Abstract

The knowledge on the genetic background of refractive error and myopia has expanded dramatically in the past few years. This white paper aims to provide a concise summary of current genetic findings and defines the direction where development is needed.

We performed an extensive literature search and conducted informal discussions with key stakeholders. Specific topics reviewed included common refractive error, any and high myopia, and myopia related to syndromes.

To date, almost 200 genetic loci have been identified for refractive error and myopia, and risk variants mostly carry low risk but are highly prevalent in the general population. Several genes for secondary syndromic myopia overlap with those for common myopia. Polygenic risk scores show overrepresentation of high myopia in the higher deciles of risk. Annotated genes have a wide variety of functions, and all retinal layers appear to be sites of expression.

The current genetic findings offer a world of new molecules involved in myopiagenesis. As the missing heritability is still large, further genetic advances are needed. This Committee recommends expanding large-scale, in-depth genetic studies using complementary big data analytics, consideration of gene-environment effects by thorough measurement of environmental exposures, and focus on subgroups with extreme phenotypes and high familial occurrence. Functional characterization of associated variants is simultaneously needed to bridge the knowledge gap between sequence variance and consequence for eye growth.

Keywords: myopia, refractive error, genetics, GWAS, GxE interactions

1. Summary

For many years, it has been recognized that myopia is highly heritable, but only recently has significant progress been made in dissecting the genetic background. In particular genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have successfully identified many common genetic variants associated with myopia and refractive error. It is clear that the trait is complex, with many genetic variants of small effect that are expressed in all retinal layers, often with a known function in neurotransmission or extracellular matrix. Exact mechanisms by which these genes function in a retina-to-sclera signaling cascade and other potential pathways remain to be elucidated. The prediction of myopia from genetic risk scores is improving, but whether this knowledge will affect clinical practice is yet unknown. This Committee recommends expanding large-scale genetic studies to further identify the molecular mechanisms through which environmental influences cause myopia (gene-by-environment effects), with an ultimate view to develop targeted treatments.

2. Key Points

Refractive errors including myopia are caused by a complex interplay between many common genetic factors and environmental factors (near work, outdoor exposure).

Early linkage studies and candidate gene studies have identified up to 50 loci and genes, but findings remained mostly unverified in replication studies.

Large consortia performing GWAS enabled identification of common genetic variants associated with refractive error and myopia.

The Consortium for Refractive Error and Myopia (CREAM) and 23andMe published findings from GWAS separately, and later combined studies in a GWAS meta-analysis, identifying 161 common variants for refractive error but explaining only approximately 8% of the phenotypic variance of this trait.

Polygenic risk scores based on these variants indicate that persons at high genetic risk have an up to 40 times increased risk of myopia compared with persons at low genetic risk.

The genetic loci appear to play a role in synaptic transmission, cell-cell adhesion, calcium ion binding, cation channel activity, and the plasma membrane. Many are light-dependent and related to cell-cycle and growth pathways.

Pathway analysis confirms the hypothesis for a light-induced retina-to-sclera signaling pathway for myopia development.

Genome-environment-wide interaction studies (GEWIS) assessing variant × education interaction effects identified nine other loci. Evidence for statistical interaction was also found; those at profound genetic risk with higher education appeared particularly susceptible to developing myopia.

As most of the phenotypic variance of refractive errors is still unexplained, larger sample sizes are required with deeper coverage of the genome.

The ultimate aim of genetic studies is to discern the molecular signaling cascade and open up new avenues for intervention.

3. Introduction

Although myopia is strongly determined by environmental factors, the trait has long been known to run in families, suggesting a genetic predisposition. The heritability of refractive error, using spherical equivalent as a quantitative trait, has been determined in a number of families and twin studies.1–8 The estimates resulting from these studies calculated heritabilities from 15% to 98%.5,7–10 However, it is important to note that this does not necessarily imply that most refractive error is genetic; familial clustering also can be determined by other factors.11

Like many other traits, common myopia has a complex etiology that is influenced by an interplay of genetic and environmental factors.12 The current evidence, as summarized in this review, indicates that it is likely to be caused by many genes, each contributing a small effect to the overall myopia risk. The evidence for this has been confirmed by large GWAS.1–5,7,13,14 Several high, secondary syndromic forms of myopia, such as Marfan, Stickler, and Donnai-Barrow, form the exception, as they inherit predominantly in a Mendelian fashion with one single, highly penetrant, causal gene.15

This white paper aims to address the recent developments in genetic dissection of common refractive errors, in particular myopia. Up until the era of GWAS, identification of disease-associated genes relied on studies using linkage analysis in families or investigating variants in candidate genes. In myopia, these were singularly unsuccessful, and before 2009, there were no genes known for common myopia occurring in the general population. However, with the advent of GWAS, many refractive error genes associated with myopia have been identified, providing potential new insights into the molecular machinery underlying myopia, and perhaps promising leads for future therapies.

4. Heritability

Eighty years ago, Sir Duke-Elder was one of the first to recognize a “hereditary tendency to myopia.”16 Since then, evidence for familial aggregation has been delivered by various familial clustering, twin, and offspring studies,1–4 and a genetic predisposition became more widely recognized. Strikingly, the estimates of myopia heritability vary widely among studies, with values as low as 10%9,10 found in a parent-offspring study in Eskimos, to as high as 98% in a study of female twin pairs5,7,8 (Table 1). Differences in study design and method of analysis may account for this, but it is also conceivable that the phenotypic variance determined by heritable factors is high in settings in which environmental triggers are limited, and low where they are abundant. Based on literature, heritability of myopia is probably between 60% and 80%.

Table 1.

Heritability Estimates of Refractive Error

|

Subjects |

Study |

Heritability Estimate (±SE or 95% CI) |

| Monozygous and dizygous twin pairs | Dirani et al. 20066 | 0.88 ± 0.02 (men) (SE) |

| Hammond et al. 200121 | 0.86 (0.83–0.89) | |

| Lyhne et al. 20017 | 0.89–0.94 (0.82–0.96) | |

| Sibling pair | Guggenheim et al. 2007152 | 0.90 (0.62–1.12) |

| Peet et al. 2007153 | 0.69 (0.58–0.85) | |

| Full pedigree | Klein et al. 200919 | 0.62 ± 0.13 |

| Parent-offspring pair | Lim et al. 2014154 | 0.30 (0.27–0.33) |

Variation in corneal curvature and axial length contribute to the degree of myopia.17 Twin studies also estimated a high heritability for most of the individual biometric parameters.18,19 Correlations between corneal curvature and axial length were at least 64%,20 suggesting a considerable genetic overlap between the parameters.

Studies addressing the inheritance structure of myopia and its endophenotypes identified several models, mostly a combination of additive genetic and environmental effects.6,18,21,22 Genome-wide complex trait analysis, using high-density genome-wide single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) genotype information, was performed in young children from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC), and results suggested that common SNPs explained approximately 35% of the variation in refractive error between unrelated subjects.23 SNP heritability calculated by linkage disequilibrium score regression in the CREAM Consortium was 21% in European individuals but only 5% in Asian individuals, which could be due to the low representation of this ancestry.24

In conclusion, the genetic component of myopia and ocular biometry is well recognized, but its magnitude varies in studies depending on the population being studied, the study design, and the methodology. It is important to note that the recent global rise of myopia prevalence is unlikely to be due to genetic factors, but the degree of myopia may still be under genetic control.25

5. Linkage Studies

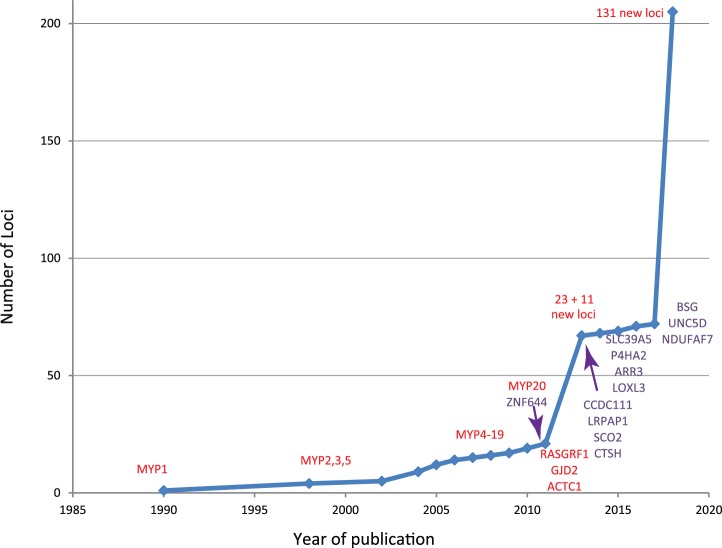

A number of linkage studies for myopia were performed in families and high-risk groups before the GWAS era (Fig. 1).26 Linkage studies have searched for cosegregation of genetic markers (such as cytosine-adenine [CA] repeats) with the trait through pedigrees, and has been successfully applied for many Mendelian disorders.27 In families with an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern of myopia, this approach helped to identify several independent loci for (high) myopia: MYP 1 to 20,26,28–30 as well as several other loci.31–36 Fine-mapping of several of these loci led to candidate genes, such as the IGF1 gene located in the MYP3 locus.12 Although validation of the same markers failed in these candidate genes, other variants appeared associated with common myopia, suggesting genetic overlap between Mendelian and complex myopia.37 Linkage studies using a complex inheritance design found five additional loci.38–42

Figure 1.

Historic overview of myopia gene finding. Genes identified using WES are marked as purple. Other loci (linkage studies, GWAS) are marked as red.

With the development of new approaches for gene finding, linkage analysis with CA-markers became unfashionable. Nevertheless, segregation and linkage analysis of a variant or region in pedigrees is still a common procedure for fine-mapping or dissection of disease haplotypes.

6. Secondary Syndromic Myopia

Myopia can accompany other systemic or ocular abnormalities. The secondary syndromic myopias are generally monogenic and have a wide spectrum of clinical presentations. Table 2 summarizes the known syndromic conditions that present with myopia, and Table 3 summarizes the known ocular conditions.43 Among these disorders are many mental retardation syndromes, such as Angelman (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man database [OMIM] #105830), Bardet-Biedl (OMIM #209900), and Cohen (OMIM #216550) and Pitt-Hopkins syndrome (OMIM #610954). Myopia also can be a characteristic feature in heritable connective tissue disorders, such as Marfan (OMIM #154700), Stickler (OMIM #108300, #604841, #614134, #614284), and Weill-Marchesani syndrome (OMIM #277600, #608328, #614819, #613195), and several types of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (OMIM #225400, #601776).

Table 2.

Overview of Secondary Syndromic Forms of Myopia: Systemic Syndromes Associated With Myopia

|

Title |

Gene and Inheritance Pattern |

| Acromelic frontonasal dysostosis | ZSWIM6 (AD) |

| Alagille syndrome | JAG1 (AD) |

| Alport syndrome | COL4A5 (XLD); COL4A3 (AR/AD) |

| Angelman syndrome | UBE3A (IP); CH |

| Bardet-Biedl syndrome | ARL6; BBS1; BBS2; BBS4; BBS5; BBS7; BBS9; BBS10; BBS12; CEP290; LZTFL1; MKKS; MKS1; SDCCAG8; TMEM67; TRIM32; TTC8; WDPCP (AR) |

| Beals syndrome | FBN2 (AD) |

| Beaulieu-Boycott-Innes syndrome | THOC6 (AR) |

| Bohring-Opitz syndrome | ASXL1 (AD) |

| Bone fragility and contractures; arterial rupture and deafness | PLOD3 (AR) |

| Branchiooculofacial syndrome | TFAP2A (AD) |

| Cardiofaciocutaneous syndrome | MAP2K2 (AD) |

| Cohen syndrome | VPS13B (AR) |

| Cornelia de Lange syndrome | NIPBL (AD); HDAC8 (XLD) |

| Cowden syndrome | PTEN (AD) |

| Cranioectodermal dysplasia | IFT122 (AR) |

| Cutis laxa | ATP6V0A2; ALDH18A1 (AR) |

| Danon disease | LAMP2 (XLD) |

| Deafness and myopia | SLITRK6 (AR) |

| Desanto-Shinawi syndrome | WAC (AD) |

| Desbuquois dysplasia | CANT1 (AR) |

| Donnai-Barrow syndrome | LRP2 (AR) |

| DOORS | TBC1D24 (AR) |

| Ehlers-Danlos syndrome | COL5A1 (AD); PLOD1 (AR); CHST14 (AR); ADAMTS2 (AR); B3GALT6 (AR); FKBP14 (AR) |

| Emanuel syndrome | CH |

| Fibrochondrogenesis | COL11A1 (AR) |

| Gyrate atrophy of choroid and retina with/without ornithinemia | OAT (AR) |

| Hamamy syndrome | IRX5 (AR) |

| Homocystinuria | CBS (AR) |

| Joint laxity; short stature; myopia | GZF1 (AR) |

| Kaufman oculocerebrofacial syndrome | UBE3B (AR) |

| Kenny-Caffey syndrome | FAM111A (AD) |

| Kniest dysplasia | COL2A1 (AD) |

| Knobloch syndrome | COL18A1 (AR) |

| Lamb-Shaffer syndrome | SOX5 (AD) |

| Lethal congenital contracture syndrome | ERBB3 (AR) |

| Leukodystrophy | POLR1C; POLR3A; POLR3B; GJC2 (AR) |

| Linear skin defects with multiple congenital anomalies | NDUFB11; COX7B (XLD) |

| Loeys-Dietz syndrome | TGFBR1; TGFBR2 (AD) |

| Macrocephaly/megalencephaly syndrome | TBC1D7 (AR) |

| Marfan syndrome | FBN1 (AD) |

| Marshall syndrome | COL11A1 (AD) |

| Microcephaly with/without chorioretinopathy; lymphedema; and/or mental retardation | KIF11 (AD) |

| Mohr-Tranebjaerg syndrome | TIMM8A (XLR) |

| Mucolipidosis | GNPTAG (AR) |

| Muscular dystrophy | TRAPPC11; POMT; POMT1; POMT2; POMGNT1; B3GALNT2; FKRP; DAG1; FKTN (AR) |

| Nephrotic syndrome | LAMB2 (AR) |

| Noonan syndrome | A2ML1; BRAF; CBL; HRAS; KRAS; MAP2K1; MAP2K2; NRAS; PTPN11; RAF1; RIT1; SOS1; SHOC2; SPRED1 (AD) |

| Oculocutaneous albinism | TYR (AR) |

| Oculodentodigital dysplasia | GJA1 (AR) |

| Pallister-Killian syndrome | CH |

| Papillorenal syndrome | PAX2 (AD) |

| Peters-plus syndrome | B3GLCT (AR) |

| Pitt-Hopkins syndrome | TCF4 (AD) |

| Pontocerebellar hypoplasia | CHMP1A (AR) |

| Poretti-Boltshauser syndrome | LAMA1 (AR) |

| Prader-Willi syndrome | NDN (PC); SNRPN (IP); CH |

| Pseudoxanthoma elasticum | ABCC6 (AR) |

| Renal hypomagnesemia | CLDN16; CLDN19 (AR) |

| SADDAN | FGFR3 (AD) |

| Schaaf-Yang syndrome | MAGEL2 (AD) |

| Schimke immunoosseous dysplasia | SMARCAL1 (AR) |

| Schuurs-Hoeijmakers syndrome | PACS1 (AD) |

| Schwartz-Jampel syndrome | HSPG2 (AR) |

| Sengers syndrome | AGK (AR) |

| Short stature; hearing loss; retinitis pigmentosa and distinctive facies | EXOSC2 (AR) |

| Short stature; optic nerve atrophy; and Pelger-Huet anomaly | NBAS (AR) |

| SHORT syndrome | PIK3R1 (AD) |

| Short-rib thoracic dysplasia with/without polydactyly | WDR19 (AR) |

| Shprintzen-Goldberg syndrome | SKI (AD) |

| Singleton-Merten syndrome | IFIH1 (AD) |

| Small vessel brain disease with/without ocular anomalies | COL4A1 (AD) |

| Smith-Magenis syndrome | RAI1 (AD) |

| Spastic paraplegia | HACE1 (AR) |

| Split hand/foot malformation | CH |

| Stickler syndrome | COL2A1 (AD); COL11A1 (AD); COL9A1 (AR); COL9A2 (AR) |

| Syndromic mental retardation | SETD5 (AD); MBD5 (AD); USP9X (XLD); NONO (XLR); RPL10 (XLR); SMS (XLR); ELOVL4 (AR); KDM5C (XLR) |

| Syndromic microphthalmia | OTX2; BMP4 (AD) |

| Temtamy syndrome | C12orf57 (AR) |

| White-Sutton syndrome | POGZ (AD) |

| Zimmermann-Laband syndrome | KCNH1 (AD) |

AD, autosomal dominant; AR, autosomal recessive; CH, chromosomal; IP, imprinting defect; XLD, × linked dominant; XLR, × linked recessive.

Table 3.

Overview of Secondary Syndromic Forms of Myopia: Ocular Syndromes Associated With Myopia

|

Title |

Gene and Inheritance Pattern |

| Achromatopsia | CNGB3 (AR) |

| Aland Island eye disease | GPR143 (XLR) |

| Anterior-segment dysgenesis | PITX3 (AD) |

| Bietti crystalline corneoretinal dystrophy | CYP4V2 (AD) |

| Blue cone monochromacy | OPN1LW; OPN1MW (XLR) |

| Brittle cornea syndrome | ZNF469; PRDM5 (AR) |

| Cataract | BFSP2; CRYBA2; EPHA2 (AD) |

| Colobomatous macrophthalmia with microcornea | CH |

| Cone dystrophy | KCNV2 (AD) |

| Cone rod dystrophy | C8orf37 (AR); RAB28 (AR); RPGR (XLR); CACNA1F (XLR) |

| Congenital microcoria | CH |

| Congenital stationary night blindness | NYX (XLR); CACNA1F (XLR); GRM6 (AR); SLC24A1 (AR); LRIT3 (AR); GNB3 (AR); GPR179 (AR) |

| Ectopia lentis et pupillae | ADAMTSL4 (AR) |

| High myopia with cataract and vitreoretinal degeneration | P3H2 (AR) |

| Keratoconus | VSX1 (AD) |

| Leber congenital amaurosis | TULP1 (AR) |

| Microcornea, myopic chorioretinal atrophy, and telecanthus | ADAMTS18 (AR) |

| Microspherophakia and/or megalocornea, with ectopia lentis and/or secondary glaucoma | LTBP2 (AR) |

| Ocular albinism | OCA2 (AR) |

| Primary open angle glaucoma | MYOC; OPTN (AD) |

| Retinal cone dystrophy | KCNV2 (AR) |

| Retinal dystrophy | C21orf2 (AR); TUB (AR) |

| Retinitis pigmentosa | RP1 (AD); RP2 (XLR); RPGR (XLR); TTC8 (AR) |

| Sveinsson chorioretinal atrophy | TEAD1 (AD) |

| Vitreoretinopathy | ZNF408 (AD) |

| Wagner vitreoretinopathy | VCAN (AD) |

| Weill-Marchesani syndrome | ADAMTS10 (AR); FBN1 (AD); LTBP2 (AR); ADAMTS17 (AR) |

A number of inherited retinal dystrophies also present with myopia, most strikingly X-linked retinitis pigmentosa caused by mutations in the RPGR-gene (retinal G protein–coupled receptor) (see Ref. 44 for common gene acronyms) and congenital stationary night blindness.45 Other eye disorders accompanied by myopia are ocular albinism (OMIM #300500) and Wagner vitreoretinopathy (OMIM #143200).

Most genes causing syndromic forms of myopia have not (yet) been implicated in common forms of myopia, except for collagen type II alpha 1 chain (COL2A1)46,47 and fibrilin 1 (FBN1).24,48 However, a recent study screened polymorphisms located in and around genes known to cause rare syndromic myopia, and found them to be overrepresented in GWASs on refractive error and myopia.49 This implies that although rare, pathogenic mutations in these genes have a profound impact on the eye; more benign polymorphisms may have only subtle effects on ocular biometry and refractive error.

7. Candidate Gene Studies

Candidate genes are generally selected based on their known biological, physiological, or functional relevance to the disease. Although sometimes highly effective, this approach is limited by its reliance on existing knowledge. Another caveat not specific for this approach is that genetic variability across populations can make it difficult to distinguish normal variation from disease-associated variation.13 In addition, candidate gene studies are very prone to publication bias, and therefore published results are highly selected.

Numerous genes have been investigated in candidate gene studies for refractive error traits. Table 4 summarizes all studies that reported statistically significant associations for myopia or ocular refraction. Genes that encode collagens (COL1A1, COL2A1),46,47 transforming growth factors (TGFβ1, TGFβ2, TGFβ-induced factor homeobox 1 [TGIF1]),50–52 hepatocyte growth factor and its receptor (HGF, CMET),53–55 insulin-like growth factor (IGF1),56,57 matrix metalloproteinases (MMP1, MMP2, MMP3, MMP9, MMP10),58,59 the lumican gene (LUM),60 and the ocular developmental gene PAX6,61 all showed promise in candidate gene studies. Unfortunately, like myopia linkage studies, these studies generally lacked validation by independent studies.62 Meta-analyses combining data from several candidate gene studies provided evidence for a consistent association between a single SNP in the PAX6 gene and extreme and high myopia.63 Meta-analyses of the LUM and IGF1 genes did not confirm an association.64,65

Table 4.

Summary of Candidate Gene Studies Reporting Positive Association Results With Myopia

|

Gene |

Study |

Ethnicity |

Independent Confirmation |

Replication in GWAS |

| APLP2 | Tkatchenko et al. 2015131 | Caucasian | – | – |

| BMP2K | Liu et al. 2009155 | Chinese | – | – |

| CHRM1 | Lin et al. 2009156 | Han Chinese | X157 | – |

| CHRM1 | Guggenheim et al. 2010158 | Caucasian | X157 | – |

| CMET | Khor et al. 200955 | Chinese | – | – |

| COL1A1 | Inamori et al. 2007159 | Japanese | – | – |

| COL2A1 | Mutti et al. 200746 | Caucasian | – | – |

| COL2A1 | Metlapally et al. 200947 | Caucasian | – | – |

| CRYBA4 | Ho et al. 2012160 | Chinese | – | – |

| HGF | Han et al. 200654 | Han Chinese | – | – |

| HGF | Yanovitch et al. 2009161 | Caucasian | – | – |

| HGF | Veerappan et al. 201053 | Caucasian | – | – |

| IGF1 | Metlapally et al. 201057 | Caucasian | – | – |

| LUM | Wang et al. 200660 | Chinese | – | – |

| LUM | Chen et al. 2009162 | Han Chinese | – | – |

| LUM | Lin et al. 2010164 | Chinese | – | – |

| LUM | Guggenheim et al. 2010158 | Caucasian | – | – |

| MFN1 | Andrew et al. 2008164 | Caucasian | X165 | – |

| MMP1 | Wojciechowski et al. 2010130 | Amish | – | – |

| MMP1 | Wojciechowski et al. 201359 | Caucasian | – | – |

| MMP10 | Wojciechowski et al. 201359 | Caucasian | – | – |

| MMP2 | Wojciechowski et al. 2010130 | Amish | – | – |

| MMP2 | Wojciechowski et al. 201359 | Caucasian | – | – |

| MMP3 | Hall et al. 200958 | Caucasian | – | – |

| MMP9 | Hall et al. 200958 | Caucasian | – | – |

| MYOC | Tang et al. 200763 | Chinese | – | – |

| MYOC | Vatavuk et al. 2009167 | Caucasian | – | – |

| MYOC | Zayats et al. 2009168 | Caucasian | – | – |

| PAX6 | Tsai et al. 2008169 | Chinese | – | – |

| PAX6 | Ng et al. 2009170 | Han Chinese | – | – |

| PAX6 | Han et al. 2009171 | Han Chinese | – | – |

| PAX6 | Miyake et al. 2012172 | Japanese | – | – |

| PAX6 | Kanemaki et al. 2015173 | Japanese | – | – |

| PSARL | Andrew et al. 2008164 | Caucasian | – | – |

| SOX2T | Andrew et al. 2008164 | Caucasian | – | |

| TGFβ1 | Lin et al. 200650 | Chinese | – | X24 |

| TGFβ1 | Zha et al. 2009174 | Chinese | – | X24 |

| TGFβ1 | Khor et al. 201056 | Chinese | – | X24 |

| TGFβ1 | Rasool et al. 2013175 | Indian | – | X24 |

| TGFβ2 | Lin et al. 200951 | Han Chinese | – | – |

| TGIF | Lam et al. 200352 | Chinese | – | – |

| TGIF1 | Ahmed et al. 201452,176 | Indian | – | – |

| LAMA1 | Zhao et al. 2011177 | Chinese | – | – |

| UMODL1 | Nishizaki et al. 2009178 | Japanese | – | – |

X indicates independent conformation or replication in GWAS study with reference included.

8. Genome-Wide Association Studies

Since the first GWAS in 2005,66 more than 3000 human GWAS have examined more than 1800 diseases and traits, and thousands of SNP associations have been found. This has greatly augmented our knowledge of human genetics and complex diseases.14 GWAS genotyping arrays can identify millions of SNPs across the genome in one assay; these variants are generally common and mostly not protein coding. Effect sizes of SNPs associated with disease are mostly small, requiring very large study samples to reach statistical significance.13,14 Fortunately, technological advances have lowered the costs of genotyping considerably over the years,67 and GWAS on hundreds of thousands of individuals are becoming more common.

8.1 GWAS of Refractive Errors and Myopia

GWAS for myopia have been performed using myopia as a dichotomous outcome or refractive error as a quantitative trait. Several endophenotypes have also been considered: spherical equivalent, axial length, corneal curvature, and age of diagnosis of myopia.

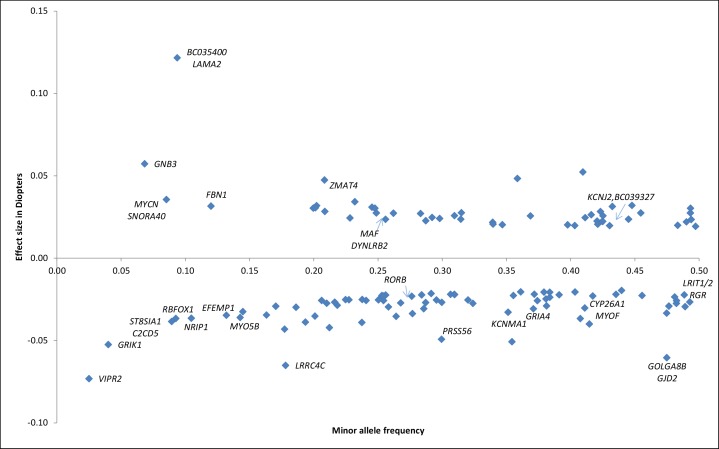

Figure 2 provides an overview of all associated loci and nearby genes, their frequency, and effect sizes.

Figure 2.

Effect sizes of common and rare variants for myopia and refractive error. Overview of SNPs and annotated genes found in the most recent GWAS meta-analysis.24 The x-axis displays the minor allele frequency of each SNP; y-axis displays the effect size of the individual SNP in diopters; We transformed the z-scores of the fixed effect meta-analysis between CREAM (refractive error) and 23andMe (age of diagnosis of myopia) into effect sizes in diopters with the following formula24:  .

.

8.1.1 Myopia Case-Control Design

The case-control design using (high) myopia as a dichotomous outcome has been especially popular in East Asia. The first case-control GWAS was performed in a Japanese cohort in 2009.68 It comprised 830 cases of pathologic myopia (defined as axial length >26 mm) and 1911 controls from the general population. The strongest association was located at 11q24.1, approximately 44 kb upstream of the BH3-like motif containing, cell death inducer (BLID) gene, and conferred odds of higher myopia of 1.37 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.21–1.54). Subsequently, a GWAS meta-analysis of two ethnic Chinese cohorts was performed in 287 cases of high myopia (defined as ≤ −6 diopters [D]) and 673 controls. The strongest association was for an intronic SNP within the catenin delta 2 (CTNND2) gene on 5p15.2.69 Neither of these associations met the conventional GWAS threshold (P ≤ 5 × 10−8) for statistical significance due to small sample size. Nevertheless, the locus at 5p15 encompassing the CTNND2 gene was later confirmed by other Asian studies.70–72

Li et al.73 studied 102 high myopia cases (defined as ≤ −8 D with retinopathy) and 335 controls in an ethnic Chinese population. The strongest association (P = 7.70 × 10−13) was a high-frequency variant located in a gene desert within the MYP11 myopia linkage locus on 4q25. In a similar ethnic Han Chinese population of 419 high myopia cases (≤ −6 D) and 669 controls, Shi et al.73,74 identified the strongest association (P = 1.91 × 10−16) at an intronic, high-frequency variant within the mitochondrial intermediate peptidase (MIPEP) gene on 13q12. Neither hit has been replicated, even in studies with similar design, phenotypic definition, and ethnic background.

In 2013, two papers reported loci for high myopia in Asian populations and these were successfully replicated. Shi et al.75 studied a Han Chinese population of 665 cases with high myopia (≤ −6 D) and 960 controls. Following two-stage replication in three independent cohorts, the most significantly associated variant (P = 8.95 × 10−14) was identified in the vasoactive intestinal peptide receptor 2 (VIPR2) gene within the MYP4 locus, followed by three other variants within a linkage disequilibrium block in the syntrophin beta 1 (SNTB1) gene (P = 1.13 × 10−8 to 2.13 × 10−11). Khor et al.76 reported a meta-analysis of four GWAS including 1603 cases of “severe” myopia and 3427 controls of East Asian ethnicity. After replication and meta-analysis, the SNTB1 gene was confirmed, and a novel variant within the ZFHX1B gene (also known as zinc finger E-box binding homeobox 2 [ZEB2]) reached genome-wide significance (P = 5.79 × 10−10).

In 2018, a pathologic myopia case-control study was performed in cohorts of Asian ancestry, using participants with −5.00 D or more myopia with an axial length >26 mm. Fundus photographs were graded pathologic or nonpathologic (Ncases = 828, Ncontrols = 3624). The researchers found a novel genetic variant in the coiled-coil domain containing 102B (CCDC102B) locus (P = 1.46 × 10−10), which was subsequently replicated in an independent cohort (P = 2.40 × 10−6). This gene is strongly expressed in the RPE and choroid. As myopic maculopathy is the primary cause of blindness in high myopia, further functional investigation could be valuable.77

In Europe, a French case-control GWAS was performed on 192 high myopia cases (≤ −6 D) and 1064 controls, and a suggestive association was identified within the MYP10 linkage locus, 3 kb downstream of protein phosphatase 1 regulatory subunit 3B (PPP1R3B). However, this association did not reach genome-wide statistical significance, and no previously reported loci were replicated.78 Later, in 2016, the direct-to-consumer genetic testing company 23andMe (Mountain View, CA, USA) published a large GWAS on self-reported myopia (Ncases = 106,086 and Ncontrols = 85,757; all European ancestry), and identified more than 100 novel loci for myopia.79 Because this study was intended for association analyses between traits, precise locus definitions, post-GWAS quality control, and replication were not performed.

8.1.2 Quantitative Design on Spherical Equivalent

Studies that considered refractive error as a quantitative trait, and included subjects from the general population who displayed the entire range of refractive error, have been more successful. In 2010, the first GWAS for spherical equivalent were carried out in two European populations: a British cohort of 4270 individuals and a Dutch cohort of 5328 individuals.80,81 Two loci surpassed the GWAS threshold and were replicated: one near the RASGFR1 gene on 15q25.1 (P = 2.70 × 10−09) and the other near GJD2 on 15q14 (P = 2.21 × 10−14). Subsequently, a meta-analysis was performed on 7280 individuals with refractive error from five different cohorts, which included various ethnic populations across different continents, and findings were replicated in 26,953 samples. A novel locus including the RBFOX1 gene on chromosome 16 reached genome-wide significance (P = 3.9 × 10−9).82

These collaborations paved the way for the formation of a large consortium to achieve higher statistical power for gene finding. CREAM was established in 2010 and included researchers and cohorts from the United States, Europe, Asia, and Australia. Its first collaborative work was replication of SNPs in the previously identified 15q14 loci.83 Other studies followed this approach, and confirmed 15q14 as well as the 15q25 locus.84,85 Subsequently, CREAM conducted a GWAS meta-analysis based on HapMapII imputation86 with 35 participating studies comprising 37,382 individuals of European descent and 12,332 of Southeast Asian ancestry with data on GWAS and spherical equivalent. This study enabled replication of GJD2, RASGRF1, and RFBOX1 and identification of 23 novel loci at genome-wide significance: BICC1, BMP2, CACNA1D, CD55, CHD7, CHRNG, CYP26A1, GRIA4, KCNJ2, KCNQ5, LOC100506035, LAMA2, MYO1D, PCCA, TJP2, PTPRR, SHISA6, PRSS56, RDH5, RORB, SIX6, TOX, and ZMAT472.87

Meanwhile, 23andMe performed a contemporaneous large GWAS on 55,177 individuals of European descent by using a survival analysis, based on the first release of 1000G88 (a catalog of human genetic variation). Its analysis was based on self-reported presence of myopia and age of spectacle wear as a proxy for severity. 23andMe also replicated GJD2, RASGRF1, and RFBOX1 and identified 11 new loci: BMP3, BMP4, DLG2, DLX1, KCNMA1, LRRC4C, PABPCP2, PDE11A, RGR, ZBTB38, ZIC2.89 Of the 22 loci discovered by CREAM, 8 were replicated by 23andMe, and 16 of the 20 loci identified by 23andMe were confirmed by CREAM. This was surprising, as the studies used very different phenotyping methods. In addition, the effect sizes of 25 loci were very similar, despite analyses on different scales: diopters for CREAM and hazard ratios for 23andMe.90 After these two publications, replication studies provided validation for KCNQ5, GJD2, RASGRF1, BICC1, CD55, CYP26A1, LRRC4C, LAMA2, PRSS56, RFBOX1, TOX, ZIC2, ZMAT4, and B4GALNT2 in per-SNP analyses, and for GRIA4, BMP2, BMP4, SFRP1, SH3GL2, and EHBP1L1 in gene-based analyses.91–96

Although CREAM and 23andMe found a large number of loci, only approximately 3% of the phenotypic variance of refractive error was explained.87,89 Larger GWAS meta-analyses were clearly needed, and the two large studies combined efforts. This new GWAS meta-analysis was based on the phase 1 version 3 release of 1000G, included 160,420 participants, and findings were replicated in the UK Biobank (95,505 participants). Using this approach, the number of validated refractive error loci increased to 161. A high genetic correlation between European and Asian individuals (>0.78) was found, implying that the genetic architecture of refractive error is quite similar for European and Asian individuals. Taken together, these genetic variants accounted for 7.8% of the explained phenotypic variance, leaving room for improvement. Even so, polygenic risk scores, which are constructed by the sum of effect sizes of all risk variants per individual depending on their genotypes, were well able to distinguish individuals with hyperopia from those with myopia at the lower and higher deciles. Interestingly, those in the highest decile had a 40-fold greater risk of myopia. The predictive value (area under the curve) of these risk scores for myopia versus hyperopia, adjusted for age and sex, was 0.77 (95% CI 0.75–0.79).

The next step will include GWAS on even larger sample sizes. Although this will improve the explained phenotypic variance, it is unlikely that GWAS will uncover the entire missing heritability. SNP arrays do not include rare variants, nor do they address gene-environment and gene-gene interactions, or epigenetic effects.

8.1.3 GWAS on Refractive Error Endophenotypes

As myopia is mostly due to increased axial length, researchers have used this parameter as a myopia proxy or “endophenotype.” The first axial length GWAS examined 4944 individuals of East and Southeast Asian ancestry, and a locus on 1q41 containing the zinc finger pseudogene ZC3H11B reached genome-wide significance (P = 4.38 × 10−10).82,97 A much larger GWAS meta-analysis of axial length comprised 12,531 European individuals and 8216 Asian individuals.93 This study identified eight novel genome-wide significant loci (RSPO1, C3orf26, LAMA2, GJD2, ZNRF3, CD55, MIP, ALPPL2), and also replicated the ZC3H11B gene. Notably, five of these loci had been associated with refractive error in previous GWAS.

Several relatively small GWAS have been performed for corneal curvature, and identified associations with FRAP1, PDGFRA (also associated with eye size), CMPK1, and RBP3.93,98–101 More recently Miyake et al.101,102 published a two-stage GWAS for three myopia-related traits: axial length, corneal curvature, and refractive error. The study was performed in 9804 Japanese individuals, with trans-ethnic replication in Chinese and Caucasian individuals. A novel gene, WNT7B, was identified for axial length (P = 3.9 × 10−13) and corneal curvature (P = 2.9 × 10−40), and the previously reported association with GJD2 and refractive error was replicated.

8.2 Genome-Wide Pathway Analyses

The main goal of GWAS is to improve insight on the molecules involved in disease, and help identify disease mechanisms. For myopia, a retina-to-sclera signaling cascade had been proposed for many years (see accompanying paper IMI – Report on Experimental Models of Emmetropization and Myopia103), but knowledge on its molecular drivers was limited. Several attempts were made to translate the findings from refractive error GWAS into this cascade.87,89,104 Here we provide an overview of genes annotated to the risk variants and their relationship to the underlying biological mechanism.

Deducted from the CREAM GWAS, pathways included neurotransmission (GRIA4), ion transport (KCNQ5), retinoic acid metabolism (RDH5), extracellular matrix remodeling (LAMA2, BMP2), and eye development (SIX6, PRSS56). Likewise, 23andMe proposed extracellular matrix remodeling (LAMA2, ANTXR2), the visual cycle (RDH5, RGR, KCNQ5), neuronal development (KCNMA1, RBFOX1, LRRC4C, NGL-1, DLG2, TJP2), eye and body growth (PRSS56, BMP4, ZBTB38, DLX1), and retinal ganglion cells (ZIC2, SFRP1)105 as functions. Hysi et al.106 performed pathway analyses using both the CREAM and 23andMe GWAS, and reported that plasma membrane, cell-cell adhesion, synaptic transmission, calcium ion binding, and cation channel activity were significantly overrepresented in refractive error in two British cohorts. Furthermore, by examining known protein-protein interactions, the investigators identified that many genes are related to cell-cycle and growth pathways, such as the MAPK and TGF-beta/SMAD pathways.

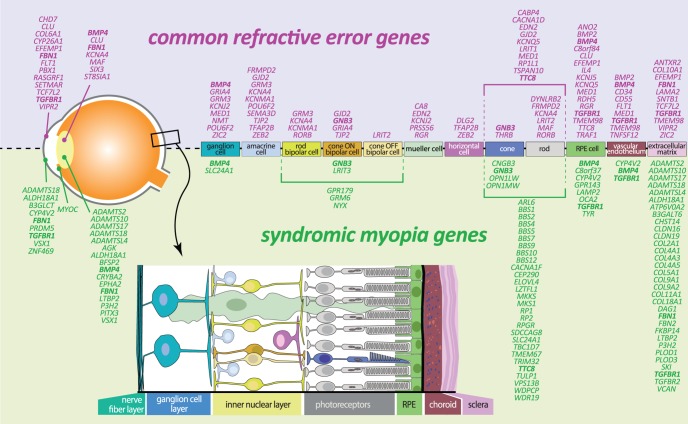

The latest update on pathway analysis in myopia stems from the meta-GWAS from CREAM and 23andMe.24 TGF-beta signaling pathway was a key player; the association with the DRD1 gene provided genetic evidence for a dopamine pathway. Most genes were known to play a role in the eye,107 and most significant gene sets were “abnormal photoreceptor inner segment morphology” (Mammalian Phenotype Ontology [MP] 0003730; P = 1.79 × 10−7), “thin retinal outer nuclear layer” (MP 0008515), “detection of light stimulus” (Gene Ontology [GO] 0009583), “nonmotile primary cilium” (GO 0031513), and “abnormal anterior-eye-segment morphology” (MP 0005193). Notably, RGR, RP1L1, RORB, and GNB3 were present in all of these meta-gene sets. Taken together, retinal cell physiology and light processing are clearly prominent mechanisms for refractive error development, and all cell types of the neurosensory retina, RPE, vascular endothelium, and extracellular matrix appear to be involved (Fig. 3). Novel mechanisms included rod-and-cone bipolar synaptic neurotransmission, anterior-segment morphology, and angiogenesis.24

Figure 3.

Schematic overview of expression in retinal cells of refractive error and syndromic myopia genes according to literature. Bold: genes identified for both common refractive error and in syndromic myopia.

9. Whole-Exome and Whole-Genome Sequencing

Unlike GWAS, whole-exome sequencing (WES) and whole-genome sequencing (WGS) have the potential to investigate rare variants. Exomes are interesting, as they directly contribute to protein translation, but they constitute only approximately 1% of the entire genome. WGS allows for identification of variants across the entire genome, but requires a high-throughput computational infrastructure and remains costly.

WES has been conducted primarily in case-control studies of early-onset high myopia or in specific families with a particular phenotype (i.e., myopic anisometropia) or inheritance pattern (i.e., X-linked).108–111 Several novel mutations in known myopia genes were identified this way: CCDC111,109 NDUFAF7,110 P4HA2,108 SCO2,112 UNC5D,111 BSG,113 ARR3,114 LOXL3,115 SLC39A5,116 LRPAP1,117 CTSH,117 ZNF644.118,119 Although most genetic variants displayed an autosomal dominant hereditary pattern,108,112,118,119 X-linked heterozygous mutations were identified in ARR3, only in female family members.114 The functions of these novel genes include DNA transcription (CCDC111, ZNF644), mitochondrial function (NDUFAF7, SCO2), collagen synthesis (P4HA2), cell signaling (UNC5D, BSG), retina-specific signal transduction (ARR3), TGF-beta pathway (LOXL3, SLC39A5, LRPAP1), and degradation of proteins in lysosomes (CTSH). Jiang et al.119 investigated family members with high myopia and identified new mutations in LDL receptor related protein associated protein 1 (LRPAP1), cathepsin H (CTSH ), zinc finger protein 644 isoform 1 (ZNF644), solute carrier family 39 (metal ion transporter) member 5 (SLC39A5), and SCO2, cytochrome c oxidase assembly protein (SCO2).119

Many clinicians have noticed that retinal dystrophies and ocular developmental disorders often coincide with myopia.115 This triggered Sun et al.120 to evaluate variants in a large number of retinal dystrophy genes in early-onset high myopia in 298 unrelated myopia probands and their families, and they thereby identified 29 potentially pathogenic mutations in COL2A1, COL11A1, PRPH2, FBN1, GNAT1, OPA1, PAX2, GUCY2D, TSPAN12, CACNA1F, and RPGR, and most had an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern. Kloss et al.121 performed WES in 14 families with high myopia, and identified 104 new genetic variants located in both known MYP loci (e.g., AGRN, EME1, and HOXA2) and in new loci (e.g., ATL3 and AKAP12).

To date, WGS has not been conducted for myopia or refractive error, most likely due to the reasons mentioned above. When costs for WGS decrease, these studies will undoubtedly be conceived.

10. Gene-Environment Interaction

It has become clear that environmental factors are driving the recent epidemic rise in the prevalence of myopia.122–126 To date, the most influential and consistent environmental factor is education. Studies have estimated that individuals going onto higher education have double the myopia prevalence compared with those who leave school after only primary education.127–129 Education has been a primary focus for gene-environment (GxE) interaction analyses in myopia. GxE studies have the potential to show modification of the effect of risk variants by environmental exposures, but can also reveal genetic associations that were hidden in unexposed individuals.

One of the first GxE studies for myopia investigated variants in matrix metalloproteinases genes (MMP1–MMP10). Two SNPs (rs1939008 and rs9928731) that were first found to be associated with refraction in Amish families were also associated in a lower but not in the higher education group of the Age-Related Eye Disease Study (AREDS) study. These results suggest that variants in these genes may play a role in refractive variation in individuals not exposed to myopic triggers.59,130 In contrast, a study combining human GWAS data and animal models of myopia provided an experimental example of GxE interaction involving a rare variant in the APLP2-gene only in children exposed to large amounts of daily reading.131 In addition, an analysis performed in five Singapore cohorts found risk variants in DNAH9, GJD2, and ZMAT4 that were more strongly associated in individuals who achieved higher secondary or university education.132 Significant biological interaction between education and other risk variants was studied using a genetic risk score of all known risk variants at the time (n = 26) derived from the CREAM meta-GWAS.133 European subjects with a high genetic load in combination with university-level education had a far greater risk of myopia than those with only one of these two factors. A study investigating GxE interactions in children and the major environmental risk-factors, nearwork, time outdoors, and 39 SNPs derived from the CREAM meta-GWAS revealed nominal evidence of interaction with nearwork (top variant in ZMAT4).133,134

GEWIS, using all variants from the CREAM meta-GWAS, revealed three novel loci (AREG, GABRR1, and PDE10A) for GxE in Asian populations, whereas no interaction effects were observed in Europeans due to many reasons, such as the quantitative differences in the intensity of nearwork during childhood.48 Up to now, there is no robust evidence that there are fundamental differences in the genetic background of myopia risk between European and Asian individuals.

11. Mendelian Randomization

Mendelian randomization (MR) is a method that allows one to test or estimate a causal effect from observational data in the presence of confounding factors. MR is a specific type of instrumental variable analysis that uses genetic variants with well-understood effects on exposures or modifiable biomarkers.135,136 Importantly, the SNP must affect the disease status only indirectly via its effect on the exposure of interest.137 MR is particularly valuable in situations in which randomized controlled trials are not feasible, where it is applied to help elucidate biological pathways.

Currently, three studies have been published on MR in refractive error and myopia. The first, published in 2016, explored the effect of education on myopia.138 This study constructed polygenic risk scores of genetic variants found in GWAS for educational attainment, and used these as the instrumental variable. Subsequently, results of three cohorts (Cooperative Health Research in the Region Augsburg [KORA], AREDS, Blue Mountain Eye Study [BMES]; total N = 5649) were meta-analyzed. Strikingly, approximately 2 years of education was associated with a myopic shift of −0.92 ± 0.29 D (P = 1.04 × 10−3), which was even larger than the observed estimate. Similar results were observed in data from the UK Biobank study (N = 67,798); MR was performed and causality of education was tested for myopic refractive error bi-directionally.139 Genetic variants for years of education from Social Science Genetic Association Consortium (SSGAC) and 23andMe studies were considered. Analyses of the observational data suggested that every additional year of education was associated with a myopic shift of −0.18 D per year (95% CI −0.19 to −0.17; P < 2.0−16). MR suggested the true causal effect was stronger: −0.27 D per year (95% CI −0.37 to −0.17; P = 4.0−8). As expected, there was no evidence that myopia was a cause for education (P = 0.6). The conclusion from these studies was that education appears truly causally related to myopia, and effects calculated by the current observational studies may be underestimated.

Because several studies had proposed that vitamin D has a protective effect against myopia,140–142 the third MR study investigated the causality of low vitamin D concentrations on myopia. Genetic variants of the DHCR7, CYP2R1, GC, and CYP24A1 genes with known effects on serum levels of vitamin D were used as instrumental variables in a meta-analysis of refractive error in CREAM (NEUR = 37,382 and NASN = 8,376). The estimated effects of vitamin D on refractive error were small in both ethnicities (Caucasians: −0.02 [95% CI −0.09, 0.04] D per 10 nmol/L increase in vitamin D concentration; Asian individuals: 0.01 [95% CI −0.17, 0.19] D per 10 nmol/L increase).These results suggest that the causal effect of vitamin D on myopia is very small, if any. Therefore, associations with vitamin D levels in the observational studies are likely to represent the effect of time spent outdoors.

12. Epigenetics

Epigenetic changes refer to functionally relevant changes to the genome that do not involve the nucleotide sequence of DNA. They represent other changes of the helix structure, such as DNA methylation and histone modification,143 and these changes can regulate gene expression. Noncoding RNAs are small molecules that can also regulate gene expression, mainly at the posttranscriptional level; they can be epigenetically controlled but can also drive modulation of the DNA chromatin structure themselves.144 Investigations into epigenetic changes of eye diseases still face some important technological hurdles. High-throughput next-generation sequencing technologies and high-resolution genome-wide epigenetic profiling platforms are still under development, and accessibility of RNA expression in human ocular tissues145 is limited. Moreover, epigenetic changes are tissue- and time-specific, so it is essential to study the right tissue at the correct developmental stage. Animal models are often used as a first step before moving to humans, although epigenetic processes are not always conserved across species. Nevertheless, there have been some attempts to reveal epigenetic changes involved in myopia development.

A experiment using monocular form deprivation in a mouse model found that hypermethylation of CpG sites in the promoter/exon 1 of COL1A1 may underlie reduced collagen synthesis at the transcriptional level in myopic scleras.146 A human study analyzing myopic individuals found that methylation of the CpG sites of the CRYAA promotor leads to lower expression of CRYAA in human lens epithelial cells.147

Myopia studies evaluating the role of noncoding RNAs are more common. The latest GWAS meta-analysis found 31 loci residing in or near regions transcribing small noncoding RNAs, thus hinting toward the key role of posttranscriptional processes and epigenetic regulation.24,144 MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are the best-characterized family of small noncoding RNAs. In their mature form, they are approximately 19 to 24 nucleotides in length and regulate hundreds of genes. They are able to bind to 3′ untranslated regions (UTRs) on RNA polymers by sequence-specific posttranscriptional gene silencing; one miRNA can regulate the translation of many genes. miRNAs have been a hot topic in past years due to the potential clinical application of these small RNA sequences: accessibility of the retina for miRNA-based therapeutic delivery has great potential for preventing and treating retinal pathology.148 In a case-control study, Liang et al.149 identified a genetic variant, rs662702, that was associated with the risk of extreme myopia in a Taiwanese population. The genetic variant was located at the 3′-UTR of PAX6, which is decreased in myopia. rs662702 is localized near the seed region of miR-328, and the C > T substitution leads to a mismatch between miR-328 and PAX6 mRNA. Further functional study indicated that the risk C allele reduced PAX6 expression relative to the T allele, which could result from knockdown effect of the C allele by miR-328. Therefore, reducing miR-328 may be a potential strategy for preventing or treating myopia.61 Another study focused on miR-184. This miRNA is the most abundant one in the cornea and the crystalline lens, and sequence mutations have been associated with severe keratoconus with early-onset anterior polar cataract. Lechner et al.149,150 sequenced miR-184 in 96 unrelated Han southern Chinese patients with axial myopia, but no mutations were detected. Xie et al.151 analyzed rs157907 A/G in miR-29a and rs10877885 C/T in let-7i in a severe myopia case-control study (Ncases = 254; Ncontrols = 300). The G allele of the rs157907 locus was significantly associated with decreased risk of severe myopia (P = 0.04), launching the hypothesis that rs157907 A/G might regulate miR-29a expression levels. Functional studies are needed to provide evidence for this theory.

13. Concluding Remarks

Research on myopia genetics, genetic epidemiology, and epigenetics is flourishing and is providing a wealth of new insights into the molecules involved in myopiagenesis. Despite this progress, the chain of events forming the myopia-signaling cascade and the triggers for scleral remodeling are still largely unknown. Next steps should include all the novel technological advances for dissecting complex disorders, such as expansion of omics (such as genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics), using multisource study populations, environmental genomics, and systems biology to organically integrate findings and improve our understanding of myopia development in a quantitative way via big data analytics (i.e., combining multi-omics and other approaches with deep learning or artificial intelligence). Expanding our knowledge of pathologic mechanisms and ability to pinpoint at-risk individuals will lead to new therapeutic options, better patient management, and, ultimately, prevention of complications and visual impairment from myopia.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all CREAM study participants, their relatives, and the staff at the recruitment centers for their invaluable contributions.

Supported by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union's Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme (grant 648268); the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO, grant 91815655 and grant 91617076); the National Eye Institute (grant R01EY020483); Oogfonds; ODAS; and Uitzicht (grant 2017-28; Oogfonds; Landelijke Stichting voor Blinden en Slechtzienden; MaculaFonds). The International Myopia Institute provided funds to cover publication costs.

M.S. Tedja, None; A.E.G. Haarman, None; M.A. Meester-Smoor, None; J. Kaprio, None; D.A. Mackey, None; J.A. Guggenheim, None; C.J. Hammond, None; V.J.M. Verhoeven, None; C.C.W. Klaver, Bayer (C), Novartis (C), Optos (C), Topcon (F), Thea Pharma (C)

Appendix

The CREAM Consortium

Joan E. Bailey-Wilson,1 Paul Nigel Baird,2 Amutha Barathi Veluchamy,3–5 Ginevra Biino,6 Kathryn P. Burdon,7 Harry Campbell,8 Li Jia Chen,9 Ching-Yu Cheng,10–12 Emily Y. Chew,13 Jamie E. Craig,14 Phillippa M. Cumberland,15 Margaret M. Deangelis,16 Cécile Delcourt,17 Xiaohu Ding,18 Cornelia M. van Duijn,19 David M. Evans,20–22 Qiao Fan,23 Maurizio Fossarello,24 Paul J. Foster,25 Puya Gharahkhani,26 Adriana I. Iglesias,19,27,28 Jeremy A. Guggenheim,29 Xiaobo Guo1,8,30 Annechien E. G. Haarman,19,28 Toomas Haller,31 Christopher J. Hammond,32 Xikun Han,26 Caroline Hayward,33 Mingguang He,2,18 Alex W. Hewitt,2,7,34 Quan Hoang,3,35 Pirro G. Hysi,32 Robert P. Igo Jr.,36 Sudha K. Iyengar,36–38 Jost B. Jonas,39,40 Mika Kähönen,41,42 Jaakko Kaprio,43,44 Anthony P. Khawaja,25,45 Caroline C. W. Klaver,19,28,46 Barbara E. Klein,47 Ronald Klein,47 Jonathan H. Lass,36,37 Kris Lee,47 Terho Lehtimäki,48,49 Deyana Lewis,1 Qing Li,50 Shi-Ming Li,40 Leo-Pekka Lyytikäinen,48,49 Stuart MacGregor,26 David A. Mackey,2,7,34 Nicholas G. Martin,51 Akira Meguro,52 Andres Metspalu,31 Candace Middlebrooks, Masahiro Miyake,53 Nobuhisa Mizuki,52 Anthony Musolf,1 Stefan Nickels,54 Konrad Oexle,55 Chi Pui Pang,9 Olavi Pärssinen,56,57 Andrew D. Paterson,58 Norbert Pfeiffer,54 Ozren Polasek,59,60 Jugnoo S. Rahi,1,5,25,61 Olli Raitakari,62,63 Igor Rudan,8 Srujana Sahebjada,2 Seang-Mei Saw,64,65 Dwight Stambolian,66 Claire L. Simpson,1,67 E-Shyong Tai,65 Milly S. Tedja,19,28 J. Willem L. Tideman,19,28 Akitaka Tsujikawa,53 Virginie J. M. Verhoeven,19,27,28 Veronique Vitart,33 Ningli Wang,40 Juho Wedenoja,43,68 Wen Bin Wei,69 Cathy Williams,22 Katie M. Williams,32 James F. Wilson,8,33 Robert Wojciechowski1,70,71 Ya Xing Wang,40 Kenji Yamashiro,72 Jason C. S. Yam,9 Maurice K. H. Yap,73 Seyhan Yazar,34 Shea Ping Yip,74 Terri L. Young,47 Xiangtian Zhou75

1Computational and Statistical Genomics Branch, National Human Genome Research Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, United States

2Centre for Eye Research Australia, Ophthalmology, Department of Surgery, University of Melbourne, Royal Victorian Eye and Ear Hospital, Melbourne, Australia

3Singapore Eye Research Institute, Singapore National Eye Centre, Singapore

4DUKE-NUS Medical School, Singapore, Singapore

5Department of Ophthalmology, National University Health Systems, National University of Singapore, Singapore

6Institute of Molecular Genetics, National Research Council of Italy, Pavia, Italy

7Department of Ophthalmology, Menzies Institute of Medical Research, University of Tasmania, Hobart, Australia

8Centre for Global Health Research, Usher Institute for Population Health Sciences and Informatics, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, United Kingdom

9Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong Eye Hospital, Kowloon, Hong Kong

10Department of Ophthalmology, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore

11Ocular Epidemiology Research Group, Singapore Eye Research Institute, Singapore National Eye Centre, Singapore

12Ophthalmology & Visual Sciences Academic Clinical Program (Eye ACP), DUKE-NUS Medical School, Singapore

13Division of Epidemiology and Clinical Applications, National Eye Institute/National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, United States

14Department of Ophthalmology, Flinders University, Adelaide, Australia

15Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health, University College London, London, United Kingdom

16Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, John Moran Eye Center, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah, United States

17Université de Bordeaux, INSERM, Bordeaux Population Health Research Center, Team LEHA, UMR 1219, F-33000 Bordeaux, France

18State Key Laboratory of Ophthalmology, Zhongshan Ophthalmic Center, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, China

19Department of Epidemiology, Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, The Netherlands

20Translational Research Institute, University of Queensland Diamantina Institute, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia

21MRC Integrative Epidemiology Unit, University of Bristol, Bristol, United Kingdom

22Department of Population Health Sciences, Bristol Medical School, Bristol, United Kingdom

23Centre for Quantitative Medicine, DUKE-National University of Singapore, Singapore

24University Hospital ‘San Giovanni di Dio,' Cagliari, Italy

25NIHR Biomedical Research Centre, Moorfields Eye Hospital NHS Foundation Trust and UCL Institute of Ophthalmology, London, United Kingdom

26Statistical Genetics, QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute, Brisbane, Australia

27Department of Clinical Genetics, Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Netherlands

28Department of Ophthalmology, Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Netherlands

29School of Optometry & Vision Sciences, Cardiff University, Cardiff, United Kingdom

30Department of Statistical Science, School of Mathematics, Sun Yat-Sen University, Guangzhou, China

31Institute of Genomics, University of Tartu, Tartu, Estonia

32Section of Academic Ophthalmology, School of Life Course Sciences, King's College London, London, United Kingdom

33MRC Human Genetics Unit, MRC Institute of Genetics & Molecular Medicine, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, United Kingdom

34Centre for Ophthalmology and Visual Science, Lions Eye Institute, University of Western Australia, Perth, Australia

35Department of Ophthalmology, Columbia University, New York, United States

36Department of Population and Quantitative Health Sciences, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio, United States

37Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, Case Western Reserve University and University Hospitals Eye Institute, Cleveland, Ohio, United States

38Department of Genetics, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio, United States

39Department of Ophthalmology, Medical Faculty Mannheim of the Ruprecht-Karls-University of Heidelberg, Mannheim, Germany

40Beijing Tongren Eye Center, Beijing Tongren Hospital, Beijing Institute of Ophthalmology, Beijing Key Laboratory of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, Capital Medical University, Beijing, China

41Department of Clinical Physiology, Tampere University Hospital and School of Medicine, University of Tampere, Tampere, Finland

42Finnish Cardiovascular Research Center, Faculty of Medicine and Life Sciences, University of Tampere, Tampere, Finland

43Department of Public Health, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland

44Institute for Molecular Medicine Finland FIMM, HiLIFE Unit, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland

45Department of Public Health and Primary Care, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, United Kingdom

46Department of Ophthalmology, Radboud University Medical Center, Nijmegen, the Netherlands

47Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin, United States

48Department of Clinical Chemistry, Finnish Cardiovascular Research Center-Tampere, Faculty of Medicine and Life Sciences, University of Tampere, Tampere, Finland

49Department of Clinical Chemistry, Fimlab Laboratories, University of Tampere, Tampere, Finland

50National Human Genome Research Institute, National Institutes of Health, Baltimore, Maryland, United States

51Genetic Epidemiology, QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute, Brisbane, Australia

52Department of Ophthalmology, Yokohama City University School of Medicine, Yokohama, Kanagawa, Japan

53Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, Kyoto University Graduate School of Medicine, Kyoto, Japan

54Department of Ophthalmology, University Medical Center of the Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz, Mainz, Germany

55Institute of Neurogenomics, Helmholtz Zentrum München, German Research Centre for Environmental Health, Neuherberg, Germany

56Department of Ophthalmology, Central Hospital of Central Finland, Jyväskylä, Finland

57Gerontology Research Center, Faculty of Sport and Health Sciences, University of Jyväskylä, Jyväskylä, Finland

58Program in Genetics and Genome Biology, Hospital for Sick Children and University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

59Gen-info Ltd, Zagreb, Croatia

60University of Split School of Medicine, Soltanska 2, Split, Croatia

61Ulverscroft Vision Research Group, University College London, London, United Kingdom

62Research Centre of Applied and Preventive Cardiovascular Medicine, University of Turku, Turku, Finland

63Department of Clinical Physiology and Nuclear Medicine, Turku University Hospital, Turku, Finland

64Myopia Research Group, Singapore Eye Research Institute, Singapore National Eye Centre, Singapore

65Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health, National University Health Systems, National University of Singapore, Singapore

66Department of Ophthalmology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States

67Department of Genetics, Genomics and Informatics, University of Tennessee Health Sciences Center, Memphis, Tennessee, United States

68Department of Ophthalmology, University of Helsinki and Helsinki University Hospital, Helsinki, Finland

69Beijing Tongren Eye Center, Beijing Key Laboratory of Intraocular Tumor Diagnosis and Treatment, Beijing Ophthalmology & Visual Sciences Key Lab, Beijing Tongren Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing, China

70Department of Epidemiology and Medicine, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, Maryland, United States

71Wilmer Eye Institute, Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions, Baltimore, Maryland, United States

72Department of Ophthalmology, Otsu Red Cross Hospital, Nagara, Japan

73Centre for Myopia Research, School of Optometry, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong

74Department of Health Technology and Informatics, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong

75School of Ophthalmology and Optometry, Eye Hospital, Wenzhou Medical University, China

References

- 1.Guggenheim JA. The heritability of high myopia: a reanalysis of Goldschmidt's data. J Med Genet. 2000;37:227–231. doi: 10.1136/jmg.37.3.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sorsby A, Sheridan M, Leary GA. Medical Research Council, Special Report Series No. 303. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office;; 1962. Refraction and its components in twins. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lin LL, Chen CJ. A twin study on myopia in Chinese school children. Acta Ophthalmol Suppl. 1988;185:51–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1988.tb02662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wojciechowski R, Congdon N, Bowie H, Munoz B, Gilbert D, West SK. Heritability of refractive error and familial aggregation of myopia in an elderly American population. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:1588–1592. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Teikari JM, Kaprio J, Koskenvuo MK, Vannas A. Heritability estimate for refractive errors—a population-based sample of adult twins. Genet Epidemiol. 1988;5:171–181. doi: 10.1002/gepi.1370050304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dirani M, Chamberlain M, Shekar SN, et al. Heritability of refractive error and ocular biometrics: the Genes in Myopia (GEM) twin study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:4756–4761. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lyhne N, Sjølie AK, Kyvik KO, Green A. The importance of genes and environment for ocular refraction and its determiners: a population based study among 20–45 year old twins. Br J Ophthalmol. 2001;85:1470–1476. doi: 10.1136/bjo.85.12.1470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sanfilippo PG, Hewitt AW, Hammond CJ, Mackey DA. The heritability of ocular traits. Surv Ophthalmol. 2010;55:561–583. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Young FA, Leary GA, Baldwin WR, et al. The transmission of refractive errors within Eskimo families. Am J Optom Arch Am Acad Optom. 1969;46:676–685. doi: 10.1097/00006324-196909000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Angi MR, Clementi M, Sardei C, Piattelli E, Bisantis C. Heritability of myopic refractive errors in identical and fraternal twins. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1993;231:580–585. doi: 10.1007/BF00936522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lopes MC, Andrew T, Carbonaro F, Spector TD, Hammond CJ. Estimating heritability and shared environmental effects for refractive error in twin and family studies. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:126–131. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stambolian D. Genetic susceptibility and mechanisms for refractive error. Clin Genet. 2013;84:102–108. doi: 10.1111/cge.12180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cordell HJ, Clayton DG. Genetic association studies. Lancet. 2005;366:1121–1131. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67424-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ku CS, Loy EY, Pawitan Y, Chia KS. The pursuit of genome-wide association studies: where are we now? J Hum Genet. 2010;55:195–206. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2010.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li J, Zhang Q. Insight into the molecular genetics of myopia. Mol Vis. 2017;23:1048–1080. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duke-Elder SS. The Practice of Refraction. London: Churchill;; 1943. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meng W, Butterworth J, Malecaze F, Calvas P. Axial length of myopia: a review of current research. Ophthalmologica. 2011;225:127–134. doi: 10.1159/000317072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim MH, Zhao D, Kim W, et al. Heritability of myopia and ocular biometrics in Koreans: the healthy twin study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54:3644–3649. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-11254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klein AP, Suktitipat B, Duggal P, et al. Heritability analysis of spherical equivalent, axial length, corneal curvature, and anterior chamber depth in the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127:649–655. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guggenheim JA, Zhou X, Evans DM, et al. Coordinated genetic scaling of the human eye: shared determination of axial eye length and corneal curvature. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54:1715–1721. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-10560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hammond CJ, Snieder H, Gilbert CE, Spector TD. Genes and environment in refractive error: the Twin Eye Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:1232–1236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen CY-C, Scurrah KJ, Stankovich J, et al. Heritability and shared environment estimates for myopia and associated ocular biometric traits: the Genes in Myopia (GEM) family study. Hum Genet. 2007;121:511–520. doi: 10.1007/s00439-006-0312-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guggenheim JA, St. Pourcain B, McMahon G, Timpson NJ, Evans DM, Williams C. Assumption-free estimation of the genetic contribution to refractive error across childhood. Mol Vis. 2015;21:621–632. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tedja MS, Wojciechowski R, Hysi PG, et al. Genome-wide association meta-analysis highlights light-induced signaling as a driver for refractive error. Nat Genet. 2018;50:834–848. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0127-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rose KA, Morgan IG, Smith W, Mitchell P. High heritability of myopia does not preclude rapid changes in prevalence. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2002;30:168–172. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-9071.2002.00521.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wojciechowski R. Nature and nurture: the complex genetics of myopia and refractive error. Clin Genet. 2011;79:301–320. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2010.01592.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dawn Teare M, Barrett JH. Genetic linkage studies. Lancet. 2005;366:1036–1044. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67382-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baird PN, Schäche M, Dirani M. The GEnes in Myopia (GEM) study in understanding the aetiology of refractive errors. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2010;29:520–542. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hornbeak DM, Young TL. Myopia genetics: a review of current research and emerging trends. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2009;20:356–362. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e32832f8040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jacobi FK, Pusch CM. A decade in search of myopia genes. Front Biosci. 2010;15:359–372. doi: 10.2741/3625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang Q, Guo X, Xiao X, Jia X, Li S, Hejtmancik JF. A new locus for autosomal dominant high myopia maps to 4q22-q27 between D4S1578 and D4S1612. Mol Vis. 2005;11:554–560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Young TL, Ronan SM, Alvear AB, et al. A second locus for familial high myopia maps to chromosome 12q. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;63:1419–1424. doi: 10.1086/302111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Naiglin L, Gazagne C, Dallongeville F, et al. A genome wide scan for familial high myopia suggests a novel locus on chromosome 7q36. J Med Genet. 2002;39:118–124. doi: 10.1136/jmg.39.2.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paluru P, Ronan SM, Heon E, et al. New locus for autosomal dominant high myopia maps to the long arm of chromosome 17. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:1830–1836. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-0697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nallasamy S, Paluru PC, Devoto M, Wasserman NF, Zhou J, Young TL. Genetic linkage study of high-grade myopia in a Hutterite population from South Dakota. Mol Vis. 2007;13:229–236. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lam CY, Tam POS, Fan DSP, et al. A genome-wide scan maps a novel high myopia locus to 5p15. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:3768–3778. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hawthorne FA, Young TL. Genetic contributions to myopic refractive error: insights from human studies and supporting evidence from animal models. Exp Eye Res. 2013;114:141–149. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2012.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stambolian D, Ibay G, Reider L, et al. Genomewide linkage scan for myopia susceptibility loci among Ashkenazi Jewish families shows evidence of linkage on chromosome 22q12. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75:448–459. doi: 10.1086/423789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wojciechowski R, Moy C, Ciner E, et al. Genomewide scan in Ashkenazi Jewish families demonstrates evidence of linkage of ocular refraction to a QTL on chromosome 1p36. Hum Genet. 2006;119:389–399. doi: 10.1007/s00439-006-0153-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wojciechowski R, Stambolian D, Ciner E, Ibay G, Holmes TN, Bailey-Wilson JE. Genomewide linkage scans for ocular refraction and meta-analysis of four populations in the Myopia Family Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:2024–2032. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hammond CJ, Andrew T, Mak YT, Spector TD. A susceptibility locus for myopia in the normal population is linked to the PAX6 gene region on chromosome 11: a genomewide scan of dizygotic twins. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75:294–304. doi: 10.1086/423148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ciner E, Ibay G, Wojciechowski R, et al. Genome-wide scan of African-American and white families for linkage to myopia. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;147:512–517.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.John Hopkins University. Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) 2018 Available at: https://www.omim.org/ Accessed June 27.

- 44.National Center for Biotechnology Information. Genes. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/ Accessed September 11. 2018

- 45.Hendriks M, Verhoeven VJM, Buitendijk GHS, et al. Development of refractive errors—what can we learn from inherited retinal dystrophies? Am J Ophthalmol. 2017;182:81–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2017.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mutti DO, Cooper ME, O'Brien S, et al. Candidate gene and locus analysis of myopia. Mol Vis. 2007;13:1012–1019. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Metlapally R, Li Y-J, Tran-Viet K-N, et al. COL1A1 and COL2A1 genes and myopia susceptibility: evidence of association and suggestive linkage to the COL2A1 locus. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:4080–4086. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-3346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fan Q, Verhoeven VJM, Wojciechowski R, et al. Meta-analysis of gene-environment-wide association scans accounting for education level identifies additional loci for refractive error. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11008. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Flitcroft DI, Loughman J, Wildsoet CF, Williams C, Guggenheim JA;, for the CREAM Consortium Novel myopia genes and pathways identified from syndromic forms of myopia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2018;59:338–348. doi: 10.1167/iovs.17-22173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lin H-J, Wan L, Tsai Y, et al. The TGFβ1 gene codon 10 polymorphism contributes to the genetic predisposition to high myopia. Mol Vis. 2006;12:698–703. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lin H-J, Wan L, Tsai Y, et al. Sclera-related gene polymorphisms in high myopia. Mol Vis. 2009;15:1655–1663. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lam DSC, Lee WS, Leung YF, et al. TGFbeta-induced factor: a candidate gene for high myopia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:1012–1015. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Veerappan S, Pertile KK, Islam AFM, et al. Role of the hepatocyte growth factor gene in refractive error. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:239–245. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Han W, Yap MKH, Wang J, Yip SP. Family-based association analysis of hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) gene polymorphisms in high myopia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:2291–2299. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Khor CC, Grignani R, Ng DPK, et al. cMET and refractive error progression in children. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:1469–1474. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Khor CC, Fan Q, Goh L, et al. Support for TGFB1 as a susceptibility gene for high myopia in individuals of Chinese descent. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128:1081–1084. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2010.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Metlapally R, Ki C-S, Li Y-J, et al. Genetic association of insulin-like growth factor-1 polymorphisms with high-grade myopia in an international family cohort. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:4476–4479. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-4912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hall NF, Gale CR, Ye S, Martyn CN. Myopia and polymorphisms in genes for matrix metalloproteinases. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:2632–2636. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wojciechowski R, Yee SS, Simpson CL, Bailey-Wilson JE, Stambolian D. Matrix metalloproteinases and educational attainment in refractive error: evidence of gene-environment interactions in the Age-Related Eye Disease Study. Ophthalmology. 2013;120:298–305. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.07.078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang I-J, Chiang T-H, Shih Y-F, et al. The association of single nucleotide polymorphisms in the 5′-regulatory region of the lumican gene with susceptibility to high myopia in Taiwan. Mol Vis. 2006;12:852–857. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chen K-C, Hsi E, Hu C-Y, Chou W-W, Liang C-L, Juo S-HH. MicroRNA-328 may influence myopia development by mediating the PAX6 gene. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53:2732–2739. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-9272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ioannidis JP, Ntzani EE, Trikalinos TA, Contopoulos-Ioannidis DG. Replication validity of genetic association studies. Nat Genet. 2001;29:306–309. doi: 10.1038/ng749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tang SM, Rong SS, Young AL, Tam POS, Pang CP, Chen LJ. PAX6 gene associated with high myopia: a meta-analysis. Optom Vis Sci. 2014;91:419–429. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0000000000000224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li M, Zhai L, Zeng S, et al. Lack of association between LUM rs3759223 polymorphism and high myopia. Optom Vis Sci. 2014;91:707–712. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0000000000000302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang D, Zeng G, Hu J, McCormick K, Shi Y, Gong B. Association of IGF1 polymorphism rs6214 with high myopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmic Genet. 2017;38:434–439. doi: 10.1080/13816810.2016.1253105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dewan A, Liu M, Hartman S, et al. HTRA1 promoter polymorphism in wet age-related macular degeneration. Science. 2006;314:989–992. doi: 10.1126/science.1133807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Park J-H, Wacholder S, Gail MH, et al. Estimation of effect size distribution from genome-wide association studies and implications for future discoveries. Nat Genet. 2010;42:570–575. doi: 10.1038/ng.610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nakanishi H, Yamada R, Gotoh N, et al. A genome-wide association analysis identified a novel susceptible locus for pathological myopia at 11q24.1. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000660. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Li Y-J, Goh L, Khor C-C, et al. Genome-wide association studies reveal genetic variants in CTNND2 for high myopia in Singapore Chinese. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:368–375. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Liu J, Zhang H-X. Polymorphism in the 11q24.1 genomic region is associated with myopia: a comprehensive genetic study in Chinese and Japanese populations. Mol Vis. 2014;20:352–358. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]