Graphical Abstract

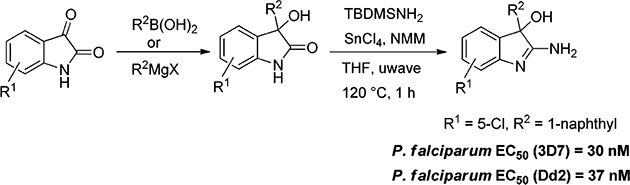

The development of a concise strategy to access 2-amino-3-hydroxy-indoles, which are disclosed as novel antimalarials with potent in vivo activity, is reported. Starting from isatins the target compounds are synthesized in 2 steps and in good yields via oxoindole intermediates by employing tert-butyldimethylsilyl amine (TBDMSNH2) as previously unexplored ammonia equivalent.

Malaria is the most deadly parasitic infectious disease with an estimated 300–500 million cases and a death toll of 0.8–1.2 million in 2008 alone.1Of the four Plasmodium species that are relevant for humans, P. falciparum accounts for most of the fatalities.1These already grim statistics are likely to become even grimmer as P. falciparum strains that are resistant to commonly used antimalaria chemotherapeutic agents emerge and spread throughout Africa and parts of Asia.

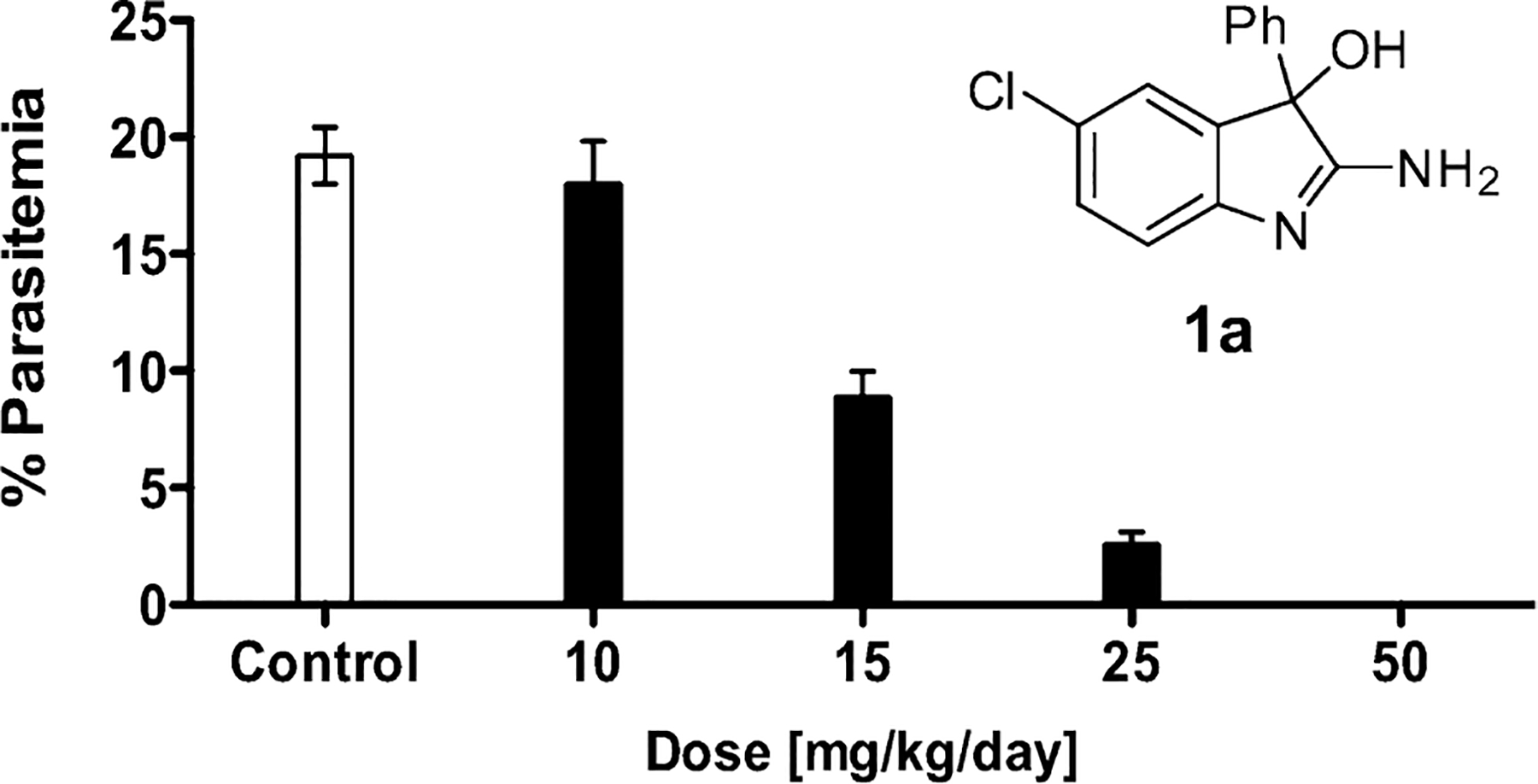

The most recent antimalarial drug class was introduced in 19962 In an effort to address the urgent need for new drugs, especially ones with new cellular targets or chemo types that could delay the emergence of resistance, we have screened small-molecule libraries for novel, drug-like compounds with whole-cell antimalarial activity and limited susceptibility to established mechanisms of drug resistance.3 Very recently, two similar efforts have also been reported.4,5 Out of ~ 79,000 compounds,6 104 inhibitors with nanomolar activity against drug-sensitive (3D7) and multidrug-resistant (Dd2, HB3) P. falciparum strains were identified.3 One of the hits, the 2-amino-5-chloro-3-hydroxy-3-phenylindole 1a (see Figure 1) was particularly attractive because of its unusual and compact 2-amino-3-hydroxy-indole core structure. In addition, compound 1a achieved excellent exposure in mouse pharmacokinetic studies, and more importantly, when tested in a 4-day suppressive P. berghei mouse model 1a demonstrated very good in vivo efficacy,7 causing a dose dependent decrease in parasitemia with undetectable levels of parasites at the highest dose tested and no signs of adverse side effects (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

In vivo antimalaria activity of 2-aminoindole 1a. Following inoculation of Swiss Albino mice with P. berghei parasites, 1a was administered i.p. once daily for 4 days, and parasitemia was determined on day 5.

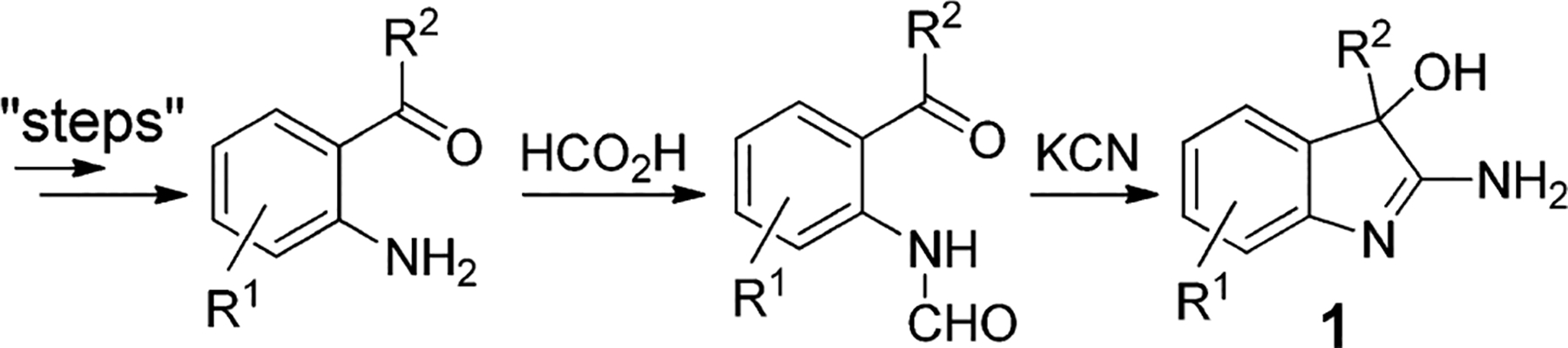

Encouraged by this promising in vivo activity we began to explore and optimize this compound class. A thorough literature survey revealed that 2-amino-3-hydroxy-indoles are virtually unexplored for biological activity, which we suspect results at least in part from the limited synthetic methodology to access this class. To date, four distinct approaches have been reported.8–11We found the methods reported by Bell et al. to prepare the 2-amino-3-hydroxy-indoles Via reaction of KCN with formylated or dichloroacylated 2-aminobenzophenones to be the most appropriate (Scheme 1).9

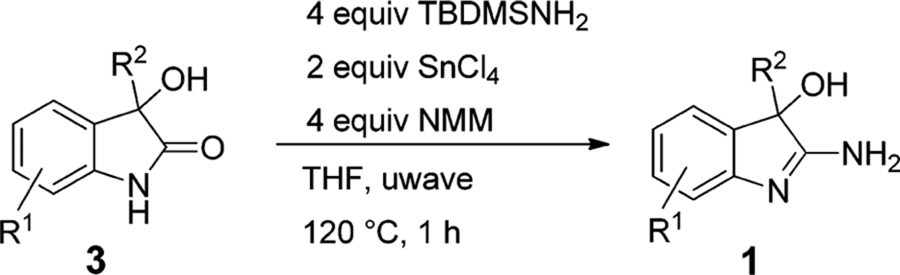

Scheme 1.

Traditional Synthetic Strategy to Access 2-Amino-3-hydroxy-indoles via Cyanohydrins

Unfortunately, this strategy, although readily scalable and attractive for process scale syntheses, is limited for early stage exploratory medicinal chemistry due to the lack of commercially available 2-aminobenzophenones and the inherent lack of enantioselectivity. As a result, we developed a general, short and efficient method that would (a) provide analogues in quantities that satisfy early stage drug discovery requirements, (b) tolerate a wide variety of functional groups, (c) begin with commercially available diversely functionalized building blocks, and (d) avoid the use of cyanide while (e) offering the potential to enantioselectively access 2-aminy-3-hydroxy-indoles.

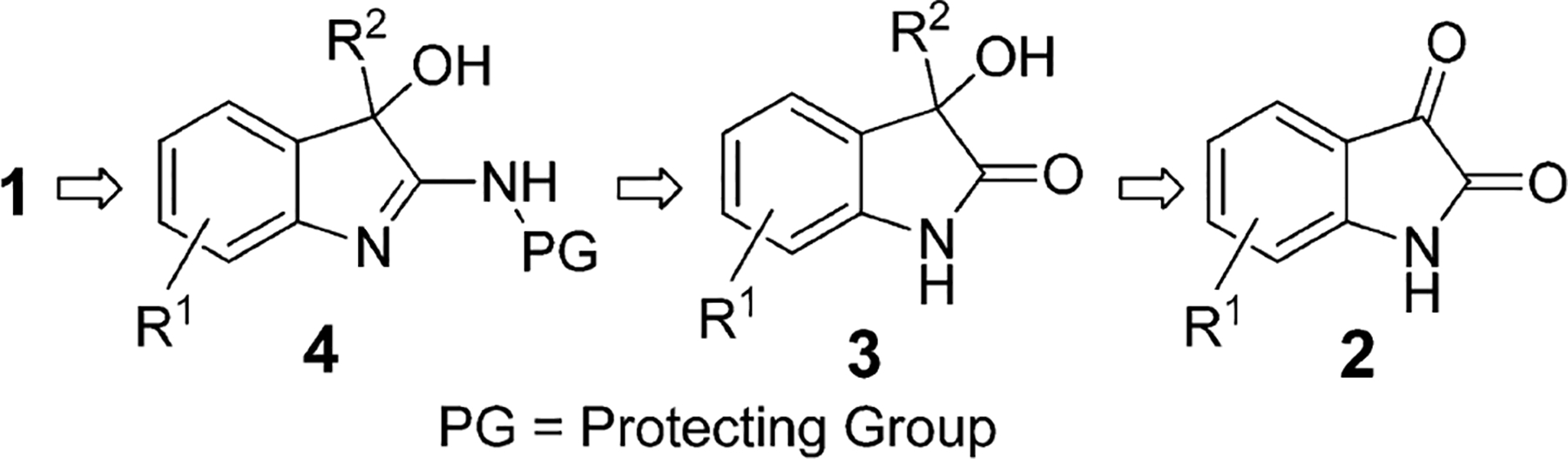

We envisioned a three-step reaction sequence starting from isatins, which are widely available and inexpensive starting materials as shown in Scheme 2.

Scheme 2.

Retrosynthetic Analysis Starting from Isatin (2)

Grignard addition or Rh-catalyzed addition12 of boronic acids to isatin 2 would give 3-hydroxy-3-aryl-oxindole 3. Oxindole 3 could then react with a protected ammonia equivalent (e.g., allylamine) to yield the corresponding protected 2-amino-3-hydroxy-indole 4, which on deprotection would result in the desired 2-amino-3-hydroxy-indole 1. Furthermore, boronic acids13 and electron-rich arenes14 can be added to isatins with high enantioselectivity. This method would also allow access to 2-amino-3-hydroxy-indoles enantioselectively.

On the basis of the well-precedented nature of the first step, we directed our efforts toward the conversion of 3-hydroxyoxindoles 3 to allyl-protected 2-amino-3-hydroxy-indoles 4. We were somewhat encouraged by variable conversions (~30–50%) obtained upon heating 5-chloro-3-hydroxyoxindole 3a with an excess of allylamine in the presence of 5 mol % of PTSA and 4 Å molecular sieves.15 Attempts to increase the yields by employing other drying agents such as Na2SO4, MgSO4 or the use of Dean-Stark apparatus were not successful. We anticipated that better conversions could be achieved with the use of a Lewis acid, which not only would catalyze the transformation but would also efficiently entrap the water formed. Exploring a set of Lewis acids confirmed our hypothesis, with both SnCl4 and Ti(OiPr)4 efficiently and more importantly, reproducibly promoting the conversion of 3a to 4a (Scheme 3). Furthermore, while microwave conditions reduced the reaction times from 12–18 h to 40–60 min, the addition of NMM (N-methyl morpholine) as an acid scavenger allowed the amine coupling partner to be used in nominal amount.

Scheme 3.

Amidations with Allylamine and Triphenylsilylamine Conditionsa

a Conditions: (a) excess allylamine for 4a, (b) 2 equiv of Ph3SiNH2 and 4 equiv NMM for 5.

Disappointingly, the deprotection of the allyl group in 4a proved challenging despite the plethora of deallylation protocols for amines and amides.16,17

Next, we turned our attention to identifying an ammonia equivalent that would allow for more facile deprotection. On the basis of literature precedents of employing a silylated ammonia equivalent in unrelated transformations,18 we decided to explore commercially available Ph3SiNH2. Unexpectedly, as shown in Scheme 3, the reaction of 3a with Ph3SiNH2 under the optimized conditions produced O-silylated 2-amino-3-hydroxy-indole 5, in 60% yield while only trace amounts of the desired desilylated product 1a were observed. Aminoindole 5 is probably formed by the intramolecular migration of the silyl group. Attempts to desilylate 5 using TBAF or other fluoride sources resulted in hydrolysis of 5 and in recovery of the original hydroxyoxindole starting material 3a.

Encouraged by the finding that a silylamine appears well-suited to install the desired amine functionality, we suspected that less sterically demanding analogues of Ph3SiNH2 such as tert-butyldimethylsilyl amine (TBDMSNH2) might allow deprotection under condition that would prevent hydrolysis of the amine. Pleasingly, we were able to directly isolate the desired 2-aminoindole product 1a in 60% isolated yield. The structure of 1a was unambiguously established by X-ray analysis revealing that the newly installed substituent appears to favor the tautomer with an exoamine rather than an exoimine geometry (see Supporting Information).

Although TBDMSNH2 has been utilized in the context of its ligand attributes for metal complexes,19–21 this is, to our knowledge, the first report on the application of TBDMSNH2 in organic synthesis.

The synthetic utility of this novel SnCl4-promoted amidation reaction with TBDMSNH2 as an ammonia surrogate was then explored using a series of substituted 3-hydroxy-oxindoles. A variety of functional groups in the indole ring, including halogens, nitro, and alkyl ether are well tolerated in the amidation process (Table 1). The amidation reaction worked equally well under Ti(OiPr)4 promoted conditions.

Table 1.

Direct Conversion of 3 to 1 with TBDMSNH2

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | R1 | R2 | yield (%)a | EC50 (nM) | |

| 3D7 | Dd2 | ||||

| a | 5-CI | Ph | 60 (56)b | 216 | 507 |

| b | 5-I | Ph | 64 | 289 | 338 |

| c | 5-CI | o-OMePh | 43 | 24 | 57 |

| d | 5-CI | 45 | 1160 | 1127 | |

| e | 5-CI |  |

58 | 104 | 465 |

| f | 5-F | p-OMePh | 52 | 85 | 359 |

| g | 5-CI | iso-butyl | 50 | 232 | 270 |

| h | 5-CI | m-CO2MePh | 38 | 783 | 1578 |

| i | 5-CI | m-AcPh | 30b | 529 | 1525 |

| j | 5-CI | CH2-(o-tolyl) | 53 | 63 | 139 |

| k | 4-Br | CH2Ph | 51 | >5000 | >5000 |

| l | 5-OMe | Ph | 49 (48)b | 24 | 385 |

| m | H | o-tolyl | 53 | 112 | 152 |

| n | 5-CI | 1-naphthyl | 67 | 30 | 37 |

| o | 5-NO2 | Ph | 30b | >5000 | >5000 |

| p | 5-CI | 3’-(5’-OMe-indolyl) | 40b | >5000 | >5000 |

| q | 5-CI | p-SO2NH2Ph | 45b,c | >5000 | >5000 |

| rd | H | Ph | 39 | >5000 | >5000 |

| Chloroquine | 16 | 216 | |||

Isolated yields.

Ti(OiPr)4 was used instead of SnCl4 and NMM.

TBS-protected aminoindole was formed, which on treatment with HF/pyridine gave 1q; yield reported is over two steps.

The indole nitrogen is methylated (see Supporting Information).

The substrate scope with respect to the substituent at the 3-position of oxindoles was also found to be broad. Thus, the aryl group at the 3-position possessing functional groups such as ester (entry h) and alkyne (entry d) could be employed in this process. In the case of an aryl group substituted with an enolizable ketone, the use of Ti(OiPr)4 in lieu of SnCl4 was critical for the success of the reaction (entry i, Table 1), as is the indole with free nitrogen as R2 (entry p).

Interestingly, an aryl group substituted with the sulfonamide group yielded the aminoindole with TBDMS group on sulfonamide nitrogen with this method. However, deprotection with HF/pyridine gave the aminoindole 1q (entry q). It is worth noting that several of these 2-amino-3-hydroxy-indoles would be difficult to access or would require functional group manipulations via a cyanohydrin route significantly lengthening the synthesis. In addition, our methodology allowed for direct access of N(1)-alkyl iminoindole using the corresponding oxindole as starting material (entry r).

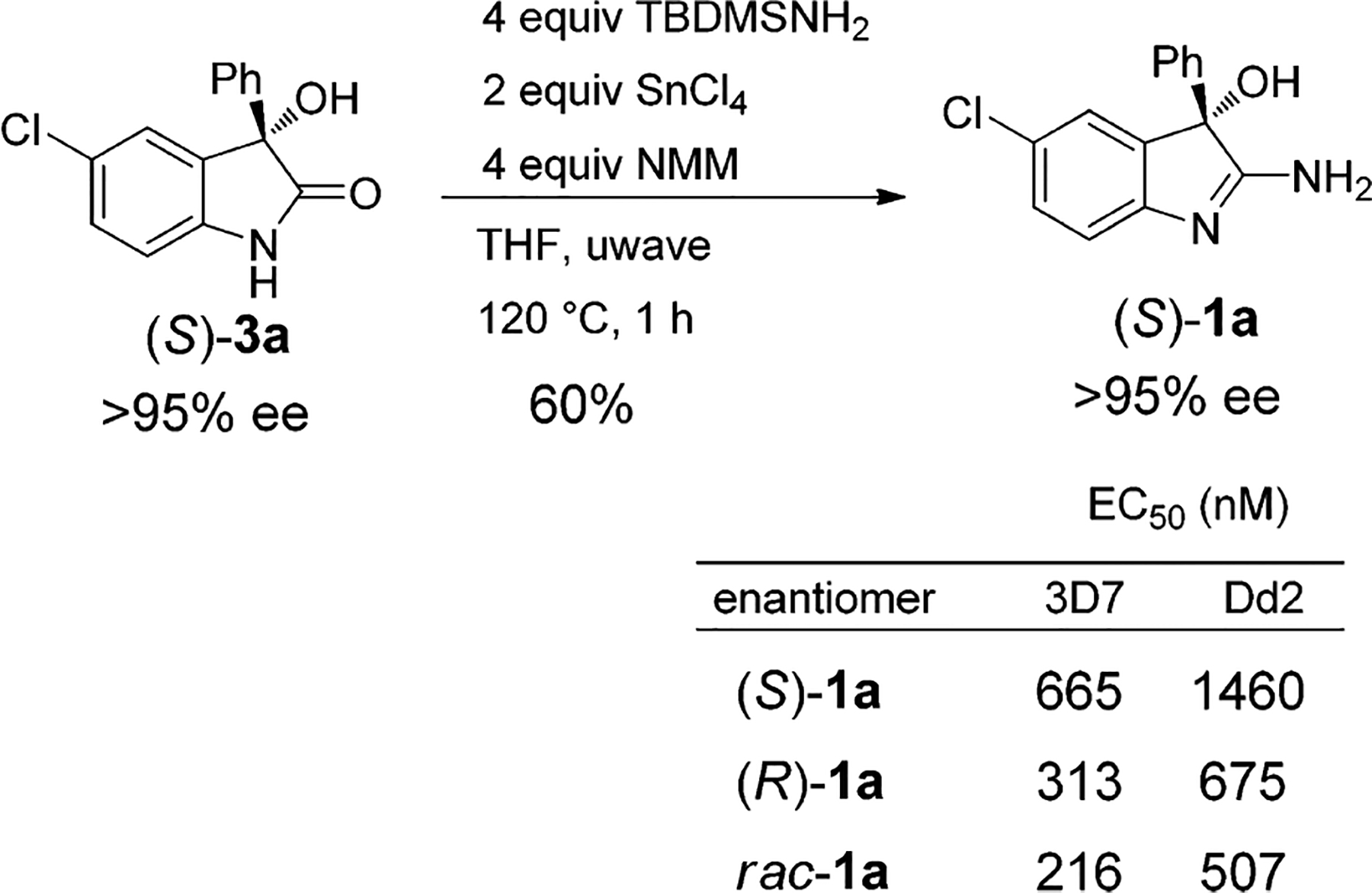

To ascertain whether an enantioenriched 3-hydroxyoxin-dole would transform into 2-amino-3-hydroxy-indole under the reaction conditions without any loss in enantiomeric excess, we prepared chiral 3-hydroxyoxindole (S)-3a22(>95% ee) and subjected it to SnCl4 promoted amidation reaction with TBDMSNH2. Gratifyingly, the corresponding 2-amino-3-hydroxy-indole (S)-1a was obtained in good yield without any measurable loss of enantiomeric excess (>95%ee) indicating no racemization occurred during the reaction (Scheme 4).

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of Enantioenriched 2-Amino-3-hydroxy-indole 1a

The initial exploratory SAR against drug-sensitive (3D7) and drug-resistant (Dd2) parasite strains indicates that 2-amino-3-hydroxy-indoles are in general more active when R2 is either an ortho-substituted electron-rich aromatic ring (entries c and m, Table 1) or a naphthyl moiety (entry n, Table 1), which is possibly a result of the increased dihedral angle of the biaryl system and thereby generating a more favorable binding conformation for its target(s). 2-Amino-3-hydroxy-indoles 1 with benzylic and alkyl groups at R2 also displayed potent antimalarial activity for R1 as 5-Cl. Furthermore, protection of the 3-hydroxyl (Scheme 3 compound 5; EC50 >5 μM) or 2-amino groups (Scheme 3 compound 4a; EC50 > 5 μM) was found to be detrimental. The 3-hydroxyl-oxindoles (3) which potentially can be regenerated by hydrolysis of the 2-amino group did not exhibit any significant antimalarial activity.

A 2-fold difference in in Vitro activity between the two enantiomers of 1a was noted and interestingly, racemate was found to be more active than either of the two enantiomers (Scheme 4).

In summary, we have identified 2-amino-3-hydroxy-indoles as a novel chemical class with potent in Vitro and in vivo antimalaria activity. We have developed a concise synthetic strategy to efficiently synthesize analogues in quantities sufficient for medicinal chemistry exploration. This method establishes the unprecedented use of TBDMSNH2 as an ammonia surrogate and allows for the first enantioselective synthesis of 2-amino-3-hydroxy-indoles. It is likely that TBDMSNH2 will find use in other transformations requiring protected ammonia equivalents.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment.

We are grateful to Roger Wiegand (Broad Institute), Ted Sybertz (Genzyme Corporation), Ian Bathurst (MMV), and all members of the Broad Institute-Genzyme-MMV Malaria Drug Development Initiative for thoughtful discussions; Stuart Schreiber (Broad Institute) and the Broad Chemical Biology Program for access to key instrumentation and reagents; Erin Tyndall and Justin Dick for assistance with the P falciparum viability assay; Chris Johnson, Galina Beletsky, Kachicholu Agu and Stephen Jonston (all Broad Institute) for analytical support; Miryam Garcia Rosa (UPR) for assistance with the animal efficacy studies; Peter Müller for generating the X-ray crystallography data and Li Li for acquisition of HRMS data (both MIT Chemistry Department). This work was supported by grants from Medicines for Malaria Venture (MMV) and The Broad Institute (SPARC).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Experimental procedures and characterization; 1H and 13C NMR, chiral SFC chromatogram, and X-ray structure of 1a. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- (1).Aregawi M Cibulskis R Otten M Williams R Dye C World Malaria Report 2008; World Health Organization: Geneva, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- (2).Ekland EH; Fidock DA Int. J. Parasitol 2008, 38, 743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Baniecki ML; Wirth DF; Clardy J Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2007, 51, 716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Gamo F-J; Sanz LM; Vidal J; Cozar C. d.; Alvarez E; Lavandera J-L; Vanderwall DE; Green DVS; Kumar V; Hasan S; Brown JR; Peishoff CE; Cardon LR; Garcia-Bustos JF Nature 2010, 465, 305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Guiguemde WA; Shelat AA; Bouck D; Duffy S; Crowther GJ; Davis PH; Smithson DC; Connelly M; Clark J; Zhu F; Jiménez-Díaz MB; Martinez MS; Wilson EB; Tripathi AK; Gut J; Sharlow ER; Bathurst I; El Mazouni F; Fowble JW; Forquer I; McGinley PL; Castro S; Angulo-Barturen I; Ferrer S; Rosenthal PJ; Derisi JL; Sullivan DJ; Lazo JS; Roos DS; Riscoe MK; Phillips MA; Rathod PK; Van Voorhis WC; M Avery V; Guy RK Nature 2010, 465, 311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Analysis of screening libraries and assay results was supported by Instant JChem, JKlustor, and Screen; ChemAxon: Budapest, Hungary; www.chemaxon.com/products.html. [Google Scholar]

- (7).Peters W Robinson BL In Parasitic Infection Modelsin; Zak O, Sande MA, Eds.; Academic Press: London, 1999; pp 757. [Google Scholar]

- (8).Wittig G; Kleiner H; Conrad J Liebigs Ann. Chem 1929, 469, 1. [Google Scholar]

- (9).Bell SC; Wei PHL J. Heterocycl. Chem 1969, 6, 599. [Google Scholar]

- (10).Ishizumi K; Inaba S; Yamamoto H J. Org. Chem 1974, 39, 2581. [Google Scholar]

- (11).Benincori T; Sannicolo F J. Org. Chem 1988, 53, 1309. [Google Scholar]

- (12).Toullec P; Jagt R; de Vries J; Feringa B; Minnaard A Org. Lett 2006, 8, 2715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Shintani R; Inoue M; Hayashi T Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2006, 45, 3353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Hanhan NV; Sahin AH; Chang TW; Fettinger JC; Franz AK Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2010, 49, 744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Meyer R; Zwiesler M J. Org. Chem 1968, 33, 4274. [Google Scholar]

- (16).Escoubet S; Gastaldi S; Bertrand M Eur. J. Org. Chem 2005, 2005, 3855. [Google Scholar]

- (17).Unsatisfactory yields were obtained when a RhCl3-catalyzed allyl deprotection strategy was applied. Zacuto M; Xu F J. Org. Chem 2007, 72, 6298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Huang X; Buchwald S Org. Lett 2001, 3, 3417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).West R; Boudjouk P J. Am. Chem. Soc 1973, 95, 3983. [Google Scholar]

- (20).Bowser J; Neilson R; Wells R Inorg. Chem 1978, 17, 1882. [Google Scholar]

- (21).Quallich G; Makowski T; Sanders A; Urban F; Vazquez E J. Org. Chem 1998, 63, 4116. [Google Scholar]

- (22).Hewawasam P; Erway M; Moon S; Knipe J; Weiner H; Boissard C; Post-Munson D; Gao Q; Huang S; Gribkoff V; Meanwell N J. Med. Chem 2002, 45, 1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.