Abstract

Epigenetic alternations concern heritable yet reversible changes in histone or DNA modifications that regulate gene activity beyond the underlying sequence. Epigenetic dysregulation is often linked to human disease, notably cancer. With the development of various drugs targeting epigenetic regulators, epigenetic-targeted therapy has been applied in the treatment of hematological malignancies and has exhibited viable therapeutic potential for solid tumors in preclinical and clinical trials. In this review, we summarize the aberrant functions of enzymes in DNA methylation, histone acetylation and histone methylation during tumor progression and highlight the development of inhibitors of or drugs targeted at epigenetic enzymes.

Subject terms: Drug development, Cancer epidemiology

Introduction

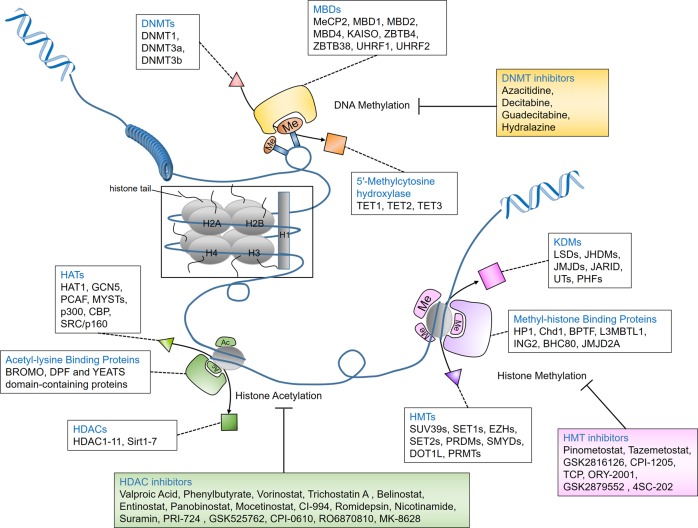

After the discovery of DNA and the double helix structure, classic genetics has long assumed that the sequences of DNA determine the phenotypes of cells. DNA is packaged as chromatin in cells, with nucleosomes being the fundamental repeating unit. Four core histones (H2A, H2B, H3, and H4) form an octamer and are then surrounded by a 147-base-pair (bp) segment of DNA. Nucleosomes are separated by 10–60 bp DNA. Researchers have gradually found organisms that share the same genetic information but have different phenotypes, such as somatic cells from the same individual that share a genome but function completely differently. The term epigenetics was first proposed and established in 1942 when Conrad Waddington tried to interpret the connection between genotype and phenotype.1 Later, Arthur Riggs and his group interpreted epigenetics as inherited differences in mitosis and meiosis, which could explain the changes in phenotypes. They were both trying to find the link between genotype and phenotype. Epigenetics is usually referred to as a genomic mechanism that reversibly influences gene expression without altering DNA sequences. Holliday assumed that epigenetics was also mitotically and/or meiotically heritable without DNA sequence change. Aberrant DNA methylation could be repaired via meiosis, but some patterns are still transmitted to offspring.2 This phenomenon covers a wide range of cellular activities, such as cell growth, differentiation, and disease development, and is heritable.3 Generally, epigenetic events involve DNA methylation, histone modification, the readout of these modifications, chromatin remodeling and the effects of noncoding RNA. The elements involved in different modification patterns can be divided into three roles, “writer,” “reader,” and “eraser”. The “writers” and “erasers” refer to enzymes that transfer or remove chemical groups to or from DNA or histones, respectively. “Readers” are proteins that can recognize the modified DNA or histones (Fig. 1). To coordinate multiple biological processes, the epigenome cooperates with other regulatory factors, such as transcription factors and noncoding RNAs, to regulate the expression or repression of the genome. Epigenetics can also be influenced by cellular signaling pathways and extracellular stimuli. These effects are temporary and yet long-standing. Given the importance of epigenetics in influencing cell functions, a better understanding of both normal and abnormal epigenetic processes can help to understand the development and potential treatment of different types of diseases, including cancer.

Fig. 1. Epigenetic regulation of DNA methylation, histone acetylation, and histone methylation.

Gene silencing in mammalian cells is usually caused by methylation of DNA CpG islands together with hypoacetylated and hypermethylated histones. The “writers” (DNMTs, HATs, and HMTs) and “erasers” (DNA-demethylating enzymes, HDACs, and KDMs) are enzymes responsible for transferring or removing chemical groups to or from DNA or histones; MBDs and other binding proteins are “readers” that recognize methyl-CpGs and modified histones. DNMTs, DNA methyltransferases; MBDs, methyl-CpG binding domain proteins; HATs, histone acetylases; HDACs, histone deacetylases; HMTs, histone methyltransferases; KDMs, histone-demethylating enzymes.

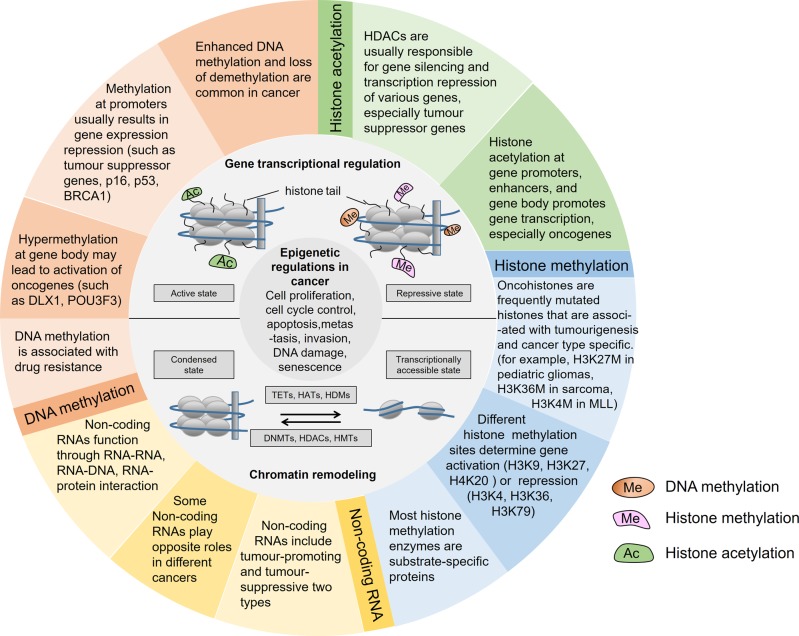

The etiology of cancer is quite complicated and involves both environmental and hereditary influences. In cancer cells, the alteration of genomic information is usually detectable. Like genome instability and mutation, epigenome dysregulation is also pervasive in cancer (Fig. 2). Some of the alterations determine cell function and are involved in oncogenic transformation.4 However, by reversing these mutations by drugs or gene therapy, the phenotype of cancer can revert to normal. Holliday proposed a theory that epigenetic changes are responsible for tumorigenesis. The alteration of cellular methylation status by a specific methyltransferase might explain the differences in the probability of malignant transformation.5 In clinical settings, we noticed that although cancer patients share the same staging and grade, they present totally different outcomes. In tumor tissues, different tumor cells show various patterns of histone modification, genome-wide or in individual genes, indicating that epigenetic heterogeneity exists at a cellular level.6 Likewise, using molecular biomarkers is thought to be a potential method to divide patients into different groups. It is important to note that tumorigenesis is the consequence of the combined action of multiple epigenetic events. For example, the repression of tumor suppressor genes is usually caused by methylation of DNA CpG islands together with hypoacetylated and hypermethylated histones.7 During gene silencing, several hallmarks of epigenetic events have been identified, including histone H3 and H4 hypoacetylation, histone H3K9 methylation, and cytosine methylation.8,9

Fig. 2. Epigenetic regulations in cancer.

Alterations in epigenetic modifications in cancer regulate various cellular responses, including cell proliferation, apoptosis, invasion, and senescence. Through DNA methylation, histone modification, chromatin remodeling, and noncoding RNA regulation, epigenetics play an important role in tumorigenesis. These main aspects of epigenetics present reversible effects on gene silencing and activation via epigenetic enzymes and related proteins. DNMTs, DNA methyltransferases; TETs, ten-eleven translocation enzymes; HATs, histone acetylases; HDACs, histone deacetylases; HMTs, histone methyltransferases; HDMs, histone-demethylating enzymes. MLL, biphenotypic (mixed lineage) leukemia.

Therefore, epigenetics enables us to investigate the potential mechanism underlying cancer phenotypes and provides potential therapy options. In this review, we focused and briefly expanded on three aspects of epigenetics in cancer: DNA methylation, histone acetylation and histone methylation. Finally, we summarized the current developments in epigenetic therapy for cancers.

DNA methylation

The DNA methylation pattern in mammals follows certain rules. Germ cells usually go through a stepwise demethylation to ensure global repression and suitable gene regulation during embryonic development. After implantation, almost all CpGs experience de novo methylation except for those that are protected.10 Normal dynamic changes in DNA methylation and demethylation based on altered expression of enzymes have been known to be associated with aging.11,12 However, inappropriate methylation of DNA can result in multiple diseases, including inflammatory diseases, precancerous lesions, and cancer.13–15 Of note, de novo methylation of DNA in cancer serves to prevent reactivation of repressed genes rather than inducing gene repression.16 Because researchers have found that over 90% of genes undergoing de novo methylation in cancer are already in a repressed status in normal cells.17 Nevertheless, aberrant DNA methylation is thought to serve as a hallmark in cancer development by inactivating gene transcription or repressing gene transcription and affecting chromatin stability.18

The precise mechanism by which DNA methylation affects chromatin structure unclear, but it is known that methyl-DNA is closely associated with a closed chromatin structure, which is relatively inactive.19 Hypermethylation of promoters and hypomethylation of global DNA are quite common in cancer. It is widely accepted that gene promoters, especially key tumor suppressor genes, are unmethylated in normal tissues and highly methylated in cancer tissues.20 P16, a tumor suppressor encoded by CDKN2A, has been found to gain de novo methylation in ~20% of different primary neoplasms.21 Mutations in important and well-studied tumor-suppressive genes, such as P53 and BRCA1, are frequently identified in multiple cancers.22–24 Studies have found that the level of methylation is positively associated with tumor size. In support of this, a whole-genome methylation array analysis in breast cancer patients found significantly increased CpG methylation in FES, P2RX7, HSD17B12, and GSTM2 coincident with increasing tumor stage and size.25 After analysis of long-range epigenetic silencing at chromosome 2q14.2, methylation of EN1 and SCTR, the first well-studied example of coordinated epigenetic modification, was significantly increased in colorectal and prostate cancers.26,27 EN1 methylation has also been observed to be elevated by up to 60% in human salivary gland adenoid cystic carcinoma.28 Of note, only ~1% of normal samples exhibited EN1 CpG island hypermethylation.26 Therefore, the significant difference between cancer cells and normal cells makes EN1 a potential cancer marker in diagnosis. In human pancreatic cancer, the APC gene, encoding a regulator of cell junctions, is hypermethylated by DNMT overexpression.29 During an analysis of colorectal disease methylation patterns, researchers found several genes that showed significant changes between precancerous diseases and cancers, including RUNX3, NEUROG1, CACNA1G, SFRP2, IGF2 DMR0, hMLH1, and CDKN2A.30 In the human colon cancer cell line HCT116, hMLH1 and CDKN2A always bear genetic mutation and hypermethylation of one allele, and this leads to inactivation of key tumor suppressors.31 It is known that p16, p15, and pax6 are usually aberrantly methylated in bladder cancer and show enhanced methylation in cell culture.32. Unlike gene promoter methylation, gene body methylation usually results in increased transcriptional activity.33 This process often occurs in CpG-poor areas and causes a base transition from C to T.34 The hypermethylation of specific CpG islands in cancer tissues is informative of mutations when the gene in normal tissues is unmethylated. One representative marker is glutathione S-transferase-π (GSTP1), which is still the most common alteration in human prostate cancer.35 Recently, DNA methylation in cancer has generally been associated with drug resistance and predicting response to treatment.36 For example, MGMT (O-6-methylguanine DNA methyltransferase) hypermethylation is still the best independent predictor of response to BCNU (carmustine) and temozolomide in gliomas because hypermethylation of MGMT makes tumor cells more sensitive to treatments and is associated with regression of tumor and prolonged overall survival.37,38 Similarly, MGMT is also a useful predictor of response to cyclophosphamide in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma39 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Key regulatory factors of DNA methylation in cancer.

| Enzyme | Roles in cancer | Cancer type | Associated biological process (involved mechanism and molecules) |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA methyltransferases | |||

| DNMT1: DNMT1 is responsible for maintenance of DNA methylation and is expressed at high concentrations in dividing cells to guard existing methylated sites. | |||

| Promoter | AML, CML, cervical cancer, colorectal cancer, glioma, lung cancer, pancreatic cancer, gastric cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, breast cancer, esophageal cancer, bladder cancer, prostate cancer, thyroid cancer, ovarian cancer92–100 | Promotes EMT phenotype, cell apoptosis, cell proliferation, migration, cancer stemness, and cisplatin sensitivity (β-catenin, E-cadherin, PTEN, p18, p27, P21, P16, miR-124, miR-148a, miR-152, miR-185, miR-506), DNMT1 is also upregulated by Helicobacter pylori CagA | |

| Suppressor | Prostate cancer, cervical cancer101,102 | Cell migration, EMT and stem cell potential | |

| DNMT3a: DNMT3a methylates unmethylated DNA de novo and is required for maternal imprinting at different methylated regions. | |||

| Promoter | Cervical cancer, CML, breast cancer, gastric cancer, prostate cancer, ovarian cancer, bone cancer, testicular cancer52,103–107 | Promotes cell proliferation and invasion. (VEGFA, Wnt/β-catenin signaling, miR-182, miR-708-5p) | |

| Suppressor | Lymphoma, AML, breast cancer, colorectal cancer, lung cancer108–110 | Low level of DNMT3a is associated with the poor survival of cancer patients and promotes tumor progression but not initiation | |

| DNMT3b: DNMT3b is also responsible for de novo methylation and is required for methylation of centromeric minor satellite repeats and CGIs in inactive X chromosomes. | |||

| Promoter | CML, AML, glioma, lung cancer, breast cancer, gastric cancer, colorectal cancer, prostate cancer, pancreatic cancer, bladder cancer, cervical cancer52,94,111–113 | Promotes cell proliferation, and invasion and the chemotherapy effects of cisplatin; is associated with poor prognosis (E-cadherin, PTEN, P21, P16, miR-29b, miR-124, miR-506) | |

| Suppressor | AML, bladder cancer109,114 | Downregulation of DNMT3a is associated with poor prognosis | |

| Methyl-CpG binding proteins | |||

| MeCP2 | Promoter | Prostate cancer, colorectal cancer, breast cancer, gastric cancer115,116 | Promotes cell proliferation, invasion, metastasis, apoptosis, cell cycle arrest in the G0/G1 phase, chemotherapy effects, regulation of estrogen receptor status, involves the MEK1/2-ERK1/2 signaling pathway (miR-638, miR-212) |

| Suppressor | Pancreatic cancer117 | Decreased expression of MeCP2 contributes to cancer development | |

| MBD1 | Promoter | Pancreatic cancer, prostate cancer118,119 | Promotes cell EMT, proliferation, invasion, and metastasis and the chemoradioresistance of cancer cells and induces an antioxidant response (E-cadherin) |

| MBD2 | Promoter | Lung cancer, colon cancer, breast cancer, prostate cancer94,120–122 | Promotes cell invasion and metastasis (p14) |

| MBD4 | Promoter | Colon cancer, breast cancer123,124 | Causes dominant negative impairment of DNA repair |

| KAISO (ZBTB33) | Promoter | Colon cancer, cervical cancer, prostate cancer, ovarian cancer, lung cancer, breast cancer, and chronic myeloid leukemia125–128 | Silencing of tumor suppressor genes, EMT, apoptosis, migration and invasion (Wnt/β-catenin, TGFβ, EGFR, Notch, miR-4262, miR-31) |

| ZBTB4 | Suppressor | Breast cancer, Ewing sarcoma, prostate cancer, bladder cancer77,129–131 | Promotes cell growth and apoptosis and controls the cellular response to p53 activation, promoting long-term cell survival (miR-17-92/106b-25 |

| ZBTB38 | Promoter | Bladder cancer132 | Promotes cell migration and invasion (Wnt/β‑catenin pathway) |

| UHRF1 | Promoter | Hepatocellular carcinoma, bladder cancer, renal cell carcinoma, lung cancer, retinoblastoma, intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, colon cancer, pancreatic cancer, gastric cancer, prostate cancer, melanoma, hepatoblastoma, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, cervical cancer, breast cancer, thyroid cancer133–138 | Promotes cell proliferation, EMT, and viability, increases hypoxia inducible factor (HIF)1α, CSCs, taxane resistance correlates with poor pathological characteristics, human papillomavirus (HPV) contributes to overexpression of UHRF1 (miR-101, miR-124, PI3K/Akt signaling pathway, MEK/ERK pathway) |

| UHRF2 | Promoter | Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, colon cancer139,140 | Promotes cell migration and invasion, and is associated with lower disease-free survival |

| suppressor | Colon cancer, lung cancer, esophageal carcinoma141,142 | Low level of UHRF2 is associated with shorter overall survival, vascular invasion and poor prognosis | |

| DNA demethylases | |||

| TET1: TET1 is highly expressed in mouse embryonic stem cells, the inner cell mass of blastocysts, and developing PGCs. | |||

| Promoter | MLL-rearranged leukemia, AML, breast cancer, ovarian cancer, lung cancer, renal cancer143–147 | TET1-MLL fusion, cell migration, anchorage-independent growth, cancer stemness, and tumorigenicity, prevention of senescence via loss of p53, associated with a worse overall survival and sensitivity to drugs (PI3K-mTOR pathway) | |

| Suppressor | Hematopoietic malignancy, hepatocellular carcinoma, prostate cancer, colon cancer, gastric cancer, breast cancer, nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells, ovarian cancer90,148,149 | Promotes EMT and increases cancer cell growth, migration, and invasion (miR-21-5p, Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, AKT and FAK pathways) | |

| TET2/TET3: TET2 and TET3 are present in multiple mouse adult tissues, whereas only TET3 is present in mouse oocytes and one-cell zygotes | |||

| TET2 | Suppressor | MDS, AML, CML, prostate cancer, gastric cancer, breast cancer, colorectal cancer, ovarian cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, leukemia87,150–153 | Promotes cell proliferation, colony formation, metastasis, is associated with reduced patient survival, pathologic stage, tumor grading, lymph node metastasis, and vascular thrombosis (caspase-4, ET2/E-cadherin/β-catenin regulatory loop) |

| TET3 | Promoter | Renal cell carcinoma154 | Acts as an independent predictor of poor outcome |

| Suppressor | Head and neck cancer, ovarian cancer, breast cancer155,156 | Is associated with EMT, overall survival, disease-free survival (miR-30d) | |

AML acute myeloid leukemia, CML chronic myeloid leukemia, EMT epithelial-mesenchymal transition, VEGFR vascular endothelial growth factor receptor

DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs)

DNA methylation is a covalent modification of DNA and is one of the best-studied epigenetic markers. It plays an important role in normal cell physiology in a programmed manner. The best-known type of DNA methylation is methylation of cytosine (C) at the 5th position of its carbon ring (5-mC), especially at a C followed by a guanine (G), so-called CpG sites. Non-CpG methylation, such as methylation of CpA (adenine) and CpT (thymine), is not common and usually has restricted expression in mammals.40 CpG islands traverse ~60% of human promoters, and methylation at these sites results in obvious transcriptional regression.41 Meanwhile, among the ~28 million CpGs in the human genome in somatic cells, 60–80% are methylated in a symmetric manner and are frequently found in promoter regions.42,43 The process of DNA methylation is regulated by the DNA methyltransferase (DNMT) family via the transfer of a methyl group from S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAM) to cytosine.44 There are five members of the DNMT family: DNMT1, DNMT2, DNMT3a, DNMT3b, and DNMT3L. DNMT1 is responsible for the maintenance of methyl-DNA, recognizes hemimethylated DNA strands and regenerates the fully methylated DNA state of DNA during cell division.45 In a recent study, DNMT1 with Stella, a factor essential for female fertility, was responsible for the establishment of the oocyte methylome during early embryo development.46 DNMT3a and DNMT3b are regarded as de novo methylation enzymes that target unmethylated CpG dinucleotides and establish new DNA methylation patterns, but they have nonoverlapping functions during different developmental stages.47,48 DNMT2 and DNMT3L are not regarded as catalytically active DNA methyltransferases. DNMT2 functions as an RNA methyltransferase, while DNMT3L contains a truncated inactive catalytic domain and acts as an accessory partner to stimulate the de novo methylation activity of DNMT3A. The DNA methyltransferase-like protein DNMT3L can modulate DNMT3a activity as a stimulatory factor.49

During aberrant DNA methylation, DNMTs play an important role. Compared with DNMT1 and DNMT3a, DNMT3b was significantly overexpressed in tumor tissues.50 Overexpression of DNMT1, DNMT3a, and DNMT3b has been observed in multiple cancers, including AML, CML, glioma, and breast, gastric, colorectal, hepatocellular, pancreatic, prostate, and lung cancers. In cervical cancer patients, DNMT1 was expressed in more than 70% of cancer cells, whereas only 16% of normal cells expressed DNMT1. The higher level of DNMT1 expression was also associated with worse prognosis.51 The expression of DNMT1, DNMT3a, and DNMT3b has been observed to be elevated in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and various solid cancers. These three methyltransferases do not show significant changes in the chronic phase of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), but they are significantly increased during progression to the acute phase in CML.52,53 Notably, downregulation of DNMTs can also lead to tumorigenesis (Table 1).

Methyl-CpG recognition proteins

How DNA methylation leads to gene repression has been considered in many studies. Several hypotheses have been proposed. Three methyl-CpG binding domain protein (MeCP) families can read the established methylated DNA sequences and in turn recruit histone deacetylases, a group of enzymes responsible for repressive epigenetic modifications, to inhibit gene expression and maintain genome integrity.10,54 The first group is methyl-CpG binding domain (MBD) proteins, including MeCP2, MBD1, MBD2, and MBD4. MeCP1 is a complex containing MBD2, the histone deacetylase (HDAC) proteins HDAC1 and HDAC2, and the RbAp46 and RbAp48 proteins (also known as RBBP7 and RBBP4).55 MBD3 is unlike the other four family members and is not capable of binding to methylated DNA but instead binds to hydroxymethylated DNA.56 The zinc-finger and BTB domain-containing protein family is the second group and comprises three structurally different proteins, KAISO (ZBTB33), ZBTB4 and ZBTB38, which bind to methylated DNA via zinc-finger motifs. The third family includes two ubiquitin-like proteins with PHD and RING finger domains, UHRF1 and UHRF2, which recognize 5-mC via RING finger-associated (SRA) domains. On the other hand, methylation of DNA can also be a barrier for certain transcription factors to bind to promoter sites such as AP-2, c-Myc, CREB/ATF, E2F, and NF-kB.13

As for methyl-group binding proteins, many studies have investigated their roles in various cancers, but the mechanism underlying these alterations remains unclear. MBD proteins cooperate with other proteins to regulate gene transcription.57,58 However, the role of MBD1 and MBD2 has not been identified in human lung or colon cancer, with only limited mutations being detected.59 Furthermore, loss of MBD1 did not show any carcinogenic effect in MBD−/− mice.60 Compared with MBD1, MBD2 shows more effect on tumorigenesis. Deficiency of MBD2 strongly suppresses intestinal tumorigenesis in APCMin-background mice.61 A possible reason is that many important signaling pathways are downregulated in colorectal cancer, and loss of MBD2 leads to reexpression of these genes.62 Meanwhile, inhibition of MBD2 shows promising effects on suppression of the tumorigenesis of human lung cancer and colon cancer.63 Although MBD3 does not directly bind to methylated DNA, it regulates the methylation process via interactions with other proteins, such as MBD2 and HDAC. For example, application of an HDAC inhibitor in lung cancer cells upregulated p21 (also known as CDKN1A) and downregulated ErbB2, leading to inhibition of cancer cell growth. Silencing of MBD3 blocked the effects of an HDAC inhibitor.64 MBD3 and MBD2 form a complex, nucleosome remodeling and deacetylase (NuRD), which interacts with histone-demethylating enzymes to regulate gene expression in cancer.65 Mutation of MBD4 has been found in colorectal cancer, endometrial carcinoma and pancreatic cancer.66 Furthermore, this mutation unexpectedly affects the stability of the whole genome, not only CpG sites.67 Knockout of MBD4 indeed increased tumorigenesis in APCMin-background mice, which makes MBD4 a tumor suppressor.68 MBD4 is important in DNA damage repair, given the interaction between MBD4 and MMR.69 In contrast, the expression of MeCP2 and the UHRF family tends to promote tumor growth.70–74 In the KAISO family, KAISO directly binds to p120ctn, a protein with an alternative location in some cancer cells, and they together regulate cell adhesion and motility.75,76 However, deficiency of ZBTB4 contributes to tumorigenesis77 (Table 1).

DNA-demethylating enzymes

DNA methylation is a stable and highly conserved epigenetic modification of DNA in many organisms.78 However, loss of 5-mC and DNA demethylation have been identified in different biologic processes. For example, DNA demethylation is important for primordial germ cells (PGCs) to gain pluripotent ability.79,80 DNA demethylation is actively regulated by the TET protein family (ten-eleven translocation enzymes, TET1-3) via the removal of a methyl group from 5-mC. These three proteins differ from each other in terms of expression depending on the developmental stage and cell type.18 TETs oxidize 5-mC in an iterative manner and catalyze the conversion of 5-mC to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5-hmC), which is a key intermediate in the demethylation process.81 5-hmC, as a relatively stable intermediate substrate, is less prone to further oxidation by TET proteins than 5-mC.82 However, overexpression of only TET1 and TET2 can cause a global decrease of 5-mC.18 Stepwise oxidation of 5-hmC by TET proteins can yield two products: 5-formylcytosine (5-fC) and 5-carboxylcytosine (5-caC).83 These two molecules can be excised by thymine-DNA glycosylase (TDG) and eventually be repaired to unmodified C.84 DNA demethylation or restoration of the unmodified cytosine can also occur passively through replication-dependent dilution of 5-mC.

Disruption of normal DNA demethylation is thought to be associated with oncogenesis. TET proteins were initially associated with leukemia. Researchers have found that in a small number of AML patients, TET1 is fused to MLL via the chromosome translocation t(10;11)(q22;q23).85 Further studies found that TET2 was more widely expressed in different tissues than TET1 and TET3. Analyses revealed that mutation or deficiency of TET2 occurred in ~15% of patients with myeloid cancers, including myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), myeloproliferative disorders, and AML.86 In patients with CML, mutation of TET2 has been detected in ~50% of patients.87 Although TET2 mutations have been found in several myeloid malignancies, their prognostic effect remains controversial. Based on the phenomenon that mutation of TET2 was elevated in patients whose disease transformed from chronic myeloid malignancy to AML, researchers considered that TET2 loss was important for cells to regain the ability to self-renew.88 The role of TET proteins has also been investigated in several solid tumors. Compared with surrounding normal tissues, 5-hmC is significantly reduced in human breast, liver, lung, pancreatic, and prostate cancers with reduced expression of TET family proteins.89 Deficiency of TET1 in prostate and breast cancer is associated with tumor cell invasion and breast xenograft tumor formation via the inhibition of the methylation of metalloproteinase (TIMP) family proteins 2 and 3.90 Loss of 5-hmC is an epigenetic hallmark of melanoma, and thus, introducing TET2 into melanoma cells results in suppression of tumor growth and increased survival in an animal model91 (Table 1).

Histone modification

Histone modification can occur to the flexible tails as well as the core domain of histones, including those sites that are buried by DNA. In particular, the flexible histone tails are enriched with basic Lys/Arg and hydroxyl group-containing Ser/Thr/Tyr residues, thereby being hotspots for hallmark histone modifications. The tails extend from the surface of the nucleosome and are readily modulated by covalent posttranslational modification (PTM). PTMs modify histones by adding or removing chemical groups and regulate many biological processes via the activation or inactivation of genes. These processes mainly include acetylation and methylation of lysines (K) and arginines (R), phosphorylation of serines (S) and threonines (T), ubiquitylation, and sumoylation of lysines. In addition to those mentioned and discussed above, histone modifications also include citrullination, ADP-ribosylation, deamination, formylation, O-GlcNAcylation, propionylation, butyrylation, crotonylation, and proline isomerization at over 60 amino acid residues.157,158 In addition to conventional PTMs, novel PTM sites are also found outside of the N-terminal tails.

Histone modifications at certain sites, such as promoters and enhancers, are thought to be largely invariant, whereas a small number of these sites remain dynamic. H3K4me1 and H3K27ac, two dynamic modifications, were identified to activate enhancers and regulate gene expression.159 H3K9ac and H3K9me3 are two common modifications at promoters.160,161 Appropriate histone modifications are important in gene expression and human biology; otherwise, alterations in PTMs may be associated with tumorigenesis. Analysis of cancer cells reveals that they exhibit aberrant histone modifications at individual genes or globally at the single-nuclei level.6,162 Understanding histone modification patterns in cancer cells can help us to predict and treat cancers. Thus far, most studies have focused on aberrant modifications within an individual site, such as H4K20me3 or H4K16ac, rather than enzymatic activity-associated abnormalities. Generally, alterations in histone modifications occur at an early stage and accumulate during tumorigenesis.163

Histone acetylation (lysine)

Histone acetylation occurs at multiple lysine residues at the N-terminus via the catalysis of histone acetyltransferases (HATs), also named lysine acetyltransferases (KATs). Histone acetylation regulates the compaction state of chromatin via multiple mechanisms, such as neutralizing the basic charge at unmodified lysine residues, and is associated with active transcription, especially at gene promoters and enhancers and the gene body; it also facilitates the recruitment of coregulators and RNA polymerase complexes to the locus.157,164 To date, HATs and histone deacetylases (HDACs) are the two of the best characterized groups of enzymes involved in histone PTMs. HATs transfer the acetyl groups from acetyl-CoA cofactors to lysine residues at histones, whereas the role of HDACs is the opposite, which makes histone acetylation a highly reversible process.

Histone acetyltransferases

HATs are predominantly located in the nucleus, but multiple lines of evidence have shown lysine acetylation in the cytoplasm, and their acetylation is associated with key cellular events.165 In addition, lysine acetylation found outside histones reminds us of the role of HATs in nonhistone PTMs.166 The first HAT was identified in yeast, and was named HAT1,167 and was then isolated from tetrahymena as HAT A by Allis and coworkers.168 In humans, HATs can be roughly divided into three groups: general control nondepressible 5 (GCN5)-related N-acetyl transferase (GNAT) (based on the protein Gcn5 found in yeast; including GCN5 and PCAF), MYST (based on the protein MOZ; including MOZ, MOF, TIP60, and HBO1), and p300/cAMP-responsive element-binding protein (CBP).169 Other HATs, including nuclear receptors and transcription factors, such as SRC1, MGEA5, ATF-2, and CLOCK, also harbor the ability to acetylate histones. Notably, a number of acetyltransferases also perform protein acetylation outside histones, such as TFIIB, MCM3AP, ESCO, and ARD1.170 Knockout of CBP/p300 is lethal for early embryonic mouse models.171,172 The acetyl group transfer strategies for each HAT subfamily are different. For the GCN5 and PCAF family, the protein crystal structure shows a conserved glutamate in the active site. Blockade of this amino leads to a significantly decreased acetylation function.173,174 Similarly, there is also a conserved glutamate plus a cysteine residue located at active sites of MYST family proteins.175 Unlike the other two families, the p300/CBP HAT subfamily has two other potential conserved residues, a tyrosine and a tryptophan.176 Generally, their catalytic mechanisms of acetyl group transfer can be divided into two groups. The GNAT family depends on a sequential ordered mechanism, whereas the members of the MYST family use a so-called ping-pong (i.e., double displacement) catalytic mechanism, which means that the acetyl groups are first transferred to a cysteine residue and then transferred to a lysine residue.177 In addition to differences in the acetyl transfer mechanism, HAT subfamilies, even different proteins in the same family, also have remarkable diversity in targeting sites.

Appropriate acetylation within cells is important since upregulation or downregulation of HATs is associated with tumorigenesis or poor prognosis.162,178 Compared with solid tumors, the association between histone modifications and cancer has been widely investigated in hematological malignancies. Germline mutation of CBP results in Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome along with an increased predisposition to childhood malignancies. Meanwhile, loss of another family member, p300, has also been associated with hematological malignancies.179,180 Therefore, both CBP and p300 seem to function as tumor suppressors. During cancer development, the expression of HAT genes can be disrupted by chromosomal translocations, although these are rare events. Generation of the fused protein CBP-MOZ is the result of the t(8,16)(p11,p13) translocation in AML.181 Translocation of t(10;16)(q22;p13) leads to the CBP-MORF chimera.182 Similarly, p300-MOZ, MLL-CBP, and MLL-p300 (MLL, mixed lineage leukemia) have also been identified in hematological malignancies.183–185 Generally, chromosomal rearrangements involving CBP are more common than those involving p300. Researchers have also investigated solid tumors, which are less mutated. The expression of translocated P300 in laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma (LSCC) tissue is much higher than that in adjacent normal tissue and is associated with advanced stage and poor prognosis.178 Missense point mutations in p300 are found in colorectal adenocarcinoma, gastric adenocarcinoma and breast cancer with quite low incidences.186,187 Rare inactivating mutations in CBP and PCAF have only been identified in cancer cell lines but not primary tumors.188 Based on these findings, we hypothesize that the differences between cell lines and primary tumors cannot be ignored. Amplified in breast cancer 1 (AIB1), also frequently called NCOA3 (nuclear receptor coactivator 3) or SRC3 (steroid receptor coactivator 3), is overexpressed in ~60% of human breast cancers, and increased levels of AIB1 are associated with tamoxifen resistance and decreased overall survival.189 Steroid receptor coactivator 1 (SRC1) is also associated with the chromosomal translocation t(2;2)(q35;p23), which results in PAX3–NCOA1 gene fusion in rhabdomyosarcoma without a consistent genetic abnormality during embryonic development190 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Important enzymes or proteins that regulate histone acetylation in cancer.

| Enzyme | Synonym | Role in cancer | Cancer type | Associated biological process (involved mechanism and molecules) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Histone acetylases: the writers | ||||

| HAT1 | ||||

| HAT1 | / | Promoter | Pancreatic cancer, nasopharyngeal cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, esophageal carcinoma227–230 | Promote cell apoptosis, proliferation, differentiation and cisplatin resistance, associated with poor prognosis and upregulates PD-L1 |

| Suppressor | Lung cancer, osteosarcoma231,232 | Restores Fas expression and induces cancer cell apoptosis (Ras-ERK1/2 signaling) | ||

| GANT | ||||

| GCN5L2 | GCN5 | Promoter | Prostate cancer, breast cancer, non-small-cell lung cancer, colorectal cancer233–235 | Promotes cell proliferation, apoptosis, EMT, poor prognosis of patients, promotion of E2F1, cyclin D1, and cyclin E1 expression (PI3K/PTEN/Akt signaling, TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway) |

| PCAF | / | Suppressor | Colorectal cancer, gastric cancer, prostate cancer, breast cancer236–238 | Decreased PCAF is associated with 5-FU resistance, poor clinical outcome (PCAF-p16-CDK4 axis, p53, miR-17) |

| MYST | ||||

| HTATIP | TIP60 | Promoter | Liver cancer, prostate cancer239,240 | Promotes cancer cell EMT, metastasis, radioresistance |

| Suppressor | Breast cancer, lung cancer, bladder cancer, colorectal cancer241–243 | Is associated with cell viability and invasion, and low Tip60 expression is correlated with poor overall survival and relapse-free survival | ||

| MYST1 | MOF | Promoter | Prostate cancer244 | MYST1 increases the resistance to therapeutic regimens and promotes aggressive tumor growth (androgen receptor and NF-κB) |

| MYST2 | HBO1 | Promoter | Ovarian cancer, bladder cancer, breast cancer, pancreatic cancer, leukemia245–247 | Promotes cell proliferation, enrichment of cancer stem-like cells, gemcitabine resistance (Wnt/β-catenin signaling) |

| MYST3 | MOZ | Promoter | Colorectal cancer, breast cancer, leukemia248–250 | Promotes cell proliferation, activates ERα expression (multiple fusion proteins: MOZ-TIF2, MOZ-NCOA2 and MOZ-CBP) |

| MYST4 | MORF | Promoter | Leukemia251 | MORF-CREBBP fusion |

| p300/CBP | ||||

| P300 | EP300, KAT3B | Promoter | Laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma, leukemia, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, colorectal cancer, breast cancer, lung cancer, gastric cancer, prostate cancer, cervical cancer, pancreatic cancer252–257 | Promotes cell proliferation, migration, invasion, EMT, and malignant transformation, is associated with advanced clinical stage, poor recurrence-free survival and overall survival, enhances ERα expression and contributes to tamoxifen resistance, castration resistance, and gemcitabine sensitivity, (p21, p27, β-catenin, MLL-p300, MOZ-p300 fusion, Smad2 and Smad3 in the TGF-β signaling pathway, p300/YY1/miR-500a-5p/HDAC2 signaling axis) |

| Suppressor | Bladder cancer, colorectal cancer258,259 | Downregulation of P300 is associated with chemosensitivity to 5-FU treatment and doxorubicin resistance | ||

| CBP | CREBBP, KAT3A | Promoter | Lung cancer, leukemia, gastric cancer, ovarian cancer, prostate cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma256,260–262 | Is associated with drug resistance, a highly tumorigenic, cancer stem-like phenotype and enhances the activity of estrogen receptor-beta (ER-β) (CXCL8, PI3K/Akt/β-catenin/CBP axis); KAT6A-CREBBP, MOZ-CBP, MORF-CREBBP, MLL-CBP fusions in leukemia |

| Suppressor | Lung cancer, prostate cancer263,264 | Loss of CBP reduces transcription of cellular adhesion genes while driving tumorigenesis | ||

| SRC/p160 | ||||

| NCOA1 | SRC1 | Promoter | Prostate cancer, colon cancer, breast cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma265–267 | Promotes cell invasion, proliferation, metastasis, is associated with shorter overall survival and progression-free survival (M-CSF1, miR-4443, miR-105-1) |

| NCOA2 | TIF2 | Promoter | Prostate cancer, leukemia268,269 | Is associated with resistance to AR antagonism and bicalutamide; MOZ-TIF2 fusion in leukemia |

| Suppressor | Colorectal cancer, liver cancer270,271 | TIF2 is able to impair protumorigenic phenotypes | ||

| NCOA3 | AIB1, ACTR | Promoter | Ovarian cancer, breast cancer, bladder cancer, gastric cancer, lung cancer, prostate cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, colorectal cancer, pancreatic cancer272–275 | Promotes cell proliferation, EMT, metastasis, invasiveness and is correlated to higher estrogen receptor expression, poor PFS and OS and predicts resistance to chemoradiotherapy (AKT, E2F1, SNAI1, cyclin E, cdk2, p53, matrix metalloproteinase 2 (MMP2) and MMP9 expression); however, high AIB1 expression has been correlated to both a good response to adjuvant tamoxifen and tamoxifen resistance. |

| Others | ||||

| ATF-2 | CREB2, CREBP1 | Promoter | Pancreatic cancer, lung cancer, renal cell carcinoma, leukemia276–278 | Promotes cell proliferation, EMT, gemcitabine sensitivity (JNK1/c-Jun and p38 MAPK/ATF-2 pathways, miR-451); however, the level of ATF-2 is a key determinant of the sensitivity to tamoxifen |

| TFIIIC | / | Promoter | Ovarian cancer279 | TFIIIC is overexpressed in cancer tissues |

| TAF1 | TAFII250 | / | / | / |

| CLOCK | KIAA0334 | Promoter | Ovarian cancer, breast cancer280,281 | Promotes cell proliferation, migration, and invasion, is associated with drug resistance (cisplatin) |

| Suppressor | Lung cancer282 | Is associated with cancer progression and metastasis | ||

| CIITA | MHC2TA | Suppressor | Breast cancer, colorectal cancer, gastric cancer, head and neck cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma283–285 | Regulates the expression of MHC II and HLA-DR induction |

| MGEA5 | NCOAT | promoter | Laryngeal cancer286 | Is associated with larger tumor size, nodal metastases, higher grade and tumor behavior (TGFBR3-MGEA5 fusion) |

| Suppressor | Breast cancer287 | MGEA5 transcript levels were significantly lower in grade II and III than in grade I tumors; associated with lymph node metastasis | ||

| CDY | / | / | / | / |

| Acetyl-lysine binding protein: the readers | ||||

| BRD and extraterminal domain (BET) proteins family | ||||

| BRD2-4, BRDt | / | Promoter | Breast cancer, prostate cancer, gastric tumors, lung cancer, ovarian carcinoma, pancreatic cancer, hematologic malignancy, Ewing sarcoma, glioblastoma, melanoma288–291 | Is associated with cell proliferation, self-renewal, metabolism, metastasis, and expression of immune checkpoint molecules (oncogenic AR and MYC signaling, AMIGO2-PTK7 axis, Jagged1/Notch1 signaling, IKK activity) |

| Histone deacetylases (HDACs): the erasers | ||||

| HDAC Class I | ||||

| HDAC1 | / | Promoter | Thyroid cancer, lung cancer, ovarian cancer, breast cancer, colorectal cancer, pancreatic cancer, esophageal cancer, gallbladder cancer, prostate cancer, gastric cancer292–295 | Promotes cell invasion, viability, apoptosis, EMT; is associated with chemotherapy response. (CXCL8, P53, p38 MAPK, miRNA-34a) |

| HDAC2 | / | Promoter | Pancreatic cancer, colorectal cancer, lung cancer, squamous cell carcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, breast cancer, prostate cancer, renal carcinoma, ovarian cancer, gastric cancer296–300 | Promotes cell proliferation, metastasis, invasion, clonal expansion and EMT (E-cadherin, p63, mTORC1, AKT, PELP1/HDAC2/miR-200, p300/YY1/miR-500a-5p/HDAC2 axis, Sp1/HDAC2/p27 axis) |

| HDAC3 | / | Promoter | Colorectal cancer, pancreatic cancer, breast cancer, colorectal cancer, prostate cancer, esophageal cancer, lung cancer301–304 | Promotes cell proliferation and invasion, migration, chemosensitivity; increases PD-L1 expression (NF‑κB signaling) |

| HDAC8 | / | Promoter | Cervical cancer, breast cancer, colon cancer305–307 | Promotes cell migration, affects cell morphology and promotes the cell cycle (p53, HDAC8/YY1 axis) |

| Suppressor | Breast cancer308 | HDAC8 suppresses EMT (HDAC8/FOXA1 signaling) | ||

| HDAC Class II | ||||

| HDAC4 | / | Promoter | Head and neck cancer, breast cancer, colorectal cancer, gastric cancer, ovarian cancer, prostate cancer309–311 | Promotes cell viability, drug resensitization (tamoxifen, platinum) (STAT1, p21, miR-10b) |

| HDAC5 | / | Promoter | Breast cancer, colorectal cancer, lung cancer, prostate cancer312,313 | Promotes cell proliferation, invasion, migration and EMT; is associated with hormone therapy resistance (HDAC5-LSD1 axis, Survivin and miR-125a-5p, miR-589-5p) |

| HDAC6 | / | Promoter | Cervical cancer, breast cancer, colorectal cancer, gastric cancer, lung cancer, prostate cancer, liver cancer, ovarian cancer314–317 | Promotes pluripotency of CSCs, cancer cell proliferation and migration (α-tubulin, heat shock protein (HSP) 90, the NF-κB/MMP2 pathway, JNK/c-Jun pathway, miR-22, miR-221) |

| HDAC7 | / | Promoter | Breast cancer, colorectal cancer, prostate cancer, ovarian cancer318–320 | Is associated with cancer stem cell-specific functions, tumor growth and invasion, and therapy resistance (miR-489, miR-34a) |

| HDAC9 | / | Promoter | Breast cancer321 | Enhances invasive and angiogenic potential (miR-206) |

| Suppressor | Lung cancer322 | HDAC9 is downregulated in adenocarcinomas; is associated with tumor growth ability | ||

| HDAC10 | / | Promoter | Ovarian cancer, lung cancer323,324 | Promotes cells proliferation, reduced DNA repair capacity and sensitization to platinum therapy (AKT phosphorylation) |

| HDAC Class III: sir2-like proteins (sirtuins) | ||||

| Sirt1 | / | Promoter | Breast cancer, colorectal cancer, prostate cancer, liver cancer, lung cancer, pancreatic cancer, cervical cancer, gastric cancer, ovarian cancer325–327 | Promotes cell proliferation, migration, metastasis, EMT, metabolic flexibility and self-renewal of cancer stem cells, chemoresistance (miR-30a, miR-15b-5p) |

| Sirt2 | / | promoter | Colorectal cancer lung cancer, renal cell carcinoma, gastric cancer, cervical cancer328–330 | Highly expressed in stem-like cells and promotes migration, invasion and metastasis (p53, RAS/ERK/JNK/MMP-9 pathway) |

| Suppressor | Breast cancer, prostate cancer lung cancer331-333 | Sensitizes cancer cells to intracellular DNA damage and the cell death induced by oxidative stress, and low Sirt2 levels were associated with poor patient survival (p27) | ||

| Sirt3 | / | Promoter | Cervical cancer, lung cancer334,335 | Is associated with PD-L1-induced lymph node metastasis (p53) |

| Suppressor | Pancreatic cancer, breast cancer, prostate cancer, gastric cancer, ovarian cancer336–338 | Loss of SIRT3 leads to reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation that amplifies HIF-α stabilization; metastasis (c-MYC, CagA, PI3K/Akt pathway, Wnt/β-catenin pathway, AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK)) | ||

| Sirt4 | / | Suppressor | Pancreatic cancer, thyroid cancer, gastric cancer, colorectal cancer339,340 | Promotes cell proliferation, aerobic glycolysis, migration and invasion, and in inhibition of glutamine metabolism (E-cadherin) |

| Sirt5 | / | Promoter | Colorectal cancer, lung cancer, breast cancer341–343 | Promotes autophagy, cell proliferation, and drug resistance, and is associated with poor clinical outcomes |

| Suppressor | Liver cancer, gastric cancer344,345 | Inhibits peroxisome-induced oxidative stress (CDK2) | ||

| Sirt6 | / | Promoter | Pancreatic cancer, lung cancer, prostate cancer346–348 | Enhances cytokine production, and promotes EMT, cell migration and tumor metastasis, and predicts poor prognosis (ERK1/2/MMP9 pathway, SIRT6/Snail/KLF4 axis) |

| Suppressor | Pancreatic cancer, breast cancer, liver cancer349,350 | Promotes increased glycolysis, cancer cell proliferation and tumor growth, and is associated with paclitaxel, epirubicin, and trastuzumab sensitivity (survivin, NF-κB pathway) | ||

| Sirt7 | / | Promoter | Colorectal cancer, gastric cancer, bladder cancer351,352 | Accelerates cell growth, proliferation, motility and apoptosis (MAPK pathway) |

| Suppressor | Pancreatic cancer, breast cancer, lung cancer, colorectal cancer353–355 | Sensitizes to gemcitabine and radiotherapy, and low levels of SIRT7 are associated with an aggressive tumor phenotype and poor outcome (TGF-β signaling, p38 MAPK) | ||

| HDAC Class IV | ||||

| HDAC11 | / | Promoter | Liver cancer, Hodgkin lymphoma, neuroblastoma, colorectal cancer, prostate cancer, breast cancer, ovarian cancer356–359 | Promotes the mitotic cell cycle, cell apoptosis; is associated with cancer progression and survival (OX40 ligand, p53) |

EMT epithelial-mesenchymal transition, PI3K phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, TGF-β transforming growth factor β, ER estrogen receptor, CSF colony-stimulating factor, AR androgen receptor, MMP matrix metalloproteinase

Acetyl-lysine recognition proteins

The bromodomain (BRD) motif is an ~110-amino-acid conserved protein module and is regarded as the first and sole histone-binding module that contains a hydrophobic pocket to identify acetyl-lysine.191 The specificity of different BRDs depends on the sequences within the loops that form the hydrophobic pocket. Therefore, each BRD has a preference for different histones.192,193 In addition to their recognition of acetyl-lysine, BRDs are also capable of interacting with other chromatin molecules, such as plant homeodomain (PHD) finger motifs or another BRD. To date, 42 proteins containing bromodomains and 61 unique bromodomains have been discovered.194,195 Based on the sequence length and sequence identity of BRDs, the human BRD family can be divided into nine groups and one additional set of outliers, which has been well illustrated in published papers.169,194 Different BRD-containing proteins contain one to six BRDs. Intriguing, the most notable and well-studied bromodomain proteins are also HATs, such as PCAF, GCN5, and p300/CBP. Yaf9, ENL, AF9, Taf14, Sas5 (YEATS), and double PHD finger (DPF) have also been discovered to be acyl-lysine reader domains.191,196 Human MOZ and DPF2 are two proteins containing the DPF domain. Mutations in the YEATS and DPF domains are associated with cancer. For example, mutation of AF9 has been found in hematological malignancies, and ENL dysregulation leads to kidney cancer.197,198

Another important family is the BRD and extraterminal domain (BET) protein family, including BRD2, BRD3, BRD4, and BRDt, and this family shares two conserved N-terminal bromodomains and a more divergent C-terminal recruitment domain.199,200 These bromodomain proteins are critical as mediators of gene transcriptional activity.201 Of note, bromodomains have also been found in some histone lysine methyltransferases, such as ASH1L and MLL. BRDs are promiscuous domains and have been discussed in other well-constructed papers.169,194 In this review, we focus on the role of BRDs in tumorigenesis.

As histone acetylation “readers”, bromodomain proteins play important roles in tumorigenesis. BRD4 recruits the positive transcription elongation factor complex (P-TEFb), a validated target in chronic lymphocytic leukemia associated with c-Myc activity.202–204 Chromosomal translocation of BRD4, via the t(15;19) translocation, results in the generation of the fusion protein BRD4-NUT (nuclear protein in testis), which is found in NUT midline carcinoma (NMC). Importantly, inhibition of BRD4-NUT induces differentiation of NMC cells.205 Moreover, BRD4 is required for the maintenance of AML with sustained expression of Myc206 (Table 2).

Histone deacetylases

Histone deacetylases (HDACs) have recently attracted increasing attention. In humans, the genome encodes 18 HDACs. In contrast to the function of HATs, HDACs usually act as gene silencing mediators and repress transcription. Similarly, HDACs are expressed not only in the nucleus but also in the cytoplasm, and their substrates are also not limited to histones. Based on sequence similarity, HDACs can be divided into four classes: class I HDACs, yeast Rpd3-like proteins, are transcriptional corepressors and have a single deacetylase domain at the N-terminus and diversified C-terminal regions (HDAC1, HDAC2, HDAC3, and HDAC8); class II HDACs, yeast Hda1-like proteins, have a deacetylase domain at a C-terminal position (HDAC4, HDAC5, HDAC6, HDAC7, HDAC9, and HDAC10); class III HDACs are yeast silent information regulator 2 (Sir2)-like proteins (SIRT1, SIRT2, SIRT3, SIRT4, SIRT5, SIRT6, and SIRT7); and class IV involves one protein (HDAC11). The class IV protein shares sequence similarity with both class I and class II proteins.207,208 Classes I, II, and IV are included in the histone deacetylase family, whereas class III HDACs belong to the Sir2 regulator family.209 The catalytic mechanisms for these two families are different; classes I, II, and IV are Zn2+-dependent HDACs, whereas sir2-like proteins (sirtuins) are nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+)-dependent HDACs and are also capable of mono-ADP-ribosyltransferase activity, another pattern of histone modification.210 Intriguingly, SIRT4 is thought to have more mono-ADP-ribosyltransferase activity than HDAC activity. SIR2 and SIRT6 seem to have equal levels of both mono-ADP-ribosyltransferase and HDAC activities.211,212 Moreover, after revealing the crystal structure of SIRT5, researchers found that SIRT5 is also a lysine desuccinylase and demalonylase.213 Therefore, the diversity of the sirtuin family makes them a group of multifunctional enzymes.

So far, the major known recognition sites of each HDAC are different, and these largely remain to be uncovered. For example, HDAC3 is thought to deacetylate H4K8 and H4K12,214 but in an HDAC3-knockout HeLa cell line, the acetylation levels of H4K8 and H4K12, even the overall acetylation levels of H3 and H4, were comparable with those in wild-type cells.215 Nevertheless, HDAC1 or HDAC3 siRNA can indeed increase the acetylation levels of H3K9 and H3K18.215 Therefore, partially because of the functional complementation and diversity within HDAC families, especially in class I, II, and IV, it is difficult to identify the specific substrates of certain HDACs. However, the substrates of the sirtuin family are quite clear. It is notable that because SIRT4 and SIRT5 are only located in mitochondria, they have no effect on histones. However, nonhistone lysine acetylation is also prevalent, since more than 3600 acetylation sites on 1750 proteins have been identified.166 The tumor suppressor p53 and the cytoskeletal protein α-tubulin are two representative substrates of HDACs.216–218 Notably, HDACs are also capable of regulating gene transcription by deacetylating other proteins that are responsible for epigenetic events, such as DNMTs, HATs, and HDACs.166,219 Another phenomenon is that some HDACs have to form a complex along with other components to function as transcriptional corepressors, which provides ideas and methods to design novel HDAC inhibitors. The Sin3, NuRD, and CoREST complexes are three complexes containing HDAC1 and HDAC2. Studies have found that purified HDAC1 or HDAC2 without associated components shows fairly weak deacetylation activity in vitro.220 HDAC3 interacts with the corepressors SMRT/NCoR to form the functional complexes, which significantly increases HDAC3 activity. NCoR also interacts with HDAC1, HDAC2 and the class II deacetylases HDAC4, HDAC5, and HDAC7, but usually not in the form of a complex.221,222 Deleted in breast cancer 1 (DBC1) and active regulator of SIRT1 (AROS) are two proteins that are able to bind to SIRT1, whereas their interactions present opposite functions. The DBC1/SIRT1 complex inhibits the deacetylation activity of SIRT1, whereas the combination of AROS and SIRT1 stimulates the activity of SIRT1.223,224

HDACs not only are able to deacetylate histones and nonhistone proteins but also interact with other epigenetic-associated enzymes, which gives them a vital role in tumorigenesis.162,178 Alterations in HDACs in cancers usually result in aberrant deacetylation and inactivation of tumor suppressor genes. For example, hypoacetylation of the promoter of p21, a tumor suppressor encoded by CDKN1A, can be reversed by HDAC inhibitors, resulting in an antitumor effect.225 A screen of the mutations in several HATs and HDACs, such as CBP, PCAF, HDAC1, HDAC2, HDAC5, HDAC7, and SIRT1, in more than 180 cancer samples including primary tumors and cancer cells indicated that the expression profiles of HDAC1, HDAC5, HDAC7, and SIRT1 are distinctive for colorectal cancers and normal colorectal mucosa, and the expression profiles of HDAC4 and CBP are capable of distinguishing breast cancer tissue from normal tissues226 (Table 2).

Histone methylation (lysine and arginine)

Similar to the process of histone acetylation, histone methylation also consists of three important components: “writers”, histone methyltransferases (HMTs), “readers”, histone methylation-recognizing proteins, and “erasers”, histone demethylases (HDMs). Methylation of histones occurs at arginine and lysine residues. Arginine and lysine both can be monomethylated or dimethylated, whereas lysine is also capable of being trimethylated. Histone methylation can either promote or inhibit gene expression, which depends on the specific situation. For example, lysine methylation at H3K9, H3K27, and H4K20 is generally associated with suppression of gene expression, whereas methylation of H3K4, H3K36, and H3K79 induces gene expression.360 Mutation of H3K27M (lysine 27 to methionine) and H3K36M are two important oncogenic events, and H3K27M and H3K36M serve as drivers of pediatric gliomas and sarcomas. H3K27M has been identified in more than 70% of diffuse intrinsic pontine gliomas (DIPGs) and 20% of pediatric glioblastomas, which results in a global reduction in the trimethylation of H3K27 (H3K27me3).361–363 However, the H3K36M mutation impairs the differentiation of mesenchymal progenitor cells and generates undifferentiated sarcoma, leading to increased levels of H3K27me3 and global loss of H3K36 (me2 and me).364,365 Meanwhile, depletion of H3K36 methyltransferases results in similar phenotypes to those seen with H3K36M mutation.364 To date, KMTs (lysine methyltransferases) have been better studied than arginine methyltransferases (PRMTs) due to their sequence of discovery, different prevalence and impact. Their targets are not limited to only histones, they also modify other key proteins, such as the tumor suppressor p53, TAF10, and Piwi proteins.366–368

Histone methyltransferases

All KMTs contain a 130-amino-acid conserved domain, the SET (suppressor of variegation, enhancer of Zeste, trithorax) domain, except for DOT1L. The SET domain is responsible for the enzymatic activity of SET-containing KMTs. Instead of methylating lysine residues in histone tails, DOT1L methylates lysine in the globular core of the histone, and its catalytic domain is more similar to that of PRMTs.369,370 The enzymatic activity of KMTs results in the transfer of a methyl group from S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) to a the ε-amino group of a lysine residue. The first identified KMT was SUV39H1, which targets H3K9.371 Sequentially, more than 50 SET-containing proteins have been identified with proven or predicted lysine methylation potential. Of note, KMTs are highly specific enzymes, meaning that they are highly selective for lysine residues they can methylate and the specific methylation degree they can achieve. For example, SUV39H1 and SUV39H2 specifically methylate histone 3 at lysine 9 (H3K9), and DOT1L only methylates H3K79.371 Based on their structure and sequence around the SET domain, generally, KMTs can be divided into six groups, SUV39, SET1, SET2, EZH, SMYD, and RIZ (PRDM) (reviewed by Volkel and Angrand372). The Pre-SET domain of the SUV39 family contains nine conserved cysteines that coordinate with three zinc ions to function. The SET1 family members share a similar Post-SET motif that contains three conserved cysteine residues. The SET2 family possesses an AWS motif that contains 7–9 cysteines. Their SET domain is located between the AWS motif and a Post-SET motif. The members of the enhancer of zeste homolog (EZH) family are the catalytic components of polycomb repressive complexes (PRCs), which are responsible for gene silencing. EZH proteins have no Post-SET motif but have 15 cysteines in front of the SET domain and show no methylated activity as isolated proteins.373 PRC2 shows lysine methylation activity through its catalytic components, EZH2 or its homolog EZH1.374 EZH2 can methylate not only histone H3 but also histone H1 at lysine 26.375 The SMYD family members, which are SET and MYND domain-containing proteins, possesses a MYND (myeloid-nervy-DEAF1) domain, a zinc-finger motif responsible for protein–protein interaction.376 The RIZ (PRDM) family is a large family containing a homolog of the SET domain, the PR domain. The PR and SET domains share 20–30% sequence identity and are both capable of inducing histone H3 methylation.377 However, most members of the RIZ family responsible for histone methylation are still unknown. So far, two of them have been proven to induce the methylation of histones: PRDM2 (RIZ1) is associated with H3K9 methylation; and Meisetz, the mouse homolog of PRDM9, trimethylates H3K4.378 Meanwhile, PRDM1 has been identified to interact with EHMT2, a member of the SUV39 family. PRDM6 acts as a transcription suppressor by interacting with class I HDACs and EHMT2 to induce cell proliferation and inhibit cell differentiation.379 Meanwhile, the recruitment of EHMT2 is based on the formation of a complex with PRDM1.380 Due to the lack of a characteristic sequence or structure flanking the SET domain, other SET-containing KMTs, such as SET7/9, SET8, SUV4-20H1, and SUV4-20H2, cannot be classified into these families. Notably, some KMTs contain more than one domain, which allows them to interact with other proteins, especially other epigenetic modifying proteins. SUV39H1 possesses a chromodomain that directly binds to nucleic acids and forms heterochromatin.381 MLL1 recognizes unmethylated DNA through its CpG-interacting CXXC domain. SETDB1 contains an MBD that interacts with methylated DNA.382 The Tudor domain in SETDB1 may potentially recognize the methylation of lysine residues.383 ASH1 is able to interact with CBP, a HAT, via a bromodomain within ADH1.384

Protein arginine methyltransferases (PRMTs) can be divided into two groups. Among the nine PRMTs, only PRMT5, PRMT7, and PRMT9 are type II PRMTs, and the other five PRMTs, except for PRMT2, are type I PRMTs. PRMT2 was identified by sequence homology385 but has not shown any catalytic activity during investigations, although PRMT2 acts as a strong coactivator for androgen receptor (AR), which is thought to be associated with arginine methylation.386 Both types of PRMTs first catalyze the formation of monomethylarginine as an intermediate. However, sequentially, type I PRMTs can form asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA, Rme2a), but type II PRMTs form symmetric dimethylarginine (SDMA, Rme2s). Rme2a means two methyl groups on one ω-amino group, whereas an Rme2s has one methyl group on each ω-amino group. PRMT1-PRMT8 were investigated by Herrmann and Fackelmayer,387 and FBXO11 was identified as PRMT9, which symmetrically dimethylates arginine residues.388

Most enzymes for histone methylation are substrate-specific proteins; therefore, alterations in the aberrant expression of enzymes are usually associated with specific histone residue mutations. One of the best-known examples of alterations in tumorigenesis is H3K4me3, which is associated with biphenotypic (mixed lineage) leukemia (MLL). The location of the MLL gene is where chromosomal translocations in AML and ALL usually occur.389 When the MLL gene is translocated, the catalytic SET domain is lost, which results in MLL translocation-generated fusion proteins, which recruit DOT1L.390 Maintenance of MLL-associated ALL depends on the methylation of H3K79 catalyzed by DOT1L.391 Therefore, DOT1L is usually associated with hematological malignancies rather than solid tumors. Alteration of the EZH2-induced methylation of H3K27 has been observed in multiple cancers, including various solid tumors (prostate, breast, kidney, bladder, and lung cancers) and hematological malignancies.392 Meanwhile, overexpression of EZH2 has been found in multiple cancers and is associated with poor prognosis.393 Different mechanisms have been proposed to describe the role of EZH2 in tumorigenesis (Table 3).

Table 3.

Important enzymes or proteins that regulate histone methylation in cancer.

| Enzymes | Synonyms | Role in cancer | Cancer type | Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Histone methyltransferases (lysine): the writers for lysine | ||||

| SUV39 | ||||

| KMT1A | SUV39H1, MG44, SUV39H | Promoter | Gastric cancer, prostate cancer, breast cancer, lung cancer, colorectal cancer, bladder cancer421–426 | Promotes cell migration and cancer stem cell self-renewal (KMT1A-GATA3-STAT3 axis) |

| Suppressor | Breast cancer, cervical cancer427,428 | SUV39H1-low tumors are correlated with poor clinical outcomes | ||

| KMT1B | FLJ23414, SUV39H2 | Promoter | Colorectal cancer, lung cancer, gastric cancer429–431 | Promotes cell proliferation, migration and invasion and tumor metastasis |

| KMT1C | EHMT2, G9A, BAT8, NG36 | Promoter | Breast cancer, pancreatic cancer, bladder cancer, ovarian cancer, liver cancer, colon cancer, lung cancer432–435 | Promotes cell proliferation, metastasis, and apoptosis, and is associated with poor prognosis (p27, PMAIP1-USP9X-MCL1 axis, Wnt signaling pathway) |

| KMT1E | SETDB1, ESET, KG1T | Promoter | Breast cancer, colorectal cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, liver cancer436–439 | SETDB1 promotes cell proliferation, migration, invasion, and EMT (p53) |

| Suppressor | Lung cancer440 | SETDB1 acts as a metastasis suppressor, and inhibits cell migration and invasive behavior. | ||

| SET1 | ||||

| KMT2A | MLL1, HRX, TRX1, ALL-1 | Promoter | Head and neck cancer, pancreatic cancer, prostate cancer441,442 | Promotes PD-L1 transcription and is associated with the self-renewal of cancer cells (Wnt/β-catenin pathway) |

| KMT2B | ALR, MLL2 | promoter | Bladder cancer, lung cancer, breast cancer443–445 | Is associated with the self-renewal of CSCs and expansion (Wnt/β-catenin pathway) |

| KMT2C | MLL3, HALR | Suppressor | Colorectal cancer, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma446 | Inhibits tumor growth and metastasis |

| KMT2D | MLL4, HRX2 | Promoter | Breast cancer447 | Promotes cell proliferation and invasiveness |

| KMT2E | MLL5 | Promoter | Glioblastoma448 | Is associated with cancer cell self-renewal |

| KMT2F | SET1A | Promoter | Liver cancer449 | Promotes liver cancer growth and hepatocyte-like stem cell malignant transformation |

| EZH | ||||

| EZH1 | KIAA0388 | Promoter | Breast cancer, prostate cancer, bladder cancer, colorectal cancer, liver cancer, gastric cancer, melanoma, lymphoma, myeloma, Ewing’s sarcoma, glioblastoma, thyroid carcinoma, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, lung cancer, ovarian cancer, renal cancer392,450–452 | Promotes cell proliferation, colony formation, migration and tumor metastasis; is associated with cancer stem cell maintenance; predicts chemotherapeutic efficacy and response to tamoxifen therapy (E-cadherin, RUNX3, MEK-ERK1/2-Elk-1 pathway) |

| EZH2 | KMT6, ENX-1, MGC9169 | |||

| SET2 | ||||

| KMT3A | SETD2, SET2, HIF-1, | Suppressor | Renal cancer, lung cancer453,454 | Maintains genome integrity and attenuates cisplatin resistance (ERK signaling pathway) |

| WHSC1 | NSD2, WHS, TRX5 | Promoter | Prostate cancer, gastric cancer455,456 | Promotes cell invasive properties, EMT and cancer metastasis |

| WHSC1L1 | NSD3, MGC126766 | Promoter | Breast cancer, head and neck cancer457 | Is associated with ERα overexpression and enhances the oncogenic activity of EGFR |

| RIZ (PRDM) | ||||

| PRDM1 | BLIMP1 | Promoter | Pancreatic cancer, breast cancer458,459 | Promotes cell invasiveness and cancer metastasis |

| Suppressor | Lung cancer, colon cancer460,461 | Inhibits cell invasion and metastasis (p21) | ||

| PRDM2 | RIZ | Promoter | Colorectal cancer, breast cancer462,463 | Is associated with poor clinicopathological variables and mediates the proliferative effect of estrogen |

| PRDM3 | EVI1, MDS1-EVI1 | Promoter | Ovarian cancer, nasopharyngeal carcinoma464,465 | Promotes cell proliferation, migration, EMT, cancer stem cells and chemoresistance/radioresistance |

| PRDM4 | PFM1 | Promoter | Breast cancer466 | Is associated with cancer cell stemness, tumorigenicity, and tumor metastasis |

| PRDM5 | PFM2 | Suppressor | Colorectal cancer, gastric cancer, cervical cancer467 | Among the PRDM family genes tested, PRDM5 was the most frequently silenced in colorectal and gastric cancer |

| PRDM9 | PFM6 | Promoter | N/A468 | Impairs genomic instability and drives tumorigenesis |

| PRDM14 | PFM11 | Promoter | Testicular cancer, pancreatic cancer469,470 | Is associated with early germ cell specification and promotes cancer stem-like properties and liver metastasis |

| PRDM16 | MEL1, PFM13 | promoter | Gastric cancer471 | Inhibits TGF-beta signaling by stabilizing the inactive Smad3-SKI complex |

| SMYD | ||||

| KMT3C | SMYD2 | Promoter | Pancreatic cancer, gastric cancer, breast cancer, lung cancer472,473 | Promotes cancer cell proliferation and survival (STAT3, EML4-ALK, p65) |

| KMT3E | SMYD3, ZMYND1, ZNFN3A1, FLJ21080 | Promoter | Liver and colon cancer, prostate cancer, breast cancer474–476 | Promotes cell proliferation, invasion, EMT and cancer stem cell maintenance (Myc, MMP-9, Ctnnb1, JAK/Stat3 pathway, Wnt pathway, androgen receptor transcription) |

| SMYD4 | ZMYND21 | Suppressor | Breast cancer477 | SMYD4 acts as a suppressor in tumorigenesis |

| Others | ||||

| DOT1L | KMT4 | promoter | MLL-rearranged leukemia, colorectal cancer, breast cancer, ovarian cancer391,478,479 | Increases EMT, cancer stemness and tumorigenic potential and is required for MLL rearrangement |

| SET8 | KMT5A, SETD8, PR-set7 | promoter | Breast cancer, prostate cancer, ovarian cancer, lung cancer480,481 | Promotes cell proliferation, migration, invasion, and EMT (MiR-502) |

| SUV4-20H2 | KMT5C, MGC2705 | Suppressor | Breast cancer482 | SUV4-20H2 is downregulated in breast cancer |

| SetD6 | / | Promoter | Colorectal cancer, bladder cancer, breast cancer483,484 | Promotes cell survival and colony formation and contributes to increased susceptibility to cancer |

| SET7/9 | SETD7, KMT7 | Suppressor | Breast cancer, gastric cancer, AML, lung cancer485–487 | Promotes cell proliferation, EMT and the generation of cancer stem cells; a low level of SET7/9 is correlated with clinical aggressiveness and worse prognosis (β-catenin stability) |

| Histone methyltransferases (arginine): the writers for arginine | ||||

| PRMT1 | ANM1, HCP1, IR1B4 | Promoter | Breast cancer, colon cancer, gastric cancer, lung cancer488–490 | Promotes EMT, cancer cell migration, and invasion and is associated with chemosensitivity and poor clinical and histological parameters |

| Suppressor | Pancreatic cancer491 | Inhibits cell proliferation and invasion in pancreatic cancer | ||

| PRMT2 | / | Suppressor | Breast cancer492 | Induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in breast cancer |

| PRMT4 | CARM1 | Promoter | Ovarian cancer, breast cancer, liver cancer, colorectal cancer, prostate cancer450,493,494 | Promotes cell proliferation and blocks cell differentiation (Wnt/β-catenin signaling) |

| Suppressor | Pancreatic cancer495 | Inhibits glutamine metabolism and suppresses cancer progression | ||

| PRMT5 | JBP1, SKB1, IBP72 | Promoter | Breast cancer, prostate cancer, colorectal cancer, lung cancer496–498 | Promotes cell survival, proliferation, invasiveness and sensitivity to 5-Fluorouracil (5-FU) (SHARPIN-PRMT5-H3R2me1 axis) |

| Suppressor | Breast cancer499 | High PRMT5 expression favors a better prognosis in BC patients | ||

| PRMT6 | HRMT1L6 | Promoter | Prostate cancer, gastric cancer500,501 | Is associated with cell apoptosis, invasiveness and viability (PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, H3R2me2as) |

| Suppressor | Hepatocellular carcinoma502 | Negatively correlates with aggressive cancer features | ||

| PRMT7 | FLJ10640, KIAA1933 | Promoter | Lung cancer, breast cancer503,504 | Promotes cancer cell EMT and tumor metastasis |

| PRMT8 | HRMT1L3, HRMT1L4 | Promoter | Breast, ovarian and gastric cancer505 | Overexpression of PRMT8 is correlated with decreased patient survival |

| PRMT9 | FBXO11 | Promoter | Breast cancer506 | Fuels tumor formation via restraint of the p53/p21 pathway |

| Methyl-histone recognition proteins: the readers | ||||

| Chromodomain | ||||

| HP1 | / | Promoter | Breast cancer507 | Overexpression of HP1 is associated with breast cancer progression |

| Chd1 | / | Promoter | Prostate cancer508 | Is associated with cell invasiveness, double-strand break repair and response to DNA-damaging therapy |

| Suppressor | Prostate cancer509 | Loss of MAP3K7 and CHD1 promotes an aggressive phenotype in prostate cancer | ||

| WD40 repeat domain | ||||

| WDR5 | / | / | / | |

| MBT domain | ||||

| BPTF | / | Promoter | Lung cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma510,511 | Promotes cell proliferation, migration, stem cell-like traits and invasion (miR-3666) |

| L3MBTL1 | / | Suppressor | Breast cancer512 | Expression of L3MBTL1 is associated with a low risk of disease recurrence and breast cancer-related death |

| ING2 | Promoter | Colon cancer513 | Increases invasion by enhancing MMP13 expression | |

| Suppressor | Lung cancer514 | Suppresses tumor progression via regulation of p53 | ||

| BHC80 | Promoter | Prostate cancer515 | Stimulates cell proliferation and tumor progression via the MyD88-p38-TTP pathway | |

| Tudor domains | ||||

| JMJD2A | Promoter | Breast cancer, liver cancer, colon cancer516,517 | Promotes cells apoptosis and proliferation and contributes to tumor progression (ARHI, miR372) | |

| Suppressor | Bladder cancer518 | Low JMJD2A correlates with poor prognostic features and predicts significantly decreased overall survival | ||

| KDMs: the erasers | ||||

| KDM1 | ||||

| KDM1A | LSD1 | Promoter | Breast cancer, lung cancer, prostate cancer, liver cancer, pancreatic cancer, gastric cancer519–521 | Contributes to cell proliferation and stem cell maintenance and self-renewal (p21, AR, HIF1α-dependent glycolytic process) |

| Suppressor | Breast cancer522 | Inhibits invasion and metastatic potential | ||

| KDM1B | LSD2 | Promoter | Breast cancer523 | Contributes to cancer progression and cancer stem cell enrichment |

| KDM2/JHDM1 | ||||

| KDM2A | JHDM1A, CXXC8 | Promoter | Breast cancer, gastric cancer, lung cancer, cervical cancer524–526 | Promotes cancer cell proliferation, metastasis, and invasiveness (HDAC3, TET2) |

| KDM2B | JHDM1B, FBXL10, | Promoter | Prostate cancer, breast cancer, gastric cancer527,528 | Promotes cell migration, angiogenesis, and the self-renewal of cancer stem cells |

| KDM3/JHDM2/JMJD1 | ||||

| KDM3A | JHDM2A, JMJD1A | Promoter | Colorectal cancer, ovarian cancer, breast cancer, prostate cancer, bladder cancer529–531 | Promotes cancer cell growth, metastasis, stemness and chemoresistance (c-Myc, Wnt/β-catenin signaling, glycolysis, HIF1α) |

| KDM3C | JHDM2C, JMJD1C | Promoter | Esophageal cancer, colorectal cancer532,533 | Promotes cancer cell proliferation and metastasis (YAP1 signaling, ATF-2) |

| KDM4/JHMD3/JMJD2 | ||||

| KDM4A | JHDM3A, JMJD2A | Promoter | Breast cancer, liver cancer516,534 | Promotes cancer progression through repression of the tumor suppressor ARHI (miR372) |

| Suppressor | Bladder cancer518 | Downregulated in cancer tissues and significantly decreases as cancer progresses | ||

| KDM4B | JMJD2B | Promoter | Breast cancer, gastric cancer, ovarian cancer, colorectal cancer, prostate cancer535–537 | Promotes EMT and metastasis, and regulates the seeding and growth of peritoneal tumors; is involved in resistance to PI3K inhibition (p-ERK, β-catenin) |

| KDM4C | JMJD2C, GASC1 | Promoter | Breast cancer, pancreatic cancer538,539 | Promotes cancer progression (HIF-1α, miR-335-5p) |

| KMD4D | JMJD2D | Promoter | Colorectal cancer540 | Promotes cell proliferation and tumor growth (β-catenin) |

| KDM5/JARID | ||||

| KDM5A | JARID1A, RBP2 | Promoter | Breast cancer, colorectal cancer, cervical cancer541,542 | Promotes proliferative activity and invasion, and inhibition of KDM5A causes growth arrest at the G1 phase (c-Myc) |

| KDM5B | JARID1B, RBP2-like | Promoter | Colorectal cancer, lung cancer, gastric cancer543 | Promotes cell proliferation, metastasis, and expression of CSCs, and inhibition of KDM5B results in cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, and senescence (E2F/RB pathway) |

| KDM5C | JARID1C, SMCX | Promoter | Prostate cancer, lung cancer544 | Overexpression of KDM5C predicts therapy failure and is associated with cancer cell growth, migration and invasion |

| Suppressor | Colon cancer545 | Inhibits the multidrug resistance of colon cancer cell lines by downregulating ABCC1 | ||

| KDM5D | JARID1D, SMCY | Promoter | Gastric cancer546 | Promotes cell proliferation and EMT |

| Suppressor | Prostate cancer547 | Loss of KDM5D expression induces resistance to docetaxel | ||

| JARID2 | JUMONJI | Promoter | Bladder cancer, lung and colon cancers548,549 | Regulates cancer cell EMT and stem cell maintenance and is associated with poor survival |

| Suppressor | Prostate cancer550 | Inhibits cell proliferation, migration, and tumor development via inhibition of Axl | ||

| KDM6/UT | ||||

| KDM6A | UTX | Promoter | Breast cancer447 | Promotes cell proliferation and invasiveness |

| Suppressor | Bladder cancer, pancreatic cancer551,552 | KDM6A loss induces squamous-like, metastatic pancreatic cancer | ||

| KDM6B | JMJD3 | Promoter | Ovarian cancer, breast cancer, gastric cancer553,554 | High expression of KDM6B is correlated with poor prognosis |

| KDM6C | UTY | Suppressor | Bladder cancer555 | UTY-knockout cells have increased cell proliferation compared to wild-type cells |

| KDM7/PHF | ||||

| KDM7A | JHDM1D | Promoter | Prostate cancer556 | Promotes cell proliferation and upregulated androgen receptor activity |

| KDM7C | PHF2, JHDM1E | Suppressor | N/A420 | Is a suppressor and promotes p53-driven gene expression |

| KDM7B | PHF8, JHDM1F | Promoter | Prostate cancer, gastric cancer, lung cancer, leukemia, colorectal cancer557–559 | Promotes cell proliferation, migration and invasion, and high PHF8 expression predicts poor survival (miR-488) |

| Others | ||||

| JMJD5 | KDM8 | Promoter | Breast cancer560,561 | Promotes metastasis and indicates a poor prognosis; is required for cell cycle progression via because of its actions in the cyclin A1 coding region. |

| RSBN1 | KDM9 | Promoter | Breast cancer562 | Is a new potential HIF target |

| JMJD6 | PSR, PTDSR | Promoter | Breast cancer, oral cancer, lung cancer563–565 | Promotes cancer cell proliferation, EMT and motility, and maintains cancer cell stemness properties (autophagy pathway, WNT/β-catenin pathway) |