Abstract

Background & Aims

Patterns of genetic alterations characterize different molecular subtypes of human gastric cancer. We aimed to establish mouse models of these subtypes.

Methods

We searched databases to identify genes with unique expression in the stomach epithelium, resulting in the identification of Anxa10. We generated mice with tamoxifen-inducible Cre recombinase (CreERT2) in the Anxa10 gene locus. We created 3 mouse models with alterations in pathways that characterize the chromosomal instability (CIN) and the genomically stable (GS) subtypes of human gastric cancer: Anxa10-CreERT2;KrasG12D/+;Tp53R172H/+;Smad4fl/f (CIN mice), Anxa10-CreERT2;Cdh1fl/fl;KrasG12D/+;Smad4fl/fl (GS-TGBF mice), and Anxa10-CreERT2;Cdh1fl/fl;KrasG12D/+;Apcfl/fl (GS-Wnt mice). We analyzed tumors that developed in these mice by histology for cell types and metastatic potential. We derived organoids from the tumors and tested their response to chemotherapeutic agents and the epithelial growth factor receptor signaling pathway inhibitor trametinib.

Results

The gastric tumors from the CIN mice had an invasive phenotype and formed liver and lung metastases. The tumor cells had a glandular morphology, similar to human intestinal-type gastric cancer. The gastric tumors from the GS–TGFB mice were poorly differentiated with diffuse morphology and signet ring cells, resembling human diffuse-type gastric cancer. Cells from these tumors were invasive, and mice developed peritoneal carcinomatosis and lung metastases. GS-Wnt mice developed adenomatous tooth-like gastric cancer. Organoids derived from tumors of GS-TGBF and GS-Wnt mice were more resistant to docetaxel, whereas organoids from the CIN tumors were more resistant to trametinib.

Conclusions

Using a stomach-specific CreERT2 system, we created mice that develop tumors with morphologic similarities to subtypes of human gastric cancer. These tumors have different patterns of local growth, metastasis, and response to therapeutic agents. They can be used to study different subtypes of human gastric cancer.

Keywords: Stomach Cancer, Cre/loxP System, Carcinogenesis, Targeted Therapy

Abbreviations used in this paper: 5-FU, 5-fluoruracil; CIN, chromosomal instability; EGF, epidermal growth factor; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; EMT, epithelial to mesenchymal transition; ERK, extracellular signal–regulated kinase; GS, genomically stable; IHC, immunohistochemistry; MEK, mitogen-activated extracellular signal-regulated kinases; mRNA, messenger RNA; MSI, microsatellite instable; PAS, periodic acid–Schiff; PGC, pepsinogen C; PI, propidium iodide; p.i., post induction; PI3K, phosphoinositide 3-kinase; RTK, receptor tyrosine kinase; TGF, transforming growth factor; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas

Graphical abstract

See Covering the Cover synopsis on page 1446.

What You Need to Know.

Background and Context

There are different molecular subtypes of human gastric cancer characterized by patterns of genetic alterations. We aimed to establish mouse models for these different subtypes.

New Findings

We used an inducible Cre recombinase to alter genes and create mouse models that developed different subtypes of human gastric cancer. These tumors had morphologic similarities to human gastric cancers — the subtypes had different patterns of local growth, metastasis, and response to therapeutic agents.

Limitations

This study was performed in mice. Certain features of the tumors identified in these mice will require confirmation in patients.

Impact

These mouse models can be used to study different subtypes of human gastric cancer and the mechanisms of their response to treatment.

Gastric cancer ranks as the fifth most common malignancy and the second leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide.1 Additionally, adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction represents a cancer entity with rising incidence that is molecularly indistinguishable from gastric cancer.2, 3, 4 Because of the lack of early clinical signs, the diagnosis of gastric cancer is often delayed, resulting in many patients presenting with incurable disease.5 Currently, surgery is the only curative option. In recent years, increased survival rates has been achieved, especially by adding neoadjuvant chemotherapy to treatment algorithms.6,7 Although complete pathologic regression rates can sometimes be reached with modern chemotherapeutic combination regiments, such as 16% with FLOT (ie, 5-fluorouracil [5-FU], folic acid, oxaliplatin, docetaxel),8 not all patients show tumor regression after neoadjuvant treatment. Genome sequencing and response testing in patient-derived organoid cell cultures might constitute a promising way to individualize gastric cancer treatment.9, 10, 11, 12

Although the World Health Organization classifies gastric cancer into 4 main subtypes of adenocarcinoma, the widely used Lauren classification divides gastric cancer into intestinal, diffuse, and intermediate types.13 The intestinal type is characterized by a glandular morphology of cancer cells and is regularly associated with hematopoietic dissemination (eg, to the liver), whereas the diffuse type often shows widespread infiltration of tumor cells in surrounding tissue and has a preference to metastasize to the peritoneum. Recently, The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) study developed a robust classification system for gastric adenocarcinoma based on different mutational signatures.14 Deregulated pathways and candidate drivers for 4 molecular subtypes were identified: the first group of tumors is characterized by an Epstein-Barr virus infection and, thus, is called the Epstein-Barr virus–positive subtype. These tumors are often located in the gastric corpus, show a widespread hypermethylation of promotor regions, and carry mutations in PIK3CA and ARID1A. This subtype is mainly found in Asia and is very rare in the West. The second subtype shows a high frequency for microsatellite instability (MSI) and therefore is known as the MSI subtype. Typical for this subtype is the hypermethylation or mutation of DNA damage repair genes, which results in elevated mutation rates. MSI cancers often carry thousands of mutations with a high number of frequently mutated genes. The genomically stable (GS) and chromosomal instability (CIN) subtype can be distinguished by the presence or absence of somatic copy number aberrations. The GS subtype often shows a diffuse morphology due to the frequent loss of cell adhesion molecules such as CDH1. Finally, the CIN subtype is characterized by TP53 mutations and genomic amplifications of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs), resulting in the activation of the RAS pathway. The CIN and GS subtypes harbor a limited number of frequent mutations, which makes them amenable to genetic modelling.

Genetically engineered mouse models have led to an enormous increase in knowledge about tumor initiation, development, and metastatic spread.15 They still represent the best model system to study in vivo tumor cell interactions with the microenvironment, tumor angiogenesis, or the role of the immune system. Sophisticated mouse models have been established for several cancer entities based on the Cre or Flp recombination system.16 For gastric cancer, no advanced model exists that comprises several mutations frequently found in human disease and initiates tumors only in the stomach.17 This is mainly due to the lack of a known suitable promoter for Cre recombinase expression.

In this study, we established genetically engineered mouse models of the CIN and GS gastric cancer molecular subtypes as defined by the TCGA by use of a novel stomach-specific CreERT2 recombinase–expressing mouse line.

Materials and Methods

Mice

To generate the inducible Anxa10-CreERT2 mice, an IRES-CreERT2 was inserted after the stop codon of the last exon (12) of the Anxa10 gene plus a PGK-Neo cassette flanked by FRT sites (Figure 1B). The line was generated by Ozgene (Bentley, Australia). The targeting construct was electroporated into a C57BL/6 ES cell line. Homologous recombinant ES cell clones were identified by Southern hybridization and injected into blastocysts. Male chimeric mice were obtained and crossed to C57BL/6 females to establish heterozygous germline offspring on a C57BL/6 background. Mice with germline transmission were crossed to a ubiquitous FLP C57BL/6 mouse line (Gt[ROSA]26Sortm1(FLP1)Dym) to remove the FRT-flanked PGK-Neo cassette. Next, functionality was tested by crossing Anxa10-CreERT2 mice to the Rosa26-LSL-LacZ (Gt[ROSA]26Sor) Cre reporter line and staining of tissues with LacZ (Figure 1C and Supplementary Figure 1B). In addition, we performed double immunofluorescence stainings on a cross of the Anxa10-CreERT2 mice with the fluorescent reporter line Rosa26-LSL-ZsGreen (Gt[ROSA]26Sortm6(CAG-ZsGreen1)Hze) (Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

Anxa10-CreERT2: a stomach-specific inducible Cre line. (A) IHC of ANXA10 on mouse stomach. Scale bar, 100 μm. (B) Knock-in strategy. An IRES-CreERT2 cassette including a Neo resistance was inserted after exon 12 via homologous recombination. (C) Expression of LacZ in Anxa10-CreERT2;Rosa26-LSL-LacZ mice in stomach epithelium 48 hours after Cre induction. Scale bar, 100 μm. (D) Immunofluorescence stainings for lineage markers on induced Anxa10-CreERT2;Rosa26-LSL-ZsGreen mice. Scale bar, 50 μm. E, exon; UTR, untranslated region.

To model the CIN subtype, the Anxa10-CreERT2 line was crossed to mice carrying the alleles KrasG12D/+ (Krastm4Tyj), Tp53R172H/+ (Tp53tm2Tyj), and Smad4fl/fl (Smad4tm2.1Cxd).18, 19, 20 Two different models for the GS subtype were generated. The Anxa10-CreERT2 mouse was crossed, on the one hand, with mice carrying the KrasG12D/+, Cdh1fl/fl (Cdh1tm2Kem), and Smad4fl/fl alleles21 and, on the other hand, with mice carrying the KrasG12D/+;Cdh1fl/fl and Apcfl/fl (Apctm2Rak) alleles.22 Mouse experiments were approved by the local animal welfare committee (TVA DD24-9168.11-1_2013-45 and DD24.1-5131/394/44).

Tamoxifen Administration and Mouse Tissue Preparation

To induce Cre recombination, 5 mg tamoxifen (Sigma-Aldrich) diluted in 100 μL sunflower oil was injected intraperitoneally in adult (minimum of 8 weeks of age) female and male mice. Control mice were siblings and received sunflower oil intraperitoneally only. To test for possible adverse effects of tamoxifen application to the stomach epithelium,23, 24, 25, 26 Anxa10-CreERT2 mice and the 2 mouse models were intraperitoneally injected 1 time with 5 mg tamoxifen and analyzed 48 hours after application. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) for parietal cells (vascular endothelial growth factor β) and proliferating cells (KI67) as well as quantitative polymerase chain reaction were performed (Supplementary Figure 2A–C).

Mice were fed with normal chow and water ad libitum, continuously monitored, and killed at different predetermined time points or immediately when showing signs of tumor burden. Lung, liver, lymph nodes, and half of the stomach were fixed overnight in 4% formaldehyde and then paraffin embedded. The rest of the stomach was used for organoid generation and DNA, RNA, and protein isolation.

Tumor Staging

The pathologic classification and staging were determined independently by 2 board-certified pathologists (YTC, DEA) according to specified morphologic criteria (Supplementary Table 1).

Mouse Gastric Cancer Organoid Cultivation and Treatment

Mouse cancer organoids were generated from the different subtypes at different time points of in vivo tumor formation, essentially as described earlier.27 Selection of successfully recombined organoids from nonrecombined normal tissue was performed by withdrawal of medium components depending on the specific mutations present in the subtype. Organoids carrying the KrasG12D/+ allele were selected via growth medium without epidermal growth factor (EGF). Smad4fl/fl organoids were cultured without Noggin. The recombined Apcfl/fl allele was selected by withdrawal of WNT and Rspondin from the medium. Selection of correctly recombined organoids was confirmed by genotyping.

Mouse gastric cancer organoids were treated with conventional chemotherapeutics 5-FU (0.001, 0.01, 0.1, 1.0, 10.0, 50.0, and 100.0 mmol/L), oxaliplatin (0.01, 0.05, 0.1, 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, and 3.0 mmol/L), and docetaxel (0.001, 0.005, 0.01, 0.05, 0.1, 0.5, and 1.0 mmol/L) for 24–72 hours. For targeted treatment of organoids, the EGF signaling pathway was treated with the MEK1/2 inhibitor trametinib (0.001, 0.01, 0.1, 1.0, 10.0, 50.0, and 100.0 nmol/L) for 72 hours.

Statistical Analysis

The chemotherapy or small molecule organoid treatment was performed according to the following procedure: For each cancer model, 3 different organoid lines originating from different mice were used. Each organoid line was then analyzed in 3 independent experiments, and each concentration was analyzed in triplicates. All values per dose—that is, n = 3 (models) × 3 (lines) × 3 (replicates) = 27—were averaged, and the standard deviation calculated. Repeated-measures analysis of variance using the R packages lme4 and emmeans were applied to analyze the differences among the 3 cancer subtypes in the dose response curves. Statistical differences in proliferation rate and of apoptotic cells were determined using the Student t-est. Graphs were generated with Prism (GraphPad 5.01; GraphPad, La Jolla, CA).

Additional information can be found in the Supplementary Materials.

Results

Generation of the Anxa10-CreERT2 Mouse Line for Stomach-Specific Gene Targeting

To manipulate gastric cancer–specific genes exclusively in the stomach epithelium in a timely controlled manner with the Cre/LoxP technology, a CreERT2-expressing mouse line with ubiquitous expression in all gastric cell types was needed. Several Cre mouse lines exist that have been used successfully for genetic manipulation of the stomach epithelium, but they are either not stomach specific (eg, K19-Cre, Tff1-Cre) or show cell-type specificity (eg, Atp4b-Cre, Capn8-Cre, Mist1-CreERT2).28, 29, 30, 31 We therefore set out to generate such a CreERT2 mouse strain in line with similar strains, such as the Villin-CreERT2 mouse, for intestinal research.32 Systematic screening of several mouse tissue gene expression databases, including Gene Expression Omnibus, MGI-Mouse Gene Expression Database (GXD), and BioGPS for stomach-specific expression revealed a limited number of potential candidates. Further literature searches were performed to rule out cell type–specific expression (such as PGC for chief cells or ATB4P for parietal cells). One potential candidate, CLDN18, was found to be highly expressed in the lung as well as in the stomach; another, CAR9, was found to be abundant in the small and large intestine. Both genes were thus disregarded as useful candidates for stomach-specific Cre expression. Eventually, the Anxa10 gene passed all selection criteria and remained as the most promising candidate. ANXA10 belongs to the annexin family of calcium-dependent phospholipid-binding proteins. A clear role in the stomach epithelium has not yet been determined. IHC for ANXA10 showed a strong expression in the whole stomach gland (Figure 1A). Results for all other tissues were negative, except a slight but clear positivity within the glomerular capsule and the convoluted tubes of the kidney (Supplementary Figure 1A).

By using classical gene targeting by homologous embryonic stem cell recombination, an IRES-CreERT2 cassette was inserted downstream of the last Anxa10 exon (Figure 1B). To analyze the functionality of the generated mouse line, it was crossed to the Cre-reporter line Rosa26-LSL-LacZ. LacZ staining was performed, and among all tissues examined, only the corpus and antrum of the stomach stained positive, proving the correct function of the inserted CreERT2 recombinase and its stomach-specific expression. Expression was patchy but could be seen throughout the gland (Figure 1C). Within all other tissues, including the kidney, no LacZ positivity could be observed (Supplementary Figure 1B). Immunofluorescence double stainings for lineage markers on induced Rosa26-LSL-ZsGreen mice confirmed that all cell lineages of the stomach showed Cre activity, ruling out any cell-type specificity of ANXA10 expression (Figure 1D). The patchiness is likely the result of a rather low expression of the Anxa10 gene compared with highly expressed genes such as villin in the intestine. Because of the patchy expression, the newly established mouse line cannot recombine in all cells of the stomach at once. Nevertheless, the line constitutes an ideal tool to generate cancer, because in this case, widespread induction is not desirable, but rather a restricted induction in a few loci, mimicking human sporadic cancer initiation.

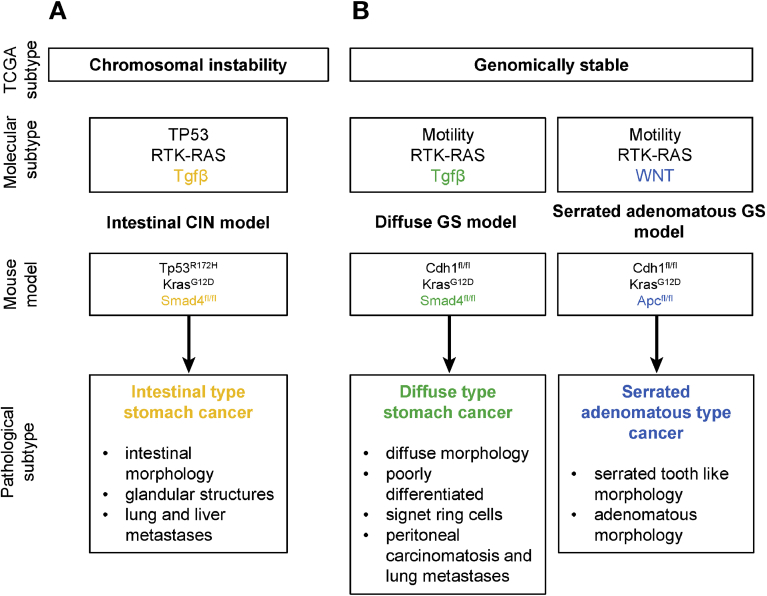

Definition of the Characteristic Genetic Alterations of Gastric Cancer Subtypes

To generate subtype-specific gastric cancer mouse models, we explored the TCGA data set and defined characteristic pathways altered within each molecular subtype using cBio portal.33,34 We chose to model the CIN and GS subtypes first and will address the Epstein-Barr virus and MSI subtypes in the future. For the CIN and GS subtypes, frequent mutations, expression changes, or genomic alterations were found in genes belonging to the RTK-RAS, phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K), WNT, TP53, transforming growth factor (TGF) β, cell motility, and chromatin remodeling pathways (Supplementary Table 2). For each pathway, a gene set was defined encompassing frequently altered genes. Mutations in these gene sets were called for each patient individually, and for the whole pathway per patient, a status was ascribed: altered or unaffected (Supplementary Table 2). Next, the percentage of patients with altered pathways per molecular subtype was calculated. The CIN subtype was characterized by a high percentage of patients with TP53 pathway alterations (120/147 cases, 82%) and activated RTK-RAS pathway (101/147 cases, 69%). In addition, we found the TGF-β (48%), WNT (29%), and PI3K (27%) to be frequently affected. The CIN pathway can therefore be modeled by combining alleles of the TP53 (Tp53R172H/+) and the RTK-RAS (KrasG12D/+) pathways as a basis with additional TGF-β, cell cycle, WNT, or PI3K pathway alterations. In addition, we chose to manipulate TGF-β signaling (by using a Smad4fl/fl allele) because it was the third most frequently affected pathway. The GS subtype was characterized by a high percentage of mutations in CDH1, CLDN18, and RHOA (35/58 cases, 60%), all 3 genes being associated with cell motility. In addition, the next top 3 pathways were TGF-β (53%), RTK-RAS (43%), and WNT (29%). We therefore decided to use a Cdh1fl/fl allele as the basic mutation in combination with either RTK-RAS plus TGF-β (Cdh1fl/fl;KrasG12D/+;Smad4fl/fl) or RTK-RAS plus WNT (Cdh1fl/fl;KrasG12D/+;Apcfl/fl) pathway alterations.

Chromosomal Instability Subtype Typical Alterations in the Receptor Tyrosine Kinase–RAS, TP53, and Transforming Growth Factor β Pathways Lead to Intestinal-Type Gastric Cancer

As described earlier, we combined the KrasG12D/+, Tp53R172H/+, and Smad4fl/fl alleles with the Anxa10-CreERT2 line to model the CIN gastric cancer subtype. Mice were monitored over a period of 12 weeks postinduction (p.i.); a longer observation was not possible because of the increasing tumor burden (Figure 2A).

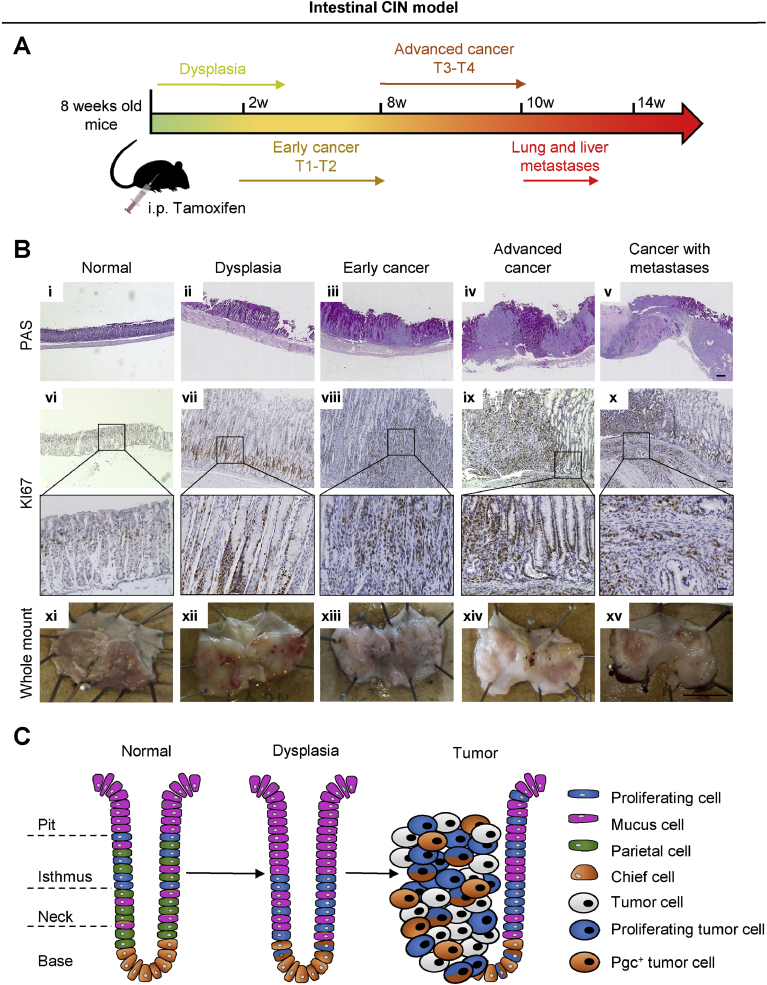

Figure 2.

Intestinal CIN model. (A) Timeline of the intestinal CIN gastric cancer model (Anxa10-CreERT2;KrasG12D;Tp53R172H;Smad4fl/fl). (B) PAS and KI67 staining and whole-mount pictures of mouse stomach at different stages of gastric cancer development. Scale bar i-v: 500 µm, vi-x: 50 µm, zoom in vi-x: 25 µm. (C) Sketch of the cell type distribution in tumors and surrounding dysplastic mucosa.

Histologic work up at 3 weeks p.i. showed dysplastic transformation of the epithelium (Figure 2Bii). Early T1/T2 cancer invading the submucosa and, further, the muscularis propria developed between weeks 2 and 8 p.i. (Figure 2Biii and Supplementary Figure 6). From weeks 8 to 10, p.i. tumor cells invaded the subserosa and advanced to T3/T4 cancer (Figure 2Biv and Supplementary Figure 6). Metastases in the lung and liver were found starting from 10 weeks p.i. onward (Figure 2Bv and Supplementary Figure 6). Detailed analysis of the different stomach-specific cell lineages showed pronounced changes in the normal glandular distribution of cell types. The dysplastic epithelium at 3 weeks showed a shift of proliferating Ki67 positive (Ki67+) cells from their normal location in the isthmus to the gland bottom (Figure 2Bvii). Interestingly, at the dysplastic gland bottom, we could document proliferative Pgc+ cells, a cell type that is usually quiescent (Supplementary Figure 5). An increase in mucus-producing cells within the stomach gland was detected by periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) staining (Figure 2Bii and Supplementary Figure 7B). A complete loss of parietal cells in the dysplastic epithelium was observed (Supplementary Figure 7L). Similar to the development of intestinal-type gastric cancer in humans, intestinal metaplasia as well as spasmolytic polypeptide-expressing metaplasia could be documented by CDX2 and TFF2 marker expression specifically in this model (Supplementary Figure 8). The early T1/T2 cancer displayed glandular morphology of tumor cells, with Pgc+ chief cell–like cells remaining at the gland bottoms, whereas parietal cells continued to be undetectable (Supplementary Figure 7 C, H, and M). Proliferating Ki67+ cells were spread throughout the tumor (Figure 2Bviii). The tumors became clearly visible in PAS staining, because tumors were mucus deprived compared with the surrounding dysplastic glands (Figure 2Biii). At 8 to 12 weeks p.i., advanced cancer developed an invasion of tumor cells into the subserosa (Figure 2Biv and Supplementary Figure 7D). Advanced tumors remained as a clearly separable structure delimited from dysplastic stomach glands in the vicinity (Figure 2Biv). Although in some tumor regions a glandular structure of tumor cells was observed, others developed into poorly differentiated cancer. The cell lineage composition and distribution remained comparable with that described for early T1/T2 cancer (Figure 2Bix and x and Supplementary Figure 7I–J, N, and O). Of note, Pgc+ chief cell–like cells continued to be present in advanced tumors, even in poorly differentiated areas (Supplementary Figure 7J). In addition, these Pgc+ chief cell–like cells were clearly proliferating (Supplementary Figure 5).

In summary, tumors caused by molecular aberrations typically found in the TCGA CIN subtype histologically recapitulated many features of intestinal-type cancer according to the Lauren classification (Figure 2C). We therefore refer to this mouse model as the intestinal CIN model from here on.

Genomically Stable Subtype Typical Alterations in the Cell Adhesion, Receptor Tyrosine Kinase–RAS and Transforming Growth Factor-β Pathways Result in Poorly Differentiated Signet Ring Cell Carcinoma

For modeling GS gastric cancer, we added a Cdh1fl/fl allele as a basic mutation to the Anxa10-CreERT2 mice. In the first GS model, we added the KrasG12D/+ and Smad4fl/fl alleles because of frequent mutations in the RTK-RAS and TGF-β pathway in this TCGA subtype (Supplementary Table 2). Mice were analyzed over a maximum period of 28 weeks p.i.; longer observation was not possible because of food refusal and weight loss (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Diffuse GS model. (A) Timeline of the diffuse GS gastric cancer model (Anxa10-CreERT2;Cdh1fl/fl;KrasG12D;Smad4fl/fl). (B) PAS and KI67 staining and whole-mount pictures of mouse stomach at different stages of cancer development. Scale bar i-iv: 500 µm, v-viii: 50 µm, zoom in v-viii: 25 µm. (C) Sketch of the cell-type distribution in tumors and surrounding dysplastic mucosa.

Already at week 1 p.i., T1 cancerous lesions were observed, followed by the progression toward T2 cancer until week 8 p.i., (Figure 3Bii and Supplementary Figure 6). Advanced cancer (T3/T4) was found afterward, and metastases were first detectable from week 16 p.i. onward (Figure 3Biii and iv and Supplementary Figure 6). The mutational setup in this GS model specifically led to lung metastases and peritoneal carcinomatosis. Interestingly, the number of metastases increased with time, but not the metastatic sites. Early cancer invading the muscularis propria represented a poorly differentiated tumor with signet ring cells (Supplementary Figure 9B). In addition, multiple in situ lesions with signet ring cells could be observed. A strong increase in the number of Ki67+ tumor cells was seen (Figure 3Bvi). Advanced tumors showed an invasion of tumor cells into the subserosa and serosa with a large number of proliferating Ki67+ cells (Figure 3Bvii and viii and Supplementary Figure 9C and D). The diffuse morphology was maintained with characteristic signet ring cells. However, some glandular structures were also found in the tumor mass (Supplementary Figure 9D). From early cancer onward, tumors showed no mucus production and can therefore be observed as PAS-negative masses between strongly PAS-positive dysplastic glands (Figure 3Bii–iv). Of note, Pgc+ chief cell–like cells persisted in early and advanced cancers, could be found in patches of tumor cells in invasive tumor parts, and were proliferating (Supplementary Figure 5 and 9F–H). Similar to the CIN model, parietal cells were absent from the T1/2 stage onward (Supplementary Figure 9J–L).

To summarize, in the GS model with TGF-ß pathway depletion, we observed histologically a poorly differentiated invasive and metastatic cancer with characteristic signet ring cells with remarkable similarities to the diffuse-type gastric cancer according to the Lauren classification (Figure 3C). Thus, this mouse model is called the diffuse GS model from here on.

Development of Serrated Adenomatous Gastric Cancer in Tumors With Aberrant Cell Adhesion, Receptor Tyrosine Kinase–RAS, and WNT Pathway

For the second GS gastric cancer subtype, Anxa10-CreERT2 mice were combined with Cdh1fl/fl, KrasG12D/+, and Apcfl/fl alleles (Figure 4A). Mice could be observed over a period of 25 weeks p.i.; from this point on, large tumor formations inside the lumen of the stomach lead to obstruction and cessation of food intake.

Figure 4.

Serrated adenomatous GS model. (A) Timeline of the serrated adenomatous GS gastric cancer model (Anxa10-CreERT2;Cdh1fl/f;KrasG12D;Apcfl/fl). (B) PAS and KI67 staining and whole-mount pictures of mouse stomach at different stages of cancer development. Scale bar i-iv: 500 µm, v-viii: 50 µm, zoom in v-viii: 25 µm. (C) Sketch of the cell-type distribution in tumors (no dysplastic mucosa left).

Until week 4 p.i., dysplastic epithelium was observed. Early cancer with T1a or T1b staging was found from 4 weeks p.i. onward (Figure 4A and Supplementary Figures 6 and 9B–D). Similar to our observations in the intestinal CIN and the diffuse GS model, Ki67+ cells shifted down to the gland base in the dysplastic epithelium, whereas Pgc+ chief cell–like cells remained unchanged (Figure 4Bvi and Supplementary Figure 10F). In contrast to the intestinal CIN and diffuse GS model, parietal cells remained present in the dysplastic epithelium (Supplementary Figure 10J). Only a weak increase in mucus production was observed (Figure 4Bii). Early cancer developed within the analyzable time span of 25 weeks PI with invasion into the lamina propria (T1a) and a maximum to the submucosa (T1b) (Figure 4Biii and iv and Supplementary Figure 6). Instead of further invasion into the muscularis propria, tumors started to form macroscopically large tumor masses inside the stomach lumen (Figure 4B). Microscopically, tumors formed adenomatous cancer including serrated tooth-like structures. In this GS model, the whole epithelium was transformed, contrasting our findings in the other 2 models, where tumors developed as clearly distinguishable structures within surrounding dysplastic epithelium (Supplementary Figure 10C and D). The presence of Ki67+ cells was observed throughout the whole tumor (Figure 4Bvii and 8). Similar observations were made for Pgc+ chief cell–like cells, while parietal cells were lost in the transition from dysplasia to cancer (Supplementary Figure 10G, H, K, L). Early cancer continued to produce low amounts of mucus (Figure 4Biii and vi). As in the other 2 models, Pgc+ chief cell–like cells were proliferating both in dysplastic epithelium and in cancer cells (Supplementary Figure 5).

Because of the characteristic morphologic observations, this model resembles the relatively newly described histologic subtype of serrated adenomatous gastric cancer (Figure 4C).35 We therefore refer to this mouse line as the serrated adenomatous GS model.

Divergent Metastatic Potential of the Intestinal Chromosomal Instability and Diffuse Genomically Stable Model

The intestinal CIN and the diffuse GS model showed metastatic potential, whereas no metastases were found in the adenomatous GS model. Interestingly, the 2 metastasizing models showed a different tropism of cancer cells to distant organs. Mice from the intestinal CIN model presented with macroscopically visible metastases in lung and liver. These metastases showed a glandular solid growth pattern with a similar tumor morphology as the primary cancer (Figure 5A-C). Expression of cytokeratin 20 (CK20), a marker of luminal gastrointestinal tissue normally not expressed in liver and lung, and gastric-epithelium–specific ANXA10 was detected in liver and lung metastases (Figure 5D–G). In contrast, the diffuse GS model showed lung metastases and peritoneal carcinomatosis with multifocal infiltration of signet ring cells and a diffuse morphology of tumor cells (Figure 5H–J), again confirmed by CK20 and ANXA10 stainings (Figure 5K–N).

Figure 5.

Divergent metastatic potential of the gastric cancer subtypes. (A) The intestinal CIN model showed metastatic spread to the liver and the lung. (B, C) H&E staining. (D, E) CK20 and (F, G) ANXA10 IHC. (H) In the GS model, metastases to the lung and peritoneum were observed. (I, J) H&E, (K, L) CK20, and (M, N) ANXA10 IHC. Scale bar, 50 μm.

To gain insight into the mechanisms active in the intestinal CIN and diffuse GS model that allow the metastatic spreading, we analyzed tumors for the presence of epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT). During EMT, the cytoskeletal marker vimentin is up-regulated, and the extracellular matrix component laminin 1 is down-regulated (Supplementary Figure 11A).36 This vimentin/laminin pattern could be observed in the tumors of the intestinal CIN and diffuse GS model, whereas cancer cells in the nonmetastasizing serrated adenomatous GS model showed the opposite pattern (Supplementary Figure 11B). Cancer cells in the metastasizing models, therefore, undergo EMT, explaining at least in part their different metastatic behavior.

Treatment Responses Differ Between Gastric Cancer Models

Tumor organoids were generated from each of the 3 models and selected via removal of medium compounds depending on the altered specific pathways (see “Materials and Methods” section). Tumor organoids from the intestinal CIN model grew as cystic structures with a thin lumen forming large organoids (Figure 6Ai and iv). Diffuse GS tumor organoids showed a noncoherent grape-like growth pattern (Figure 6Aii, vi), whereas the serrated adenomatous GS tumor organoids presented with a compact irregular growth pattern with no lumen (Figure 6Aiii and vi). We observed a significantly slower proliferation rate of the serrated adenomatous GS model compared with the intestinal CIN and diffuse GS models (4.3% vs 12.1% and 11.8%, respectively). The in vitro proliferation rate, therefore, fits to the observed in vivo progression rate.

Figure 6.

Gastric cancer organoid models characterized by different morphology and drug response. (A1–3) Gastric cancer organoid morphology of 3 subtypes: intestinal CIN, diffuse GS, and serrated adenomatous GS organoid model. (A4–6) H&E staining of gastric cancer organoid lines. Scale bar, 100 μm. (B) Proliferation assay of established cancer organoid lines. Statistical analysis of the percentage of EdU+ cells by Student t test (*P < .05, **P < .01). (C) Dose-response curves of organoids treated with classical chemotherapy (5-FU, oxaliplatin, docetaxel). Statistical analysis of dose response curves by repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA). (D) Targeting of the EGFR signaling pathway with trametinib. Dose response curve after 72 hours of trametinib treatment. Statistical analysis by repeated-measures ANOVA (*P < .05). Western Blot of ERK1/2 and phosphorylated ERK1/2 levels of the 3 models after 10 nmol/L trametinib treatment for 72 hours. Amount of apoptotic cells (FITC-Annxein V+/PI+ and FITC-Annexin V+/PI– cells) after 10 nmol/L and 72 hours trametinib treatment. Statistical analysis of the percentage of apoptotic cells by Student t test (*P < .05, **P < .01). M, mol/L.

To investigate how the different gastric cancer subtypes reacted to conventional chemotherapeutics, they were treated with routinely used drugs in gastric cancer treatment (ie, 5-FU, oxaliplatin, and docetaxel) (Figure 6C). No significant difference in drug response was seen for classical chemotherapeutics. However, a trend to docetaxel resistance in both GS models compared with the intestinal CIN model was observed (P = .13 and .17). Neither GS model dropped below 50% viability in the tested concentration range, whereas the intestinal CIN model’s viability decreased down to 20%.

To test drug responses to targeted therapeutics, we chose to target the EGF receptor (EGFR) pathway by trametinib, because this pathway was altered in all 3 mouse models (Figure 6D). The blockage on the level of MEK1/2 with trametinib led to a significantly higher response of the diffuse GS compared to the intestinal CIN model (p = .007). To validate the treatment, we analyzed the level of pathway blockage by determining the downstream extracellular signal–related kinase 2 phosphorylation level. All 3 models showed a substantial down-regulation of ERK1/2 phosphorylation. The blockage of the EGFR pathway led to a significant increase in apoptotic cells in the serrated adenomatous GS model, whereas the intestinal CIN and diffuse GS model did not respond to the treatment with a significant change. Thus, although inhibition of the EGFR pathway was achieved in all 3 models, only the GS models responded to the treatment. Interestingly, the sensitivity of the diffuse GS is not a result of increased cell death, although this is the case for the serrated adenomatous GS model (Figure 6D).

Discussion

To establish gastric cancer mouse models using the Cre/LoxP technique, an inducible stomach-specific CreERT2 mouse line was needed. Several inducible Cre mouse lines with recombination activity in the stomach have been described and used for genetic studies in the stomach, such as Krt19-CreERT2, Mist1-CreERT2, Lgr5-CreERT2, Tff2-CreERT2, or Lrig-CreERT2.37, 38, 39, 40, 41 Nevertheless, the expression of Cre driver genes in all those lines is not restricted to the stomach: KRT19 is widely and highly expressed in several organs, including the intestine, colon, lung or mammary gland; MIST1 (BHLHA15) is additionally highly expressed in salivary and lacrimal glands, prostate and pancreas; LGR5 is also abundant in the intestine, epidermis and prostate; TFF2 is additionally present in the pancreas, and LRIG is also highly expressed in the intestine, colon and epidermis.37, 38, 39, 40, 41 Because of the Cre activity in multiple organs, these mouse lines have only a limited use in cancer research. As an example, Apc deletion using Lgr5-CreERT2 mice results in small adenomas in the antrum.37 Analysis of later stages is not possible because of the heavy tumor load in the intestine in this model. In contrast to this, TFF1 is expressed only in the stomach epithelium but is specifically expressed in mucus-producing pit cells of the corpus and in the antrum.42 Activation of Kras and Stat3 dependent inflammation in Tff1-CreERT2 mice led to gastric adenoma development in the antrum but not in the main body of the stomach. Because of the absence of an inducible Cre line with recombination in the main body of the stomach (ie, the corpus), we performed database mining and literature searches. We identified Car9, Cldn18, and Anxa10 as potential candidates. Only Anxa10 proved, in the end, to be exclusively expressed in the stomach on RNA level in public database, whereas Car9 and Cldn18 were not, with expression also in small/large intestine and lung, respectively. IHC of ANXA10 confirmed expression in the stomach on the protein level. In addition, a low signal within the kidney was observed, which contrasts the RNA data and which, in any case, did not result in Cre activity as measured by LacZ positivity. We conclude that the Anxa10-CreERT2 line is a bona fide stomach-specific Cre mouse.

In contrast to the transgenic Tff1 lines, the Anxa10-CreERT2 line predominantly recombines in the corpus region (but also in the antrum) and is not cell-type restricted. Activation of Cre results in a patchy recombination pattern throughout the whole gland. Due to the patchy recombination, the line might not be an ideal tool when complete recombination of a floxed candidate allele in all cells of the stomach epithelium is required. On the other hand, the patchy recombination allows for a titration of recombination events, based on the amount of tamoxifen applied. This is optimal for cancer models, where a complete tumorous transformation of a whole organ is not desired, as this does not recapitulate the single lesion normally found in sporadic human tumors.

A known issue of tamoxifen administration is its adverse effect on the gastric mucosa, leading to parietal cell depletion and increased proliferation.23, 24, 25, 26 Because there is a wide range of the effect of tamoxifen, we tested the Anxa10-CreERT2 as well as the tumor models. We did observe in our lines a depletion of parietal cells by IHC and, on average, a 50% lower messenger RNA (mRNA) expression level of vascular endothelial growth factor β. The Ki67 staining showed an increase of proliferating cells and a clear shift toward the gland bottom in the cancer models, whereas in the Anxa10-CreERT2 line, only a slight widening of the proliferative zone, a displacement of a few proliferative cells toward the gland bottom, and a slight increase of mRNA levels (1.6-fold) could be observed (Supplementary Figure 2A–C). The stronger boost in proliferation in the cancer models, therefore, is a combination of the tamoxifen effect and the induced oncogenic signaling. Taken together, tamoxifen did induce changes in our models that could induce intestinal metaplasia or spasmolytic polypeptide-expressing metaplasia and might therefore drive initial dysplastic development together with the oncogenes. We used a rather high dose of tamoxifen (5 mg intraperitoneally) for the genetically complex mouse models presented here, but we successfully recombined alleles with doses down to 1 mg using the Anxa10-CreERT2 line (data not shown).

The newly established Anxa10-CreERT2 line was used to generate tumor models of different subtypes of gastric cancer by crossing the line with mice conveying subtype-specific alterations. The TCGA database was used to define frequently altered pathways for each of the defined molecular subtypes. Mutations, genomic alterations, or transcriptional changes were found in genes predominantly belonging to the RTK-RAS, PI3K, WNT, TP53, TGF-β, cell motility, and chromatin remodeling pathways. Frequencies varied between TCGA molecular subtypes, and for each subtype, different combinations of the most frequently altered pathways can be designed. Although principally all possible combinations are potentially interesting, we here focused on the analysis of 3 different models for 2 of the TCGA subtypes: 1 model for the CIN, and 2 are for the GS subtype. To the best of our knowledge, these models represent the first inducible gastric cancer mouse models showing predominantly tumor initiation in the stomach corpus. Furthermore, the different models mimic very closely the histology of known human gastric cancer subtypes. In the intestinal CIN model, formation of tumor cells into glandular and tubular structures was observed, recapitulating well to the described morphologies of human intestinal-type gastric cancer.13 Tumors progressed into invasive cancers and developed liver and lung metastases. Characteristic of the GS subtype is the loss of CDH1 or alterations in other cell mobility enhancing genes. Our GS models, therefore, have a Cdh1 deletion as a common characteristic. Combined with the activation of Kras and loss of Smad4, developing tumors showed a diffuse morphology with the prototypic presence of signet ring cells. Advanced cancers developed peritoneal carcinomatosis as a main metastatic site as well as lung metastases. The divergent metastatic patterns observed in the invasive CIN intestinal model and the invasive diffuse GC model finds their correlation in different patterns of recurrence in patients depending on the Lauren subtype: intestinal-type human gastric cancer most frequently metastasizes to the liver, whereas the diffuse type frequently metastasizes to the lung and peritoneum.43 A completely different morphology was seen in the GS model containing WNT pathway activation. Here, an adenomatous morphology with tooth-like structures was observed. Although no metastases were detected in this model, large noninvasive tumors were formed inside of the stomach lumen, resulting in the occlusion of food passage. The characteristic tooth-like structures are reminiscent of the histology of serrated adenomas of the colon.44 This type of adenoma has also been described in gastric lesions.35 The features of each generated model are summarized in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Characteristic features of gastric cancer models. (A) Genotype and phenotype features of the intestinal CIN model. (B) Genotype and phenotype features of the diffuse and the serrated adenomatous GS model.

Despite recent advances in the understanding of the molecular basis of gastric cancer, treatment of gastric cancer patients is still mainly based on classical chemotherapies, with anti-Her2 (trastuzumab) and anti-angiogenesis treatment (ramucirumab) being the only exceptions. We therefore set out to investigate the therapeutic responses of the different models. To this end, we used organoids derived from developed cancers in the mouse models. We and others have recently shown that gastric cancer organoids are a useful tool between classical 2D cultures and the in vivo situation to model gastric cancer.9, 10, 11, 12 Significant differences were observed in the response of cancer organoids to the classical chemotherapeutic drug docetaxel and to the MEK1/2 inhibitor trametinib. The established mouse and organoid lines might therefore constitute innovative molecular subtype–specific model systems to test individualized treatment regiments.

In summary, the generation of the stomach-specific and inducible Cre recombinase mouse line Anxa10-CreERT2 allowed us to model different known subtypes of gastric cancer. The created models mimicked the histology observed in human counterparts and showed divergent patterns of metastatic spread. Furthermore, the models allow analysis at different stages, helping us to understand the molecular development and progression of gastric cancer. In addition, the mouse lines allow for the first time in vivo monitoring of drug responses in models that closely mimic different subtypes of human gastric cancer before going into clinical trials. The established cancer organoid lines represent a relatively easy-to-use, elegant in vitro tool to further analyze cancer-related signaling pathways and screen (also large-scale) in vitro novel targeted treatments. Taken together, the generated models constitute a prime research tool for future gastric cancer research.

Acknowledgments

We thank Susanne Schindler and Kathleen Schmidt for excellent technical assistance and for taking care of the mouse colony.

Author contributions: Study concept and design: Therese Seidlitz, Bon-Kyoung Koo, Daniel E. Strange. Acquisition of data: Therese Seidlitz, Yi-Ting Chen, Sebastian Schölch, Susan Kochall, Sebastian R. Merker, Heike Uhlemann, Alexander Hennig, Christine Schweitzer, Kristin Pape, Daniela E. Aust, Bon-Kyoung Koo. Analysis and interpretation of data: Therese Seidlitz, Yi-Ting Chen, Sebastian R. Merker, Daniela E. Aust, Bon-Kyoung Koo. Drafting of the manuscript: Therese Seidlitz, Daniel E. Strange. Statistical analysis: Anna Klimova. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Gustavo B. Baretton, Thilo Welsch, Daniela E. Aust, Jürgen Weitz, Bon-Kyoung Koo.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest The authors disclose no conflicts.

Funding This work was supported by the Deutsche Krebshilfe (111350), Wilhelm Sander-Stiftung (2014.104.1), and Hector Stiftung (M65.2) to Daniel E. Strange, as well as the European Union (European Research Council639050) to Daniel E. Strange and Bon-Kyoung Koo.

Author names in bold designate shared co-first authorship.

Note: To access the supplementary material accompanying this article, visit the online version of Gastroenterology at www.gastrojournal.org, and at https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2019.09.026.

Supplementary Materials and Methods

Mouse Genotyping

Mouse tail DNA for initial genotyping of pups and DNA from stomach tumors as well as tumor organoids (to confirm recombination of the floxed alleles) was isolated via phenol/chloroform extraction and isopropanol precipitation according to a standard protocol. Standard polymerase chain reactions (PCRs) were performed with Hot Start Go Taq polymerase (Promega, Madison, WI) by using the following primers:

KrasG12D/+ (Kras G12D_3: CTA GCC ACC ATG GCT TGA GT; Kras G12D_4: ATG TCT TTC CCC AGC ACA GT; Kras G12D_5: TCC GAA TTC AGT GAC TAC AGA TG)

Tp53R172H/+ (LSL_p53_for: AGC TAG CCA TGG CTT GAG TAA GTC TGC A; WT_p53_for: CTG TTC GTT CCA TTC CGT TT; WT_p53_rev: AGC CAC ACT GAC AAT AGG T)

Apcfl/fl (APC_fwd: GAG AAA CCC TGT CTC GAA AAA A; APC_rev: AGT GCT GTT TCT ATG AGT CAA C; APC_int14R4: TTG GCA GAC TGT GTA TAT AAG C)

Cdh1fl/fl (Cdh1_fwd: GGG TCT CAC CGT AGT CCT CA; Cdh1_rev: GAT CTT TGG GAG AGC AGT CG; Cdh1_pl10as.3: TGA CAC ATG CCT TTA CTT TAG T)

Smad4fl/fl (gSmad4R2: GAC CCA AAC GTC ACC TTC AG; gSmad4R1: GGG CAG CGT AGC ATA TAA GA; gSmad4F: AAG AGC CAC AGG TCA AGC AG)

Cre recombination was validated for each floxed allele in every analyzed tumor (Supplementary Figure 3). Only tumors with a recombination in all floxed alleles were further analyzed.

Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction

RNA of normal stomach corpus tissue was isolated using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The isolated RNA was transcribed to complementary DNA via the High Capacity complementary DNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Quantitative PCR was performed with the Go Taq polymerase qRT-PCR Master Mix (Promega) by using the following primers:

Ki67 (mKi67_for: CGA AAG TTG CGA AAC ATG TC; mKi67_rev: TGC TTG TGG GTT TCT TTG G)

Vegfβ (mVegfβ_for: AAA GGA GAG TGC TGT GAA GC; mVegfβ_rev: GTG GGA TGG ATG TCA GC).

Data were next normalized using the ΔΔcycle threshold (CT) method using Gapdh as a housekeeping gene and untreated stomach corpus as a reference tissue.

Immunohistochemistry and Imaging

Mouse tissue was embedded in paraffin after dehydration and sectioned into 4-μm sections. Slides were stained according to a standard protocol for ANXA10 (1:2000; Sigma-Aldrich, #HPA005469), KI67 for proliferating cells (1:200, Abcam, Cambridge, UK; #16667), pepsinogen C (PGC) for chief cells (1:2500; Abcam, #180709), vascular endothelial growth factor beta (VEGFβ) for parietal cells (1:500; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX; sc1876),1 PAS (Abcam, #150680), cytokeratin 20 (1:1000, Abcam, #97511), SMAD4 (1:500, Abcam, #40759), TP53 (1:1000; Leica, Wetzlar, Germany; P53-CM5P-L), β-catenin (1:500, Abcam, #32572), vimentin (1:250, EPR3776, Abcam, #92547) laminin 1 (1:300; Bioss, Woburn, MA; #bs-0821R), CDX2 (1:1000, Abcam, #76541), and TFF2 (1:1000, Bioss, bs1921R). Antigen retrieval for PGC was performed in 0.01 mol/L citrate buffer pH 9.0. For all other stainings, antigen retrieval was performed in 0.01 mol/L citrate buffer pH 6.0. The Signal Stain Detection Boost IHC/HRP rabbit (#8144S, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) was used for KI67, PGC, β-catenin, vimentin, and laminin 1 detection. VEGFβ was detected after incubation with the secondary antibody ZyMAX rabbit anti goat IgG (H+L) HRP-conjugate (1:200; Invitrogen, Waltham, MA; #811620). Stainings were either imaged by an EVOS FL Auto microscope (Life Technologies, Rockville, MD) or scanned by a Digital Pathology Scanner (Philips Amsterdam, The Netherlands).

Immunofluorescence Stainings and Imaging

Mouse stomach tissue was fixed for 1 hour at 4% formaldehyde and then embedded in 4% low-melting agarose. Tissue staining was performed according to standard immunofluorescence protocols with the following primary antibodies: KI67 (1:250, Abcam, #16667), PGC (1:200, Abcam, #180709), VEGFβ (1:200, Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, sc1876), lectin-GSII Alexa Fluor 594 conjugate (1:200, Invitrogen, L21416), and chromogranin A (1:200, Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, sc-13090, H-300). For detection, the fluorescence-labeled secondary antibodies donkey anti-rabbit A594 (1:200; BioLegend, San Diego, CA; #406418), rabbit anti-goat A594 (1:200, Invitrogen, A11080), and goat anti-mouse A594 (1:200, Invitrogen, A11032) were used. Tissue was counterstained using 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (1:2000, Sigma Aldrich, #10236276001) and analyzed with an LSM 880 Airy microscope (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). Immunofluorescence on paraffin slides was similarly performed and stained with the following primary antibodies: PCNA (1:50, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-25280, F-2) and PGC (1:200, Abcam, #180709). For detection, the fluorescence-labeled secondary antibodies goat anti-mouse A488 (1:200, Invitrogen, A11029) and goat anti-rabbit A633 (1.200, Invitrogen, A21071) were used. These slides were analyzed using the fluorescence microscope (Leica).

Western Blot

For protein extraction, murine stomach tissues or tumor-derived organoids were lysed in 100 μL RIPA buffer, and 10–15 μg protein was used for sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Antibody incubation of blots was performed according to standard protocols. The following antibodies were used (all from Cell Signaling Technology, and each diluted 1:1000): ERK1/2 (#9102), phospho-ERK1/2 Thr202/Tyr204 (#9101), RAS G12D (D8H7, #14429), GAPDH (#2118), and anti-mouse IgG HRP linked secondary antibody (#7076S).

Confirmation of Pathway Activation

Activation of the KrasG12D/+ allele was confirmed by Western blot in all models (Supplementary Figure 4A). WNT pathway activation by loss of the Apcfl/fl allele led to a nuclear localization of β-catenin in the serrated adenomatous GS model (Supplementary Figure 4B). Activation of the Tp53R172H/+ mutation within the intestinal CIN model led to an accumulation of TP53 within the nucleus (Supplementary Figure 4C). Loss of SMAD4 was validated by immunohistochemistry in the intestinal CIN as well as the GS diffuse model (Supplementary Figure 4D).

Viability Assay

Cell viability was determined by using the Presto Blue Cell Viability Reagent (Invitrogen). Organoids were plated in 384-well plates in 15 μL Matrigel (Corning, MA) and covered with 50 μL corresponding medium for 24 hours, followed by incubation with chemotherapeutic drugs or small molecule for 24–72 hours. Presto Blue reagent (final 1×) was added, organoids were incubated for 3 hours at 37°C, and fluorescence measured at 560/590 nm using a Varioskan Lux (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Proliferation Assay

Proliferation was assessed by EdU incorporation. Organoids were dissociated using TrypLE (Gibco, Waltham, MA) and stained by using the Click-iT EdU Flow Cytometry Assay (Invitrogen). Organoids were incubated for 2 hours with EdU in 48-well plates prior to analysis. Samples were analyzed with the flow cytometer LSRII (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ).

Apoptosis Assay

Organoids were treated with 10 nmol/L trametinib for 72 hours, isolated from Matrigel by TrypLE, and incubated with FITC-Annexin V (#556419, BD Biosciences) and propidium iodide (Sigma-Aldrich). Samples were analyzed by flow cytometry (LSRII, BD Biosciences).

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Global Burden of Disease Cancer Collaboration The global burden of cancer 2013. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1:505–527. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.0735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arnold M., Soerjomataram I., Ferlay J. Global incidence of oesophageal cancer by histological subtype in 2012. Gut. 2015;64:381–387. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-308124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McColl K.E.L., Going J.J. Aetiology and classification of adenocarcinoma of the gastro-oesophageal junction/cardia. Gut. 2010;59:282–284. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.186825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Kim J., Bowlby R. Integrated genomic characterization of oesophageal carcinoma. Nature. 2017;541(7636):169–175. doi: 10.1038/nature20805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hunt R.H., Camilleri M., Crowe S.E. The stomach in health and disease. Gut. 2015;64:1650–1668. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-307595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ychou M., Boige V., Pignon J.P. Perioperative chemotherapy compared with surgery alone for resectable gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma: an FNCLCC and FFCD multicenter phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1715–1721. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.0597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cunningham D., Allum W.H., Stenning S.P. Perioperative chemotherapy versus surgery alone for resectable gastroesophageal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:11–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al-Batran S.-E., Hofheinz R.D., Pauligk C. Histopathological regression after neoadjuvant docetaxel, oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin versus epirubicin, cisplatin, and fluorouracil or capecitabine in patients with resectable gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (FLOT4-AIO): results from the phase 2 part of a multicentre, open-label, randomised phase 2/3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;17:1697–1708. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30531-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seidlitz T., Merker S.R., Rothe A. Human gastric cancer modelling using organoids. Gut. 2019;68:207–217. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2017-314549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nanki K., Toshimitsu K., Takano A. Divergent routes toward Wnt and R-spondin niche independency during human gastric carcinogenesis. Cell. 2018;174:856–869. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yan H.H.N., Siu H.C., Law S. A comprehensive human gastric cancer organoid biobank captures tumor subtype heterogeneity and enables therapeutic screening. Cell Stem Cell. 2018:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2018.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vlachogiannis G., Hedayat S., Vatsiou A. Patient-derived organoids model treatment response of metastatic gastrointestinal cancers. Science. 2018;359(6378):920–926. doi: 10.1126/science.aao2774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lauren P. The two histological main types of gastric carcinoma: diffuse and so-called intestinal-type carcinoma. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1965;64:31–49. doi: 10.1111/apm.1965.64.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network Comprehensive molecular characterization of gastric adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2014;513(7517):202–209. doi: 10.1038/nature13480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Dyke T., Jacks T. Cancer modeling in the modern era: progress and challenges. Cell. 2002;108:135–144. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00621-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Branda C.S., Dymecki S.M. Talking about a revolution: the impact of site-specific recombinases on genetic analyses in mice. Dev Cell. 2004;6:7–28. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00399-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hayakawa Y., Fox J.G., Gonda T. Mouse models of gastric cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2013;5:92–130. doi: 10.3390/cancers5010092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olive K.P., Tuveson D.A., Ruhe Z.C. Mutant p53 gain of function in two mouse models of Li-Fraumeni syndrome. Cell. 2004;119:847–860. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xiao Y., Cuiling L., Pedro-Luis H. Generation of Smad4/Dpc4 conditional knockout mice. Genesis. 2002;32:80–81. doi: 10.1002/gene.10029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jackson E.L., Willis N., Mercer K. Analysis of lung tumor initiation and progression using conditional expression of oncogenic K-ras. Genes Dev. 2001;15:3243–3248. doi: 10.1101/gad.943001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boussadia O., Kutsch S., Hierholzer A. E-cadherin is a survival factor for the lactating mouse mammary gland. Mech Dev. 2002;115:53–62. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(02)00090-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuraguchi M., Wang X.P., Bronson R.T. Adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) is required for normal development of skin and thymus. PLoS Genet. 2006;2(9):e146. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burclaff J., Osaki L.H., Liu D. Targeted apoptosis of parietal cells is insufficient to induce metaplasia in stomach. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:762–766. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saenz J.B., Burclaff J., Mills J.C. Modeling murine gastric metaplasia through tamoxifen-induced acute parietal cell loss. In: Ivanov A.I., editor. Gastrointestinal physiology and diseases: methods and protocols. Springer; New York: 2016. pp. 329–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huh W.J., Khurana S.S., Geahlen J.H. Tamoxifen induces rapid, reversible atrophy, and metaplasia in mouse stomach. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:21–24. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.09.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huh W.J., Mysorekar I.U., Mills J.C. Inducible activation of Cre recombinase in adult mice causes gastric epithelial atrophy, metaplasia, and regenerative changes in the absence of “floxed” alleles. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2010;299:G368–G380. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00021.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stange D.E., Koo B.-K., Huch M. Differentiated Troy+ chief cells act as reserve stem cells to generate all lineages of the stomach epithelium. Cell. 2013;155:357–368. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhao Z., Hou N., Sun Y. Atp4b promoter directs the expression of Cre recombinase in gastric parietal cells of transgenic mice. J Genet Genomics. 2010;37:647–652. doi: 10.1016/S1673-8527(09)60083-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kinoshita H., Hayakawa Y., Konishi M. Three types of metaplasia models through Kras activation, Pten deletion, or Cdh1 deletion in the gastric epithelium. J Pathol. 2018;247:35–47. doi: 10.1002/path.5163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao G.-F., Zhao S., Liu J.-J. Cytokeratin 19 promoter directs the expression of Cre recombinase in various epithelia of transgenic mice. Oncotarget. 2017;8:18303–18311. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhao Z., Sun Y., Hou N. Capn8 promoter directs the expression of Cre recombinase in gastric pit cells of transgenic mice. Genesis. 2009;47:674–679. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.El Marjou F., Janssen K.-P., Hung-Junn Chang B. Tissue-specific and inducible Cre-mediated recombination in the gut epithelium. Genesis. 2004;39:186–193. doi: 10.1002/gene.20042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cerami E., Gao J., Dogrusoz U. The cBio Cancer Genomics Portal: an open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer Discov. 2014;2:401–404. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gao J., Aksoy B.A., Dogrusoz U. Integrative analysis of complex cancer genomics and clinical profiles using cBioPortal. Sci Signal. 2014;6:PL1. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rubio C.A. Serrated neoplasia of the stomach: a new entity. J Clin Pathol. 2001;54:849–853. doi: 10.1136/jcp.54.11.849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zeisberg M., Neilson E.G. Biomarkers for epithelial-mesenchymal transitions. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1429–1437. doi: 10.1172/JCI36183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Quante M., Marrache F., Goldenring J.R. TFF2 mRNA transcript expression marks a gland progenitor cell of the gastric oxyntic mucosa. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:2018–2027. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Means A.L., Xu Y., Zhao A. A CK19CreERT knockin mouse line allows for conditional DNA recombination in epithelial cells in multiple endodermal organs. Genesis. 2008;46:318–323. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nam K.T., Lee H.-J., Sousa J.F. Mature chief cells are cryptic progenitors for metaplasia in the stomach. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:2028–2037. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barker N., Huch M., Kujala P. Lgr5+ve stem cells drive self-renewal in the stomach and build long-lived gastric units in vitro. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;6:25–36. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schweiger P.J., Clement D.L., Page M.E. Lrig1 marks a population of gastric epithelial cells capable of long-term tissue maintenance and growth in vitro. Sci Rep. 2018;8:15255. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-33578-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thiem S., Eissmann M.F., Elzer J. Stomach-specific activation of oncogenic KRAS and STAT3-dependent inflammation cooperatively promote gastric tumorigenesis in a preclinical model. Cancer Res. 2016;76:2277–2287. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-3089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee J.H., Chang K.K., Yoon C. Lauren histologic type is the most important factor associated with pattern of recurrence following resection of gastric adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 2018;267:105–113. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Longacre T.A., Fenoglio-Preiser C.M. Mixed hyperplastic adenomatous polyps/serrated adenomas. A distinct formm of colorectal neoplasia. Am J Surg Pathol. 1990;14:524–537. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199006000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Reference

- 1.Mills J.C., Syder A.J., Hong C.V. A molecular profile of the mouse gastric parietal cell with and without exposure to Helicobacter pylori. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:13687–13692. doi: 10.1073/pnas.231332398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.