Abstract

There are two concurrent and novel major research pathways toward strategies for HIV control: (1) long-acting antiretroviral therapy (ART) formulations and (2) research aimed at conferring sustained ART-free HIV remission, considered a step toward an HIV cure. The importance of perspectives from people living with HIV on the development of new modalities is high, but data are lacking. We administered an online survey in which respondents selected their likelihood of participation or nonparticipation in HIV cure/remission research based on potential risks and perceived benefits of these new modalities. We also tested the correlation between perceptions of potential risks and benefits with preferences of virologic control strategies and/or responses to scenario choices, while controlling for respondent characteristics. Of the 282 eligible respondents, 42% would be willing to switch from oral daily ART to long-acting ART injectables or implantables taken at 6-month intervals, and 24% to a hypothetical ART-free remission strategy. We found statistically significant gender differences in perceptions of risk and preferences of HIV control strategies, and possible psychosocial factors that could mediate willingness to switch to novel HIV treatment or remission options. Our study yielded data on possible desirable product characteristics for future HIV treatment and remission options. Findings also revealed differences in motivations and preferences across gender and other sociodemographic characteristics that may be actionable as part of research recruitment efforts. The diversity of participant perspectives reveals the need to provide a variety of therapeutic options to people living with HIV and to acknowledge their diverse experiential expertise when developing novel HIV therapies.

Keywords: antiretroviral therapy (ART), oral daily ART, long-acting ART, HIV cure research, HIV remission, people living with HIV, United States

Introduction

The development of oral combined antiretroviral therapy (ART) has transformed the HIV epidemic in the United States and many other countries by allowing people living with HIV (PLWHIV) to mitigate AIDS-related complications and prevent HIV transmission.1,2 Most PLWHIV take single-pill combination ART regimens and lead lives minimally encumbered by HIV-related side effects.3 Several highly effective classes of ART require daily dosing.4 However, sustained high levels of ART adherence remain a challenge and do not lead to cure.3,5 Two simultaneous major advances in HIV therapeutics are occurring: (1) long-acting (e.g., 1/month) ART formulations, which will soon be available in clinics across the United States and elsewhere,6 and (2) progress in global research aimed at conferring sustained ART-free HIV remission, with more than 250 ongoing or completed clinical trials.7,8

Long-acting ART should address some challenges with daily oral therapy (e.g., pill fatigue and other barriers to medication adherence).9–11 Possible advantages include the following: simplified dosing schedules, decreased side effects, enhanced quality of life, and/or mental well-being.9,10,12 Long-acting ART may also provide advantages to specific populations (e.g., homeless or unstably housed individuals and those with mental illness who have difficulty accessing daily ART). Drawbacks include the need for patients to adhere to clinic visits for injections or implants. Two long-acting intramuscular injectable agents are currently in Phase III drug development trials, including cabotegravir (CAB) and rilpivirine (RPV), which are coadministered monthly or bimonthly.6 Long-acting ART could be available in U.S. clinics as early as 2020.

Products aimed at conferring sustained ART-free HIV remission are concurrently under early-phase investigation. These HIV remission research strategies include, but are not limited to, early ART, immune-based strategies, stem cell transplantations, gene editing approaches, and latency reversing agents. These may be used alone or in combination.5 The aim of these approaches would be to temporarily or permanently allow PLWHIV to discontinue ART while maintaining viral suppression. HIV remission studies represent an inverted scenario from the early days of the HIV epidemic when PLWHIV joined clinical trials in the hope of staying alive13–15). Nowadays, PLWHIV are asked to take risks to advance HIV remission science without expectation of direct clinical benefits.16,17

The importance of patient perspectives in HIV treatment and remission development is becoming clearer, as research on HIV therapies is an increasingly crowded field with newly emerging and complex product profiles.18 Regulatory agencies such as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) prioritize patient preference in the drug development process.19 In 2014, the FDA's Patient-Focused Drug Development Initiative on HIV remission research released the Voice of the Patient report providing testimonials from PLWHIV and community advocates on the impact of HIV and its management.20 Findings from this report could be enhanced by incorporating scientific evidence on preferences from a broader community of PLWHIV.21

We previously published data regarding patient willingness to participate and take risks in various types of HIV remission research in the United States.16,22 Nevertheless, we know little about the perceptions of PLWHIV regarding emerging HIV therapies (e.g., long-acting ART or HIV remission strategies). Therefore, we undertook a survey intended to quantify preferences around various HIV treatment or remission options. We focused on desirable product characteristics (e.g., acceptable risks or benefits) from the perspectives of a diverse sample of adults living with HIV in the United States. The primary survey outcome was respondents' preferences for virologic control strategies (“HIV control strategies”). These HIV control strategies included oral daily ART versus long-acting ART injectables, or implantables versus a hypothetical ART-free HIV remission strategy.

We also tested whether the perceived risks and benefits in HIV remission research differentially influenced participant willingness. Finally, we examined (1) whether specific characteristics of HIV treatment and remission options affected likelihood of participating in research and to accept new regimens and (2) how preferences varied by demographic and health status characteristics. For consistency, in the survey we used the term “treatment” to refer to ART, while we used the National Institutes of Health (NIH)-endorsed term “remission” to denote research toward an HIV cure.8 By HIV control strategies, we mean the three strategies aimed at keeping HIV suppressed—such as continuous systemic oral ART, continuous systemic long-acting ART, and non-ART remission.

Methods

From May to August 2018, we administered an online, nationwide survey via Qualtrics (Provo, UT), using a cross-sectional design. Survey questions were developed in collaboration with community members (D.A., K.M., M.M., D.C.) and included extensive review and pilot testing. Due to funding and institutional review board (IRB) restrictions, the survey focused on a U.S. sample of PLWHIV. Survey participant inclusion criteria were at least 18 years of age, living with HIV, willing to give their opinion on HIV treatment and ART-free HIV remission research strategies and remission options, and living in the United States or its territories. ART status was not used as an inclusion criterion. Participants had to check a box certifying they met all eligibility criteria. There were no stated exclusion criteria. Participants self-reported their state of residence. While no mechanism was programmed to prevent survey participation from outside of the United States, only U.S.-based groups were asked to join our sampling approach (details below).

We recruited participants via a convenience sample of PLWHIV who had subscribed to HIV treatment and cure listservs. These included the following: immune-based therapy, the Martin Delaney Collaboratories Towards an HIV Cure Community Advisory Boards (MDC CABs), the AIDS Clinical Trials Group (ACTG), the AIDS Treatment Activists Coalition (ATAC), The Body, POZ, and the Forum for Collaborative Research. In an effort to increase representation of women and people of color, the survey was also advertised on listservs hosted by The Well Project and the Positive Women's Network-USA (PWN-USA), whose constituencies include cisgender and transgender women living with HIV in the United States.22,23 Recruitment posts referenced advancing social sciences related to HIV treatment and ART-free remission-related research. To incentivize participation, 1 in 10 participants was randomly chosen to receive a $20 U.S. Visa® gift card. Prospective participants were informed that they should begin the survey only if they could dedicate time to complete all the questions in one sitting. All participants completed an online informed consent form. The survey was approved by The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Non-Biomedical IRB (study #17–3084).

Measures

Respondent characteristics

The survey included questions related to demographics, current health status and HIV medication, opinions and experiences about current HIV medications, and past participation in HIV research.

Risk aversion versus benefit inclination for participation in HIV remission studies

Respondents selected their likelihood of participation in ART-free HIV remission research based on 25 specific potential clinical or social risks on a 5-point Likert scale. Similarly, they rated 16 potential social, psychological, emotional, or supportive benefits that would increase their willingness to participate in HIV remission research on a 5-point Likert scale.

To represent the likelihood of participation in ART-free HIV remission research, two composite scores were created based on each respondent's overall relative risk aversion and benefit inclination. Composite scores were percentile rankings of each individual's aggregated responses to the risk and benefit questions relative to all other survey respondents. Relative risk aversion was the percentage of all other survey respondents who had lower risk-averse responses cumulative over all risk questions (except for two questions related to childbearing due to gender/sex bias in response). The higher the relative risk aversion score, the more risk-averse respondents were relative to other survey participants. Relative benefit inclination was the percentage of all other survey respondents who had lower benefit-motivated responses cumulative over all benefits questions. The higher the relative benefit inclination score, the more motivated respondents were by perceived benefits relative to other survey participants. Relative risk aversion and relative benefit inclination were used as key independent variables in the multivariate regression models.

Perceived improvements over current HIV medication

Respondents were asked to rate the perceived improvement of 12 different potential outcomes of participating in HIV control strategies over their current HIV medication strategy on a 5-point Likert scale.

HIV control strategies

For their preferred HIV control strategy, respondents were asked to make a hypothetical choice between the following: (1) standard oral daily HIV medications, (2) long-acting ART injectables or implantables that last for 1, 2, or 6 months, or (3) a new, less understood strategy that might keep HIV in remission for an unspecified “long time.” This question was a single categorical variable, treated as the dependent variable in the bivariate and multivariate analyses to test correlations between the mutually exclusive choices in HIV control strategies and other respondent characteristics. “I don't know” responses were recorded in the descriptive summary statistics and removed from bivariate and multivariate analyses.

Scenario choices

The survey listed seven hypothetical scenarios with different ART-free HIV remission strategies having possible negative health consequences in exchange for no longer having to take oral ART. All scenarios started with the prompt: “How likely would you be to choose a new HIV remission strategy over standard daily HIV medication if…” The seven presented scenarios were as follows: (1) no longer taking daily pills, but having to go to the laboratory or clinic more often, (2) no longer taking daily pills, but having a small chance of passing HIV to a sexual partner, (3) taking a new approach with worse initial side effects that would eventually fade, (4) a risk of developing health problems (e.g., cancer) later in life, (5) having to stop taking HIV medications to see if the virus would come back, (6) no increase in life expectancy, and (7) no increase in quality of life.

Respondents were asked to choose between the following 5-point Likert scale responses: (1) not at all, (2) somewhat unlikely, (3) neither likely nor unlikely, (4) moderately likely, or (5) very likely (to switch to the new HIV remission strategy) under each scenario. This created an ordinal variable for each scenario and provided the dependent variable in the bivariate and multivariate analyses testing correlations between the increased likelihood to switch to a hypothetical HIV remission strategy and other respondent characteristics. “I don't know” responses were recorded in the descriptive summary statistics but were removed from bivariate and multivariate analyses.

Acceptable trade-offs

Respondents were asked about the hypothetical acceptability of five different trade-offs to switching to a new HIV remission strategy, using a Likert-type response scale. These five trade-offs were as follows: (1) having injections or infusions every few weeks for several months before they started working, (2) modest temporary changes to one's appearance, (3) enduring mild to moderate pain, (4) uncertainty about the new strategy working (with the possibility of having to return to standard HIV medication), and (5) changes in mental health status (e.g., anxiety or depression).

We provided definitions of all risks, benefits, improvements, strategies, scenario choices, and trade-offs in lay terms that were vetted by community members (D.A., K.M., M.M., D.C.). We randomized many categorical responses to prevent anchoring effects. Respondents were not required to answer all survey questions to advance in the survey.

Bivariate analyses

We ran bivariate correlation tests to determine whether respondent characteristics (e.g., demographics, current health status and HIV medication, and past participation in HIV research) were significantly correlated with preference for HIV control strategy and/or responses to the seven scenario choices.

HIV control strategies

Logistic models were used to test and report the odds ratio (OR) of each of the five categorical choices of HIV control strategies against each of the respondent characteristics.

Scenario choices

Ordered logistic models were used to test the bivariate correlations between the ordinal variables measuring the 5-point Likert scale responses to the seven HIV remission scenarios and respondent characteristics. The OR for choosing a higher answer, indicating a greater willingness to switch to a new HIV remission strategy, was calculated for each scenario and respondent characteristic pairing.

For all bivariate analyses, only statistically significant (at the 0.05 level) ORs are reported.

Multivariate analyses

We ran multivariate regression models to test whether perceptions of potential risks and benefits were significantly correlated with preferences for HIV control strategies and/or responses to scenario choices, while controlling for respondent characteristics. Independent variables throughout were relative risk aversion and benefit inclination scores and respondent characteristics.

HIV control strategies

We tested associations with the categorical dependent variable of preference for HIV control strategy. Only a small number of people chose long-acting ART taken at 1- or 2-month intervals. Consequently, we combined these responses with long-acting ART taken at 6-month intervals. This combination converted the stated preference for HIV control strategy to three mutually exclusive categorical choices: (1) daily oral ART (n = 20), (2) long-acting ART injectables or implantables taken at 1-, 2- or 6-month intervals (n = 125), or (3) a new ART-free HIV remission strategy (n = 55). A multinomial logit regression model was used to test respondents' relative risk aversion and relative benefit inclination on their stated preferences, controlling for all other variables. We hypothesized that respondents with higher relative risk aversion scores and lower relative benefit inclination scores were more likely to choose oral daily pills over alternative HIV control strategies.

Scenario choices

We tested associations with ordinal dependent variables of the likelihood of being willing to switch to a new remission strategy under each of the seven scenarios. Ordered logistic regression models were used to test respondents' relative risk aversion and relative benefit inclination on greater willingness to switch to a new HIV remission strategy under each of the scenarios when controlling for all other variables. We hypothesized that higher relative risk aversion scores and lower relative benefit inclination scores would be associated with less willingness to switch to a new HIV remission strategy under all scenarios.

All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata (version 14; StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

Survey respondents

In total, 282 eligible respondents completed the survey: 63% were cisgender men, 35% cisgender women, 1% transgender women, and 1% did not specify a gender. Participants were racially and ethnically diverse: 65% were white/Caucasian, 24% black/African American, 4% Asian, 4% multiracial, and 3% other, and 12% had Hispanic heritage. Mean participant age was 47 years, and 86% had at least some college education. Demographic characteristics of survey respondents are summarized in Table 1. Due to attrition during the survey, sample sizes declined from n = 282 for initial questions to n = 220 for final questions. Therefore, 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) range from ±5.84% to 6.61% for descriptive survey responses.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Survey Respondents (United States, 2018)

| n | % | n | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | n = 282 | Region of residency | n = 272 | ||

| Cisgender woman | 98 | 35 | Northeast | 43 | 16 |

| Cisgender man | 179 | 63 | Midwest | 32 | 12 |

| Transgender woman | 3 | 1 | South | 123 | 45 |

| Transgender man | 0 | 0 | West | 74 | 27 |

| Nonbinary or gender queer | 0 | 0 | |||

| Something else | 1 | 0.4 | Race | n = 278 | |

| Prefer not to answer | 1 | 0.4 | White or Caucasian | 182 | 65 |

| Black or African American | 66 | 24 | |||

| Sex assigned at birth | n = 280 | Asian | 10 | 4 | |

| Female | 96 | 34 | Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 1 | 0.4 |

| Male | 184 | 66 | Native American/Alaska Native | 0 | 0 |

| More than one race | 12 | 4 | |||

| Age | n = 281 | Other | 7 | 3 | |

| Mean (years) | 47 | ||||

| Median (years) | 49 | Ethnicity | n = 271 | ||

| Minimum (years) | 19 | Hispanic or Latinx | 32 | 12 | |

| Maximum (years) | 72 | Not Hispanic or Latino/Latina | 226 | 83 | |

| Not sure/prefer not to answer | 13 | 5 | |||

| Age groups (years) | |||||

| 19–29 | 33 | 12 | Highest level of formal education completed | n = 281 | |

| 30–39 | 52 | 19 | Some high school, but no diploma | 9 | 3 |

| 40–49 | 62 | 22 | High school diploma or G.E.D. | 31 | 11 |

| 50–59 | 90 | 32 | Some college, but no diploma | 84 | 30 |

| 60–72 | 44 | 16 | 2-year college degree | 16 | 6 |

| 4-year college degree | 77 | 27 | |||

| Marital status | n = 220 | Master's/professional degree or equivalent | 51 | 18 | |

| Single, never married | 98 | 45 | Doctorate degree or equivalent | 13 | 5 |

| Separated | 4 | 2 | |||

| Divorced | 34 | 15 | Yearly household income | n = 220 | |

| Widowed | 10 | 5 | Less than $15,000 | 41 | 19 |

| Living with a partner | 29 | 13 | $15,000–$25,000 | 28 | 13 |

| Married, without children | 23 | 10 | $25,001–$50,000 | 56 | 25 |

| Married, with children | 15 | 7 | $50,001–$75,000 | 24 | 11 |

| Other | 7 | 3 | $75,001–$100,000 | 18 | 8 |

| More than $100,000 | 43 | 20 | |||

| Prefer not to answer | 10 | 5 |

GED, General Education Diploma.

Descriptive results and differences by gender/sex

Nearly all survey respondents (99%) were taking ART. Most respondents (87%) were taking once-daily ART, 12% reported taking twice-daily ART, and 1% took ART thrice-daily or more. About 30% reported experiencing side effects from their HIV medications that did not bother them too much, while 10% reported side effects from HIV medications that bothered them a great deal. Over two-thirds (71%) were grateful to have medications that kept them healthy. Forty-seven percent reported that taking HIV medications made them feel in control of their health. Table 2 summarizes respondents' experiences with current HIV medications.

Table 2.

Experiences with Current HIV Medication (Oral Daily Antiretroviral Therapy) (United States, 2018)

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Currently taking HIV medication (ART) | n = 282 | |

| Yes | 279 | 99 |

| No | 3 | 1 |

| Don't know/not sure | 0 | 0 |

| HIV medication regimen of the 279 respondents taking ART | ||

| No. of ART pills or tablets taken per day | n = 279 | |

| One pill per day | 164 | 59 |

| Two to three pills per day | 94 | 34 |

| Four or more pills per day | 21 | 8 |

| No. of times per day taking ART | n = 278 | |

| Once per day | 243 | 87 |

| Twice per day | 32 | 12 |

| Three or more times per day | 3 | 1 |

| Interactions with food or other drugs affect timing of ART | n = 279 | |

| Yes | 66 | 24 |

| No | 196 | 70 |

| Don't know/not sure | 17 | 6 |

| Feelings about HIV medication | n = 279 | |

| Very grateful to have medication that is keeping me healthy | 198 | 71 |

| Taking medication makes me feel in control of my health and my life | 130 | 47 |

| Worry that I will not be able to afford or have access to my medication | 96 | 34 |

| Worry that my medication will stop working | 68 | 24 |

| Taking my medication causes me to feel badly about myself or my life | 47 | 17 |

| Side effects from HIV medication | n = 276 | |

| Have side effects but they don't bother me too much | 82 | 30 |

| Have side effects and they bother me a great deal | 28 | 10 |

| Trouble taking HIV medication on time | n = 215 | |

| Have no trouble taking my medication on time every day | 194 | 90 |

| Have trouble remembering to take my medication | 23 | 11 |

| Feeling on trying a completely different kind of HIV medication regimen (ART) | n = 278 | |

| I would gladly try it | 151 | 54 |

| I would be worried about the side effects | 138 | 50 |

| I would feel anxious about it not working | 110 | 40 |

ART, antiretroviral therapy.

When asked to assess their own health status on a scale of 0% (poor) to 100% (excellent), 91% of respondents reported a score ≥50% denoting self-perceived good health. The three most common reasons for perceived poor health among the 27 respondents with a health status rating below 50% were: (1) mental health challenges (17/24), (2) ART-related side effects (14/24), and (3) physical illness not related to HIV infection (10/24). Of all the survey respondents, 21% had ever volunteered for an HIV treatment study and 10% had ever volunteered for an HIV remission study. The most stated reason respondents did not participate in HIV remission research was not knowing about studies (71%), followed by transportation issues (16%) and ineligibility (16%) (Table 3).

Table 3.

History and Interest in HIV-Related Studies (United States, 2018)

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Ever volunteered for a study to test safety or efficacy of an ART drug or related drug | n = 278 | |

| Yes | 57 | 21 |

| No | 216 | 78 |

| Don't know | 5 | 2 |

| Ever volunteered for a medical study respondent believed to be an HIV cure study | n = 278 | |

| Yes | 28 | 10 |

| No | 244 | 88 |

| Don't know | 6 | 2 |

| Reasons why the 244 respondents did not participate in HIV cure studies | n = 243 | |

| Did not know about them | 173 | 71 |

| Study site too far away/did not compensate for travel costs | 40 | 16 |

| Did not qualify for them | 38 | 16 |

| Frightened because it would stop HIV medications for some period of time | 33 | 14 |

| Frightened of side effects or negative health effects | 24 | 10 |

| Could not get away from work | 16 | 7 |

| Required too much time away from regular routine | 12 | 5 |

| Regular health provider recommended that I not participate | 11 | 5 |

| Friend or family member said that I shouldn't participate | 4 | 2 |

| Study did not cover childcare/family care costs involved in participation | 1 | 0.4 |

| Other | 23 | 9 |

| Currently in a study respondent believes to be an HIV cure study | n = 278 | |

| Yes | 9 | 3 |

| No | 266 | 96 |

| Don't know | 3 | 1 |

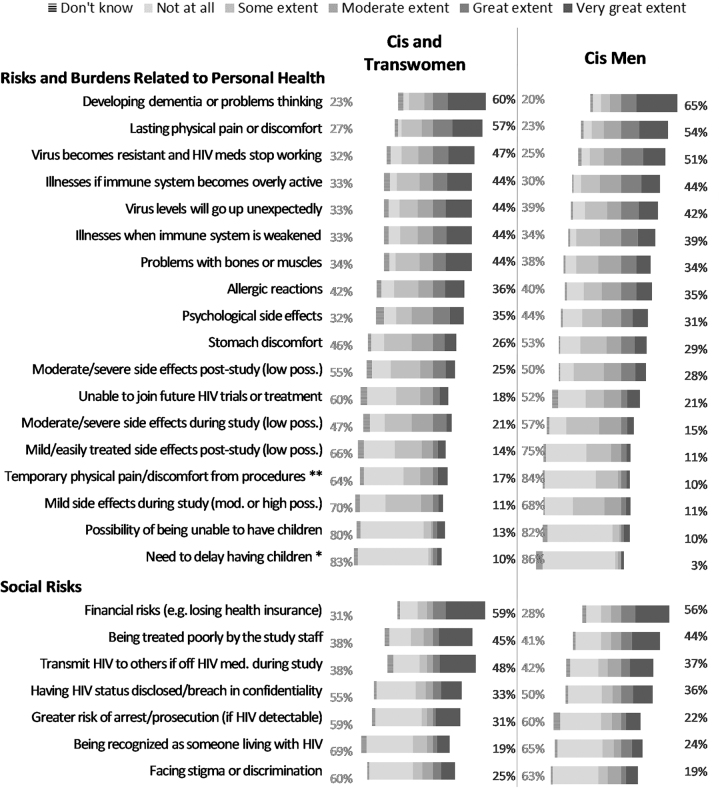

Risk aversion for participation in HIV remission studies

The mean relative risk aversion score for all respondents was 42.7 (n = 241, standard deviation [sd] = 22.8). The minimum was 0 (not at all risk averse) and the maximum was 100 (completely risk averse). The main deterrent to participation in HIV remission research was a fear of developing dementia or having difficulty thinking; 63% reported that this would demotivate them to a great or a very great extent. The top three clinical risks deterring participation in HIV remission research were (1) lasting physical pain or discomfort (55%), (2) developing ART-resistant virus (49%), and (3) significant changes to one's immune system (44%). In terms of perceived social risks, the fear of losing health insurance was the most prevalent deterrent (57%), followed by the risk of being treated poorly by study staff (44%), and the risk of transmitting HIV to a partner during treatment interruption (41%) (Supplementary Fig. S1).

When data were disaggregated by gender, cisgender and transgender women were more greatly demotivated by temporary physical pain or discomfort from procedures (p = .001). Cisgender women were more greatly demotivated by the need to delay having children (p = .024) compared with cisgender men (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Extent to which risk factors are “Likely to Stop” respondents from participating in an HIV cure-oriented study, by gender/sex (United States, 2018). Percentages on the left reflect the sum of “not at all” and “some extent” likelihood to stop respondent from participating in an HIV cure-oriented study. Percentages on the right reflect the sum of “very great extent” and “great extent” likelihood to stop respondent from participating in an HIV cure-oriented study. Excludes two respondents who did not specify their gender. n = 89–91 for cis and trans women. n = 151–155 for cis men. No transgender men participated in the survey. Asterisks indicate the factors for which the differences in percentages of choosing “very great extent”/“great extent” or “not at all”/“some extent” are statistically significantly different for cis and trans women than for cis men: **p < .01, *p < .05.

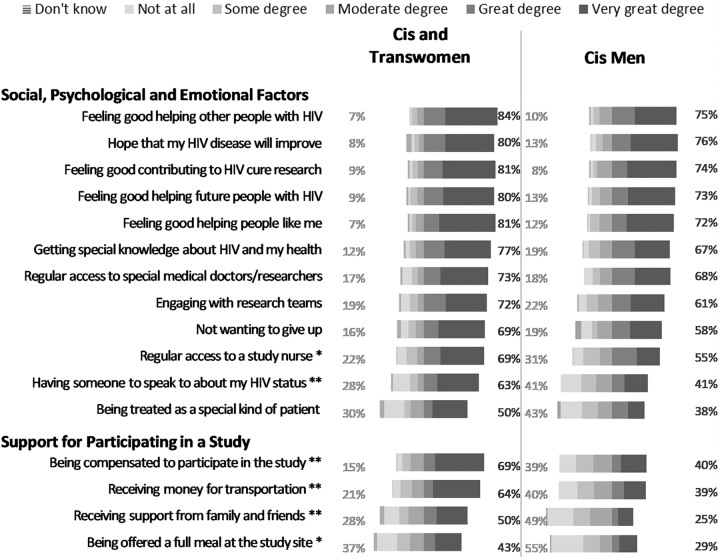

Benefit inclination for participation in remission studies

The mean relative benefit inclination score was 61.7 (n = 230; sd = 25.6). The minimum was 4.2 (very low motivation) and the maximum was 100 (total motivation). Primary respondent motivators included the following: feeling good about helping other people with HIV (78%), contributing to research (77%), and helping future PLWHIV (76%). More than three-quarters (78%) of participants would to a great or very great extent be motivated by direct clinical benefits. Fifty-one percent of respondents would to a great or very great extent be motivated by monetary compensation (Supplementary Fig. S2). When data were disaggregated by gender, cisgender and transgender women were statistically significantly more motivated by having regular access to a study nurse (p = .039), having someone to speak to about their HIV status (p = .001), receiving support from family and friends (p < .001), receiving financial compensation (p < .001), being offered a full meal at the study site (p = .026), and receiving support for transportation (p < .001) (Fig. 2) than cisgender men.

FIG. 2.

Degree by which factors increase respondents' willingness to participate in an HIV cure-oriented study, by gender/sex (United States, 2018). Percentages on the left reflect the sum of “not at all” and “some degree” by which respondent's willingness to participate in an HIV cure-oriented study would increase. Percentages on the right reflect the sum of “very great degree” and “great degree” by which respondent's willingness to participate in an HIV cure-oriented study would increase. Excludes two respondents who did not specify their gender. n = 85–86 for cis and trans women. n = 145–146 for cis men. No transgender men participated in the survey. Asterisks indicate the factors for which the differences in percentages of choosing “very great degree”/“great degree” or “not at all”/“some degree” are statistically significantly different for cis and trans women than for cis men:**p < .01,*p < .05.

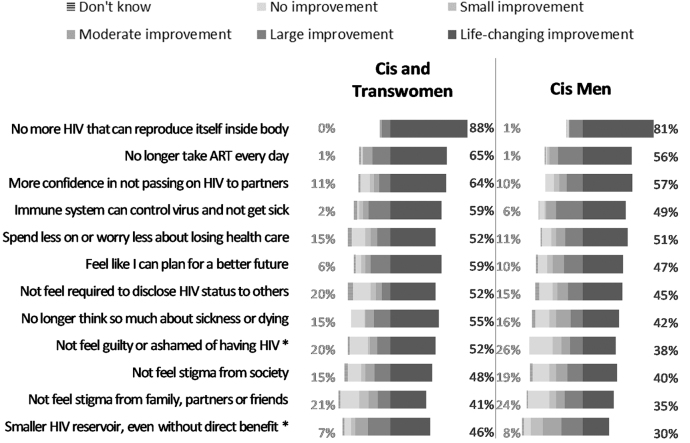

Perceived improvements over current HIV medication

In terms of desirable characteristics of a potential HIV control strategy, the three most desired life-changing improvements were as follows: (1) not having replication-competent HIV inside the body (83%), (2) no longer taking oral daily ART (59%), and (3) more confidence in not being able to pass HIV to others (59%). Categories that would represent no improvement pertained mostly to psychosocial factors, including (1) not feeling guilt or shame from having HIV (24%), (2) not feeling stigma from family, partners, or friends (23%), and (3) not feeling stigma from society (18%) (Supplementary Fig. S3). When data were disaggregated by gender, cisgender and transgender women were statistically more likely to consider not feeling guilt or shame from having HIV (p = .034) and having a small HIV reservoir size, even without direct clinical benefit (p = .015), to be life-changing improvements, compared with cisgender men (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Improvement over current HIV medication strategy offered by a promising future HIV remission or cure strategy, by gender/sex (United States, 2018). Percentages on the left reflect “no improvement.” Percentages on the right reflect “life-changing improvement.” Excludes two respondents who did not specify their gender. n = 85 for cis and trans women. n = 144 for cis men. No transgender men participated in the survey. Asterisks indicate the factors for which the differences in percentages of choosing “life-changing improvement” or “ no improvement” are statistically significantly different for cis and trans women than for cis men:*p < .05.

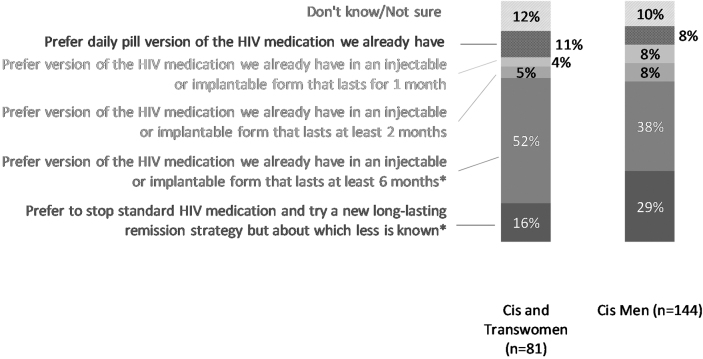

HIV control strategies

When given a choice between HIV control strategies, 9% of respondents would remain on daily oral ART, 6% would prefer long-acting ART injectable or implantable taken at 1-month intervals, 7% would prefer long-acting ART taken at 2-month intervals, 42% would prefer long-acting ART taken at 6-month intervals, 24% indicated they would prefer a new ART-free HIV remission strategy about which less is known, and 12% selected “I don't know.” When data were disaggregated by gender, cisgender and transgender women were more willing to switch a 6-month long-acting ART regimen compared with cisgender men (p = .020). Cisgender men were more willing to try a new ART-free HIV remission strategy compared with cisgender and transgender women (p = .033) (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Choice between current standard daily HIV medications versus long-acting antiretrovirals versus new experimental HIV remission strategy, by gender/sex (United States, 2018). Excludes two respondents who did not specify their gender. No transgender men participated in the survey. Asterisks indicate the choices for which the differences in percentages are statistically significantly different for cis and trans women than for cis men: *p < .05.

Scenario choices

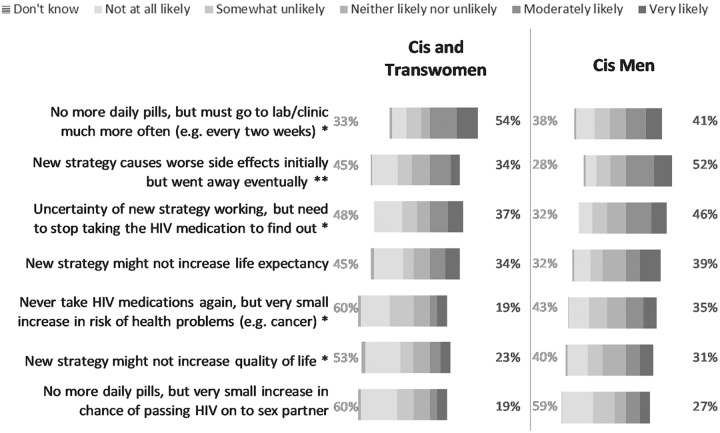

In total, 46% of respondents would be very or moderately willing to switch to an HIV remission regimen if it meant no more daily ART even with additional clinic visits for monitoring. This was followed by 45% of respondents who would switch if the new strategy caused side effects initially that would improve over time. However, 49% of respondents would not at all or would be somewhat unlikely to switch if the HIV remission regimen would increase the risk for developing health problems later in life (e.g., cancer). Furthermore, 59% would not at all or be somewhat unlikely to switch if there were an increased risk of transmitting HIV to others (Supplementary Fig. S4). When data were disaggregated by gender, cisgender and transgender women were less likely to choose the scenarios that would lead to risks in having health problems later in life (p = .019), that would result in worse side effects even if temporary (p = .006), that are uncertain to work without first stopping HIV medication (p = .018), or that might not increase life expectancy (p = .046) or quality of life (p = .032) compared with cisgender men. Cisgender and transgender women were more likely to choose a scenario that would mean no more daily pills but having to visit the clinic more often (p = .045) compared with cisgender men (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Likelihood of choosing a new HIV remission strategy over standard daily HIV medication under different scenarios, by gender/sex (United States, 2018). Percentages on the left reflect the sum of “not at all likely” and “somewhat unlikely” to switch to the new HIV remission strategy. Percentages on the right reflect the sum of “very likely” and “moderately likely” to switch to the new HIV remission strategy. Excludes two respondents who did not specify their gender. n = 83 for cis and trans women. n = 141–143 for cis men. No transgender men participated in the survey. Asterisks indicate the remission strategies for which the differences in percentages of choosing “very likely”/“moderately likely” or “not at all likely”/“somewhat unlikely” to switch are statistically significantly different for cis and trans women than for cis men: **p < .01, *p < .05.

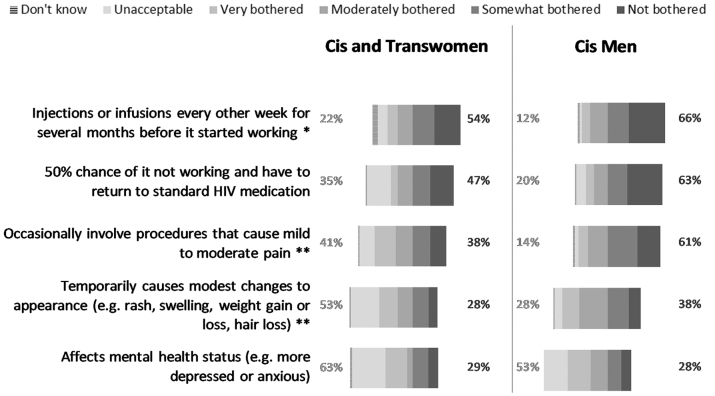

Acceptable trade-offs

We asked respondents to indicate hypothetical acceptability around five possible inconveniences, side effects, and unpleasant circumstances of new HIV treatment or remission regimens. In the aggregate results, 61% of respondents would only be somewhat bothered or not at all bothered by having injections/infusions every other week for several months before the strategy started working. Fifty-three percent would be willing to undergo mild to moderate pain. Nevertheless, 56% of respondents indicated that changes in mental health status as a result of a new HIV control regimen would be very bothersome or unacceptable (Supplementary Fig. S5). When data were disaggregated by gender, cisgender men appeared more willing to undergo procedures that would cause mild to moderate pain compared with cisgender and transgender women (p = .001). Cisgender and transgender women were more likely to find that having injections/infusions every other week for several months (p = .027), pain (p < .001), and changes in physical appearance (p < .001) were unacceptable or very bothersome trade-offs compared with cisgender men (Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

Acceptability of factors under a new HIV remission strategy compared with experiences with standard HIV medications, by gender/sex (United States, 2018). Percentages on the left reflect the sum of “unacceptable” and “very bothered” by the factor of the new HIV remission strategy compared with experience with standard HIV medications. Percentages on the right reflect the sum of “not bothered” and “somewhat bothered” by the factor of the new HIV remission strategy compared with experience with standard HIV medications. Excludes two respondents who did not specify their gender. n = 80–81 for cis and trans women. n = 138 for cis men. No transgender men participated in the survey. Asterisks indicate the remission strategies for which the differences in percentages of choosing “not bothered”/“somewhat bothered” or “unacceptable”/“very bothered” are statistically significantly different for cis and trans women than for cis men: **p < .01, *p < .05.

Bivariate results

HIV control strategies

Using bivariate analyses, we explored respondent characteristics correlated with choices between daily HIV medications versus long-acting ART versus new ART-free HIV remission. Tables 4 and 5 list the ORs of results that were statistically significant at the 0.05 level. Cisgender and transgender women were more likely (OR = 2.0) to prefer switching to a 6-month long-acting ART regimen but were less likely (OR = 0.5) to prefer a new HIV remission strategy, compared with cisgender men. Respondents with postgraduate education, full-time jobs, and/or higher household income levels were significantly more likely to prefer a new HIV remission strategy over other options compared with respondents without those characteristics. Age, race/ethnicity, partnership status, financial status, time since first exposure to HIV, time living with HIV, and current health status were not significantly correlated with preferred choice of HIV control strategy. Respondents who were taking ART twice or more frequently per day were more likely (OR = 3.6–4.0) to choose 1- or 2-month long-acting ART regimens as their preferred choice of HIV control strategies compared with respondents who took once-daily ART. Preference for HIV control strategy was not correlated with the number of ART pills taken daily, whether the timing of ART was affected by food or other drugs, presence of side effects of current ART, self-assessed attitude toward trying an alternative HIV therapy, or previously volunteering for HIV treatment or HIV remission studies.

Table 4.

Bivariate Results: Sociodemographic Characteristics That Are Statistically Significantly Correlated (p < .05) with Preferred Choice of HIV Control Strategy (United States, 2018)

| |

Preferred choice of strategy to control HIV (mutually exclusive) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Prefer current, daily pill version of HIV medication over all other options | Prefer long-acting injectable or implantable form of HIV medication that lasts for 1 month over all other options | Prefer long-acting injectable or implantable form of HIV medication that lasts for 2 months over all other options | Prefer long-acting injectable or implantable form of HIV medication that lasts for 6 months over all other options | Prefer new HIV remission strategy over all other options |

| Gender | Cis and trans women (OR = 2.01) more likely to prefer this strategy than cis men | Cis and trans women (OR = 0.46) less likely to prefer this strategy than cis men | |||

| Education | Doctorates (OR = 0.20) and 4-year college graduates (OR = 0.36) less likely to prefer this strategy than high-school graduates | Doctorates (OR = 8.75) and Masters (OR = 5.48) more likely to prefer this strategy than high-school graduates | |||

| Region | Midwesterners (OR = 6.02) more likely to prefer this strategy than Northeasterners | ||||

| Household income | $25k–$50k group (OR = 0.07) less likely to prefer this strategy than <$15k group | $50k–$75k group (OR = 3.82) and >$100k group (OR = 3.47) more likely to prefer this strategy than <$15k group | |||

| Income source | People with a regular, part-time job (OR = 2.75) more likely to prefer this strategy than those without | People with a regular, full-time job (OR = 2.15) more likely to prefer this strategy than those without | |||

Age, race, ethnicity, partnership status, financial status, time since first exposure to HIV, time living with HIV, and health status are not statistically significantly correlated with preferred choice of HIV control strategy.

OR, odds ratio.

Table 5.

Bivariate Results: Current HIV Medication-Taking Characteristics That Are Statistically Significantly Correlated (p < .05) with Preferred Choice of HIV Control Strategy (United States, 2018)

| |

Preferred choice of strategy to control HIV (mutually exclusive) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Prefer current, daily pill version of HIV medication over all other options | Prefer long-acting injectable or implantable form of HIV medication that lasts for 1 month over all other options | Prefer long-acting injectable or implantable form of HIV medication that lasts for 2 months over all other options | Prefer long-acting injectable or implantable form of HIV medication that lasts for 6 months over all other options | Prefer new HIV remission strategy over all other options |

| Frequency of taking ART pills or tablets | Taking pills twice or more daily (OR = 3.95) more likely to prefer switching to this strategy than those taking pills only once | Taking pills twice or more daily (OR = 3.57) more likely to prefer switching to this strategy than those taking pills only once | |||

| Attitude toward current ART medication | People feeling grateful for ART medication for keeping them healthy (OR = 0.45) less likely to prefer switching to this strategy than those not feeling the same way about ART medication | ||||

| Remembering to take current ART medication | People having trouble remembering to take ART medication on time (OR = 3.97) more likely to prefer staying with current HIV medication than those not having trouble remembering to take medication on time | ||||

| Willingness to try HIV remission to avoid long-term consequences of HIV treatment | People willing to try HIV remission strategy (OR = 0.03) less likely to prefer staying with current HIV medication than those not | ||||

Number of ART pills or tablets taken per day, whether timing of ART is affected by food or other drugs, presence of side effects of current ART, self-assessed attitude toward trying an alternative HIV therapy, and previous volunteering for HIV treatment or HIV cure studies are not statistically significantly correlated with preferred choice of HIV control strategy.

Scenario choices

We conducted bivariate analyses on preferences for switching from oral daily ART to new HIV remission strategies under seven scenarios. Statistically significant results are summarized in Tables 6 and 7. Age, partnership status, time since first exposure to HIV, time living with HIV, and health status were not significantly correlated with increased likelihood of switching to a new HIV remission strategy in any of the seven scenarios. Under various scenarios listed in Tables 6 and 7, cisgender and transgender women, nonwhites/Caucasians, people with higher educational attainment, and people with higher incomes were less willing to switch to new HIV remission strategies compared with respondents without those characteristics.

Table 6.

Bivariate Results: Sociodemographic Characteristics That Are Statistically Significantly Correlated (p < .05) with Increased Likelihood to Switch to a New HIV Remission Strategy in Scenarios 1–7

| |

Increased likelihood of choosing new HIV remission strategy over standard daily ART if… |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | No more daily pills, but must go to lab/clinic much more often (e.g., every 2 weeks) [Scenario 1] | No more daily pills, but very small increase in chance of passing HIV on to sex partner [Scenario 2] | New strategy causes worse side effects initially but went away eventually [Scenario 3] | Never take HIV medications again, but very small increase in risk of health problems (e.g., cancer) [Scenario 4] | Uncertainty of new strategy working, but need to stop taking the HIV medication to find out [Scenario 5] | New strategy might not increase life expectancy [Scenario 6] | New strategy might not increase quality of life [Scenario 7] |

| Gender | Cis and trans women (OR = 0.44) less likely to choose HIV remission than cis men | Cis and trans women (OR = 0.53) less likely to choose HIV remission than cis men | Cis and trans women (OR = 0.59) less likely to choose HIV remission than cis men | Cis and trans women (OR = 0.54) less likely to choose HIV remission than cis men | |||

| Race/ethnicity | African Americans (OR = 0.52) less likely to choose HIV remission than whites/Caucasians | African Americans (OR = 0.47) less likely to choose HIV remission than whites/Caucasians | Mixed race (OR = 0.26) less likely to choose HIV remission than whites/Caucasians | Hispanic or Latino/a (OR = 0.45) less likely to choose HIV remission than non-Hispanic and non-Latino/a | |||

| Education | Some college education (OR = 0.33), 4-year college graduates (OR = 0.19), Master's (OR = 0.18), and Doctorates (OR = 0.10) less likely to choose HIV remission than high-school graduates | Some college education (OR = 0.40), 4-year college graduates (OR = 0.34), and Master's (OR = 0.39) less likely to choose HIV remission than high-school graduates | |||||

| Region | Southerners (OR = 2.37) and Westerners (OR = 2.29) more likely to choose HIV remission than Northeasterners | Midwesterners (OR = 2.50), Southerners (OR = 2.69), and Westerners (OR = 2.34) more likely to choose HIV remission than Northeasterners | Southerners (OR = 2.42) more likely to choose HIV remission than Northeasterners | ||||

| Household income | $75k–$100k group (OR = 0.24) and >$100k group (OR = 0.30) less likely to choose HIV remission than <$15k group | $15k–$25k group (OR = 0.29) less likely to choose HIV remission than <$15k group | |||||

| Income source | Receiving government support (OR = 1.97) more likely to choose HIV remission than those without | ||||||

| Financial status | Able to pay expenses and has savings (OR = 0.36) less likely to choose HIV remission than those rarely able to pay expenses | ||||||

Age, partnership status, time since first exposure to HIV, time living with HIV, and health status are not statistically significantly correlated with increased likelihood of switching to new HIV remission strategy in scenarios 1–7.

Table 7.

Bivariate Results: Current HIV Medication-Taking Characteristics That Are Statistically Significantly Correlated (p < .05) with Increased Likelihood to Switch to a New HIV Remission Strategy in Scenarios 1–7

| |

Increased likelihood of choosing new HIV remission strategy over standard daily ART if… |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | No more daily pills, but must go to lab/clinic much more often (e.g., every 2 weeks) [Scenario 1] | No more daily pills, but very small increase in chance of passing HIV on to sex partner [Scenario 2] | New strategy causes worse side effects initially but went away eventually [Scenario 3] | Never take HIV medications again, but very small increase in risk of health problems (e.g., cancer) [Scenario 4] | Uncertainty of new strategy working, but need to stop taking the HIV medication to find out [Scenario 5] | New strategy might not increase life expectancy [Scenario 6] | New strategy might not increase quality of life [Scenario 7] |

| No. of ART pills or tablets taken per day | Taking 4+ daily pills (OR = 4.45) more likely to choose HIV remission than 0–1 daily pill-takers | Taking 2–3 daily pills (OR = 2.06) more likely to choose HIV remission than 0–1 daily pill-takers | |||||

| Frequency of taking ART pills or tablets | Taking pills twice or more daily (OR = 2.47) more likely to choose HIV remission than those taking pills only once | ||||||

| Attitude toward current ART medication | People worried about being able to afford and have access to medication (OR = 1.65) more likely to choose HIV remission than people not worried | People feeling that taking ART medication makes them feel in control of their lives (OR = 0.54) less likely to choose HIV remission than those not feeling the same way about ART medication | |||||

| Side effects of current ART medication | Have side effects that are not very bothersome (OR = 1.76) more likely to choose HIV remission than those without any side effects | Have side effects that are not very bothersome (OR = 1.88) more likely to choose HIV remission than those without any side effects | |||||

| Anxiety toward trying HIV remission not working | Feeling anxious (OR = 0.57) less likely to choose HIV remission than those not feeling anxious | Feeling anxious (OR = 0.59) less likely to choose HIV remission than those not feeling anxious | Feeling anxious (OR = 0.50) less likely to choose HIV remission than those not feeling anxious | ||||

| Anxiety toward side effects of HIV remission | Worried about side effects (OR = 0.61) less likely to choose HIV remission than those not worried | Worried about side effects (OR = 0.51) less likely to choose HIV remission than those not worried | Worried about side effects (OR = 0.56) less likely to choose HIV remission than those not worried | Worried about side effects (OR = 0.52) less likely to choose HIV remission than those not worried | Worried about side effects (OR = 0.47) less likely to choose HIV remission than those not worried | Worried about side effects (OR = 0.39) less likely to choose HIV remission than those not worried | Worried about side effects (OR = 0.38) less likely to choose HIV remission that those not worried |

| Willingness to try HIV remission to avoid long-term consequences of HIV treatment | People willing (OR = 12.29) more likely to choose HIV remission than those not willing | People willing (OR = 9.65) more likely to choose HIV remission than those not willing | People willing (OR = 3.22) more likely to choose HIV remission than those not willing | People willing (OR = 2.71) more likely to choose HIV remission than those not willing | |||

Whether timing of ART is affected by food or other drugs and remembering to take current ART medication on time are not statistically significantly correlated with increased likelihood of switching to new HIV remission strategy in scenarios 1–7.

Cisgender and transgender women expressed less willingness to switch to new HIV remission strategies if worse side effects temporarily existed (OR = 0.44), there were increases to their risk of developing health problems later in life (OR = 0.53), the new remission strategy required treatment interruption and its success was uncertain (OR = 0.59), or the new strategy might not increase quality of life (OR = 0.54). Respondents taking a higher quantity of pills daily expressed more willingness to switch to a new HIV remission strategy than to take fewer pills daily, even if the new strategy might increase the chance of passing HIV to a sexual partner (OR = 4.45) or lead to health problems later in life (OR = 2.06). Respondents who felt that daily ART made them feel in control of their lives were less likely to be willing to switch to a new HIV remission strategy if it required treatment interruption and if there was uncertainty in the new strategy working (OR = 0.54).

Respondents who reported anxiety about potential side effects of a new HIV remission strategy were less likely to be willing to switch compared with respondents who did not report being anxious under all seven scenarios (OR = 0.38–0.61). Conversely, respondents who were willing to try a new HIV remission strategy to avoid the long-term consequences of HIV treatment were more likely to be willing to switch to a new HIV remission strategy even if it would require more laboratory or clinic visits (OR = 12.29), lead to temporarily worse side effects (OR = 9.65), lead to health problems later in life (OR = 3.22), or have uncertainty in the new strategy working (OR = 2.71), compared with respondents who did not report willingness to try the new HIV remission strategy to avoid the consequences of long-term ART.

Supplementary Table S1 provides a summary of bivariate results for the willingness to switch to a new HIV remission strategy under the seven scenarios based on past participation in HIV-related trials and self-assessed willingness to try alternative HIV therapies. Respondents who had participated in past HIV treatment studies were more likely to be willing to switch to new HIV remission strategies under nearly all scenarios (OR = 1.82–2.72).

Multivariate results

HIV control strategies

Results of the multinomial logit model are presented in Table 8. Respondents who were more motivated by the potential benefits of HIV remission trials showed more willingness to switch from daily oral ART to a new HIV remission strategy or to long-acting ART. Respondents who were more averse to the potential risks of HIV remission research were less likely to select a new HIV remission strategy over oral daily ART. Each percentage point increase in the relative benefit inclination score was associated with an average of 1.07–1.08 in the relative risk ratios of choosing long-acting ART injectables/implantables or of choosing a new HIV remission strategy over daily pills, respectively, controlling for various variables listed in the tables (ceteris paribus). Each percentage point increase in the relative risk aversion score was associated with a mean relative risk ratio of 0.93 for choosing a new HIV remission strategy over daily pills, controlling for other variables. Risk-averse respondents were also less likely to select long-acting ART compared with risk-seeking respondents, but the association was not statistically significant at the 0.05 level (p = .086).

Table 8.

Multinomial Logit Regression Model on Choosing Between Daily Pill Version of Antiretroviral Therapy Versus Long-Acting Injectable (LAI) Versus a New HIV Remission Strategy (United States, 2018)

| Selecting LAI over daily pill version of ART |

Selecting remission strategy over daily pill version of ART |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relative risk ratio | p | 95% CI | Relative risk ratio | p | 95% CI | |

| Relatively more risk averse than other participants | 0.96 | .086 | 0.92–1.01 | 0.93a | .005 | 0.89–0.98 |

| Relatively more motivated by benefits than other participants | 1.07a | .004 | 1.02–1.12 | 1.08a | .002 | 1.03–1.14 |

| Cis or trans woman (vs. cis man) | 1.02 | .981 | 0.13–7.86 | 0.72 | .778 | 0.08–6.92 |

| Age | 0.97 | .551 | 0.89–1.06 | 0.96 | .380 | 0.86–1.06 |

| African American/black (vs. Caucasian/white) | 3.48 | .435 | 0.15–79 | 2.51 | .592 | 0.09–72 |

| Other race (vs. Caucasian/white) | 1.66 | .717 | 0.11–26 | 0 | .989 | |

| Hispanic | 0.37 | .495 | 0.02–6.30 | 0.72 | .828 | 0.04–14.09 |

| Some college or 2-year degree (vs. high school diploma) | 2.73 | .458 | 0.19–39 | 10.45 | .162 | 0.39–281 |

| 4-year college degree (vs. high school diploma) | 6.74 | .221 | 0.32–143 | 21.05 | .103 | 0.54–822 |

| Master's or Doctorate degree (vs. high school diploma) | 17.58 | .174 | 0.28–1,096 | 156.11b | .031 | 1.58–15,464 |

| Married or living with a partner | 2.37 | .463 | 0.24–24 | 4.12 | .261 | 0.35–49 |

| Annual household income exceeds $50,000 | 0.61 | .746 | 0.03–12 | 1.85 | .712 | 0.07–48 |

| Midwest (vs. Northeast) | >1,000 | .989 | >1,000 | .990 | ||

| South (vs. Northeast) | 9.57 | .091 | 0.70–131 | 3.23 | .414 | 0.19–54 |

| West (vs. Northeast) | 2.12 | .535 | 0.20–23 | 0.85 | .906 | 0.06–12 |

| Has a regular, full-time job (vs. no job) | 4.71 | .244 | 0.35–64 | 5.59 | .242 | 0.31–100 |

| Has a regular, part-time job (vs. no job) | 3.16 | .422 | 0.19–52 | 0.18 | .360 | 0–7.05 |

| Mostly able to pay expenses but late (vs. unable to pay expenses) | 0.21 | .386 | 0.01–7.14 | 0.03 | .079 | 0–1.47 |

| Able to pay expenses, no savings (vs. unable to pay expenses) | 0.40 | .608 | 0.01–13 | 0.12 | .259 | 0–4.72 |

| Able to pay expenses, has savings (vs. unable to pay expenses) | 0.41 | .670 | 0.01–26 | 0.02 | .082 | 0–1.64 |

| Percentage of lifetime living with HIV or AIDS diagnosis | 0.57 | .825 | 0–80 | 1.14 | .962 | 0–278 |

| Self-assessed health status is in the poorest quartile of participants | 3.38 | .340 | 0.28–41 | 6.95 | .165 | 0.45–107 |

| Volunteered for an HIV treatment trial in the past | 0.58 | .676 | 0.05–7.37 | 1.47 | .776 | 0.1–21 |

| Only 0 or 1 pill or tablet of HIV medication per day (vs. more) | 1.89 | .533 | 0.25–14 | 1.87 | .583 | 0.2–17 |

| Take HIV medication two or more times per day (vs. once/never) | 6.05 | .380 | 0.11–338 | 2.25 | .708 | 0.03–157 |

| HIV medication timing is affected by food/other drugs | 5.01 | .142 | 0.58–43 | 7.54 | .085 | 0.76–75 |

| Current HIV medication causes side effects | 2.59 | .363 | 0.33–20 | 1.52 | .708 | 0.17–14 |

n = 153. p = 0.0037. Pseudo R2 = 0.3296.

The listed coefficients indicate the relative risk ratio of each variable associated with selecting long-acting ART injectables over daily ART (left columns) and the relative risk ratio of each variable associated with selecting a new HIV remission strategy over daily pill version of ART (right columns).

Statistically significant at 1% level.

Statistically significant at 5% level.

CI, confidence interval; LAI, long-acting injectable.

Scenario choices

Results of the seven ordered logistic models are presented in Table 9. The listed coefficients indicate the ORs of each variable associated with an increased willingness to switch to the new remission strategy under each given scenario. Respondents with higher relative benefit inclination scores were more likely (ORs range 1.01–1.04) to be willing to switch to remission over oral daily ART under six of the seven scenarios. There was no statistically significant association in the scenario where the remission strategy might not increase life expectancy. Furthermore, respondents more averse to the potential risks of HIV remission research were less likely (ORs range 0.96–0.98) to be willing to switch to a new remission strategy over oral daily ART under all seven scenarios compared with people with lower relative risk aversion scores.

Table 9.

Ordered Logistic Regression Models on Higher Likelihood to Choose a New HIV Remission Strategy Over Standard Daily ART Under Scenarios 1–7 (United States, 2018)

| |

Increased likelihood of choosing remission strategy over daily ART if… |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No more daily pills, but must go to lab/clinic much more often (e.g., every 2 weeks) [Scenario 1] | No more daily pills, but very small increase in chance of passing HIV on to sex partner [Scenario 2] | New strategy causes worse side effects initially but went away eventually [Scenario 3] | Never take HIV medications again, but very small increase in risk of health problems (e.g., cancer) [Scenario 4] | Uncertainty of new strategy working, but need to stop taking the HIV medication to find out [Scenario 5] | New strategy might not increase life expectancy [Scenario 6] | New strategy might not increase quality of life [Scenario 7] | |

| Relatively more risk averse than other participants | 0.97a [0.96–0.99] | 0.97a [0.96–0.99] | 0.97a [0.95–0.98] | 0.96a [0.95–0.98] | 0.97a [0.95–0.98] | 0.98a [0.96–0.99] | 0.96a [0.95–0.98] |

| Relatively more motivated by benefits than other participants | 1.04a [1.02–1.05] | 1.02b [1.00–1.03] | 1.03a [1.02–1.05] | 1.02a [1.01–1.03] | 1.01b [1.00–1.03] | 1.01 | 1.02a [1.00–1.03] |

| Cis or trans woman (vs. cis man) | 1.29 | 0.90 | 0.55 | 0.95 | 0.90 | 0.65 | 0.53 |

| Age | 0.99 | 1.02 | 0.97b [0.94–1.00] | 0.98 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.97b [0.94–1.00] |

| African American/black (vs. Caucasian/white) | 1.83 | 1.07 | 0.58 | 0.58 | 0.50 | 1.12 | 1.37 |

| Other race (vs. Caucasian/white) | 0.95 | 1.26 | 0.56 | 0.84 | 0.83 | 0.49 | 0.45 |

| Hispanic | 1.05 | 0.69 | 0.78 | 1.09 | 0.73 | 0.65 | 0.52 |

| Some college or 2-year degree (vs. high school diploma) | 0.30b [0.10–0.93] | 0.44 | 2.67 | 1.32 | 2.07 | 1.97 | 1.88 |

| 4-year college degree (vs. high school diploma) | 0.21b [0.06–0.70] | 0.38 | 0.88 | 1.56 | 0.94 | 1.14 | 1.47 |

| Master's or Doctorate degree (vs. high school diploma) | 0.33 | 1.01 | 2.45 | 5.21b [1.39–19.56] | 1.73 | 2.82 | 3.34 |

| Married or living with a partner | 1.34 | 0.76 | 0.71 | 1.14 | 0.70 | 0.72 | 0.70 |

| Annual household income exceeds $50,000 | 0.73 | 0.70 | 4.48a [1.73–11.57] | 1.98 | 1.32 | 1.60 | 2.37 |

| Midwest (vs. Northeast) | 1.44 | 1.15 | 1.44 | 1.14 | 0.96 | 1.51 | 1.25 |

| South (vs. Northeast) | 2.37 | 1.83 | 2.31 | 1.78 | 1.58 | 3.01b [1.16–7.76] | 1.97 |

| West (vs. Northeast) | 1.79 | 1.26 | 1.89 | 1.41 | 0.82 | 2.03 | 1.49 |

| Has a regular, full-time job (vs. no job) | 1.12 | 0.75 | 0.82 | 0.82 | 1.84 | 0.89 | 0.59 |

| Has a regular, part-time job (vs. no job) | 0.68 | 0.42 | 1.28 | 0.41 | 1.09 | 0.68 | 0.83 |

| Mostly able to pay expenses but late (vs. unable to pay expenses) | 0.91 | 0.60 | 1.02 | 0.90 | 1.51 | 1.59 | 2.49 |

| Able to pay expenses, no savings (vs. unable to pay expenses) | 0.81 | 0.84 | 1.31 | 1.20 | 1.53 | 1.69 | 2.26 |

| Able to pay expenses, has savings (vs. unable to pay expenses) | 0.84 | 1.31 | 1.19 | 0.66 | 1.13 | 2.04 | 1.99 |

| Percentage of lifetime living with HIV or AIDS diagnosis | 0.23 | 0.11b [0.02–0.70] | 0.94 | 0.13b [0.02–0.80] | 0.59 | 0.84 | 0.68 |

| Self-assessed health status is in the poorest quartile of participants | 1.05 | 0.78 | 0.94 | 2.10 | 0.87 | 1.67 | 1.37 |

| Volunteered for an HIV treatment trial in the past | 0.77 | 1.26 | 2.47b [1.08–5.65] | 1.90 | 2.55b [1.19–5.49] | 3.10a [1.44–6.67] | 3.68a [1.66–8.15] |

| Only 0 or 1 pill or tablet of HIV medication per day (vs. more) | 0.63 | 1.16 | 0.95 | 0.37b [0.17–0.83] | 0.67 | 1.14 | 1.03 |

| Take HIV medication two or more times per day (vs. once/never) | 1.23 | 4.69a [1.60–13.76] | 0.76 | 0.92 | 0.57 | 0.99 | 1.06 |

| HIV medication timing is affected by food/other drugs | 0.93 | 1.58 | 1.44 | 2.22b [1.13–4.37] | 0.90 | 0.47b [0.23–0.94] | 0.70 |

| Current HIV medication causes side effects | 0.65 | 0.42b [0.20–0.88] | 0.75 | 0.63 | 0.68 | 0.55 | 0.79 |

| n = | 168 | 167 | 168 | 170 | 170 | 168 | 167 |

| p = | .0000 | .0008 | .0000 | .0000 | .0004 | .0015 | .0001 |

| Psuedo R2 = | 0.1483 | 0.1111 | 0.1557 | 0.1323 | 0.1084 | 0.1012 | 0.1223 |

Numbers in square brackets are the 95% CI of coefficients that are statistically significant at the 5% level.

Statistically significant at 1% level.

Statistically significant at 5% level.

Perceptions of specific potential risks, benefits, or improvements offered by HIV remission research

Relative risk ratios of key independent variables that were statistically significant are summarized in Supplementary Tables S2, S3, S4, S5, S6, S7.

Discussion

Our study provides insights into what adults living with HIV in the United States perceive as meaningful improvements over oral daily ART, as well as possible desirable product characteristics for future HIV treatment and remission options. Our study extends the social sciences literature on HIV remission research by empirically exploring preferences for long-acting ART formulations and ART-free HIV remission strategies versus oral daily ART, as well as preferences for potential product characteristics and acceptable trade-offs for various HIV therapeutic scenarios. Scholars have underscored the importance of exploring the acceptability of emerging biomedical products to better align product development with end-user perspectives.24,25 Forward-looking, patient-centered HIV drug development will necessitate greater knowledge of diverse PLWHIV's preferences for novel HIV therapeutic options.11 To that end, an additional strength of our research is that our sample of PLWHIV showed more diversity with respect to gender and ethnicity when compared with previous U.S.-based surveys.22,23

An important finding was that 42% of respondents would be willing to switch from oral daily ART to long-acting ART injectables or implantables taken at 6-month intervals, corresponding to the biannual frequency of clinic visits for most PLWHIV in the United States. Currently, only monthly and bimonthly long-acting formulations have been studied in clinical research, yet they have shown high acceptability and satisfaction rates among participants taking long-acting ART. For example, of the participants who switched to the long-acting CAB/RPV regimen in the Antiretroviral Therapy as Long Acting Suppression (ATLAS) 48-week study, 97% preferred monthly administration over previous oral daily ART.26

A separate qualitative study nested in a Phase IIb CAB/RPV trial conducted in the United States and Spain found that long-acting injectable ART regimens were highly desirable from the perspective of PLWHIV because they reduced internalized stigma, offered convenience, and peace of mind.9 Furthermore, that study found that the intermittent dosing of the long-acting ART formulation would appear to alleviate some of the anxiety associated with being completely off ART. However, these results differed from those of a recent study conducted among racial/ethnic minorities in North and South Carolina, in which respondents had the least interest in biannual ART implants. Rather, in that study, PLWHIV expressed greatest interest in switching to oral ART regimens taken once weekly (66% very interested), followed by monthly ART injections (39% very interested) and biannual ART implants (5% very interested).11

Our survey represented a larger U.S. sample of PLWHIV across multiple states, although our respondents may have skewed toward those with an interest in advancing HIV therapies. These discrepant results underscore the importance of ascertaining potential users' perspectives in different populations to ensure that HIV control strategies can meet diverse patient needs.

Undoubtedly, switching HIV control regimens would be a critical decision for PLWHIV.20 Decisions to test or try novel HIV therapies cannot be dissociated from the impact of HIV on daily life and experiences with current and past HIV medications.27,28 PLWHIV make careful risk/benefit calculations based on their perceived health status and therapeutic options.16 For example, respondents who rated the potential trade-offs of new HIV remission strategies as very bothersome were less likely to be willing to choose any of the new HIV remission strategies than respondents who did not. Respondents who took ART at least twice daily were more likely than respondents taking ART once daily to choose the 1- or 2-month long-acting ART injectable/implantable as their first choice. Furthermore, our multivariate data reveal that respondents with higher relative risk aversion would be less likely to switch to alternative HIV control options. Researchers and HIV care providers should pay close attention to patients' risk tolerance for being on/off ART and side effects before proposing a switch to new HIV therapeutic or research options.

An important concern for PLWHIV is the potential to transmit HIV to a sexual partner during an analytical treatment interruption and/or an unsuspected rebound of viremia.16,27 As noted in our survey, nearly 60% of respondents stated they would be unlikely to switch to a new HIV remission strategy if there were a very small increase in the risk that they could transmit HIV to a partner. This result is consistent with our previous research, which demonstrated that the fear of transmitting HIV remains one of the most important deterrents for HIV remission research and interrupting ART.16,27 Relatedly, 59% of survey respondents viewed increased confidence that they would not pass HIV to others as a significant life-changing improvement. This finding is important, because the field of biomedical HIV remission research is shifting toward less restrictive analytical treatment interruptions and prolonged periods of viremia to test promising interventions, particularly those mediated by the immune system.29

PLWHIV willing to undergo analytical treatment interruptions may feel a tension between their altruistic desires to advance HIV remission science and the need to protect their sexual partners and themselves. We suspect survey respondents' desire to stay virally suppressed was influenced by the widespread public health campaign of “Undetectable = Untransmittable,” which has publicized the scientific evidence associating durable viral suppression (undetectable) with the lack of HIV sexual transmission (untransmittable).30 Findings also underscore the need to provide adequate protection measures for sexual partners of those undergoing analytical treatment interruptions (e.g., appropriate counseling, PrEP referral or provision, and HIV testing).29

Interestingly, in our study, the most desirable attribute of a potential HIV remission strategy was the complete elimination of HIV from the body. This finding is consistent with focus group results conducted throughout the United States in which most PLWHIV conceived of a cure/remission as complete removal of HIV.28,31 In these focus groups, many PLWHIV did not view “functional cure” as a meaningful improvement over ART-controlled HIV due to the possibility of viral rebound.28,31 It will be important to manage community expectations17 and integrate biomedical research possibilities with what PLWHIV would find most valuable in terms of HIV therapy and cure/remission.28

Our study revealed important differences in motivations and preferences across gender and other sociodemographic characteristics that may be actionable as part of research recruitment efforts. For example, cisgender and transgender women were more likely to be motivated by engaging with research teams, having regular access to a study nurse, being financially compensated, and receiving support for transportation. Furthermore, cisgender and transgender women were more likely than cisgender men to choose injectable or implantable ART lasting at least 6 months above all other options, consistent with preferences for delivery of contraceptive and HIV PrEP options among women in the United States and worldwide.32,33 Cisgender and transgender women were also less likely than cisgender men to choose a new HIV remission strategy, consistent with our 2015 survey that showed women were less willing to participate in most types of HIV remission studies.22 More empirical research will be needed to ascertain the reasons behind these gender differences in preferences.

Our survey further revealed possible psychosocial factors that could mediate willingness to switch from oral daily ART to long-acting ART or HIV remission. The fear of developing dementia or having difficulty thinking was the most prevalent (63%) deterrent to participation in HIV remission research. Possible unacceptable psychosocial risks associated with HIV remission research remain largely unexplored in the literature, particularly regarding anxiety induced by discontinuing ART for a prolonged period. Conversely, psychosocial benefits of contributing to HIV remission science were the most significant motivators to participation in research, consistent with previous sociobehavioral research on HIV remission16,22,34 and the HIV prevention and treatment literature.35 Altruistic benefits to participation in the context of HIV remission research need to be better characterized. It is possible that altruism is mixed with the desire for personal benefits, as evidenced by our survey findings and similar prior research.20,22

Survey results can inform community engagement, education, recruitment, and retention approaches for upcoming long-acting ART implementation and the field of HIV remission research. A nuanced understanding of patient preference heterogeneity can guide meaningful community and stakeholder engagement, enhance patient/participant and clinician-research communication, and contribute to a more successful and inclusive product development process.22 Acceptability research should become a critical adjunct to ongoing biomedical research efforts aimed at improving long-acting ART regimens, aiming for remission, and ultimately finding a cure for HIV.25

To make informed decisions around evolving HIV therapeutic and research options, PLWHIV may benefit from having decision tools and educational materials to better assess possible risks, benefits, and trade-offs.36 For example, fact sheets, infographics, instructional videos, HIV treatment planners, and reminder systems and pocket cards could be created to facilitate future decision-making. More research is also needed on how to best support PLWHIV in making decisions around evolving HIV treatment and research options. Once PLWHIV begin using long-acting ART injectables or implantables, it may be more difficult for them to enroll in HIV remission trials involving analytical treatment interruptions due to the prolonged pharmacokinetic trial of ART.

Involvement in HIV remission trials may also mean participants will be excluded from future studies if, for instance, they develop resistance to the tested interventions. Efforts should be made to better understand opportunity costs and communicate these to patients/participants. HIV care providers and biomedical HIV cure/remission researchers also need to build trust with PLWHIV to understand their preferences, communicate risks and benefits, and involve them in shared decision-making.11,37

Our study has several limitations that must be acknowledged. First, our questions were hypothetical and relied on stated preferences. It remains to be seen which choice PLWHIV would make if a real-life opportunity presented itself to change one's HIV control options. Switching from an oral daily ART regimen to a new ART-free HIV remission option may be a much bigger leap than switching to long-acting ART. Results may not be helpful in predicting enrollment or uptake rates; however, responses can inform community engagement and education, study designs, informed consent, and recruitment efforts. Second, the sample may have been biased toward respondents with access to HIV treatment and cure/remission listservs and the Internet.

The sample was likely not representative of PLWHIV in the United States because individuals without Internet, non-English speakers, and minors were not included, limiting generalizability. However, our sample had proportionally more cisgender and transgender women and was racially and ethnically more diverse than previous U.S. surveys.22,23 Nevertheless, our sample included a very small number of transgender women, meaning that aggregate data for women likely reflect the responses of cis women. Furthermore, characteristics such as age, gender, HIV status, and location were self-reported, so it is difficult to confirm the accuracy of the responses. Third, recruitment materials referenced advancing social sciences related to HIV treatment and cure/remission research; thus, the sample may have been skewed toward individuals interested in improving HIV therapeutics and finding an HIV cure. The complexity of the survey questions may have limited participants' full comprehension, although we mitigated this risk by providing definitions of key concepts in lay terms and having community members thoroughly review our survey.

We did not assess the entirety of possible product characteristics that could influence patient preferences, such as cost. The simulated characteristics of HIV treatment and remission options may not represent actual profiles of therapies or remission strategies that ultimately will be made available to PLWHIV. We did not assess preferences toward specific HIV cure/remission strategies, as this was the object of our previous work.22 We did not ask about factors that would influence acceptability of analytical treatment interruptions, since the Treatment Action Group recently published a report on this topic.38 Instead, this survey focused on desirable product characteristics from the perspective of adults living with HIV in the United States. Finally, we did not delve into possible implementation issues related to long-acting ART or HIV remission.

The above limitations notwithstanding, our survey used a rigorous approach to identify desirable characteristics for evolving HIV treatment and remission options from the perspectives of PLWHIV in the United States. Similar research should be conducted in resource-limited settings, where long-acting ART and HIV remission regimens may fill a truly unmet need for PLWHIV who do not have access to daily oral ART regimens. A 2017 systematic review of national HIV care continua and progress on achieving the 90-90-90 UNAIDS targets revealed that, of the 53 countries with data, representing ∼54% of the global estimates of PLWHIV, the average proportion of PLWHIV on ART was 48%, while only 40% were virally suppressed.39 Thus, the utility of novel HIV therapies may be greatest in settings where barriers exist around antiretroviral access and daily adherence. Survey findings could also be enhanced by qualitative data collection methods to delve deeper into reasons behind PLWHIV's preferences for various options. More research should also be directed toward what HIV care providers would perceive as improvements above oral daily ART.40,41

Table 10 provides a summary of key findings and possible implications and considerations for HIV treatment and remission research.

Table 10.

Summary of Findings and Possible Implications for HIV Treatment and Cure/Remission Research

| Summary of findings | Possible implications |

|---|---|

| • 42% of respondents would be willing to switch from oral daily ART to long-acting ART injectables or implantables taken at 6-month intervals. • 24% of respondents who would prefer a new ART-free HIV remission strategy. |

• A variety of therapeutic options should be provided to PLWHIV in the future. |