Abstract

Crop pollination by the western honey bee Apis mellifera is vital to agriculture but threatened by alarmingly high levels of colony mortality, especially in Europe and North America. Colony loss is due, in part, to the high viral loads of Deformed wing virus (DWV), transmitted by the ectoparasitic mite Varroa destructor, especially throughout the overwintering period of a honey bee colony. Covert DWV infection is commonplace and has been causally linked to precocious foraging, which itself has been linked to colony loss. Taking advantage of four brain transcriptome studies that unexpectedly revealed evidence of covert DWV-A infection, we set out to explore whether this effect is due to DWV-A mimicking naturally occurring changes in brain gene expression that are associated with behavioral maturation. Consistent with this hypothesis, we found that brain gene expression profiles of DWV-A infected bees resembled those of foragers, even in individuals that were much younger than typical foragers. In addition, brain transcriptional regulatory network analysis revealed a positive association between DWV-A infection and transcription factors previously associated with honey bee foraging behavior. Surprisingly, single-cell RNA-Sequencing implicated glia, not neurons, in this effect; there are relatively few glial cells in the insect brain and they are rarely associated with behavioral plasticity. Covert DWV-A infection also has been linked to impaired learning, which together with precocious foraging can lead to increased occurrence of infected bees from one colony mistakenly entering another colony, especially under crowded modern apiary conditions. These findings provide new insights into the mechanisms by which DWV-A affects honey bee health and colony survival.

Subject terms: Agroecology, Agroecology, Social behaviour, Social behaviour

Introduction

Western honey bees (Apis mellifera) provide an essential pollination service for modern agriculture, with a value estimated at $15 billion per year in the United States1,2. Extensive reliance on pollination by honey bees has led to great concerns over the massive losses of managed colonies that have occurred since 20063–5. These losses are widely thought to be caused by parasites, pathogens, pesticides and poor nutrition, and the main parasite is the ectoparasitic mite Varroa destructor6–10. Varroa mites are the primary vectors of Deformed wing virus (DWV)11,12, a single-stranded, positive-sense RNA virus (family Iflaviridae) that specifically impacts arthropods13–16.

DWV is globally distributed, driving an economic and ecological crisis in honey bee populations17. DWV was first discovered in symptomatic deformed winged honey bees from Japan in the early 1980s18, and the first full genome was sequenced in 200619, hereafter referred to as type A or DWV-A20. Martin et al. showed through screening the Hawaiian honey bee population that diverse DWV variants persisted prior to the arrival of Varroa21; however, the establishment of Varroa selected for a single variant, DWV-A. DWV-A is currently the most prevalent variant in the North America22, though two other master variants have been identified: DWV-B, which is more commonly found in Europe and is also associated with colony loss22,23, and DWV-C, which is extremely rare in North America, though its effects are currently unknown20,22,24.

DWV localizes to major sensory and behavioral centers of the bee brain where it actively replicates25, and behavioral consequences of infection on associative learning and reward responsiveness have been documented26. In addition, studies have demonstrated that low doses of DWV increase mortality rates, cause workers to accelerate their behavioral maturation and initiate foraging at younger ages, and forage less than controls despite no physical symptoms, supporting previous correlative findings27,28. These behavioral studies imply a disruption of critical behavioral programs, suggesting that viral infection has multiple and strong effects on brain and behavior. Neurogenomic studies might be helpful to understand the mechanistic basis of these effects, but no study has yet examined DWV effects on brain gene expression in adult worker honey bees.

Honey bees can be infected naturally with high DWV titers without displaying obvious, physical symptoms27,28. To explore mechanistic implications, we took advantage of four brain transcriptome studies that unexpectedly revealed evidence of covert DWV-A infection, two published29,30 and two new RNA-Sequencing (RNA-Seq) datasets (Table 1). In these datasets over 99% of 335 individual brain samples contained at least one sequenced read aligned to the DWV-A viral genome, rather than the honey bee genome19, and more than one third of the samples contained over 1% of sequenced reads aligned to DWV-A (Fig. 1). All bees collected for these studies were negative for any visible symptoms of DWV19,31 and no overt signs of impairment were observed in specific behavioral paradigms. We performed gene expression and transcriptional regulatory network analyses to compare these four RNA-Seq datasets and explore how DWV-A affects brain gene expression, as a step towards implicating specific molecular pathways associated with the global decline in bee health. The existence of multiple transcriptome datasets afforded the opportunity to test for consistent, robust transcriptome signatures of viral infection across the four otherwise unrelated studies and to determine whether DWV-A targets pathways similar to other bee viruses32.

Table 1.

Overview of the honey bee brain transcriptome studies included in this meta-analysis.

| Study | Sample size/caste | Age | Brain region | Queen | GEO Accession | Year of sample collection | Publication | Focal behavior |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 39/workers | 2–3 weeks | Mushroom bodies | Naturally mated | GSE130701 | 2012 | McNeill et al. 2015 | Reward responsiveness |

| 2 | 180/workers | 7 days | Mushroom bodies | Single-drone inseminated | GSE85878 | 2014 | Shpigler et al. 2017 | Aggression |

| 3 | 20/drones | 2–3 weeks | Mushroom bodies | Naturally mated | GSE130702 | 2012 | Unpublished | Reward responsiveness |

| 4 | 96/workers | 6 days | Whole brain | Single-drone inseminated | GSE130700 | 2014 | Unpublished | Caregiving/affiliation |

We analyzed two published (Studies 1 and 2) and two new (Studies 3 and 4) brain transcriptome studies which were independently performed in apiaries in Urbana, IL from 2012 to 2014.

Figure 1.

Percentage of mRNA sequencing reads found in honey bee whole-brain and mushroom bodies RNA extractions that aligned to the DWV-A viral genome (accession number AJ489744) instead of the honey bee genome (version HAv3.1). Studies are organized by average % mRNA reads aligning to DWV genome, from smallest to largest. Studies 1–3 performed RNA-Sequencing (RNA-Seq) from the mushroom bodies of adult honey bee brains while Study 4 utilized the whole honey bee brain for RNA-Seq (see Table 1 for study details). Width of the violin plot is proportional to frequency of samples that fall in a given region on the y-axis. Boxplots show median (white half-circle or circle at densest point of violin plot), quartiles (thick black bar) and 0.05 and 0.95 quantiles (thin black lines). Sample sizes, reported above each violin plot, refer to the number of individual bees analyzed. Raw read data can be found in Figshare repository (see below).

We tested the hypothesis that DWV-A affects some of the same molecular pathways that influence behavioral maturation, as covert DWV-A infection has been shown to cause bees to forage at a younger age than normal33. Worker honey bees undergo an age-related transition from in-hive nurses to out-of-hive foragers, and this process of behavioral maturation can be accelerated or delayed depending on the needs of the colony34. The effect of DWV-A infection on behavioral maturation is of particular importance because precocious behavioral maturation has independently been associated with diminished spatial memory and colony failure33,35,36, so disoriented foragers may be more likely to spread DWV to neighboring colonies. Therefore, laying the groundwork for a mechanistic link between viral infection and accelerated behavioral maturation could provide new insights into the dynamics of this host-pathogen relationship.

Results

Common patterns of brain gene expression in DWV-A infected bees

To examine the molecular consequences of DWV-A infection in the honey bee brain, we analyzed two published29,30 and two new brain RNA-Seq datasets containing transcriptome data from both adult worker (female) and drone (male) honey bees (Table 1). We used DWV-mapped transcripts as a linear predictor of brain gene expression (Fig. 1). Using a false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05, we found the following numbers of positively and negatively DWV-A associated genes, hereafter referred to as “DWV-associated genes”: 77 positively and 0 negatively associated (Study 129); 1072 positively and 695 negatively associated (Study 230); 134 positively and 162 negatively associated (Study 3); and 137 positively and 232 negatively associated (Study 4; all gene lists in Supplementary Tables S1–S4). In Study 230, the authors excluded from post-sequencing analysis 28 samples with DWV-A infection found to be “severe” (having more than 0.5% DWV-mapped transcripts); here, we have included them. In Study 4, several behavioral and molecular perturbations were conducted but did not result in any differential gene expression between groups, which we attribute to DWV-A infection. We have included all the samples from that study and deposited all relevant treatment information with the GEO submission (GSE130700).

Calculating all possible intersections among the four datasets we found seven DWV-associated genes shared between all datasets (hypergeometric test, fold enrichment [FE] = 290.59, p < 0.01, Fig. 2a): peptidoglycan-recognition protein S2 precursor (PGRP-S2), multiple inositol polyphosphate phosphatase 1, uncharacterized LOC724126, acyl-CoA delta-11 desaturase, aldehyde dehydrogenase (aldh), chitinase-like protein Idgf4 isoform X2 (Idgf4), and apidaecin 1 (apid1). Each gene was positively associated with DWV-A infection except for uncharacterized LOC724126 in Study 3, which was negatively associated.

Figure 2.

DWV-associated brain gene expression is highly similar between studies. (a) Hundreds of DWV-associated genes were shared between at least two independent studies, with a list of seven genes associated with all four studies (inset). (b) Results of hypergeometric tests show significant overlap of DWV-associated genes across various combinations of the four studies. A gene list universe common to all four studies was used to increase stringency of analysis. Studies are ordered by increasing fold enrichment score (see Methods). All pairwise comparisons were significant at FDR < 0.0005 (raw and corrected p values in Supplementary Table S5).

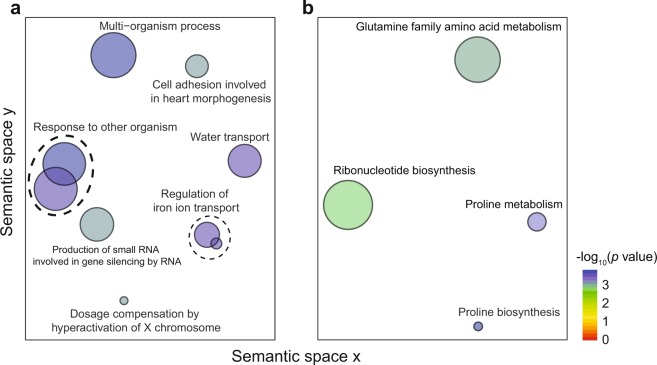

We found a significant overlap for each pairwise comparison among the four DWV-associated gene lists (hypergeometric test, FE > 2.0, FDR < 0.01 for each pairwise comparison, Fig. 2b; Supplementary Table S5). Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis performed on genes positively associated with DWV-A with GOrilla37 identified an over-representation of several GO terms associated with iron metabolism, response to virus, and other biological processes (Fig. 3a; Supplementary Table S6). We found fewer GO terms enriched in genes negatively associated with DWV-A, primarily involved with amino acid synthesis and metabolism (Fig. 3b; Supplementary Table S7). GO terms for individual datasets are in Supplementary Tables S8–S15.

Figure 3.

REVIGO plots show Gene Ontology (GO) terms enriched in (a) positively or (b) negatively associated DWV-associated gene lists. Plots are organized in semantic space in which more similar terms in the GO hierarchy are more closely positioned. Circle diameter is correlated with the inverse of the GO term’s specificity with smaller circles representing more specific terms.

DWV-associated gene expression compared to previous studies of nurse-forager gene expression

To test the hypothesis that DWV-A influences the molecular pathways underlying behavioral maturation and accelerates the nurse-to-forager transition, we compared DWV-associated gene expression in each study to published transcriptomic comparisons of nurses and foragers. None of the four studies we analyzed included comparisons of nurses and foragers, although Study 4 examined caregiving (nursing) behavior among bees. This was examined in small, age-matched groups and not as a naturally occurring behavior in the field. Also, no comparisons were made to foragers or older bees of any behavioral state and, moreover, we could not detect any effect of caregiving on gene expression profile (see above for information regarding Study 4, in which no differentially expressed genes were detected relative to experimental conditions). Studies 2 and 4 contained adult workers that were considerably younger than typical foraging age, the onset of which is at least 2–3 weeks of age (see Table 1)38,39. To obtain focal bees for these studies, honeycomb frames of capped brood were stored in an incubator and newly eclosed adults were collected every 24 hours. This method has been regularly used to form groups of bees in which the exact age is known40,41. Therefore, we suggest that behavioral maturation-related gene expression in DWV-A infected samples was specifically due to viral infection and not conflated with experimental conditions.

We used nurse- and forager-related transcriptome profiles previously validated across two published studies not analyzed here42,43. We only considered genes that were concordant across these two studies despite differences in technical and methodological details; given this stringency, we use these nurse- and forager-upregulated genes as designations of nursing and foraging behavioral states. In Studies 1, 2 and 4, which all contain worker (female) honey bees, we found that genes positively associated with DWV-A infection were significantly enriched in forager, but not nurse, transcriptome profiles (hypergeometric test, FE > 1.8, FDR < 0.05). Study 3, which contains drone (male) samples, did not show significant enrichment in nurse or forager gene lists (Fig. 4, Supplementary Table S16).

Figure 4.

Neurogenomic state of DWV-A infected bees is more similar to foragers than nurses. Genes positively associated with DWV-A infection showed significant overlap with nurse- and forager-upregulated genes validated between two independent studies42,43, which we term “high-probability” genes. Pairwise comparisons were significant (FDR < 0.05) in Study 1, 2 and 4, which sampled (female) workers but not Study 3, which sampled (male) drones. FE, raw and corrected p values are reported in Supplementary Table S16. “–” denotes a nonsignificant overlap.

Transcriptional regulatory network analysis

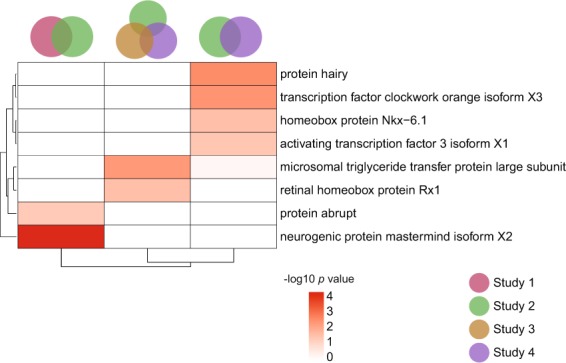

To help identify transcription factors important in regulating the transcriptional response in the honey bee brain to DWV-A infection, we reconstructed a transcriptional regulatory network (TRN) using brain gene expression to infer regulatory interactions between transcription factors (TFs) and their targets. We only used orthologs of TFs and target genes that have been experimentally validated in Drosophila melanogaster44 and generated a TRN of 248 TFs and 5716 target genes (Supplementary Table S17). We found 19 TFs with predicted target genes significantly enriched in the DWV-associated gene lists, the majority of which (13/19) showed enrichment only in Study 2 (Supplementary Table S18). Eight TFs, including protein hairy (hairy), transcription factor clockwork orange isoform X3 (cwo), and activating transcription factor 3 isoform X1 (atf3) had their predicted target genes enriched in at least two DWV-associated gene lists (Fig. 5, Supplementary Table S19). Studies 2 and 4, which contained only young (age ≤ 7 days) worker bees collected in 2014, shared the most TFs.

Figure 5.

DWV-A infection influences the brain transcriptional regulatory architecture of brain gene expression. We used ASTRIX to infer a transcriptional regulatory network associated with DWV-A infection. We found eight transcription factors (TF) with target genes enriched in at least two datasets, implicating them as important regulators of the effects of DWV-A infection on honey bee brain gene expression.

ABC and CBA assays for DWV-A subtype validation

To validate the read-mapping specificity to reliably discriminate between the master variants of DWV, we used two competitive reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assays to target different portions of the virus genome (n = 35 samples from Study 4). Using the ABC assay45, which targets the RNA dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) region in DWV, we found a significant correlation between %DWV and DWV type A (Pearson correlation; DWV-A, r = 0.59, p < 0.001, Fig. 6a). Next, we used the CBA assay [Highfield et al., in preparation] to target the DWV capsid region. Using this assay, we found a strong relationship between %DWV-A as identified through mapping and DWV-A through RT-PCR (r = 0.87, p = 1.97e-09, Fig. 6b). We did not find evidence of DWV type B or C in our honey bee samples.

Figure 6.

RT-PCR analyses uncover full-length DWV-A transcripts. (a) ABC assay, which targets the RNA dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) region in DWV-A, provided mean copy numbers of master variant DWV-A which was significantly correlated with % reads aligned to DWV-A viral genome (r = 0.59, p < 0.001). (b) CBA assay, which targets the capsid region of DWV transcripts, showed a significant correlation for DWV-A (r = 0.87, p = 1.97e-09). Pearson correlation; n = 35 whole-brain samples from Study 4. We found no evidence for DWV type B or C.

Single-cell RNA-Sequencing

To identify specific cell populations in the brain impacted by DWV-A, we used the 10x Genomics (10x) Chromium platform to perform single-cell RNA-Sequencing (scRNA-Seq) on the whole brain (WB) and mushroom bodies (MB) of two individual bees unrelated to the studies analyzed here. We chose both WB and MB because both were sampled for the datasets analyzed in this meta-analysis (Table 1) and including a focal region (MB) might help identify rarer cells types we would otherwise be unable to identify. Each library generated over 360 million reads and we recovered transcriptome data from ~1,200 cells per sample with a median of 1,167 and 1,559 genes per cell, for the WB and MB, respectively (Fig. 7a). We merged both WB and MB datasets and identified 13 cell clusters based on similarities in gene expression profiles (Supplementary Table S20).

Figure 7.

Single-cell RNA-Sequencing demonstrates significant enrichment of DWV-associated genes in a single predicted cluster of honey bee brain cells. (a) Two-dimensional visualization of single-cell RNA-Sequencing (scRNA-Seq) from one whole brain and one mushroom bodies from two healthy worker bees, independent of the bees used in the previous analyses. We used tSNE clustering to sort cells into 13 clusters based on gene expression profiles of 2,205 cells. Dashed circle outlines Cluster 11. (b) Hypergeometric overlap tests comparing positively associated DWV-associated genes and cluster-defining upregulated genes (see Methods) show that DWV-associated genes are only enriched in a single cluster, Cluster 11. All BH-corrected p values are < 0.005. “--” denotes a nonsignificant overlap. (c) The canonical neuronal marker elav is highly expressed in the vast majority clusters excluding Cluster 11, where glial markers repo and Gs2 are specifically expressed. Color scales represent log-normalized gene expression per cell.

To test the hypothesis that the neurogenomic signature of DWV-A infection is localized to a specific brain region or cell subpopulation, we performed a series of hypergeometric tests to compare genes positively associated with DWV-A infection and genes upregulated per predicted cell cluster. We only found a significant result in Cluster 11, in which each DWV-associated gene list had a significant FE score (FDR < 0.01, Fig. 7b). The neuronal marker elav was largely absent from this cluster, whereas the insect glial markers reversed polarity (repo)46 and glutamine synthetase (Gs2)47 were significantly upregulated (Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test, repo: average log fold-change = 2.39, FDR = 1.61e-130; Gs2: average log fold-change = 3.22, FDR = 6.5e-31). Neither repo nor Gs2 were upregulated in any other cluster (Fig. 7c).

Discussion

We identified common transcriptional signatures of DWV-A infection in the honey bee brain based on brain transcriptome studies of asymptomatic individuals, thus presenting the first neurogenomic analysis of the conserved molecular impact of covert yet widespread DWV-A infection. Our results, which were due to infection exclusively with DWV type A, indicate strong effects on honey bee brain gene expression, with several molecular pathways and transcription factors implicated across multiple independent studies. In addition, our meta-analysis highlights strong similarities in brain gene expression and transcriptional regulatory architecture between infected bees and natural foragers, thus filling an important gap in our understanding of how DWV-A may impact colony demographics and survival. DWV-A appears to accelerate honey bee behavioral maturation and activate molecular pathways in the brain associated with the transition from nurse to forager.

Some of the genes identified here have been implicated in viral infection in other studies of honey bees. The antimicrobial peptide-encoding apid1 and the pathogen recognition receptor PGRP-S2, which were positively associated with DWV-A infection in all four studies, have also been shown to be casually linked to dsRNA treatment or Sindbis virus infection in the thorax and abdomen of infected honey bees48 and therefore may be activated following generalized inflammation in multiple tissues. Moreover, a meta-analysis of 19 transcriptome datasets of experimentally infected worker honey bees, which did not include an analysis of DWV in the adult brain, found that PGRPs were either consistently differentially expressed or were predicted to regulate many genes across datasets32. PGRP-S2 also was found to be upregulated in bees taken from colonies diagnosed with CCD49. GO enrichment analysis revealed that genes positively associated with DWV were enriched for gene silencing by RNA, which plays a role in insect antiviral defense50 and may therefore signify a protective mechanism against DWV infection.

Other genes identified here have been implicated in viral infection or inflammation across a broad range of conditions among phylogenetically diverse species, including humans. This is remarkable, given that insects lack lymphocytes, immunoglobulins and other fundamental units of the vertebrate immune system. For example, GO enrichment analysis revealed that genes positively associated with DWV-A were enriched for iron metabolism, and viral hijacking of iron metabolism has been associated with poor prognosis in HIV-1 and hepatitis C infection in humans, as iron accumulation provides an ideal environment for viral replication51. Another link to human disease was aldh, positively associated with DWV-A in all four studies, which was shown to offer a neuroprotective function in Parkinson’s disease-associated neurodegeneration of dopaminergic cells52.

We found Idgf4, a chitinase-related gene associated with chitin organization and cuticle development53, to be positively associated with DWV-A in all four studies. Chitinase and chitinase-related genes are an evolutionarily conserved family of hydrolases synthesized in both insects and mammals54. Though mammals do not synthesize chitin, these hydrolases have been implicated in the pathogenesis of inflammatory responses in several human disorders55,56, and expression of the mammalian chitinase-3-like protein 1 is increased in astrocytes following traumatic brain injury57. These results suggest that viral and host responses contain some deeply conserved components. Moreover, expression of Idgf4 was shown to increase in the abdominal integuments with the onset of foraging in honey bees and another social bee species58, supporting our hypothesis that DWV-A infection affects molecular pathways associated with behavioral maturation. While Idgf4 does not have chitinase activity, it likely promotes cell growth and development, the function of which is unclear in the post-mitotic adult brain59. Idgf4 expression was positively correlated with sexual maturation in the neural ganglia of the female Pacific abalone (Haliotis discus hannai)60, implying that it has broad maturation-related functionality in different tissue types, including neural.

Our results suggest that DWV-A drives a forager-like neurogenomic state in infected individuals, as the profile of genes positively associated with DWV-A resembles the profile upregulated in foragers but not nurses42,43. This was surprising, considering that the majority of bees in this meta-analysis were nurse-age, and thus considerably younger than the normal foraging age. Early-onset or “precocious” foraging, which represents an acceleration of behavioral maturation, has been linked to CCD via both computational and empirical studies61,62. We found this trend in workers but not drones, which do not forage. This is consistent with the finding that although high DWV titers have been identified in the drone endophallus, Yañez et al. demonstrated that infection does not impact drone mating flight performance63.

DWV-A infection was also associated with changes in the brain transcriptional regulatory architecture underlying behavioral maturation. Three transcription factors, atf3, hairy, and cwo, which our TRN model predicted to regulate many genes in the context of DWV-A infection, have previously also been computationally predicted to cause precocious foraging based on several different gene regulatory analyses of honey bee brains. For example, atf3, which is necessary for protein kinase A signaling64, was predicted to be involved in the initiation or maintenance of the foraging state42. Similarly, motifs associated with both hairy and cwo were found to be enriched in the promoter region of over half the genes upregulated in the brains of foragers relative to nurses and may therefore also be related to precocious foraging42. Our findings thus provide a suggestive link between viral infection and behavioral maturation, the latter of which has been linked to colony decline36,61. These three TFs in particular were implicated in Studies 2 and 4, which contain worker bees that were considerably younger than normal foraging age. Therefore, the impact of DWV-A on behavioral maturation may be exaggerated in younger bees who would not forage for several weeks under normal conditions. Perhaps DWV-A impacts transcriptional regulation differently in infected foragers, such as those in Study 1.

We suggest that these specific viral-associated neurogenomic effects on workers may promote horizontal viral transmission by facilitating spread between colonies. Foragers are more likely than nurses to accidentally enter (“drift”) into a foreign colony, and precocious foragers may be even more likely to drift than normal-age foragers. Precocious foraging also is associated with poor spatial memory relative to normal-age foragers35, and specific DWV-A induced learning deficits have been reported26. Moreover, the drifting of DWV-A infected workers may be more likely to occur under crowded modern apiary conditions. One interpretation of our findings is that DWV is manipulating host behavior to promote its spread. However, a variety of proximate stress factors cause precocious foraging, such as starvation65, infection by the protozoan Nosema66, Varroa mite infestation during development67, and a loss of normal-age foragers34, so it will be important to conduct additional studies to test this hypothesis. Given that precocious behavioral maturation is associated with colony decline61,62, understanding the evolutionary dynamics of the DWV-honey bee pathogen-host relationship is of considerable importance.

It was surprising to observe that scRNA-Seq analysis detected a cluster of cells in the brain with gene expression profiles that identify them as glia. We base this tentative conclusion on the observation that this cell cluster lacked the neuronal marker elav but was distinguished from other clusters by a relative abundance of repo and Gs2, two canonical markers of glia in insects46,47. In addition to expressing compelling molecular markers indicating glia, rather than neurons, we note that the small size of the cluster represents only ~3% of the ~2,200 sequenced cells, and glia in the insect brain have been estimated to number less than 10%, unlike the ~1:1 ratio split in vertebrates68–70. Because the scRNA-Seq samples were not infected with DWV-A, one possibility is that the molecular signature of DWV-A, common to all four datasets, is driven by gene expression primarily in activated glia cells. An alternative, nonexclusive, explanation is that infection stimulates molecular mechanisms in neurons that resemble the resting state of glia. In ladybird beetles (Coleomegilla maculata), infection with Dinocampus coccinellae paralysis virus (DcPV), which, like DWV, is also a picorna-like virus, similarly localized to glial cytoplasm in the brain, thus compromising host survival71. In the developing human brain, radial glia and astrocytes are more susceptible than neurons to infection by the flavivrus Zika72. Interestingly, we found ebony, which is activated in glia to generate circadian locomotion in Drosophila, to be positively associated with DWV-A in Studies 2 and 3 (Supplementary Tables S2 and S3, respectively). Circadian locomotion is a hallmark of honey bee foragers compared to nurses, which are arrhythmic73; thus, we speculate that glia may be playing a role in accelerating behavioral maturation. Because our results are derived from bioinformatic analyses of scRNA-Seq, we do not yet know the exact role of honey bee glia in the context of DWV infection. Further studies will be required to strengthen the link between glia-mediated viral response and its potential impact on behavior.

Given the accumulating evidence that picorna-like viruses cause cognitive impairment, in both vertebrates and invertebrates26,74, and given the strong effects of DWV-A on brain gene expression reported here, why was the DWV-A infection in all four studies covert, with no obvious effects on behavior? One possibility is that the behaviors of interest in those studies (reward responsiveness [Studies 1 and 3], aggression [Study 2], and caregiving [Study 4]) are subserved by different neural and molecular processes than those impacted by DWV-A infection. Another explanation is the advantage conferred to DWV-A via precocious foraging: infected bees that progress to a foraging state can do a better job spreading the virus between colonies than those that either succumb to infection or are ejected by their nestmates. Our findings thus far are specific to DWV-A, which is the predominant viral variant in North America22,75; future research will be necessary to determine if DWV-B and -C have similar impact on brain gene expression in adult honey bees. A better understanding of the ways in which DWV and other bee viruses affects brain and behavior will be important to future efforts aimed at reversing colony loss.

Methods

Datasets included in meta-analysis

We included 325 bees from four independent studies conducted at the University of Illinois Bee Research Facility in Urbana, IL between 2012 and 2014. For each study, source colonies containing honey bees were maintained according to standard beekeeping practices. Studies 1 and 3 used colonies headed by a naturally mated queen, and colonies for Studies 2 and 4 were headed by a queen instrumentally inseminated with semen from a single drone to reduce genetic variability between individuals. Study 3 only involved drones, which develop from unfertilized eggs and were therefore unaffected by queen insemination. Behavioral collections were made either directly from these colonies or from small cages of bees kept in a laboratory incubator that mimics in-hive conditions (34 ± 1 °C, 45 ± 10% relative humidity), as previously described30,40,76. No bees collected displayed physical symptoms of DWV (e.g., misshapen wings, immobility, differences in body size), nor did any show diminished responsiveness to investigators in the four respective studies. For collections, bees were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen following a given experimental paradigm and stored at −80 °C until brain dissection and RNA extractions. Full experimental details, which apply to all four datasets, regarding sample collection, brain dissection, RNA extraction and RNA-Seq are described in the respective Methods sections of the two published datasets29,40, with the exception that Study 4 utilized the entire honey bee brain instead of the MB alone. All datasets are available for public access on the Gene Expression Omnibus database, respective accession IDs as follows: GSE130701 (Study 1), GSE85878 (Study 2), GSE130702 (Study 3), GSE130700 (Study 4).

RNA-Sequencing analysis

We reprocessed original raw data for each dataset. Raw reads were mapped to the most recent A. mellifera genome assembly, build HAv3.177, and the Deformed wing virus reference genome (GenBank accession number AJ48974419) using the STAR (v2.5.3) aligner with default settings78. Numbers of reads were counted using the featureCounts79 command in the Subread package (v1.5.2)80. Because we could not arbitrarily assign “high” and “low” levels of infection to datasets that are ubiquitously contaminated, we did not discretize samples by number of DWV reads. To normalize brain gene expression across the datasets, we calculated gene expression levels using %DWV (Fig. 1) as a covariate in a generalized linear model that included honey bee source colony as a blocking factor (for all experiments except Study 3, which only included a single colony) using edgeR81 (v3.24.3) in R (v3.5.2). We used the Benjamini-Hochberg (BH) correction for multiple testing82 and filtered lists of DWV-associated genes based on a threshold of FDR < 0.05.

Gene list analyses

Gene list overlap analyses were conducted with the GeneOverlap83 and SuperExactTest84 packages in R. We used hypergeometric tests to calculate the statistical significance of observed gene list overlap compared to overlap expected by random chance, and calculated BH-corrected p values as noted in the text. A gene list universe of 8567 genes was used based on the 4-way overlap across the datasets. For Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis, we first converted honey bee genes to Drosophila melanogaster orthologs via a one-to-one reciprocal best hit BLAST (v2.8.0; Supplementary Table 21)85. Lists containing genes differentially expressed in ≥ 2 datasets were then submitted to the GOrilla database and visualized using REVIGO37,86,87.

Lists of genes positively associated with DWV were then compared to published transcriptome data associated with nurse or foraging state. To obtain an unbiased list of nurse- and forager-upregulated genes, we used directionally concordant genes validated between two independent studies comparing nurses and foragers42,43. Pairwise comparisons were performed as described above.

Transcriptional regulatory network construction

We used the Analyzing Subsets of Transcriptional Regulators Influencing eXpression (ASTRIX)88 approach to predict transcription factors (TFs) associated with DWV infection with an approach that used information from all four data sets. Using ASTRIX, we inferred a TRN by combining gene expression data from each study. A regulatory interaction was inferred via gene expression between a TF and its target based on co-expression: the predicted targets of TFs were defined as genes that share high mutual information (p < 10−6) with a TF and have a high predictive ability (correlation r > 0.8). A previous study88 validated ASTRIX-generated TF-target associations using data from ModENCODE89, REDfly90, and DroID91 databases. To assess the regulatory influence of each highly connected TF in the context of DWV infection, we tested for enrichment of its targets in each DWV-associated gene list using a Bonferroni FDR-corrected hypergeometric test with a cutoff of FDR < 0.05.

ABC and CBA assay

We performed quantitative reverse transcription PCR (RT-qPCR) on 35 whole-brain samples from Study 4 (Fig. 3). RNA was extracted from whole brains using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) following overnight incubation in RNAlater-ICE (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), as previously described76. RT-qPCR was performed on the RNA alongside a ten-fold dilution series of DWV variant-specific capsid or RdRp RNA standard curves using a Power SYBR® Green RNA-to-CT™ 1-Step Kit (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA). Each reaction contained 5 μL Power SYBR® Green RNA-to-CT PCR mix, 1 μL forward primer, 1 μL reverse primer for DWV-A, B or C Capsid [Highfield et al., in preparation] or RdRp region45, 0.08 μL reverse transcriptase, 1.92 μL RNase free H2O and 1 μL template RNA. The reverse transcription step occurred at 45 °C for 10 min and denaturation at 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturizing at 95 °C for 15 sec, annealing at 58.5 °C for the capsid DWV-A, B, and C primers, RdRp DWV-A or B and at 61 °C for DWV-C RdRp primer for 15 sec and extension at 72 °C for 15 sec. A melt curve analysis was performed between 72 °C and 95 °C, at 0.1 °C increments, each with a 5 sec hold period. This step ensured that no contamination was present in the negative template controls and that only one product was amplified per primer set. Each sample was analyzed in duplicate. Copy numbers were determined using the following equation: (Concentration RNA (ng/µL) × 6.022 × 1023) (Fragment length base pairs × 109 × 325). Genome equivalents per bee were calculated using the following equation: (Average copy number × RNA volume) x proportion of bee tissue (see Figshare link for raw data).

Single-cell RNA-Sequencing

We collected two seven-day-old adult worker honey bees from one source colony headed by a queen instrumentally inseminated with semen from a single drone (to increase genetic similarity among the bees). Brains were fresh-dissected in ice-cold Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS), and the mushroom boides (MB) were dissected in one sample. Both samples were then cut into small pieces and incubated for 2 min in an Eppendorf tube containing 90 μl of DPBS and 10 μl of 0.25% Trypsin with 2.21 mM EDTA. Next, 90 μl of the solution was removed and replaced with DPBS, and brain tissue was gently triturated with a pipette tip to dissociated cells. Fixation and rehydration were carried out in accordance with 10x protocols, with a 15 min methanol fixation on ice and storage at −20 °C for less than one week before rehydration and sequencing. scRNA-Seq libraries were constructed with the Chromium Single Cell 3′ Library and Gel Bead Kit v2 and were sequenced on a 2 × 150 nt lane on a HiSeq 4000 (Illumina, San Diego, CA). Raw and processed scRNA-Seq reads can be found under GEO accession ID GSE130785.

Raw scRNA-Seq reads were aligned to the honey bee genome (HAv3.177) using Cell Ranger 3.0.1, and over 93% of sequenced reads mapped to the genome. For both WB and MB samples, we identified ~1,300 cells with an average of ~143,000 reads and a median of ~1,400 genes per cell. All following steps were performed with Seurat 3.0. We performed data normalization with default settings and combined the whole brain (WB) and MB datasets using the “merge” function, which predicted 13 cellular subpopulations via t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (tSNE) clustering. To identify the molecular profile of each cell population, we used the “FindAllMarkers” function in Seurat which performs a Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test to test for differentially expressed genes per tSNE cluster. We found no evidence of DWV contamination in either of our samples.

Next, we performed a series of hypergeometric tests to compare genes positively associated with DWV-A in the four analyzed datasets and genes upregulated in each of the 13 scRNA-Seq clusters using the SuperExactTest83 package. After performing BH correction for multiple comparisons, we reported significant FE at FDR < 0.05.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank D. Charlie Nye and Alison Sankey for beekeeping assistance; Drs. Sihai Dave Zhao, Michael Saul and Chris Fields for helpful discussions that inspired this project; and members of the Robinson Lab for feedback leading to considerable improvements of this manuscript. This research was funded by grant SFLife 291812 from the Simons Foundation, an NIH Pioneer Award (DP1 OD006416), an R01 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (#R01-GM117467), the Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (all to G.E.R), and the Bee Disease Insurance LTD (to D.C.S).

Author contributions

I.M.T. analyzed previously generated whole-tissue RNA-Sequencing data and performed molecular and bioinformatic components of single-cell RNA-Sequencing. S.A.B. performed the transcriptional regulatory network analysis. I.M.T., A.C.A. and A.R.H. extracted and prepared RNA for qPCR analyses, which were conducted by J.K. and D.C.S. N.L.N. and A.R.H. generated the unpublished data for Studies 3 and 4, respectively. I.M.T. and G.E.R. interpreted the results and wrote the manuscript.

Data availability

Whole-tissue and scRNA-Seq data can be found on GEO, accession IDs presented in Table 1 and in Methods. R scripts for performing TRN analysis can be found at https://github.com/bukhariabbas/DWVTrn. All remaining raw data and R scripts can be accessed at 10.6084/m9.figshare.8341187.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-020-59808-4.

References

- 1.Steffan-Dewenter I, Potts SG, Packer L. Pollinator diversity and crop pollination services are at risk. Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 2005;20:651–652. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klein A-M, et al. Importance of pollinators in changing landscapes for world crops. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2007;274:303–313. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2006.3721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.vanEngelsdorp D, et al. A survey of honey bee colony losses in the U.S., Fall 2007 to Spring 2008. Plos One. 2008;3:e4071. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.vanEngelsdorp D, et al. Colony collapse disorder: a descriptive study. Plos One. 2009;4:e6481. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ellis, J. D., Evans, J. D. & Pettis, J. Colony losses, managed colony population decline, and Colony Collapse Disorder in the United States. Journal of Apicultural Research49, 134–136 (2010).

- 6.Le Conte Y, Ellis M, Ritter W. Varroa mites and honey bee health: can Varroa explain part of the colony losses? Apidologie. 2010;41:353–363. doi: 10.1051/apido/2010017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xie X, Huang ZY, Zeng Z. Why do Varroa mites prefer nurse bees? Scientific Reports. 2016;6:28228. doi: 10.1038/srep28228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee KV, et al. A national survey of managed honey bee 2013–2014 annual colony losses in the USA. Apidologie. 2015;46:292–305. doi: 10.1007/s13592-015-0356-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dietemann V, et al. Varroa destructor: research avenues towards sustainable control. Journal of Apicultural Research. 2012;51:125–132. doi: 10.3896/IBRA.1.51.1.15. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Francis RM, Nielsen SL, Kryger P. Varroa-virus interaction in collapsing honey bee colonies. Plos One. 2013;8:e57540. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Allen M, Ball B. The incidence and world distribution of honey bee viruses. Bee World. 1996;77:141–162. doi: 10.1080/0005772X.1996.11099306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grozinger CM, Flenniken ML. Bee viruses: ecology, pathogenicity, and impacts. Annual Review of Entomology. 2019;64:205–226. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ento-011118-111942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen Y, Pettis JS, Evans JD, Kramer M, Feldlaufer MF. Transmission of Kashmir bee virus by the ectoparasitic mite Varroa destructor. Apidologie. 2004;35:441–448. doi: 10.1051/apido:2004031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shen M, Yang X, Cox-Foster D, Cui L. The role of varroa mites in infections of Kashmir bee virus (KBV) and deformed wing virus (DWV) in honey bees. Virology. 2005;342:141–149. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shen M, Cui L, Ostiguy N, Cox-Foster D. Intricate transmission routes and interactions between picorna-like viruses (Kashmir bee virus and sacbrood virus) with the honeybee host and the parasitic varroa mite. Journal of General Virology. 2005;86:2281–2289. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.80824-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Di Prisco G, et al. Varroa destructor is an effective vector of Israeli acute paralysis virus in the honeybee, Apis mellifera. Journal of General Virology. 2011;92:151–155. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.023853-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilfert L, et al. Deformed wing virus is a recent global epidemic in honeybees driven by Varroa mites. Science. 2016;351:594–597. doi: 10.1126/science.aac9976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bailey, L. & Ball, B. V. Viruses. In Honey Bee Pathology 10–34 (Elsevier, 1991).

- 19.Lanzi G, et al. Molecular and biological characterization of deformed wing virus of honeybees (Apis mellifera L.) Journal of Virology. 2006;80:4998–5009. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.10.4998-5009.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mordecai GJ, Wilfert L, Martin SJ, Jones IM, Schroeder DC. Diversity in a honey bee pathogen: first report of a third master variant of the Deformed Wing Virus quasispecies. The ISME Journal. 2016;10:1264–1273. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2015.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martin SJ, et al. Global honey bee viral landscape altered by a parasitic mite. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2012;336:1304–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1220941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kevill JL, et al. DWV-A lethal to honey bees (Apis mellifera): a colony level survey of DWV variants (A, B, and C) in England, Wales, and 32 states across the US. Viruses. 2019;11:426. doi: 10.3390/v11050426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Natsopoulou ME, et al. The virulent, emerging genotype B of Deformed wing virus is closely linked to overwinter honeybee worker loss. Scientific Reports. 2017;7:5242. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-05596-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Highfield AC, et al. Deformed wing virus implicated in overwintering honeybee colony losses. Applied and environmental microbiology. 2009;75:7212–20. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02227-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shah KS, Evans EC, Pizzorno MC. Localization of deformed wing virus (DWV) in the brains of the honeybee, Apis mellifera Linnaeus. Virology Journal. 2009;6:182. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-6-182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Iqbal J, Mueller U. Virus infection causes specific learning deficits in honeybee foragers. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2007;274:1517–21. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2007.0022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wells T, et al. Flight performance of actively foraging honey bees is reduced by a common pathogen. Environmental Microbiology Reports. 2016;8:728–737. doi: 10.1111/1758-2229.12434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dainat B, Evans JD, Chen YP, Gauthier L, Neumann P. Dead or alive: deformed wing virus and Varroa destructor reduce the life span of winter honeybees. Applied and environmental microbiology. 2012;78:981–7. doi: 10.1128/AEM.06537-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McNeill MS, Kapheim KM, Brockmann A, McGill TAWW, Robinson GE. Brain regions and molecular pathways responding to food reward type and value in honey bees. Genes, Brain and Behavior. 2015;15:305–317. doi: 10.1111/gbb.12275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shpigler HY, et al. Honey bee neurogenomic responses to affiliative and agonistic social interactions. Genes, Brain and Behavior. 2018;18:e12509. doi: 10.1111/gbb.12509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kovac H, Crailsheim K. Lifespan of Apis Mellifera Carnica Pollm. infested by Varroa Jacobsoni Oud. in relation to season and extent of infestation. Journal of Apicultural Research. 1988;27:230–238. doi: 10.1080/00218839.1988.11100808. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Doublet V, et al. Unity in defence: honeybee workers exhibit conserved molecular responses to diverse pathogens. BMC Genomics. 2017;18:207. doi: 10.1186/s12864-017-3597-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Benaets K, et al. Covert deformed wing virus infections have long-term deleterious effects on honeybee foraging and survival. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2017;284:20162149. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2016.2149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang Z-Y, Robinson GE. Regulation of honey bee division of labor by colony age demography. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 1996;39:147–158. doi: 10.1007/s002650050276. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ushitani T, Perry CJ, Cheng K, Barron AB. Accelerated behavioural development changes fine-scale search behaviour and spatial memory in honey bees (Apis mellifera L.) Journal of Experimental Biology. 2016;219:412–8. doi: 10.1242/jeb.126920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peng F, et al. A simple computational model of the bee mushroom body can explain seemingly complex forms of olfactory learning and memory. Current Biology. 2017;27:224–230. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.10.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eden E, Navon R, Steinfeld I, Lipson D, Yakhini Z. GOrilla: a tool for discovery and visualization of enriched GO terms in ranked gene lists. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10:48. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seeley TD. Adaptive significance of the age polyethism schedule in honeybee colonies. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 1982;11:287–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00299306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Winston, M. L. The Biology of the Honey Bee. (Harvard University Press, 1991).

- 40.Shpigler HY, et al. Behavioral, transcriptomic and epigenetic responses to social challenge in honey bees. Genes, Brain and Behavior. 2017;16:579–591. doi: 10.1111/gbb.12379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Traniello IM, Chen Z, Bagchi VA, Robinson GE. Valence of social information is encoded in different subpopulations of mushroom body Kenyon cells in the honeybee brain. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2019;286:20190901. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2019.0901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Khamis AM, et al. Insights into the transcriptional architecture of behavioral plasticity in the honey bee Apis mellifera. Scientific Reports. 2015;5:11136. doi: 10.1038/srep11136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Alaux C, et al. Regulation of brain gene expression in honey bees by brood pheromone. Genes, Brain and Behavior. 2009;8:309–319. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2009.00480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thurmond J, et al. FlyBase 2.0: the next generation. Nucleic Acids Research. 2019;47:D759–D765. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kevill J, et al. ABC assay: method development and application to quantify the role of three DWV master variants in overwinter colony losses of European honey bees. Viruses. 2017;9:314. doi: 10.3390/v9110314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xiong WC, Okano H, Patel NH, Blendy JA, Montell C. repo encodes a glial-specific homeo domain protein required in the Drosophila nervous system. Genes & Development. 1994;8:981–94. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.8.981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shah AK, Kreibich CD, Amdam GV, Münch D. Metabolic enzymes in glial cells of the honeybee brain and their associations with aging, starvation and food response. Plos One. 2018;13:e0198322. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0198322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brutscher LM, Daughenbaugh KF, Flenniken ML. Virus and dsRNA-triggered transcriptional responses reveal key components of honey bee antiviral defense. Scientific Reports. 2017;7:6448. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-06623-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Johnson RM, Evans JD, Robinson GE, Berenbaum MR. Changes in transcript abundance relating to colony collapse disorder in honey bees (Apis mellifera) Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:14790–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906970106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brutscher LM, Flenniken ML. RNAi and antiviral defense in the honey bee. Journal of Immunology Research. 2015;2015:941897. doi: 10.1155/2015/941897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Drakesmith H, Prentice A. Viral infection and iron metabolism. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2008;6:541–552. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu G, et al. Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 defines and protects a nigrostriatal dopaminergic neuron subpopulation. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2014;124:3032–3046. doi: 10.1172/JCI72176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pesch Y-Y, Riedel D, Patil KR, Loch G, Behr M. Chitinases and Imaginal disc growth factors organize the extracellular matrix formation at barrier tissues in insects. Scientific Reports. 2016;6:18340. doi: 10.1038/srep18340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chupp GL, et al. A chitinase-like protein in the lung and circulation of patients with severe asthma. New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;357:2016–2027. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lee CG, et al. Role of chitin and chitinase/chitinase-like proteins in inflammation, tissue remodeling, and injury. Annual Review of Physiology. 2011;73:479–501. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-012110-142250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kawada M, Hachiya Y, Arihiro A, Mizoguchi E. Role of mammalian chitinases in inflammatory conditions. The Keio Journal of Medicine. 2007;56:21–7. doi: 10.2302/kjm.56.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wiley CA, et al. Role for mammalian chitinase 3-like protein 1 in traumatic brain injury. Neuropathology. 2015;35:95–106. doi: 10.1111/neup.12158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Falcon T, et al. Exploring integument transcriptomes, cuticle ultrastructure, and cuticular hydrocarbons profiles in eusocial and solitary bee species displaying heterochronic adult cuticle maturation. Plos One. 2019;14:e0213796. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0213796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Varela PF, Llera AS, Mariuzza RA, Tormo J. Crystal structure of imaginal disc growth factor-2. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277:13229–13236. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110502200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kim MA, et al. Neural ganglia transcriptome and peptidome associated with sexual maturation in female Pacific abalone (Haliotis discus hannai) Genes. 2019;10:268. doi: 10.3390/genes10040268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Perry CJ, Søvik E, Myerscough MR, Barron AB. Rapid behavioral maturation accelerates failure of stressed honey bee colonies. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2015;112:3427–32. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1422089112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Khoury DS, Myerscough MR, Barron AB. A quantitative model of honey bee colony population dynamics. Plos One. 2011;6:e18491. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yañez O, et al. Deformed wing virus and drone mating flights in the honey bee (Apis mellifera): implications for sexual transmission of a major honey bee virus. Apidologie. 2012;43:17–30. doi: 10.1007/s13592-011-0088-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chu HM, Tan Y, Kobierski LA, Balsam LB, Comb MJ. Activating transcription factor-3 stimulates 3′,5′-cyclic adenosine monophosphate-dependent gene expression. Molecular Endocrinology. 1994;8:59–68. doi: 10.1210/mend.8.1.8152431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Schulz DJ, Huang Z-Y, Robinson GE. Effects of colony food shortage on behavioral development in honey bees. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 1998;42:295–303. doi: 10.1007/s002650050442. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Goblirsch M, Huang ZY, Spivak M. Physiological and behavioral changes in honey bees (Apis mellifera) induced by Nosema ceranae infection. Plos One. 2013;8:e58165. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Downey DL, Higo TT, Winston ML. Single and dual parasitic mite infestations on the honey bee, Apis mellifera L. Insectes Sociaux. 2000;47:171–176. doi: 10.1007/PL00001697. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yildirim K, Petri J, Kottmeier R, Klämbt C. Drosophila glia: few cell types and many conserved functions. Glia. 2019;67:5–26. doi: 10.1002/glia.23459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kretzschmar D, Pflugfelder G. Glia in development, function, and neurodegeneration of the adult insect brain. Brain Research Bulletin. 2002;57:121–131. doi: 10.1016/S0361-9230(01)00643-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Edwards TN, Meinertzhagen IA. The functional organisation of glia in the adult brain of Drosophila and other insects. Progress in Neurobiology. 2010;90:471–497. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dheilly NM, et al. Who is the puppet master? Replication of a parasitic wasp-associated virus correlates with host behaviour manipulation. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2015;282:20142773–20142773. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2014.2773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Retallack H, et al. Zika virus cell tropism in the developing human brain and inhibition by azithromycin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2016;113:14408–14413. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1618029113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bloch G, Toma DP, Robinson GE. Behavioral rhythmicity, age, division of labor and period expression in the honey bee brain. Journal of Biological Rhythms. 2001;16:444–456. doi: 10.1177/074873001129002123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Buenz EJ, Rodriguez M, Howe CL. Disrupted spatial memory is a consequence of picornavirus infection. Neurobiology of Disease. 2006;24:266–273. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.McMahon DP, et al. Elevated virulence of an emerging viral genotype as a driver of honeybee loss. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2016;283:20160811. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2016.0811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rittschof CC, et al. Neuromolecular responses to social challenge: common mechanisms across mouse, stickleback fish, and honey bee. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2014;111:17929–34. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1420369111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wallberg A, et al. A hybrid de novo genome assembly of the honeybee, Apis mellifera, with chromosome-length scaffolds. BMC Genomics 2019 20:1. 2019;20:275. doi: 10.1186/s12864-019-5642-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dobin A, et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:15–21. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Liao Y, Smyth GK, Shi W. featureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:923–930. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Liao Y, Smyth GK, Shi W. The Subread aligner: fast, accurate and scalable read mapping by seed-and-vote. Nucleic Acids Research. 2013;41:e108–e108. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:139–40. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing on JSTOR. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B: Methodological. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Shen, L. GeneOverlap: An R package to test and visualize gene overlaps. (2014).

- 84.Wang M, Zhao Y, Zhang B. Efficient test and visualization of multi-set intersections. Scientific Reports. 2015;5:16923. doi: 10.1038/srep16923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Camacho C, et al. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10:421. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hong G, Zhang W, Li H, Shen X, Guo Z. Separate enrichment analysis of pathways for up- and downregulated genes. Journal of the Royal Society, Interface. 2014;11:20130950. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2013.0950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Supek F, Bošnjak M, Škunca N, Šmuc T. REVIGO summarizes and visualizes long lists of gene ontology terms. Plos One. 2011;6:e21800. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Chandrasekaran S, et al. Behavior-specific changes in transcriptional modules lead to distinct and predictable neurogenomic states. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:18020–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1114093108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Celniker SE, et al. Unlocking the secrets of the genome. Nature. 2009;459:927–930. doi: 10.1038/459927a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Gallo SM, et al. REDfly v3.0: toward a comprehensive database of transcriptional regulatory elements in Drosophila. Nucleic Acids Research. 2011;39:D118–D123. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Murali Thilakam, Pacifico Svetlana, Yu Jingkai, Guest Stephen, Roberts George G., Finley Russell L. DroID 2011: a comprehensive, integrated resource for protein, transcription factor, RNA and gene interactions for Drosophila. Nucleic Acids Research. 2010;39(suppl_1):D736–D743. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Whole-tissue and scRNA-Seq data can be found on GEO, accession IDs presented in Table 1 and in Methods. R scripts for performing TRN analysis can be found at https://github.com/bukhariabbas/DWVTrn. All remaining raw data and R scripts can be accessed at 10.6084/m9.figshare.8341187.