Publisher Summary

This chapter provides an updated view of the host factors that are, at present, believed to participate in replication/transcription of RNA viruses. One of the major hurdles faced when attempting to identify host factors specifically involved in viral RNA replication/transcription is how to discriminate these factors from those involved in translation. Several of the host factors shown to affect viral RNA synthesis are factors known to be involved in protein synthesis, for example, translation factors. In addition, some of the factors identified to date appear to influence viral RNA amplification as well as viral protein synthesis, and translation and replication are frequently tightly associated. Several specific host factors actively participating in viral RNA transcription/replication have been identified and the regions of host protein/replicase or host protein/viral RNA interaction have been determined. The chapter centers exclusively on those factors that appear functionally important for viral amplification. It presents a list of the viruses for which a specific host factor associates with the polymerase, affecting viral genome amplification. It also indicates the usually accepted cell function of the factor and the viral polymerase or polymerase subunit to which the host factor binds.

I. Introduction

As obligatory intracellular parasites, viruses depend on their host for all steps of their reproduction, starting from uptake by the cell to the final encapsidation of progeny virions and exit from the cell, as well as their spread within the host. Thus, host factors can be expected to participate at most—if not all—levels of virus reproduction.

The present review aims at providing an updated view of the host factors presently believed to participate in replication/transcription of RNA viruses. However, it does not deal with viruses that resort to reverse transcription, nor does it discuss the many protein‐modifying enzymes such as phosphorylating enzymes whose indirect participation in viral genome amplification is undeniable. The reader may wish to turn to various other reviews dealing with certain aspects of genome amplification of RNA viruses for complementary information (Ahlquist 2003, Buck 1996, De 1997, Lai 1998).

Determining what host factors are required for viral protein synthesis has been rather straightforward since viruses rely entirely on the host protein synthesizing machinery to produce their own proteins (Ehrenfeld, 1996), although in certain cases they recruit additional cell proteins not normally involved in translation regulation. On the other hand, searching for host factors involved in transcription and replication of RNA viruses has proven to be much trickier. Originally, the prevailing seemingly simple view of virus genome replication was modeled on the replication of RNA phages such as Qβ (Klovins 1999, Schuppli 2000). Yet it soon became apparent that the situation is far more complex for eukaryotic RNA viruses than for RNA phages.

Multiplication of the genome of most RNA viruses takes place in the cytoplasm. However, influenza virus (Orthomyxoviridae) (Wang et al., 1997) and Borna disease virus (Paramyxoviridae) (Pyper et al., 1998) replicate in the nucleus. An interesting consequence of this nuclear localization is that transcription in these viruses can be accompanied by splicing, a process requiring the host's splicing machinery (Lamb 1991, Tomonaga 2002). In addition, an increasing number of RNA viruses require the nucleus in certain steps of their life cycle (Hiscox, 2003). Arenaviruses cannot complete their replication cycle in cells enucleated soon after infection (Borden et al., 1998). On the other hand, certain (+) as well as (−) strand RNA viruses grow in enucleate cells, virus yield being related to the length of the virus growth cycle (Follett et al., 1975). Several viruses target some of their proteins to the nucleus (Hiscox 2003, Urcuqui‐Inchima 2001), whereas others such as hepatitis C virus (HCV; Flaviviridae) code for proteins that contain nuclear localization signals but do not seem to enter the nucleus (Song et al., 2000). Finally, infection by members of the Picornaviridae, such as poliovirus and coxsackievirus, and by vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV; Rhabdoviridae) (Belov 2000, Gustin 2001) triggers relocation of certain nuclear proteins to the cytoplasm, suggesting that these proteins probably participate in the life cycle of the virus (Hiscox, 2003).

For viruses that produce subgenomic (sg) RNAs, a distinction must be made between two mechanisms, replication of the entire genome and transcription, which usually entails amplification of only certain regions of the genome to yield the sg mRNAs. Since sgRNAs are generally 3′ coterminal, an internally located open reading frame (ORF) in the genomic (g) RNA can become 5′ proximal in the sgRNA, a more favorable situation for the eukaryotic translation apparatus. To date, most of the information available concerning the role of host factors in viral RNA amplification deals with replication, while information concerning host factors and transcription is less abundant except for (−) strand RNA viruses and for viruses of the Coronaviridae, Arteriviridae, and Closteroviridae families (Miller and Koev, 2000).

All RNA viruses contain within their genome the information for the synthesis of an RNA‐dependent RNA polymerase that shall be referred to as the RdRp or polymerase. The viral polymerase and other viral proteins as well as host factors participate in RNA transcription and replication. Yet, how the switch occurs between transcription and replication remains largely enigmatic. During replication, the RNA strand complementary to the genome strand is produced in far lower amounts than the newly synthesized genome strands. How this imbalance is regulated and what factors may be involved in this bias is also far from clear. Nevertheless, some results have appeared suggesting that certain host factors participate in synthesis of one but not of the other strand.

The sequence of events that leads to virus amplification depends on whether the viral RNA entering the cell is of (+) or of (−) polarity.

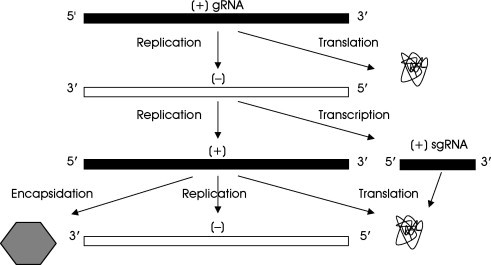

The incoming genome of many (+) strand RNA viruses (Fig. 1 ) serves as mRNA for virus protein synthesis including the RdRp, and is then replicated yielding the complementary (−) RNA strand. In many virus groups, the (−) strand serves as a template to transcribe the sgRNAs that will serve as mRNAs (Miller and Koev, 2000). The (−) strand is also replicated, producing nascent full‐length (+) strands; these are used as mRNA for protein synthesis, as a template for further (−) strand synthesis, and ultimately as a genome to be encapsidated, yielding progeny virus particles.

FIG 1.

Replication/transcription of (+) RNA viruses that produce sgRNAs.

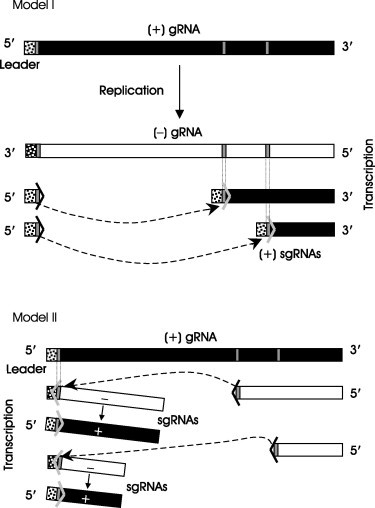

Exceptions to this general scheme exist. Red clover necrotic mosaic tombusvirus (Sit et al., 1998) and citrus tristeza closterovirus (Gowda et al., 2001) generate (−) strand sgRNAs that might function as templates for sg mRNA synthesis. Production of sgRNAs in viruses of the Coronaviridae and Arteriviridae families (both of the order Nidovirales) involves a mechanism similar to splicing known as discontinuous sgRNA synthesis: the transcripts are both 3′ and 5′ coterminal (Fig. 2 ). In this strategy, synthesis of a sgRNA proceeds on a template. The initiated sgRNA, together with the polymerase, then switches from its position to another complementary region called transcription‐regulating sequence (TRS) on the template to which it can base‐pair and resume synthesis. The step at which the nascent RNA chain is transferred from one region of the template to another remains controversial—it could occur during (+) or (−) strand synthesis. The recent demonstration of the presence of (−) sg strands favors the latter possibility (Pasternak 2001, Sawicki 2001). TRSs present in the 3′ end of the leader and at the 5′ end of the sgRNA body regions in the gRNA could allow the nascent RNA chain to be transferred to the leader TRS by TRS‐TRS (sense‐antisense) base‐pairing, or conversely could allow the RNA chain in the leader to be transferred to the sgRNA.

FIG 2.

Two possible models for the synthesis of sgRNAs by the discontinuous transcription strategy used by the Nidovirales (Coronaviridae and Arteriviridae). Model I, during (+) strand synthesis (leader‐primed transcription); Model II, during (−) strand synthesis (recombination during (−) RNA strand synthesis). Thin vertical grey bars, transcription‐regulating sequences (TRSs) which determine the stop and start points during discontinuous transcription. The Leader is composed of the 5′‐positioned nucleotides (stippled box) and the TRS in the (+) RNA strand. (Adapted with permission from Pasternak et al., 2001.)

The scheme for (−) strand RNA viruses is different from that of (+) strand RNA viruses because the incoming RNA cannot serve as a template for protein synthesis. Consequently, all viruses with a (−) strand RNA genome encapsidate their polymerase complex, including host factors. The genome tightly bound to the nucleocapsid protein as a ribouncleoprotein (RNP) with its associated polymerase (De and Banerjee, 1997) is either replicated into complementary (+) strands, or transcribed to produce sg mRNAs. The mechanism of transcription depends on whether the virus contains a nonsegmented or a segmented genome.

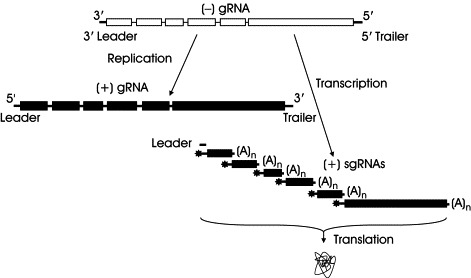

In nonsegmented (i.e., monopartite) (−) RNA viruses (order: Mononegavirales), such as the Paramyxoviridae and Rhabdoviridae, the 3′ and the 5′ termini of the (−) sense gRNA are known as the 3′ leader promoter and 5′ trailer region, respectively (Fig. 3 ). The 3′ region of the complementary (+) sense RNA or antigenome, known as the trailer, directs synthesis of the gRNA. In transcription, synthesis of complementary (+) sgRNAs begins at the 3′ end (3′ leader) of the incoming (−) strand genome producing a short leader RNA, followed by monocistronic capped and poly(A)‐tailed mRNAs by sequential transcription. The 5′ trailer region of the genome and the intercistronic regions separating the ORFs are not transcribed (Kolakofsky et al., 2004).

FIG 3.

Strategy of replication/transcription used by nonsegmented (−) RNA viruses. Asterisk, cap structure; 3′ Leader, 3′ leader promoter; 5′ Trailer, 5′ trailer region.

Transcription of segmented (−) strand RNA viruses such as the Orthomyxoviridae, Arenaviridae, Bunyaviridae, and Tenuiviruses requires a primer to initiate synthesis of the mRNAs. This is achieved by cap‐snatching in which the replicase complex, or a protein thereof, binds to the 5′ region of cell mRNAs, cleaves off the cap together with generally 7–15 nucleotides from the 5′ end of the cell mRNA, and uses this fragment as a primer to initiate synthesis of the viral mRNAs (Bouloy 1978, Nguyen 2003). Hence, the viral mRNAs are capped and have cell‐derived nucleotides at their 5′ end; they also contain a poly(A) tail at their 3′ end. Replication, on the other hand, is not primer‐dependent, and the RNAs complementary to the genome are devoid of cap and of poly(A) tail.

II. How to Study Host Factors Specifically Involved in Viral RNA Transcription/Replication

Host factors participate in viral genome amplification based on their specific binding to or copurification with replicase subunits, their binding to specific regions of the viral RNA, their influence on replication/transcription, the occurrence of host mutations that influence virus multiplication, and the reduced effect on replication/transcription observed in the presence of small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) directed against specific candidate host proteins.

The unambiguous identification of host proteins that persistently copurify with viral polymerases during multiple purification steps has been fraught with difficulties, in spite of the fact that certain cell proteins bind with high affinity to the purified polymerase, or that cell proteins are often encapsidated together with the polymerase as in the case of the (−) strand RNA viruses. Similar difficulties have been encountered in searching for specific host factors that interact with the viral genome. These difficulties are exacerbated by the fact that it is often difficult to distinguish between factors that directly affect RNA replication/transcription from those that have an indirect effect on viral RNA synthesis, such as by interacting with host factors that in turn are directly involved in RNA amplification. Gel‐shift mobility assays, UV‐crosslinking, coimmunoprecipitation, and the yeast two‐ or three‐hybrid systems have served to search for interactions between host factors and the viral polymerase and/or the viral RNA. Yet the relevance of such interactions remains equivocal in the absence of functional RNA amplification assays. In many cases, particular caution must therefore surround published data, and further experiments are needed to determine whether copurification and/or interaction with viral proteins or RNA is fortuitous or has a functional significance. Technologies such as the systematic search for host genes became involved in virus RNA amplification using an ordered genome‐wide set of deletion mutants (Kushner et al., 2003) and RNA interference (Ahlquist 2002, Isken 2003, Lan 2003, Li 2002a), are beginning to provide promising results that nevertheless still require further verification.

One of the major hurdles faced when attempting to identify host factors specifically involved in viral RNA replication/transcription is how to discriminate these factors from those involved in translation. As has become apparent, several of the host factors shown to affect viral RNA synthesis are factors known to be involved in protein synthesis such as, for example, translation factors. In addition, some of the factors identified to date appear to influence viral RNA amplification as well as viral protein synthesis, and translation and replication are frequently tightly associated. This situation adds a further level of complication to the identification of host factors involved in a specific viral function. It will hopefully become possible to overcome this problem by examining the effect of a given host factor on the replicase and its activity, and in parallel its effect on translation in vitro and in vivo. Such experiments have been undertaken (Choi et al., 2002) and have already provided interesting information concerning transcription in a coronavirus.

On the other hand, to identify host factors that specifically favor synthesis of RNA strands complementary to the genome but not synthesis of further genome strands, one can take advantage of the observation that a few additional nontemplated nucleotides positioned at the 5′ end of a viral genomic RNA can still allow synthesis of the complementary strand, but can hinder subsequent synthesis of new genome strands. Experiments based on this approach have been used to distinguish certain aspects of (−) from (+) strand synthesis of poliovirus (Murray and Barton, 2003).

In spite of all the pitfalls outlined previously, several specific host factors actively participating in viral RNA transcription/replication have been identified and the regions of host protein/replicase or host protein/viral RNA interaction determined. The present review centers exclusively on those factors that appear functionally important for viral amplification.

III. Interaction with the Replicase Complex

Table I presents a list of the viruses for which a specific host factor associates with the polymerase, affecting viral genome amplification. It also indicates the usually accepted cell function of the factor and the viral polymerase or polymerase subunit to which the host factor binds.

TABLE I.

Host Factors Associating with Viral RNA Replicase Complexes

| Virus | Family/Genus (genome polarity) | Host factor | Function in host | Virus target | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qβ | Leviviridae (+) | EF‐Tu, EF‐Ts, S1 | Translation | Replicase | Blumenthal and Carmichael (1979) |

| HF | Translation regulation | Klovins 1999, Schuppli 2000 | |||

| BMV | Bromoviridae (+) | eIF3 | Translation | 2a | Quadt et al. (1993) |

| TMV | Tobamovirus (+) | eIF3 | Translation | 126 kDa, 183 kDa | Osman and Buck (1997) |

| TEV | Potyviridae (+) | eIF4E | Translation | NIa | Schaad et al. (2000) |

| RV | Togaviridae (+) | Rb | Cell growth | NSP90 | Atreya et al. (1998) |

| HCV | Flaviviridae (+) | α‐actinin | Transport | NS5B | Lan et al. (2003) |

| hPLIC1 | Protein degradation | Gao et al. (2003) | |||

| p68 | RNA metabolism | Goh et al. (2004) | |||

| VSV | Rhabdoviridae (−) | EF1α, β, γ | Translation | L | Das et al. (1998) |

| MV | Paramyxoviridae (−) | tubulin | Transport | L | Moyer et al. (1990) |

| CDV | Paramyxoviridae (−) | hsp72 | Protein metabolism | NC | Oglesbee et al. (1996) |

| IV | Orthomyxoviridae (−) | NPI‐5 | Splicing | NP | Momose et al. (2001) |

BMV, brome mosaic virus; TMV, tobacco mosaic virus; TEV, tobacco etch virus; RV, rubella virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; VSV, vesicular stomatitis virus; MV, measles virus; CDV, canine distemper virus; IV, influenza virus; EF, elongation factor; HF, host factor; eIF, eukaryotic initiation factor; Rb, retinoblastoma; hPLIC1, human homolog 1 of protein linking integrin‐associated protein and cytoskeleton; hsp, heat shock protein; NPI, nucleoprotein interactor. Protein membrane components interacting with virus replicases are presented in Table IV.

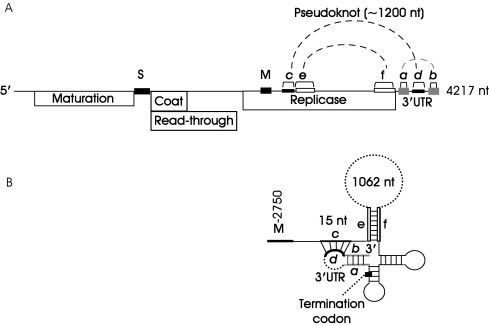

The replication complex of RNA phages, such as Qβ is composed of four subunits: the virus‐encoded RNA polymerase, and three host factors, the protein elongation factors Tu (EF‐Tu) and Ts (EF‐Ts), and the ribosomal protein S1 (Table I). Another host factor, designated HF, is also required for (−) strand synthesis from the (+) strand RNA template. In the generally accepted scenario, the polymerase provides the polymerizing activity, whereas S1 allows the enzyme complex to bind to two (S and M) internal sites in the viral genome (Table II ; Fig. 4 ). The long‐standing observation that the polymerase subunit binds to internal sites on the viral genome remained a paradox for several decades. Indeed, if the enzyme is to faithfully replicate the template, it must somehow also lie close to the 3′ end of the template. It has now been established that this is achieved at least in part by elaborate secondary structures in the viral RNA (Fig. 4) that bring the 3′ end of the viral RNA in close proximity to the internal sites where the polymerase is positioned (Klovins and van Duin, 1999), facilitating this interaction.

TABLE II.

Host Factors Associating with Viral RNAs

| Virus | Family (genome polarity) | Viral genome target region (strand polarity) | Host factor | Function in host | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qβ | Leviviridae (+) | Internal (+) | S1 | Translation | Blumenthal 1979, Klovins 1999, Schuppli 2000 |

| Internal (+), 3′(+) | HF | Translation regulation | |||

| PV | Picornaviridae (+) | 5′(+) | PCBP | mRNA stability | Gamarnik 1997, Parsley 1997, Walter 2002 |

| 3′(+) | PABP | mRNA stability | Herold and Andino (2001) | ||

| Nucleolin | rRNA processing | Waggoner and Sarnow (1998) | |||

| MHV | Coronaviridae (+) | 3′(−), IG (−) | hnRNP A1 | Splicing | Li 1997, Shi 2000, Shen 2001, Shi 2003 |

| 5′(+), 5′(−) | PTB | Splicing | Huang 1999, Choi 2002 | ||

| 3′(+) | Mitochondrial aconitase | Citric acid cycle | Nanda and Leibowitz (2001) | ||

| WNV | Flaviviridae (+) | 3′(−) | TIA‐1, TIAR | Translation, apoptosis | Li et al. (2002b) |

| BVDV | Flaviviridae (+) | 5′ UTR, 3′ UTR | NF90/NFAR‐1, NF45, RHA | Transcription/translation regulation | Isken et al. (2003) |

| HPIV‐3 | Paramyxoviridae (−) | Leader RNA (−), Leader RNA (+) | GAPDH | Glycolysis | De et al. (1996) |

PV, poliovirus; MHV, mouse hepatitis virus; WNV, West Nile virus; BVDV, bovine viral diarrhea virus; HPIV‐3, human parainfluenza virus‐3; IG (−), intergenic region in (−) RNA; UTR, untranslated region; Leader RNA (−), 3’ end of (−) RNA; Leader RNA (+), 5’ end of (+) RNA; HF, host factor; PCBP, poly(C)‐binding protein; PABP, poly(A)‐binding protein; hnRNP A1, heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1; PTB, polypyrimidine tract‐binding protein; TIA‐1, T‐cell‐activated intracellular antigen; TIAR, TIA‐1‐related; RHA, RNA helicase A; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde‐3‐phosphate dehydrogenase.

FIG 4.

(A) Genetic map and genome organization of Qβ RNA. Highlighted are the S and M sites on the genome to which the enzyme complex binds, as well as various RNA‐RNA interaction sites within the 3′ half of the genome. (B) Enlarged schematic representation of RNA–RNA interactions. A pseudoknot is formed between regions c and d. Not to scale. (Adapted with permission from Klovins and van Duin, 1999.)

The eukaryotic initiation factor 3 (eIF3) stimulates binding of the mRNA to the 40S ribosomal subunit and stabilizes the interaction between the 40S and initiator Met‐tRNA. It has been shown that the 2a polymerase‐like protein involved in brome mosaic bromovirus (BMV) amplification interacts with a 41‐kDa protein, one of the 10 subunits of eIF3 or of a closely related protein (Quadt et al., 1993) thereby greatly stimulating (−) strand RNA synthesis in vitro. Similarly, the membrane‐bound replication complex of tobacco mosaic tobamovirus (TMV) contains a subunit of eIF3, the 56 kDa component which is the RNA‐binding subunit of the wheat germ eIF3. Hence, the host components of the two viral polymerases correspond to different subunits of eIF3. Antibodies against the 56 kDa subunit inhibit TMV RNA synthesis in vitro (Osman and Buck, 1997).

NIa forms part of the replication complex of Potyviruses, such as tobacco etch potyvirus (TEV; Schaad et al., 2000), by providing the viral genome‐linked protein (VPg) and proteolytic functions. It interacts with the protein initiation factor eIF4E, a factor that binds to the cap structure and facilitates recruitment of the mRNA as well as other factors on the 40S ribosomal subunit. To investigate this interaction further, full‐length TEV transcripts were produced harboring different mutated versions of the eIF4E coding sequence. After transfection of protoplasts with these in vitro‐transcribed constructs, cells containing the mutated eIF4E transcripts accumulated far lower amounts of virus than those harboring the wild‐type eIF4E transcript.

The tumor suppressor retinoblastoma protein (Rb) is a nuclear phosphoprotein that binds to many proteins and plays a fundamental role in suppression of various neoplasms. Its capacity to suppress cell proliferation is caused mainly by binding and inhibiting the transcription factor E2F (Taya, 1997). The NSP90 protein, the putative RdRp of rubella virus (RV; Togaviridae), binds to the Rb in vitro and in vivo. This interaction requires the presence of at least some Rb in the cytoplasm where amplification of RV is believed to be confined (Forng and Atreya, 1999). Rb facilitates RV replication, since in null‐mutant (Rb−/−) mouse embryonic fibroblasts, the level of RV replication is lower than in wild‐type (Rb+/+) cells (Atreya et al., 1998). NSP90 contains the Rb‐binding motif LXCXE. In mutant viruses containing a C to R mutation in this motif, replication is reduced to less than 0.5% of the wild‐type virus, and deletion of the motif is lethal (Forng and Atreya, 1999), clearly demonstrating the requirement of the Rb protein for efficient RV replication.

Interaction of the HCV RNA polymerase (NS5B) with α‐actinin, a member of a superfamily of actin cross‐linking proteins, was demonstrated using various in vitro techniques. It was confirmed by reducing the expression of α‐actinin by RNA interference in the HCV replicon system, resulting in decrease of HCV RNA levels (Lan et al., 2003). Likewise, a ubiquitin‐like protein hPLIC1 (the human homolog 1 of the protein linking integrin‐associated protein and cytoskeleton) also interacts with NS5B, and its overexpression in the replicon system reduces the levels of NS5B and of replicon RNA probably by promoting NS5B degradation via a ubiquitin‐dependent pathway (Gao et al., 2003). Using the two‐hybrid system to screen a human cDNA library with NS5B as bait, it was demonstrated that the cellular RNA helicase p68 is another protein that interacts with the HCV polymerase (Goh et al., 2004). The C‐terminal part of NS5B is responsible for this interaction. The p68 helicase is redistributed from the nucleus to the cytoplasm in NS5B expressing cells.

The use of two different cell systems to study the effect of p68 on replication led to opposite results when the level of p68 was reduced using an siRNA: in an HCV replicon‐bearing cell line, no effect on HCV replication was observed, while in cells transiently transfected with a full‐length HCV construct, synthesis of the negative strand was inhibited. Overexpression of NS5B and its C‐terminally truncated mutant in the transiently transfected cell line also inhibited negative strand synthesis, probably due to sequestration of p68. The helicase activity of p68 does not seem to be required for replication, suggesting that it acts as a transcription factor rather than as a helicase (Goh et al., 2004).

The RdRp or L protein of VSV has been overexpressed in recombinant baculovirus‐infected cells. The purified, transcriptionally active fraction contains the subunits α, β, and γ of EF‐1. The α subunit binds to the RdRp with the highest affinity yielding a partially active enzyme, and addition of the β and γ subunits significantly enhances enzyme activity. All three subunits are packaged with the L protein in the virions (Das et al., 1998).

Tubulin binds to the RdRp (L protein) of measles virus (MV; Paramyxoviridae) and may be part of the polymerase complex of this virus, as suggested by its coimmunoprecipitation with the RdRp from extracts of MV‐infected cells (Moyer et al., 1990). It is required for efficient viral RNA replication and transcription, since anti‐tubulin antibodies inhibit viral RNA synthesis and addition of purified tubulin stimulates MV RNA synthesis in vitro.

Experiments performed with canine distemper virus (CDV; Paramyxoviridae) (De 1997, Lai 1998) strongly suggest that heat shock proteins may also be required for optimal transcription when closely associated with the nucleocapsids (NCs) of this virus. Indeed, when the CDV NCs from non‐heat‐shocked and heat‐shocked cells are compared, an increase in—and/or accumulation of—viral transcripts is observed in the heat‐shocked cells. The heat‐shock protein hsp72 seems to directly enhance viral RNA transcription in vitro (Oglesbee et al., 1996).

Three proteins, PB1, PB2, and PA compose the polymerase of influenza A virus. PB2 cleaves 5′ oligonucleotides containing the cap structure from cellular mRNAs in the cap‐snatching scenario. PB1 is the catalytic subunit for viral RNA synthesis and uses the capped oligonucleotides as primers for transcription. The function of the phosphoprotein PA remains unclear. In addition, the nucleoprotein NP is required for synthesis of full‐length RNA (Momose et al., 2001), and as such it forms part of the replicase complex. Various proteins have been shown to interact with the NP. Among them is the nucleoprotein interactor 5 (NPI‐5, also known as RAF‐2p48, BAT1 or UAP56), a cellular splicing factor (Momose et al., 2001). It interacts with free NP, but not with NP‐RNA complexes, and stimulates synthesis of the viral RNA. Its interaction with NP is disrupted by the addition of large amounts of viral RNA that bind to NP, suggesting that NPI‐5 may facilitate loading of NP on the RNA, thus acting as a chaperone. In influenza virus‐infected cells, NPI‐5 disappears from spliceosomes, where it is concentrated in uninfected cells. Its relocalization is similar to that of another splicing‐related host protein, the NS1‐binding protein (NS1‐BP), which depends on the presence and distribution of the viral nonstructural protein NS1 (Wolff et al., 1998). The same distribution pattern of the three proteins (NPI‐5, NS1‐BP, and NS1) in infected cells suggests that NPI‐5 may indirectly contribute to shutoff of host protein synthesis in these cells, due to inhibition of splicing and 3′‐terminal processing of pre‐mRNAs by the NS1 protein (Momose 2001, Wolff 1998).

IV. Binding of Host Proteins to the Viral RNA Genome

The search for host factors involved in viral RNA amplification has also focused on cellular proteins that specifically bind to the 3′ or 5′ untranslated regions (UTRs) of either the (−) or (+) RNA strand, as well as to intergenic regions in the Nidovirales and Mononegavirales.

Several host factors that bind to specific regions of viral RNAs have been identified. All those whose implication in viral RNA replication has also been clearly demonstrated are presented in Table II.

The poly(C)‐binding protein (designated PCBP, hnRNP E or αCP) isoforms 1 and 2 regulate the stability and expression of several cellular mRNAs (Herold 2001, Walter 2002). They are involved in poliovirus RNA translation and replication (Gamarnik and Andino, 1998). When bound to the internal ribosome entry site (IRES) of poliovirus RNA, PCBP probably enhances translation (Blyn et al., 1997), but it also regulates RNA synthesis since its binding to the disrupted stem‐loop IV of the IRES negatively affects replication (Gamarnik and Andino, 2000). It also binds to the 5′ cloverleaf structure of the poliovirus RNA upstream of the IRES (Gamarnik 1997, Gamarnik 1998, Parsley 1997) to which the poliovirus 3CD polymerase also binds, and where it is essential for initiation of (−) RNA synthesis. Studies have aimed at investigating the functions of the different PCBP isoforms as well as identifying the domains of these factors involved in poliovirus translation and replication using PCBP‐depleted cell extracts. Using this approach, it was shown that PCBP2 rescues both RNA replication and translation initiation, whereas PCBP1 rescues only replication (Walter et al., 2002). PCBP thus seems to be involved in the switch from viral RNA translation to replication that may result from a change in the relative homo‐ and hetero‐dimer concentrations of both isoforms.

The ternary ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex formed between the 5′ cloverleaf structure, 3CD, and PCBP can interact in vitro with the poly(A)‐binding protein PABP bound to the poly(A) tail, thus circularizing the RNA (Herold and Andino, 2001). Such a circularized RNP complex consisting of an RNA–protein–protein–RNA bridge is required to initiate (−) strand RNA synthesis.

Nucleolin is an abundant nucleolar protein. It is highly modified by phosphorylation and methylation, and at times also by ADP‐ribosylation. One of the multiple functions of this RNA‐binding protein is to promote processing of ribosomal RNA in the presence of U3 snoRNP (Hiscox, 2002). Upon poliovirus infection, it relocalizes to the cytoplasm and interacts strongly with the poliovirus 3′ UTR (Waggoner and Sarnow, 1998). Cell‐free extracts depleted of nucleolin produce fewer infectious particles than control extracts at early times after infection. This is overcome at later times for reasons that remain undefined. Ongoing viral gene expression is necessary for relocalization of nucleolin to the cytoplasm and is not the result of inhibition of host protein synthesis, since addition of cycloheximide to uninfected cells does not trigger relocalization of nucleolin.

An interesting example of seemingly contradictory results obtained using different approaches to identify host factors required for viral genome amplification, is the case of the possible role of the heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein (hnRNP) A1 in coronavirus sg mRNA synthesis. hnRNP A1 binds to the pyrimidine tract‐binding protein (PTB) and is believed to be part of a splicing complex involved in alternative RNA splicing (Lai 1998, Miller 2000), although new data indicate that it may act as a splicing silencer as demonstrated for human immunodeficiency virus‐1 (Retroviridae) (Tange et al., 2001). On one hand, by UV‐cross‐linking and immunoprecipitation, it was reported that hnRNP A1 binds to the common TRSs in the mouse hepatitis virus (MHV; Coronaviridae) RNA of the complementary (−) leader and (−) intergenic regions, which conform to the consensus PTB‐binding motif. Hence, hnRNP A1 was proposed to bring together the two elements of the viral RNA involved in transcription (Huang 2001, Li 1997). Moreover, MHV RNA transcription and replication were stimulated by overexpression of hnRNP A1, and inhibited by dominant‐negative mutants of hnRNP A1 (Shi et al., 2000). On the other hand, however, the hnRNP A1‐binding motif found in MHV transcription‐regulating sequences is not conserved in other Nidovirales, and MHV replication and transcription were not affected when a cell line not expressing hnRNP A1 was used (Shen and Masters, 2001). The protein is thus dispensable for MHV replication and transcription. Furthermore, recent results indicate that hnRNP A1‐related proteins can replace hnRNP A1 for MHV RNA synthesis in hnRNP A1‐depleted cells (Shi et al., 2003). Therefore, similar functions may be exerted by closely related proteins, making it difficult to assign conclusive roles to certain cellular proteins in viral genome amplification.

PTB is a member of the hnRNP family of proteins and shuttles between the nucleus and the cytoplasm. It binds to the polypyrimidine tract of the adenovirus major‐late pre‐mRNA, and regulates alternative splicing of certain pre‐mRNAs. Its role in stimulating internal initiation of translation of the genome of certain RNA viruses containing an IRES has attracted considerable attention (Anwar 2000, Hunt 1999, Kaminski 1998). In the cases where it favors internal initiation, this appears to be achieved by maintaining the IRES in the appropriate configuration for efficient translation (Kaminski and Jackson, 1998).

In MHV RNA, PTB binds to a stretch of four UCUAA repeats in the 5′ (+) leader and to the 5′ UTR of the complementary (−) strand. Binding to these sites is required for transcription (Huang and Lai, 1999). To further elucidate the role of PTB in MHV RNA synthesis and discriminate between an effect on transcription and translation, defective interfering (DI) RNAs harboring different reporter genes were transfected into stable cell lines overexpressing full‐length or truncated PTB (Choi et al., 2002). When these overexpressing cell lines were infected with a DI RNA—coding for chloramphenicol acetyl transferase (CAT) preceded by the intergenic region—that had to be transcribed during MHV infection to undergo translation, CAT activity was much lower than in control cell lines, suggesting that PTB overexpression had a dominant‐negative effect on translation and/or transcription. To determine whether PTB was affecting translation or transcription, cell lines overexpressing PTB were transfected with an in vitro transcribed DI RNA containing part of the MHV ORF1a fused to the luciferase gene and flanked by the MHV 5′ and 3′ UTRs. The same level of luciferase activity was obtained in cells overexpressing PTB as in control cells. Likewise, synthesis of a reporter protein in a reticulocyte lysate previously depleted of PTB was the same as in a control undepleted lysate. These last two series of experiments demonstrate that PTB is directly involved in RNA synthesis, not in translation. Moreover, PTB interacts in vivo and in vitro with the viral N protein, an element of the replication complex, supporting the idea that PTB is part of the viral transcription/replication machinery (Choi et al., 2002).

PTB interacts specifically with the IRESs of several picornaviruses enhancing translation. However, as opposed to its proposed function in directly enhancing MHV RNA transcription, PTB probably indirectly participates in poliovirus RNA synthesis. It has been suggested that early in infection, PTB enhances poliovirus translation. However, because the poliovirus translation products accumulate, and because PTB is cleaved by the viral protease 3Cpro and/or 3CDpro, during late stages of infection the concentration of PTB would no longer be sufficient to favor translation, leading to a switch from translation to replication (Back et al., 2002).

Mitochondrial aconitase is involved in the citric acid cycle; it is a posttranscriptional regulator and possesses iron‐regulatory functions (Nanda and Leibowitz, 2001). It is one of several proteins that bind specifically to the MHV 3′ (+) RNA region harboring the poly(A) tail. Early in infection such binding increases production of infectious virus particles as determined by Western blots of the infected murine cell extracts, in particular when the cell cultures are supplemented with iron. Binding of mitochondrial aconitase to the 3′ UTR of the viral genome might increase the stability of the mRNA, thereby favoring translation and the production of virus particles at early times after infection.

The multifunctional TIA‐1 (T‐cell‐activated intracellular antigen) and TIAR (TIA‐1‐related) proteins belong to a family of RNA‐binding proteins and are involved in translation regulation and apoptosis; they have also been identified in mammalian stress granules, where they promote recruitment of untranslated mRNAs during environmental stress (Dember 1996, Kedersha 1999, Li 2002b). One of the host proteins that bind to the West Nile virus (WNV; Flaviviridae) 3′ hairpin in the (−) RNA strand has recently been identified as TIAR (Li et al., 2002b). TIA‐1 also binds to the same region in the viral RNA. Moreover, virus growth is inefficient in TIAR knockout cells, and when such cells are complemented with a vector expressing TIAR, WNV growth is partially restored. Thus, TIAR and possibly also TIA‐1 are functionally important for WNV replication. This has not been shown for Sendai virus (SeV; Paramyxoviridae), although its trailer RNA binds TIAR, and the protein is involved in virus‐induced apoptosis (Iseni et al., 2002).

A group of cellular proteins belonging to a family with diverse functions and containing a common double‐strand (ds) RNA, binding motif (dsRBM) was identified when searching for proteins interacting with the 3′ UTR of the bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV; Flaviviridae) genome. Interaction of the three proteins NF90/NFAR‐1, NF45, and RNA helicase A (RHA), known as the “NFAR” group to both the 3′ and 5′ UTRs, was unambiguously demonstrated (Isken et al., 2003). Mutations of the proteins' interaction sites in the 3′ UTR decreased protein binding and RNA replication (measured as progeny (+) RNA synthesis). Similarly, transfection of cell lines supporting BVDV replication with siRNAs directed against RHA led to 60–85% reduction of viral replication. The data suggest that the NFAR proteins may mediate circularization of the viral RNA leading to a switch from translation to replication. Interestingly, this group of proteins is also believed to be part of the antiviral response of the cell that seems to be subverted by the virus for the purpose of its propagation. The direct involvement of the NFAR proteins in viral replication and not in translation will require confirmation by further experiments.

Glyceraldehyde‐3‐phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) is a key enzyme of glycolysis. It appears as multiple isoforms consistent with its multifunctional nature (Takagi et al., 1996). It interacts with various proteins and with RNAs including the leader RNA (−) and leader RNA (+) of human parainfluenza virus type 3 (HPIV‐3; Paramyxoviridae) (De et al., 1996) and has helix‐destabilizing activity. Specific phosphorylated forms of the protein associate with the viral RNA and inhibit transcription in vitro (Choudhary et al., 2000). Thus, GAPDH is a negative regulator of viral gene expression in this case. Specific, highly phosphorylated forms of GAPDH are encapsidated in the HPIV‐3 virions (Choudhary et al., 2000).

The La autoantigen is a ubiquitous phosphoprotein and an RNA‐binding protein. Although it interacts with the UTRs of several RNA viruses (De Nova‐Ocampo 2002, Duncan 1997, Gutiérrez‐Escolano 2000, Gutiérrez‐Escolano 2003, Lai 1998, Wolin 2002), to date, it has not been shown to have a clear functional effect on viral genome amplification and therefore is not discussed further here.

V. Interaction with Cytoskeletal Proteins

Tubulin and actin activate RNA transcription of members of the Rhabdoviridae and Paramyxoviridae families (Table III ). These cytoskeletal proteins might stabilize the various components of the transcription/replication complexes, or could transport or orient the viral RNAs and the complexes to specific cellular compartments in the appropriate topology.

TABLE III.

Cytoskeletal Proteins Interacting with RNA Viruses

| Virus | Family (genome polarity) | Host factor | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| VSV | Rhabdoviridae (−) | Tubulin | Moyer et al. (1986) |

| MV | Paramyxoviridae (−) | Tubulin | Moyer et al. (1990) |

| SeV | Paramyxoviridae (−) | Tubulin | Moyer et al. (1986) |

| PGK,* enolase | Ogino et al. (2001) | ||

| HPIV‐3 | Paramyxoviridae (−) | Actin | De 1999, Gupta 1998 |

| HRSV | Paramyxoviridae (−) | Actin Profilin | Burke 1998, Ulloa 1998 |

VSV, vesicular stomatitis virus; MV, measles virus; SeV, Sendai virus; HPIV‐3, human parainfluenza virus‐3; HRSV, human respiratory syncytial virus; PGK, phosphoglycerate kinase.

Interaction occurs via tubulin.

Synthesis in vitro of VSV and SeV mRNAs requires tubulin (Moyer et al., 1986). In SeV, tubulin and at least two other cellular proteins, phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK) and enolase, both glycolytic enzymes, are required for transcription. Once associated with the transcription complex, tubulin might recruit PGK and enolase into the complex that would become active for elongation of viral mRNA chains (Ogino et al., 2001). In MV‐infected cell extracts that support transcription and replication, actin stimulates both these reactions in vitro (Moyer et al., 1990).

Actin microfilaments are involved in HPIV‐3 replication and transcription in vivo, and in transcription in vitro (De 1999, Gupta 1998) as judged by the action of cytochalasin D that depolymerizes actin microfilaments and results in inhibition of viral RNA synthesis. Actin is detected in purified human respiratory syncytial virus (HRSV; Paramyxoviridae) (Ulloa et al., 1998); transcription in vitro is stimulated by monomeric actin, as well as by actin microfilaments (Burke et al., 1998). In addition to actin, profilin (an actin‐modulatory protein) is required for optimal transcription of HRSV (Burke et al., 2000).

VI. Host Factors Identified Using the Yeast Model

Among (+) strand RNA viruses, interesting clues have been gathered using BMV, taking advantage of the fact that yeast cells support BMV amplification. Using this approach, several yeast factors have been characterized that stimulate virus amplification (Noueiry and Ahlquist, 2003). Mutations in the small protein Lsm1p involved in mRNA decapping preceding mRNA degradation modulate BMV RNA replication and sg mRNA synthesis in yeast, leading to a selective reduction of RNA3 replication, and hence of sgRNA synthesis (Diez 2000, Noueiry 2003). Mutations in Ydj1p, a chaperone thought to participate in proper polymerase folding to produce an active replication complex, inhibit the formation of such a complex required for (−) RNA strand synthesis (Tomita et al., 2003). Finally, mutations in the Ded1p required for translation initiation (Noueiry et al., 2000) appear to also indirectly decrease BMV RNA replication.

Ded1p was also shown to directly influence replication of the yeast dsRNA L‐A virus (Totiviridae) because its addition to extracts of virus‐infected yeast cells led to stimulation of (−) but not of (+) strand RNA synthesis. However, the mechanism of action of Ded1p remains only partially elucidated, as only interaction of Ded1p with the capsid protein Gag could be clearly demonstrated (Chong et al., 2004).

A systematic search for host factors involved in BMV replication has been performed using 4500 single‐gene yeast deletion mutants transformed with constructs expressing replicase proteins as well as luciferase from a replication template. This led to the identification of 58 and 38 genes whose deletions respectively inhibited and enhanced luciferase expression at least threefold (Kushner et al., 2003). Some of these genes, such as the LSM and SKI genes, had been previously identified as being implicated in viral replication and/or RNA function and turnover. For a selected group of genes, a more detailed analysis was carried out that further supports the direct effect of the gene products on RNA synthesis. Further studies are needed to elucidate more precisely how these newly implicated host factors influence viral replication, and to uncover possible functions of essential yeast genes in BMV RNA replication.

VII. Involvement of Membrane Components

The replication complexes of all (+) strand eukaryotic RNA viruses are associated with intracellular membranes (Lee et al., 2001), and virus infection frequently leads to membrane proliferation or vesiculation. In addition, proliferation of membrane proteins is linked to lipid biosynthesis—both phenomena appear to be important for the amplification of most viral genomes. Thus, it is to be expected that membrane association is important for viral RNA synthesis.

The polymerase of members of the Togaviridae family is active in modified endosomes or lysosomes designated cytoplasmic vacuoles or double‐stranded vesicles (Kääriäinen and Ahola, 2002). In equine arteritis virus (Arteriviridae) (Pedersen 1999, Snijder 2001), the RNA polymerase is found in presumably endoplasmic reticulum– (ER‐) derived double‐membrane structures. RNA synthesis of members of the Flaviviridae family, such as that of WNV, probably occurs in trans‐Golgi membranes (Mackenzie et al., 1999). RNA synthesis of HCV occurs on membranes of the ER or on a membranous matrix designated membranous web (Moradpour et al., 2003) or lipid raft (detergent‐resistant membrane) (Gao et al., 2004). Poliovirus infection leads to the appearance of greatly rearranged vesiculated membranes (Suhy et al., 2000), and poliovirus RNA replication occurs on membranes that contain markers of lysosomes, the Golgi apparatus, and the ER (Egger 2000, Schlegel 1996).

Flock house virus (FHV; Nodaviridae) is an insect virus that multiplies in diverse host cells such as plant, animal, insect, and yeast cells. Using anti‐RdRp antibodies, it was demonstrated that the RdRp is tightly associated with the outer mitochondrial membranes of Drosophila cells, implying that FHV replication occurs on these membranes (Miller et al., 2001). This interaction results from the presence of an N‐proximal sequence in the RdRp that contains a transmembrane domain. When this domain was replaced by a yeast or HCV ER‐targeting sequence, the RdRp chimeras were redirected to the ER membranes in yeast cells, and viral genomic and subgenomic RNA synthesis was enhanced considerably (Miller et al., 2003).

RNA synthesis of plant RNA viruses occurs on cell membranes whose nature depends on the virus such as ER‐derived membranes (Carette 2000, den Boon 2001, Dunoyer 2002, Más 1999, Ritzenthaler 2002, Schaad 1997), cytoplasmic inclusions (Dohi et al., 2001), vacuolar membranes (Hagiwara 2003, van der Heijden 2001), invaginations of chloroplast membranes (Prod'homme et al., 2001), or multivesicular bodies derived from peroxisomes, vacuoles, or mitochondria (Dunoyer et al., 2002). Cowpea mosaic comovirus (CPMV) replication is linked to small membranous vesicles that proliferate upon virus infection. CPMV but neither alfalfa mosaic bromovirus nor TMV replication requires ongoing lipid biosynthesis, and replication of CPMV is inhibited by the antibiotic cerulenin, an inhibitor of lipid biosynthesis (Carette 2000, van der Heijden 2002).

A yeast mutant defective in BMV RNA replication was characterized; it is defective in the OLE1 gene (Lee et al., 2001) that encodes a Δ9 fatty acid desaturase, essential for the conversion of saturated to unsaturated fatty acids (UFAs) (Table IV ). This desaturase is an integral protein of the ER, the site of BMV RNA replication. As such, it is not required for BMV RNA replication, but high levels of UFAs are required at one of the steps leading to RNA replication. UFAs could participate in the assembly of a functional complex for replication.

TABLE IV.

Host Cell Membrane Components Involved in Virus Amplification

| Virus | Family/Genus (genome polarity) | Host membrane component | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| BMV | Bromoviridae (+) | UFA | Lee et al. (2001) |

| FHV | Nodaviridae (+) | PGL | Wu et al. (1992) |

| SFV | Togaviridae (+) | Phosphatidylserine | Ahola et al. (1999) |

| TMV | Tobamovirus (+) | TOM1 | Yamanaka et al. (2000) |

| TOM2A | Tsujimoto et al. (2003) | ||

| HCV | Flaviviridae (+) | hVAP‐33 | Gao et al. (2004) |

BMV, brome mosaic virus; FHV, flock house virus; SFV, Semliki Forest virus; TMV, tobacco mosaic virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; UFA, unsaturated fatty acid; PGL, phosphoglycerolipid; TOM1 and 2A, tobamovirus multiplication 1 and 2A proteins; hVAP‐33, human homologue of the 33‐kDa vesicle‐associated membrane protein‐associated protein.

Isolated membrane complexes can, in certain cases, support the production of replicative intermediates in vitro and the elongation of RNA chains to produce genomic‐length viral RNAs. Early work demonstrated that nuclease digestion of the membrane‐bound FHV RNA yielded a template‐dependent RNA polymerase. However, upon addition of the template RNA, only dsRNA intermediates were produced due to synthesis of only (−) RNA strands. Yet, upon addition of certain phosphoglycerolipids (PGLs), both (−) and (+) strands were produced, and complete replication of the genomic RNA was restored (Buck 1996, Wu 1991, Wu 1992). It was postulated that either interaction of PGLs with the polymerase was required to initiate (+) strand synthesis, or that the PGLs modified the configuration of the membrane to mimic the modifications occurring in virus‐infected cells.

In cells infected with viruses such as Semliki Forest virus (SFV; Togaviridae) (Perez et al., 1991) or poliovirus (Guinea and Carrasco, 1991), the level of lipid synthesis increases, and inoculation with cerulenin prevents replication of these viruses. Cerulenin also inhibits poliovirus replication in vitro. Continuous lipid synthesis is required for synthesis of SFV RNA (Perez et al., 1991).

The SFV replicase is composed of the four nonstructural proteins 1 to 4 (NSP1‐NSP4). NSP4 is the catalytic subunit of the replicase, and NSP1 contains the capping enzyme activities. NSP1 directly associates with several cell membranes such as the plasma membrane, endosomes, and lysosomes, and its attachment to membranes is required for its activity. Solubilization of NSP1 with various detergents strongly inhibits these activities, but they can be restored by the addition of anionic phospholipids, in particular phosphatidylserine (Ahola et al., 1999). As of yet, the elements in the membrane that are affected by the detergents remain undefined, as does how the lipids affect the membrane‐associated replication system.

TOM1 and TOM2A are Arabidopsis thaliana transmembrane proteins normally located with vacuolar membranes and other uncharacterized cytoplasmic membranes. TOM1 interacts with TOM2A and with the helicase domain of the TMV polymerase (Tsujimoto 2003, Yamanaka 2000). Inactivation of either of the corresponding genes significantly reduces TMV replication, implying that in vivo both proteins are involved in the formation of the replication complex (Ohshima 1998, Yamanaka 2000). Mutations in either the TOM1 or the TOM2A gene decrease TMV multiplication but do not affect replication of three unrelated plant RNA viruses.

It was recently shown (Gao et al., 2004) that binding of the HCV polymerase NS5B as well as of NS5A to the cellular vesicle membrane transport protein hVAP‐33 is necessary for the formation of the HCV replication complex on lipid raft and for viral RNA replication. Experiments were carried out using a subgenomic HCV replicon in a hepatocyte cell line transfected with siRNA against hVAP‐33 or overexpressing truncated versions of hVAP‐33. In both cases, the association of the viral nonstructural proteins with the lipid raft was inhibited, and the overall level of viral proteins was lower than in control cells. In the hVAP‐33 mutant‐expressing cells, the level of HCV (+) RNA synthesis was correlated with disruption of this association, supporting the significance of interaction of hVAP‐33 with NS5B and NS5A for HCV replication.

VIII. Perspectives

Virus multiplication negatively affects its host as reflected by the appearance of symptoms and diminished performance of the host that are the basis of disease. The organism retorts with a series of programmed responses to counteract the development of virus infection. This situation triggers reiterated counteroffensives between the host and the virus. Whereas the host is indispensable for the virus, the reverse is rarely true. It is only in very few cases that the presence of a virus is beneficial for the host as in the case of yeast strains infected with dsRNA viruses that secrete peptide toxins lethal to virus‐free yeast cells (Sesti et al., 2001). Thus, it can appear surprising that so many host factors normally engaged in vital cell functions can be subverted by the virus for its own benefit. The participation of an ever‐increasing number of host factors in virus replication/transcription is indeed somewhat unexpected, as is the variety of these factors. Moreover, the borrowed factors do not necessarily serve the same function in virus development such as in RNA replication/transcription as they serve in the host, making their identification more laborious. Indeed, some of them are usually associated with functions distantly related to nucleic acid multiplication. In many cases, it still cannot be dismissed that these factors act by stimulating other factors that are more directly involved in viral RNA genome amplification.

Basically, the viral RdRp constitutes the core of the polymerizing enzyme complex, essentially providing the machinery that will produce complementary RNA copies of the template. It has been shown that relatively pure preparations of several RdRps can replicate certain natural or synthetic RNAs. Specificity is provided in large part by ancillary viral factors and by a cohort of satellite host factors (Klovins 1999, Lai 1998). Intracellular virus–host interactions are both intimate and varied. Certain viruses are tissue specific, restricted to certain cell types, and this must be ascribed to the presence or absence of adequate host factors anywhere along the path of virus development. Other viruses replicate in diverse hosts, indicating that critical cell proteins required by these viruses must be highly conserved between host species. An interesting example of this situation is provided by experiments showing that the insect virus FHV not only multiplies but also systemically spreads through a transgenic plant expressing the viral movement protein of a plant virus (Dasgupta et al., 2001).

As more is learned about viral genomes, it is becoming clear that interactions of proteins with secondary and tertiary RNA structures allow the RNA to adopt various folding patterns and constitute major elements modulating gene expression. For example, the 5′ and 3′ UTRs as well as RNA structures located within the coding regions are vital for (−) RNA strand synthesis of rhinoviruses, enteroviruses, and cardioviruses (Murray and Barton, 2003).

There is increasing evidence that circularization of mRNAs is an important step in protein synthesis, presumably because it allows ribosomes to be redirected from the 3′ to the 5′ end of the mRNA for a new round of translation and probably because it ensures that only intact mRNA is translated. Circularization involves the participation of cap‐ and poly(A)‐binding proteins. It is also important for translation and replication of RNA viruses. For viral genomes containing a cap structure and a poly(A) tail, circularization could be brought about by a mechanism similar to the one used by cellular mRNAs. For viral genomes devoid of cap and/or poly(A) tail, other mechanisms must be invoked. Host factors participate in bringing close to one another distantly located regions of the RNA in poliovirus (Gamarnik 1998, Sadowy 2001, Wimmer 1982) and Qβ phage (Klovins 1999, Schuppli 2000). There are numerous other cases of viral RNA circularization involving essentially RNA–RNA interactions, and the functional importance of these interactions for viral gene expression has been demonstrated (Khromykh 2001, Shen 2004, Yang 2004). It is, however, not unlikely that as for Qβ, viral and/or host factors could be implicated in regulating circularization and triggering a switch between translation and replication. Some of the same host factors could be involved in both mechanisms.

None of the strategies used so far to study the involvement of host factors in viral RNA amplification has been without pitfalls, and frequently the data reported attempt to answer certain but not other questions. What then might be the most appropriate strategy to unambiguously distinguish between factors involved in replication and/or transcription but not in translation, between (−) and (+) strand RNA synthesis, and between those directly involved in a given mechanism and those that affect this mechanism indirectly? It would, for instance, be instructive to investigate by appropriate methods, not only synthesis of the viral genome RNA and of its complementary strand, but at the same time also translation. Such questions must ultimately be addressed both in vitro and in vivo. Having identified potential factors by a screening process such as the one involving the yeast system (Kushner et al., 2003), a reductionist approach might best be adopted to pinpoint the exact step at which a given factor is required, using various constructs, each allowing only one specific step to be examined. Following these experiments, more intricate models could be envisaged. This strategy demands huge investments in time and effort. However, it can be hoped that the availability of eukaryotic genome sequences and of an ever increasing number of infectious viral clones and replicons, the development of more reliable replication systems, and finally the advent of nanotechnology will facilitate such endeavors. Moreover, the rapidly developing RNA interference methodology and its application to genome‐wide screening of gene functions and protein interactions, including in mammals, now enables large‐scale identification of host genes whose down regulation (knock‐down) will have a severe impact on viral replication (Fraser 2004, Paddison 2004). An HCV replicon‐bearing human hepatocarcinoma cell line that has become one of the favorite models to study host factor influence on viral genome amplification would be a good target for such an experiment.

In conclusion, over the past few years, much has been done to establish which host factors participate in viral genome amplification. Although the exquisite function of many of these protein–protein and RNA–protein interactions must still be established, their identification is a first step towards further understanding of the function of these interactions in the virus life cycle.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to Karla Kirkegaard, Leevi Kääriäinen, Masayuki Ishikawa, Andrzej Palucha, Peter Sarnow, and Eric Snijder for careful reading of the manuscript, fruitful discussions, and constructive comments. This work was partly supported by the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS, France), the Center of Excellence of Molecular Biotechnology (Poland), the French‐Polish Center of Plant Biotechnology (CNRS and Polish Academy of Science), and the University of Antioquia and Colciencias (Colombia).

References

- Ahlquist P. RNA‐dependent RNA polymerases, viruses and RNA silencing. Science. 2002;296:1270–1273. doi: 10.1126/science.1069132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahlquist P., Noueiry A.O., Lee W.‐M., Kushner D.B., Dye B.T. Host factors in positive‐strand RNA virus genome replication. J. Virol. 2003;77:8181–8186. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.15.8181-8186.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahola T., Lampio A., Auvinen P., Kääriäinen L. Semliki Forest virus mRNA capping enzyme requires association with anionic membrane phospholipids for activity. EMBO J. 1999;18:3164–3172. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.11.3164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anwar A., Ali N., Tanveer R., Siddiqui A. Demonstration of functional requirement of polypyrimidine tract‐binding protein by SELEX RNA during hepatitis C virus internal ribosome entry site‐mediated translation initiation. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:34231–34235. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006343200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atreya C.D., Lee N.S., Forng R.Y., Hofmann J., Washington G., Marti, G., Nakhasi H.L. The rubella virus putative replicase interacts with the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor protein. Virus Genes. 1998;16:177–183. doi: 10.1023/a:1007998023047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Back S.H., Kim Y.K., Kim W.J., Cho S., Oh H.R., Kim J.‐E., Jang S.K. Translation of polioviral mRNA is inhibited by cleavage of polypyrimidine tract‐binding proteins executed by polioviral 3Cpro. J. Virol. 2002;76:2529–2542. doi: 10.1128/jvi.76.5.2529-2542.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belov G.A., Evstafieva A.G., Rubtsov Y.P., Mikitas O.V., Vartapetian A.B., Agol V.I. Early alteration of nucleocytoplasmic traffic induced by some RNA viruses. Virology. 2000;275:244–248. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenthal T., Carmichael G.G. RNA replication: Function and structure of Qβ‐replicase. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1979;48:525–548. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.48.070179.002521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blyn L.B., Towner J.S., Semler B.L., Ehrenfeld E. Requirement of poly(rC) binding protein 2 for translation of poliovirus RNA. J. Virol. 1997;71:6243–6246. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.8.6243-6246.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borden K.L.B., Campbelldwyer E.J., Carlile G.W., Djavani M., Salvato M.S. Two RING finger proteins, the oncoprotein PML and the Arenavirus Z protein, colocalize with the nuclear fraction of the ribosomal P proteins. J. Virol. 1998;72:3819–3826. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.3819-3826.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouloy M., Plotch S.J., Krug R.M. Globin mRNA are primers for the transcription of influenza viral RNA in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1978;75:4886–4890. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.10.4886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck K.W. Comparison of the replication of positive‐stranded RNA viruses of plants and animals. Adv. Virus Res. 1996;47:159–251. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(08)60736-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke E., Dupuy L., Wall C., Barik S. Role of cellular actin in the gene expression and morphogenesis of human respiratory syncytial virus. Virology. 1998;252:137–148. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke E., Mahoney N.M., Almo S.C., Barik S. Profilin is required for optimal actin‐dependent transcription of respiratory syncytial virus genome RNA. J. Virol. 2000;74:669–675. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.2.669-675.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carette J.E., Stuiver M., van Lent J., Wellink J., van Kammen A. Cowpea mosaic virus infection induces a massive proliferation of endoplasmic reticulum but not Golgi membranes and is dependent on de novo membrane synthesis. J. Virol. 2000;74:6556–6563. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.14.6556-6563.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi K.S., Huang P., Lai M.M.C. Polypyrimidine‐tract‐binding protein affects transcription but not translation of mouse hepatitis virus RNA. Virology. 2002;303:58–68. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong J.‐L., Chuang R.‐Y., Tung L., Chang T.‐H. Ded1p, a conserved DExD/H‐box translation factor, can promote yeast L‐A virus negative‐strand RNA synthesis in vitro. Nucl. Acids Res. 2004;32:2031–2038. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhary S., De B.P., Banerjee A.K. Specific phosphorylated forms of glyceraldehyde 3‐phosphate dehydrogenase associate with human parainfluenza virus type 3 and inhibit viral transcription in vitro. J. Virol. 2000;74:3634–3641. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.8.3634-3641.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das T., Mathur M., Gupta A.K., Janssen G.M.C., Banerjee A.K. RNA polymerase of vesicular stomatitis virus specifically associates with translation elongation factor‐1 αβγ for its activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:1449–1454. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dasgupta R., Garcia B.H., Goodman R.M. Systemic spread of an RNA insect virus in plants expressing plant viral movement protein genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:4910–4915. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081288198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De B.P., Gupta S., Zhao H., Drazba J.A., Banerjee A.K. Specific interaction in vitro and in vivo of glyceraldehyde‐3‐phosphate dehydrogenase and LA protein with cis‐acting RNAs of human parainfluenza virus type 3. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:24728–24735. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.40.24728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De B.P., Banerjee A.K. Role of host proteins in gene expression of nonsegmented negative strand RNA viruses. Adv. Virus Res. 1997;48:169–204. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3527(08)60288-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De B.P., Banerjee A.K. Involvement of actin microfilaments in the transcription/replication of human parainfluenza virus type 3: Possible role of actin in other viruses. Microsc. Res. Tech. 1999;47:114–123. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0029(19991015)47:2<114::AID-JEMT4>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dember L.M., Kim N.D., Liu K.‐Q., Anderson P. Individual RNA recognition motifs of TIA‐1 and TIAR have different RNA binding specificities. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:2783–2788. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.5.2783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- den Boon J.A., Chen J., Ahlquist P. Identification of sequences in brome mosaic virus replicase protein 1a that mediate association with endoplasmic reticulum membranes. J. Virol. 2001;75:12370–12381. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.24.12370-12381.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Nova‐Ocampo M., Villegas‐Sepúlveda N., del Angel R.M. Translation elongation factor‐1α, La and PTB interact with the 3′ untranslated region of dengue 4 virus RNA. Virology. 2002;295:337–347. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diez J., Ishikawa M., Kaido M., Ahlquist P. Identification and characterization of a host protein required for efficient template selection in viral RNA replication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:3913–3918. doi: 10.1073/pnas.080072997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohi K., Mori M., Furusawa I., Mise K., Okuno T. Brome mosaic virus replicase proteins localize with the movement protein at infection‐specific cytoplasmic inclusions in infected barley leaf cells. Arch. Virol. 2001;146:1607–1615. doi: 10.1007/s007050170082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan R.C., Nakhasi H.L. La autoantigen binding to a 5′cis‐element of rubella virus RNA correlates with element function in vivo. Gene. 1997;201:137–149. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00438-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunoyer P., Ritzenthaler C., Hemmer O., Michler P., Fritsch C. Intracellular localization of the Peanut clump virus replication complex in tobacco BY‐2 protoplasts containing green fluorescent protein‐labeled endoplasmic reticulum or Golgi apparatus. J. Virol. 2002;76:865–874. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.2.865-874.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger D., Teterina N., Ehrenfeld E., Bienz K. Formation of the poliovirus replication complex requires coupled viral translation, vesicle production, and viral RNA synthesis. J. Virol. 2000;74:6570–6580. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.14.6570-6580.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrenfeld E. Initiation of translation by picornavirus RNAs. In: Hershey J.W.B., Mathews M.B., Sonenberg N., editors. “Translational Control”. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 1996. pp. 549–573. [Google Scholar]

- Follett E.A.C., Pringle C.R., Pennington T.H. Virus development in enucleate cells: Echovirus, poliovirus, pseudorabies virus, reovirus, respiratory syncytial virus and Semliki Forest virus. J. Gen. Virol. 1975;26:183–196. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-26-2-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forng R.‐Y., Atreya C.D. Mutations in the retinoblastoma protein‐binding LXCXE motif of rubella virus putative replicase affect virus replication. J. Gen. Virol. 1999;80:327–332. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-2-327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser A. Human genes hit the big screen. Nature. 2004;428:375–378. doi: 10.1038/428375a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamarnik A.V., Andino R. Two functional complexes formed by KH domain containing proteins with the 5′ noncoding region of poliovirus RNA. RNA. 1997;3:882–892. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamarnik A.V., Andino R. Switch from translation to RNA replication in a positive‐stranded RNA virus. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2293–2304. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.15.2293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamarnik A.V., Andino R. Interactions of viral protein 3CD and poly(rC) binding protein with the 5′ untranslated region of the poliovirus genome. J. Virol. 2000;74:2219–2226. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.5.2219-2226.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao L., Tu H., Shi S.T., Lee K.‐J., Asanaka M., Hwang S.B., Lai M.M.C. Interaction with a ubiquitin‐like protein enhances the ubiquitination and degradation of hepatitis C virus RNA‐dependent RNA polymerase. J. Virol. 2003;77:4149–4159. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.7.4149-4159.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao L., Aizaki H., He J.‐W., Lai M.M.C. Interactions between viral nonstructural proteins and host protein hVAP‐33 mediate the formation of hepatitis C virus RNA replication complex on lipid raft. J. Virol. 2004;78:3480–3488. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.7.3480-3488.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goh P.Y., Tan Y.‐J., Lim S.P., Tan Y.H., Lim S.G., Fuller‐Pace F., Hong W. Cellular RNA helicase p68 relocalization and interaction with the hepatitis C virus (HCV) NS5B protein and the potential role of p68 in HCV RNA replication. J. Virol. 2004;78:5288–5298. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.10.5288-5298.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gowda S., Satyanarayana T., Ayllón M.A., Albiach‐Martí M.R., Mawassi M., Rabindran S., Garnsey S.M., Dawson W.O. Characterization of the cis‐acting elements controlling subgenomic mRNAs of citrus tristeza virus: Production of positive‐ and negative‐stranded 3′‐terminal and positive‐stranded 5′‐terminal RNAs. Virology. 2001;286:134–151. doi: 10.1006/viro.2001.0987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guinea R., Carrasco L. Effects of fatty acids on lipid synthesis and viral RNA replication in poliovirus‐infected cells. Virology. 1991;185:473–476. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90802-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S., De B.P., Drazba J.A., Banerjee A.K. Involvement of actin microfilaments in the replication of human parainfluenza virus type 3. J. Virol. 1998;72:2655–2662. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.4.2655-2662.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustin K.E., Sarnow P. Effects of poliovirus infection on nucleo‐cytoplasmic trafficking and nuclear pore complex composition. EMBO J. 2001;20:240–249. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.1.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez‐Escolano A.L., Uribe Brito Z., del Angel R.M., Jiang X. Interaction of cellular proteins with the 5′ end of Norwalk virus genomic RNA. J. Virol. 2000;74:8558–8562. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.18.8558-8562.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez‐Escolano A.L., Vázquez‐Ochoa M., Escobar‐Herrera J., Hernández‐Acosta J. La, PTB, and PAB proteins bind to the 3′ untranslated region of Norwalk virus genomic RNA. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003;311:759–766. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.10.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagiwara Y., Komoda K., Yamanaka T., Tamai A., Meshi T., Funada R., Tsuchiya T., Naito S., Ishikawa M. Subcellular localization of host and viral proteins associated with tobamovirus RNA replication. EMBO J. 2003;22:344–353. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herold J., Andino R. Poliovirus RNA replication requires genome circularization through a protein‐protein bridge. Mol. Cell. 2001;7:581–591. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(01)00205-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiscox J.A. The nucleolus—a gateway to viral infection? Arch. Virol. 2002;147:1077–1089. doi: 10.1007/s00705-001-0792-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiscox J.A. The interaction of animal cytoplasmic RNA viruses with the nucleus to facilitate replication. Virus Res. 2003;95:13–22. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1702(03)00160-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang P., Lai M.M.C. Polypyrimidine tract‐binding protein binds to the complementary strand of the mouse hepatitis virus 3′ untranslated region, thereby altering RNA conformation. J. Virol. 1999;73:9110–9116. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.11.9110-9116.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang P., Lai M.M.C. Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1 binds to the 3′‐untranslated region and mediates potential 5′‐3′ end cross talks of mouse hepatitis virus RNA. J. Virol. 2001;75:5009–5017. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.11.5009-5017.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt S.L., Jackson R.J. Polypyrimidine‐tract binding protein (PTB) is necessary, but not sufficient, for efficient internal initiation of translation of human rhinovirus‐2 RNA. RNA. 1999;5:344–359. doi: 10.1017/s1355838299981414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iseni F., Garcin D., Nishio M., Kedersha N., Anderson P., Kolakofsky D. Sendai virus trailer RNA binds TIAR, a cellular protein involved in virus‐induced apoptosis. EMBO J. 2002;21:5141–5150. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isken O., Grassmann C.W., Sarisky R.T., Kann M., Zhang S., Grosse F., Kao P.N., Behrens S.‐E. Members of the NF90/NFAR protein group are involved in the life cycle of a positive‐strand RNA virus. EMBO J. 2003;22:5655–5665. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kääriäinen L., Ahola T. Functions of Alphavirus nonstructural proteins in RNA replication. Prog. Nucl. Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 2002;71:187–222. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6603(02)71044-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaminski A., Jackson R.J. The polypyrimidine tract binding protein (PTB) requirement for internal initiation of translation of cardiovirus RNAs is conditional rather than absolute. RNA. 1998;4:626–638. doi: 10.1017/s1355838298971898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kedersha N.L., Gupta M., Li W, Miller I., Anderson P. RNA‐binding proteins TIA‐1 and TIAR link the phosphorylation of eIF‐2α to the assembly of mammalian stress granules. J. Cell Biol. 1999;147:1431–1441. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.7.1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khromykh A.A., Meka H., Guyatt K.J., Westaway E.G. Essential role of cyclization sequences in Flavivirus RNA replication. J. Virol. 2001;75:6719–6728. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.14.6719-6728.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klovins J., van Duin J. A long‐range pseudoknot in Qβ RNA is essential for replication. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;294:875–884. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolakofsky D., Le Mercier P., Iseni F., Garcin D. Viral RNA polymerase scanning and the gymnastics of Sendai virus RNA synthesis. Virology. 2004;318:463–473. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2003.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushner D.B., Lindenbach B.D., Grdzelishvili V.Z., Noueiry A.O., Paul S.M., Ahlquist P. Systematic, genome‐wide identification of host genes affecting replication of a positive‐strand RNA virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:15764–15769. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2536857100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai M.M.C. Cellular factors in the transcription and replication of viral RNA genomes: A parallel to DNA‐dependent RNA transcription. Virology. 1998;244:1–12. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb R.A., Horvath C.M. Diversity of coding strategies in influenza viruses. Trends Genetics. 1991;7:261–266. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(91)90326-L. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan S., Wang H., Jiang H., Mao H., Liu X., Zhang X., Hu Y., Xiang L., Yuan Z. Direct interaction between α‐actinin and hepatitis C virus NS5B. FEBS Lett. 2003;554:289–294. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)01163-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee W.M., Ishikawa M., Ahlquist P. Mutation of host Δ9 fatty acid desaturase inhibits brome mosaic virus RNA replication between template recognition and RNA synthesis. J. Virol. 2001;75:2097–2106. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.5.2097-2106.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Li W.X., Ding S.W. Induction and suppression of RNA silencing by an animal virus. Science. 2002;296:1319–1321. doi: 10.1126/science.1070948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H.‐P., Zang X., Duncan R., Comai L., Lai M.M.C. Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1 binds to the transcription‐regulatory region of mouse hepatitis virus RNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:9544–9549. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.18.9544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]