Abstract

Purpose of Review:

To examine the potential role of ovarian hormones in biological vulnerability to borderline personality disorder (BPD). The review focuses primarily on research examining the menstrual cycle as a source of short-term lability of BPD symptom expression, while discussing the currently understudied possibility of ovarian hormone influence in the developmental course of BPD.

Findings:

Several patterns of menstrual cycle effects on BPD symptoms and relevant features in non-clinical samples have been observed in empirical studies. Most symptoms demonstrated patterns consistent with peri-menstrual exacerbation; however, timing varied between high and low arousal symptoms, potentially reflecting differing mechanisms. Symptoms are typically lowest around ovulation, with an exception for proactive aggression and some forms of impulsive behaviors.

Summary:

Preliminary evidence suggests ovarian hormones may exert strong effects on BPD symptom expression, and further research is warranted examining mechanisms and developing interventions. Recommendations for researchers and clinicians working with BPD are provided.

Keywords: Menstrual Cycle, Estradiol, Progesterone, Borderline Personality Disorder, Premenstrual Exacerbation, Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder

Introduction

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is characterized by rapidly shifting emotional, interpersonal, and behavioral symptoms, including intense affect, identity disturbance, impulsive and self-destructive behavior, aggression, and chaotic relationships [1]. The lability of these symptoms makes them hard to predict and therefore more challenging to manage and treat. Identifying detectable factors contributing to symptom variability would improve the ability of researchers, patients, and providers to predict symptom changes and maximize effects of interventions. Cyclical biological systems with the potential to influence psychiatric symptoms may provide key insights into explaining components of both short-term lability of and longer-term developmental changes in BPD symptom expression. Female reproductive hormones are a prime candidate to consider as a biological source of variability, given the changes occurring both across the lifespan (puberty, pregnancy, menopause) and within the monthly menstrual cycle.

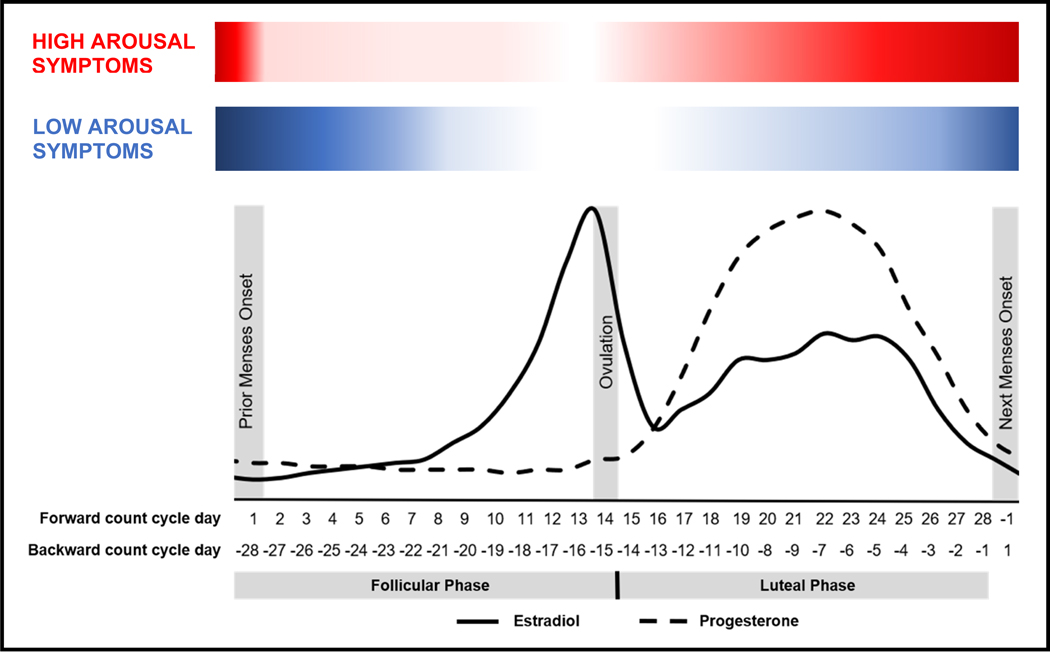

The menstrual cycle prototypically occurs over 28 days, divided into two sections (see Figure 1). The follicular phase (beginning at onset of menses, continuing through ovulation) is characterized by continuous low levels of progesterone (P4) combined with increasing levels of estradiol (E2), peaking just prior to ovulation. The luteal phase begins following ovulation and continuing through the day before onset of the following menses. In the week after ovulation, both E2 and P4 rise and peak, and then both fall in the week before menses. In conjunction with their effects on the reproductive system, both P4 and E2 exert direct effects on the central nervous system, including the majority of neural systems implicated in emotional disorders [2]. Although most females do not experience clinically significant changes in their mood and behavior across the menstrual cycle [3], a growing body of work indicates strong individual differences in sensitivity to normal hormone changes (“hormone sensitivity”) that cause some women to experience severe symptoms (or worsening of pre-existing symptoms) in the luteal phase and especially around the onset of menses [4]. Similar individual differences in hormone sensitivity have been identified in pregnancy [5] and the menopause transition [6–8], and likely also exist during puberty [9]; however, given the dearth of literature on BPD during these other reproductive transitions, the present review will focus on the menstrual cycle.

Figure 1.

Proposed Model of Menstrual Cycle Symptom Exacerbation of High and Low Arousal Symptoms in Borderline Personality Disorder

Relatively little work to date directly examines the role of female reproductive hormones in BPD; however, multiple components of the extant literature on BPD suggest the possibility that hormone sensitivity across the menstrual cycle and the reproductive lifespan may play a role in biological vulnerability to BPD symptom expression. Within female individuals, BPD symptoms tend to emerge in adolescence, peaking shortly after puberty at approximately age 15 years [10]. Experiences of childhood abuse are prevalent among individuals with BPD [11], and early stressful and invalidating experiences are theorized to be key components of BPD’s etiology [12]; childhood adversity and stressors also appear to exacerbate hormone sensitivity [13–16], suggesting the potential of heightened hormone sensitivity in females as a mechanism through which these early life experiences may contribute to the emotional vulnerability characteristic of BPD.

Of note, while the possibility of fluctuating biological vulnerability to BPD symptoms across the menstrual cycle may be useful for improving predictability and treatment of symptoms in females with BPD, they do not necessarily imply sex differences in the overall occurrence or severity of BPD. Findings on sex ratios in BPD are mixed, with some indicating higher rates of diagnosis in clinical settings in females [17], perhaps due to higher female treatment utilization rates [18], but most recent studies find similar rates of BPD in female and male participants [17, 19]. Within individuals meeting criteria for BPD, findings also vary, with some studies more symptomology overall in female patients [20], including greater affective instability, hostility, and emptiness than males [20–22], but another recent study found more impulsive and aggressive behavior in male patients, with similar rates of suicidal behavior across sexes but more lethal attempts for males [23]. In another sample, typical general population sex differences in aggressive behavior and suicidality were attenuated in BPD patients, due to higher than usual levels of female aggression and higher than usual levels of male suicidal ideation [20]. Given these mixed findings, it remains unclear exactly what sex differences may exist in BPD, perhaps in part due to the heterogenous nature of the disorder. A key methodological limitation is that most of these studies utilize cross-sectional diagnostic interviews and self-report measures. Modeling BPD symptom variability longitudinally may be essential to understand sex differences in symptom expression, given that if reproductive hormones differentially affect vulnerability, these effects might be observed only if females’ symptoms are measured during phases of hormone-related vulnerability. It is also possible, and worthy of further research, that similar within-person steroid mechanisms (e.g., sensitivity to random or stress-related testosterone changes) play a role in some hormone-sensitive males with BPD, but are simply less predictable due to lack of monthly cycling [24].

PME of Mood Disorders and Non-Clinical BPD features

Findings within the broader literature on premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) and premenstrual exacerbation (PME) of underlying psychiatric disorders also suggest potential relevance for BPD. The most common symptoms of PMDD and PME are increased anger and irritability and heightened sensitivity to rejection [25], both hallmarks of BPD [26, 27]. Furthermore, PME appears to be common in mood disorders broadly, occurring in rates as high as 60% of depressed women [28]. PME of bipolar disorder symptoms appears to occur at similar rates [29], and its presence predicts greater severity in course of illness.

Emerging work suggests a greater-than-average hormone sensitivity in those with BPD symptomology. Higher overall levels of emotion-related impulsivity (a core component of BPD [30, 31]) has been linked to increased severity of PME of mood symptoms in a clinical sample of women with clinically significant PMDD symptoms (N = 54) [32]. In a sample of undergraduate females, those with higher-than-average BPD features at baseline reported increased symptoms after starting oral contraceptives, compared to no changes or reductions in symptoms for those with lower BPD features taking contraceptives and control group participants of all levels of BPD features [33] (N =46). In another undergraduate sample, BPD features were at highest levels during cyclical steroid changes [33] (N = 57). In an undergraduate sample specifically recruited to include females with representation across a full range of BPD features (N = 40), those with generally higher levels of BPD features demonstrated peaks in their symptoms when their E2 levels were lower than average and P4 levels were higher than average, a pattern characteristic of the mid-luteal and perimenstrual phases [34].

PME of Symptoms in Clinical Samples with BPD

A small but emerging area of research specifically examines whether individuals diagnosed with BPD are also at elevated risk for PME and other forms of hormone sensitivity. One challenge in conducting this research is factoring in the role of psychotropic medication, given that selective-serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are both commonly prescribed to individuals with BPD and a first-line treatment for PMDD [35]. An early study found no evidence of elevated symptoms in the premenstrual relative to postmenstrual cycle phases in patients with BPD [36] (N = 14); however, participants were taking psychotropic medications, which could have reduced PME of symptoms in the study [36]. However, a recent study examining menstrual cycle effects on BPD symptom expression in an unmedicated, naturally cycling clinical sample [37] (N=15) found strong evidence for hormone sensitivity in the sample. In prospective daily assessments, several patterns of cycle-based symptom exacerbation emerged that were clinically significant for all but one participant. Of note, retrospective self-reports of at baseline indicated that the participants in the sample were not aware (i.e., did not report) that they were experiencing significant cyclical changes in their symptoms.

These results, while preliminary given the small sample, suggest that hormone sensitivity could play a role in the etiology and maintenance of BPD. Below, we highlight several key findings from the most recent study in this area [37], and note how these preliminary findings, along with extant research on hormones and related behaviors, point to hypotheses about the causes and consequences of hormone sensitivity in BPD.

High Arousal Symptoms

For females with BPD, preliminary work indicates that high arousal symptoms and those characterized by increased interpersonal reactivity—such as irritability, anger, reactive aggression, and rejection sensitivity—may rise in the luteal phase and peak in the perimenstrual phase, with lowest levels in the ovulatory phase [37] (see Figure 1). This pattern is generally consistent with findings from studies on PMDD demonstrating similarly timed elevations in symptoms of irritability and rejection sensitivity [25, 38], suggesting the possibility of a shared mechanism underlying PME of BPD and similar PMDD symptoms. The most plausible mechanism of these midluteal-onset, high-arousal symptoms is an altered plasticity of the GABA-A receptor that reverses the typical beneficial effects of GABAergic progesterone metabolites (e.g., allopregnanolone). This mechanism has been demonstrated in PMDD [39, 40] but has yet to be studied in midluteal-onset PME. Of note, while individuals with PMDD experience a drastic clearance of their symptoms to a non-clinical level during the follicular phase, individuals with BPD maintained significant, if lower, levels of symptoms across the cycle in the largest study to date [37]; therefore, it is unclear whether the pathophysiology of these midluteal-onset exacerbations is shared with PMDD. Of course, the potential for misdiagnosis in either direction exists, with either individuals with PMDD (i.e., those with luteal-phase-only symptoms) being misdiagnosed with BPD, or individuals with BPD (i.e., those with chronic symptoms, with or without PME) diagnosed with PMDD. Of note, a forthcoming study has identified temporal subtypes of PMDD characterized by early-onset (midluteal) and late-onset (premenstrual week) PMDD symptoms, and the former PMDD subgroup may be most likely to exhibit shared mechanisms with midluteal-onset PME of high arousal symptoms [41]. Experimental and longitudinal studies are needed to test possible mechanisms of shared luteal risk for high-arousal symptoms in various subtypes of PMDD and BPD.

Low Arousal Symptoms

Preliminary work suggests that lower-arousal symptoms of BPD, such as depression, shame, and hopelessness, while similarly at lowest points during ovulation, demonstrated PME with later onset and more prolonged elevation, rising in the perimenstrual phase and extending further into the follicular phase [37] (see Figure 1). This is inconsistent with the rapid follicular clearance of symptoms typically observed in PMDD with the onset of menses, suggesting the possibility of differing physiological mechanisms underlying shifts in these lower arousal symptoms among those with PME of BPD. Some have theorized that cycling individuals with BPD may also have greater sensitivity of serotonergic systems to E2 fluctuations, and it may be that this or other estrogen mechanisms underlie PME of low-arousal symptoms [34, 42]. This premenstrual-to-early-follicular phase pattern is also more similar to that observed in studies of cycle-based shifts in suicidality, a common symptom and criterion of BPD [43]. A greater proportion of suicide attempts and more lethal suicide attempts in cycling, at-risk individuals occur in the early follicular (i.e., menstrual) phase, when ovarian steroids are at lowest levels [44–46]. As noted above, a forthcoming study has identified temporal subtypes of PMDD characterized broadly by early-onset (midluteal) and late-onset (premenstrual week) symptoms; depression symptoms were generally characterized by a later onset than other symptoms, and the late-onset PMDD subgroup may be most likely to exhibit shared mechanisms with PME of low arousal symptoms [41]. Preliminary evidence from an experimental study suggest that E2 and P4 stabilization during typical hormone-withdrawal weeks of the cycle eliminates PME of suicidal ideation and planning around menses onset [47]. If increases in symptoms such as shame, depression, and hopelessness result from similar mechanisms, cyclical E2 or P4 stabilization may have promise as a treatment for menstrual cycle exacerbation of this broader class of symptoms in BPD as well. More research is needed to replicate these findings, to define whether it is E2 or P4 stabilization that may be most therapeutic and to determine the safest methods of administration. Finally, given that rumination has been found to prolong the duration of low-arousal symptoms in PMDD [32], it is possible that the higher trait levels of rumination and other negatively-valenced repetitive thought common in BPD [48–50] prolong PME of depression and other low-arousal symptoms.

Ovulatory Effects

Consistent with broader findings that for most cycling individuals, the ovulatory phase is characterized by less emotional and cognitive vulnerability [2, 51], the ovulatory phase was characterized by lowest levels of most BPD symptoms in the largest clinical study to date [37]. However, in contrast to findings for most other symptoms, individuals with BPD demonstrated highest levels of proactive aggression (aggression with the purpose to meet one’s needs [52]) during the ovulatory phase [53]. This ovulatory peak in proactive aggression aligns with non-clinical findings of ovulatory increases in rewarding and risky behavior, such as sex drive [54, 55], binge eating [56–58], binge drinking [59], and gambling behaviors [60], as well as ovulatory increases in assertive behavior [61]. Animal studies have demonstrated effects of E2 in upregulated dopaminergic reward processing systems [62–65], and cyclical increases of E2 in humans has been similarly shown to upregulate neural reward processing [66, 67]. For cycling individuals with BPD, the combined enhancement of cognitive resources [68], assertiveness, and reward drive at ovulation occurs within the context of negative cognitive biases that the world is hostile, dangerous, and untrustworthy [48]. This may be expressed as higher levels of proactive aggression in what is seen as the most viable way to achieve goals effectively. Further work should also examine whether the impulsive, appetitive behaviors common in BPD, such as substance abuse or risky sex [1], show similar ovulatory increases for individuals with the disorder.

Assessment of Menstrual Cycle Effects

Given that retrospective measures of cyclical symptom changes are prone to recall bias that produces a high rate of false positives, single-time-point self-report measures of premenstrual symptoms are not acceptable as evidence of such symptoms in research or for accurate clinical assessment. In order to conclude that a female has cyclical symptom change, symptoms must at least be measured at weekly (and preferably daily) intervals. In order to minimize false positives, repeated (daily) ratings must be used. The Carolina Premenstrual Assessment (C-PASS [69]) is a scoring system for two months of daily symptom ratings on the daily record of severity of problems [70] that can be used to measure both categorical diagnosis (of PME or PMDD) and dimensional degree of cyclical syptom change. A worksheet with detailed instructions, an excel macro, and a SAS macro are available for facilitating use of the C-PASS system [69].

Even for researchers studying BPD who are not primarily interested in ovarian hormones, it may be important to include or consider the menstrual cycle in research design and statistical models. For these purposes, menstrual cycle phase can be measured with acceptable reliability and validity using self-reported menstrual cycle start dates. Using cycle counting methods to establish menstrual cycle day (and categorical cycle phase) is an inexpensive and powerful way to understand or covary the effects of the cycle on a repeated outcome of interest in a longitudinal study. For cross-sectional studies, researchers may control for cycle phase or recruit cycling individuals to participate at the same cycle phase; power may be maximized if cycle phase is chosen where the potential symptoms of interest is most pronounced. In order to generate both cycle day and cycle phase variables for use in models, three dates are needed: the date of the observation, the date of the prior menses onset, and the date of the subsequent menses onset. Backward-counting from the day before menses onset (day −1) to day −15 is recommended for delineating the luteal phase and its sub-phases; forward-counting from the day of menses onset (day 1) to day 10 is recommended for delineating the follicular phase. This results in a “cycle day” variable that can be used to graph the impact of the entire cycle on the repeated outcome of interest. For more information about the many options for coding menstrual cycle phases from this cycle day variable in order to test hypotheses about the impact of cycle phases on an outcome of interest, see a recent methodological paper on this topic [71].

Clinical Interventions

Given the prevalence of PME in mood disorders and the emerging evidence for PME of BPD symptoms, it is reasonable to routinely screen all naturally-cycling patients for PME or PMDD. Evidence-based treatment of PMDD has been reviewed extensively elsewhere [72, 73].

While no study to date has attempted pharmacological intervention to address cyclical BPD symptom exacerbation, selective-serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) administered either continuously or intermittently during following ovulation until menstruation have been demonstrated to reduce similar cycle effects especially on irritability in PMDD [35]. RCTs examining efficacy of these medications in reducing high arousal symptoms in the mid-to-late luteal phase among individuals with BPD are warranted. In addition, there is preliminary evidence that stabilization of perimenstrual hormones (prevention of withdrawal) reduces PME of many low-arousal symptoms in a transdiagnostic sample of women with suicidal ideation [47]. Therefore, it should also be a high priority to conduct experiments that replicate, extend, and refine such treatment models in order to understand and treat PME of these BPD symptoms.

Although certain oral contraceptives have demonstrated benefit relative to placebo for PMDD [74], the same oral contraceptives have been found to be ineffective as an adjunct to SSRI for women with PME of depression [75], and have been found to acutely increase symptoms among women high BPD features [33]; therefore, studies are needed to understand the risks vs. benefits of hormonal contraception in BPD, and to confirm a lack of psychiatric benefit in this population. In PMDD, the final lines of treatment involve suppression of ovarian function using GnRH agonist (with stable addback; [76]) or oophorectomy, both of which are effective in ending cycling and cyclical symptoms [77, 78]. Clinical trials are needed to determine whether such treatments are appropriate in severe cases of PME in BPD.

In addition, psychosocial interventions, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), may have utility for individuals with PME but are understudied. A meta-analysis based on the limited work in this area suggests that CBT is currently only evidence-based for reducing impairment—and not symptom severity—in PMDD [79], but CBT has not been examined specifically as a treatment for PME. Nevertheless, given the substantial interpersonal impairment observed in many with PMDD and PME [25], reduction of impairment may be a worthwhile target for psychotherapy, particularly in conjunction with medical management of symptoms. Existing evidence-based interventions for BPD, such dialectical behavior therapy [80] that instruct patients in emotion regulation skills may be particularly promising for lessening the impact of PME, given findings that trait-level emotion regulation deficits are linked to more severe effects of the cycle on symptoms [32].

Conclusions

These findings suggest the importance of considering effects of the menstrual cycle—and ovarian hormones across the lifespan—when conducting research and practicing clinical work with individuals with BPD. Ovarian hormone effects on symptom expression may be common [37], and individuals may be unaware of these hormone-related changes in their symptoms. Further research is needed to clarify effects of cyclical changes in ovarian hormones on BPD symptom expression, given that work to date suggests the potential for large effects through multiple mechanisms. Additionally, very little is currently known about how reproductive hormone changes across the lifespan may confer risk, with the potential for puberty, pregnancy, and perimenopause in particular to increase biological vulnerability. Understanding the complex and potentially interactive effects of ovarian hormones on BPD symptoms is also important in order to provide more informed guidance to patients for decisions about hormonal birth control methods and, for transgender individuals, hormone replacement therapy.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health (K23MH112889, R00MH109667) and the Brain & Behavior Research Foundation.

Footnotes

Human and Animal Rights.

All reported studies/experiments with human or animal subjects performed by the authors have been previously published and complied with all applicable ethical standards (including the Helsinki declaration and its amendments, institutional/national research committee standards, and international/national/institutional guidelines).

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Pub. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schiller CE, Johnson SL, Abate AC, Schmidt PJ, & Rubinow DR (2016). Reproductive steroid regulation of mood and behavior. Comprehensive Physiology, 6(3), 1135–1160. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c150014** Comprehensive review of the pathophysiology of reproductive mood disorders.

- 3.Gehlert S, Song IH, Chang C-H, & Hartlage SA (2009). The prevalence of premenstrual dysphoric disorder in a randomly selected group of urban and rural women. Psychological Medicine, 39(1), 129–136. doi: 10.1017/S003329170800322X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schmidt PJ, Nieman LK, Danaceau MA, Adams LF, & Rubinow DR (1998). Differential behavioral effects of gonadal steroids in women with and in those without premenstrual syndrome. The New England Journal of Medicine, 338(4), 209–216. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199801223380401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bloch M (2000). Effects of Gonadal Steroids in Women With a History of Postpartum Depression. American Journal of Psychiatry, 157(6), 924–930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmidt PJ, Ben Dor R, Martinez PE, Guerrieri GM, Harsh VL, Thompson K, … Rubinow DR (2015). Effects of Estradiol Withdrawal on Mood in Women With Past Perimenopausal Depression: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA psychiatry, 72(7), 714–726. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gordon JL, Rubinow DR, Eisenlohr-Moul TA, Xia K, Schmidt PJ, & Girdler SS (2018). Efficacy of Transdermal Estradiol and Micronized Progesterone in the Prevention of Depressive Symptoms in the Menopause Transition: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA psychiatry, 75(2), 149–157. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.3998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gordon JL, Rubinow DR, & Eisenlohr-Moul TA (2015). Estradiol variability, stressful life events, and the emergence of depressive symptomatology during the menopausal transition. Menopause. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kiesner J (2017). The Menstrual Cycle-Response and Developmental Affective-Risk Model: A multilevel and integrative model of influence. Psychological review, 124(2), 215–244. doi: 10.1037/rev0000058* Theory regarding the role of the menstrual cycle in the development of psychopathology during the pubertal transition.

- 10.Stepp SD, Keenan K, Hipwell AE, & Krueger RF (2014). The impact of childhood temperament on the development of borderline personality disorder symptoms over the course of adolescence. Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotion Dysregulation, 1(1), 1–10. doi: 10.1186/2051-6673-1-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ball JS, & Links PS (2009). Borderline personality disorder and childhood trauma: Evidence for a causal relationship. Current Psychiatry Reports, 11(1), 63–68. doi: 10.1007/s11920-009-0010-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crowell SE, Beauchaine TP, & Linehan MM (2009). A biosocial developmental model of borderline personality: Elaborating and extending linehan’s theory. Psychological Bulletin, 135(3), 495–510. doi: 10.1037/a0015616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gollenberg AL, Hediger ML, Mumford SL, Whitcomb BW, Hovey KM, Wactawski-Wende J, & Schisterman EF (2010). Perceived Stress and Severity of Perimenstrual Symptoms: The BioCycle Study. Journal of Women’s Health, 19(5), 959–967. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2009.1717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Namavar Jahromi B, Pakmehr S, & Hagh-Shenas H (2011). Work Stress, Premenstrual Syndrome and Dysphoric Disorder: Are There Any Associations? Iranian Red Crescent Medical Journal, 13(3), 199–202. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eisenlohr-Moul TA, Rubinow DR, Schiller CE, Johnson JL, Leserman J, & Girdler SS (2016). Histories of abuse predict stronger within-person covariation of ovarian steroids and mood symptoms in women with menstrually related mood disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 67, 142–152. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2016.01.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nillni YI, Pineles SL, Patton SC, Rouse MH, Sawyer AT, & Rasmusson AM (2015). Menstrual cycle effects on psychological symptoms in women with PTSD. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 28(1), 1–7. doi: 10.1002/jts.21984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schulte Holthausen B, & Habel U (2018). Sex Differences in Personality Disorders. Current Psychiatry Reports, 20(12), 107. doi: 10.1007/s11920-018-0975-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Skodol AE, & Bender DS (2003). Why are women diagnosed borderline more than men? Psychiatric Quarterly, 74(4), 349–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grant BF, Chou SP, Goldstein RB, Huang B, Stinson FS, Saha TD, … Ruan WJ (2008). Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV borderline personality disorder: results from the Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 69(4), 533–545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Silberschmidt AL, Lee SS, Zanarini MC, & Schulz SC (2015). Gender Differences in Borderline Personality Disorder: Results From a Multinational, Clinical Trial Sample. Journal of personality disorders, 29(6), 828–838. doi: 10.1521/pedi_2014_28_175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Benson KT, Donnellan MB, & Morey LC (2017). Gender-related differential item functioning in DSM-IV/DSM-5-III (alternative model) diagnostic criteria for borderline personality disorder. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 8(1), 87–93. doi: 10.1037/per0000166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoertel N, Peyre H, Wall MM, Limosin F, & Blanco C (2014). Examining sex differences in DSM-IV borderline personality disorder symptom expression using Item Response Theory (IRT). Journal of Psychiatric Research, 59, 213–219. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.08.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sher L, Rutter SB, New AS, Siever LJ, & Hazlett EA (2019). Gender differences and similarities in aggression, suicidal behaviour, and psychiatric comorbidity in borderline personality disorder. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 139(2), 145–153. doi: 10.1111/acps.12981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmidt PJ, Berlin KL, Danaceau MA, Neeren A, Haq NA, Roca CA, & Rubinow DR (2004). The Effects of Pharmacologically Induced Hypogonadism on Mood in HealthyMen. Archives of General Psychiatry, 61(10), 997–1004. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.10.997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pearlstein T, Yonkers KA, Fayyad R, & Gillespie JA (2005). Pretreatment pattern of symptom expression in premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders, 85(3), 275–282. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2004.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Staebler K, Helbing E, Rosenbach C, & Renneberg B (2010). Rejection sensitivity and borderline personality disorder. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 18(4), 275–283. doi: 10.1002/cpp.705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fernandez E, & Johnson SL (2016). Anger in psychological disorders: Prevalence, presentation, etiology and prognostic implications. Clinical Psychology Review, 46, 124–135. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2016.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hartlage S, Brandenburg D, & Kravitz H (2004). Premenstrual Exacerbation of Depressive Disorders In a Community-Based Sample in the United States. Psychosomatic Medicine, 66(5), 698–706. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000138131.92408.b9* Prospective study showing that 60% of women with a chronic depressive disorder experience clinically significant premenstrual exacerbation of symptoms.

- 29.Dias RS, Lafer B, Russo C, Del Debbio A, Nierenberg AA, Sachs GS, & Joffe H (2011). Longitudinal Follow-Up of Bipolar Disorder in Women With Premenstrual Exacerbation: Findings From STEP-BD. American Journal of Psychiatry, 168(4), 386–394. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09121816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peters JR, Upton BT, & Baer RA (2013). Brief report: Relationships between facets of impulsivity and borderline personality features. Journal of Personality Disorders, 27(4), 547–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Links P, Heslegrave R, & van Reekum R (1999). Impulsivity: core aspect of borderline personality disorder. J Personal Disord, 13(1), 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dawson DN, Eisenlohr-Moul TA, Paulson JL, Peters JR, Rubinow DR, & Girdler SS (2018). Emotion-related impulsivity and rumination predict the perimenstrual severity and trajectory of symptoms in women with a menstrually related mood disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74(4), 579–593. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22522* Longitudinal study showing trait level emotion-related impulsivity and rumination predict more severe PME in those with clinically significant PMDD symptoms.

- 33.DeSoto MC, Geary DC, Hoard MK, Sheldon MS, & Cooper L (2003). Estrogen fluctuations, oral contraceptives and borderline personality. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 28(6), 751–766. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4530(02)00068-9** Study finding that women with BPD features experience increases in symptoms when starting oral contraceptives.

- 34.Eisenlohr-Moul TA, DeWall CN, Girdler SS, & Segerstrom SC (2015). Ovarian hormones and borderline personality disorder features: Preliminary evidence for interactive effects of estradiol and progesterone. Biological Psychology, 109, 37–52. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2015.03.016** Longitudinal study showing daily links between E2, P4, and BPD features in an enriched college sample.

- 35.Steiner M, Pearlstein T, Cohen LS, Endicott J, Kornstein SG, Roberts C, … Yonkers K (2006). Expert guidelines for the treatment of severe PMS, PMDD, and comorbidities: the role of SSRIs. Journal of Women’s Health, 15(1), 57–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ziv B, Russ MJ, Moline M, & Hurt S (1995). Menstrual cycle influences on mood and behavior in women with borderline personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders. doi: 10.1521/pedi.1995.9.1.68 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eisenlohr-Moul TA, Schmalenberger KM, Owens SA, Peters JR, Dawson DN, & Girdler SS (2018). Perimenstrual exacerbation of symptoms in borderline personality disorder: evidence from multilevel models and the Carolina Premenstrual Assessment Scoring System. Psychological Medicine, 6, 1–11. doi: 10.1017/S0033291718001253** Longitudinal study showing significant perimenstrual exacerbation of symptoms in an unmedicated sample of women with BPD.

- 38.Schmalenberger KM, Eisenlohr-Moul TA, Surana P, Rubinow DR, & Girdler SS (2017). Predictors of Premenstrual Impairment Among Women Undergoing Prospective Assessment for Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder: A Cycle-Level Analysis. Psychological medicine, 47(9), 1585–1596. doi: 10.1017/S0033291716003524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bixo M, Ekberg K, Poromaa IS, Hirschberg AL, Jonasson AF, Andréen L, … Bäckström T (2017). Treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder with the GABAA receptor modulating steroid antagonist Sepranolone (UC1010)—A randomized controlled trial. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 80, 46–55. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2017.02.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Martinez PE, Rubinow DR, Nieman LK, Koziol DE, Morrow AL, Schiller CE, … Schmidt PJ (2016). 5α-Reductase Inhibition Prevents the Luteal Phase Increase in Plasma Allopregnanolone Levels and Mitigates Symptoms in Women with Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology: Official Publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology, 41(4), 1093–1102. doi: 10.1038/npp.2015.246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eisenlohr-Moul T, Schmalenberger K, Weise C, Kiesner J, Kaiser G, Ditzen B, & Kleinstauber M (n.d.). Are there temporal subtypes of premenstrual dysphoric disorder?: Using group-based trajectory modeling to identify individual differences in symptom change. Psychological Medicine.* Study finding early and late-onset subtypes of PMDD with implications for pathophysiological overlap with BPD.

- 42.Catherine DeSoto M. (2007). Borderline Personality Disorder, Gender, and Serotonin: Does Estrogen Play a Role? In Psychoneuroendocrinology Research Trends (1st ed, pp. 149–160). Hauppage, NY: Nova Science Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saunders K, & Hawton K (2006). Suicidal behaviour and the menstrual cycle. Psychological Medicine, 36(7), 901–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baca-Garcia E, Diaz-Sastre C, Ceverino A, Perez-Rodriguez MM, Navarro-Jimenez R, Lopez-Castroman J, … Oquendo MA (2010). Suicide attempts among women during low estradiol/low progesterone states. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 44(4), 209–214. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2009.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Baca-Garc ‘ıa E, Diaz-Sastre C, Ceverino A, Saiz-Ruiz J, Diaz FJ, & de Leon J (2015). Association between the menses and suicide attempts: a replication study. Psychosomatic Medicine, 65(2), 237–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baca-Garcia E, Diaz-Sastre C, Ceverino A, Saiz-Ruiz J, Diaz FJ, & de Leon J (2003). Association Between the Menses and Suicide Attempts: A Replication Study. Psychosomatic Medicine, 65(2), 237–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Eisenlohr-Moul T, Prinstein M, Rubinow D, Young S, Walsh E, Bowers S, & Girdler S (2018). S104. Ovarian Steroid Withdrawal Underlies Perimenstrual Worsening of Suicidality: Evidence From a Crossover Steroid Stabilization Trial. Biological Psychiatry, 83(9, Supplement), S387. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2018.02.995** Preliminary study showing prevention of perimenstrual exacerbation of suicidality in a transdiagnostic sample using hormone stabilization.

- 48.Baer RA, Peters JR, Eisenlohr-Moul TA, Geiger PJ, & Sauer SE (2012). Emotion-related cognitive processes in borderline personality disorder: A review of the empirical literature. Clinical Psychology Review, 32(5), 359–369. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Peters JR, Geiger PJ, Smart LM, & Baer RA (2014). Shame and borderline personality features: The potential mediating role of anger and anger rumination. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 5(1), 1–9. doi: 10.1037/per0000022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Peters JR, Eisenlohr-Moul TA, Upton BT, Talavera NA, Folsom JJ, & Baer RA (2017). Characteristics of repetitive thought associated with borderline personality features: A multimodal investigation of ruminative content and style. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 39(3), 456–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Owens SA, & Eisenlohr-Moul T (2018). Suicide risk and the menstrual cycle: a review of candidate RDoC mechanisms, 1–11. doi: 10.1007/s11920-018-0962-3* Review exploring potential Research Domain Criterion-consistent mechanisms underlying PME of suicidal behavior.

- 52.Poulin F, & Boivin M (2000). Reactive and proactive aggression: Evidence of a two-factor model. Psychological Assessment, 12(2), 115–122. doi: 10.1037//1040-3590.12.2.115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Peters JR, Owens SA, Schmalenberger KM, & Eisenlohr-Moul TA (2018). Differential Effects of the Menstrual Cycle on Reactive and Proactive Aggression in Borderline Personality Disorder. bioRxiv. doi: 10.1101/452607** Longitudinal study showing ovulatory increases in proactive aggression and PME of reactive aggression in an unmedicated sample with BPD

- 54.Roney JR, & Simmons ZL (2016). Within-cycle fluctuations in progesterone negatively predict changes in both in-pair and extra-pair desire among partnered women. Hormones and Behavior, 81(C), 45–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Roney JR, & Simmons ZL (2013). Hormonal predictors of sexual motivation in natural menstrual cycles. Hormones and Behavior, 63(4), 636–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Klump KL, Keel PK, Culbert KM, & Edler C (2008). Ovarian hormones and binge eating: exploring associations in community samples. Psychological Medicine, 38(12), 1749–1757. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708002997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Klump KL, Keel PK, Racine SE, Burt SA, Neale M, Sisk CL, … Hu JY (2013). The interactive effects of estrogen and progesterone on changes in emotional eating across the menstrual cycle. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 122(1), 131–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Edler C, Lipson SF, & Keel PK (2007). Ovarian hormones and binge eating in bulimia nervosa. Psychological Medicine, 37(1), 131–141. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706008956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Martel MM, Eisenlohr-Moul T, & Roberts B (2017). Interactive effects of ovarian steroid hormones on alcohol use and binge drinking across the menstrual cycle. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 126(8), 1104–1113. doi: 10.1037/abn0000304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Joyce KM, Hudson A, O’Connor RM, Goldstein AL, Ellery M, McGrath DS, … Stewart SH (2019). Retrospective and prospective assessments of gambling-related behaviors across the female menstrual cycle. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 1–11. doi: 10.1556/2006.7.2018.133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Blake KR, Bastian B, O’Dean SM, & Denson TF (2017). High estradiol and low progesterone are associated with high assertiveness in women. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 75, 91–99. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2016.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Becker JB (1990). Direct effect of 17β-estradiol on striatum: Sex differences in dopamine release. Synapse. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Becker JB (1999). Gender differences in dopaminergic function in striatum and nucleus accumbens. Pharmacology, Biochemistry and Behavior. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Korol DL, Malin EL, Borden KA, Busby RA, & Couper-Leo J (2004). Shifts in preferred learning strategy across the estrous cycle in female rats. Hormones and Behavior, 45(5), 330–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Windels F, & Kiyatkin EA (2003). Modulatory action of acetylcholine on striatal neurons: microiontophoretic study in awake, unrestrained rats. European Journal of Neuroscience, 17(3), 613–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dreher J-C, Schmidt PJ, Kohn P, Furman D, Rubinow D, & Berman KF (2007). Menstrual cycle phase modulates reward-related neural function in women. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104(7), 2465–2470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dreher JC (2015). Neuroimaging Evidences of Gonadal Steroid Hormone Influences on Reward Processing and Social Decision-Making in Humans In Brain Mapping (pp. 1011–1018). Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Roberts B, Eisenlohr-Moul T, & Martel MM (2018). Reproductive steroids and ADHD symptoms across the menstrual cycle. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 88, 105–114. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2017.11.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Eisenlohr-Moul TA, Girdler SS, Schmalenberger KM, Dawson DN, Surana P, Johnson JL, & Rubinow DR (2017). Toward the Reliable Diagnosis of DSM-5 Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder: The Carolina Premenstrual Assessment Scoring System (C-PASS). The American journal of psychiatry, 174(1), 51–59. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.15121510** A standardized method for utilizing daily ratings to assess clinically significant effects of the menstrual cycle of symptoms for research and/or clinical purposes (includes tracking sheets and excel and SAS macros).

- 70.Endicott J, Nee J, & Harrison W (2006). Daily Record of Severity of Problems (DRSP): reliability and validity. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 9(1), 41–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schmalenberger KM, & Eisenlohr-Moul T (2019). Operationalizing menstrual cycle phase: Standardized approaches for hypothesis testing. BiorXiv.* Methodological guide for researchers on multiple methods of assessing the menstrual cycle.

- 72.Eisenlohr-Moul T (n.d.). Premenstrual Disorders: A Primer and Research Agenda for Psychologists. The Clinical Psychologist, 5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Casper RF, & Yonkers KA (2019). Treatment of premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder. UpToDate, Inc; Retrieved from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/treatment-of-premenstrual-syndrome-and-premenstrual-dysphoric-disorder [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lopez LM, Kaptein AA, & Helmerhorst FM (2012). Oral contraceptives containing drospirenone for premenstrual syndrome. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (2), CD006586. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006586.pub4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Peters W, Freeman MP, Kim S, Cohen LS, & Joffe H (2017). Treatment of Premenstrual Breakthrough of Depression With Adjunctive Oral Contraceptive Pills Compared With Placebo. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 37(5), 609–614. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0000000000000761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Schmidt PJ, Martinez PE, Nieman LK, Koziol DE, Thompson KD, Schenkel L, … Rubinow DR (2017). Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder Symptoms Following Ovarian Suppression: Triggered by Change in Ovarian Steroid Levels But Not Continuous Stable Levels. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 174(10), 980–989. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.16101113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wyatt KM, Dimmock PW, Ismail KMK, Jones PW, & O’Brien PMS (2004). The effectiveness of GnRHa with and without “add-back” therapy in treating premenstrual syndrome: a meta analysis. BJOG: an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology, 111(6), 585–593. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00135.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cronje WH (2004). Hysterectomy and bilateral oophorectomy for severe premenstrual syndrome. Human Reproduction, 19(9), 2152–2155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kleinstäuber M, Witthöft M, & Hiller W (2012). Cognitive-Behavioral and Pharmacological Interventions for Premenstrual Syndrome or Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 19(3), 308–319. doi: 10.1007/s10880-012-9299-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Linehan MM (2014). DBT® Skills Training Manual, Second Edition Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]