Abstract

Following infection with certain strains of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC), particularly enterohemorrhagic ones, patients are at elevated risk for developing life-threatening extraintestinal complications, such as acute renal failure. Hence, these bacteria represent a public health concern in both developed and developing countries. Shiga toxins (Stxs) expressed by STEC are highly cytotoxic class II ribosome-inactivating proteins and primary virulence factors responsible for major clinical signs of Stx-mediated pathogenesis, including bloody diarrhea, hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS), and neurological complications. Ruminant animals are thought to serve as critical environmental reservoirs of Stx-producing Escherichia coli (STEC), but other emerging or arising reservoirs of the toxin-producing bacteria have been overlooked. In particular, a number of new animal species from wildlife and aquaculture industries have recently been identified as unexpected reservoir or spillover hosts of STEC. Here, we summarize recent findings about reservoirs of STEC and review outbreaks of these bacteria both within and outside the United States. A better understanding of environmental transmission to humans will facilitate the development of novel strategies for preventing zoonotic STEC infection.

Keywords: Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli, Shiga toxin, STEC reservoir, HUS, environmental transmission

Introduction

Escherichia coli is a component of the normal flora in the human gut, but some strains are pathogenic. Based on its pathotypes, intestinal pathogenic E. coli can be classified into six groups: Shiga toxin (Stx)-producing [STEC, also referred to as verocytotoxin-producing (VTEC) or enterohemorrhagic (EHEC)], enterotoxigenic (ETEC), enteropathogenic (EPEC), enteroaggregative (EAEC), enteroinvasive (EIEC), and diffusely adherent (DAEC) (Kaper et al., 2004). Among those, STEC tends to be a clonal group characterized by somatic (O) antigen, and more than 200 serotypes of E. coli have been known to produce Stxs based on their molecular and genetic features. In addition, a new classification scheme of five seropathotypes (A–E) based on virulence, serological and genetic features has been suggested due to the various symptoms and severity of clinical STEC infections (Frankel et al., 1998; Nataro and Kaper, 1998; Boerlin et al., 1999; Karmali et al., 2003). However, a recent massive outbreak in Germany raised questions about the efficacy of this categorization because the strain involved was not classified as type A or B based on its genetics (specifically, it was negative for the LEE Island). Hence, in this review, we summarize outbreaks and STEC isolates by serotype, not seropathotype, based on surveillance reports.

Stxs are a family of bacterial exotoxins expressed by Shigella dysenteriae serotype 1 and STEC (Fraser et al., 1994; Sandvig, 2001). These toxins are primary virulence factors responsible for bloody diarrheal disease that can progress to life-threatening systemic sequelae, such as an acute renal failure syndrome (also known as hemolytic uremic syndrome, HUS), as well as central nervous system (CNS) abnormalities (Tarr et al., 2005; Lee et al., 2016; Lee and Tesh, 2019). The toxins produced by STEC are classified as type 1 (Stx1) and type 2 (Stx2), and several Stx1/Stx2 subtypes and variants have been reported based on the receptor preference and toxin potency (Scheutz et al., 2012; Melton-Celsa, 2014). And among those, Stx2, which is more potent than Stx1, causes clinically severe weight loss and renal injury (Lentz et al., 2011; Pradhan et al., 2016).

Multiple studies have focused on revealing the source and transmission route of STEC infections in humans and the food chain (Erickson and Doyle, 2007; Kintz et al., 2017). Animals are undoubtedly the most important carriers of STEC, as these strains have been isolated from a wide variety of domestic and human-associated animal species (Persad and LeJeune, 2014; Espinosa et al., 2018). Several lines of evidence have confirmed zoonotic human infections caused by contact with companion and domestic animals (Chalmers et al., 1997; Luna et al., 2018). In addition, work in recent decades has emphasized the importance of wildlife surveillance, as a large proportion of emerging zoonotic pathogens are of wildlife origin (Jones et al., 2013), and increasing numbers of wild animals have been shown to be potential STEC reservoirs (Espinosa et al., 2018). Although the need for the One Health approach has been continuously emphasized in STEC research, surveillance studies have generally been limited to domestic animals (Garcia et al., 2010). However, a recent STEC surveillance study revealed that more distantly related fields, such as aquaculture, should be included as important areas of interest and monitored accordingly. In this review, we update the list of animal species recently reported as STEC reservoirs. In so doing, our goal is to emphasize the importance of applying the interdisciplinary One Health approach in surveillance systems by strengthening multi-sectorial collaboration between agriculture, aquaculture, and wildlife science, as well as to provide a broad perspective on industrial fields relevant to food production.

STEC Global Outbreaks and Clinical Isolates

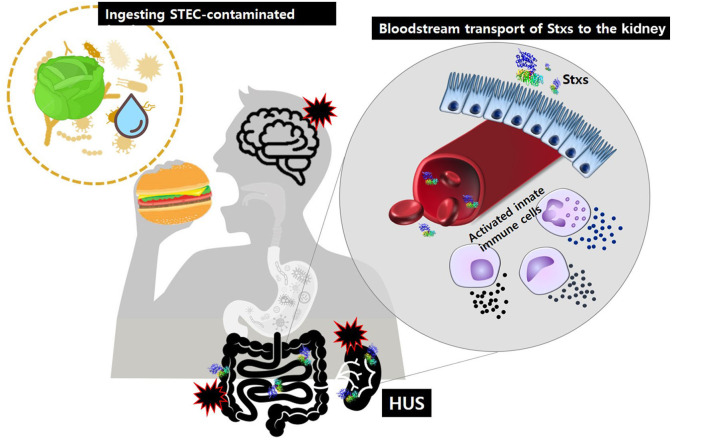

Historically, Stxs and verotoxin were studied separately. Stxs was discovered by Kiyoshi Shiga in 1898 as a factor involved in bacterial dysentery caused by S. dysenteriae serotype I (Kaper and O'Brien, 2014). Independently, in 1977, verotoxin was discovered by Konowalchuck in diarrheagenic E. coli strains (Konowalchuk et al., 1977). In 1983, Johnson et al. confirmed that two toxins belonged to the same family (Johnson et al., 1983), and they began to be considered together in studies of the first STEC outbreak strains from 1982. Shiga toxin-producing bacteria, including STEC and S. dysenteriae serotype 1, are agents of hemorrhagic colitis, which can progress to potentially lethal complications, such as bloody diarrhea-associated HUS (D + HUS) with acute renal dysfunction (Figure 1) and CNS disorders, such as seizure or paralysis. Investigations of major outbreaks have focused on STEC, rather than on S. dysenteriae serotype 1 because STEC infections are more common in the broader community than Shigella infections.

Figure 1.

After ingestion of food or water contaminated with pathogenic STEC, Stxs may cross the intestinal epithelial barrier via M-cell uptake and transcytosis or paracellular transport. Once in the submucosa, the toxins activate innate immune cells, such as neutrophils or monocytes that act as “carrier” cells to deliver Stxs in the bloodstream and may also further exacerbate tissue injury via localized production of proinflammatory cytokines. Ultimately, the toxins are transferred to glomerular endothelial cells and tubular epithelial cells, which are rich in the toxin receptor Gb3. Damage to the kidney, the primary target organ, leads to D + HUS (diarrhea-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome).

In the United States

In 1982, two severe outbreaks that caused HUS occurred in Oregon and Michigan. E. coli O157:H7 was isolated from the stool specimens of patients and determined to be the cause of disease (Centers for Disease, 1982). After a year, production of Stxs was confirmed by comparing toxins purified from S. dysenteriae and three E. coli isolates from the outbreaks (O'Brien et al., 1983). Since then, STEC O157 has rapidly emerged as a major problem in the food industry and clinics. In the 30 years since the first report, a total of 740 outbreaks caused by STEC O157:H7 and O157:NM were reported in the United States. A total of 13,526 cases resulted in 2,765 hospitalizations (20%), 653 HUS (4.8%), and 73 deaths (0.5%) (Rangel et al., 2005; Heiman et al., 2015). In all years since 1994 except for 1997, the annual outbreak size rose above 30 cases a year.

Food is the best-known transmission route of STEC O157. The frequency of foodborne outbreaks has increased dramatically over the past three decades: 183 out of a total of 350 outbreaks (52%) in the first 20 years (1982–2002) vs. 255 out of a total of 390 outbreaks (65%) in the last 10 years (2003–2012). Over the same period, the incidence of outbreaks via other routes has decreased: person-to-person (14–10%), water (9–4%), and other or unknown reasons (21–11%). Interestingly, STEC outbreaks due to animal contact have also become more common, from 11 (3%) in the first 20 years to 39 (10%) in the last 10 years, indicating that animal resources represent important STEC reservoirs (Rangel et al., 2005; Heiman et al., 2015) (see Environmental Transmission section).

Although STEC O157 was the first E. coli strain involved in Stx–related disease and remains the most important strain in this regard, non-O157 STEC strains also represent a major public health concern. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that 265,000 STEC infections occur each year in the United States, of which STEC O157 causes 36%; thus 64% of STEC infections are non-O157 (Scallan et al., 2011). More than 50 non-O157 STEC serogroups are involved in human illness. The first US outbreak of non-O157 STEC, caused by STEC O111, was reported in 1990; over the next 20 years (1990–2010), 46 outbreaks caused 1,727 illnesses, 144 hospitalizations, and one death. As with O157, food (n = 20, 43%) is a major transmission route in non-O157 outbreaks (Luna-Gierke et al., 2014).

Since the first outbreak in 1990, 11 serotypes and one undetermined type have been observed in non-O157 outbreaks. The most commonly isolated serotype is O111, followed by O26; together, O111 and O26 account for more than 60% of outbreaks (Brooks et al., 2005; Luna-Gierke et al., 2014). O103, O121, O45, O145, O104, O165, O69, O84, and O141 are also frequently isolated from outbreak patients. Interestingly, although non-O157 infection is almost twice as common as O157 infection, non-O157 strains cause fewer outbreaks than O157 (Scallan et al., 2011). This might be due to the greater severity of O157 (more hospitalization) or issues with subtyping techniques (e.g., it is difficult to subtype non-O157 strains) (Gould et al., 2013).

Outside the United States

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that STEC infection caused more than 1 million illnesses and 100 deaths in 2010 (Havelaar et al., 2015). Between 1998 and 2016, the European region (EUR) and Western Pacific region (WPR) reported 211 STEC outbreaks (EUR: 176, WPR: 35), far fewer than the number of outbreaks in the Americas (708) (FAO/WHO, 2018).

The largest O157 STEC outbreak ever recorded occurred in the WPR (Japan, 1996) (Fukushima et al., 1999). Of 12,680 symptomatic patients, 121 (0.95%) developed HUS, and three died. After that massive outbreak, the frequency of STEC cases increased dramatically: from 1999 to 2012, more than 3,000 cases were reported in Japan, whereas during the previous 5 years (1991–1995) the annual average was only 105 cases. Following O157, the most frequent serotype, other common serogroups of STEC are O26, O111, O103, O121, and O145 (Terajima et al., 2014).

The most severe outbreak of non-O157 STEC (O104) occurred in EUR (Germany, 2011): over a 3 months period, 3,816 cases were reported. Despite the smaller number of cases relative to the Sakai outbreak, the rates of HUS (n = 845, 22.4%) and death (n = 54) made the German outbreak historic (Frank et al., 2011). According to surveillance reports from Food- and Waterborne Diseases and Zoonoses and the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, the total number of confirmed STEC infections was 3,573 (doi: 10.2903/j.efsa.2011.2090) in 2009, increasing dramatically to 6,073 cases in 2017 (https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2018.5500). As in other regions, the most commonly reported serogroup from 2009 to 2017 was O157, followed by O26, O103, O91, O145, and O146. However, the proportion of O157 dropped from 51.7 to 31.9%, whereas the proportion of non-O157 infections increased accordingly. Among the 31 countries in Europe, Germany and the United Kingdom had the highest human STEC infection rates.

Environmental Transmission of STEC

Over the past decade, interest in zoonotic pathogens of wildlife origin has increased because those pathogens were shown to constitute the primary source (>60%) of emerging infectious diseases (Jones et al., 2008). Moreover, adaptation of certain urban exploiter animal species has increased contact between wild animals and humans, potentiating the transmission of zoonotic pathogens by fecal contamination of agri-food, the environment, or the water chain (Rothenburger et al., 2017). Although most E. coli are commensal organisms of both humans and animals, the emergence of STEC has been reported in almost all parts of the world and from a wide variety of animal species, including mammals, birds, amphibians, fish, and invertebrates (Persad and LeJeune, 2014; Espinosa et al., 2018). We have updated the list of animal species reported to be reservoir or spillover hosts for, or to be contaminated by, STEC strains (Table 1).

Table 1.

Animal species recently identified as potential STEC reservoirs.

| Common name | Scientific name | References |

|---|---|---|

| MAMMALS | ||

| RUMINANTS | ||

| Cattle | Bos taurus | Gyles, 2007 |

| Goats | Capra aegagrus hircus | Beutin et al., 1993 |

| Sheep | Ovis aries | Gyles, 2007 |

| Water buffalo | Bubalus bubalis | Galiero et al., 2005 |

| White-tailed deer | Odocoileus virginianus | Sargeant et al., 1999 |

| Red deer | Cervus elaphus | Bardiau et al., 2010 |

| Fallow deer | Dama dama | Bardiau et al., 2010 |

| Roe deer | Capreolus capreolus | Bardiau et al., 2010 |

| American bison | Bison bison | Reinstein et al., 2007 |

| Elk | Cervus canadensis | Franklin et al., 2013 |

| Llamas | Lama glama | Mohammed Hamzah et al., 2013 |

| Alpaca | Lama pacos | Leotta et al., 2006 |

| Yak | Bos grunniens | Leotta et al., 2006 |

| Eland | Taurotragus oryx | Leotta et al., 2006 |

| Antelope | Antilope cervicapra | Leotta et al., 2006 |

| Mountain goat | Oreamnos americanus | Chandran and Mazumder, 2013 |

| Guanaco | Lama guanicoe | Mercado et al., 2004 |

| Moose | Alces alces | Nyholm et al., 2015 |

| Chamois | Rupicapra rupicapra | Hofer et al., 2012 |

| Ibex | Capra ibex | Hofer et al., 2012 |

| MONOGASTRICS | ||

| Domestic swine | Sus domesticus | Gyles, 2007 |

| Feral swine (or wild boar) | Sus scrofa | Wacheck et al., 2010 |

| Horses | Equus ferus caballus | Hancock et al., 1998 |

| Donkey | Equus africanus asinus | Chandran and Mazumder, 2013 |

| Dogs | Canis lupus familiaris | Beutin et al., 1993 |

| Cats | Felis catus | Beutin, 1999 |

| Coyote | Canis latrans | Chandran and Mazumder, 2013 |

| Fox | Vulpes vulpes | Chandran and Mazumder, 2013 |

| Rabbit | Oryctolagus cuniculus | Pritchard et al., 2001 |

| Hares | Lepus timidus | Espinosa et al., 2018 |

| Pika | Ochotona daurica | Espinosa et al., 2018 |

| Raccoon | Procyon lotor | Shere et al., 1998 |

| Rats | Rattus spp. | Nielsen et al., 2004 |

| Norway rats | Rattus novegicus | Cizek et al., 2000 |

| Ground hog | Marmota monax | Chandran and Mazumder, 2013 |

| Patagonian cavy | Dolichotis patagonus | Leotta et al., 2006 |

| Agouti | Dasyprocta spp. | Espinosa et al., 2018 |

| Lowland paca | Cuniculus paca | Espinosa et al., 2018 |

| Bear | Unknown | Vasan et al., 2013 |

| Opossum | Unknown | Espinosa et al., 2018 |

| Armadillo | Unknown | Espinosa et al., 2018 |

| Cougar | Puma concolor | Espinosa et al., 2018 |

| Macaques | Macaca spp. | Espinosa et al., 2018 |

| Peccary | Unknown | Espinosa et al., 2018 |

| Ferrets | Mustela putorius furo | Woods et al., 2002 |

| Mice | Mus spp. | Wadolkowski et al., 1990 |

| BIRDS | ||

| Chicken | Gallus gallus domesticus | Ferens and Hovde, 2011 |

| Domestic duck | Anas platyrhynchos domesticus | Koochakzadeh et al., 2015 |

| Turkeys | Meleagris gallopavo | Ferens and Hovde, 2011 |

| Pigeon | Columba livia | Foster et al., 2006 |

| Starling | Sturnus vulgaris | Kobayashi et al., 2009 |

| Geese | Branta canadensis | Kullas et al., 2002 |

| Turtle dove | Streptopelia turtur | Kobayashi et al., 2009 |

| Barn swallow | Hirundo rustica | Kobayashi et al., 2009 |

| Cockatiels | Nymphicus hollandicus | Gioia-Di Chiacchio et al., 2018 |

| Budgerigars | Melopsittacus undulatus | Gioia-Di Chiacchio et al., 2018 |

| Red-legged seriema | Cariama cristata | Borges et al., 2017 |

| Roadside hawk | Rupornis magnirostris | Borges et al., 2017 |

| Cattle egrets | Bubulcus ibis | Fadel et al., 2017 |

| House crows | Corvus splendens | Fadel et al., 2017 |

| Moorhens | Gallinula chloropus | Fadel et al., 2017 |

| House teals | Anas crecca | Fadel et al., 2017 |

| Great egrets | Ardea alba | De Oliveira et al., 2018 |

| Lesser Kestrel | Falco naumanni | Koochakzadeh et al., 2015 |

| Indian peafowl | Pavo cristatus | Milton et al., 2019 |

| Sarus crane | Antigone antigone | Milton et al., 2019 |

| Barn swallow | Hirundo rustica | Kobayashi et al., 2009 |

| Seagulls | Unknown | Makino et al., 2000 |

| FISH | ||

| Nile tilapia | Oreochromis niloticus | Cardozo et al., 2018 |

| African sharptooth catfish | Clarias lazera | Hussein et al., 2019 |

| Flathead gray mullet | Mugil cephalus | Hussein et al., 2019 |

| Atlantic lizardfish | Synodus saurus | Hussein et al., 2019 |

| Red porgy | Pagrus pagrus | Hussein et al., 2019 |

| Catla | Labeo catla | Sekhar et al., 2017 |

| Grass carp | Ctenopharyngodon idella | Siddhnath et al., 2018 |

| Mrigal | Cirrhinus mrigala | Siddhnath et al., 2018 |

| Common carp | Cyprinus carpio | Siddhnath et al., 2018 |

| AMPHIBIANS | ||

| Red-eyed tree frog | Agalychnis callidryas | Dipineto et al., 2010 |

| Oriental fire-bellied toad | Bombina orientalis | Dipineto et al., 2010 |

| INVERTEBRATES | ||

| Blue/Mediterranean mussel | Mytilus edulis/galloprovincialis | Gourmelon et al., 2006 |

| Pacific oyster | Crassostrea gigas | Gourmelon et al., 2006 |

| Common cockle | Cerastoderma edule | Gourmelon et al., 2006 |

| Indian white shrimp | Fenneropenaeus indicus | Surendraraj et al., 2010 |

| European flat oyster | Ostrea edulis | Martin et al., 2019 |

| House fly | Musca domestica | Alam and Zurek, 2004 |

| Dung beetle | Catharsius molossus | Xu et al., 2003 |

| Black dump fly | Hydrotaea aenescens | Szalanski et al., 2004 |

Domestic Animals Are Indisputable Reservoirs of STEC

Ruminants are recognized as principal reservoirs of STEC, especially O157 (Gyles, 2007; La Ragione et al., 2009). As with humans, ruminants are exposed to STEC through contaminated feed and drinking water, or by exposure to the feces of other animals that are shedding the bacteria (LeJeune et al., 2001; Persad and LeJeune, 2014). Among ruminants, cattle (especially ruminating post-weaning calves and heifers) are considered to be the most important STEC reservoirs without symptomatic colonization (Caprioli et al., 2005; Gyles, 2007; Ferens and Hovde, 2011). The natural absence of vascular receptors (globotriaosylceramide) in the intestinal vasculature of the cattle inhibits endocytosis and transportation of Stxs to other organs that might be sensitive to the toxins, resulting in asymptomatic colonization in the large intestine (Pruimboom-Brees et al., 2000; Naylor et al., 2003; Nguyen and Sperandio, 2012). Like cattle, smaller ruminants, such as sheep and goats are also recognized as significant carriers due to their ability to harbor STEC O157 and other serotypes; these animals are important asymptomatic shedders in the epidemiology of bacterial infections in the United States, Australia, and Europe (Beutin et al., 1993; Cortes et al., 2005; Gyles, 2007; La Ragione et al., 2009; Brandal et al., 2012). Also as in cattle, the asymptomatic nature of STEC colonization in smaller ruminants might be due to their lack of vascular receptors for Stx (Persad and LeJeune, 2014). In addition, STEC O157 and non-O157 strains have been reported in other domestic or captive ruminant species, such as alpacas, antelopes, American bison, various deer species, elk, llamas, moose, water buffalo, and yaks (Galiero et al., 2005; French et al., 2010; Chandran and Mazumder, 2013; Mohammed Hamzah et al., 2013; Nyholm et al., 2015).

Several recent surveillance studies have provided strong evidence that monogastric farm animals should now be considered as important reservoir or spillover hosts of STEC. Although the prevalence of STEC O157 and other serotypes varies in swine (Fairbrother and Nadeau, 2006; Ferens and Hovde, 2011), pigs have been shown to harbor and shed STEC for up to 2 months post-infection (Booher et al., 2002). Moreover, because pigs possess Stx-sensitive vascular receptors (globotetraosylceramide) in their intestines, they are susceptible to STEC strains possessing Stx2e, which cause edema with apparent clinical signs and mortality (Waddell et al., 1998; Pruimboom-Brees et al., 2000; Fratamico et al., 2004; Steil et al., 2016). Moreover, although horses are not considered reservoirs for STEC due to its low prevalence in that species (Hancock et al., 1998; Pritchard et al., 2009; Lengacher et al., 2010), some cases of clinical infection from equine contact have been reported (Chalmers et al., 1997; Luna et al., 2018); therefore, horses should be considered as a potential source of infection. Domestic poultry, such as chicken, duck, and turkeys have also been reported to carry STEC (Doane et al., 2007; Ferens and Hovde, 2011; Koochakzadeh et al., 2015). In particular, chickens which were experimentally inoculated with STEC O157 can harbor and shed the bacteria in their feces for almost a year (Schoeni and Doyle, 1994).

The importance of companion animals (pets) in the epidemiology of STEC infection should not be underestimated. Via their feces, pets, such as dogs and cats can serve as asymptomatic shedders in the epidemiology of a wide range of STEC serotypes (Beutin, 1999; Roopnarine et al., 2007; Hogg et al., 2009; Rumi et al., 2012). Accordingly, several clinical infections due to canine and feline exposure have been reported (Busch et al., 2007; Persad and LeJeune, 2014; McFarland et al., 2017). STEC has also been found from the feces of wild canids but not felids (Mora et al., 2012; Persad and LeJeune, 2014).

Wild Animals Are Important Reservoir or Spillover Hosts of STEC

The number of STEC outbreaks associated with the consumption of fruits and vegetables contaminated with wild animal feces is increasing (World Health Organization, 2016). Hence, from a global public health standpoint, it is important to investigate the prevalence of STEC in urban exploiter and wild animals that can transmit the bacteria to human by direct and/or indirect contact. Therefore, several studies have investigated the prevalence of STEC among urban exploiter species, such as rats (Himsworth et al., 2015), pigeons (Gargiulo et al., 2014; Murakami et al., 2014), and flies (Kobayashi et al., 1999; Alam and Zurek, 2004; Keen et al., 2006). In fact, rodents are capable of harboring and shedding STEC, and various serogroups have been recovered from animals living in urban areas and farms (Blanco Crivelli et al., 2012; Kilonzo et al., 2013). Moreover, many wild bird species found in close proximity to livestock operations, waste disposal landfill sites, and human habitation areas have also been identified as potential sources of STEC infection (Cizek et al., 2000; Pedersen and Clark, 2007). In addition, houseflies can harbor and transmit STEC O157 to other animals, demonstrating that insects can be important vectors in the dissemination of STEC within the environment (Kobayashi et al., 1999; Alam and Zurek, 2004; Keen et al., 2006). Because domestic animal feed represents an easy food source for rodents, birds, and insects, these animals are attracted to farms and may transmit STEC between livestock and humans or vice versa.

Likewise, wild animals residing in close proximity to livestock facilities can be contaminated (or harbored) with STEC (Espinosa et al., 2018). Several recent studies emphasized the urgent need to investigate the prevalence of STEC in wild animals, as some large STEC outbreaks were closely related to or originated from contamination from wild animal feces (Laidler et al., 2013; Crook and Senior, 2017; Soderqvist et al., 2019). Although wild animals were identified as a source of STEC in the 1990s, more than 70% of relevant studies were published since the turn of the century, and an increasing number of wild animal species have been identified as reservoir or spillover hosts for STEC (Espinosa et al., 2018). Nevertheless, very little published research has addressed the role of wild animals in the transmission of STEC to humans, domestic animals, and within the food chain. Animals, such as wild boars, deer, birds, and rodents might be involved in direct interspecies contact between humans, domestic, and wild animals, thereby creating a circle of transmission that increases the prevalence of STEC. These species should be thoroughly monitored, as they could potentially cause a spillover or spillback to humans and other animals (Daszak et al., 2000).

Emerging Reservoirs of STEC and Needs for the One Health Approach

Numerous studies have reported both O157 and non-O157 STEC in fresh fish and shellfish, and their ready-to-eat products in retail markets (Thampuran et al., 2005; Surendraraj et al., 2010; Prakasan et al., 2018), suggesting that human activities, such as handling, processing, and ingestion of the products might be a major source of STEC contamination. Interestingly, fish and shellfish residing in coastal areas, some cultured fish, and those in close proximity to or downstream of animal livestock facilities have been found to be contaminated with STEC (Gourmelon et al., 2006; Sekhar et al., 2017; Cardozo et al., 2018; Siddhnath et al., 2018; Hussein et al., 2019). These results strongly indicate that fish and shellfish are a potential reservoir or spillover hosts of STEC, and that effluent water from STEC-contaminated culture ponds might also be an additional potential source of transmission, emphasizing the need for further investigations of the aquaculture industry.

Based on the findings of recent surveillance approaches, a wide range of domestic, captive, and wild animals, including aquatic animals, can transmit STEC to humans directly by ingestion or contact at farms and petting zoos, or indirectly through fecal contaminations in water sources, vegetable fields, or meats and milks. Moreover, STEC is closely associated with human activities; therefore, the broad expansion of human activities due to technological advances will expand contaminations to an increasingly wider variety of wild organisms and foodstuffs in the future. Therefore, a detailed identification of the prevalence of STEC in various animal species will be essential for epidemiological investigations and the development of proper risk mitigation strategies (Persad and LeJeune, 2014). The integration of human and animal health was appreciated in ancient times, but this idea was comprehensively revisited through the One Health perspective, which proposes a unification of human and veterinary medicine to protect against zoonotic pathogens (King et al., 2008; Zinsstag et al., 2011). Investigations of STEC outbreaks in humans also clearly demonstrate the relevance of the One Health concept (Jay et al., 2007; Laidler et al., 2013; McFarland et al., 2017). Moreover, the importance of a One Health approach for control or prevention of STEC infection has already been emphasized in practical cases (Garcia et al., 2010). A number of new animal species, including those of aquatic origin, have been identified as unexpected reservoir or spillover hosts of STEC. Therefore, we propose an alternative One Health approach in which coordinated multidisciplinary efforts integrate terrestrial and aquatic animal medicine within future STEC surveillance. These efforts should facilitate the development of novel strategies to prevent, control, and treat zoonotic STEC infections.

Conclusion

Since the advent of systematic and efficient diagnostic techniques, reports of national STEC outbreaks have increased dramatically. The current world-wide surveillance system reveals the impact of STEC infection, the diversity of STEC, and sources of contamination. Although contaminated food is the most prominent source of STEC outbreaks, infections caused by contact with animals has increased over the past 10 years. Hence, understanding of animals as potential STEC reservoir and their transmission is essential for preventing the occurrence of STEC infections and outbreaks. Multiple complex studies aimed at discovering numerous STEC in the various animals have revealed a wide range of strains capable of producing Stxs, however, it remains to be determined to what extent these newly identified reservoirs are involved in the pathogenesis and transmission of the bacteria. In particular, several animals in more distantly related fields, such as fish produced by the aquaculture industry and a wide range of underestimated wild animal species have been reported as potential STEC reservoirs. Therefore, we propose an alternative One Health approach in which coordinated multidisciplinary efforts integrate terrestrial and aquatic animal medicine in the context of future STEC surveillance efforts.

Author Contributions

Written and revised by J-SK, M-SL, and JK.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported by the KRIBB Research Initiative Programs, the Collaborative Genome Program of the Korea Institute of Marine Science and Technology Promotion (20180430) funded by the Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries, and Basic Science Research Program (2019R1I1A2A01041221) through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), funded by the Ministry of Education.

References

- Alam M. J., Zurek L. (2004). Association of Escherichia coli O157:H7 with houseflies on a cattle farm. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70, 7578–7580. 10.1128/AEM.70.12.7578-7580.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardiau M., Gregoire F., Muylaert A., Nahayo A., Duprez J. N., Mainil J., et al. (2010). Enteropathogenic (EPEC), enterohaemorragic (EHEC) and verotoxigenic (VTEC) Escherichia coli in wild cervids. J. Appl. Microbiol. 109, 2214–2222. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2010.04855.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beutin L. (1999). Escherichia coli as a pathogen in dogs and cats. Vet. Res. 30, 285–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beutin L., Geier D., Steinruck H., Zimmermann S., Scheutz F. (1993). Prevalence and some properties of verotoxin (Shiga-like toxin)-producing Escherichia coli in seven different species of healthy domestic animals. J. Clin. Microbiol. 31, 2483–2488. 10.1128/JCM.31.9.2483-2488.1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco Crivelli X., Rumi M. V., Carfagnini J. C., Degregorio O., Bentancor A. B. (2012). Synanthropic rodents as possible reservoirs of shigatoxigenic Escherichia coli strains. Front. Cell. Infect Microbiol. 2:134. 10.3389/fcimb.2012.00134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boerlin P., McEwen S. A., Boerlin-Petzold F., Wilson J. B., Johnson R. P., Gyles C. L. (1999). Associations between virulence factors of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli and disease in humans. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37, 497–503. 10.1128/JCM.37.3.497-503.1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booher S. L., Cornick N. A., Moon H. W. (2002). Persistence of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in experimentally infected swine. Vet. Microbiol. 89, 69–81. 10.1016/S0378-1135(02)00176-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges C. A., Cardozo M. V., Beraldo L. G., Oliveira E. S., Maluta R. P., Barboza K. B., et al. (2017). Wild birds and urban pigeons as reservoirs for diarrheagenic Escherichia coli with zoonotic potential. J. Microbiol. 55, 344–348. 10.1007/s12275-017-6523-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandal L. T., Sekse C., Lindstedt B. A., Sunde M., Lobersli I., Urdahl A. M., et al. (2012). Norwegian sheep are an important reservoir for human-pathogenic Escherichia coli O26:H11. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78, 4083–4091. 10.1128/AEM.00186-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks J. T., Sowers E. G., Wells J. G., Greene K. D., Griffin P. M., Hoekstra R. M., et al. (2005). Non-O157 Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli infections in the United States, 1983–2002. J. Infect. Dis. 192, 1422–1429. 10.1086/466536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busch U., Hormansdorfer S., Schranner S., Huber I., Bogner K. H., Sing A. (2007). Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli excretion by child and her cat. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 13, 348–349. 10.3201/eid1302.061106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caprioli A., Morabito S., Brugere H., Oswald E. (2005). Enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli: emerging issues on virulence and modes of transmission. Vet. Res. 36, 289–311. 10.1051/vetres:2005002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardozo M. V., Borges C. A., Beraldo L. G., Maluta R. P., Pollo A. S., Borzi M. M., et al. (2018). Shigatoxigenic and atypical enteropathogenic Escherichia coli in fish for human consumption. Braz. J. Microbiol. 49, 936–941. 10.1016/j.bjm.2018.02.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease C. (1982). Isolation of E. coli O157:H7 from sporadic cases of hemorrhagic colitis–United States. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 31, 580–585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalmers R. M., Salmon R. L., Willshaw G. A., Cheasty T., Looker N., Davies I., et al. (1997). Vero-cytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli O157 in a farmer handling horses. Lancet 349:1816. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)61697-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandran A., Mazumder A. (2013). Prevalence of diarrhea-associated virulence genes and genetic diversity in Escherichia coli isolates from fecal material of various animal hosts. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79, 7371–7380. 10.1128/AEM.02653-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cizek A., Literak I., Scheer P. (2000). Survival of Escherichia coli O157 in faeces of experimentally infected rats and domestic pigeons. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 31, 349–352. 10.1046/j.1472-765x.2000.00820.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortes C., De La Fuente R., Blanco J., Blanco M., Blanco J. E., Dhabi G., et al. (2005). Serotypes, virulence genes and intimin types of verotoxin-producing Escherichia coli and enteropathogenic E. coli isolated from healthy dairy goats in Spain. Vet. Microbiol. 110, 67–76. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2005.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crook B., Senior H. (2017). Wildlife as source of human Escherichia coli O157 infection. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 23:2122 10.3201/eid2312.171210 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Daszak P., Cunningham A. A., Hyatt A. D. (2000). Emerging infectious diseases of wildlife–threats to biodiversity and human health. Science 287, 443–449. 10.1126/science.287.5452.443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Oliveira M. C. V., Camargo B. Q., Cunha M. P. V., Saidenberg A. B., Teixeira R. H. F., Matajira C. E. C., et al. (2018). Free-ranging synanthropic birds (Ardea alba and Columba livia domestica) as carriers of Salmonella spp. and diarrheagenic Escherichia coli in the vicinity of an Urban Zoo. Vector Borne Zoonotic. Dis. 18, 65–69. 10.1089/vbz.2017.2174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dipineto L., Gargiulo A., Russo T. P., De Luca Bossa L. M., Borrelli L., D'ovidio D., et al. (2010). Survey of Escherichia coli O157 in captive frogs. J. Wildl. Dis. 46, 944–946. 10.7589/0090-3558-46.3.944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doane C. A., Pangloli P., Richards H. A., Mount J. R., Golden D. A., Draughon F. A. (2007). Occurrence of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in diverse farm environments. J. Food Prot. 70, 6–10. 10.4315/0362-028X-70.1.6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson M. C., Doyle M. P. (2007). Food as a vehicle for transmission of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli. J. Food Prot. 70, 2426–2449. 10.4315/0362-028X-70.10.2426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa L., Gray A., Duffy G., Fanning S., Mcmahon B. J. (2018). A scoping review on the prevalence of shiga-toxigenic Escherichia coli in wild animal species. Zoonoses Public Health 65, 911–920. 10.1111/zph.12508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadel H. M., Afifi R., Al-Qabili D. M. (2017). Characterization and zoonotic impact of Shiga toxin producing Escherichia coli in some wild bird species. Vet. World 10, 1118–1128. 10.14202/vetworld.2017.1118-1128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairbrother J. M., Nadeau E. (2006). Escherichia coli: on-farm contamination of animals. Rev. Sci. Tech. 25, 555–569. 10.20506/rst.25.2.1682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FAO/WHO (2018). “Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) and food: attribution, characterization, and monitoring,” in Microbiological Risk Assessment Series (FAO/WHO) (Rome: FAO; ). [Google Scholar]

- Ferens W. A., Hovde C. J. (2011). Escherichia coli O157:H7: animal reservoir and sources of human infection. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 8, 465–487. 10.1089/fpd.2010.0673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster G., Evans J., Knight H. I., Smith A. W., Gunn G. J., Allison L. J., et al. (2006). Analysis of feces samples collected from a wild-bird garden feeding station in Scotland for the presence of verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli O157. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 2265–2267. 10.1128/AEM.72.3.2265-2267.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank C., Werber D., Cramer J. P., Askar M., Faber M., An Der Heiden M., et al. (2011). Epidemic profile of Shiga-toxin-producing Escherichia coli O104:H4 outbreak in Germany. N. Engl. J. Med. 365, 1771–1780. 10.1056/NEJMoa1106483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankel G., Phillips A. D., Rosenshine I., Dougan G., Kaper J. B., Knutton S. (1998). Enteropathogenic and enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli: more subversive elements. Mol. Microbiol. 30, 911–921. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01144.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin A. B., Vercauteren K. C., Maguire H., Cichon M. K., Fischer J. W., Lavelle M. J., et al. (2013). Wild ungulates as disseminators of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli in urban areas. PLoS ONE 8:e81512. 10.1371/journal.pone.0081512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser M. E., Chernaia M. M., Kozlov Y. V., James M. N. (1994). Crystal structure of the holotoxin from Shigella dysenteriae at 2.5 a resolution. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1, 59–64. 10.1038/nsb0194-59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fratamico P. M., Bagi L. K., Bush E. J., Solow B. T. (2004). Prevalence and characterization of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli in swine feces recovered in the national animal health monitoring system's Swine 2000 study. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70, 7173–7178. 10.1128/AEM.70.12.7173-7178.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French E., Rodriguez-Palacios A., LeJeune J. T. (2010). Enteric bacterial pathogens with zoonotic potential isolated from farm-raised deer. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 7, 1031–1037. 10.1089/fpd.2009.0486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukushima H., Hashizume T., Morita Y., Tanaka J., Azuma K., Mizumoto Y., et al. (1999). Clinical experiences in sakai city hospital during the massive outbreak of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157 infections in Sakai City, 1996. Pediatr. Int. 41, 213–217. 10.1046/j.1442-200X.1999.4121041.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galiero G., Conedera G., Alfano D., Caprioli A. (2005). Isolation of verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli O157 from water buffaloes (Bubalus bubalis) in southern Italy. Vet. Rec. 156, 382–383. 10.1136/vr.156.12.382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia A., Fox J. G., Besser T. E. (2010). Zoonotic enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli: a one health perspective. ILAR J. 51, 221–232. 10.1093/ilar.51.3.221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gargiulo A., Russo T. P., Schettini R., Mallardo K., Calabria M., Menna L. F., et al. (2014). Occurrence of enteropathogenic bacteria in urban pigeons (columba livia) in Italy. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 14, 251–255. 10.1089/vbz.2011.0943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gioia-Di Chiacchio R. M., Cunha M. P. V., De Sa L. R. M., Davies Y. M., Pereira C. B. P., Martins F. H., et al. (2018). Novel hybrid of typical enteropathogenic Escherichia coli and shiga-toxin-producing E. coli (tEPEC/STEC) emerging from pet birds. Front. Microbiol. 9:2975. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould L. H., Mody R. K., Ong K. L., Clogher P., Cronquist A. B., Garman K. N., et al. (2013). Increased recognition of non-O157 Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli infections in the United States during 2000-2010: epidemiologic features and comparison with E. coli O157 infections. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 10, 453–460. 10.1089/fpd.2012.1401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gourmelon M., Montet M. P., Lozach S., Le Mennec C., Pommepuy M., Beutin L., et al. (2006). First isolation of Shiga toxin 1d producing Escherichia coli variant strains in shellfish from coastal areas in France. J. Appl. Microbiol. 100, 85–97. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2005.02753.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyles C. L. (2007). Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli: an overview. J. Anim. Sci. 85, E45–62. 10.2527/jas.2006-508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock D. D., Besser T. E., Rice D. H., Ebel E. D., Herriott D. E., Carpenter L. V. (1998). Multiple sources of Escherichia coli O157 in feedlots and dairy farms in the northwestern USA. Prev. Vet. Med. 35, 11–19. 10.1016/S0167-5877(98)00050-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havelaar A. H., Kirk M. D., Torgerson P. R., Gibb H. J., Hald T., Lake R. J., et al. (2015). World health organization global estimates and regional comparisons of the burden of foodborne disease in 2010. PLoS Med. 12:e1001923. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heiman K. E., Mody R. K., Johnson S. D., Griffin P. M., Gould L. H. (2015). Escherichia coli O157 outbreaks in the United States, 2003–2012. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 21, 1293–1301. 10.3201/eid2108.141364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himsworth C. G., Zabek E., Desruisseau A., Parmley E. J., Reid-Smith R., Jardine C. M., et al. (2015). Prevalence and characteristics of Escherichia coli and Salmonella spp. In the feces of wild urban Norway and Black Rats (Rattus norvegicus and Rattus rattus) from an inner-city neighborhood of Vancouver. Can. J. Wildl. Dis. 51, 589–600. 10.7589/2014-09-242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofer E., Cernela N., Stephan R. (2012). Shiga toxin subtypes associated with Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli strains isolated from red deer, roe deer, chamois, and ibex. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 9, 792–795. 10.1089/fpd.2012.1156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogg R. A., Holmes J. P., Ghebrehewet S., Elders K., Hart J., Whiteside C., et al. (2009). Probable zoonotic transmission of verocytotoxigenic Escherichia coli O 157 by dogs. Vet. Rec. 164, 304–305. 10.1136/vr.164.10.304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussein M. A., Merwad A. M. A., Elabbasy M. T., Suelam I. I. A., Abdelwahab A. M., Taha M. A. (2019). Prevalence of enterotoxigenic Staphylococcus aureus and Shiga toxin producing Escherichia coli in fish in Egypt: quality parameters and public health hazard. Vector Borne. Zoonotic. Dis. 19, 255–264. 10.1089/vbz.2018.2346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jay M. T., Cooley M., Carychao D., Wiscomb G. W., Sweitzer R. A., Crawford-Miksza L., et al. (2007). Escherichia coli O157:H7 in feral swine near spinach fields and cattle, central California coast. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 13, 1908–1911. 10.3201/eid1312.070763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson W. M., Lior H., Bezanson G. S. (1983). Cytotoxic Escherichia coli O157:H7 associated with haemorrhagic colitis in Canada. Lancet 1:76. 10.1016/S0140-6736(83)91616-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones B. A., Grace D., Kock R., Alonso S., Rushton J., Said M. Y., et al. (2013). Zoonosis emergence linked to agricultural intensification and environmental change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 8399–8404. 10.1073/pnas.1208059110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones K. E., Patel N. G., Levy M. A., Storeygard A., Balk D., Gittleman J. L., et al. (2008). Global trends in emerging infectious diseases. Nature 451, 990–993. 10.1038/nature06536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaper J. B., Nataro J. P., Mobley H. L. (2004). Pathogenic Escherichia coli. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2, 123–140. 10.1038/nrmicro818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaper J. B., O'Brien A. D. (2014). Overview and historical perspectives. Microbiol. Spectr. 2, 1–2. 10.1128/microbiolspec.EHEC-0028-2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karmali M. A., Mascarenhas M., Shen S., Ziebell K., Johnson S., Reid-Smith R., et al. (2003). Association of genomic O island 122 of Escherichia coli EDL 933 with verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli seropathotypes that are linked to epidemic and/or serious disease. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41, 4930–4940. 10.1128/JCM.41.11.4930-4940.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keen J. E., Wittum T. E., Dunn J. R., Bono J. L., Durso L. M. (2006). Shiga-toxigenic Escherichia coli O157 in agricultural fair livestock, United States. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 12, 780–786. 10.3201/eid1205.050984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilonzo C., Li X., Vivas E. J., Jay-Russell M. T., Fernandez K. L., Atwill E. R. (2013). Fecal shedding of zoonotic food-borne pathogens by wild rodents in a major agricultural region of the central California coast. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79, 6337–6344. 10.1128/AEM.01503-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King L. J., Anderson L. R., Blackmore C. G., Blackwell M. J., Lautner E. A., Marcus L. C., et al. (2008). Executive summary of the AVMA one health initiative task force report. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 233, 259–261. 10.2460/javma.233.2.259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kintz E., Brainard J., Hooper L., Hunter P. (2017). Transmission pathways for sporadic Shiga-toxin producing E. coli infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 220, 57–67. 10.1016/j.ijheh.2016.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi H., Kanazaki M., Hata E., Kubo M. (2009). Prevalence and characteristics of eae- and stx-positive strains of Escherichia coli from wild birds in the immediate environment of Tokyo Bay. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75, 292–295. 10.1128/AEM.01534-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi M., Sasaki T., Saito N., Tamura K., Suzuki K., Watanabe H., et al. (1999). Houseflies: not simple mechanical vectors of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 61, 625–629. 10.4269/ajtmh.1999.61.625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konowalchuk J., Speirs J. I., Stavric S. (1977). Vero response to a cytotoxin of Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 18, 775–779. 10.1128/IAI.18.3.775-779.1977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koochakzadeh A., Askari Badouei M., Zahraei Salehi T., Aghasharif S., Soltani M., Ehsan M. R. (2015). Prevalence of Shiga toxin-producing and enteropathogenic Escherichia coli in wild and pet birds in Iran. Braz. J. Poult. Sci. 17, 445–450. 10.1590/1516-635X1704445-450 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kullas H., Coles M., Rhyan J., Clark L. (2002). Prevalence of Escherichia coli serogroups and human virulence factors in faeces of urban Canada geese (branta canadensis). Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 12, 153–162. 10.1080/09603120220129319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Ragione R. M., Best A., Woodward M. J., Wales A. D. (2009). Escherichia coli O157:H7 colonization in small domestic ruminants. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 33, 394–410. 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2008.00138.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laidler M. R., Tourdjman M., Buser G. L., Hostetler T., Repp K. K., Leman R., et al. (2013). Escherichia coli O157:H7 infections associated with consumption of locally grown strawberries contaminated by deer. Clin. Infect. Dis. 57, 1129–1134. 10.1093/cid/cit468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M. S., Koo S., Jeong D. G., Tesh V. L. (2016). Shiga toxins as multi-functional proteins: induction of host cellular stress responses, role in pathogenesis and therapeutic applications. Toxins (Basel). 8:77. 10.3390/toxins8030077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M. S., Tesh V. L. (2019). Roles of Shiga toxins in immunopathology. Toxins (Basel). 11:212. 10.3390/toxins11040212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeJeune J. T., Besser T. E., Merrill N. L., Rice D. H., Hancock D. D. (2001). Livestock drinking water microbiology and the factors influencing the quality of drinking water offered to cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 84, 1856–1862. 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(01)74626-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lengacher B., Kline T. R., Harpster L., Williams M. L., LeJeune J. T. (2010). Low prevalence of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in horses in Ohio, USA. J. Food Prot. 73, 2089–2092. 10.4315/0362-028X-73.11.2089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lentz E. K., Leyva-Illades D., Lee M. S., Cherla R. P., Tesh V. L. (2011). Differential response of the human renal proximal tubular epithelial cell line HK-2 to Shiga toxin types 1 and 2. Infect. Immun. 79, 3527–3540. 10.1128/IAI.05139-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leotta G. A., Deza N., Origlia J., Toma C., Chinen I., Miliwebsky E., et al. (2006). Detection and characterization of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli in captive non-domestic mammals. Vet. Microbiol. 118, 151–157. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2006.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luna S., Krishnasamy V., Saw L., Smith L., Wagner J., Weigand J., et al. (2018). Outbreak of E. coli O157:H7 infections associated with exposure to animal manure in a rural community–Arizona and Utah, June–July 2017. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 67, 659–662. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6723a2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luna-Gierke R. E., Griffin P. M., Gould L. H., Herman K., Bopp C. A., Strockbine N., et al. (2014). Outbreaks of non-O157 Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli infection: USA. Epidemiol. Infect. 142, 2270–2280. 10.1017/S0950268813003233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makino S., Kobori H., Asakura H., Watarai M., Shirahata T., Ikeda T., et al. (2000). Detection and characterization of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli from seagulls. Epidemiol. Infect. 125, 55–61. 10.1017/S0950268899004100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin C. C., Svanevik C. S., Lunestad B. T., Sekse C., Johannessen G. S. (2019). Isolation and characterisation of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli from Norwegian bivalves. Food Microbiol. 84:103268. 10.1016/j.fm.2019.103268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarland N., Bundle N., Jenkins C., Godbole G., Mikhail A., Dallman T., et al. (2017). Recurrent seasonal outbreak of an emerging serotype of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC O55:H7 Stx2a) in the south west of England, July 2014 to September 2015. Euro. Surveill. 22, 1–10. 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2017.22.36.30610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melton-Celsa A. R. (2014). Shiga toxin (Stx) classification, structure and function. Microbiol. Spectr. 2:EHEC-0024-2013. 10.1128/microbiolspec.EHEC-0024-2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercado E. C., Rodriguez S. M., Elizondo A. M., Marcoppido G., Parreno V. (2004). Isolation of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli from a South American camelid (lama guanicoe) with diarrhea. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42, 4809–4811. 10.1128/JCM.42.10.4809-4811.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milton A. P., Agarwal R. K., Priya G. B., Aravind M., Athira C. K., et al. (2019). Captive wildlife from India as carriers of Shiga toxin-producing, enteropathogenic and enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 81, 321–327. 10.1292/jvms.18-0488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed Hamzah A., Mohammed Hussein A., Mahmoud Khalef J. (2013). Isolation of Escherichia coli 0157:H7 strain from fecal samples of zoo animal. Sci. World J. 2013:843968. 10.1155/2013/843968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mora A., Lopez C., Dhabi G., Lopez-Beceiro A. M., Fidalgo L. E., Diaz E. A., et al. (2012). Seropathotypes, phylogroups, stx subtypes, and intimin types of wildlife-carried, Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli strains with the same characteristics as human-pathogenic isolates. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78, 2578–2585. 10.1128/AEM.07520-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami K., Etoh Y., Ichihara S., Maeda E., Takenaka S., Horikawa K., et al. (2014). Isolation and characteristics of Shiga toxin 2f-producing Escherichia coli among pigeons in Kyushu, Japan. PLoS ONE 9:e86076. 10.1371/journal.pone.0086076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nataro J. P., Kaper J. B. (1998). Diarrheagenic Escherichia coli. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 11, 142–201. 10.1128/CMR.11.1.142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naylor S. W., Low J. C., Besser T. E., Mahajan A., Gunn G. J., Pearce M. C., et al. (2003). Lymphoid follicle-dense mucosa at the terminal rectum is the principal site of colonization of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 in the bovine host. Infect. Immun. 71, 1505–1512. 10.1128/IAI.71.3.1505-1512.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen Y., Sperandio V. (2012). Enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC) pathogenesis. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2:90 10.3389/fcimb.2012.00090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen E. M., Skov M. N., Madsen J. J., Lodal J., Jespersen J. B., Baggesen D. L. (2004). Verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli in wild birds and rodents in close proximity to farms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70, 6944–6947. 10.1128/AEM.70.11.6944-6947.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyholm O., Heinikainen S., Pelkonen S., Hallanvuo S., Haukka K., Siitonen A. (2015). Hybrids of shigatoxigenic and enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (STEC/ETEC) among human and animal isolates in Finland. Zoonoses Public Health 62, 518–524. 10.1111/zph.12177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien A. O., Lively T. A., Chen M. E., Rothman S. W., Formal S. B. (1983). Escherichia coli O157:H7 strains associated with haemorrhagic colitis in the United States produce a Shigella dysenteriae 1 (SHIGA) like cytotoxin. Lancet 1:702. 10.1016/S0140-6736(83)91987-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen K., Clark L. (2007). A review of Shiga toxin Escherichia coli and salmonella enterica in cattle and free-ranging birds: potential association and epidemiological links. Hum. Wildl. Confl. 1, 68–77. [Google Scholar]

- Persad A. K., LeJeune J. T. (2014). Animal reservoirs of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli. Microbiol. Spectr. 2:EHEC-0027-2014. 10.1128/microbiolspec.EHEC-0027-2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pradhan S., Pellino C., Macmaster K., Coyle D., Weiss A. A. (2016). Shiga toxin mediated neurologic changes in murine model of disease. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 6:114. 10.3389/fcimb.2016.00114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakasan S., Prabhakar P., Lekshmi M., Kumar S., Nayak B. B. (2018). Isolation of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli harboring variant Shiga toxin genes from seafood. Vet. World 11, 379–385. 10.14202/vetworld.2018.379-385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard G. C., Smith R., Ellis-Iversen J., Cheasty T., Willshaw G. A. (2009). Verocytotoxigenic Escherichia coli O157 in animals on public amenity premises in England and Wales, 1997 to 2007. Vet. Rec. 164, 545–549. 10.1136/vr.164.18.545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard G. C., Williamson S., Carson T., Bailey J. R., Warner L., Willshaw G., et al. (2001). Wild rabbits-a novel vector for verocytotoxigenic Escherichia coli O157. Vet. Rec. 149:567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruimboom-Brees I. M., Morgan T. W., Ackermann M. R., Nystrom E. D., Samuel J. E., Cornick N. A., et al. (2000). Cattle lack vascular receptors for Escherichia coli O157:H7 Shiga toxins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 10325–10329. 10.1073/pnas.190329997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rangel J. M., Sparling P. H., Crowe C., Griffin P. M., Swerdlow D. L. (2005). Epidemiology of Escherichia coli O157:H7 outbreaks, United States, 1982–2002. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 11, 603–609. 10.3201/eid1104.040739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinstein S., Fox J. T., Shi X., Alam M. J., Nagaraja T. G. (2007). Prevalence of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in the American bison (Bison bison). J. Food Prot. 70, 2555–2560. 10.4315/0362-028X-70.11.2555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roopnarine R. R., Ammons D., Rampersad J., Adesiyun A. A. (2007). Occurrence and characterization of verocytotoxigenic Escherichia coli (VTEC) strains from dairy farms in Trinidad. Zoonoses Public Health 54, 78–85. 10.1111/j.1863-2378.2007.01024.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothenburger J. L., Himsworth C. H., Nemeth N. M., Pearl D. L., Jardine C. M. (2017). Environmental factors and zoonotic pathogen ecology in urban exploiter species. Ecohealth 14, 630–641. 10.1007/s10393-017-1258-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumi M. V., Irino K., Deza N., Huguet M. J., Bentancor A. B. (2012). First isolation in argentina of a highly virulent Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli O145:NM from a domestic cat. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 6, 358–363. 10.3855/jidc.2225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandvig K. (2001). Shiga toxins. Toxicon 39, 1629–1635. 10.1016/S0041-0101(01)00150-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargeant J. M., Hafer D. J., Gillespie J. R., Oberst R. D., Flood S. J. (1999). Prevalence of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in white-tailed deer sharing rangeland with cattle. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 215, 792–794. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scallan E., Hoekstra R. M., Angulo F. J., Tauxe R. V., Widdowson M. A., Roy S. L., et al. (2011). Foodborne illness acquired in the United States-major pathogens. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 17, 7–15. 10.3201/eid1701.P11101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheutz F., Teel L. D., Beutin L., Piérard D., Buvens G., Karch H., et al. (2012). Multicenter evaluation of a sequence-based protocol for subtyping Shiga toxins and standardizing Stx nomenclature. J. Clin. Microbiol. 50, 2951–2963. 10.1128/JCM.00860-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoeni J. L., Doyle M. P. (1994). Variable colonization of chickens perorally inoculated with Escherichia coli O157:H7 and subsequent contamination of eggs. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60, 2958–2962. 10.1128/AEM.60.8.2958-2962.1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekhar M. S., Sharif N. M., Rao T. S. (2017). Serotypes of sorbitol-positive shiga toxigenic Escherichia coli (SP-STEC) isolated from freshwater fish. Int. J. Fish. Aquatic Sci. 5, 503–505. [Google Scholar]

- Shere J. A., Bartlett K. J., Kaspar C. W. (1998). Longitudinal study of Escherichia coli O157:H7 dissemination on four dairy farms in wisconsin. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64, 1390–1399. 10.1128/AEM.64.4.1390-1399.1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddhnath K., Majumdar R. K., Parhi J., Sharma S., Mehta N. K., Laishram M. (2018). Detection and characterization of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli from carps from integrated aquaculture system. Aquaculture 487, 97–101. 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2018.01.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Soderqvist K., Rosberg A. K., Boqvist S., Alsanius B., Mogren L., Vagsholm I. (2019). Season and species: two possible hurdles for reducing the food safety risk of Escherichia coli O157 contamination of leafy vegetables. J. Food Prot. 82, 247–255. 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-18-292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steil D., Bonse R., Meisen I., Pohlentz G., Vallejo G., Karch H., et al. (2016). A Topographical atlas of Shiga toxin 2e receptor distribution in the tissues of weaned piglets. Toxins (Basel). 8:357. 10.3390/toxins8120357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surendraraj A., Thampuran N., Joseph T. C. (2010). Molecular screening, isolation, and characterization of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 from retail shrimp. J. Food Prot. 73, 97–103. 10.4315/0362-028X-73.1.97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szalanski A. L., Owens C. B., Mckay T., Steelman C. D. (2004). Detection of campylobacter and Escherichia coli O157:H7 from filth flies by polymerase chain reaction. Med. Vet. Entomol. 18, 241–246. 10.1111/j.0269-283X.2004.00502.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarr P. I., Gordon C. A., Chandler W. L. (2005). Shiga-toxin-producing Escherichia coli and haemolytic uraemic syndrome. Lancet 365, 1073–1086. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71144-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terajima J., Iyoda S., Ohnishi M., Watanabe H. (2014). Shiga toxin (verotoxin)-producing Escherichia coli in Japan. Microbiol. Spectr. 2, 1–9. 10.1128/microbiolspec.EHEC-0011-2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thampuran N., Surendraraj A., Surendran P. K. (2005). Prevalence and characterization of typical and atypical Escherichia coli from fish sold at retail in Cochin, India. J. Food Prot. 68, 2208–2211. 10.4315/0362-028X-68.10.2208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasan A., Leong W. M., Ingham S. C., Ingham B. H. (2013). Thermal tolerance characteristics of non-O157 shiga toxigenic strains of Escherichia coli (STEC) in a beef broth model system are similar to those of O157:H7 STEC. J. Food Prot. 76, 1120–1128. 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-12-500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wacheck S., Fredriksson-Ahomaa M., Konig M., Stolle A., Stephan R. (2010). Wild boars as an important reservoir for foodborne pathogens. Foodborne. Pathog. Dis. 7, 307–312. 10.1089/fpd.2009.0367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waddell T. E., Coomber B. L., Gyles C. L. (1998). Localization of potential binding sites for the edema disease verotoxin (VT2e) in pigs. Can. J. Vet. Res. 62, 81–86. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadolkowski E. A., Burris J. A., O'Brien A. D. (1990). Mouse model for colonization and disease caused by enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. Infect. Immun. 58, 2438–2445. 10.1128/IAI.58.8.2438-2445.1990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods J. B., Schmitt C. K., Darnell S. C., Meysick K. C., O'Brien A. D. (2002). Ferrets as a model system for renal disease secondary to intestinal infection with Escherichia coli O157:H7 and other Shiga toxin-producing E. coli. J. Infect. Dis. 185, 550–554. 10.1086/338633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2016). E. coli Fact Sheet. Retrieved from: https://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs125/en/

- Xu J., Liu Q., Jing H., Pang B., Yang J., Zhao G., et al. (2003). Isolation of Escherichia coli O157:H7 from dung beetles catharsius molossus. Microbiol. Immunol. 47, 45–49. 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2003.tb02784.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinsstag J., Schelling E., Waltner-Toews D., Tanner M. (2011). From “one medicine” to “one health” and systemic approaches to health and well-being. Prev. Vet. Med. 101, 148–156. 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2010.07.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]