Abstract

Exposure to high levels of post-divorce interparental conflict is a well-documented risk factor for the development of psychopathology and there is strong evidence of a subpopulation of families in which conflict persists for many years after divorce. However, existing studies have not elucidated differential trajectories of conflict within families over time, nor have they assessed the risk posed by conflict trajectories for development of psychopathology or evaluated potential protective effects of children’s coping to mitigate such risk. We used growth mixture modeling to identify longitudinal trajectories of child-reported conflict over a period of six to eight years following divorce in a sample of 240 children. We related the trajectories to children’s mental health problems, substance use, and risky sexual behaviors and assessed how children’s coping prospectively predicted psychopathology in the different conflict trajectories. We identified three distinct trajectories of conflict; youth in two high conflict trajectories showed deleterious effects on measures of psychopathology at baseline and the six-year follow-up. We found both main effects of coping and coping by conflict trajectory interaction effects in predicting problem outcomes at the six-year follow-up. The study supports the notion that improving youth’s general capacity to cope adaptively is a potentially modifiable protective factor for all children facing parental divorce and that children in families with high levels of post-divorce conflict are a particularly appropriate group to target for coping-focused preventive interventions.

Keywords: child psychopathology, divorce, interparental conflict, prevention, coping

Parental divorce or separation is the second most prevalent adverse childhood event (Sacks, Murphy, & Moore, 2014), and it affects 30–40% of children prior to the time they reach the age of 15 (Andersson, 2002; Kennedy & Bumpass, 2008). A recent population-based report estimates that more than eight million children in the United States live with a divorced parent (US Census Bureau, 2018). Despite being a highly prevalent stressful life event, the vast majority of children who experience parental divorce do not develop long-lasting problems (Amato, 1993, 2001; Amato & Sobolewski, 2001; Hetherington, Cox, & Cox, 1982). Nevertheless, youth who experience parental divorce, relative to their peers who remain in two-parent households, are at increased risk for a host of difficulties, including higher rates of psychopathology, substance use disorders, and academic underachievement (e.g., Amato, 2000).

Exposure to high levels of interparental conflict is one of the most well-documented factors accounting for the increased risk for problem outcomes of children who experience parental divorce (Amato, 1993, 2001; Amato & Sobolewski, 2001; Johnston, 1994; Kelly, 2012). This is not surprising considering that conflict between parents is a significant risk factor for the development of psychopathology in children, regardless of family structure (Cummings & Davies, 2010). There is a great deal of evidence that interparental conflict is related to internalizing and externalizing problems, as well as academic problems, in children in divorced families (Amato, 1993; Buchanan, Maccoby, & Dornbusch, 1991; Buehler et al., 1997; E. Hetherington & Kelly, 2002; J. R. Johnston, 1994; Kelly & Emery, 2003; Kline, Johnston, & Tschann, 1991; Long, Slater, Forehand, & Fauber, 1988; Shaw & Emery, 1987; Vandewater & Lansford, 1998). Some evidence suggests that interparental conflict may become even more salient for youth after divorce compared to those in married families, due to increases in the intensity of interparental conflict, conflicts over loyalty to the divorced parents (i.e., denigration or badmouthing of the other parent), and an increased focus on child-related issues (Grych, 2005).

Prevalence and Profiles of Post-divorce Interparental Conflict

Some degree of conflict around the time of separation and divorce is typical among divorcing parents (Hetherington et al., 1982) and can be seen as a marker of the stressful, but normal, process that parents experience as they reorganize their family life. Interparental conflict typically diminishes within the first few years of separation, but some parents remain embroiled in conflict for many years following divorce (Hetherington & Kelly, 2002; Hetherington et al., 1982; King & Heard, 1999). For example, the landmark longitudinal study by Hetherington and colleagues documented that 20–25% of parents reported engaging in conflictual behavior six years post-divorce (Hetherington & Kelly, 2002). Another study of families mired in custody disputes found that 15–20% of mothers and fathers reported ongoing conflict at the 12-year follow-up (Sbarra & Emery, 2005). Other researchers have used cross-sectional designs to describe how the level of interparental conflict differs over time following divorce. A large, nationally representative study of divorced adults in the Netherlands showed that among those with children, 56–67% reported antagonistic contact one year after divorce (Fischer, de Graaf, & Kalmijn, 2005). In the group that were 3–10 years post-divorce, 26–29% reported antagonistic contact and among those who had been divorced for more than 10 years, 10% reported antagonistic contact.

These data provide important snapshots of the prevalence of interparental conflict following divorce and establish firm evidence of persistent high levels of conflict in a subpopulation of divorcing families (Fischer et al., 2005; Hetherington & Kelly, 2002). However, the current data are limited in that they only provide percentages of divorced families with high levels of conflict at different points in time, but do not describe differential patterns or trajectories of conflict within families over time. We are not aware of any published peer-reviewed study that has examined profiles of within-family change in interparental conflict over time.1 This is a critical gap in the literature because different trajectories of conflict over time may have different implications for children’s psychopathology and well-being. For example, in some families, interparental conflict may always be relatively low, whereas in others, it may be high at the time of separation but decrease over time, or the level of conflict may start high and remain high for several years following the divorce. Despite many scholars surmising that chronic conflict is likely to be the most damaging for children (e.g., Grych, 2005; Smyth & Moloney, 2017), researchers have not assessed the effects that differential trajectories of exposure to interparental conflict may have on children’s psychopathology. Elucidating distinct longitudinal trajectories and their prospective associations with children’s psychopathology, as well as factors that may predict which trajectory a family is likely to follow (e.g., parental hatred [Smyth & Moloney, 2019], child age, concerns about the other parent’s parenting behavior, legal conflict, parental psychopathology [Johnston, 1994], co-parenting arrangements [Bauserman, 2012; Nielsen, 2017]), is key to identifying high-risk families who may benefit from preventive interventions.

Another limitation of the literature on levels of exposure to conflict over time is that all studies use parent rather than child reports of conflict. The relation between parent and child report of interparental conflict in divorced families is relatively modest and variable, ranging from r = .21 - .61 across studies (Camisasca, Miragoli, Di Blasio, & Grych, 2017; Fear et al., 2009). Research indicates that children’s perception of the conflict is key to the processes that link exposure to mental health problems (Grych & Fincham, 1993; Grych, Harold, & Miles, 2003), and that children’s reports of conflict are more strongly related to measures of their adjustment problems than are parent reports of conflict (Cummings, Davies, & Simpson, 1994; Grych, Seid, & Fincham, 1992).

Theoretical Frameworks for Understanding the Relations between Interparental Conflict and Child Psychopathology

Two major theoretical frameworks have been proposed to describe the processes by which exposure to interparental conflict influences children’s psychopathology and well-being. The Emotional Security Theory (EST) posits that exposure to interparental conflict threatens a child’s sense of emotional security within the family system and specifically within the parental subsystem (Davies & Cummings, 1994). An impaired sense of safety and security in the family system interferes with the child’s capacity to regulate emotions and behaviors in the face of stress, which confers risk of psychopathology and other forms of maladjustment (Cummings & Davies, 2010; Cummings, George, McCoy, & Davies, 2012). Another prominent theory, the Cognitive-Contextual Framework (CCF), focuses on children’s cognitive reactions to the conflict as the key mediators linking exposure and development of psychopathology (Grych & Fincham, 1990). CCF posits that the child’s cognitive appraisal of the conflict event is influenced by the context in which the conflict occurs, which in turn, determines their emotional and behavioral responses, such as reactivity and coping efforts. Research based on this framework found that children’s negative cognitive appraisals of the conflict are critical determinants of their subjective distress and the negative impact of the conflict on their well-being (Grych & Fincham, 1993). For example, studies showed that the extent to which children felt threatened and blamed themselves in response to interparental conflict mediated the association between interparental conflict and the development of internalizing and externalizing problems (Grych, Fincham, Jouriles, & McDonald, 2000; Grych et al., 2003).

Effective Coping as a Protective Factor against the Effects of Interparental Conflict

There is considerable evidence that children’s coping behaviors can be protective, leading to better adjustment for children who experience a wide range of stressors (Compas et al., 2017). For children from divorced families, active coping strategies, such as problem solving and cognitive reframing, have been found to be associated with lower child mental health problems cross-sectionally and five months later (Sandler, Tein, & West, 1994). Similarly, higher use of secondary control coping strategies, such as distraction and acceptance, in response to interpersonal stressors is associated with fewer mental health problems in youth with depressed parents (Jaser et al., 2007). The overarching goal of effective coping is to regulate emotional responding and reduce risk of becoming overwhelmed during stressful moments and to solve problems and marshal resources to enable children to successfully meet the challenges posed by stressful events. In this way, effective coping may mitigate the pathways in the EST and CCF theoretical models that link exposure to interparental conflict and development of psychopathology. For example, from the perspective of EST, coping strategies might counteract the extent to which children’s emotional safety and security is undermined (Cummings & Davies, 2010), thereby decreasing negative appraisals, such as self-blame or threat, (Grych & Fincham, 1990) and reducing emotional reactivity (Cummings, Schermerhorn, Davies, Goeke-Morey, & Cummings, 2006). From the perspective of the CCF, coping strategies may enable children to appraise conflict in ways that involve less blame of themselves or others. Before discussing the ways in which coping may counteract the theoretical pathways through which conflict may affect the development of child psychopathology, it is first necessary to discuss research on the assessment of the dimensions of children’s coping strategies.

There is consensus in the literature that at the broadest level, a useful distinction is made between coping efforts that are active or approach-oriented versus avoidant or disengagement-oriented (Ayers, Sandler, & Twohey, 1998; Billings & Moos, 1981; Compas, Connor-Smith, Saltzman, Thomsen, & Wadsworth, 2001). Within the domain of active coping, however, scholars and researchers have demarcated subtypes that comprise different strategies (i.e., cognitive or behavioral efforts to modify one’s experience of a stressor) in a variety of ways. The most widely recognized model by Lazarus and Folkman (1987) distinguishes subtypes of coping based on whether one’s efforts are focused on regulating emotions that arise in reaction to the stressor (i.e., emotion-focused) or making a direct impact on the stressors itself (i.e., problem-focused). This typology has frequently been applied to the search for matching coping strategies to context, as emotion-focused strategies are often presumed to be adaptive in the face of uncontrollable stressors, whereas problem-focused strategies are seen as adaptive in situations in which the individual has the ability to exert control and modify the stressor itself (Compas, Banez, Malcarne, & Worsham, 1991; Compas et al., 2017; Kerig, 2001). More recently, Compas and colleagues advocated for distinguishing active (i.e., engagement) strategies according to the motivational goals underlying one’s coping efforts, namely primary control (those focused on changing the situation or the consequences of one’s reaction to the situation; e.g., problem solving, emotion regulation, hiding emotional expression) and secondary control (those focused on adapting to the situation; e.g., cognitive reappraisal, distraction, acceptance, positive thinking) (Compas et al., 2001; Connor-Smith, Compas, Wadsworth, Thomsen, & Saltzman, 2000).

A growing area of research has investigated the effects of different coping strategies as vulnerability or protective factors for children exposed to interparental conflict and parental divorce. Several studies with children from married families have investigated whether children’s coping with interparental conflict moderates the relations between exposure to conflict and children’s psychopathology (e.g., Nicolotti, El-Sheikh, & Whitson, 2003; Shelton & Harold, 2008; Tu, Erath, & El-Sheikh, 2016). Illustratively, Tu et al. (2016) found that higher levels of engaged secondary control strategies (e.g., positive thinking) protected against the effects of conflict on externalizing problems, whereas higher levels of both engaged primary (e.g., problem solving) and secondary control coping (e.g., cognitive restructuring) with conflict increased risk from exposure to conflict on internalizing problems. To our knowledge, only one study has investigated whether children’s general style of coping with stressors moderates the effect of conflict on mental health problems (Shelton & Harold, 2007). This study, which was conducted with children in married families, found that higher levels of coping by venting negative emotion exacerbated the prospective relations between conflict and higher levels of anxiety-depression. We know of no study that has studied children’s coping with interparental conflict following divorce and only one has studied children’s coping as a moderator of the effects of post-divorce stressors on children’s psychopathology in divorced families. Although this study did not specifically study coping as a moderator of post-divorce interparental conflict, it did find that an active coping style, comprised of positive cognitive restructuring and problem-focused coping, was a significant moderator of the negative effects of multiple divorce-related stressors (including interparental conflict) on children’s mental health problems (Sandler et al., 1994).

An alternative perspective for understanding the effects of coping on children’s adjustment to interparental conflict is to focus on efficacy of coping rather than specific strategies that are used to cope with stress. Coping efficacy refers to people’s subjective appraisals as to how effective their coping efforts were in dealing with the demands of the stressful situation. Theoretically, an appraisal of coping efficacy can impact the level of emotional arousal in a stressful situation and can influence the likelihood of using effective coping strategies to deal with future stressors (Bandura, 1997; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984; Skinner & Wellborn, 1994). Appraisals of coping efficacy may be made for specific situations, and with repeated success may lead to a general belief that one can successfully deal with the stressors in one’s life. It may be that the feelings of efficacy, rather than the specific coping strategy, most strongly predicts children’s ability to adapt to the stressor. Theoretical models posit that coping efficacy can increase the likelihood that one will use a strategy they expect to work and diminish negative emotional reactivity in response to a stressor (Lazarus, 1991; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984), as well as facilitate effective regulation of thoughts and feelings during stressful situations (Bandura, 1997). Previous evidence indicates that coping efficacy mediates exposure to interparental conflict and children’s distress reactions (Camisasca et al., 2017) and mental health outcomes (Cummings et al., 1994) in married families. In divorced families, general coping efficacy has been shown to mediate the association between active and avoidant coping strategies and children’s psychopathology, with active coping strategies being associated with higher levels of coping efficacy and lower mental health problems and avoidant strategies being associated with lower levels of coping efficacy and higher mental health problems (Sandler, Tein, Mehta, Wolchik, & Ayers, 2000). Based on these findings, in addition to studying which coping strategies are protective or detrimental for children in high conflict situations, it is also crucial to understand the role of general coping efficacy for children who are exposed to different trajectories of interparental conflict over time.

Coping in Context

Understanding effective coping requires that we consider the context of the stressor (Aldao, 2013; Forsythe & Compas, 1987; Greenaway, Kalokerinos, & Williams, 2018). For example, one contextual factor is whether the conflict occurs between parents who are married or parents who are separated or divorced. In married families, interparental conflict may lead children to experience a lack of security of the continuation of the family unit (Cummings and Davies). In divorced families, the threat from conflict may involve issues such as concern about the well-being of the parents or of the children’s continued relationship with one of the parents (e.g., Sheets, Sandler, & West, 1996). Little research has focused on youth coping processes in the context of post-divorce interparental conflict (for an exception focused on litigating families, see Radovanovic, 1993). More broadly, the vast majority of studies examining the links between interparental conflict and psychopathology has been conducted with youth from married families (Cummings & Davies, 2010; Fosco & Grych, 2008).

Sandler (2001) proposed that the ecology of adversities themselves (i.e., setting, temporal and cumulative nature) as key contextual factors to understanding the associated risks and likely outcomes of experiencing adversity during childhood. Several aspects of the ecology of interparental conflict have been studied in depth and researchers have found that such conflict has a more negative effect on children when it crosses domains (e.g., financial, parenting practices), has a high level of intensity (i.e., anger, hostility, physical aggression), and when it goes unexplained or unresolved (Goeke-Morey, Cummings, & Papp, 2007; Ha, Bergman, Davies, & Cummings, 2018). However, the temporal and cumulative nature of interparental conflict, and how these characteristics are related to the development of children’s psychopathology, have rarely been studied. Although prior research has shown that the mean level of post-divorce conflict decreases over time following divorce, the mean level of change likely masks different trajectories of change in conflict across families. Differential trajectories of exposure to interparental conflict over time is a potentially critical aspect of the ecology of conflict, as the temporal quality of adverse conditions is a well-documented predictor of negative outcomes related to stressful events in general (Danese & McEwen, 2012; Wadsworth, 2015). It may be that different trajectories of conflict over time have differential effects on children. For example, does the effect of post-divorce conflict on children differ if it occurs for a relatively short period following separation and then dissipates over time as compared with divorces in which the level of conflict is never very high and remains low over time, or with divorce in which the children are exposed to chronic high levels of conflict for many years? Furthermore, how do different coping strategies or perceptions of coping efficacy predict child psychopathology outcomes over time in the context of exposure to different trajectories of conflict? We argue that elucidating how different trajectories of exposure to conflict over time are associated with children’s mental health and further, how coping is related to child outcomes in the context of those different trajectories, will provide information that will help identify high-risk families and better understand children’s risk for psychopathology after divorce.

Current Study

The present study addresses critical gaps in the literature on the relations between interparental conflict and the development of psychopathology for children from divorced families by: (1) identifying trajectories of post-divorce interparental conflict over time and factors that predict differential trajectories of conflict, 2) assessing the relations between trajectories of conflict over time and psychopathology of children, and 3) assessing how children’s coping prospectively predicts the development of psychopathology for children exposed to different trajectories of interparental conflict following divorce.

First, we employed growth mixture modeling to identify subgroups of children exposed to different trajectories of interparental conflict over a 6–8-year period following parental divorce. We hypothesized that there would be distinct trajectories of IPC over time, including a group characterized by stable, low levels of conflict; a group characterized by stable, high levels of conflict; and a group demonstrating declines in conflict over time (i.e., high-to-low). Given previous evidence that the majority of families report conflict in the first year following divorce, and a subgroup of approximately 20–30% report some degree of conflict several years after separation (Hetherington & Kelly, 2002; Hetherington et al., 1982; King & Heard, 1999), we expected the smallest group to be represented by a trajectory of chronically high interparental conflict over time. We speculate that there might be groups that have different trajectories than those described above. For example, a fourth group might be characterized by levels of conflict that fluctuate over time based on the presence or absence of other stressors, such as the remarriage of one parent, which we know from previous research is very common by six years post-divorce (i.e., 70–80%; Hetherington & Kelly, 2002). However, given the spacing of our measurement occasions, we were not sure that this group could be identified in the current study.

After identifying subgroups based on longitudinal trajectories of conflict, we then explored the relations between theoretically-derived predictors (e.g., the residential parent’s feelings about the other parent’s relationship with the child, allocation of parenting time, child gender and age, and absence of the non-residential parent) and interparental conflict trajectories. We then examined the relations between interparental conflict trajectories and children’s mental health at the first time point of the trajectories and mental health and substance use problems and risky sexual behavior at the last time point. We expected that the group characterized by chronically high levels of interparental conflict over time would demonstrate the highest levels of problematic outcomes. Finally, we tested main and interactive effects of children’s coping styles (i.e., problem-focused, cognitive restructuring, avoidant) and coping efficacy with trajectories of conflict to prospectively predict mental health problems, substance use, and risky sexual behavior six years later.

Method

Participants

Participants were 240 youth ages 9–12 whose mothers participated in a clinical trial of a preventive intervention, the New Beginnings Program (NBP), within two years of filing a divorce decree (see Wolchik et al., 2002 for full details about the eligibility criteria and intervention). Families were primarily identified through random selection of decrees in a computerized court record system and invited to participate via letters and telephone calls. Eligibility criteria included: (1) fluency in English, (2) no current mental health treatment for mother or child, (3) primary maternal residential custody, (4) no remarriage, cohabitation, or plans to remarry for the mother, and (4) no planned changes to custody arrangements during the study period. Families were referred out for treatment when deemed necessary based on predetermined criteria (i.e., score of higher than 17 on the Children’s Depression Inventory [Kovacs, 1985], endorsement of suicidal ideation, or score higher than the 97th percentile on the Externalizing subscale of the Child Behavior Checklist [Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001]). The average time since the date of parental separation was 26.88 (SD = 17.23) months and the average time since the legal divorce was 12.23 (SD = 6.41) months. Participants were randomly assigned to one of two intervention conditions, mother program (MP) or mother program plus child program (MPCP), or an active literature control condition (LC).

Procedure

The current study used data from the first five waves of the NBP study, which includes baseline (T1), posttest (T2), three-month follow-up (T3), six-month follow-up (T4), and six-year follow-up (T5). The posttest occurred approximately three months after pretest. Of those 240 families who completed the pre-test, 98% (234–236 families) completed assessments at T2-T4 and 91% (218 families) of the sample was retained at the six-year follow-up (T5). Youth and mothers were interviewed in their homes by trained research staff and informed consent/assent was obtained from all participants. Families were compensated $45 at T1-T4 and both mothers and children were compensated $100 at T5.

Measures

Interparental conflict.

Youth’s perception of frequency and intensity of interparental conflict was assessed at each measurement occasion (T1-T5) using the 6-item frequency and 7-item intensity subscales of the Children’s Perception of Interparental Conflict scale (CPIC; (Grych et al., 1992). “Your parents got really mad when they argued” and “You never saw your parents arguing or disagreeing” are examples of intensity and frequency items, respectively. The CPIC was rated on a 3-point scale (1 = true, 3 = false) and scored as an average rating, with higher scores indicating higher levels of perceived interparental conflict. The CPIC has well-established psychometric properties in samples of children and adolescents (Bickham & Fiese, 1997; Grych et al., 1992). Internal consistency for this sample ranged from α = .74 - .88 across T1-T5. At six-year follow-up, items assessing child-report of interparental conflict were skipped for youth who reported no contact with their fathers or no contact between their parents, as it was assumed that under these conditions there was no opportunity for exposure to interparental conflict, making the items irrelevant. Thus, for these participants, the interparental conflict variable was coded as zero, the lowest possible score, to represent no exposure to conflict.

Youth coping efforts and coping efficacy.

Youth dispositional coping was assessed using the 36-item Child Coping Strategies Checklist - Revised (CCSC-R; Ayers, Sandler, West, & Roosa, 1996) at each measurement occasion (T1-T5). Assessments of coping and coping efficacy (see below) at the first four waves (T1-T4) were used in the current study. The 12-item Avoidant Coping (e.g., “You tried to stay away from things that upset you”), 12-item Positive Cognitive Restructuring Coping (e.g., “You told yourself that it would be okay”), and 12-item Problem-focused Coping (e.g., “You tried to make things better by changing what you did”) subscales were treated as separate constructs for the purposes of the current study. CCSC-R items were rated on a 4-point scale (1 = never, 4 = most of the time) and scored as an average, with higher scores indicating more use of coping strategies within the respective category. Ranges of internal consistency for this sample were α = .68 - .81 across T1-T4 for Avoidant Coping, α = .82 - .90 across T1-T4 for Positive Cognitive Restructuring Coping, and α = .79 - .90 across T1-T4 for Problem-focused Coping. Previous research has linked these aspects of children’s coping with mental health problems in children who have experienced divorce (Sandler et al., 2000).

Youth also completed the 7-item Coping Efficacy Scale (CES; (Sandler et al., 2000), a measure of their satisfaction with the way they have handled problems in the past and the way they anticipate handling problems in the future, at each measurement occasion. This scale has been shown to be negatively related to children’s internalizing and externalizing problems in previous studies (Sandler et al., 2000). An illustrative item is “Overall, how well do you think that the things you did during the last month worked to make the situation better?” The CES was rated on a 4-point scale (1 = did not work at all, 4 = worked very well) and scored as an average rating, with higher scores representing higher levels of coping efficacy. Internal consistency for this sample ranged from α = .71 - .83 across T1-T4.

For the purposes of this study, we created longitudinal composite measures of each coping construct by averaging ratings across the first four measurement occasions (T1-T4) to gain a better global assessment of the child’s coping across the first year of the study (which was within approximately 2–3 years of the divorce). To assess longitudinal stability in the measurement of coping, we first examined intercorrelations across the four waves. The correlation coefficients ranged from r = .33 to .61, with adjacent scores being more strongly correlated (e.g., T3 and T4 correlations ranged from r = .56-.61). We further assessed longitudinal stability of our coping measures using the trait-state measurement model (STARTS; Kenny & Zautra, 2001) to increase our confidence in creating a composite of coping assessments across study waves. Results indicated that the stable components (i.e., trait and autoregressive latent factors) accounted for the majority of variance in the repeated assessments of coping at T1-T4, ranging from 62% for problem-focused coping to 91% for avoidant coping. The random component (i.e., state or occasion-specific factor) accounted for 9–38% of the variance. Because the proportion of the total variance explained by the stable components exceeded the variance explained by the random component, which supported the assumption of longitudinal stability of coping style over this period, we created a composite of coping scores across this 1-year period.

Youth mental health problems.

Internalizing and externalizing problems were assessed at each measurement occasion (T1-T5), and data for the current study include baseline (T1) and six-year follow-up (T5) assessments. Youth completed the 27-item Child Depression Inventory (CDI; Kovacs, 1985) and the 28-item revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale (RCMAS; Reynolds & Richmond, 1978). These inventories have well-established reliability and validity data (Lee, Piersel, Friedlander, & Collamer, 1988; Reynolds, 1981; Reynolds & Paget, 1981; Saylor, Finch, Spirito, & Bennett, 1984; Timbremont, Braet, & Dreessen, 2004). For the current sample, internal consistency estimates for the CDI were α = .76 (T1) and .85 (T5) and for the RCMAS were α = .88 (T1) and .89 (T5). Scores from these two measures were standardized and average to form a composite representing internalizing problems. As a measure of externalizing problems, youth completed the 25-item Divorce Adjustment Project Externalizing Scale, based on the Youth Self-report Hostility Scale (Cook, 1986) at T1, and a 27-item questionnaire comprised of the original 25 items and 2 additional items from the Youth Self-Report (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001) to assess delinquent behavior at T5. In the current study, internal consistency was α = .83 at T1 and α = .84 at T5. We used standardized scores from this sample for youth self-report of internalizing and externalizing problems in all analyses.

Mothers completed the 31-item internalizing subscale and the 33-item externalizing subscale of the Child Behavior Checklist (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001). This inventory has demonstrated good psychometric properties, including test-retest and internal consistency reliability as well as construct and predictive validity. Internal consistency estimates in this sample were α = .88 at T1 and α = .86 at T5 for the internalizing subscale and α = .87 at T1 and α = .89 at T5 for the externalizing subscale. In the current study, mother reports of internalizing and externalizing problems are represented by norm-referenced T scores.

At T5, mental health and substance use disorders were assessed using youth and parent versions of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC; Shaffer, Fisher, Lucas, Dulcan, & Schwab-Stone, 2000). Diagnoses were made based on two criteria: (1) youth met diagnostic criteria for at least one mental health or substance use disorder based on either self or parent report, and (2) if diagnostic criteria were met, impairment was rated as intermediate or severe by endorsement of at least two items. For these analyses, we used a dichotomous outcome variable representing presence or absence of any mental health or substance use disorder diagnosis. Mental health disorders and substance use disorders were used as separate outcomes.

Youth substance use.

At T5, youth completed a self-administered questionnaire with selected items from the Monitoring the Future Scale (Johnston et al., 2018), which has established reliability and validity psychometric qualities. Alcohol and marijuana use were measured on a 7-point scale representing the number of times youth had used the substance during the past year (1 = 0 to 7 = >40). We analyzed past year alcohol and marijuana use separately.

Youth risky sexual behavior.

At T5, youth reported on the number of different sexual partners they had since their mothers and/or they had completed the intervention via a self-administrated questionnaire.

Family variables.

Family variables collected at T1 that were used in the current analyses included the number of overnights per month that the child spent with their non-residential parent (ranging from 0–30), time elapsed since the separation, whether or not the child’s father moved out of the geographic area or remarried (dichotomous yes/no), and the extent to which the mother held a positive view of the child’s relationship with their father (assessed by an average rating on 6 items developed in-house; illustrative item is “How do you feel about your ex-spouse having a relationship with your child?” rated on a 7-point scale where 1 = strongly discourage it, 7 = strongly encourage it; α = .85).

Covariates.

For the current study, we used demographic variables of child age and gender, and one study design variable, intervention condition (because the current study did not focus on intervention effects), as covariates in statistical analyses to account for variance explained by these factors extraneous to our primary research questions. Autoregressive controls of baseline mental health problems were included for analyses on youth- and parent-reported internalizing and externalizing problems, but because substance use and risky sexual behaviors were only assessed at T5, no autoregressive controls were included for these outcomes.

Data Analysis Approach

For preliminary analyses, we performed regression diagnostics by examining global influence statistics to identify potentially influential cases and then inspecting the observed change in the coefficients of theoretical predictors when the potentially influential case was included (using cutoffs proposed by Cohen, Cohen, West, & Aiken, 2003). We also identified cases with a Cook’s distance exceeding .20 (Bollen & Jackman, 1985). The results of these procedures identified two potentially influential cases across all analyses. Analyses were run with and without these data; for analyses in which the results changed when the influential case was excluded, we report the discrepancy.

All of the analyses were conducted with Mplus (Version 8; Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2017). We used full information maximum likelihood to handle missing data due to attrition in longitudinal analyses. To characterize longitudinal trajectories of change in interparental conflict, we conducted growth mixture modeling (GMM) analyses to identify the number of unobserved subgroups based on patterns of change in children’s reports of interparental conflict across five waves (T1-T5). Prior to modeling, we assessed longitudinal measurement invariance of our measure of interparental conflict (see Preliminary Analyses section). Specifically, we tested longitudinal measurement invariance using a categorical factor model approach with weighted least squares mean and variance (WLSMV) estimation and the probit link to define observed variable thresholds due to the ordinal nature of the item response options (see Grimm, Ram, & Estabrook, 2016; Millsap & Yun-Tein, 2004).

We evaluated a 2, 3, and 4-class growth mixture models. We repeated models with multiple sets of start values to avoid getting local maximum solutions and ensure the best log-likelihood value was replicated (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2017). We determined the optimal number of classes based on Bayesian information criterion (BIC; Schwarz, 1978), sample-size adjusted Bayesian information criterion (SABIC; Sclove, 1987), Vuong-Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio test (VLMR; Lo, Mendell, & Rubin, 2001), and parameter bootstrapped likelihood ratio test (BLRT; McLachlan & Peel, 2000) and substantive interpretations (see Tein, Coxe, & Cham, 2013). In addition, we relied on entropy to gauge whether the latent classes were highly discriminating (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2017). We fixed the covariance between intercept and slopes within class to zero to aid model convergence and avoid Heywood cases (i.e., negative variances). Assuming high entropy (> .80) and using the optimal class solution, each child was assigned to the most likely class based on the estimated posterior probabilities for each class. We then used the classification variables to examine the remaining hypotheses: 1) examining trajectory (entered as dummy variables) mean differences in child mental health at baseline (T1) as well as child mental health and risky sexual behavior outcomes at six-year follow-up (T5) and 2) examining the moderation effects of coping styles and global coping efficacy on the relations between conflict trajectories and children’s mental health and substance use problems and risky sexual behavior.

Applying dummy coding for the classification variable of the trajectory, we used multiple regression analyses to examine differences of child mental health and substance use outcomes at baseline and six-year follow-up among the latent classes. We used negative binomial regression for the risky sexual behavior outcome because it was a count variable (i.e., number of sexual partners) with the majority of the sample (57.9%) reporting a value of zero.

Finally, we conducted moderation analyses to test interaction effects between trajectories and the coping subscales on T5 prospective mental health (child-reported internalizing and externalizing problems, mother-reported internalizing and externalizing problems, and mental health diagnoses), substance use (past year alcohol and marijuana use), and risky sexual behavior (number of sexual partners). Following moderation analyses, we conducted post-hoc comparisons for significant interactions to determine which trajectories differed significantly. We plotted the slopes within each trajectory and assessed significance of the within-group simple slope relating the coping measure to the outcome. For analyses in which the interaction effect was non-significant, we removed the interaction term and tested the additive effect of the coping subscales. We report only significant effects from moderation analyses in the results section.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Table 1 displays descriptive statistics and zero-order Pearson product moment correlations for all study variables and covariates. Children’s reports of interparental conflict were significantly and positively correlated across all time points, with the exception of T2 and T5; in general, T5 had the lowest intercorrelations with other time points. The subscales of coping were positively and significantly correlated, with the exception of avoidant coping and coping efficacy. Mother and youth reports of internalizing and externalizing problems were significantly correlated. There was a strong correlation between past year alcohol and marijuana use and both types of substance use were moderately correlated with risky sexual behavior.

Table 1.

Intercorrelations and Descriptive Statistics for Study Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. T1 CPIC | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 2. T2 CPIC | .52 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| 3. T3 CPIC | .50 | .45 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| 4. T4 CPIC | .39 | .47 | .47 | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| 5. T5 CPIC | .16 | .11 | .24 | .24 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| 6. Coping Efficacy (T1-T4) | −.07 | −.15 | −.17 | −.16 | .00 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| 7. Cognitive Coping (T1-T4) | −.01 | −.07 | .05 | −.12 | .07 | .61 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| 8. Problem-focused Coping (T1-T4) | .04 | −.02 | .08 | −.06 | .12 | .56 | .81 | 1 | |||||||||||

| 9. Avoidant Coping (T1-T4) | .26 | .19 | .21 | .07 | .04 | .15 | .50 | .44 | 1 | ||||||||||

| 10. Youth-reported Externalizing T1 | .28 | .29 | .24 | .23 | −.05 | −.21 | −.13 | −.08 | .08 | 1 | |||||||||

| 11. Youth-reported Internalizing T1 | .29 | .29 | .20 | .19 | .02 | −.33 | −.15 | −.04 | .18 | .52 | 1 | ||||||||

| 12. Youth-reported Externalizing T5 | .06 | .19 | .12 | .10 | .19 | −.23 | −.21 | −.12 | −.02 | .33 | .29 | 1 | |||||||

| 13. Youth-reported Internalizing T5 | .04 | .11 | .05 | .11 | .13 | −.27 | −.19 | −.09 | .00 | .18 | .36 | .61 | 1 | ||||||

| 14. Mother-reported Internalizing T1 | .16 | .18 | .02 | .19 | .03 | −.17 | −.15 | −.09 | .02 | .19 | .30 | .18 | .22 | 1 | |||||

| 15. Mother-reported Externalizing T1 | .14 | .10 | .04 | .14 | .11 | −.11 | −.09 | −.03 | .01 | .26 | .24 | .24 | .18 | .52 | 1 | ||||

| 16. Mother-reported Internalizing T5 | .10 | .10 | .11 | .03 | .11 | −.19 | −.16 | −.14 | .02 | .01 | .11 | .29 | .43 | .50 | .34 | 1 | |||

| 17. Mother-reported Externalizing T5 | .05 | .03 | .08 | .06 | .15 | −.09 | −.04 | −.08 | .04 | .01 | .03 | .34 | .20 | .23 | .58 | .55 | 1 | ||

| 18. Alcohol Use T5 | .05 | .07 | .12 | .11 | .10 | −.13 | −.13 | −.10 | −.05 | .14 | .12 | .33 | .21 | .14 | .15 | .13 | .23 | 1 | |

| 19. Marijuana Use T5 | .10 | .19 | .09 | .13 | .09 | −.12 | −.12 | −.08 | −.01 | .18 | .12 | .32 | .36 | .14 | .19 | .27 | .24 | .61 | 1 |

| 20. Sexual Partners T5 | .07 | .11 | .10 | .10 | .03 | −.18 | −.12 | −.11 | −.01 | .00 | .04 | .22 | .18 | .05 | .05 | .18 | .16 | .34 | .36 |

| Mean | 1.61 | 1.49 | 1.38 | 1.32 | 1.18 | 3.05 | 10.55 | 10.44 | 9.73 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 57.36 | 55.03 | 52.25 | 50.38 | 3.03 | 2.01 |

| SD | 0.45 | 0.44 | 0.38 | 0.34 | 0.37 | 0.34 | 1.76 | 1.74 | 1.58 | 1.00 | 0.89 | 1.00 | 0.92 | 9.59 | 8.48 | 9.34 | 9.82 | 1.99 | 1.75 |

Note. CPIC = Children’s Perception of Interparental Conflict scale (Grych et al., 1992). T1 = baseline, T5 = six-year follow-up.

Given our primary focus on longitudinal change in interparental conflict, we first tested the assumption that the measurement of these items was invariant across time to establish that we were measuring the same construct at different measurement occasions (Grimm et al., 2016; Pitts, West, & Tein, 1996). We first conduct a confirmatory analysis with the 13 items from the CPIC frequency and intensity subscales at T1. The model fit was adequate, χ2 (65) = 221.98, p < .01, RMSEA = .0101 [0.086 – 0.115], CFI = .905, TLI = .886). We dropped 3 items due to low contribution (i.e., low factor loading [β ≤ .30]; e.g., “parents discuss disagreement quietly”) and 1 item (“parents pushed/shoved during argument”) due to lack of variance at T5 (i.e., 99% of the sample gave one response); the final model included 9 items. Good model fit was confirmed at each subsequent time point and the poorest model fit statistics were across all five waves were χ2 (27) = 50.512, p < .01, RMSEA = .062 [0.035 – 0.089], CFI = .972, TLI = .963). We then fitted and evaluated evidence for configural, weak, and strong invariance models through a stepwise process of relaxing model constraints. There was no evidence of significant decreases in model fit according to global (i.e., no significant change in χ2) and absolute (i.e., CFI/TLI change of less than .01, RMSEA remained within confidence interval of less restrictive model) fit statistics. The strong factorial invariance fit the data well, χ2 (1035) = 1209.73, p < .001, RMSEA = .027 [0.019 – 0.003], CFI = .957, TLI = .959), and standardized factor loadings were positive and ranged from 0.56 – 0.98.

Aim 1: Characterize Longitudinal Trajectories of Child-Reported Interparental Conflict

Growth mixture model selection.

As our base model, we fitted a single-group piecewise growth model, with the first piece modeling change from T1-T4 and the second piece modeling change from T4-T5, based on previous research and initial visual inspection of the raw data. First, because previous research suggests that the first few years after parental divorce represents a period of acute change and adjustment (Hetherington & Kelly, 2002), we were interested in differentiating between short-term and long-term trajectories of conflict. Second, plotting the raw data revealed apparent linear change over the initial four waves of data collection (baseline, posttest, 3-month follow-up, 6-month follow-up) and a distinct pattern of linear change between the 6-month and six-year follow-up assessment periods.

Three-class solution of conflict trajectory profiles.

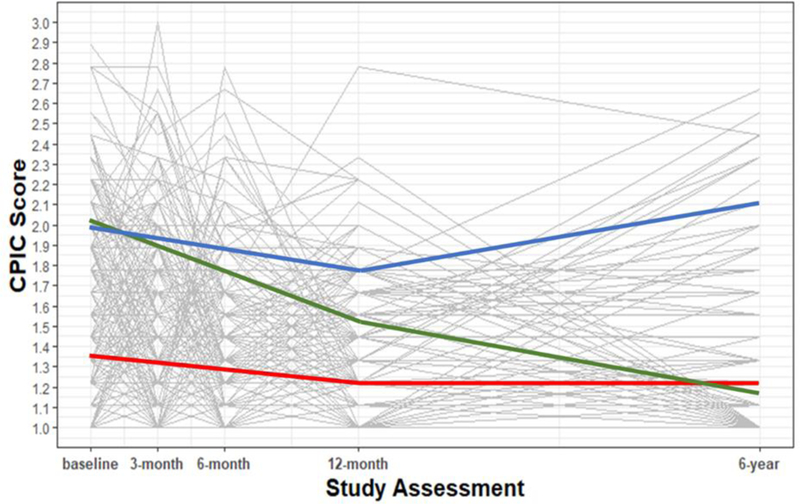

The three-class model was determined to be the best-fitting and most interpretable and useful model (see Table 2 for fit indices for all solutions). A four-class model was also considered based on fit statistics, but ultimately rejected due to two classes (one of which represented only 5% of the sample) having the same patterns of change (i.e., significant linear decline of both slopes), reducing the usefulness of separating them. See Figure 1 for a graphical representation of the three longitudinal trajectory profiles. The average trajectory of the largest class (n = 148, 62%) was characterized by a relatively low initial level of interparental conflict at baseline (g0n = 1.34, SE = .03, z = 42.51, p <.001), which declined over the initial period of 9 months (g1n = −0.25, SE = .04, z = −5.74, p <.001) and remained stable over the follow-up period of 6 years (g2n = −0.01, SE = .01, z = −1.38, p = .168). The next largest class (n = 71, 30%) had a relatively higher mean baseline value of interparental conflict (g0n = 2.01, SE = .10, z = 20.12, p <.001) that declined over initial period (g1n = −0.73, SE = .12, z = −5.98, p <.001) and then declined again over the follow-up period (g2n = −0.06, SE = .01, z = −6.06, p < .001). The smallest group (n = 21, 9%) also had a relatively higher mean baseline value of interparental conflict (g0n = 1.96, SE = .18, z = 10.83, p <.001), but there was no significant change over the initial period (g1n = −0.33, SE = .19, z = −1.70, p =.089) and an increase over the follow-up period (g2n = 0.07, SE = .02, z = 3.02, p =.003). The trajectories were labeled Low Decreasing, High Decreasing, and High Increasing.

Table 2.

Model Fit Information for 1-Class Baseline Piecewise Growth Model and 2, 3, and 4-Class Piecewise Growth Mixture Models

| Fit Statistic | 1-class Model | 2-class Model | 3-class Model | 4-class Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class Counts & Proportions | 1.0 | 154/86 (.36/.64) | 21/71/148 (.09/.29/.62) | 12/18/75/135 (.05/.08/.31/.56) |

| AIC | 898.401 | 920.758 | 852.994 | 813.139 |

| BIC | 933.208 | 948.603 | 894.761 | 868.829 |

| SABIC | 901.510 | 923.245 | 856.724 | 818.113 |

| Entropy | - | .779 | .829 | .824 |

| VLMR p-value | - | <.001 | .201 | .227 |

| BLRT p-value | - | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 |

Note. AIC = Akaike information criterion; BIC = Bayesian information criterion (Schwarz, 1978); SABIC = sample-size adjusted Bayesian information criterion (Sclove, 1987); VLMR = Vuong-Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio test (Lo et al., 2001); BLRT = bootstrapped likelihood ratio test (McLachlan & Peel, 2000).

Figure 1.

Estimated trajectories and observed individual values. CPIC = Children’s Perception of Interparental Conflict scale (Grych et al., 1992)

Aim 2: Examine Predictors of Group Membership and Group Differences among Trajectory Profiles

Predictors of group membership.

Results of multinomial regression analyses revealed no differences (χ2[2] = .80, p = .670) among the three trajectories of conflict in the proportion of families between the intervention groups (combined MP and MPCP2) and active control group (LC). Neither child age (χ2[2] = 1.05, p = .591) nor gender (χ2[2] = .16, p = .925) significantly predicted trajectory membership. There were no differences in likelihood of group membership based on the number of overnights the child spent with their father (χ2[2] = 1.95, p = .378), time since parental separation (χ2[2] = 2.53, p =. 282), or whether or not the child’s father moved out of the area following the divorce (χ2[2] = 2.21, p = .332) or remarried (χ2[2] = 2.24, p = .327). Finally, the extent to which mothers held a favorable view about the relationship between the child and their father marginally predicted group membership (χ2[2] = 4.86, p = .088). Mothers in the High Decreasing trajectory endorsed less favorable attitudes as compared to those in the Low Decreasing Trajectory (b = −0.05, p = .041, Exp(B) = .948, 95% CI = .902, .998).

Group differences among trajectory profiles.

See Table 3 for means and standard deviations for all dependent variables across the trajectories.

Table 3.

Means and Standard Deviations for Child Mental Health Outcomes by Conflict Trajectories

| Variable | Low Decreasing (n=148) | High Decreasing (n=71) | High Increasing (n=21) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Mother Report – Mental Health | ||||||

| Internalizing Problems – T1 | 56.20a | 9.05 | 59.31a | 9.99 | 58.90 | 11.06 |

| Externalizing Problems – T1 | 54.40 | 8.15 | 55.76 | 9.13 | 56.95 | 8.36 |

| Internalizing Problems – T5 | 51.11 | 9.58 | 53.81 | 8.42 | 55.31 | 9.87 |

| Externalizing Problems – T5 | 49.82 | 9.96 | 50.66 | 9.55 | 53.81 | 9.61 |

| Youth Report – Mental Health | ||||||

| Internalizing Problems – T1 | −.13a | .88 | .30a | .83 | −.07 | .94 |

| Externalizing Problems – T1 | −.20a | .85 | .43a,c | 1.17 | −.06c | .93 |

| Internalizing Problems – T5 | −.03 | .91 | -.01 | .96 | .20 | .86 |

| Externalizing Problems – T5 | −.05 | .92 | .02c | 1.10 | .30c | 1.18 |

| Youth Report - Risk Behaviors | ||||||

| Past Year Alcohol Use – T5 | 2.90 | 1.90 | 3.15 | 2.11 | 3.59 | 2.21 |

| Past Year Marijuana Use – T5 | 1.81a | 1.55 | 2.44a | 2.05 | 2.00 | 1.84 |

| Past Year # Sexual Partners – T5^ | .57a | .98 | .89a | 1.79 | .76 | .83 |

Note. T1 = baseline; T5 = six-year follow-up.

indicates that a negative binomial regression model was used for the count outcome of number of sexual partners.

significant mean differences between Low Decreasing and High Decreasing trajectories

significant mean differences between Low Decreasing and High Increasing trajectories

significant mean differences between High Decreasing and High Increasing trajectories

Mother-reported mental health problems.

At T1, mothers reported significantly higher child internalizing problems in the High Decreasing profile compared to the Low Decreasing profile (b = 3.14, p = 0.02). The High Increasing profile was not significantly different from High Decreasing (b = −0.52, p = .82) or the Low Decreasing (b = 2.63, p = .23) trajectories on T1 mother-reported internalizing problems. There were no significant differences in mother-reported externalizing problems at T1, nor in T5 mother-reported internalizing and externalizing problems.

Self-reported mental health problems.

At baseline, youth reported significantly higher internalizing problems in the High Decreasing profile compared to the Low Decreasing profile (b = 0.42, p < 0.001). The High Increasing profile was not significantly different from High Decreasing (b = −0.36, p = .10) or the Low Decreasing (b = 0.07, p = .74) trajectories on T1 self-reported internalizing problems. Youth also reported significantly higher baseline externalizing problems in the High Decreasing profile compared to the High Increasing profile (b = 0.50, p = 0.03) and the Low Decreasing profile (b = 0.62, p < 0.001). At six-year follow-up, youth in the High Increasing profile reported significantly higher externalizing problems, as compared to youth in the High Decreasing profile (b = 0.51, p = 0.05). The difference in means of the Low Decreasing vs. High Increasing (b = 0.38, p = .11) and vs. High Decreasing (b = −0.12, p = .42) trajectories were not significantly different. There were no significant differences in T5 self-reported internalizing problems.

Self-reported risk behaviors.

At T5, youth in the High Decreasing profile reported significantly higher past-year marijuana use (b = 0.69, p < 0.001) and number of sexual partners (b = 0.61, p = 0.04), as compared to youth in the Low Decreasing profile. The High Increasing profile was not significantly different from High Decreasing (b = −0.45, p = .33) or the Low Decreasing (b = .24, p = .58) trajectories on T5 marijuana use. Similarly, the High Increasing profile was not significantly different from High Decreasing (b = −0.10, p = .81) or the Low Decreasing (b = 0.51, p = .18) trajectories on T5 number of sexual partners. There were no significant differences among the trajectories on past year alcohol use.

Mental health and substance use disorders.

At T5, youth in the High Decreasing profile were significantly more likely to meet criteria for a mental health disorder (b = 0.98, p = .012), as compared to youth in the Low Decreasing profile. The odds ratio between the two trajectories was 2.66 (95% CI = 1.238, 5.726), indicating that the odds of being diagnosed with a mental health disorder was 2.66 times as likely in the High Decreasing profile as compared to the Low Decreasing profile. Examination of relative percentages indicated that 13% of youth in the Low Decreasing profile met diagnostic criteria for a mental health disorder compared to 27% in the High Decreasing profile. The youth in the High Decreasing trajectory had a range of mental health disorders, with the most common being: oppositional defiance disorder, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, and major depressive disorder. There were no statistically significant differences in diagnoses across the trajectories for substance use disorders.

Aim 3: Interaction Effects between Coping and Conflict Trajectory in the Prospective Prediction of Mental Health Problems and Risk Behaviors

See Table 4 for main effects of each coping subscale and significant coping by trajectory interaction effects for all dependent variables.

Table 4.

Main Effects of Coping Subscales and Interaction Effects of Trajectory by Coping Subscales on Six-Year Follow-Up (T5) Child Mental Health, Substance Use, And Risky Sexual Behavior Outcomes

| T5 outcome | Coping Subscale Main Effects | Coping X Trajectory Interaction Effects | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Avoidant | Positive Cognitive Restructuring | Coping Efficacy | Problem-focused | Coping Subscale | Trajectory Comparison | |||||||

| b | p | b | p | b | p | b | p | b | p | |||

| Externalizing Problems (youth report) | - | - | −0.12 | .002 | −0.51 | .009 | −0.06 | .092 | Avoidant Avoidant |

1 vs. 3 2 vs. 3 |

−0.42 −0.50 |

.050 .024 |

| Internalizing Problems (youth report) | −0.02 | .565 | −0.08 | .026 | −0.44 | .016 | - | - | PF | 2 vs. 1 | −0.16 | .026 |

| Externalizing Problems (mother report) | 0.48 | .184 | 0.00 | .999 | −0.51 | .759 | −0.32 | .306 | none | - | - | - |

| Internalizing Problems (mother report) | −0.01 | .982 | −0.61 | .066 | −3.15 | .057 | −0.63 | .050 | none | - | - | - |

| Alcohol Use (youth report) | −0.17 | .179 | −0.10 | .190 | −0.50 | .183 | −0.09 | .235 | none | - | - | - |

| Marijuana Use (youth report) | −0.05 | .631 | - | - | - | - | −0.07 | .330 | CE | 1 vs. 3 | 4.13 | .002 |

| CE | 2 vs. 3 | 4.64 | .001 | |||||||||

| PCR | 1 vs. 3 | 0.85 | .020 | |||||||||

| PCR | 2 vs. 3 | 0.81 | .032 | |||||||||

| Sexual Partners^ (youth report) | 0.02 | .778 | −0.13 | .050 | −0.89 | .032 | - | - | PF PF |

1 vs. 3 2 vs. 3 |

−0.56 −0.64 |

.038 .027 |

Note. Trajectory 1 = Low Decreasing, Trajectory 2 = High Decreasing, Trajectory 3 = High Increasing; PF = Problem-focused coping; PCR = Positive Cognitive Restructuring coping; CE = Coping Efficacy.

indicates that a negative binomial regression model was used for the count outcome of number of sexual partners. Bolded regression coefficients indicate statistical significance at p ≤ .05.

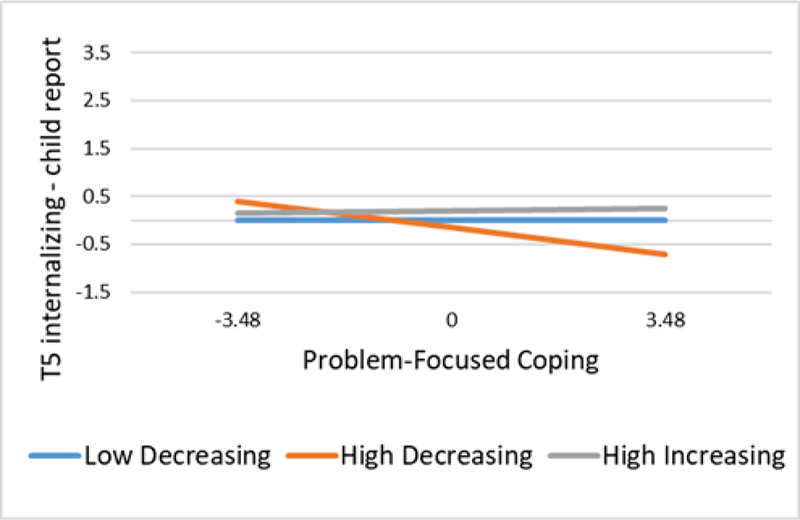

Problem-focused coping.

We found a significant problem-focused coping by trajectory profile interaction on youth-reported internalizing problems at T5 (see Figure 2). Pairwise comparisons indicated that the prospective association between problem-focused coping and youth reported internalizing problems significantly differed for youth in the High Decreasing trajectory relative to the Low Decreasing trajectory (b = −0.161, p = .026), controlling for T1 youth-reported internalizing problems. The association was not different for youth in the High Increasing as compared to either the High Decreasing or the Low Decreasing trajectory. Simple slope analyses indicated that the within-group slope for High Decreasing trajectory was significant and negative (b = −0.159, p = .008), indicating that higher levels of problem-focused coping were associated with lower levels of internalizing problems for these youth. There was also a significant problem-focused coping by trajectory profile interaction on youth-reported number of sexual partners at T5. Pairwise comparisons indicated that the prospective association between problem-focused coping and youth-reported risky sexual behavior significantly differed for youth in the High Increasing trajectory relative to both Low Decreasing (b = −0.557, p = .038) and High Decreasing (b = −0.636, p = .027). However, simple slope analyses indicated that the within-group slopes did not significantly differ from zero for any trajectory.

Figure 2.

Association between problem-focused coping on T5 (six-year follow-up) child reported internalizing problems as a function of conflict trajectory. Problem-focused coping is mean-centered and displayed range represents ± 2 standard deviations.

We also found a significant main effect of problem-focused coping on mother-reported internalizing problems (b = −0.627, p = .050), indicating that higher levels of problem-focused coping were associated with lower levels of child internalizing problems at T5 across the three trajectory trajectories.

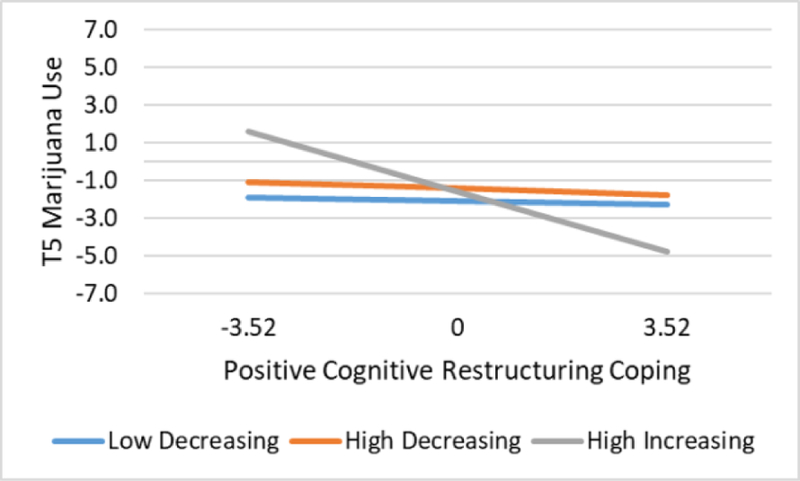

Positive cognitive restructuring coping.

We found a significant positive cognitive restructuring coping by trajectory interaction on T5 marijuana use (see Figure 3). Pairwise comparison tests indicated that the association was significantly different for youth in the High Increasing trajectory as compared to both the Low Decreasing (b = 0.848, p = .020) and compared to the High Decreasing trajectories (b = 0.810, p = .032). The Low Decreasing and High Decreasing trajectories were not significantly different. Simple slope analyses indicated that the within-group slope for High Increasing trajectory was significant and negative (b = - 0.907, p = .010), indicating that higher levels of positive cognitive restructuring coping were associated with lower levels of past year marijuana use.

Figure 3.

Association between positive cognitive restructuring coping on T5 (six-year follow-up) marijuana use as a function of conflict trajectory. Positive cognitive restructuring coping is mean-centered and displayed range represents ± 2 standard deviations.

We also found a significant main effect of positive cognitive restructuring coping on youth-reported internalizing problems (b = −0.078, p = .026), youth-reported externalizing problems (b = −0.117, p = .002), and number of sexual partners (b = −0.134, p = .050), indicating that higher levels of positive cognitive restructuring coping were associated with lower levels of self-reported youth mental health problems and risky sexual behavior at T5 across all trajectories. Results of regression diagnostics identified one potentially influential case for the analysis involving the number of sexual partners. When this analysis was re-run without the identified case, the main effect was no longer significant (b = −0.105, p = .110). Thus, this finding should be interpreted with caution.

Avoidant coping.

We found a significant avoidant coping by trajectory interaction on child-report externalizing problems at T5. Pairwise comparison tests indicated that the association significantly differed for youth in the High Increasing trajectory as compared to both the Low Decreasing (b = −0.415, p = .050) and High Decreasing trajectories (b = −0.499, p = .024). The Low Decreasing and High Decreasing trajectories were not significantly different. However, simple slope analyses indicated that the within-group slopes did not differ from zero for any trajectory, although the relation between avoidant coping and externalizing problems for the High Increasing trajectory was positive and marginal (b = .386, p = .063). There were no significant main effects of avoidant coping.

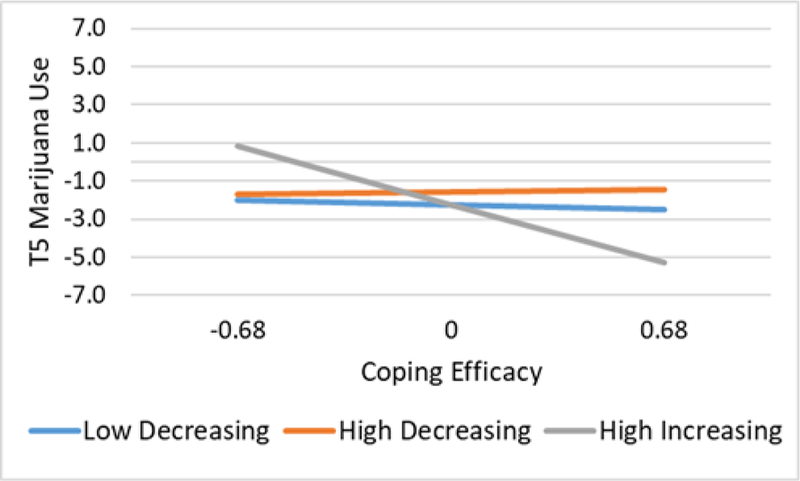

Coping efficacy.

We found a significant coping efficacy by trajectory interaction on T5 marijuana use (see Figure 4). Pairwise comparison tests indicated that the association was significantly different for youth in the High Increasing trajectory as compared to both the Low Decreasing (b = 4.128, p = .002) and High Decreasing trajectories (b = 4.644, p = .001). The Low Decreasing and High Decreasing trajectories were not significantly different. Simple slope analyses indicated that the within-group slope for High Increasing trajectory was significant and negative (b = −4.466, p < .001), indicating that higher levels of coping efficacy were associated with lower levels of past year marijuana use.

Figure 4.

Association between coping efficacy on T5 (six-year follow-up) marijuana use as a function of conflict trajectory. Coping efficacy is mean-centered and displayed range represents ± 2 standard deviations.

We also found a significant main effect of coping efficacy on youth-reported externalizing problems (b = −0.509, p = .009), internalizing problems (b = −0.443, p = .016), and number of sexual partners (b = −0.892, p = .032), indicating that higher levels of coping efficacy were associated with lower levels of self-reported youth mental health problems and risky sexual behavior at T5. When this analysis was re-run without the identified influential case on the outcome of number of sexual partners, the main effect was no longer significant (b = −0.378, p = .234). Thus, this finding should be interpreted with caution.

Discussion

It is fitting that this paper is in the special issue that honors Tom Dishion. Tom was a champion of longitudinal research that probed the pathways that lead to children’s psychopathology. He had a special interest in the measurement of constructs in our developmental theories and he sought to use new and more powerful measures of each of these constructs. Most of all, Tom was devoted to developing and testing theories that had a direct link to interventions to prevent the development of psychopathology. Although the specific population and constructs that are the focus of this paper were not the focus of Tom’s work, this study fits well with his distinguished body of work, which demonstrated the fruitfulness of this kind of rigorous, longitudinal research with its focus on improved methods of measurement and implications for improving the lives of children.

This study makes two noteworthy contributions to the literature on interparental conflict and youth’s coping in the context of parental divorce. First, to our knowledge, it is the first to identify distinct longitudinal trajectories of change in youth-reported interparental conflict over six years and demonstrate that two trajectories (high initial levels that decrease over time and high initial levels that increase over time) confer risk for mental health and substance use problems as compared to low initial conflict that decreases over time. Second, it is the first study to examine how trajectories of conflict interact with various aspects of youth’s coping to predict mental health, substance use, and high-risk sexual behavior outcomes six to eight years after the divorce. Some interaction effects emerged indicating that problem-focused coping, positive cognitive restructuring, and coping efficacy, may be particularly strongly prospectively related to problem outcomes (e.g., marijuana use) for children exposed to higher levels of conflict over time. However, other aspects of coping, mainly positive cognitive restructuring and coping efficacy, exerted prospective main effects on youth’s internalizing and externalizing problems. These findings extend prior research by identifying the long-term prospective effects of children’s coping styles and coping efficacy on mental health problems following parental divorce (Sandler et al., 2000). We discuss results from each study aim and contextualize the findings by discussing how the findings fit with prior literature and theoretical models on youth’s coping in the context of interparental conflict. We end with a discussion of the theoretical and intervention implications of the findings, as well as the limitations of the study and directions for future research.

Longitudinal Trajectories of Child Reported Interparental Conflict

We identified three distinct trajectories of conflict over the course of six to eight years after parental divorce. One group had the lowest relative level of baseline conflict, decreased over the course of the first year of the study and then remained low and stable at the six-year follow-up. We labeled this trajectory Low Decreasing. The size of this group (62%) aligns with previous literature suggesting that despite the ubiquitous nature of some level of conflict around the time of divorce, interparental conflict decreases over the first few years following parental divorce for most families (Hetherington & Kelly, 2002). The second largest group (30%) had a relatively high level of baseline conflict, but the conflict declined over the course of the first year of the study, and then declined even further at six-year follow-up. We labeled this trajectory of conflict High Decreasing. This group is distinguished from the former group because although interparental conflict declines for both trajectories and have a similar level of conflict at the six-year follow-up, the High Decreasing trajectory start out having higher levels of conflict and thus, children spend more time being exposed to a relatively high level of conflict. The smallest group (9%) also had a relatively high level of baseline conflict, but it did not significantly change over the course of the first year of the study, and then it increased at six-year follow-up. We labeled this trajectory of conflict High Increasing. This trajectory likely represents the families who are enmeshed in high levels of chronic conflict for many years following divorce/separation. Theoretically, the youth exposed to this trajectory of interparental conflict are likely to have the most severe consequences. The proportion of families displaying this longitudinal trajectory is smaller than the estimated number of families engaged in high levels of conflict following divorce in previous studies (e.g., 20–25% in Hetherington’s [2002] study and 15–20% in a study by Sbarra and Emery [2005]). However, these point-in-time estimates do not assess the trajectory of change in conflict over time, which the current study finds is important in understanding the long-term association between conflict and children’s post-divorce adjustment problems.

Relations between Theoretical Predictors and Longitudinal Trajectories of Change in Interparental Conflict

Based on previous research, we attempted to relate the conflict trajectories to theoretical predictors (i.e., information collected at baseline) that might help inform how we can prospectively predict which families will end up exhibiting the different trajectories of conflict. We tested variables that were both demonstrated in previous studies to be related to level of conflict and available to use in the dataset. Factors related to child demographics (i.e., age, gender) and post-divorce family circumstance (i.e., father relocation and remarriage, time since separation) were not related to membership in a conflict trajectory. Maternal attitudes toward the relationship between father and child was the only factor that marginally predicted membership in one group versus another. Families in which mothers held less favorable views about their child’s relationship with the father were more likely be in the High Decreasing versus Low Decreasing trajectory. To note, the group means in the High Increasing and High Decreasing trajectories were very similar (within .17 raw units on a scale with a range of 26); the lack of significant differences between the High Increasing and Low Decreasing trajectories is likely due to the small size of the High Increasing trajectory. To the extent that this effect is replicable, parental attitudes about the child’s relationship with the other parent may be a key factor in identifying families at high-risk for damaging trajectories of interparental conflict. Future research on parental attitudes about one another should incorporate new concepts being developed about the fundamental dynamics that characterize the conflict, such as entrenched interparental hatred (Smyth & Moloney, 2017, 2019)

Relations between Concurrent and Prospective Mental Health Problems and Risky Behaviors and Trajectories of Interparental Conflict

The three trajectories of interparental conflict differ in levels of youth’s baseline and six-year mental health and substance use problems. At baseline, there were significant differences among the trajectories in the level of internalizing problems, according to both mother- and self-report. Youth in the High Decreasing trajectory demonstrated higher levels of mother- and child-reported internalizing problems relative to the Low Decreasing trajectory. In addition, according to self-report only, youth in the High Decreasing trajectory had higher levels of externalizing problems relative to the Low Decreasing and High Increasing trajectories. The findings that the High Decreasing trajectory showed higher levels of child mental health problems than the Low Decreasing trajectory likely reflects the impact of their higher levels of conflict at baseline. The finding that the High Decreasing trajectory showed higher levels of externalizing than the High Increasing trajectory at baseline does not continue over the six years, as discussed below. This suggests that there may be other important contextual factors at play beyond exposure to interparental conflict. For example, the High Decreasing trajectory may be more prone to experience a higher number of non-conflict divorce-related stressors, highlighting the importance of future research to extend the investigation of contextual correlates of the different trajectories.

The trajectories were also useful in predicting group differences at the six-year follow-up. Youth in the High Decreasing trajectory demonstrated higher marijuana use and risky sexual behavior and were more likely to be diagnosed with a mental health disorder as compared to youth in the Low Decreasing trajectory (OR = 2.66). In terms of clinical significance, youth in the High Decreasing trajectory were more than twice as likely to have a diagnosable mental health disorder six years later as compared to youth in the Low Decreasing trajectory. With regard to relative percentages, 13% of youth in the Low Decreasing trajectory had a diagnosable mental health disorder according to either parent or self-report on the DISC at the six-year follow-up, compared to 24% and 27% of youth in the two high-conflict trajectories (High Increasing and High Decreasing, respectively). This is the first study we know of to identify the long-term consequences of exposure to post-divorce interparental conflict in terms of diagnosable mental disorders. Notably, at the six-year follow-up, the High Decreasing trajectory did not have higher levels of conflict than the Low Decreasing trajectory, indicating that the long-term problems experienced by children in the High Decreasing trajectory may reflect the persistent negative effects of earlier exposure to interparental conflict.

Interestingly, the differences in externalizing problems changed between baseline and six-year follow-up for the High Increasing and High Decreasing trajectories. At baseline, the High Decreasing trajectory had the highest level of externalizing problems, but at the six-year follow-up, the High Increasing trajectory demonstrated the highest level of externalizing problems, significantly higher than the High Decreasing trajectory. Similarly, although the youth in the High Increasing trajectory were indistinguishable from the Low Decreasing trajectory at baseline, higher rates of externalizing problems emerged in this trajectory at the six-year follow-up, potentially reflecting the cumulative effects of exposure to chronic conflict over an extended period of time.

Taken together, it appears that the youth in the two high conflict trajectories – regardless of whether it eventually declines or remains high – show deleterious effects on one or more measures of mental health, substance use, and risky behavior problems at the six-year follow-up. There is some evidence of more consistent adverse effects in the High-Decreasing trajectory than in the High-Increasing trajectory. However, the magnitude of the differences is quite modest. It is possible that there are important differences between the two trajectories in the pattern of conflict to which the children were exposed prior to the study period (i.e., prior to and immediately following separation), the nature and number of other divorce-related stressors that occurred prior to the baseline assessment, or both, that may explain the modest differences. Research that includes a larger trajectory of the High-Increasing families and assesses conflict and other stressors before and immediately after the separation is an important direction for future research.

Together the two high-risk trajectories include 39% of the sample as being at risk due to exposure to post-divorce interparental conflict, which is a considerably higher percentage of high conflict divorces as compared with previous point-in-time estimates (Sbarra & Emery, 2005; Hetherington & Kelly, 2002). These findings are consistent with decades of previous research on youth exposed to interparental conflict (see Rhoades, 2008 for a meta-analysis). However, this is the first study to demonstrate that trajectories of interparental conflict over time are associated with problem outcomes and that exposure to high interparental conflict is associated with higher prevalence of diagnosed mental disorder.

Prospective Relations of Coping with Problem Outcomes across Trajectories of Interparental Conflict