Abstract

Background

Chenopodium quinoa Willd. (quinoa) is a pseudocereal crop of the Amaranthaceae family and represents a promising species with the nutritional content and high tolerance to stressful environments, such as soils affected by high salinity. The basic leucine zipper (bZIP) transcription factor represents exclusively in eukaryotes and can be related to many biological processes. So far, the genomes of quinoa and 3 other Amaranthaceae crops (Spinacia oleracea, Beta vulgaris, and Amaranthus hypochondriacus) have been fully sequenced. However, information about the bZIPs in these Amaranthaceae species is limited, and genome-wide analysis of the bZIP family is lacking in quinoa.

Results

We identified 94 bZIPs in quinoa (named as CqbZIP1-CqbZIP94). All the CqbZIPs were phylogenetically splitted into 12 distinct subfamilies. The proportion of CqbZIPs was different in each subfamily, and members within the same subgroup shared conserved exon-intron structures and protein motifs. Besides, 32 duplicated CqbZIP gene pairs were investigated, and the duplicated CqbZIPs had mainly undergone purifying selection pressure, which suggested that the functions of the duplicated CqbZIPs might not diverge much. Moreover, we identified the bZIP members in 3 other Amaranthaceae species, and 41, 32, and 16 orthologous gene pairs were identified between quinoa and S. oleracea, B. vulgaris, and A. hypochondriacus, respectively. Among them, most were a single copy being present in S. oleracea, B. vulgaris, and A. hypochondriacus, and two copies being present in allotetraploid quinoa. The function divergence within the bZIP orthologous genes might be limited. Additionally, 11 selected CqbZIPs had specific spatial expression patterns, and 6 of 11 CqbZIPs were up-regulated in response to salt stress. Among the selected CqbZIPs, 3 of 4 duplicated gene pairs shared similar expression patterns, suggesting that these duplicated genes might retain some essential functions during subsequent evolution.

Conclusions

The present study provided the first systematic analysis for the phylogenetic classification, motif and gene structure, expansion pattern, and expression profile of the bZIP family in quinoa. Our results would lay an important foundation for functional and evolutionary analysis of CqbZIPs, and provide promising candidate genes for further investigation in tissue specificity and their functional involvement in quinoa’s resistance to salt stress.

Keywords: Quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa), bZIP transcription factor family, Phylogenetic classification, Evolutionary analysis, Gene expression patterns

Background

Quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.) is a halophytic pseudocereal crop that originated from the Andean region of South America [1]. It is an allotetraploid (2n = 4x = 36) with an estimated genome size of approximately 1.5 Gbp. Quinoa belongs to the Amaranthaceae family, which also includes other economically important crops such as Spinacia oleracea (spinach, 2n = 2x = 12), Beta vulgaris (sugar beet, 2n = 2x = 18), and Amaranthus hypochondriacus (amaranth, 2n = 2x = 32) [2]. Quinoa produces better nutritious grains than any other major cereals [3, 4], and displays high tolerance to adverse climatic and soil conditions such as drought, soil salinity, and frost, which make it a favorable candidate for agronomic expansion into marginal lands and for identification of candidate genes facilitating stress tolerance [1, 5–7]. The potential of this emerging crop was recognized by the United Nations when 2013 was declared the International Year of Quinoa [6, 7]. To expand quinoa production worldwide and accelerate the improvement of quinoa, increasing researchers have devoted into the study of quinoa, and a draft of the C. quinoa genome sequence was reported recently [7], which provided the foundation for accelerating the genetic improvement of the crop and enhanced global food security for a growing world population.

Transcription factors (TFs) play vital roles in almost all plant biological processes. They are key regulators of numerous signaling networks in response to plant growth and development as well as to environmental stresses through binding to promoter and/or enhancer regions of corresponding genes to activate or repress transcription of downstream target genes [8–10]. Among several TF families that present exclusively in eukaryotes, the basic leucine zipper (bZIP) family is one of the largest and most diverse families [10–12]. The bZIP TFs contain a highly conserved bZIP domain which is composed of two structural features, a highly conserved basic region and a less conserved leucine zipper. The basic region consists of 16 amino acid residues with an invariant N-× 7-R/K motif, and is responsible for DNA binding and nuclear localization specifically. The leucine zipper includes a heptad repeat of leucines or other bulky hydrophobic amino acids for specific recognition and dimerization [10–14].

In plants, there is considerable evidence showing that bZIP TFs play crucial roles in various aspects of biological processes such as embryogenesis [15], seed maturation [16, 17], and flower and vascular development [18, 19]. On the other hand, bZIP proteins also take part in the regulation of signalling and responses to abiotic/biotic stimuli, including high salinity, drought, osmotic, cold stresses, and pathogen defense [10–12, 20]. Thus, bZIP TFs are important for plants to withstand various environmental stresses, such as salt-affected soils. Soil salinization is an increasingly serious problem, causing huge economic loss in agricultural production globally. Since quinoa can grow under harsh soil conditions and show high tolerance to salt [6, 21, 22], the crop can serve as a valuable donor of salt-tolerant genes to other crops [6].

Members of the bZIP TF family have been comprehensively identified or predicted in many eukaryotic genomes [10, 20, 23–26]. However, to our knowledge, no bZIP genes have been identified and isolated in quinoa so far. With quinoa genome sequencing completed, a genome-wide overview of the bZIP family in quinoa is urgently required. In this study, putative bZIPs were identified in quinoa. We conducted a relatively detailed study on the phylogenetics, gene structure, protein motif, genomic location, expansion pattern, and expression profile to evaluate the molecular evolution and biological function of the bZIP family in quinoa.

Results

Genomic identification and characterization of putative bZIPs

A total of 94 bZIP genes were confirmed and identified in quinoa (Additional file 1), and we designated these genes as CqbZIPs, from CqbZIP1 to CqbZIP94. The primary and secondary protein structures of 94 CqbZIPs were deduced from their protein sequences (Additional file 1). The protein structures were highly diverse in all the identified CqbZIPs, and the amino acid numbers of proteins varied from 92 (CqbZIP31) to 821 (CqbZIP86), with the predicted molecular weight ranging from 10.8 kDa (CqbZIP31) to 91.6 kDa (CqbZIP86). The isoelectric points ranged from 4.38 (CqbZIP81) to 10.37 (CqbZIP42). Besides, we identified 54, 48, and 49 bZIP genes in S. oleracea, B. vulgaris, and A. hypochondriacus, respectively, and denoted them as SobZIPs, BvbZIPs, and AhbZIPs, respectively (Additional file 2).

Phylogenetic analysis

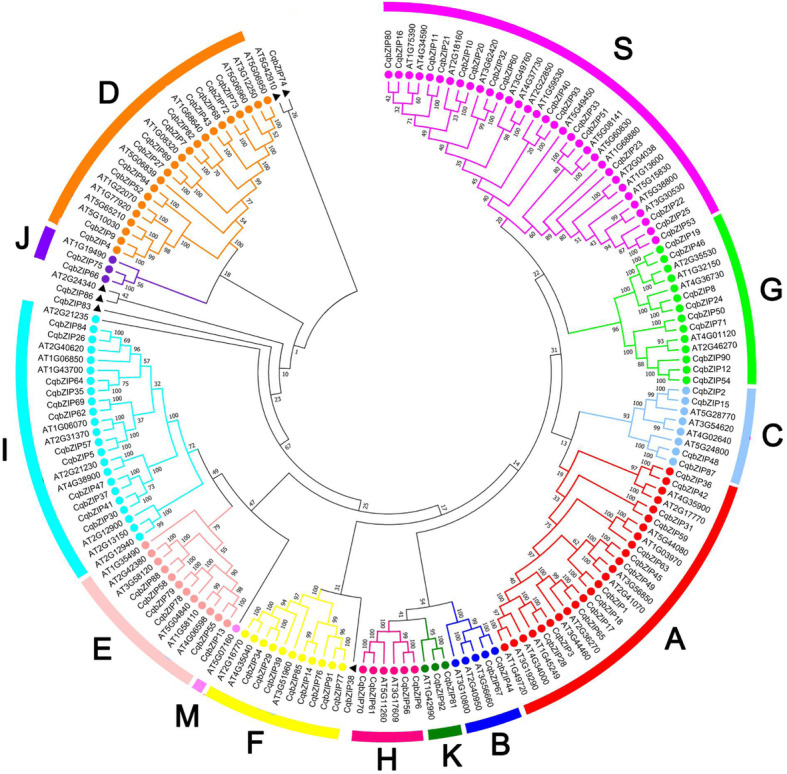

To determine the evolutionary relationships of bZIPs in quinoa, phylogenetic trees were constructed with the 94 CqbZIP proteins and the known bZIPs from Arabidopsis (Figs. 1 and 2a, Additional file 3).

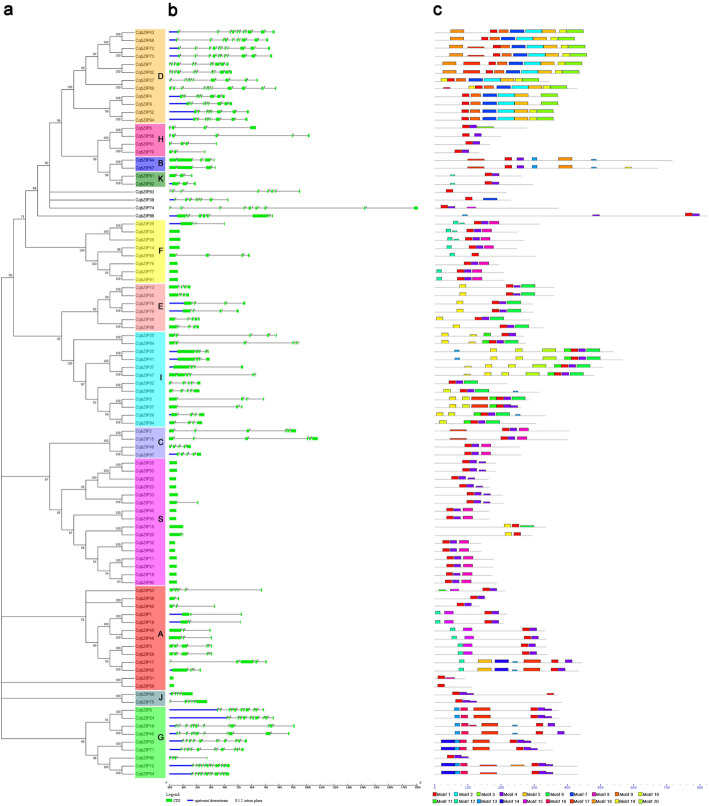

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic relationships of the bZIP family in quinoa and Arabidopsis. The neighbor-joining tree was generated through the MEGA7 program based on multiple alignments with ClustalX. The subfamilies are labeled and denoted by different colors and the numbers in the clades are posterior probability values

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic relationships (a), gene structures (b), and motif compositions (c) of bZIPs in quinoa. Gene structure dynamics of CqbZIPs were predicted with the GSDS software. The exons are represented by green boxes and the introns are indicated by black lines. The conserved motifs were scanned with MEME. Different motifs are represented by various colored boxes

According to the previous classification system [14], the CqbZIP family was divided into 12 subfamilies (Subfamily A to K, and S), and the member proportion was different in each subfamily (Additional file 4a). The Subfamily S (17%) had the most genes, followed by Subfamily A (14%), Subfamily D (13%), and Subfamily I (13%). Subfamily B (2%), Subfamily J (2%), and Subfamily K (2%) contained the least members. Besides, the bZIPs in spinach, sugar beet, and amaranth were phylogenetically classified (Additional file 5), and a similar member distribution in each subfamily was found in each plant (Additional file 4b-d).

Gene structures and protein motifs of CqbZIPs

Gene structure and intron phase were investigated in the CqbZIP family (Fig. 2b). Result indicated that most of CqbZIPs (72 of 94 CqbZIPs) had introns, and the numbers of introns varied from 1 to 11. Subfamily A, B, C, E, F, H, I, J, K, and S contained 0–5 introns, whereas Subfamily D and G had 7–11 introns, except for CqbZIP90. Generally, most of CqbZIP genes in the same subgroups showed a similar exon-intron structure, and the intron patterns, formed by relative position and phase, were highly conserved within each phylogenetic subgroup.

In total, 20 conserved motifs, including the bZIP domain, were identified in the CqbZIP proteins and their multilevel consensus amino acid sequences of motifs are listed in Additional file 6. The motif distribution corresponding to the phylogenetic tree of CqbZIP gene family is displayed in Fig. 2c. All the CqbZIPs had Motif 1, which represented the basic region and the hinge of the bZIP domain, whilst Motif 4 and 9 corresponded to the variable motifs in the leucine zipper region across the bZIP family. For example, motif 9 only appeared in Subfamily D, while motif 4 almost appeared in the other subgroups. Moreover, some subfamily-specific motifs were identified. For instance, Motif 16 were only present in Subfamily G, Motif 15 only existed in Subfamily A, Motif 11 and 20 were only present in Subfamily I, and Motif 2, 7, and 9 only existed in Subfamily D.

Genomic locations and gene duplications of CqbZIPs

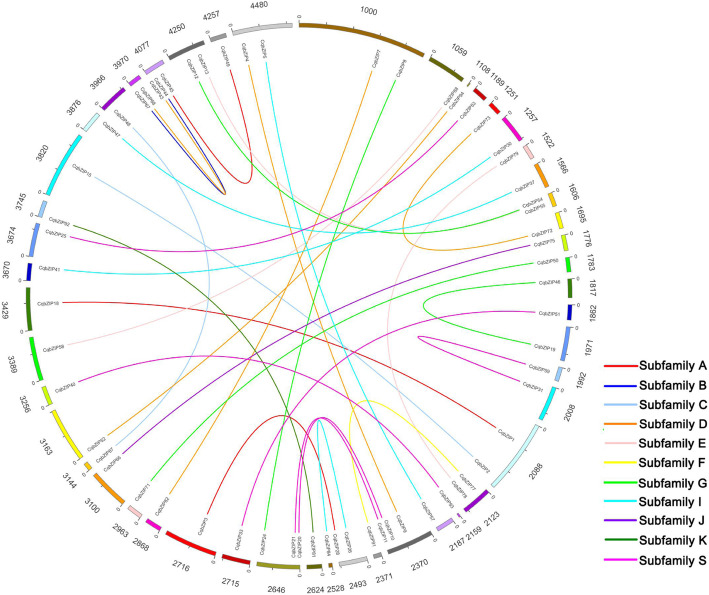

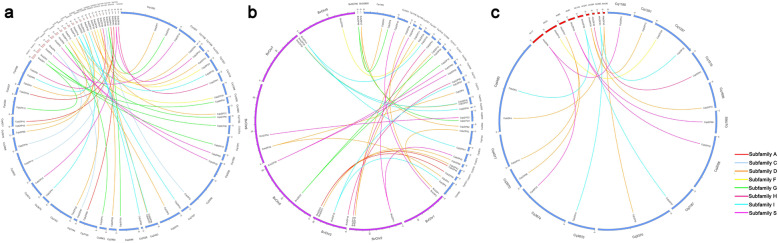

The genomic locations of 94 CqbZIPs were displayed in Additional file 7. Besides, to illustrate the expansion patterns of CqbZIPs, gene duplication events were investigated in the present study. As shown in Fig. 3, 32 duplicated CqbZIP gene pairs were identified, and the duplication events were concentrated in S, D, A, G, and I subgroups. In addition, the Ka/Ks ratios calculated for all the 32 duplicated CqbZIP gene pairs were less than 1 (Table 1). Moreover, orthologous relationships of bZIPs between quinoa and 3 other Amaranthaceae plants were analyzed, 41, 32, and 16 orthologous gene pairs were identified between quinoa and spinach, sugar beet, and amaranth, respectively (Fig. 4, Additional file 8). Among them, 17 SobZIPs, 13 BvbZIPs, and 7 AhbZIPs had 2 bZIP orthologs in quinoa. Of the orthologous gene pairs, most were distributed in Subfamily D, S, and I. All the Ka/Ks ratios except for that of CqbZIP72/BvbZIP13 and CqbZIP73/BvbZIP13 were less than 1.

Fig. 3.

Circos diagram of duplicated bZIP gene pairs in quinoa. The numbers displayed outside the track of the plot indicated the scaffold numbers of quinoa. The duplicated gene pairs are joined by lines. The differently colored lines represent the subfamilies within the CqbZIP family

Table 1.

Ka/Ks analysis for duplicated gene pairs of bZIPs in quinoa

| Duplicated gene 1 | Duplicated gene 2 | Subfamily | Ka | Ks | Ka/Ks | Purifing selection |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CqbZIP1 | CqbZIP18 | A | 0.0230 | 0.1145 | 0.2009 | Yes |

| CqbZIP2 | CqbZIP15 | C | 0.0121 | 0.0698 | 0.1734 | Yes |

| CqbZIP3 | CqbZIP28 | A | 0.0064 | 0.1116 | 0.0573 | Yes |

| CqbZIP4 | CqbZIP9 | D | 0.0035 | 0.1050 | 0.0333 | Yes |

| CqbZIP5 | CqbZIP57 | I | 0.0084 | 0.0754 | 0.1114 | Yes |

| CqbZIP7 | CqbZIP82 | D | 0.0141 | 0.0993 | 0.1420 | Yes |

| CqbZIP8 | CqbZIP24 | G | 0.0141 | 0.0641 | 0.2200 | Yes |

| CqbZIP10 | CqbZIP20 | S | 0.0649 | 0.1238 | 0.5242 | Yes |

| CqbZIP11 | CqbZIP21 | S | 0.0241 | 0.1019 | 0.2365 | Yes |

| CqbZIP12 | CqbZIP54 | G | 0.0244 | 0.1018 | 0.2397 | Yes |

| CqbZIP13 | CqbZIP55 | E | 0.0382 | 0.1099 | 0.3476 | Yes |

| CqbZIP19 | CqbZIP46 | G | 0.0096 | 0.0538 | 0.1784 | Yes |

| CqbZIP25 | CqbZIP53 | S | 0.0093 | 0.1369 | 0.0679 | Yes |

| CqbZIP26 | CqbZIP84 | I | 0.0128 | 0.0911 | 0.1405 | Yes |

| CqbZIP30 | CqbZIP41 | I | 0.0098 | 0.1256 | 0.0780 | Yes |

| CqbZIP31 | CqbZIP59 | A | 0.0571 | 0.0874 | 0.6533 | Yes |

| CqbZIP32 | CqbZIP60 | S | 0.0091 | 0.1326 | 0.0686 | Yes |

| CqbZIP33 | CqbZIP51 | S | 0.0588 | 0.2194 | 0.2680 | Yes |

| CqbZIP37 | CqbZIP47 | I | 0.0243 | 0.1185 | 0.2051 | Yes |

| CqbZIP40 | CqbZIP93 | S | 0.0519 | 0.0789 | 0.6578 | Yes |

| CqbZIP43 | CqbZIP68 | D | 0.0072 | 0.0592 | 0.1216 | Yes |

| CqbZIP44 | CqbZIP67 | B | 0.0166 | 0.1091 | 0.1522 | Yes |

| CqbZIP45 | CqbZIP49 | A | 0.0026 | 0.0820 | 0.0317 | Yes |

| CqbZIP48 | CqbZIP87 | C | 0.0273 | 0.1390 | 0.1964 | Yes |

| CqbZIP50 | CqbZIP71 | G | 0.0182 | 0.0954 | 0.1908 | Yes |

| CqbZIP52 | CqbZIP94 | D | 0.0145 | 0.0760 | 0.1908 | Yes |

| CqbZIP58 | CqbZIP88 | E | 0.0185 | 0.0949 | 0.1949 | Yes |

| CqbZIP66 | CqbZIP75 | J | 0.0330 | 0.1386 | 0.2381 | Yes |

| CqbZIP72 | CqbZIP73 | D | 0.0096 | 0.0891 | 0.1077 | Yes |

| CqbZIP77 | CqbZIP91 | F | 0.0264 | 0.0750 | 0.3520 | Yes |

| CqbZIP78 | CqbZIP79 | E | 0.0268 | 0.0398 | 0.6734 | Yes |

| CqbZIP81 | CqbZIP92 | K | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | Yes |

Fig. 4.

Distribution of bZIP orthologous gene pairs between quinoa and spinach (a), sugar beet (b), and amaranth (c). Lines of different colors represent subfamilies within the bZIP family

Expression patterns of CqbZIPs

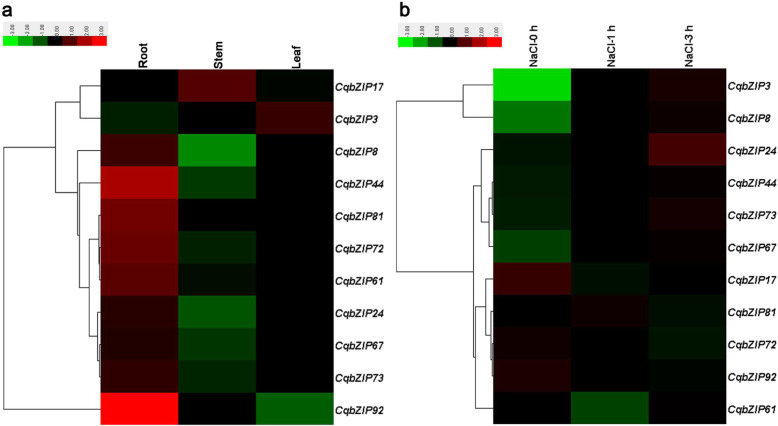

Previous studies have reported that some bZIP genes such as bZIP17 [27, 28], bZIP49 [14], bZIP28 [29], bZIP60 [28, 30], ABF1–4 [14, 31, 32], GBF1 [33], TGAs [34–36], ABI5 [37], and HY5 [38] played a role in plant responses to salt stress as well as other abiotic stresses. In the current study, we investigated the expression patterns of 11 selected CqbZIPs (Fig. 5), which showed high orthology to the bZIPs in Arabidopsis (Fig. 1, Additional file 9). The result demonstrated that these genes showed tissue-specific expression profiles (Fig. 5a). CqbZIP3 was mainly expressed in leaves, while CqbZIP17 exhibited relatively high transcript abundance in young stems. Other genes such as CqbZIP92, CqbZIP44, CqbZIP81, CqbZIP72, and CqbZIP61 were predominantly expressed in roots. Besides, the expression patterns of 11 CqbZIPs in roots of seedlings under salt treatment were investigated (Fig. 5b). The result showed that the expressions of the 11 CqbZIPs were induced or repressed after salt stress. As displayed in Fig. 5b, 6 of 11 CqbZIPs (CqbZIP3, CqbZIP8, CqbZIP24, CqbZIP67, CqbZIP44, and CqbZIP73) were positively responsive to salt stress, while other genes such as CqbZIP17, CqbZIP72, CqbZIP92, and CqbZIP61 showed a decline in expression levels after salt stress. Moreover, the expression profiles of 4 duplicated CqbZIP gene pairs were compared (Additional file 10). Among them, 3 paired genes (CqbZIP44/CqbZIP67, CqbZIP8/CqbZIP24, and CqbZIP81/CqbZIP92) shared similar expression patterns (Additional file 10a-c and e-g), while this was not the case for CqbZIP72/CqbZIP73. The duplicated gene pair displayed reverse expression pattern in response to salt stress (Additional file 10h), and this might be caused by variation in gene regulation.

Fig. 5.

Heat map representation and hierarchical clustering of CqbZIPs across different tissues (a) and in roots under salt stress (b). The color bar represents the relative signal intensity value

Discussion

Quinoa genome is the result of genome fusion between two different doploid parent species of Chenopodium (C. pallidicaule and C. suecicum), each contributing to about half of the genome size [7]. In this study, a complete set of 94 bZIP genes were identified in quinoa, and the size of the genes is similar with that of Arabidopsis (78) [14] and rice (89) [23], but significantly lower that of soybean (160) [39] in which recent whole genome duplication (WGD) events have occurred due to palaeopolyploid, suggesting that besides the genome fusion event that happened around 4.3 million years ago, no other lineage-specific recent WGD were involved in quinoa genome evolution [40]. Besides, the encoded proteins of CqbZIPs showed significant differences in physical and chemical properties (Additional file 1), which were comparable with bZIPs genes from other plant species [23–25].

The bZIP members were also identified in 3 other Amaranthaceae species, and the number of bZIPs in allotetraploid quinoa is almost one-fold higher than that in doploid S. oleracea (54), B. vulgaris (48), and A. hypochondriacus (49) (Additional file 2). Among them, 12 bZIP subfamilies were clustered through phylogenetic analysis (Figs. 1 and 2a, Additional files 2, 3, and 5), and a similar member distribution in each subfamily was found in the 4 Amaranthaceae plants (Additional file 4). Subfamily S contained the most genes, whereas Subfamily B, J, and K had the least bZIPs. However, not all the subgroups were present in each plant. Compared with the members in Arabidopsis, no Subfamily M bZIPs existed in the 4 Amaranthaceae plants, and no Subfamily J bZIPs existed in A. hypochondriacus, suggesting that the evolution of plants not only involves gene retentions, but also is accompanied by gene losses and mutations [41].

The intron-exon pattern carries the imprint of the evolution of a gene family [42–45]. In this study, the number of introns of CqbZIPs varied from 0 to 11 (Fig. 2b, Additional file 3). Most of CqbZIPs (72 of 94 CqbZIPs) contained introns, only 22 of total CqbZIP genes were intronless. Diverse status of exon and intron splicing might be meaningful for CqbZIP gene evolution. Besides, the results showed that exon/intron structures of CqbZIPs were highly conserved within each subgroup, the genes clustered together generally possessed a similar distribution of intronic regions amid the exonic sequences. Morever, Subfamily D and G contained significantly more introns than other subfamilies, and no introns existed in most of subfamily S (14 of 16 members) and subfamily F (6 of 8 members) CqbZIPs, which showed a similar gene structure diversity of bZIPs in other species, such as cassava [20] and six legumes [26].

In this study, 20 distinct conserved motifs were also identified and classified based on sequence similarity of conserved motifs (Fig. 2c). The results indicated that all the CqbZIPs contained typical bZIP domain (Motif 1), and each subfamily had some common motifs while some subfamilies also contained the special motifs. The bZIP domain is the core of the bZIP family, which preferentially binds to the promoter of their downstream target genes on a specific cis- element (e.g. ABREs). The different motif compositions might contribute to the functional diversity of CqbZIP members [25]. Generally, the gene structures and motif distributions were highly conserved within each phylogenetic group, which supports their close evolutionary relationship and the classification of subfamilies.

It has been recognized that gene duplication plays an important role in the genesis of evolutionary novelty and complexity [46, 47]. In this study, gene duplication events were investigated to elucidate the expanded mechanism of the bZIP gene family in quinoa (Fig. 3, Table 1). We identified 32 duplicated CqbZIP gene pairs (Fig. 3), and the Ka/Ks ratios for all the duplicated CqbZIP gene pairs were less than 1 (Table 1), indicating that the CqbZIPs have mainly experienced purifying selection pressure with limited function divergence [41, 48, 49]. Meanwhile, the transcript levels of some duplicated CqbZIPs were also similar in different tissues and roots after salt stress (Additional file 10), which might be related to their highly similar protein architecture and cis-regulatory elements, and the result suggested that these duplicated genes might retain some essential functions during subsequent evolution [50–52].

In the Amaranthaceae family, the genera Chenopodium and Spinacia belong to Chenopoideae, the genus Beta belongs to Betoideae, and the genus Amaranthus belongs to Amaranthoideae [2]. In this study, 41, 32, and 16 CqbZIPs had orthologs in spinach, sugar beet, and amaranth, respectively (Fig. 4, Additional file 8), taking the evolutionary tree (Additional file 11) constructed into consideration, quinoa and spinach bZIPs were phylogenetically closely related compared with sugar beet and amaranth bZIPs, which was in line with expectations [2]. Besides, among the bZIP orthologous genes, most were a single copy being present in doploid spinach, sugar beet, and amaranth, and two copies being present in allotetraploid quinoa (Fig. 4, Additional file 8). The Ka/Ks ratios calculated suggested limited function divergence within the bZIP orthologous genes identified in this study.

As for multigene families, gene expression analysis often provides useful clues for function prediction. The result demonstrated that most of the 11 selected CqbZIPs had specific spatial expression patterns (Fig. 5a), which indicated their important roles in performing diverse developmental and physiological functions in quinoa. Besides, quinoa has been studied as a model to understand salt tolerance in plants, and bZIP genes identified in various plant species have been proven to play crucial roles in salt stress response [53–56]. In the current study, 6 of 11 CqbZIPs, CqbZIP3 (orthologous to ABF1–4), CqbZIP8 (orthologous to GBF1), CqbZIP24 (orthologous to GBF1), CqbZIP67 (orthologous to bZIP17, bZIP49, and bZIP28), CqbZIP44 (orthologous to bZIP17, bZIP49, and bZIP28), and CqbZIP73 (orthologous to TGAs) were positively regulated in response to salt stress (Fig. 5b). Our results provided evidence for selecting candidate genes for further characterization in their functional involvement in plant resistance to salt stress. On the contrary, some CqbZIPs were negatively responsive to salt stress, suggesting that they might be in response to other stresses or participate in other biological processes.

Conclusions

In this report, a total of 94 bZIPs were isolated in quinoa. Comprehensive study of the CqbZIPs provided some important features of the gene family such as phylogenetic classification, expansion pattern, and expression profile. The findings of the present study could broaden our understanding on the molecular evolution and function of the bZIP family in quinoa, and offer a good opportunity to further investigate the bZIP family in plants.

Methods

Genomic identification of bZIP transcription factors

The quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa v1.0) and amaranth (Amaranthus hypochondriacus v1.0) genome databases were obtained from the Phytozome v12 (https://phytozome.jgi.doe.gov/pz/portal.html). The spinach (accession number: PRJNA325593) and sugar beet (accession number: PRJNA268352) genome databases were downloaded from National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). The Arabidopsis bZIP sequences [14] were collected from the Arabidopsis Information Resource (TAIR) (http://www.arabidopsis.org) and were used as queries by searching against the quinoa, spinach, sugar beet, and amaranth genome databases using the BLASTP program with default parameters [57]. Afterward, the bZIP domains were confirmed by the Conserved Domain Database (CDD) program (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/cdd) and Simple Modular Architecture Research Tool (SMART) (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de). Finally, the confident genes were gathered and assigned as bZIP genes for the following analysis. Protein structures of bZIPs in quinoa were predicted with ProtParam (http://web.expasy.org/protparam/) and SOPMA (https://npsa-prabi.ibcp.fr/cgi-bin/npsa_automat.pl?page=/NPSA/npsa_sopma.html) tool.

Phylogenetic classification and structural analysis

All the bZIP sequences identified in this study were aligned using ClustalX version 2.1 [58]. Then, neighbor-joining phylogenetic trees were constructed by MEGA7 (Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis) [59]. Bootstrap analysis was conducted with 1000 replicates to assess the statistical support for each node. The conserved motifs of the bZIP proteins in quinoa were scanned using the online Multiple Em for Motif Elicitation (MEME) program (http://meme-suite.org/tools/meme), parameters were set based on a previous study [41]. To illustrate exon-intron organization for quinoa bZIPs, the Gene Structure Display Server (GSDS) tool (http://gsds.cbi.pku.edu.cn/) was employed by comparing the predicted coding sequences with their corresponding genomic sequences.

Chromosomal mapping and gene duplications

Specific chromosomal positions of the quinoa and amaranth bZIPs were downloaded from the Phytozome database, and the chromosome location information of bZIPs in spinach and sugar beet were searched in NCBI. Duplicated gene pairs were searched via BLASTP and phylogenetic analysis [49], and illustrated with the Circos program [60]. The evolutionary rates, Ka (non-synonymous substitution rate) and Ks (synonymous substitution rate) were estimated by DnaSP v5.0 software [61], and the Ka/Ks ratio was calculated to assess the selection pressure for each duplicated gene pair.

Plant materials, RNA extraction, and quantitative real-time PCR

The white quinoa seeds (ymsBLM-2) were kindly supplied by Maize Research Institute, Shanxi Academy of Agricultural Sciences. Sterilized seeds were cultivated in a growth chamber at controlled conditions (24 °C day/22 °C night, 16 h light/8 h dark). RNA samples were collected from 4 to 5-leaf-stage seedlings. Roots, stems, leaves, and the roots exposed to 300 mM NaCl (salt stress) for 0 h, 1 h, and 3 h were harvested. Afterward, the total RNAs were extracted using an RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (QIAGEN), and preparation of cDNA was performed using SuperScript™ III Reverse Transcriptase kit (Invitrogen). Gene-specific primers were designed (Additional file 12) and then synthesized commercially (HUADA Gene, Beijing, China). Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed with 2× QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR mix (QIAGEN) and ABI ViiA 7 Real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, USA) by strictly following the manufacturer’s instructions. The qRT-PCR machine was set with 40 cycles and an annealing temperature of 60 °C. Relative gene transcript levels were measured as 2−⊿⊿Ct [62], and normalized against Elongation Factor 1 alpha (EF1α) gene transcript levels. Each experiment was repeated in triplicate using independent RNA samples. The expression patterns of the bZIPs in quinoa were clustered using the Cluster 3.0 software [63].

Supplementary information

Additional file 1. The structural analysis of bZIPs identified in this study.

Additional file 2. The bZIPs identified in spinach, sugar beet, and amaranth.

Additional file 3. The classification and gene structures of bZIPs in quinoa.

Additional file 4. The percentage of members in each bZIP subfamily in quinoa, spinach, sugar beet, and amaranth.

Additional file 5. Phylogenetic relationships of the bZIPs in spinach, sugar beet, amaranth, and Arabidopsis.

Additional file 6. Multilevel consensus sequence and their logo of conserved motifs identified in CqbZIP proteins as predicted by MEME program.

Additional file 7. Genomic locations of bZIPs in quinoa.

Additional file 8. Ka/Ks analysis for orthologous bZIP gene pairs between quinoa and spinach, sugar beet, and amaranth.

Additional file 9. Orthology information of CqbZIPs and AtbZIPs from BLASTP.

Additional file 10. Expression patterns of some duplicated CqbZIP genes in different organs and in roots under salt stress treatment.

Additional file 11. Phylogenetic relationships of the bZIPs in quinoa, spinach, sugar beet, and amaranth.

Additional file 12. PCR primers used for qRT-PCR in this study.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Kai Fan (Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University, China) for excellent technical assistance.

Abbreviations

- bZIP

Basic leucine zipper

- TF

Transcription factor

- NCBI

National Center for Biotechnology Information

- TAIR

The Arabidopsis Information Resource

- CDD

Conserved Domain Database

- SMART

Simple Modular Architecture Research Tool

- MEGA

Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis

- MEME

Multiple Em for Motif Elicitation

- GSDS

Gene Structure Display Server

- Ka/Ks

Non-synonymous substitution rate/synonymous substitution rate

- EF1α

Elongation Factor 1 alpha gene

- qRT-PCR

Quantitative real-time PCR

Authors’ contributions

FL and RW conceived and designed research. FL and RW contributed new reagents or analytical tools. FL, JL, XG, and HZ analyzed data. FL, JL, and LY conducted experiments. FL, XG, HZ, and RW contributed to the writing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the Doctoral Scientific Research Foundation of Shanxi Datong University (2017-B-18), Key Research and Development Projects of Agricultural Science and Technology of Datong, Shanxi (2018042) and Shanxi Provincial Program on Key Basic Research Project (201603D221004–5). The funding bodies had no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, and in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The Arabidopsis bZIP protein sequences were collected from the Arabidopsis information source (TAIR) database (http://www.arabidopsis.org). The genome sequences of quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa v1.0) and amaranth (Amaranthus hypochondriacus v1.0) were downloaded from Phytozome v12 (https://phytozome.jgi.doe.gov/pz/portal.html). The genome sequences of spinach (accession number: PRJNA325593) and sugar beet (accession number: PRJNA268352) were downloaded from National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). All data used during the current study are included in this published article and its additional files or are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s12870-020-02620-z.

References

- 1.Morales A, Zurita-Silva A, Maldonado J, Silva H. Transcriptional responses of Chilean quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.) under water deficit conditions uncovers ABA-independent expression patterns. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:216. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yasui Y, Hirakawa H, Oikawa T, Toyoshima M, Matsuzaki C, Ueno M, Mizuno N, Nagatoshi Y, Imamura T, Miyago M. Draft genome sequence of an inbred line of Chenopodium quinoa, an allotetraploid crop with great environmental adaptability and outstanding nutritional properties. DNA Res. 2016;23(6):535–546. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsw037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zurita-Silva A, Fuentes F, Zamora P, Jacobsen S, Schwember AR. Breeding quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.): potential and perspectives. Mol Breeding. 2014;34(1):13–30. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Graf BL, Rojas Silva P, Rojo LE, Delatorre Herrera J, Baldeón ME, Raskin I. Innovations in health value and functional food development of quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.) Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2015;14(4):431–445. doi: 10.1111/1541-4337.12135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jacobsen S, Monteros C, Corcuera LJ, Bravo LA, Christiansen JL, Mujica A. Frost resistance mechanisms in quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.) Eur J Agron. 2007;26(4):471–475. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmöckel SM, Lightfoot DJ, Razali R, Tester M, Jarvis DE. Identification of putative transmembrane proteins involved in salinity tolerance in Chenopodium quinoa by integrating physiological data, RNAseq, and SNP analyses. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:1023. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.01023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jarvis DE, Ho YS, Lightfoot DJ, Schmöckel SM, Li B, Borm TJ, Ohyanagi H, Mineta K, Michell CT, Saber N. The genome of Chenopodium quinoa. Nature. 2017;542(7641):307. doi: 10.1038/nature21370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu J, Chen N, Chen F, Cai B, Dal Santo S, Tornielli GB, Pezzotti M, Cheng ZM. Genome-wide analysis and expression profile of the bZIP transcription factor gene family in grapevine (Vitis vinifera) BMC Genomics. 2014;15(1):281. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh KB, Foley RC, Oñate-Sánchez L. Transcription factors in plant defense and stress responses. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2002;5(5):430–436. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5266(02)00289-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baloglu MC, Eldem V, Hajyzadeh M, Unver T. Genome-wide analysis of the bZIP transcription factors in cucumber. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e96014. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wei K, Chen J, Wang Y, Chen Y, Chen S, Lin Y, Pan S, Zhong X, Xie D. Genome-wide analysis of bZIP-encoding genes in maize. DNA Res. 2012;19(6):463–476. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dss026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li D, Fu F, Zhang H, Song F. Genome-wide systematic characterization of the bZIP transcriptional factor family in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) BMC Genomics. 2015;16(1):771. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1990-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jakoby M, Weisshaar B, Dröge-Laser W, Vicente-Carbajosa J, Tiedemann J, Kroj T, Parcy F. bZIP transcription factors in Arabidopsis. Trends Plant Sci. 2002;7(3):106–111. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(01)02223-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dröge-Laser W, Snoek BL, Snel B, Weiste C. The Arabidopsis bZIP transcription factor family-an update. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2018;45:36–49. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2018.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guan Y, Ren H, Xie H, Ma Z, Chen F. Identification and characterization of bZIP-type transcription factors involved in carrot (Daucus carota L.) somatic embryogenesis. Plant J. 2009;60(2):207–217. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.03948.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alonso R, Oñate-Sánchez L, Weltmeier F, Ehlert A, Diaz I, Dietrich K, Vicente-Carbajosa J, Dröge-Laser W. A pivotal role of the basic leucine zipper transcription factor bZIP53 in the regulation of Arabidopsis seed maturation gene expression based on heterodimerization and protein complex formation. Plant Cell. 2009;21(6):1747–1761. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.062968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zinsmeister J, Lalanne D, Terrasson E, Chatelain E, Vandecasteele C, Vu BL, Dubois-Laurent C, Geoffriau E, Le Signor C, Dalmais M. ABI5 is a regulator of seed maturation and longevity in legumes. Plant Cell. 2016;28(11):2735–2754. doi: 10.1105/tpc.16.00470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thurow C, Schiermeyer A, Krawczyk S, Butterbrodt T, Nickolov K, Gatz C. Tobacco bZIP transcription factor TGA2.2 and related factor TGA2.1 have distinct roles in plant defense responses and plant development. Plant J. 2005;44(1):100–113. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Silveira AB, Gauer L, Tomaz JP, Cardoso PR, Carmello-Guerreiro S, Vincentz M. The Arabidopsis AtbZIP9 protein fused to the VP16 transcriptional activation domain alters leaf and vascular development. Plant Sci. 2007;172(6):1148–1156. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hu W, Yang H, Yan Y, Wei Y, Tie W, Ding Z, Zuo J, Peng M, Li K. Genome-wide characterization and analysis of bZIP transcription factor gene family related to abiotic stress in cassava. Sci Rep-UK. 2016;6:22783. doi: 10.1038/srep22783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rozema J, Cornelisse D, Zhang Y, Li H, Bruning B, Katschnig D, Broekman R, Ji B, van Bodegom P. Comparing salt tolerance of beet cultivars and their halophytic ancestor: consequences of domestication and breeding programmes. AoB Plants. 2015;7:plu083. doi: 10.1093/aobpla/plu083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adolf VI, Jacobsen S, Shabala S. Salt tolerance mechanisms in quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.) Environ Exp Bot. 2013;92:43–54. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nijhawan A, Jain M, Tyagi AK, Khurana JP. Genomic survey and gene expression analysis of the basic leucine zipper transcription factor family in rice. Plant Physiol. 2008;146(2):333–350. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.112821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vanitha J, Ramachandran S. Genome-wide expansion and expression divergence of the basic leucine zipper transcription factors in higher plants with an emphasis on sorghum. J Integr Plant Biol. 2011;53(3):4. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2010.01017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu X, Chu Z. Genome-wide evolutionary characterization and analysis of bZIP transcription factors and their expression profiles in response to multiple abiotic stresses in Brachypodium distachyon. BMC Genomics. 2015;16(1):227. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1457-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang Z, Cheng K, Wan L, Yan L, Jiang H, Liu S, Lei Y, Liao B. Genome-wide analysis of the basic leucine zipper (bZIP) transcription factor gene family in six legume genomes. BMC Genomics. 2015;16(1):1053. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-2258-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu JX, Srivastava R, Howell SH. Stress-induced expression of an activated form of AtbZIP17 provides protection from salt stress in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Environ. 2008;31(12):1735–1743. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2008.01873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Henriquez Valencia C, Moreno AA, Sandoval Ibañez O, Mitina I, Blanco Herrera F, Cifuentes Esquivel N, Orellana A. bZIP17 and bZIP60 regulate the expression of BiP3 and other salt stress responsive genes in an UPR-independent manner in Arabidopsis thaliana. J Cell Biochem. 2015;116(8):1638–1645. doi: 10.1002/jcb.25121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu J, Howell SH. bZIP28 and NF-Y transcription factors are activated by ER stress and assemble into a transcriptional complex to regulate stress response genes in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2010;22(3):782–796. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.072173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iwata Y, Fedoroff NV, Koizumi N. Arabidopsis bZIP60 is a proteolysis-activated transcription factor involved in the endoplasmic reticulum stress response. Plant Cell. 2008;20(11):3107–3121. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.061002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim SY. The role of ABF family bZIP class transcription factors in stress response. Physiol Plantarum. 2006;126(4):519–527. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Orellana S, Yanez M, Espinoza A, Verdugo I, Gonzalez E, Ruiz-Lara S, Casaretto JA. The transcription factor SlAREB1 confers drought, salt stress tolerance and regulates biotic and abiotic stress-related genes in tomato. Plant Cell Environ. 2010;33(12):2191–2208. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2010.02220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sun Y, Xu W, Jia Y, Wang M, Xia G. The wheat TaGBF1 gene is involved in the blue-light response and salt tolerance. Plant J. 2015;84(6):1219–1230. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mueller S, Hilbert B, Dueckershoff K, Roitsch T, Krischke M, Mueller MJ, Berger S. General detoxification and stress responses are mediated by oxidized lipids through TGA transcription factors in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2008;20(3):768–785. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.054809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sham A, Al-Azzawi A, Al-Ameri S, Al-Mahmoud B, Awwad F, Al-Rawashdeh A, Iratni R, AbuQamar S. Transcriptome analysis reveals genes commonly induced by Botrytis cinerea infection, cold, drought and oxidative stresses in Arabidopsis. PLoS One. 2014;9(11):e113718. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sham A, Moustafa K, Al-Ameri S, Al-Azzawi A, Iratni R, AbuQamar S. Identification of Arabidopsis candidate genes in response to biotic and abiotic stresses using comparative microarrays. PLoS One. 2015;10(5):e0125666. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Skubacz A, Daszkowska-Golec A, Szarejko I. The role and regulation of ABI5 (ABA-insensitive 5) in plant development, abiotic stress responses and phytohormone crosstalk. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:1884. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gangappa SN, Botto JF. The multifaceted roles of HY5 in plant growth and development. Mol Plant. 2016;9(10):1353–1365. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2016.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang M, Liu Y, Shi H, Guo M, Chai M, He Q, Yan M, Cao D, Zhao L, Cai H. Evolutionary and expression analyses of soybean basic Leucine zipper transcription factor family. BMC Genomics. 2018;19:159. doi: 10.1186/s12864-018-4511-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zou C, Chen A, Xiao L, Muller HM, Ache P, Haberer G, Zhang M, Jia W, Deng P, Huang R. A high-quality genome assembly of quinoa provides insights into the molecular basis of salt bladder-based salinity tolerance and the exceptional nutritional value. Cell Res. 2017;27:1327. doi: 10.1038/cr.2017.124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li F, Fan K, Ma F, Yue E, Bibi N, Wang M, Shen H, Hasan MM, Wang X. Genomic identification and comparative expansion analysis of the non-specific lipid transfer protein gene family in Gossypium. Sci Rep-UK. 2016;6:38948. doi: 10.1038/srep38948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Long M, Rosenberg C, Gilbert W. Intron phase correlations and the evolution of the intron/exon structure of genes. P Natl Acad Sci. 1995;92(26):12495–12499. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.26.12495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rogozin IB, Sverdlov AV, Babenko VN, Koonin EV. Analysis of evolution of exon-intron structure of eukaryotic genes. Brief Bioinform. 2005;6(2):118–134. doi: 10.1093/bib/6.2.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Del Campo EM, Casano LM, Barreno E. Evolutionary implications of intron-exon distribution and the properties and sequences of the RPL10A gene in eukaryotes. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2013;66(3):857–867. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2012.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lynch M. Intron evolution as a population-genetic process. P Natl Acad Sci. 2002;99(9):6118–6123. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092595699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Flagel LE, Wendel JF. Gene duplication and evolutionary novelty in plants. New Phytol. 2009;183(3):557–564. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02923.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moore RC, Purugganan MD. The evolutionary dynamics of plant duplicate genes. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2005;8(2):122–128. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2004.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fan K, Wang M, Miao Y, Ni M, Bibi N, Yuan S, Li F, Wang X. Molecular evolution and expansion analysis of the NAC transcription factor in Zea mays. PLoS One. 2014;9(11):e111837. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu W, Li W, He Q, Daud MK, Chen J, Zhu S. Genome-wide survey and expression analysis of calcium-dependent protein kinase in Gossypium raimondii. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e98189. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Adams KL. Evolution of duplicate gene expression in polyploid and hybrid plants. J Hered. 2007;98(2):136–141. doi: 10.1093/jhered/esl061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li F, Guo X, Liu J, Zhou F, Liu W, Wu J, Zhang H, Cao H, Su H, Wen R. Genome-wide identification, characterization, and expression analysis of the NAC transcription factor in Chenopodium quinoa. Genes. 2019;10(7):500. doi: 10.3390/genes10070500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fan K, Shen H, Bibi N, Li F, Yuan S, Wang M, Wang X. Molecular evolution and species-specific expansion of the NAP members in plants. J Integr Plant Biol. 2015;57(8):673–687. doi: 10.1111/jipb.12344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hsieh T, Li C, Su R, Cheng C, Tsai Y, Chan M. A tomato bZIP transcription factor, SlAREB, is involved in water deficit and salt stress response. Planta. 2010;231(6):1459–1473. doi: 10.1007/s00425-010-1147-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liu C, Mao B, Ou S, Wang W, Liu L, Wu Y, Chu C, Wang X. OsbZIP71, a bZIP transcription factor, confers salinity and drought tolerance in rice. Plant Mol Biol. 2014;84(1–2):19–36. doi: 10.1007/s11103-013-0115-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang Y, Gao C, Liang Y, Wang C, Yang C, Liu G. A novel bZIP gene from Tamarix hispida mediates physiological responses to salt stress in tobacco plants. J Plant Physiol. 2010;167(3):222–230. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang C, Lu G, Hao Y, Guo H, Guo Y, Zhao J, Cheng H. ABP9, a maize bZIP transcription factor, enhances tolerance to salt and drought in transgenic cotton. Planta. 2017;246(3):453–469. doi: 10.1007/s00425-017-2704-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schäffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25(17):3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, Chenna R, McGettigan PA, McWilliam H, Valentin F, Wallace IM, Wilm A, Lopez R. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2007;23(21):2947–2948. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;33(7):1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Krzywinski MI, Schein JE, Birol I, Connors J, Gascoyne R, Horsman D, Jones SJ, Marra MA. Circos: an information aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome Res. 2009;19(9):1639–1645. doi: 10.1101/gr.092759.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Librado P, Rozas J. DnaSP v5: a software for comprehensive analysis of DNA polymorphism data. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(11):1451–1452. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−⊿⊿Ct method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.De Hoon MJ, Imoto S, Nolan J, Miyano S. Open source clustering software. Bioinformatics. 2004;20(9):1453–1454. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. The structural analysis of bZIPs identified in this study.

Additional file 2. The bZIPs identified in spinach, sugar beet, and amaranth.

Additional file 3. The classification and gene structures of bZIPs in quinoa.

Additional file 4. The percentage of members in each bZIP subfamily in quinoa, spinach, sugar beet, and amaranth.

Additional file 5. Phylogenetic relationships of the bZIPs in spinach, sugar beet, amaranth, and Arabidopsis.

Additional file 6. Multilevel consensus sequence and their logo of conserved motifs identified in CqbZIP proteins as predicted by MEME program.

Additional file 7. Genomic locations of bZIPs in quinoa.

Additional file 8. Ka/Ks analysis for orthologous bZIP gene pairs between quinoa and spinach, sugar beet, and amaranth.

Additional file 9. Orthology information of CqbZIPs and AtbZIPs from BLASTP.

Additional file 10. Expression patterns of some duplicated CqbZIP genes in different organs and in roots under salt stress treatment.

Additional file 11. Phylogenetic relationships of the bZIPs in quinoa, spinach, sugar beet, and amaranth.

Additional file 12. PCR primers used for qRT-PCR in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The Arabidopsis bZIP protein sequences were collected from the Arabidopsis information source (TAIR) database (http://www.arabidopsis.org). The genome sequences of quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa v1.0) and amaranth (Amaranthus hypochondriacus v1.0) were downloaded from Phytozome v12 (https://phytozome.jgi.doe.gov/pz/portal.html). The genome sequences of spinach (accession number: PRJNA325593) and sugar beet (accession number: PRJNA268352) were downloaded from National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). All data used during the current study are included in this published article and its additional files or are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.