Abstract

Objective:

Mindfulness-based interventions are an evidence-based approach utilized in health care. There is developing evidence for effective use with military Veterans. However, little is known about Veterans’ view of mindfulness. This study aims to understand their interests, perceptions, and use of mindfulness to enhance educational outreach and treatment engagement.

Methods:

A cross-sectional study was conducted across the Veterans Health Administration in Salt Lake City, UT by administering a questionnaire to military Veterans. The questionnaire included the following themes: (1) demographics and respondents’ mindfulness practice; (2) respondents’ perceptions and beliefs about mindfulness; and (3) respondents’ knowledge and interest in learning about mindfulness.

Results:

In all, 185 military Veterans were surveyed; 30% practiced mindfulness in the past year, mainly for stress, posttraumatic stress disorder, sleep, and depression. Over 75% who practiced reported perceived benefit. Veterans rarely reported negative beliefs about mindfulness; 56% perceived an understanding of mindfulness and 46% were aware of Veterans Health Administration mindfulness offerings. In all, 55% were interested in learning about mindfulness, 58% were interested in learning how it could help, and 43% were interested in combining mindfulness with a pleasurable activity.

Conclusion:

Educational engagement approaches should be directed toward the benefits of mindfulness practice with minimal need to address negative beliefs. Outreach including education, with an experiential component, about mindfulness classes, availability of evening and weekend classes, individual sessions, and virtual offerings into Veteran’s homes, may enhance engagement in mindfulness-based interventions. Mindfulness-based interventions that combine mindfulness training with an experiential pleasurable activity may be one mechanism to enhance treatment engagement.

Keywords: Mindfulness, Veterans, perceptions, education, treatment engagement

Introduction

Mindfulness is defined as being fully aware, or “paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment and non-judgmentally,” and accepting one’s present experience as it is, without trying to control, change or escape it.1 It is the self-regulation of attention, so that it is maintained on immediate experience, thereby allowing for increased recognition of mental events in the present moment. Studies of citizen populations show the beneficial effects of mindfulness meditation in reducing symptoms related to major health problems, such as chronic pain, depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).2–18 Mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) are also associated with increases in positive affect, general well-being, and immune system functioning.2,19–24 There is growing interest in the use of MBIs for Veterans as well as a developing area of research examining the effects of using MBIs with Veterans. Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) is the most widely studied MBI used among Veterans. The scientific literature reports that MBIs decrease the symptoms of PTSD, depression, anxiety, stress, and pain, as well as improve the management of diabetes mellitus and irritable bowel syndrome among Veterans.11,25–49

However, little is known regarding the perceptions about, interests in, or use of mindfulness among this population. Knowledge regarding Veteran’s perceptions of the benefits of mindfulness, along with motivation to engage in a mindfulness class is also lacking. In the absence of such knowledge, it is unclear how to best engage Veterans in and/or enhance utilization of these interventions.

Veteran treatment engagement within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is a key concern warranting further elucidation. There is evidence that attrition is a common problem among this population, regarding psychosocial interventions, including psychotherapy interventions.50–54 Very little is known about the utilization or engagement of MBIs among Veterans. However, a recent study by the authors of this article reported that treatment engagement of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) for Veterans with psychiatric illness was challenging in an outpatient Veterans affairs (VA) setting, due to a high attrition rate.43

Despite the importance of understanding Veteran perceptions about mindfulness to develop ways to enhance treatment engagement, to our knowledge, only three studies have attempted to examine this question.46–48 All three of these studies were components of broader surveys about multiple complimentary and integrative health (CIH) approaches. The first two studies utilized data from a national VHA’s Veteran Insight Panel (VIP) survey asking Veterans (n = 1230) about their interest in, use of, and satisfaction with 26 CIH approaches in 2017.46,47 These investigators reported that mindfulness was one of the top three most frequently used CIH approaches,47 and that it was used mainly for stress reduction, depression, and anxiety.46,47 Results showed that 17.6% of the 1230 Veterans who completed this national survey practiced mindfulness meditation in the last year.46 Among those who practiced mindfulness, 22% did so a few times a year, 12% did so once a month, 20% did so a few times a month, 18% did so a few times a week, and 28% did so daily.46 In addition, 70% of those who used mindfulness for stress/relaxation reported they found it “moderately or very helpful.”47

In the third study, Held et al.48 conducted a smaller survey investigating Veterans’ experience and interest in CIH practices (n = 134). These investigators reported that 61% practiced at least one of these CIH approaches (meditation, yoga, breathing, or qigong) in the past or currently; 37% were interested in learning more about meditation. However, these survey questions did not determine the type of meditation practiced. In all, 29% reported being interested in trying meditation with an instructor, whereas 14% were interested in trying it on their own. These studies suggest there is low to moderate interest in the use of MBIs among the Veteran population, but do not provide information that might help enhance engagement.

In addition, the perceptions, interests, and use of MBIs among the adult US citizen population has not been well studied. However, there is some evidence that engagement in mindfulness is associated with having higher education, being female, non-Hispanic, and a white-collar worker.55 Another study56 found that older adults reported acceptability and perceived benefits from MBIs for stress management. In addition, those among the adult US population, who practiced mantra, mindfulness, and spiritual meditation, were more likely to be female, White, aged 45–64 years, and college graduates.57 We are interested in learning what, if any, demographic factors influence utilization and engagement of MBIs among the US Veteran population.

Objective

To address these gaps in the literature, the specific aims of this study were to (1) determine the perceptions of, (2) interests in, (3) knowledge of, (4) demographics of, and (5) current use of mindfulness among the Veteran population with the goal of developing strategies to enhance engagement with and utilization of MBIs among the Veteran population.

Methods

Participants and procedures

Veterans receiving medical care at the Veterans Administration Salt Lake City Health Care System (VASLCHCS) and surrounding Vet Centers were randomly asked to complete a paper survey while sitting in outpatient clinic waiting rooms of primary care, pharmacy, mental health, blood draw, radiology, women’s health and patient-centered care, as well as lobbies from September 2018 through February 2019. Potential survey participants were approached by study staff who asked them to complete the brief, 10 min, voluntary, and anonymous survey. No personal identifying information was collected for purposes of this study. The 185 Veterans who agreed to take the survey were considered study participants. Prior to initiating study procedures, the protocol received an Institutional Review Board (IRB) exemption determination from the University of Utah Institutional Review Board and approval by the VASLCHCS Research and Development Committee.

Measure

The locally developed survey, included as a supplement, asked Veterans to provide information regarding their perceptions of, interests in, knowledge about and usage of mindfulness and MBIs.

Items included in the survey:

Knowing what mindfulness is about.

Awareness of mindfulness interventions offered within the VHASLCHSC.

Practice of mindfulness in the past year, inside or outside the VA, in what format (group, Internet, on own), and how often.

Reasons for using mindfulness, including stress, PTSD, depression, pain, sleep, improve health, decrease medications, balance issues, sense of control, and whether they perceived it was beneficial.

Interest in learning more about mindfulness.

Beliefs about practicing mindfulness and taking a mindfulness class.

The survey included “yes” or “no” questions, as well as questions that allowed for multiple answers and free text. Participants were also asked to provide anonymous demographic information, including age, gender, service connection, employment, education, race, ethnicity, income, and marital status.

Data analysis

Descriptive and inferential statistics were used to assess Veterans’ self-reported data, including demographic information, perceptions of and interest in mindfulness, reasons for using mindfulness, and perceived effectiveness of MBIs for specified clinical concerns. Free text responses were independently reviewed and coded by three study staff to establish inter-rater reliability using percent agreement. Pearson’s chi-square tests of independence were performed to determine whether there was a significant association between categorical demographic variables and survey questions regarding understanding, awareness, and usage of mindfulness. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to examine whether frequency of mindfulness practice was associated with greater perceived improvement for specific clinical conditions. Finally, t-tests were used to determine whether participating in a certain type of intervention (VA group, Internet, or self-practice; each coded dichotomously as “used” or “did not use”) was related to subjective improvement in clinical conditions. Data were analyzed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software, version 20.

Results

Characteristics of study participants

Table 1 presents the demographic descriptions of the study participants. However, not all Veterans answered all demographic questions, which is noted for each personal characteristic in the table. Veterans who completed the survey were predominantly male (83%), White (90%), non-Hispanic (88%), service connected (87%), with a mean age of 58 years. Of the Veterans, 67% completed college or higher education; 39% reported a household income of US$40,000 to less than US$100,000, while 49% reported less than US$40,000.

Table 1.

Description of Veterans who completed survey (n = 185).

| Demographic | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Age in years (n = 166) | |

| 21–39 | 33 (20) |

| 40–69 | 87 (52) |

| 70+ | 46 (28) |

| Service connected (n = 160) | |

| Yes | 139 (87) |

| Gender (n = 170) | |

| Male | 141 (83) |

| Female | 28 (17) |

| Transgender | 1 (0.6) |

| Work status (n = 167) | |

| Working | 62 (37) |

| Not working | 105 (63) |

| Education (n = 163) | |

| College or higher | 109 (67) |

| High school or less | 54 (33) |

| Ethnicity (n = 154) | |

| Hispanic | 19 (12) |

| Non-Hispanic | 135 (88) |

| Race (n = 156) | |

| White | 140 (90) |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 4 (3) |

| Asian | 1 (0.6) |

| Black | 9 (6) |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 2 (1) |

| Household income (n = 158) | |

| US<$40,000 | 77 (49) |

| US$40,000 to <US$100,000 | 62 (39) |

| ≥US$100,000 | 11 (7) |

| Unknown | 8 (5) |

| Marital status (n = 164) | |

| Not married | 94 (57) |

| Married (n = 70) | 70 (43) |

All percentages are column percentages.

Knowledge, frequency, and use of mindfulness

One hundred and three (56%) who completed the survey reported perceiving that they knew what mindfulness was about, while 79 (43%) reported they did not; 73 (40%) reported being aware of mindfulness interventions offered at the local VA facility, while 110 (60%) did not. And 55 (30%) reported practicing mindfulness within the past year, either inside or outside the VA facility, while 126 (70%) had not.

Among those who reported using a mindfulness intervention within the past year, 35 (69%) reported that they engaged in a class or group offered by the local VA facility, 9 (18%) reported using an Internet app, and 21 (41%) reported practicing mindfulness on their own. For those who practiced mindfulness, regarding how often they practiced, 28 (53%) reported almost every day or a few times per week, 18 (34%) reported practicing once or a few times per month, and 7 (13%) reported practicing a few times per year. Pearson’s chi-square tests of independence showed that demographic variables were not associated with knowing what mindfulness is about, being aware of mindfulness interventions offered at the local VA facility, nor using mindfulness in the past year.

Reasons for use and perceived effectiveness of mindfulness

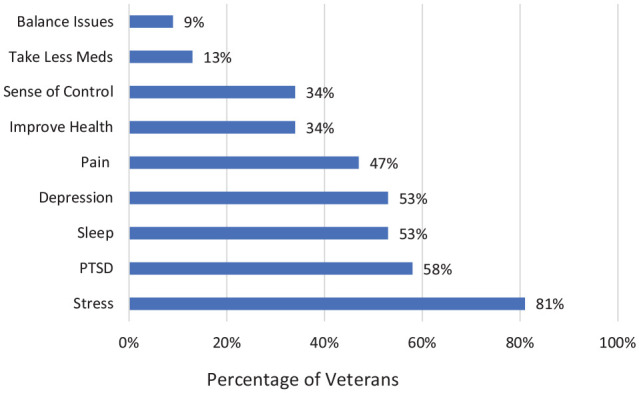

Figure 1 presents participants’ reported reasons for using mindfulness, in which the top four reasons were to help manage stress, PTSD, depression, and sleep. Table 2 presents the data regarding the extent to which participants perceived mindfulness was helpful. Response options were “not at all, a little, some, quite a bit, or a lot.” Regarding stress, 98% Veterans said it helped them at least a little; 79% said that mindfulness helped them, at least a little, with pain and PTSD; and 95% said that mindfulness helped them, at least a little, with depression, while 93% said that mindfulness helped them, at least a little, with sleep.

Figure 1.

Reasons for using mindfulness in the past year (n = 53).

Table 2.

How did mindfulness help you with your concerns?

| Reason for using mindfulness | Not at all, n (%) | A little, n (%) | Some, n (%) | Quite a bit, n (%) | A lot, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain (n = 42) | 9 (21) | 8 (19) | 9 (21) | 12 (29) | 4 (10) |

| Improve health (n = 39) | 4 (10) | 6 (15) | 9 (23) | 16 (41) | 4 (10) |

| Stress (n = 47) | 1 (2) | 5 (11) | 14 (30) | 16 (34) | 11 (23) |

| Take less medicines (n = 36) | 17 (47) | 7 (19) | 6 (17) | 4 (11) | 2 (6) |

| Sleep (n = 46) | 3 (7) | 10 (22) | 11 (24) | 15 (33) | 7 (15) |

| Depression (n = 43) | 2 (5) | 6 (14) | 14 (33) | 17 (40) | 4 (9) |

| PTSD (n = 44) | 9 (21) | 5 (11) | 7 (16) | 15 (34) | 8 (18) |

| Balance issues (n = 34) | 17 (50) | 5 (15) | 3 (9) | 6 (18) | 3 (9) |

| Sense of control (n = 38) | 10 (26) | 6 (16) | 7 (18) | 11 (29) | 4 (11) |

PTSD: posttraumatic stress disorder.

Subjective rating scale: 1 = not at all, 2 = a little, 3 = some, 4 = quite a bit, 5 = a lot.

With respect to frequency of mindfulness practice and the perception of benefit, a one-way ANOVA revealed that frequency of practice (almost every day, a few times per month, or a few times per year) was not associated with perceived effectiveness for any clinical condition. Then we examined whether the type of mindfulness practice (VA group, Internet, or self-practice) was related to perceived benefit. For individuals using mindfulness to “improve health,” those who attended a VA group (n = 27; M = 3.67; SD = .83) versus those that did not (n = 12; M = 2.33; SD = 1.30) reported a significantly greater perceived benefit, t(37) = 3.861, p = .000. Similarly, for individuals using mindfulness for PTSD, those who attended a VA group (n = 31; M = 3.55; SD = 1.15) versus those that did not (n = 13; M = 2.31; SD = 1.65) reported greater perceived benefit, t(42) = 2.4681, p = .024. Participants with all other clinical conditions did not report greater perceived benefit from practicing mindfulness via VA group, Internet, or self-practice.

Interest, perceptions, and beliefs about mindfulness

One hundred and twenty-two (78%) participants reported that they would be interested in learning more about mindfulness, while 34 (22%) said that they were not interested. Table 3 presents the findings from the question “What would help you gain more interest in Mindfulness?” The top four answers were (1) knowing how mindfulness could help me, (2) knowing what mindfulness is, (3) combining mindfulness with a pleasurable activity like hiking or sailing, (4) trying it out, and (5) seeing research that supports how it helps. Veterans answered, in their own words, that they are looking for help with weight control and enjoy groups with horses and rock climbing. In addition, the survey asked, “When thinking about taking a mindfulness class, which of the following beliefs apply to you?.” Table 4 presents their answers, of which the top three were (1) It’s about clearing the mind, (2) I don’t know what it is, and (3) It’s something that can help me. When asked to comment using their own words, Veterans reported that it helps them with training the mind, managing pain, focus and self-control, being present, relaxing, as well as finding serenity and peace. Pearson’s chi-square tests of independence showed that demographic variables were not associated with wanting to learn more about mindfulness.

Table 3.

What would help you gain more interest in mindfulness? (n = 176).

| Knowing what mindfulness is | 55% |

| Knowing how it could help me | 58% |

| Trying it out | 32% |

| Seeing research that supports how it could help me | 31% |

| No interest, just don’t care | 6% |

| Combining mindfulness with a pleasurable activity like hiking or sailing | 43% |

| Free text comments: “Looking for groups on self-help,” “Combining mindfulness with rock climbing and equine therapy,” “Combining mindfulness with weight control class.” |

11% |

Table 4.

When thinking about taking a mindfulness class, which of the following beliefs apply to you? (n = 164).

| I don’t know what it is | 40% |

| It’s only for Buddhists | 1% |

| It’s about clearing the mind | 45% |

| It’s something that can help me | 38% |

| It doesn’t “work” | 1% |

| It’s for “hippies” | 4% |

| I don’t have time | 4% |

| I don’t see how it could help me | 2% |

| I don’t like taking classes or being in groups | 6% |

| I have already taken a mindfulness course and do not want to pursue further courses | 4% |

| It’s too difficult | 2% |

| Free text comments: “It’s about training how I think,” “Help with pain,” “Serenity with ourselves,” “For self-control,” “To relax,” “It’s about being in the moment,” “Being aware of my surroundings,” “My overall stress level, how I am reacting to my current environment,” “I think every vet should understand and realize and get help or relief with it,” “Being more cognizant,” “My ADHD kicks in when I am trying to do it,” “Excellent source for focus and peace,” “It’s about paying attention, on purpose without judgement,” “I love mindfulness and it’s just what I needed,” “I struggle to meditate.” |

17% |

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to specifically focus on Veterans’ interests in, perceptions about, and usage of mindfulness. Furthermore, it is only the third to investigate attitudes about any CIH interventions among Veterans, and one of only a few investigating any population. The information reported herein provides new insights into how best to meet their needs, appeal to their interests, and therefore, engage them in practicing mindfulness.

The approach to Veterans regarding engagement in MBIs may vary depending on their knowledge level and whether they are current mindfulness practitioners. The first key finding of this study was that over half of respondents reported perceiving that they knew what mindfulness was about. To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate this question among Veterans and indicates a need to provide basic education about mindfulness to this population as over 40% were unfamiliar. In addition, 45% of respondents indicated they thought mindfulness was about “clearing the mind,” which suggests that those who thought that they understood mindfulness, may have an incomplete understanding. Regarding current practice, 30% reported practicing mindfulness within the past year, which is greater than the 17.6% reported in the national Veteran study.46 The only other study, Held et al.48 reported that 61% practiced either meditation, yoga, breathing, or qigong in the past or currently. While additional studies are needed, these findings indicate that engagement strategies should focus on providing basic education about mindfulness. However, it is encouraging that more than a quarter of Veterans currently practice mindfulness, and this suggests that providing maintenance groups, where Veterans can practice their meditation skills with others, might serve this subpopulation well.

In addition to knowing what mindfulness is about, additional important information needed to guide the process of engaging Veterans in MBIs, is knowledge of their attitudes and perceptions regarding mindfulness. Thirty-eight percent indicated that they believed mindfulness can help them, and only 10% of respondents indicated a negative belief or opinion about mindfulness. These findings further guide educational engagement approaches as these results suggest that there is minimal need to address potential negative beliefs about mindfulness, but rather indicate that the focus of education should be on the benefits of a mindfulness practice.

The overarching aim of teaching Veterans about, and how to practice mindfulness, is to encourage the development of a self-sustaining community-based practice. To investigate whether this was occurring, we asked about location and frequency of those with a current mindfulness practice. We found that of those currently practicing mindfulness, 41% and 78% reported practicing outside the VA in our study and the national survey, respectively.46 In addition, almost 20% reported using an Internet application to practice mindfulness in our study. For those who practiced mindfulness within the last year, 53% reported practicing mindfulness almost every day or a few times per week, compared with 28% in the national Veteran survey.46 Further investigation will be necessary to disambiguate these disparate findings. However, our results suggest that a significant minority of Veterans in our catchment area have a self-sustaining community-based practice.

To determine whether certain sub-populations are less likely to engage in mindfulness, we assessed for correlations between demographic variables and knowing what mindfulness is about, being aware of mindfulness interventions offered at the local VA facility, or using mindfulness in the past year. We found no such associations, however, the national Veteran study reported higher utilization of mindfulness among females, Hispanics, unmarried, and those aged 35–49 years.46 Disparate results may be due to differences in sample size, race, ethnicity, and gender in the populations studied. Future research is needed to determine whether some demographic groups are less likely to engage in mindfulness and will need specifically targeted education and outreach efforts.

Stress was the number one reason for using mindfulness in the current and national studies, followed by depression, PTSD, and sleep in this current study. The majority of those who practiced for these reasons reported perceived benefit in both studies as well. In addition, we found that the format for practice (VA group, Internet, or self-practice) was related to perceived benefit. There was greater perceived benefit found among those who attended a VA mindfulness group to “improve health or a sense of control over my health” compared with those who did not attend a VA group for those concerns, in both studies, and similarly for PTSD in our study. However, frequency of practice was not associated with perceived benefit. These are compelling findings that will need to be examined further through additional studies. Data are lacking on whether perceived benefit is associated with actual benefit, such as symptom reduction. Also, it may be fruitful to determine whether specific factors are associated with the perception of benefit, such as having the class facilitated in-person and/or the impact of practicing with other Veterans.

Regarding perceived barriers to mindfulness practice, the most common responses indicated class schedules were not workable for Veteran’s schedule, lack of personal time, difficulty practicing meditation and distance from the facility. Finally, 60% of the participants in this study were unaware of mindfulness classes being offered at the local VA facility. Similarly, almost 60% in the national VHA study did not know if the VA offered mindfulness.46 Martinez et al.58 reported similar challenges in a study examining MBSR use among Veterans. They reported perceived barriers to enrollment were lack of time, scheduling difficulties, commute anxiety, and among women, aversion to mixed gender groups. Perceived barriers to course completion were difficulty understanding the purpose of MBSR practices and negative reactions to others.58 Taken together, these studies indicate that Veteran engagement in MBIs might be enhanced by offering classes on evenings and weekends, providing gender specific classes as well as providing virtual offerings into Veteran’s homes. Education about mindfulness classes offered at the facility is also needed. Finally, the perceived difficulty practicing meditation might be addressed in general education efforts directed at all Veterans as well as in MBI classes.

Perhaps the most important finding of the study was that 78% of participants reported that they would be interested in learning more about mindfulness. More than half wanted to know what it is and how it could help them. Almost half were interested in combining mindfulness with a pleasurable activity like hiking or sailing. These results further support the utilization of basic education about mindfulness and its benefits. More importantly, it suggests that many Veterans have an interest in mindfulness and outreach/education efforts are likely to be successful and are therefore warranted. These findings also suggest that outreach/education may benefit from including an experiential component and the development of interventions combining mindfulness training with a pleasurable activity. The authors of this report have developed a model intervention that combines mindfulness training with recreational sailing,50 which could be used as a template for other such programs using other activities.

There are limitations in this study that warrant mentioning. The first limitation was the relatively small sample size, which was based on practical data collection considerations instead of a power calculation to detect statistically significant effects. Since this was the first study to specifically focus on Veterans’ perceptions, interests, and usage of MBIs, the literature in this area did not provide us with a clear estimate of effect sizes we should expect to find. Second, the use of a random convenience sample introduces the potential for selection or sampling bias. Third, this unprecedented data were collected using an unvalidated survey questionnaire that included some check box driven answers, which limits the conclusions about what respondents were thinking. Future studies could use focus groups to further elucidate Veterans’ perspectives about, interests in, and usage of mindfulness. Finally, this population differs from a wider population, thus replication of these results across multiple facilities and regions within the VHA system, would allow for generalization to the greater population.

Conclusion

This is the first study to focus specifically on examining Veterans’ interests in, perceptions about, and usage of mindfulness. It addresses important information needed to guide the process of educating them about and engaging them in MBIs. Despite the low to moderate usage of mindfulness among Veterans, there is strong perceived benefit from usage, strong interest in learning about MBIs, and minimal negative beliefs, which indicates that educational outreach efforts are likely to be successful.

Findings indicate that educational outreach approaches should focus on the benefits of mindfulness practice for stress, PTSD, sleep, and depression, with minimal need to address negative beliefs. Furthermore, educational offerings should include an experiential component. Finally, engagement in MBIs may be enhanced by combining mindfulness training with a pleasurable activity, offering evening, weekend and individual sessions, as well as providing virtual offerings into Veteran’s homes.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, COREQ_Checklist_SAGEedits for Veterans’ interests, perceptions, and use of mindfulness by Tracy Herrmann, William R Marchand, Brandon Yabko, Ryan Lackner, Julie Beckstrom and Ashley Parker in SAGE Open Medicine

Supplemental material, Mindfulness_Survey_questionnaire_SAGEedits for Veterans’ interests, perceptions, and use of mindfulness by Tracy Herrmann, William R Marchand, Brandon Yabko, Ryan Lackner, Julie Beckstrom and Ashley Parker in SAGE Open Medicine

Acknowledgments

This study was unfunded. However, the work was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs VISN 19 Whole Health Flagship Site located at the George E. Wahlen VAMC in Salt Lake City, Utah.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Dr Marchand receives royalties from two books that discuss mindfulness.

Ethics approval: This research study was exempt from ethics oversight because no contact was made with participants, no personal or confidential information was collected, no charts or records were reviewed from participants, and no waiver number was provided.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Informed consent: This research study was exempt from the IRB consent process as no personal or confidential information was collected on participants, no charts or records were reviewed.

Trial registration: This study was not a clinical trial.

ORCID iD: Tracy Herrmann  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6229-6025

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6229-6025

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Kabat-Zinn J. Wherever you go, there you are: Mindfulness meditation in everyday life. New York: Hyperion, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Davidson RJ, Kabat-Zinn J, Schumacher J, et al. Alterations in brain and immune function produced by mindfulness meditation. Psychosom Med 2003; 65(4): 564–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bohlmeijer E, Prenger R, Taal E, et al. The effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction therapy on mental health of adults with a chronic medical disease: a meta-analysis. J Psychosom Res 2010; 68(6): 539–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Niazi AK, Niazi SK. Mindfulness-based stress reduction: a non-pharmacological approach for chronic illnesses. N Am J Med Sci 2011; 3(1): 20–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hempel S, Taylor SL, Marshall NJ, et al. Evidence map of mindfulness. VA Evidence-based Synthesis Program Reports. VA Health Care, Washington, DC, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hofmann SG, Sawyer AT, Witt AA, et al. The effect of mindfulness-based therapy on anxiety and depression: a meta-analytic review. J Consult Clin Psychol 2010; 78(2): 169–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jain S, Shapiro SL, Swanick S, et al. A randomized controlled trial of mindfulness meditation versus relaxation training: effects on distress, positive states of mind, rumination, and distraction. Ann Behav Med 2007; 33(1): 11–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Piet J, Hougaard E. The effect of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for prevention of relapse in recurrent major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 2011; 31(6): 1032–1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ma SH, Teasdale JD. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression: replication and exploration of differential relapse prevention effects. J Consult Clin Psychol 2004; 72(1): 31–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kuyken W, Byford S, Taylor RS, et al. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy to prevent relapse in recurrent depression. J Consult Clin Psychol 2008; 76(6): 966–978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. King AP, Erickson TM, Giardino ND, et al. A pilot study of group mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) for combat Veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Depress Anxiety 2013; 30(7): 638–645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kearney DJ, McDermott K, Malte C, et al. Association of participation in a mindfulness program with measures of PTSD, depression and quality of life in a veteran sample. J Clin Psychol 2012; 68(1): 101–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cramer H, Haller H, Lauche R, et al. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for low back pain. A systematic review. BMC Complement Altern Med 2012; 12: 162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Grossman P, Tiefenthaler-Gilmer U, Raysz A, et al. Mindfulness training as an intervention for fibromyalgia: evidence of postintervention and 3-year follow-up benefits in well-being. Psychother Psychosom 2007; 76(4): 226–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schmidt S, Grossman P, Schwarzer B, et al. Treating fibromyalgia with mindfulness-based stress reduction: results from a 3-armed randomized controlled trial. Pain 2011; 152(2): 361–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Anheyer D, Haller H, Barth J, et al. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for treating low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2017; 166(11): 799–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Keng SL, Smoski MJ, Robins CJ. Effects of mindfulness on psychological health: a review of empirical studies. Clin Psychol Rev 2011; 31(6): 1041–1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Goldin PR, Gross JJ. Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) on emotion regulation in social anxiety disorder. Emotion 2010; 10(1): 83–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Creswell JD, Myers HF, Cole SW, et al. Mindfulness meditation training effects on CD4+ T lymphocytes in HIV-1 infected adults: a small randomized controlled trial. Brain Behav Immun 2009; 23(2): 184–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Witek-Janusek L, Albuquerque K, Chroniak KR, et al. Effect of mindfulness based stress reduction on immune function, quality of life and coping in women newly diagnosed with early stage breast cancer. Brain Behav Immun 2008; 22(6): 969–981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Grossman P, Niemann L, Schmidt S, et al. Mindfulness-based stress reduction and health benefits. A meta-analysis. J Psychosom Res 2004; 57(1): 35–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cahn BR, Polich J. Meditation states and traits: EEG, ERP, and neuroimaging studies. Psychol Bull 2006; 132(2): 180–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wielgosz J, Goldberg SB, Kral TRA, et al. Mindfulness meditation and psychopathology. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2019; 15: 285–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Goldberg SB, Tucker RP, Greene PA, et al. Mindfulness-based interventions for psychiatric disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 2018; 59: 52–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. King AP, Block SR, Sripada RK, et al. A pilot study of mindfulness-based exposure therapy in OEF/OIF combat Veterans with PTSD: altered medial frontal cortex and amygdala responses in social-emotional processing. Front Psychiatry 2016; 7: 154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Stephenson KR, Simpson TL, Martinez ME, et al. Changes in mindfulness and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms among Veterans enrolled in mindfulness-based stress reduction. J Clin Psychol 2017; 73(3): 201–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rice VJ, Liu B, Schroeder PJ. Impact of in-person and virtual world mindfulness training on symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder and attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder. Mil Med 2018; 183(Suppl. 1): 413–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jasbi M, Sadeghi Bahmani D, Karami G, et al. Influence of adjuvant mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) on symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in Veterans—results from a randomized control study. Cogn Behav Ther 2018; 47(5): 431–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Serpa JG, Taylor SL, Tillisch K. Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) reduces anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation in Veterans. Med Care 2014; 52(12 Suppl. 5): S19–S24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Arefnasab Z, Babamahmoodi A, Babamahmoodi F, et al. Mindfulness-based Stress Reduction (MBSR) and its effects on psychoimmunological factors of chemically pulmonary injured Veterans. Iran J Allergy Asthma Immunol 2016; 15(6): 476–486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wahbeh H, Goodrich E, Goy E, et al. Mechanistic pathways of mindfulness meditation in combat Veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychol 2016; 72(4): 365–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Heffner KL, Crean HF, Kemp JE. Meditation programs for Veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder: aggregate findings from a multi-site evaluation. Psychol Trauma 2016; 8(3): 365–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Schure MB, Simpson TL, Martinez M, et al. Mindfulness-based processes of healing for Veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. J Altern Complement Med 2018; 24(11): 1063–1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Harding K, Simpson T, Kearney DJ. Reduced symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder and irritable bowel syndrome following mindfulness-based stress reduction among Veterans. J Altern Complement Med 2018; 24(12): 1159–1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Polusny MA, Erbes CR, Thuras P, et al. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for posttraumatic stress disorder among Veterans: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2015; 314(5): 456–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bergen-Cico D, Possemato K, Pigeon W. Reductions in cortisol associated with primary care brief mindfulness program for Veterans with PTSD. Med Care 2014; 52(12 Suppl. 5): S25–S31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Cole MA, Muir JJ, Gans JJ, et al. Simultaneous treatment of neurocognitive and psychiatric symptoms in Veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder and history of mild traumatic brain injury: a pilot study of mindfulness-based stress reduction. Mil Med 2015; 180(9): 956–963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hull A, Reinhard M, McCarron K, et al. Acupuncture and meditation for military Veterans: first steps of quality management and future program development. Glob Adv Health Med 2014; 3(4): 27–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bremner JD, Mishra S, Campanella C, et al. A pilot study of the effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms and brain response to traumatic reminders of combat in operation enduring freedom/operation Iraqi freedom combat Veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. Front Psychiatry 2017; 8: 157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Colgan DD, Wahbeh H, Pleet M, et al. A qualitative study of mindfulness among Veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder: practices differentially affect symptoms, aspects of well-being, and potential mechanisms of action. J Evid Based Complementary Altern Med 2017; 22(3): 482–493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. DiNardo M, Saba S, Greco CM, et al. A mindful approach to diabetes self-management education and support for Veterans. Diabetes Educ 2017; 43(6): 608–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kluepfel L, Ward T, Yehuda R, et al. The evaluation of mindfulness-based stress reduction for Veterans with mental health conditions. J Holist Nurs 2013; 31(4): 248–255; quiz 256–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kline A, Chesin M, Latorre M, et al. Rationale and study design of a trial of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for preventing suicidal behavior (MBCT-S) in military Veterans. Contemp Clin Trials 2016; 50: 245–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. King AP, Block SR, Sripada RK, et al. Altered default mode network (DMN) resting state functional connectivity following a mindfulness-based exposure therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in combat Veterans of Afghanistan and Iraq. Depress Anxiety 2016; 33(4): 289–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Marchand WR, Yabko B, Herrmann T, et al. Treatment engagement and outcomes of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for Veterans with psychiatric disorders. J Altern Complement Med 2019; 25(9): 902–909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Goldberg S, Zeliadt SB, Hoggatt KJ, et al. Utilization and perceived effectiveness of mindfulness meditation in Veterans: results from a national survey. Mindfulness 2019; 10: 2596–2605. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Taylor SL, Hoggatt KJ, Kligler B. Complementary and integrated health approaches: what do Veterans use and want. J Gen Intern Med 2019; 34(7): 1192–1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Held RF, Santos S, Marki M, et al. Veteran perceptions, interest, and use of complementary and alternative medicine. Fed Pract 2016; 33(9): 41–47. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Possemato K, Bergen-Cico D, Treatman S, et al. A randomized clinical trial of primary care brief mindfulness training for Veterans with PTSD. J Clin Psychol 2016; 72(3): 179–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Marchand WR, Klinger W, Block K, et al. Safety and psychological impact of sailing adventure therapy among Veterans with substance use disorders. Complement Ther Med 2018; 40: 42–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Buckley RC, Brough P. Nature, eco, and adventure therapies for mental health and chronic disease. Front Public Health 2017; 5: 220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Seymour V. The human-nature relationship and its impact on health: a critical review. Front Public Health 2016; 4: 260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Pretty J, Rogerson M, Barton J. Green mind theory: how brain-body-behaviour links into natural and social environments for healthy habits. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2017; 14(7): 706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Van Gordon W, Shonin E, Richardson M. Mindfulness and nature. Mindfulness 2018; 9(5): 1655–1658. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kachan DOH, Tannenbaum SL, Annane DW, et al. Prevalence of mindfulness practices in the US Workforce: National Health Interview Survey. Prev Chronic Dis 2017; 14: 160034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Szanton SLWJ, Connolly AB, Piferi RL. Examining mindfulness-based stress reduction: perception from minority older adults residing in a low-income housing facility. BMC Complement Altern Med 2011; 11: 44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Burke A, Lam CN, Stussman B, et al. Prevalence and patterns of use of mantra, mindfulness and spiritual meditation among adults in the United States. BMC Complement Altern Med 2017; 17(1): 316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Martinez ME, Kearney DJ, Simpson T, et al. Challenges to enrollment and participation in mindfulness-based stress reduction among Veterans: a qualitative study. J Altern Complement Med 2015; 21(7): 409–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, COREQ_Checklist_SAGEedits for Veterans’ interests, perceptions, and use of mindfulness by Tracy Herrmann, William R Marchand, Brandon Yabko, Ryan Lackner, Julie Beckstrom and Ashley Parker in SAGE Open Medicine

Supplemental material, Mindfulness_Survey_questionnaire_SAGEedits for Veterans’ interests, perceptions, and use of mindfulness by Tracy Herrmann, William R Marchand, Brandon Yabko, Ryan Lackner, Julie Beckstrom and Ashley Parker in SAGE Open Medicine