Physiological acclimation to elevated CO2 will intensify cyanobacterial blooms in lakes.

Abstract

Although phenotypic plasticity is a widespread phenomenon, its implications for species responses to climate change are not well understood. For example, toxic cyanobacteria can form dense surface blooms threatening water quality in many eutrophic lakes, yet a theoretical framework to predict how phenotypic plasticity affects bloom development at elevated pCO2 is still lacking. We measured phenotypic plasticity of the carbon fixation rates of the common bloom-forming cyanobacterium Microcystis. Our results revealed a 1.8- to 5-fold increase in the maximum CO2 uptake rate of Microcystis at elevated pCO2, which exceeds CO2 responses reported for other phytoplankton species. The observed plasticity was incorporated into a mathematical model to predict dynamic changes in cyanobacterial abundance. The model was successfully validated by laboratory experiments and predicts that acclimation to high pCO2 will intensify Microcystis blooms in eutrophic lakes. These results indicate that this harmful cyanobacterium is likely to benefit strongly from rising atmospheric pCO2.

INTRODUCTION

Phenotypic plasticity is one of the major challenges in the study of how organisms will respond to environmental change (1–3). Phenotypic plasticity implies that the traits of organisms are not constant, as the same genotype may display different phenotypes depending on the prevailing environmental conditions. For example, the temperature and CO2 response of a species may vary depending on the climatic conditions to which individuals of this species have been previously exposed (3, 4). Taking the phenotypic plasticity of traits into account is therefore essential for accurate predictions of how species will respond to climate change.

Cyanobacterial blooms appear to increase in frequency, intensity, and duration in many eutrophic lakes, reservoirs, and estuaries, often in association with increasing nutrient loads, changes in land use, and global warming (5–8). Dense cyanobacterial blooms can have severe environmental impacts, as bloom-forming species are able to produce a variety of potent toxins affecting birds and mammals including humans, and may therefore negatively affect the use of water for recreation, drinking water, and fisheries (8–10). Recent research indicates that surface blooms of cyanobacteria may benefit not only from high temperatures but also directly from the increase in partial pressure of carbon dioxide (pCO2) in the atmosphere (11–13). The photosynthetic activity of dense cyanobacterial blooms depletes dissolved CO2 concentrations in the upper water column and increases pH (11, 14), thereby shifting the inorganic carbon equilibrium toward bicarbonate (HCO3−) and carbonate (CO32−). Rising atmospheric pCO2 in combination with depletion of the dissolved CO2 concentration by surface blooms will increase the pCO2 gradient across the air-water interface. This may result in an enhanced influx of CO2 into the water column (15) that fuels the photosynthetic carbon fixation of cyanobacterial blooms (11, 13).

Phenotypic plasticity is likely to play an important role in the response of cyanobacterial blooms to rising CO2. Cyanobacteria use a sophisticated CO2-concentrating mechanism (CCM) (16, 17). Most inorganic carbon taken up by the cells is first converted to bicarbonate and then transported to cellular compartments called carboxysomes, where bicarbonate is converted back to CO2 and fixed into organic carbon by the RuBisCO enzyme. The cyanobacterial CCM comprises up to five different carbon uptake systems, including two CO2 uptake systems (NDH-13 and NDH-14) and three bicarbonate uptake systems (BCT1, BicA, and SbtA) (18). These uptake systems differ in kinetic properties. For example, BicA has a low affinity for bicarbonate but high flux rate, whereas SbtA has a high affinity but low flux rate (18, 19). Moreover, cyanobacteria may combine and regulate these uptake systems in different ways (12, 18–20). Also, the number of carboxysomes per cell may vary in response to changes in CO2 availability (21). This flexibility of the CCM creates the potential for a high degree of phenotypic plasticity of carbon fixation rates in cyanobacterial blooms.

Thus far, phenotypic plasticity of CO2 and bicarbonate uptake kinetics have been quantified for only a limited number of cyanobacteria. This includes the freshwater laboratory strains Synechocystis PCC 6803 (22) and Synechococcus PCC 7942 (23, 24), as well as the marine cyanobacteria Trichodesmium IMS101 (25) and Prochlorococcus MED4 (26). However, phenotypic plasticity of the carbon uptake kinetics of bloom-forming freshwater cyanobacteria is essentially unknown, and a methodology to incorporate this plasticity into predictive models of cyanobacterial and other harmful algal blooms is still lacking.

Here, we develop a novel theoretical framework to predict how phenotypic plasticity will affect the proliferation of cyanobacteria in response to rising atmospheric pCO2. For this purpose, we investigate phenotypic plasticity of the carbon uptake kinetics of Microcystis, one of the most ubiquitous and notorious bloom-forming cyanobacteria (8, 27). Two toxic Microcystis strains were cultured in the laboratory to measure their CO2 and bicarbonate uptake kinetics after acclimation to low and to high pCO2 (Fig. 1, A and B). The observed phenotypic plasticity of the kinetic parameters was implemented in a mathematical model to predict cyanobacterial growth and dynamic changes in CO2 uptake and inorganic carbon chemistry (Fig. 1, C and D). The model predictions were validated using controlled laboratory chemostat experiments exposed to low and to high pCO2 (Fig. 1E). Subsequently, the validated model was scaled up from the laboratory to eutrophic lakes to predict how physiological acclimation of the carbon fixation rates will affect the response of Microcystis blooms to rising atmospheric pCO2 (Fig. 1F).

Fig. 1. Conceptual approach of this study.

(A) Microcystis strains were grown at low and at high pCO2 in laboratory chemostats. (Photo credit: Xing Ji, University of Amsterdam.) (B) Carbon uptake kinetics of Microcystis cells acclimated to low and high pCO2 were measured, and (C) the plasticity of the measured uptake kinetics was incorporated in a mathematical model. (D) The model was used to predict dynamic changes in population density, uptake kinetics, and inorganic carbon chemistry, and (E) these predictions were validated by the chemostat experiments. (F) The validated model was scaled up to lakes to predict how phenotypic plasticity of Microcystis affects its bloom development in response to rising atmospheric pCO2. This photo shows a large Microcystis bloom in Lake Taihu, China. (Photo credit: Xing Ji, University of Amsterdam.)

RESULTS

Phenotypic plasticity of carbon uptake kinetics

Microcystis strains PCC 7806 and PCC 7941 were grown in laboratory chemostats provided with nutrient-rich medium and aerated with either low pCO2 [100 parts per million (ppm)] or high pCO2 (1000 ppm). These pCO2 settings reflect the wide variation in dissolved CO2 concentrations in lakes, ranging from CO2-undersaturated to CO2-supersaturated waters (11, 28). After the chemostats were in steady state for ~20 days, we took samples to measure CO2 and bicarbonate uptake kinetics of the Microcystis cells with a membrane inlet mass spectrometer (MIMS) using a chemical disequilibrium assay (29, 30). With a dilution rate of 0.2 day−1, the experiments allowed for ~6 generations of physiological acclimation to the imposed CO2 conditions, which is comparable to the time scale of cyanobacterial bloom development. The results show that the carbon uptake kinetics of Microcystis cells acclimated to high pCO2 were very different from the uptake kinetics of cells acclimated to low pCO2 (Fig. 2 and fig. S1 for Microcystis PCC 7806 and PCC 7941, respectively).

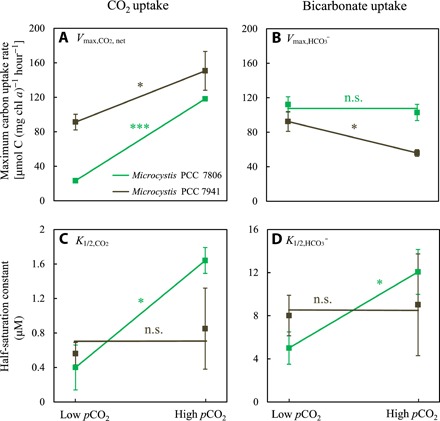

Fig. 2. Carbon uptake kinetics of Microcystis PCC 7806 acclimated to either low or high pCO2.

(A and B) Net CO2 uptake rate as function of the dissolved CO2 concentration, after acclimation to (A) low pCO2 and (B) high pCO2. (C and D) Bicarbonate uptake rate as function of the bicarbonate concentration, after acclimation to (C) low pCO2 and (D) high pCO2. Carbon uptake kinetics were measured after ~20 days of acclimation to the steady-state conditions in the chemostats. Measurements were replicated fourfold at low pCO2 and threefold at high pCO2, as indicated by the different colors. Lines are Michaelis-Menten fits to each of the replicates (see table S2 for parameter estimates). Insets zoom in at the carbon uptake kinetics at low dissolved CO2 and bicarbonate concentrations.

To quantify the uptake kinetics, the measured CO2 and bicarbonate uptake rates (V) were fitted to the Michaelis-Menten equation

| (1) |

where [C] is the CO2 or bicarbonate concentration, Vmax is the maximum uptake rate, and K1/2 is the half-saturation constant (i.e., the carbon concentration at which the uptake rate equals half of Vmax). The ratio Vmax/K1/2 represents the initial slope of the uptake kinetics at [C] = 0 and provides a measure of the uptake efficiency at low carbon concentration.

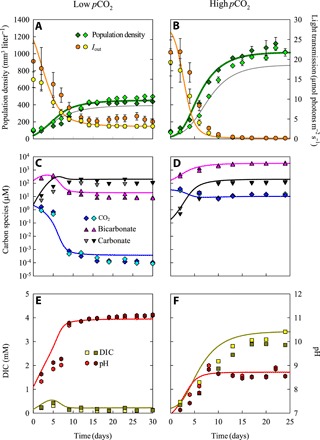

For Microcystis PCC 7806, the maximum net CO2 uptake rate (Vmax,CO2,net) was more than five times higher at high pCO2 than at low pCO2, whereas the maximum bicarbonate uptake rate (Vmax,HCO3) was not significantly affected by pCO2 (Fig. 2; Fig. 3, A and B). Half-saturation constants for CO2 and bicarbonate uptake were both significantly higher in cells acclimated to high pCO2 (Fig. 3, C and D). The CO2 uptake efficiency (i.e., the initial slopes in the insets of Fig. 2, A and B) was not much affected by pCO2. The bicarbonate uptake efficiency, however, was almost three times lower at high pCO2 than at low pCO2 (insets in Fig. 2, C and D).

Fig. 3. Reaction norms of the carbon uptake kinetics of Microcystis PCC 7806 and PCC 7941.

The reaction norms show the plasticity of maximum uptake rates of (A) CO2 (Vmax,CO2,net) and (B) bicarbonate (Vmax,HCO3) and the plasticity of half-saturation constants for (C) CO2 (K1/2,CO2) and (D) bicarbonate (K1/2,HCO3), in response to acclimation to either low or high pCO2. Data points show parameter values ± SD obtained by Michaelis-Menten fits to replicated measurements of the carbon uptake kinetics (see Fig. 2 and fig. S1; n = 4 for low pCO2 and n = 3 to 4 for high pCO2). Significant differences between parameter values at low pCO2 and high pCO2 were assessed using the independent-samples t test corrected for multiple hypothesis testing (***P < 0.001; *P < 0.05; n.s., not significant). Statistical details are reported in table S3.

For Microcystis PCC 7941, Vmax,CO2,net was 1.8 times higher, whereas Vmax,HCO3 was ~40% lower at high than at low pCO2 (fig. S1 and Fig. 3, A and B). Its half-saturation constants for CO2 and bicarbonate uptake were not significantly affected by pCO2 (Fig. 3, C and D).

Hence, after acclimation to high pCO2, both Microcystis strains achieved much higher maximum CO2 uptake rates, but they became less efficient in bicarbonate uptake through either an increased half-saturation constant or a reduced maximum bicarbonate uptake rate.

Modeling phenotypic plasticity

We incorporated the observed plasticity of the carbon uptake kinetics into a mathematical model. The model considers quantitative plastic traits and assumes that trait values dynamically adjust to the prevailing environmental conditions. If x denotes the value of a plastic trait (such as Vmax and K1/2), then dynamic changes of this trait value are described as

| (2) |

where the function f[CO2] describes the acclimated trait value as a function of the dissolved CO2 concentration, x(t) is the actual trait value at time t, and c is the acclimation rate. The function f[CO2] is replaced by for traits involved in bicarbonate uptake. We assume that the function f has an S-shaped form, such that the acclimated trait value is bound between physiological limits, xlow and xhigh (Fig. 1C; see section S2 for details).

All traits significantly affected by pCO2 in the experiments are considered to be plastic. For instance, in our application, the plastic traits of Microcystis PCC 7806 are its maximum CO2 uptake rate and half-saturation constants for CO2 and bicarbonate (Fig. 3). The physiological limits of these traits are set at the trait values observed at low and at high pCO2.

The resultant description of the phenotypic plasticity of the carbon uptake kinetics was combined with dynamic equations describing population growth and the feedbacks of population growth on inorganic carbon chemistry, light, nutrients, pH, and alkalinity (see section S2 for details).

Validating the model in laboratory experiments

To test the model predictions, we ran duplicate chemostat experiments with Microcystis PCC 7806 at both low and high pCO2 (Fig. 1A). The Microcystis populations increased during the first 2 weeks of the experiments, reducing light availability, modifying inorganic carbon chemistry, and increasing pH, after which the cyanobacterial populations and other experimental variables approached a steady state (Fig. 4). The steady states were maintained for several weeks. Microcystis PCC 7806 produced much higher steady-state population densities at high than at low pCO2 (Fig. 4, A and B, and table S1). In the experiments at low pCO2, the photosynthetic activity of Microcystis depleted the dissolved CO2 concentration to the nanomolar range and diminished the bicarbonate concentration to ~10 μM, while carbonate became the dominant inorganic carbon species (Fig. 4C). This was accompanied by a strong pH increase to ~11 (Fig. 4E). Conversely, in the experiments at high pCO2, dissolved CO2 was maintained at ~10 μM, bicarbonate increased to ~3000 μM, and pH remained <9 (Fig. 4, D and F).

Fig. 4. Population density, inorganic carbon chemistry, and pH in chemostat experiments with Microcystis PCC 7806 at low and at high pCO2.

Chemostat experiments were performed in duplicate, at low pCO2 (left) and at high pCO2 (right). (A and B) Microcystis population density (n = 3 technical replicates per chemostat) and light intensity Iout transmitted through the chemostat (n = 10). (C and D) Dissolved CO2, bicarbonate, and carbonate concentrations. (E and F) Dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) and pH (n = 3 technical replicates per chemostat). Symbols indicate experimental data of the duplicate chemostat experiments, error bars indicate SDs of technical replicates, and lines indicate model predictions. Error bars in (E) and (F) did not exceed the size of the symbols. For comparison, gray lines in (A) and (B) are model predictions for nonacclimated cells that either (A) grow at low pCO2 but with carbon uptake kinetics acclimated to high pCO2 or (B) grow at high pCO2 but with carbon uptake kinetics acclimated low pCO2. Steady-state characteristics of the experiments are summarized in table S1, and parameter values of the model are listed in tables S4 and S5.

Implementing the CO2 and bicarbonate concentrations observed at steady state (Fig. 4) into the measured carbon uptake kinetics (Fig. 2) shows that, since the dissolved CO2 concentration was depleted, the net CO2 uptake rate was negative in the experiments at low pCO2. Hence, carbon fixation at low pCO2 relied exclusively (100%) on bicarbonate uptake. Carbon fixation in the high pCO2 experiments relied for ~50% on CO2 uptake and ~50% on bicarbonate uptake.

The model predictions captured the time courses and steady states of population density, pH, and inorganic carbon chemistry in the chemostats quite well, both for the experiments at low and at high pCO2 (Fig. 4). Similar results were obtained for the other strain, Microcystis PCC 7941 (fig. S2). These results provide proof of principle that, at least under controlled laboratory conditions, measurements of the phenotypic plasticity of carbon fixation rates can be used to quantitatively predict the growth of cyanobacteria at different pCO2 levels.

The model can be used to quantify how the observed phenotypic plasticity affected cyanobacterial growth. For the experiments at low pCO2, model simulations predicted a 14.7% higher population density if the carbon uptake kinetics were acclimated to low pCO2 than if they were acclimated to high pCO2 (compare green and gray lines in Fig. 4A). Conversely, for the experiments at high pCO2, model simulations predicted a 17.3% higher population density if the carbon uptake kinetics were acclimated to high pCO2 than if they were acclimated to low pCO2 (Fig. 4B). Hence, phenotypic plasticity of the carbon uptake kinetics enhanced the population densities of Microcystis.

Extrapolation to lakes

To estimate how phenotypic plasticity will affect the response of Microcystis blooms in lakes to rising atmospheric pCO2, we up-scaled the model from laboratory chemostats to eutrophic lakes. For this purpose, we used the measured carbon uptake kinetics of Microcystis, but adjusted system parameters such as mixing depth, light intensity, and dilution rate to a lake context (section S3 and table S6). We compared model predictions for one plastic and two fixed phenotypes of Microcystis. The “plastic phenotype” displayed the phenotypic plasticity of Microcystis PCC 7806, the “low pCO2 phenotype” maintained the uptake kinetics measured in the low pCO2 chemostat, and the “high pCO2 phenotype” maintained the uptake kinetics measured at high pCO2.

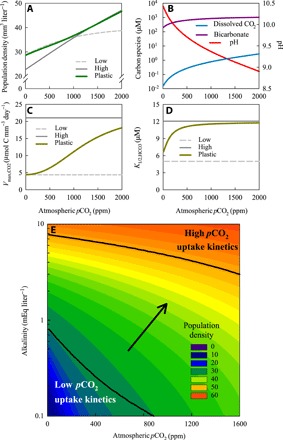

The model predicts that rising atmospheric pCO2 will increase cyanobacterial population densities, dissolved CO2, and bicarbonate concentrations and will diminish the development of a very high pH during Microcystis blooms (Fig. 5, A and B). Furthermore, the model shows that the plastic phenotype will adjust its carbon uptake kinetics to the prevailing atmospheric pCO2 and to lake alkalinity (Fig. 5, C to E). More specifically, the plastic phenotype will display carbon uptake kinetics resembling the low pCO2 phenotype in low-alkaline lakes and at low atmospheric pCO2, whereas it will display carbon uptake kinetics resembling the high pCO2 phenotype in high-alkaline lakes and at high atmospheric pCO2. In this way, the plastic phenotype is able to maximize its bloom size across the entire pCO2 gradient, with population densities matching those of the low pCO2 phenotype at low pCO2 and those of the high pCO2 phenotype at high pCO2 (Fig. 5A). As a consequence, rising atmospheric pCO2 is predicted to intensify Microcystis blooms across a wide range of lakes (Fig. 5E).

Fig. 5. Microcystis blooms predicted for lakes with different atmospheric pCO2 and alkalinity.

(A to D) Model predictions of (A) cyanobacterial population density, (B) dissolved CO2 concentration, bicarbonate, and pH, (C) maximum net CO2 uptake rate, and (D) half-saturation constant for bicarbonate uptake in Microcystis blooms of eutrophic lakes at different atmospheric pCO2 and an alkalinity of 1 mEq liter−1. Predictions were made for three phenotypes: a plastic phenotype (green line), a low pCO2 phenotype (dashed gray line), and a high pCO2 phenotype (solid gray line). (B) Predictions only for the plastic phenotype. (E) Contour plot of the population density of the plastic phenotype, predicted for eutrophic lakes with different atmospheric pCO2 and alkalinity. Black lines indicate the parameter regions at which the carbon uptake kinetics of the plastic phenotype have almost fully adjusted (≥90%) to either low pCO2 or high pCO2. The arrow indicates the transition zone where the plastic phenotype shifts from low pCO2 to high pCO2 uptake kinetics. All graphs show model predictions for cyanobacterial blooms at steady state. Species and lake parameters are provided in tables S5 and S6.

DISCUSSION

Our results show a 1.8- to 5-fold increase of the maximum CO2 uptake rate of Microcystis at elevated pCO2, which greatly exceeds plasticity of the CO2 uptake rates reported for other freshwater cyanobacteria and green algae (Table 1) and a wide variety of marine phytoplankton species (31). This high flexibility in CO2 uptake rates is most likely an adaptation to the major changes in CO2 availability that can be encountered during dense cyanobacterial blooms. Dissolved CO2 concentrations can change from air-equilibrated or even CO2-supersaturated concentrations at the onset of phytoplankton blooms to complete depletion of the available CO2 in fully developed phytoplankton blooms (11, 14, 32). CO2 depletion is accompanied by an increase in pH, which shifts the inorganic carbon chemistry toward bicarbonate. Sustained high carbon fixation rates by very dense cyanobacterial blooms may even decrease the bicarbonate concentration and increase pH to >10 (14, 20), shifting the balance from bicarbonate to carbonate as the dominant inorganic carbon species (as in Fig. 4C).

Table 1. Comparison of the carbon uptake kinetics of freshwater cyanobacteria and green algae measured by MIMS using the chemical disequilibrium assay (29, 30).

Units for K1/2 and Vmax are μM and μmol C (mg chl a)−1 hour−1, respectively.

| Species | Net CO2 uptake | Bicarbonate uptake | References | ||||||

| K½,CO2 | Vmax,CO2,net | K½,HCO3 | Vmax,HCO3 | ||||||

| Low | High | Low | High | Low | High | Low | High | ||

| pCO2 | pCO2 | pCO2 | pCO2 | pCO2 | pCO2 | pCO2 | pCO2 | ||

| Cyanobacteria | |||||||||

|

Microcystis aeruginosa PCC 7806 |

0.4 | 1.6 | 23 | 118 | 5 | 12 | 112 | 103 | This study |

|

Microcystis aeruginosa PCC 7941 |

0.6 | 0.9 | 73 | 134 | 8 | 9 | 92 | 55 | This study |

|

Synechococcus PCC 7942 |

0.4 | 5.6 | 165 | 110 | 15 | 270 | 224 | 126 | 23 |

|

Synechococcus PCC 7942 |

0.5 | 3.6 | 103 | 116 | 9 | 248 | 230 | 206 | 24 |

|

Synechocystis PCC 6803 |

1 | 3.5 | 145 | 173 | 4.8 | 86 | 281 | 218 | 22 |

| Green algae | |||||||||

|

Chlamydomonas noctigama |

3.1 | 8.1 | 37 | 39 | 75 | 379 | 41 | 37 | 49 |

|

Chlamydomonas reinhardtii |

2 | 15 | 46 | 36 | 26 | 104 | 38 | 60 | 50 |

|

Chlamydomonas reinhardtii |

0.9 | 8.3 | 113 | 82 | 78 | 316 | 92 | 75 | 51 |

|

Scenedesmus obliquus |

0.3 | 4.5 | 107 | 105 | 13 | 55 | 34 | 35 | 50 |

| Tetraedron minimum | 2.1 | 9.4 | 11 | 7 | 279 | 841 | 60 | 53 | 49 |

In our chemostat experiments, physiological acclimation occurred within a few weeks, on a similar time scale as the changes in inorganic carbon chemistry induced by the growing cyanobacterial populations. These results imply that the carbon uptake kinetics of cyanobacteria may change drastically during bloom development, from cells with high maximum CO2 uptake rates but low bicarbonate uptake efficiency when dissolved CO2 concentrations are still high at the onset of a cyanobacterial bloom, to cells with low maximum CO2 uptake rates but high bicarbonate uptake efficiency at the peak of the bloom when dissolved CO2 concentrations have been depleted.

The high maximum CO2 uptake rate at elevated pCO2 is offset by down-regulation of the bicarbonate uptake efficiency. Previous results (33) have shown that the high-affinity bicarbonate uptake system BCT1 of Microcystis strains is strongly down-regulated at elevated pCO2, which is a sensible response in view of the energetic costs of this adenosine triphosphate (ATP)–dependent uptake system and likely explains the low bicarbonate uptake efficiency at elevated pCO2 in our experiments. The maximum bicarbonate uptake rates of the two Microcystis strains in our study responded differently to elevated pCO2, which may be related to the different composition of their bicarbonate uptake systems. Cyanobacteria in which maximum bicarbonate uptake rates were reduced at elevated pCO2 [Microcystis PCC 7941 (19), Synechocystis PCC 6803 (22), and Synechococcus PCC 7942 (23, 24)] all contain the low-flux bicarbonate transporter SbtA, whereas cyanobacteria in which maximum bicarbonate uptake rates did not respond to changes in pCO2 [Microcystis PCC 7806 (19) and Trichodesmium erythraeum IMS101 (25)] all contain the high-flux bicarbonate transporter BicA but lack SbtA. Since carbon uptake kinetics have thus far been investigated for only a few cyanobacteria, these associations should be interpreted with some caution. However, down-regulation of the bicarbonate uptake efficiency by a higher half-saturation constant and/or lower maximum bicarbonate uptake rate has also been reported for green algae (Table 1) and diatoms (34, 35) and, hence, seems a common response to elevated pCO2.

Phenotypic plasticity complicates assessments of how natural communities will respond to climate change (1–4), because species responses obtained for one set of environmental conditions may deviate from those obtained for other conditions. Our study illustrates that phenotypic plasticity can be built successfully into models. The model predicts an increase in the maximum CO2 uptake rate and decrease in the bicarbonate uptake efficiency at elevated pCO2, in agreement with our experimental results (Figs. 4 and 5). Furthermore, the model reveals the adaptive significance of this phenotypic plasticity, as physiological acclimation to the prevailing pCO2 conditions enhanced the size of the Microcystis population [compare the gray and green lines in Figs. 4 (A and B) and 5A]. Enhanced growth obtained through physiological acclimation may provide a competitive advantage, which likely explains why, in recent competition experiments, Microcystis became a strong competitor in comparison to green algae at elevated pCO2 (36). In total, these results provide strong evidence that the high phenotypic plasticity of the carbon uptake kinetics of Microcystis will stimulate the development of Microcystis blooms at elevated pCO2.

In addition to phenotypic plasticity, evolutionary changes are also likely to affect the carbon uptake kinetics of future cyanobacterial blooms. Shifts in genotype composition have been found in selection experiments with multiple strains of Microcystis (12). Furthermore, evolutionary changes in CO2 uptake rates and growth kinetics have been observed in long-term phytoplankton studies exposed to elevated CO2 for hundreds to thousands of generations (37, 38). The short time span of our single-strain experiments did not provide much time for de novo mutations and subsequent selection, however. Therefore, the observed changes in our study presumably did not involve evolutionary changes in the carbon uptake kinetics but indeed derived from a high phenotypic plasticity of these traits.

While our study focused on the carbon uptake kinetics of one of the most notorious bloom-forming cyanobacteria, other relevant processes known to affect cyanobacterial blooms were left out of the equations. For example, in addition to rising atmospheric pCO2, cyanobacterial blooms will also be affected by global warming (5, 6, 13). Higher temperatures will enhance the growth rate of Microcystis but reduce the solubility of CO2, both in nonlinear ways. How this will play out is difficult to predict without dedicated models. Other important processes affecting bloom development include nutrient limitation, lake stratification, and interactions with viruses and other organisms in the aquatic food web (8). Hence, our model does not attempt to describe the full complexity of the natural world. However, our model and its experimental validation do provide an important first step for the implementation of phenotypic plasticity in ecosystem models that do take these other processes into account.

In conclusion, our results demonstrate that incorporation of the phenotypic plasticity of traits improves predictions of species responses to climate change. More specifically, we found that the high phenotypic plasticity of its CO2 uptake rate provides the bloom-forming cyanobacterium Microcystis with an exceptionally strong capacity to respond to rising pCO2 levels in comparison to other phytoplankton species. Microcystis blooms already cause major water quality problems in Lake Erie (USA) (39), Lake Taihu (China) (40), Lake Victoria (Africa) (41), and many other eutrophic and hypertrophic lakes worldwide. Our findings warn that rising atmospheric pCO2 will further intensify surface blooms of Microcystis in the coming decades.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Species and culture conditions

We studied the toxic (microcystin-producing) cyanobacteria Microcystis aeruginosa PCC 7806 and PCC 7941. Both Microcystis strains contain the two known CO2 uptake systems (NDH-13 and NDH-14). In addition, Microcystis PCC 7941 contains all three known bicarbonate uptake systems (BCT1, SbtA, and BicA), whereas Microcystis PCC 7806 has only two of them (BCT1 and BicA) (19).

The Microcystis strains were cultured as unialgal but nonaxenic strains, in CO2-controlled chemostats specifically designed to study the population dynamics of phytoplankton species (11, 12, 42) (Fig. 1A). The chemostats allowed full control of light intensity, temperature, nutrient input, and pCO2 of the aeration gas. Each chemostat consisted of a flat culture vessel with an optimal path length (mixing depth) of zmax = 5 cm and a working volume of ~1.7 liters. The vessel was illuminated from one side to create a unidirectional light gradient, using a constant incident light intensity of 40 μmol photons m−2 s−1 provided by white fluorescent tubes (Philips PL-L 24W/840/4P, Philips Lighting, Eindhoven, The Netherlands). The temperature was maintained at 25°± 1°C with a stainless steel cooling finger inside each chemostat and connected to a Colora thermocryostat. To avoid nutrient limitation, we provided a nutrient-rich mineral medium [modified BG-11 medium, (43)], with 8 mM NaNO3 and 175 μM K2HPO4.3H2O but without addition of Na2CO3 or NaHCO3, at a dilution rate of 0.2 day−1.

The chemostats were aerated with pressurized air containing either 100 ppm pCO2 (“low pCO2”) or 1000 ppm pCO2 (“high pCO2”) at a gas flow rate of 30 liters hour−1. At these settings, Microcystis growth is mainly limited by inorganic carbon at low pCO2 and by light at high pCO2 (table S1; see also 11, 36). The pCO2 in the gas flow was checked regularly using an Environmental Gas Monitor (EGM-4; PP Systems, Amesbury, MA, USA). The chemostats were sampled every 2 to 3 days to measure population densities, inorganic carbon, nutrients, and light. The chemostats were considered to be in steady state when the coefficient of variation of the population density was less than 10% for at least four consecutive time points.

Carbon uptake kinetics

Carbon uptake kinetics of the two Microcystis strains were determined with a MIMS (HPR40, Hiden Analytical Ltd., UK) using the chemical disequilibrium assay (29, 30) after they had grown in the chemostats at either low or high pCO2 for ~40 days. At this time point, the chemostats were in steady state for ~20 days. Before each assay, fresh Microcystis cells were sampled from the steady-state chemostats and concentrated by gentle centrifugation for 5 min at 600g. Then, the supernatant was discarded and the pelleted Microcystis cells were resuspended in mineral medium without dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) and nitrate. The medium was adjusted to pH 8.0 ± 0.1 using 50 mM Hepes buffer. To ensure similar assay conditions, the resuspended Microcystis cells were diluted to an OD750 (optical density at 750 nm) of 0.3, which corresponds to a Microcystis biovolume of ~400 mm3 liter−1. The suspension was aerated with N2 gas for at least 1 hour at a temperature of 25°C to remove any residual CO2. Subsequently, we transferred the Microcystis suspension to a 10-ml MIMS cuvette. We added a final concentration of 50 μM membrane-impermeable dextran-bound sulfonamide (Synthelec AB, Lund, Sweden) to inhibit any possible extracellular carbonic anhydrase activity. The MIMS cuvette was provided with the same light intensity (40 μmol photons m−2 s−1) using the same white fluorescent tubes and was kept at the same temperature (25°C) as the chemostat experiments.

With the MIMS, we simultaneously measured O2 and CO2 fluxes during consecutive light-dark intervals (5 min each) after adding known CO2 and bicarbonate concentrations during each dark phase. Net C fixation rates and respiration rates (r) were measured as rates of O2 production in the light and O2 consumption in the dark, respectively, assuming a photosynthetic quotient of 1.0 (i.e., O2 production equals net C fixation). Net CO2 uptake rates (VCO2,net) were calculated from CO2 consumption in the light period, corrected for CO2/bicarbonate interconversion in the medium. Bicarbonate uptake rates (VHCO3) were calculated from the difference between net C fixation and net CO2 uptake rates.

The measured CO2 and bicarbonate uptake rates were fitted to Michaelis-Menten equations

| (3) |

| (4) |

where [CO2] and are the dissolved CO2 and bicarbonate concentration, Vmax,CO2,gross and Vmax,HCO3 are the maximum uptake rates of gross CO2 and bicarbonate, and K1/2,CO2 and K1/2,HCO3 are the half-saturation constants. The maximum net CO2 uptake rate was calculated as Vmax,CO2,net = Vmax,CO2,gross − r. For Microcystis PCC 7941, we extended Eq. 4 with an inhibition term to capture the asymptotic decrease of its bicarbonate uptake rate at high bicarbonate concentrations (section S1 and fig. S1, C and D).

Differences between Michaelis-Menten parameters at low pCO2 versus high pCO2 were tested for significance using the independent samples t test, corrected for unequal variances when necessary and for multiple hypothesis testing using the false discovery rate (44).

Sampling and analysis

In each sample, the population density of Microcystis (expressed by the biovolume of the population) was measured in triplicate with a CASY TTC automated cell counter with a 60-μm capillary (OLS OMNI Life Science, Bremen, Germany). Light intensity transmitted through the chemostat (Iout) was measured at the back surface of the chemostat vessel with a LI-COR LI-250 quantum photometer (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE, USA). pH was measured with a SCHOTT pH meter (SCHOTT AG, Mainz, Germany) immediately after sampling. DIC was measured as CO2 after addition of 25% phosphoric acid using a Model 700 TOC Analyzer (OI Corp., College Station, TX, USA). From DIC and pH, we calculated CO2(aq), bicarbonate, and carbonate concentrations, based on the dissociation constants of inorganic carbon corrected for temperature and salinity (45). Nutrient uptake by cyanobacteria affects alkalinity (11, 46). Our model therefore required measurement of cellular nutrients, which were determined by gently washing filtered Microcystis cells twice with a nutrient-free 15 mM NaCl solution. The washed filters were stored at −20°C until further analysis. For cellular C, N, and S contents, one set of preweighted filters were freeze dried, wrapped in tin foil discs (30 mm, Sercon Ltd., Crewe, UK), and analyzed using a Vario EL Elemental Analyzer (Elementar Analysensysteme GmbH, Hanau, Germany). For the cellular P content, another set of the same filters were put into glass tubes that contained 10 ml of Milli-Q water, 0.2 ml of 5.5 M H2SO4, and 1.5 ml of 8% (NH4)2S2O8 solvent, and the sealed tubes were autoclaved for 1 hour at 121°C, to convert all organic P to orthophosphate. Orthophosphate concentrations were measured with a Skalar SA 400 autoanalyzer (Skalar Analytical B.V., Breda, The Netherlands). Samples for chlorophyll a analysis were filtered on 25-mm glass fiber filters (GF/C, 1.2-μm pore size, Whatman GmbH, Dassel, Germany) and freeze dried for at least 2 hours. Chlorophyll a was extracted with N,N-dimethylformamide and measured spectrophotometrically (47).

Mathematical model

We developed a dynamical model to describe the carbon uptake kinetics and population dynamics of cyanobacteria as a function of pCO2 and light availability. The model combines previous theoretical and experimental work on phytoplankton growth under light-limited (42, 48) and carbon-limited conditions (11, 36). In short, the model assumes eutrophic conditions, in which all nutrients are in ample supply and, hence, do not limit phytoplankton growth. The CO2 and bicarbonate uptake kinetics and phenotypic plasticity of the uptake parameters are described by Eqs. 1 to 4. The carbon uptake rates and light availability, in turn, determine the growth rate of the cyanobacterial population. Furthermore, uptake of CO2, bicarbonate, and nutrients induces changes in pH and alkalinity. These changes in pH and alkalinity affect the speciation of inorganic carbon, which, in turn, feeds back on carbon uptake and growth of the cyanobacteria. The expanding cyanobacterial population also increases the turbidity of the water column, thereby diminishing light available for further photosynthesis and growth. The model is described in full detail in section S2.

The model parameters were measured experimentally and include system parameters (e.g., incident light intensity, pCO2 level in the gas flow, and dilution rate of the chemostats; table S4) and species parameters (e.g., maximum uptake rates and half-saturation constants; table S5). In particular, the carbon uptake kinetics and respiration rates measured by MIMS (Fig. 2 and tables S2 and S3) served as input to predict the carbon uptake and concomitant changes in inorganic carbon chemistry at both low and high pCO2. The model and its parameterization are described in detail in section S2.

For the lake model (section S3), we choose parameter values representative for the summer situation in eutrophic lakes dominated by dense Microcystis blooms. The species parameters are identical to those of Microcystis PCC 7806 (table S5), where we distinguished between a plastic phenotype, low pCO2 phenotype, and high pCO2 phenotype as described in Results. The system parameters for the lake model are summarized in table S6.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank R. van Hall for assistance with the TOC Analyzer and Elemental Analyzer. Funding: This research is supported by the Division of Earth and Life Sciences (ALW) of the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO). X.J. is also supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2017YFC0506001) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (41676084). Author contributions: X.J., J.M.H.V., and J.H. designed the study. X.J. performed the laboratory experiments and analyzed the chemostat samples, with J.M.H.V. providing scientific support. X.J., D.B.V.d.W., and B.R. developed the MIMS bioassay. X.J. performed the MIMS measurements, and X.J., J.M.H.V., D.B.V.d.W., and B.R. analyzed the MIMS data. J.M.H.V. and J.H. developed the model, and J.M.H.V. ran the model predictions. X.J., J.M.H.V., and J.H. wrote the manuscript, and all authors commented on the final version. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/6/8/eaax2926/DC1

Section S1. Description of bicarbonate uptake of Microcystis PCC 7941

Section S2. Description of the mathematical model

Section S3. Extrapolation of the model to lakes

Fig. S1. Carbon uptake kinetics of Microcystis PCC 7941 acclimated to either low or high pCO2.

Fig. S2. Population density, inorganic carbon chemistry, and pH in chemostat experiments with Microcystis PCC 7941 at low and at high pCO2.

Table S1. Steady-state characteristics of the chemostat experiments with Microcystis PCC 7806 and Microcystis PCC 7941.

Table S2. Kinetic parameters estimated from the carbon uptake experiments with Microcystis PCC 7806 and Microcystis PCC 7941.

Table S3. Tests of significant differences between kinetic parameters estimated at low versus high pCO2.

Table S4. System parameters applied in the chemostat experiments.

Table S5. Species parameters measured experimentally.

Table S6. System parameters applied in the lake model.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Charmantier A., McCleery R. H., Cole L. R., Perrins C., Kruuk L. E., Sheldon B. C., Adaptive phenotypic plasticity in response to climate change in a wild bird population. Science 320, 800–803 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chevin L.-M., Collins S., Lefèvre F., Phenotypic plasticity and evolutionary demographic responses to climate change: taking theory out to the field. Funct. Ecol. 27, 967–979 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vargas C. A., Lagos N. A., Lardies M. A., Duarte C., Manríquez P. H., Aguilera V. M., Broitman B., Widdicombe S., Dupont S., Species-specific responses to ocean acidification should account for local adaptation and adaptive plasticity. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 1, 0084 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kremer C. T., Fey S. B., Arellano A. A., Vasseur D. A., Gradual plasticity alters population dynamics in variable environments: Thermal acclimation in the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhartdii. Proc. Biol. Sci. 285, 20171942 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paerl H. W., Huisman J., Blooms like it hot. Science 320, 57–58 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Neil J. M., Davis T. W., Burford M. A., Gobler C. J., The rise of harmful cyanobacteria blooms: potential role of eutrophication and climate change. Harmful Algae 14, 313–334 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taranu Z. E., Gregory-Eaves I., Leavitt P. R., Bunting L., Buchaca T., Catalan J., Domaizon I., Guilizzoni P., Lami A., McGowan S., Moorhouse H., Morabito G., Pick F. R., Stevenson M. A., Thompson P. L., Vinebrooke R. D., 2015. Acceleration of cyanobacterial dominance in north temperate-subarctic lakes during the Anthropocene. Ecol. Lett. 18, 375–384 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huisman J., Codd G. A., Paerl H. W., Ibelings B. W., Verspagen J. M. H., Visser P. M., Cyanobacterial blooms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 16, 471–483 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carmichael W. W., Health effects of toxin-producing cyanobacteria: “The CyanoHABs”. Hum. Ecol. Risk. Assess. 7, 1393–1407 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 10.J. Meriluoto, L. Spoof, G. A. Codd, Handbook of Cyanobacterial Monitoring and Cyanotoxin Analysis (John Wiley & Sons Inc., 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Verspagen J. M. H., Van de Waal D. B., Finke J. F., Visser P. M., van Donk E., Huisman J., Rising CO2 levels will intensify phytoplankton blooms in eutrophic and hypertrophic lakes. PLOS ONE 9, e104325 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sandrini G., Ji X., Verspagen J. M. H., Tann R. P., Slot P. C., Luimstra V. M., Schuurmans J. M., Matthijs H. C. P., Huisman J., Rapid adaptation of harmful cyanobacteria to rising CO2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 9315–9320 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Visser P. M., Verspagen J. M. H., Sandrini G., Stal L. J., Matthijs H. C. P., Davis T. W., Paerl H. W., Huisman J., How rising CO2 and global warming may stimulate harmful cyanobacterial blooms. Harmful Algae 54, 145–159 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ibelings B. W., Maberly S. C., Photoinhibition and the availability of inorganic carbon restrict photosynthesis by surface blooms of cyanobacteria. Limnol. Oceanogr. 43, 408–419 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wanninkhof R., Knox M., Chemical enhancement of CO2 exchange in natural waters. Limnol. Oceanogr. 41, 689–697 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Badger M. R., Price G. D., CO2 concentrating mechanisms in cyanobacteria: Molecular components, their diversity and evolution. J. Exp. Bot. 54, 609–622 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burnap R. L., Hagemann M., Kaplan A., Regulation of CO2 concentrating mechanism in cyanobacteria. Life 5, 348–371 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Price G. D., Badger M. R., Woodger F. J., Long B. M., Advances in understanding the cyanobacterial CO2-concentrating-mechanism (CCM): functional components, Ci transporters, diversity, genetic regulation and prospects for engineering into plants. J. Exp. Bot. 59, 1441–1461 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sandrini G., Matthijs H. C. P., Verspagen J. M. H., Muyzer G., Huisman J., Genetic diversity of inorganic carbon uptake systems causes variation in CO2 response of the cyanobacterium Microcystis. ISME J. 8, 589–600 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sandrini G., Tann R. P., Schuurmans J. M., van Beusekom S. A. M., Matthijs H. C. P., Huisman J., Diel variation in gene expression of the CO2-concentrating mechanism during a harmful cyanobacterial bloom. Front. Microbiol. 7, 551 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eisenhut M., von Wobeser E. A., Jonas L., Schubert H., Ibelings B. W., Bauwe H., Matthijs H. C. P., Hagemann M., Long-term response toward inorganic carbon limitation in wild type and glycolate turnover mutants of the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803. Plant Physiol. 144, 1946–1959 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Benschop J. J., Badger M. R., Price G. D., Characterisation of CO2 and HCO3− uptake in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC6803. Photosynth. Res. 77, 117–126 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu J. W., Price G. D., Badger M. R., A mutant isolated from the cyanobacterium Synechococcus PCC7942 is unable to adapt to low inorganic carbon conditions. Plant Physiol. 104, 605–611 (1994). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sültemeyer D., Klughammer B., Badger M. R., Price G. D., Fast induction of high-affinity HCO3− transport in cyanobacteria. Plant Physiol. 116, 183–192 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kranz S. A., Sültemeyer D., Richter K. U., Rost B., Carbon acquisition by Trichodesmium: The effect of pCO2 and diurnal changes. Limnol. Oceanogr. 54, 548–559 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hopkinson B. M., Young J. N., Tansik A. L., Binder B. J., The minimal CO2 concentrating mechanism of Prochlorococcus spp. MED4 is effective and efficient. Plant Physiol. 166, 2205–2217 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harke M. J., Steffen M. M., Gobler C. J., Otten T. G., Wilhelm S. W., Wood S. A., Paerl H. W., A review of the global ecology, genomics, and biogeography of the toxic cyanobacterium, Microcystis spp. Harmful Algae 54, 4–20 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sobek S., Tranvik L. J., Cole J. J., Temperature independence of carbon dioxide supersaturation in global lakes. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 19, GB2003 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Badger M. R., Palmqvist K., Yu J.-W., Measurement of CO2 and HCO3− fluxes in cyanobacteria and microalgae during steady-state photosynthesis. Physiol. Plant. 90, 529–536 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rost B., Kranz S. A., Richter K. U., Tortell P. D., Isotope disequilibrium and mass spectrometric studies of inorganic carbon acquisition by phytoplankton. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods 5, 328–337 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 31.van de Waal D. B., Brandenburg K. M., Keuskamp J., Trimborn S., Rokitta S., Kranz S. A., Rost B., Highest plasticity of carbon concentrating mechanisms in earliest evolved phytoplankton. Limnol. Oceanogr. Lett. 4, 37–43 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maberly S. C., Diel, episodic and seasonal changes in pH and concentrations of inorganic carbon in a productive lake. Freshw. Biol. 35, 579–598 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sandrini G., Cunsolo S., Schuurmans J. M., Matthijs H. C. P., Huisman J., Changes in gene expression, cell physiology and toxicity of the harmful cyanobacterium Microcystis aeruginosa at elevated CO2. Front. Microbiol. 6, 401 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rost B., Riebesell U., Burkhardt S., Sültemeyer D., Carbon acquisition of bloom-forming marine phytoplankton. Limnol. Oceanogr. 48, 55–67 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Trimborn S., Wolf-Gladrow D., Richter K.-U., Rost B., The effect of pCO2 on carbon acquisition and intracellular assimilation in four marine diatoms. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 376, 26–36 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ji X., Verspagen J. M. H., Stomp M., Huisman J., Competition between cyanobacteria and green algae at low versus elevated CO2: Who will win, and why? J. Exp. Bot. 68, 3815–3828 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Collins S., Bell G., Phenotypic consequences of 1000 generations of selection at elevated CO2 in a green alga. Nature 431, 566–569 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hutchins D. A., Walworth N. G., Webb E. A., Saito M. A., Moran D., McIlvin M. R., Gale J., Fu F.-X., Irreversibly increased nitrogen fixation in Trichodesmium experimentally adapted to elevated carbon dioxide. Nat. Commun. 6, 8155 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bullerjahn G. S., McKay R. M., Davis T. W., Baker D. B., Boyer G. L., D’Anglada L. V., Doucette G. J., Ho J. C., Irwin E. G., Kling C. L., Kudela R. M., Kurmayer R., Michalak A. M., Ortiz J. D., Otten T. G., Paerl H. W., Qin B., Sohngen B. L., Stumpf R. P., Visser P. M., Wilhelm S. W., Global solutions to regional problems: collecting global expertise to address the problem of harmful cyanobacterial blooms, a Lake Erie case study. Harmful Algae 54, 223–238 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guo L., Doing battle with the green monster of Taihu Lake. Science 317, 1166–1166 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sitoki L., Kurmayer R., Rott E., Spatial variation of phytoplankton composition, biovolume, and resulting microcystin concentrations in the Nyanza Gulf (Lake Victoria, Kenya). Hydrobiologia 691, 109–122 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huisman J., Jonker R. R., Zonneveld C., Weissing F. J., Competition for light between phytoplankton species: Experimental tests of mechanistic theory. Ecology 80, 211–222 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rippka R., Deruelles J., Waterbury J. B., Herdman M., Stanier R. Y., Generic assignments, strain histories and properties of pure cultures of cyanobacteria. Microbiology 111, 1–61 (1979). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Benjamini Y., Yekutieli D., The control of the false discovery rate in multiple testing under dependency. Ann. Stat. 29, 1165–1188 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 45.W. Stumm, J. J. Morgan, Aquatic Chemistry: Chemical Equilibria and Rates in Natural Waters (Wiley and Sons, 1996). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wolf-Gladrow D. A., Zeebe R. E., Klaas C., Kortzinger A., Dickson A. G., Total alkalinity: the explicit conservative expression and its application to biogeochemical processes. Mar. Chem. 106, 287–300 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Porra R. J., Thompson W. A., Kriedemann P. E., Determination of accurate extinction coefficients and simultaneous equations for assaying chlorophylls a and b extracted with four different solvents: Verification of the concentration of chlorophyll standards by atomic absorption spectroscopy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 975, 384–394 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huisman J., Weissing F. J., Light-limited growth and competition for light in well-mixed aquatic environments: an elementary model. Ecology 75, 507–520 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- 49.van Hunnik E., Amoroso G., Sültemeyer D., Uptake of CO2 and bicarbonate by intact cells and chloroplasts of Tetraedron minimum and Chlamydomonas noctigama. Planta 215, 763–769 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Palmqvist K., Yu J.-W., Badger M. R., Carbonic anhydrase activity and inorganic carbon fluxes in low- and high-Ci cells of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii and Scenedesmus obliquus. Physiol. Plant. 90, 537–547 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Amoroso G., Sültemeyer D., Thyssen C., Fock H. P., Uptake of HCO3− and CO2 in cells and chloroplasts from the microalgae Chlamydomonas reinhardtii and Dunaliella tertiolecta. Plant Physiol. 116, 193–201 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Siegenthaler U., Sarmiento J. L., Atmospheric carbon dioxide and the ocean. Nature 365, 119–125 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cole J. J., Bade D. L., Bastviken D., Pace M. L., van de Bogert M., Multiple approaches to estimating air-water gas exchange in small lakes. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods 8, 285–293 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Portielje R., Lijklema L., Carbon dioxide fluxes across the air-water interface and its impact on carbon availability in aquatic systems. Limnol. Oceanogr. 40, 690–699 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Frey H. C., Patil S. R., Identification and review of sensitivity analysis methods. Risk Anal. 22, 553–578 (2002). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bade D. L., Cole J. J., Impact of chemically enhanced diffusion on dissolved inorganic carbon stable isotopes in a fertilized lake. J. Geophys. Res. 111, C01014 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jöhnk K. D., Huisman J., Sharples J., Sommeijer B., Visser P. M., Stroom J. M., Summer heatwaves promote blooms of harmful cyanobacteria. Glob. Chang. Biol. 14, 495–512 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xu H., Paerl H. W., Qin B., Zhu G., Gao G., Nitrogen and phosphorus inputs control phytoplankton growth in eutrophic Lake Taihu, China. Limnol. Oceanogr. 55, 420–432 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 59.Crusius J., Wanninkhof R., Gas transfer velocities measured at low wind speed over a lake. Limnol. Oceanogr. 48, 1010–1017 (2003). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/6/8/eaax2926/DC1

Section S1. Description of bicarbonate uptake of Microcystis PCC 7941

Section S2. Description of the mathematical model

Section S3. Extrapolation of the model to lakes

Fig. S1. Carbon uptake kinetics of Microcystis PCC 7941 acclimated to either low or high pCO2.

Fig. S2. Population density, inorganic carbon chemistry, and pH in chemostat experiments with Microcystis PCC 7941 at low and at high pCO2.

Table S1. Steady-state characteristics of the chemostat experiments with Microcystis PCC 7806 and Microcystis PCC 7941.

Table S2. Kinetic parameters estimated from the carbon uptake experiments with Microcystis PCC 7806 and Microcystis PCC 7941.

Table S3. Tests of significant differences between kinetic parameters estimated at low versus high pCO2.

Table S4. System parameters applied in the chemostat experiments.

Table S5. Species parameters measured experimentally.

Table S6. System parameters applied in the lake model.