Abstract

Multidrug-resistant (MDR) Acinetobacter baumannii is a critical threat to global health. The type strain ATCC 19606 has been widely used in studying the virulence, pathogenesis and mechanisms of antimicrobial resistance in A. baumannii. However, the lack of a complete genome sequence is a hindrance towards detailed bioinformatic studies. Here we report the generation of a complete genome for ATCC 19606 using PacBio sequencing. ATCC 19606 genome consists of a 3,980,848-bp chromosome and a 9,450-bp plasmid pMAC, and harbours a chromosomal dihydropteroate synthase gene sul2 conferring resistance to sulphonamides and a plasmid-borne ohr gene conferring resistance to peroxides. The genome also contains 69 virulence genes involved in surface adherence, biofilm formation, extracellular phospholipase, iron uptake, immune evasion and quorum sensing. Insertion sequences ISCR2 and ISAba11 are embedded in a 36.1-Kb genomic island, suggesting an IS-mediated large-scale DNA recombination. Furthermore, a genome-scale metabolic model (GSMM) iATCC19606v2 was constructed using the complete genome annotation. The model iATCC19606v2 incorporated a periplasmic compartment, 1,422 metabolites, 2,114 reactions and 1,009 genes, and a set of protein crowding constraints taking into account enzyme abundance limitation. The prediction of bacterial growth on 190 carbon and 95 nitrogen sources achieved a high accuracy of 85.6% compared to Biolog experiment results. Based upon two transposon mutant libraries of AB5075 and ATCC 17978, the predictions of essential genes reached the accuracy of 87.6% and 82.1%, respectively. Together, the complete genome sequence and high-quality GSMM iATCC19606v2 provide valuable tools for antimicrobial systems pharmacological investigations on A. baumannii.

Keywords: Acinetobacter baumannii, antimicrobial resistance, virulence factor, insertion sequence, genomic island, genome-scale metabolic modelling

Introduction

Multidrug-resistant (MDR) Acinetobacter baumannii is a critical threat to global health and often the causative agent in nosocomial infections including pneumoniae, bacteremia, wound sepsis and urinary tract infections (Harding et al., 2018). Alarmingly, outbreaks of MDR A. baumannii infections have been increasingly reported over the last decades (Dijkshoorn et al., 2007), and the World Health Organization has urged the development of novel antibiotics for this high-priority pathogen (World Health Organization, 2017). Three major clonal lineages, namely International Clone (IC) I to III, exist in A. baumannii and are resistant to almost all commonly used antibiotics (Diancourt et al., 2010).

A. baumannii ATCC 19606 is one of the best characterised strains in this species (Hugh and Reese, 1967). Historically, this strain was firstly isolated in a patient urine sample from US prior to 1949 (Hugh and Reese, 1967). It was assigned type O by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis and ST52 by multi-locus sequence typing (MLST) (Giannouli et al., 2013). As a type strain of A. baumannii, ATCC 19606 has been widely employed in studying antimicrobial resistance (Hamidian and Hall, 2017; Krizova et al., 2013; Moffatt et al., 2010), virulence (Gaddy et al., 2012; Luo et al., 2015), and host-pathogen interactions (Bhuiyan et al., 2016; de Breij et al., 2009; Harris et al., 2013; Pachon-Ibanez et al., 2010). It is resistant to sulphonamides but remains susceptible to a range of other antibiotics (Hamidian and Hall, 2017; Krizova et al., 2013). Loss of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) is a unique polymyxin resistance mechanism which was firstly discovered in ATCC 19606 (Moffatt et al., 2010). Furthermore, a number of virulence factors were studied in ATCC 19606, including acinetobactin responsible for iron acquisition (Gaddy et al., 2012), LPS related to the evasion of host immune system (Shibuya et al., 2010), and outer membrane vesicle associated with toxins trafficking (Jin et al., 2011). Several infection models (e.g. pneumoniae and meningitis) were established with ATCC 19606 to investigate the survival, immune response, antimicrobial pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics (Harris et al., 2013; Pachon-Ibanez et al., 2010). Systems pharmacology and genome-scale metabolic modelling are valuable approaches for elucidating the mechanisms of antimicrobial activity and resistance (Han et al., 2019; Maifiah et al., 2016; Zhu et al., 2019). However, functional studies with A. baumannii ATCC 19606 is limited by the lack of a complete genome sequence and poor annotation of its genomic content.

Next-generation sequencing has revolutionised biological research by rapidly generating high-throughput sequence data (Goodwin et al., 2016). However, obtaining complete bacterial genomes is still challenging due to the presence of highly repetitive DNA sequences (Treangen and Salzberg, 2011). Resolving these ambiguous genomic regions often requires costly and time-consuming finishing procedures (Treangen and Salzberg, 2011; van Dijk et al., 2018). Consequently, most draft genomes were heavily fragmented into hundreds of contigs, which limits their reuse in comparative, functional, clinical and epidemiological studies (van Dijk et al., 2018). The third-generation sequencing platforms such as Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) can produce long reads (up to 30 Kb) that are capable of spanning large repeat regions, thereby facilitating the generation of complete genome assemblies (Ardui et al., 2018; Goodwin et al., 2016). In the present study, we report the first complete genome of A. baumannii ATCC 19606 using PacBio RSII sequencing platform, characterisation of its key genomic features and construction of the genome-scale metabolic model (GSMM). Overall, the generated ATCC 19606 genome and GSMM will serve as valuable resources for functional genomic and bioinformatic analyses in A. baumannii.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial strain, media and antimicrobial susceptibility test

A. baumannii ATCC 19606 was purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, US), and cultured on nutrient agar (Oxoid, UK) or in cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth (CaMHB, Oxoid). Tryptic soy broth (Oxoid) supplemented with 20% glycerol was used for storage at −80°C. The susceptibility to polymyxin B, colistin, chloramphenicol, doripenem, erythromycin, streptomycin, rifampicin and tetracycline was tested using broth microdilution method according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute guidelines (CLSI, 2018), while the susceptibility to other antibiotics was evaluated using VITEK 2 at Alfred Pathology Service (Alfred Hospital, Melbourne, Australia) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Minimum inhibitory concentrations of antimicrobials against A. baumannii ATCC 19606.

| Antibiotic | MIC (mg/L) |

|---|---|

| Colistin | 1 |

| Polymyxin B | 1 |

| Amikacin | ≤2 |

| Amoxicillin/Clavulanic acid | ≥32 |

| Ampicillin | ≥32 |

| Cefazolin | ≥64 |

| Cefepime | 16 |

| Cefoxitin | ≥64 |

| Ceftazidime | 8 |

| Ceftriaxone | 16 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 1 |

| Chloramphenicol | >64 |

| Doripenem | 1 |

| Erythromycin | 16 |

| Gentamicin | 4 |

| Meropenem | 1 |

| Nalidixic Acid | <2 |

| Nitrofurantoin | 256 |

| Norfloxacin | 8 |

| Piperacillin/Tazobactam | 16 |

| Streptomycin | 32 |

| Rifampicin | 1 |

| Tetracycline | 1 |

| Ticarcillin/Clavulanic Acid | ≤8 |

| Tobramycin | ≤1 |

| Trimethoprim | 8 |

| Trimethoprim/Sulfamethoxazole | 160 |

Genomic DNA extraction and sequencing

Genomic DNA was extracted from a log-phase culture using QIAGEN Genomic-Tip 100/G and Genomic DNA Buffer Set as per manufacturer’s instructions. Nanodrop (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) was employed to assess DNA purity and Qubit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used to validate dsDNA content. DNA fragment size was checked by Pippin Pulse Electrophoresis (Sage Science, USA). A 15-20 Kb Genomic P6 Library was constructed for PacBio SMRT (Single Molecule Real-Time) sequencing (Ramaciotti Centre for Genomics, Sydney, Australia). Genome sequencing using PacBio RSII platform produced 657-Mb data (57,328 reads with the length of 1,000-50,923 bp, accession SRR10295884 in NCBI SRA database), representing approximately 170-fold coverage of the genome.

De novo assembly, validation and annotation

SMRT Analysis 2.3 (Pacific BioSciences, USA) was employed to assemble draft chromosome using PacBio reads. Meanwhile, plasmidSPAdes was used to assemble plasmid fragments using PacBio reads combined with previous Illumina short reads (SRR2180354) (Antipov et al., 2016; Davenport et al., 2014). Previously published RNA-Seq reads (SRR331096 and SRR331097) were aligned to the assembly using SubRead aligner for validation (Henry et al., 2015; Henry et al., 2012; Liao et al., 2013). Single nucleotide variations (SNVs) were identified using freebayes module from nesoni, and corrected in the assembly (Harrison and Seemann, 2009). Manual genome finishing was performed using Blastn and Sanger sequencing at Monash Micromon (Clayton, Australia) with designed primers (19606pF 5’-CTCTTGTGTTGCTTCATCTTGCT-3’ and 19606pR 5’-GGGCTATCAACTAGAAATTACGG-3’). In order to determine the genetic variations potentially accumulated during propagation and transmission, previously published DNA-Seq reads of ATCC 19606 (ASM16229v1, Acin_baum_CIP_70_34T_V1, ASM61470v1, ASM73714v1 and ASM281117v1) were aligned with our completed genome using SubRead; the genetic variations were detected using freebayes and GRIDSS (Cameron et al., 2017; Liao et al., 2013). ProgressiveMauve was used to compare previous draft genomes with our assembly (Darling et al., 2010). The genome was annotated by NCBI Prokaryotic Genome Annotation Pipeline and insertion sequences (ISs) were predicted using ISEScan (Xie and Tang, 2017). Antimicrobial resistance genes were predicted by RGI 3.2.1 from Comprehensive Antimicrobial Resistance Database (CARD) (Jia et al., 2017) and virulence genes were predicted using VFanalyzer (Liu et al., 2019). IslandViewer 4 was employed to analyse genomic islands (Bertelli et al., 2017).

Comparative analysis with other A. baumannii genomes

The core genome of ATCC 19606 and another 97 A. baumannii strains with complete genome sequences were identified using Roary with criteria of amino acid sequence identity > 95% (Page et al., 2015) and presence in 99% of genomes. The derived core genome alignment was employed to estimate Maximum-Likelihood (ML) tree using RAxML 8.2.9 with the GTRGAMMA model (250 bootstrap replicates, MRE-based bootstrapping criterion) (Stamatakis, 2014). The tree was visualised using iTOL v4.4.2 (Letunic and Bork, 2019). To determine the large-scale structural variation in the genome, 7 commonly used A. baumannii strains representing IC I (AYE and AB5075), IC II (MDR-TJ and ACICU), IC III (OIFC137), and non-IC lineages (ATCC 17978 for ST437 and SDF for ST17), were selected as comparators. The genomes were aligned by progressiveMauve with default settings (Darling et al., 2010).

Construction of the genome-scale metabolic model (GSMM)

With the complete genome of ATCC 19606, a GSMM was constructed using CarveMe (Machado et al., 2018). Biolog phenotype microarrays (PMs) (Cell Biosciences, Australia) were employed to test the utilisation of 95 nitrogen sources, with two independent biological replicates (Zhu et al., 2018; Zhu et al., 2019). The obtained results, together with previous carbon source utilisation data (Zhu et al., 2019), were employed for model prediction assessment. To improve prediction of metabolic flux vj, protein crowding constraints were incorporated into the model based on the formula below:

where reaction flux vj is limited by the enzyme turnover rate kcat and enzyme molar abundance ej. In Escherichia coli, the total proteins accounted for 0.56 gram per gram cell dry weight (g·gDW−1) and the metabolic enzymes accounted for approximately 44% (w/w) of the total proteins (Adadi et al., 2012; Li et al., 2014). Due to the lack of quantitative proteomics data in A. baumannii, we used E. coli data to constrain the abundance of metabolic enzymes (P) to 0.25 g·gDW−1 (0.56 g·gDW−1×0.44). The molecular weight (MWj) of each protein was calculated based on its amino acid sequence. Due to the lack of kinetics data in A. baumannii, the enzyme turnover kcat was set to the median (65 s−1) in E. coli (O’Brien et al., 2013). Flux balance analysis (FBA) and gene essentiality analysis were conducted using COBRA toolbox 3.0 (Heirendt et al., 2019). Dynamic flux balance analysis was conducted with an initial biomass of 1 μg/L (105-106 cells per litre) and each amino acid or dipeptide nutrient in Mueller Hinton broth at a concentration of 1 mM. Two transposon libraries for A. baumannii AB5075 (in Luria-Bertani media) and ATCC 17978 (in M9 media with citrate as the sole carbon source) were employed to assess the accuracy of gene essentiality prediction (Gallagher et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2014).

Results

Genome sequencing, assembly and validation

A. baumannii ATCC 19606 was susceptible to a variety of antibiotics, including amikacin, gentamicin, tobramycin, ciprofloxacin, doripenem, meropenem and polymyxins (i.e. polymyxin B and colistin), but resistant to ampicillin, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, cefazolin, cefoxitin, nitrofurantoin, trimethoprim, and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (Table 1). After overlap filtering, read correction and quality trimming, 6,457 PacBio sequencing reads were generated, with the total length of 137,616,780 bp. De novo assembly using these reads yielded a single contig with the length of 4,009,504 bp. In this contig, the head sequence (1-28,657 bp) was overlapped with the tail sequence (3,980,855-4,009,504 bp). The overlapping 3′- and 5′-ends were then trimmed and joined together, and the contig joint was confirmed by PCR and Sanger sequencing. By aligning our previous RNA-Seq reads to the draft chromosome, two high-quality SNVs (855,646T>C, 359,810C>CC) were identified and corrected in the chromosome, resulting in a 3,980,848-bp, single circular chromosome (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

Overview of the complete A. baumannii ATCC 19606 genome. Chromosome: (A) From the outermost to innermost, the tracks indicate the genes on positive strand (dark blue) and negative strand (light blue), ORFs (with colours indicating COG classifications), tRNA (light green), rRNA (dark green), IS elements (dark red), genomic islands (red), prophages (light red), GC content (green) and GC skew (orange for positive and purple for negative). (B) Plasmid pMAC: from the outermost to innermost, the tracks indicate the genes on positive strand (dark blue) and negative strand (light blue), ORFs (with colours indicating COG groups), GC content (green) and GC skew (orange for positive and purple for negative).

Previous study indicated the presence of a plasmid in ATCC 19606, but our initial assembly discovered only a chromosome (Dorsey et al., 2006). Therefore, plasmidSpades was employed to assemble the plasmid using our PacBio reads and the parallel sequencing reads (SRX1163030, 100-bp single-end Illumina library with 295-fold genome-coverage) (Davenport et al., 2014). As a result, three draft plasmids were identified with the estimated lengths of 22.2, 16.7 and 15.1 Kb, respectively. Among them, the 22.2 and 15.1 Kb plasmids showed high-level homology with the assembled chromosome above, indicating they might have been integrated into chromosome already. Interestingly, the third 16.7-Kb draft plasmid, consisting of five >500-bp contigs, showed high identity (>99%) with the reported 16,340-bp plasmid contig (KL810967) (Davenport et al., 2014). Furthermore, three of these five plasmid fragments were perfectly aligned to the reported ATCC 19606 plasmid pMAC (AY541809, Fig. 1B) (Dorsey et al., 2006). Therefore, the 9,540-bp plasmid pMAC was involved in the final genome of ATCC 19606.

Together, a 3,990,388-bp unambiguously assembled genome sequence was obtained for ATCC 19606, consisting of a 3,980,848-bp chromosome and a 9,540-bp plasmid pMAC, with an average GC content of 39.2% and 34.7%, respectively (Fig. 1). The genome sequence is now publicly available under GenBank Accession CP046654-CP046655. Thus far, there are 5 draft assemblies of ATCC 19606 (Materials and Methods) in GenBank. We compared them with our completed genome and identified a variety of sequence variations in these draft genomes, including SNVs, large DNA rearrangements, missing and duplicating DNA fragments (Fig. S1A). Significant annotation discrepancies were also observed in these draft genomes, where 28-82 genes were differentially annotated compared to our complete genome (Fig. S1B). These annotation discrepancies could significantly affect transcriptomic analysis. For instance, a previous RNA-Seq study with a draft genome ASM16229v1 as the reference discovered 469 differentially expressed genes (DEGs, fold change ≥ 2, FDR-adjusted P value ≤ 0.01) after 2 mg/L colistin treatment for 1 h, compared to untreated controls (Henry et al., 2015). Whereas using our complete genome as reference, 436 DEGs were obtained with the same criteria; among them, 39 DEGs were newly identified and 72 previously identified DEGs were absent in our results (Fig. S2, Table S6).

Antibiotic resistance and virulence genes

Annotation of A. baumannii ATCC 19606 genome generated 3,805 genes, encoding 3,663 proteins, 74 tRNAs and 4 ncRNA (Fig. 1). With MLST Pasteur (cpn60-fusA-gltA-pyrG-recA-rplB-rpoB, 3-2-2-7-9-1-5) scheme, ATCC 19606 was determined as ST52, consistent with the previous classification (Karah et al., 2017). Overall, 3,209 protein-coding genes (87.6% of 3,663 ORFs) were assigned with COG classes (Fig. 1, Table S1). Analysis of antibiotic-resistant determinants showed the presence of 14 efflux pump associated genes, including the regulators (adeRS [GO593_16535-6540], adeL [GO593_00400], adeN [GO593_17770]), resistance-nodulation-cell division (RND) type efflux pumps (adeAB [GO593_16530-16525], adeFGH [GO593_00405-00415] and adeIJK [GO593_02675-02685]), small multidrug resistance (SMR) type efflux pump (abeS [GO593_00375]), and multidrug and toxic compound extrusion (MATE) type efflux pump (abeM [GO593_08465]) (Fig. 2A). β-lactamase genes blaOXA-98 (GO593_15270) and blaADC-CIP 70-34T (GO593_01070) were discovered. blaADC-CIP 70-34T was previously reported (Perichon et al., 2014) and had only one amino acid variation compared to blaADC-2. These two genes could confer only a low-level resistance to several β-lactams (e.g. ampicillin, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, cefazolin, cefoxitin, Table 1), probably owing to the absence of a strong promoter to drive the expression of these genes (Perichon et al., 2014). Genes ant(3’’)-IIa (GO593_07260) and sul2 (GO593_06680) were associated with resistance to streptomycin and sulphonamides, respectively. Compared to IC I-III strains, ATCC 19606 contains significantly less genes associated with the resistance to aminoglycosides and β-lactams, and no genes related to the resistance to chloramphenicol, trimethoprim, erythromycin, rifampicin and tetracycline, which is consistent with most of its antimicrobial susceptibility profile (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Antimicrobial resistance genes (A) and virulence genes (B) predicted in A. baumannii strains ATCC 19606, AYE, AB5075, MDR-TJ, ACICU, OIFC137, ATCC 17978 and SDF. The red (blue) lattice indicates the presence of antimicrobial resistance and virulence genes, whereas empty lattice indicates absence. The classes of antimicrobial resistance and virulence genes are indicated by colour bars aside. Strains of IC I, II and III are indicated by red, blue and green, respectively.

ATCC 19606 genome encodes 69 virulence genes, including those associated with adherence, biofilm formation, phospholipase, iron uptake, immune evasion and quorum sensing (Fig. 2B). Previously, pilE was identified as truncated form in ATCC 19606 due to an adenosine deletion (Eijkelkamp et al., 2014); whereas in our assembly the coding sequence (GO593_04700) is intact. Interestingly, ATCC 19606 contains a limited number of genes associated with heme utilisation, serum and acid resistance, indicating a relatively weak capability in host adaptation compared to other IC I-III strains (Fig. 2B).

Mobile elements

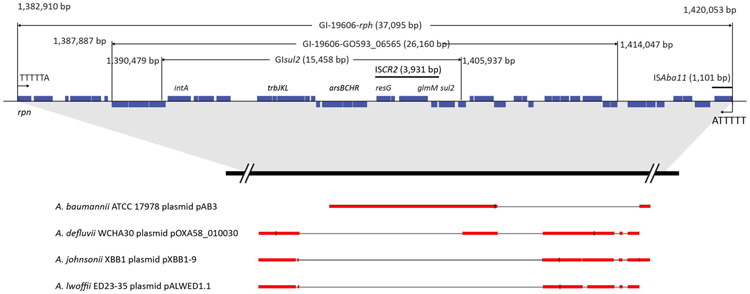

Overall, five IS elements ranging from 1,101 to 2,727 bp were predicted in ATCC 19606 genome, including 2 IS701 and 3 elements from IS21, IS91, IS110, respectively (Table 2). The two IS701 elements (1,418,952-1,420,052 bp and 3,973,359-3,974,459 bp) showed 100% nucleotide sequence identity with the published ISAba11 (JF309050). The 2.3-Kb IS91 element contains the reported ISVsa3 (AJ289135) from 531 to 1,507 bp. It also showed 100% sequence identity with the upstream part (−2,299 to −84 bp) of previously reported ISCR2 (3,931 bp, FN293019). Further alignment confirmed the presence of an intact ISCR2 (1,401,623-1,405,635 bp) in ATCC 19606 genome. ISCR2 consists of dihydropteroate synthase sul2, phosphoglucosamine mutase glm (GO593_06675), a hypothetical gene (GO593_06670), ISCR2 transposase (GO593_06665) and resolvase gene res (GO593_06660); ISCR2 is also known as a vector associated with the dissemination of multidrug resistance (Poirel et al., 2009; Vilacoba et al., 2013; Xu et al., 2017). In the ATCC 19606 genome, ISCR2 is located in a 15.4-Kb integrating element GIsul2 (1,390,479-1,405,937 bp, Fig. 3) (Hamidian and Hall, 2017; Harmer et al., 2017; Nigro and Hall, 2011). GIsul2 is located on the anti-sense strand, with dihydropteroate synthase sul2 and prophage integrase intA (GO593_06580) at each end; it also encodes putative arsenate and arsenite resistance proteins (arsRHCB, GO593_06630-06645), toxin and antitoxin PemI (GO593_06620-06625), and conjugative transfer machinery (trbJKL, GO593_06605-06615). GIsul2 is embedded in a larger, 26.1-Kb genomic island (designated GI-19606-GO593_06565) predicted at 1,387,887-1,414,047 bp (Table S2), which is in turn located in a previously identified 37.0-Kb genomic island (1,382,910-1,420,005 bp, designated GI-19606-rph, Fig. 3) (Hamidian and Hall, 2017). GI-19606-rph is flanked by a 5-bp direct repeat sequence (5’-TTTTA-3’) and encodes 48 ORFs (GO593_06540-06790) with a ribonuclease gene rph (GO593_06540) at one end (1,383,026-1,383,742 bp) and a copy of ISAba11 at the other end (1,418,951-1,420,053 bp) (Fig. 3). This indicates an ISAba11-mediated large-scale DNA recombination. In addition, the predicted IS21 element is within a putative genomic island (3,154,748-3,173,457 bp, Table S2), suggesting another IS-mediated integration.

Table 2.

Predicted IS elements in the A. baumannii ATCC 19606 genome.

| Family | Start (bp) | End (bp) | Length (bp) | Inverted repeat length (bp) |

Transposase ORF start (bp) |

Transposase ORF end (bp) |

Strand | Length of Transposase ORF (bp) |

E-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IS91 | 1,402,296 | 1,404,594 | 2,299 | 18 | 1,402,762 | 1,404,464 | + | 1,703 | 5.70E-147 |

| IS701 | 1,418,951 | 1,420,053 | 1,103 | 14 | 1,419,008 | 1,420,036 | + | 1,029 | 4.30E-104 |

| IS110 | 1,851,680 | 1,853,941 | 2,262 | 49 | 1,852,136 | 1,853,998 | - | 1,863 | 7.20E-65 |

| IS21 | 3,155,852 | 3,158,578 | 2,727 | 18 | 3,155,831 | 3,158,168 | - | 2,339 | 3.70E-135 |

| IS701 | 3,973,359 | 3,974,459 | 1,101 | 13 | 3,973,415 | 3,974,443 | + | 1,029 | 4.30E-104 |

Figure 3.

Genomic islands containing ISAba11 and ISCR2 in A. baumannii ATCC 19606. Blue bars indicate the genes. The conserved regions cross Acinetobacter plasmids are highlighted in red.

Totally, five prophage regions were predicted in ATCC 19606 genome (Fig. 1). Four predicted genomic islands (Table S2) were located in or partially overlapped with three prophage regions (Table S3). Notably, the two large prophages (51.5 and 52.1 Kb) showed a high similarity with previously published Acinetobacter phage vB_AbaS_TRS1 (NC_031098) and YMC/09/02/B1251_ABA_BP (NC_019541), indicating that phage lysogenesis events possibly occurred in the evolutionary history of ATCC 19606.

Comparative analysis with other A. baumannii genomes

Comparative analysis of ATCC 19606 genome and another 98 fully sequenced A. baumannii genomes (genome size 3.4-4.2 Mb) identified 1,877 core proteins (>95% aa sequence identity), and an open pan genome containing 11,681 orthologs. A phylogenetic tree constructed from the core genome alignment clearly demonstrated the lineage divergence (Fig. 4). A relatively stable core-genome and an expanding pan-genome were discovered, indicating that A. baumannii strains diversify by integrating new genes. Most strains harbour 0 to 272 unique genes, whereas SDF contains 895 genes that exclusively exist in its own genome. Apart from the function unknown group, the majority of the abundant genes in the A. baumannii pan-genome are from Category L representing replication, recombination and repair (Fig. 4). This indicates the A. baumannii genomes underwent rearrangements caused by mobile genetic elements (e.g. plasmids, ISs, transposons, integrons, phages), which potentially resulted in rapid acquisition of antibiotic resistance. Very interestingly, the genome of ATCC 19606 showed a high similarity with that of strain ab736 (NZ_CP015121 and NZ_CP015122), indicating their close phylogenetic relationship. Compared to other strains, ATCC 19606 contains 32 unique genes, including transcriptional regulators, hypothetical genes, and prophage genes.

Figure 4.

Phylogenetic tree of A. baumannii strains. The ST52 strains (A. baumannii ATCC 19606 and ab736) are highlighted in violet, whereas IC I and ICII strains are highlighted in red and blue, respectively. The sequence type, GenBank accession, assembly version for each genome are denoted after the strain name.

The whole genome alignment with other 7 commonly used strains revealed that ATCC 19606 possesses totally 323-Kb unique sequence. Most of ATCC 19606 unique regions carry phage genes (e.g. GO593_11715, GO593_12890) or plasmid partition gene parA (GO593_18800). Interestingly, ATCC 19606 uniquely encodes a 2,888-aa RTX (repeat-in-toxin) protein (GO593_13010), containing multiple peptidase M10 serralysin C-terminal domains and a Ca2+-binding RTX toxin-related domain. This protein is secreted via Type I secretion systems (T1SS) and may contribute to A. baumannii virulence (Harding et al., 2017).

pMAC is a mobilisable plasmid with oriT located immediately in the upstream of mobA (GO593_19015), the product of which is predicted to be involved in DNA conjugative mobilisation (Dorsey et al., 2006). Blast search revealed a high sequence identity (>99%) of pMAC with A. baumannii ab736 plasmid p736 (9,539 bp, CP015122), Acinetobacter spp. M131 plasmid pM131-3 (9,541 bp, JX101646) and Dioscorea rotundata mitochondrial DNA fragment (9,541 bp, LC219381). Additionally, pMAC harbours a peroxide resistance gene ohr (GO593_19000) and its regulator ohrR (GO593_19005). These two genes seem well conserved in A. baumannii strains and other Gram-negative species, but present mostly on chromosomes.

Construction of a genome-scale metabolic model with protein crowding constraints

Significant metabolic changes could occur in A. baumannii during antibiotic treatment or infection; however, understanding of the complex metabolic responses was very limited (Bhuiyan et al., 2016; Boll et al., 2016; Han et al., 2019; Maifiah et al., 2017). Previously we constructed a GSMM iATCC19606 based on a draft assembly (Davenport et al., 2014) but it lacked periplasmic metabolites and reactions. Using the complete genome annotation and updated Biolog phenotype microarray results, a new GSMM of ATCC 19606 was constructed. Extensive manual curation was conducted to fill pathway gaps and minimise discrepancies between model predictions and experimental results. For instance, predictions using the initial model showed that ATCC 19606 was unable to grow with L-leucine as the sole carbon source, whereas both Biolog and growth test indicated that it could. Interrogation of BioCyc and KEGG databases identified an L-leucine degradation pathway via 2-oxoisovalerate dehydrogenase (GO593_16095-16110), isovaleryl-CoA:FAD oxidoreductase (GO593_14460), methylcrotonoyl-CoA carboxylase (GO593_03810, 03795, 14445 and 14455), and methylglutaconyl-CoA hydratase (GO593_03800 and 14450). Biolog test used NADH production as a universal reporter for nutrient utilisation; therefore, the positive Biolog result might indicate only substrate oxidation but not necessarily growth (Mauchline and Keevil, 1991). For example, a Biolog experiment showed that D-glucose was oxidised, but previous literature demonstrated that A. baumannii could not utilise D-glucose for growth (Nemec et al., 2011). We therefore curated the reactions accordingly. Furthermore, 1,551 constrains of intracellular protein crowding were incorporated so that each metabolic flux would not exceed its maximum capacity which was determined by kcat and enzyme abundance, and the total abundance of metabolic enzymes wound not exceed 25% (w/w) of cell dry weight (Materials and Methods).

Finally, the resulting model iATCC19606v2 involves 1,422 metabolites, 2,114 reactions and 1,009 genes, representing the largest GSMM to date for A. baumannii ATCC 19606. iATCC19606v2 contains a detailed representation of periplasmic metabolism, and includes 287 periplasmic metabolites and associated 560 reactions, which account for 20.2% and 26.5% of the total metabolites and reactions, respectively. iATCC19606v2 enabled accurate predictions of cross membrane transport, peptidoglycan and membrane lipids biogenesis. The complete genome significantly facilitated manual curation. For example, both previous GSMM models (iLP814 and iATCC19606) (Presta et al., 2017; Zhu et al., 2019) did not incorporate any lipid A phosphoethanolamine transferase reaction which is critical for the resistance to polymyxins in A. baumannii. In iATCC19606v2, two reactions (PETNT161pp and PETNT181pp) were included and they were catalysed by correctly annotated EptA (GO593_11890) and/or PmrC (GO593_02765). Additionally, we also reconstructed the biosynthesis pathways of virulence factors in the metabolic model (e.g. acinetobactin biosynthesis), which allows interrogation of the metabolic connections between virulence factor biosynthesis and bacterial growth. The model iATCC19606v2 correctly predicted the growth on 45 carbon and 34 nitrogen sources, and non-growth on 114 carbon and 51 nitrogen sources, achieving a higher accuracy (85.6%) compared to previous GSMMs iATCC19606 (84.3%) and iLP844 (84.8%) (Presta et al., 2017; Zhu et al., 2019) (Fig. 5 and Table S4). Simulation of single gene deletion showed that 102 and 143 genes were essential to bacterial growth on nutrient-rich (LB) and -limited media (M9 citrate), respectively. Comparison with the two transposon libraries of A. baumannii AB5075 and ATCC 17978 showed a high accuracy (87.6% and 82.1%, respectively) of gene essentiality prediction using model iATCC19606v2 (Table S5). Without limiting the uptake rate of any carbon source, iATCC19606v2 predicted a moderate growth rate of 1.24 (Fig. 6) and 2.44 h−1 in M9 + succinate and Mueller-Hinton media, respectively, whereas the previous model iATCC19606 predicted an unrealistically high growth rate of 3.52 (Fig. 6) and 39.99 h−1, respectively. With iATCC19606v2, the dynamics of utilising amino acids and dipeptides in Mueller-Hinton media could also be predicted (Fig. S3). Overall, the constructed GSMM represents a significant improvement on previous version and it provides a valuable systems tool to investigate the mechanisms of antimicrobial activity and resistance in ATCC 19606.

Figure 5.

Discrepancies between Biolog results and model prediction. Blue lattice indicates valid growth and white lattice indicates no growth.

Figure 6.

Predicted specific growth rates along with varying succinate uptake rates using models iATCC19606 (green) and iATCC19606v2 (red), respectively.

Discussion

A. baumannii has emerged as one of the most problematic Gram-negative pathogens owing to its ability to develop resistance to almost all available antibiotics (Dijkshoorn et al., 2007). A. baumannii ATCC 19606 has been widely employed as a type strain of A. baumannii and shows a unique mechanism of resistance to the last-line polymyxins by the loss of LPS (de Breij et al., 2009; Gaddy et al., 2012; Hamidian and Hall, 2017; Harris et al., 2013; Jin et al., 2011; Krizova et al., 2013; Luo et al., 2015; Moffatt et al., 2010; Pachon-Ibanez et al., 2010; Shibuya et al., 2010). However, the functional genomics studies are hampered by the lack of a precise genomic atlas. Here, we report the first complete genome of ATCC 19606 by PacBio sequencing and de novo assembly (Fig. 1). The 3.99 Mb genome encodes a range of functional pathways enabling A. baumannii to utilise a variety of nutrients to grow. ATCC 19606 is susceptible to most antibiotics due to the lack of MDR genes. However, it contains the genes associated with the resistance to sulphonamides, several β-lactams and streptomycin (Fig. 2). Furthermore, a number of multidrug resistance efflux pump genes were identified in ATCC 19606 genome, including (i) the RND family: tolC, adeAB, adeFGH and adeIJK; (ii) the small multidrug resistance (SMR) family efflux pump: abeS; (iii) the multidrug and toxic compound extrusion (MATE) family: abeM; and (iv) the major facilitator superfamily (MFS), tetA (GO593_04390), mdfA (GO593_04525) and amvA (GO593_18025). In addition, the ABC transporters associated with antimicrobial resistance were also discovered, including emrAB (GO593_16655-16650), emrKY (GO593_10720 and GO593_16835), and macB (GO593_09130). Many of these transporters were correlated with resistance to a range of antibiotics (e.g. aminoglycosides, β-lactams, fluoroquinolones, tetracycline, tigecycline) in other A. baumannii strains (Coyne et al., 2010; Damier-Piolle et al., 2008; Magnet et al., 2001; Marchand et al., 2004; Rajamohan et al., 2010; Srinivasan et al., 2009; Su et al., 2005); however, ATCC 19606 is susceptible to most of the antibiotics listed above. This suggests that these transporters might be less active or at a lower expression level compared to their homologs in other MDR strains, and only constitute the intrinsic resistome of ATCC 19606. Analysis of the genome content showed the presence of multiple IS elements, genomic islands and integration of prophages (Fig. 1, Tables 2, S2 and S3). Comparative analysis with the gapless genomes of the other 7 commonly used A. baumannii strains (including those representing IC I-III) confirmed that the ATCC 19606 genome is distinguishable by the integration of prophage sequences (Table S3).

Thus far, totally five draft genomes are publicly available for A. baumannii ATCC 19606, with 13-118 contigs and the total length ranging from 3.93 to 4.02 Mb. Systematic comparisons with our complete genome identified a range of assembly errors in previous assemblies (Fig. S1A) which were potentially due to the low performance in assembling the repeat regions from Illumina short reads (Treangen and Salzberg, 2011). These errors resulted in mis-annotation of genomic content (Fig. S1B) and incorrect interpretation of functional genomics results (Fig. S2). For instance, GO593_16905 encodes a filamentous hemagglutinin N-terminal domain-containing protein, but was wrongly annotated as a pseudogene in a previous assembly (HMPREF0010_07340 at 544,546-550,732 bp of NZ_GG704572). GO593_16905 was expressed in the control at 1 h (counts per million = 442.2) but significantly downregulated after 2 mg/L colistin treatment for 1 h (FC = 5.6, FDR-adjusted P < 0.01) (Table S6). Therefore, an accurate and complete genome sequence of ATCC 19606 is much needed for functional genomic studies on A. baumannii.

A recent study identified two genes (eptA and pmrC) related to polymyxin resistance in A. baumannii clinical strains; both encoded lipid A phosphoethanolamine transferase and showed a protein sequence similarity of 93% with each other (Deveson Lucas et al., 2018). eptA is regulated by H-NS while pmrC is regulated by PmrA (Deveson Lucas et al., 2018). By searching our ATCC 19606 genome, we discovered two genes GO593_11890 and GO593_02765 showing 99.78% and 94.56% protein sequence similarity with the reported EptA and PmrC, respectively. In our ATCC 19606 genome, pmrC and pmrAB (GO593_02755-02760) are in the same operon as in many other A. baumannii strains; whereas eptA is located in the downstream of a predicted 52.1-Kb prophage region (2,438,683-2,490,808 bp, Table S3). Notably, the full-length eptA was also present in previous assemblies Acin_baum_CIP_70_34T_V1 and ASM281117v1, but absent in ASM16229v1, ASM61470v1 and ASM73714v1, potentially due to severe fragmentation of these assemblies. Further analysis showed that eptA also exists in MDR-TJ (IC II) and OIFC137 (IC III), but not in AB5075-UW (IC I), AYE (IC II), ATCC 17978 (ST437) or SDF (ST17).

A. baumannii ATCC 19606 can acquire high-level resistance to polymyxins by chromosomally integrating the ISAba11 element or point mutation at the lpxACD loci (Moffatt et al., 2011). These genes encode the enzymes catalysing the first three committed steps of lipid A biosynthesis. Insertional inactivation of lpxACD abolishes the lipid A synthesis and leads to LPS loss, as well as significant remodelling of the OM (Moffatt et al., 2011). Three copies of ISAba11 elements were identified in ATCC 19606 based on the genomic DNA digestion and southern blotting (Moffatt et al., 2011). Our genomic analysis in the present study demonstrated that only two copies of ISAba11 present in ATCC 19606 genome (Table 2). It is noteworthy that only one copy of ISAba11 was embedded at the end of a 36.1-Kb genomic island (GI-19606-rph) with ISCR2 located in the middle, suggesting the occurrence of large-scale genetic transfer events mediated by both IS elements (Fig. 3). Additionally, a previously reported genomic island GIsul2 was embedded in GI-19606-rph. The ATCC 17978 plasmid pAB3 (CP012005) showed high sequence identity with GIsul2 of the ATCC 19606 chromosome (Fig. 3) (Nigro and Hall, 2011). pAB3 also harbours a copy of ISAba11 element downstream of GIsul2 (Nigro and Hall, 2011). The regions flanking GIsul2 showed high sequence identity (>95%) with A. defluvii WCHA30 plasmid pOXA58_010030 (CP029396, coverage 68%), A. johnsonii XBB1 plasmid pXBB1-9 (CP010351, coverage 56%) and A. lwoffii ED23-35 plasmid pALWED1.1 (KX426227, coverage 49%), suggesting an integration event of the plasmid to the chromosome of ATCC 19606 possibly mediated by ISCS2 and/or ISAba11 (Fig. 3). IS elements and transposons play important roles in bacterial evolution, including promoting horizontal transfer of antibiotic resistance genes and chromosome rearrangements (Partridge et al., 2018). AraR type genomic islands were previously identified in A. baumannii genomes, including AraR1 from AYE, AbaR2 from ACICU, and AbaR3 from AB0057 (Post et al., 2010). All reported AbaR sequences inserted into the comM gene in the chromosome. The ATCC 19606 chromosome possesses an intact comM (GO593_07620), suggesting the absence of the AraR-type genomic island.

Previous multi-omics studies revealed complex interplay of multiple metabolic pathways in A. baumannii under antibiotic treatments (Han et al., 2019; Maifiah et al., 2017). Two GSMMs (iLP814 and iATCC19606) were constructed previously for A. baumannii ATCC 19606 to analyse metabolic changes in response to polymyxin treatment (Presta et al., 2017; Zhu et al., 2019). However, both GSMMs were constructed using a draft assembly (Davenport et al., 2014) and model iATCC19606 lacks representation of periplasmic metabolites and reactions. Using the complete genome annotation here, we constructed a comprehensive GSMM model iATCC19606v2, and incorporated an extra periplasm compartment where 560 reactions (99 periplasmic reactions, 300 cross-IM reactions and 161 cross-OM reactions) were included. The complete genome significantly helped manual curation. For example, in model iATCC19606v2 we incorporated two specific lipid A phosphoethanolamine transferase reactions (PETNT161pp and PETNT181pp) which are catalysed by EptA and/or PmrC. Conventional FBA allows the prediction of growth rate based solely on reaction stoichiometry and directionality; therefore, growth rate predictions obtained by FBA with unlimited nutrient uptake are likely to be unrealistically high in many cases and manual adjustment of nutrient uptake constraints was often required. Incorporation of the additional protein crowding constraints in model iATCC19606v2 limited the metabolic capabilities in a realistic range, thereby allowing relatively accurate predictions of bacterial growth and nutrient utilisation (Figs. 6 and S3). Biolog nutrient utilisation tests with 95 nitrogen sources were employed for manual curation; growth prediction using iATCC19606v2 achieved a high accuracy (86.0%). Hence, the model iATCC19606v2 is a valuable computational tool for analysis of multi-omics data.

A complete genome sequence and accurate annotation are of utmost importance for functional genomic analyses. To the best of our knowledge, this study reports the first complete genome sequence of A. baumannii ATCC 19606 and our latest GSMM will significantly benefit systems pharmacological investigations on A. baumannii.

Supplementary Material

Table S1. Predicted COG classifications.

Table S2. Predicted genomic islands.

Table S3. Predicted prophages in ATCC 19606 genome.

Table S4. Predicted growth on Biolog nutrients using model iATCC19606v2.

Table S5. Predicted essential genes using model iATCC19606v2.

Table S6. Identified DEGs under 2 mg/L colistin treatment for 1 h compared to untreated control at 1 h with the complete genome as reference.

Figure S1. Differences between the complete genome and previous draft assemblies of A. baumannii ATCC 19606. (A) Sequence alignment of our complete genome and five previous draft assemblies (ASM61470v1, ASM16229v1, Acin_baum_CIP_70_34T_V1, ASM73714v1 and ASM2811117v1). The matching regions are represented as connected blocks. (B) Comparison of predicted ORFs in our complete genome (ASM975968v1) and previous draft assemblies. ASM61470v1 was not involved due to the absence of annotation.

Figure S2. Volcano plot showing significant differences in DEG identification due to using different reference genomes. The grey and black dots indicate the DEGs identified with ASM16229v1 and our complete genome as reference, respectively. The light green and orange dots indicate the DEGs uniquely identified using ASM16229v1 and our complete genome (ASM975968v1), respectively, as the references. Specifically, the DEGs uniquely identified owing to annotation discrepancies are highlighted in dark green (ASM16229v1) and red (ASM975968v1).

Figure S3. Predicted biomass accumulation and substrate uptake using dynamic flux balance analysis with iATCC19606 (A) and iATCC19606v2 (B).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Monash Micromon (Clayton, Australia) for Sanger sequencing.

Funding

J.L and T.V. are supported by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) project grant (APP1104581) and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (R01 AI132154). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases or the National Institutes of Health. T.V. is an Australian NHMRC Career Development Research Fellow and J.L. is an Australian NHMRC Principal Research Fellow.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

References

- Adadi R, Volkmer B, Milo R, Heinemann M, Shlomi T, 2012. Prediction of microbial growth rate versus biomass yield by a metabolic network with kinetic parameters. PLoS Comput. Biol 8, e1002575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antipov D, Hartwick N, Shen M, Raiko M, Lapidus A, Pevzner PA, 2016. plasmidSPAdes: assembling plasmids from whole genome sequencing data. Bioinformatics 32, 3380–3387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ardui S, Ameur A, Vermeesch JR, Hestand MS, 2018. Single molecule real-time (SMRT) sequencing comes of age: applications and utilities for medical diagnostics. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, 2159–2168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertelli C, Laird MR, Williams KP, Simon Fraser University Research Computing, Lau G, Hoad BY, Winsor G, Brinkman GL, L. FS, 2017. IslandViewer 4: expanded prediction of genomic islands for larger-scale datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, W30–W35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhuiyan MS, Ellett F, Murray GL, Kostoulias X, Cerqueira GM, Schulze KE, Mahamad Maifiah MH, Li J, Creek DJ, Lieschke GJ, Peleg AY, 2016. Acinetobacter baumannii phenylacetic acid metabolism influences infection outcome through a direct effect on neutrophil chemotaxis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 113, 9599–9604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boll JM, Crofts AA, Peters K, Cattoir V, Vollmer W, Davies BW, Trent MS, 2016. A penicillin-binding protein inhibits selection of colistin-resistant, lipooligosaccharide-deficient Acinetobacter baumannii. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 113, E6228–e6237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron DL, Schroder J, Penington JS, Do H, Molania R, Dobrovic A, Speed TP, Papenfuss AT, 2017. GRIDSS: sensitive and specific genomic rearrangement detection using positional de Bruijn graph assembly. Genome Res. 27, 2050–2060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical & Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI), 2018. M07. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically. CLSI, Wayne, PA, p. 112. [Google Scholar]

- Coyne S, Rosenfeld N, Lambert T, Courvalin P, Perichon B, 2010. Overexpression of resistance-nodulation-cell division pump AdeFGH confers multidrug resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 54, 4389–4393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damier-Piolle L, Magnet S, Bremont S, Lambert T, Courvalin P, 2008. AdeIJK, a resistance-nodulation-cell division pump effluxing multiple antibiotics in Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 52, 557–562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darling AE, Mau B, Perna NT, 2010. progressiveMauve: multiple genome alignment with gene gain, loss and rearrangement. PLoS One 5, e11147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davenport KW, Daligault HE, Minogue TD, Bruce DC, Chain PS, Coyne SR, Jaissle JG, Koroleva GI, Ladner JT, Li PE, Palacios GF, Scholz MB, Teshima H, Johnson SL, 2014. Draft genome assembly of Acinetobacter baumannii ATCC 19606. Genome Announc. 2, e00832–00814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Breij A, Gaddy J, van der Meer J, Koning R, Koster A, van den Broek P, Actis L, Nibbering P, Dijkshoorn L, 2009. CsuA/BABCDE-dependent pili are not involved in the adherence of Acinetobacter baumannii ATCC19606T to human airway epithelial cells and their inflammatory response. Res. Microbiol 160, 213–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deveson Lucas D, Crane B, Wright A, Han ML, Moffatt J, Bulach D, Gladman SL, Powell D, Aranda J, Seemann T, Machado D, Pacheco T, Marques T, Viveiros M, Nation R, Li J, Harper M, Boyce JD, 2018. Emergence of high-level colistin resistance in an Acinetobacter baumannii clinical isolate mediated by inactivation of the global regulator H-NS. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 62, e02442–02417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diancourt L, Passet V, Nemec A, Dijkshoorn L, Brisse S, 2010. The population structure of Acinetobacter baumannii: expanding multiresistant clones from an ancestral susceptible genetic pool. PLoS One 5, e10034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dijkshoorn L, Nemec A, Seifert H, 2007. An increasing threat in hospitals: multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Nat. Rev. Microbiol 5, 939–951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorsey CW, Tomaras AP, Actis LA, 2006. Sequence and organization of pMAC, an Acinetobacter baumannii plasmid harboring genes involved in organic peroxide resistance. Plasmid 56, 112–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eijkelkamp BA, Stroeher UH, Hassan KA, Paulsen IT, Brown MH, 2014. Comparative analysis of surface-exposed virulence factors of Acinetobacter baumannii. BMC Genomics 15, 1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaddy JA, Arivett BA, McConnell MJ, Lopez-Rojas R, Pachon J, Actis LA, 2012. Role of acinetobactin-mediated iron acquisition functions in the interaction of Acinetobacter baumannii strain ATCC 19606T with human lung epithelial cells, Galleria mellonella caterpillars, and mice. Infect. Immun 80, 1015–1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher LA, Ramage E, Weiss EJ, Radey M, Hayden HS, Held KG, Huse HK, Zurawski DV, Brittnacher MJ, Manoil C, 2015. Resources for genetic and genomic analysis of emerging pathogen Acinetobacter baumannii. J. Bacteriol 197, 2027–2035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannouli M, Antunes LC, Marchetti V, Triassi M, Visca P, Zarrilli R, 2013. Virulence-related traits of epidemic Acinetobacter baumannii strains belonging to the international clonal lineages I-III and to the emerging genotypes ST25 and ST78. BMC Infect. Dis 13, 282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin S, McPherson JD, McCombie WR, 2016. Coming of age: ten years of next-generation sequencing technologies. Nat. Rev. Genet 17, 333–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamidian M, Hall RM, 2017. Acinetobacter baumannii ATCC 19606 carries GIsul2 in a genomic island located in the chromosome. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 61, e01991–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han ML, Liu X, Velkov T, Lin YW, Zhu Y, Creek DJ, Barlow CK, Yu HH, Zhou Z, Zhang J, Li J, 2019. Comparative metabolomics reveals key pathways associated with the synergistic killing of colistin and sulbactam combination against multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Front. Pharmacol 10, 754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding CM, Hennon SW, Feldman MF, 2018. Uncovering the mechanisms of Acinetobacter baumannii virulence. Nat. Rev. Microbiol 16, 91–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding CM, Pulido MR, Di Venanzio G, Kinsella RL, Webb AI, Scott NE, Pachon J, Feldman MF, 2017. Pathogenic Acinetobacter species have a functional type I secretion system and contact-dependent inhibition systems. J. Biol. Chem 292, 9075–9087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmer CJ, Hamidian M, Hall RM, 2017. pIP40a, a type 1 IncC plasmid from 1969 carries the integrative element GIsul2 and a novel class II mercury resistance transposon. Plasmid 92, 17–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris G, Kuo Lee R, Lam CK, Kanzaki G, Patel GB, Xu HH, Chen W, 2013. A mouse model of Acinetobacter baumannii-associated pneumonia using a clinically isolated hypervirulent strain. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 57, 3601–3613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison P, Seemann T, 2009. From high-throughput sequencing read alignments to confident, biologically relevant conclusions with Nesoni. http://www.vicbioinformatics.com/nesoni_ba2009_poster.pdf (accessed 29 Dec 2019).

- Heirendt L, Arreckx S, Pfau T, Mendoza SN, Richelle A, Heinken A, Haraldsdottir HS, Wachowiak J, Keating SM, Vlasov V, Magnusdottir S, Ng CY, Preciat G, Zagare A, Chan SHJ, Aurich MK, Clancy CM, Modamio J, Sauls JT, Noronha A, Bordbar A, Cousins B, El Assal DC, Valcarcel LV, Apaolaza I, Ghaderi S, Ahookhosh M, Ben Guebila M, Kostromins A, Sompairac N, Le HM, Ma D, Sun Y, Wang L, Yurkovich JT, Oliveira MAP, Vuong PT, El Assal LP, Kuperstein I, Zinovyev A, Hinton HS, Bryant WA, Aragon Artacho FJ, Planes FJ, Stalidzans E, Maass A, Vempala S, Hucka M, Saunders MA, Maranas CD, Lewis NE, Sauter T, Palsson BO, Thiele I, Fleming RMT, 2019. Creation and analysis of biochemical constraint-based models using the COBRA Toolbox v.3.0. Nat. Protoc 14, 639–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry R, Crane B, Powell D, Deveson Lucas D, Li Z, Aranda J, Harrison P, Nation RL, Adler B, Harper M, Boyce JD, Li J, 2015. The transcriptomic response of Acinetobacter baumannii to colistin and doripenem alone and in combination in an in vitro pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics model. J. Antimicrob. Chemother 70, 1303–1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry R, Vithanage N, Harrison P, Seemann T, Coutts S, Moffatt JH, Nation RL, Li J, Harper M, Adler B, Boyce JD, 2012. Colistin-resistant, lipopolysaccharide-deficient Acinetobacter baumannii responds to lipopolysaccharide loss through increased expression of genes involved in the synthesis and transport of lipoproteins, phospholipids, and poly-β-1,6-N-acetylglucosamine. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 56, 59–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hugh R, Reese R, 1967. Designation of the type strain for Bacterium anitratum Schaub and Hauber 1948. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol 17, 245–254. [Google Scholar]

- Jia B, Raphenya AR, Alcock B, Waglechner N, Guo P, Tsang KK, Lago BA, Dave BM, Pereira S, Sharma AN, Doshi S, Courtot M, Lo R, Williams LE, Frye JG, Elsayegh T, Sardar D, Westman EL, Pawlowski AC, Johnson TA, Brinkman FS, Wright GD, McArthur AG, 2017. CARD 2017: expansion and model-centric curation of the comprehensive antibiotic resistance database. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, D566–D573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin JS, Kwon SO, Moon DC, Gurung M, Lee JH, Kim SI, Lee JC, 2011. Acinetobacter baumannii secretes cytotoxic outer membrane protein A via outer membrane vesicles. PLoS One 6, e17027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karah N, Jolley KA, Hall RM, Uhlin BE, 2017. Database for the ampC alleles in Acinetobacter baumannii. PLoS One 12, e0176695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krizova L, Poirel L, Nordmann P, Nemec A, 2013. TEM-1 β-lactamase as a source of resistance to sulbactam in clinical strains of Acinetobacter baumannii. J. Antimicrob. Chemother 68, 2786–2791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letunic I, Bork P, 2019. Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL) v4: recent updates and new developments. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, W256–W259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li GW, Burkhardt D, Gross C, Weissman JS, 2014. Quantifying absolute protein synthesis rates reveals principles underlying allocation of cellular resources. Cell 157, 624–635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao Y, Smyth GK, Shi W, 2013. The Subread aligner: fast, accurate and scalable read mapping by seed-and-vote. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, e108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B, Zheng D, Jin Q, Chen L, Yang J, 2019. VFDB 2019: a comparative pathogenomic platform with an interactive web interface. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D687–D692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo LM, Wu LJ, Xiao YL, Zhao D, Chen ZX, Kang M, Zhang Q, Xie Y, 2015. Enhancing pili assembly and biofilm formation in Acinetobacter baumannii ATCC19606 using non-native acyl-homoserine lactones. BMC Microbiol. 15, 62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machado D, Andrejev S, Tramontano M, Patil KR, 2018. Fast automated reconstruction of genome-scale metabolic models for microbial species and communities. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, 7542–7553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnet S, Courvalin P, Lambert T, 2001. Resistance-nodulation-cell division-type efflux pump involved in aminoglycoside resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii strain BM4454. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45, 3375–3380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maifiah MH, Cheah SE, Johnson MD, Han ML, Boyce JD, Thamlikitkul V, Forrest A, Kaye KS, Hertzog P, Purcell AW, Song J, Velkov T, Creek DJ, Li J, 2016. Global metabolic analyses identify key differences in metabolite levels between polymyxin-susceptible and polymyxin-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Sci. Rep 6, 22287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maifiah MH, Creek DJ, Nation RL, Forrest A, Tsuji BT, Velkov T, Li J, 2017. Untargeted metabolomics analysis reveals key pathways responsible for the synergistic killing of colistin and doripenem combination against Acinetobacter baumannii. Sci. Rep 7, 45527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchand I, Damier-Piolle L, Courvalin P, Lambert T, 2004. Expression of the RND-type efflux pump AdeABC in Acinetobacter baumannii is regulated by the AdeRS two-component system. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 48, 3298–3304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauchline WS, Keevil CW, 1991. Development of the BIOLOG substrate utilization system for identification of Legionella spp. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 57, 3345–3349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffatt JH, Harper M, Adler B, Nation RL, Li J, Boyce JD, 2011. Insertion sequence ISAba11 is involved in colistin resistance and loss of lipopolysaccharide in Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 55, 3022–3024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffatt JH, Harper M, Harrison P, Hale JD, Vinogradov E, Seemann T, Henry R, Crane B, St Michael F, Cox AD, Adler B, Nation RL, Li J, Boyce JD, 2010. Colistin resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii is mediated by complete loss of lipopolysaccharide production. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54, 4971–4977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemec A, Krizova L, Maixnerova M, van der Reijden TJ, Deschaght P, Passet V, Vaneechoutte M, Brisse S, Dijkshoorn L, 2011. Genotypic and phenotypic characterization of the Acinetobacter calcoaceticus-Acinetobacter baumannii complex with the proposal of Acinetobacter pittii sp. nov. (formerly Acinetobacter genomic species 3) and Acinetobacter nosocomialis sp. nov. (formerly Acinetobacter genomic species 13TU). Res. Microbiol 162, 393–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigro SJ, Hall RM, 2011. GIsul2, a genomic island carrying the sul2 sulphonamide resistance gene and the small mobile element CR2 found in the Enterobacter cloacae subspecies cloacae type strain ATCC 13047 from 1890, Shigella flexneri ATCC 700930 from 1954 and Acinetobacter baumannii ATCC 17978 from 1951. J. Antimicrob. Chemother 66, 2175–2176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien EJ, Lerman JA, Chang RL, Hyduke DR, Palsson BO, 2013. Genome-scale models of metabolism and gene expression extend and refine growth phenotype prediction. Mol. Syst. Biol 9, 693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachon-Ibanez ME, Docobo-Perez F, Lopez-Rojas R, Dominguez-Herrera J, Jimenez-Mejias ME, Garcia-Curiel A, Pichardo C, Jimenez L, Pachon J, 2010. Efficacy of rifampin and its combinations with imipenem, sulbactam, and colistin in experimental models of infection caused by imipenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 54, 1165–1172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page AJ, Cummins CA, Hunt M, Wong VK, Reuter S, Holden MT, Fookes M, Falush D, Keane JA, Parkhill J, 2015. Roary: rapid large-scale prokaryote pan genome analysis. Bioinformatics 31, 3691–3693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Partridge SR, Kwong SM, Firth N, Jensen SO, 2018. Mobile genetic elements associated with antimicrobial resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 31, e00088–00017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perichon B, Goussard S, Walewski V, Krizova L, Cerqueira G, Murphy C, Feldgarden M, Wortman J, Clermont D, Nemec A, Courvalin P, 2014. Identification of 50 class D β-lactamases and 65 Acinetobacter-derived cephalosporinases in Acinetobacter spp. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 58, 936–949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poirel L, Mugnier PD, Toleman MA, Walsh TR, Rapoport MJ, Petroni A, Nordmann P, 2009. ISCR2, another vehicle for blaVEB gene acquisition. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 53, 4940–4943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Post V, White PA, Hall RM, 2010. Evolution of AbaR-type genomic resistance islands in multiply antibiotic-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. J. Antimicrob. Chemother 65, 1162–1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Presta L, Bosi E, Mansouri L, Dijkshoorn L, Fani R, Fondi M, 2017. Constraint-based modeling identifies new putative targets to fight colistin-resistant A. baumannii infections. Sci. Rep 7, 3706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajamohan G, Srinivasan VB, Gebreyes WA, 2010. Molecular and functional characterization of a novel efflux pump, AmvA, mediating antimicrobial and disinfectant resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii. J. Antimicrob. Chemother 65, 1919–1925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibuya M, Nishimura K, Yasuyama N, Ebizuka Y, 2010. Identification and characterization of glycosyltransferases involved in the biosynthesis of soyasaponin I in Glycine max. FEBS Lett. 584, 2258–2264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan VB, Rajamohan G, Gebreyes WA, 2009. Role of AbeS, a novel efflux pump of the SMR family of transporters, in resistance to antimicrobial agents in Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 53, 5312–5316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis A, 2014. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 30, 1312–1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su XZ, Chen J, Mizushima T, Kuroda T, Tsuchiya T, 2005. AbeM, an H+-coupled Acinetobacter baumannii multidrug efflux pump belonging to the MATE family of transporters. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49, 4362–4364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treangen TJ, Salzberg SL, 2011. Repetitive DNA and next-generation sequencing: computational challenges and solutions. Nat. Rev. Genet. 13, 36–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dijk EL, Jaszczyszyn Y, Naquin D, Thermes C, 2018. The third revolution in sequencing technology. Trends Genet. 34, 666–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilacoba E, Almuzara M, Gulone L, Traglia GM, Figueroa SA, Sly G, Fernandez A, Centron D, Ramirez MS, 2013. Emergence and spread of plasmid-borne tet(B)::ISCR2 in minocycline-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57, 651–654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang N, Ozer EA, Mandel MJ, Hauser AR, 2014. Genome-wide identification of Acinetobacter baumannii genes necessary for persistence in the lung. mBio 5, e01163–01114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization, 2017. Global priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria to guide research, discovery, and development of new antibiotics. http://www.who.int/medicines/publications/global-priority-list-antibiotic-resistant-bacteria/en/ (accessed 29 Dec 2019).

- Xie Z, Tang H, 2017. ISEScan: automated identification of insertion sequence elements in prokaryotic genomes. Bioinformatics 33, 3340–3347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Wang C, Zhang G, Tian J, Liu Y, Shen X, Feng J, 2017. ISCR2 is associated with the dissemination of multiple resistance genes among Vibrio spp. and Pseudoalteromonas spp. isolated from farmed fish. Arch. Microbiol 199, 891–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y, Czauderna T, Zhao J, Klapperstueck M, Maifiah MHM, Han ML, Lu J, Sommer B, Velkov T, Lithgow T, Song J, Schreiber F, Li J, 2018. Genome-scale metabolic modeling of responses to polymyxins in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Gigascience 7, giy021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y, Zhao J, Maifiah MHM, Velkov T, Schreiber F, Li J, 2019. Metabolic responses to polymyxin treatment in Acinetobacter baumannii ATCC 19606: integrating transcriptomics and metabolomics with genome-scale metabolic modeling. mSystems 4, e00157–00118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Predicted COG classifications.

Table S2. Predicted genomic islands.

Table S3. Predicted prophages in ATCC 19606 genome.

Table S4. Predicted growth on Biolog nutrients using model iATCC19606v2.

Table S5. Predicted essential genes using model iATCC19606v2.

Table S6. Identified DEGs under 2 mg/L colistin treatment for 1 h compared to untreated control at 1 h with the complete genome as reference.

Figure S1. Differences between the complete genome and previous draft assemblies of A. baumannii ATCC 19606. (A) Sequence alignment of our complete genome and five previous draft assemblies (ASM61470v1, ASM16229v1, Acin_baum_CIP_70_34T_V1, ASM73714v1 and ASM2811117v1). The matching regions are represented as connected blocks. (B) Comparison of predicted ORFs in our complete genome (ASM975968v1) and previous draft assemblies. ASM61470v1 was not involved due to the absence of annotation.

Figure S2. Volcano plot showing significant differences in DEG identification due to using different reference genomes. The grey and black dots indicate the DEGs identified with ASM16229v1 and our complete genome as reference, respectively. The light green and orange dots indicate the DEGs uniquely identified using ASM16229v1 and our complete genome (ASM975968v1), respectively, as the references. Specifically, the DEGs uniquely identified owing to annotation discrepancies are highlighted in dark green (ASM16229v1) and red (ASM975968v1).

Figure S3. Predicted biomass accumulation and substrate uptake using dynamic flux balance analysis with iATCC19606 (A) and iATCC19606v2 (B).