ABSTRACT

The role of the gut microbiome in models of inflammatory and autoimmune disease is now well characterized. Renewed interest in the human microbiome and its metabolites, as well as notable advances in host mucosal immunology, has opened multiple avenues of research to potentially modulate inflammatory responses. The complexity and interdependence of these diet-microbe-metabolite-host interactions are rapidly being unraveled. Importantly, most of the progress in the field comes from new knowledge about the functional properties of these microorganisms in physiology and their effect in mucosal immunity and distal inflammation. This review summarizes the preclinical and clinical evidence on how dietary, probiotic, prebiotic, and microbiome based therapeutics affect our understanding of wellness and disease, particularly in autoimmunity.

Introduction, definitions, and nomenclature

Humans are a complex collection of mammalian and prokaryotic cells. Recent estimates suggest that the ratio of bacterial to human cells is approximately one to one.1 The term “microbiota” refers to the microbial flora, which represents symbiotic, commensal, and pathogenic microorganisms (also known as pathobionts2) harbored by humans. The microbiome represents the collective genomes of these microorganisms.3 4 Although a person’s microbiome is relatively stable and resilient over time, environmental factors that can alter the composition include diet,5 probiotics (which contain live beneficial bacteria),6 7 prebiotics (which contain supplements that promote the growth of specific bacteria),6 7 viruses,8 and drugs, particularly antibiotics.9

Before advances in DNA sequencing technology, the diversity of the human microbiome was greatly underappreciated. At least 80% of microorganisms could not be identified using standard culturing techniques.10 With the advent of high throughput DNA sequencing, bacteria and archaea are now identified on the basis on the 16 small ribosomal subunit RNA (16S rRNA), a gene that is distinctive of prokaryotic cells.11 The 16S rRNA subunit has highly conserved regions common to most bacteria, as well as hypervariable regions unique to each species of bacteria. This allows for sequencing (via universal polymerase chain reaction primers) and taxonomic identification of the bacteria present in a community without amplification of human DNA.12 13 14 The equivalent method in fungi uses the internal transcribed spacer (ITS), 18S rRNA, or 26S rRNA regions.15 Although the 16S sequencing technology can be used to profile a particular microbial community, it is limited in defining bacterial species and differentiating between commensal and pathogenic strains,16 particularly in the case of horizontal gene transfer whereby one bacterial species obtains virulence factors from another species in its environment, allowing it to trigger the onset of disease (for example, Bacteroides in pouchitis17).

The metagenomic approach, in which the combined genomes of a microbial community are studied in their entirety (including viruses and fungi), has allowed for a more comprehensive characterization of the human microbiome.18 It is complemented by metatranscriptomics, which defines the collection of genes expressed by a particular microbial community, and by metaproteomics and metabolomics, which define the proteins and metabolites (such as short and medium chain fatty acids) collectively produced (or metabolized) by the microorganisms (table 1).21 22 Whole genome shotgun sequencing is used to infer the functional or enzymatic capabilities of the identified microorganisms.20

Table 1.

Definitions of selected terms and nomenclature

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Archaea | A domain of prokaryotes, single celled microorganisms |

| Dysbiosis | Non-homeostatic imbalance of microbiota that is associated with disease states19 |

| Fecal microbiota transplant (FMT; fecal matter transplant; fecal transplant; bacteriotherapy) | Restoration of physiologic microbial community by means of transplanting microbiota via feces20 |

| Metabolomics | Collection of metabolites (eg, short and medium chain fatty acids) produced by particular microbial community21 22 |

| Metagenomics | Combined genomes of microbial community in its entirety (including viruses and fungi)18 |

| Metaproteomics | Collection of proteins expressed by particular microbial community21 22 |

| Metatranscriptomics | Collection of genes expressed by particular microbial community21 22 |

| Microbiome | Collective genomes of microbial flora harbored by humans3 4 |

| Microbiota | Symbiotic, commensal, and pathogenic microorganisms (microbial flora) harbored by humans3 4 |

| Multi-omics | Integration of big data from “omic” technologies such as microbiomics, metagenomics, metatranscriptomics, metaproteomics, and metabolomics23 |

| Pathobionts | Commensal bacteria with the potential to be pathogenic2 |

| Prebiotics | Supplements containing substances that promote growth of supposedly beneficial microorganisms6 7 |

| Probiotics | Supplements containing live microorganisms that can alter composition of microbiota and are supposed to provide health benefits to host6 7 |

This review summarizes current understanding of the biological roles that the microbiome plays in health and disease. It assesses the evidence linking alterations in human microbiome homeostasis (that is, dysbiosis19) to the development of autoimmune disease in humans and animal models. Although no guidelines are available, we also present a critical assessment of tested dietary interventions to ameliorate these disorders as well as data on pre/probiotics. Finally, we discuss novel concepts and ways of restoring a physiological microbial community by bacteriotherapy (that is, fecal microbiota transplant)24 and related approaches that can improve and even cure these conditions.

Sources and selection criteria

We used the following terms (in various combinations) to search peer reviewed journals in PubMed: “microbiome”, “microbiota”, “16S rRNA”, “18S rRNA”, “ITS”, “metagenomics”, “metabolomics”, “metabolites”, “short chain fatty acids”, “SCFA”, “medium chain fatty acids”, “MCFA”, “acetate”, “butyrate”, “propionate”, “hexanoate”, “dysbiosis”, “autoimmune disease”, “inflammatory bowel disease”, “IBD”, “ulcerative colitis”, “UC”, “Crohn’s disease”, “CD”, “inflammatory arthritis”, “rheumatoid arthritis”, “RA”, “spondyloarthritis”, “SpA”, “psoriasis”, “psoriatic arthritis”, “PsA”, “ankylosing spondylitis”, “AS”, “multiple sclerosis”, “MS”, “animal model”, “mouse model”, “IL-1 receptor antagonist knockout mice”, “IL1rn−/− mice”, “K/BxN mice”, “SKG mice”, “DBA1 mice”, “collagen-induced arthritis”, “CIA mice”, “ANKENT mice”, “HLA-B27 rats”, “Th1”, “Th17”, “T-regulatory cells”, “Tregs”, “HLA-B27 transgenic rats”, “experimental autoimmune encephalitis”, “EAE mice”, “germ-free”, “antibiotics”, “gut-brain axis”, “gut-joint axis”, “immune system”, “Faecalibacterium prausnitzii”, “pathobionts”, “diet”, “Mediterranean diet”, “polyunsaturated oils”, “red meat”, “fish”, “fish oil”, “alcohol”, “carbohydrates”, “fiber”, “fat”, “vegan”, “carnivore”, “weight-loss”, “vitamins”, “gluten”, “probiotics”, “prebiotics”, “dietary supplements”, “bacteriotherapy”, “fecal microbiota transplant”, “FMT”, “exclusive enteral nutrition”, “EEN”, “Lactobacillus rhamnosus”, “Bifidobacterium”, “lactulose”, “Lactobacillus casei”, “Clostridium difficile infection”, “Bacteroides fragilis”, “therapy”, and “pharmaceutical”. We put no restrictions on dates. We also reviewed the reference sections of review articles for additional relevant studies. We obtained and critically evaluated data from various types of studies, including prospective, cross sectional, case-control, observational, and population based studies; open label, placebo controlled, and randomized controlled trials; and meta-analyses. We excluded case reports and case series. Whenever possible, key findings and study limitations are described.

Microbiome and its metabolites in health and disease

The microbiome serves many important functions in healthy people. It confers protection from pathogenic organisms that cause infection; facilitates digestion of complex plant carbohydrates into short chain fatty acids (SCFAs)—an energy source for gut epithelial cells, also serving an anti-inflammatory function by inhibiting histone deacetylases in regulatory T cells (Tregs) through G-protein coupled receptors (GPRs)25; synthesizes essential vitamins and amino acids; regulates fat metabolism26 27; produces small molecules that interact with the host environment28; and shapes the development of the immune system.29 For example, non-ribosomal peptide synthetase gene clusters, which have been exclusively identified in gut associated bacteria, produce small molecule dipeptide aldehydes, some of which act as protease inhibitors of cathepsins known to be important in antigen processing and presentation.28 30 Other small molecules include N-acyl amides, which interact with GPRs,31 and glycyl radical enzymes such as propanediol dehydratase (PduC), which correlates with epithelial adhesion and cellular invasion, using fucose for fermentation and metabolism.32 33 Furthermore, recent studies have shown that the adhesion of certain microbes (for example, segmented filamentous bacteria, Citrobacter rodentium, and Escherichia coli O157) to intestinal epithelial cells is necessary to trigger a T helper 17 (Th17) cell response.34

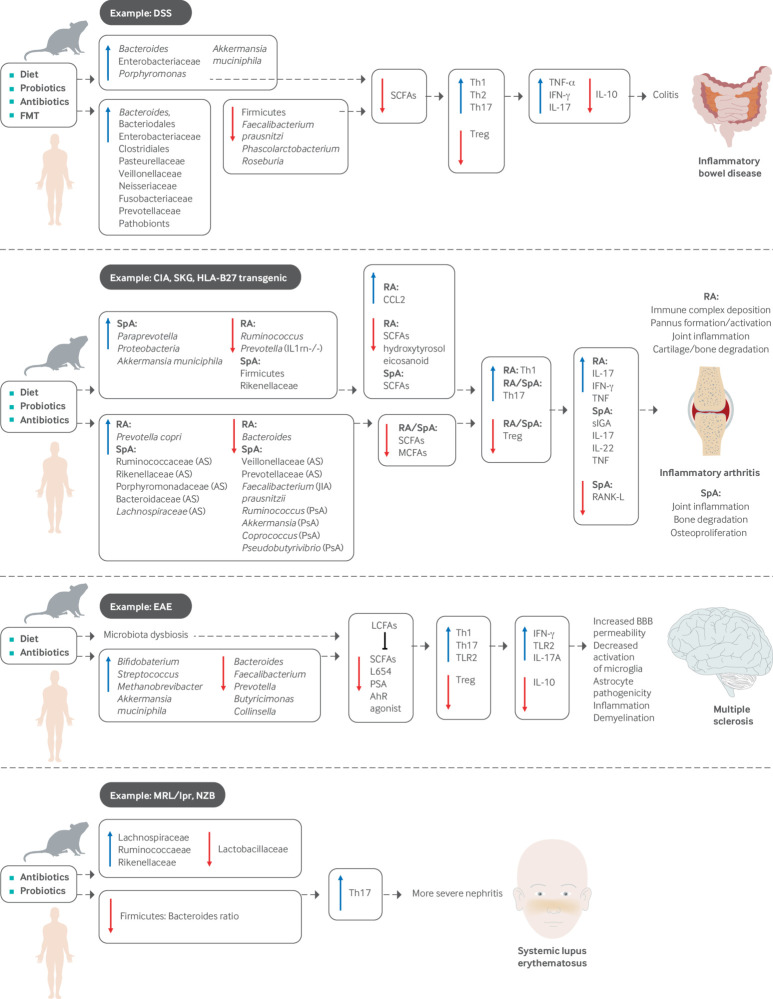

Microbial composition and colonization are, in turn, influenced by factors such as the neonatal mode of delivery, breast feeding, diet, treatment with antibiotics, and environmental exposures early in life.7 A dysbiotic state can lead to dysregulation of the various functions listed above, which can in turn contribute to the development of autoimmune conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), systemic inflammatory arthritis, multiple sclerosis, and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Available data are summarized in figure 1 and discussed in detail below.

Fig 1.

Influence of microbiome on metabolite production, immunomodulation, and development of systemic inflammatory disease. Accumulated evidence of microbiome and its metabolites in human autoimmune disease and animal models, including inflammatory bowel disease, inflammatory arthritis, multiple sclerosis, and systemic lupus erythematosus

Inflammatory bowel disease

Two major clinical phenotypes of IBD exist: ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Evidence for the importance of microbiota in disease pathogenesis comes from observations that colitis is significantly attenuated or absent in germ-free animals and those treated with antibiotics.35 36 37 Conversely, Bacteroides, Enterobacteriaceae, Porphyromonas, Akkermansia muciniphila, and Clostridium ramosum are enriched in several animal models of IBD and are associated with higher levels of inflammation.37 In humans, there is an overall trend toward lower biodiversity, increased abundance of Bacteroides and Enterobacteriaceae, and decreased abundance of Firmicutes in people with IBD compared with controls.38 39

Studies note a reduction of certain commensal microbes in IBD, particularly SCFA producers. These include Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Leuconostocaceae, Odoribacter splanchnius, Phascolarctobacterium, and Roseburia.40 F prausnitzii and Roseburia hominis both produce butyrate, which is known to induce the differentiation of Treg via the GPR43 receptor.6 41 Both taxa inversely correlate with disease activity of ulcerative colitis.41 Furthermore, reduction of F prausnitzii has been linked to postoperative recurrence of Crohn’s disease, and its administration in mouse models reduces gut inflammation.42 Phascolarctobacterium produces propionate in the presence of Paraprevotella, which also induces the production of Tregs.6 43 At the same time, several pathobionts are enhanced in IBD, including Escherichia coli, Shigella, Rhodococcus, Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, Prevotellaceae, Clostridium difficile, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Proteus mirabilis, and Helicobacter hepaticus.44 This dysbiotic shift in favor of pathobionts is thought to contribute to perturbations in the immune function of lamina propria cells, ultimately resulting in inflammation and progression to disease.45

Similarly, a microbiome survey of patients with new onset, treatment-naive Crohn’s disease showed that Enterobacteriaceae, Bacteroidales, Clostridiales, Pasteurellaceae, Veillonellaceae, Neisseriaceae, and Fusobacteriaceae positively correlated with disease, whereas Lachnospiraceae, Ruminococcaceae, Bacteroides, Faecalibacterium, Roseburia, Blautia, Ruminococcus, and Coprococcus negatively correlated with disease in biopsy samples from the ileum and rectum.46 Exposure to antibiotics further amplified the microbial dysbiosis. Interestingly, some of these differences were not observed in stool samples collected at the time of diagnosis, suggesting that the predictive power differs according to sample size and that predictive accuracy of disease pathogenesis and progression can potentially be improved by combining sampling strategies with clinical information.46

A novel approach to determine specific bacteria that affect susceptibility to disease has been to identify IgA coated bacteria. The presumption is that taxa coated with high concentrations of IgA correlate with a higher inflammatory response and are predictive of disease state. This technique, termed IgA-Seq, has been accomplished through a combination of flow cytometry based bacterial sorting and 16S rRNA gene sequencing.47 One of the first studies to use this approach showed that colonization of germ-free mice with human IBD intestinal microbiota characterized by high levels of IgA coating induced more severe forms of colitis than did colonization with microbiota characterized by low levels of IgA coating.47 Another more recent study showed that people with Crohn’s disease and associated peripheral spondyloarthritis were enriched in E coli coated with IgA compared with those without peripheral spondyloarthritis.48 Furthermore, colonization of wild-type, germ-free mice with isolates of this IgA coated E coli induced a Th17 response that was dependent on the presence of the pduC gene.48 Although still in its infancy, this technique may be important in the identification of potential pathobionts, which has direct implications for disease stratification and treatment.

Systemic inflammatory arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis—animal studies

Several animal models of inflammatory arthritis resembling human rheumatoid arthritis have shown a relation between the microbiome and development of disease. For instance, interleukin 1 receptor antagonist knockout (IL1rn−/−) mice spontaneously develop a T cell mediated arthritis that is dependent on toll-like receptor (TLR) activation by microbial flora. Whereas the arthritis phenotype is prevented when mice are maintained under germ-free conditions, advanced inflammation is induced by recolonization with indigenous Lactobacillus bifidus.49 IL1rn−/− mice show gut dysbiosis characterized by lower microbial richness (number of taxa present) and diversity (how different taxa are from one another), mainly driven by a decrease in Ruminococcus and Prevotella genera.50

K/BxN T cell receptor transgenic mice develop inflammatory arthritis mediated by T cell recognition and production of antibody against glucose-6-phosphate isomerase, a ubiquitous self antigen.51 Once again, arthritis is mitigated when animals are raised in a germ-free environment or treated from birth with vancomycin or ampicillin but occurs with the reintroduction of segmented filamentous bacteria.52

Finally, a more recent study of DBA1 mice, in which arthritis can be induced with the introduction of high quality collagen, showed that animals raised in germ-free conditions and subsequently colonized with microbiota from collagen induced arthritis (CIA) susceptible mice were more prone to develop inflammatory arthritis than were animals colonized with microbiota from CIA resistant mice.53 Interestingly, administration of SCFAs acetate, propionate, and butyrate to CIA and K/BxN mice had opposite effects on disease severity, both clinically and histologically, with phenotype abrogation in CIA mice and aggravation of arthritis in K/BxN mice.54

Rheumatoid arthritis—human studies

Microbiome involvement has also been shown in human studies of rheumatoid arthritis. In the gut, patients with new onset rheumatoid arthritis (NORA) are enriched in Prevotella copri at the expense of Bacteroides species.55 The abundance of P copri is also lower in people with DRB1 shared epitope alleles that confer an enhanced risk for disease development.55 Analysis of NORA metagenomes shows a reduction of genes encoding vitamin and purine metabolic enzymes (including those responsible for tetrahydrofolate biosynthesis important for methotrexate metabolism) and an increase in cysteine metabolic enzymes.55 Furthermore, inoculation of germ-free BALB/c ZAP-70W163C mutant (SKG) mice with fecal samples from rheumatoid arthritis patients that were dominated by P copri caused the development of severe arthritis in a Th17 dependent manner,56 although the SKG model is now considered to be more representative of spondyloarthritis than of rheumatoid arthritis.

Spondyloarthritis—animal studies

The intestinal microbiome likewise contributes to animal models of spondyloarthritis, a group of inflammatory conditions with shared features of axial skeleton arthritis, enthesitis, uveitis, colitis, dermatologic involvement, and association with the HLA-B27 allele. ANKylosing ENThesopathy (ANKENT) mice spontaneously develop progressive enthesitis and ankylosis of the tarsal joints resembling human ankylosing spondylitis,57 but they fail to do so when raised in germ-free conditions.58 However, enthesitis and ankylosis ensue when these animals are colonized with commensal intestinal bacteria.59 Similarly, SKG mice develop a chronic autoimmune arthritis due to a single point mutation in ZAP-70, a T cell signal transduction molecule,60 which is prevented by rearing animals in germ-free conditions (despite ongoing production of autoimmune T cells) or treatment with antifungals. Arthritis is provoked in germ-free mice by the injection of the fungal β-glucans zymosan, curdlan, or laminarin.61 Finally, the HLA-B27 transgenic rat model of spondyloarthritis that maintains multiple copies of HLA-B27 and human β2-microglobulin transgenes remains healthy when reared in a germ-free environment but develops peripheral arthritis as well as intestinal inflammation with the introduction of commensal intestinal bacteria.62 These transgenic animals have an intestinal dysbiosis marked by higher abundance of Paraprevotella and lower abundance of Rikenellaceae.63 Furthermore, there is evidence of an age dependent progressive dysbiosis associated with a reduction of Firmicutes and concomitant increase of Proteobacteria and Akkermansia municiphila, as well as a higher frequency of IgA coated bacteria. These perturbations are associated with enhanced expression of Th1 and Th17 cytokines, expansion of colonic Th17 cells, dysregulation of antimicrobial peptide expression, and up-regulation of bacterial specific IgA.64 HLA-B27 expression in these animals has a significant effect on both host and microbial metabolites as early as 6 weeks of age. Of particular interest is the fact that treatment with the SCFA propionate attenuates the development of arthritis.65

Spondyloarthritis—human studies

In human studies, patients with ankylosing spondylitis have been shown to have a distinct gut microbial signature compared with healthy people, with higher abundance of Lachnospiraceae, Ruminococcaceae, Rikenellaceae, Porphyromonadaceae, and Bacteroidaceae, and lower abundance of Veillonellaceae and Prevotellaceae.66 In pediatric enthesitis related arthritis, a type of juvenile spondyloarthritis, there is decreased abundance of intestinal F prausnitzii (similar to IBD),67 and multi-omics analysis shows lower functional metabolic potential.68 The intestinal microbiome is also altered in psoriatic arthritis, in which there is overall decreased diversity marked by lower abundance of Coprococcus, Akkermansia, Ruminococcus, and Pseudobutyrivibrio, which correlates with higher concentrations of secretory IgA and lower concentrations of receptor activator of nuclear factor κ-B ligand as well as reduced concentrations of the medium chain fatty acids (MCFAs) hexanoate and heptanoate.69 Interestingly, Akkermansia and Ruminococcus are both mucin degrading intestinal bacteria that produce SCFAs and are important for intestinal homeostasis.69

Multiple sclerosis

Multiple sclerosis is a chronic autoimmune disorder caused by demyelination of the central nervous system (CNS). Its course is highly variable, although many patients develop progressive irreversible neurologic disability.70 Several experiments in animal models of multiple sclerosis, called experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), imply that intestinal microorganisms contribute to disease pathogenesis.25 71 EAE is induced by the injection of a myelin protein with a bacterial adjuvant, which acts as a self antigen, promotes Th1 and Th17 responses, and results in neuron demyelination.72 Mice maintained in germ-free or pathogen-free environments are resistant to the development of EAE, produce lower concentrations of the inflammatory cytokines interferon-γ and interleukin 17A, and up-regulate the production of Tregs.73 74 Similar to other autoimmunity models, recolonization with conventional commensal microbiota induces the development of EAE in a Th17 dependent manner.74 75 Moreover, administration of antibiotics ameliorates EAE and down-regulates the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines as well as systemic Th17 cells.76

Intestinal microbiota are involved in many CNS functions—regulating blood-brain barrier permeability, activating microglia, reducing astrocyte pathogenesis, and expressing genes necessary for myelination.72 One recent study of piglets even showed that certain gut microbiota may be predictive of neurometabolite concentrations.77 In humans, 16S sequencing studies have shown a reduction in the abundance of Bacteroides, Faecalibacterium, Prevotella, Butyricimonas, and Collinsella, with enrichment of Bifidobaterium, Streptococcus, Methanobrevibacter, and Akkermansia muciniphila.72

Several taxa that are reduced in multiple sclerosis produce the SCFA butyrate, which has been implicated in the up-regulation of Tregs (as mentioned above), maintenance of blood-brain barrier integrity, and modulation of microglia activity.72 The introduction of long chain fatty acids into animal models exacerbates EAE by decreasing the amount of intestinal SCFAs and up-regulating the Th1/Th17 cell populations in the small intestine. In contrast, treatment with SCFAs, particularly propionate, ameliorates EAE via up-regulation of Tregs and interleukin 10, an anti-inflammatory cytokine.78 Concentrations of lipid 654, a TLR2 agonist produced by Bacteroidetes, is lower in people with multiple sclerosis.79

Although the role of TLR2 is controversial in human and animal models of multiple sclerosis, up-regulation of TLR2 mRNA expression is noted in the spinal cord of EAE mice.80 Furthermore, administration of lipid 654 results in TLR2 tolerance and ameliorates EAE.81 Polysaccharide A produced by Bacteroides fragilis promotes Tregs and protects against CNS inflammation and demyelination in the EAE model.82 Dietary tryptophan is metabolized by intestinal microbiota into aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonists, which limit CNS inflammation by acting on astrocytes and mitigates EAE in animals. Importantly, concentrations of aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonists are significantly lower in patients with multiple sclerosis than in controls.83

Systemic lupus erythematosus

SLE is a heterogeneous chronic inflammatory disease that can affect virtually every organ and varies between patients. It is driven by the production of autoantibodies leading to the formation of antigen-antibody immune complexes. Similar to other autoimmune conditions, when lupus prone New Zealand Black (NZB) mice were reared in a germ-free environment, they had lower rates and reduced severity of renal disease.84

In contrast, lupus prone MRL/Mp-Faslpr (MRL/lpr) mice reared in a germ-free environment had lower rates of nephritis only when they were fed an ultrafiltered antigen-free diet.85 A recent study characterized the intestinal microbiota of MRL/lpr mice, showing enrichment in Lachnospiraceae, Ruminococcaceae, and Rikenellaceae, with concomitant reduction in Lactobacillaceae compared with control MRL/Mp mice. Interestingly, exposure to retinoic acid restored Lactobacillaceae abundance, which correlated with an improved clinical phenotype.86 Human studies are sparse, but two investigations in Spanish and Chinese cohorts showed a decreased Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio in patients with SLE compared with healthy controls.87 88 Furthermore, in vitro cultures of isolated fecal microbiota from patients with SLE promoted Th17 differentiation.89

Dietary studies in human IBD and autoimmune arthritis: clinical evidence

Given the strong correlation between the gut microbiome and human health, it is plausible that factors affecting the microbial composition can be leveraged to indirectly modulate inflammatory disease. Among them, diet has been one of the most extensively studied owing to its amenability to modification and relatively safe profile, as well patients’ predisposition to try therapies that are perceived as more “natural.” Although the effect of dietary interventions in human health has been studied for centuries (take the Hippocratic phrase “all disease begins in the gut”), only recently have we begun to understand how changes in nutrient intake affect intestinal bacterial composition.

A pioneering study compared the effect of randomizing 10 healthy people to either a high fat/low fiber diet or a low fat/high fiber diet on gut microbiome composition in 10 healthy people who were insulated for 10 days.90 Although changes in bacterial diversity and compositionwere significant and occurred quickly (within the first day) after the dietary intervention, the magnitude of the perturbation was both low and insufficient to shift the microbiome of a participant into a different configuration, with samples clustering according to participants rather than diet.

Another randomized dietary intervention study compared two different diets in 11 healthy volunteers who followed two different diets for four days: one based exclusively on animal products (composed primarily of meats, eggs, and cheese) and the other based on plant products (enriched in grains, legumes, fruits, and vegetables).5 Each diet resulted in microbial changes consistent with differences in the microbiome of carnivorous and herbivorous mammals,91 with the animal based diet enriched in protein degradation whereas the plant based diet increased bacterial functions related to carbohydrate fermentation. Importantly, these differences at the community level were also reflected in significant changes in bacterial gene expression. Despite marked inter-individual baseline differences, all samples clustered by diet rather than by participant at the end of the intervention. In contrast to these and other studies of high fat versus low fat diets, the literature is less abundant on how specific dietary components might interact with the microbiome to induce host responses. Among these, a recent randomized crossover study showed how glycemic response to two single week dietary interventions based on consumption of white bread or sourdough leavened wholegrain bread was determined by pre-intervention microbiome composition.92

The mechanisms linking diet, microbiome composition, and host function are still being elucidated. Preference for different types of nutrients is one possible route through which dietary interventions modify the microbiome and, subsequently, host physiology. Evidence from studies of human populations with different diets (particularly Western versus agrarian/traditional diets) support this hypothesis, with an enrichment of Bacteroides in protein rich diets in contrast to Prevotella in carbohydrate based diets.93 94 Luminal pH, which varies naturally along the gastrointestinal tract,95 can also modulate the gut microbiome composition and, concomitantly, be altered by bacterial byproducts.

As discussed, SCFAs are a final product of bacterial fiber fermentation, which can modify intestinal pH. Vegans, for instance, have lower intestinal pH than omnivores.96 Diets high in fiber benefit the growth of those bacteria capable of fermenting dietary fibers,97 which can result in the inhibition of Th2 cell differentiation.98 These dietary derived SCFAs act as important immune modulators, as described before. Butyrate, an important SCFA involved in various host immune responses, provides energy to enterocytes and can improve barrier function.99 As discussed, it can also induce the differentiation of intestinal Tregs through the expression of FoxP3.100 Importantly, as in the case of EAE and CIA amelioration, the effect of SCFAs can happen at other distal sites, as SCFAs produced in the gut can also suppress inflammation in the lung.98

Dietary studies in IBD

Various dietary studies in IBD have shown a beneficial, if only transitory, effect in patients (supplementary table A). A lower likelihood of relapse in patients with ulcerative colitis was observed in a study of a low sulfur diet, which is known to decrease H2S production, improving epithelial permeability and enhancing utilization of butyrate by colonocytes.101 Diets with complex carbohydrates that remove the use of simple sugars have also shown clinical benefits in pediatric Crohn’s disease.102 103 Finally, exclusive enteral nutrition (EEN) can induce remission of Crohn’s disease in pediatric populations.104 This type of therapy consists of restricted use of liquid feeding with an elemental or polymeric formula for six to eight weeks. EEN can reduce pro-inflammatory acetic acid and increase the concentration of butyric acid, which has anti-inflammatory properties.105 Despite its success in children, EEN is not easily applicable to adult populations owing to its unpleasant taste. However, promising results have been reported in patients with newly diagnosed Crohn’s disease who can adhere to this type of diet.106 Unfortunately, many of these studies in IBD provide limited, if any, evidence on how the microbiome changes in response to the dietary intervention, so our understanding of bacterial mechanisms that mediate their benefits is limited.

Dietary studies in rheumatoid arthritis

Over the past decade, a large body of evidence has characterized the mechanisms by which nutrients and specific foods could alter the gut microbial ecology and the downstream production of immune modulating metabolites, ultimately orchestrating local and distal autoimmune phenotypes. Concomitantly, a variety of clinical and epidemiologic studies have looked at the potential beneficial effects of well defined diets on inflammatory arthritis and related disorders.107 108 109 110 Included among those with established associations and/or demonstrated clinical efficacy are the Mediterranean diet, increased fish and olive oil intake, and decreased red meat consumption (supplementary table A).

Mediterranean diet

A typical Mediterranean diet consists of consumption of high quantities of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, fish, and olive oil, with low amounts of red meat (and a moderate amount of alcohol). Strong evidence from multiple randomized clinical trials (RCTs) shows that this dietary intervention has positive outcomes on inflammation and physical function among patients with existing rheumatoid arthritis compared with a Western diet.111 112 In contrast, data derived from the Nurses’ Health Studies showed no significant association of a Mediterranean diet with the risk of women developing rheumatoid arthritis.113 However, this prospective analysis showed modest associations between increased legume intake and higher risk of developing rheumatoid arthritis and between long term moderate alcohol drinking and reduced risk of incident rheumatoid arthritis.114 These results have not always been confirmed, likely because individual foods/nutrients confer only modest beneficial effects so any protective effects would be observed only when several foods are consumed together.

A retrospective study using dietary pattern analysis based on the 2010 Alternative Healthy Eating Index has further demonstrated that a healthier diet was associated with reduced risk of rheumatoid arthritis occurring at 55 years of age or younger, particularly seropositive rheumatoid arthritis.115 Beneficial clinical results were also found to be associated with increased fatty acid intake but not with the concentration of circulating plasma antioxidants.116 However, plasma concentrations of vitamin C, retinol, and uric acid (all antioxidants reportedly enriched in Mediterranean diets), were inversely correlated with rheumatoid arthritis disease activity.117 Noticeably, both vegetarian and Mediterranean diets have been linked to increased production of health promoting SCFAs,118 119 which prevent the activation of effector T cells and abrogate the manifestation of undesirable local and systemic inflammatory responses, mostly in animal models of autoimmune disease.100 120 121 Although the mechanisms behind clinical amelioration of rheumatoid arthritis secondary to Mediterranean-type diets can logically be explained by perturbations in gut microbial ecology and associated SCFA driven immune modulation, this remains to be validated in humans.119

Polyunsaturated oils

The role of polyunsaturated oils in prevention and amelioration of rheumatoid arthritis has also been extensively studied. In population based studies, intake of fish oil was associated with a modest reduction in the risk of rheumatoid arthritis,122 with the premise that omega fatty acids could be responsible for their preventive effects.123 124 A recent dose-response meta-analysis reported a non-significant inverse association between fish consumption and rheumatoid arthritis.107 In support of this observation, other studies have shown beneficial effects of fish oil in patients with established rheumatoid arthritis and as a complementary intervention to triple disease modifying antirheumatic drug therapy in early rheumatoid arthritis.125 126 The inverse association between fish oil consumption and rheumatoid arthritis has mainly been attributed to the abundance of long chain n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in fish,127 which in turn promote eicosanoid synthesis and its downstream molecular and clinical anti-inflammatory effects.128

Studies in animal models have suggested that dietary extra-virgin olive oil prevents collagen induced arthritis via down-regulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and interleukin 17,129 likely owing to the effects of high concentrations of phenolic compounds (such as hydroxytyrosol) present in olive oil.130 Another intriguing explanation for the inverse association between fish and olive oil and rheumatoid arthritis derives from studies showing that the microbiota from animals fed a diet rich in saturated fats led to TLR driven inflammation via production of CCL2, a mediator of macrophage chemotaxis. Strikingly, the gut microbiota of mice fed with fish oil promoted anti-inflammatory responses when transplanted into obese animals, which suggests a possible biologic mechanism for saturated lipid induced, microbiota driven modulation of metabolic inflammation.131

Findings from several studies suggest that increased consumption of fruits and vegetables is associated with reduced risk of rheumatoid arthritis.123 132 This effect is, perhaps, mainly due to the antioxidant content of fruits and vegetables. The large prospective Iowa Women’s Health Study did not show a significant association between fruit intake and the risk of rheumatoid arthritis but did show a modest inverse association between consumption of cruciferous vegetables and the risk of this disease.

Red meat

Most of the evidence correlating intake of red meat and incidence of rheumatoid arthritis derives from large epidemiologic cohorts. A prospective study found that a high intake of meat was associated with an increased risk of rheumatoid arthritis,133 although the Nurses’ Health Study found no initial evidence of such an association.134 However, when the two Nurses’ Health Study cohorts with more incident cases of rheumatoid arthritis were combined, lower red meat intake was found to be significantly associated with decreased risk of early onset rheumatoid arthritis.115 Similarly, high sodium consumption was also associated with increased risk of rheumatoid arthritis,135 136 perhaps through expansion of Th17 cells via activation of serum glucocorticoid kinase.137

Diet and obesity in psoriatic disease

Obesity

Obesity is considered to be a risk factor for cutaneous psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Multiple epidemiologic studies have shown an increased incidence of these disorders in people with elevated body mass index (>30).138 139 140 Simultaneously, several studies reported an obesity rate in cutaneous psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis (around 30%), significantly higher than the overall prevalence of obesity in the general population (15-20%).141 142 143 144

Obese patients with cutaneous psoriasis have more severe skin involvement compared with lean patients138; they also have a poor response to a variety of biologic therapies, most notably TNF inhibitors, and weight loss improves the response to treatment.145 Similarly, obese patients with psoriatic arthritis do not respond adequately to standard therapies (compared with lean patients) and have increased difficulty in achieving minimal disease activity, even when drugs are dosed according to weight.110 Intriguingly, dietary weight loss has been shown to facilitate response to treatment and improve clinical outcomes.110 146 Moreover, evidence suggests that dramatic weight loss (through bariatric surgery) can result in significant improvement in cutaneous psoriasis, including discontinuation of therapy in around 40% of patients.147

The reasons for a decreased response to biologic therapies in obese patients, and specifically to TNF inhibitors, are yet to be fully elucidated.148 However, obesity leads to increased production of inflammatory cytokines (most notably TNFα), and changes to related molecules such as leptin and adiponectin, which may contribute to the development of multiple disturbances in predisposed people.149 150 Therefore, the “obesity of psoriatic disease” is regarded as a key link to the increased risk of comorbidities (diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular disease) that lead to further production of TNFα and related pro-inflammatory mediators.151 This overproduction of TNFα, in turn, increases susceptibility to psoriatic disease activity and concomitantly decreases overall response to therapy. The total burden of TNFα in an obese psoriatic patient (that is, both from excess adipose tissue and from the psoriatic process itself) may far exceed the ability of TNF inhibitors to block the effects of the overall inflammatory response.

Dietary factors

Other specific dietary interventions have shown benefit in psoriatic patients. A recent meta-analysis found that, of a variety of nutritional supplements reviewed, fish oil supplements resulted in the greatest clinical benefits compared with other supplements in RCTs. PASI scores decreased by 11.2 (SD 9.8) in the omega-3 group versus 7.5 (8.8) in the omega-6 group (P=0.048).152 Although oral vitamin D showed promise in open label studies, little evidence of benefit was seen for selenium or B12 supplementation.

Several epidemiologic and clinical studies have also linked gluten intake with the pathogenesis of psoriasis, particularly because patients with cutaneous psoriasis have a higher prevalence of celiac disease, a condition marked by sensitivity to dietary gluten.153 154 155 Several studies suggest that psoriasis and celiac disease share common genetic and inflammatory pathways. A recent meta-analysis of nine case-control studies showed that psoriasis was associated with an increased frequency of celiac markers (odds ratio 2.36, 95% confidence interval 1.15 to 4.83).156 Another systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies reported an approximately threefold increased risk of celiac disease among patients with cutaneous psoriasis.157 Moreover, several small studies have evaluated a possible therapeutic effect of a gluten-free diet on severity of psoriasis, particularly in those patients with celiac antibodies.156 158

Summary of dietary studies

Noticeably, many of these dietary trials have been conducted using a variety of study designs (ranging from uncontrolled to randomized, double blind, placebo controlled), in different diseases and populations and with different timespans (days to months), dosage, and endpoints. It is therefore critical that future studies dissect the influence of each of these factors independently. Furthermore, it will be important to determine for how long the beneficial effects observed in some of these studies persist after the dietary interventions are interrupted. Noticeably, none of the studies on rheumatoid arthritis or psoriatic disease has assessed how the microbiome fluctuates after the intervention. This is an important limitation, as it is unclear whether their beneficial effects are mediated by the microbiome or through some other alternative mechanism.

Probiotics and prebiotics in IBD and systemic autoimmune diseases

Probiotics and prebiotics in IBD

One of the first premises in microbiome research was that the intestinal microbiota could be positively modified through the ingestion of probiotics containing living beneficial bacteria or prebiotics containing non-digestible supplements that induce the growth (and/or activity) of commensal microorganisms. Although this has led to a growing and profitable market worldwide, the evidence behind health promoting properties of either strategy is still limited (supplementary table B).

Probiotics have been investigated for their theoretical potential to treat immune and inflammatory disorders. Because probiotics are taken orally, they must be able to resist passage through the acidic environment of the stomach. Moreover, as they do not colonize the gut permanently, they must be taken indefinitely for any benefits to be maintained, which may limit their effectiveness.

Controversial evidence exists for a beneficial effect of probiotics in treating IBD.159 In Crohn’s disease, two open label studies using Lactobacillus rhamnosus and a combination of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium species showed improved clinical disease activity index scores,160 161 although a placebo controlled trial did not find differences in time to relapse.162 A study of E coli Nissle 1917, a commonly used probiotic, did not find significant differences compared with placebo either.163 Other meta-analyses have also failed to find a benefit of probiotics in Crohn’s disease,164 165 suggesting that there is no strong evidence to date to support a beneficial role of probiotics in induction or maintenance of remission in Crohn’s disease.

Similarly, the evidence to date in ulcerative colitis is contradictory, with some studies showing a beneficial effect of probiotics such as VSL #3 or Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus,166 167 whereas others fail to do so.168 169 Meta-analyses also seem to suggest no significant difference between the use of probiotic and placebo for efficacy and safety.170

As an alternative to directly providing probiotics that generally do not engraft in the host, prebiotics are non-digestible substances aimed at stimulating the growth of certain beneficial bacteria. Prebiotics are thought to lower luminal pH through bacterial fermentation, promote barrier integrity, and down-regulate pro-inflammatory cytokines.171 Similar to probiotics, evidence for a beneficial effect of prebiotics in inflammatory disease is limited. In Crohn’s disease, there seems to be no clinical benefit (or any significant change in abundance of Bifidobacteria or F prausnitzii) when using fructo-oligosaccharides.172 Lactulose also failed to improve clinical or endoscopic outcomes of ulcerative colitis activity.173 There is, however, some indication that oligofructose, when combined with inulin, could reduce levels of inflammation as measured by fecal calprotectin.174 Nevertheless, the efficacy of prebiotics can be partially mediated by chain length,175 176 with longer chains generally exerting a stronger prebiotic effect.177

Probiotics and prebiotics in rheumatoid arthritis and spondyloarthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis

Several studies have investigated the potential anti-inflammatory and clinical benefits of probiotics in rheumatoid arthritis, mostly relatively small RCTs. One such RCT found that in patients with chronic rheumatoid arthritis on stable drug treatment, Lactobacillus casei significantly decreased disease activity score of 28 joints (DAS28) compared with placebo and also altered the balance of cytokines in favor of an anti-inflammatory response (increased interleukin 10 and decreased TNF and interleukin 6).178 These results are similar to that of a second RCT in which 30 patients received a consortium of probiotics (a daily capsule containing three viable strains: Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lactobacillus casei, and Bifidobacterium bifidum).179 In this case, eight weeks of probiotic supplementation in addition to conventional disease modifying antirheumatic drugs resulted in improved DAS28 (−0.3 (SD) 0.4 v −0.1 (0.4); P=0.01) and decreased serum high sensitivity C-reactive protein concentrations (−6.66 (2.56) v −3.07 (5.53) mg/mL; P<0.001) compared with placebo. A previous, small pilot study of administration of L casei to patients with mild rheumatoid arthritis reported a similar effect.180 However, a third RCT found that administration of another Lactobacillus strain (L rhamnosus) was not efficacious after 52 weeks.181

Spondyloarthritis

Even fewer data are available for the use of probiotics in other types of inflammatory arthritis. Despite extensive work on the role of the gut microbiota in the pathogenesis of spondyloarthritis (for example, HLA-B27 transgenic rats and the SKG mouse model), only one study looked at 63 patients with active spondyloarthritis and randomized them to either an oral probiotic consortium (Streptococcus salivarius, Bifidobacterium lactis, and Lactobacillus acidophilus) or placebo for 12 weeks.182 Although no relevant adverse events were recorded, no significant differences were seen in any of the outcomes, including Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index or Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index. Nevertheless, evidence exists to support immunologic benefits in patients with severe ankylosing spondylitis who received Bacteroides fragilis.183 Similarly, one small RCT in patients with psoriasis showed improvement in inflammatory responses but no positive clinical outcomes.184

Summary of probiotics and prebiotics

Overall, the accumulated evidence on the use of probiotics and prebiotics in inflammatory conditions is not robust. As with other bacterially mediated therapies, part of the challenge stems from the disparity of study designs and criteria used to define health outcomes. Importantly, the lack of a well defined rationale for choosing specific prebiotics or probiotics also contributes to the challenges in the field. Studies that comprehensively examine the properties of different bacterial strains in vivo and characterize their beneficial or deleterious properties continue to be needed before additional clinical trials test their efficacy in treating inflammatory and immune disorders.

Fecal microbiota transplant

Fecal microbiota transplant (FMT), or the transfer of intestinal microbiome from a healthy donor to a patient, has received considerable attention as a potential therapy for inflammatory disease given its astonishing success in the treatment (and even cure) of Clostridium difficile infection (CDI).185 This has been achieved both using filtered fecal material and with pills containing frozen biosamples.186 187 188 FMT has also been used with some success in conditions such as metabolic syndrome.189 However, the efficacy of FMT in IBD initially yielded mixed results. Pioneering studies in a small number of patients reported anecdotal reversal of symptoms.190 However, a non-randomized study of single colonoscopic FMT in six patients with chronic active ulcerative colitis who were non-responsive to standard therapy resulted in changes in microbial composition but no clinical remission.191 An RCT in 50 patients with mild to moderate ulcerative colitis found that 30% of participants receiving naso-duodenal FMT from a healthy donor achieved the primary endpoint (clinical remission and 1 point decrease in Mayo endoscopic score at week 12), compared with 20% in controls (autologous FMT).192 Although the differences were not statistically significant, the microbiome of responders after FMT showed features distinct from non-responders, with higher similarity to donors. A second randomized study of 75 patients with mild to moderate ulcerative colitis receiving FMT or placebo (water) via enema initially reported negative results, with the primary outcome defined as a Mayo score of 2 with an endoscopic Mayo score of 0 at week 7. Surprisingly, the subsequent addition of 22 participants receiving FMT from a single donor resulted in a positive study, with 24% of responders in the FMT group versus 5% in the placebo group.193

More recently, the FOCUS trial has reported a strong positive result in inducing clinical remission and endoscopic response at eight weeks.193The study randomized 81 patients with mild to moderate ulcerative colitis to either intensive treatment with FMT (pooled from multiple donors) or placebo, with both groups receiving an initial colonoscopic infusion followed by enema (five days a week for the duration of the study). Intriguingly, 27% of the FMT treated patients had steroid-free clinical remission plus endoscopic remission or response, compared with only 8% of the patients given placebo (P=0.02), providing further evidence for the efficacy of FMT in treating ulcerative colitis. A more recent prospective open label study of single FMT in 20 patients with active ulcerative colitis found increased bacterial diversity after FMT and clinical remission in 15% of the patients by week 4.194 Interestingly, Mayo scores improved significantly in biologic-naive patients compared with those previously exposed to biologics.

Although differences in study design (including primary endpoint), dosing, FMT route, or donor specific effects could explain the variable outcomes in these trials,195 fundamental questions about the use of FMT in inflammatory disorders remain unanswered. Firstly, what represents a positive outcome needs to be standardized. This would not only ensure fair comparisons between different trials but would also allow for meta-analyses that could leverage larger sample sizes to increase power. Furthermore, most studies to date use colonoscopy/enema instead of naso-duodenal administration. Although the Moayyedi and FOCUS trials suggest that the former might be the optimal route of administration,193 196 no study has specifically tried to answer this question in a comparative fashion.

Additionally, accurate dosing remains an untested variable, although the strong positive result of the FOCUS study again suggests that multiple FMTs might be necessary to achieve clinical and endoscopic remission. No established consensus exists as to what characteristics define optimal donors. The Moayyedi trial anecdotally reported a single donor who induced remission in a significantly larger number of recipients compared with other donors. A recent study by Jacob et al also found that donor composition correlated with clinical response in 20 patients with ulcerative colitis.194 However, we still lack an understanding of the specific mechanisms behind these observations.

Finally, characteristics of the recipient need to be considered when assessing the efficacy of FMT. Results from the Kump trial did not observe remission after FMT in patients with active ulcerative colitis.191 The Jacob study found that patients naive to biologics improved significantly compared with those previously exposed.194 The FOCUS study also reports higher pre-FMT diversity in responders than in non-responders.196 Future trials will be needed to investigate the relative efficacy of different donors (by using a fixed number of donors whose microbiota is transplanted to different patients) to determine the extent to which response is driven by the donor’s microbiota, by the recipient’s pre-FMT microbiota, or by other factors (such as level of engraftment).

Most studies of FMT have used whole microbial communities, from either single or pooled donors. Use of defined communities has clear benefits: simpler logistics, better manufacturing/quality control processes, and more clearly defined regulatory aspects, among others. Whether capsule based solutions are as effective as full FMT is unclear, however. As an example, CDI can be treated with bacterial pills, albeit with lower efficacy.186

The recently reported failure of the Seres trial has also cast some doubts on whether the success of CDI can be generalized to more complex diseases.197 We argue, however, that these results are confounded by multiple variables: which bacteria should be included, in what specific amounts, how to release them, and what the dosing should be. Future studies that look at some of these aspects are therefore needed to determine the feasibility of using defined bacterial communities.

Additionally, most studies have characterized the microbiome of patients post-FMT for a limited period of time, generally up to eight weeks at most.196 Assessing the persistence of the transplanted microbiome in patients for prolonged periods of time will be important to determine how often FMT might be needed to maintain remission. Furthermore, FMT studies generally measure clinical response, but there is no comprehensive immunologic characterization of the patients after transplant, with the notable exception of the Jacob study.194 Given the known relation between altered microbial composition and immune phenotypes, understanding how engraftment of specific microbiotas induces differentiated immune responses will be critical to gain further insights on mechanisms of action and, potentially, on how to improve FMT to treat inflammatory and immune conditions.

Emerging treatments for IBD and autoimmune disease

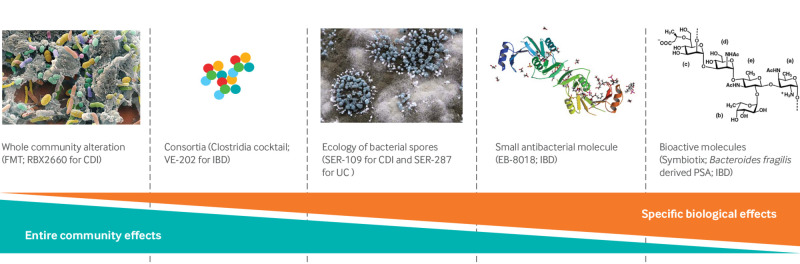

The encouraging results of FMT have sparked the interest of many research groups and drug companies that have focused on other possible therapies with potential microbiome altering properties.198 Because of the uncertainty about the best therapeutic strategy, multiple approaches are being tested with a broad spectrum ranging from community level interventions to highly specific targets (individual species/strains or bioactive metabolites; fig 2). One conceptual method relies on the incorporation of live organisms (either single strains or bacterial consortiums) to shift the gut ecology, circumventing the necessity for FMT-type approaches. This is mostly based on animal data showing preclinical efficacy in IBD models after the inoculation of Bacteroides fragilis or a cocktail of multiple strains of Clostridia.2 199

Fig 2.

Therapeutic strategies in pipeline to alter properties of microbiome. Various approaches in development and spectrum of microbiota modulation ranging from entire communities to individual species/strains and bioactive molecules

A second, more refined, approach focuses on taking advantage of previously described, bacterial derived, immunoregulatory molecules, such as polysaccharides, structural proteins, and SCFAs. Despite encouraging preclinical results, this is still a nascent field in which the effectiveness, toxicity profile, and long term effects of these microbiota derived molecules all remain to be studied in depth. As the potential benefits of these non-classic immunomodulators continue to be elucidated, a variety of biotechnology companies continue to invest in these therapeutic tools (table 2). However, several scientific and legal hurdles will need to be overcome before the gut microbiome can be successfully made “druggable.” As with FMT, several aspects of these technologies need further research, including understanding precise delivery systems of microbes to appropriate targets, biological viability, and regulatory aspects of intellectual property and patentability.200 201

Table 2.

Pipeline on microbiome derived therapeutics in inflammatory bowel disease and systemic autoimmunity

| Company | Microbiota product and indication | Development stage | Pharmaceutical partner/s |

|---|---|---|---|

| AvidBiotics | Targeted antibacterial bacteriocins (Avidocin/Purocin) | Preclinical | DuPont Nutrition & Health |

| CIPAC | Standardized approach to FMT for CDI and IBD (Full-Spectrum Microbiota) | Undisclosed | – |

| Enterome | Anti-Escherichia coli small molecule for IBD (EB-8018; EB110) | Phase I | Takeda, Janssen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Nestlé |

| 4D Pharma | Therapies from microbiome based molecules for IBS and IBD indication (Blautix; Thetanix) | Phase I | Publicly traded |

| Rebiotix Inc | Prescreened stool offered to health providers for FMT (microbiota restoration therapy for recurrent CDI; RBX2660) | Phase III (FDA breakthrough therapy designation for CDI); phase I (pediatric UC) | Private |

| Osel Inc | Single strains of native and genetically engineered bacteria for urogenital and gastrointestinal disease indications (Lactin V; CBM588) | Phase II | Private |

| Second Genome | Application of microbiome science for discovery of new therapies (eg, IBD; SGM-1019) | Phase I | Janssen, Pfizer, Roche, Monsanto |

| Seres Health | Therapeutics to catalyze restoration of healthy microbiome in CDI (SER-109) and UC (SER-287) | Phase III (FDA orphan drug designation for SER-109); phase I (SER-287) | Nestlé Health Science, publicly traded |

| Symbiotix | Bacteroides fragilis derived polysaccharide A for IBD and multiple sclerosis | Preclinical | |

| Vedanta Biosciences | Human microbiome consortia (Clostridia cocktail for IBD/allergy indications; VE-202) | Phase I/II | Janssen |

CDI=Clostridium difficile infection; FDA=Food and Drug Administration; FMT=fecal microbiota transplant; IBD=inflammatory bowel disease; IBS=irritable bowel syndrome; UC=ulcerative colitis.

Conclusion

The effects of dietary interventions in health and disease has been appreciated and studied since ancient times. Recently, there has been an explosion of data characterizing the complex interaction between foods, microbes, and derived metabolites (and combinations of these) with local intestinal and systemic immune responses. This work has been supported by the advent of a true technological revolution in microbiomics and associated disciplines, as well as paradigm shifting work by many groups in understanding mucosal immunology. As we dramatically enhance our basic physiologic knowledge of the biologic consequences of diet in the composition of gut bacterial ecology and associated bioactive metabolites, the clinical sciences are pursuing, albeit slowly, effective interventions that can modulate dysbiosis and its consequences in infectious and inflammatory disorders. More robust, well designed clinical trials coupled with detailed mechanistic work will be needed to accurately intervene for the treatment and perhaps even prevention of autoimmune diseases.

Glossary of abbreviations.

16S rRNA—16 small ribosomal subunit RNA

CDI—Clostridium difficile infection

CIA—collagen induced arthritis

CNS—central nervous system

DAS28—disease activity score of 28 joints

EAE—experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis

EEN—exclusive enteral nutrition

FMT—fecal microbiota transplant

GPR—G-protein coupled receptor

IBD—inflammatory bowel disease

ITS—internal transcribed spacer

MCFA—medium chain fatty acid

NORA—new onset rheumatoid arthritis

NZB—New Zealand Black

PduC—propanediol dehydratase

RCT—randomized clinical trial

SCFA—short chain fatty acid

SLE—systemic lupus erythematosus

Th17—T helper 17

TLR—toll-like receptor

TNF—tumor necrosis factor

Tregs—regulatory T cells

Future research questions.

Would local manipulation of intestinal microbiota affect clinical outcomes of systemic autoimmune disease?

Is there a “window of opportunity” for intervention to alter the intestinal microbiome to prevent or delay the onset of systemic inflammatory disease?

What are the potential unanticipated health effects of modifying the intestinal microbial community, such as the ability to respond to specific pathogens?

Further understanding the interaction of non-bacterial communities (eg, fungal, viral) with the host intestinal bacteria and immune system

What are the effects of the intestinal microbiota on immunomodulatory drug metabolism and therapeutic outcomes?

Web Extra.

Extra material supplied by the author

Supplementary tables

Contributors: All three authors were involved the conception, writing, and editing of the manuscript. All are guarantors.

Funding: Supported by grant No K23AR064318 and 1R03AR072182 from NIH/NIAMS to JUS, SUCCESS grant to JCC, Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America #362048 to JCC, the Judith and Stewart NYU Colton Center for Autoimmunity, and the Riley Family Foundation.

Competing interests: We have read and understood the BMJ policy on declaration of interests and declare the following interests: none.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient involvement: No patients were involved in the creation of this article.

Series explanation: State of the Art Reviews are commissioned on the basis of their relevance to academics and specialists in the US and internationally. For this reason they are written predominantly by US authors

References

- 1. Sender R, Fuchs S, Milo R. Are We Really Vastly Outnumbered? Revisiting the Ratio of Bacterial to Host Cells in Humans. Cell 2016;164:337-40. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mazmanian SK, Round JL, Kasper DL. A microbial symbiosis factor prevents intestinal inflammatory disease. Nature 2008;453:620-5. 10.1038/nature07008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Turnbaugh PJ, Ley RE, Hamady M, Fraser-Liggett CM, Knight R, Gordon JI. The human microbiome project. Nature 2007;449:804-10. 10.1038/nature06244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lederberg J. Infectious history. Science 2000;288:287-93. 10.1126/science.288.5464.287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. David LA, Maurice CF, Carmody RN, et al. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature 2014;505:559-63. 10.1038/nature12820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Abdollahi-Roodsaz S, Abramson SB, Scher JU. The metabolic role of the gut microbiota in health and rheumatic disease: mechanisms and interventions. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2016;12:446-55. 10.1038/nrrheum.2016.68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tamburini S, Shen N, Wu HC, Clemente JC. The microbiome in early life: implications for health outcomes. Nat Med 2016;22:713-22. 10.1038/nm.4142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kernbauer E, Ding Y, Cadwell K. An enteric virus can replace the beneficial function of commensal bacteria. Nature 2014;516:94-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Isaac S, Scher JU, Djukovic A, et al. Short- and long-term effects of oral vancomycin on the human intestinal microbiota. J Antimicrob Chemother 2017;72:128-36. 10.1093/jac/dkw383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Eckburg PB, Bik EM, Bernstein CN, et al. Diversity of the human intestinal microbial flora. Science 2005;308:1635-8. 10.1126/science.1110591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Weisburg WG, Barns SM, Pelletier DA, Lane DJ. 16S ribosomal DNA amplification for phylogenetic study. J Bacteriol 1991;173:697-703. 10.1128/jb.173.2.697-703.1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hugenholtz P, Goebel BM, Pace NR. Impact of culture-independent studies on the emerging phylogenetic view of bacterial diversity. J Bacteriol 1998;180:4765-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Huse SM, Dethlefsen L, Huber JA, Mark Welch D, Relman DA, Sogin ML. Exploring microbial diversity and taxonomy using SSU rRNA hypervariable tag sequencing. PLoS Genet 2008;4:e1000255. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sogin ML, Morrison HG, Huber JA, et al. Microbial diversity in the deep sea and the underexplored “rare biosphere”. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006;103:12115-20. 10.1073/pnas.0605127103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. De Filippis F, Laiola M, Blaiotta G, Ercolini D. Different amplicon targets for sequencing-based studies of fungal diversity. Appl Environ Microbiol 2017;83:e00905-17. 10.1128/AEM.00905-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Poretsky R, Rodriguez-R LM, Luo C, Tsementzi D, Konstantinidis KT. Strengths and limitations of 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing in revealing temporal microbial community dynamics. PLoS One 2014;9:e93827. 10.1371/journal.pone.0093827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Vineis JH, Ringus DL, Morrison HG, et al. Patient-Specific Bacteroides Genome Variants in Pouchitis. MBio 2016;7:e01713-16. 10.1128/mBio.01713-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tringe SG, Rubin EM. Metagenomics: DNA sequencing of environmental samples. Nat Rev Genet 2005;6:805-14. 10.1038/nrg1709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Round JL, Mazmanian SK. The gut microbiota shapes intestinal immune responses during health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol 2009;9:313-23. 10.1038/nri2515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tyson GW, Chapman J, Hugenholtz P, et al. Community structure and metabolism through reconstruction of microbial genomes from the environment. Nature 2004;428:37-43. 10.1038/nature02340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Aguiar-Pulido V, Huang W, Suarez-Ulloa V, Cickovski T, Mathee K, Narasimhan G. Metagenomics, Metatranscriptomics, and Metabolomics Approaches for Microbiome Analysis. Evol Bioinform Online 2016;12(Suppl 1):5-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Siggins A, Gunnigle E, Abram F. Exploring mixed microbial community functioning: recent advances in metaproteomics. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 2012;80:265-80. 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2011.01284.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Vilanova C, Porcar M. Are multi-omics enough? Nat Microbiol 2016;1:16101. 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. van Nood E, Vrieze A, Nieuwdorp M, et al. Duodenal infusion of donor feces for recurrent Clostridium difficile. N Engl J Med 2013;368:407-15. 10.1056/NEJMoa1205037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Berer K, Krishnamoorthy G. Microbial view of central nervous system autoimmunity. FEBS Lett 2014;588:4207-13. 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Frick JS, Autenrieth IB. The gut microflora and its variety of roles in health and disease. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 2013;358:273-89. 10.1007/82_2012_217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ahmed I, Roy BC, Khan SA, Septer S, Umar S. Microbiome, Metabolome and Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Microorganisms 2016;4:E20. 10.3390/microorganisms4020020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Blander JM, Longman RS, Iliev ID, Sonnenberg GF, Artis D. Regulation of inflammation by microbiota interactions with the host. Nat Immunol 2017;18:851-60. 10.1038/ni.3780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gensollen T, Iyer SS, Kasper DL, Blumberg RS. How colonization by microbiota in early life shapes the immune system. Science 2016;352:539-44. 10.1126/science.aad9378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Guo CJ, Chang FY, Wyche TP, et al. Discovery of Reactive Microbiota-Derived Metabolites that Inhibit Host Proteases. Cell 2017;168:517-526.e18. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.12.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cohen LJ, Esterhazy D, Kim SH, et al. Commensal bacteria make GPCR ligands that mimic human signalling molecules. Nature 2017;549:48-53. 10.1038/nature23874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Levin BJ, Huang YY, Peck SC, et al. A prominent glycyl radical enzyme in human gut microbiomes metabolizes trans-4-hydroxy-l-proline. Science 2017;355:eaai8386. 10.1126/science.aai8386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dogan B, Suzuki H, Herlekar D, et al. Inflammation-associated adherent-invasive Escherichia coli are enriched in pathways for use of propanediol and iron and M-cell translocation. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2014;20:1919-32. 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Atarashi K, Tanoue T, Ando M, et al. Th17 Cell Induction by Adhesion of Microbes to Intestinal Epithelial Cells. Cell 2015;163:367-80. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.08.058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hudcovic T, Stĕpánková R, Cebra J, Tlaskalová-Hogenová H. The role of microflora in the development of intestinal inflammation: acute and chronic colitis induced by dextran sulfate in germ-free and conventionally reared immunocompetent and immunodeficient mice. Folia Microbiol (Praha) 2001;46:565-72. 10.1007/BF02818004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sellon RK, Tonkonogy S, Schultz M, et al. Resident enteric bacteria are necessary for development of spontaneous colitis and immune system activation in interleukin-10-deficient mice. Infect Immun 1998;66:5224-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gkouskou KK, Deligianni C, Tsatsanis C, Eliopoulos AG. The gut microbiota in mouse models of inflammatory bowel disease. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2014;4:28. 10.3389/fcimb.2014.00028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sokol H, Seksik P. The intestinal microbiota in inflammatory bowel diseases: time to connect with the host. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2010;26:327-31. 10.1097/MOG.0b013e328339536b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kolho KL, Korpela K, Jaakkola T, et al. Fecal Microbiota in Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Its Relation to Inflammation. Am J Gastroenterol 2015;110:921-30. 10.1038/ajg.2015.149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Morgan XC, Tickle TL, Sokol H, et al. Dysfunction of the intestinal microbiome in inflammatory bowel disease and treatment. Genome Biol 2012;13:R79. 10.1186/gb-2012-13-9-r79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Machiels K, Joossens M, Sabino J, et al. A decrease of the butyrate-producing species Roseburia hominis and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii defines dysbiosis in patients with ulcerative colitis. Gut 2014;63:1275-83. 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-304833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sokol H, Pigneur B, Watterlot L, et al. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii is an anti-inflammatory commensal bacterium identified by gut microbiota analysis of Crohn disease patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008;105:16731-6. 10.1073/pnas.0804812105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Watanabe Y, Nagai F, Morotomi M. Characterization of Phascolarctobacterium succinatutens sp. nov., an asaccharolytic, succinate-utilizing bacterium isolated from human feces. Appl Environ Microbiol 2012;78:511-8. 10.1128/AEM.06035-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Forbes JD, Van Domselaar G, Bernstein CN. The Gut Microbiota in Immune-Mediated Inflammatory Diseases. Front Microbiol 2016;7:1081. 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Zechner EL. Inflammatory disease caused by intestinal pathobionts. Curr Opin Microbiol 2017;35:64-9. 10.1016/j.mib.2017.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Gevers D, Kugathasan S, Denson LA, et al. The treatment-naive microbiome in new-onset Crohn’s disease. Cell Host Microbe 2014;15:382-92. 10.1016/j.chom.2014.02.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Palm NW, de Zoete MR, Cullen TW, et al. Immunoglobulin A coating identifies colitogenic bacteria in inflammatory bowel disease. Cell 2014;158:1000-10. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.08.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Viladomiu M, Kivolowitz C, Abdulhamid A, et al. IgA-coated E. coli enriched in Crohn’s disease spondyloarthritis promote TH17-dependent inflammation. Sci Transl Med 2017;9:eaaf9655. 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf9655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Abdollahi-Roodsaz S, Joosten LA, Koenders MI, et al. Stimulation of TLR2 and TLR4 differentially skews the balance of T cells in a mouse model of arthritis. J Clin Invest 2008;118:205-16. 10.1172/JCI32639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Rogier R, Ederveen THA, Boekhorst J, et al. Aberrant intestinal microbiota due to IL-1 receptor antagonist deficiency promotes IL-17- and TLR4-dependent arthritis. Microbiome 2017;5:63. 10.1186/s40168-017-0278-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Matsumoto I, Staub A, Benoist C, Mathis D. Arthritis provoked by linked T and B cell recognition of a glycolytic enzyme. Science 1999;286:1732-5. 10.1126/science.286.5445.1732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Wu HJ, Ivanov II, Darce J, et al. Gut-residing segmented filamentous bacteria drive autoimmune arthritis via T helper 17 cells. Immunity 2010;32:815-27. 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Liu X, Zeng B, Zhang J, et al. Role of the Gut Microbiome in Modulating Arthritis Progression in Mice. Sci Rep 2016;6:30594. 10.1038/srep30594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Mizuno M, Noto D, Kaga N, Chiba A, Miyake S. The dual role of short fatty acid chains in the pathogenesis of autoimmune disease models. PLoS One 2017;12:e0173032. 10.1371/journal.pone.0173032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Scher JU, Sczesnak A, Longman RS, et al. Expansion of intestinal Prevotella copri correlates with enhanced susceptibility to arthritis. Elife 2013;2:e01202. 10.7554/eLife.01202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Maeda Y, Kurakawa T, Umemoto E, et al. Dysbiosis contributes to arthritis development via activation of autoreactive T cells in the intestine. Arthritis Rheumatol 2016;68:2646-61. 10.1002/art.39783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Weinreich S, Eulderink F, Capkova J, et al. HLA-B27 as a relative risk factor in ankylosing enthesopathy in transgenic mice. Hum Immunol 1995;42:103-15. 10.1016/0198-8859(94)00034-N [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Reháková Z, Capková J, Stĕpánková R, et al. Germ-free mice do not develop ankylosing enthesopathy, a spontaneous joint disease. Hum Immunol 2000;61:555-8. 10.1016/S0198-8859(00)00122-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Sinkorová Z, Capková J, Niederlová J, Stepánková R, Sinkora J. Commensal intestinal bacterial strains trigger ankylosing enthesopathy of the ankle in inbred B10.BR (H-2(k)) male mice. Hum Immunol 2008;69:845-50. 10.1016/j.humimm.2008.08.296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Sakaguchi N, Takahashi T, Hata H, et al. Altered thymic T-cell selection due to a mutation of the ZAP-70 gene causes autoimmune arthritis in mice. Nature 2003;426:454-60. 10.1038/nature02119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Yoshitomi H, Sakaguchi N, Kobayashi K, et al. A role for fungal beta-glucans and their receptor Dectin-1 in the induction of autoimmune arthritis in genetically susceptible mice. J Exp Med 2005;201:949-60. 10.1084/jem.20041758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Taurog JD, Richardson JA, Croft JT, et al. The germfree state prevents development of gut and joint inflammatory disease in HLA-B27 transgenic rats. J Exp Med 1994;180:2359-64. 10.1084/jem.180.6.2359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Lin P, Bach M, Asquith M, et al. HLA-B27 and human β2-microglobulin affect the gut microbiota of transgenic rats. PLoS One 2014;9:e105684. 10.1371/journal.pone.0105684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Asquith MJ, Stauffer P, Davin S, Mitchell C, Lin P, Rosenbaum JT. Perturbed mucosal immunity and dysbiosis accompany clinical disease in a rat model of spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2016;68:2151-62. 10.1002/art.39681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Asquith M, Davin S, Stauffer P, et al. Intestinal Metabolites Are Profoundly Altered in the Context of HLA-B27 Expression and Functionally Modulate Disease in a Rat Model of Spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2017;69:1984-95. 10.1002/art.40183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Costello ME, Ciccia F, Willner D, et al. Brief Report: Intestinal Dysbiosis in Ankylosing Spondylitis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2015;67:686-91. 10.1002/art.38967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Stoll ML, Kumar R, Morrow CD, et al. Altered microbiota associated with abnormal humoral immune responses to commensal organisms in enthesitis-related arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther 2014;16:486. 10.1186/s13075-014-0486-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Stoll ML, Wilson L, Barnes S, et al. Multi-omics studies of gut microbiota in enthesitis-related arthritis identify diminished microbial diversity and altered tryptophan metabolism as potential factors in disease pathogenesis [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol 2015;67 suppl 10. [Google Scholar]