Abstract

Social hierarchies emerged during evolution, and social rank influences behavior and health of individuals. However, the evolutionary mechanisms of social hierarchy are still unknown in amniotes. Here we developed a new method and performed a genome-wide screening for identifying regions with accelerated evolution in the ancestral lineage of placental mammals, where mammalian social hierarchies might have initially evolved. Then functional analyses were conducted for the most accelerated region designated as placental-accelerated sequence 1 (PAS1, P = 3.15 × 10−18). Multiple pieces of evidence show that PAS1 is an enhancer of the transcription factor gene Lhx2 involved in brain development. PAS1s isolated from various amniotes showed different cis-regulatory activity in vitro, and affected the expression of Lhx2 differently in the nervous system of mouse embryos. PAS1 knock-out mice lack social stratification. PAS1 knock-in mouse models demonstrate that PAS1s determine the social dominance and subordinate of adult mice, and that social ranks could even be turned over by mutated PAS1. All homozygous mutant mice had normal huddled sleeping behavior, motor coordination and strength. Therefore, PAS1-Lhx2 modulates social hierarchies and is essential for establishing social stratification in amniotes, and positive Darwinian selection on PAS1 plays pivotal roles in the occurrence of mammalian social hierarchies.

Subject terms: Bioinformatics, Comparative genomics

Introduction

Social hierarchy characterizes the group structure of social animals and may affect individual behavior and health.1–3 Social hierarchy exists in numerous animals, including insects,4 chickens,5 mammals,6 and primates.7 A well-organized social system allows animals to adapt to a wide range of eco-systems.8 Many recent achievements were made in understanding the genetics of social hierarchies, especially in insects, and these lines of evidence have been carefully reviewed.4,9–12 However, it still remains unknown which genetic changes have resulted in the occurrence of social hierarchies in placental mammals, and whether there is a general genetic mechanism of modulating social hierarchies in amniotes.

The eutherian mammals (more commonly referred to as placental mammals) form one of the most successful groups among terrestrial vertebrates.13 The ancestors of placental mammals are shrew-like in appearance14,15 and very likely to be solitary-living (a breeding female forages independently in her home range and encounters a male only during mating),8 while the most living placental mammals are social. Thus a transition from solitary-living (nonsocial) to social system might have occurred in the ancestral lineage (the red branch in Fig. 1a) of placental mammals. Mammalian social hierarchy, as an important characteristic of well-organized social system, might have appeared during the transition. It is very likely that the emergence of mammalian social hierarchy systems was driven by positive Darwinian selection. Moreover, the placental mammal-specific traits also emerged in the same lineage, such as chorioallantoic placenta,16 longer gestation periods,16 shortened lactation and constant secretion of complex milk.17 Therefore, sequences with accelerated evolution (a signature of positive selection) in the ancestral lineage of placental mammals may be involved in the modulation of social hierarchy and the placental mammal-specific traits.

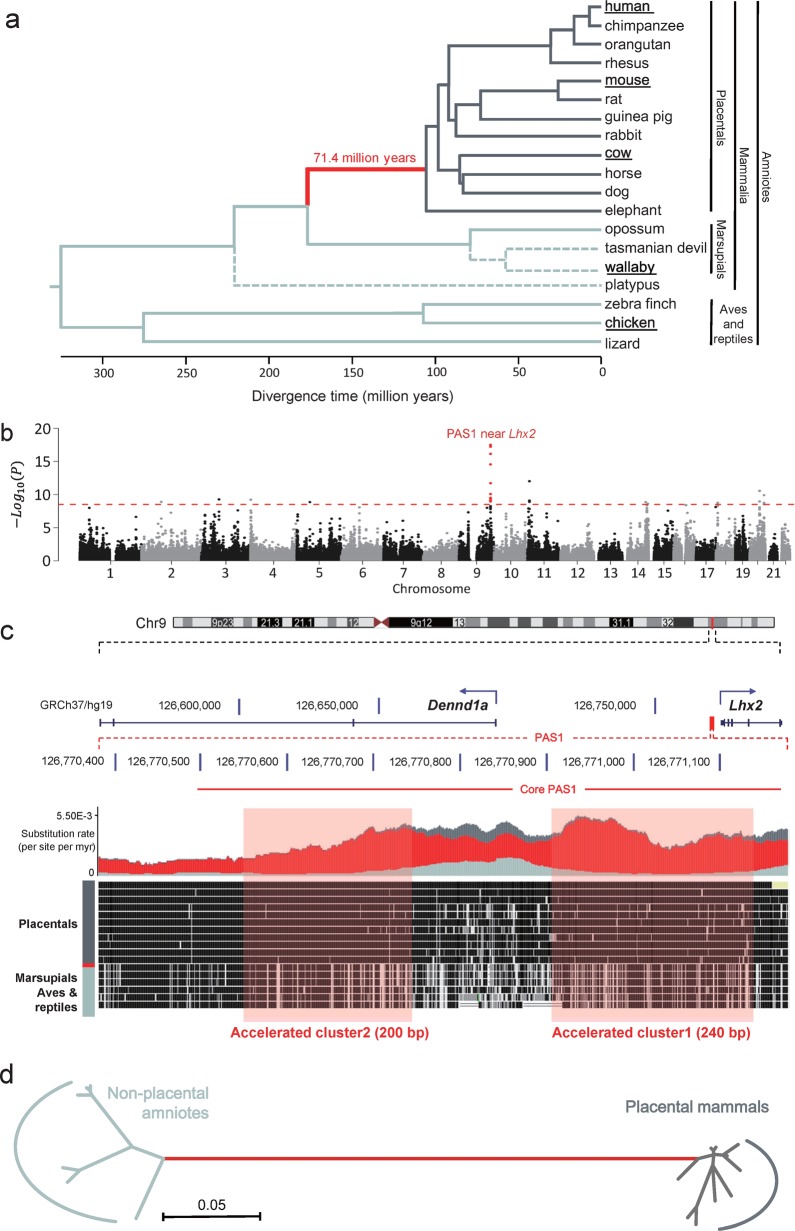

Fig. 1. Genome-wide screening for PASs.

a Phylogenetic tree of 19 amniotes for detecting PASs. The red branch indicates that mammalian social hierarchy systems might have emerged in the ancestral lineage of placental mammals. Sixteen amniotes linked by solid lines in the tree were used in the KFP test for accelerated evolution. Three other amniotes (Tasmanian devil, wallaby, and platypus) linked by dashed lines were included to validate the results of KFP test. Amniotes denoted with bold and underlined fonts were used for functional analyses. b Manhattan plot of KFP screening results. Results of genome-wide scan for sequences with accelerated evolution are shown in Manhattan plot of significance against human chromosomal locations. Each dot represents one window. The location of the windows with the highest signal is indicated in red. The dash line denotes the threshold of the test after Bonferroni correction. c Alignment of PAS1 nucleotide sequences of 19 amniotes. The locations of PAS1 regions containing clusters 1 and 2 with 11 significantly accelerated windows are shown. The evolutionary rates of PAS1 in the red (red), placental-specific (dark gray) and non-placental-specific (light gray) branches are shown in the middle panel. Coordinates of PAS1: human-hg19, chr9:126,770,367–126,771,183; mouse-mm9, chr2:38,203,254–38,204,076. Coordinates of core PAS1: human-hg19, chr9:126,770,494–126,771,174; mouse-mm9, chr2:38,203,382–38,204,067. d Unrooted neighbor-joining tree of the conjunction of the accelerated clusters 1 and 2. The evolutionary distances were computed using the Tajima-Nei method.72

To search for PASs (placental-accelerated sequences), a new method is necessary because the existed methods only detect the accelerated evolution on conserved and presumed functional regions.18–23 Moreover, a lack of consistency among the existed methods has been reported22 since there is only one human accelerated sequence commonly identified by these methods.18–22 Therefore, we developed a new method and the corresponding software Kung-Fu Panda (KFP) which compares the normalized observed evolutionary rate of the red branch with those of the non-red branches within each sliding window. The accelerated evolution was then determined by the Poisson probability. The varying evolutionary rate among lineages and the uncertainty of estimated divergence time have been considered. The KFP software can reliably, accurately and very rapidly screen the entire multi-genome alignments (including non-conserved and conserved sequences) and pinpoint accelerated regions.

After the genome-wide KFP screening for the PASs, functional analyses were carried out for the most accelerated region designated as placental-accelerated sequence 1 (PAS1) (Fig. 1b, c). PAS1 is a short non-coding region (about 700 bp) located near the LIM homeobox 2 (Lhx2) gene. Multiple lines of evidence showed that PAS1 is an enhancer and regulates the expression of Lhx2, but not other genes nearby, in the embryonic nervous system. PAS1s from various placental and non-placental amniotes affected the expression of a reporter gene differently in a neuroblastoma cell line. The amniotes PAS1 alleles were shown to genetically determine the social dominance of PAS1 knock-in adult mice. The social dominance and subordinate was even turned over by mutated PAS1. Moreover, social hierarchy could not be established in PAS1-null allele mice. This work highlights the importance of regulatory elements in the evolution of amniotes social hierarchies and provides the first evidence on which genetic changes have resulted in the occurrence of social hierarchies in placental mammals. This also sheds light on a highly debated issue about whether social dominance can be inherited.9,10

Results

Genome-wide screening for PASs

A phylogenetic tree of 16 amniotes (12 placental mammals, 1 marsupial, 2 aves, and 1 reptile) was constructed, and the length of each branch of the tree was determined (Fig. 1a; Supplementary information, Fig. S1a). The topology of the tree is the same as the neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree24 from whole-genome sequences of 16 amniotes, constructed with the eGPS software25 (Supplementary information, Fig. S1b). The red branch indicates that mammalian social hierarchies might have emerged in the ancestral lineage of placental mammals. The multi-genome alignments of the 16 amniotes were then scanned by the KFP software with a 100 bp sliding window and a sliding step of 20 bp. For each window, the possible ancestral status of each internal node was determined by the parsimony method.26 The evolutionary rate of each window in each branch was then calculated.

It is known that the genome-wide evolutionary rate varies among lineages,27,28 and that the uncertainty of estimated divergence time exists. These two factors act together since the effect of the underestimated divergence time is similar with that of the lifted genome-wide evolutionary rate, and vice versa. Therefore, a genome-wide normalization factor α was calculated for each branch, and the evolutionary rate of each window in each branch was rescaled. The normalized evolutionary rate of the window in the red branch was compared with that in the non-red branches (Fig. 1a), and then the red branch-specific accelerated evolution was tested according to the Poisson probability. A total of 3,269,214 windows were analyzed, and 28 significant windows (Supplementary information, Table S1, P < 3.06 × 10−9) were identified after Bonferroni correction29 for multiple tests (Fig. 1b). The syntenic alignments of the accelerated windows were examined manually, and these genomic regions bear the signature of accelerated evolution in the ancestral lineage of placental mammals.

PAS1 presents the most dramatically accelerated evolution (P = 3.15 × 10−18) in the ancestral lineage of placental mammals. PAS1 is composed of two accelerated clusters (eleven overlapped and accelerated windows) and their neighboring regions (Fig. 1c). The first cluster is about 160 bp downstream from the second cluster, and both are located upstream from the region encoding the major transcripts of Lhx2 (201–203), and in the first intron of the minor transcript Lhx2-204. To validate and visualize the accelerated evolution of PAS1, three other amniotes (Tasmanian devil, wallaby, and platypus) were included, and the evolutionary rate of PAS1 in the placental-specific, the red, and the non-placental-specific branches of the tree was calculated (Fig. 1c). The Track data hub30 and the 100-way vertebrate alignment track on the UCSC genome browser were used to confirm sequence substitutions in PAS1 that might have happened between the clades of placental mammals and marsupials-aves (Fig. 1c). Moreover, the neighbor-joining tree of PAS1 shows a very long red branch and that PAS1 is not (highly) conserved within the placental and non-placental clades (Fig. 1d). These lines of evidence confirm that PAS1 has experienced the accelerated evolution in the ancestral lineage of placental mammals, and the KFP method accurately pinpointed the PAS1 (about 700 bp) over the genome.

To further validate the new KFP method, the multi-genome alignments were re-analyzed when considering another set of divergence time estimated from nuclear genes.31 23 of 28 accelerated windows were successfully identified. After the lengths of the branches in the original tree (Fig. 1a) were randomly disturbed, all of the 28 accelerated windows were recovered by KFP. Moreover, after one (rabbit) or two (orangutan and dog) species were removed from the analyses, 27 or 23 of 28 accelerated windows were successfully identified, respectively. Notably, PAS1 remained to be the most accelerated region in all of the four validations. Therefore, these results demonstrate the robustness and the efficiency of the new KFP method.

Enhancer activity of PAS1 in the embryonic nervous system

The enhancer activity of PAS1 was then examined. Signals of cap analysis of gene expression (CAGE) were found on both sense and antisense strands of PAS1 in mouse brain samples (Fig. 2a), suggesting an enhancer activity of PAS1.32,33 PAS1 is located in a 22 kb region (mm9, chr2:38,194,000–38,216,000) with extensive H3K27ac signals in the mouse embryonic day 14.5 (E14.5) brain (Supplementary information, Table S1), which is a characteristic feature of super-enhancers.34 Moreover, H3K4me1, H3K27ac, and DNase I hypersensitive signals on PAS1 were found in the mouse embryonic brain but not in other embryonic tissues, and these signals were very low or nearly vanished in the brains of adult mice (Fig. 2a). These results suggest that PAS1 has an enhancer activity in the mouse embryonic brain.

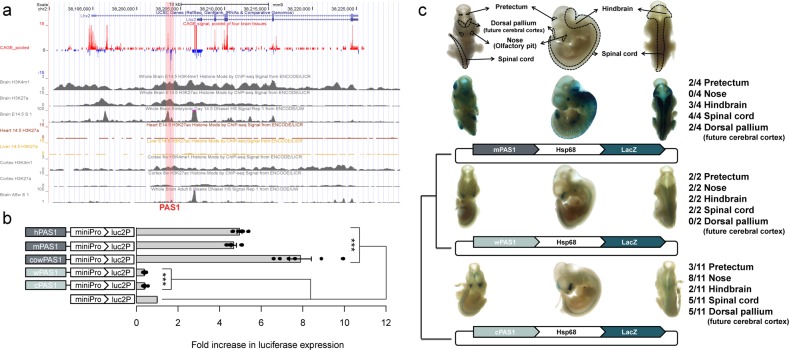

Fig. 2. Effects of PAS1s from various amniotes on reporter gene expression in mouse neuroblastoma cell line (Neuro2A) and embryonic nervous system.

a Epigenomic signals on PAS1 (pink box). The CAGE signals pooled from four mouse brain samples showed peaks in both sense (red) and antisense (blue) strands of PAS1. The data were obtained from FANTOM (http://fantom.gsc.riken.jp/).78,79 H3K4me1 and H3K27ac signals on PAS1 were seen in mouse embryonic brain samples, but not in embryonic heart and liver samples. All H3K4me1, H3K27ac, and DNase I hypersensitive signals on PAS1 in E14.5 mouse brain samples were higher than those in adult (8 weeks) mouse brain samples. b Cis-regulatory activity of PAS1s from various amniotes on reporter gene expression. The PAS1 elements from placental mammals, e.g., human (hPAS1), mouse (mPAS1) and cow (cowPAS1), enhanced, but those from wallaby (wPAS1) and chicken (cPAS1) suppressed the expression of the luciferase reporter gene (luc2P) in Neuro2A cells. The expression levels of the luciferase gene linked to PAS1 were normalized to those of the same gene driven by the minimal promoter (miniPro) without PAS1. Error bars represent the SEM of six biological replicates with three technical replicates for each experiment. One-tailed Student’s t-test, ***P < 0.001. c Effect of PAS1s from various amniotes on the expression of LacZ reporter gene in E11.5 mouse embryos. Locations of pretectum, dorsal pallium, primitive nose, primitive hindbrain, and spinal cord in ventral, lateral, and dorsal views are indicated. The denominator of the fraction on the right indicates the total number of LacZ-positive embryos obtained (Supplementary information, Fig. S2), and the numerator denotes the number of embryos with reproducible LacZ expression in a specific region of the embryo (Supplementary information, Fig. S2). Hsp68, a minimal promoter; LacZ, β-galactosidase gene.

To examine the cis-regulatory activity of PAS1s from various amniotes, a luciferase assay was conducted in a mouse neuroblastoma cell line (Neuro2A). Compared with the basal level of expression, PAS1s from representative placental mammals (i.e., hPAS1, mPAS1, and cowPAS1 from human, mouse, and cow, respectively) enhanced the expression of the luciferase reporter gene Luc2P driven by the minimal promoter more than 5 fold (Fig. 2b). In contrast, PAS1s from non-placental amniotes (i.e., wPAS1 and cPAS1 from wallaby and chicken, respectively) suppressed the expression of the reporter gene by more than 50%. This result suggests that the cis-regulatory activity of PAS1s in placental mammals is different from those in non-placental amniotes.

Transgenic mouse enhancer assays35 were then carried out to examine the enhancer activity of PAS1s in vivo. The activity of hPAS1, mPAS1, wPAS1, and cPAS1 was examined in the mouse embryos at embryonic day 11.5 (E11.5), which is a critical period for neural development. The activity of PAS1s is in accordance with the previously reported Lhx2 expression pattern in E11.5 mouse embryos.36,37 Results showed that hPAS1 and mPAS1 strongly and reproducibly enhanced the expression of the β-galactosidase (lacZ) reporter gene driven by the Hsp68 promoter in the pretectum, primitive hindbrain, and spinal cord (Fig. 2c; Supplementary information, Fig. S2). In contrast, wPAS1 and cPAS1 enhanced LacZ expression in the primitive nose, ventral hindbrain, and ventral spinal cord. In the roof of dorsal pallium (future cerebral cortex), hPAS1, mPAS1, and cPAS1 enhanced LacZ expression, but wPAS1 had no detectable enhancer activity.

As chickens and mice diverged more than 300 million years ago, the transgenic mouse enhancer assay may not be appropriate for investigating the enhancer activity of chicken PAS1 (cPAS1). Therefore, the enhancer activity of hPAS1 and cPAS1 was examined in the chicken embryos. Reporter plasmids were introduced into the primitive spinal cord of chicken embryos at Hamburger Hamilton (HH) stage 20, which is equivalent to the E11.5 mouse embryonic stage.38 Results showed that hPAS1 enhanced the expression of the reporter gene in the ventral and dorsal spinal cord of chicken embryos, and the expression of the reporter gene linked to cPAS1 was confined to the ventral spinal cord (Supplementary information, Fig. S3), as that observed in the mouse embryos (Supplementary information, Fig. S2). Therefore, mice can be used to study the function of various PAS1s.

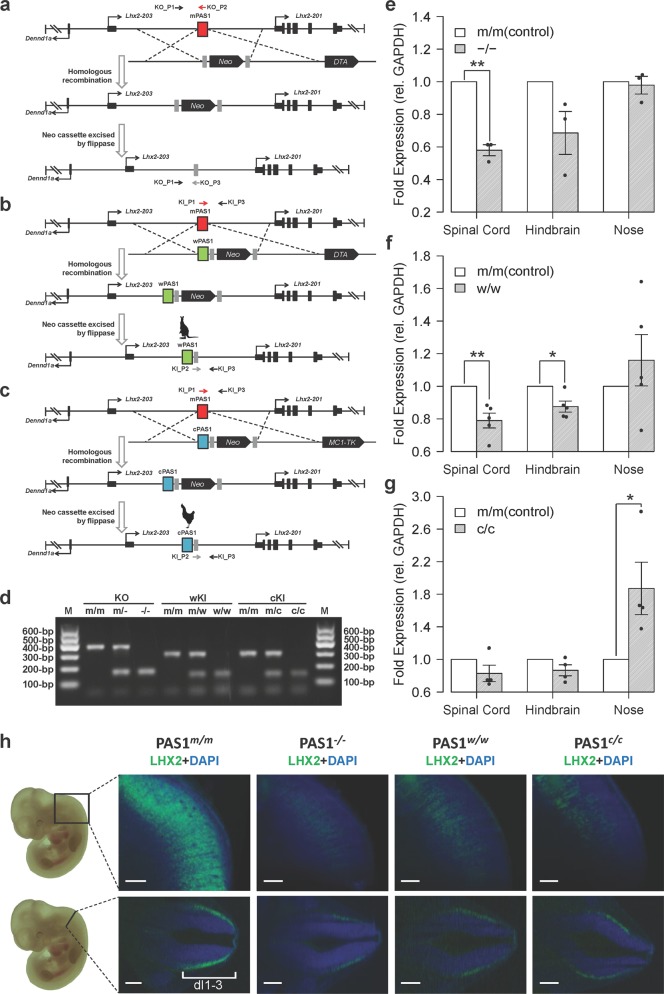

Generation of PAS1−, PAS1w, and PAS1c mice

To confirm and further study the function of PAS1s, three mouse strains (PAS1c, cPAS1 knock-in; PAS1w, wPAS1 knock-in; and PAS1−, PAS1 knock-out) were generated by homologous recombination in C57BL/6 mouse embryonic stem cells (Fig. 3a–c). Since these strains were generated and inbred with the C57BL/6 background, the only genetic difference among them was the PAS1 locus (Fig. 1c). The chicken (PAS1c), wallaby (PAS1w), and knock-out (PAS1−) alleles were found to segregate in Mendelian ratios (χ2 = 1.816, 1.266, 2.341; n = 103, 331, 276; P = 0.597, 0.469, 0.690, respectively). All genotypes were present in littermates (Fig. 3d). Compared with the wild-type controls, no obvious defects in appearance, size, development, and fertility were observed in adult homozygous mutants (PAS1c/c, PAS1w/w, and PAS1−/− mice). There was also no abnormality in the histology of newborn (postnatal day zero, P0) PAS1−/− brains. Homozygous mutant mice (PAS1w/w, PAS1c/c, and PAS1−/−) had normal huddled sleeping behavior and nesting patterns. We did not observe the abnormal social interaction (i.e., random sleeping patterns) that was found in Dishevelled1-deficient mice.39 Adult homozygous mutants had a normal lifespan, and the oldest ones were healthy for more than 17 months at the time of study.

Fig. 3. Effect of PAS1s from various amniotes on the expression of Lhx2 in embryonic nervous system.

a–c Generation of PAS1−, PAS1w and PAS1c mice. Either pGK-Neo/DTA or pGK-Neo/Mc1-TK selection cassette was used. d PCR genotyping of wild-type (PAS1m) and mutant (PAS1−, PAS1w and PAS1c) mice. e–g Expression of Lhx2, determined by RT-qPCR, in spinal cord, hindbrain, and nose of E11.5 PAS1−/−, PAS1w/w, and PAS1c/c. Fold expression of Lhx2 is relative to the control (wild-type littermates PAS1m/m). Error bars represent the SEM of at least three biological replicates with three technical replicates for each experiment. One-tailed Student’s t-test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. h Spinal cord of E11.5 wild-type, PAS1−/−, PAS1w/w, and PAS1c/c embryos after CUBIC clearing and LHX2 immunostaining (green). Wild-type littermates (PAS1m/m) were used as the control, and only one littermate was shown. LHX2 protein levels are decreased significantly, and the expression region is distant from the dorsal spinal cord in PAS1−/−, PAS1w/w, and PAS1c/c mice, compared with the control. The region with Lhx2 expression in the wild-type embryo is marked (dI1-3, three neuronal cell types).80 One representative of each genotype is shown. All embryos (n ≥ 3 per genotype) are shown in Supplementary information, Fig. S8. Scale bar, 200 μm.

PAS1 as an enhancer of Lhx2 in the embryonic nervous system

To determine the region where PAS1 may act on, the topologically associating domain (TAD) surrounding PAS1 was determined by TADTree.40 In addition to Lhx2, another protein-coding gene named DENN domain containing 1A (Dennd1a) and a non-coding RNA gene (Gm27197) are also in the TAD (Supplementary information, Fig. S4). The high-resolution chromosome conformation capture (Hi-C) data41 showed interactions of PAS1 with the transcription start site of Lhx2, but not with that of Dennd1a or Gm27197, in mouse neurons (Supplementary information, Fig. S5c–f). There was a positive correlation between the CAGE reads of PAS1 and those of Lhx2 (Supplementary information, Fig. S5a, b). With reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR), the mRNA levels of Dennd1a (Supplementary information, Fig. S6) and Gm27197 (Supplementary information, Fig. S7) in the brain tissues from different developmental stages of the three mouse strains were found not to be affected by PAS1. The closest downstream protein coding gene to Lhx2 was the NIMA related kinase 6 gene (Nek6) that controls the initiation of mitosis. Lhx2 and Nek6 had been shown to have a completely different expression pattern;42 this is consistent with the observation that these two genes belong to different TADs (Supplementary information, Fig. S4). These results support the hypothesis that PAS1 is an enhancer of Lhx2 in the embryonic nervous system.

The expression levels of Lhx2 in the primitive nose, spinal cord, and hindbrain of mouse strains, PAS1−/−, PAS1w/w, and PAS1c/c, were then determined by RT-qPCR. Compared with the wild-type PAS1m/m mouse embryos, the expression levels of Lhx2 were generally decreased in the primitive hindbrain and spinal cord of E11.5 mouse embryos of all 3 homozygous mutant strains (Fig. 3e–g), but were increased in the primitive nose of the two knock-in homozygous mutants, PAS1w/w and PAS1c/c, while the expression of Lhx2 in PAS1−/− and PAS1m/m mice was at similar levels. No differential expression of Lhx2 was found in various regions of the brain of P0 mice (Supplementary information, Fig. S8); this result is consistent with the conclusion that PAS1 (Fig. 2a) and Lhx243 mainly function during the embryonic stage. Therefore, compared with PAS1m/m mice, all homozygous mutant strains showed differential expression of Lhx2 in the primitive nose, spinal cord, and hindbrain of mouse embryos.

The differential expression of Lhx2 in the whole brain of the transgenic mice was further examined by CUBIC (clear, unobstructed brain/body imaging cocktails and computational analysis) combined with immunostaining.44 The LHX2 protein levels in the hindbrain and spinal cord were found to be decreased in the E11.5 embryos of the three homozygous mutants (Fig. 3h; Supplementary information, Fig. S9). The levels of LHX2 protein in the E11.5 spinal cord were significantly lowered in PAS1−/− (~18% reduction, measured as the width of the LHX2 expression areas; two-tailed permutation test, P = 0.00003), PAS1w/w (~20% reduction; two-tailed permutation test, P = 0.00551) and PAS1c/c mice (~22% reduction; two-tailed permutation test, P = 0.00506), compared with those of the wild-type mice (Supplementary information, Fig. S10; Tables S2–4). These results are generally consistent with the spinal expression changes of Lhx2 detected by RT-qPCRs (40%, 21% and 17% reduction in PAS1−/−, PAS1w/w, and PAS1c/c, respectively).

Modulation of social hierarchy by PAS1 in caged adult male mice

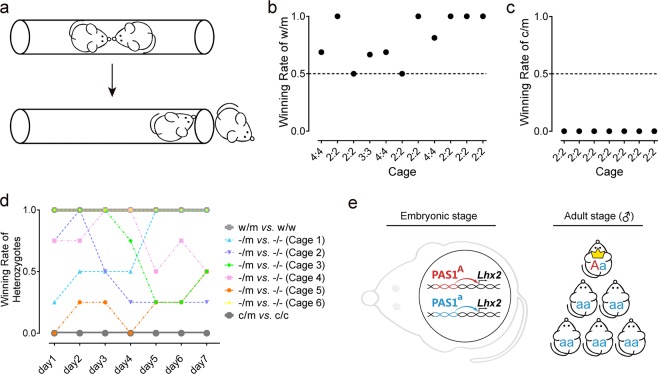

The social dominance tube test39,45–47 was then performed to evaluate the dominance tendency of mice with different PAS1 alleles (Fig. 4a). To determine the effect of the PAS1w allele on social hierarchy, the social dominance of PAS1w/m and PAS1w/w male mice was examined. PAS1w/m and PAS1w/w male mice (with similar age and weight) were housed together for at least two weeks before the test. Results (Fig. 4b; Supplementary information, Table S5) showed that the social dominance of PAS1w/m mice was significantly higher than that of PAS1w/w mice (One-tailed binomial test performed at cage level, P = 0.033; One-tailed permutation test performed at the level of trials, P = 7.0 × 10−7). The overall winning rate of PAS1w/m and PAS1w/w is 75.6 and 24.4%, respectively. Similarly, the effect of the PAS1c allele on social hierarchy was evaluated by the PAS1c/m against PAS1c/c test. In this test, PAS1c/m mice lost all the trials (Fig. 4c; Supplementary information, Table S6, n = 28) and their social dominance rank was significantly lower than that of PAS1c/c mice (One-tailed binomial test performed at cage level, P = 0.008; One-tailed permutation test performed at the level of trials, P = 3.1 × 10−6). The overall winning rate of PAS1c/m and PAS1c/c is 0.0 and 100.0%, respectively. In both cases, social dominance was heritable and genetically determined by the PAS1 alleles of mice. Interestingly, the dominance and subordinate ranks could be turned over by mutated PAS1.

Fig. 4. Modulation of social hierarchy by PAS1s from various amniotes in caged adult male mice.

a Schematic of the social dominance tube test. b Winning rate of PAS1w/m male mice against PAS1w/w male mice. The x-axis indicates the number of adult male mice in each cage with the two different genotypes (PAS1w/m: PAS1w/w). c Winning rate of PAS1c/m male mice against PAS1c/c male mice. The x-axis indicates the number of adult male mice in each cage with the two different genotypes (PAS1c/m: PAS1c/c). d Results of the tube test over 7 consecutive days. e Proposed mechanism for positive selection on PAS1 and the evolution of social hierarchy. A beneficial allele (denoted “A”) occurs at the PAS1 locus, leading to a beneficial change in the expression of Lhx2. Allele “a” represents the ancestral allele. The genotype of the carrier with the beneficial allele is designated as “Aa”. The frequency of the beneficial allele is low in the beginning phase of positive selection.81

In the PAS1−/m against PAS1−/− test (Supplementary information, Table S7), the winning rate of PAS1−/m mice varied between 0.0 and 1.0 (Fig. 4d), indicating that the social dominance of these mice does not correlate with their genotypes. Thus PAS1 knock-out mice showed no inheritance of social dominance. Results of all six cages of mice showed that the social dominance ranks of PAS1−/m and PAS1−/− mice were different in different days (Fig. 4d; Supplementary information, Fig. S11c–h). These were significantly different from the stable social ranks of wild-type mice46,47 and mice with the wallaby or chicken PAS1 alleles (Supplementary information, Fig. S11a, b) (One-tailed binomial test, P = 0.0017). Moreover, ranks of four PAS1−/− mice remained unstable (Supplementary information, Fig. S12; Table S8) even after being housed together for more than 12 weeks, which again demonstrate that PAS1 knock-out mice lack social stratification. Taken together, results of the social dominance tube test suggest that PAS1-Lhx2 is essential to determine social dominance and to establish well-organized social systems in amniotes.

The difference in motor coordination, strength and balance of mice (Supplementary information, Fig. S13) cannot explain the phenotypic differences observed above. Moreover, there was also no significant difference in body weight of mice at two months when the tube test was carried out (Supplementary information, Fig. S14), suggesting that the difference in growth curve of mice cannot explain the phenotypic differences observed above.

Discussion

Here, using an evolutionary genomics approach and building mouse models, we provide the genetic basis of social hierarchy systems in amniotes. Although Lhx2, a highly conserved and key regulator of brain development,36,48,49 was first identified as a critical regulator of wing development in Drosophila more than one hundred years ago (named apterous),50 its function in social hierarchy has never been determined. This is due to severe defects in Lhx2 knock-out mice and their embryonic lethality.51 Lhx2 regulates the Wnt pathway,49,52 and Dishevelled1 is the central mediator of the Wnt pathway. Dishevelled1 knock-out mice exhibit abnormal social interaction.39 Therefore, we speculated that Lhx2 modulates social hierarchy by regulating the Wnt pathway. Lhx2 is a selector gene in the cerebral cortex53 and controls neuronal subtype specification,54–56 axon projection, and dendritic arborization of neurons.57,58 Taken together, we suggest that PAS1, the enhancer of Lhx2, acts as an ignition controller. Mutations of PAS1 may alter the spatial-temporal expression pattern of Lhx2, resulting in different cell fate decisions in the modulation of social hierarchy.

PAS1 knock-out mice lack social stratification (Fig. 4d; Supplementary information, Figs. S11c–h and S12). Thus the regulatory activity of PAS1 is essential to establish well-organized social systems in amniotes. Only a few studies document that the knock-out of specific genes affects the ability to form stable social hierarchy.59,60 PAS1 is, therefore, the first example that an enhancer-deficient mice lack social stratification. We also showed that PAS1 might modulate social hierarchy by controlling the expression of Lhx2 in the roof of dorsal pallium (future cerebral cortex), primitive nose, hindbrain, spinal cord, and pretectum in the mouse embryos (Figs. 2 and 3). This result agrees with the brain regions identified in neuroscience that regulate social hierarchy.46,61–63 Thus, PAS1 provides a great opportunity to identify key transcription factor binding sites involved in social hierarchy, and drive the expression of reporter gene to paint neural circuits involved in social hierarchy.

PAS1 is not (highly) conserved within the placental and non-placental clades (Fig. 1c, d) because social systems are highly variable even within taxa, for example rodents,64 primates,65 mammals,8,66 and birds.67 A previous study predicted eight conserved noncoding elements near Lhx2 as enhancers,37 and PAS1 was none of them. Therefore it is a good strategy to compare the normalized evolutionary rate among branches within each sliding window. The functional evidence of wallaby- and chicken-PAS1s indicate that PAS1-Lhx2 modulates social hierarchies in non-placental amniotes. These findings also suggest the importance of non-conserved regulatory elements during evolution. There are 130 substitutions and 12 indels accumulated between wallaby- and chicken-PAS1s since the two species diverged 324.5 million years ago. These genetic changes provide us a great opportunity to pinpoint the causal substitutions for the turn-over of social dominance. Moreover, we focused only on the emergence of social hierarchy systems in the ancestral lineage of placental mammals, although many independent evolutionary transitions of social system had occurred in different phylogenetic stages.8 Further evolutionary analysis would reveal more evidence on how social systems evolved.

In summary, the association of PAS1 with social hierarchy provides novel insights into the genetic basis of social hierarchy systems (Fig. 4e). This study provides not only the first evidence how social behavior could be maneuverable during the evolution of amniotes, but also an evolutionary approach to study novel function of genes. Social hierarchies in amniotes are modulated by the enhancer PAS1 of Lhx2, and the accelerated evolution of PAS1 shapes social hierarchies in numerous placental mammals. Social hierarchy involves social recognition, social learning,68 dominance perception,61 and synaptic plasticity.1 The integration of social neuroscience, comparative genomics, molecular mechanisms, and development into the field of evolution may provide a unified and comprehensive view of social hierarchy.

Materials and methods

Mice and chicken embryos

All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the protocols approved by the Committee and Laboratory Animal Department, Shanghai Institute of Nutrition and Health. Governmental and institutional ethical guidelines were followed. In vivo transgenic mouse enhancer assays were performed in FVB mice. PAS1 knock-out and knock-ins were generated in C57BL/6 mice. Mice with the following developmental stages and ages were used: embryonic day 11.5 (E11.5); newborn (postnatal day zero, P0); and 7–19 weeks old. E11.5 and P0 mice of both sexes were used. 7–19 weeks old males were used for the social dominance tube test and assessment of motor coordination, strength, and balance. Fertilized chicken eggs were obtained from Shanghai Academy of Agricultural Sciences and were incubated at 38 °C with 25%–40% humidity.

Cell line

Human cell line HEK-293 (GNHu43) was purchased from Cell Bank, Chinese Academy of Sciences (www.cellbank.org.cn). Neuro2A cells (TMC29, Cell Bank, Chinese Academy of Sciences) were cultured in MEM (41500034, Gibco) with 10% fetal bovine serum (12007C, SIGMA) and maintained in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C.

Animal tissues

Cow (Bos taurus) and chicken (Gallus gallus) muscle samples were purchased from a local supermarket. Hairs from red-necked wallaby (Macropus rufogriseus) were provided by the Shanghai Zoological Park.

Multi-genome alignments

Multi-genome alignments of the following 16 representative species of amniotes were created by MULTIZ69 (http://www.bx.psu.edu/miller_lab/): Homo sapiens (human, GRCh37/hg19), Pan troglodytes (chimpanzee, CGSC 2.1.3/panTro3), Pongo abelii (orangutan, WUGSC 2.0.2/ponAbe2), Macaca mulatta (rhesus, MGSC Merged 1.0/rheMac2), Mus musculus (mouse, NCBI37/mm9), Rattus norvegicus (rat, Baylor 3.4/rn4), Cavia porcellus (guinea pig, Broad/cavPor3), Oryctolagus cuniculus (rabbit, Broad/oryCun2), Bos taurus (cow, Bos_taurus_UMD_3.1/bosTau6), Equus caballus (horse, Broad/equCab2), Canis lupus familiaris (dog, Broad/canFam2), Loxodonta africana (elephant, Broad/loxAfr3), Monodelphis domestica (opossum, Broad/monDom5), Taeniopygia guttata (zebra finch, WUGSC 3.2.4/taeGut1), Gallus gallus (chicken, WUGSC 2.1/galGal3), and Anolis carolinensis (lizard, Broad AnoCar2.0/anoCar2). Genome sequences and paired genome alignments with human genome as the reference were downloaded from the UCSC genome browser website (http://hgdownload.soe.ucsc.edu/downloads.html). UCSC Kent utilities (http://hgdownload.cse.ucsc.edu/admin/jksrc.zip) were used for fetching information of chromosome size and adding sequencing quality score to each base.

Phylogenetic tree

The Common Tree function of the NCBI Taxonomy database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Taxonomy/CommonTree/wwwcmt.cgi) was used to construct the phylogenetic tree of the 16 amniotes. The divergence time (in units of one million years) of paired species among the 16 amniotes was obtained from the TimeTree website (www.timetree.org)31 and used to determine the length of each branch in the phylogenetic tree. In Newick format, the tree used in this study (Fig. 1a) is ((((((((human:6.4,chimpanzee:6.4):9.3,orangutan:15.7):13.9,rhesus:29.6):61.4,(((mouse:25.2,rat:25.2):46.9,guineaPig:72.1):14.3,rabbit:86.4):4.6):6.4,(cow:84.6,(horse:82.5,dog:82.5):2.1):12.8):7.3,elephant:104.7):71.4,opossum:176.1):148.4,((chicken:106.4,zebraFinch:106.4):168.5,lizard:274.9):49.6):0, where the branch length is in unit of one million years.

As the divergence times obtained from the TimeTree31 may be estimated from mitochondrial sequences and biased, another tree with the divergence times estimated from nuclear genes31 was constructed to validate the results as follows: ((((((((human:7.8,chimpanzee:7.8):9.2,orangutan:17.0):11.8,rhesus:28.8):60.2,(((mouse:19.0,rat:19.0):63.8,guineaPig:82.8):3.3,rabbit:86.1):2.9):5.0,(cow:83.8,(horse:82.5,dog:82.5):1.3):10.2):10.0,elephant:104.0):82.8,opossum:186.8):137.7,((chicken:95.0,zebraFinch:95.0):176.7,lizard:271.7):52.8):0.

Moreover, an arbitrary disturbed tree was also constructed to further validate the robustness of the KFP method on the uncertainty of estimated divergence times (i.e., branch lengths). Based on the known phylogenetic tree (Fig. 1a), the length of each branch was randomly adjusted within its ±15% range. The disturbed tree is: ((((((((human:6.04,chimpanzee:6.04):9.1,orangutan:15.14):12.89,rhesus:28.03):63.7,(((mouse:25.62,rat:25.62):45.16,guineaPig:70.78):15.64,rabbit:86.42):5.31):6.35,(cow:84.19,(horse:82.03,dog:82.03):2.16):13.89):7.9,elephant:105.98):74.33,opossum:180.31):150.14,((chicken:99.06,zebraFinch:99.06):179.28,lizard:278.34):52.11):0

For the further validation, one (rabbit) or two (orangutan and dog) species were removed from the analyses. The related trees were ((((((((human:6.4,chimpanzee:6.4):9.3,orangutan:15.7):13.9,rhesus:29.6):61.4,((mouse:25.2,rat:25.2):46.9,guineaPig:72.1):18.9):6.4,(cow:84.6,(horse:82.5,dog:82.5):2.1):12.8):7.3,elephant:104.7):71.4,opossum:176.1):148.4,((chicken:106.4,zebraFinch:106.4):168.5,lizard:274.9):49.6):0 and (((((((human:6.4,chimpanzee:6.4):23.2,rhesus:29.6):61.4,(((mouse:25.2,rat:25.2):46.9,guineaPig:72.1):14.3,rabbit:86.4):4.6):6.4,(cow:84.6,horse:84.6):12.8):7.3,elephant:104.7):71.4,opossum:176.1):148.4,((chicken:106.4,zebraFinch:106.4):168.5,lizard:274.9):49.6):0, respectively.

Detection of accelerated sequences by the Kung-Fu Panda (KFP) software

The multi-genome alignments were scanned with a 100 bp sliding window and a sliding step of 20 bp. To calculate the evolutionary rate (i.e., substitution rate) of each window in each branch, the ancestral nodes of the phylogenetic tree were reconstructed by the maximum parsimony method with consideration of the uncertainty of reconstructing the ancestral sequence of each internal node.26

The evolutionary rate of the w-th window in the i-th branch is , where Di,w is the divergence per site of the w-th window in the i-th branch (estimated from the observed number of substitutions in the i-th branch divided by the length of the fragment considered), and the estimated branch length (in units of one million years) of the i-th branch in the tree (Fig. 1a). The tree and the estimated branch lengths were described in the section of phylogenetic tree. Di,g is the genome-wide divergence (per site) in the i-th branch, and li the true branch length (in units of one million years). As expected, li generally remains unknown. There are 16 considered species and 30 (=2n − 2) branches in the phylogenetic tree, where n is the number of considered species.70 The tree length .

It is well-known that the genome-wide evolutionary rate varies among lineages.27,28 Thus branch-specific normalization was necessary to make the normalized genome-wide evolutionary rate in the i-th branch equal with that in other branches. Then a branch-specific normalization factor (αi for the i-th branch, defined by Eq. (3) below) was applied to normalize the evolutionary rate of the w-th window in the i-th branch to make it comparable among lineages when testing the accelerated evolution.

The genome-wide evolutionary rate in the i-th branch is μi,g = Di,g/li, and the genome-wide evolutionary rate in the tree is . Denote λi = μi,g/μg as a correction factor of genome-wide evolutionary rate in the i-th branch. Then we have μg = μi,g/λi, indicating that the corrected genome-wide evolutionary rate for each branch is equal with each other. Therefore, this correction eliminates the effect of varying genome-wide evolutionary rate among lineages. Then μi,w/λi (i.e., the corrected evolutionary rate) for the w-th window is comparable among lineages. In another word, if the lineage is fast evolving (i.e., μi,g > μg), then λi > 1, and the local evolutionary rate in the i-th branch (μi,w) needs to be reduced accordingly to compare with the local corrected evolutionary rate in other branches.

Moreover, the uncertainty of estimated branch length (in units of one million years) needs to be addressed since the true branch length li is unknown. Denote where ki is a correction factor for correcting the estimated length to the true length of the i-th branch. As pointed in the main text, the varying genome-wide evolutionary rate and the uncertainty of estimated branch length act together and may be difficult to distinguish from each other. Therefore, to consider these two factors together, let us define αi = 1/(λiki). Then the genome-wide evolutionary rate in the tree can be written as

| 1 |

Next, ltree can be reasonably approximated by since phylogeny has been studied well for more than 50 years.31 Then we have,

| 2 |

Moreover, the robustness analyses (see the Results section) also demonstrated that the new method was robust to this approximation.

From (Eq. (1)) and (Eq. (2)), we have

Then

| 3 |

Finally, the normalized evolutionary rate of the w-th window in the i-th branch is

If the branch lengths were precisely estimated (i.e., ki ≈ 1),31 αi would be mainly determined by the genome-wide evolutionary rate varied among lineages. For the fast evolving lineages, it is expected that αi < 1, thus μi,w,norm is smaller than the observed evolutionary rate of the w-th window. For the slow evolving lineages, it is expected that αi > 1, thus μi,w,norm is larger than the observed one. After normalization, μi,w,norm is compared among lineages.

The branch-specific normalization factor αi is the product of λi and ki. ki is the correction factor to correct the estimated branch length in the tree (Fig. 1a) to the true branch length. If the uncertainty of the estimated branch length in the tree is substantial (i.e., ki ≠ 1), the branch-specific factor αi will change accordingly, to overcome this effect. This is why the new method is robust to the uncertainty of the estimated branch length in the tree (see the Results section).

The comparison of the evolutionary rate among different lineages is very common and the strategy has been used for many years.70 To detect accelerated evolution of the w-th window, the observed normalized evolutionary rate of the red branch (i.e., the ancestral lineage of placental mammals) was compared with those of the non-red branches (Fig. 1a). Thus the evolutionary rate of the non-red branches was taken as the expected neutral (i.e., not-accelerated) evolutionary rate of the red branch. Therefore, the normalized expected neutral evolutionary rate (μred,norm,exp) of the w-th window in the ancestral lineage (the red branch) of placental mammals was compared with the normalized observed evolutionary rate (μred,w,nom,obs).

The Poisson probability describes the substitution/mutation process well, and has been popularly and successfully used to study the varying evolutionary rate among lineages.70,71 Therefore, the significance level of accelerated evolution was then determined by the Poisson probability:70,71 , where and , and 71.4 was the estimated branch length of the red branch (in unit of one million years) (Fig. 1a), Lw the sequence length of the w-th window, ξobs and ξexp the observed and the expected number of substitutions in the red branch. The window was discarded if μred,w,norm,exp = 0.

In this study, the maximum value of the normalized evolutionary rate of the w-th window for the non-red branches was used as μred,w,norm,exp. It represents the upper bound of neutral evolutionary rate of the w-th window along the phylogenetic tree (excluding the red branch). In another word, the neutral evolutionary rate of the w-th window for the red branch is very unlikely to exceed this upper bound. Thus it makes the accelerated evolution test conservative. The following procedure was applied to obtain μred,w,norm,exp:

Partition the tree into 17 branch sets (excluding the red branch). All branches in each set were directly connected, and the length of each set of branches was similar to that of the red branch (Supplementary information, Fig. S1a).

The normalized evolutionary rate of the w-th window in each branch set was the average (weighted by branch lengths) of normalized evolutionary rates of the branches.

The maximum value of the 17 normalized evolutionary rates of the w-th window was used as the expected neutral evolutionary rate (μred,w,norm,exp) in the ancestral lineage of placental mammals.

Therefore, the logic behind the new method (KFP) was actually very simple and straightforward. For each window, we made the evolutionary rate comparable among branches, and compared the maximum evolutionary rate in the non-red branches with the observed evolutionary rate of the red branch. The accelerated evolution was then determined by the Poisson probability. As an alternative option, when estimating μred,w,norm,exp, the average value of the evolutionary rate of the branch sets can be used. The alternative option provides more power to detect the accelerated evolution.

All indels and the nucleotides with a quality score less than 9 were removed from the analysis. The ends of the red branch were connected to three key nodes or clusters, i.e., the node of opossum, and the node of elephant, and the cluster of non-elephant placentals (Fig. 1a). At least a 30 bp valid sequence length was present in each key node or cluster. As the orthologue sequence might be missing in some species, the number of species with missing orthologue sequence was set for less than four, and the maximum indels was set for 30% in the species with orthologue sequence (counted as whole in the alignment of the w-th window).

After all windows (3,269,214) were analyzed, the Bonferroni correction29 was performed to adjust the threshold for multiple tests (the desired overall Type I error rate, i.e., the family-wise error rate, is 0.01). The threshold of P values was 3.06 × 10−9.

With little modifications, the algorithm described above was generalized and implemented in the KFP software. The software is specifically designed to detect nucleotide sequences with accelerated evolution on a user-defined internal branch, based on a user-defined configuration. This software is written in Java and can run very fast. It is suitable for various computer platforms, including personal computers and high-performance computing environments such as computer clusters and super computers.

Neighbor-joining tree

To visualize the accelerated evolution of PAS1, the unrooted Neighbor-Joining tree24 of the conjunction of the accelerated cluster 1 and 2 was constructed by the eGPS software.25 The evolutionary distances were computed using the Tajima-Nei method72 and are in the units of the number of base substitutions per site. All positions containing gaps and missing data were eliminated.

To confirm the tree topology (Fig. 1a), the eGPS software25 was used to construct another phylogenetic tree from the multi-genome alignments by the Neighbor-Joining method.24 The genetic distance was calculated by measuring the number of nucleotide substitutions, and the Kimura 2-parameter model was used to correct for multiple hits. The option of considering gaps or missing data as complete deletion was adopted.

Plasmids for cell transfection

To build miniPro-pGL4.11, a 32 bp DNA containing the minimal promoter with a HindIII site at each end was synthesized and then inserted into pGL4.11 (E6661, Promega). To construct *PAS1-miniPro-pGL4.11, where *PAS1 stands for the PAS1 from human, mouse, cow, wallaby, or chicken, each PAS1 was amplified by PCR using appropriate primers (Supplementary information, Table S9) with an Xho I site built in and cloned into miniPro-pGL4.11. Genomic DNAs used as templates were isolated from human HEK-293 cells, hairs of red-necked wallaby (Macropus rufogriseus), and tissues from mouse, cow, and chicken. The cloned PAS1 from all 5 species (*PAS1) and the final plasmids were verified by sequencing, and the PAS1 sequences were confirmed as those of respective reference genomes (Human hg19 chr9:126,770,367–126,771,183, Mouse mm9 chr2:38,203,254–38,204,076, Cow bosTau8 chr11:95,121,207–95,122,014, Chicken galGal4 chr17:9,221,037–9,221,907). There are two nucleotide differences between wPAS1 from red-necked wallaby and the reference tammar wallaby (Macropus eugenii) genome MacEug2 (GL116911:107,159–108,048; GL116911:107,628, A->C; GL116911:107,557, C->T). These two sites are located at the junction between the two accelerated clusters.

Cell culture and transfections

For transfection, FuGENE® HD (E2311, Promega) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A Renilla luciferase plasmid (pGL4.74, E6921, Promega) was co-transfected to control for transfection efficiency. Neuro2A cells were seeded in wells of a 24-well plate at a density of 2 × 104 cells per well one day prior to transfection. *PAS1-miniPro-pGL4.11 and pGL4.74 were then co-transfected at a total concentration of 420 ng per well (50:1 molar ratio of *PAS1-miniPro-pGL4.11 to pGL4.74). A pair of CAG-mCherry and pGL4.74 with a mass ratio of 50:1 was used as the positive control, and a pair of PUC19 and pGL4.74 with a mass ratio of 50:1 was used as the negative control. For each experiment, at least three replicates were performed. Luciferase assays were performed 48 h after transfection using the Dual-Glo™ Luciferase Assay System (E2920, Promega) according to manufacturer’s instructions, and measurements of luciferase reactions were made on a Synergy H1 plate reader (Bio-Tek).

Transgenic mouse enhancer assays

Transgenic FVB mice were created by Cyagen Biosciences using standard procedures.73 PAS1s based on the human (hg19), mouse (mm9) and chicken (galGal4) reference genome sequences, and the ortholog sequence of red-necked wallaby (see the section above) were synthesized and cloned into the Hsp68-lacZ reporter vector. The resulting plasmids were verified by Sanger sequencing. *PAS1-Hsp68-lacZ (*PAS1 from human, mouse, chicken, or wallaby) reporter plasmids were linearized, purified, and microinjected into FVB mouse zygotes. The numbers of injected zygotes were 150, 300, 450, and 300, respectively. The injected zygotes were implanted, and embryos were harvested at E11.5. As the linearized plasmid DNA integrated into the mouse genomic DNA by a random and multiple copy way, the result embryos can show a high variability between biological replicates.35,74,75 LacZ expression in a specific region of the embryo in at least two independent embryos was considered positive.

Chicken embryo electroporation

Primers (Supplementary information, Table S9) with a SalI site built in were used to amplify PAS1s from human HEK-293 cells and chicken samples. The PCR products were then cloned into pTK-EGFP and pTK-mCherry. The resulting plasmids were verified by sequencing.

Fertilized eggs were cleaned with 70% ethanol and then incubated at 38 °C with 25%–40% humidity for 41 h (HH stage 11). To inject DNA into the neural tube of a chicken embryo, a window 2–2.5 cm in diameter was made on the top of each egg. A 4 inch 1.0 mm thin wall capillary glass (TW100F-4, WPI) was used to make injection needles with a Micropipette Puller (MODEL P-2000, SUTTER INSTRUMENT CO.). A DNA solution of 1–2 ml containing hPAS1-TK-EGFP or cPAS1-TK-mCherry at 2 μg/μL and the marker plasmid DNA (pCAG-mCherry or pCAG-EGFP at 200 ng/μL) or hPAS1-TK-EGFP mixed with cPAS1-TK-mCherry at 1:1 molar ratio with 0.1% Fast Green dye (F7252, SIGMA) was injected into the central canal of the neural tube. pCAG-mCherry or pCAG-EGFP was used as the control. The injection was done using a Pump 11 Elite nanomite (Harvard Apparatus). After the injection, two 3 mm long L-shaped platinum electrodes (LF613P3, BEX) were placed parallel to the anterior-posterior axis of the embryo, with the neural tube sitting between the two electrodes. The distance between the two electrodes was 3 mm. Electroporation was performed using a CUY21 EDIT II electroporator (BEX) with three pulses of 20 V for 25 ms each with a 500 ms interval. Embryos were further incubated for 40 h at 38 °C with 25%–40% humidity. Live embryos were harvested at HH stage 20.

Generation of PAS1−, PAS1w and PAS1c mice

Mice with the PAS1 knock-out allele (PAS1−) and those with the PAS1w allele were created by Cyagen Biosciences Inc. Mice with the PAS1c allele were generated by Shanghai Biomodel Organism Science & Technology Development Co., Ltd. C57BL/6 embryonic stem (ES) cells were used to generate the transgenic mice. To engineer the targeting vector for generation of PAS1 knock-out (PAS1−) mice, a 5' homology arm (4.7 kb) and a 3' homology arm (2.8 kb) flanking the core region of mouse PAS1 (mm9 chr2:38,203,382–38,204,067) were amplified by high-fidelity PCR from a C57BL/6 BAC clone (RP23-119M6). The Neo (neomycin) cassette was then inserted between the two arms, and the DTA (diptheria toxin A) gene was inserted downstream from the 3' homology arm. The resulting vector was named mm9-KOS141218 and confirmed by sequencing. The targeting vector was electroporated into C57BL/6 ES cells. The Neo cassette flanked by Frt sites was used to select ES cells that had taken up the targeting vector, and the DTA gene was used for negative selection to eliminate ES cells in which the homologous recombination event was not through double crossing over. Five correctly recombined clones were identified by long-distance PCR and confirmed by Southern blotting. C57BL/6 ES clone 1G7 was used for blastocyst injection and subsequent generation of PAS1− knock-out mice by flippase-mediated recombination through mating with Flp mice.

To generate mice with the PAS1w allele, the core region of mouse PAS1 was replaced by the ortholog PAS1 allele of red-necked wallaby (755 bp). C57BL/6 ES clone 2C5 was used for blastocyst injection and subsequent generation of PAS1w mice. For generation of mice with the PAS1c allele, the core region of mouse PAS1 was replaced by the chicken ortholog PAS1 allele (galGal4 chr17:9,221,163–9,221,898, 736 bp). For this generation, the Mc1-TK gene was used for negative selection. C57BL/6 ES G10 was used for blastocyst injection and subsequent generation of PAS1c mice.

The sequences of PAS1 regions of the three mouse strains were confirmed by sequencing (Supplementary information, Fig. S15). Mice carrying the PAS1− allele were genotyped using the KO_P1/KO_P2 primer set for the wild-type allele (366 bp) and the KO_P1/KO_P3 primer set for the PAS1− allele (176 bp). Mice carrying the PAS1w and PAS1c alleles were genotyped using the KI_P1/KI_P3 primer set for the wild-type allele (293 bp) and the KI_P2/KI_P3 primer set for the PAS1w and PAS1c replacement alleles (152 bp). Primers used are shown in Supplementary information, Table S9.

RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis

Nose, olfactory bulb, and spinal cord were dissected from P0 PAS1−, PAS1w, and PAS1c mice. Nose, hindbrain, and spinal cord were dissected from E11.5 embryos of PAS1−, PAS1w, and PAS1c mice. As the boundary between the hindbrain and spinal cord in E11.5 mouse embryo could not be visualized, the hindbrain tissues obtained might have contained a little spinal cord. RNAs were isolated from the isolated tissues using the TaKaRa MiniBEST Universal RNA Extraction Kit (9767, TaKaRa). RNA concentration was determined by Nanodrop ND-1000. For cDNA synthesis in the RT-qPCR assay, 500 ng of RNA was reverse transcribed using the TransScript®II All-in-One First-Strand cDNA Synthesis SuperMix (AH341, TransGen).

RT-qPCR analysis

For each RT-qPCR, 2 ng of RNA was used, and the reaction was performed using the TransStart® Top Green qPCR SuperMix (AQ131, TransGen). Samples were run on a LightCycler 480 (Roche). The expression levels of Lhx2, Dennd1a and Gm27197 were normalized to that of GAPDH. For Lhx2, two pairs of primers were used. One of which (Lhx2_F and Lhx2_R) amplified the third and fourth exons of Lhx2-201 (ENSMUST00000000253) and Lhx2-203 (ENSMUST00000143783) transcripts. The other pair (Lhx2_203F and Lhx2_203R) amplified the longest transcript Lhx2-203 (ENSMUST00000143783). For all RT-qPCR analyses, at least three replicates were performed. Primers used are shown in Supplementary information, Table S9.

Whole embryo clearing and immunohistochemistry

A modified CUBIC clearing method was used.44 Two CUBIC reagents were prepared as previously reported.44 The fixed E11.5 embryos were immersed in CUBIC-1 reagent containing DAPI (1:1000; D8417, Sigma) for 1 day and in another solution containing the primary antibody (anti-LHX2 antibody, 1:400; ABE1402, Millipore) and DAPI for 3 days. Embryos were then incubated in a solution containing the secondary antibody (1:400; A11034, Life technologies) and DAPI for 3 days and in CUBIC-2 reagent for 1 day. All processes were done at 37 °C.

Social dominance tube test

Male mice of two different genotypes with similar age and weight were housed together in the same cage for at least two weeks before the test. The age difference of these mice was < 3 days in 75% (18/24) of the cages (Supplementary information, Tables S5-7). At the second week, female C57BL/6 mice with similar age were added into cage to simulate the natural situation of wild populations. The following combinations were used: (1) Four male mice (PAS1w/m:PAS1w/w = 2:2) with one female mouse (cage size: 50 × 35 cm); (2) Six male mice (PAS1w/m:PAS1w/w = 3:3) with two female mice (cage size: 90 × 90 cm); (3) Eight male mice (PAS1w/m:PAS1w/w = 4:4) with three female mice (cage size: 90 × 90 cm); (4) Four male mice (PAS1c/m:PAS1c/c = 2:2) with one female mouse (cage size: 50 × 35 cm); (5) Four male mice (PAS1−/m:PAS1−/− = 2:2) with one female mouse (cage size: 50 × 35 cm).

During the test, mice were allowed to run through a transparent Plexiglas tube of 40 cm in length and 3 cm in diameter, a size just sufficient to permit one adult mouse to pass through without reversing the direction.46 There is a small chamber (17 × 8 × 14 cm) at each end of the tube for temporary housing purpose. To prepare for the test, each mouse was given eight training runs every day for 3 days. Immediately before the test, mice were given four additional training runs. During the test, two male mice of specific genotypes (for example, PAS1w/m vs. PAS1w/w) were released at each end of the tube. There is a moveable transparent Plexiglas door in the middle of the tube to ensure that the two mice meet in the middle of the tube. The mouse that retreated from the tube within 2 min was given a score of zero, and the other one that did not retreat was given a score of one.

If no mice retreated within 2 min, the test was repeated. Results were not counted if no mouse retreated in three successive trials. Between trials, the tube was cleaned with 75% ethanol. From trial to trial, the mice were released at either end alternatively. For each pair of male mice, two or three trials were conducted, and the mouse that won two times was considered the winner of the test. A new tube was employed for the next pair of mice. Mice were allowed to rest for at least 10 min between tests. To determine the stability of social ranks over time, mice were tested under the same conditions every day for 7–10 days.

For social dominance tube test of the mice with the same genotype (i.e., PAS1−/−), the procedure was the same as above. After group housing and training, social dominance tube test was performed for ten consecutive days. The mouse rank was assessed by the number of wins against cage mates.

Assessment of motor coordination, strength and balance

Motor coordination was measured by the accelerating rota-rod test as previously described.76 In the two habituation days, each mouse was placed on a 3 cm diameter rod rotating at a constant speed of 5 rpm and allowed to stay on the rota-rod for at least 5 min. For the test, each mouse was placed on the rotating rod accelerating from 5 to 60 rpm, with 1 rpm increment every 5 sec. The duration before the test mouse falling off the rota-rod was recorded.

The pole test was adapted from the behavioral test for ganglia-related movement disorders in mice.77 A vertical wooden pole (8 mm in diameter, 50 cm in height) was positioned on a base and placed in the home cage. The test mouse was placed facing down on the top of the vertical pole, and the time for the mouse to descend to the bottom was measured.

Quantification and statistical analysis

For cell transfection and RT-qPCR analysis, at least three biological replicates and three technique replicates were performed. One-tailed Student’s t test was used to analyze the results (Figs. 2, 3e–g; Supplementary information, Figs. S6–8). For in vivo transgenic mouse enhancer assays, all mouse embryos were stained for LacZ expression using standard procedures35 and then imaged with a bright field microscope (Stereoscopic Stemi 2000-C, Zeiss) to detect LacZ expression. A minimum of two embryos with the same staining pattern in at least one anatomical site was considered positive for the test (Supplementary information, Fig. S2). Whole embryo fluorescence images were acquired by lightsheet fluorescence microscopy (LSFM) (Lightsheet Z.1, Zeiss). All raw image data were collected in a lossless 16-bit TIFF format. 3D-rendered images were visualized, captured, and analyzed with the Vision4D software (version 2.12.3, Arivis). Two-tailed permutation test was used to analyze the results (Supplementary information, Tables S2–4). For the permutation test performed to analyze results of the social dominance tube test, the null hypothesis was that PAS1 does not modulate the social hierarchy. In the simulations for the permutation test, the linear social diagram was used as described previously.46 The Java source codes for the permutation test are available upon request. The difference between stable (Supplementary information, Fig. S11a, b) and unstable (Supplementary information, Fig. S11c–h) social ranks were determined by the one-tailed binomial test. The probability of social ranks being stable for seven consecutive days was determined to be 0.0417 in one cage (Supplementary information, Fig. S11c–h). Therefore, the binomial probability of two cages of mice with stable social ranks for seven consecutive days was 0.04172 ≈ 0.0017. For motor coordination, strength, and balance tests (Supplementary information, Fig. S13), two-tailed permutation test was performed using the perm.t.test function of the Deducer package in R. For weight test (Supplementary information, Fig. S14), one-way ANOVA was performed by the aov function in R.

Key resources table

Information of key resources in this study is listed in supplementary information, Table S10.

Contact for reagent and resource shareing

Mouse strains (PAS1−, PAS1w, and PAS1c) generated in this study have been donated to a repository (Shanghai Model Organisms, http://www.shmo.com.cn/) (accession numbers: NM-KO-190421, NM-KI-190001, and NM-KI-190002). The KFP software can be downloaded for free from Zenodo (10.5281/zenodo.2586471) and our institutional website (http://www.picb.ac.cn/evolgen/softwares/). Other data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Haipeng Li (lihaipeng@picb.ac.cn).

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank the following companies and individuals for their contributions to this study: Cyagen Biosciences Inc. and Shanghai Biomodel Organism Science & Technology Development Co., Ltd for generating mice; Jianping Ding, Chunxiao Zhang, Wenshuai Wang, Ya Zhao, Ligang Wu, Fangzhi Tan, Yunbo Qiao, and Jiayue Liu for technical supports; Patricia Guijarro Larraz for providing the mCherry template; Zhong-Hui Weng, Yun Qian, Fang Yu, and the animal caretaker team for assistance with animal care and experiments; Chao-Hung Lee, Ya-Ping Zhang, Cemalettin Bekpen, Diethard Tautz and Shi-Qing Cai for providing valuable advices. This work was supported by grants from the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDB13040800), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (91731304, 91531306, 31771180, and 91732106), Shanghai Municipal Science and Technology Major Project (2018SHZDZX05).

Author contributions

Y.W., G.D., Z.G., G.L., K.T., Z.S., G.W. and H.L. developed the concepts. Y.W., G.D., Z.G., G.L., K.T., Chun X., N.J. and H.L. developed the methods. H.L. programmed the software. Y.W., G.D., Z.G., G.L., H.S., Q.L., Chuan X., Y.M., Y.E.Z., P.K., Y.W. and H.L. analyzed the data. Y.W., G.D., Z.G., G.L., Y.C., H.C., S.F., S.Q., X.L., N.W. and H.L. carried out the investigation. Q.L. provided the resources. Y.W., G.D., Z.G., G.L., Y.P., Chun X. and H.L. wrote the original manuscript. Y.W., G.D., Z.G., G.L., K.T., J.H., Z.S., G.W., Y.P. and H.L. reviewed and edited the manuscript. H.L. supervised the study and acquired the funding.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

These authors contributed equally: Yuting Wang, Guangyi Dai, Zhili Gu, Guopeng Liu

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41422-020-0308-7.

References

- 1.Wang F, Kessels HW, Hu H. The mouse that roared: neural mechanisms of social hierarchy. Trends Neurosci. 2014;37:674–682. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2014.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sapolsky RM. The influence of social hierarchy on primate health. Science. 2005;308:648–652. doi: 10.1126/science.1106477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kappeler PM, Cremer S, Nunn CL. Sociality and health: impacts of sociality on disease susceptibility and transmission in animal and human societies Introduction. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B. 2015;370:20140116. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2014.0116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith CR, Toth AL, Suarez AV, Robinson GE. Genetic and genomic analyses of the division of labour in insect societies. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2008;9:735–748. doi: 10.1038/nrg2429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schjelderup-Ebbe T. Contributions to the social psychology of the domestic chicken. Zeitschrift. fuer. Psychologie. 1922;88:225–252. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Desjardins C, Maruniak JA, Bronson FH. Social rank in house mice: differentiation revealed by ultraviolet visualization of urinary marking patterns. Science. 1973;182:939–941. doi: 10.1126/science.182.4115.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dunbar RIM, Dunbar EP. Dominance and reproductive success among female gelada baboons. Nature. 1977;266:351–352. doi: 10.1038/266351a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lukas D, Clutton-Brock TH. The evolution of social monogamy in mammals. Science. 2013;341:526–530. doi: 10.1126/science.1238677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van der Kooij MA, Sandi C. The genetics of social hierarchies. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2015;2:52–57. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qu C, Ligneul R, Van der Henst JB, Dreher JC. An integrative interdisciplinary perspective on social dominance hierarchies. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2017;21:893–908. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2017.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Curley JP. Is there a genomically imprinted social brain? Bioessays. 2011;33:662–668. doi: 10.1002/bies.201100060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robinson GE, Grozinger CM, Whitfield CW. Sociogenomics: social life in molecular terms. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2005;6:257–270. doi: 10.1038/nrg1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferner K, Mess A. Evolution and development of fetal membranes and placentation in amniote vertebrates. Resp. Physiol. Neurobi. 2011;178:39–50. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2011.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luo ZX, Yuan CX, Meng QJ, Ji Q. A Jurassic eutherian mammal and divergence of marsupials and placentals. Nature. 2011;476:442–445. doi: 10.1038/nature10291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O’Leary MA, et al. The placental mammal ancestor and the Post-K-Pg radiation of placentals. Science. 2013;339:662–667. doi: 10.1126/science.1229237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Renfree MB. Review: Marsupials: placental mammals with a difference. Placenta. 2010;31((Suppl)):S21–26. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2009.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lefèvre CM, Sharp JA, Nicholas KR. Evolution of lactation: ancient origin and extreme adaptations of the lactation system. Annu. Rev. Gen. Hum. Genet. 2010;11:219–238. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-082509-141806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pollard KS, et al. An RNA gene expressed during cortical development evolved rapidly in humans. Nature. 2006;443:167–172. doi: 10.1038/nature05113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prabhakar S, Noonan JP, Pääbo S, Rubin EM. Accelerated evolution of conserved noncoding sequences in humans. Science. 2006;314:786. doi: 10.1126/science.1130738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bush EC, Lahn BT. A genome-wide screen for noncoding elements important in primate evolution. BMC Evol. Biol. 2008;8:17. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-8-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lindblad-Toh K, et al. A high-resolution map of human evolutionary constraint using 29 mammals. Nature. 2011;478:476–482. doi: 10.1038/nature10530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gittelman RM, et al. Comprehensive identification and analysis of human accelerated regulatory DNA. Genome Res. 2015;25:1245–1255. doi: 10.1101/gr.192591.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim SY, Pritchard JK. Adaptive evolution of conserved noncoding elements in mammals. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:1572–1586. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1987;4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu D, et al. eGPS 1.0: comprehensive software for multi-omic and evolutionary analyses. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2019;6:867–869. doi: 10.1093/nsr/nwz079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hartigan JA. Minimum mutation fits to a given tree. Metrics. 1973;29:53–65. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li W-H, Ellsworth DL, Krushkal J, Chang BH, Hewett-Emmett D. Rates of nucleotide substitution in primates and rodents and the generation-time effect hypothesis. Mol. Phylogenet Evol. 1996;5:182–187. doi: 10.1006/mpev.1996.0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hodgkinson A, Eyre-Walker A. Variation in the mutation rate across mammalian genomes. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2011;12:756–766. doi: 10.1038/nrg3098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dunn OJ. Multiple comparisons among means. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1961;56:52–64. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Raney BJ, et al. Track data hubs enable visualization of user-defined genome-wide annotations on the UCSC Genome Browser. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1003–1005. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hedges SB, Dudley J, Kumar S. TimeTree: a public knowledge-base of divergence times among organisms. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:2971–2972. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang D, et al. Reprogramming transcription by distinct classes of enhancers functionally defined by eRNA. Nature. 2011;474:390–394. doi: 10.1038/nature10006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Natoli G, Andrau J-C. Noncoding transcription at enhancers: general principles and functional models. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2012;46:1–19. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-110711-155459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hnisz D, et al. Super-enhancers in the control of cell identity and disease. Cell. 2013;155:934–947. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pennacchio LA, et al. In vivo enhancer analysis of human conserved non-coding sequences. Nature. 2006;444:499–502. doi: 10.1038/nature05295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rincón-Limas DE, et al. Conservation of the expression and function of apterous orthologs in Drosophila and mammals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:2165–2170. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.2165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee AP, Brenner S, Venkatesh B. Mouse transgenesis identifies conserved functional enhancers and cis-regulatory motif in the vertebrate LIM homeobox gene Lhx2 locus. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e20088. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Butler, H. & Juurlink, B. H. J. An atlas for staging mammalian and chick embryos. Boca Raton: CRC Press (1987).

- 39.Lijam N, et al. Social interaction and sensorimotor gating abnormalities in mice lacking Dvl1. Cell. 1997;90:895–905. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80354-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weinreb C, Raphael BJ. Identification of hierarchical chromatin domains. Bioinformatics. 2016;32:1601–1609. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kerpedjiev P, et al. HiGlass: web-based visual exploration and analysis of genome interaction maps. Genome Biol. 2018;19:125. doi: 10.1186/s13059-018-1486-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Feige E, Motro B. The related murine kinases, Nek6 and Nek7, display distinct patterns of expression. Mech. Dev. 2002;110:219–223. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(01)00573-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xu Y, et al. LH-2: A LIM/homeodomain gene expressed in developing lymphocytes and neural cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:227–231. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.1.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Susaki EA, et al. Advanced CUBIC protocols for whole-brain and whole-body clearing and imaging. Nat. Protoc. 2015;10:1709–1727. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2015.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lindzey G, Winston H, Manosevitz M. Social dominance in inbred mouse strains. Nature. 1961;191:474–476. doi: 10.1038/191474a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang F, et al. Bidirectional control of social hierarchy by synaptic efficacy in medial prefrontal cortex. Science. 2011;334:693–697. doi: 10.1126/science.1209951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fan Z, et al. Using the tube test to measure social hierarchy in mice. Nat. Protoc. 2019;14:819–831. doi: 10.1038/s41596-018-0116-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dwyer ND, et al. Neural stem cells to cerebral cortex: emerging mechanisms regulating progenitor behavior and productivity. J. Neurosci. 2016;36:11394–11401. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2359-16.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chou S-J, Tole S. Lhx2, an evolutionarily conserved, multifunctional regulator of forebrain development. Brain Res. 2019;1705:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2018.02.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Metz CW. An apterous Drosophila and its genetic behavior. Am. Nat. 1914;48:675–692. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Porter F, et al. Lhx2, a LIM homeobox gene, is required for eye, forebrain, and definitive erythrocyte development. Development. 1997;124:2935–2944. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.15.2935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hsu LC-L, et al. Lhx2 regulates the timing of beta-catenin-dependent cortical neurogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:12199–12204. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1507145112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mangale VS, et al. Lhx2 selector activity specifies cortical identity and suppresses hippocampal organizer fate. Science. 2008;319:304–309. doi: 10.1126/science.1151695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Muralidharan B, et al. Dmrt5, a novel neurogenic factor, reciprocally regulates Lhx2 to control the neuron-glia cell-fate switch in the developing hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 2017;37:11245–11254. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1535-17.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thor S, Andersson SGE, Tomlinson A, Thomas JB. A LIM-homeodomain combinatorial code for motor-neuron pathway selection. Nature. 1999;397:76–80. doi: 10.1038/16275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Monahan K, Horta A, Lomvardas S. LHX2- and LDB1-mediated trans interactions regulate olfactory receptor choice. Nature. 2019;565:448–453. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0845-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wilson SI, Shafer B, Lee KJ, Dodd J. A molecular program for contralateral trajectory: Rig-1 control by LIM homeodomain transcription factors. Neuron. 2008;59:413–424. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang C-F, et al. Lhx2 expression in postmitotic cortical neurons initiates assembly of the thalamocortical somatosensory circuit. Cell Rep. 2017;18:849–856. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rienecker KDA, Chavasse AT, Moorwood K, Ward A, Isles AR. Detailed analysis of paternal knockout Grb10 mice suggests effects on stability of social behavior, rather than social dominance. Genes Brain Behav. 2019;19:e12571. doi: 10.1111/gbb.12571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Saxena K, et al. Experiential contributions to social dominance in a rat model of fragile-X syndrome. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2018;285:20180294. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2018.0294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Watanabe N, Yamamoto M. Neural mechanisms of social dominance. Front. Neurosci. 2015;9:154. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2015.00154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhou TT, Sandi C, Hu HL. Advances in understanding neural mechanisms of social dominance. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2018;49:99–107. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2018.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhou TT, et al. History of winning remodels thalamo-PFC circuit to reinforce social dominance. Science. 2017;357:162–168. doi: 10.1126/science.aak9726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bendesky A, et al. The genetic basis of parental care evolution in monogamous mice. Nature. 2017;544:434–439. doi: 10.1038/nature22074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kappeler PM. Lemur behaviour informs the evolution of social monogamy. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2014;29:591–593. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2014.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Valomy M, Hayes LD, Schradin C. Social organization in Eulipotyphla: evidence for a social shrew. Biol. Lett. 2015;11:20150825. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2015.0825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Remes V, Freckleton RP, Tokolyi J, Liker A, Szekely T. The evolution of parental cooperation in birds. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:13603–13608. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1512599112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.van der Kooij MA, Sandi C. Social memories in rodents: methods, mechanisms and modulation by stress. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2012;36:1763–1772. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2011.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Blanchette M, et al. Aligning multiple genomic sequences with the threaded blockset aligner. Genome Res. 2004;14:708–715. doi: 10.1101/gr.1933104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Graur, D. & Li, W. H. Fundamentals of Molecular Evolution. 2nd edn. Sinauer Associates (2000).

- 71.Ohta T, Kimura M. On the constancy of the evolutionary rate in cistrons. J. Mol. Evol. 1971;1:18–25. doi: 10.1007/BF01659391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tajima F, Nei M. Estimation of evolutionary distance between nucleotide sequences. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1984;1:269–285. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]