation have suggested that some sensory areas are specified before others (Morsli et al., 1998; Wu et al., 1998). By contrast, SOX2 fate mapping did not show any clear sequential expression, because some SOX2-positive cells were seen in all sensory areas, including the organ of Corti, starting at the earliest time points. Our results suggest an alternative model in which, rather than the organs being sequentially specified, sensory cells are added to each sensory region over time. A clear pattern exists in the organ of Corti in which SOX2-positive cells were initially localized to the apical regions and gradually are specified more basally, whereas the vestibular sensory regions showed no clear pattern, with SOX2-positive cells gradually increasing within each organ.

Early role of SOX2 in otic growth

Our gain- and loss-of-function results in the otocyst indicated that early SOX2 expression is important for the proliferation and viability of otic progenitors. Proliferation is a well-established role for SOX2 in several systems (Graham et al., 2003; Hagey and Muhr, 2014), and proliferation defects have been shown to result in abnormal inner ear morphogenesis (Kopecky et al., 2011; Matei et al., 2005). The mechanism through which SOX2 promotes proliferation is probably complex, because overexpression of SOX2 only resulted in a modest increase in dividing cells. However, SOX2 levels differentially influence proliferation in other systems (Hagey and Muhr, 2014); potentially, overexpression of SOX2 at a slightly lower level could have a more robust effect. Relatedly, SOX2 expression can be tightly regulated by signaling pathways (Cimadamore et al., 2013; Ormsbee Golden et al., 2013; Rizzino, 2013) in addition to components of the cell cycle (Julian et al., 2013); thus, feedback mechanisms might limit the extent of an overexpression approach.

The role of SOX2 in regulating inner ear development

We and others have established that SOX2 has multiple roles in inner ear development, including neural specification (Evsen et al., 2013; Puligilla et al., 2010; Steevens et al., 2017), sensory specification (Kiernan et al., 2005; this paper) and sensory differentiation (Dabdoub et al., 2008; Kempfle et al., 2016). Here, we provide evidence of a novel early role for SOX2 in nonsensory growth and formation of the ear, induced by a dramatic switch from primarily nonsensory to sensory expression during early otic development. At present, it is unclear how SOX2 achieves all these different functions. One possibility might lie in the pioneering ability of SOX2 to bind condensed chromatin and recruit different transcription factors (Amador-Arjona et al., 2015; Reiprich and Wegner, 2014; Sarkar and Hochedlinger, 2013; Zhou et al., 2016). Specifically, it has been shown that SOX proteins have the ability to ‘bend’ DNA, thereby allowing DNA access to other proteins (Ferrari et al., 1992; Scaffidi and Bianchi, 2001). SOX proteins also rely on a ‘partner code’ to achieve transcriptional specificity (Kondoh and Kamachi, 2010). This partner code can be achieved either by binding of another transcription factor to a nearby site in the DNA, or by direct protein binding (Kamachi and Kondoh, 2013). Thus, it becomes easier to see how SOX2 can regulate multiple cell lineages, because its targets will change depending on the state of the chromatin and co-expression of transcription factors.

The partner code of SOX2 in the inner ear is unknown, although several transcription factors have been implicated in SOX2 function in different otic lineages, including EYA transcriptional coactivator and phosphatase 1 (EYA1), sine oculis-related homeobox 1 (SIX1) and myelocytomatosis oncogene (MYC) (Ahmed et al., 2012a,b; Evsen et al., 2013; Kempfle et al., 2016; Kwan et al., 2015). One potential partner for the early role of SOX2 in otic growth is the chromodomain helicase DNA-binding protein 7 (CHD7), which causes CHARGE syndrome, an autosomal dominant disorder characterized by craniofacial, cardiac, nervous system defects and inner ear defects (Adams et al., 2007). CHD7 has been identified as a SOX2 cofactor in several different systems (Doi et al., 2017; Engelen et al., 2011; Fujita et al., 2016), and shows similar defects to SOX2 in the ear, including defects in proliferation (Hurd et al., 2010).

Our work establishes functionally that SOX2 has an important role in the growth and morphogenesis of the otocyst before its sensory-specific function. Understanding the full and complex role of SOX2 will be important in future studies in promoting cell proliferation or sensory cell specification and/or differentiation in the developing ear.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All experimental procedures were performed in accordance with guidelines and regulations of the University of Rochester Medical Center. All animal experiments were approved by the University of Rochester's Committee on Animal Resources.

Mice and tamoxifen treatment

The following mouse strains were used: Sox2-CreERT2 (Arnold et al., 2011), ROSA26-CAGTdtomato (Madisen et al., 2010), Sox2flox (Shaham et al., 2009), NeurogGFP/+ (Ma et al., 1998), Foxg1-Cre (Hébert and McConnell, 2000) and Rosa26SOX2 (Lu et al., 2010). Genotyping was performed by PCR using the following primers: both Sox2-CreERT2 and Foxg1-Cre were detected with CreF (TGATGAGGTTCGCAAGAACC) and CreR (CCATGAGTGAACGAACCTGG), yielding a 350-bp band. Rosa26-CAGTdtomato: tdTF (CTGTTCCTGTACGGCATGG) and tdTR (GGCATTAAAGCAGCGTATCC) yield a 196-bp mutant band. Sox2flox: Sox2Fl WT1 (TGGAATCAGGCTGCCGAGAATCC), Sox2Fl WT2 (TCGTTCTGGCAACAAGTGCTAAAGC), and Sox2FlMut (CTGCCATAGCCACTCGAGAAG), yield a 427-bp wild-type band and a 546-bp mutant band. NeurogGFP/+: Neurog1 WT (ACCACTAGGCCTTTGTAAGG), Neurog1 Mutant (ATAGACCGAGGGCAGCTTCA) and Neurog1 Common (CGCTTCCTCGTGCTTTACGGTAT) yield a 198-bp wild-type band and a 500-bp mutant band. Timed matings were performed and the day of discovery of a vaginal plug was considered to be E0.5. Pregnant dams were given a single intraperitoneal injection of Tmx (3 mg/40 g body weight), along with an injection of progesterone (2 mg/40 g body weight) to counteract the antiestrogen effect of Tmx, during a specific time window, between 09.00 and 11.00 h, at various developmental time points. All mice analyzed for the study were embryonic and, therefore, did not have any distinguishing sex features.

Tissue preparation and immunohistochemistry

Embryos were collected at either E10.5, E11.5, E14.5 or E18.5. Younger ages (E10.5-E14.5) were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) for 2-2.5 h at 4°C, whereas E18.5 embryos were fixed overnight. Samples were cryoprotected overnight at 4°C in ascending concentrations of sucrose up to 30%, then embedded in tissue-freezing medium (TFM), and snap frozen on dry ice. Tissue was sectioned at a thickness of 16 µm. The sections were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C and then incubated with secondary antibodies for 2 h at room temperature. The primary antibodies used were goat polyclonal α-SOX2 (1:700, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-17320), rat monoclonal α-RFP (1:1000, ChromoTek, 5F8), rabbit polyclonal α-MYO6 (1:700, Proteus BioSciences, 25-6791), mouse monoclonal α-TUJ1 (1:1000, Covance, MMS-435P), rabbit polyclonal α-pHH3 [1:400, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Ser10(6G3)], mouse monoclonal α-pHH3 (1:400, Cell Signaling Technology, sc-8656-R), rabbit polyclonal α-cleaved caspase3 (1:1000, R&D Systems: AF835), goat polyclonal α-JAG1 c-20 (1:200, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, SC-6011) and mouse polyclonal α-CDKN1B/p27Kip1 (1:100, Thermo Fisher Scientific, MS-256-P). The secondary antibodies used were Alexa Fluor 488 donkey α-rabbit (1:1000; ab150073), Alexa Fluor 555 donkey α-rat (1:1000; ab150154), Alexa Fluor 555 donkey α-rabbit (1:1000; ab150074), Alexa Fluor 647 donkey α-mouse (1:1000; ab150107) and Alexa Fluor 647 donkey α-goat (1:1000; ab150135) (all from AbCam).

Paint-filling

E15.5 mouse embryos were harvested and fixed overnight in Bodian's fixative. Specimens were then dehydrated in ethanol, bisected and cleared in methyl salicylate. The lumen of the inner ears was injected via the common crus and/or cochlea with the use of a pulled glass capillary pipette (20-40 µm diameter) filled with 1% white gloss paint in methyl salicylate. Ears were dissected from the heads and imaged.

Quantifications and statistical analysis

All imaging was performed on a Zeiss upright epi-fluorescence microscope with PC interface. For tdT area measurements, the distribution of fate-mapped SOX2 progeny in nonsensory versus sensory tissue was quantified using Axiovision software (Carl Zeiss) to outline the area of tdT-positive cells in otic epithelium. Three different representative sections were quantified for each sensory organ. All ear components were separated into sensory versus nonsensory regions in the following manner. In the cochlea, tdT expression anywhere in the cochlear duct not in the organ of Corti was considered ‘nonsensory’, whereas only tdT seen in the organ of Corti was counted as ‘sensory’. Similarly, in the vestibular organs, tdT expressed in sensory areas, as delineated by expression of both SOX2 and MYO6, was counted as sensory, whereas tdT expressed anywhere else in the epithelium was counted as nonsensory. The number of pHH3- and caspase 3-expressing cells was quantified using Axiovision software (Carl Zeiss). For otocyst epithelial volume quantification, the area of E10.5 otic epithelium was measured in serial sections by outlining the inner and outer epithelium using Axiovision software (Carl Zeiss). A volume was calculated by multiplying the area of the otic epithelium by section thickness. Two-tailed Student's t-tests were used for statistical analysis. Prism Graphpad 6.0 was used for all statistics.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge members of the eye and ear research group at the University of Rochester, which include Drs Patricia White, Lin Gan, Richard Libby and Rebecca Rausch, for their advice and input into the project.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing or financial interests.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: A.R.S., A.E.K.; Methodology: A.R.S., A.E.K.; Formal analysis: A.R.S., J.C.G., A.E.K.; Investigation: A.R.S., J.C.G., C.C.K., A.E.K.; Resources: W.C.L., P.A.S., A.E.K.; Writing - original draft: A.R.S.; Writing - review & editing: A.R.S., A.E.K.; Supervision: A.E.K.; Project administration: A.E.K.; Funding acquisition: A.R.S., A.E.K.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders of the National Institutes of Health under award numbers F31DC015153 (A.R.S.) and RO1 DC009250 (A.E.K.), and a private donation from Bridget Sperl and John McCormick supported the development of the Neurog1−/− mice (P.A.S. and W.C.L.). Additional support was received from a grant to the Department of Ophthalmology at the University of Rochester from the foundation Research to Prevent Blindness (RPB). Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information available online at http://dev.biologists.org/lookup/doi/10.1242/dev.170522.supplemental

References

- Abelló G., Khatri S., Radosevic M., Scotting P. J., Giráldez F. and Alsina B. (2010). Independent regulation of Sox3 and Lmx1b by FGF and BMP signaling influences the neurogenic and non-neurogenic domains in the chick otic placode. Dev. Biol. 339, 166-178. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.12.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams M. E., Hurd E. A., Beyer L. A., Swiderski D. L., Raphael Y. and Martin D. M. (2007). Defects in vestibular sensory epithelia and innervation in mice with loss of Chd7 function: implications for human CHARGE syndrome. J. Comp. Neurol. 504, 519-532. 10.1002/cne.21460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed M., Wong E. Y. M., Sun J., Xu J., Wang F. and Xu P.-X. (2012a). Eya1-Six1 interaction is sufficient to induce hair cell fate in the cochlea by activating Atoh1 expression in cooperation with Sox2. Dev. Cell 22, 377-390. 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.12.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed M., Xu J. and Xu P.-X. (2012b). EYA1 and SIX1 drive the neuronal developmental program in cooperation with the SWI/SNF chromatin-remodeling complex and SOX2 in the mammalian inner ear. Development 139, 1965-1977. 10.1242/dev.071670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amador-Arjona A., Cimadamore F., Huang C. T., Wright R., Lewis S., Gage F. H. and Terskikh A. V. (2015). SOX2 primes the epigenetic landscape in neural precursors enabling proper gene activation during hippocampal neurogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112, E1936-E1945. 10.1073/pnas.1421480112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold K., Sarkar A., Yram M. A., Polo J. M., Bronson R., Sengupta S., Seandel M., Geijsen N. and Hochedlinger K. (2011). Sox2(+) adult stem and progenitor cells are important for tissue regeneration and survival of mice. Cell Stem Cell 9, 317-329. 10.1016/j.stem.2011.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avilion A. A., Nicolis S. K., Pevny L. H., Perez L., Vivian N. and Lovell-Badge R. (2003). Multipotent cell lineages in early mouse development depend on SOX2 function. Genes Dev. 17, 126-140. 10.1101/gad.224503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bani-Yaghoub M., Tremblay R. G., Lei J. X., Zhang D., Zurakowski B., Sandhu J. K., Smith B., Ribecco-Lutkiewicz M., Kennedy J., Walker P. R. et al. (2006). Role of Sox2 in the development of the mouse neocortex. Dev. Biol. 295, 52-66. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bermingham N. A., Hassan B. A., Price S. D., Vollrath M. A., Ben-Arie N., Eatock R. A., Bellen H. J., Lysakowski A. and Zoghbi H. Y. (1999). Math1: an essential gene for the generation of inner ear hair cells. Science 284, 1837-1841. 10.1126/science.284.5421.1837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bok J., Zenczak C., Hwang C. H. and Wu D. K. (2013). Auditory ganglion source of Sonic hedgehog regulates timing of cell cycle exit and differentiation of mammalian cochlear hair cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 13869-13874. 10.1073/pnas.1222341110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer L. A., Lee T. I., Cole M. F., Johnstone S. E., Levine S. S., Zucker J. P., Guenther M. G., Kumar R. M., Murray H. L., Jenner R. G. et al. (2005). Core transcriptional regulatory circuitry in human embryonic stem cells. Cell 122, 947-956. 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooker R., Hozumi K. and Lewis J. (2006). Notch ligands with contrasting functions: Jagged1 and Delta1 in the mouse inner ear. Development 133, 1277-1286. 10.1242/dev.02284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantos R., Cole L. K., Acampora D., Simeone A. and Wu D. K. (2000). Patterning of the mammalian cochlea. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 11707-11713. 10.1073/pnas.97.22.11707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavallaro M., Mariani J., Lancini C., Latorre E., Caccia R., Gullo F., Valotta M., DeBiasi S., Spinardi L., Ronchi A. et al. (2008). Impaired generation of mature neurons by neural stem cells from hypomorphic Sox2 mutants. Development 135, 541-557. 10.1242/dev.010801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P. and Segil N. (1999). p27(Kip1) links cell proliferation to morphogenesis in the developing organ of Corti. Development 126, 1581-1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P., Johnson J. E., Zoghbi H. Y. and Segil N. (2002). The role of Math1 in inner ear development: uncoupling the establishment of the sensory primordium from hair cell fate determination. Development 129, 2495-2505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cimadamore F., Amador-Arjona A., Chen C., Huang C.-T. and Terskikh A. V. (2013). SOX2-LIN28/let-7 pathway regulates proliferation and neurogenesis in neural precursors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, E3017-E3026. 10.1073/pnas.1220176110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dabdoub A., Puligilla C., Jones J. M., Fritzsch B., Cheah K. S. E., Pevny L. H. and Kelley M. W. (2008). Sox2 signaling in prosensory domain specification and subsequent hair cell differentiation in the developing cochlea. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 18396-18401. 10.1073/pnas.0808175105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doi T., Ogata T., Yamauchi J., Sawada Y., Tanaka S. and Nagao M. (2017). Chd7 collaborates with Sox2 to regulate activation of oligodendrocyte precursor cells after spinal cord injury. J. Neurosci. 37, 10290-10309. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1109-17.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvorakova M., Jahan I., Macova I., Chumak T., Bohuslavova R., Syka J., Fritzsch B. and Pavlinkova G. (2016). Incomplete and delayed Sox2 deletion defines residual ear neurosensory development and maintenance. Sci. Rep. 6, 38253 10.1038/srep38253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelen E., Akinci U., Bryne J. C., Hou J., Gontan C., Moen M., Szumska D., Kockx C., van Ijcken W., Dekkers D. H. et al. (2011). Sox2 cooperates with Chd7 to regulate genes that are mutated in human syndromes. Nat. Genet. 43, 607-611. 10.1038/ng.825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evsen L., Sugahara S., Uchikawa M., Kondoh H. and Wu D. K. (2013). Progression of neurogenesis in the inner ear requires inhibition of Sox2 transcription by neurogenin1 and neurod1. J. Neurosci. 33, 3879-3890. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4030-12.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari S., Harley V. R., Pontiggia A., Goodfellow P. N., Lovell-Badge R. and Bianchi M. E. (1992). SRY, like HMG1, recognizes sharp angles in DNA. EMBO J. 11, 4497-4506. 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05551.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferri A. L. M., Cavallaro M., Braida D., Di Cristofano A., Canta A., Vezzani A., Ottolenghi S., Pandolfi P. P., Sala M., DeBiasi S. et al. (2004). Sox2 deficiency causes neurodegeneration and impaired neurogenesis in the adult mouse brain. Development 131, 3805-3819. 10.1242/dev.01204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita K., Ogawa R. and Ito K. (2016). CHD7, Oct3/4, Sox2, and Nanog control FoxD3 expression during mouse neural crest-derived stem cell formation. FEBS J. 283, 3791-3806. 10.1111/febs.13843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith S., Lovell-Badge R. and Rizzoti K. (2016). SOX2 is sequentially required for progenitor proliferation and lineage specification in the developing pituitary. Development 143, 2376-2388. 10.1242/dev.137984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham V., Khudyakov J., Ellis P. and Pevny L. (2003). SOX2 functions to maintain neural progenitor identity. Neuron 39, 749-765. 10.1016/S0896-6273(03)00497-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groves A. K. and Fekete D. M. (2012). Shaping sound in space: the regulation of inner ear patterning. Development 139, 245-257. 10.1242/dev.067074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu R., Brown R. M. II, Hsu C. W., Cai T., Crowder A. L., Piazza V. G., Vadakkan T. J., Dickinson M. E. and Groves A. K. (2016). Lineage tracing of Sox2-expressing progenitor cells in the mouse inner ear reveals a broad contribution to non-sensory tissues and insights into the origin of the organ of Corti. Dev. Biol. 414, 72-84. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2016.03.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagey D. W. and Muhr J. (2014). Sox2 acts in a dose-dependent fashion to regulate proliferation of cortical progenitors. Cell Rep. 9, 1908-1920. 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hans F. and Dimitrov S. (2001). Histone H3 phosphorylation and cell division. Oncogene 20, 3021-3027. 10.1038/sj.onc.1204326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada Y. (1983). The function of the semicircular canals. In Atlas of the Ear, pp. 86-88. Dordrecht: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Hébert J. M. and McConnell S. K. (2000). Targeting of cre to the Foxg1 (BF-1) locus mediates loxP recombination in the telencephalon and other developing head structures. Dev. Biol. 222, 296-306. 10.1006/dbio.2000.9732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurd E. A., Capers P. L., Blauwkamp M. N., Adams M. E., Raphael Y., Poucher H. K. and Martin D. M. (2007). Loss of Chd7 function in gene-trapped reporter mice is embryonic lethal and associated with severe defects in multiple developing tissues. Mamm. Genome. 18, 94-104. 10.1007/s00335-006-0107-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurd E. A., Poucher H. K., Cheng K., Raphael Y. and Martin D. M. (2010). The ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling enzyme CHD7 regulates pro-neural gene expression and neurogenesis in the inner ear. Development 137, 3139-3150. 10.1242/dev.047894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyner A. L. and Zervas M. (2006). Genetic inducible fate mapping in mouse: establishing genetic lineages and defining genetic neuroanatomy in the nervous system. Dev. Dyn. 235, 2376-2385. 10.1002/dvdy.20884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julian L. M., Vandenbosch R., Pakenham C. A., Andrusiak M. G., Nguyen A. P., McClellan K. A., Svoboda D. S., Lagace D. C., Park D. S., Leone G. et al. (2013). Opposing regulation of Sox2 by cell-cycle effectors E2f3a and E2f3b in neural stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 12, 440-452. 10.1016/j.stem.2013.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamachi Y. and Kondoh H. (2013). Sox proteins: regulators of cell fate specification and differentiation. Development 140, 4129-4144. 10.1242/dev.091793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempfle J. S., Turban J. L. and Edge A. S. (2016). Sox2 in the differentiation of cochlear progenitor cells. Sci. Rep. 6, 23293 10.1038/srep23293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiernan A. E. (2006). The paintfill method as a tool for analyzing the three-dimensional structure of the inner ear. Brain Res. 1091, 270-276. 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.02.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiernan A. E., Nunes F., Wu D. K. and Fekete D. M. (1997). The expression domain of two related homeobox genes defines a compartment in the chicken inner ear that may be involved in semicircular canal formation. Dev. Biol. 191, 215-229. 10.1006/dbio.1997.8716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiernan A. E., Ahituv N., Fuchs H., Balling R., Avraham K. B., Steel K. P. and Hrabe de Angelis M. (2001). The Notch ligand Jagged1 is required for inner ear sensory development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 3873-3878. 10.1073/pnas.071496998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiernan A. E., Erven A., Voegeling S., Peters J., Nolan P., Hunter J., Bacon Y., Steel K. P., Brown S. D. M. and Guénet J.-L. (2002). ENU mutagenesis reveals a highly mutable locus on mouse Chromosome 4 that affects ear morphogenesis. Mamm. Genome 13, 142-148. 10.1007/s0033501-2088-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiernan A. E., Pelling A. L., Leung K. K. H., Tang A. S. P., Bell D. M., Tease C., Lovell-Badge R., Steel K. P. and Cheah K. S. E. (2005). Sox2 is required for sensory organ development in the mammalian inner ear. Nature 434, 1031-1035. 10.1038/nature03487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiernan A. E., Xu J. and Gridley T. (2006). The Notch ligand JAG1 is required for sensory progenitor development in the mammalian inner ear. PLoS Genet. 2, e4 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondoh H. and Kamachi Y. (2010). SOX-partner code for cell specification: Regulatory target selection and underlying molecular mechanisms. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 42, 391-399. 10.1016/j.biocel.2009.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopecky B., Santi P., Johnson S., Schmitz H. and Fritzsch B. (2011). Conditional deletion of N-Myc disrupts neurosensory and non-sensory development of the ear. Dev. Dyn. 240, 1373-1390. 10.1002/dvdy.22620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwan K. Y., Shen J. and Corey D. P. (2015). C-MYC transcriptionally amplifies SOX2 target genes to regulate self-renewal in multipotent otic progenitor cells. Stem. Cell Rep. 4, 47-60. 10.1016/j.stemcr.2014.11.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y.-S., Liu F. and Segil N. (2006). A morphogenetic wave of p27Kip1 transcription directs cell cycle exit during organ of Corti development. Development 133, 2817-2826. 10.1242/dev.02453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z., Walters B. J., Owen T., Brimble M. A., Steigelman K. A., Zhang L., Mellado Lagarde M. M., Valentine M. B., Yu Y., Cox B. C. et al. (2012). Regulation of p27Kip1 by Sox2 maintains quiescence of inner pillar cells in the murine auditory sensory epithelium. J. Neurosci. 32, 10530-10540. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0686-12.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y., Futtner C., Rock J. R., Xu X., Whitworth W., Hogan B. L. M. and Onaitis M. W. (2010). Evidence that SOX2 overexpression is oncogenic in the lung. PLoS ONE 5, e11022 10.1371/journal.pone.0011022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Q., Chen Z., del Barco Barrantes I., de la Pompa J. L. and Anderson D. J. (1998). neurogenin1 is essential for the determination of neuronal precursors for proximal cranial sensory ganglia. Neuron 20, 469-482. 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80988-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Q., Anderson D. J. and Fritzsch B. (2000). Neurogenin 1 null mutant ears develop fewer, morphologically normal hair cells in smaller sensory epithelia devoid of innervation. J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 1, 129-143. 10.1007/s101620010017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madisen L., Zwingman T. A., Sunkin S. M., Oh S. W., Zariwala H. A., Gu H., Ng L. L., Palmiter R. D., Hawrylycz M. J., Jones A. R. et al. (2010). A robust and high-throughput Cre reporting and characterization system for the whole mouse brain. Nat. Neurosci. 13, 133-140. 10.1038/nn.2467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matei V., Pauley S., Kaing S., Rowitch D., Beisel K. W., Morris K., Feng F., Jones K., Lee J. and Fritzsch B. (2005). Smaller inner ear sensory epithelia in Neurog 1 null mice are related to earlier hair cell cycle exit. Dev. Dyn. 234, 633-650. 10.1002/dvdy.20551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montcouquiol M. and Kelley M. W. (2003). Planar and vertical signals control cellular differentiation and patterning in the mammalian cochlea. J. Neurosci. 23, 9469-9478. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-28-09469.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morsli H., Choo D., Ryan A., Johnson R. and Wu D. K. (1998). Development of the mouse inner ear and origin of its sensory organs. J. Neurosci. 18, 3327-3335. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-09-03327.1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neves J., Kamaid A., Alsina B. and Giraldez F. (2007). Differential expression of Sox2 and Sox3 in neuronal and sensory progenitors of the developing inner ear of the chick. J. Comp. Neurol. 503, 487-500. 10.1002/cne.21299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neves J., Parada C., Chamizo M. and Giraldez F. (2011). Jagged 1 regulates the restriction of Sox2 expression in the developing chicken inner ear: a mechanism for sensory organ specification. Development 138, 735-744. 10.1242/dev.060657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neves J., Uchikawa M., Bigas A. and Giraldez F. (2012). The prosensory function of Sox2 in the chicken inner ear relies on the direct regulation of Atoh1. PLoS ONE 7, e30871 10.1371/journal.pone.0030871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neves J., Vachkov I. and Giraldez F. (2013). Sox2 regulation of hair cell development: incoherence makes sense. Hear. Res. 297, 20-29. 10.1016/j.heares.2012.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noramly S. and Grainger R. M. (2002). Determination of the embryonic inner ear. J. Neurobiol. 53, 100-128. 10.1002/neu.10131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ormsbee Golden B. D., Wuebben E. L. and Rizzino A. (2013). Sox2 expression is regulated by a negative feedback loop in embryonic stem cells that involves AKT signaling and FoxO1. PLoS ONE 8, e76345 10.1371/journal.pone.0076345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puligilla C. and Kelley M. W. (2016). Dual role for Sox2 in specification of sensory competence and regulation of Atoh1 function. Dev. Neurobiol. 77, 3-13. 10.1002/dneu.22401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puligilla C., Dabdoub A., Brenowitz S. D. and Kelley M. W. (2010). Sox2 induces neuronal formation in the developing mammalian cochlea. J. Neurosci. 30, 714-722. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3852-09.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Que J., Luo X., Schwartz R. J. and Hogan B. L. M. (2009). Multiple roles for Sox2 in the developing and adult mouse trachea. Development 136, 1899-1907. 10.1242/dev.034629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raft S., Nowotschin S., Liao J. and Morrow B. E. (2004). Suppression of neural fate and control of inner ear morphogenesis by Tbx1. Development 131, 1801-1812. 10.1242/dev.01067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiprich S. and Wegner M. (2014). Sox2: a multitasking networker. Neurogenesis 1, e962391 10.4161/23262125.2014.962391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzino A. (2013). Concise review: the Sox2-Oct4 connection: critical players in a much larger interdependent network integrated at multiple levels. Stem Cells 31, 1033-1039. 10.1002/stem.1352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruben R. J. (1967). Development of the inner ear of the mouse: a radioautographic study of terminal mitoses. Acta Otolaryngol. Suppl. 220, 221-244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar A. and Hochedlinger K. (2013). The sox family of transcription factors: versatile regulators of stem and progenitor cell fate. Cell Stem Cell 12, 15-30. 10.1016/j.stem.2012.12.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scaffidi P. and Bianchi M. E. (2001). Spatially precise DNA bending is an essential activity of the sox2 transcription factor. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 47296-47302. 10.1074/jbc.M107619200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaham O., Smith A. N., Robinson M. L., Taketo M. M., Lang R. A. and Ashery-Padan R. (2009). Pax6 is essential for lens fiber cell differentiation. Development 136, 2567-2578. 10.1242/dev.032888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steevens A. R., Sookiasian D. L., Glatzer J. C. and Kiernan A. E. (2017). SOX2 is required for inner ear neurogenesis. Sci. Rep. 7, 4086 10.1038/s41598-017-04315-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K. and Yamanaka S. (2006). Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell 126, 663-676. 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapia C., Kutzner H., Mentzel T., Savic S., Baumhoer D. and Glatz K. (2006). Two mitosis-specific antibodies, MPM-2 and phospho-histone H3 (Ser28), allow rapid and precise determination of mitotic activity. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 30, 83-89. 10.1097/01.pas.0000183572.94140.43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taranova O. V., Magness S. T., Fagan B. M., Wu Y., Surzenko N., Hutton S. R. and Pevny L. H. (2006). SOX2 is a dose-dependent regulator of retinal neural progenitor competence. Genes Dev. 20, 1187-1202. 10.1101/gad.1407906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods C., Montcouquiol M. and Kelley M. W. (2004). Math1 regulates development of the sensory epithelium in the mammalian cochlea. Nat. Neurosci. 7, 1310-1318. 10.1038/nn1349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu D. K., Nunes F. D. and Choo D. (1998). Axial specification for sensory organs versus non-sensory structures of the chicken inner ear. Development 125, 11-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J. L. and Gao W.-Q. (2000). Overexpression of Math1 induces robust production of extra hair cells in postnatal rat inner ears. Nat. Neurosci. 3, 580-586. 10.1038/75753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou C., Yang X., Sun Y., Yu H., Zhang Y. and Jin Y. (2016). Comprehensive profiling reveals mechanisms of SOX2-mediated cell fate specification in human ESCs and NPCs. Cell Res. 26, 171-189. 10.1038/cr.2016.15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.