Abstract

Background:

In the presence of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) together with additional psychiatric diseases, the treatment process and prognosis of both ADHD and psychiatric comorbidity are adversely affected.

Aims:

The aim of this study is to compare the characteristics concerning suicidal behavior of the patients diagnosed with major depressive disorder either having (ADHD+) or not having (ADHD−) adult ADHD comorbidity and their responses to depression treatment.

Materials and Methods:

Ninety-six inpatients were included in the study. Sociodemographic data form, the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS), the Wender Utah Rating Scale (WURS), the Adult ADD/ADHD DSM IV-Based Diagnostic Screening and Rating Scale, and the Personal and Social Performance Scale (PSP) were applied to the cases.

Results:

HDRS scores were found to be significantly high (P < 0.000) in the ADHD+ group during admission and discharge. However, there was no difference found in terms of PSP scores (P = 0.46) during discharge. In the ADHD+ group, the depressive episode started at an earlier age (P < 0.011). The idea of suicide (P < 0.018) and suicidal attempts (P < 0.022) was found to be higher in this group compared to the ADHD− group. ADHD+ patients had more suicidal attempts requiring more medical intervention (P < 0.001).

Conclusion:

Depression starts at an early age in individuals with comorbid ADHD diagnosis, and the progress of the depression treatment changes negatively. This patient group is at greater risk in terms of suicidal behavior. Therefore, it should be considered by the clinicians that ADHD can associate with depression while making the follow-up plans for the cases diagnosed with depression.

Keywords: Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, comorbidity, depression, suicide

INTRODUCTION

Suicidal behavior is a serious cause of mortality and morbidity in terms of psychiatric diseases. According to the World Health Organization, 800,000 people die due to suicide every year around the world.[1] Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts not resulting in death cause various social and emotional problems. Moreover, they are the most important risk factors for the next suicide attempt and death resulting from suicide.[2] It has been reported that 90% of the completed suicide attempt cases are accompanied by a psychiatric disease and depressive disorders are observed at the highest level.[3]

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder with the symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity that is seen as of childhood.[4] In the significant number of cases, ADHD continues in adulthood as well. Its frequency has been reported to be approximately between 3% and 22% in adults.[5,6] ADHD disrupts the functionality of an individual in various fields such as academic, social, and business life.[7] It also increases the risk of psychiatric diseases to be accompanied.[8] In the presence of ADHD together with additional psychiatric diseases, the treatment process and prognosis of ADHD and psychiatric comorbidity are adversely affected.[9] Mood disorders, anxiety disorders, alcohol and substance addictions, and antisocial personality disorders are among the most common comorbid disorders in ADHD.[10]

In the studies conducted, it has been reported that depression is seen in 16%–31% in cases with adult ADHD[11] and it was accompanied by ADHD in 15% of cases with depression.[12] In adults with ADHD comorbidity, resistance to depression treatment develops and the longitudinal progress of both diseases is adversely affected.[13,14] In the literature review, it has been reported that the risk of suicide increased in children,[15] in university students,[16] and in young women,[17] having depression accompanied with ADHD, and the clinical progress of depression was adversely affected.[18] Review studies are also found to be consistent with these results.[19] Studies examining the relationship of suicide with depression accompanying ADHD in adults have been mostly carried out in young adults, and it has been suggested by researchers to investigate the association of ADHD and depression in older adults.[19,20,21,22]

The aim of this study is to compare the suicidal behavior, the onset age of depression, and the treatment responses of inpatients having depressive disorder and accompanied either with adult ADHD or not in the psychiatry department. Our hypothesis is as follows; depression starts at an earlier age in the adult depression patients with comorbid ADHD and these patients will have more suicide attempts (number of previous suicide attempts) and these will be more serious (requiring medical treatment). Moreover, the functionality will be lower and the severity of depression will be higher (depression scale scores) in depression patients with comorbid ADHD during discharge from the hospital.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects and assessments

This research was carried out within patients having the ages ranging from 18 to 65 years with the diagnosis of major depressive disorder (MDD) in the Psychiatry Department of Izmir Bozyaka Training and Research Hospital located in one of the major cities of our country between September 2015 and September 2017. A total of 106 patients with diagnosis of major depression were evaluated consecutively to be included in the study. Inpatient treatment decisions of the patients were given by other psychiatrists working in the institution that did not participate in the study. Complying with the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) criteria and the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) being over 16 points during hospitalization has been determined to be the criteria of the study. It has been specified that mental retardation, bipolar disorder, psychotic disorder, alcohol or substance addiction, history of significant head trauma, and being under psychostimulant treatment are the criteria for exclusion. According to these criteria, five patients were left out of the study because they have used a substance in the last 1 month, three patients were excluded since they had psychotic characteristics, and two patients were excluded as they have disagreed to participate in the study. In total, 96 patients were included in the study. Depression cases with and without diagnosis of adult ADHD were matched for age and sex. The approval which is in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration has been obtained from the Medical Ethics Committee of University of Health Sciences (2014-72-6, Clinical Trials.gov ID: NCT03721588), and written informed consents have been collected from the participants. All cases were interviewed with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I).[23] Other comorbid psychiatric disorders were excluded. The diagnosis of adult ADHD was made by two separate psychiatrists, both by clinical interview and by the Wender Utah Rating Scale (WURS) score (≥36). In the retrospective investigation of ADHD diagnosis, cases who got the score of 36 and above in the WURS have been included in the study. Cases diagnosed with ADHD clinically have been recorded in our ADHD clinic for follow-up.

In a review conducted by Impey and Heun, it has been reported that the investigation method of the suicidal behavior of the cases or the use of scale has no effect on the results of the research.[24] In this study, we examined the suicidal behaviors in a similar manner to the methods used in some previous studies.[20,25] In the sociodemographic data form, previous suicidal ideation (Have you ever thought about ending your life?/Yes or No), suicide attempt (Have you ever attempted suicide?/Yes or No), and number of suicide attempts have been recorded. In case of any previous suicidal attempts, sociodemographic data included the information about the medical treatment that has been required (hospitalization, being in an intensive care unit, having self-destructive behavior, suicide attempt causing disability, etc.).

Material

Sociodemographic data form

This form has been prepared by researchers. Clinical variables such as participants' age, gender, marital status, socioeconomic status, educational status (in years), previous psychiatric and medical history, family's psychiatric history, suicidal behavior characteristics' history, and onset age of depression have been included in this form.

Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition Axis I Disorders

This form, which was used to diagnose in the studies, has been developed by First et al.[23] Turkish validity and reliability studies have been carried out by Özkürkçügil et al.[26]

Hamilton Depression Rating Scale

This scale that has been developed by Hamilton[27] is used to measure the severity of depression and the severity changes of depression during follow-up. Turkish validity and reliability studies have been carried out.[28]

Turgay's Adult Attention Deficit/Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Scale

The Adult ADD/ADHD DSM IV-Based Diagnostic Screening and Rating Scale has been developed by Turgay in Canada.[29] The scale has been prepared to screen attention deficit hyperactivity and impulsivity symptoms in adults according to the DSM-IV criteria. The scale is a four-point Likert-type rating scale. It consists of three subsections: attention deficit section, hyperactivity/impulsivity section, and characteristics regarding ADD/ADHD. Turkish validity and reliability studies have been carried out by Günay et al.[30]

Wender Utah Rating Scale

This is a Likert-type self-report scale rated between 0 and 4, which consists of 25 questions, which evaluates childhood ADHD symptoms and is used to support the diagnosis of ADHD in adults. It has been developed by Ward et al.,[31] and the validity and reliability of Turkish adaptation have been carried out by Oncü et al.[32] As suggested by Öncü et al., in this study, values above 36 points have been accepted as a breakpoint with regard to ADHD.

Personal and Social Performance Scale

This is a Likert-type scale in which the level of functionality is determined with six-line evaluation in four dimensions evaluated by the interviewer.[33] The validity and reliability studies of the Turkish form have been carried out by Aydemir et al.[34] It is accepted that as the scale score increases, the patient's functionality elevates as well.

Statistical analysis

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) for Windows was used for statistical analysis The distribution characteristics of the variables have been evaluated using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Student's t-test has been used to compare normal distribution parameters, and the Mann–Whitney U-test has been used for abnormal distribution parameters. According to the ADHD comorbidity, suicide attempt has been compared with the Pearson's Chi-squared test. P < 0.05 has been considered to be statistically significant results.

RESULTS

The average age of the patients was 39.1 ± 10.4. Fifty-seven percent (n = 55) of all the patients were females. Thirty-one percent (n = 30) were single/never married, 53% (n = 49) were married/living with a spouse, and 16% (n = 17) were divorced or living apart. There was no statistically significant difference found between the MDD and ADHD comorbidities (ADHD+) and patients with only MDD (ADHD−) in terms of gender, age, marital status, and education. The sociodemographic data of the two groups are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of unipolar depressive patients with and without attention deficit hyperactivity disorder comorbidity

| ADHD+ (n=48) | ADHD− (n=48) | χ2 or F (P) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean±SD | 38.27±11.61 | 39.96±9.09 | 0.278 |

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Male | 20 (41.7) | 21 (43.8) | 0.363 |

| Female | 28 (58.3) | 27 (56.3) | |

| Education (years), mean±SD | 9.44±4.18 | 8.9±4.34 | 0.413 |

| Marital status, n (%) | |||

| Single | 13 (27.1) | 17 (35.4) | 0.363 |

| Married | 24 (50) | 25 (52.1) | |

| Widowed/separate | 11 (22.9) | 6 (12.5) |

P<0.05 was considered as statistically significant. ADHD+ – Depressive patients with ADHD comorbidity; ADHD− – Depressive patients without ADHD comorbidity; ADHD – Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; SD – Standard deviation

In the ADHD+ group, depression started at an earlier age than the ADHD− group (P = 0.011). The average HDRS scores during admission to the hospital and discharge from the hospital were significantly higher in the ADHD+ group (P < 0.000). Moreover, the average Personal and Social Performance Scale (PSP) scores of the ADHD+ group at admission to the hospital were lower than the ADHD− group, and there was a statistically significant difference between them (P = 0.002). There was no difference between the groups during their discharge with regard to PSP scores (P = 0.46) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of unipolar depressive patients with and without attention deficit hyperactivity disorder comorbidity

| Clinical variables | Mean±SD | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ADHD+ (n=48) | ADHD− (n=48) | ||

| Age of depression onset | 26.79±11.7 | 31.75±9.61 | 0.011* |

| A-ADHDS total score | 29.44±11.07 | 4.75±4.06 | 0.000** |

| A-ADHDS-1 number of criteria | 6.31±2.1 | 1.58±1.44 | 0.000** |

| A-ADHDS-1 score | 16.38±6.42 | 3.58±3.95 | 0.000** |

| A-ADHDS-2 number of criteria | 5.6±2.81 | 0.65±0.86 | 0.000** |

| A-ADHDS-2 score | 13.06±7.59 | 1.17±1.58 | 0.000** |

| A-ADHDS-3 total score | 45.94±22.8 | 12.04±10.39 | 0.000** |

| A-ADHDS total criteria | 12.31±3.64 | 2.23±1.69 | 0.000** |

| WURS total score | 55.6±16.8 | 22.15±10.63 | 0.000** |

| HDRS score (admission) | 31.28±5.56 | 25.73±6.94 | 0.000** |

| HDRS score (discharge) | 21.59±5.55 | 16.73±4.84 | 0.000** |

| PSP (admission) | 38.83±11.31 | 45.25±10.59 | 0.002** |

| PSP (discharge) | 68.5±14.19 | 73.48±8.26 | 0.46 |

*P<0.05, **P<0.001. ADHD+ – Depressive patients with ADHD comorbidity; ADHD− – Depressive patients without ADHD comorbidity; SD – Standard Deviation; A-ADHDS – Adult ADD/ADHD DSM IV Based Diagnostic Screening and Rating Scale; WURS – Wender Utah Rating Scale; HDRS – Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; PSP – Personal and Social Performance Scale; ADHD – Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

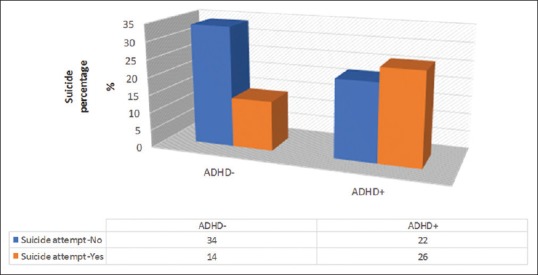

Suicidal ideation (P =0.018) and suicide attempts (P =0.013) throughout life were higher in the ADHD+ group than the ADHD− group. In the ADHD+ group, the rate of suicide attempts that require medical intervention was higher (P = 0.001). A comparison of the suicidal behavior characteristics of the ADHD+ and ADHD− groups is presented in Table 3, and it has been shown graphically whether the cases have attempted suicide according to ADHD comorbidity throughout their lives [Figure 1].

Table 3.

Comparison of suicidal behavior characteristics of ADHD+ and ADHD− patients (n=48)

| ADHD+, n (%) | ADHD−, n (%) | χ2 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suicidal thoughts (lifetime) | 41 (85.4) | 34 (64.6) | 5.556 | 0.018* |

| Suicide attempts (lifetime) | ||||

| Suicide attempt - no | 22 (39.3) | 34 (60.7) | 6.171 | 0.013* |

| Suicide attempt - yes | 26 (65) | 14 (35) | ||

| Suicide attempt (Attempts requiring medical attention) | 20 (41.7) | 4 (8.3) | 14.222 | 0.001** |

*P<0.05; **P<0.001. ADHD+ – Depressive patients with ADHD comorbidity; ADHD− – Depressive patients without ADHD comorbidity; ADHD – Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

Figure 1.

Comparison of suicide attempt rates of ADHD+ and ADHD- patients. ADHD - Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; ADHD+ - Depressive patients with ADHD comorbidity; ADHD- - Depressive patients without ADHD comorbidity

DISCUSSION

In this study, ADHD+ and ADHD− adults having depressive disorders have been compared in terms of age of depression onset, the severity of depression, levels of functionality, and suicidal behavior. In the ADHD+ group, depression has started at an earlier age; the severity of depression has been higher during discharge from the hospital; and suicidal ideation, the number of suicide attempts, and suicide attempts requiring medical intervention throughout their lives were found to be high.

Depressive disorder patients with ADHD comorbidity in our study had the first depression diagnosis at an early age. Similar results have been found by other researchers.[17,35] In ADHD, the reasons for an early onset of depression have not been fully clarified.[18,36,37] When the literature is examined, it has been stated that depression may start earlier due to shared genetic etiology and endophenotypes (such as reward dependence and emotion regulation disorder.) of ADHD and depression or psychosocial consequences caused by ADHD directly and that further investigations are required with regard to the relationship between these two disorders.

Another result of our study was that the discharge HDRS scores of the patients having depression with ADHD comorbidity were higher. Resistance to depression treatment has been reported in the association of ADHD and depression.[38,39] ADHD causes disruptions in the functionality of an individual in various areas starting from childhood.[40,41] It has also been reported that there is a decrease in social skills and self-esteem of adolescents with ADHD.[42] It has been reported that ADHD-specific characteristics such as low level of problem-solving skills, inconsistency in social relationships, inability to control responsibilities, and getting bored quickly from the routine work cause interpersonal problems, and this situation is among the social issues that lead to the development of resistance to depression.[18] It has been suggested that in the event of frequent recurrent depressive attacks, inability of remission, continuation of residual symptoms and inadequate response to classical therapies of cases with depression, a retrospective investigation of ADHD,[38,39] and treatment planning for ADHD should be made.[18,36,43] Despite all these data, researchers have noted that ADHD in adults is scarcely recognized and undertreated, and it is important to increase adult ADHD awareness among mental health-care personnel.[12]

Sobanski et al. reported that psychosocial functionality related to ADHD was primarily disrupted in many areas in adults with ADHD who were directed to the clinic.[44] It has been stated that individuals with ADHD have higher rates of psychiatric comorbidity than those without ADHD and they are diagnosed with more “present depression” and that they experience more disruption in terms of functionality and in psychosocial areas.[9,45,46] In our study which was found to be consistent with the literature, depressive individuals with ADHD who have been evaluated during hospitalization were found to have lower levels of individual and social functionality. Even though PSP scores of the ADHD+ group were lower than the ADHD− group during discharge from the hospital, this difference was not found significant.

As a result of our study, the rate of suicidal ideation throughout life and the number of suicide attempts were found to be higher in the ADHD+ group. As stated earlier, according to the literature, 90% of the cases who attempted suicide are accompanied by a psychiatric disorder and the depressive disorder is the most common one.[3] It has been reported that suicide attempts are related to depression duration or impulsivity.[43,47] The depression duration in depressive individuals with ADHD comorbidity prolongs.[19,21,22] In addition, in studies conducted only on individuals with ADHD,[48] it has been reported that the risk of committing suicide has increased even for the relatives of the patients without any disorder.[49] On the basis of ADHD, the clinic of depression may vary in such a way that causes the risk of suicide to increase. It has been suggested that health-care personnel should be careful for the increased risk of suicide in ADHD patients.[48,49] In addition, in the association of ADHD and depression, the number of suicidal behaviors that are serious enough to require medical care is also higher. This finding has also been reported by other researchers when literature is reviewed.[16,25,50] The results of our study in terms of suicidal behaviors are also consistent with the studies examining suicidal behavior[16,17,19,35,51] in younger population than the average age in our study (average age: 39.1 ± 10.4) and with the studies stating that ADHD increases the lifelong suicide risk.[49] In adults, suicide is more common in ADHD and MDD comorbidities, and suicidal attempts may lead to more dangerous consequences (such as being in the intensive care unit and causing disability).

CONCLUSION

In this study, adult ADHD diagnosis was examined by two researchers using clinical interviews and scales that questioned the presence of ADHD symptoms in childhood and adulthood. The suicide attempts and ADHD symptoms of the patients have been evaluated cross-sectionally, other potential confounding factors (such as social relationships and personality) that may cause suicidal ideation and behavior of the patients have not been taken into consideration. The long-term effect of ADHD associated with depression on suicidal ideation and behavior has not been studied. Another limitation is that the suicidal ideation and behaviors of the patients have been received by asking them directly. With the concern of social labeling, individuals may be prone to keep such thoughts and behaviors to themselves. It should also be noted that these results cannot be generalized to the entire population since there is no control group and the study is single-centered. However, we believe that our study will contribute to the suicide studies in the cases with ADHD and unipolar depression comorbidity in the middle-old age adult population and to the increased awareness of the mental health-care personnel in terms of ADHD.

As a result, retrospective and current ADHD symptoms of the patients diagnosed with the adult MDD should be investigated and treated, if any. They should be closely monitored for suicidal behavior. It is recommended that long-term follow-up studies in which ADHD's relationship with depression clinic and suicidal behavior and the effects of ADHD treatment on these parameters are investigated in the older adult population should be carried out.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. Public Health Action for the Prevention of Suicide. World Health Organization; 2013. [Last updated on 2018 Sep 10; Last accessed on 2018 Sep 30]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mental_health/suicide-prevention/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ribeiro JD, Franklin JC, Fox KR, Bentley KH, Kleiman EM, Chang BP, et al. Self-injurious thoughts and behaviors as risk factors for future suicide ideation, attempts, and death: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychol Med. 2016;46:225–36. doi: 10.1017/S0033291715001804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cavanagh JT, Carson AJ, Sharpe M, Lawrie SM. Psychological autopsy studies of suicide: A systematic review. Psychol Med. 2003;33:395–405. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702006943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. (DSM-5) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Faraone SV, Biederman J. What is the prevalence of adult ADHD? Results of a population screen of 966 adults. J Atten Disord. 2005;9:384–91. doi: 10.1177/1087054705281478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fayyad J, De Graaf R, Kessler R, Alonso J, Angermeyer M, Demyttenaere K, et al. Cross-national prevalence and correlates of adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;190:402–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.034389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harpin VA. The effect of ADHD on the life of an individual, their family, and community from preschool to adult life. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90(Suppl 1):i2–7. doi: 10.1136/adc.2004.059006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duran Ş, Fıstıkcı N, Keyvan A, Bilici M, Çalışkan M. ADHD in adult psychiatric outpatients: Prevalence and comorbidity. Turk Psikiyatri Derg. 2014;25:84–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ekinci S, Öncü B, Canat S. Adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: Comorbidity and functioning. Anadolu Psikiyatri Derg. 2011;12:185–1. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sobanski E. Psychiatric comorbidity in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006;256(Suppl 1):i26–31. doi: 10.1007/s00406-006-1004-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kessler RC, Adler L, Barkley R, Biederman J, Conners CK, Demler O, et al. The prevalence and correlates of adult ADHD in the United States: Results from the national comorbidity survey replication. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:716–23. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.4.716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fayyad J, Sampson NA, Hwang I, Adamowski T, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Al-Hamzawi A, et al. The descriptive epidemiology of DSM-IV adult ADHD in the World Health Organization world mental health surveys. Atten Defic Hyperact Disord. 2017;9:47–65. doi: 10.1007/s12402-016-0208-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alpert JE, Maddocks A, Nierenberg AA, O'Sullivan R, Pava JA, Worthington JJ, 3rd, et al. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in childhood among adults with major depression. Psychiatry Res. 1996;62:213–9. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(96)02912-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bond DJ, Hadjipavlou G, Lam RW, McIntyre RS, Beaulieu S, Schaffer A, et al. The Canadian network for mood and anxiety treatments (CANMAT) task force recommendations for the management of patients with mood disorders and comorbid attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2012;24:23–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Balazs J, Miklósi M, Keresztény A, Dallos G, Gádoros J. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and suicidality in a treatment naïve sample of children and adolescents. J Affect Disord. 2014;152-154:282–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patros CH, Hudec KL, Alderson RM, Kasper LJ, Davidson C, Wingate LR. Symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) moderate suicidal behaviors in college students with depressed mood. J Clin Psychol. 2013;69:980–93. doi: 10.1002/jclp.21994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Biederman J, Ball SW, Monuteaux MC, Mick E, Spencer TJ, McCreary M, et al. New insights into the comorbidity between ADHD and major depression in adolescent and young adult females. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47:426–34. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31816429d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tamam L, Demirkol ME. Adult attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder and mood disorders. Turkiye Klin J Psychiatry Spec Top. 2012;5:48–3. [Google Scholar]

- 19.James A, Lai FH, Dahl C. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and suicide: A review of possible associations. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2004;110:408–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2004.00384.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Agosti V, Chen Y, Levin FR. Does attention deficit hyperactivity disorder increase the risk of suicide attempts? J Affect Disord. 2011;133:595–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Furczyk K, Thome J. Adult ADHD and suicide. Atten Defic Hyperact Disord. 2014;6:153–8. doi: 10.1007/s12402-014-0150-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Balazs J, Kereszteny A. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and suicide: A systematic review. World J Psychiatry. 2017;7:44–59. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v7.i1.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JB. Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV Axis I Disorders. 1996 doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820080032005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Impey M, Heun R. Completed suicide, ideation and attempt in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2012;125:93–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01798.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bácskai E, Czobor P, Gerevich J. Trait aggression, depression and suicidal behavior in drug dependent patients with and without ADHD symptoms. Psychiatry Res. 2012;200:719–23. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Özkürkçügil A, Aydemir O, Yıldız M. Adaptation of the structured clinical interview for DSM-IV Axis I disorders (SCID-I) into Turkish and the study of reliability. Ilac Tedavi Derg. 1999;12:233–6. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Akdemir A, Örsel S, Daǧ I. Ark V. The validity, reliability and clinical use of the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) Psikiyatr Psikol Psikofarmakol Derg. 1996;4:251–9. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Canada: Diagnosis and Review Inventory Integrated Therapy Institute (unpublished scale) of Adult Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Based on DSM-IV. [Last updated on 2019 May 15; Last accessed on 2019 Jul 12]. Available from: http://www.psikiyatri.org.tr/uploadFiles/ERISKIN-DEBDEHB.doc .

- 30.Günay Ş, Savran C, Aksoy UM. The norm study, transliteral equivalence, validity, reliability of Adult Hyperactivity Scale in Turkish adult population. Türkiye'de Psikiyatri. 2006;8:98–107. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ward MF, Wender PH, Reimherr FW. The Wender Utah rating scale: An aid in the retrospective diagnosis of childhood attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:885–90. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.6.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oncü B, Olmez S, Sentürk V. Validity and reliability of the Turkish version of the Wender Utah rating scale for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults. Turk Psikiyatri Derg. 2005;16:252–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morosini PL, Magliano L, Brambilla L, Ugolini S, Pioli R. Development, reliability and acceptability of a new version of the DSM-IV Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS) to assess routine social functioning. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2000;101:323–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aydemir Ö, Üçok A, Danacı A, Canpolat T, Karadayı G, Emiroǧlu B, et al. The validation of Turkish version of Personal and Social Performance Scale (PSP) Bulletin of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2009;19:93–100. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chronis-Tuscano A, Molina BS, Pelham WE, Applegate B, Dahlke A, Overmyer M, et al. Very early predictors of adolescent depression and suicide attempts in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:1044–51. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McIntyre RS, Kennedy SH, Soczynska JK, Nguyen HT, Bilkey TS, Woldeyohannes HO, et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults with bipolar disorder or major depressive disorder: Results from the international mood disorders collaborative project. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;12 doi: 10.4088/PCC.09m00861gry. pii: PCC.09m00861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meinzer MC, Lewinsohn PM, Pettit JW, Seeley JR, Gau JM, Chronis-Tuscano A, et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adolescence predicts onset of major depressive disorder through early adulthood. Depress Anxiety. 2013;30:546–53. doi: 10.1002/da.22082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bron TI, Bijlenga D, Verduijn J, Penninx BW, Beekman AT, Kooij JJ. Prevalence of ADHD symptoms across clinical stages of major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord. 2016;197:29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.02.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McIntosh D, Kutcher S, Binder C, Levitt A, Fallu A, Rosenbluth M. Adult ADHD and comorbid depression: A consensus-derived diagnostic algorithm for ADHD. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2009;5:137–50. doi: 10.2147/ndt.s4720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saraçoǧlu GV, Doǧan S. Consequences of untreated attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Turkiye Klin J Psychiatry Spec Top. 2012;5:94–8. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barkley RA. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. In: Barkley RA, Mash E, editors. Child Psychopathology. 1st ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2003. pp. 75–3. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shaw-Zirt B, Popali-Lehane L, Chaplin W, Bergman A. Adjustment, social skills, and self-esteem in college students with symptoms of ADHD. J Atten Disord. 2005;8:109–20. doi: 10.1177/1087054705277775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brezo J, Paris J, Turecki G. Personality traits as correlates of suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and suicide completions: A systematic review. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;113:180–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00702.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sobanski E, Brüggemann D, Alm B, Kern S, Deschner M, Schubert T, et al. Psychiatric comorbidity and functional impairment in a clinically referred sample of adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2007;257:371–7. doi: 10.1007/s00406-007-0712-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Able SL, Johnston JA, Adler LA, Swindle RW. Functional and psychosocial impairment in adults with undiagnosed ADHD. Psychol Med. 2007;37:97–107. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706008713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Das D, Cherbuin N, Butterworth P, Anstey KJ, Easteal S. A population-based study of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms and associated impairment in middle-aged adults. PLoS One. 2012;7:e31500. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sokero TP, Melartin TK, Rytsälä HJ, Leskelä US, Lestelä-Mielonen PS, Isometsä ET. Prospective study of risk factors for attempted suicide among patients with DSM-IV major depressive disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;186:314–8. doi: 10.1192/bjp.186.4.314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stickley A, Koyanagi A, Ruchkin V, Kamio Y. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms and suicide ideation and attempts: Findings from the adult psychiatric morbidity survey 2007. J Affect Disord. 2016;189:321–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.09.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ljung T, Chen Q, Lichtenstein P, Larsson H. Common etiological factors of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and suicidal behavior: A population-based study in Sweden. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71:958–64. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Evren C, Umut G, Evren B. Relationship of self-mutilative behaviour with history of childhood trauma and adult ADHD symptoms in a sample of inpatients with alcohol use disorder. Atten Defic Hyperact Disord. 2017;9:231–8. doi: 10.1007/s12402-017-0228-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cho SC, Kim JW, Choi HJ, Kim BN, Shin MS, Lee JH, et al. Associations between symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, depression, and suicide in Korean female adolescents. Depress Anxiety. 2008;25:E142–6. doi: 10.1002/da.20399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]