Abstract

When and how hippocampal neuronal ensembles first organize to support encoding and consolidation of memory episodes, a critical cognitive function of the brain, are unknown. We recorded electrophysiological activity from large ensembles of hippocampal neurons starting on the first day after eye opening as naïve rats navigated linear environments and slept. We found a gradual age-dependent, navigational experience–independent assembly of preconfigured trajectory-like sequences from persistent, location-depicting ensembles during postnatal week 3. Adult-like compressed binding of adjacent locations into trajectories during navigation and their navigational experience–dependent replay during sleep emerged in concert from spontaneous preconfigured sequences only during early postnatal week 4. Our findings reveal ethologically relevant distinct phases in the development of hippocampal preconfigured and experience-dependent sequential patterns thought to be important for episodic memory formation.

The hippocampus is crucial for relational binding of spatial locations and events into spatial-mental trajectories and memory episodes (1–3). The rapid encoding and consolidation of sequential spatial experiences into memory episodes are achieved by representation of such trajectories within time-compressed hippocampal neuronal sequences during sleep or rest preceding (4) and following (5) novel experiences. The hippocampus undergoes a developmental critical period and functionally matures around postnatal day 24 (P24) (6, 7). However, when and how hippocampal neuronal ensemble patterns of activity across different brain states underlying the encoding and consolidation of episodic-like memory develop, along with their dependence on intrinsic developmental programs and/or prior structured experience, have remained unknown. This is largely due to the difficulty of simultaneously recording electrophysiological activity from sufficient numbers of neurons in freely behaving developing animals (8, 9).

Previous studies of sensory-motor brain areas have mapped how neuronal activity before and after experience (10) relates to the development of synaptic connectivity (11) and plasticity (12). However, the hippocampus does not directly respond to external stimuli of a single sensory modality (13); it integrates multimodal sensory and locomotor information across different brain states during navigation, awake rest, and sleep and expresses such information within compressed temporal neuronal sequences (5, 14, 15). Furthermore, episodic memory, thought to depend on the maturation of the hippocampal network, develops after sensory-motor systems appear sufficiently operational. Finally, structural maturation of the hippocampal formation is controlled by intrinsic signals from the stellate cells of the entorhinal cortex (16). These differences between the hippocampus and the sensory-motor systems further emphasize the need to understand the developmental stages of episodic-like memory function within the hippocampus.

We recorded electrophysiological activity of large ensembles of dorsal CA1 hippocampal neurons (up to 67 neurons) from 19 2- to 3-week-old freely behaving rats during ~30 min of their first ever (de novo) exploration of a 1-m linear track (i.e., the first-time run, which we refer to as Day1Run). We also recorded the preceding and following ~90-min-long sleep sessions (i.e., Pre-Run and Post-Run sleep) and awake rest epochs (awake rest) on the track (Fig. 1A). Fourteen animals reexplored the linear track on the same day (i.e., Day1Run2). On the following day, all animals reexplored the same linear track (Day2Run), and this run session was flanked by sleep sessions (Fig. 1A). Our recordings started from P15 (table S1) and included two of the previously proposed developmental landmarks corresponding to the maturation of individual CA1 place cells (on P17) and of the upstream entorhinal cortical grid cells (on P21) (8, 9, 17). The recordings of de novo run and associated sleep and rest during development were extended until P24, an age when individual hippocampal and entorhinal neuronal activities become adult-like (8, 9, 17). We also recorded the activity of dorsal CA1 hippocampal neurons in three adult rats (age ~90 days) that were undergoing a similar experimental protocol (see materials and methods).

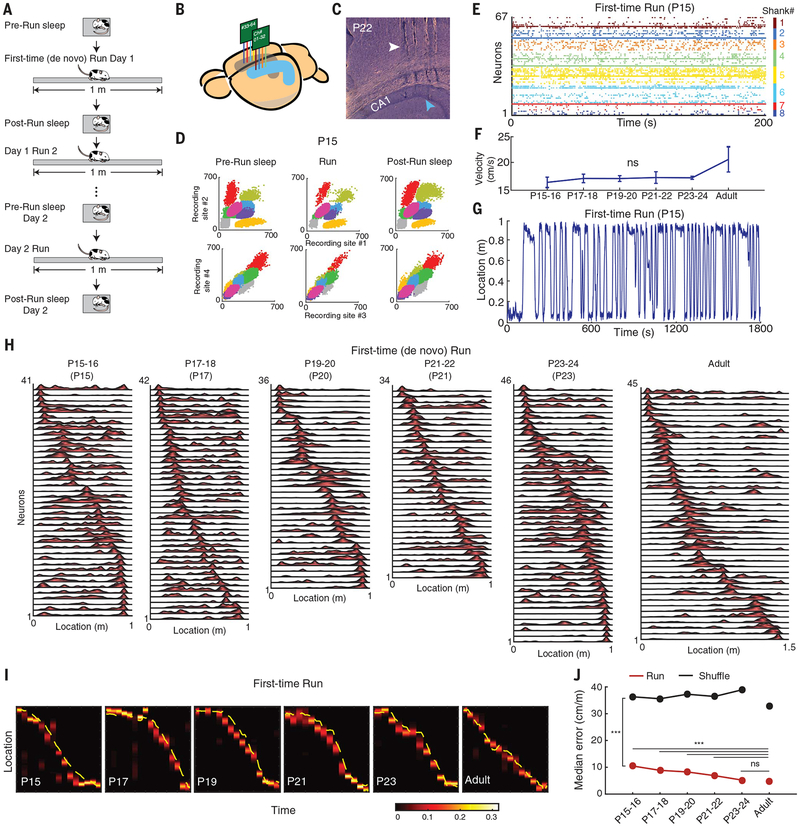

Fig. 1. Early-life development of hippocampal neuronal ensemble spatial representation during first-time navigation.

(A) Schematic of experimental protocol. (B) Illustration of bilateral silicon probe implants in the dorsal hippocampal area CA1. (C) Sagittal brain section depicting tracks of four silicon probe shanks (white arrowhead) recording in CA1 (blue arrowhead) at P22. (D) Color-coded illustration of clusters of eight single cells recorded from one shank in a P15 animal during sleep-run-sleep sessions. (E) Simultaneous recording of 67 CA1 neurons across eight shanks at P15. (F) Similar velocity during first-time (de novo) run across development [P = 0.209; analysis of variance (ANOVA)]. (G) Example of first-time run trajectory at P15. (H) Examples of simultaneously recorded place cell sequences during first-time run across development. (I) Increased accuracy in neuronal ensemble representation of spatial locations during first-time navigation across ages throughout development, based on a memoryless Bayesian decoding algorithm (heatmap). Yellow line: actual animal trajectory. The color map shows the probability of a decoded location. (J) Significance (from P15–P16 onward, run vs. shuffle; P < 10−10, rank sum tests) and age-dependent improvement (P < 10−10, Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA) of neuronal ensemble–decoded locations during first-time navigation across development. Representation becomes adult-like at P23–P24. For post hoc comparisons with adult data, Dunn’s test was used. ***P < 0.001; ns, not significant.

Two movable 32-channel lightweight Neuronexus silicon octatrodes (Fig. 1, B and C) were implanted bilaterally into the hippocampus of experimentally naïve developing rats, yielding a total of 1763 single neurons for recordings on days 1 and 2 (Fig. 1, D and E). The P15 to P24 (P15–P24) animals explored the linear track in full laps and at similar velocities and angular head movement across ages (Fig. 1, F and G, and fig. S1, A to D). Place fields during run were computed for each individual putative pyramidal cell as described previously for adult rats (15). The P15–P24 developing animals were grouped into nonoverlapping age groups of two consecutive days (three to five animals per group), from P15–P16 to P23–P24 (Fig. 1H).

We observed an improvement with age in the metrics of spatial tuning (i.e., spatial information and place field stability within a run session) of individual place cells (Fig. 1H and fig. S2, A and B). We used a memoryless Bayesian decoder to predict the instantaneous location of an animal based on population neuronal spike trains. Despite the age-dependent increase in spatial tuning at the individual neuronal level, the decoding of animal location along its trajectory during a run was accurate as early as P15 (Fig. 1I and fig. S2C). The error in decoding location reduced with development, from ~10% track length at P15–P16 to ~5% at P23–P24 and adulthood. For all ages, the accuracy of neuronal ensembles to predict the current location of the animal was >3 times higher than that computed from shuffled data (Fig. 1J). This indicates that, from the very first exposure to a linear environment, 1 day after eye opening, hippocampal neuronal ensembles can reliably encode discrete locations along an animal’s trajectory based on a firing rate code.

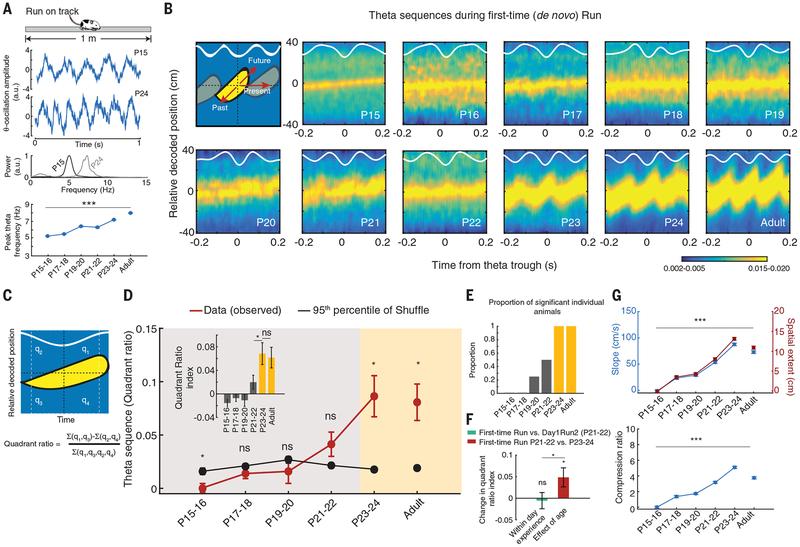

In addition, during a run the adult hippocampal network relationally binds past, current, and future sequential locations into trajectories at an order of magnitude faster than behavior. These compressed sequences are termed theta sequences due to their occurrence within 5- to 8-Hz theta oscillations in the hippocampus (14, 18). Interventional studies suggest a relative dissociation between firing rate–based encoding of discrete locations by neuronal ensembles and binding of sequential locations into theta sequences by an ensemble temporal code (19, 20). The ensemble temporal code is more strongly correlated with behavioral performance (21, 22) and the role of the hippocampus in learning and memory (21–23) than the ensemble rate code. We investigated the developmental time-line of theta sequences during de novo exploration of linear tracks. Theta oscillation was present as early as P15, and its peak frequency increased as a function of age (Fig. 2A and fig. S3A). For theta cycles in the de novo run session, we decoded the trajectory based on ensemble neuronal activity (at velocities >10 cm/s). Theta sequences that bound past, current, and future animal locations within a theta cycle only occurred consistently in the P23–P24 group, and their strength [i.e., quadrant ratio (see materials and methods)] became adult-like for the first time at this age (Fig. 2, B to E, and fig. S3). Prior within-day navigational experience on the same linear track was not sufficient to accelerate the age-dependent increase in strength of theta sequences at P21–P22 (Fig. 2F). At earlier ages (P15 to P20), the hippocampal network represented well the current location of the animal on the track (Fig. 2G and fig. S3B), but the compressed binding of sequential locations within theta cycles could be variably decoded during a run starting only at P21–P22 and became adult-like at P23–P24 (Fig. 2, E and G). These changes were not due to an age-related increase in theta power (fig. S3, G and H). The later development of compressed theta sequences depicting an animal’s trajectory by an ensemble temporal code contrasts with the earlier development of ensemble rate-code–based representation of individual locations.

Fig. 2. Delayed development of compressed theta sequences during first-time navigation on linear tracks.

(A) Age-dependent increase in CA1 theta oscillation frequency across development (P < 10−10, ANOVA). The middle and bottom panels show wide band signals and the normalized power spectra for example P15 and P24 animals during the run. (B) Examples of developmental timeline (P15 to P24, panels 2 to 11) for compressed theta sequences binding past, current, and future locations (cartoon at top left). White curves: session-averaged theta oscillations. Note the absence of compressed theta rhythmic binding of past, current, and future locations at younger ages. (C) Quantification method for compressed theta sequence strength (quadrant ratio) in binding past, current, and future locations. (D) Developmental timeline (P15 to P24) of theta sequence strength. Note the emergence of consistent adult-like theta sequences (>shuffle) at P23–P24 (two directions per animal; n = 5, 3, 4, 4, 3, and 3 animals per age group, from P15–P16 to adult). (Inset) The quadrant ratio index significantly increases with age and becomes adult-like at P23–24. (E) Proportion of animals within age groups with theta sequences above the 95th percentile of their shuffles. (F) Effects of navigational experience on theta sequence strength (quadrant ratio index). Note that within-day experience (green bar; P = 0.75, paired t test, two directions per animal, three animals) does not reveal significant increases in theta sequence strength at P21–P22, while the increase in age, from P21–P22 to P23–P24, reveals increased strength during first-time navigation (red bar; P = 0.04, t test, two directions per animal, n = 4 and 3 animals). The effect of age is significantly higher than that of within-day experience (P = 0.03, t test). (G) Theta sequence slope/spatial extent (top) and compression ratio (bottom) increase with age (P < 10−10, ANOVAs). Data are means ± SEM. ***P < 10−10; *P < 0.05; ns, not significant.

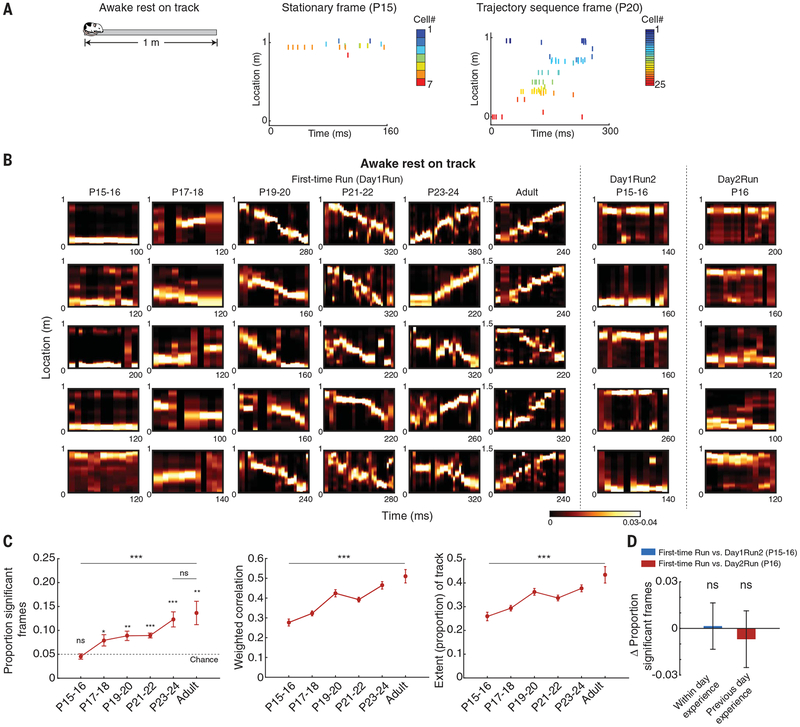

Animals tend to rest between running individual laps on tracks. During these brief awake rest epochs, neuronal ensembles within transient periods of heightened population synchrony (termed frames) replay remembered (24) and preplay future (4) trajectories through linear space in association with 140- to 250-Hz ripple oscillations. We explored the developmental timeline of awake replay as our P15–P24 rats rested between laps during de novo run sessions. We detected frames of activity during awake rest, defined as increases in multineuronal activity (minimum of five neurons) exceeding two standard deviations (SD) above the mean at animal velocities <1 cm/s. We decoded an animal’s virtual location on the track from the ensemble activity during the frames based on the corresponding activity during a run, as reported for adult animals (15, 25). At P15–P16, the decoded activity from ~16% of the awake rest frames persistently depicted individual discrete locations along the track (Fig. 3, A and B) and were biased toward the current location of the animal, indicative of a behavioral bias (fig. S4). We called these frames containing discrete location-depicting ensembles stationary frames. At P15–P16, we did not observe sequential replay of trajectories (Fig. 3C, left), even when the animals had prior navigational experience on the same linear track [Fig. 3, B (right two columns), and D]. Beginning on P17–P18, the activity during rest frames decoded segments of the run trajectory, which grew into extended track trajectories starting on P19–P20 (Fig. 3, A to C). From P15–P16 to P23–P24, the proportion of trajectory-depicting frames, likely replaying the extended run experience, increased gradually (Fig. 3C, left). At the same time, the strength of replay (i.e., strength of sequential trajectory-like representation by frames) and the extent of track being replayed also increased from P15–P16 to P23–P24 (Fig. 3C, middle and right). This developmental timeline of awake rest replay is important for two reasons. First, the frequent stationary frames during early development indicate that the hippocampal network initially operates in a persistent activity-like mode (26) at the neuronal ensemble level during offline rest epochs to represent individual spatial locations rather than sequential trajectories. The network ability to generate sequential motifs representing trajectories of sequentially explored locations develops at P17–P18 and gradually matures through P23–P24. Second, the emergence of compressed replay sequences precedes theta sequences by several days. This indicates that the phenomena of sequence compression during run (i.e., theta sequences) and during rest (i.e., awake replay) are mechanistically dissociable. This dissociation raises the question of whether offline expression of sequential motifs during rest or sleep requires prior explicit sequential spatial experience.

Fig. 3. Developmental timeline for trajectory-depicting sequences during on-track awake rest epochs.

(A) Neuronal ensemble activity during rest within first-time navigation (left panel) depicts individual locations at P15–P16 (stationary ensembles in frames, middle panel) and entire trajectories from P19–P20 (right panel). (B) Examples of stationary location-depicting frames and partial and entire trajectory–depicting frames across age groups during on-track rest epochs for first-time navigation (Day1Run, left 30 panels), within-day runs on same track (Day1Run2, middle 5 panels), and Day2Run on the same track (right 5 panels). Bayesian decoding analysis was used. (C) Age-dependent increases in proportion of significant trajectory-depicting frames (left; P < 10−4, ANOVA), correlation strength (middle; P < 10−10), and extent of depicted trajectory (right; P < 10−6). (D) Within-day (P = 0.92, paired t test) and previous-day (P = 0.67, t test) experience reveal no changes in the proportion of significant trajectory-depicting frames at P15–P16 and P16 (two directions per animal, n = 3 and 4 animals). Data are means ± SEM. ***P < 0.005; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05; ns, not significant.

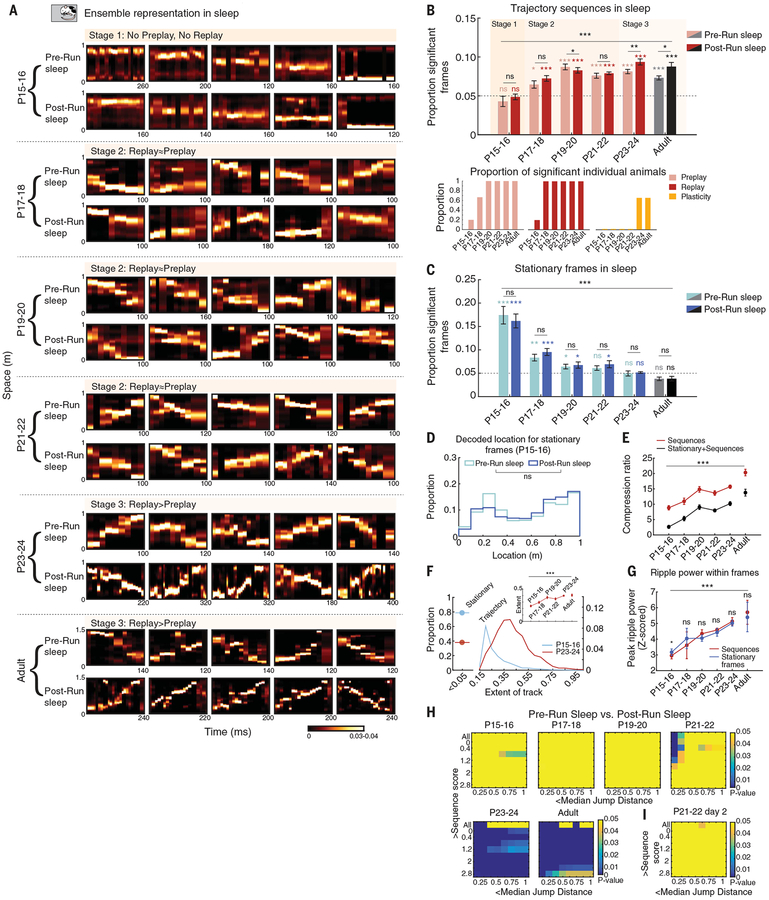

We therefore recorded hippocampal neuronal ensemble activity while naïve animals slept in a confined enclosure distinct from the linear track, prior to and following the de novo run session. We detected frames of activity during slow-wave sleep with continuous animal immobility (velocity <2 cm/s) at minimal theta power (see materials and methods and fig. S5). This allowed us to investigate the developmental time-line for Pre-Run sleep preplay and Post-Run sleep replay (Fig. 4A and fig. S6). Similar to awake rest, we did not observe preplay and replay sequences at P15–P16 during Pre-Run and Post-Run sleep (Fig. 4, A and B); instead, the network activity frequently organized into stationary frames (Fig. 4, A and C) depicting individual locations along the track (Fig. 4D). Short preplay and replay motifs emerged at P17–P18, and from P19–P20 the ensemble activity depicted extended run trajectories within individual frames (Fig. 4, A and B). Time compression of sequential experience by the neuronal ensembles increased gradually as a function of age, starting from minimal compression at P15–P16 and approaching adult-like values at P23–P24 (Fig. 4E). In parallel, the likelihood of observing stationary frames gradually decreased with age and reached chance levels consistently at P23–P24, while the spatial extent of de novo run trajectories represented by preplay and replay increased with age (Fig. 4, C and F), with no relationship to the isolation quality of units (fig. S7). We further determined that the sequential network properties were not due to inhomogeneities in firing rate characteristics across single neurons (fig. S8) or large discontinuities (i.e., jumps) in the decoded trajectory (fig. S9) and hence represented higher-order ensemble organization. Similarly, age-dependent changes in sequential properties were not due to differences in the amount of on-track experience (fig. S10) or improved spatial representation during a run (fig. S11). Overall, the spatial experience–depicting frames co-occurred with 140- to 250-Hz ripple oscillations. The ripple oscillations exhibited an age-dependent increase in power, duration, incidence, and likelihood to occur in doublets (Fig. 4G and fig. S12). The expression of preplay of future de novo run sequences in the absence of any structured experience on linear environments and before emergence of compressed theta sequences during a run suggests that the development of preconfigured sequential motifs (27) is an age-dependent, potentially innate process that is likely independent of sequential experience.

Fig. 4. A three-stage developmental timeline for experience-dependent trajectory replay during sleep.

(A) Examples of stationary location–depicting (P15–P16), partial trajectory–depicting (P17–P18), and entire trajectory–depicting (from P19–P20) frames across age groups during sleep preceding first-time navigation (Pre-Run, preplay) and postnavigation sleep (Post-Run, replay) using Bayesian decoding. (B) (Top) Age-dependent increase in proportion of trajectory-depicting frames during Pre-Run (i.e., preplay) and Post-Run (i.e., replay) sleep (P < 10−10, ANOVAs) and age- and experience-dependent increased replay vs. preplay at P23–P24 (P < 0.009, t test). Color backgrounds demarcate the three stages. (Bottom) Preplay, replay, and plasticity at the individual animal level across development. (C) Age-dependent and navigational experience–independent decreases in stationary location–depicting frames in Pre-Run and Post-Run sleep (P < 10−7, ANOVAs). (D) Distribution of decoded track locations from ensemble activity within stationary frames at P15–P16. (E) Developmental timeline for time compression of decoded trajectory (P < 10−10, ANOVAs). (F) Proportions of stationary frames out of all significant frames (>shuffles, stationary and trajectory-depicting; left) and distributions of extents of decoded track (right) at P15–P16 and P23–P24. (Inset) Age-dependent increase in extent of decoded trajectory (P < 10−8, ANOVA). (G) Age-dependent increase in ripple power associated with location- and trajectory-depicting sleep frames during Pre-Run sleep (P < 0.004, ANOVAs). (H) Cross-development, two-parameter analysis of experience-dependent plastic changes in decoded trajectory from Pre-Run to Post-Run sleep (replay > preplay starting at P23–P34, Z-test for two proportions). (I) Prior navigational experience does not accelerate expression of Pre-Run to Post-Run sleep plasticity at P21–P22 (day 2, replay ≈ preplay). Data are means ± SEM. For (B) to (I), ***P < 0.005; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05; ns, not significant. In (B) and (C), colored asterisks indicate P values from comparisons with chance.

Improved trajectory representation during sleep replay over preplay has been proposed as a critical mechanism for episodic-like memory formation (5, 28). We investigated whether and when during development the strength and incidence of trajectory replay exceeded those of trajectory preplay. Experience-dependent plasticity, marked by a higher incidence and a higher strength of replay compared to preplay, emerged at P23–P24, when it exhibited adult-like characteristics (Fig. 4, B and H). We did not observe plasticity in location-depicting ensembles or trajectory sequences at younger ages, despite expression of preconfiguration in the form of preplay and replay phenomena as early as P17–P18 (Fig. 4H and figs. S13 to S16, two-parameter comparison). This suggests that network preconfiguration does not emerge as a result of unaccounted sequential experience in the home cage before P17–P18, as an explicit sequential experience on a linear track did not result in robust theta sequences and offline sequence plasticity until P23–P24. Previous-day navigational experience did not accelerate the developmental emergence of age- and recent experience–dependent plasticity in experienced P21–P22 animals (Fig. 4I). These results indicate that hippocampal ensembles exhibit reduced stimulus-related plasticity during the critical period, including their experience in the home cage, in apparent contrast with the heightened plasticity observed in the developing sensory cortex (12). This suggests that the age-dependent emergence of time-compressed trajectory sequences (Fig. 4G) depends on intrinsic, instructive signals likely provided by the upstream developing stellate cell network of the entorhinal cortex (16).

We have identified distinct stages in the development of sequential patterns in neuronal ensembles in the rat, which we propose are important for the relational binding of events and episodic-like memory formation, according to the following ethologically relevant scenario. In the first stage, the hippocampal network represents discrete locations explored in space but lacks the ability to bind them into temporally compressed trajectories. This occurs at P15–P16, an age when rats are naturally confined to the nest. The second stage is characterized by the emergence and gradual increase in the complexity of preconfigured sequential motifs (27) expressed during offline sleep or rest epochs in an age-dependent, navigational experience–independent manner (fig. S17). This stage begins around P17–P18 and continues to P21–P22, when rats start exploring increasingly beyond their nest (9). We suggest that the existence of genuine preconfigured sequential motifs at this stage is consistent with Kant’s proposal on the a priori requirement of mental constructs of space-time for the development of other cognitive faculties (29). The third stage is marked by age- and navigational experience–dependent representation of entire trajectories or episodes and begins around P23–P24.

This third stage is first characterized by the relational binding and encoding of past, current, and future sequential locations into compressed trajectory-like sequences within theta oscillations during navigation, likely associated with experience-dependent, spike time–dependent plasticity. The maturation of grid cells in the medial entorhinal cortex (MEC) in the fourth postnatal week could enable the emergence of theta sequences in CA1, which depend on the integrity of MEC in adult rats (20) [sleep sequence replay can be expressed independently of direct MEC input to CA1 (30)]. Long-term plasticity due to the extended sequential run experience is likely consolidated during the following sleep period via increased replay of the run trajectory compared to its pre-play (5). We propose that the coordinated development of time-compressed sequences during encoding and consolidation of sequential information via stronger replay in sleep at P23–P24 in the rat represents a critical network mechanism that could enable the emergence of episodic-like memory function.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank M. Picciotto and D. Lee for comments and J. Sibille and K. Liu for help.

Funding: This work was supported by a Whitehall Foundation grant, NARSAD Young Investigator Fellowship, Outstanding Early Investigator Award, Charles H. Hood Foundation Award, and the NINDS of the NIH under award number 1R01NS104917 to G.D. and a Gruber Science Fellowship to U.F. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Competing interests: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Data and materials availability: All data are available in the manuscript or the supplementary material. The reported data are archived on file servers at Yale Medical School.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Scoville WB, Milner B, J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 20, 11–21 (1957). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Squire LR, Psychol. Rev 99, 195–231 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eichenbaum H, Cohen NJ, Neuron 83, 764–770 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dragoi G, Tonegawa S, Nature 469, 397–401 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee AK, Wilson MA, Neuron 36, 1183–1194 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Travaglia A, Bisaz R, Sweet ES, Blitzer RD, Alberini CM, Nat. Neurosci 19, 1225–1233 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee JK, Wendelken C, Bunge SA, Ghetti S, Child Dev 87, 194–210 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wills TJ, Cacucci F, Burgess N, O’Keefe J, Science 328, 1573–1576 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Langston RF et al. , Science 328, 1576–1580 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.LeVay S, Wiesel TN, Hubel DH, J. Comp. Neurol 191, 1–51 (1980). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benedetti BL, Takashima Y, Wen JA, Urban-Ciecko J, Barth AL, Cereb. Cortex 23, 2690–2699 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maffei A, Turrigiano G, Prog. Brain Res 169, 211–223 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Keefe J, Nadel L, The Hippocampus as a Cognitive Map. (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1978). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dragoi G, Buzsáki G, Neuron 50, 145–157 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dragoi G, Tonegawa S, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 110, 9100–9105 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Donato F, Jacobsen RI, Moser MB, Moser EI, Science 355, eaai8178 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muessig L, Hauser J, Wills TJ, Cacucci F, Neuron 86, 1167–1173 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Skaggs WE, McNaughton BL, Wilson MA, Barnes CA, Hippocampus 6, 149–172 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Middleton SJ, McHugh TJ, Nat. Neurosci 19, 945–951 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schlesiger MI et al. , Nat. Neurosci 18, 1123–1132 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dragoi G, Tonegawa S, eLife 2, e01326 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang Y, Romani S, Lustig B, Leonardo A, Pastalkova E, Nat. Neurosci 18, 282–288 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pastalkova E, Itskov V, Amarasingham A, Buzsáki G, Science 321, 1322–1327 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Foster DJ, Wilson MA, Nature 440, 680–683 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davidson TJ, Kloosterman F, Wilson MA, Neuron 63, 497–507 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Egorov AV, Hamam BN, Fransén E, Hasselmo ME, Alonso AA, Nature 420, 173–178 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dragoi G, Tonegawa S, Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London B Biol. Sci 369, 20120522 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grosmark AD, Buzsáki G, Science 351, 1440–1443 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kant I, Critique of Pure Reason. (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 1781). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamamoto J, Tonegawa S, Neuron 96, 217–227.e4 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.