Abstract

MYC is a master transcriptional regulator that controls almost all cellular processes. Over the last several decades, researchers have strived to define the context-dependent transcriptional gene programs that are controlled by MYC, as well as the mechanisms that regulate MYC function, in an effort to better understand the contribution of this oncoprotein to cancer progression. There are a wealth of data indicating that deregulation of MYC activity occurs in a large number of cancers and significantly contributes to disease progression, metastatic potential, and therapeutic resistance. Although the therapeutic targeting of MYC in cancer is highly desirable, there remain substantial structural and functional challenges that have impeded direct MYC-targeted drug development and efficacy. While efforts to drug the ‘undruggable’ may seem futile given these challenges and considering the broad reach of MYC, significant strides have been made to identify points of regulation that can be exploited for therapeutic purposes. These include targeting the deregulation of MYC transcription in cancer through small-molecule inhibitors that induce epigenetic silencing or that regulate the G-quadruplex structures within the MYC promoter. Alternatively, compounds that disrupt the DNA-binding activities of MYC have been the long-standing focus of many research groups, since this method would prevent downstream MYC oncogenic activities regardless of upstream alterations. Finally, proteins involved in the post-translational regulation of MYC have been identified as important surrogate targets to reduce MYC activity downstream of aberrant cell stimulatory signals. Given the complex regulation of the MYC signaling pathway, a combination of these approaches may provide the most durable response, but this has yet to be shown. Here, we provide a comprehensive overview of the different therapeutic strategies being employed to target oncogenic MYC function, with a focus on post-translational mechanisms.

Key Points

| MYC deregulation occurs in a large number of tumors across multiple tissue types, making this oncogenic master transcription factor a highly desirable therapeutic target. |

| Genetic models indicate that MYC inhibition may be well-tolerated and lead to sustainable tumor regression. |

| Despite lacking targetable structural domains, several novel therapeutic strategies have emerged in an attempt to inhibit MYC activity clinically, including inhibition of transcriptional and post-translational regulatory events. |

Introduction

In an attempt to move away from toxic and non-specific chemotherapeutic agents, a global effort to develop targeted therapeutic strategies to inhibit oncogenic drivers has dominated the cancer biology field. By interrogating tumor cells at the DNA, RNA, and protein level, we have been able to identify specific cancers or cancer subtypes where a significant percentage of patients express a dominant oncogenic driver. In these cases, researchers have shown that the loss of this dominant driver leads to tumor cell death, and multiple targeted therapeutic agents based on this principle have shown great clinical success. For example, the BCR/ABL1 inhibitor Gleevac® has increased the 8-year survival of patients with chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) from 6 to ~ 90% and represents one of the most successful targeted kinase inhibitors to date [1]. Similarly, HER2 (human epidermal growth factor receptor 2) overexpression or amplification has been shown to occur in ~ 20% of breast cancer patients and anti-HER2 therapies such as trastuzumab and lapatinib have significantly increased patient survival in this subset of patients [2]. These clinical successes have helped fuel translational studies and highlight the potential of utilizing targeted therapies in the clinic. Unfortunately, a large number of tumors are driven by a small number of common oncogenic proteins that lack structural regions amenable to therapeutic inhibition [3, 4]. Prototypic examples of this are KRAS and MYC, where mutational activation and deregulated oncogenic expression are common driver events in cancer progression in many tissues and, therefore, these oncoproteins are considered highly desirable therapeutic targets [3, 5–7]. However, despite their significant contribution to disease states, these factors are commonly thought to be ‘undruggable’. The generation of therapeutic compounds that could effectively target these drivers would significantly alter the clinical outcome of an extraordinary number of patients. Here we review the biology of MYC deregulation in cancer that supports innovative strategies for therapeutic targeting and the potential for translating these strategies to the clinic.

MYC Deregulation in Cancer

The MYC transcription factor family consists of c-, L-, and N-MYC. The aberrant expression or activity of any one of these family members has been shown to contribute to tumor development, although the latter two seem to be restricted to specific tissues, most prominently lung and neural, respectively [8–11]. MYC family proteins function as potent transcription factors that regulate multiple cellular processes, including proliferation, differentiation, adhesion, and survival [9, 10, 12]. Several studies have demonstrated that MYC functions as a master transcriptional regulator, binding to the majority of regulated genes in the genome [10, 13, 14]. Given the prolific role of MYC in transcriptional regulation, expression of MYC proteins is tightly regulated at the transcriptional, translational, and post-translational levels in normal tissues, with a half-life of ~ 20 min [15, 16]. The major MYC protein domains include an N-terminal transactivation domain (TAD), MYC box domains (MB0-IV), a PEST domain (Proline, glutamic acid [E], Serine and Threonine rich), a nuclear localization sequence (NLS), and the carboxy-terminus basic-helix-loop-helix-leucine zipper (bHLHZ) [17–21]. Each of these domains facilitates interactions between MYC and a diverse set of binding partners in order to regulate MYC function and gene target specificity. The MB0-II domains are essential to MYC protein stability and activity, and facilitate MYC’s association with co-factors, such as PIN1, FBW7, and P-TEFb [19, 22–26]. MBIII and MBIV regulate the apoptotic function of MYC, as well as protein turnover [27–30]. Finally, the bHLHZ domain facilitates MYC’s interaction with its transcriptional co-factor MYC-associated protein X (MAX), allowing for DNA binding [8, 17, 18, 31]. Although the complex MYC interactome creates unique challenges for the development of MYC-specific inhibitors, each of these functional domains provides potential points of regulation that can be exploited to reduce the oncogenic function of MYC. Since all three MYC family proteins contain homology in these functional domains and their bHLHZ domains, several of the proposed therapeutic agents are likely to function against multiple MYC proteins.

The current dogma regards MYC amplification as the primary method by which MYC is deregulated in disease states. However, the post-translational regulation of MYC has emerged as an important mechanism, irrespective of amplification, by which MYC is stabilized and activated [32–34]. Research has identified two interdependent phosphorylation sites that are critical for the regulation of MYC stability and function. While these sites are conserved across MYC family members, we focus here on c-MYC (‘MYC’, unless otherwise specified). Downstream of growth-stimulatory signals, activation of the RAS/MEK/ERK cascade or cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) leads to the phosphorylation of MYC at Serine 62 (pS62-MYC) [32, 33, 35, 36]. This modification supports isomerization of Proline 63 in MYC from the trans to cis conformation by the phospho-serine/threonine-directed peptidyl-prolyl isomerase, PIN1, and these events increase MYC DNA binding and target gene regulation. Phosphorylation of Serine 62 (S62) also primes MYC for glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3)-mediated phosphorylation at Threonine 58 (pT58-MYC), which initiates MYC turnover. Dual phosphorylated MYC (pS62/pT58-MYC) then undergoes a second isomerization by PIN1, returning Proline 63 MYC to the trans conformation. This second isomerization event results in the association of MYC with the trans-specific phosphatase Protein Phosphatase 2A (PP2A), which dephosphorylates the stabilizing S62 residue and targets MYC for ubiquitin-mediated proteosomal degradation through the E3 ubiquitin ligase SCFFBW7 [33, 37–40]. Considering that MYC has a very short half-life, the balance of these phosphorylation and isomerization states provides controlled activity and rapid turnover of the MYC protein, allowing an expedited response to cellular signals while preventing the persistent expression of gene targets in normal cells.

It is now well-appreciated that a high percentage of cancers develop mechanisms to increase MYC activity in order to globally increase cell survival, proliferation, and invasiveness [9]. In disease states, studies have shown that aberrant MYC expression results in promoter invasion, with MYC binding to both high- and low-affinity consensus sequences, altering the expression of a large number of target genes [41, 42]. Consistent with these results, amplified or high Myc expression can drive tumorigenesis in multiple mouse models and MYC amplification is observed to various degrees in almost every human cancer type [11, 43]. Although amplification or overexpression of MYC commonly occurs in cancers, this is not the only mechanism by which MYC is deregulated. In fact, the majority of solid tumors do not display significant MYC amplification [44]. We and others find elevated levels of pS62-MYC and lower levels of pT58-MYC, consistent with a more active and stable form of MYC, in a large percentage of tested human tumors [33, 45–50]. Moreover, mutation of the Threonine 58 (T58) residue (MycT58A) results in constitutive S62 phosphorylation and increased tumorigenic potential compared to wild-type MYC [48, 51]. These studies suggest that the post-translational regulation of MYC in cancer may be wildly underestimated and play a significant role in tumor phenotypes. Importantly, in mouse models, low-level constitutive expression of Myc alone does not induce transformation, but rather exacerbates tumorigenic phenotypes when combined with oncogenes such as HER2 and mutant KRAS that can enhance S62 phosphorylation [51, 52]. Conversely, the genetic loss of Myc can prolong survival in aggressive KRAS-driven tumors, highlighting the contribution of endogenous MYC activity to oncogenic signaling pathways and supporting the rationale for therapeutic inhibition of MYC in a large number of cancers [52–55].

Given that MYC has been implicated in global gene regulation, one would predict that MYC suppression would result in large toxicities, with decreased proliferation and survival in normal cells. Surprisingly, the genetic inhibition of MYC in mice, through switchable transgenes or expression of a dominant negative form called OmoMYC, has resulted in dramatic losses of tumor phenotypes in lung adenocarcinomas, glioblastomas, skin papillomatosis, and pancreatic tumors with little to no toxicities [12, 54, 56–59]. OmoMYC is a mutated bHLHZ dimerization domain that is able to form OmoMYC homodimers that bind to DNA and compete with endogenous MYC:MAX complexes, reducing MYC promoter occupancy and effectively suppressing transcription. A recent study from Jung et al. [59] demonstrated that under physiologic levels of MYC, expression of recombinant OmoMYC protein minimally suppresses MYC at high-affinity binding sites. In contrast, the oncogenic, low-affinity MYC binding sites are acutely responsive to OmoMYC expression [59]. This study suggests that therapeutic targeting of oncogenic-specific MYC functions may be possible and highlight the importance of understanding the contribution of MYC signaling to oncogenic phenotypes.

Therapeutic Strategies to Target MYC

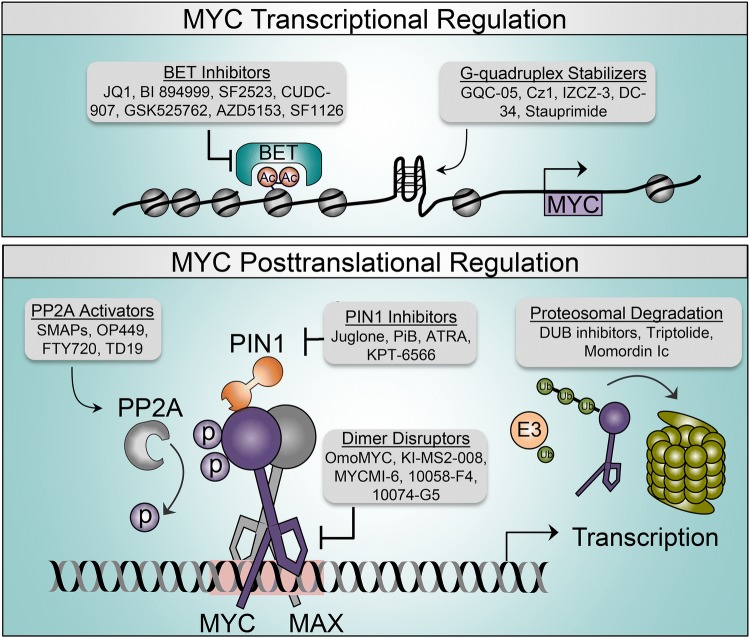

Studies have shown that transcription factors contain intrinsically disordered regions, which allow for the association with high- and low-affinity DNA binding sites and a diversity of co-factors [60, 61]. Additionally, these disordered regions are common sites for post-translational modifications, underscoring the importance of these mechanisms in regulating transcription factor function and stability [62]. Unfortunately, the inherent flexibility of transcription factors makes the direct therapeutic targeting of these proteins difficult, with most strategies relying on disrupting expression, protein–protein interactions, or DNA binding. Here we discuss the innovative strategies (Fig. 1) and therapeutic compounds (Tables 1 and 2) that have been proposed for the therapeutic targeting of MYC, including the inhibition of MYC transcription, partner protein dimerization, activating post-translational modifications, and turnover.

Fig. 1.

MYC regulatory pathways and therapeutic points of intervention. Transcriptional (top) and post-translational (bottom) mechanisms that regulate MYC function. Gray boxes indicate therapeutic categories and representative compounds that are being explored to negatively impact MYC activity. The pink box indicates the EBOX sequence. Ac acetylation, ATRA all-trans retinoic acid, BET bromodomain and extra-terminal motif, DUB deubiquinating enzyme, MAX MYC-associated protein X, p phosphorylation, PP2A Protein Phosphatase 2A, SMAPs small-molecule activators of Protein Phosphatase 2A, Ub ubiquitination

Table 1.

Targeting MYC transcriptional regulation

| Mechanism | Target | Compounds | Pre-clinical/clinical stage | Selected references |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epigenetic silencing | BET inhibitor | JQ1/TEN-010 | Pre-clinical with in vivo efficacy; phase I/II | [190–192] |

| BI 894999 | Phase I | [76, 193] | ||

| GSK525762 | Multiple phase I/II | [194–196] | ||

| AZD5153 | Phase I | [197–201] | ||

| ZEN-3694 | Phase I/II | [202, 203] | ||

| OTX015/MK-8628 | Phase I/II | [204–207] | ||

| PI3 K-BRD4 inhibitor | SF2523 | Pre-clinical with in vivo efficacy | [77, 208–211] | |

| SF1126 | Phase I | [77, 212, 213] | ||

| PI3 K-HDAC inhibitor | CUDC-907 | Multiple phase I/II | [78, 214, 215] | |

| G-quadruplexes | MYC | GQC-05 | Pre-clinical | [82] |

| Cz1 | Pre-clinical | [84] | ||

| IZCZ-3 | Pre-clinical with in vivo efficacy | [87] | ||

| DC-34 | Pre-clinical | [83] | ||

| Stauprimide | Pre-clinical with in vivo efficacy | [88] | ||

| MYC/RNA polymerase I | BMH-21 | Pre-clinical | [216] | |

| MYC/nucleolin | CX-3543 | Phase II | [217] |

BET bromodomain and extra-terminal motif, HDAC histone deacetylase, PI3 K phosphoinositide 3-kinase

Table 2.

Targeting MYC post-translational regulation

| Mechanism | Target | Compounds | Pre-clinical/clinical stage | Selected references |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MYC:MAX dimerization | MYC | OmoMYC | Pre-clinical with in vivo efficacy | [54, 57, 59, 99, 101, 218, 219] |

| MYCMI-6 | Pre-clinical with in vivo efficacy | [96] | ||

| Mycro3 | Pre-clinical with in vivo efficacy | [220] | ||

| 10058-F4 | Pre-clinical; minimal efficacy in vivo | [93, 221–224] | ||

| 10074-G5/JY-3-094 | Pre-clinical | [92, 225–227] | ||

| KJ-Pyr-9 | Pre-clinical with in vivo efficacy | [228] | ||

| KSI-3716 | Pre-clinical with in vivo efficacy | [229, 230] | ||

| MAX | KI-MS2-008 | Pre-clinical with in vivo efficacy | [98] | |

| PP2A activation | SET inhibitor | OP449 | Pre-clinical with in vivo efficacy | [47, 49, 133, 140, 231–234] |

| FTY720/OSU-2S/MP07-66/SH-RF-177/SPS-7 | Fingolimod FDA approved in multiple sclerosis, phase I for cancer | [134, 137, 235–237] | ||

| TGI1002 | Pre-clinical with in vivo efficacy | [238] | ||

| CIP2A inhibitor | Celastrol | Pre-clinical with in vivo efficacy | [239–241] | |

| TD-19 | Pre-clinical with in vivo efficacy | [242] | ||

| TD-52 | Pre-clinical with in vivo efficacy | [243, 244] | ||

| Protease/CIP2A inhibitor | Bortezomib | Velcade FDA approved for multiple myeloma, multiple phase I/II/III/IV | [243, 245] | |

| PP2A | SMAPs | Pre-clinical with in vivo efficacy | [111, 139, 140] | |

| PIN1 inhibition | PIN1 | Juglone | Pre-clinical with in vivo efficacy | [155, 157–159, 246] |

| PiB | Pre-clinical with in vivo efficacy | [149, 161, 247, 248] | ||

| KPT-6566 | Pre-clinical with in vivo efficacy | [160] | ||

| RA | ATRA | Approved for PML; phase I/II/III/IV | [153, 162, 249] | |

| Ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis | SENP1 | Momordin Ιc | Pre-clinical with in vivo efficacy | [250] |

| Triptolide | Pre-clinical with in vivo efficacy | [251] | ||

| Aurora-A | MLN8237 | Multiple phase I/II | [185, 186, 252] | |

| USP7 | P22077 | Pre-clinical with in vivo efficacy | [180] |

ATRA all-trans retinoic acid, CIP2A cancerous inhibitor of Protein Phosphatase 2A, FDA US Food and Drug Administration, MAX MYC-associated protein X, PiB diethyl-1,3,6,8-tetrahydro-1,3,6,8-tetraoxobenzo[lmn]3, 8 phenanthroline-2,7-diacetate, PML promyelocytic leukemia, PP2A Protein Phosphatase 2A, PIN1 Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase NIMA-interacting 1, SENP1 SUMO Specific Peptidase 1, RA retinoic acid, SET inhibitor-2 of protein phosphatase-2A, SMAPs small-molecule activators of Protein Phosphatase 2A, USP7 Ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase 7

Inhibition of Transcription

Since MYC lacks a defined targetable structure, the epigenetic silencing of the MYC gene provides an interesting strategy to reduce MYC expression and activity. The challenge with this strategy is identification of compounds that preferentially target the MYC gene. Inhibitors of histone deacetylases, histone methyltransferases, histone demethylases, DNA methyltransferases, and bromodomain and extra-terminal motif (BET) bromodomains have all shown some efficacy against MYC, with BET inhibitors being the most well-studied [63]. The BET family member BRD4 recruits positive transcription elongation factor b (P-TEFb) to promoters and enhancers, releasing RNA polymerase II and initiating transcriptional elongation [64]. JQ1, a BET inhibitor, has been shown to inhibit BRD4 binding at acetylated histones within the MYC promoter and enhancers, decreasing expression of c-, L-, and N-MYC [65–67]. JQ1 treatment reduces tumor cell survival and has anti-tumor effects in vitro and in vivo in multiple models [68–73]. There are 15 different BET inhibitors being assessed in the clinic; however, clinical responses have been limited, often result in relapse, and are inconsistent with their effects on MYC expression [74, 75]. These results suggest that as a single agent, BET inhibition may not result in durable responses. In support of this, the majority of OTX015/MK-8628 phase I and II clinical trials resulted in disease progression and termination of the trial. Kurimchak et al. [70] have demonstrated that treatment with JQ1 can induce large-scale reprogramming of signaling pathways leading to resistance. However, these resistant cells were highly sensitive to kinase inhibitors, suggesting efficacy in drug combination [70]. Similarly, a new BET inhibitor now in clinical trials, BI 894999, reduces tumor growth in vivo and synergistically induces cell death when combined with CDK9 inhibitors, supporting the use of these epigenetic inhibitors in combination strategies [76]. Indeed, new dual-function compounds are being explored. The dual-activity phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3 K)–BRD4 inhibitor SF2523 reduced the in vivo growth of MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma and pancreatic xenografts and decreased distant metastasis [77]. Further, SF2523 shows reduced toxicities compared to the individual combination of the PI3 K inhibitor BKM120 and the BRD4 inhibitor JQ1 [77]. Similarly, the dual PI3 K–histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor CUDC-907 reduces MYC gene transcription and MYC protein stability, as well as in vivo tumor growth of lymphoma xenografts [78]. While these inhibitors are not necessarily specific to MYC, the potent effects of dual function compounds on MYC expression and phenotypes supports further exploration of this therapeutic strategy for MYC-dependent tumors.

An alternative approach to inhibit the transcription of MYC takes advantage of complex DNA structures called G-quadruplexes. These secondary structures occur when hydrogen bonding connects a run of four guanines in a planar quartet. The assembly of two or more of these quartets makes up a G-quadruplex structure, which generally resides upstream of the transcriptional start site and silences gene expression. In contrast to BRD4 inhibitors, which indirectly inhibit MYC transcription, small molecules designed to bind and stabilize the G-quadruplexes associated with individual genes provides a unique way to target potentially undruggable oncogenes [79–81]. Studies have shown that small molecules, such as GQC-05, Cz1, IZCZ-3, and DC-34, are capable of binding and stabilizing G-quadruplexes within the nuclease hypersensitive element (NHE) III region of the MYC promoter, resulting in the suppression of MYC messenger RNA (mRNA) and protein and an induction of cytotoxicity [82–87]. Similarly, a study by Bouvard et al. [88] demonstrates that the small molecule stauprimide inhibits the transcription factor NME2 from being recruited to the NHE III region, stabilizing the MYC G-quadruplex, and selectively reducing MYC transcriptional gene programs. Despite having clear MYC-dependent phenotypes, the off-target effects of these various compounds are still being interrogated. In addition to these therapeutic strategies, advances have been made for the in vivo identification and tracking of DNA structures using small-molecule fluorescent probes [89]. This technique would allow for the screening of drugs that affect G-quadruplex structures in cancer and help to identify compounds that lead to the stabilization of these structures. While targeting of G-quadruplexes has emerged as a promising MYC therapeutic strategy, i-motifs, which form on the opposite strand of G-quadruplexes, are mutually exclusive with G-quadruplexes and can promote MYC transcription [90]. The stabilization of i-motifs may drive an acute increase in MYC expression leading to apoptosis; however, we need a more indepth knowledge of the dynamic relationship between these two DNA structures in order to effectively target them in cancer cells [79, 91].

Dimer Disruptors

There are an extensive number of pathways that upregulate MYC expression, increasing the probability that cancer cells will be able to circumvent therapeutics targeting upstream regulation of MYC [9]. Alternatively, compounds that directly bind and inactivate MYC’s downstream function may have better efficacy and reduced acquired resistance. While each MYC domain significantly contributes to MYC function and stability, the bHLHZ domain represents a logical therapeutic target, as it is required for dimerization of MYC to its binding partner MAX and subsequent DNA binding at E-box sequences. Some of the first MYC/MAX dimer disruptors, including 10058-F4 and 10074-G5, were characterized from chemical library screens using systems such as yeast two-hybrid or fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) [92–94]. However, many of these compounds display low potency, with half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values ranging from 20 to 40 μM and potentially off-target effects [95]. Research efforts have focused on chemically improving these base compounds as well as identifying new compounds. Recently, a chemical screen using bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) was performed and the MYC:MAX Inhibitor MYCMI-6 was shown to bind directly within the bHLHZ domain and disrupt MYC/MAX dimerization at a low micromolar range (Dissociation constant [KD] ~ 1.5–2 μM) [96]. In a panel of 60 cancer cell lines, almost ~ 75% of lines expressing ‘high’ levels of MYC mRNA and/or protein showed sensitivity to MYCMI-6. Importantly, in vivo treatment of the MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma cell line SK-N-DZ with MYCMI-6 significantly induced cell death and reduced proliferation. However, MYCMI-6 does not lead to MYC protein degradation, and, therefore, the MAX-independent functions of MYC will need to be well-understood in this therapeutic setting [97]. Alternatively, Struntz et al. [98] demonstrate that stabilization of MAX:MAX homodimers, using the small molecule KI-MS2-008, leads to MYC degradation and attenuation of MYC transcriptional gene programs both in vitro and in vivo. KI-MS2-008 not only reduces MYC expression and function, but also takes advantage of transcriptionally inert MAX:MAX DNA binding. However, this strategy would impact the binding of other MYC network proteins to E-box sites, and, therefore, further investigation is needed [8]. Together, these results show great promise for compounds that disrupt the transcriptional activity of MYC and indicate that high MYC levels may represent a biomarker for clinical response to MYC/MAX dimer disruptors.

Alternatively, studies utilizing peptides against MYC have emerged as novel strategies that disrupt MYC/MAX heterodimers in an effort to reduce MYC DNA-binding potential and transcriptional activation [59, 99]. Although peptides have historically been challenging to administer to patients due to their short half-life and low bioavailability, modifications that address these issues have increased their clinical applicability. For instance, fusion of a MYC H1-derived peptide to an elastin-like polypeptide allowed the peptide to cross the cell membrane in vivo and disrupt MYC/MAX dimers in a glioma model [100]. Similarly, Wang et al. [101] demonstrated that the OmoMYC peptide was unable to penetrate cells; however, the addition of an N-terminal functional penetrating Phylomer peptide allowed OmoMYC to enter cells and reduce tumor growth in vivo. More recently, Beaulieu et al. [102] reported in vivo pre-clinical efficacy using a purified OmoMYC mini-protein, which has intrinsic cell penetrating properties and is capable of disrupting MYC-dependent transcription. Together, these studies represent exciting advances towards the clinical application of MYC-targeted peptides.

Inhibition of MYC Post-Translational Regulation

Given that MYC expression and activity are dynamically regulated by a variety of protein modifications, therapeutic targeting of these post-translational mechanisms provides an innovative, albeit indirect, way to reduce MYC function in cancer. These mechanisms include, but are not limited to (1) kinases that phosphorylate S62-MYC; (2) phosphatases that dephosphorylate S62-MYC; (3) the PIN1 proline isomerase; and (4) enzymes that affect MYC ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis.

Serine 62 Phosphorylation and Dephosphorylation

Kinase inhibitors that affect the active pS62-MYC state include ERK, CDK2, and CDK9 inhibitors [103–109]. Unfortunately, cancer cells are quite adept at rewiring signaling pathways in response to targeted therapies in order to keep MYC and other signaling substrates active [110–112]. An alternative approach to decrease pS62-MYC is through the activation of PP2A, a serine/threonine phosphatase that targets pS62 [113]. PP2A is a heterotrimeric complex composed of a catalytic subunit (PP2A-C), a structural subunit (PP2A-A), and one of 26 different regulatory B subunits, the latter of which is responsible for fully activating the complex and dictating substrate specificity [114–116]. During oncogenesis, cancer cells usually acquire mechanisms to suppress PP2A function [117]. The global suppression of PP2A function has been shown to contribute to cancer cell proliferation, transformation, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, and resistance to targeted therapies, placing PP2A as a central regulator of oncogenic signaling [111, 118–120]. In a short hairpin RNA (shRNA) knockdown screen, decreased expression of the PP2A-B subunit PPP2R5A (B56α) increased anchorage-independent growth in soft agar, implicating this subunit in the regulation of cellular transformation [121]. We found that B56α is the only B subunit able to directly dephosphorylate pS62 MYC and that the loss of B56α leads to increased MYC expression [40]. The activation of PP2A has, therefore, emerged as an attractive therapeutic strategy to target pS62-MYC to decrease MYC activity and protein stability. Currently, there are several compounds, both indirect and direct, that lead to the activation of PP2A and have tumor-suppressor activities.

Indirect Protein Phosphatase 2A (PP2A) Activation

Consistent with the tumor suppressor role of PP2A, the PP2A inhibitors, inhibitor-2 of protein phosphatase-2A (SET) and cancerous inhibitor of PP2A (CIP2A), are overexpressed in a variety of cancers [122–126]. These proteins function to prevent PP2A-B subunits from binding the PP2A A-C core complex, decreasing global PP2A activity and contributing to therapeutic resistance [127, 128]. Interestingly, while CIP2A can broadly inhibit PP2A, it has been shown to preferentially inhibit MYC-associated PP2A in order to increase MYC stability and function [128, 129] Additionally, CIP2A is stabilized when bound to the PP2A B56α subunit, highlighting the importance of this protein to MYC activity [130]. Unfortunately, the therapeutic targeting of CIP2A remains an important and understudied area of research, as there are few therapeutic compounds shown to inhibit CIP2A activity [117]. Currently, bortezomib, a proteasome inhibitor with CIP2A-inhibiting activities, is US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved for multiple myeloma and mantle cell lymphoma and is being assessed in other cancers in phase I, II, and III clinical trials. Similar to CIP2A, SET contributes to cancer cell survival and tumor progression. Knockdown of SET reduces MYC phosphorylation and expression levels in breast and pancreatic cancer cells, and leads to decreased cell survival, supporting the use of SET inhibitors as important therapeutic strategy [47, 49]. OP449 is an oligopeptide that binds to SET and sequesters it from the PP2A complex, indirectly activating PP2A [131]. Similar to SET knockdown, OP449 treatment led to decreased pS62-MYC and reduced in vivo tumor growth in pancreatic and breast cancer cells [47, 49]. In CML, elevated levels of ABL lead to increased SET expression and PP2A inhibition [132]. Studies have shown that OP449 induces a cytotoxic response in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and CML cells, including patients that are resistant to ABL1 kinase inhibitors [133]. FTY720, a sphingosine analog, has also been shown to have PP2A-activating properties [134, 135]. However, FTY720 functions primarily through immunosuppression by internalizing and activating the sphingosine 1 phosphate receptor (S1PR) [136]. FTY720 analogs, such as SH-RF-177, induce cell death in part through PP2A activation without the activation of S1PR, increasing the clinical significance of these compounds [137].

Direct PP2A Activation

More recently, small-molecule activators of PP2A (SMAPs) have emerged as novel, first-in-class therapeutic agents that directly activate PP2A. These compounds were generated based on the established functional groups of tricyclic antipsychotics, which have been shown to have PP2A-activating properties at high concentrations [138]. Using binding assays and photoaffinity labeling, Sangodkar et al. [139] demonstrated that SMAPs bind directly to the PP2A-Aα subunit, causing a conformational change that alleviates negative inhibition and leads to PP2A activation. Treatment with SMAPs reduces tumor growth and proliferation in pancreatic, lung, and castration-resistant prostate cancer, in vivo and in vitro [111, 139, 140]. These results are associated with attenuated oncogenic signaling, with significant decreases in active ERK, SRC, CDK, and MYC. Recently, Kauko et al. [111] demonstrated that knockdown of PP2A contributes to kinase inhibitor resistance, in part due to the induction of high MYC levels. Consistent with these studies, we recently demonstrated that select kinase inhibitors can function synergistically with SMAPs in breast and pancreatic cancer cells [140]. Specifically, the combination of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors and SMAPs synergistically reduced MYC levels beyond the capabilities of either single agent and potently induced cell death. This combination was also associated with increased suppression of AKT signaling, a common resistance mechanism to mTOR inhibitors. Similar to the inhibition of MYC using OmoMYC, SMAPs show little to no toxicity. There are studies, however, that suggest not all PP2A-B subunits function as tumor suppressors. Specifically, a study by Zhang et al. [141] demonstrates that the PP2A-B55α subunit is able to bind MYC with the help of the transcription factor EYA3 and dephosphorylate pT58, leading to increased stability of MYC. Despite the complex roles of PP2A-B subunits in disease states, the aggregate activation of PP2A by SMAPs appears to be detrimental to cancer cells and indicates a unique susceptibility of cancer cells to PP2A activation.

PIN1 Inhibition

PIN1 is a prolyl isomerase that causes a cis–trans or trans–cis conformational change at proline resides that follow phosphorylated serine/threonine sites (pS/T-P sites) [142]. PIN1 isomerization has significant effects on the localization, stability, and activation of target proteins that regulate a variety of cellular processes including proliferation, survival, and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition [143]. Similar to MYC, PIN1 is tightly regulated in normal cells, but is aberrantly upregulated in a variety of cancers, including prostate, breast, lung, ovary and cervical tumors, and melanoma [144], and is associated with poor patient outcomes [145, 146]. Further, PIN1 cooperates with aberrant expression of HER2 and RAS to drive tumorigenesis, placing PIN1 as a central mediator of common oncogenic signals and an attractive therapeutic target [147, 148].

We have demonstrated that PIN1 dynamically regulates MYC activity, with isomerization influencing both MYC activation and degradation. In normal cells, PIN1 helps to balance the activation of MYC with its degradation at select target genes; however, in oncogenic states, where MYC turnover is commonly suppressed through multiple mechanisms and PIN1 expression is high, the predominant effect of PIN1 is to promote MYC activation and regulation of genes involved in tumorigenesis [149]. Consistent with these results, mice with genetic loss of Pin1 (PIN1 knockout [KO] mice) are developmentally normal aside from male sterility, but display increased resistance to tumorigenesis, suggesting that PIN1 predominantly functions as a tumor promoter in this context [150]. Helander et al. [19] demonstrate that PIN1 is capable of binding the MB0 domain of MYC in a potentially priming event to transcriptional activation. Upon S62 MYC phosphorylation, this interaction is stabilized, increasing the association of PIN1 with the MB1 domain where it can promote the isomerization of P63, increasing MYC transcriptional and transforming activity [19]. Interestingly, Su et al. [151] recently demonstrated that serum stimulation localizes pS62-MYC to the nuclear pore basket in a PIN1-dependent manner, where it binds to target genes that regulate proliferation and migration. These studies suggest that the subcellular localization of MYC may be an important regulatory mechanism of MYC transcriptional activity and target gene selection. In addition to direct MYC regulation, PIN1 also influences the activity of proteins that alter MYC’s post-translational modification state, including ERK, CDK, GSK3, and the deSUMOylase SENP1 [152]. Consistent with these results, overexpression of PIN1 increases the transforming potential of MYC, suggesting that PIN1 functions predominantly as a tumor promoter in cancer cells and that therapeutic targeting of PIN1 may be a viable approach to reduce MYC activity [149].

Inhibition of PIN1 prolyl isomerase activity with therapeutic compounds, such as juglone or PiB (diethyl-1,3,6,8-tetrahydro-1,3,6,8-tetraoxobenzo[lmn]3, 8 phenanthroline-2,7-diacetate), have shown efficacy in a variety of tumors [153–160]. However, both of these compounds are able to reduce proliferation in a Pin1 null mouse, indicating that PIN1 is not their only target [158, 161]. Several screens have been performed to try and identify selective inhibitors to PIN1; however, the majority of these studies have led to false positive or non-selective compounds [154]. Wei et al. [162] identified all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) as a novel PIN1 inhibitor using a fluorescence polarization-based high-throughput screening to identify compounds that bind to the active form of PIN1. Importantly, treatment with ATRA significantly reduces in vivo growth of triple-negative breast cancer xenografts and leads to the degradation of PIN1 protein [162]. Similar results were seen in hepatocellular carcinoma xenografts using a slow-release, poly L-lactic acid microparticle containing ATRA [153]. Recently, a small molecule, KPT-6566, has been shown to both covalently bind PIN1’s catalytic site and target PIN1 for degradation, while simultaneously releasing a quinone-mimicking drug that induces DNA damage and cell death [160]. Treatment with KPT-6566 results in cytotoxicity specifically in a panel of cancer cell lines, as compared to normal cells. These results, together with the PIN1 KO mouse results, suggest that normal cells can tolerate the loss of PIN1 while cancer cells rely on PIN1 for specific oncogenic functions important for their survival, particularly under stressed conditions as occurs in vivo. Importantly, treatment of Pin1 null Mouse Embryonic Fibroblast (MEFs) with KPT-6566 had no effect on cell proliferation, indicating that this compound may have a higher specificity for PIN1.

Targeting MYC Stability

The primary approaches to alter MYC stability center on increasing MYC ubiquitin-mediated degradation. MYC family proteins are ubiquitinated by a variety of E3 ubiquitin ligases (E3s), most of which stimulate MYC degradation [15, 163–165]. Importantly, in cancer, mutations or loss of MYC-directed E3s, such as FBW7, frequently occur, contributing to MYC stability [166]. Conversely, E3 s such as SKP2 and HUWE1 are often overexpressed in cancer and have been shown to positively affect MYC activity, presenting potential targets for indirect MYC inhibition [167–169]. For example, Peter et al. [170] demonstrated that inhibition of HUWE1 with either shRNA or small-molecule inhibitors leads to decreased cancer cell viability and suppression of MYC transcriptional activity. However, these findings may be context dependent as other groups have found that HUWE1 has a tumor suppressor function [171, 172]. Therefore, a more indepth understanding of the mechanisms that regulate MYC ubiquitination and turnover are necessary in order to capitalize on therapies that target these factors. An alternative strategy to enhance the activity of E3s that target MYC for degradation is to target MYC deubiquinating enzymes (DUBs). DUBs that deubiquitinate and stabilize MYC family proteins include USP7, USP13, USP22, USP28, USP36, and USP37 [173–179]. Inhibition of these DUBs has been reported to attenuate MYC-dependent gene transcription and increase MYC turnover, with inhibition of USP36 resulting in a dramatic decrease in c-MYC expression and induction of cytotoxicity [175]. Similarly, USP7 has been shown to bind and stabilize N-MYC and inhibition of this DUB decreases N-MYC driven tumorigenesis in vivo [180]. Another strategy to affect MYC ubiquitination involves modulation of the small ubiquitin-related modifier (SUMO), where we have discovered that inhibition of the deSUMOylation enzyme SENP1, which is overexpressed in human breast cancer cells and increases MYC stability and transactivation activity, stimulated MYC ubiquitination and increased MYC degradation, providing a new strategy for MYC protein degradation [181]. Finally, the Aurora-A kinase inhibitors MLN8054 and MLN8237 have been shown to affect both c-MYC and N-MYC ubiquitin-mediated degradation independent of their kinase activity [182–188]. Recently, Li et al. [184] demonstrated that elevated MYC expression correlated with MLN8237 response, both in vitro and in vivo, in thyroid cancer. These studies support the role of Aurora inhibitors as potential MYC-destabilizing therapeutics and suggest that MYC expression may be used as a biomarker for patient response. However, despite promising data, clinical trials with MLN8237 have raised concerns about the safety profile of this compound, with a number of trials resulting in significant toxicities and disease progression [189].

Perspectives

Biomarkers indicative of the mode of MYC deregulation would be extremely informative in directing strategies to target MYC. For example, for tumors with MYC amplification or high MYC gene transcription, inhibitors of MYC transcription such as BET inhibitors, or G-quadruplex stabilizers may show great promise. Likewise, inhibitors of MYC:MAX DNA binding or dimerization could also be quite efficacious in these settings. For tumors where MYC is post-translationally deregulated, an event that most likely occurs in the majority of human tumors, targeting MYC:MAX DNA binding or dimerization could be effective, but other strategies may also be promising, such as targeting enzymes that control active MYC modifications such as S62-MYC phosphorylation or PIN1-mediated isomerization. Likewise, for tumors where the MYC half-life is extended, determined by discordant MYC protein versus mRNA, inhibition of DUBs or SENP1 may be beneficial. The expression of these MYC-modifying enzymes within tumors could present important biomarkers to direct therapeutic strategies. It is also important to consider that post-translational modifications impart dynamic protein control, and a mechanistic understanding of these dynamics should be considered in targeting strategies. For example, the balance between E3 ubiqutin ligases and deubiquitinating enzymes or PIN1 regulation of MYC, which affects both the temporal and spatial activity of MYC [151]. So far, it appears that cancer cells are particularly vulnerable to deregulation of these precise post-translational control mechanisms, which may favor targeting these modifier enzymes, but also could impact dosing or combination strategies. In addition to determining the mechanism by which MYC is aberrantly activated, careful consideration should be made when selecting compounds that indirectly inhibit MYC activity, as many of these agents target factors other than MYC; although, depending on the outcome and target, these post-translational modifier enzymes often target other oncogenic proteins, potentially increasing their efficacy as targeted anti-cancer agents.

Conclusion

Studies over the last several decades indicate that multiple methods of MYC deregulation in cancer exist and not all MYC deregulation is the same, stressing the importance of biomarkers that distinguish these mechanisms, as well as development of diverse therapeutic agents that target unique aspects of MYC oncogenicity.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Funding

Rosalie C. Sears is supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) R01 CA196228, CA186241, and U54 CA209988; and philanthropic support from the Brenden and Colson Family Foundations.

Conflict of interest

Rosalie C. Sears is a partial owner in RAPPTA Therapeutics, Inc., which is working to develop small-molecule activators of Protein Phosphatase 2A. Rosalie C. Sears does not receive funding from this relationship and the company is not public and therefore does not own publicly traded stock. Brittany L. Allen-Petersen declares she has no conflicts of interest that might be relevant to the contents of this review.

References

- 1.Kantarjian H, et al. Improved survival in chronic myeloid leukemia since the introduction of imatinib therapy: a single-institution historical experience. Blood. 2012;119(9):1981–1987. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-08-358135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mendes D, et al. The benefit of HER2-targeted therapies on overall survival of patients with metastatic HER2-positive breast cancer–a systematic review. Breast Cancer Res. 2015;17:140. doi: 10.1186/s13058-015-0648-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bailey MH, et al. Comprehensive characterization of cancer driver genes and mutations. Cell. 2018;173(2):371–385.e318. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.02.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vogelstein B, et al. Cancer genome landscapes. Science. 2013;339(6127):1546–1558. doi: 10.1126/science.1235122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kandoth C, et al. Mutational landscape and significance across 12 major cancer types. Nature. 2013;502(7471):333–339. doi: 10.1038/nature12634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Korc M. Beyond Kras: MYC rules in pancreatic cancer. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;6(2):223–224. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2018.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schaub FX, et al. Pan-cancer alterations of the MYC oncogene and its proximal network across the cancer genome atlas. Cell Syst. 2018;6(3):282–300.e282. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2018.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Conacci-Sorrell M, McFerrin L, Eisenman RN. An overview of MYC and its interactome. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2014;4(1):a014357. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a014357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dang CV. MYC on the path to cancer. Cell. 2012;149(1):22–35. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eilers M, Eisenman RN. Myc’s broad reach. Genes Dev. 2008;22(20):2755–2766. doi: 10.1101/gad.1712408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meyer N, Penn LZ. Reflecting on 25 years with MYC. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8(12):976–990. doi: 10.1038/nrc2231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sodir NM, et al. Endogenous Myc maintains the tumor microenvironment. Genes Dev. 2011;25(9):907–916. doi: 10.1101/gad.2038411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fernandez PC, et al. Genomic targets of the human c-Myc protein. Genes Dev. 2003;17(9):1115–1129. doi: 10.1101/gad.1067003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bisso A, Sabo A, Amati B. MYC in germinal center-derived lymphomas: mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. Immunol Rev. 2019;288(1):178–197. doi: 10.1111/imr.12734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farrell AS, Sears RC. MYC degradation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2014;4(3):a014365. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a014365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hann SR, Eisenman RN. Proteins encoded by the human c-myc oncogene: differential expression in neoplastic cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1984;4(11):2486–2497. doi: 10.1128/mcb.4.11.2486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blackwood EM, Eisenman RN. Max: a helix-loop-helix zipper protein that forms a sequence-specific DNA-binding complex with Myc. Science. 1991;251(4998):1211–1217. doi: 10.1126/science.2006410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blackwood EM, Luscher B, Kretzner L, Eisenman RN. The Myc: Max protein complex and cell growth regulation. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1991;56:109–117. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1991.056.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Helander S, et al. Pre-anchoring of Pin1 to unphosphorylated c-Myc in a fuzzy complex regulates c-Myc activity. Structure. 2015;23(12):2267–2279. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2015.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kato GJ, Barrett J, Villa-Garcia M, Dang CV. An amino-terminal c-myc domain required for neoplastic transformation activates transcription. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10(11):5914–5920. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.11.5914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prendergast GC, Ziff EB. Methylation-sensitive sequence-specific DNA binding by the c-Myc basic region. Science. 1991;251(4990):186–189. doi: 10.1126/science.1987636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cowling VH, Cole MD. Mechanism of transcriptional activation by the Myc oncoproteins. Semin Cancer Biol. 2006;16(4):242–252. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Flinn EM, Busch CM, Wright AP. myc boxes, which are conserved in myc family proteins, are signals for protein degradation via the proteasome. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18(10):5961–5969. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.10.5961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gargano B, Amente S, Majello B, Lania L. P-TEFb is a crucial co-factor for Myc transactivation. Cell Cycle. 2007;6(16):2031–2037. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.16.4554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rahl PB, et al. c-Myc regulates transcriptional pause release. Cell. 2010;141(3):432–445. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yada M, et al. Phosphorylation-dependent degradation of c-Myc is mediated by the F-box protein Fbw7. EMBO J. 2004;3(10):2116–2125. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kurland JF, Tansey WP. Myc-mediated transcriptional repression by recruitment of histone deacetylase. Cancer Res. 2008;68(10):3624–3629. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Herbst A, et al. A conserved element in Myc that negatively regulates its proapoptotic activity. EMBO Rep. 2005;6(2):177–183. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gregory MA, Hann SR. c-Myc proteolysis by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway: stabilization of c-Myc in Burkitt’s lymphoma cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20(7):2423–2435. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.7.2423-2435.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cowling VH, Chandriani S, Whitfield ML, Cole MD. A conserved Myc protein domain, MBIV, regulates DNA binding, apoptosis, transformation, and G2 arrest. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26(11):4226–4239. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01959-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grandori C, Cowley SM, James LP, Eisenman RN. The Myc/Max/Mad network and the transcriptional control of cell behavior. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2000;16:653–699. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.16.1.653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lutterbach B, Hann SR. Hierarchical phosphorylation at N-terminal transformation-sensitive sites in c-Myc protein is regulated by mitogens and in mitosis. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14(8):5510–5522. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.8.5510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sears R, et al. Multiple Ras-dependent phosphorylation pathways regulate Myc protein stability. Genes Dev. 2000;14(19):2501–2514. doi: 10.1101/gad.836800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sears RC. The life cycle of C-myc: from synthesis to degradation. Cell Cycle. 2004;3(9):1133–1137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hydbring P, et al. Phosphorylation by Cdk2 is required for Myc to repress Ras-induced senescence in cotransformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(1):58–63. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900121106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pulverer BJ, et al. Site-specific modulation of c-Myc cotransformation by residues phosphorylated in vivo. Oncogene. 1994;9(1):59–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yeh E, et al. A signalling pathway controlling c-Myc degradation that impacts oncogenic transformation of human cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6(4):308–318. doi: 10.1038/ncb1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Welcker M, et al. The Fbw7 tumor suppressor regulates glycogen synthase kinase 3 phosphorylation-dependent c-Myc protein degradation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(24):9085–9090. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402770101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arnold HK, et al. The Axin1 scaffold protein promotes formation of a degradation complex for c-Myc. EMBO J. 2009;28(5):500–512. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Arnold HK, Sears RC. Protein phosphatase 2A regulatory subunit B56alpha associates with c-myc and negatively regulates c-myc accumulation. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26(7):2832–2844. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.7.2832-2844.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sabo A, Amati B. Genome recognition by MYC. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2014;4(2):a014191. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a014191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sabo A, et al. Selective transcriptional regulation by Myc in cellular growth control and lymphomagenesis. Nature. 2014;511(7510):488–492. doi: 10.1038/nature13537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morton JP, Sansom OJ. MYC-y mice: from tumour initiation to therapeutic targeting of endogenous MYC. Mol Oncol. 2013;7(2):248–258. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2013.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kalkat M, et al. MYC deregulation in primary human cancers. Genes (Basel) 2017;8(6):E151. doi: 10.3390/genes8060151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Malempati S, et al. Aberrant stabilization of c-Myc protein in some lymphoblastic leukemias. Leukemia. 2006;20(9):1572–1581. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang X, et al. Mechanistic insight into Myc stabilization in breast cancer involving aberrant Axin1 expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(8):2790–2795. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100764108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Farrell AS, et al. Targeting inhibitors of the tumor suppressor PP2A for the treatment of pancreatic cancer. Mol Cancer Res. 2014;12(6):924–939. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-13-0542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hemann MT, et al. Evasion of the p53 tumour surveillance network by tumour-derived MYC mutants. Nature. 2005;436(7052):807–811. doi: 10.1038/nature03845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Janghorban M, et al. Targeting c-MYC by antagonizing PP2A inhibitors in breast cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(25):9157–9162. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1317630111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schleger C, Verbeke C, Hildenbrand R, Zentgraf H, Bleyl U. c-MYC activation in primary and metastatic ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreas: incidence, mechanisms, and clinical significance. Mod Pathol. 2002;15(4):462–469. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3880547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang X, et al. Phosphorylation regulates c-Myc’s oncogenic activity in the mammary gland. Cancer Res. 2011;71(3):925–936. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Farrell AS, et al. MYC regulates ductal-neuroendocrine lineage plasticity in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma associated with poor outcome and chemoresistance. Nat Commun. 2017;8(1):1728. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01967-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Walz S, et al. Activation and repression by oncogenic MYC shape tumour-specific gene expression profiles. Nature. 2014;511(7510):483–487. doi: 10.1038/nature13473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Soucek L, et al. Inhibition of Myc family proteins eradicates KRas-driven lung cancer in mice. Genes Dev. 2013;27(5):504–513. doi: 10.1101/gad.205542.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sansom OJ, et al. Myc deletion rescues Apc deficiency in the small intestine. Nature. 2007;446(7136):676–679. doi: 10.1038/nature05674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Annibali D, et al. Myc inhibition is effective against glioma and reveals a role for Myc in proficient mitosis. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4632. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Soucek L, Nasi S, Evan GI. Omomyc expression in skin prevents Myc-induced papillomatosis. Cell Death Differ. 2004;11(9):1038–1045. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li Y, Casey SC, Felsher DW. Inactivation of MYC reverses tumorigenesis. J Intern Med. 2014;276(1):52–60. doi: 10.1111/joim.12237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jung LA, et al. OmoMYC blunts promoter invasion by oncogenic MYC to inhibit gene expression characteristic of MYC-dependent tumors. Oncogene. 2017;36(14):1911–1924. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liu J, et al. Intrinsic disorder in transcription factors. Biochemistry. 2006;45(22):6873–6888. doi: 10.1021/bi0602718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tsafou K, Tiwari PB, Forman-Kay JD, Metallo SJ, Toretsky JA. targeting intrinsically disordered transcription factors: changing the paradigm. J Mol Biol. 2018;430(16):2321–2341. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2018.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gao J, Xu D. Correlation between posttranslational modification and intrinsic disorder in protein. Pac Symp Biocomput. 2012; 94-103. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 63.Poole CJ, van Riggelen J. MYC-master regulator of the cancer epigenome and transcriptome. Genes (Basel) 2017;8(5):E142. doi: 10.3390/genes8050142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yang Z, He N, Zhou Q. Brd4 recruits P-TEFb to chromosomes at late mitosis to promote G1 gene expression and cell cycle progression. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28(3):967–976. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01020-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Delmore JE, et al. BET bromodomain inhibition as a therapeutic strategy to target c-Myc. Cell. 2011;146(6):904–917. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bandopadhayay P, et al. BET bromodomain inhibition of MYC-amplified medulloblastoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20(4):912–925. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-2281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kato F, et al. MYCL is a target of a BET bromodomain inhibitor, JQ1, on growth suppression efficacy in small cell lung cancer cells. Oncotarget. 2016;7(47):77378–77388. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.12671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bhadury J, et al. BET and HDAC inhibitors induce similar genes and biological effects and synergize to kill in Myc-induced murine lymphoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(26):E2721–E2730. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1406722111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.da Motta LL, et al. The BET inhibitor JQ1 selectively impairs tumour response to hypoxia and downregulates CA9 and angiogenesis in triple negative breast cancer. Oncogene. 2017;36(1):122–132. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kurimchak AM, et al. Resistance to BET bromodomain inhibitors is mediated by kinome reprogramming in ovarian cancer. Cell Rep. 2016;16(5):1273–1286. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.06.091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Leal AS, et al. Bromodomain inhibitors, JQ1 and I-BET 762, as potential therapies for pancreatic cancer. Cancer Lett. 2017;394:76–87. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2017.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Qiu H, et al. JQ1 suppresses tumor growth through downregulating LDHA in ovarian cancer. Oncotarget. 2015;6(9):6915–6930. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wang J, et al. The BET bromodomain inhibitor JQ1 radiosensitizes non-small cell lung cancer cells by upregulating p21. Cancer Lett. 2017;391:141–151. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2017.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Doroshow DB, Eder JP, LoRusso PM. BET inhibitors: a novel epigenetic approach. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(8):1776–1787. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kharenko OA, Hansen HC. Novel approaches to targeting BRD4. Drug Discov Today Technol. 2017;24:19–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ddtec.2017.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gerlach D, et al. The novel BET bromodomain inhibitor BI 894999 represses super-enhancer-associated transcription and synergizes with CDK9 inhibition in AML. Oncogene. 2018;37(20):2687–2701. doi: 10.1038/s41388-018-0150-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Andrews FH, et al. Dual-activity PI3 K-BRD4 inhibitor for the orthogonal inhibition of MYC to block tumor growth and metastasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114(7):E1072–E1080. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1613091114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sun K, et al. Dual HDAC and PI3 K Inhibitor CUDC-907 downregulates MYC and suppresses growth of MYC-dependent cancers. Mol Cancer Ther. 2017;16(2):285–299. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-16-0390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hurley LH, Von Hoff DD, Siddiqui-Jain A, Yang D. Drug targeting of the c-MYC promoter to repress gene expression via a G-quadruplex silencer element. Semin Oncol. 2006;33(4):498–512. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2006.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Palumbo SL, Ebbinghaus SW, Hurley LH. Formation of a unique end-to-end stacked pair of G-quadruplexes in the hTERT core promoter with implications for inhibition of telomerase by G-quadruplex-interactive ligands. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131(31):10878–10891. doi: 10.1021/ja902281d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Qin Y, Rezler EM, Gokhale V, Sun D, Hurley LH. Characterization of the G-quadruplexes in the duplex nuclease hypersensitive element of the PDGF-A promoter and modulation of PDGF-A promoter activity by TMPyP4. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(22):7698–7713. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Brown RV, Danford FL, Gokhale V, Hurley LH, Brooks TA. Demonstration that drug-targeted down-regulation of MYC in non-Hodgkins lymphoma is directly mediated through the promoter G-quadruplex. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(47):41018–41027. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.274720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Calabrese DR, et al. Chemical and structural studies provide a mechanistic basis for recognition of the MYC G-quadruplex. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):4229. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06315-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Das T, Panda D, Saha P, Dash J. Small molecule driven stabilization of promoter G-quadruplexes and transcriptional regulation of c-MYC. Bioconjug Chem. 2018;29(8):2636–2645. doi: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.8b00338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gonzalez V, Hurley LH. The C-terminus of nucleolin promotes the formation of the c-MYC G-quadruplex and inhibits c-MYC promoter activity. Biochemistry. 2010;49(45):9706–9714. doi: 10.1021/bi100509s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mathad RI, Hatzakis E, Dai J, Yang D. c-MYC promoter G-quadruplex formed at the 5′-end of NHE III1 element: insights into biological relevance and parallel-stranded G-quadruplex stability. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(20):9023–9033. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hu MH, et al. Discovery of a new four-leaf clover-like ligand as a potent c-MYC transcription inhibitor specifically targeting the promoter G-quadruplex. J Med Chem. 2018;61(6):2447–2459. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b01697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bouvard C, et al. Small molecule selectively suppresses MYC transcription in cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114(13):3497–3502. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1702663114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zhang S, et al. Real-time monitoring of DNA G-quadruplexes in living cells with a small-molecule fluorescent probe. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(15):7522–7532. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sutherland C, Cui Y, Mao H, Hurley LH. A mechanosensor mechanism controls the G-quadruplex/i-motif molecular switch in the MYC promoter NHE III1. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138(42):14138–14151. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b09196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Brooks TA, Hurley LH. Targeting MYC Expression through G-Quadruplexes. Genes Cancer. 2010;1(6):641–649. doi: 10.1177/1947601910377493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Yap JL, et al. Pharmacophore identification of c-Myc inhibitor 10074-G5. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2013;23(1):370–374. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Huang MJ, Cheng YC, Liu CR, Lin S, Liu HE. A small-molecule c-Myc inhibitor, 10058-F4, induces cell-cycle arrest, apoptosis, and myeloid differentiation of human acute myeloid leukemia. Exp Hematol. 2006;34(11):1480–1489. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2006.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Berg T, et al. Small-molecule antagonists of Myc/Max dimerization inhibit Myc-induced transformation of chicken embryo fibroblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(6):3830–3835. doi: 10.1073/pnas.062036999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Carabet LA, Rennie PS, Cherkasov A. Therapeutic inhibition of Myc in cancer. Structural bases and computer-aided drug discovery approaches. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;20(1):E120. doi: 10.3390/ijms20010120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Castell A, et al. A selective high affinity MYC-binding compound inhibits MYC:MAX interaction and MYC-dependent tumor cell proliferation. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):10064. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-28107-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Steiger D, Furrer M, Schwinkendorf D, Gallant P. Max-independent functions of Myc in Drosophila melanogaster. Nat Genet. 2008;40(9):1084–1091. doi: 10.1038/ng.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Struntz NB, et al. Stabilization of the Max homodimer with a small molecule attenuates Myc-driven transcription. Cell Chem Biol. 2019;26(5):711–723.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2019.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Soucek L, et al. Omomyc, a potential Myc dominant negative, enhances Myc-induced apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2002;62(12):3507–3510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Bidwell GL, 3rd, et al. Thermally targeted delivery of a c-Myc inhibitory polypeptide inhibits tumor progression and extends survival in a rat glioma model. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e55104. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Wang E, et al. Tumor penetrating peptides inhibiting MYC as a potent targeted therapeutic strategy for triple-negative breast cancers. Oncogene. 2019;38(1):140–150. doi: 10.1038/s41388-018-0421-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Beaulieu ME, et al. Intrinsic cell-penetrating activity propels Omomyc from proof of concept to viable anti-MYC therapy. Sci Transl Med. 2019;11(484):eaar5012. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aar5012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Huang CH, et al. CDK9-mediated transcription elongation is required for MYC addiction in hepatocellular carcinoma. Genes Dev. 2014;28(16):1800–1814. doi: 10.1101/gad.244368.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Bolin S, et al. Combined BET bromodomain and CDK2 inhibition in MYC-driven medulloblastoma. Oncogene. 2018;37(21):2850–2862. doi: 10.1038/s41388-018-0135-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Jiang H, et al. Concurrent HER or PI3 K inhibition potentiates the antitumor effect of the ERK inhibitor ulixertinib in preclinical pancreatic cancer models. Mol Cancer Ther. 2018;17(10):2144–2155. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-17-1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Morris EJ, et al. Discovery of a novel ERK inhibitor with activity in models of acquired resistance to BRAF and MEK inhibitors. Cancer Discov. 2013;3(7):742–750. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Hayes TK, et al. Long-term ERK inhibition in KRAS-mutant pancreatic cancer is associated with MYC degradation and senescence-like growth suppression. Cancer Cell. 2016;29(1):75–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Horiuchi D, et al. MYC pathway activation in triple-negative breast cancer is synthetic lethal with CDK inhibition. J Exp Med. 2012;209(4):679–696. doi: 10.1084/jem.20111512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Garcia-Cuellar MP, et al. Efficacy of cyclin-dependent-kinase 9 inhibitors in a murine model of mixed-lineage leukemia. Leukemia. 2014;28(7):1427–1435. doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Rosell R, et al. Adaptive resistance to targeted therapies in cancer. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2013;2(3):152–159. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2218-6751.2012.12.08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Kauko O, O’Connor CM, Kulesskiy E, et al. PP2A inhibition is a druggable MEK inhibitor resistance mechanism in KRAS-mutant lung cancer cells. Sci Transl Med. 2018;10(450):eaaq1093. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaq1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Risom T, et al. Differentiation-state plasticity is a targetable resistance mechanism in basal-like breast cancer. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):3815. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05729-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Arnold HK, Sears RC. A tumor suppressor role for PP2A-B56alpha through negative regulation of c-Myc and other key oncoproteins. Cancer Metast Rev. 2008;27(2):147–158. doi: 10.1007/s10555-008-9128-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Eichhorn PJ, Creyghton MP, Bernards R. Protein phosphatase 2A regulatory subunits and cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1795(1):1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Kiely M, Kiely PA. PP2A: the wolf in sheep’s clothing? Cancers (Basel) 2015;7(2):648–669. doi: 10.3390/cancers7020648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Sangodkar J, et al. All roads lead to PP2A: exploiting the therapeutic potential of this phosphatase. FEBS J. 2016;283(6):1004–1024. doi: 10.1111/febs.13573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.O’Connor CM, Perl A, Leonard D, Sangodkar J, Narla G. Therapeutic targeting of PP2A. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2018;96:182–193. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2017.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Ruvolo PP. The broken “Off” switch in cancer signaling: PP2A as a regulator of tumorigenesis, drug resistance, and immune surveillance. BBA Clin. 2016;6:87–99. doi: 10.1016/j.bbacli.2016.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Pallas DC, et al. Polyoma small and middle T antigens and SV40 small t antigen form stable complexes with protein phosphatase 2A. Cell. 1990;60(1):167–176. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90726-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Chen W, Arroyo JD, Timmons JC, Possemato R, Hahn WC. Cancer-associated PP2A Aalpha subunits induce functional haploinsufficiency and tumorigenicity. Cancer Res. 2005;65(18):8183–8192. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Sablina AA, Hector M, Colpaert N, Hahn WC. Identification of PP2A complexes and pathways involved in cell transformation. Cancer Res. 2010;70(24):10474–10484. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Cristobal I, et al. Deregulation of SET is Associated with tumor progression and predicts adverse outcome in patients with early-stage colorectal cancer. J Clin Med. 2019;8(3):E346. doi: 10.3390/jcm8030346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Cristobal I, et al. Overexpression of SET is a recurrent event associated with poor outcome and contributes to protein phosphatase 2A inhibition in acute myeloid leukemia. Haematologica. 2012;97(4):543–550. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2011.050542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Westermarck J, Hahn WC. Multiple pathways regulated by the tumor suppressor PP2A in transformation. Trends Mol Med. 2008;14(4):152–160. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Liu CY, et al. Targeting SET to restore PP2A activity disrupts an oncogenic CIP2A-feedforward loop and impairs triple negative breast cancer progression. EBioMedicine. 2019;40:263–275. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2018.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Khanna A, Pimanda JE, Westermarck J. Cancerous inhibitor of protein phosphatase 2A, an emerging human oncoprotein and a potential cancer therapy target. Cancer Res. 2013;73(22):6548–6553. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Li M, Makkinje A, Damuni Z. The myeloid leukemia-associated protein SET is a potent inhibitor of protein phosphatase 2A. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(19):11059–11062. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.19.11059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Junttila MR, et al. CIP2A inhibits PP2A in human malignancies. Cell. 2007;130(1):51–62. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Niemela M, et al. CIP2A signature reveals the MYC dependency of CIP2A-regulated phenotypes and its clinical association with breast cancer subtypes. Oncogene. 2012;31(39):4266–4278. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Wang J, et al. Oncoprotein CIP2A is stabilized via interaction with tumor suppressor PP2A/B56. EMBO Rep. 2017;18(3):437–450. doi: 10.15252/embr.201642788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Neviani P, Perrotti D. SETting OP449 into the PP2A-activating drug family. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20(8):2026–2028. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-0166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Neviani P, et al. The tumor suppressor PP2A is functionally inactivated in blast crisis CML through the inhibitory activity of the BCR/ABL-regulated SET protein. Cancer Cell. 2005;8(5):355–368. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Agarwal A, et al. Antagonism of SET using OP449 enhances the efficacy of tyrosine kinase inhibitors and overcomes drug resistance in myeloid leukemia. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20(8):2092–2103. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-2575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Matsuoka Y, Nagahara Y, Ikekita M, Shinomiya T. A novel immunosuppressive agent FTY720 induced Akt dephosphorylation in leukemia cells. Br J Pharmacol. 2003;138(7):1303–1312. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Cristobal I, et al. Potential anti-tumor effects of FTY720 associated with PP2A activation: a brief review. Curr Med Res Opin. 2016;32(6):1137–1141. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2016.1162774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Stessin AM, et al. FTY720/fingolimod, an oral S1PR modulator, mitigates radiation induced cognitive deficits. Neurosci Lett. 2017;658:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2017.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.McCracken AN, et al. Phosphorylation of a constrained azacyclic FTY720 analog enhances anti-leukemic activity without inducing S1P receptor activation. Leukemia. 2017;31(3):669–677. doi: 10.1038/leu.2016.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Gutierrez A, et al. Phenothiazines induce PP2A-mediated apoptosis in T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(2):644–655. doi: 10.1172/JCI65093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Sangodkar J, et al. Activation of tumor suppressor protein PP2A inhibits KRAS-driven tumor growth. J Clin Invest. 2017;127(6):2081–2090. doi: 10.1172/JCI89548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Allen-Petersen BL, et al. Activation of PP2A and inhibition of mTOR synergistically reduce MYC signaling and decrease tumor growth in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res. 2019;79(1):209–219. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-0717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Zhang L, et al. Eya3 partners with PP2A to induce c-Myc stabilization and tumor progression. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):1047. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03327-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.El Boustani M, et al. A guide to PIN1 function and mutations across cancers. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:1477. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.01477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Zhou XZ, Lu KP. The isomerase PIN1 controls numerous cancer-driving pathways and is a unique drug target. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016;16(7):463–478. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Bao L, et al. Prevalent overexpression of prolyl isomerase Pin1 in human cancers. Am J Pathol. 2004;164(5):1727–1737. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63731-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Leung KW, et al. Pin1 overexpression is associated with poor differentiation and survival in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oncol Rep. 2009;21(4):1097–1104. doi: 10.3892/or_00000329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.He J, et al. Overexpression of Pin1 in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and its correlation with lymph node metastases. Lung Cancer. 2007;56(1):51–58. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2006.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Wulf GM, et al. Pin1 is overexpressed in breast cancer and cooperates with Ras signaling in increasing the transcriptional activity of c-Jun towards cyclin D1. EMBO J. 2001;20(13):3459–3472. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.13.3459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Lam PB, et al. Prolyl isomerase Pin1 is highly expressed in Her2-positive breast cancer and regulates erbB2 protein stability. Mol Cancer. 2008;7:91. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-7-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Farrell AS, et al. Pin1 regulates the dynamics of c-Myc DNA binding to facilitate target gene regulation and oncogenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 2013;33(15):2930–2949. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01455-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Lu Z, Hunter T. Prolyl isomerase Pin1 in cancer. Cell Res. 2014;24(9):1033–1049. doi: 10.1038/cr.2014.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]