Abstract

Tyrosine phosphorylation is a critical component of signal transduction for multicellular organisms, particularly for pathways that regulate cell proliferation and differentiation. While tyrosine kinase inhibitors have become FDA-approved drugs, inhibitors of the other important components of these signaling pathways have been harder to develop. Specifically, direct phosphotyrosine (pTyr) isosteres have been aggressively pursued as inhibitors of Src homology 2 (SH2) domains and protein tyrosine phosphatases (PTPs). Medicinal chemists have produced many classes of peptide and small molecule inhibitors that mimic pTyr. However, balancing affinity with selectivity and cell penetration has made this an extremely difficult space for developing successful clinical candidates. This review will provide a comprehensive picture of the field of pTyr isosteres, from early beginnings to the current state and trajectory. We will also highlight the major protein targets of these medicinal chemistry efforts, the major classes of peptide and small molecule inhibitors that have been developed, and the handful of compounds which have been tested in clinical trials.

INTRODUCTION

This review provides a historical perspective of the development of phosphotyrosine (pTyr) isosteres to inhibit Src Homology 2 (SH2) domains and protein tyrosine phosphatases (PTPs). These protein classes remain largely elusive to small molecule therapeutics, with no clinically approved inhibitors despite many clinical trials. Other modalities are currently being pursued for these targets, most notably antisense oligonucleotides and allosteric inhibitors; these have largely replaced strategies involving pTyr isosteres, at least in industry. From the initial phosphonates to more sophisticated molecules that are still being tested in clinical trials, we summarize how this field has grown and transformed over the years, and how close this field may be to inhibiting these biomedically relevant targets in the clinic.

SH2 Domains and PTPs: Structure and Function

Since the identification of the Src Homology 2 (SH2) domain in 1986 by Pawson and colleagues, there have been continuous efforts to understand the biological functions and mechanisms of human SH2 domains.1 Shortly after the initial discovery, it was shown that SH2 domains recognize phosphorylated tyrosine residues and mediate pTyr signaling within many important pathways.2 There are over 110 human proteins with SH2 domains, and their biological functions are quite diverse.3,4 SH2 domain-containing proteins are dysregulated in nearly all categories of human disease, including many cancers.3,4 Thus, to advance both basic understanding and drug development, finding inhibitors that specifically target a single SH2 domain has been an overarching goal over the last 20 years.

In 1992, the first crystal structure of an SH2 domain bound to a phosphopeptide ligand revealed the molecular details of SH2 domain molecular recognition. The domain is comprised of a central, multi-stranded β-sheet connected by several loop regions and flanked by two α-helices.5,6 This tertiary structure forms two separate binding pockets: one that recognizes pTyr and a secondary pocket that recognizes amino acids near the pTyr residue (typically, C-terminal to the pTyr). The field was further propelled by investigations into the specificity determinants of different SH2 domains. Notably, an initial study in 1990 by Cantley and colleagues used a phosphopeptide library to characterize the selectivity motifs of over a dozen SH2 domains.7 Since then, a wealth of data from library screening and in vitro binding studies has confirmed that, for the majority of natural SH2 ligands, the residues C-terminal to pTyr are the primary determinant of binding specificity. As the structural basis for the specificity of different SH2 domains became clear, the field’s focus shifted to developing pharmacological inhibitors capable of engaging both the pTyr and specificity pockets.

Also in the early 1990’s, similar structural and functional information was being uncovered for protein tyrosine phosphatases (PTPs). PTPs recognize pTyr-containing sequences and hydrolyze the phosphate. Early experiments highlighted the importance of a highly conserved cysteine residue for catalysis;8 this cysteine resides in a conserved “PTP loop,” VHCSXGXGR[T/S]G. The cysteine acts as a nucleophile that displaces the phosphate, generating a thiophosphate intermediate that is stabilized by the PTP loop arginine.8–10 Selectivity for pTyr over phosphothreonine and phosphoserine is mediated by a conserved “pTyr recognition loop,” KNRY, which lines the bottom of the catalytic cleft and interacts with the pTyr phenyl ring.9,11 Also required is the highly conserved “WPD loop,” WPDXGXP, which helps trap the substrate within the active site, then undergoes a conformational change to assist with hydrolysis of the thiophosphate intermediate.12,13 Understanding the mechanism of pTyr hydrolysis by PTPs paved the way for the design and screening of small molecule inhibitors.

SH2 Domains and PTPs: Therapeutic Targets

While many SH2 domains and PTPs have been the subject of inhibitor design, this review will focus on the protein targets that have received the most attention. Inhibitors of most of these proteins have been tested in clinical trials, but none have yet achieved FDA approval.

Protein tyrosine phosphatase-1B (PTP1B) has long been an enticing biological target because of its critical role in type 2 diabetes and metabolic disease (Fig. 1a). Early work injecting PTP1B into Xenopus oocytes revealed that PTP1B inhibited insulin-stimulated tyrosine phosphorylation of multiple proteins.14 This led to further investigation into PTP1B’s role as a regulator of insulin signaling. For example, while wild-type mice on high-fat diets gain weight and become insulin-insensitive, PTP1B-null and heterozygous mice maintain insulin sensitivity and resist weight gain.15 Additionally, PTP1B deletion reduces fat cell mass, increases basal metabolic rate, and increases total energy expenditure.16

Figure 1. Roles of selected SH2 Domains and PTPs in signal transduction.

(a) PTP1B regulates insulin and leptin signaling. PTP1B is capable of dephosphorylating both the insulin receptor and insulin receptor substrates, resulting in reduced Akt activation and ultimately reduced activity of the glucose transporter Glut4, Glycogen Synthase Kinase-3, and other proteins involved in glucose metabolism. Additionally, PTP1B can dephosphorylate JAK2 for modulation of leptin receptor signaling, resulting in increased food intake and altered energy homeostasis. (b) SHP2, Grb2, and Grb7 mediate Ras-family pathways responsible for cell growth, survival, and migration. SHP2 can enhance Ras and ultimately MAPK signaling through the deactivation of Ras GTPase-activating protein (GAP) and the C-terminal Src Kinase (Csk). Both Grb2 and Grb7 also promote Ras activation. Grb2, which binds phosphorylated EGFR through its SH2 domain, activates Ras by recruiting the guanine nucleotide exchange factor Sos1. Grb2 and Grb7 also bind phosphorylated Focal Adhesion Kinase (FAK). When Grb2 binds to FAK, it recruits Sos1 and activates Ras (not shown). When Grb7 binds to FAK, it recruits the guanine nucleotide exchange factor Vav2, resulting in activation of Rac1 which promotes cell migration. In this way, adaptor proteins like Grb2 and Grb7 couple growth factor and integrin signaling with cell proliferation, survival and migration. (c) STAT3 phosphorylation and dimerization mediates cytokine signaling. JAK tyrosine kinases are activated by the binding of cytokines such as IL-6 to their corresponding receptor. The IL-6-bound receptor is in complex with phosphorylated gp130, which recruits STAT3 to the plasma membrane via STAT3’s SH2 domain. STAT3 is then phosphorylated by JAK, and phosphorylated STAT3 can dimerize to form the active transcription factor. Dimeric STAT3 translocates to the nucleus, where it upregulates signaling pathways that promote tumorigenesis, angiogenesis, apoptotic evasion, migration, and immune evasion.

Another important phosphatase, the Src homology 2 domain-containing phosphatase 2 (SHP2, encoded by the human PTPN11 gene), has been implicated in numerous conditions. SHP2 plays a key role in the regulation of Ras signaling (Fig. 1b), PI3K-Akt signaling, NF-κB signaling, and several other cancer-relevant pathways, so it is not surprising that numerous cancers display hyperactivation of this phosphatase.17 In recent years it has been shown that receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK)-driven cancers are susceptible to SHP2 inhibition.18 Further, mutations in PTPN11 which result in SHP2 hyperactivity are causative for Noonan Syndrome as well as Juvenile Myelomonocytic Leukemia.19,20 These and other findings have made SHP2 an important target for drug discovery.

In addition to tyrosine phosphatases, numerous adaptor proteins containing SH2 domains have been pursued as promising pharmacological targets. One of the first adaptor proteins to be targeted pharmacologically was the Growth Factor Receptor Binding Protein 2 (Grb2), which links EGFR-dependent signaling and Ras activation (Fig. 1b).21 Grb2’s SH2 domain allows it to bind the intracellular domain of ErbB family RTKs, including EGFR and HER2/neu, where it recruits the nucleotide exchange factor Sos1.22 Grb2 is required for polyoma middle T antigen-induced malignant transformation of mammary cells, and through its interaction with Focal Adhesion Kinase (FAK), is an important link between the extracellular matrix and the Ras/MAPK pathway.23–25 Similarly, the Growth Factor Receptor Binding Protein 7 (Grb7) has also been shown to bind to ErbB family RTKs through its SH2 domain; Grb7 is co-amplified and overexpressed in numerous invasive breast cancer cell lines and adenocarcinoma patient tumor samples, particularly HER2-positive and ER-negative carcinomas.26–28 In addition, the interaction of Grb7 with FAK results in Ras-dependent cell proliferation and Rac1-dependent cell migration (Fig. 1b).29,30 These and other data highlight the importance of Grb2, Grb7, and similar adaptor proteins in growth factor signaling, cell migration, and metastasis.31–33

SH2-domain-containing transcription factors have also emerged as promising targets for cancer therapeutics, most notably the Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3 (STAT3, Fig. 1c). STAT3 is part of the canonical cytokine signaling pathway. When extracellular cytokines such as IL-6 bind their corresponding receptors, the receptors activate JAK family kinases.34,35 STAT3 monomers are recruited to the membrane via their SH2 domain and then phosphorylated by JAKs. Following phosphorylation, STAT3 dimerizes via the same SH2 domain. Dimeric STAT3 then translocates to the nucleus, where it upregulates numerous STAT3 target genes, many of which are central to the hallmarks of cancer.34,35 For instance, STAT3 induces angiogenesis and tumor growth through expression of vascular endothelial growth factor, enhances tumor invasiveness and metastasis through expression of matrix metalloproteinase-2, and promotes evasion of cell death through expression of antiapoptotic proteins including survivin, Bcl-2, and Bcl-xL.36–39 STAT3 was shown to be necessary for malignant transformation of mouse fibroblasts, but not for normal fibroblast growth.40 These data suggest a promising therapeutic window as a cancer target. Even more recently, STAT3 was shown to upregulate PD-1 and PD-L1 expression, suggesting that STAT3 inhibitors might be synergistic with widely used checkpoint inhibitors.41 STAT3, and each of the proteins listed above, continue to be the focus of drug development because of the abundant data that suggest that they are key modifiers of human disease.

PEPTIDES AND PEPTIDOMIMETICS CONTAINING PTYR ISOSTERES

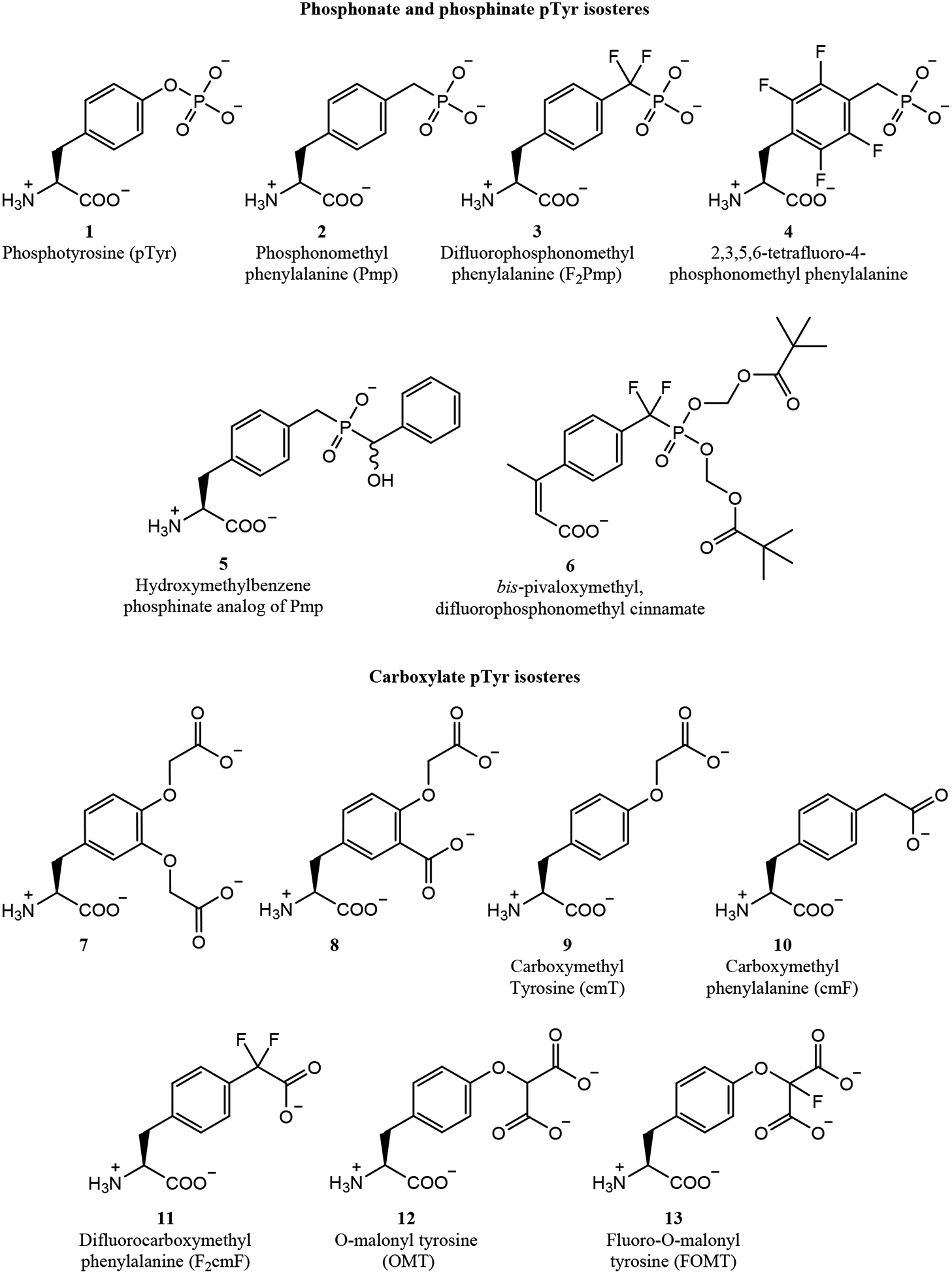

Phosphonates

In the early 1990s, just 6 years after the identification of the SH2 domain by Pawson and colleagues, the first pTyr-mimicking inhibitors were described. It was clear that inhibiting SH2 domains with analogs of pTyr (1) would require increased stability against PTPs and better cell penetration. The first class of pTyr isosteres, phosphonates, replaced the phosphate bridging oxygen with a methylene unit (Fig. 2). This modification ensured that these pTyr isosteres would be stable to hydrolysis by phosphatases. Shoelson, Burke and co-workers reported the first peptide inhibitor containing a phosphonomethyl phenylalanine residue (Pmp, 2).42 Their target was the N-terminal SH2 domain of phosphatidyl inositol-3 kinase (PI-3K), which is involved in proliferation, differentiation, and survival, and which is constitutively activated in numerous cancers.43 They developed a Pmp-containing peptide derived from the PI-3K binding partner pp60c-src-phosphorylated middle T antigen (mT). The phosphopeptide bound to the PI-3K N-terminal SH2 domain with a KD of 10 nM and the phosphonate-containing peptide bound with a KD of 20 nM. They next compared the phosphonopeptide with the parent phosphopeptide for PI-3K inhibition in mouse 3T3 fibroblast cell lysates. In the presence of sodium vanadate, a potent PTP inhibitor, both peptides inhibited the PI-3K/mT interaction, with IC50 values of 100 nM and 800 nM for the phosphopeptide and phosphonopeptide, respectively. When vanadate was omitted, the phosphopeptide lost all activity while the phosphonopeptide maintained inhibitory potency. This finding highlighted the importance of ensuring that pTyr isosteres were non-hydrolyzable, and it encouraged wider exploration of peptides and peptidomimetics with pTyr isosteres to inhibit SH2 domains and PTPs.

Figure 2.

Phosphonate and carboxylate amino acids for incorporation into peptide and peptidomimetic inhibitors.

To overcome the loss in affinity seen with Pmp-containing peptides, Burke and colleagues made more sophisticated pTyr analogs including fluoro-, difluoro-, and hydroxy-Pmp.44,45 For example, the difluoro-Pmp analog (F2Pmp, 3) was incorporated into a hexapeptide substrate of the PTP1B phosphatase, producing a PTP1B inhibitor with 1000-fold greater potency than the Pmp-containing peptide (IC50 values of 100 nM and approximately 100 μM, respectively).44 This large difference highlighted the importance of hydrogen bonding of the phosphate’s bridging oxygen for molecular recognition by PTPs, and the effectiveness of the fluorine atoms as electron-withdrawing groups to mimic this pharmacophore.45 Burke, Shoelson and colleagues incorporated F2Pmp into peptides targeting the C-terminal SH2 domain of PI-3K, the Src SH2 domain, and the Grb2 SH2 domain.46 Interestingly, the F2Pmp-containing peptides differed in their relative binding affinities. While the PI-3K F2Pmp peptide exhibited similar binding affinity as the native phosphopeptide (170 nM vs. 150 nM), the Grb2 peptide lost 5-fold affinity compared to pTyr, and the Src peptide gained 5.7-fold affinity compared to pTyr. While the F2Pmp isostere has been incorporated into many peptide, peptidomimetic, and even small molecule inhibitors,47–50 it is notable that different SH2 domains and phosphatases tolerate this pTyr isostere to different extents.

Other phosphonate-based pTyr isosteres have been incorporated into peptidomimetic inhibitors. Roques and colleagues developed 4, a Pmp analog with a tetrafluorobenzene group. However, peptides with this residue had nearly 10-fold lower affinity for the Grb2 SH2 domain compared to analogous peptides with Pmp.51 Furet, Walker and colleagues at Novartis developed alkyl- and aryl-substituted Pmp analogs, which were phosphinates with reduced negative charge.52,53 Testing these analogs in peptide inhibitors of Grb2, they identified hydroxybenzyl phosphinate 5 which bound more tightly than the initial phosphonate (KD of 0.53 μM).52 This represented a relatively high-affinity pTyr isostere, especially considering it had reduced negative charge, which was anticipated to improve cell penetration.

In more recent years, phosphonate-containing pTyr analogs have continued to be developed. For example, McMurray and colleagues developed peptidomimetics containing a 4-phosphonodifluoromethylcinnamate, and further enhanced cell penetration by masking the phosphonate hydroxyls with reversible pivaloyloxymethyl protecting groups (6).54–58 One such peptidomimetic inhibited the STAT3 SH2 domain with an IC50 of 162 nM, and inhibited STAT3 phosphorylation in MDA-MB-468 breast cancer cells at 10 μM.54 After further structure-activity relationships, a second-generation peptidomimetic containing isostere 6 inhibited intracellular STAT3 phosphorylation at 100 nM in MDA-MB-468 cells.55 Impressively, these peptidomimetics were selective for STAT3, with no inhibition of the STAT5 SH2 domain and 10-fold selectivity over the STAT1 SH2 domain, which is highly homologous.

Carboxylates

Phosphonates were appealing pTyr isosteres but almost always presented problems with cell penetration. To explore pTyr isosteres with different overall net charges and charge distributions, Burke and colleagues explored pTyr isosteres containing one or two carboxylate groups, such as 7 and 8 (Fig. 2).59–61 pTyr isosteres with only one carboxylate group were universally poor pTyr isosteres.

Monocarboxylate derivatives with reduced negative charge such as carboxymethyl tyrosine (cmT, 9), carboxymethyl phenylalanine (cmF, 10), and difluorocarboxymethyl phenylalanine (F2cmF, 11) were incorporated into Grb2- and PTP1B-targeted peptides, but incorporation of these isosteres resulted in a 5- to 50-fold loss in potency.62–64 Even with additional structure-guided design, affinities approaching the natural pTyr ligand were not achieved using any monocarboxylate isostere. Better results were observed with selected pTyr isosteres with two carboxylates, most notably the dicarboxylate pTyr isostere O-malonyl tyrosine (OMT, 12).59,60 When OMT was incorporated into a PTP1B substrate, the resulting inhibitor was only 3-fold less potent than the analogous pTyr-containing peptide. Similar to results with fluorine-substituted phosphonates, Burke and colleagues found that incorporating a fluoro-OMT residue (13) led to a 10-fold improvement in binding affinity.65 Interestingly, when OMT was incorporated into peptide ligands of the SH2 domains of PI-3K, Src, and Grb2, the inhibitors were 10- to 100-fold less potent than the native pTyr-containing peptides. This suggested that OMT analogs may only be useful for PTPs or a subset thereof, and may be less useful for inhibiting SH2 domains.65

Other groups have also explored carboxylate-containing pTyr isosteres. Tong and colleagues at Boehringer Ingelheim prepared peptides incorporating carboxymethyl phenylalanine (cmF) as inhibitors of the Lck SH2 domain.66 A crystal structure of the cmF-containing peptide bound to the Lck SH2 domain revealed a similar binding mode compared to the native phosphopeptide (Fig. 3a). Interestingly, the cmF carboxylate interacted with the side chains of Lck R134, R154, and S156, as well as with the backbone nitrogen of E157 - this corresponds to the binding site for the pTyr phosphate group. Despite this extremely similar mode of binding, the cmF-containing peptide displayed a 500-fold poorer binding affinity than the native pTyr-containing peptide. In separate work, Larsen and colleagues incorporated various carboxylate pTyr isosteres into PTP1B-inhibiting peptides, producing inhibitors with IC50 values as low as 220 nM.67,68 However, these inhibitors produced a modest phenotype when applied in cell culture, requiring concentrations of 100 μM of their two most potent inhibitors to increase 2-deoxyglucose uptake of insulin-stimulated L6 myocytes by 30–40%.68 This modest phenotype was most likely due to poor cell penetration.

Figure 3. Crystal structures of selected pTyr isosteres bound to SH2 domains and PTP active sites.

(a) cmF-containing peptide bound to the Lck SH2 domain.66 (b) Oxalylamino acid-containing small molecule 17 bound to the PTP1B active site (open conformation); the inhibitor’s naphthyl carboxylate binds a secondary pTyr binding site.69 (c) Salicylate 22 bound to the active site of SHP2 (open conformation).70 (d) Benzyl sulfonate-containing small molecule inhibitor, similar to 44, bound to the active site of SHP2 (open conformation).71 (e) Thiophene-containing small molecule inhibitor 48 bound to the active site of PTP1B (closed conformation); the inhibitor’s benzyl sulfonamide binds a secondary pTyr binding site.72 (f) Bicyclic, cF-containing peptide 58 bound to the Grb7 SH2 domain.73

SMALL MOLECULES CONTAINING PTYR ISOSTERES

Peptide and peptidomimetic approaches to SH2 and PTP inhibition produced several micromolar to mid-nanomolar inhibitors, but nearly all these inhibitors performed poorly in cell-based assays. Though direct measurement of cell penetration was challenging, the most common assumption was that peptides and peptidomimetics with pTyr isosteres had poor cytosolic penetration. Thus, initial findings with peptidomimetics led to increased focus on small molecule inhibitors, with the rationale that they might act as pTyr isosteres but with better cytosolic penetration. As described in this section, this proved to be the case. However, smaller inhibitors often showed little discrimination between target proteins and close homologs. Thus, testing selectivity among related SH2 domains and PTPs became critical to the development of pTyr-mimicking small molecules.

Oxalylamino Acids

Oxalylamino acid derivatives were first identified as phosphate isosteres by Andersen, Møller and colleagues.74 In a screen of a Novo Nordisk compound library, oxalylaminobenzoic acid (OBA, 14) was identified as a weak PTP1B inhibitor (IC50 of 200 μM). With the aid of several crystal structures, they designed oxalylamino thiophene 15 with improved affinity and selectivity, with an IC50 value of 5.1 μM and 160- to 400-fold selectivity for PTP1B compared to other PTPs tested.75 Selectivity to the T-cell protein tyrosine phosphatase (TC-PTP), which shares 80% sequence homology with PTP1B in the catalytic domain, was not reported. Subsequent work produced 16, which had an improved IC50 of 3.2 μM and 650-fold selectivity for PTP1B over most PTPs tested, but only 2-fold selectivity over TC-PTP.76

Oxalylamino acid pTyr isosteres were independently identified as PTP1B inhibitors by Szczepankiewicz and colleagues at Abbott Laboratories in 2003.69 An initial hit from an NMR-based screen was developed with SAR-by-NMR development methods into 17, a relatively potent inhibitor (KD value of 22 nM). Crystal structures revealed several key similarities and differences in the binding mode of 17 compared to native pTyr (Fig. 3b). Typically, upon pTyr or pTyr isostere binding to a PTP, the WPD loop moves into the closed conformation. However, 17 bound the PTP1B active site with the WPD loop in its open conformation. The open conformation was stabilized through the interaction of the benzylic carboxylate with R221, and by hydrophobic interactions between the benzene ring and the Q262 side chain. However, the oxalyl moiety occupied the same position as the native phosphate, and the naphthyl rings occupied a similar position as the pTyr phenyl ring. Additionally, crystal structures highlighted that, as intended, the inhibitor engaged a less-conserved secondary pTyr binding site initially discovered by Zhang and colleagues.77 This was achieved through using a diamide linker to position a naphthyl carboxylate in this pocket, where it engaged with the side chains of R254 and Y20. Similar to the Novo Nordisk inhibitors, the Abbott inhibitors showed impressive selectivity over several other PTPs tested, but (even after subsequent development78) only modest selectivity for PTP1B over TC-PTP.

Oxalylamino acids have been most successful in efforts targeting PTP1B, but they have also been employed as pTyr isosteres to develop inhibitors of other targets. For example, Beaulieu and colleagues at Boehringer Ingelheim generated dipeptide inhibitors of the SH2 domain of p56lck in which the native pTyr residue was directly substituted with an oxalylaminobenzoic acid, producing an inhibitor with an IC50 value of 3 μM.79 Alber and colleagues screened a library of oxamic acid compounds and identified oxalylamino thiophene 18 that inhibited the Mycobacterium tuberculosis phosphatase PtpB with an IC50 of 440 nM, with over 60-fold selectivity over several human PTPs tested.80 While they are important early examples of small molecule pTyr isosteres, oxalylamino acids were superseded in the mid-2000’s by isosteres with higher affinity and lower charge, including salicylates and sulfonamides.

Salicylates and related compounds

In 2003, Liu, Pei and colleagues at Abbott Laboratories used SAR-by-NMR and structure-based design to develop salicylates as PTP1B inhibitors.81,82 One of the most potent inhibitors discovered in this manner was compound 19, which used an oxyacetic acid moiety to bind the active site and a salicylic methyl ester to bind the secondary site.81,82 This compound inhibited PTP1B with a Ki of 180 nM. It had unprecedented selectivity for a small molecule, with greater than 12-fold selectivity for PTP1B over TC-PTP and greater than 30-fold selectivity for PTP1B over four additional human PTPs tested. Though not a salicylate, the oxyacetic acid responsible for binding the active site inspired further PTP1B-inhibiting derivatives from Cho and colleagues, who developed carboxymethylpyrogallol 20 which inhibited PTP1B with an IC50 of 1.1 μM and exhibited 7-fold selectivity for PTP1B over TC-PTP.83 Impressively, this molecule significantly lowered fasting blood glucose and improved glucose tolerance in high-fat dietinduced diabetic mice.

Mustelin and colleagues identified several salicylate-containing molecules from a high-throughput screen for inhibitors of the Yersinia PTP YopH.84 Subsequent optimization produced YopH inhibitor 21 with a Ki of 180 nM and 13- to 500-fold selectivity over other phosphatases. With no additional carboxylates or pTyr isosteres, these compounds further demonstrated that salicylates could be potent and selective phosphatase inhibitors. The PTP SHP2 was also the target of several salicylate-based inhibitors.70,85 Zhang and colleagues generated a 212-member combinatorial salicylate library, and identified compound II-B08 (22), capable of inhibiting SHP2 with an IC50 of 5.5 μM with 3-fold selectivity over SHP1 and PTP1B.70 A crystal structure revealed the SHP2 binding mode for this inhibitor (Fig. 3c). The salicylate occupied the SHP2 active site and engaged with the P-loop, pTyr recognition loop, and WPD loop. However, similar to the oxalyl inhibitor 16, 22 bound with the WPD loop in its open conformation. This was a result of simultaneous interactions with P-loop R465 and WPD loop W423, preventing WPD loop closure. In subsequent work, the authors further pursued a structure-guided, fragment-based library approach to improve upon 22. Their most potent compound (11a-1, 23) inhibited SHP2 with an IC50 of 200 nM and 7- and 11-fold selectivity for SHP2 over SHP1 and PTP1B, respectively.85

In 2007, Turkson and colleagues reported inhibitors of the STAT3 SH2 domain identified from a virtual screen.86 Their best hit was S3I-201 (24), a salicylate with an IC50 of 86 μM in an assay measuring STAT3 binding to DNA. Despite this relatively poor inhibitory potency, S3I-201 inhibited tumor growth in mice in an MDA-MB-231 human xenograft breast tumor model when administered intravenously at 5 mg/kg every 2–3 days for 16 days. Further analysis showed a significant reduction in STAT3 dimerization within treated tumors, supporting SH2 inhibition as the compound’s mode of action.86 Further work in collaboration with Gunning and colleagues produced improved analogs via rational and computer-aided design.87–89 Their most optimized analog, BP-1–102 (25) had a KD of 504 nM, an IC50 of 4.1 μM for inhibiting the STAT3-phosphopeptide interaction, and roughly 7-fold selectivity for STAT3 over STAT1 and STAT5.89 It also inhibited tumor growth in mouse xenograft models of human breast and non-small cell lung cancers when administered intravenously at 1 and 3 mg/kg. Impressively, this molecule showed similar tumor growth inhibition when given by oral gavage at 3 mg/kg daily. Working from a different isomer than the 4-amino-2-hydroxybenzoic acid of S3I-201, Lawrence, Sebti and colleagues developed unique salicylates containing a 5-amino-2-hydroxybenzoic acid group.90,91 However, their optimized inhibitor, 26, had a poorer IC50 (15 μM) and was only capable of inhibiting intracellular STAT3 dimerization and STAT3 transcriptional activity at relatively high concentrations (100–200 μM). Gunning, Tremblay and colleagues also studied salicylates as PTP1B inhibitors.92,93 They generated several inhibitors, the best of which (27) inhibited PTP1B with an IC50 of 1.7 μM; however, despite using multiple salicylates to target both pTyr-binding pockets, these compounds were not selective for PTP1B over TC-PTP.93

Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) is an aggressive brain malignancy which is often characterized by constitutive STAT3 activation. Thus, GBM represents an important possible therapeutic indication for STAT3 inhibitors.94 Gunning, Weiss and colleagues utilized BP-1–102 as a starting point to develop compounds more effective for GBM.95 One inhibitor, SH-4–54 (28), differed from their starting point only by the removal of the salicylate hydroxyl group, but it had improved STAT3 affinity (KD of 300 nM). This compound was the most potent analog when measuring effects on cell viability in several glioblastoma brain tumor-derived stem cell lines, with IC50 values ranging from 66 to 234 nM. Importantly, this molecule exhibited no nonselective neurotoxicity when tested on normal human fetal astrocytes. Further, SH-4–54 inhibited STAT3 activation and tumor growth in an orthotopic GBM mouse model.95 In subsequent work, Gunning, Fishel and colleagues screened an additional 52 salicylic and benzoic acid compounds derived from this inhibitor against pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cell lines, and identified, PG-S3–001 (29, a benzoate rather than a salicylate) as the most potent.96 All together, these works highlight an important trend for STAT3 SH2 domain inhibitors, where benzoates can be developed with better affinity than salicylates.

Gunning, Minden and colleagues also developed salicylates into potent inhibitors of the STAT5B SH2 domain.97,98 Using docking and a focused compound library, their best salicylate inhibitor had a KD of 42 nM for STAT5B and 7-fold selectivity over STAT3. Further development produced benzoic acid analog AC-4–130 (30), which inhibited STAT5B phosphorylation at 1 μM in Ba/F3 FLT3-ITD+ cells and completely inhibited STAT5 transcriptional activity at 5 μM.99 No STAT1 inhibition and only 30–40% inhibition of STAT3 was observed in cell-based assays at 5 μM. AC-4–130 was further shown to reduce tumor volume in mouse xenografts of MV-411 AML cells when delivered intraperitoneally at 25 mg/kg daily. No hematopoietic defects were observed in wild-type mice, suggesting a reasonable degree of STAT5B selectivity. As with STAT3, it appears that benzoates may prove better for targeting STAT5 than salicylates.

Sulfonamides

Another predominant class of pTyr isosteres has been the sulfonamides (Fig. 5). In some of the earliest work using sulfonamides as PTP inhibitors, Seto and colleagues rationalized that the geometry of arylsulfonamides is similar to that of arylphosphates, but with reduced negative charge.100 They generated a benzylsulfonamide-containing hexameric peptide (31) which inhibited the Yersinia PTP YopH with an IC50 of 370 μM, while inhibiting PTP1B with an IC50 of over 2500 μM. Combs and colleagues at Incyte Corporation similarly used sulfonamides as inhibitors of PTPs, designing a sulfonamide-containing isothiazolidinone as a pTyr isostere. When incorporated into a PTP1B-targeted peptide, the isothiazolidinone inhibited PTP1B with an IC50 of 190 nM.101 In subsequent work, the authors improved the drug-likeness of the surrounding peptide, resulting in an inhibitor (32) with an IC50 of 35 nM that produced a 2.3-fold increase in insulin receptor phosphorylation in HEK293 cells when applied at 80 μM.102 These pTyr isosteres demonstrated impressive affinities, but they still required very high concentrations to affect PTP1B-dependent phenotypes in cell culture. While cytosolic localization was not measured directly, the implication was that these molecules were poorly cell-penetrant.

Figure 5.

(next page) Salicylate and benzoate inhibitors of PTP and SH2 domains, and related analogs.

In search of a STAT3 dimerization inhibitor, Lin and colleagues performed a virtual screen of a 429,000-member small molecule library by docking in the STAT3 SH2 domain. Testing the top 100 hits from this virtual library in a luciferase-dependent STAT3 transcriptional reporter assay, they identified STA-21 (33), which reduced STAT3 activity by over 80% at 20 μM.103 Co-immunoprecipitation experiments showed that STA-21 inhibited STAT3 homodimerization at 20 μM in MDA-MB-435 breast cancer cells. Additionally, STA-21 induced apoptosis in several STAT3-dependent breast cancer cell lines, but not in several breast cancer cell lines without constitutive STAT3 signaling. In a subsequent study, the authors demonstrated that 30 μM STA-21 induced apoptosis in multiple STAT3-dependent rhabdomyosarcoma and bladder cancer cell lines, but not healthy human skeletal myoblasts or bladder smooth muscle cells.104,105 STA-21 was not a sulfonamide, but the sulfonamide isostere was incorporated into a subsequent analog, LLL12 (34), which proved significantly more potent.106 LLL12 exhibited IC50 values ranging from 0.16 to 3 μM across multiple pancreatic cancer, breast cancer, and glioblastoma cell lines. The authors demonstrated the efficacy of LLL12 in numerous STAT3-dependent cancers in vitro and in vivo, including hepatocellular carcinoma, medulloblastoma, pancreatic cancer, and multiple myeloma.107–110 While LLL12 has not moved beyond preclinical studies, its precursor STA-21 has. In addition to the anticancer properties initially demonstrated by Lin and colleagues, STA-21 was shown to reduce autoimmune inflammation in mouse models of rheumatoid arthritis,111,112 and it improved psoriatic skin lesions in mouse models of psoriasis when applied topically.113 Topical treatment of STA-21 in psoriasis was later tested in a phase I/II clinical trial, and while efficacy was exhibited, further clinical study was not pursued.113 While efficacious as a topical treatment for psoriasis, STA-21 may not have represented an improvement over the current standard-of-care to merit further clinical development.

Fragment-based approaches have also been used to develop potent sulfonamide inhibitors of STAT3’s SH2 domain. In 2013, Li and colleagues identified a sulfonamide as an inhibitor of the STAT3 SH2 domain using an in silico fragment-based design approach.114 This approach started with libraries of previously identified STAT3 binders, organized them into sub-libraries based on their binding site, and then computationally predicted the most potent combinations and optimal linkers. This process produced LY5 (35), a sulfonamide-containing small molecule which potently inhibited constitutive STAT3 phosphorylation in RH30 rhabdomyosarcoma cells at 500 nM, with no inhibition of STAT1 phosphorylation at 5 μM. In subsequent work, London and colleagues determined that LY5 potently blocked proliferation of several STAT3-dependent osteosarcoma and rhabdomyosarcoma cell lines in vitro, inhibiting phosphorylation of STAT3 but not other STAT family members.115 However, oral gavage of 20 mg/kg daily of LY5 failed to affect lung metastasis in mice (OS-17 osteosarcoma xenograft model). Interestingly, RNAi knockdown of STAT3 in LY5-responsive osteosarcoma cell lines did not reduce cell proliferation.115 Thus, while LY5 is a potent STAT3 inhibitor, it may be that its anti-proliferative mechanism was STAT3-independent in OS-17 cells. This example highlights the difficult balance of improving potency and selectivity of inhibitors while increasing bioavailability and avoiding off-target effects.

Several additional groups have used sulfonamides as part of fragment-based approaches targeting the STAT3 SH2 domain and PTP1B. Kong and colleagues used a fragment-based approach to identify LY-17, (36) an inhibitor with an IC50 value of 440 nM for inhibiting the STAT3 SH2 domain.116 This inhibitor blocked STAT3 phosphorylation in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells at 5 μM, and significantly reduced tumor growth in a mouse xenograft breast cancer model when delivered orally at 10 mg/kg. Though not tested clinically, LY-17 (36), whose predecessors include STA-21 (33), LLL12 (34), and LY5 (35), has proven to be one of the more promising STAT3 inhibitors, with oral biovailability, minimal STAT1/STAT5 inhibition, and excellent anti-tumor efficacy in mice. It will be interesting to see whether LY-17 or a similar analog will be evaluated clinically in the near future. Winssinger and colleagues, aiming to improve selectivity, generated a library of 125 different pTyr isosteres focused on salicylates and sulfonamides, and combined them with 500 different heterocycles to take advantage of a secondary specificity pocket.117 Screening this library produced inhibitors with KD values ranging from 50 to 290 nM for PTP1B, all incorporating an arylsulfonamide. Impressively, two of their top ten hits (one of these is shown as compound 37) had over 100-fold selectivity for PTP1B over TC-PTP. Another fragment-based approach by Du, Li and colleagues generated a diethoxyphenyl methanesulfonamide compound (38) that inhibited PTP1B with an IC50 of 203 nM, with greater than 120-fold selectivity over TC-PTP.118 These results highlight the power of fragment-based approaches to improve both potency and selectivity for sulfonamide-based PTP and SH2 domain inhibitors.

One of the most promising sulfonamides to date was discovered by Tweardy and colleagues, who screened a virtual library of 920,000 compounds to identify small molecule inhibitors of the STAT3 SH2 domain.119 The most potent hit from this screen, C188 (39), induced apoptosis at high doses in cell culture. In combination with docetaxel, intraperitoneal injection of C188 decreased tumor volume in xenograft breast cancer models.120 However, toxicity was also observed in non-STAT3-dependent cell lines, casting doubt on whether the mechanism was STAT3-dependent. More recently, computational screening was used to further improve C188, producing compound C188–9 (40) which had a KD of 4.7 nM for the STAT3 SH2 domain.121 Interestingly, C188–9 lacked both of the carboxylates of C188. C188–9 inhibited G-CSF-induced STAT3 phosphorylation in cultured cells, but it had no effect on normal murine bone marrow colony formation. In mouse xenograft models with UM-SCC-17B head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, tumor size was significantly reduced when treated with C188–9 (100 mg/kg/day) but not with C188 (50 mg/kg/day). Importantly, while C188 was relatively selective for STAT3 over STAT1, C1889 inhibited IFN- and G-CSF-induced STAT1 phosphorylation in Kasumi-1 leukemic cells (IC50 values of 9.5 and 4.1 μM, respectively). Tvardi Therapeutics, founded in 2017, was created to move C188–9, now renamed TTI-101, into clinical trials. It is currently in Phase I trials in patients with advanced cancers with solid tumors. Importantly, it remains to be seen how its unique STAT3/STAT1 selectivity profile will affect the efficacy and toxicity of TTI-101 in humans.

Sulfonates

Sulfonates are another class of pTyr isosteres that have reduced negative charge compared to phosphates and phosphonates (Fig. 6). For example, Taylor and colleagues prepared difluorosulfonomethyl phenylalanine (F2Smp) as a pTyr isostere, which is similar to difluorophosphonomethyl phenylalanine (F2Pmp) but with reduced charge (a sulfonate instead of a phosphonate).122 A peptide incorporating F2Smp inhibited PTP1B with an IC50 of 360 nM, over 100-fold less potent than the analogous F2Pmp-containing peptide. When F2Pmp and F2Smp were incorporated into small molecule inhibitors (41), they had more comparable (but much higher) IC50 values.122 This work suggested that difluorosulfonates might hold some promise as pTyr isosteres, but not as direct replacements for difluorophosphonates in peptide inhibitors.

Figure 6.

Sulfonamide inhibitors of PTP and SH2 domains, and related analogs.

Multiple groups have developed small molecule sulfonates to inhibit PTPs. Birchmeier and colleagues performed a high-throughput in silico screen of 2.7 million molecules docked in the SHP2 catalytic domain, and identified a phenylhydrazanopyrazolone sulfonate (PHPS1, 42) that inhibited SHP2 with an IC50 of 2.1 μM.123 PHPS1 was 15-fold selective for SHP2 over the structurally homologous SHP1 and 10-fold selective over PTP1B, but it was only 2-fold selective over the phosphatase ECPTP. In subsequent structure-guided design work to improve upon this inhibitor, authors observed that the addition of a single nitrate group was sufficient to improve SHP2 inhibition to an IC50 of 71 nM, with 29- and 45-fold selectivity over SHP1 and PTP1B, respectively.124 Wu, Lawrence and colleagues screened the NCI Diversity Set library of 1981 compounds, and identified two different hits as SHP2 inhibitors.125–127 The first inhibitor, NSC-87877, had two separate sulfonate moieties. This compound inhibited SHP2 activity with an IC50 of 318 nM, but was not selective for SHP2 over SHP1.125 A second sulfonate-containing hit, NSC-117199 (43), was much less potent, but it was later optimized into a sulfonamide- and benzoate-containing analog with an IC50 of 1 μM for SHP2 and 18-fold selectivity over SHP1.126 The optimized inhibitor replaced the sulfonate with a sulfonamide, and a carboxylate was added to engage positively charged residues in the active site.127 The carboxylate was esterified to promote cell penetration. While the unesterified analog had no impact on cell viability of a TF-1 leukemic cancer cell line with a constitutively activated SHP2E76K mutation, the esterified prodrug reduced cancer cell viability by 50% at 10 μM and by over 90% at 25 μM when incubated for 4 days.

A unique, sulfonate-containing pTyr isostere was identified by Zhang and colleagues from a screen of the Johns Hopkins Drug Library of FDA-approved compounds.71 They identified cefsulodin, a third generation β-lactam, as an inhibitor of SHP2 with an IC50 of 16.8 μM and very modest selectivity over SHP1. The authors then generated a library of 192 cefsulodin analogs of varying size, hydrophobicity, and charge, ultimately improving the IC50 for SHP2 inhibition to 1.5 μM with nearly 5-fold selectivity over SHP1. The optimized inhibitor, 44, potently suppressed growth of ErbB2-positive SKBR3 breast tumor cells in 3D Matrigel after one day at 10 μM. A crystal structure of an analog similar to 44 revealed that, when bound to SHP2, the terminal phenyl group and the sulfonate group together acted as a pTyr mimic (Fig. 3d). The sulfonate was shown to engage in multiple hydrogen bonds with the P-loop, including with the backbone amides of residues S460, A461, I463, G464, and R465, as well as water-mediated hydrogen bonding with side chains of R465 and K366. Additionally, the benzene ring interacted with the hydrophobic pocket typically responsible for stabilizing the pTyr tyrosine during catalysis. Thus, this benzyl sulfonate represented a uniquely oriented pTyr mimic. In separate work, Zhang and colleagues used a benzyl sulfonate to target the Mycobacterium tuberculosis phosphatase PtpB.128 Guided by docking, the authors identified a compound (45) with an impressive IC50 of 18 nM for PtpB. 45 inhibited none of the other 25 PTPs tested at concentrations up to 200 μM. This was a powerful demonstration that a simple benzyl sulfonate can be used as a pTyr isostere for some PTPs. It remains an open question whether this result is specific for the bacterial target PtpB, or if it can be incorporated into inhibitors of human PTPs and SH2 domains.

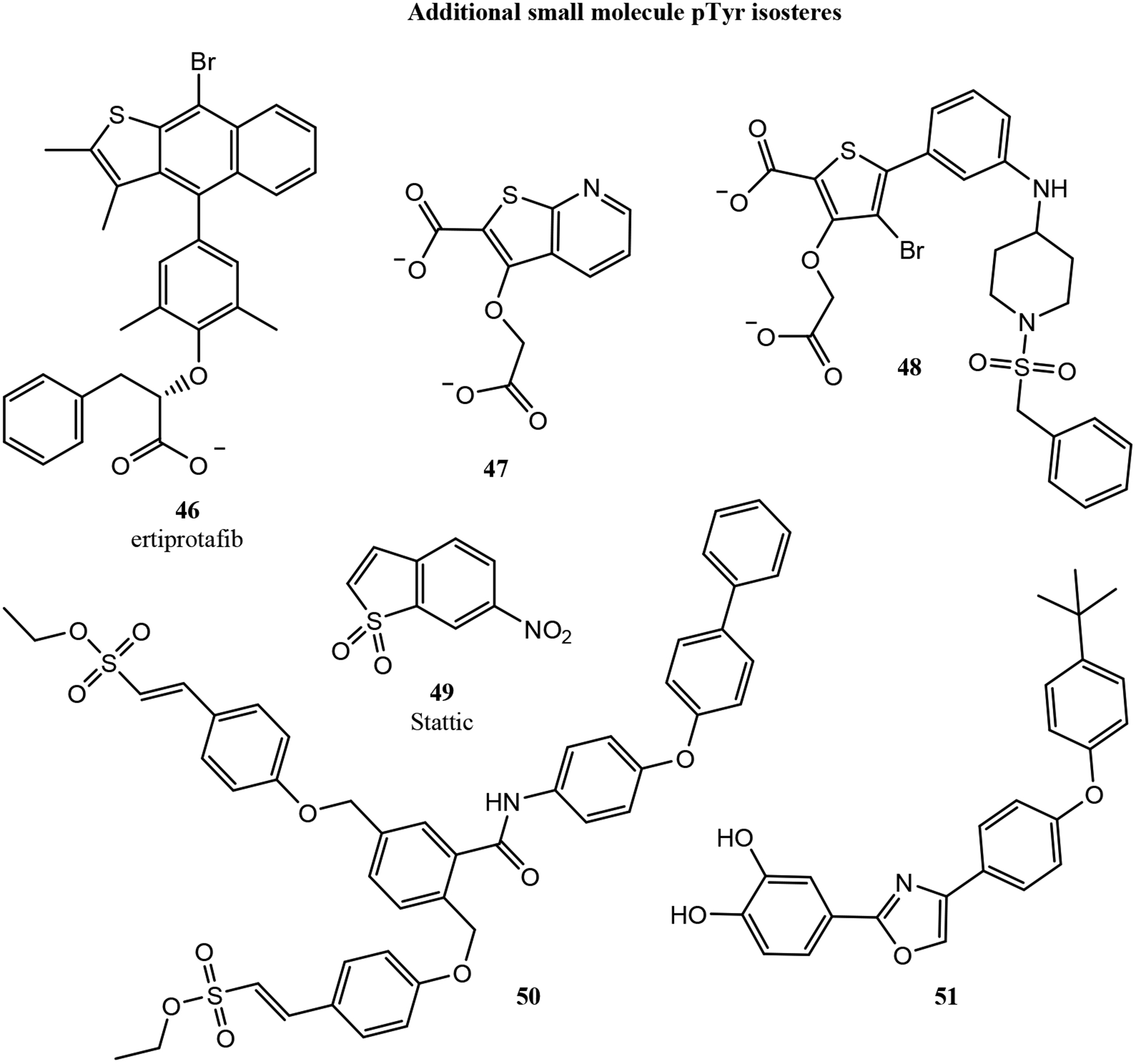

Additional Small Molecule Approaches

Several other classes of small molecules have been used as pTyr isosteres, notably the mono-, bi-, and tricyclic thiophenes (Fig. 7).72,129–132 For example, a phenoxyacetic acid-containing thiophene was identified by Wyeth Research as a PTP1B inhibitor.132 This molecule, ertiprotafib (46), became the first PTP1B inhibitor to be tested in clinical trials, but it was discontinued in Phase II as a result of poor efficacy and dose-limiting toxicities.133 It was later discovered that in addition to PTP1B inhibition, ertiprotafib acted as a PPARα/γ agonist and an IKK-β inhibitor.132,134 Lee and colleagues at Wyeth Research went on to identify an oxyacetic acid-containing pyridothiophene as a novel PTP1B inhibitor (47). Crystal structures of 47 and analogs showed the thiophene ring acted as a pTyr mimic within the PTP1B active site, with the WPD loop in the closed conformation (Fig. 3e).129,135 The thiophene ring participated in pi stacking with F182 and Y46, while the two thiophene carboxylates interacted with K120 and R221. Additionally, the thiophene ether oxygen engaged in water-mediated hydrogen bonds with the sidechains of A217 and R221. To improve potency, several bicyclic and tricyclic thiophene scaffolds were tested, and a benzylsulfonamide was incorporated to try to engage the secondary pTyr-binding pocket.72 One of their most potent compounds (48) had an IC50 of 4 nM. Crystal structures demonstrated that 48 successfully bound the secondary pTyr binding site (Fig. 3e), with sulfonyl oxygens engaged in water-mediated hydrogen bonds with R24 and R254 and the benzyl group engaged in hydrophobic interactions with F52. Unfortunately, while the potency of 48 was drastically improved, it was still not selective for PTP1B over TC-PTP. Despite these challenges, several compounds in this series were further studied as esterified prodrugs in obese mice. When dosed intraperitoneally twice daily at 50 mg/kg, one compound reduced glucose levels by 42% and insulin levels by 54% after 4 days of treatment.130 So, while these thiophenes were not selective for PTP1B, they did improve insulin sensitivity in vivo. Additionally, Berg and colleagues screened a small molecule library of 17,298 compounds and discovered a nitrate-containing benzothiophene, Stattic (49), capable of inhibiting the STAT3 SH2 domain.131 Stattic completely inhibited IL-6 induced STAT3 phosphorylation in MDA-MB-231 and MDA-MB-435S breast cancer cells at 20 μM. Further, Stattic induced apoptosis in these cells (10% and 20% respectively) at 10 μM, but not in STAT3-independent MDA-MB-453 cells.

Figure 7.

Sulfonate inhibitors of PTP and SH2 domains.

Building on previous experiences with sulfonamides, several groups have attempted to produce uncharged molecules as more cell-penetrant phosphatase inhibitors. For example, ethenesulfonic acid esters were studied for their potential as pTyr isosteres in 2012 by Jiang, Fu and colleagues.136 By linking the ethenesulfonic acid ester to a bromophenyl-substituted thiophene, they developed a PTP1B inhibitor with an IC50 of 1.3 μM and 10-fold selectivity for PTP1B over TC-PTP. In subsequent work, the authors developed a more potent bis-arylethenesulfonic acid ester (50) with an IC50 of 140 nM for PTP1B and 9- and 6-fold selectivity over TC-PTP and SHP2, respectively.137 This compound also demonstrated passive membrane permeability in a PAMPA assay, with a Papp of 9.7 × 10−6 cm/s. Shi and colleagues took a similar approach to develop a series of catechols as uncharged PTP1B inhibitors.138 Their most potent compound (51) inhibited PTP1B with an IC50 of 487 nM and was 27-fold selective for PTP1B over TC-PTP. Overall, while these classes of compounds have modest affinity and selectivity, they are notable for their lack of negative charge, which could allow them to be developed into more bioavailable PTP and SH2 domain inhibitors.

CONSTRAINED PEPTIDES THAT MIMIC PTYR USING DISCONTINUOUS EPITOPES

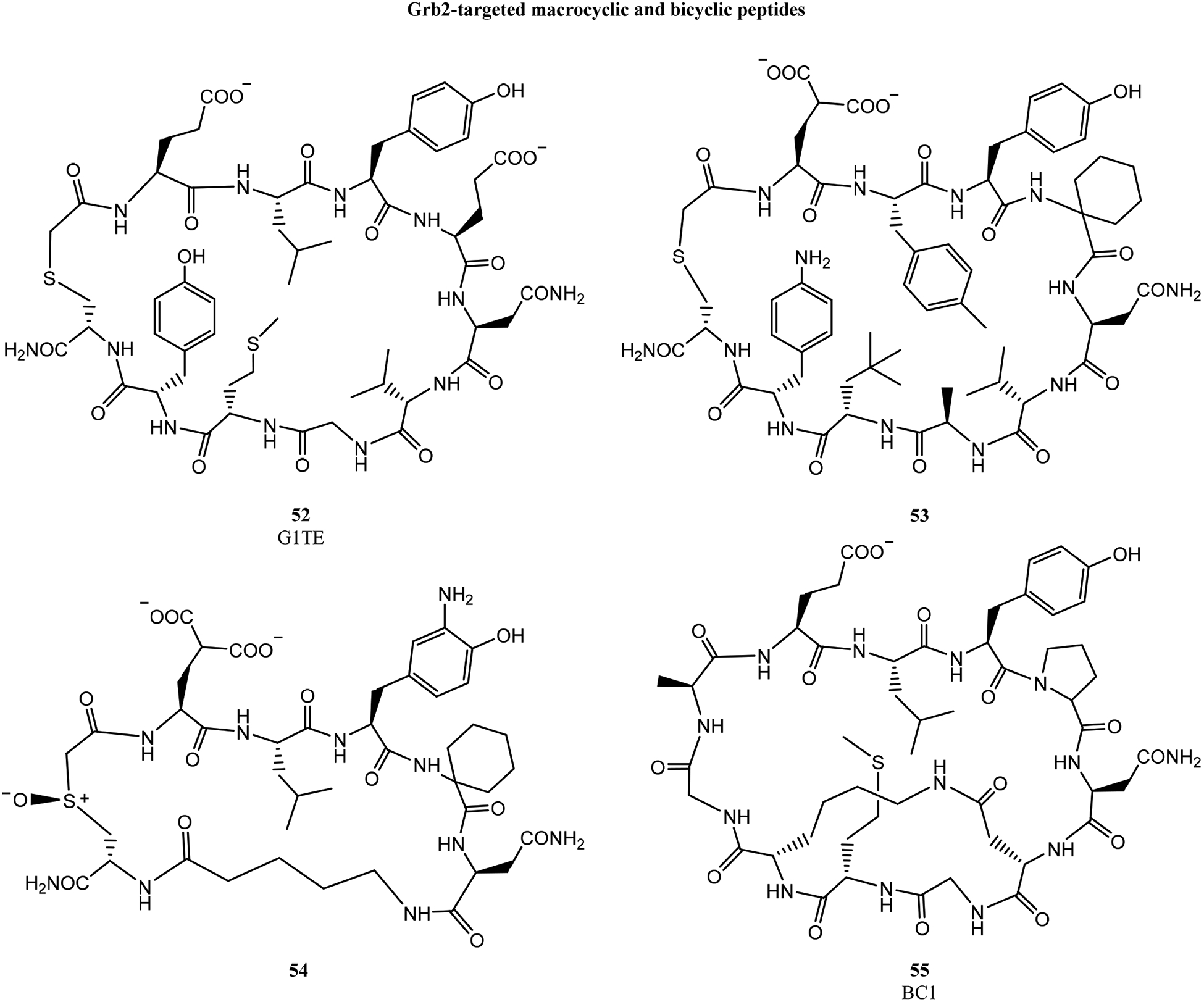

Grb2-Targeted Macrocyclic and Bicyclic Peptides

A handful of efforts have explored constrained peptides that mimic pTyr using discontinuous epitopes - binding surfaces that contain functional groups from non-adjacent residues. The first such inhibitor was discovered in 1997 by King, Roller and colleagues, who used phage display to discover a nonphosphorylated peptide inhibitor of the Grb2 SH2 domain.139 This peptide, called G1, bound the Grb2 SH2 domain with an IC50 of 26 μM as measured by competition SPR. G1 was a disulfide-cyclized peptide that contained a nonphosphorylated tyrosine, an asparagine located two residues C-terminal to the tyrosine (known to contribute to selectivity for Grb2), and a glutamate located two residues N-terminal to the tyrosine. Roller and colleagues subsequently produced a thioether-cyclized variant, G1TE (52, Fig. 8), and determined that the activity of G1TE was dependent on the relative positioning of the glutamate and the tyrosine.140 Inhibitory potency was improved by replacing the glutamate and tyrosine with artificial analogs.141 After several structure-activity relationship series, an optimized inhibitor was produced with an additional turn-inducing aminocyclohexanecarboxylic acid residue, rigidification of the macrocycle with D-alanine, and strengthening of intramolecular hydrophobic interactions with artificial amino acids.142 Combining all of these modifications resulted in their most potent cyclic peptide inhibitor (53), which inhibited the Grb2 SH2 domain with an IC50 of 17 nM.

Figure 8.

Thiophenes and additional small molecule pTyr isosteres shown to inhibit PTPs and SH2 domains.

Throughout the extensive structure-activity analysis of G1TE, one consistent feature was the importance of the overall conformation of the macrocycle. Non-macrocyclic analogs lost all affinity, and the conformation of residues distant from the functional groups that made up the pTyr-mimicking epitope had important and unpredictable effects on inhibitory potency.143,144 These and other observations guided Long, Roller and colleagues to design analogs that substituted several amino acids with ω-amino carboxylic acid linkers. Along with a carboxyglutamic acid pTyr isostere and a 3′-amino-substituted tyrosine, these modifications produced a more drug-like macrocycle with an IC50 of 190 nM for Grb2.144 In a particularly striking example of the importance of macrocycle conformation, the same authors identified that replacing the thioether with a sulfoxide improved G1TE affinity modestly for the (R)-sulfoxide, but led to a 4-fold loss in affinity for the (S)-sulfoxide. The authors used the (R)-sulfoxide within their minimized, most drug-like analog (54) to improve affinity to an IC50 of 58 nM.144

Building on Roller’s extensive work on G1TE analogs, Kritzer and colleagues replaced the thioether of G1TE with head-to-tail macrocyclization.145 Their optimal head-to-tail cyclic peptide had a 6 μM IC50 for Grb2 inhibition, compared to 20.5 μM for G1 and 20 μM for G1TE. To improve affinity through conformational constraint, they generated bicyclic peptides through side chain lactam stapling. This approach generated compound BC1 (55), which had an IC50 of 350 nM. BC1 was stable in human serum over 24 hours, demonstrated cellular uptake (but no antiproliferative activity) in MDA-MB-453 breast cancer cells, and bound two different anti-pTyr antibodies.145,146 This last result demonstrated that, with appropriate conformational constraints, a discontinuous epitope that used a carboxylate instead of a phosphate could effectively mimic pTyr.

Grb7-Targeted Macrocyclic and Bicyclic Peptides

Roller, Li, Krag and colleagues also identified a Grb7-binding, disulfide-linked macrocycle using phage display.147 Like G1TE, this peptide was developed into a thioether-cyclized macrocycle, G7–18NATE (Fig. 9, 56), which bound Grb7 with a KD of 13.2 μM and inhibited the Grb7/ErbB interaction in SKBR3 breast cancer cell extracts.147,148 Impressively, this peptide demonstrated no inhibition of Grb2 up to 100 μM despite the similarities of Grb2 and Grb7 binding preferences.

Figure 9.

Macrocyclic and bicyclic peptides that target Grb2 using discontinuous pTyr-mimicking epitopes.

G7–18NATE had multiple negative charges, which implied that this peptide would have poor cell uptake and cytosolic penetration. To address this challenge, Wilce and colleagues conjugated G7–18NATE to the cell-penetrating peptide penetratin.149 At 10 μM, the conjugate was taken up into MDA-MB-468 breast cancer cells after 30 minutes, where it strongly colocalized with cytoplasmic Grb7.

In subsequent work, Wilce and coworkers applied additional conformational constraints to G7–18NATE to improve its properties. Two O-allyl serines were incorporated within the cyclic peptide, then cross-linked using ring-closing metathesis to produce bicyclic peptide G7-B1.150 G7-B1 bound Grb7 with a KD of 1.94 μM as measured by ITC (in high phosphate buffer, which was found to enhance binding affinity). A co-crystal structure revealed that the hydrocarbon staple of G7-B1 unexpectedly contacted the Grb7 surface, providing a rationale for the enhanced binding affinity.151 The structural data was also used to minimize the bicyclic peptide, producing G7-B4 (57). G7-B4 bound Grb7 with a KD of 0.83 μM in high phosphate buffer, and G7-B4 had no detectable affinity for Grb2, Grb10, or Grb14. Attempting to better engage the Grb7 D497 residue positioned near the hydrocarbon staple, Wilce and coworkers made several additional bicyclic peptides using different stapling chemistries.73 Replacing the hydrocarbon linkage with a triazole resulted in a loss of binding affinity, but a lactam linkage improved the Grb7 affinity to 0.27 μM in high phosphate buffer, and 1.1 μM in physiologic conditions.

To further improve the affinity of G7-B4, Wilce and coworkers tested G7-B4 analogs with carboxymethyl phenylalanine (cmF) or carboxyphenylalanine (cF) in place of the key tyrosine. These bicyclic peptides had Grb7 binding affinities of 220 nM and 130 nM, respectively, in physiological conditions.73 The cF-containing bicyclic peptide (58), exhibiting higher affinity, did not reach as deep within the pTyr binding pocket compared to the cmF-peptide (Fig. 3f). Instead, the cF carboxylate formed hydrogen bonds with N463 and S460 side chains near the edge of the binding site. Finally, 58 was conjugated to penetratin and a nuclear localization sequence to promote cellular delivery. This conjugate appeared to penetrate into MDA-MB-231 cells, and at 20 μM it inhibited Grb7 interactions with its binding partners HER2, FAK, and SHC in SKBR3 cells.152

Currently, the cyclic and bicyclic peptide inhibitors of Grb2 and Grb7 do not represent compounds that are ready for clinical advancement. However, they have provided considerable insight into the degree to which conformation can play a role in affinity and selectivity. Both sets of constrained peptides used a discontinuous epitope, made up of two or more non-adjacent side chains, to mimic pTyr. Because this epitope was dependent on the 3D conformation of the macrocycle, changing single stereocenters or applying different cyclization strategies completely altered binding affinity. This was largely an advantage, though it did require extensive structure-activity relationships to develop these constrained peptides into sub-micromolar inhibitors. It remains to be seen whether the extreme selectivity observed for both sets of inhibitors is dictated by the discontinuous epitope, or whether it is particular to these specific targets.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Ongoing Clinical Trials

Very few small molecule or peptide-based inhibitors of SH2 domains or PTPs have entered clinical trials, and none to date have gained FDA approval. Among SH2 domain inhibitors, only a handful of molecules targeting the STAT3 SH2 domain have been tested in clinical trials. The STAT3 inhibitor STA-21 was tested in a phase I/II clinical trial as a topical treatment for psoriasis, where it improved skin lesions for six of the eight patients tested.113 However, since the phase I trial concluded in 2010, STA-21 has yet to be advanced to further trials. The sulfonamide TTI-101, developed by Tvardi Therapeutics, is currently in phase I trials for patients with advanced solid tumors (NCT03195699). Several small molecule STAT3 SH2 inhibitors (structures not yet disclosed) have been developed and tested clinically by Otsuka Pharmaceuticals. OPB-51602 was tested in multiple phase I clinical trials for different malignancies. When tested in patients with solid tumors, including non-small cell lung cancer, melanoma, and gastrointestinal stromal tumors, OPB-51602 was able to achieve a partial response in two patients, but there was poor overall tolerability of the drug.153 When tested in patients with hematological malignancies, dose-limiting toxicities including lactic acidosis and peripheral neuropathies prevented further clinical assessment.154 Additionally, a phase I trial in nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients was terminated due to lactic and metabolic acidosis (NCT02058017). Another STAT3 SH2 inhibitor, OPB-31121, was tested in several phase I trials. OPB-31121 was tolerated up to 800 mg/day in patients with advanced solid tumors, and one rectal cancer patient and one colon cancer patient saw tumor shrinkage over the duration of treatment.155 However, additional phase I trials in patients with solid tumors reported poorer tolerability, with dosing higher than 300 mg/day resulting in lactic acidosis.156 Additionally, a phase I/II trial in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma demonstrated insufficient efficacy as well as peripheral nervous system toxicities, and an additional trial in patients with hematological malignancies was terminated.157 One additional inhibitor still in trials by Otsuka is OPB-111077. In phase I trials, this drug was well-tolerated in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and advanced solid tumors.158,159 OPB-111077 is currently in multiple phase I trials in patients with hematological malignancies as a single agent and in combination with bendamustine and rituximab (NCT03197714, NCT04049825), as well as a phase II trial for patients with treatment-refractory solid tumors (NCT02250170). OPB-111077 is the most advanced SH2-domain-targeted small molecule drug currently in clinical trials, and the outcome of the phase II clinical trial will help clarify the potential of inhibiting the STAT3 SH2 domain to treat solid tumors.

With the limited success of small molecule approaches, other mechanisms for blocking STAT3 activity have been pursued.160–163 AstraZeneca’s AZD9150 is an antisense oligonucleotide therapy targeting STAT3. Results in several phase I and I/b trials in patients with treatment-refractory lymphomas and lung cancer have demonstrated good overall tolerability and early signs of efficacy.162,163 Multiple phase I/II and phase II trials are currently recruiting patients with triple negative breast cancer, non-small cell lung cancer, and several other advanced cancers. There are also several active and recruiting phase I/II and phase II clinical trials for BP1001 (Bio-Path Holdings, Inc.), an antisense oligonucleotide targeting Grb2, for the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia and other hematological malignancies. Initial results in patients with treatment-refractory leukemias suggested tolerability and early efficacy as a monotherapy or in combination with low-dose cytarabine.164 Independent from efforts to pharmacologically inhibit STAT3 and Grb2, these knock-down therapies will be a critical test to see if these proteins remain prominent targets for cancer drug development in the near future.

The only direct pTyr isostere to be tested in clinical trial against a phosphatase has been Wyeth Research’s PTP1B inhibitor, ertiprotafib, which had dose-limiting toxicities ascribed to poor specificity.133 However, other modalities for inhibiting PTP1B have been tested in clinical trials. The allosteric inhibitor trodusquemine (MSI-1436)165 by Genaera has been tested in several phase I trials in patients with obesity and type 2 diabetes. However, no additional clinical testing in these patient populations has been performed since 2009. Tonks and colleagues at Cold Spring Harbor, in collaboration with the PTP1B-focused pharmaceutical company, DepYmed, recently reported a trodusquemine analog with improved bioavailability, DPM-1001.166 It remains to be seen if allosteric inhibitors such as these will finally demonstrate the efficacy of PTP1B inhibition in obesity and diabetes in humans.

Ionis Pharmaceuticals developed an antisense oligonucleotide against PTP1B, and it demonstrated a lack of interaction with sulfonylureas and other commonly used diabetes medications.167 A subsequent analog, ISIS-PTP-1BRX, demonstrated only modest efficacy in a phase II clinical trial in patients with type 2 diabetes (a reduction in hemoglobin A1c of 0.7% and a slight reduction in body weight).168 Additional trials have not been conducted since 2015. Given the numerous therapies already available or in clinical trials for management of type 2 diabetes, there is likely a significantly higher bar required for PTP1B-targeted therapies in the future.

Recent data by a team at Novartis implicated SHP2 in the growth and metastasis of RTK-driven cancers,18 and this has spurred further interest in targeting SHP2 for solid tumors. Allosteric inhibitors TNO155 (Novartis) and RMC-4630 (Sanofi) have both recently entered phase I trials for advanced solid tumors, as single agents and as combination therapies (NCT03114319, NCT04000529, NCT03634982, NCT03989115). Additionally, another SHP2 inhibitor with an undisclosed mechanism of action, JAB-3068 (Jacobio Pharmaceuticals), is also in phase I trials for advanced and metastatic solid tumors (NCT03518554, NCT03565003). In contrast to much of the work described in this review, allosteric inhibitors such as TNO155 do not incorporate a pTyr isostere. Rather, they bind allosterically to stabilize the auto-inhibited conformation of the protein.18

Lessons Learned and Current Trajectory

Of the approaches to pTyr isosteres discussed in this review, so far only small molecule approaches have been effective enough to merit clinical studies. The first challenge for small molecule inhibitors of SH2 domains and PTPs was cytosolic penetration, because early pTyr isosteres such as phosphonates retained a large negative charge. This challenge was largely overcome by high-throughput screening, virtual screening, and fragment-based approaches that developed numerous small molecule inhibitors with low or no charge. A more durable challenge has been balancing potency and selectivity. Even with extensive structure-activity relationship campaigns focused on both affinity and selectivity, only a few pTyr isosteres (in particular, sulfonamides) have provided high affinity and enough selectivity for advancement to clinical trials (Table 1). Out of all of the pTyr isostere classes, sulfonamides appear to be the most clinically viable, as they have been some of the most high-affinity, uncharged inhibitors - these include LY-17 and TTI-101 (36 and 40, respectively). Still, the challenge of making these inhibitors selective when SH2 domains and PTP active sites are so structurally conserved remains the primary reason why so few molecules have made their way to clinical trials. While virtual screening and fragment-based approaches have helped considerably, these approaches have not yet completely solved the overarching limitation of selectivity.

Table 1.

Selected pTyr isosteres and other inhibitors currently in clinical trials or with notable pre-clinical efficacy.

| Target | Inhibitor | Class | Phase/Trial ID | Indications | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STAT3 | TTI-101 (C188–9) | Sulfonamide, direct inhibitor | Phase I (NCT03195699) | Advanced solid tumors | 121 |

| LY-17 | Sulfonamide, direct inhibitor | Pre-clinical study | 116 | ||

| OPB-111077 | Undisclosed, SH2 inhibitor | Phase I (NCT04049825) | Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma | 158, 159 | |

| Phase I (NCT03197714) | Acute myeloid leukemia | ||||

| Phase I (NCT03063944) | Acute myeloid leukemia | ||||

| Phase II (NCT02250170) | Refractory solid tumors | ||||

| AZD9150 (Danvatirsen, ISIS-STAT3rx) | STAT3 ASO | Phase l/ll (NCT03421353) | Advanced solid tumors | 162, 163 | |

| Phase II (NCT02983578) | Advanced pancreatic/NSCLC/colorectal cancer | ||||

| Phase l/ll (NCT02499328) | Advanced solid tumors/HNSCC | ||||

| Phase I (NCT02546661) | Bladder cancer | ||||

| Phase I (NCT03527147) | Refractory Non-Hodgkins Lymphoma | ||||

| Phase II (NCT03334617) | Non-small cell lung cancer | ||||

| Phase I (NCT03819465) | Non-small cell lung cancer | ||||

| Phase l/ll (NCT03742102) | Triple-negative breast cancer | ||||

| Grb2 | BP1001 | Grb2 ASO | Phase l/ll (NCT02923986) | Chronic myelogenous leukemia | 164 |

| Phase II (NCT02781883) | AML/Myelodysplastic syndrome | ||||

| Phase I (NCT01159028) | CML/AML/ALL/MDS | ||||

| PTP1B | DPM-1001 | Allosteric inhibitor | Pre-clinical study | 166 | |

| SHP2 | TNO155 | Allosteric inhibitor | Phase I (NCT03114319) | Advanced solid tumors | 18 |

| Phase Ib (NCT04000529) | Advanced solid tumors | ||||

| RMC-4630 | Allosteric inhibitor | Phase I (NCT03634982) | Refractory solid tumors | Unavailable | |

| Phase l/II (NCT03989115) | Refractory solid tumors | ||||

| JAB-3O68 | Undisclosed | Phase I (NCT03518554) | Advanced solid tumors | Unavailable | |

| Phase I(NCT03565003) | Advanced solid tumors |

Given the handful of targeted therapies still in clinical trials, the ultimate promise of targeting SH2 domains and PTPs using pTyr isosteres will soon be clearer. It is possible that direct SH2 domain inhibitors and PTP active site inhibitors cannot achieve the necessary balance of potency and selectivity; for efforts targeting the STAT3 SH2 domain, antitumor effects have been observed, but they are almost always accompanied by dose-limiting toxicities. Antisense oligonucleotide therapies are an independent means of examining these questions, especially with regards to efficacy. Certainly, if knockdown of STAT3 and/or Grb2 is shown to have beneficial effects in patients with solid tumors, this may support further efforts to inhibit these proteins pharmacologically. Additional treatment modalities such as antisense oligonucleotides and allosteric inhibitors may prove to be more selective than competitive inhibitors based on pTyr isosteres. This is reflected by the fact that therapeutics in these classes currently outnumber competitive inhibitors for these targets in active clinical trials (Table 1). The outcomes of these clinical trials will be pivotal for the future of cancer therapeutics targeting SH2-domain-containing proteins and PTPs.

It was clear from the start that there would never be a one-size-fits-all pTyr isostere for inhibition of SH2 domains and PTPs. However, the lessons learned in this field continue to inform medicinal chemistry and drug development. Many classes of phosphonates have progressed through clinical trials to FDA approval, such as the antiviral Tenofovir and the osteoclast bisphosphonate inhibitor Alendronate.169 The lessons learned from these shared chemistries have informed medicinal chemistry efforts across different target types, and continue to inform the development of SH2 domain and PTP inhibitors. Additionally, the ability to mimic pTyr through a discontinuous epitope on a constrained peptide scaffold, with exquisite selectivity for a single SH2 domain, highlights the versatility and potential of new approaches in peptide drug discovery.170

Inhibiting proteins such as PTP1B, Grb2 and STAT3 has been the focus of decades-long efforts. However, the increasing evidence implicating SHP2 as a critical factor supporting RTK-driven cancers highlights that new SH2-domain proteins and PTPs are emerging as important disease modulators. The lessons learned targeting PTP1B, Grb2, STAT3 and others have demonstrated that these targets are ultimately druggable. Further, the results described in this review represent best-odds strategies for producing pTyr mimetics to target emerging and future targets in this space. Future clinical studies may also investigate the benefit of combining pTyr isosteres with other forms of therapy like checkpoint inhibitors, in order to explore synergistic effects within these signaling pathways.

The history of the development of pTyr isosteres exemplifies the modern age of targeted therapeutics. As SH2 domain-containing proteins and PTPs continue to be implicated in human disease, the search for new strategies to inhibit them continues. This rich area of medicinal chemistry endures as a fruitful area for basic science and drug development, and it has paved the way for new modalities in molecular therapeutics.

Figure 4.

Oxalylamino acid-containing small molecule inhibitors of PTP and SH2 domains.

Figure 10.

Macrocyclic and bicyclic peptides that target Grb7 using discontinuous pTyr-mimicking epitopes.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Ruth L. Kirschstein Individual Predoctoral NRSA Fellowship F30CA220678 (NCI, NIH) and by NSF CHE-1507456.

Author Biographies

Robert Cerulli earned his BS in Chemistry from Tufts University in 2013. He is currently an MD/PhD candidate in the Medical Scientist Training Program at the Tufts University School of Medicine and Sackler School of Graduate Biomedical Sciences. His PhD work in the lab of Dr. Joshua Kritzer has focused on the design and discovery of peptide inhibitors of protein-protein interactions relevant for cancer cell signaling, in particular those involved in autophagy and JAK-STAT signaling.

Joshua A. Kritzer earned a BE in Chemical Engineering at The Cooper Union and a PhD in Biophysical Chemistry at Yale University. After NRSA-sponsored postdoctoral work in genetics at the Whitehead Institute, he started his own group at Tufts University in 2009. The Kritzer group uses peptides to solve vital chemical and biomedical problems.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

Works Cited

- 1.Sadowski I, Stone JC and Pawson T, Mol. Cell. Biol, 1986, 6, 4396–4408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koch CA, Anderson D, Moran MF, Ellis C and Pawson T, Science, 1991, 252, 668–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kraskouskaya D, Duodu E, Arpin CC and Gunning PT, Chem. Soc. Rev, 2013, 42, 3337–3370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pawson T and Nash P, Science, 2003, 300, 445–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Waksman G, Kominos D, Robertson SC, Pant N, Baltimore D, Birge RB, Cowburn D, Hanafusa H, Mayer BJ, Overduin M, Resh MD, Rios CB, Silverman L and Kuriyan J, Nature, 1992, 358, 646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Waksman G, Shoelson S, Pant N, Cowburn D and Kuriyan J, Cell, 1993, 72, 779–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou S, Shoelson SE, Chaudhuri M, Gish G, Pawson T, Haser WG, King F, Roberts T, Ratnofsky S, Lechleider RJ, Neel BG, Birge RB, Fajardo JE, Chou MM, Hanafusa H, Schaffhausen B and Cantley LC, Cell, 1993, 72, 767–778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guan K and Dixon J, J. Biol. Chem, 1991, 266, 17026–17030. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andersen JN, Mortensen OH, Peters GH, Drake PG, Iversen LF, Olsen OH, Jansen PG, Andersen HS, Tonks NK and Møller NPH, Mol. Cell. Biol, 2001, 21, 7117–7136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cho H, Krishnaraj R, Kitas E, Bannwarth W, Walsh CT and Anderson KS, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 1992, 114, 7296–7298. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jia Z, Barford D, Flint A and Tonks N, Science, 1995, 268, 1754–1758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peters GH, Frimurer TM, Andersen JN and Olsen OH, Biophys. J, 1999, 77, 505–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoff RH, Hengge AC, Wu L, Keng Y-F and Zhang Z-Y, Biochemistry, 2000, 39, 46–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cicirelli MF, Tonks NK, Diltz CD, Weiel JE, Fischer EH and Krebs EG, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci, 1990, 87, 5514–5518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elchebly M, Science, 1999, 283, 1544–1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klaman LD, Boss O, Peroni OD, Kim JK, Martino JL, Zabolotny JM, Moghal N, Lubkin M, Kim Y-B, Sharpe AH, Stricker-Krongrad A, Shulman GI, Neel BG and Kahn BB, Mol. Cell. Biol, 2000, 20, 5479–5489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chan G, Kalaitzidis D and Neel BG, Cancer Metastasis Rev, 2008, 27, 179–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen Y-NP, LaMarche MJ, Chan HM, Fekkes P, Garcia-Fortanet J, Acker MG, Antonakos B, Chen CH-T, Chen Z, Cooke VG, Dobson JR, Deng Z, Fei F, Firestone B, Fodor M, Fridrich C, Gao H, Grunenfelder D, Hao H-X, Jacob J, Ho S, Hsiao K, Kang ZB, Karki R, Kato M, Larrow J, La Bonte LR, Lenoir F, Liu G, Liu S, Majumdar D, Meyer MJ, Palermo M, Perez L, Pu M, Price E, Quinn C, Shakya S, Shultz MD, Slisz J, Venkatesan K, Wang P, Warmuth M, Williams S, Yang G, Yuan J, Zhang J-H, Zhu P, Ramsey T, Keen NJ, Sellers WR, Stams T and Fortin PD, Nature, 2016, 535, 148–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tartaglia M, Mehler EL, Goldberg R, Zampino G, Brunner HG, Kremer H, van der Burgt I, Crosby AH, Ion A, Jeffery S, Kalidas K, Patton MA, Kucherlapati RS and Gelb BD, Nat. Genet, 2001, 29, 465–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loh ML, Blood, 2004, 103, 2325–2331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buday L and Downward J, Cell, 1993, 73, 611–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Janes PW, Daly RJ, deFazio A and Sutherland RL, Oncogene, 1994, 9, 3601–3608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schlaepfer D, Hanks S, Hunter T and Vandergeer P, Nature, 1994, 372, 786–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheng AM, Saxton TM, Sakai R, Kulkarni S, Mbamalu G, Vogel W, Tortorice CG, Cardiff RD, Cross JC, Muller WJ and Pawson T, Cell, 1998, 95, 793–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giubellino A, Burke TR and Bottaro DP, Expert Opin. Ther. Targets, 2008, 12, 1021–1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stein D, Wu J, Fuqua SA, Roonprapunt C, Yajnik V, D’Eustachio P, Moskow JJ, Buchberg AM, Osborne CK and Margolis B, EMBO J, 1994, 13, 1331–1340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bivin WW, Yergiyev O, Bunker ML, Silverman JF and Krishnamurti U, Appl. Immunohistochem. Mol. Morphol, 2017, 25, 553–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lucas-Fernández E, García-Palmero I and Villalobo A, Curr. Genomics, 2008, 9, 60–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Han DC and Guan J-L, J. Biol. Chem, 1999, 274, 24425–24430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chu P-Y, Huang L-Y, Hsu C-H, Liang C-C, Guan J-L, Hung T-H and Shen T-L, J. Biol. Chem, 2009, 284, 20215–20226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shen T-L and Guan J-L, FEBS Lett, 2001, 499, 176–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Han DC, Shen TL and Guan JL, Oncogene, 2001, 20, 6315–6321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dsouza B and Taylorpapadimitriou J, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A, 1994, 91, 7202–7206.7913748 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnson DE, O’Keefe RA and Grandis JR, Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol, 2018, 15, 234–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yu H, Lee H, Herrmann A, Buettner R and Jove R, Nat. Rev. Cancer, 2014, 14, 736–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wei D, Le X, Zheng L, Wang L, Frey JA, Gao AC, Peng Z, Huang S, Xiong HQ, Abbruzzese JL and Xie K, Oncogene, 2003, 22, 319–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xie T, Wei D, Liu M, Gao AC, Ali-Osman F, Sawaya R and Huang S, Oncogene, 2004, 23, 3550–3560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gritsko T, Clin. Cancer Res, 2006, 12, 11–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee T-L, Yeh J, Waes CV and Chen Z, Cancer Res, 2004, 64, 1115–1115. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schlessinger K and Levy DE, Cancer Res, 2005, 65, 5828–5834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bu LL, Yu GT, Wu L, Mao L, Deng WW, Liu JF, Kulkarni AB, Zhang WF, Zhang L and Sun ZJ, J. Dent. Res, 2017, 96, 1027–1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Domchek SM, Auger KR, Chatterjee S, Burke TR and Shoelson SE, Biochemistry, 1992, 31, 9865–9870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vivanco I and Sawyers CL, Nat. Rev. Cancer, 2002, 2, 489–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Burke TR, Smyth MS, Nomizu M, Otaka A and Roller PR, J. Org. Chem, 1993, 58, 1336–1340. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Burke R, Kole HK and Roller PP, Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun, 1994, 204, 129–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Burke TR Jr., Smyth MS, Otaka A, Nomizu M, Roller PP, Wolf G, Case R and Shoelson SE, Biochemistry, 1994, 33, 6490–6494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shen K, Keng Y-F, Wu L, Guo X-L, Lawrence DS and Zhang Z-Y, J. Biol. Chem, 2001, 276, 47311–47319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Patel D, Jain M, Shah SR, Bahekar R, Jadav P, Joharapurkar A, Dhanesha N, Shaikh M, Sairam KVVM and Kapadnis P, Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett, 2012, 22, 1111–1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dufresne C, Roy P, Wang Z, Asante-Appiah E, Cromlish W, Boie Y, Forghani F, Desmarais S, Wang Q, Skorey K, Waddleton D, Ramachandran C, Kennedy BP, Xu L, Gordon R, Chan CC and Leblanc Y, Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett, 2004, 14, 1039–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li X, Bhandari A, Holmes CP and Szardenings AK, Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett, 2004, 14, 4301–4306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu W-Q, Roques BP and Garbay C, Tetrahedron Lett, 1997, 38, 1389–1392. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Furet P, Caravatti G, Denholm AA, Faessler A, Fretz H, García-Echeverría C, Gay B, Irving E, Press NJ, Rahuel J, Schoepfer J and Walker CV, Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett, 2000, 10, 2337–2341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Walker CV, Caravatti G, Denholm AA, Egerton J, Faessler A, Furet P, García-cheverría C, Gay B, Irving E, Jones K, Lambert A, Press NJ and Woods J, Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett, 2000, 10, 2343–2346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mandal PK, Liao WS-L and McMurray JS, Org. Lett, 2009, 11, 3394–3397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mandal PK, Gao F, Lu Z, Ren Z, Ramesh R, Birtwistle JS, Kaluarachchi KK, Chen X, Bast RC, Liao WS and McMurray JS, J. Med. Chem, 2011, 54, 3549–3563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]