Abstract

Background

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is associated with high morbidity and death, which increases as CKD progresses to end‐stage kidney disease (ESKD). There has been increasing interest in developing innovative, effective and cost‐efficient methods to engage with patient populations and improve health behaviours and outcomes. Worldwide there has been a tremendous increase in the use of technologies, with increasing interest in using eHealth interventions to improve patient access to relevant health information, enhance the quality of healthcare and encourage the adoption of healthy behaviours.

Objectives

This review aims to evaluate the benefits and harms of using eHealth interventions to change health behaviours in people with CKD.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant Register of Studies up to 14 January 2019 through contact with the Information Specialist using search terms relevant to this review. Studies in the Register are identified through searches of CENTRAL, MEDLINE, and EMBASE, conference proceedings, the International Clinical Trials Register (ICTRP) Search Portal and ClinicalTrials.gov.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐RCTs using an eHealth intervention to promote behaviour change in people with CKD were included. There were no restrictions on outcomes, language or publication type.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently assessed trial eligibility, extracted data and assessed the risk of bias. The certainty of the evidence was assessed using GRADE.

Main results

We included 43 studies with 6617 participants that evaluated the impact of an eHealth intervention in people with CKD. Included studies were heterogeneous in terms of eHealth modalities employed, type of intervention, CKD population studied and outcomes assessed. The majority of studies (39 studies) were conducted in an adult population, with 16 studies (37%) conducted in those on dialysis, 11 studies (26%) in the pre‐dialysis population, 15 studies (35%) in transplant recipients and 1 studies (2%) in transplant candidates We identified six different eHealth modalities including: Telehealth; mobile or tablet application; text or email messages; electronic monitors; internet/websites; and video or DVD. Three studies used a combination of eHealth interventions. Interventions were categorised into six types: educational; reminder systems; self‐monitoring; behavioural counselling; clinical decision‐aid; and mixed intervention types. We identified 98 outcomes, which were categorised into nine domains: blood pressure (9 studies); biochemical parameters (6 studies); clinical end‐points (16 studies); dietary intake (3 studies); quality of life (9 studies); medication adherence (10 studies); behaviour (7 studies); physical activity (1 study); and cost‐effectiveness (7 studies).

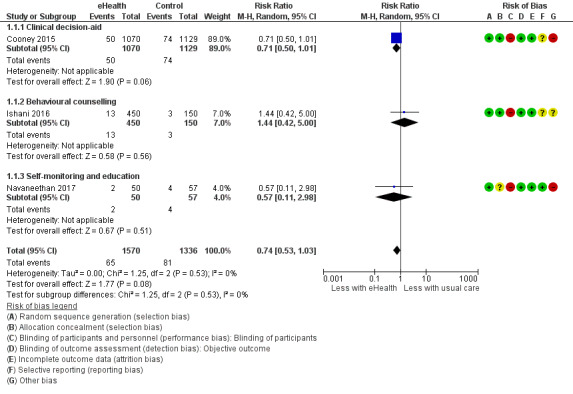

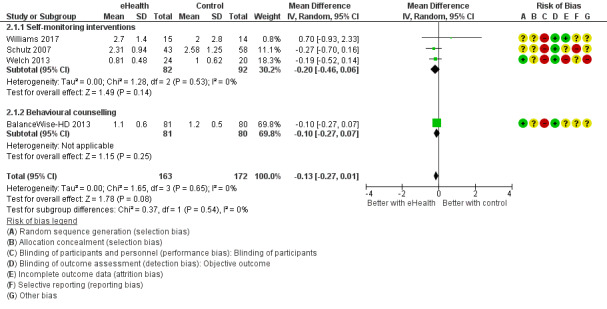

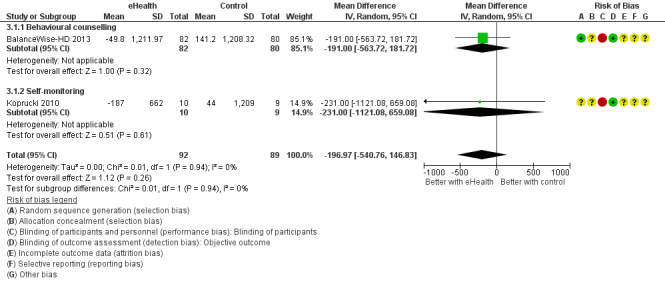

Only three outcomes could be meta‐analysed as there was substantial heterogeneity with respect to study population and eHealth modalities utilised. There was found to be a reduction in interdialytic weight gain of 0.13kg (4 studies, 335 participants: MD ‐0.13, 95% CI ‐0.28 to 0.01; I2 = 0%) and a reduction in dietary sodium intake of 197 mg/day (2 studies, 181 participants: MD ‐197, 95% CI ‐540.7 to 146.8; I2 = 0%). Both dietary sodium and fluid management outcomes were graded as being of low evidence due to high or unclear risk of bias and indirectness (interdialytic weight gain) and high or unclear risk of bias and imprecision (dietary sodium intake). Three studies reported death (2799 participants, 146 events), with 45 deaths/1000 cases compared to standard care of 61 deaths/1000 cases (RR 0.74, CI 0.53 to 1.03; P = 0.08). We are uncertain whether using eHealth interventions, in addition to usual care, impact on the number of deaths as the certainty of this evidence was graded as low due to high or unclear risk of bias, indirectness and imprecision.

Authors' conclusions

eHealth interventions may improve the management of dietary sodium intake and fluid management. However, overall these data suggest that current evidence for the use of eHealth interventions in the CKD population is of low quality, with uncertain effects due to methodological limitations and heterogeneity of eHealth modalities and intervention types. Our review has highlighted the need for robust, high quality research that reports a core (minimum) data set to enable meaningful evaluation of the literature.

Plain language summary

eHealth interventions for people with chronic kidney disease

What is the issue?

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a condition where kidneys have reduced function over a period of time. To remain well people with CKD need to follow complex diet, lifestyle and medication advice and often need to use several specialist medical services. Some people with advanced CKD may need dialysis or treatment with a kidney transplant. Enabling patients to manage this condition by themselves improves quality and length of life and reduces healthcare costs. Electronic health (eHealth) interventions may improve patients’ ability to look after themselves and improve care provided by healthcare services. eHealth interventions refer to "health services and information delivered or enhanced through the Internet and related technologies". However, there is little research evaluating the impact of eHealth interventions in CKD.

What did we do?

We focused on randomised controlled trials (RCT), which enrolled people with CKD (including pre‐dialysis, dialysis or kidney transplant), and compared eHealth interventions to usual care.

What did we find?

We found 43 studies involving 6617 people who had CKD that examined if eHealth interventions improve patient care and health outcomes. eHealth interventions used different modes of technology, such as Telehealth, electronic monitors, mobile or tablet applications, text message or emails, websites, and DVDs or videos. Interventions were classified by their intention: educational, reminder systems, self‐monitoring, behavioural counselling, clinical decision‐aids and mixed interventions. We categorised outcomes into nine domains: dietary intake, quality of life, blood pressure control, medication adherence, results of blood tests, cost‐analysis, behaviour, physical activity and clinical end‐points such as death. We found that it was uncertain whether using an eHealth interventions improved clinical and patient‐centred outcomes compared with usual care. The quality of the included studies was low, meaning we could not be sure that future studies would find similar results.

Conclusions

We are uncertain whether using eHealth interventions improves outcomes for people with CKD. We need large and good quality research studies to help understand the impact of eHealth on the health of people with CKD.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. EHealth interventions compared to standard care in chronic kidney disease populations.

| EHealth interventions compared to standard care in chronic kidney disease populations | |||||

| Patient or population: chronic kidney disease populations Setting: Intervention: eHealth interventions Comparison: standard care | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Risk with standard care | Risk with eHealth interventions | ||||

| Mortality follow up: mean 12 months | Study population | RR 0.74 (0.53 to 1.03) | 2906 (3 RCTs) 4 | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 3 | |

| 61 per 1,000 | 45 per 1,000 (32 to 62) | ||||

| Interdialytic weight gain follow up: range 6 weeks to 16 weeks | MD 0.13 lower (0.27 lower to 0.01 higher) | ‐ | 335 (4 RCTs) 5 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | |

| Dietary sodium intake follow up: mean 4 months | MD 197 mg lower (540.7 lower to 146.8 higher) | ‐ | 181 (2 RCTs) 6 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 3 | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; OR: Odds ratio; | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | |||||

1 Downgraded one level for uncertain or high risk of bias (allocation, blinding, outcome reporting, other biases)

2 Downgraded one level for inconsistency (different eHealth interventions used, different study lengths)

3 Downgraded one level for imprecision (small sample size or small number of events, confidence intervals overlap)

4 Behavioural counselling intervention (Ishani 2016), Clinical Decision Aid (Cooney 2015), Self‐monitoring and Education (Navaneethan 2017)

5 Behavioural counselling intervention (BalanceWise‐HD 2013), Self‐monitoring intervention (Schulz 2007, Welch 2013, Williams 2017)

6 Behavioural counselling intervention (BalanceWise‐HD 2013), Self‐monitoring intervention (Koprucki 2010)

Background

Description of the condition

Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) is associated with high morbidity and death, which increases as CKD progresses to end‐stage kidney disease (ESKD). Complications of CKD include cardiovascular disease, premature death, cancer, cognitive decline, anaemia, bone and mineral disorders and bone fractures, and hospitalisation, all associated with high health care usage (Stevens 2013; Jha 2013). Enhancing patient engagement and self‐management are the cornerstones of optimal chronic disease management (Tong 2007). Self‐management programs can improve patient knowledge, health‐related quality of life, delay the need for dialysis, improve clinical outcomes (e.g. blood pressure), improve treatment adherence and improve survival (Bonner 2014; Chen 2011; Devins 2005). The prevention of CKD, and delaying its progression to ESKD, requires complex care because it involves both specific CKD management, as well as management of other prevalent co‐morbidities (Lopez‐Vargas 2014). Interventions should focus on effective, cost‐efficient methods to improve modifiable risk factors such as weight, blood glucose control, blood pressure (BP) control and poor dietary intake that can improve morbidity and death (Couser 2011).

Description of the intervention

With rates of CKD and renal replacement therapy rising, there is a need to find innovative and efficient ways to engage with people with CKD and improve health behaviours and outcomes. Worldwide there is a tremendous increase in the use of technologies with up to 94% of people in developed countries accessing the internet or owning a smartphone (Pew Research Center 2016). In healthcare there is increasing interest in utilising technology‐based interventions, commonly referred to as eHealth, to improve patient engagement and enhance care. eHealth refers to"health services and information delivered or enhanced through the Internet and related technologies" (Eysenbach 2001), with these interventions being used to replace standard care or used as an adjunct to standard care. There is a variety of different eHealth modalities reported in the literature, including: Telehealth, mobile phone (including text messaging and the use of applications on mobile phones), internet and computer, electronic monitors and wireless and Bluetooth enabled devices. Within these eHealth interventions there is wide use of these tools, which are categorised as patient self‐management interventions or clinician decision support tools.

With more people using technology, the development, adoption and implementation of eHealth holds tremendous promise to improve consumer access to relevant health information, enhance the quality of care and encourage the adoption of healthy behaviours. However, there is currently no published systematic review of data regarding the optimal type, intensity and duration of eHealth strategies to most effectively elicit knowledge and behaviour change. Additionally, there is currently no systematic review of data regarding the impact of eHealth interventions to improve patient‐centred and clinical outcomes in the CKD population.

How the intervention might work

There are promising outcomes of using eHealth interventions, when used in addition to traditional counselling techniques, for improving disease management in chronic disease populations. Systematic reviews evaluating the impact of various eHealth interventions compared to standard care report similar or improved results regarding glycaemic control (Kitsiou 2017), CVD clinical outcomes (e.g. hospitalisations, myocardial infarction, stroke) and CVD risk factors (e.g. body mass index, blood pressure, cholesterol) (Widmer 2015), weight loss maintenance (Sorgente 2017), dietary intake (Cotter 2014; Kelly 2016) and exercise behaviours (Cotter 2014). However, to date poor study methodologies and insufficient reporting limit the determination of mechanisms that have prompted behaviour change and resulted in the success or failure of interventions. (Kitsiou 2017; Widmer 2015). Further research is needed to ascertain the most effective eHealth intervention/s to promote behaviour change in different contexts and diseases. In addition, evaluation of the level of consumer personalisation, frequency of interaction and duration (e.g. number of weeks, months or years) of interventions is needed. Similar to traditional interventions (e.g. in‐person counselling, paper‐based education), eHealth interventions that are designed with a theoretical basis incorporating content that is adaptive to individuals’ needs and utilises interactive components such as self‐monitoring, personalised feedback, bidirectional communication and group or peer support may result in better clinical and patient‐centred outcomes (Cotter 2014; Kitsiou 2017; Widmer 2015). To date economic evaluations of eHealth interventions has been sparse and highlights an important area for further research (Kitsiou 2017; Sanyal 2018).

The use of eHealth interventions in chronic diseases, such as diabetes and CVD, have shown eHealth interventions can improve or provide similar outcomes to traditional interventions (Kitsiou 2017; Widmer 2015). Given the current literature showing positive trends for the use of eHealth in chronic disease management and health behaviour change, it is foreseeable that the CKD population will benefit from the use of eHealth interventions and further review of the literature in CKD is warranted.

Why it is important to do this review

It is important to conduct this review, as strategies for improving patient engagement and enhancing outcomes are vital to reduce morbidity and death associated with all stages of CKD. Additionally, eHealth holds much promise for enhancing the delivery of healthcare in CKD and it is vital to determine which strategies are effective at promoting behaviour change and improve outcomes in CKD.

Objectives

This review aimed to evaluate the benefits and harms of using eHealth interventions to change health behaviours in people with CKD.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All RCTs and quasi‐RCTs (RCTs in which allocation to treatment was obtained by alteration, use of alternate medical records, date of birth or other predictable methods) will be included.

Types of participants

Adults and children who have been diagnosed with CKD (i.e. pre‐dialysis, dialysis and kidney transplant recipients) were included.

Diagnosis of CKD is defined by estimated GFR (eGFR) < 60 mL/min or, eGFR < 90 mL/min with albuminuria or haematuria, for at least three months or as defined using other clinically indicated criteria.

Types of interventions

Any interventions that the authors report to be using eHealth technologies to promote behaviour change in CKD. eHealth technologies include:

Telephone and Telehealth

Mobile phone (including applications available on these devices)

Computers and tablets (including applications available on these devices)

Personal Digital Assistants

Internet (including e‐mail)

Electronic transmission (e.g. using technologies such as Bluetooth)

Social Media

Electronic decision support tools.

The comparisons were as follows.

eHealth intervention versus non‐eHealth intervention

eHealth intervention versus alternate eHealth intervention

eHealth intervention versus no intervention or usual care

Meta‐analyses were conducted by analysing similar interventions of the same classifications (e.g. educational versus reminder systems) together for analysis.

Types of outcome measures

Time intervals at which outcome assessment takes place may affect the effect of the intervention programs. We considered all time frames used by authors.

1. Clinical parameters

Electrolyte management (measured using biochemical measurements)

Kidney function (measured using eGFR and/or serum creatinine)

Fluid management (measured using interdialytic weight gain (IDWG))

Co‐morbidity management (measured using BP control, dyslipidaemia, HbA1c, fasting and random blood glucose readings, anthropometry)

Hospitalisation rates

Death (all causes)

2. Patient‐centred parameters

Dietary intake and behaviours (measured using self‐reported data and qualitative and quantitative surveys)

Physical activity behaviours (using validated tools, quantitative and qualitative surveys, self‐reported data)

Adherence to medications (using validated or self‐reported data)

Adherence to appointments (using validated or self‐reported data)

Quality of life (measured using global or disease‐specific validated tools)

Nutritional status (measured using validated tools)

Self‐management and self‐efficacy

Satisfaction with interventions.

3. Cost effectiveness

Incremental cost‐effectiveness ratios (defined as the cost per quality‐adjusted life year gained)

Cost per Disability Adjusted Life Years (DALY)

Costs associated with eHealth intervention.

4. Potential harms

Additional patient or health professional time associated with the use of eHealth intervention

Anxiety due to frequent monitoring

Accidents or accidental deaths associated with using the eHealth intervention (e.g. reading text message while driving).

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant Register of Studies up to 14 January 2019 through contact with the Information Specialist using search terms relevant to this review. The Register contains studies identified from the following sources.

Monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL)

Weekly searches of MEDLINE OVID SP

Handsearching of kidney‐related journals and the proceedings of major kidney and transplant conferences

Searching of the current year of EMBASE OVID SP

Weekly current awareness alerts for selected kidney journals

Searches of the International Clinical Trials Register (ICTRP) Search Portal and ClinicalTrials.gov.

Studies contained in the Register are identified through searches of CENTRAL, MEDLINE, and EMBASE based on the scope of Cochrane Kidney and Transplant. Details of search strategies, as well as a list of handsearched journals, conference proceedings and current awareness alerts, are available in the Specialised Register section of information about Cochrane Kidney and Transplant.

See Appendix 1 for search terms used in strategies for this review.

Searching other resources

Reference lists of review articles, relevant studies and clinical practice guidelines.

Letters seeking information about unpublished or incomplete trials to investigators known to be involved in previous studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

We used the search strategy described to obtain titles and abstracts of studies relevant to the review. Two authors screened the titles and abstracts independently, studies that are not applicable were discarded. However, studies and reviews thought to include relevant data or information on studies were retained initially. Two authors independently assessed retrieved abstracts, and when necessary the full text, of these studies to determine studies that satisfied the inclusion criteria.

Data extraction and management

Data extraction was carried out independently by the same authors using standard data extraction forms. Studies reported in non‐English language were translated before assessment. Where more than one publication of a study was found, only the publication with the most complete data was included, however when relevant outcomes were only published in earlier versions these data were used. Further information required from the original author was requested by written correspondence and any relevant information obtained in this manner was included in the review. Disagreements were resolved in consultation with a third author.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The following items were assessed independently by two authors using the risk of bias assessment tool (Higgins 2011) (seeAppendix 2).

Was there adequate sequence generation (selection bias)?

Was allocation adequately concealed (selection bias)?

-

Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented during the study?

Participants and personnel (performance bias)

Outcome assessors (detection bias)

Were incomplete outcome data adequately addressed (attrition bias)?

Are reports of the study free of suggestion of selective outcome reporting (reporting bias)?

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?

Measures of treatment effect

For dichotomous outcomes (e.g. incidence of ESKD, death) results were expressed as risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Where continuous scales of measurement were used to assess the effects of treatment (e.g. quality of life, body weight), the mean difference (MD) was used, or the standardised mean difference (SMD) if different scales have been used, also reporting 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Unit of analysis issues

For studies with multiple treatment groups we combined all relevant experimental intervention groups of the study into a single group and combined all relevant control intervention groups into a single group to enable single pairwise comparison.

Dealing with missing data

Any further information required from the original authors was requested by email correspondence and relevant information obtained in this manner was included in the review. Evaluation of important numerical data such as screened, randomised patients as well as intention‐to‐treat, as‐treated and per‐protocol population was carefully performed. Attrition rates, losses to follow‐up and withdrawals were investigated. Issues of missing data and imputation methods (for example, last‐observation‐carried‐forward) was critically appraised (Higgins 2011).

Assessment of heterogeneity

We first assessed the heterogeneity by visual inspection of the forest plot. Heterogeneity was then analysed using a Chi2 test on N‐1 degrees of freedom, with an alpha of 0.05 used for statistical significance and with the I2 test (Higgins 2003). A guide to the interpretation of I2 values was as follows.

0% to 40%: might not be important

30% to 60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity

50% to 90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity

75% to 100%: considerable heterogeneity.

The importance of the observed value of I2 depends on the magnitude and direction of treatment effects and the strength of evidence for heterogeneity (e.g. P‐value from the Chi2 test, or a confidence interval for I2) (Higgins 2011).

Assessment of reporting biases

Due to the small number of studies we were unable to assess for the existence of small study bias using funnel plots.

Data synthesis

We classified our studies by target of intervention (educational, reminder system, educational plus reminders, behavioural counselling, self‐monitoring and clinical decision aid). Treatment estimates for specified outcomes (those that were reported by two or more studies) were summarised within groups of intervention types and treatment effects were summarised using random‐effects meta‐analysis. The eHealth interventions and associated implementation strategies were described using the "Better reporting of interventions: Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide" (Hoffmann 2014) and tabulated in the review.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Subgroup analysis was used to explore possible sources of heterogeneity. In our protocol we stated we would conduct subgroup analysis based on technology (e.g. mobile phone, internet). However, classifying interventions using technology type did not explain heterogeneity between interventions. Additionally, classification of studies by the World Health Organization's framework of interventions for clients (Appendix 3) did not provide sufficient subgroup differentiation as the majority of studies could be classified into two types of interventions: targeted communication to clients and personal health tracking. We determined that heterogeneity between eHealth interventions was better explained by the target of the intervention (e.g. educational versus self‐monitoring) and therefore we used these classifications when conducting subgroup analyses. There were insufficient extractable data to conduct subgroup and univariate meta‐regression analysis to explore the following variables as possible sources of heterogeneity: mean study age, mean proportion of men, adequacy of allocation concealment, sample size, and duration of follow up (< 12 months versus ≥ 12 months).

Sensitivity analysis

There were insufficient extractable data to perform the following sensitivity analyses in order to explore the influence of the following factors on effect size:

Repeating the analysis excluding unpublished studies

Repeating the analysis taking account of risk of bias, as specified

Repeating the analysis excluding any very long or large studies to establish how much they dominate the results

Repeating the analysis excluding studies using the following filters: diagnostic criteria, language of publication, source of funding (industry versus other), and country.

'Summary of findings' tables

We presented the main results of the review in 'Summary of findings' tables. These tables present key information concerning the quality of the evidence, the magnitude of the effects of the interventions examined, and the sum of the available data for the main outcomes (Schünemann 2011a). The 'Summary of findings' table includes an overall grading of the evidence related to each of the main outcomes using the GRADE (Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) approach (GRADE 2008; GRADE 2011). The GRADE approach defines the quality of a body of evidence as the extent to which one can be confident that an estimate of effect or association is close to the true quantity of specific interest. The quality of a body of evidence involves consideration of within‐trial risk of bias (methodological quality), directness of evidence, heterogeneity, precision of effect estimates and risk of publication bias (Schünemann 2011b).

The key outcomes presented in the Summary of findings table 1 include:

Death

Fluid management

Dietary intake (sodium).

Results

Description of studies

See Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of ongoing studies.

Results of the search

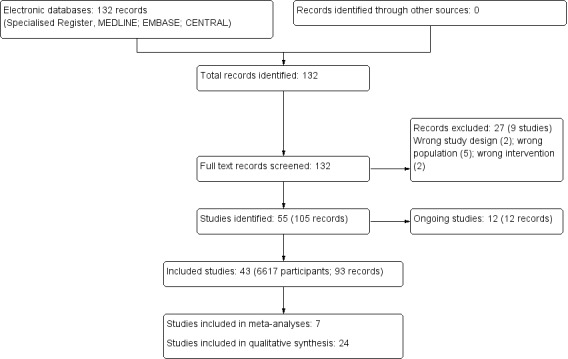

We searched the Specialised Register and identified 132 records. After screening titles and abstracts and full‐text review, 43 studies (93 records) were included and nine studies (27 records) were excluded. Twelve ongoing studies were identified (CONNECT 2017; eNEPHRO 2017; Jung 2017; KARE 2015; Kosaka 2017; MAGIC 2016; NCT00394576; NCT02097550; NCT02610946; TELEGRAFT 2015; Waterman 2015; WISHED 2016), These 12 studies and will be assessed in a future update of this review (Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

We included 43 studies (93 reports; 6617 participants) in this review. The included studies were conducted between 1999 and 2017, with the majority published since 2010 (38 of 43 studies, 88%). Nine studies (Durand 2000; Halleck 2017; Han 2016; Hardstaff 2002; Jammalamadaka 2015; Ong 2017; Potter 2016; SUBLIME 2016; White 2010) (23%) had only abstracts from conference proceedings or short reports available. All studies were published in English. The majority of studies were conducted in an adult population (39 studies), and the majority of studies were conducted in North America (26 studies). Eleven studies enrolled 4315 participants with pre‐dialysis CKD, 10 studies enrolled 681 participants on haemodialysis (HD), six studies enrolled 281 participants on peritoneal dialysis, 15 studies enrolled 1281 kidney transplant recipients, and one study enrolled 288 transplant candidates. Participant numbers ranged from 6 to 2199 (mean study population, 153; median study population, 75), with study durations varying from one clinic appointment to 24 months (median follow‐up period was 16 weeks). Most (20 studies) compared an eHealth intervention to usual care involving traditional methods (e.g. face‐to‐face counselling), 11 studies did not adequately describe the control group and 12 studies compared an active eHealth intervention to a passive, control eHealth intervention. Studies used various eHealth technologies including: Telehealth (e.g. phone calls, video monitoring, teleconferencing) (10 studies), mobile phone or tablet applications (11 studies), mobile phone text messaging or emails (2 studies), electronic monitors (11 studies), internet or website (4 studies), video or DVD (2 studies), or mixed methods, where more than one eHealth technology was used (3 studies). Table 2 provides an overview of the characteristics of included studies.

1. Overview of characteristics of included studies.

| Total studies (participants) | 43 (6617) | |

| No. studies | % studies | |

| Country | ||

| Australia | 1 | 2% |

| North America | 26 | 60% |

| UK | 5 | 12% |

| Europe | 6 | 14% |

| Middle East | 3 | 7% |

| Asia | 2 | 5% |

| Number of participants | ||

| 0‐50 | 17 | 40% |

| 51‐100 | 10 | 23% |

| 101‐200 | 10 | 23% |

| 201‐300 | 3 | 7% |

| 300+ | 3 | 7% |

| Length of intervention | ||

| ≤ 1 week | 4 | 9% |

| 1‐3 months | 16 | 37% |

| 4‐6 months | 9 | 21% |

| > 6 months | 13 | 30% |

| unclear | 1 | 2% |

| Participant age | ||

| Paediatric (including carers) | 4 | (9% |

| Adult (≥ 18 years) | 39 | (91% |

| Stage of CKD | ||

| CKD stage 1‐5 | 11 | 26% |

| Haemodialysis | 10 | 23% |

| Peritoneal dialysis | 6 | 14% |

| Transplant candidates | 1 | 2% |

| Transplant recipient | 15 | 35% |

| eHealth modality | ||

| Telehealth | 10 | 23% |

| Mobile or tablet app | 11 | 26% |

| Mobile phone text message | 2 | 5% |

| Electronic monitoring | 11 | 26% |

| Internet website | 4 | 9% |

| Video or DVD | 2 | 5% |

| Mixed methods | 3 | 7% |

| eHealth intervention category | ||

| Education | 4 | 9% |

| Reminders | 5 | 12% |

| Self‐monitoring | 9 | 21% |

| Behavioural counselling | 16 | 37% |

| Clinical decision‐aid Mixed interventions Unclear |

4 4 1 |

9% 9% 2% |

| Publication type | ||

| Abstract or short report | 10 | 23% |

| Journal article | 33 | 77% |

CKD ‐ chronic kidney disease

Our study classifications were as follows:

Educational (four studies: Baraz 2014; Diamantidis 2015; Giacoma 1999; InformMe 2017)

Reminders (6 studies: Halleck 2017; Han 2016; Henriksson 2016; Jammalamadaka 2015; McGillicuddy 2013; Potter 2016)

Self‐monitoring (9 studies: BALANCEWise‐HD 2011; BALANCEWise‐PD 2011; Koprucki 2010; Kullgren 2015; Ong 2017; Rifkin 2013; Schulz 2007; Welch 2013; Williams 2017)

Behavioural counselling (16 studies: BalanceWise‐HD 2013; BRIGHT 2013; Cargill 2003; iDiD 2016; Ishani 2016; Kargar Jahromi 2016; Li 2014b; MESMI 2010; Poorgholami 2016a; Reilly‐Spong 2015; Russell 2011; Schmid 2016; Swallow 2016; TAKE‐IT 2014; White 2010)

Clinical decision‐aids (4 studies: Cooney 2015; Durand 2000; Hardstaff 2002; iChoose 2016)

Mixed interventions (4 studies: Navaneethan 2017; Reese 2017; Robinson 2014a; Robinson 2015)

Of the 43 studies, seven studies reported outcome data used in quantitative analyses, while data from 24 studies could only be presented descriptively. Eleven studies could not be included in qualitative analyses due to insufficient reporting of outcome data (Cargill 2003; Diamantidis 2015; Giacoma 1999; Halleck 2017; Han 2016; Ong 2017; SUBLIME 2016; White 2010) or data was only being available for the intervention group (BALANCEWise‐HD 2011, BALANCEWise‐PD 2011; Swallow 2016). Reported outcomes were broadly categorised as:

Clinical parameters

Blood pressure control (9 studies)

Biochemical parameters (6 studies)

Clinical end‐points (16 studies)

Patient‐centred parameters

Dietary intake (3 studies)

Quality of life (9 studies)

Medication adherence (10 studies)

Behaviour (7 studies)

Physical activity (1 study)

Cost‐effectiveness

Cost‐analysis (7 studies)

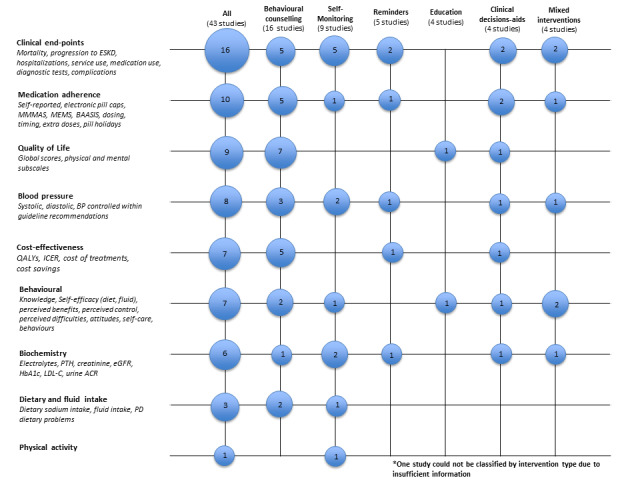

We identified 98 outcomes within these domains. However, 65 outcomes (66%) were only reported by single studies. Additionally, due to the heterogeneity of interventions only three outcomes (dietary sodium intake, IDWG and death) were able to be quantitatively analysed. Tables 2 to 7 (Table 3; Table 4; Table 5; Table 6; Table 7; Table 8) contain descriptive analyses for reported outcomes. Figure 2 depicts a bubble plot of reported outcomes.

2. Descriptive analyses of reported outcomes for educational interventions.

| Outcome Study ID | Outcome measure | Study population (No. of participants); study duration | Results |

| Behavioural | |||

| Knowledge InformMe 2017 |

31‐item multiple choice test | Adults, kidney transplant candidates (28); 1 week | Intervention: mean 17.94 (SD 6.06) Control: mean 14.7 (SD 5) P = 0.001 |

| Willingness to perform a behaviour InformMe 2017 |

Willingness to accept an Increased Risk Donor Kidney Lower scores indicate more willingness |

Adults, kidney transplant candidates (188); 1 week | Intervention: mean 2.54 (SD 1.45) Control: mean 2.81 (SD 1.2) P = 0.09 |

| Quality of Life | |||

| Fatigue Baraz 2014 |

SF‐36 Higher scores indicate better QoL |

Adults, HD (90); 6 months | Intervention: mean 48.9 (SD 15) Control: mean 56.1 (SD 20.6) P = 0.034 |

| General health perception Baraz 2014 |

SF‐36 Higher scores indicate better QoL |

Adults, HD (90); 6 months | Intervention: mean 41.01 (SD 16.87) Control: mean 48.38 (SD 18.18) P = 0.94 |

| Mental health Baraz 2014 |

SF‐36 Higher scores indicate better QoL |

Adults, HD; (90); 6 months | Intervention: mean 49.84 (SD 18.84) Control: mean 55.07 (SD 27.9) P < 0.001 |

| Pain Baraz 2014 |

SF‐36 Higher scores indicate higher QoL |

Adults, HD (90); 6 months | Intervention: mean 55.45 (SD 29.14), Control: mean 53.22 (SD 32.34) P = NS |

| Physical functioning Baraz 2014 |

SF‐36 Higher scores indicate better QoL |

Adults, HD (90); 6 months | Intervention: mean 70.15 (SD 13.4) Control: mean 68.63 (SD 22.82) P = 0.021 |

| Role (emotional) Baraz 2014 |

SF‐36 Higher scores indicate better QoL |

Adults, HD (90); 6 months | Intervention: mean 50.53 (SD 21.92) Control: mean 44.76 (SD 19.7) P = 0.26 |

| Role (physical) Baraz 2014 |

SF‐36 Higher scores indicate better QoL |

Adults, HD (90); 6 months | Intervention: mean 50.51 (SD 18.9) Control: mean 60.48 (SD 22.14) P = 0.031 |

| Social functioning Baraz 2014 |

SF‐36 Higher scores indicate better QoL |

Adults, HD (90); 6 months | Intervention: mean 67.74 (SD 20.09) Control: mean 64.06 (SD 19.24) P < 0.001 |

CI ‐ confidence interval; HD ‐ haemodialysis; QoL ‐ quality of life; RR ‐ risk ratio; SD ‐ standard deviation

3. Descriptive analyses of reported outcomes for reminder interventions.

| Outcome Study ID | Outcome measure | Study population (No. of participants); study duration | Results |

| Biochemical parameters | |||

| Phosphate Jammalamadaka 2015 |

Serum phosphate | Adults, HD (27); 7 days | Intervention: mean 6.00 (SD 1.2) Control: mean 6.19 (SD 0.76) P = 0.76 |

| Blood pressure | |||

| Blood pressure within guideline recommendations McGillicuddy 2013 |

Blood pressure within pre‐specified goals | Adults, kidney transplant recipients (17); 3 months | RR 4.50 (95% CI 0.63, 32.38) P = 0.13 |

| Systolic blood pressure McGillicuddy 2013 |

Higher readings indicate poorer control | Adults, kidney transplant recipients (17); 3 months | Intervention: mean 131 (SD 10.5) Control: 155.3 (SD 15) P = 0.004 |

| Clinical end‐points | |||

| Hospitalisations Henriksson 2016 |

Unplanned admission rates to hospital or emergency department | Adults, kidney transplant recipients (80); 12 months | RR 0.71 (95% CI 0.48 to 1.05) Intervention: 22/53 events Control: 31/53 events |

| Rejection episodes Henriksson 2016 |

Number of rejection episodes | Adults, kidney transplant recipients (80); 12 months | Intervention: 6 rejections in 4 participants Control: 27 rejections in 13 participants) |

| Rejection episodes Potter 2016 |

Number of rejection episodes | Adults, kidney transplant recipients (46); 1 year | Intervention: 0/20 Control: 9/26 |

| Medication adherence | |||

| Medication adherence McGillicuddy 2013 |

Measured using electronic medication tray openings | Adults, kidney transplant recipients (19); 3 months | Intervention: mean 0.945 (SD 0.11) Control: mean 0.574 (SD 0.11) |

HD ‐ haemodialysis; RR ‐ risk ratio; SD ‐ standard deviation

4. Descriptive analyses of reported outcomes for self‐monitoring interventions.

| Outcome Study ID | Outcome measure | Study population (No. of participants); study duration | Results | |

| Behavioural | ||||

| Attitudes towards performing a behaviour Welch 2013 |

Perceived benefits of fluid adherence Higher score indicates more perceived benefits |

Adults, HD (33); 6 weeks | Intervention: mean 39.8 (SD 4.5) Control: mean 40.1 (SD 4.9) P = 0.28 |

|

| Perceived benefits of sodium adherence Welch 2013 |

Benefits of sodium adherence Higher score indicates higher perceived benefits |

Adults, HD (35); 6 weeks | Intervention: mean 29.9 (SD 4.4) Control: mean 30.3 (SD 4.2) P = 0.77 |

|

| Perceived control Welch 2013 |

7‐item mastery scale Higher score indicates higher perceived control |

Adults, HD (35); 6 weeks | Intervention: mean 28.5 (SD 4.9) Control: mean 23.6 (SD 14.3) P > 0.1 |

|

| Self‐efficacy (diet) Welch 2013 |

Cardiac diet self‐efficacy instrument Higher score indicates higher self‐efficacy |

Adults, HD (35); 6 weeks | Intervention: mean 32.7 (SD 10.1) Control: mean 31.1 (SD 10.2) P = 0.4 |

|

| Self‐efficacy (fluid) Welch 2013 |

Fluid Self‐Efficacy Scale Higher score indicates higher self‐efficacy |

Adults, HD (36); 6 weeks | Intervention: mean 41.4 (SD 5.8) Control: mean 43.9 (SD 6.4) P = 0.21 |

|

| Biochemical parameters | ||||

| Kidney function Kullgren 2015 |

Serum creatinine | Children, kidney transplant recipients (31); 4 weeks | Intervention: mean 16.8 (SD 21.2) Control: mean 11 (SD 15.2) P = 0.53 |

|

| Kidney function Rifkin 2013 |

Serum creatinine | CKD stage 3 or greater (43); 6 months | Intervention: mean 2.17 (SD 0.76) Control: mean 2.32 (SD 0.84) P = 0.12 |

|

| Serum sodium Kullgren 2015 |

% change in serum sodium | Children, kidney transplant recipients (31); 4 weeks | Intervention: median 0 (range ‐4.86 to 1.45) Control: median ‐0.72 (range ‐3.52 to 2.19) P = 0.29 |

|

| Urea Nitrogen Kullgren 2015 |

% change in blood urea nitrogen | Children, kidney transplant recipients (31); 4 weeks | Intervention: median ‐2.38 (range ‐36.84 to 61.54) Control: median 4.56 (range ‐31.25 to 107.33) P = 0.78 |

|

| Blood pressure | ||||

| Blood pressure control Rifkin 2013 |

Mean arterial pressure | CKD stage 3 or greater (43); 6 months | Intervention: mean 93.9 (SD 8.6) Control: mean 95.2 (SD 11.7) P = 0.67 |

|

| Diastolic blood pressure Rifkin 2013 |

Higher readings indicate poorer control | CKD stage 3 or greater (43); 6 months | Intervention: mean 73 (SD 10.3) Control: mean 73 (SD 12.6) P = 0.93 |

|

| Diastolic blood pressure Schulz 2007 |

Higher readings indicate poorer control | Adults, HD (101); 3 months | Intervention: mean 66.9 (SD 8.7) Control: mean 65 (SD 8.8) P < 0.05 |

|

| Management of hypertension Rifkin 2013 |

Number of anti‐hypertensive medications | CKD stage 3 or greater (43); 6 months | Intervention: mean 4 (SD 1.2) Control: mean 3.9 (SD 1.3) P = 0.61 |

|

| Systolic blood pressure Rifkin 2013 |

Higher readings indicate poorer control | CKD stage 3 or greater (43); 6 months | Intervention: mean 136 (SD 15.6) Control: mean 140 (SD 14.4) P = 0.48 |

|

| Systolic blood pressure Schulz 2007 |

Higher readings indicate poorer control | Adults, HD (101); 3 months | Intervention: mean 116 (SD 17) Control: mean 17.9 (SD 19.5) P = NS |

|

| Clinical end‐points | ||||

| Hospitalisations Schulz 2007 |

Unplanned admission rates to hospital or ED | Adults, HD (101); 3 months | Intervention: mean 2.2 (SD 5.5) Control: mean 3.31 (SD 7.3) |

|

| Medication usage Rifkin 2013 |

Total number of medications | CKD stage 3 or greater (43); 6 months | Intervention: mean 12 (SD 4.6) Control: mean 12.8 (SD 5.1) P = 0.62 |

|

| Sleep duration (minutes) Williams 2017 |

Fitbit Flex activity tracker | Adults, HD (29); 5 weeks | Intervention: mean 389.9 (SD 69.6) Control: mean 349.8 (SD 80.0) P = NS |

|

| Sleep efficiency (%) Williams 2017 |

Fitbit Flex activity tracker | Adults, HD (29); 5 weeks | Intervention: mean 86.1 (SD 4.6) Control: mean 80.3 (SD 7.1) P < 0.05 |

|

| Ultrafiltration Schulz 2007 |

mL/hour during dialysis, weekly average | Adults, HD (101); 3 months | Intervention: mean 621.6 (SD 169.7 mL/hour) Control: mean 652.5 (SD 198.6 mL/hour) P = 0.712 |

|

| Dietary intake | ||||

| Fluid intake Kullgren 2015 |

3‐day fluid log through electronic water bottle | Children, kidney transplant recipients (32); 4 weeks | Unadjusted OR 12.25 (95% CI 1.08 to 138.99) P = 0.043 Intervention group significantly improved. |

|

| Medication adherence | ||||

| Medication adherence Rifkin 2013 |

Morisky Medication Adherence Scale Higher scores indicate better adherence |

CKD stage 3 or greater (43); 6 months | Intervention: mean 7 (SD 1.2) Control: mean 7.2 (SD 1.4) P = 0.58 |

|

| Physical activity | ||||

| Physical activity, distance (km) Williams 2017 |

FitBit Flex activity tracker | Adults, HD (29); 5 weeks | Intervention: mean 2.3 (SD 1.2) Control: mean 2.2 (SD 0.8) P = NS |

|

| Physical activity (steps) Williams 2017 |

FitBit Flex activity tracker | Adults, HD (29); 5 weeks | Intervention: mean 5365 (SD 2765) Control: mean 5211 (SD 2010) P = NS |

|

CKD ‐ chronic kidney disease; HD ‐ haemodialysis; NS ‐ not significant; OR ‐ Odds ratio; SD ‐ standard deviation

5. Descriptive analyses of reported outcomes for behavioural counselling interventions.

|

Outcome Study ID |

Outcome measure | Study population (No. of participants); study duration | Results |

| Behavioural | |||

| Illness perception iDiD 2016 |

Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire Higher score indicates more negative perception of ESKD |

Adults, HD (25); 3 months | Intervention: mean 44.2 (SD 12.09) Control: mean 41.2 (SD 10.28) |

| Knowledge BRIGHT 2013 |

Modified Morisky’s Medication Adherence Scale Higher score indicates higher medication knowledge |

Adults, ≥ CKD stage 3 ± proteinuria (366); 6 months | Intervention: mean 2.6 (SD 0.6) Control: mean 2.6 (SD 0.6) P = 0.331 |

| Self‐care behaviours BRIGHT 2013 |

Summary of Diabetes Self Care Activities Higher sore indicates higher self‐care |

Adults, ≥ CKD stage 3 ± proteinuria (374); 6 months | Intervention: mean 4.5 (SD 1.2) Control: mean 4.2 (SD 1.2) P = 0.019 |

| Biochemical parameters | |||

| Kidney function MESMI 2010 |

Serum creatinine | Adults, CKD, eGFR < 60 mL/min + diabetes (75); 6 months | Intervention: mean 128 (SD 6.4) Control: mean 130 (SD 15.5) P = NS |

| Kidney function TAKE‐IT 2014 |

Annualised change in eGFR | Adolescents, kidney transplant recipients (169); 12 months | Intervention: median ‐2.3 (95% CI ‐10.6 to 10.3) Control: median ‐3.3 (95% CI ‐7.7 to 3.7) P = 0.5 |

| Blood pressure | |||

| Blood pressure within guideline recommendations BRIGHT 2013 |

‐‐ | Adults, ≥ CKD stage 3 ± proteinuria (403); 6 months | RR 1.22 (95% CI 1.04 to 1.43) P = 0.002 Favouring eHealth intervention |

| Blood pressure within guideline recommendation Ishani 2016 |

‐‐ | Adults, CKD, eGFR < 60 mL/min (76); 12 months | RR 1.04 (95% CI 0.74 to 1.47) P = 0.8 |

| Diastolic blood pressure MESMI 2010 |

Higher readings indicate poorer control | Adults, CKD, < eGFR 60 mL/min + diabetes (75); 6 months | Intervention: mean reduction 2.25 (SD 8.7) Control: mean reduction 3.1 (SD 8.6) P = 0.681 |

| Systolic blood pressure MESMI 2010 |

Higher readings indicate poorer control | Adults, CKD, < eGFR 60 mL/min + diabetes (75); 6 months | Intervention: mean reduction 6.9 (SD 20.5) Control: mean reduction 3 (SD 16.7) P = 0.371 |

| Clinical end‐points | |||

| Adverse events TAKE‐IT 2014 |

including post‐transplant lymphoproliferative disorder, Epstein‐Barr virus infection, CMV, BK virus infection, influenza, other infection, vomiting/diarrhoea, surgery/procedure, other, hospitalisations | Adolescents, kidney transplant recipients (169); 12 months | Intervention: 12.9 Control: 12.7 P = 0.9 |

| Cholesterol control Ishani 2016 |

Serum LDL‐C < 100 mg/dL | Adults, CKD, eGFR < 60mL/min (76); 12 months | Intervention: 31/61 (51%) Control: 8/15 (53%) P = 0.9 |

| Composite end point Ishani 2016 |

Death, ED admissions, hospitalisations and admission to skilled nursing facility | Adults, CKD, eGFR < 60 mL/min (600); 12 months | HR 0.98 (95% CI 0.75 to 1.29), P = 0.9 Intervention: 208/450 (46.2%) Control: 70/150 (46.7%) |

| Diabetes control MESMI 2010 |

Serum HbA1c | Adults, CKD, eGFR < 60 mL/min + diabetes (75); 6 months | Intervention: median 7.5 (IQR 7 to 8.5) Control: median 7 (IQR 6 to 9) |

| Diabetes control Ishani 2016 |

Serum HbA1c < 8% | Adults, CKD, eGFR < 60mL/min (48); 12 months | Intervention: 14/33 (42%) Control: 3/33 (15%) P = 0.6 |

| Graft failure TAKE‐IT 2014 |

‐‐ | Adolescents, kidney transplant recipients (169); 12 months | Intervention: 0 Control: 0 |

| Graft rejection, acute TAKE‐IT 2014 |

‐‐ | Adolescents, kidney transplant recipients (169); 12 months | Intervention: 1.06 Control: 1.69 P = 0.3 |

| Healthcare utilisation BRIGHT 2013 |

Service use (Primary health care services, community health, social care, secondary healthcare services, out‐of‐pocket expenses, costs of loss of productivity) | Adults, ≥ CKD stage 3 ± proteinuria (374); 6 months | Intervention: mean 6.1 (SD 5.5) Control: mean 6.5 (SD 4.7) P = 0.455 |

| Healthcare utilisation Ishani 2016 |

Admission to skilled nursing facility | Adults, CKD, eGFR < 60mL/min (600); 12 months | HR 3.07 (95% CI 0.71 to 13.24) Intervention: 18/450 (4%) Control: 2/150 (1.3%) |

| Healthcare utilisation Li 2014b |

Clinic visits, 3 or more visits | Adults, PD (135); 12 weeks | Intervention: 3/69 (4.4%) Control: 5/66 (7.6%) P = 0.039 |

| Hospitalisations Schmid 2016 |

Unplanned admission rates to hospital or ED | Adults, kidney transplant recipients (26); 12 months | Intervention: mean 0 (SD 0.74) Control: mean 2 (SD 1.48) |

| Hospitalisations Ishani 2016 |

Unplanned admission rates to hospital or ED | Adults, CKD, eGFR < 60 mL/min (600); 12 months | RR 1.12 (95% CI 0.83 to 1.51) Intervention: 134/450 events Control: 40/150 events |

| Hospitalisations Li 2014b |

Unplanned admission rates to hospital or ED | Adults, PD (135); 12 weeks | RR 0.60 (95% CI 0.21 to 1.73) Intervention: 5/69 Control: 8/66 |

| Hospitalisations TAKE‐IT 2014 |

‐‐ | Adolescents, kidney transplant recipients (169); 12 months | Intervention: 4.96

Control: 5.38 P = 0.7 |

| Kidney function Ishani 2016 |

Initiation on dialysis | Adults, CKD, eGFR < 60 mL/min (600); 12 months | HR 1.86 (95%CI 0.41 to 8.39), P = NS Intervention: 11/450 (2.4%) Control: 2/150 (1.3%) |

| Rejection episodes Schmid 2016 |

Number of rejection episodes | Adults, kidney transplant recipients (46); 12 months |

Intervention: 1/23 Control: 2/23 |

| Smoking status Ishani 2016 |

Number participants quit smoking | Adults, CKD, eGFR < 60 mL/min (52); 12 months | Intervention: 9/40 (23%) Control: 5/12 (42%) P = 0.3 |

| Medication adherence | |||

| Medication adherence Schmid 2016 |

% compliant according to composite adherence score | Adults, kidney transplant recipients (26); 12 months | RR 1.90 (95% CI 1.15 to 3.14), P = 0.013 Intervention: 19/23 Control: 10/23 |

| Medication adherence MESMI 2010 |

Pill counts to determine a score | Adults, CKD, eGFR < 6o mL/min + diabetes (75); 6 months | Intervention: mean 58.4 (SD 24.3) control: mean 66.6 (SD 22.2) P = 0.162 |

| Medication adherence Russell 2011 |

Medication Event Monitoring System used to record opening of bottles | Adults, kidney transplant recipients (13); 6 months |

Intervention: mean 0.88 (SD 0.09) Control: mean 0.77 (SD 0.06) P = 0.0396 |

| Medication adherence TAKE‐IT 2014 |

Perfect taking adherence was defined as taking all prescribed daily doses | Adolescents, kidney transplant recipients (169); 12 months | OR 1.50 (95% CI 1.06 to 2.12) In favour of eHealth intervention |

| Medication adherence TAKE‐IT 2014 |

Self‐reported using the Medical Adherence Measure Medication Module (MAM‐MM) | Adolescents, kidney transplant recipients (169) 12 months |

Taking adherence Intervention: 98.3 (SD 4.5) Control: 97.1 (SD 6.0) P = 0.2 Timing adherence Intervention: 95 (SD 7.9) Control: 92.9 (SD 9.3) P = 0.2 |

| Medication adherence TAKE‐IT 2014 |

Standard deviation of tacrolimus trough concentrations during intervention interval | Adolescents, kidney transplant recipients (169); 12 months | Intervention: 1.6 (CI 0.9 to 2.5) Control: 1.4 (CI 0.9 to 2.1) P = 0.5 |

| Medication motivation BRIGHT 2013 |

Modified Morisky’s Medication Adherence Scale Higher score indicates higher medication motivation |

Adults, ≥ CKD stage 3 ± proteinuria (369); 6 months | Intervention: mean 2.7 (SD 0.6) Control: mean 2.7 (SD 0.5) P = 0.568 |

| Dietary intake | |||

| PD dietary problems Koprucki 2010 |

Self‐reported questionnaire Unclear whether higher or lower scores represent an improvement in dietary problems |

Adults, PD (19); 4 months | Intervention: mean ‐10.5 points (SD 16.2) Control: mean +0.5 points (SD 20.1) P = 0.194 |

| Quality of Life | |||

| Anxiety BRIGHT 2013 |

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS‐A) Higher score indicate more anxiety |

Adults, ≥ CKD stage 3 ± proteinuria (345); 6 months | Intervention: mean 4.6 (SD 3.7) Control: mean 5.2 (SD 4.1) P = 0.06 |

| Anxiety iDiD 2016 |

Generalised Anxiety Disorder questionnaire Higher score indicate more anxiety |

Adults, HD (25); 3 months | Intervention: mean 4.4 (SD 4.1) Control: mean 3.9 (SD 3.6) |

| Anxiety Kargar Jahromi 2016 |

Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) Higher scores indicate worse anxiety |

Adults, HD (54); 1 month | Intervention: mean 8.68 (SD 0.9) Control: mean 16.72 (SD 1.98) P = 0.01 |

| Anxiety Reilly‐Spong 2015 |

State‐Trait Anxiety Inventory Higher scores indicate worse anxiety |

Adults, kidney transplant recipients (42); 2 months |

Intervention: mean 41.2 (SD 15.3) Control: mean 38.1 (SD 11.6) P = 0.55 |

| Burden Li 2014b |

KDQoL Higher scores indicate improved quality of life |

Adults, PD (135); 12 weeks | Intervention: mean 21.5 (SD 11.7) Control: mean 21.1 (SD 12.2) P = 0.86 |

| Cognitive function Li 2014b |

KDQoL Higher scores indicate improved quality of life |

Adults, PD (135); 12 weeks | Intervention: mean 74.2 (SD 15.7) Control: mean 76.8 (SD 16.5) P = 0.35 |

| Depression iDiD 2016 |

Patient Health Questionnaire – 9 Higher scores indicate more depressive symptoms |

Adults, HD (23); 3 months | Intervention: mean 7.5 (SD 5.4) Control: mean 7.6 (SD 4.7) |

| Depression Kargar Jahromi 2016 |

Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) Higher scores indicate worse anxiety |

Adults, HD (54); 1 month | Intervention: mean 8.96 (SD .17) Control: mean 16.2 (SD 1.6) |

| Depression Reilly‐Spong 2015 |

Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale Higher score indicate more symptoms |

Adults, kidney transplant recipients (51) 2 months |

Intervention: mean 14.7 (SD 9.4) Control: mean 9.1 (SD 5.8) P = 0.05 |

| Effects Li 2014b |

KDQoL Higher scores indicate improved quality of life |

Adults, PD (135); 12 weeks | Intervention: mean 63.2 (SD 14.2) Control: mean 62.1 (SD 14.3) P = 0.63 |

| Emotional well‐being BRIGHT 2013 |

heiQ Higher score indicates higher negative affect |

Adults, ≥ CKD stage 3 ± proteinuria (374); 6 months | Intervention: mean 31.4 (SD 22.2) Control: mean 34 (SD 22.2) P = 0.329 |

| Fatigue BRIGHT 2013 |

Medical Outcomes Survey, energy and vitality Higher score indicates more energy and vitality |

Adults, ≥ CKD stage 3 ± proteinuria (373); 6 months | Intervention: mean 52.4 (SD 22) Control: mean 50.8 (SD 21.8) P = 0.082 |

| Fatigue Li 2014b |

KDQoL Higher scores indicate improved quality of life |

Adults, PD (135); 6 weeks | Intervention: mean 48.4 (SD 17.7) Control: mean 43.3 (SD 18.9) P = 0.02 |

| Fatigue Reilly‐Spong 2015 |

Patient‐Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System – Fatigue Higher score indicate more symptoms |

Adults, kidney transplant recipients (38); 2 months | Intervention: mean 57 (SD 6.3) Control: mean 56.6 (SD 8.4) P = 0.65 |

| General health perception BRIGHT 2013 |

SF‐36 Higher scores indicate higher QoL |

Adults, ≥ CKD stage 3 ± proteinuria (372); 6 months | Intervention: mean 2.8 (SD 1.0) Control: 2.8 (SD 0.9) P = 0.832 |

| General health perception Li 2014b |

KDQoL‐SF Higher scores indicate higher QoL |

Adults, PD (135); 12 weeks | Intervention: mean 38.2 (SD 17.5) Control: mean 35.7 (SD 17.7) P = 0.41 |

| Health services navigation BRIGHT 2013 |

Health Education Impact Questionnaire | Adults, ≥ CKD stage 3 ± proteinuria (372); 6 months | Intervention: mean 70.5 (SD 16.2) Control: mean 69.4 (SD 15.9) P = 0.226 |

| Hope Poorgholami 2016a |

Miller’s questionnaire of hope Higher score indicates greater hopefulness |

Adults, HD (75); 2 months | Intervention: mean 187.0 (SD 11.46) Control 1: mean 170.96 (SD 7.99) Control 2: mean 91.16 (SD 11.06) P < 0.05 Significant improvement in the intervention group compared to both control groups |

| Loneliness BRIGHT 2013 |

UCLA Loneliness Scale Higher score indicates lower loneliness |

Adults, ≥ CKD stage 3 ± proteinuria (369); 6 months | Intervention: mean 30.3 (SD 5.3) Control: mean 31 (SD 4.4) P = 0.861 |

| Mental component score Reilly‐Spong 2015 |

SF‐12 Higher score indicates higher quality of life |

Adults, kidney transplant recipients (63); 2 months | Intervention: mean 49.7 (SD 10) Control: mean 46.7 (SD 9.8) P = 0.01 |

| Mental health BRIGHT 2013 |

Medical Outcomes Survey, psychological well being Higher score indicates higher psychological well being |

Adults, ≥ CKD stage 3 ± proteinuria (372); 6 months | Intervention: mean 74.7 (SD 18.8) Control: mean 74 (SD 19.9) P = 0.286 |

| Mental health Li 2014b |

KDQoL Higher scores indicate improved quality of life |

Adults, PD (135); 6 weeks | Intervention: mean 65.4 (SD 17.2) Control: mean 63.5 (SD 18.6) P = 0.77 |

| Mobility iDiD 2016 |

EQ‐5D Higher score indicates reduced mobility |

Adults, HD (25); 3 months | Intervention: mean 1.5 (SD 0.8) Control: mean 2.4 (SD 1.5) P = NS |

| Mood iDiD 2016 |

EQ‐5D Higher score indicates lower mood |

Adults, HD (25); 3 months | Intervention: mean 1.5 (SD 0.8) Control: mean 2.0 (SD 1.0) |

| Quality of life (global score) BRIGHT 2013 |

EQ‐5D Higher scored indicates reduced quality of life |

Adults, CKD ≥ stage 3 ± proteinuria (372); 6 months | Intervention: mean 0.71 (SD 0.28) Control: mean 0.67 (SD 0.29) P = 0.027 |

| Physical component score Reilly‐Spong 2015 |

SF‐12 Higher score indicates higher quality of life |

Adults, kidney transplant recipients (63); 2 months | Intervention: mean 33.2 (SD 9.8) Control: mean 38.5 (SD 10.4) P =0.96 |

| Physical functioning Li 2014b |

KDQoL‐SF Higher scores indicate higher QoL |

Adults, PD (135); 12 weeks | Intervention: mean 53.9 (SD 12.9) Control: mean 51.5 (SD 12.5) P = 0.28 |

| Pain iDiD 2016 |

EurQoL EQ‐5D Higher scores indicate more pain |

Adults, HD (18); 3 months | Intervention: mean 1.6 (SD 0.8) Control: mean 2.6 (SD 1.3) P = NS |

| Pain Li 2014b |

KDQoL‐SF Higher scores indicate less pain |

Adults, PD (135); 12 weeks | Intervention: mean 64.2 (SD 18.2) Control: mean 59.7 (SD 18.9) P = 0.16 |

| Pain Reilly‐Spong 2015 |

SF‐12 Higher scores indicate less pain |

Adults, kidney transplant recipients (38); 2 months | Intervention: mean 39.9 (SD 13.9) Control: 44.7 (SD 10.4) P = 0.94 |

| Patient satisfaction Li 2014b |

KDQoL Higher scores indicate improved quality of life |

Adults, PD (135); 12 weeks | Intervention: mean 75.9, SD 13.8 Control: mean 71.3 (SD 12.3) P = 0.04 |

| Positive and active engagement in life BRIGHT 2013 |

heiQ Higher score indicates higher engagement with life |

Adults, ≥ CKD stage 3 ± proteinuria (374); 6 months | Intervention: mean 66.4 (SD 19.7) Control: mean 66.5 (SD 17.6) P = 0.999 |

| Quality social interaction Li 2014b |

KDQoL Higher scores indicate improved quality of life |

Adults, PD (135); 12 weeks | Intervention: mean 73.2 (SD 15.1) Control: mean 71.7 (SD 14.1) P = 0.56 |

| Role, emotional Li 2014b |

KDQoL Higher scores indicate improved quality of life |

Adults, PD (135); 6 weeks | Intervention: mean 56.3 (SD 14.8) Control: mean 56.6 (SD 16.5) P = 0.77 |

| Role, physical Li 2014b |

KDQoL‐SF Higher scores indicate higher QoL |

Adults, PD (135); 12 weeks | Intervention: mean 20.8 (SD 16.9) Control: mean 20.4 (SD 15.1) P = 0.91 |

| Self‐monitoring and insight BRIGHT 2013 |

heiQ Higher score indicates higher self‐monitoring and insight |

Adults, ≥ CKD stage 3 ± proteinuria (374); 6 months | Intervention: mean 70.7 (SD 12.2) Control: mean 70.7 (SD 11.5) P = 0.644 |

| Sexual function Li 2014b |

KDQoL Higher scores indicate improved quality of life |

Adults, PD (135); 12 weeks | Intervention: mean 83.7 (SD 16.4) Control: mean 78.4 (SD 15.5) P = 0.05 |

| Side effects from corticosteroids, cardiac and kidney dysfunction Schmid 2016 |

End‐stage renal disease symptom checklist (ESRD‐SCL) Higher score indicate improved quality of life |

Adults, kidney transplant recipients (46); 12 months | Intervention: median 0 (IQR 0.2) Control: median 0.4 (IQR 0.6) P = 0.004 |

| Skills and technique acquisition BRIGHT 2013 |

heiQ Higher score indicates higher skills and technique acquisition |

Adults, ≥ CKD stage 3 ± proteinuria (369); 6 months | Intervention: mean 65.4 (SD 14.6) Control: mean 65.0 (SD 13.1) P = 0.218 |

| Social network (illness) BRIGHT 2013 |

heiQ Higher score = greater help with illness from social network |

Adults, ≥ CKD stage 3 ± proteinuria (342); 6 months | Intervention: mean 10.3 (SD 8.4) Control: mean 11.5 (SD 9) P = 0.208 |

| Social network (practical) BRIGHT 2013 |

heiQ Higher score = greater help with practical work from social network |

Adults, ≥ CKD stage 3 ± proteinuria (342); 6 months | Intervention: mean 6.2 (SD 6.2) Control: mean 8.1 (SD 7.1) P = 0.017 |

| Social support Li 2014b |

KDQoL Higher scores indicate improved quality of life |

Adults, PD (135); 12 weeks | Intervention: mean 74.1 (SD 14.7) Control: mean 73.2 (SD 15.1) P = 0.73 |

| Self‐care iDiD 2016 |

EQ‐5D Higher score indicates reduced self‐care |

Adults, HD (25); 3 months | Intervention: mean 1.2 (SD 0.6) Control: mean 1.4 (SD 0.9) P = NS |

| Sleep Li 2014b |

KDQoL‐SF Higher score indicates better sleep |

Adults, PD (160); 6 weeks | Intervention: mean 61.1 (SD 20.6) Control: mean 54.3 (SD 18.1) P = 0.1 |

| Sleep Reilly‐Spong 2015 |

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index Lower score indicates better sleep quality |

Adults, kidney transplant recipients (63); 2 months | Intervention: mean 7.3 (SD 4.7) Control: 6.1 (SD 3.4) P = 0.65 |

| Social capital BRIGHT 2013 |

heiQ Higher score indicates increased satisfaction with opportunities to participate in the community |

Adults, ≥ CKD stage 3 ± proteinuria (366); 6 months | Intervention: mean 3.7 (SD 0.8) Control: mean 3.6 (SD 0.8) P = 0.325 |

| Social integration BRIGHT 2013 |

heiQ Higher score indicates higher social integration |

Adults, ≥ CKD stage 3 ± proteinuria (371); 6 months | Intervention: mean 69.6 (SD 20.3) Control: mean 69.4 (SD 15.6) P = 0.537 |

| Social network (emotional) BRIGHT 2013 |

heiQ Higher score indicates greater help with emotional work from social network |

Adults, ≥ CKD stage 3 ± proteinuria (345); 6 months | Intervention: mean 13.4 (SD 10.4) Control: mean 14.9 (SD 11.4) P = 0.463 |

| Social functioning BRIGHT 2013 |

Medical Outcomes Survey, social/role activities limitations Higher score indicates lower social limitation |

Adults, ≥ CKD stage 3 ± proteinuria (371(; 6 months | Intervention: mean 73.2 (SD 28.2) Control: mean 68.7 (SD 30.5) P = 0.492 |

| Social functioning Li 2014b |

KDQoL Higher scores indicate improved quality of life |

Adults, PD (135); 6 weeks | Intervention: mean 42.5 (SD 19.3) Control: mean 43.4 (SD 18.8) P = 0.43 |

| Staff encouragement Li 2014b |

KDQoL Higher scores indicate improved quality of life |

Adults, PD (135); 12 weeks | Intervention: mean 87.3 (SD 12.8) Control: mean 81.2 (SD 15.1) P = 0.01 |

| Stress Kargar Jahromi 2016 |

Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) Higher score indicates higher stress |

Adults, HD (54); 1 month | Intervention: mean 8.36 (SD 1.03) Control: mean 13.76 (SD 1.44) P = 0.001 |

| Symptoms/problems Li 2014b |

KDQoL Higher scores indicate improved quality of life |

Adults, PD (135); 12 weeks | Intervention: mean 72.8 (SD 15) Control: mean 68.6 (SD 6.2) P = 0.08 |

| Usual activities iDiD 2016 |

EQ‐5D Higher scores indicate reduced ability to complete usual activities |

Adults, HD (25); 3 months | Intervention: mean 1.5 (SD 0.8) Control: mean 2.8 (SD 1.3) P = NS |

| Work status Li 2014b |

KDQoL Higher scores indicate improved quality of life |

Adults, PD (135); 12 weeks | Intervention: mean 17.3 (SD 11.6) Control: mean 14.8 (SD 9.9) P = 0.19 |

CI ‐ confidence interval; CKD ‐ chronic kidney disease; eGFR ‐ estimated glomerular filtration rate; HD ‐ haemodialysis; HR ‐ hazard ratio; IQR ‐ interquartile range; NS ‐ not significant; PD ‐ peritoneal dialysis; RR ‐ risk ratio; SD ‐ standard deviation

6. Descriptive analyses of reported outcomes for clinical‐decision aid interventions.

| Outcome Study ID | Outcome measure | Study population (No. of participants); study duration | Results |

| Behavioural | |||

| Knowledge iChoose 2016 |

9 item scale, unvalidated | Adults, ESKD (443); 1 clinic appointment | Intervention: mean 6.11 (SD 1.91) Control: mean 5.48 (SD 1.87) P < 0.001 |

| Biochemical parameters | |||

| Serum parathyroid hormone Cooney 2015 |

‐‐ | Adults, eGFR < 45 mL/min or eGFR < 60 mL/min in past 90 days to 2 years (2199); 12 months | Intervention: 502/1070 (46.9%) Control: 182/1129 (16.1%) P < 0.001 |

| Serum phosphate Cooney 2015 |

‐‐ | Adults, eGFR < 45 mL/min or eGFR < 60 mL/min in past 90 days to 2 years (2199); 12 months | Intervention: 680/1070 (63.6%) Control: 527/1129 (46.7%) P < 0.001 |

| Blood pressure | |||

| Blood pressure within guideline recommendations Cooney 2015 |

‐‐ | Adults, eGFR < 45 mL/min or eGFR < 60 mL/min in past 90 days to 2 years (947); 12 months | RR 1.02 (95% CI 0.87 to 1.19) P = 0.84 |

| Management of hypertension Cooney 2015 |

Number of anti‐hypertensive medications | Adults, eGFR < 45 mL/min or eGFR < 60 mL/min in past 90 days to 2 years (2199); 12 months |

0 medications Intervention: 37 (7.8%), control: 65 (13.7%) 1 medication Intervention 52 (11%), control: 63 (13.3%) 2 medications Intervention 128 (27%), control: 105 (22.2%) 3 medications Intervention: 135 (28.5%), control: 121 (25.6%) 4+ medications Intervention: 122 (25.7%), control: 119 (25.2%) |

| Systolic blood pressure Cooney 2015 |

Higher readings indicate poorer control | Adults, eGFR < 45 mL/min or eGFR < 60 mL/min in past 90 days to 2 years (947); 12 months | Intervention: mean 135.1 (SD 17.4) Control: mean 134.4 (SD 17.6) P = 0.57 |

| Clinical end‐points | |||

| Access to kidney transplantation iChoose 2016 |

Composite score of transplant access (at least one of following outcomes: wait‐list, deceased, deceased or living donor transplant, 1 living donor inquiry) |

Adults, ESKD (443); 1 clinic appointment | Intervention: 168/226 (74.3%) Control: 155/216 (71.4%) |

| Healthcare utilisation Durand 2000 |

Frequency of planned medical visits | Adults, PD (30); intervention 9.5 months, control 7.8 months | Intervention: 1/41 days Control: 1/33 days |

| Hospitalisations Durand 2000 |

‐‐ | Adults, PD (30); intervention 9.5 months, control 7.8 months | RR 0.67 (95% CI 0.34 to 1.29) Intervention: 14/365 events Control: 21/365 events |

| Kidney function Cooney 2015 | Urine albumin creatinine ratio | Adults, eGFR < 45 mL/min or eGFR < 60 mL/min in past 90 days to 2 years (2199); 12 months | Intervention: 602/1070 (56.3%) Control: 435/1129 (38.5%) P < 0.001 |

| Kidney function Cooney 2015 |

Progression to ESKD (dialysis or transplantation) | Adults, eGFR < 45 mL/min or eGFR < 60 mL/min in past 90 days to 2 years (2199); 12 months | Intervention: 26/1070 (2.4%) Control: 20/1129 (1.8%); P =0.28 |

| Medication usage Cooney 2015 |

Prescribed appropriate medications | Adults, eGFR < 45 mL/min or eGFR < 60 mL/min in past 90 days to 2 years (2199); 12 months |

ACEI/ARB Intervention: 309/481 (64.2%) Control: 298/483 (61.7%) P = 0.41 Phosphate binder Intervention: 24/107 (22.4%) Control: 19/81 (23.5%) P = 0.87 Vitamin D Intervention: 310/501 (61.9%) Control: 218/416 (52.4%) P = 0.004 Bicarbonate Intervention: 31/132 (24%) Control: 18/137 (13%) P = 0.03 |

| Medication adherence | |||

| Medication adherence Cooney 2015 |

Morisky Medication Adherence Scale Higher scores indicate better adherence |

Adults, eGFR < 45 mL/min or eGFR < 60 mL/min in past 90 days to 2 years (2199); 12 months | Intervention: mean 6.7 (SD 1.2) Control: mean 6.8 (SD 1.2) P = 0.7 |

| Medication adherence Hardstaff 2002 |

Pill counts | Adults, kidney transplant recipients (91) | RR 0.72 (95% CI 0.42 to 1.15) Intervention: 26/67 Control: 13/24 |

| Quality of Life | |||

| Burden Cooney 2015 |

KDQoL Higher scores indicate improved quality of life |

Adults, eGFR < 45 mL/min or eGFR < 60 mL/min in past 90 days to 2 years (2199); 12 months | Intervention: mean 89.7 (SD 20.5) Control: mean 89.4 (SD 19.6) P = 0.93 |

| Effects Cooney 2015 |

KDQoL Higher scores indicate improved quality of life |

Adults, eGFR < 45 mL/min or eGFR < 60 mL/min in past 90 days to 2 years (2199); 12 months | Intervention: mean 94.2 (SD 11.9) Control: mean 94.4 (SD 14) P = 0.92 |

| Mental component score Cooney 2015 |

SF‐12 Higher score indicates higher quality of life |

Adults, eGFR < 45 mL/min or eGFR < 60 mL/min in past 90 days to 2 years (2199); 12 months | Intervention: mean 52 (SD 10.6) Control: mean 52.1 (SD 9.6) P = 0.9 |

| Physical component score Cooney 2015 |

SF‐12 Higher score indicates higher quality of life |

Adults, eGFR < 45 mL/min or eGFR < 60 mL/min in past 90 days to 2 years (2199); 12 months | Intervention: mean 39.3 (SD 9.8) Control: mean 36.8 (SD 10.3) P = 0.15 |

ACEi/ARB ‐ angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker; eGFR ‐ estimated glomerular filtration rate; ESKD ‐ end‐stage kidney disease; PD ‐ peritoneal dialysis; RR ‐ risk ratio; SD ‐ standard deviation

7. Descriptive analyses of reported outcomes for mixed interventions.

| Outcome Study ID | Outcome measure |

Study population (no. of Participants); study duration |

Results |

| Behavioural | |||

| Attitudes towards performing a behaviour Robinson 2014a |

Attitude: importance of sun protection Higher score indicates higher importance |

Adults, kidney transplant recipients (101); 6 weeks |

Intervention: mean 7 (SD 12) Control: mean 0 (SD 8.5) P = 0.003 |

| Attitudes towards performing a behaviour Robinson 2015 |

Attitude: importance of sun protection Higher score indicates higher importance |

Adults, kidney transplant recipients (170); 6 weeks | Intervention: mean 6.59 (SD 3.87) Control: mean 1.07 (SD 0.705) P < 0.05 |

| Knowledge Robinson 2014a |

Knowledge of skin cancer and sun protection (self‐reported, validated tool | Adults, kidney transplant recipients (103); 6 weeks | Intervention: mean 9 (SD 6.75) Control: mean 0 (SD 6.75) P = 0.015 |

| Knowledge Robinson 2015 |

Knowledge of skin cancer and sun protection (self‐reported, validated tool) | Adults, kidney transplant recipients (170); 6 weeks | Intervention: mean 6.66 (SD 2.57) Control: mean 3.67 (SD 1.73) P = 0.04 |

| Self‐care behaviours Robinson 2014a |

Sun protection performed Higher score indicates more sun protection behaviours performed |

Adults, kidney transplant recipients (101); 6 weeks | Intervention: mean 12.5 (SD 19.6) Control: mean 2.5 (SD 17.5) P = 0.013 |

| Self‐care behaviours Robinson 2015 |

Sun protection performed Higher score indicates more sun protection behaviours performed |

Adults, kidney transplant recipients (170); 6 weeks | Intervention: mean 57.7 (SD 13.08) Control: mean 31.1 (SD 4.87) P = 0.013 |

| Willingness to perform a behaviour Robinson 2014a |

Willingness to use sun protection Higher scores indicate more willingness |

Adults, kidney transplant recipients (101); 6 weeks | Intervention: mean 8 (SD 25) Control: mean 0 (SD 34.5) P = 0.137 |

| Willingness to perform a behaviour Robinson 2015 |

Willingness to use sun protection Higher scores indicate more willingness |

Adults, kidney transplant recipients (170); 6 weeks | Intervention: mean 74.64 (SD 21.4) Control: mean 22.64 (SD 1.65) P = 0.09 |

| Biochemical parameters | |||

| Kidney function Navaneethan 2017 |

Measurement of serum creatinine | Adults, CKD, eGFR 15 to 45 mL/min (209); 24 months | Intervention: 42/50 (84%) Control: 57/57 (100%) P = 0.001 |

| Serum parathyroid hormone Navaneethan 2017 |

‐‐ | Adults, CKD, eGFR 15 to 45 mL/min (209); 24 months | Intervention: 22/50 (44%) Control: 33/57 (58%) P = 0.34 |

| Serum phosphate Navaneethan 2017 |

‐‐ | Adults, CKD, eGFR 15 to 45 mL/min (209); 24 months | Intervention: 28/50 (56%) Control: 39/57 (68%) P = 0.52 |

| Measurement of 25‐hydroxy Vitamin D Navaneethan 2017 |

‐‐ | Adults, CKD, eGFR 15 to 45 mL/min (209); 24 months | Intervention: 28/50 (56%) Control: 37/57 (65%) P = 0.31 |

| Blood pressure | |||

| Blood pressure within guideline recommendations Navaneethan 2017 | ‐‐ | Adults, CKD, eGFR 15 to 45 mL/min (209); 24 months | RR 0.97 (95% CI 0.86 to 1.09) P = 0.98 |

| Clinical end‐points | |||

| Cholesterol control Navaneethan 2017 |

Measurement of serum LDL‐C | Adults, CKD, eGFR 15 to 45 mL/min (209); 24 months | Intervention: 39/50 (78%) Control: 48/57 (84%) P = 0.36 |

| Diabetes control Navaneethan 2017 |

Measurement of serum HbA1c | Adults, CKD, eGFR 15 to 45 mL/min (209); 24 months | Intervention: 19/29 (79%) Control: 29/29 (100%) P = 0.02 |

| Hospitalisations Navaneethan 2017 |

Unplanned admission rates to hospital or emergency department | Adults, CKD, eGFR 15 to 45 mL/min (209); 24 months | Intervention: mean 4.06 (SD 14.11) Control: mean 2.29 (SD 9.09) P = 0.24 |

| Kidney function Navaneethan 2017 |

Urine albumin creatinine ratio | Adults, CKD, eGFR 15 to 45 mL/min (209); 24 months | Intervention: 19/50 (38%) Control: 25/57 (44%) P = 0.13 |

| Kidney function Navaneethan 2017 |

Progression to ESKD (dialysis or transplantation) | Adults, CKD, eGFR 15 to 45 mL/min (209); 24 months | Intervention: 4/50 (844%) Control: 1/57 (1.8%) P = 0.36 |

| Melanin index Robinson 2014a |

Spectrophotometry, right upper arm with sun protection | Adults, kidney transplant recipients (101); 6 weeks | Intervention: median ‐0.8 (range: ‐110 to 186) Control: median 5 (range: ‐193 to 108) P = 0.497 |

| Melanin index Robinson 2014a |

Spectrophotometry, right forearm with sun exposure | Adults, kidney transplant recipients (101); 6 weeks | Intervention: median 16.3 (range ‐113 to 132) Control: median 44 (range ‐56 to 317) P = 0.036 |

| Melanin index Robinson 2014a |

Spectrophotometry, cheek with sun exposure | Adults, kidney transplant recipients (101); 6 weeks | Intervention: median ‐1 (range: ‐59 to 240) Control: median 15 (range: ‐63 to 246) P = 0.114 |

| Sun damage Robinson 2014a |

Personnel assessment, right forearm | Adults, kidney transplant recipients (101); 6 weeks | Intervention: median 0 (range: ‐4 to 2) Control: median 2 (range: ‐5 to 8) P = 0.031 |

| Medication adherence | |||

| Medication adherence Reese 2017 |

Serum tacrolimus | Adults, kidney transplant recipients (117); 6 months | Intervention 1: mean 8.7 (SD 2.7) Intervention 2: mean 8.08 (SD 1.56) Control: mean 8.38 (SD 1.67) P = 0.4 |

| Medication adherence Reese 2017 |

Co‐efficient of variation for tacrolimus levels | Adults, kidney transplant recipients (117); 6 months | Intervention 1: mean 0.23 (SD 0.18) Intervention 2: mean 0.21 (SD 0.15) Control: mean 0.24 (SD 0.15) P = 0.7 |

| Medication adherence Reese 2017 |

% tacrolimus levels within range | Adults, kidney transplant recipients (117); 6 months | Intervention 1: mean 0.35 (SD 0.32) Intervention2: mean 0.37 (SD 0.26) Control: mean 0.42 (SD 0.3) P = 0.6 |

| Medication adherence Reese 2017 |

% of days bottles opened at correct times | Adults, kidney transplant recipients (117); 6 months | RR 1.41 (95% CI 1.21 to 1.65); P < 0.00 Intervention 1: 140/180 Intervention 2: 158/180 Control: 99/180 |

CI ‐ confidence interval; CKD ‐ chronic kidney disease; eGFR ‐ estimated glomerular filtration rate; ESKD ‐ end‐stage kidney disease; RR ‐ risk ratio; SD ‐ standard deviation

2.

Bubble plot of reported outcomes by intervention type

Excluded studies

Nine studies (27 reports) were excluded during title and full text screening. The reasons for exclusion were study population did not have CKD (Abdel‐Kader 2011; Korus 2017; RaDIANT 2014; Roberto 2009; Wilson 2014), interventions did not include eHealth (Chen 2011e; SMILE 2010) and the wrong study design (Morales‐Barria 2016; Warren 2009).

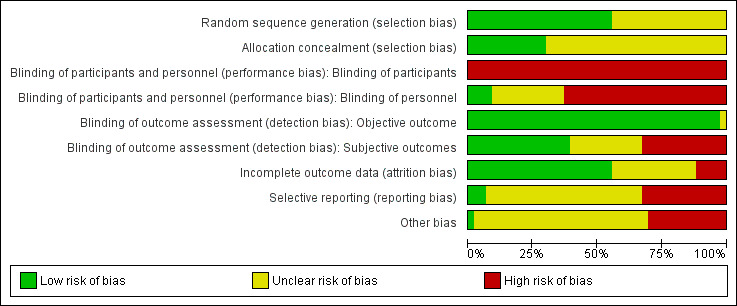

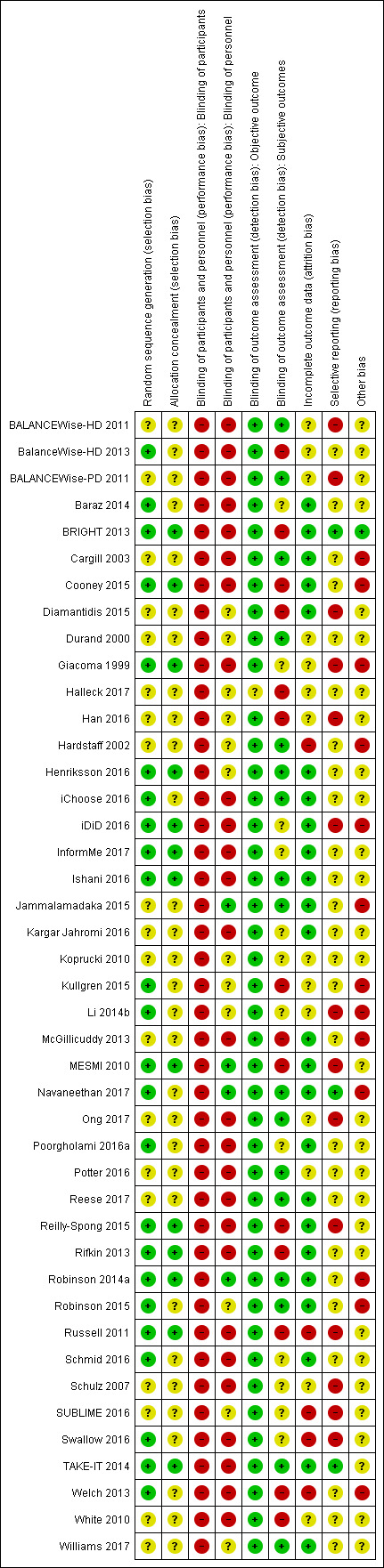

Risk of bias in included studies

Figure 3 provides a summary of the risk of bias for the included studies with the study‐level data provided in Figure 4. Methodological quality varied considerably, with many studies providing insufficient information to accurately assess the risk of bias.

3.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

4.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Random sequence generation