Abstract

COVID-19 is caused by the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 and currently has detrimental human health, community and economic impacts around the world. It is unclear why some SARS-CoV-2-positive individuals remain asymptomatic, while others develop severe symptoms. Baseline pulmonary levels of anti-viral leukocytes, already residing in the lung prior to infection, may orchestrate an effective early immune response and prevent severe symptoms. Using “in silico flow cytometry”, we deconvoluted the levels of all seven types of anti-viral leukocytes in 1,927 human lung tissues. Baseline levels of CD8+ T cells, resting NK cells and activated NK cells, as well as cytokines that recruit these, are significantly lower in lung tissues with high expression of the SARS-CoV-2 entry receptor ACE2. We observe this in univariate analyses, in multivariate analyses, and in two independent datasets. Relevantly, ACE2 mRNA and protein levels very strongly correlate in human cells and tissues. Above findings also largely apply to the SARS-CoV-2 entry protease TMPRSS2. Both SARS-CoV-2-infected lung cells and COVID-19 lung tissues show upregulation of CD8+ T cell-and NK cell-recruiting cytokines. Moreover, tissue-resident CD8+ T cells and inflammatory NK cells are significantly more abundant in bronchoalveolar lavages from mildly affected COVID-19 patients, compared to severe cases. This suggests that these lymphocytes are important for preventing severe symptoms. Elevated ACE2 expression increases sensitivity to coronavirus infection. Thus, our results suggest that some individuals may be exceedingly susceptible to develop severe COVID-19 due to concomitant high pre-existing ACE2 and TMPRSS expression and low baseline cytotoxic lymphocyte levels in the lung.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, ACE2, TMPRSS2, T cells, NK cells

Introduction

Coronaviruses are viruses belonging to the family of Coronaviridae (1). They are large, single-stranded RNA viruses that often originate from bats and commonly infect mammals. While the majority of coronavirus infections cause mild symptoms, some can cause severe symptoms, such as pneumonia, respiratory failure and sepsis, which may lead to death (2, 3).

Coronavirus zoonosis constitutes a serious health risk for humans. Indeed, in recent history, transmissions of three types of coronaviruses to humans have led to varying numbers of deaths. The outbreak of the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) epidemic, which is caused by the SARS coronavirus (SARS-CoV), originated in Guangdong, China in 2002 and led to nearly 800 deaths (4). The Middle East Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) outbreak, which emerged in Saudi Arabia in 2012, similarly caused about 800 deaths, although with over 8,000 cases, nearly four times as many cases were reported (4). Finally, Coronavirus Disease 19 (COVID-19), caused by Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), is currently causing a pandemic. On 1 May 2020, the World Health Organization reported over 3 million confirmed cases and over 220,000 patients to have succumbed to COVID-19 around the world (5). However, the factual number of deaths is probably considerably higher (6). In addition, this figure is still soaring, on 1 May 2020 at a rate exceeding 6,400 deaths per day (5).

To infect target cells, coronaviruses use their spike (S) glycoprotein to bind to receptor molecules on the host cell membrane. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) has been identified as the main SARS-CoV-2 entry receptor on human cells (7, 8), while the serine protease TMPRSS2, or potentially cathepsin B and L, are used for S-protein priming to facilitate host cell entry (7). SARS-CoV-2 S-protein has a 10 to 20-fold higher affinity to human ACE2 than SARS-CoV S-protein (9). Moreover, ACE2 expression proportionally increases the susceptibility to S protein-mediated coronavirus infection (10–12). Hence, increased expression of ACE2 is thought to increase susceptibility to COVID-19 (13–15).

Epithelial cells of the respiratory tract, including the lung, are primary SARS-CoV-2 target cells (16–18). These cells can sense viral infection via pattern recognition receptors (PRRs). PRRs, including Toll-like receptors and NOD-like receptors, recognize pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) (19). Upon PRR activation, a range of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines are produced and released in order to activate the host’s immune system. Interferons (IFNs), in particular type I and type III IFN, are among the principal cytokines to recruit immune cells (19, 20).

Six types of leukocytes have been implicated in detecting and responding to viral infections in the lung, a major site of SARS-CoV-2 infection, which also presents with severe COVID-19 symptoms. The cytotoxic activities of CD8+ T cells and NK cells can facilitate early control of viral infections by clearing infected cells and avoiding additional viral dissemination (21, 22). Dendritic cells specialize in sensing infections, including by viruses, and inducing an immune response (23). CD4+ T cells contribute to viral clearance by promoting production of cytokines and interactions between CD8+ T cells and dendritic cells (24). M1 macrophages interact with pulmonary epithelial cells to fight viral infections in the lung (25). Finally, neutrophils may contribute to clearance of viral infections through phagocytosis of virions and viral particles. However, their precise role is uncertain (26).

SARS-CoV-2 is considerably more efficient in infection, replication and production of infectious virus particles in human lung tissue than SARS-CoV (17). Strikingly, despite this, SARS-CoV-2 initially does not significantly induce type I, II or III IFNs in infected human lung cells and tissue (17, 27). When this does occur, it may in fact promote further SARS-CoV-2 infection, as IFNs directly upregulate expression of the SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE2 (28). These observations suggest that baseline levels of leukocytes, which already reside in the lung prior to infection, may be important in mounting a rapid immune response against SARS-CoV-2 infection and prevent severe COVID-19 symptoms. As stated above, ACE2 expression level may be a predictor of increased susceptibility to COVID-19 (10–15)}. Thus, we here investigated the relationship between ACE2 and TMPRSS2 expression and the levels of seven leukocyte types implicated in anti-viral immune response in human lung tissue.

Results

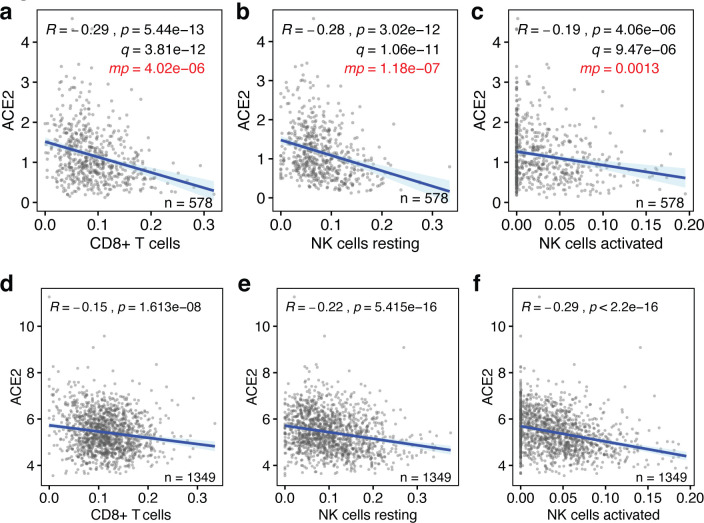

We used bulk RNAseq gene expression data from the 578 human lung tissues present in the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) database (29, 30), because this is the largest publicly available dataset with clinical information. Using an established “in silico flow cytometry” pipeline (31), we estimated the levels of CD8+ T cells, resting and activated NK cells, M1 macrophages, dendritic cells, CD4+ T cells and neutrophils in these tissues (Fig. S1a–c, Table S1). We compared these to ACE2 expression levels in these lung tissues. This revealed that ACE2 expression is negatively correlated with the levels of CD8+ T cells, resting and activated NK cells and M1 macrophages (p < 8×10−6, Pearson correlations) (Fig. 1a–c). However, there are no statistically significant correlations between ACE2 expression and the levels of CD4+ T cells, dendritic cells and neutrophils (p > 0.05) (Fig. S2a–d). Thus, the levels of a majority of leukocytes involved in anti-viral immune responses are significantly lower in lung tissues with high ACE2 expression levels.

Figure 1. Baseline levels of cytotoxic lymphocytes inversely correlate with ACE2 expression in the lung.

(a-c) The correlations between the baseline levels of CD8+ T cells, resting NK cells and activated NK cells (x-axes) and the those of the SARS-CoV-2 host cell receptor ACE2 (y-axes) in human lung tissue are shown. Data are from the GTEx dataset (n=578). (d-f) The same correlations are shown for lung tissues in the LUG dataset (n=1,349). Regression lines and 95% confidence intervals are shown. R and p values: Pearson correlations; q values: Benjamini-Hochberg-adjusted p values using a false discovery rate of 0.05; mp values: multivariate p values (see Table S3).

It is possible that some of above observations are linked to phenotypic characteristics, such as sex, age, body mass index (BMI), race or smoking status. To test the robustness of our findings, we applied multivariable regression analysis that includes these five covariates (Table S2), as well as the levels of the seven above leukocyte types or states. This showed that only 4 of the 12 variables significantly contribute to predicting ACE2 expression levels, specifically the levels of CD8+ T cells, resting NK cells, activated NK cells and M1 macrophages (Fig. 1a–c, Table S3). Notably, none of the five added phenotypic covariates showed statistically significant contributions. Consistently, we found limited statistically significant correlations between these variables and ACE2 expression in univariate analyses, irrespective of whether they were analyzed as continuous data or binned into discrete ordinal categories (Fig. S4a–j). Thus, the levels of four types of leukocytes that respond to viral infection are low in lung tissue with high ACE2 expression levels independently of phenotypic covariates.

Next, we tested whether above observations could be validated in an independent cohort of individuals. For this, we used the, to our knowledge, largest publicly available lung tissue dataset. The Laval University, University of British-Columbia, Groningen University (LUG) dataset includes microarray gene expression data of 1,349 human lung tissues. Following determination of ACE2 expression levels and estimation of the levels of CD8+ T cells, resting NK cells, activated NK cells and M1 macrophages (Fig. S1a–c, Table S1), we found that three of the four also negatively correlated with ACE2 expression in this independent dataset (p<2×10−8) (Fig. 1d–f). With a correlation coefficient of R=0.096, only M1 macrophages did not correlate with ACE2 expression in this dataset (Fig. S3). Thus, our observations indicate that the baseline levels of three types of cytotoxic lymphocytes, specifically CD8+ T cells, resting NK cells and activated NK cells, are robustly and consistently low in lung tissue with high expression of the SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE2.

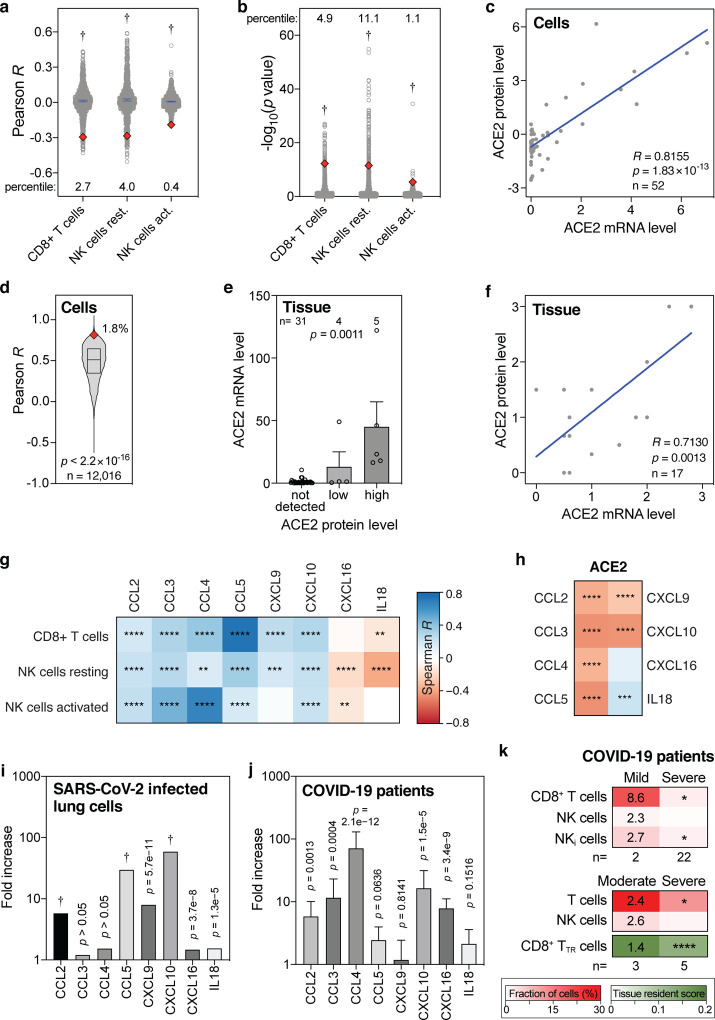

To more rigorously assess our observations, we employed a range of additional analyses. Although highly statistically significant (all p values <4.1×10−6, Fig. 1), the absolute Pearson R values between baseline levels of ACE2 and the three lymphocyte types were seemingly low, as they ranged between 0.2 and 0.3 (Fig 1a–c). To test how strong these are in relative terms, we calculated the Pearson R and p values of 1000 randomly sampled other genes. This revealed that the ACE2 R and p values were significantly lower than expected by chance (all one-sample t test p<2.2×10−16; Fig 2a,b). In addition, these R and p values ranked in the top 0.4 to 11 percentiles of strongest and most significant correlations for each of the three leukocyte types (Fig 2a,b). Thus, the seemingly low correlations between ACE2 mRNA and cytotoxic lymphocyte levels in the lung are not only highly statistically significant, but also strong in relative terms.

Figure 2. Levels of ACE2 mRNA, ACE2 protein, CD8+ T cells, NK cells and cytokines in lung cells, lung tissues and COVID-19 patient samples.

(a, b) Pearson R and −log10(p values) of correlations between 1000 randomly sampled genes and the levels of indicated lymphocytes in lung tissues were determined and plotted. ACE2 Pearson R and p values are shown as red diamonds. Blue lines indicate means with 95% confidence intervals. Percentiles for ACE2 with respect to the 1000 random R and p values are shown. Data are from the GTEx dataset (n=578). P values: one-sample t tests. (c) Correlations between ACE2 mRNA and protein levels in 52 cell lines. R and p values: Pearson correlations. (d) Pearson correlation R values between mRNA and protein levels of 12,016 genes are compared to the ACE2 R coefficient (red diamond). The box represents the median and interquartile range. The ACE2 R percentile is also shown. P value: one-sample t test. (e) Bar graph showing the correlation between ACE2 mRNA and protein levels in human tissues. Means with standard errors of the means are shown. Samples are from the Human Protein Atlas. P value: Kruskal-Wallis test. (f) Meta-analysis scatter plot showing the correlation between ACE2 mRNA and protein levels in 17 human tissues. Data are from 9 different studies, as detailed in Table S4. P value: Pearson correlation. (g, h) Heatmaps showing Spearman correlations between the levels of ACE2 or indicated cytotoxic lymphocytes and eight cytokines that recruit these cells in human lung tissues from the GTEx dataset (n=578). Colors of tiles represent Spearman R, as per scale bar on the right. Spearman significance levels are shown by asterisks. See also Fig. S5. (i, j) Fold increase in expression levels of indicated cytokines in Calu-3 lung cells 24 hours after SARS-CoV-2 infection compared to uninfected Calu-3 cells (i), and in post-mortem COVID-19 lung tissues (n=2) to those in healthy, uninfected lung tissues (n=2) (j). (k) Comparison of indicated fractions of lymphocyte levels in bronchoalveolar lavages of mild/moderate and severe COVID-19 patients, as determined in two separate studies (46, 47). The second also determined a tissue resident (TR) score for CD8+ T cells. Numbers in the mild/moderate column on the left show fold increase compared to the respective severe cases on the right. Asterisks in the severe column on the right represent statistical significance levels, as determined my Mann-Whitney U tests (top panel), or t tests (middle and bottom panels) comparing mild/moderate to severe cases. P value abbreviations: *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01; ***, p<0.001; ****, p<0.0001; †, p<2.2×10−16.

Further, we tested how well ACE2 mRNA and protein levels correlate. Using the mRNA and protein levels in 52 cell lines, we find that ACE2 mRNA levels strongly correlate with ACE2 protein levels in human cells (Pearson R=0.8155, p=1.8×10−13; Fig. 2c). In fact, ACE2 ranks in the top 1.8 percentile of over 12,000 genes with the strongest mRNA-protein level correlations (p<2.2×10−16; Fig 2d). Using two ACE2-specific antibodies, immunochemistry on 40 human tissues also shows a strong ACE2 mRNA-protein correlation (p=0.0011, Kruskal-Wallis test; Fig. 2e) and this is additionally validated by a meta-analysis that we conducted using nine published studies (Pearson R=0.7130, p=0.0013; Fig. 2f, Table S4). Therefore, we conclude that ACE2 mRNA and protein levels very strongly correlate, both in human cells and in human tissues.

Above, we found that baseline ACE2 levels in the lung negatively correlate with CD8+ T cells and resting and activated NK cells in multivariate analyses and in an independent dataset (Fig. 1a–f). Several cytokines, including CCL2–5, CXCL9, CXCL10, CXCL16 and IL18, are known to chemotactically attract CD8+ T cells and NK cells (32–37). Consistently, we find that the baseline levels of these chemokines in human lung tissue typically significantly correlate with the baseline levels of CD8+ T cells and resting and activated NK cells (Fig. 2g, Fig. S5). Additionally, as expected given our above results, we find significant negative correlations between the levels of ACE2 and the levels of six of these eight cytokines in the lung (Fig. 2h). These findings lend further support to our previous observations, suggesting that high levels of said cytokines in the lung establish a favorable milieu for cytotoxic lymphocytes, which correlates with low ACE2 levels.

Next, we assessed the direct consequences of SARS-CoV-2 infection. In vitro SARS-CoV-2 infection of human lung cells invariably leads to upregulation of all eight abovementioned CD8+ T cell-and NK cell-attracting cytokines, with six of these increases showing statistical significance (Fig. 2i). Similarly, compared to control lung tissues, all eight cytokines are upregulated in lung tissues from COVID-19 patients, with five showing statistical significance (Fig. 2j). Moreover, the levels of CD8+ T cells and NK cells are higher in bronchoalveolar lavages of mildly affected COVID-19 patients than in severe cases, with CD8+ T cells and a subset of NK cells, inflammatory NK cells, showing a statistically significant higher level (Fig. 2k). These findings are corroborated in a different cohort of patients, additionally showing a highly significant increase in a tissue-resident signature score for CD8+ T cells (Fig. 2k). Thus, together, these observations suggest that SARS-CoV-2 infection of lung cells stimulates CD8+ T cell-and NK cell-attracting cytokines and that these cytotoxic lymphocytes are important for preventing severe symptoms of COVID-19.

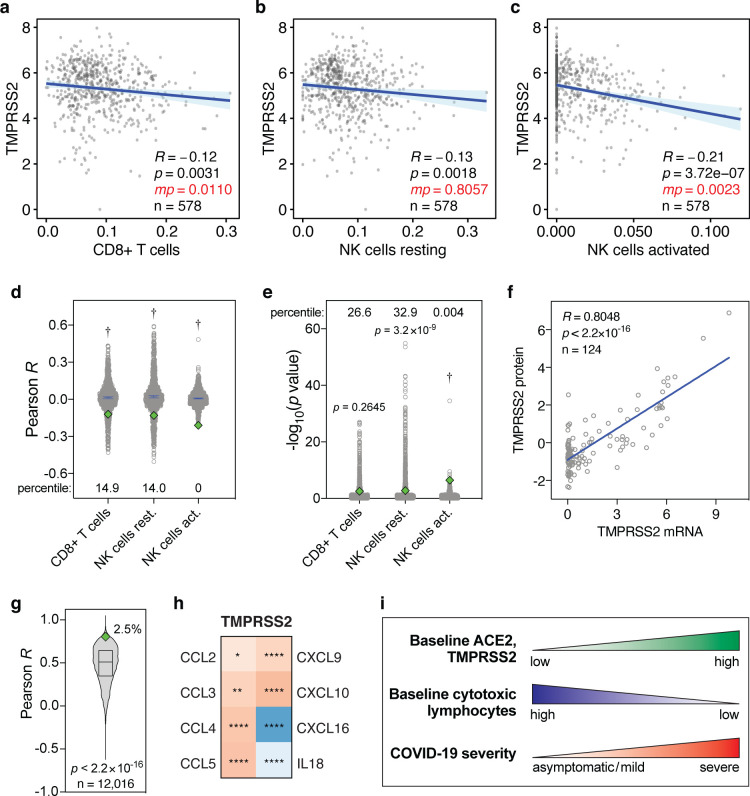

Finally, we tested whether the levels of the SARS-CoV-2 host cell protease TMPRSS2 shows similar correlations with the levels of CD8+ T cells and NK cells in the lung. In univariate analyses, baseline TMPRSS2 levels in the lung show significant negative correlations with these lymphocyte levels, although in multivariate analyses, these are only statistically significant for CD8+ T cells and activated NK cells (Fig. 3a–c). The corresponding R and p values are typically also significantly lower than expected by chance (Fig. 3d,e). Furthermore, TMPRSS2 mRNA and protein levels strongly correlate (R=0.8048, p<2.2×10−16, Fig. 3f) and TMPRSS2 is in the top 2.5 percentile of genes that show the strongest mRNA-protein correlation (p<2.2×10−16, Fig. 3g). Additionally, TMPRSS2 expression tends to correlate negatively with CD8+ T cell- and NK cell-attracting cytokines (Fig. 3h). Therefore, albeit typically to a lesser extent, baseline TMPRSS2 expression levels in the lung negatively correlate with the levels of CD8+ T cells and NK cells in a manner similar to ACE2.

Figure 3. Levels of TMPRSS2 mRNA, TMPRSS2 protein and cytokines in lung cells and tissues.

(a-c) Pearson correlations between baseline levels of indicated lymphocytes and TMPRSS2 in human lung tissue, as Figure 1a–c. Data are from the GTEx dataset (n=578). (d, e) Pearson R and −log10(p values) of correlations between 1000 randomly sampled genes and the levels of indicated lymphocytes in lung tissues, as in Figure 2a,b. TMPRSS2 Pearson R and p values are shown as green diamonds. (f) Correlations between TMPRSS2 mRNA and protein levels in 124 cell lines. R and p values: Pearson correlations. (g) Pearson correlation R values between mRNA and protein levels of 12,016 genes are compared to the TMPRSS2 R coefficient (green diamond). The box represents the median and interquartile range. The TMPRSS2 R percentile is also shown. P value: one-sample t test. (h) Heatmap showing Spearman correlations between the levels of TMPRSS2 and cytokines in human lung tissues from the GTEx dataset (n=578), as in Figure 2h. (i) Individuals with high baseline levels of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 show low baseline tissue-resident levels of cytotoxic lymphocytes in the lung. We propose that this may jointly predispose these individuals to development of severe COVID-19.

Taken together, our observations suggest that a subgroup of individuals may be exceedingly susceptible to developing severe COVID-19 due to concomitant high pre-existing ACE2 and TMPRSS2 expression and low baseline levels of CD8+ T cells and NK cells in the lung (Fig. 3i).

Discussion

We investigated the baseline expression levels of the SARS-CoV-2 host cell entry receptor ACE2 and the host cell entry protease TMPRSS2 and the baseline levels of all seven types of anti-viral leukocytes in 1,927 human lung tissue samples. Although SARS-CoV-2 cellular tropism is broad (16–18), we focused on lung tissue. In addition to epithelial cells elsewhere in the respiratory tract, alveolar epithelial cells are thought to be a primary SARS-CoV-2 entry point (16, 28). Consistently, the SARSCoV-2 receptor ACE2 is expressed in these cells at the mRNA and protein levels (28, 38–40). Moreover, in severely affected COVID-19 patients, the lungs are among the few organs that present with the most life-threatening symptoms. “Cytokine storm”-induced acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), widespread alveolar damage, pneumonia, and progressive respiratory failure have been observed (41, 42). These indications frequently require admission to intensive care units (ICUs) and mechanical ventilation and may ultimately be fatal.

Early after infection, rapid activation of the innate immune system is of paramount importance for the clearance of virus infections. Infected cells typically do so through release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, in particular type I and III interferons (19, 20). Notably, however, several studies have highlighted multiple complexities related specifically to SARS-CoV2 and innate immune system activation at early stages. First, unlike SARS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2-infected lung tissue initially fails to induce a range of immune cell-recruiting molecules, including several interferons (17, 27), suggesting that leukocytes are ineffectively recruited to infected lung shortly after infection. Second, the host cell entry receptor ACE2 has been identified as an interferon target gene (28). Thus, even when interferons are upregulated in order to recruit immune cells, concomitant upregulation of ACE2 expression may in fact exacerbate SARS-CoV-2 infection (28).

These findings suggest that the levels of immune cells that already reside in the lung prior to infection are more critical for dampening SARS-CoV-2 infection at early stages than they are for fighting infections of other viruses. Cytotoxic lymphocytes, including CD8+ T cells and NK cells, are key early responders to virus infections and these are the cells whose baseline levels we here identify as significantly reduced in lung tissue with elevated ACE2 and TMPRSS2 expression. That these immune cells are important in preventing severe COVID-19 is supported by the fact that their levels are significantly higher in bronchoalveolar lavages from mild patients than from severe patients. Therefore, our results suggest that individuals with increased baseline susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infection in the lungs may also be less well equipped from the outset to mount a rapid anti-viral cellular immune response (Fig. 3i).

Several observations indicate that these cytotoxic lymphocytes are critically important for effective control of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Recent studies showed that CD8+ T cells in peripheral blood are considerably reduced and functionally exhausted in COVID-19 patients, in particular in elderly patients and in severely affected patients that require ICU admission (43–45). Reduced CD8+ T cell counts also predict poor COVID-19 patient survival (43). Additionally, CD8+ T cell-and NK cell-attracting cytokines are upregulated in SARS-CoV-2-infected human lung cells and in lung tissues from COVID-19 patients and the levels of CD8+ T cells and NK cells are higher in bronchoalveolar lavages of mildly affected COVID-19 patients than in severe cases (46, 47).

We found that the five phenotypic parameters, sex, age, BMI, race and smoking history did not statistically significantly contribute to variation in ACE2 expression in human lung tissue, neither in univariate nor in multivariate analyses. This is consistent with some studies but inconsistent with others (42, 48–50). These paradoxical observations may be partially explained by varying gender, age and race distributions within each study cohort.

Further research will be required to elucidate the precise mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2-induced activation of the innate immune system early after infection. However, the link that we identified between high baseline ACE2 and TMPRSS2 expression and reduced cytotoxic lymphocyte levels in human lung tissue prior SARS-CoV-2 infection is striking. It suggests that increased susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infection in the lungs may be accompanied by a poorer ability to mount a rapid innate immune response at early stages. This may predict long-term outcome of individuals infected with COVID-19, given that the levels of CD8+ T cell and NK cell are significantly higher in bronchoalveolar lavages of mild cases compared to severe patients (46, 47). Finally, it may contribute to the substantial variation in COVID-19 clinical presentation, ranging from asymptomatic to severe respiratory and other symptoms.

Methods

Discovery dataset and processing

Gene expression data and corresponding phenotype data from human lung tissues (n=578) were obtained from the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) Portal (https://gtexportal.org), managed by the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Gene expression data were publicly available. Access to phenotype data required authorization. The GTEx protocol was previously described (29, 30). Briefly, total RNA was extracted from tissue. Following mRNA isolation, cDNA synthesis and library preparation, samples were subjected to HiSeq2000 or HiSeq2500 Illumina TrueSeq RNA sequencing. Gene expression levels were obtained using RNA-SeQC v1.1.9 (51) and expressed in transcripts per million (TPM). Reported expression levels were log2-transformed, unless otherwise indicated.

Validation dataset and processing

For validation purposes, the Laval University, University of British-Columbia, Groningen University (LUG) lung tissue dataset (n=1,349) was used. This dataset was accessed via Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo), accession number GSE23546, and was previously described (52). Briefly, total RNA from human lung tissue samples was isolated, quantified, quality-checked and used to generate cDNA, which was amplified and hybridized to Affymetrix gene expression arrays. Arrays were scanned and probe-level gene expression values were normalized using robust multichip average (RMA). These normalized values were obtained from GEO. To collapse probe-level expression data to single expression levels per gene, for each gene the probe with the highest median absolute deviation (MAD) was used. The MAD for each probe p was calculated using equation (1).

| (1) |

Herein, M is the median, pi denotes probe p’s expression level in sample i, and M(p) represents the median signal of probe p.

In silico cytometry

The levels of seven types of leukocytes involved in anti-viral cellular immune response, specifically CD8+ T cells, resting NK cells, activated NK cells, M1 macrophages, CD4+ T cells, dendritic cells and neutrophils, were estimated in the discovery and validation lung tissue samples using a previously described approach (31). Specifically, the following workflow was used. First, only non-log-transformed expression values were used. Thus, where required, expression values for all samples in the discovery and validation datasets were reverse-log2-transformed using equation 2.

| (2) |

Herein, c denotes the calculated non-log2-transformed expression counts and cl denotes the previously reported log2-transformed expression counts. Next, to compensate for potential technical differences between signatures and bulk sample gene expression values due to inter-platform variation, bulk-mode batch correction was applied. To ensure robustness, deconvolution was statistically analyzed using 100 permutations. Pearson correlation coefficients R, root mean squared errors (RMSA) and p values are reported on a per-sample level in Fig. S1a–c and Table S1.

Univariate statistical analyses

Log2-transformed expression levels of ACE2 in lung tissue samples were compared to the estimated levels of seven leukocyte types or states. Pearson correlation analyses were performed to determine Pearson correlation coefficients R and p values. P values were adjusted at a false discovery rate of 0.05 to yield q values, as previously described (53). Straight lines represent the minimized sum of squares of deviations of the data points with 95% confidence intervals shown. Continuous phenotypic covariates were analyzed in the same way and, additionally, as discrete ordinal categories after binning. Discrete and binned phenotype data were statistically evaluated using Mann-Whitney U tests. All analyses were performed in the R computing environment (R Project for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Multivariate regression analyses

Multivariate analyses were performed using standard ordinary least squares regression, summarized in equation 3.

| (3) |

Herein, β0 denotes the intercept, while βk represents the slope of each variable Xk in a model with n variables and ε denotes the random error component. These analyses was performed using R.

Messenger RNA and protein levels in human cells

Available ACE2 and TMPRSS2 mRNA and corresponding protein levels in 52 and 124 human cell lines, respectively, were obtained from references (54, 55). The correlations between mRNA and protein levels were analyzed by linear regression analysis using Pearson correlations. Pearson coefficients R for mRNA-protein level correlations were also determined for 12,015 other genes. To test whether the ACE2 and TMPRSS2 coefficients and p values were statistically significantly lower than for other genes, one-sample t tests were used.

Messenger RNA and protein levels in human tissues

Two types of analyses were performed to compare mRNA and protein levels in human tissues. First, mRNA expression levels from 40 human tissues were obtained from the Human Protein Atlas (https://www.proteinatlas.org). These represented the consensus normalized mRNA expression levels from three sources, specifically, Human Protein Atlas in-house RNAseq data, RNAseq data from the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project and CAGE data from FANTOM5 project. Corresponding ordinal human tissue protein expression levels (‘not detected’, ‘low’, ‘high’) were also obtained from the Human Protein Atlas. These were based on immunohistochemical staining of the tissues using DAB (3,3’-diaminobenzidine)-labeled antibodies (HPA000288, CAB026174), followed by knowledge-based annotation, as described on said website. A Kruskal-Wallis test was performed to assess whether mRNA and protein levels significantly correlated. Second, a meta-analysis was performed. For this, mRNA and protein expression levels were obtained from nine different sources. Tissue mRNA levels were obtained from six sources, as determined by Northern blot (56), quantitative RT-PCR (57), microarray hybridization (58), RNA sequencing (59) and cap analysis of gene expression (60). Tissue protein levels were obtained from three sources, as determined by mass spectrometry (61) and immunohistochemistry (39, 62). For each source and tissue, mRNA and protein expression levels were scored as ‘not detected’, ‘low’, ‘intermediate’ or ‘high’ and these received scores of 0–3, respectively. For each tissue, final mRNA and protein scores were calculated by averaging and scores from the respective six and three sources (Table S4). Strength and significance level of the correlation between the final scores were determined by linear regression analysis using Pearson correlation.

Cytokine levels in SARS-CoV-2-infected lung cells

SARS-CoV-2-induced fold increases in the expression levels of eight cytotoxic lymphocyte-attracting cytokines, CCL2–5, CXCL9, CXCL10, CXCL16 and IL18, were determined from reference (27). These represent fold increase in expression in Calu-3 lung cells, 24 hours after infection with SARS-CoV-2 at a multiplicity of infection of 2, compared to uninfected Calu-3 cells.

Cytokine levels in control and COVID-19 lung tissues

Baseline levels of above eight cytokines in lung tissues were obtained from the GTEX project, as described above, and compared to the baseline levels of ACE2, TMPRSS2, CD8+ T cells, resting and activated NK cells in these tissues, estimated as described above. Their levels were compared using Spearman’s rank correlations (R and p values). For comparison of cytokine levels in post-mortem COVID-19 lung tissues (n=2) to those in healthy, uninfected lung tissues (n=2), fold increases were determined following RNAseq analyses and previously reported (27).

Lymphocyte levels in COVID-19 bronchoalveolar lavages

The levels of CD8+ T cells, NK cells and inflammatory NK cells in bronchoalveolar lavages from mild (n=2) and severe (n=22) COVID-19 patients were reported elsewhere and determined using single-cell RNAseq (46). Statistical significance levels were assessed using Mann-Whitney U tests. The levels of T cells and NK cells, as well as CD8+ T cell tissue-resident signature score, in bronchoalveolar lavages from moderate (n=3) and severe/critical (n=5) COVID-19 patients were reported in another study (47).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

I thank Dr. Marianna Datseris, M.D. for critically reading the manuscript. This work was supported by the School of Biomedical Sciences, Queensland University of Technology. This study used publicly available and controlled data from the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) Project. GTEx was supported by the Common Fund of the Office of the Director of the National Institutes of Health (commonfund.nih.gov/GTEx). Additional funds were provided by the NCI, NHGRI, NHLBI, NIDA, NIMH, and NINDS. Donors were enrolled at Biospecimen Source Sites funded by NCI\Leidos Biomedical Research, Inc. subcontracts to the National Disease Research Interchange (10XS170), Roswell Park Cancer Institute (10XS171), and Science Care, Inc. (X10S172). The Laboratory, Data Analysis, and Coordinating Center (LDACC) was funded through a contract (HHSN268201000029C) to the The Broad Institute, Inc. Biorepository operations were funded through a Leidos Biomedical Research, Inc. subcontract to Van Andel Research Institute (10ST1035). Additional data repository and project management were provided by Leidos Biomedical Research, Inc. (HHSN261200800001E). The Brain Bank was supported supplements to University of Miami grant DA006227. Statistical Methods development grants were made to the University of Geneva (MH090941 & MH101814), the University of Chicago (MH090951, MH090937, MH101825, & MH101820), the University of North Carolina - Chapel Hill (MH090936), North Carolina State University (MH101819), Harvard University (MH090948), Stanford University (MH101782), Washington University (MH101810), and to the University of Pennsylvania (MH101822). The datasets used for the analyses described in this study were obtained from dbGaP at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gap through dbGaP accession number phs000424.v8.p2.

References

- 1.Coronaviridae Study Group of the International Committee on Taxonomy of V. 2020. The species Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus: classifying 2019-nCoV and naming it SARS-CoV-2. Nat Microbiol 5:536–544. 10.1038/s41564-020-0695-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu Y, Yan LM, Wan L, Xiang TX, Le A, Liu JM, Peiris M, Poon LLM, Zhang W. 2020. Viral dynamics in mild and severe cases of COVID-19. Lancet Infect Dis 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30232-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gattinoni L, Chiumello D, Caironi P, Busana M, Romitti F, Brazzi L, Camporota L. 2020. COVID-19 pneumonia: different respiratory treatments for different phenotypes? Intensive Care Med 10.1007/s00134-020-06033-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xie M and Chen Q. 2020. Insight into 2019 novel coronavirus - An updated interim review and lessons from SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV. Int J Infect Dis 94:119–124. 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.2020. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), Situation Report 102. World Health Organization [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li R, Pei S, Chen B, Song Y, Zhang T, Yang W, Shaman J. 2020. Substantial undocumented infection facilitates the rapid dissemination of novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2). Science 368:489–493. 10.1126/science.abb3221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Schroeder S, Kruger N, Herrler T, Erichsen S, Schiergens TS, Herrler G, Wu NH, Nitsche A, Muller MA, Drosten C, Pohlmann S. 2020. SARS-CoV-2 Cell Entry Depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and Is Blocked by a Clinically Proven Protease Inhibitor. Cell 181:271–280 e8. 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou P, Yang XL, Wang XG, Hu B, Zhang L, Zhang W, Si HR, Zhu Y, Li B, Huang CL, Chen HD, Chen J, Luo Y, Guo H, Jiang RD, Liu MQ, Chen Y, Shen XR, Wang X, Zheng XS, Zhao K, Chen QJ, Deng F, Liu LL, Yan B, Zhan FX, Wang YY, Xiao GF, Shi ZL. 2020. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature 579:270–273. 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wrapp D, Wang N, Corbett KS, Goldsmith JA, Hsieh CL, Abiona O, Graham BS, McLellan JS. 2020. Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation. Science 367:1260–1263. 10.1126/science.abb2507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hofmann H, Geier M, Marzi A, Krumbiegel M, Peipp M, Fey GH, Gramberg T, Pohlmann S. 2004. Susceptibility to SARS coronavirus S protein-driven infection correlates with expression of angiotensin converting enzyme 2 and infection can be blocked by soluble receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 319:1216–21. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.05.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mossel EC, Huang C, Narayanan K, Makino S, Tesh RB, Peters CJ. 2005. Exogenous ACE2 expression allows refractory cell lines to support severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus replication. J Virol 79:3846–50. 10.1128/JVI.79.6.3846-3850.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li W, Moore MJ, Vasilieva N, Sui J, Wong SK, Berne MA, Somasundaran M, Sullivan JL, Luzuriaga K, Greenough TC, Choe H, Farzan M. 2003. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is a functional receptor for the SARS coronavirus. Nature 426:450–4. 10.1038/nature02145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fang L, Karakiulakis G, Roth M. 2020. Are patients with hypertension and diabetes mellitus at increased risk for COVID-19 infection? Lancet Respir Med 8:e21 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30116-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guo J, Huang Z, Lin L, Lv J. 2020. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) and Cardiovascular Disease: A Viewpoint on the Potential Influence of Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors/Angiotensin Receptor Blockers on Onset and Severity of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Infection. J Am Heart Assoc 9:e016219 10.1161/JAHA.120.016219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhuang MW, Cheng Y, Zhang J, Jiang XM, Wang L, Deng J, Wang PH. 2020. Increasing host cellular receptor-angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 expression by coronavirus may facilitate 2019-nCoV (or SARS-CoV-2) infection. J Med Virol 10.1002/jmv.26139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sungnak W, Huang N, Becavin C, Berg M, Queen R, Litvinukova M, Talavera-Lopez C, Maatz H, Reichart D, Sampaziotis F, Worlock KB, Yoshida M, Barnes JL, Network HCALB. 2020. SARS-CoV-2 entry factors are highly expressed in nasal epithelial cells together with innate immune genes. Nat Med 10.1038/s41591-020-0868-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chu H, Chan JF, Wang Y, Yuen TT, Chai Y, Hou Y, Shuai H, Yang D, Hu B, Huang X, Zhang X, Cai JP, Zhou J, Yuan S, Kok KH, To KK, Chan IH, Zhang AJ, Sit KY, Au WK, Yuen KY. 2020. Comparative replication and immune activation profiles of SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV in human lungs: an ex vivo study with implications for the pathogenesis of COVID-19. Clin Infect Dis 10.1093/cid/ciaa410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chu H, Chan JFW, Yuen TTT, Shuai H, Yuan S, Wang Y, Hu B, Yip CCY, Tsang JOL, Huang X, Chai Y, Yang D, Hou Y, Chik KKH, Zhang X, Fung AYF, Tsoi HY, Cai JP, Chan WM, Ip JD, Chu AWH, Zhou J, Lung DC, Kok KH, To KKW, Tsang OTY, Chan KH, Yuen KY. 2020. Comparative tropism, replication kinetics, and cell damage profiling of SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV with implications for clinical manifestations, transmissibility, and laboratory studies of COVID-19: an observational study. Lancet Microbe April 21, 2020:1–10. 10.1016/S2666-5247(20)30004-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Newton AH, Cardani A, Braciale TJ. 2016. The host immune response in respiratory virus infection: balancing virus clearance and immunopathology. Semin Immunopathol 38:471–82. 10.1007/s00281-016-0558-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crouse J, Kalinke U, Oxenius A. 2015. Regulation of antiviral T cell responses by type I interferons. Nat Rev Immunol 15:231–42. 10.1038/nri3806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmidt ME and Varga SM. 2018. The CD8 T Cell Response to Respiratory Virus Infections. Front Immunol 9:678 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hammer Q, Ruckert T, Romagnani C. 2018. Natural killer cell specificity for viral infections. Nat Immunol 19:800–808. 10.1038/s41590-018-0163-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cook PC and MacDonald AS. 2016. Dendritic cells in lung immunopathology. Semin Immunopathol 38:449–60. 10.1007/s00281-016-0571-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sant AJ and McMichael A. 2012. Revealing the role of CD4(+) T cells in viral immunity. J Exp Med 209:1391–5. 10.1084/jem.20121517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harper RW. 2017. Partners in Crime: Epithelial Priming of Macrophages during Viral Infection. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 57:145–146. 10.1165/rcmb.2017-0153ED [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Galani IE and Andreakos E. 2015. Neutrophils in viral infections: Current concepts and caveats. J Leukoc Biol 98:557–64. 10.1189/jlb.4VMR1114-555R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blanco-Melo D, Nilsson-Payant BE, Liu WC, Uhl S, Hoagland D, Moller R, Jordan TX, Oishi K, Panis M, Sachs D, Wang TT, Schwartz RE, Lim JK, Albrecht RA, tenOever BR. 2020. Imbalanced Host Response to SARS-CoV-2 Drives Development of COVID-19. Cell 181:1036–1045 e9. 10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ziegler CGK, Allon SJ, Nyquist SK, Mbano IM, Miao VN, Tzouanas CN, Cao Y, Yousif AS, Bals J, Hauser BM, Feldman J, Muus C, Wadsworth MH 2nd, Kazer SW, Hughes TK, Doran B, Gatter GJ, Vukovic M, Taliaferro F, Mead BE, Guo Z, Wang JP, Gras D, Plaisant M, Ansari M, Angelidis I, Adler H, Sucre JMS, Taylor CJ, Lin B, Waghray A, Mitsialis V, Dwyer DF, Buchheit KM, Boyce JA, Barrett NA, Laidlaw TM, Carroll SL, Colonna L, Tkachev V, Peterson CW, Yu A, Zheng HB, Gideon HP, Winchell CG, Lin PL, Bingle CD, Snapper SB, Kropski JA, et al. 2020. SARS-CoV-2 Receptor ACE2 Is an Interferon-Stimulated Gene in Human Airway Epithelial Cells and Is Detected in Specific Cell Subsets across Tissues. Cell 181:1016–1035 e19. 10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Consortium GT. 2013. The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project. Nat Genet 45:580–5. 10.1038/ng.2653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Consortium GT, Laboratory DA, Coordinating Center -Analysis Working G, Statistical Methods groups-Analysis Working G, Enhancing Gg, Fund NIHC, Nih/Nci, Nih/Nhgri, Nih/Nimh, Nih/Nida, Biospecimen Collection Source Site N, Biospecimen Collection Source Site R, Biospecimen Core Resource V, Brain Bank Repository-University of Miami Brain Endowment B, Leidos Biomedical-Project M, Study E, Genome Browser Data I, Visualization EBI, Genome Browser Data I, Visualization-Ucsc Genomics Institute UoCSC, Lead a, Laboratory DA, Coordinating C, management NIHp, Biospecimen c, Pathology, e QTLmwg, Battle A, Brown CD, Engelhardt BE, Montgomery SB. 2017. Genetic effects on gene expression across human tissues. Nature 550:204–213. 10.1038/nature24277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Newman AM, Liu CL, Green MR, Gentles AJ, Feng W, Xu Y, Hoang CD, Diehn M, Alizadeh AA. 2015. Robust enumeration of cell subsets from tissue expression profiles. Nat Methods 12:453–7. 10.1038/nmeth.3337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brown CE, Vishwanath RP, Aguilar B, Starr R, Najbauer J, Aboody KS, Jensen MC. 2007. Tumor-derived chemokine MCP-1/CCL2 is sufficient for mediating tumor tropism of adoptively transferred T cells. J Immunol 179:3332–41. 10.4049/jimmunol.179.5.3332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Serody JS, Burkett SE, Panoskaltsis-Mortari A, Ng-Cashin J, McMahon E, Matsushima GK, Lira SA, Cook DN, Blazar BR. 2000. T-lymphocyte production of macrophage inflammatory protein-1alpha is critical to the recruitment of CD8(+) T cells to the liver, lung, and spleen during graft-versus-host disease. Blood 96:2973–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zumwalt TJ, Arnold M, Goel A, Boland CR. 2015. Active secretion of CXCL10 and CCL5 from colorectal cancer microenvironments associates with GranzymeB+ CD8+ T-cell infiltration. Oncotarget 6:2981–91. 10.18632/oncotarget.3205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spranger S, Dai D, Horton B, Gajewski TF. 2017. Tumor-Residing Batf3 Dendritic Cells Are Required for Effector T Cell Trafficking and Adoptive T Cell Therapy. Cancer Cell 31:711–723 e4. 10.1016/j.ccell.2017.04.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wendel M, Galani IE, Suri-Payer E, Cerwenka A. 2008. Natural killer cell accumulation in tumors is dependent on IFN-gamma and CXCR3 ligands. Cancer Res 68:8437–45. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fan Z, Yu P, Wang Y, Wang Y, Fu ML, Liu W, Sun Y, Fu YX. 2006. NK-cell activation by LIGHT triggers tumor-specific CD8+ T-cell immunity to reject established tumors. Blood 107:1342–51. 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bertram S, Heurich A, Lavender H, Gierer S, Danisch S, Perin P, Lucas JM, Nelson PS, Pohlmann S, Soilleux EJ. 2012. Influenza and SARS-coronavirus activating proteases TMPRSS2 and HAT are expressed at multiple sites in human respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts. PLoS One 7:e35876 10.1371/journal.pone.0035876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hamming I, Timens W, Bulthuis ML, Lely AT, Navis G, van Goor H. 2004. Tissue distribution of ACE2 protein, the functional receptor for SARS coronavirus. A first step in understanding SARS pathogenesis. J Pathol 203:631–7. 10.1002/path.1570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zou X, Chen K, Zou J, Han P, Hao J, Han Z. 2020. Single-cell RNA-seq data analysis on the receptor ACE2 expression reveals the potential risk of different human organs vulnerable to 2019-nCoV infection. Front Med 10.1007/s11684-020-0754-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, Zhang L, Fan G, Xu J, Gu X, Cheng Z, Yu T, Xia J, Wei Y, Wu W, Xie X, Yin W, Li H, Liu M, Xiao Y, Gao H, Guo L, Xie J, Wang G, Jiang R, Gao Z, Jin Q, Wang J, Cao B. 2020. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 395:497–506. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chan JF, Yuan S, Kok KH, To KK, Chu H, Yang J, Xing F, Liu J, Yip CC, Poon RW, Tsoi HW, Lo SK, Chan KH, Poon VK, Chan WM, Ip JD, Cai JP, Cheng VC, Chen H, Hui CK, Yuen KY. 2020. A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: a study of a family cluster. Lancet 395:514–523. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30154-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Diao B, Wang C, Tan Y, Chen X, Liu Y, Ning L, Chen L, Li M, Liu Y, Wang G, Yuan Z, Feng Z, Zhang Y, Wu Y, Chen Y. 2020. Reduction and Functional Exhaustion of T Cells in Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Front Immunol 11:827 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zheng M, Gao Y, Wang G, Song G, Liu S, Sun D, Xu Y, Tian Z. 2020. Functional exhaustion of antiviral lymphocytes in COVID-19 patients. Cell Mol Immunol 10.1038/s41423-020-0402-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu J, Li S, Liu J, Liang B, Wang X, Wang H, Li W, Tong Q, Yi J, Zhao L, Xiong L, Guo C, Tian J, Luo J, Yao J, Pang R, Shen H, Peng C, Liu T, Zhang Q, Wu J, Xu L, Lu S, Wang B, Weng Z, Han C, Zhu H, Zhou R, Zhou H, Chen X, Ye P, Zhu B, Wang L, Zhou W, He S, He Y, Jie S, Wei P, Zhang J, Lu Y, Wang W, Zhang L, Li L, Zhou F, Wang J, Dittmer U, Lu M, Hu Y, Yang D, et al. 2020. Longitudinal characteristics of lymphocyte responses and cytokine profiles in the peripheral blood of SARS-CoV-2 infected patients. EBioMedicine 55:102763 10.1016/j.ebiom.2020.102763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wauters E, Van Mol P, Garg AD, Jansen S, Van Herck Y, Vanderbeke L, Bassez A, Boeckx B, Malengier-Devlies B, Timmerman A, Van Brussel T, Van Buyten T, Schepers R, Heylen E, Dauwe D, Dooms C, Gunst J, Hermans G, Meersseman P, Testelmans D, Yserbyt J, Matthys P, Tejpar S, CONTAGIOUS collaborators, Neyts J, Wauters J, Qian J, Lambrechts D. 2020. Discriminating mild from critical COVID-19 by innate and adaptive immune single-cell profiling of bronchoalveolar lavages. bioRxiv Preprint:10 July 2020. 10.1101/2020.07.09.196519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liao M, Liu Y, Yuan J, Wen Y, Xu G, Zhao J, Cheng L, Li J, Wang X, Wang F, Liu L, Amit I, Zhang S, Zhang Z. 2020. Single-cell landscape of bronchoalveolar immune cells in patients with COVID-19. Nat Med 26:842–844. 10.1038/s41591-020-0901-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lloyd-Sherlock P, Ebrahim S, Geffen L, McKee M. 2020. Bearing the brunt of covid-19: older people in low and middle income countries. BMJ 368:m1052 10.1136/bmj.m1052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang X, Yu Y, Xu J, Shu H, Xia J, Liu H, Wu Y, Zhang L, Yu Z, Fang M, Yu T, Wang Y, Pan S, Zou X, Yuan S, Shang Y. 2020. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir Med 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30079-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smith JC, Sausville EL, Girish V, Yuan ML, Vasudevan A, John KM, Sheltzer JM. 2020. Cigarette Smoke Exposure and Inflammatory Signaling Increase the Expression of the SARS-CoV-2 Receptor ACE2 in the Respiratory Tract. Dev Cell 53:514–529 e3. 10.1016/j.devcel.2020.05.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.DeLuca DS, Levin JZ, Sivachenko A, Fennell T, Nazaire MD, Williams C, Reich M, Winckler W, Getz G. 2012. RNA-SeQC: RNA-seq metrics for quality control and process optimization. Bioinformatics 28:1530–2. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Obeidat M, Hao K, Bosse Y, Nickle DC, Nie Y, Postma DS, Laviolette M, Sandford AJ, Daley DD, Hogg JC, Elliott WM, Fishbane N, Timens W, Hysi PG, Kaprio J, Wilson JF, Hui J, Rawal R, Schulz H, Stubbe B, Hayward C, Polasek O, Jarvelin MR, Zhao JH, Jarvis D, Kahonen M, Franceschini N, North KE, Loth DW, Brusselle GG, Smith AV, Gudnason V, Bartz TM, Wilk JB, O’Connor GT, Cassano PA, Tang W, Wain LV, Soler Artigas M, Gharib SA, Strachan DP, Sin DD, Tobin MD, London SJ, Hall IP, Pare PD. 2015. Molecular mechanisms underlying variations in lung function: a systems genetics analysis. Lancet Respir Med 3:782–95. 10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00380-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Benjamini Y and Hochberg Y. 1995. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Ser B-Stat Methodol 57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ghandi M, Huang FW, Jane-Valbuena J, Kryukov GV, Lo CC, McDonald ER, 3rd, Barretina J, Gelfand ET, Bielski CM, Li H, Hu K, Andreev-Drakhlin AY, Kim J, Hess JM, Haas BJ, Aguet F, Weir BA, Rothberg MV, Paolella BR, Lawrence MS, Akbani R, Lu Y, Tiv HL, Gokhale PC, de Weck A, Mansour AA, Oh C, Shih J, Hadi K, Rosen Y, Bistline J, Venkatesan K, Reddy A, Sonkin D, Liu M, Lehar J, Korn JM, Porter DA, Jones MD, Golji J, Caponigro G, Taylor JE, Dunning CM, Creech AL, Warren AC, McFarland JM, Zamanighomi M, Kauffmann A, Stransky N, et al. 2019. Next-generation characterization of the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia. Nature 569:503–508. 10.1038/s41586-019-1186-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nusinow DP, Szpyt J, Ghandi M, Rose CM, McDonald ER 3rd, Kalocsay M, Jane-Valbuena J, Gelfand E, Schweppe DK, Jedrychowski M, Golji J, Porter DA, Rejtar T, Wang YK, Kryukov GV, Stegmeier F, Erickson BK, Garraway LA, Sellers WR, Gygi SP. 2020. Quantitative Proteomics of the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia. Cell 180:387–402 e16. 10.1016/j.cell.2019.12.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tipnis SR, Hooper NM, Hyde R, Karran E, Christie G, Turner AJ. 2000. A human homolog of angiotensin-converting enzyme. Cloning and functional expression as a captopril-insensitive carboxypeptidase. J Biol Chem 275:33238–43. 10.1074/jbc.M002615200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Harmer D, Gilbert M, Borman R, Clark KL. 2002. Quantitative mRNA expression profiling of ACE 2, a novel homologue of angiotensin converting enzyme. FEBS Lett 532:107–10. 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03640-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wu C, Jin X, Tsueng G, Afrasiabi C, Su AI. 2016. BioGPS: building your own mash-up of gene annotations and expression profiles. Nucleic Acids Res 44:D313–6. 10.1093/nar/gkv1104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Uhlen M, Zhang C, Lee S, Sjostedt E, Fagerberg L, Bidkhori G, Benfeitas R, Arif M, Liu Z, Edfors F, Sanli K, von Feilitzen K, Oksvold P, Lundberg E, Hober S, Nilsson P, Mattsson J, Schwenk JM, Brunnstrom H, Glimelius B, Sjoblom T, Edqvist PH, Djureinovic D, Micke P, Lindskog C, Mardinoglu A, Ponten F. 2017. A pathology atlas of the human cancer transcriptome. Science 357: 10.1126/science.aan2507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Consortium F, the RP, Clst, Forrest AR, Kawaji H, Rehli M, Baillie JK, de Hoon MJ, Haberle V, Lassmann T, Kulakovskiy IV, Lizio M, Itoh M, Andersson R, Mungall CJ, Meehan TF, Schmeier S, Bertin N, Jorgensen M, Dimont E, Arner E, Schmidl C, Schaefer U, Medvedeva YA, Plessy C, Vitezic M, Severin J, Semple C, Ishizu Y, Young RS, Francescatto M, Alam I, Albanese D, Altschuler GM, Arakawa T, Archer JA, Arner P, Babina M, Rennie S, Balwierz PJ, Beckhouse AG, Pradhan-Bhatt S, Blake JA, Blumenthal A, Bodega B, Bonetti A, Briggs J, Brombacher F, Burroughs AM, et al. 2014. A promoter-level mammalian expression atlas. Nature 507:462–70. 10.1038/nature13182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kim MS, Pinto SM, Getnet D, Nirujogi RS, Manda SS, Chaerkady R, Madugundu AK, Kelkar DS, Isserlin R, Jain S, Thomas JK, Muthusamy B, Leal-Rojas P, Kumar P, Sahasrabuddhe NA, Balakrishnan L, Advani J, George B, Renuse S, Selvan LD, Patil AH, Nanjappa V, Radhakrishnan A, Prasad S, Subbannayya T, Raju R, Kumar M, Sreenivasamurthy SK, Marimuthu A, Sathe GJ, Chavan S, Datta KK, Subbannayya Y, Sahu A, Yelamanchi SD, Jayaram S, Rajagopalan P, Sharma J, Murthy KR, Syed N, Goel R, Khan AA, Ahmad S, Dey G, Mudgal K, Chatterjee A, Huang TC, Zhong J, Wu X, et al. 2014. A draft map of the human proteome. Nature 509:575–81. 10.1038/nature13302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Thul PJ, Akesson L, Wiking M, Mahdessian D, Geladaki A, Ait Blal H, Alm T, Asplund A, Bjork L, Breckels LM, Backstrom A, Danielsson F, Fagerberg L, Fall J, Gatto L, Gnann C, Hober S, Hjelmare M, Johansson F, Lee S, Lindskog C, Mulder J, Mulvey CM, Nilsson P, Oksvold P, Rockberg J, Schutten R, Schwenk JM, Sivertsson A, Sjostedt E, Skogs M, Stadler C, Sullivan DP, Tegel H, Winsnes C, Zhang C, Zwahlen M, Mardinoglu A, Ponten F, von Feilitzen K, Lilley KS, Uhlen M, Lundberg E. 2017. A subcellular map of the human proteome. Science 356: 10.1126/science.aal3321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.