Abstract

Background

The lifetime prevalence of schizophrenia is 1%. Schizophrenia is among the most severe mental illnesses and gives rise to the highest treatment costs per patient of any disease. It is characterized by frequent relapses, marked impairment of quality of life, and reduced social and work participation.

Methods

The group entrusted with the creation of the German clinical practice guideline was chosen to be representative and pluralistic in its composition. It carried out a systematic review of the relevant literature up to March 2018 and identified a total of 13 389 publications, five source guidelines, three other relevant German clinical practice guidelines, and four reference guidelines.

Results

As the available antipsychotic drugs do not differ to any great extent in efficacy, it is recommended that acute antipsychotic drug therapy should be side-effect-driven, with a number needed to treat (NNT) of 5 to 8. The choice of treatment should take motor, metabolic, sexual, cardiac, and hematopoietic considerations into account. Ongoing antipsychotic treatment is recommended to prevent relapses (NNT: 3) and should be re-evaluated on a regular basis in every case. It is also recommended, with recommendation grades ranging from strong to intermediate, that disorder- and manifestation-driven forms of psychotherapy and psychosocial therapy, such as cognitive behavioral therapy for positive or negative manifestations (effect sizes ranging from d = 0.372 to d = 0.437) or psycho-education to prevent relapses (NNT: 9), should be used in combination with antipsychotic drug treatment. Further aspects include rehabilitation, the management of special treatment situations, care coordination, and quality management. A large body of evidence is available to provide a basis for guideline recommendations, particularly in the areas of pharmacotherapy and cognitive behavioral therapy.

Conclusion

The evidence-based diagnosis and treatment of persons with schizophrenia should be carried out in a multiprofessional process, with close involvement of the affected persons and the people closest to them.

Schizophrenia is one of the most severe mental illnesses. It has a point prevalence of 4.6 per 1000 inhabitants, a lifetime prevalence of around 1%, and the median reported incidence is 15 cases per 100 000 inhabitants (see [1] for details). Approximately two thirds of newly arising cases of schizophrenia occur before 45 years of age, i.e., in young to middle-aged adults. With regard to the clinical presentation, schizophrenia is characterized by a heterogeneous phenotype and a variable course, so one should really speak of a group of diseases, “the schizophrenias.” However, in accordance with the criteria for diagnosis and classification we used the singular “schizophrenia” for the guidelines. The disease is characterized by psychopathological disorders of perception, ego functions, affectivity, energy, and psychomotor function and by events that occur at particular junctures in the disease course (1). The latter is inter- and intraindividually variable: there may be one single episode, recurring episodes with no symptoms at all in between, relapses of increasing severity, or continuous illness with no periodic absence of symptoms. Although self-limiting episodes of schizophrenia are known to occur, the majority of episodes require multiprofessional treatment. The diagnosis is made in operationalized manner according to ICD-10 criteria. It is not only very important to differentiate schizophrenia from other mental illnesses; somatic diseases must also be considered as comorbidites or as causes for secondary psychoses.

One important factor that has, so far, received little attention is the very high mortality rate. Studies show that schizophrenia reduces life expectancy by anything from 10 to 25 years (2, 3). There are many reasons for the elevated mortality: increased suicidality (especially in the early years of illness), the occurrence of somatic diseases, underdiagnosis of somatic diseases, deficient self-care, and inadequate psychiatric/psychotherapeutic treatment, as well as aspects of treatment-associated adverse effects (1, 4, 5). Around 10% of persons in whom schizophrenia is diagnosed for the first time attempt suicide in the 12 months following diagnosis, and one can conclude, depending on the individual survey, that 5 to 15% of persons with a schizophrenia spectrum disorder kill themselves (6– 12). An example of the underdiagnosis of somatic comorbidities is provided by a Swedish cohort study of 6 097 838 adults (including 8277 with schizophrenia): In both women (hazard ratio 3.33, 95% confidence interval [2.73; 4.05]) and men (2.20 [1.83; 2.65]) with schizophrenia, death due to ischemic heart disease occurred more frequently than in the rest of the population. Furthermore, the likelihood of timely diagnosis was significantly lower in those with schizophrenia (26.3% versus 43.7%). The figures for cancer disease were similar (13). Other clinically relevant characteristics that are associated with schizophrenia and are often interrelated are marked stigmatization; associations with previous trauma and experience of violence (the mean proportion of persons with schizophrenia who fulfill the criteria for post-traumatic stress disorder [PTSD] is as high as 30% [14]); a high prevalence of comorbid substance dependency (principally tobacco (prevalence up to 80% [15]), alcohol, and cannabis (mean prevalences ˜25% [16]); high rates of unemployment and homelessness (˜12% of homeless persons have a psychotic disease [17]); and reduced social participation.

The new German clinical practice guidelines

The clinical practice guidelines on schizophrenia published in 2019 represent a comprehensive revision and expansion of the two previous versions from 1998 and 2006. Each of these earlier documents was conceived, developed, and published as patient-centered, evidence-based, and consensus-based guidelines in accordance with the rules and standards of the Association of the Scientific Medical Societies in Germany (AWMF) (1).

Methods

The guideline revision was undertaken by a committee of persons representative of the intended users, divided into a steering group, an extended steering group, a consensus group, and an additional expert group (ebox 1). For the purpose of revision the subject matter was divided into modules, each dealt with by a dedicated working group in a multistage process (see [18]):

eBOX 1. Professional societies, interest groups, and persons involved in the revision of the guideline.

Project management

Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Gaebel (lead)

Prof. Dr. Alkomiet Hasan

Prof. Dr. Peter Falkai

Project organization and coordination, methods

Dr. Isabell Lehmann

Other members of steering group

Prof. Dr. Birgit Janssen

Prof. Dr. Thomas Wobrock

Prof. Dr. Jürgen Zielasek

Extended steering group

Prof. Dr. Thomas Becker

Prof. Dr. Andreas Bechdolf

Prof. Dr. Stefan Klingberg

Prof. Dr. Hans Joachim Salize

Prof. Dr. Rainer Richter (to May 2015), Dr. Nikolaus Melcop (from June 2016), Bundespsychotherapeutenkammer

Prof. Dr. Stefan Wilm, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Allgemeinmedizin und Familienmedizin e. V.

Prof. Dr. Tania Lincoln, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychologie e. V

Dr. Sabine Köhler, Berufsverband Deutscher Psychiater e. V.

Dr. Christian Raida, Berufsverband Deutscher Nervenärzte e. V

Ruth Fricke, Bundesverband Psychiatrie Erfahrener e. V.

Gudrun Schliebener (to August 2017), Karl-Heinz Möhrmann (from September 2017), Bundesverband der Angehörigen psychisch Kranker e. V.

Prof. Dr. Benno Schimmelmann (to May 2016), Prof. Dr. Christoph Correll (from June 2016), Deutsche Gesellschaft für Kinder- und Jugendpsychiatrie, Psychosomatik und Psychotherapie

Consensus group

Officer of association/organization (deputy)

Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Neuropsychopharmakologie und Pharmakotherapie e. V.: Prof. Dr. Helge Frieling (PD Dr. Michael Kluge)

Arzneimittelkommission der deutschen Ärzteschaft: Prof. Dr. Christopher Baethge (Prof. Dr. Tom Bschor)

Berufsverband der Kinder- und Jugendärzte e. V.: Dr. Karin Geitmann

Berufsverband deutscher Nervenärzte: Dr. Christian Raida (Dr. Roland Urban)

Berufsverband deutscher Psychologinnen u. Psychologen e. V.: Inge Neiser (Heinrich Betram)

Berufsverband deutscher Psychiater e. V.: Dr. Sabine Köhler (Dr. Christian Vogel)

Berufsverband für Kinder- und Jugendpsychiatrie, Psychosomatik und Psychotherapie in Deutschland e. V.: Dr. Reinhard Martens

Bundesarbeitsgemeinschaft für Rehabilitation e. V.: Dr. Michael Schubert (to December 2017), Dr. Theresia Widera (from January 2018)

Bundesdirektorenkonferenz: Prof. Dr. Manfred Wolfersdorf (to July 2017), Prof. Dr. Euphrosyne Gouzoulis-Mayfrank (from August 2017) (Prof. Dr. Thomas Pollmächer, Dr. Sylvia Claus (from March 2018)

Bundesfachverband Leitender Krankenpflegepersonen in der Psychiatrie: Heinz Lepper (Stephan Bögershausen)

Bundespsychotherapeutenkammer: Prof. Rainer Richter (to May 2015), Dr. Nikolaus Melcop (from June 2016) (Dr. Tina Wessels)

Bundesverband der Angehörigen Psychisch Kranker e. V.: Gudrun Schliebener (to August 2017), Karl-Heinz Möhrmann (from September 2017) (Wiebke Schubert)

Bundesverband der Berufsbetreuer/innen e. V.: Iris Peymann (Thorsten Becker)

Bundesverband der Vertragspsychotherapeuten e. V.: Hans Ramm (Dr. Christian Willnow to August 2017, Benedikt Waldherr from October 2017)

Bundesarbeitsgemeinschaft Künstlerische Therapien: Eva Maas (to August 2017) (Silke Ratzeburg)

Bundesinitiative Ambulante Psychiatrische Pflege e. V.: Alfred Karsten (Günter Meyer)

Dachverband Deutschsprachiger Psychosen Psychotherapie e. V.: Prof. Dr. Dorothea von Haebler (Dr. Günther Lempa)

Deutsche Fachgesellschaft für Psychiatrische Pflege: Prof. Dr. Michael Schulz (Bruno Hemkendrais)

Dachverband Gemeindepsychiatrie e. V.: Petra Godel-Ehrhardt

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Allgemeinmedizin und Familienmedizin e. V.: Prof. Dr. Stefan Wilm (Prof. Dr. Erika Baum, Martin Beyer)

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Gerontopsychiatrie und -psychotherapie e. V.: Prof. Dr. Tillmann Supprian (Dr. Beate Baumgarte)

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin e. V.: Dr. Burkhardt Lawrenz

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Kinder- und Jugendpsychiatrie, Psychosomatik und Psychotherapie e. V.: Prof. Dr. Gerd Schulte-Körne (to August 2017), Prof. Dr. Christoph Correll (from September 2017) (Prof. Dr. Christian Fleischhaker)

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Neuropsychologie e. V.: Prof. Dr. Cornelia Exner (Dr. Steffen Aschenbrenner from September 2017)

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychiatrie und Psychotherapie, Psychosomatik und Nervenheilkunde: Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Maier (Prof. Dr. Peter Falkai, Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Gaebel)

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychoanalyse, Psychotherapie, Psychosomatik und Tiefenpsychologie e. V.: Dr. Christian Maier (to March 2016), Prof. Dr. Christiane Montag (from April 2016) (Dr. Ingrid Rothe-Kirchberger)

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychologie e. V.: Prof. Dr. Tania Lincoln (Prof. Dr. Stefan Klingberg)

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychoedukation e. V.: Prof. Dr. Josef Bäuml (Dr. Gabriele Pitschel-Walz)

Deutsche Musiktherapeutische Gesellschaft e. V: Beatrix Evers-Grewe

Deutsche PsychotherapeutenVereinigung e. V.: Dr. Cornelia Rabe-Menssen (Mechtild Lahme)

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Soziale Psychiatrie e. V.: Clemens Firnenburg (to August 2017), Prof. Dr. Uwe Gonther (from November 2017) (Ute Merkel to October 2017, PD Dr. Jann Schlimme from November 2017)

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Systemische Therapie und Familientherapie e. V.: Dr. Ulrike Borst (Dr. Volkmar Aderhold)

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Verhaltenstherapie e. V.: Rudi Merod (Prof. Dr. Tania Lincoln)

Deutscher Verband der Ergotherapeuten e. V.: Marina Knuth

Deutscher Verband für Physiotherapie e. V.: Eckhardt Böhle (Angelika Heck-Darabi)

Deutsche Vereinigung für Soziale Arbeit im Gesundheitswesen e. V.: Claudia Welk (Elisabeth Helmich from June 2017)

Kompetenznetz Schizophrenie: Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Wölwer

Expert group

Prof. Dr. Thomas Becker, Prof. Dr. med. Stefan Leucht

Prof. Dr. Andreas Bechdolf, Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Maier

Prof. Dr. Peter Falkai, Prof. Dr. Eva Meisenzahl

Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Gaebel, Prof. Dr. Andreas Meyer-Lindenberg

Prof. Dr. Hermann-Josef Gertz, Prof. Dr. Hans-Jürgen Möller

Prof. Dr. Gerhard Gründer, Prof. Dr. Dipl.-Psych. Wulf Rössler

Prof. Dr. Stefan Klingberg, Prof. Dr. Hans Joachim Salize

PD Dr. Markus Kösters, Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Wölwer

Prof. Dr. Martin Lambert

Expert group (pediatric psychiatry and psychotherapy)

Prof. Dr. Christoph Correll, Prof. Dr. Benno Schimmelmann

Prof. Dr. Frauke Schultze-Lutter, Dr. Reinhard Martens

Prof. Dr. Stefanie J. Schmidt

Support staff

Dr. Andrea Hinsche-Böckenholt, Anja Dorothée Streb, M.A.

Formulation and agreement of clinical issues within the guidelines group

Identification and methodological evaluation of existing guidelines on schizophrenia (for the purpose of guideline adaptation)

Systematic search of the literature with regard to questions not adequately answered by guideline adaptation (start date: 3 March 2016, last research: 1 March 2018)

Systematic selection and evaluation of the evidence

Formulation of recommendations and suggestions for recommendation grades by the module working groups and the steering group according to the PICO (patient population, intervention, comparison, outcome) scheme (19)

Adoption of the recommendations and structured consensus building (consensus conferences and written Delphi process)

Internal and external reviewing and adoption of the guidelines

Only guidelines of high methodological quality on relevant topics were used as sources (20– 24). Domain 3 (Methodological Rigour of Development) of the German Instrument for Methodological Guideline Appraisal (DELBI) was used for assessment. Gradations of evidence and wordings of recommendations from these source guidelines were adapted for use in the revised guidelines. Further sources of recommendations on dependency-specific topics were two AWMF clinical practice guidelines (15, 25). An overview of the guidelines from Germany and other countries that were used, together with related AWMF guidelines, can be found in eTable 1. Moreover, for some of the guideline recommendations systematic de novo research was carried out (efigure 1), while for other recommendations not based on evidence clinical consensus points were compiled.

eTable 1. National and international source guidelines, reference guidelines, and other related guidelines used in compiling the revision.

| Title | Class | Number | Link/reference | Year | Validity |

| Source guidelines/other German clinical practice guidelines used as sources | |||||

| NICE: Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: prevention and management | – | CG178 | www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg178 | 2014 | 2019 (still valid) |

| NICE: Psychosis and schizophrenia in children and young people: recognition and management | – | CG155 | www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg155 | 2013 | 2016 (still valid) |

| NICE: Violence and aggression: short-term management in mental health, health and community settings | – | NG10 | www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng10 | 2015 | 2019 |

| SIGN: Management of schizophrenia | – | 131 | www.sign.ac.uk/sign-131-management-of-schizophrenia.html | 2013 | 2016 |

| Psychosocial treatment of severe mental illness | S3 | 038 – 020 | www.awmf.org/leitlinien/detail/ll/038–020.html | 2018 | 1. 10. 2023 |

| Alcohol-related disorders: screening, diagnosis and treatment* | S3 | 076 – 001 | www.awmf.org/leitlinien/detail/ll/076–001.html | 2014 | 30. 7. 2019 |

| Tobacco consumption (smoking), dependent and harmful: screening, diagnosis and treatment* | S3 | 076 – 006 | www.awmf.org/leitlinien/detail/ll/076–006.html | 2014 | 30. 7. 2019 |

| Reference guidelines | |||||

| WFSBP Update 2012 on the acute treatment of schizophrenia and treatment resistance | – | – | www.wfsbp.org/educational-activities/wfsbp-treatment-guidelines-and-consensus-papers/ | 2012 | No data |

| WFSBP Update 2012 on the long-term treatment of schizophrenia and management of antipsychotic-induced side effects | – | – | www.wfsbp.org/educational-activities/wfsbp-treatment-guidelines-and-consensus-papers/ | 2013 | No data |

| WFSBP Update 2015 Management of special circumstances: Depression, suicidality, substance use disorders and pregnancy and lactation | – | – | www.wfsbp.org/educational-activities/wfsbp-treatment-guidelines-and-consensus-papers/ | 2015 | No data |

| RANZCP: Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for the management of schizophrenia and related disorders | – | – | www.ranzcp.org/practice-education/guidelines-and-resources-for-practice/schizophrenia-cpg-and-associated-resources | 2016 | No data |

| Related guidelines (primarily used in background text) | |||||

| Prevention of obsessive-compulsive behavior: prevention and treatment of aggressive behavior in adults | S3 | 038 – 022 | www.awmf.org/leitlinien/detail/ll/038–022.html | 2018 | 11. 2. 2013 |

| Unipolar depression—National Disease Management Guideline | S3 | Nvl – 005 | www.awmf.org/leitlinien/detail/ll/nvl-005.html | 2015 | 15. 11. 2020 |

| Anxiety disorders | S3 | 051 – 028 | www.awmf.org/leitlinien/detail/ll/051–028.html | 2014 | 15. 4. 2019 |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorders | S3 | 038 – 017 | www.awmf.org/leitlinien/detail/ll/038–017.html | 2013 | 21. 5. 2018 |

| Autism spectrum disorders in childhood, adolescence, and adulthood, part 1: diagnosis | S3 | 028 – 018 | www.awmf.org/leitlinien/detail/ll/028–018.html | 2016 | 4. 4. 2021 |

| Treatment of depressive disorders in children and adolescents | S3 | 028 – 043 | www.awmf.org/leitlinien/detail/ll/028–043.html | 2013 | 30. 6. 2018 |

| Suicidality in childhood and adolescence | S2k | 028 – 031 | www.awmf.org/leitlinien/detail/ll/028–031.html | 2016 | 30. 5. 2021 |

*These German clinical practice guidelines were not assessed with the DELBI instrument, because they were previously published, valid guidelines.

eFigure 1.

Flow chart of systematic literature survey.

The diagram summarizes the entire literature survey. The individual searches and the search terms used can be found in the guideline report (18) (this flow chart does not form part of the guidelines).

Updated content in the revised guidelines

The modular structure of the guidelines is intended to enable future revision on the lines of the “living guidelines” principle. Box 1 summarizes the most important changes in the revised clinical practice guidelines, described in more detail below.

BOX 1. What are the most important changes in the revised guidelines?

Recommendations for the entire life span: While the previous version of the guidelines focused on the age range 18 to 65, the new guidelines contain key recommendations for children and adolescents and for the elderly (> 65 years).

Somatic illness: New recommendations were developed to include somatic illness in differential diagnosis (detection of rare somatic causes of secondary schizophrenia). Special attention was paid to the detection and treatment of somatic comorbidity and to reduction of the high morbidity and mortality.

Adverse effect–guided antipsychotic treatment: In view of the often only small differences in effect among various antipsychotics, most of the recommendations do not prioritize particular substances. Risks and benefits need to be weighed in each case. Thus, emphasis was placed on individualized antipsychotic therapy at the lowest possible dosage, paying attention to adverse effects.

Antipsychotic prevention of relapse: The necessity of continuous antipsychotic prophylaxis was emphasized. In contrast to the previous guidelines, the duration of antipsychotic treatment to prevent relapses is not specified—this should be determined individually on the basis of various factors, e.g., the severity of the index episode, the stability of the patient’s social network, and the comorbidities present, and should be regularly reevaluated.

Pharmacological treatment resistance: The necessity of excluding pseudo-treatment resistance was stressed. In the presence of pharmacological treatment resistance, the importance of the antipsychotic agent clozapine was accentuated. Clozapine should be used before offering a treatment with a combination of antipsychotics.

Psychotherapy: It was emphasized that every person with schizophrenia should be offered cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)—the therapy content and dosage (at least 16 h, preferably more than 25 h) were specified. Further procedures accorded the highest recommendation grade are psychoeducation, social competence training, cognitive remediation, and work with relatives.

Psychosocial treatment: The importance of this type of treatment (e.g., artistic therapy, body therapy, ergotherapy) as a further therapeutic pillar was reinforced, but overall the recommendation grades are lower than those for psychotherapeutic procedures.

Special treatment conditions: This module contains recommendations on the diagnosis and treatment of catatonia, depression and suicidality, post-traumatic stress disorder, and substance consumption disorders (alcohol, tobacco, cannabis). Further elements are sex-specific aspects, pregnancy and the breastfeeding period, and the new section on the at-risk stage.

Diagnosis and differential diagnosis

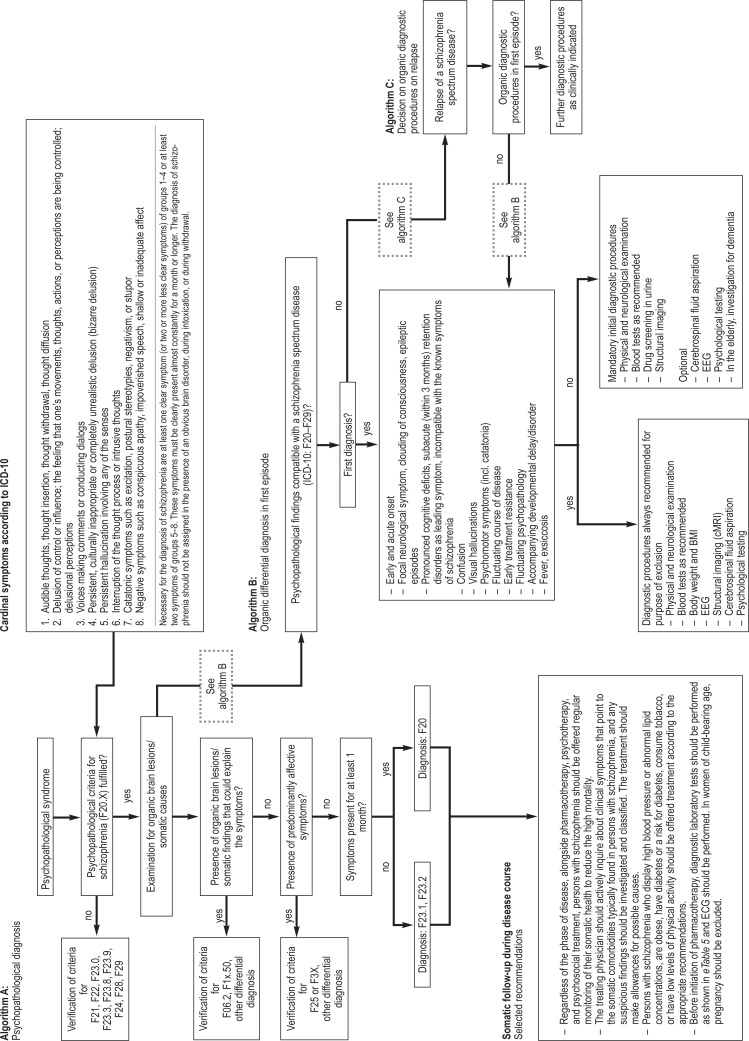

As stated above, schizophrenia is diagnosed according to the operationalized criteria of ICD-10 (efigure 2). However, the guidelines give a glimpse of the changes that can be anticipated in ICD-11. One particular innovation is the possibility of describing the course of the illness on the basis of symptom domains (positive symptoms, negative symptoms, cognitive disorders, psychomotor disorders, and affective disorders) (26). Much more importance is attached in the revised guidelines to aspects of organic differential diagnosis: recommendations were agreed with the intention of on the one hand detecting rare organic causes of schizophrenia (e.g., autoimmune encephalitis) in timely fashion, and on the other hand diagnosing the frequently occurring somatic comorbidities and integrating them into the overall treatment plan. eBox 2 presents the accompanying somatic disorders most commonly found in persons with schizophrenia, with the data expressed in terms of prevalence rates, incidence rates, or odds ratios.

eFigure 2.

Algorithms for psychopathological and somatic differential diagnosis (derived from, but not forming part of, the new German clinical practice guidelines)

General treatment principles

Modern psychiatric/psychotherapeutic treatment of persons with schizophrenia should always be multiprofessional, and all those involved in the treatment should maintain an empathetic, appreciative attitude. According to the guidelines, the “general goal of treatment [is] a person broadly free of symptoms of illness who is capable of living in a self-determined manner, has been informed about the therapeutic options, and is in the position to weigh up the risks and benefits thereof” (1). To achieve this, the elements of pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy, and psychosocial treatments should be offered in terms of an overall treatment plan with the close involvement of the person with schizophrenia together with their relatives or other reference persons. According to the evidence and consensus opinion, antipsychotic drug treatment alone is generally insufficient, as is renunciation of antipsychotic pharmacotherapy. Other forms of treatment, such as the use of antidepressants or neurostimulation procedures (e.g., electroconvulsive therapy), are reserved for particular indications (e.g., depressive syndromes or clozapine resistance).

Treatment with antipsychotics

Antipsychotics are highly effective with regard to the goals relevant to the disease (e.g., reduction of psychotic symptoms, prevention of relapse). For example, the largest meta-analysis with the highest quality methods shows a number needed to treat (NNT) of 3 for 1-year prevention of relapse (relapse rate 27% with antipsychotic treatment, 64% with placebo) (27). In respect of the therapeutic response in terms of reduction of psychotic experiences, another large-scale and high-quality meta-analysis shows an NNT of 5 or 8 for a minimal or good response (51%/23% with antipsychotic treatment, 30%/14% with placebo) (28). One basic innovation in the new German clinical practice guidelines is the emphasis on adverse effect–guided selection of the antipsychotic substances—abolishing the general prioritization of a specific substance group. Based on an adaptation of a NICE guideline (20) and on a meta-analysis (29), the following definition was formulated: “We recommend offering antipsychotics at a dose that is within the range recommended by the respective international consensuses and is as low as possible and as high as necessary (lowest possible dose)”. A low dose should be chosen particularly in patients suffering their first episode of schizophrenia, who are more vulnerable to adverse effects and overall respond better to low dosages. It is important that treatment to reduce psychotic symptoms be offered in the form of antipsychotic monotherapy. The recommendation of monotherapy is justified especially on grounds of better tractability and a lower risk of adverse effects and drug interactions. Moreover, nearly all of the source studies and meta-analyses investigated antipsychotics given as monotherapy.

For the first time, and uniquely worldwide, clinical consensus point (CCP) recommendations on the discontinuation of antipsychotic medication were agreed. This should not be defined as the primary course of action, however, because of the low recommendation grade (“may be considered”) compared with administration of antipsychotics to prevent relapse (“we recommend”). Nevertheless, suggestions, recommendations, and strategies are now in place for dealing with the routinely expressed request from both patients and their relatives for antipsychotic medication to be stopped. It is important, in clinical practice, to state that treatment does not end with discontinuation of the medication. On the contrary, regular, coordinated outpatient psychiatric and/or psychotherapeutic follow-up visits should continue for at least 2 years, with two goals: (1) early detection of signs and symptoms of an impending relapse (e.g., sleep disorders, a brief psychotic episode, depressive symptoms, inner unrest); (2) implementation of interventions to help manage stress or structure daily activities. It is vital for treatment to continue beyond supervised discontinuation of drug intake.

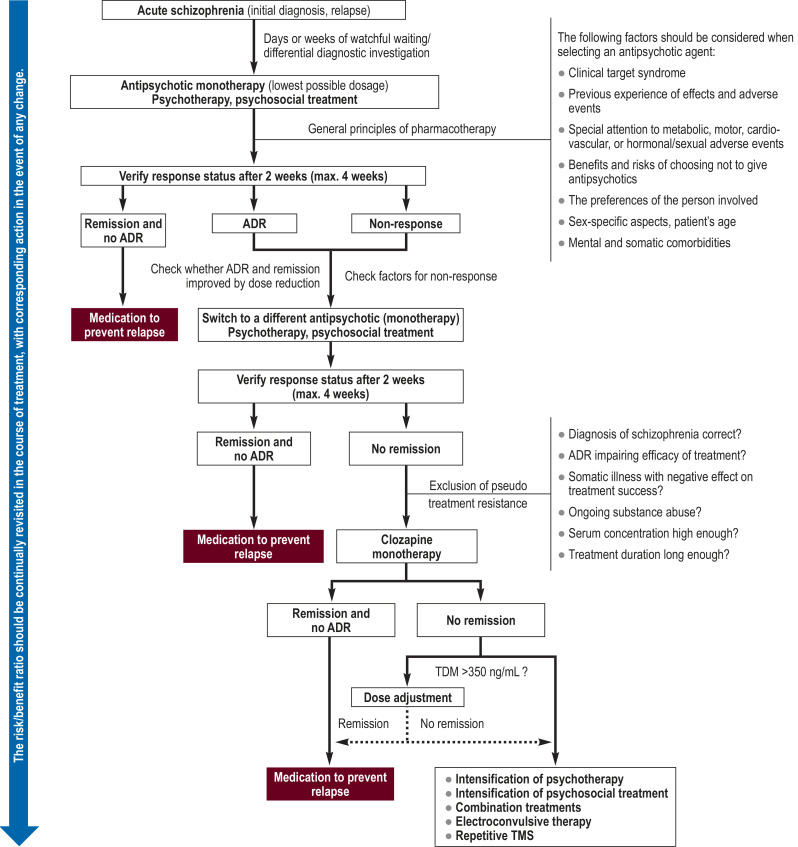

In contrast to the guideline recommendation of monotherapy, however, in clinical practice the use of polypharmacy is growing, particularly later in the disease course (30). This discrepancy between clinical practice and evidence was addressed as follows: According to the revised guidelines, a combination of two antipsychotics should be given (recommendation grade CCP) only after the failure of three previous attempts at antipsychotic treatment of adequate dosage and duration—including a course of clozapine—as monotherapy (recommendation 43, recommendation grade A, and recommendation 46, recommendation grade A). The addition of a second antipsychotic or an antidepressant for the temporary treatment of unrest, sleep disorders, elevated prolactin concentration, or depressive symptoms is considered separately in the guidelines—this special situation does not fall under the described recommendation to offer monotherapy, but when any additional substance is given, one must bear in mind the possible increase in adverse effects and monitor the patient accordingly. The Table and eTable 2 summarize the meta-analyses cited in the guidelines and list the corresponding recommendations. The Figure shows a treatment algorithm, derived from relevant recommendations, which focuses on antipsychotic treatment.

Table. Three selected topics in the field of antipsychotic psychotherapy with the underlying meta-analyses and other source documents.

| Topic | Sources | Principal finding/recommendation |

| Antipsychotics for treatment of psychotic symptoms at the lowest possible dosage (LoE 1 + /1 ++, recommendation grade A) |

Meta-analysis and NICE guideline adaptation (20, 28, 29, 38) | The NICE guidelines recommend offering antipsychotic medication to every person with schizophrenia. A meta-analysis of 17 studies with 3156 participants (median study duration 12 weeks) found a good response (50% improvement related to initial psychopathology on PANSS/BPRS) in 51.9% of cases and a minimal response (20% improvement) in 81.3% of cases (38). For persons with recurring schizophrenia, a meta-analysis of 167 studies with 28 101 participants (median study duration 6 weeks) showed a good response in 23% of those on antipsychotics (versus 14% with placebo) and a minimal response in 51% (versus 30% with placebo) (28). In general, higher dosages were associated with more adverse events but were not always more effective. With regard to various endpoints, low dosages were not inferior to the standard dose (e.g., difference in risk of treatment failure = 0.02 [−0.05; 0.10]), but very low dosages were inferior to the standard dose (e.g., treatment failure 0.14 [0.02; 0.26]). ► User-oriented recommendation: Offer antipsychotics in the lowest possible dosage to every person with schizophrenia, guided by the risk of adverse events. |

| Antipsychotics for the prevention of relapse (LoE 1 ++, recommendation grade A) |

Meta-analysis (27) | A meta-analysis of 65 randomized controlled trials (63 of them double-blind placebo-controlled) with 6493 participants showed that the rate of relapse in the first year of observation was significantly lower for antipsychotic treatment (27%) than for placebo 64%) (RR 0.40 [0.33; 0.49], NNT 3). This superiority was found in persons with a first episode and in those with a relapse, in persons in remission and in those with residual symptoms, and was independent of treatment duration (a few months to many years). Adverse drug events of all kinds occurred less often with placebo. ► User-oriented recommendation: Offer antipsychotics for the prevention of relapse and explain the risk of relapse if the medication is discontinued. |

| Duration of antipsychotic treatment (LoE 1 +, recommendation grade A and statement) |

Meta-analysis and guideline adaptation (20, 27) | While the previous version of these guidelines (39) recommended a treatment duration of at least a year for a first episode and several years (if need be, lifelong) for a relapse, the new guidelines just recommend antipsychotic medication for the prevention of relapse. In each individual case, the duration should be determined jointly by the treating physician, the person with schizophrenia, and those who are closest to him/her, taking account of various relevant parameters. Whenever antipsychotics are discontinued, the high risk of relapse (in 1st year: 27% with continued treatment, 65% after discontinuation; after 3 to 6 years: 22% with continued treatment, 63% after discontinuation) must be explained. ► User-oriented recommendation: When setting up the treatment plan for prevention of relapse, jointly agree the individual treatment duration and explain the risks involved in discontinuation. In addition, discuss the benefits and risks of supervised discontinuation of medication. |

BPRS, Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale; LoE, level of evidence; NNT, number needed to treat; PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; RR, relative risk

eTable 2. Supplement to the Table. Further selected topics in the field of antipsychotic drug therapy with the underlying meta-analyses and other source documents.

| Topic | Sources | Principal finding/recommendation |

| Antipsychotic monotherapy with a continuous strategy (LoE 1+, recommendation grade B) |

Meta-analysis and guideline adaptation (20, e1) | A meta-analysis shows that an intermittent dosing strategy within 6 months of stabilization bears a fivefold risk of relapse (OR = 5.00 [4.32; 5.78]) (40). Because longer follow-up data from randomized clinical studies on this topic are not available in such quantity, the guidelines group reduced the recommendation grade. ► User-oriented recommendation: In general, offer a continuous treatment strategy for prevention of relapse—in the event of stability and valid reasons arguing against continuous medication in the long term, discuss other options (e.g., intermittent treatment, CCP, recommendation 24; discontinuation of medication, CCP, recommendations 26 and 27). |

| Antipsychotics for treatment of psychotic symptoms: monotherapy (LoE 1+, recommendation grade A) |

Almost all of the meta-analyses investigated | Almost all of the meta-analyses identified in the literature survey used antipsychotics as monotherapy to reduce psychotic symptoms. The risk of adverse events and interactions is lower with monotherapy than with combination treatment ► User-oriented recommendation: Offer antipsychotic treatment aimed at reducing psychotic symptoms in the form of monotherapy. |

| Verification of response status after 2 weeks (max. 4 weeks) (LoE 1+, recommendation grade A) |

Meta-analysis (e2) | It was shown, on the basis of 34 studies with N = 9460 participants, that psychopathological improvement of less than 20% (measured on PANSS or BPRS) after 2 weeks predicted non-response at the primary endpoint (weeks 4 to 12) with specificity of 86% (positive predictive value 90%). ► User-oriented recommendation: Check the response status after 2 weeks (max. 4 weeks) and, in the event of non-response, discuss switching to a different preparation and look for the factors responsible for the failure to respond. |

| Clozapine monotherapy in resistance to pharmacological treatment (LoE 1 ++/1, recommendation grade A) |

Meta-analyses and guideline adaptation (20, 23, e3, e4) | In confirmed pharmacological treatment resistance, a trial of clozapine monotherapy should be offered. This recommendation was adapted from other guidelines (6, 9). However, the available meta-analyses show a somewhat divergent picture. In the meta-analysis with pairwise comparisons (43) (21 studies 801 patients with clozapine, 799 patients with another antipsychotic drug), clozapine was superior to a comparison treatment for nearly all of the endpoints, e.g., change in psychotic symptoms in the first 3 months (SMD −0,39 [−0,61; −0,17]), positive symptoms in the first 3 months (SMD –0.27 [−0.47; −0.08]) and thereafter (SMD −0.25 [−0.43; −0.07]), and negative symptoms in the first 3 months (SMD −0.25 [−0.40; −0.10]). In the available network meta-analyses (40 studies, 5127 participants) (42), superiority of one antipsychotic over another in the scenario of pharmacological treatment resistance could not be shown with certainty. Only in comparison with haloperidol and chlorpromazine was clozapine shown to be superior. ► User-oriented recommendation: In pharmacological treatment resistance, offer a trial of clozapine after excluding pseudo-treatment resistance. |

| Therapeutic drug monitoring with clozapine (LoE 2++, recommendation grade B) |

Guideline adaptation (e5, e6) | Clozapine concentrations over 350 ng/mL show an association with improved response to clozapine in pharmacological treatment resistance. ►User-oriented recommendation: In the event of pharmacological treatment resistance, check the serum concentration of clozapine and consider discussing an increase in dosage. Be aware that the clozapine-associated adverse events (sedation, salivation, dizziness, constipation) and complications (agranulocytosis, myocarditis) may intensify as you raise the dosage. |

| High-dose antipsychotic treatment (LoE 1+, recommendation grade B) |

Meta-analysis (e7) | A meta-analysis of five studies with 348 participants showed no superiority of high-dose treatment to standard treatment in treatment resistance (g = −0.14 [−0.37; −0.10]). ► User-oriented recommendation: As a rule, avoid high-dose antipsychotic treatment, defined as dosage exceeding the approved limit for the substance concerned. |

| Antipsychotic combination treatment (LoE 1+, recommendation grade A and CCP) |

Meta-analysis (e8) | A meta-analysis of 31 studies revealed that open-label studies investigating a combination of antipsychotics showed an advantage of antipsychotic combination therapy over monotherapy with regard to amelioration of symptoms (16 studies, N = 694, SMD = −0.53, [−0.87; −0.19], p = 0.0020). However, this benefit could not be demonstrated in studies with high-quality methods (9 studies, N = 378, SMD = −0.30 [−0.78; 0.19]) or in double-blind trials (10 studies, N = 409, SMD = −0.37 [−0.83; 0.10]). ► User-oriented recommendation: In the event of pharmacological treatment resistance, first offer clozapine (A). Consider combination treatment only after failure of monotherapy with a total of three antipsychotics, including clozapine (CCP). |

| Augmentation with mood stabilizers (LoE 1+, recommendation grade A) |

Meta-analyses (e9, e11) | Various meta-analyses were cited, all of which showed no added benefit of augmentation of antipsychotic treatment of schizophrenia with carbamazepine, lithium, lamotrigine, or valproate. ► User-oriented recommendation: In persons with schizophrenia, do not augment the treatment with mood stabilizers. |

| Augmentation with antidepressants (LoE 1++, recommendation grades A and B) |

Meta-analysis (e12) | A meta-analysis of 82 studies with 3608 participants showed that adding antidepressants to existing antipsychotic treatment was superior to the control treatment in terms of depressive symptoms (42 studies, 1849 participants, SMD −0.25 [−0.38; −0.23]) and negative symptoms (48 studies, 1905 participants, SMD −0.30 [−0.44; −0.16]). ► Recommendation: A short-term trial of antidepressants is recommended for the indications depression (recommendation grade A) and negative symptoms (recommendation grade B), with close attention to adverse events and interactions. ► User-oriented recommendation: After a confirmed depressive episode, exclude secondary causes (e.g., D2-related dysphoria) and offer a short-term trial of an antidepressant. After exclusion of secondary causes for a negative syndrome and implementation of psychosocial competence training and cognitive behavioral therapy, offer a treatment trial of an antidepressant. |

Figure.

Treatment algorithm derived from the revised German clinical practice guidelines (focus on pharmacology): Here the guidelines’ essential treatment recommendations are summarized; for clinical application, however, it is vital to consult the long version of the guidelines and the detailed recommendations therein (this algorithm does not form part of the clinical practice guidelines).

ADR, adverse drug reaction; TDM, therapeutic drug monitoring; TMS, transcranial magnetic stimulation

Psychotherapy and psychosocial treatments

The revised clinical practice guidelines place far more emphasis on psychotherapy. Combination of treatment with an antipsychotic substance and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is recommended for all persons with schizophrenia (effect size for positive symptoms: d = 0.372; for negative symptoms: d = 0.437). CBT should be offered (recommendation grade A). If CBT begins while the patient is in the hospital, it should be continued on an outpatient basis after discharge; the duration of treatment should be ≥ 16 sessions, and for optimization of treatment effects and in cases with more complex treatment goals ≥ 25 sessions should be offered (recommendation grade B). The inpatient and outpatient psychotherapeutic care available for persons with schizophrenia in Germany is clearly inadequate, although it remains unclear whether the previously very low rates of psychotherapy in this population have been increased by the extension of the indication to all phases of the disease by the Federal Joint Committee (G-BA) in 2014 (art. 26 para. 2 no. 4 of the G-BA’s Psychotherapy Guidelines) (1). Other psychotherapeutic procedures with recommendation grade A are psychoeducation (NNT = 9 in prevention of relapse), family interventions, cognitive remediation (a cognitive training and education process), and social competence training. The various procedures should be offered individually, depending on the indications in each case. eTable 3 shows the matrix of psychotherapeutic and psychosocial treatment procedures that can be offered depending on the indications and individual preferences. New in the revised guidelines is the recommendation (grade B) that CBT also be offered to those who reject antipsychotic drug treatment.

eTable 3. Matrix of the recommendations for psychotherapeutic and psychosocial treatment procedures, with selected underlying source publications, relevant statistical measures, and recommendation grades.

| Positive symptoms | Prevention of relapse | Negative symptoms | Cognitive performance | Social functioning level | General symptoms | |||||||

| Psychoeducation | A | LoE1+ (e13) | ||||||||||

| NNT: 9 [7; 14] | ||||||||||||

| CBT (FEP) | A | LoE1– (e14) | n.d. | LoE1− (e14) | A | LoE1− (e14) | ||||||

| SMD; –0.60 [–0.79; –0.41] | RR = 0.67 [0.24; 1.85] | SMD −0.45 [−0.89; −0.09] | ||||||||||

| CBT (REC) | A | LoE1++ (e15) | A | LoE1++ (e15) | n.d. | LoE1++ (e15) | ||||||

| d = 0.372 [0.228; 0.516] | d = 0.437 [0.171; 0.704] | d = 0.378 [0.154; 0.602] | ||||||||||

|

Metacognitive training |

B | LoE1+ (e16) | ||||||||||

| g = −0.34 [−0.53; −0.15] | ||||||||||||

|

Family interventions |

A | LoE1− (20, e14) | ||||||||||

| RR = 0.58 [0.25; 1.36] | ||||||||||||

|

Systemic therapy |

0 | LoE1− (e17) | ||||||||||

| g = 0.69 [0.39; 0.99] | ||||||||||||

|

Social competence training |

A | LoE1++ (e18) | A | LoE1++ (e18) | ||||||||

| g = 0.218 [0.077; 0.359] | g = 0.252 [0.075; 0.428] | |||||||||||

|

Psychodynamic psychotherapy |

0 | LoE2+ (e19) | ||||||||||

| 6.42 [1.22; 11.61] | ||||||||||||

|

Cognitive remediation |

A | LoE1+ (e20) | A | LoE1+ (e20) | ||||||||

| d = 0.448 [0.306; 0.590] | d = 0.418 [0.216; 0.620] | |||||||||||

|

Supportive treatment |

0 | GA (20) | ||||||||||

| Ergotherapy | 0 | GA (e21) | ||||||||||

|

Art/music therapy |

B | GA (e21) | ||||||||||

| Physical therapy/sport | B | GA (e21) | ||||||||||

CBT, cognitive behavioral therapy; FEP, first-episode psychosis; GA, guideline adaptation; LoE, level of evidence; n.d., no data; REC, relapse

A: recommendation grade A; B: recommendation grade B, 0: recommendation grade 0

The superscripts after LoE show the evidence grade according to SIGN

Management of adverse drug reactions

A large number of preparation-specific adverse drug reactions may be caused by antipsychotics, and these potential side effects must always be borne in mind when prescribing this type of medication. Accordingly, the clinical practice guidelines focus on adverse event–guided prescription of antipsychotic drugs. The following groups of adverse events must be particularly closely respected and monitored:

Motor reactions

Metabolic reactions

Sexual dysfunction/prolactin-associated reactions

Cardiac reactions

Disorders of the hematopoietic system.

Specifically for metabolic reactions, the guidelines group approved new evidence-based recommendations in terms of a stepwise procedure for detection and treatment. eBox 3 defines a general stepwise process for the recognition and treatment of adverse events, while eTable 4 presents concrete recommendations for the detection and treatment of metabolic syndrome, a very common occurrence in persons with schizophrenia. eTable 5 shows the follow-up visits as defined by the guidelines group for persons receiving antipsychotic treatment, and eTable 6 lists the preparation-specific adverse events.

eBOX 3. Detection and management of adverse drug reactions (modified from [1]).

| Step 1: | Information and counseling (recommendation 52) |

| Persons with schizophrenia, their relatives, and other persons of trust should not only have the potential adverse drug reactions explained to them, but also be informed of the symptoms that may occur and the options for their treatment (CCP, 96% strong consensus) | |

| Step 2: | Active inquiry and classification (recommendation 53) |

| Antipsychotic-induced adverse drug reactions should be actively inquired about and documented, and in the event of suspicion, the corresponding evaluation and treatment should be offered (CCP, 100% strong consensus) | |

| Step 3: | Assess whether dose reduction, switch to different medication, or discontinuation is feasible (recommendation 54) |

| Depending on the severity of the antipsychotic-induced adverse drug reactions, and guided by risk/benefit analysis, dose reduction, a switch to another preparation, or discontinuation should be offered (CCP, 100% strong consensus) | |

| Step 4: | Specific treatments |

| The new German clinical practice guidelines suggest specific treatments for many different adverse drug reactions associated with antipsychotics. Special attention is paid to weight gain, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome, for which specific evidence-based recommendations were approved (see eTable 4 for the treatment of metabolic adverse events). |

eTable 4. Detection and treatment of metabolic adverse events (modified from [1]).

| Intervention | Recommendation | Evidence (selected) [95% confidence interval] |

| ►Step 1 Detection and classification (7% rule), check whether dose reduction, a switch to another preparation, or discontinuation is feasible. These strategies must be balanced against the danger of worsening symptoms or relapse. |

52, 53, 54 (all CCP) | Detection according to the 7% rule: – A position paper of the European Psychiatric Association (EPA), the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD), and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) recommends intervention if >7% of weight is gained in the first 6 weeks after initiation of antipsychotic treatment, relative to baseline (e40) Particularly close monitoring of antipsychotics that are known to sometimes lead to significant weight gain (network meta-analysis [33]): – zotepine, olanzapine, sertindole, iloperidone, quetiapine, clozapine, paliperidone, risperidone, asenapine Meta-analysis on switch from olanzapine to aripiprazole/quetiapine: – weight loss of −1.94 kg [−3.90; 0.08] (e41) |

| ►Step 2 In the event of >7% weight gain, offer psychotherapeutic and psychosocial interventions (nutritional counseling, psychoeducation, exercise programs) to prevent weight gain or achieve weight loss. |

55 (A) | Psychosocial intervention/psychotherapy vs. standard treatment (meta-analysis) (e42): – weight loss of −2.56 kg [−3.20; −1.92] Nutritional program vs. control (meta-analysis) (e43): – weight loss in general g = −0.39 [−0.56; −0.21] – weight loss when program was offered at the beginning of antipsychotic treatment g = –0.61 [−1.02; –0.18] |

| ►Step 3 In the event of pronounced weight gain, and after step 2 has taken place, offer off-label metformin (first choice) or topiramate (second choice). Look out for potential interactions and worsening of adverse events due to combination treatments, as well as substance-specific characteristics (e.g., metformin → metabolic acidosis, topiramate → dyscognitive effects) |

56 (A) | Metformin versus placebo (meta-analyses) – weight loss: −3.27 kg [−4.66; −1.89] (e44) – weight loss: −3.17 kg [−4.44; −1.90] (e45) – clozapine subgroup: −3.12 kg [−4.88; −1.37] (e46) Topiramate versus placebo (meta-analyses) – weight loss: −2.83 kg [−4.62; −1.03] (e47) – weight loss: −2.75 kg [−4.03; −1.47] (e48) |

eTable 5. Follow-up visits in antipsychotic treatment (modified from [1]).

| Investigation | Previously | Month | Every month | Every 3 months | Every 6 months | Annually | |||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | ||||||

| Blood count | |||||||||||

| – Other antipsychotics | X | X | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | X |

| – Clozapine | X | XXXX | XXXX | XXXX | XXXX | XX | X | X | – | – | – |

| – Tricyclic antipsychotics*1 | X | X | – | X | – | – | – | – | – | X*3 | – |

| Blood sugar/HbA1c*2, *12 blood lipids | |||||||||||

| – Clozapine, olanzapine | X | X | – | X | – | – | X | – | – | X | |

| – Quetiapine, risperidone | X | X | – | X | – | – | X | – | – | – | X |

| – Other antipsychotics | X | – | – | – | – | – | X | – | – | – | X |

| Kidney parameters | |||||||||||

| – Creatinine/GFR | X | X | – | X | – | – | X | – | – | – | X |

| Liver enzymes | |||||||||||

| – Tricyclic antipsychotics*1 | X | X | – | X | – | – | X | – | – | X*3 | – |

| – Other antipsychotics | X | X | – | X | – | – | X | – | – | X*3 | – |

| ECG (QTc)*4, electrolytes | |||||||||||

| – Clozapine*5,*6 | X | X | – | X | – | – | X | – | – | X*3 | |

| – Other antipsychotics*7, *8 | X | X | – | – | – | – | X | – | – | – | X |

| – Sertindole*9 | X | X | – | X | – | – | X | – | X | – | – |

| – Thioridazine, pimozide | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | – | – | – |

| EEG*10 | |||||||||||

| – Clozapine | X | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| – Other antipsychotics | (X) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Heart rate/pulse | X | X | – | X | – | – | X | – | X | – | – |

| Motor reactions | X | X | X | X | – | X*3 | – | ||||

| Sedation | X | X | X | X | – | X*3 | – | ||||

| Sexual dysfunction | X | X | X | X | – | X*3 | – | ||||

| Body weight (BMI)*11 | X | X | X | X | – | – | X | – | X | – | – |

| Echocardiography*13 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Prolactin*14 | X | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Pregnancy test | X | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

This table from the new German clinical practice guidelines (1) was compiled on the basis of (e49, e50) and adapted in an expert consensus process. It should be noted that these are general recommendations. The scope of investigation can be adapted to the risk, oriented on the data in the product information sheet, so that the dose can be increased or decreased in the individual patient. The crucial factors in risk-based adaptation are: comorbidities, accumulation of risk factors, combination treatments, dose escalation, age, and occurrence of organ-specific symptoms. Particularly in a steady-state situation with unchanged risk and medication profiles, the interval between follow-up visits can be increased, taking account of the relevant product information. The recommended diagnostic procedures in persons with a first episode are presented in module 2 of the long version of the new German clinical practice guidelines on schizophrenia.

X: Necessary number of routine follow-up visits. If a single visit in month 1 is recommended, the measurement can take place between week 3 and week 6—the investigation in the first month relates to the usual time to full dosage of an antipsychotic. X = number of follow-up visits in period concerned (e.g., X = one investigation in given month; XXXX = four investigations in given month).

*1 NB: The SGAs olanzapine, quetiapine and zotepine are, with regard to chemical structure, also tricyclics.

*2 Supplemented if needed by 24-h blood sugar profile or glucose tolerance test, especially with clozapine and olanzapine

*3 In steady-state unremarkable constellations, visits annually or even less frequently may suffice.

*4 Absolute values of >440 ms (men) or >450 ms (women) and medication-induced increases >60 ms are a cause for concern. With a QTc time >480–520 ms or an increase in QTc time >60 ms, the original antipsychotic should be discontinued and a new antipsychotic started.

*5 Toxic-allergic myocarditis has been described with clozapine; therefore, those taking clozapine should undergo ECG monitoring at shorter intervals and, if thought advisable, have cardiac echocardiography on the occurrence of cardiac symptoms and fever or after 14 days’ treatment.

*6 On new administration of clozapine: carry out ECG and determine levels of CRP and troponin I, or alternatively measure T value, blood pressure, pulse, and temperature, before starting clozapine; then measure CRP, troponin I, and T value weekly for 4 weeks and blood pressure, pulse, and temperature every 2 days for 4 weeks.

*7 In the presence of pre-existing or new cardiac symptoms or a significant prolongation of QTc time, cardiological examination is necessary; this will also establish at what intervals ECG needs to be carried out in the longer term.

*8 More frequent follow-up is advisable for all patients >60 years, and this may also be thought necessary in the presence of cardiac risk factors; more frequent ECG monitoring is recommended with ziprasidone, perazine, fluspirilene, and high-potency butyrophenones, as well as in the event of QTc time prolongation and in combination treatment involving any other substances that may prolong the QTc time.

*9 With sertindole, ECG (preferably in the morning) is recommended before commencement of treatment, after steady state has been achieved (3 weeks) or at a dose of 16 mg, after 3 months, and subsequently at 3-month intervals, before and after every dose increase during maintenance treatment, and after initiation or dose increase of any accompanying medication that could lead to an elevation of the sertindole concentration.

*10 EEG before the initiation of clozapine treatment. EEG should be one of the first diagnostic procedures in the presence of signs of an organic process (see module 2). EEG monitoring during the disease course if there are clinical signs of a seizure. More frequent EEG also in the presence of pre-existing cerebral insult, elevated susceptibility to seizures, and, if deemed necessary, before and during antipsychotic treatment if very high dosages (combinations) are being used, as well as unexplained changes in state of consciousness (differential diagnosis: non-convulsive status).

*11 Measurements of waist size are recommended in addition to calculation of BMI; additionally, monthly weight checks by the patient him-/herself.

*12 Only blood sugar and HbA 1C, in the case of abnormal findings and (*2) consider treatment and monthly follow-up; in presence of metabolic syndrome, monthly blood sugar measurements and (* 2).

*13 Occurrence of dyspnea or unexplained exhaustion during antipsychotic treatment should be investigated with cardiac ultrasound. This is particularly important for treatment with dibenzodiazepines, dibenzothiazepines, or thienobenzodiazepines.

*14 The NICE guidelines (20) recommend determination of prolactin before commencement of antipsychotic treatment. During the disease course, prolactin should be determined if the corresponding symptoms occur.

eTable 6. The typical adverse effects of antipsychotics, according to the revised clinical practice guidelines (1).

| Akathisia | Parkinsonoid | Tardive dyskinesia | Weight gain | Metabolic changes | Diabetes mellitus | Obstipation | Hyperprolactinemia | Dysmenorrhea/ amenorrhea | Sexual dysfunction | Sedation | Orthostatic dysregulation | Prolongation of QT time | Increased transaminases/bilirubin | Blood count changes | Agranulocytosis/pancytopenia | Epileptic seizures | MNS | Pneumonia | |

| Amisulpride | + | + | + | 0/+ | 0/+ | 0/+ | ++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | 0/+ | 0/+ | ++ | 0/+ | 0/+ | 0/+ | 0/+ | ? | 0 |

| Aripiprazole | ++ | + | + | 0/+ | 0/+ | 0/+ | 0/+ | 0/+ | 0/+ | 0/+ | 0/+ | 0/+ | 0/+ | 0/+ | 0/+ | 0/+ | 0/+ | 0/+ | ? |

| Cariprazine | ++ | ++ | + | 0/+ | 0/+ | 0/+ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/+ | 0/+ | ++ | 0/+ | 0/+ | 0/+ | 0/+ | ? |

| Clozapine | + | 0 | 0 | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | 0/+ | 0/+ | + | +++ | +++ | + | ++ | + | ++ | ++ | 0/+ | ++ |

| Flupentixol | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | + | + | ++ | 0/+ | 0/+ | + | ++ | ++ | 0/+ | + | 0/+ | 0/+ | + | 0/+ | ? |

| Fluphenazine | +++ | +++ | +++ | 0/+ | 0/+ | 0/+ | + | 0/+ | 0/+ | + | ++ | ++ | + | + | + | 0/+ | ++ | 0/+ | ? |

| Haloperidol | +++ | +++ | +++ | + | 0/+ | 0/+ | + | +++ | ++ | ++ | + | 0 | 0/+ | ++ | + | 0/+ | 0/+ | + | ? |

| Lurasidone* | +/++ | +/++ | + | 0/+ | 0/+ | 0/+ | + | + | + | + | + | 0/+ | 0/+ | + | 0/+ | 0/+ | 0/+ | 0/+ | ? |

| Melperone | 0/+ | 0/+ | 0/+ | 0/+ | 0/+ | 0/+ | 0/+ | 0/+ | 0/+ | 0/+ | ++ | ++ | + | 0/+ | + | 0/+ | ? | 0/+ | ? |

| Olanzapine | + | 0/+ | 0/+ | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | + | 0 | + | +/++ | ++ | 0/+ | + | 0/+ | 0/+ | 0/+ | 0/+ | + |

| Paliperidone | + | ++ | + | ++ | + | + | ++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | 0/+ | + | + | ++ | 0/+ | 0/+ | 0/+ | 0/+ | ? |

| Perphenazine | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | ? | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 0/+ | 0/+ | 0/+ | 0/+ | 0/+ | ? |

| Pipamperone | ++ | + | 0/+ | ? | ? | + | ? | 0/+ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | + | + | 0/+ | 0/+ | 0/+ | ? |

| Quetiapine | + | 0/+ | 0/+ | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | 0/+ | 0/+ | + | ++² | ++² | + | ++ | ++ | 0/+ | 0/+ | 0/+ | + |

| Risperidone | + | ++ | + | ++ | + | + | ++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | + | + | + | + | 0/+ | 0/+ | 0/+ | 0/+ | + |

| Sertindole | + | 0/+ | + | ++ | + | + | + | + | + | + | 0/+ | + | +++ | 0/+ | 0/+ | 0/+ | 0/+ | 0/+ | ? |

| Ziprasidone | +/++ | + | + | 0/+ | 0/+ | 0/+ | 0/+ | + | 0/+ | + | + | 0/+ | ++ | + | 0/+ | 0/+ | 0/+ | ? | ? |

| Zuclopenthixol | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | + | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | +++ | ++ | 0/+ | 0/+ | 0/+ | 0/+ | + | 0/+ | ? |

Adverse effects of antipsychotics (reproduced in full from the revised clinical practice guidelines (1). The table was compiled on the basis of the CINP Schizophrenia Guidelines and the references contained therein (e51) and on the previous AWMF guidelines on schizophrenia (39); adaptation took place in an expert consensus process based on product information sheets and recently published meta-analyses (28, 32). Gaps in the data were filled using the product information sheets and the standard reference for psychopharmacology in Germany (e49). The data on pneumonia were extracted from a meta-analysis (e34). Unexpected adverse effects may occur with widespread use of the preparations, so pharmacovigilance (seeeTable 5) is mandatory.

*Lurasidone is approved for the treatment of schizophrenia in Germany, but prescriptions for it cannot be charged to the National Association of Statutory Health Insurance Funds.

0 = None, (+) = sporadic or no significant difference from placebo, + = rare, ++ = occasional, +++ = frequent, ? = data insufficient for estimation of frequency. Please note that these are not systematically compiled quantitative estimates of incidence, but rather qualitative estimates based on clinical experience, taking account of the sources mentioned above. MNS, Malignant neuroleptic syndrome

Problems in coordination of care

In practice, various problems may arise in coordination among caregivers. These can affect the transition from inpatient care to the post-hospital setting (day clinic, outpatient clinic, specialist medical care in the community), coordination in the area of outpatient care (specialist-centered treatment, psychotherapists, primary-care physicians, other parties), or the challenge of hospital admission in an acute phase of illness characterized by decreased or lacking insight. The new module 5 (coordination of care) is dedicated to these and other aspects of optimized organization of patient care. For example, one recommendation (grade CCP) is that whenever treatment by a multiprofessional team is required or intensification of psychopharmacological, psychotherapeutic, or psychosocial measures becomes necessary, it should be considered whether transfer to a specialized and multiprofessional psychiatric hospital outpatient service (Psychiatrische Institutsambulanz, PIA), or to a community care network in which more complex treatment programs are available if needed, might be beneficial (1). In another recommendation (CCP, strong consensus) the guidelines group defined indications for hospital admission. Inpatient treatment should be offered to all patients who would benefit from the diagnostic and therapeutic resources available in the hospital setting or from the special protection offered by the hospital in the case of acute danger to themselves or others. This would include, for example:

Treatment resistance

Acute suicidality

States of severe delusion or anxiety

Lack of proper nutrition or self-care

Marked apathy or adynamia

Domestic circumstances hindering remission and recovery

Treatment of complicating comorbidities

Complex treatment situations

Unexplained somatic comorbidities

Severe adverse drug reactions

Other problems not amenable to outpatient care.

This incomplete list makes it clear that in patients who present acute danger to themselves or others, or lack insight, one must consider hospitalization under the terms of the Care Act and the laws of the federal state concerned. It also becomes apparent that the guidelines group has defined factors such as the lack of options for care, but most importantly somatic and mental comorbidities, as indications for admission to the hospital. These latter points routinely lead to discussions with the medical service of the health insurance providers in Germany (MDK) on whether hospital beds are being utilized unnecessarily.

Summary

The revised German clinical practice guidelines on schizophrenia contain recommendations on both the diagnostic work-up and the pharmacological, psychotherapeutic, and psychosocial treatment of persons with schizophrenia over their entire life span. To conform with the guidelines, the treatment of persons with schizophrenia must be multiprofessional with a basic attitude of empathy, respect, and appreciation on the part of the caregivers. The aim is to render those affected able to enjoy “full and equal enjoyment of all human rights and fundamental freedoms” (article 1, UN CRPD).

BOX 2. Findings of selected meta-analyses published after the end of the literature survey.

A dose–response meta-analysis of 68 studies calculated the so-called 95% effective dose (the level at which no additional effect can be anticipated from raising the dose) for the acute treatment of psychotic symptoms based on recent data for all relevant antipsychotic drugs: for example, amisulpride 537 mg/day, aripiprazole 11.5 mg/day, olanzapine 15.2 mg, haloperidol 6.3 mg/day (31). A new network meta-analysis of 402 randomized controlled trials (RCT) with 53 463 participants expanded the findings of the network meta-analysis used for the clinical practice guidelines (32) with regard to the differences among antipsychotics in terms of efficacy and tolerability. Six years after the first meta-analysis of this kind, the new publication confirmed that the differences in the efficacy of an antipsychotic preparation are far smaller than the differences in its adverse effect profile (33). As for the drug safety of antipsychotics, a meta-analysis (596 RCT with 108 747 participants) investigated the endpoint of short-term mortality, i.e., death in the period from 1 day to >13 weeks. For persons with schizophrenia, treatment with an antipsychotic drug showed no higher mortality than placebo (odds ratio 0.69, 95% confidence interval [0.35; 1.35]), while elevated mortality was found in persons with dementia and in elderly participants (34). Further new meta-analyses have shown, even with close scrutiny of the methods, a beneficial effect of add-on cognitive behavioral therapy on positive symptoms (SMD = -0.29; [-0.55; -0.03]) (35) and low variability of treatment response to antipsychotics compared with placebo (variation coefficient = 0.86, p <0.001) (36), and have also confirmed that especially olanzapine and clozapine can induce considerable weight gain (33, 37). According to the latest data, aripiprazole, brexpiprazole, cariprazine, haloperidol, lurasidone, and ziprasidone have more favorable metabolic profiles than other antipsychotic (33, 37).

Key Messages.

Schizophrenia is one of the most severe mental illnesses and does huge personal, social, and functional damage not only to the person affected but also to their relatives or reference persons.

Pharmacological, psychotherapeutic, and psychosocial treatments should be offered at all times. Timely detection of somatic comorbidities reduces the general morbidity and mortality.

In all phases of the disease, smooth cooperation between the person affected, their relatives, and other reference persons and the multiprofessional treatment team is the key to successful treatment.

Antipsychotics have the most comprehensive evidence for effective reduction of the symptom burden and for prevention of relapse. Cognitive behavioral therapy is the most widely investigated non-pharmacological procedure and should always be offered together with medication.

Despite their poorer foundation in evidence, other psychotherapeutic and psychosocial treatment procedures, together with elements such as peer-to-peer support, trialog, and outreach, form an important part of the modern treatment of persons with schizophrenia.

eBOX 2. Relevant somatic comorbidities (derived from [1] and expanded).

The following somatic disorders occur at statistically significantly higher rates in persons with schizophrenia than in the healthy comparison population (3, 4, e22– e29). The figures in parentheses are prevalence rates, incidences, or odds ratios (OR) from meta-analyses or cohort studies. It should be noted that most of these publications were not population studies, hardly any data from the German healthcare system are available, and that many of the studies were carried out in inpatients. Therefore, the data on prevalences, risk, and incidences are somewhat uncertain.

Cardiovascular and metabolic diseases

Obesity (OR = 4.43; 95% confidence interval [2.52; 7.82]) (e30)

Arterial hypertension (OR = 1.36 [1.21; 1.53]) (e30)

Diabetes mellitus type 2 with resulting diseases (10.75% [7.44; 14.5]) (e31)

Hyperlipidemia (41.1% [36.5; 45.7]) (e32)

Cerebrovascular disease (OR = 1.63 [1.19; 2.24]) (e22)

Coronary heart disease (11.8% [7.1; 19.0]) (e22)

Metabolic syndrome (33.4% [30.8; 36]) (e28)

Lung diseases

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (OR = 1.57 [1.44; 1.72]) (e33)

Lung infections (incidence 1.12 [1.07; 1.18] cases per 100 person years) (e34)

Cancers (RR = 0.90 [0.81; 0.99])*1 (e29)

Lung

Gastrointestinal tract

Breast

Hematopoietic system

Other sites (e.g.,bladder)

Other diseases

-

Infections*2

Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (prevalence 15.4% [5.3%; 37.1%]) (e36)

Epilepsy (prevalence of psychotic disorders in epilepsy 5.6% [4.8%; 6.4%]) (e37)

Poor dental hygiene/caries (mean difference 7.66 [3.27; 12.27]) (e38)

Gastrointestinal ulcers (incidence rate 1.27 [1.06; 1.52]) (e39)*3

*1 The findings for cancer are not clear. A meta-analysis shows a reduced relative risk (RR = 0.90 [0.81; 0.99]) for cancers in general in persons with schizophrenia (e29). Owing to the generally decreased life-expactancy, neoplasms of advanced age are found less frequently in persons with schizophrenia than in the general population (survival bias), while neoplasms (lung cancer) connected with substance use (e.g., tobacco or alcohol) occur more frequently.

*2 Prevalence figures for Europe

*3 Not a meta-analysis; population-based study from Taiwan

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by David Roseveare

Clinical practice guidelines in the Deutsches Ärzteblatt, as in numerous other specialist journals, are not subject to a peer review procedure, since such guidelines represent texts that have already been evaluated, discussed, and broadly agreed upon multiple times by experts (peers).

Acknowledgments

We thank all the individuals and groups whose long-term, continuous, and constructive commitment made it possible to draw up this guideline. Thanks are due to the German Association for Psychiatry, Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics for its substantive, structural and financial support of the entire guideline process, without which revision of the guideline could not have been achieved.

We are particularly grateful to Prof. Kopp (AWMF-Institute for Medical Knowledge Management) for her balanced moderation and advice during the entire guideline development process.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

Prof. Hasan has received consultancy honoraria from Lundbeck, Otsuka, Janssen, and Roche as well as speaker’s fees from Desitin, Lundbeck, Otsuka and Janssen. He is the editor of the WFSBP guideline on schizophrenia. He is a member of an IFCN guideline group on rTMS treatment of neurological and mental illnesses.

Prof. Falkai has received consultancy honoraria from Janssen, Richter Pharma, Servier, and Sage as well as speaker’s fees from Otsuka, Lundbeck, Janssen, and Richter Pharma.

Prof. Gaebel is a member of the Lundbeck International Neuroscience Foundation (LINF).

Dr. Lehmann states that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychiatrie und Psychotherapie, Psychosomatik und Nervenheilkunde (DGPPN) S3-Leitlinie Schizophrenie. AWMF-Register Nr. 038-009. www.awmf.org/leitlinien/detail/ll/038-009.html (last accessed on 15 March 2019) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simon GE, Stewart C, Yarborough BJ, et al. Mortality rates after the first diagnosis of psychotic disorder in adolescents and young adults. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75:254–260. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.4437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Plana-Ripoll O, Pedersen CB, Agerbo E, et al. A comprehensive analysis of mortality-related health metrics associated with mental disorders: a nationwide, register-based cohort study. Lancet. 2019;394:1827–1835. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32316-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeHert M, Correll CU, Bobes J, et al. Physical illness in patients with severe mental disorders I. Prevalence, impact of medications and disparities in health care. World Psychiatry. 2011;10:52–77. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2011.tb00014.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Hert M, Cohen D, Bobes J, et al. Physical illness in patients with severe mental disorders. II. Barriers to care, monitoring and treatment guidelines, plus recommendations at the system and individual level. World Psychiatry. 2011;10:138–151. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2011.tb00036.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caldwell CB, Gottesman II. Schizophrenics kill themselves too: a review of risk factors for suicide. Schizophrenia Bull. 1990;16:571–589. doi: 10.1093/schbul/16.4.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siris SG. Suicide and schizophrenia. J Psychopharmaco. 2001;15:127–135. doi: 10.1177/026988110101500209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meltzer HY. Suicide in schizophrenia, clozapine, and adoption of evidence-based medicine. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:530–533. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pompili M, Amador XF, Girardi P, et al. Suicide risk in schizophrenia: learning from the past to change the future. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2007;6 doi: 10.1186/1744-859X-6-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pompili M, Lester D, Grispini A, et al. Completed suicide in schizophrenia: evidence from a case-control study. Psychiatry Res. 2009;167:251–257. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hasan A, Falkai P, Wobrock T, et al. World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for biological treatment of schizophrenia Part 3: update 2015 management of special circumstances: depression, suicidality, substance use disorders and pregnancy and lactation. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2015;16:142–170. doi: 10.3109/15622975.2015.1009163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nordentoft M, Jeppesen P, Abel M, et al. OPUS study: suicidal behaviour, suicidal ideation and hopelessness among patients with first-episode psychosis One-year follow-up of a randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 2002;43:s98–s106. doi: 10.1192/bjp.181.43.s98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crump C, Winkleby MA, Sundquist K, Sundquist J. Comorbidities and mortality in persons with schizophrenia: a Swedish national cohort study. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170:324–333. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12050599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buckley PF, Miller BJ, Lehrer DS, Castle DJ. Psychiatric comorbidities and schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bull. 2009;35:383–402. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychiatrie und Psychotherapie, Psychosomatik und Nervenheilkunde (DGPPN) S3-Leitlinie: Screening, Diagnostik und Behandlung des schädlichen und abhängigen Tabakkonsums 2015. www.awmf.org/leitlinien/detail/ll/076-006.html (last accessed on 19 January 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hunt GE, Large MM, Cleary M, Lai HMX, Saunders JB. Prevalence of comorbid substance use in schizophrenia spectrum disorders in community and clinical settings, 1990-2017: systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;191:234–258. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fazel S, Khosla V, Doll H, Geddes J. The prevalence of mental disorders among the homeless in western countries: systematic review and meta-regression analysis. PLoS Med. 2008;5 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychiatrie und Psychotherapie, Psychosomatik und Nervenheilkunde (DGPPN) S3-Leitlinie Schizophrenie: Leitlinienreport. www.awmf.org/uploads/tx_szleitlinien/038-009m_S3_Schizophrenie_2019-03.pdf (last accessed on 19 January 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 19.Richardson WS, Wilson MC, Nishikawa J, Hayward RS. The well-built clinical question: a key to evidence-based decisions. ACP journal club. 1995;123:A12–A13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) NICE clinical guideline 178 - Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: treatment and management - Issued: February 2014, last modified: March 2014. guidance.nice.org.uk/cg178 (last accessed on 27 December 2019) [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Psychosis and schizophrenia in children and young people: recognition and management. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK299073/ (last accessed on 19 January 2020) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Violence and aggression: short-term management in mental health, health and community settings 2015. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng10 (last accessed on 19 January 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) SIGN 131. Management of schizophrenia. A national clinical guideline 2013. www.sign.ac.uk/sign-131-management-of-schizophrenia (last accessed on 14 July 2019) [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychiatrie und Psychotherapie, Psychosomatik und Nervenheilkunde (DGPPN) S3 Leitlinie Psychosoziale Therapien bei schweren psychischen Erkrankung - 2013er Version und Teile der revidierten 2018er Version lagen der Leitliniengruppe vor. 2013/18. www.awmf.org/leitlinien/detail/ll/076-001.html (last accessed on 19 January 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychiatrie und Psychotherapie, Psychosomatik und Nervenheilkunde (DGPPN) Screening, Diagnose und Behandlung alkoholbezogener Störungen: Springer; 2016. www.awmf.org/leitlinien/detail/ll/038-020.html (last accessed on 19 January 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gaebel W. Status of psychotic disorders in ICD-11. Schizophr Bull. 2012;38:895–898. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leucht S, Tardy M, Komossa K, et al. Antipsychotic drugs versus placebo for relapse prevention in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2012;379:2063–2071. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60239-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leucht S, Leucht C, Huhn M, et al. Sixty years of placebo-controlled antipsychotic drug trials in acute schizophrenia: systematic review, bayesian meta-analysis, and meta-regression of efficacy predictors. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174:927–942. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.16121358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Uchida H, Suzuki T, Takeuchi H, Arenovich T, Mamo DC. Low dose vs standard dose of antipsychotics for relapse prevention in schizophrenia: meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37:788–799. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gallego JA, Bonetti J, Zhang J, Kane JM, Correll CU. Prevalence and correlates of antipsychotic polypharmacy: a systematic review and meta-regression of global and regional trends from the 1970s to 2009. Schizophr Res. 2012;138:18–28. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leucht S, Crippa A, Siafis S, Patel MX, Orsini N, Davis JM. Dose-response meta-analysis of antipsychotic drugs for acute schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2019 doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.19010034. appiajp201919010034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leucht S, Cipriani A, Spineli L, et al. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 15 antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet. 2013;382:951–962. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60733-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]