Abstract

Objectives

Current clinical guidelines discourage long-term prescription of benzodiazepines and Z-drugs (BZD); however, the practice continues to exist. The aim of this study was to investigate the proportion of long-term BZD prescriptions and its risk factors.

Design

Retrospective cohort study using a health insurance database.

Setting

Japan.

Participants

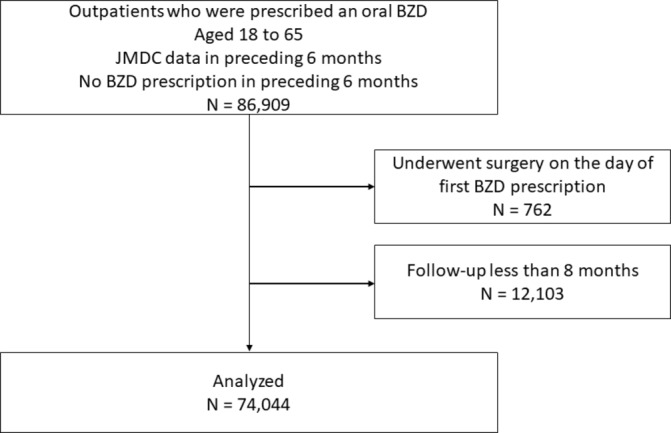

A total of 86 909 patients were identified as outpatients aged 18 to 65 years who started BZD between 1 October 2012 and 1 April 2015. After excluding patients who underwent surgery on the day of first BZD prescription (n=762) and patients without 8 months follow-up (n=12 103), 74 044 outpatients were analysed.

Main outcome measures

We investigated the proportion of long-term prescriptions for ≥8 months among new BZD users. We assessed patient demographics, diagnoses, characteristics of the initial BZD prescription and prescribers as potential predictors of the long-term BZD prescription. Multivariable logistic regression was performed to assess the association between long-term prescription and potential predictors.

Results

Of the new BZD users, 6687 (9.0%) were consecutively prescribed BZD for ≥8 months. The long-term prescription was significantly associated with mood and neurotic disorder, cancer, prescription by psychiatrists, multiple prescriptions, hypnotics and medium half-life BZD in the initial prescription.

Conclusion

Despite the recent clinical guidelines, 9% of new BZD users were given prescriptions for more than 8 months. Physicians should be aware of risk factors when prescribing BZDs for the first time.

Keywords: benzodiazepine, cohort study, dependence, long-term prescription, risk factors

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A large sample of Japanese outpatients among the non-elderly adult population.

Analysed new benzodiazepine users to prevent prevalent user bias.

A strict definition of long-term use of benzodiazepine by identifying consecutive monthly prescription data.

Limitations in detailed and accurate information in the health insurance database such as diagnosis and severity of psychiatric disorders.

Introduction

Globally, there is increasing concern about the long-term use of benzodiazepines and Z-drugs (BZD). Although BZDs are safer than old sedative hypnotics, the efficacy of their long-term use has not been demonstrated. Long-term use of BZD leads to dependence.1 Patients may become dependent on BZDs to avoid withdrawal symptoms.1–3 Studies have shown several adverse consequences related to the long-term use of BZD, including fracture,4 5 cancer6 and car accidents7 in any age group.

An understanding about the prevalence of long-term use of BZDs and its risk factors is essential for preventing adverse consequences. However, the reported prevalence of long-term BZD use varies widely because of variability in the definition of a long-term BZD prescription, study participants and follow-up period.8 9 Over half of previous studies did not provide an adequate explanation for the definitions.9 Some studies used one prescription per year or per several months as the definition of a long-term BZD prescription and others included prevalent users of BZDs or only the elderly as the study population. These studies may have overestimated the proportion of long-term prescription of BZDs.

The reported risk factors of a long-term prescription have been also inconsistent. In a systematic review,9 long-term prescription of BZDs were associated with an older age, psychiatric disorders and polypharmacy or high-dose BZDs at the initial prescription. However, the association of several other factors with long-term use of BZDs remains inconsistent, including demographic variables (eg, gender, income), type of BZDs (eg, half-life, Z-drug) or characteristics of prescriber (eg, psychiatry). The inconsistencies may have been affected by variability in the definition of long-term use of BZD.10 For example, in a study where long-term prescription was defined as at least one prescription every 3 months, female gender was a risk factor.11 However, in another study where long-term prescription was defined as BZD use lasting for 60 days, male gender was a risk factor.10

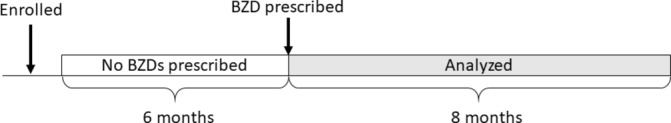

In this study, we followed new BZD users who continued the drugs for ≥8 consecutive months. This definition was selected based on two previous studies.9 12 In a systematic review, long-term BZD use was commonly defined as 6–12 months.9 In another study, about a half of patients who used BZDs for 8 months experienced clear withdrawal symptoms.12

Using a large-scale health insurance database with detailed prescription information, the present study investigated the proportion of long-term BZD prescriptions among new BZD users in Japan with a retrospective cohort design. We also assessed examined factors associated with the long-term prescription.

Methods

Data source

We used a health insurance claims database provided by JMDC Inc., Tokyo, Japan. JMDC Inc. has collected claims information from occupation-based health insurance agencies for corporate employees and their dependants since 2005.13 The JMDC database includes anonymous data of inpatient, outpatient and pharmacy claims and special health check-ups from about 3 000 000 individuals as of November 2014, representing about 2.5% of the Japanese population.14 Each record includes age, sex, diagnoses, prescriptions, information about the medical institution and date of the services. The diagnoses are based on International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10) diagnostic codes. The prescription information has the WHO’s Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (WHO-ATC) classification system codes, drug name, dosage, days of supply and mode of prescription. Date of prescriptions has been recorded since 1 April 2012. As such, we used data from 1 April 2012 through 31 December 2015. The requirement for informed consent was waived because of the anonymous nature of the data.

Patient selection

We selected outpatients aged 18 to 65 years who started at least one of the available oral BZDs between 1 October 2012 and 1 April 2015 (online supplementary table 1). We chose only subjects who had been continuously enrolled in the JMDC database for at least 6 months before the first prescription of BZDs. We defined new users as those who had not used any BZDs for this 6-month baseline period (figure 1). We excluded patients who were followed up for <8 months after the first BZD prescription. We also excluded those who underwent surgery on the day of the first BZD prescription. Surgeries were identified with original Japanese procedure codes. When extracting BZDs, we used the WHO-ATC codes N05BA, N05CD and N05CF.15 We added seven BZDs which were not covered by the WHO-ATC codes, but were available in Japan. We excluded clobazam (N05BA09), which is categorised as an anti-epileptic drug in Japan, from this study because this drug is likely to be needed as a BZD for a long term. Finally, 31 BZDs were included in this study.

Figure 1.

Patient selection. BZD, benzodiazepines and Z-drugs.

bmjopen-2019-029641supp001.pdf (129.6KB, pdf)

Definition of long-term BZD prescription

We defined long-term BZD users as those who received at least one prescription of any BZD every month for ≥8 consecutive months. This definition was based on the time of experiencing withdrawal symptoms.12 The prescriptions of most BZDs (23/31, 74.2%) are restricted to 30 days in Japan (online supplementary table 1) and most first-time prescriptions are usually for a short term.

Potential predictors of long-term BZD prescription

We assessed the following variables at the baseline period as potential predictors of long-term BZD use based on previous studies. Patient characteristics at the first BZD prescription included sex, age, occupational status (employed or dependent), diagnosis of cancer (ICD-10 code, C$) during the prior 6 months and psychiatric diagnosis (no diagnosis, mood disorders only (F3), neurotic, stress-related and somatic disorders only (F4), both mood and neurotic disorders but without other disorders (F3 and F4) and those with other psychiatric disorders (F0, 1, 5–9)). For example, if a patient had alcohol use disorder (F1) and depressive episode (F3), the person was categorised in other psychiatric disorders. Physician’s specialty (psychiatry or other) at the first BZD prescription was also evaluated. Pharmacological characteristics of the first BZD prescription included multiple BZDs (1 or ≥2), type of BZD (hypnotics only, anxiolytics only or both), administration instructions (as needed, regular prescription: 1 week (1–7 days), regular prescription: 2 weeks (8–14 days) and regular prescription: more than 2 weeks (≥15 days)) and half-life of BZD (short: <12 hours, medium: 12–24 hours, long: ≥24 hours). Multiple BZD was derived from the number of BZD ingredients in the first prescription. As for the variables of type of BZD, administration instruction and half-life of BZD, we selected the BZD with the longest prescription days if a patient was prescribed multiple BZDs.

Statistical analyses

First, we calculated the proportion for long-term use of BZD and compared potential predictors of long-term prescription between patients who were prescribed BZDs for ≥8 and <8 months. We used Student’s t-test to compare the average of continuous variables (such as age) and chi-squared test to compare the proportion of categorical variables (such as sex). Next, a multivariable logistic regression was performed to assess the association between potential predictors and long-term prescription.

Additionally, we compared participant characteristics at the first BZD prescription between those who were followed up for 8 months and those who were censored from this study cohort. Moreover, we conducted sensitivity analysis by changing the definition of long-term prescription to consecutive monthly prescription for 6 or 12 months to confirm the proportion of long-term prescriptions and risk factors for different definitions. Finally, we stratified the participants by prescription status (as needed or regular prescription) and then performed a multivariable logistic regression.

The threshold for significance was p<0.05. We used IBM SPSS version 23 (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA) for all statistical analyses.

Patient and public involvement

Patients or members of the public were not involved in the design or implementation of this study. Patients and the general public will be informed of the study results via publication.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total 86 909 patients were identified as new BZD users during the study period (figure 2). After excluding patients without 8 months follow-up (n=12 103) and patients who underwent surgery on the day of first BZD prescription (n=762), the remaining 74 044 patients were included in our analysis. At the first prescription, of 74 044 patients, 58 404 (86.7%) were prescribed BZDs for 14 days or less and 73 526 (99.3%) were prescribed BZDs for less than 30 days. There were 6687 patients (9.0%) who were prescribed BZDs over a period of ≥8 consecutive months. When stratified by gender, 10.8% of men and 7.1% of women continued BZD use for ≥8 months. As for age group, the proportion of long-term use was 8.9%, 9.3%, 9.6%, 8.7% and 7.2% for subjects aged 18–29, 30–39, 40–49, 50–59 and 60–65 years, respectively. Table 1 shows patient characteristics, information about physicians and pharmacological characteristics of the initial prescription. About half of patients were diagnosed with mood disorder, and hypnotics were more likely to be prescribed than anxiolytics.

Figure 2.

Participant flow diagram. BZD, benzodiazepines and Z-drugs.

Table 1.

Demographics and clinical characteristics for new users of benzodiazepines (n=74 004)

| BZD<8 months | BZD≥8 months | P value | |

| n=67 357 (91.0) | n=6687 (9.0) | ||

| Age (mean, SD) | 42.3 (11.8) | 41.9 (11.2) | 0.02 |

| Sex, male | 33 851 (50.3) | 4111 (61.5) | <0.001 |

| Occupational status, employed | 43 315 (64.3) | 4827 (72.2) | <0.001 |

| Cancer | 7073 (10.5) | 690 (10.3) | 0.66 |

| Medical spatiality, psychiatry | 17 986 (26.7) | 3845 (57.5) | <0.001 |

| Psychiatric diagnosis | <0.001 | ||

| None | 28 705 (42.6) | 1286 (19.2) | |

| Mood disorder (F3) | 9487 (14.1) | 2301 (34.4) | |

| Neurotic, stress-related and somatic disorder (F4) | 21 370 (31.7) | 1415 (21.2) | |

| Mood and neurotic disorders (F3 and F4) | 6537 (9.7) | 1489 (22.3) | |

| Other disorders | 1258 (1.9) | 196 (2.9) | |

| Multiple BZDs on first prescription | 6460 (9.6) | 1719 (25.7) | <0.001 |

| Type of BZD* | <0.001 | ||

| Hypnotic | 20 025 (29.7) | 2469 (36.9) | |

| Anxiolytic | 44 027 (65.4) | 3184 (47.6) | |

| Both | 3305 (4.9) | 1034 (15.5) | |

| Administration instructions* | <0.001 | ||

| As needed | 17 968 (26.7) | 969 (14.5) | |

| Regular prescription: 1 week (1–7 days) | 20 535 (30.5) | 2323 (34.7) | |

| Regular prescription: 2 weeks (8–14 days) | 19 901 (29.5) | 2423 (36.2) | |

| Regular prescription: more than 2 weeks (≥15 days) | 8953 (13.3) | 972 (14.5) | |

| Half-life of BZD* | <0.001 | ||

| Short (<12 hours) | 44 968 (66.8) | 3924 (58.7) | |

| Medium (12–24 hours) | 10 567 (15.7) | 1531 (22.9) | |

| Long (≥24 hours) | 11 822 (17.6) | 1232 (18.4) |

Data presented as n (%) unless otherwise specified.

* Characteristics of BZD with the longest prescription days in the first prescription.

BZD, benzodiazepines and Z-drugs.

A comparison of the baseline characteristics between the analysed patients and 12 103 patients who were censored is presented in online supplementary table 2. Censored patients were more likely to be given prescriptions by psychiatrists. Otherwise, the baseline characteristics were comparable between the groups.

bmjopen-2019-029641supp002.pdf (134.6KB, pdf)

Predictors of long-term prescription

Table 2 shows the results of the multivariable logistic regression. For patient characteristics, comorbidity of mood and neurotic disorders had the strongest association with long-term prescription compared with no psychiatric diagnosis (OR, 3.53; 95% CI, 3.19 to 3.90; p<0.001). Patients with cancer had a significantly higher risk of long-term BZD prescription than those without cancer (OR, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.08 to 1.29; p<0.001). As for characteristics of the first BZD prescription, prescription by psychiatry, hypnotics, regular prescription and medium half-life were associated with long-term prescription.

Table 2.

Factors related to long-term benzodiazepine prescription among new users of benzodiazepines (n=74 044)

| OR | 95% CI to P value | P value | |

| Age | 1.02 | 1.01 to 1.02 | <0.001 |

| Sex, male | 1.14 | 1.06 to 1.23 | <0.001 |

| Occupational status, employed | 0.98 | 0.91 to 1.06 | 0.58 |

| Cancer | 1.18 | 1.08 to 1.29 | <0.001 |

| Medical specialty, psychiatry | 1.80 | 1.68 to 1.94 | <0.001 |

| Psychiatric diagnosis | |||

| None | Ref. | ||

| Mood disorder (F3) | 3.30 | 3.01 to 3.62 | <0.001 |

| Neurotic, stress-related and somatic disorder (F4) | 1.49 | 1.36 to 1.62 | <0.001 |

| Mood and neurotic disorders (F3 and F4) | 3.53 | 3.19 to 3.90 | <0.001 |

| Other disorders | 2.37 | 2.00 to 2.80 | <0.001 |

| Multiple BZDs on first prescription | 1.41 | 1.28 to 1.54 | <0.001 |

| Type of BZD* | |||

| Hypnotic | Ref. | ||

| Anxiolytic | 0.61 | 0.57 to 0.66 | <0.001 |

| Both | 0.93 | 0.83 to 1.05 | 0.27 |

| Administration instructions* | |||

| As needed | Ref. | ||

| Regular prescription: 1 week (1–7 days) | 1.98 | 1.82 to 2.15 | <0.001 |

| Regular prescription: 2 weeks (8–14 days) | 1.91 | 1.76 to 2.07 | <0.001 |

| Regular prescription: more than 2 weeks (≥15 days) | 1.83 | 1.67 to 2.02 | <0.001 |

| Half-life of BZD* | |||

| Short (<12 hours) | Ref. | ||

| Medium (12–24 hours) | 1.08 | 1.01 to 1.16 | 0.03 |

| Long (≥24 hours) | 0.96 | 0.89 to 1.04 | 0.32 |

*Characteristics of BZD with the longest prescription days in the first prescription.

BZD, benzodiazepines and Z-drugs.

When changing the definition of long-term prescription, 11.8% and 6.1% of the participants continued to be prescribed BZDs for 6 and 12 months, respectively (online supplementary table 3). The risk factors for a long-term prescription were similar to the results when the definition was long-term prescription for 8 months (online supplementary table 4). As for the results of the stratified analysis, risk factors of long-term prescription among those with a regular prescription were the same as the results for all participants (online supplementary table 5). In patients who were prescribed BZDs as needed, sex, medical specialty, multiple BZDs prescription and half-life were not associated with long-term prescription.

bmjopen-2019-029641supp003.pdf (140.4KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-029641supp004.pdf (147.1KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-029641supp005.pdf (140.6KB, pdf)

Discussion

Using a large health insurance claims database, we investigated the proportion of long-term BZD prescriptions among new BZD users aged 18 to 65 years. A total of 9.0% continued BZDs for ≥8 months. Long-term BZD prescription was significantly associated with older age, cancer, comorbidity of mood and neurotic disorder, multiple BZD prescriptions, hypnotics, prescription by psychiatry, regular prescription and medium half-life of BZD at the initial prescription.

This study showed 6.1%, 9.0% and 11.8% of new users continued BZDs for ≥6 months, ≥8 months and ≥12 months, respectively. These figures were comparable to results in a previous study,9 but relatively lower than prevalence in most previous studies.8 16–18 This may be because previous studies used a prevalent user design or were conducted in an elderly population and resulted in an overestimation of long-term BZD use. In this study, prevalence of long-term prescription in a non-elderly population may be more reliable because we used a new-user design and assessed BZD use for ≥8 consecutive months. As another possible reason, low prevalence may be due to the development of guidelines for BZDs. Guidelines restricting long-term BZD prescription, such as the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guideline, were developed and have spread around the world since the 2000s. These guidelines may have affected physicians’ prescription practice. Furthermore, the guidelines potentially affected the prescription preferences of patients because the information became available on the Internet.

Risk factors for long-term use including older age, psychiatric disorders, users of hypnotics, regular prescription, multiple prescriptions and psychiatrist-prescriber were consistent with those in a previous study in Japan.11 Patients with a more severe condition may consult psychiatrists, be diagnosed with one or more psychiatric disorders and be prescribed a high dose of BZD for regular use. Although severe conditions may cause long-term use of BZDs, BZDs should be prescribed with caution because there is weak evidence for the efficacy of long-term BZD use and BZD is not the first-line treatment for depression and anxiety. The medium half-life of BZD was associated with long-term use in the present study. This result was consistent with that of other research using the same database.11 However, other studies suggested the risk of short-acting BZD,19 20 and evidence regarding the association between half-life and long-term use remains inconclusive in the literature.9 Since 2000, Z-drug hypnotics have become popular, and temporal differences in population characteristics may have resulted in the inconsistent study results. Further study is required to evaluate the effect of the half-life of BZD on long-term prescription in a population with different characteristics.

In this study, patients with cancer at the baseline were more likely to continue BZD. Patients with cancer may use and continue BZD because of pain and psychological distress,8 10 21 especially among non-elderly adults.22 23 Moreover, patients with cancer likely have these symptoms during and even after cancer treatment. It is important to manage pain and psychological distress by other measures to prevent additional adverse effects from long-term use of BZD among cancer patients.

Based on our findings, it is important to carefully prescribe BZD in accordance with the recommendation to avoid long-term use, especially for patients with a dual diagnosis of mood and neurotic disorder, using hypnotics, prescribed two or more BZDs, and with cancer. Prescription guidelines of BZD such as the NICE guideline and WHO recommend using BZD for up to 30 days.24 25 In Japan, the year-long prescription of BZD was disincentivised in 2018.26 However, this may not be sufficient to prevent long-term BZD use because most BZD users may already be dependent on BZDs by 1 year. Additional measures should be taken to restrict BZD prescriptions. For example, an option may be to disincentivise prescriptions of high-dose BZD at the initial prescription or continuation of BZD for more than 1 month based on the patient’s severity of psychiatric disorders.

The sensitivity analysis showed that the risk factors were almost the same when using different definitions of long-term prescription (≥6 or ≥12 months). This finding suggested the robustness of the analysis. However, the stratified analysis revealed that risk factors varied with a different prescription status (prescription as needed or regular prescription). Frequency of symptoms and physicians’ manner of prescription may influence prescription status. Further studies using detailed patient information and physicians’ intention of prescription is necessary to identify risk factors of long-term prescription in specific patient groups.

This study had several limitations related to claims data. First, the data did not include severity of psychiatric disorders and insomnia symptoms. Although we adjusted for diagnosis using ICD-10 codes, there may be residual confounding due to patient conditions. Second, the analysed cohort might not be representative of all included patients because censored patients were more likely to be prescribed first BZDs by psychiatrists. These patients might have had a relatively severe condition and tended to quit their job and change health insurance. Third, our definition of long-term prescription may also cause an underestimation of long-term prescription because people who received BZDs every 2 or 3 months were not counted as long term.

Conclusion

We identified several risk factors for determining long-term prescription of BZD among new users of BZD. Although the prevalence of long-term users was relatively low, assessment of these risk factors is necessary to prevent long-term prescription of BZDs when physicians prescribe BZD at an initial visit.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: AT, SO, HaY, TM, HiY and NK devised the study protocol. AT, SO, HaY, HM and HiY contributed to data collection and analysis and drafted the manuscript. All authors have contributed to interpretation and critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This research was supported by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan and The Health Care Science Institute, Japan.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of The University of Tokyo (No. 10862).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data available.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Soyka M. Treatment of benzodiazepine dependence. N Engl J Med 2017;376:1147–57. 10.1056/NEJMra1611832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Inada T, Inagaki A. Psychotropic dose equivalence in Japan. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2015;69:440–7. 10.1111/pcn.12275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pétursson H. The benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome. Addiction 1994;89:1455–9. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1994.tb03743.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Donnelly K, Bracchi R, Hewitt J, et al. . Benzodiazepines, Z-drugs and the risk of hip fracture: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2017;12:e0174730 10.1371/journal.pone.0174730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Weich S, Pearce HL, Croft P, et al. . Effect of anxiolytic and hypnotic drug prescriptions on mortality hazards: retrospective cohort study. BMJ 2014;348:1–12. 10.1136/bmj.g1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kim HB, Myung SK, Park YC, et al. . Use of benzodiazepine and risk of cancer: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Int J Cancer 2017;140:513–25. 10.1002/ijc.30443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Elvik R. Risk of road accident associated with the use of drugs: a systematic review and meta-analysis of evidence from epidemiological studies. Accid Anal Prev 2013;60:254–67. 10.1016/j.aap.2012.06.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fang SY, Chen CY, Chang IS, et al. . Predictors of the incidence and discontinuation of long-term use of benzodiazepines: a population-based study. Drug Alcohol Depend 2009;104:140–6. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.04.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kurko TA, Saastamoinen LK, Tähkäpää S, et al. . Long-term use of benzodiazepines: definitions, prevalence and usage patterns—a systematic review of register-based studies. Eur Psychiatry 2015;30:1037–47. 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2015.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Simon GE, VonKorff M, Barlow W, et al. . Predictors of chronic benzodiazepine use in a health maintenance organization sample. J Clin Epidemiol 1996;49:1067–73. 10.1016/0895-4356(96)00139-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Takeshima N, Ogawa Y, Hayasaka Y, et al. . Continuation and discontinuation of benzodiazepine prescriptions: a cohort study based on a large claims database in Japan. Psychiatry Res 2016;237:201–7. 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.01.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rickels K, Case WG, Downing RW, et al. . Long-term diazepam therapy and clinical outcome. JAMA 1983;250:767–71. 10.1001/jama.1983.03340060045024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kimura S, Sato T, Ikeda S, et al. . Development of a database of health insurance claims: standardization of disease classifications and anonymous record linkage. J Epidemiol 2010;20:413–9. 10.2188/jea.JE20090066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. JMDC Inc. Feature of JMDC Claims Database. https://www.jmdc.co.jp/pharma/database.html (Cited 18 Nov 2018).

- 15. WHOCC–ATC/DDD Index. https://www.whocc.no/atc_ddd_index/ (Cited 18 Nov 2018).

- 16. Cunningham CM, Hanley GE, Morgan S. Patterns in the use of benzodiazepines in British Columbia: examining the impact of increasing research and guideline cautions against long-term use. Health Policy 2010;97:122–9. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2010.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Isacson D. Long-term benzodiazepine use: factors of importance and the development of individual use patterns over time—a 13-year follow-up in a Swedish community. Soc Sci Med 1997;44:1871–80. 10.1016/S0277-9536(96)00296-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. van Hulten R, Isacson D, Bakker A, et al. . Comparing patterns of long-term benzodiazepine use between a Dutch and a Swedish community. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2003;12:49–53. 10.1002/pds.784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hallfors DD, Saxe L. The dependence potential of short half-life benzodiazepines: a meta-analysis. Am J Public Health 1993;83:1300–4. 10.2105/AJPH.83.9.1300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Owen RT, Tyrer P. Benzodiazepine dependence a review of the evidence. Drugs 1983;25:385–98. 10.2165/00003495-198325040-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Luijendijk HJ, Tiemeier H, Hofman A, et al. . Determinants of chronic benzodiazepine use in the elderly: a longitudinal study. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2008;65:593–9. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2007.03060.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mehta RD, Roth AJ. Psychiatric considerations in the oncology setting. CA Cancer J Clin 2015;65:299–314. 10.3322/caac.21285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Miovic M, Block S. Psychiatric disorders in advanced cancer. Cancer 2007;110:1665–76. 10.1002/cncr.22980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. NICE. Hypnotics | Guidance and guidelines. https://www.nice.org.uk/advice/ktt6/chapter/evidence-context (Cited 18 Nov 2018).

- 25. WHO. Programme on Substance Abuse. Rational use of benzodiazepines. 1996. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/65947/WHO_PSA_96.11.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (Cited 18 Nov 2018).

- 26. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Revisionof Medical Fees in 2018 (medical treatment and pharmaceutical)]. http://www.mhlw.go.jp/file/06-Seisakujouhou-12400000-Hokenkyoku/0000196430.pdf (Cited 18 Nov 2018).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-029641supp001.pdf (129.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-029641supp002.pdf (134.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-029641supp003.pdf (140.4KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-029641supp004.pdf (147.1KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-029641supp005.pdf (140.6KB, pdf)