Abstract

Background and Aims

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is a major risk factor for cardiometabolic disease in adults. The burden of liver fat and associated cardiometabolic risk factors in healthy children is unknown. In a population‐based prospective cohort study among 3,170 10‐year‐old children, we assessed whether both liver fat accumulation across the full range and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease are associated with cardiometabolic risk factors already in childhood.

Approach and Results

Liver fat fraction was measured by magnetic resonance imaging, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease was defined as liver fat fraction ≥5.0%. We measured body mass index, blood pressure, and insulin, glucose, lipids, and C‐reactive protein concentrations. Cardiometabolic clustering was defined as having three or more risk factors out of high visceral fat mass, high blood pressure, low high‐density‐lipoprotein cholesterol or high triglycerides, and high insulin concentrations. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease prevalences were 1.0%, 9.1%, and 25.0% among children who were normal weight, overweight, and obese, respectively. Both higher liver fat within the normal range (<5.0% liver fat) and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease were associated with higher blood pressure, insulin resistance, total cholesterol, triglycerides, and C‐reactive protein concentrations (P values < 0.05). As compared with children with <2.0% liver fat, children with ≥5.0% liver fat had the highest odds of cardiometabolic clustering (odds ratio 24.43 [95% confidence interval 12.25, 48.60]). The associations remained similar after adjustment for body mass index and tended to be stronger in children who were overweight and obese.

Conclusions

Higher liver fat is, across the full range and independently of body mass index, associated with an adverse cardiometabolic risk profile already in childhood. Future preventive strategies focused on improving cardiometabolic outcomes in later life may need to target liver fat development in childhood.

Abbreviations

- CI

confidence interval

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- NAFLD

nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- SD

standard deviation

- SDS

standard deviation score

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is a major risk factor for cardiometabolic disease, end‐stage liver disease, and subsequent need for liver transplantation.1, 2, 3, 4 In adults, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is associated with cardiovascular disease, dyslipidemia, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and metabolic syndrome.1, 3, 5, 6 Because of high rates of childhood overweight and obesity, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease has become the most common chronic liver disease in children in Western countries.3, 7 The estimated prevalence in children varies from 3% to 11%, depending on population characteristics and diagnostic methods.2, 8, 9 Studies on the cardiometabolic consequences of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in children are scarce. Studies in small population‐based samples among children who were older or only obese suggested that nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is associated with increased risks of insulin resistance, hypertension, and dyslipidemia.5, 7, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 It is not known whether liver fat also influences cardiometabolic risk factors in children without obesity or nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. The limited number of studies focused on liver fat in children is partly due to the difficulty in measuring liver fat. Liver biopsy is the gold standard for diagnosing nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, but is not possible to perform in population‐based samples.2, 6 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) enables noninvasive measurement of liver fat.15, 16

We performed a cross‐sectional analysis among 3,170 10‐year‐old children participating in a population‐based prospective cohort study to examine whether liver fat accumulation across the full range and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease assessed with MRI are associated with cardiometabolic risk factors.

Patients and Methods

Study Population

This study was embedded in the Generation R Study, a population‐based prospective cohort from early fetal life onward, based in Rotterdam, the Netherlands.17 The study has been approved by the Medical Ethical Committee of the Erasmus University Medical Center in Rotterdam (MEC 198.782/2001/31). Written informed consent was obtained from parents for all participants.17 All children were born between April 2002 and January 2006. In total, 4,245 children attended the MRI subgroup study at 10 years. None of these children had a history of jaundice, medication use, alcohol use, smoking, or drugs, based on information from questionnaires at 10 years. We included children with at least one cardiometabolic outcome available. The population for analysis of this subgroup study comprised 3,170 children (Supporting Fig. S1). Missing measurements were mainly due to no data on liver fat, MRI artifacts, or blood sampling.

Liver Fat at 10 Years

We measured liver fat using a 3.0 Tesla MRI (Discovery MR750w, GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI).15, 16, 17, 18 The children wore light clothing without metal objects while undergoing the body scan. A liver fat scan was performed using a single‐breath‐hold, 3D volume and a special 3‐point proton density weighted Dixon technique (IDEAL IQ) for generating a precise liver fat fraction image.19 The IDEAL IQ scan is based on a carefully tuned 6‐echo echo planar imaging acquisition. The obtained fat‐fraction maps were analyzed by Precision Image Analysis (PIA, Kirkland, WA) using the sliceOmatic (TomoVision, Magog, Canada) software package. All extraneous structures and any image artifacts were removed manually.20 Liver fat fraction was determined by taking 4 samples of at least 4 cm2 from the central portion of the hepatic volume. Subsequently, the mean signal intensities were averaged to generate an overall mean liver fat estimation. Liver fat measured with IDEAL IQ using MRI is reproducible, highly precise, and validated in adults.21, 22 As described, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease was defined as liver fat ≥5.0%.7, 18, 22 To study the associations across the full spectrum, liver fat was first categorized into six categories (0.0%‐0.9%, 1.0%‐1.9%, 2.0%‐2.9%, 3.0%‐3.9%, 4.0%‐4.9%, and >5.0%). Because only 5 children were in the 0.0%‐0.9% group, we combined them with the 1.0%‐1.9% group. In total 5 categories were used: <2.0% (n = 1,590), 2.0%‐2.9% (n = 1,160), 3.0%‐3.9% (n = 250), 4.0%‐4.9% (n = 80), and ≥5.0% (n = 90). The reference group was <2.0% because it is the largest group and contains the median of the sample. Because of lower numbers, no further subcategories were possible for >5.0% liver fat.

Cardiometabolic Risk Factors at 10 Years

We measured blood pressure at the right brachial artery four times with 1‐minute intervals using the validated automatic sphygmomanometer Datascope Accutor Plus (Paramus, NJ).23 We calculated the mean value for systolic and diastolic blood pressure using the last three blood pressure measurements of each participant. Thirty‐minute fasting venous blood samples were collected to measure glucose, insulin, total cholesterol, high‐density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, triglycerides and C‐reactive protein concentrations.17 We consider the 30‐minute fasting samples as nonfasting samples. This time interval was chosen because of the design of our study, in which it was not possible to obtain fasting samples from all children. Glucose, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, C‐reactive protein, and triglycerides concentrations were measured using the c702 module on the Cobas 8000 analyzer. Insulin was measured with electrochemiluminescence immunoassay on the E411 module (Roche, Almere, the Netherlands). Concentrations of low‐density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol were calculated according to the Friedewald formula.24 Insulin resistance was estimated with the homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA‐IR) using the following formula: insulin resistance = (insulin [μU/L] × glucose [mmol/L])/22.5.25 Visceral fat mass was obtained by MRI scans, as described.17, 26 We defined children with clustering of cardiometabolic risk factors being at risk for metabolic syndrome phenotype, in line with other studies.27, 28 Clustering of cardiometabolic risk factors was defined as having three or more out of the following four adverse risk factors: visceral fat mass above the seventy‐fifth percentile; systolic or diastolic blood pressure above the seventy‐fifth percentile percentile; HDL cholesterol below the twenty‐fifth percentile or triglycerides above the seventy‐fifth percentile; and insulin above the seventy‐fifth percentile of our study population.

Covariates

At enrollment in the study, we obtained maternal education level and prepregnancy weight by questionnaires, measured maternal height, and calculated prepregnancy body mass index (BMI). Information on child age and sex was obtained from medical records and on ethnicity from questionnaires. We measured childhood height and weight, both without shoes and heavy clothing, calculated BMI at 10 years, and further calculated sex‐adjusted and age‐adjusted childhood BMI standard deviation scores (SDS; Growth Analyzer 4.0, Dutch Growth Research Foundation).29 Childhood BMI was categorized into underweight, normal weight, overweight, and obesity using the International Obesity Task Force cutoffs.30

Statistical Analysis

First, we examined differences in subject characteristics between childhood BMI groups with analysis of variance tests for continuous variables and Chi‐square tests for categorical variables. We used similar methods to assess the differences for cardiometabolic risk factors between children with and without nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in children who were normal weight, overweight, and obese. For nonresponse analyses, we compared participants and nonparticipants with Student t tests, Mann‐Whitney tests, and Chi‐square tests.

Second, we used linear regression models to assess the associations of liver fat across the full range and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, both compared with the reference group, with cardiometabolic risk factors at 10 years. Analyses were performed for the total group and also separately for children who were normal weight and overweight or obese, to whom we further refer as children who are overweight.

Third, we used logistic regression models to assess the associations of liver fat in categories with the odds of adverse levels of single and clustered cardiometabolic risk factors at 10 years. Only cases with complete data on cardiometabolic outcomes were used for the analyses with clustered cardiometabolic risk factors. For all analyses, we presented a basic model adjusted for child age, sex, and ethnicity and a confounder model, which was additionally adjusted for maternal prepregnancy BMI and education. Because we were interested in the associations of liver fat with cardiometabolic risk factors independently of BMI, we analyzed an extra model, which was additionally adjusted for child BMI at 10 years (BMI model), to observe the additional confounding effect of BMI in our associations. Covariates were included in the models based on other studies, strong correlations with liver fat, risk of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and with cardiometabolic risk factors, and if they changed the effect estimates >10%.2, 8 Because insulin, HOMA‐IR, triglycerides, and C‐reactive protein concentrations were skewed, we used their natural logged values in all linear regression analyses. Because of a violation of the normality of the residuals assumption in the linear regression models, which was caused by a skewed distribution of liver fat, we also log‐transformed liver fat when used continuously. To enable comparison of effect sizes of different measures, we constructed SDS ([observed value – mean]/SD) for all variables. We found a statistically significant interaction between liver fat and BMI for systolic blood pressure, HOMA‐IR, triglycerides and C‐reactive protein. No statistical interactions between liver fat and sex or between liver fat and ethnicity were observed in the associations with cardiometabolic risk factors. As sensitivity analyses, we repeated the analyses with adjustment for visceral fat mass instead of BMI to explore whether any association was affected by visceral fat. Missing data of covariates were multiple‐input using a Markov chain Monte Carlo approach. Five imput data sets were created and analyzed together. All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package of Social Sciences (SPSS) version 25.0 for Windows (IBM, Chicago, IL).

Results

Subject Characteristics

The median liver fat fraction was 1.8% (95% range: 1.1‐3.1), 2.0% (95% range: 1.2‐4.1), 2.5% (95% range: (1.4‐8.7), and 3.1% (95% range: 1.7‐17.9) in children who were underweight, normal weight, overweight, and obese, respectively (Table 1). Prevalences of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease were 2.8% (n = 90) in the total group and 1.0% (n = 26), 9.1% (n = 41), and 25.0% (n = 23) in children who were normal weight, overweight, and obese, respectively. We observed in all BMI groups higher levels of adverse cardiometabolic risk factors in children with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, compared with those without nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (Table 2). Nonresponse analyses showed that participants were slightly more often European and had lower BMI compared with nonparticipants (Supporting Table S1).

Table 1.

Subject Characteristics

| Total (n = 3,170) | Underweight (n = 212) | Normal Weight (n = 2,410) | Overweight (n = 456) | Obesity (n = 92) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal characteristics | ||||||

| Age, mean (SD), years | 31.1 (4.9) | 31.3 (4.7) | 31.4 (4.7) | 30.0 (5.2) | 29.0 (5.9) | <0.001 |

| Prepregnancy BMI, mean (SD), kg/m2 | 23.5 (4.2) | 21.8 (3.2) | 23.1 (3.8) | 25.4 (4.6) | 28.8 (6.1) | <0.001 |

| Parity, n (%), nulliparous | 1,769 (55.8) | 132 (62.3) | 1,325 (55.0) | 257 (56.4) | 55 (59.8) | 0.179 |

| Education, n (%), higher education | 1,540 (52.7) | 109 (54.5) | 1,273 (57.2) | 150 (36.1) | 8 (10.0) | <0.001 |

| Child characteristics | ||||||

| Age, mean (SD), years | 9.8 (0.3) | 9.8 (0.4) | 9.8 (0.3) | 9.9 (0.4) | 9.8 (0.3) | 0.033 |

| Boys, n (%) | 1,563 (49.3) | 112 (52.8) | 1,221 (50.7) | 191 (41.9) | 39 (42.4) | 0.002 |

| Ethnicity, n (%), European | 2,118 (68.2) | 150 (72.1) | 1,706 (72.2) | 229 (51.3) | 33 (37.5) | <0.001 |

| Birth weight, mean (SD), g | 3,445 (557) | 3,264 (575) | 3,458 (549) | 3,483 (553) | 3,376 (679) | <0.001 |

| BMI, mean (SD), kg/m2 | 17.5 (2.7) | 14.1 (0.5) | 16.8 (1.3) | 21.3 (1.2) | 23.5 (2.1) | <0.001 |

| Visceral fat mass, median (95% range), g | 358 (161; 982) | 245 (135; 478) | 338 (162; 709) | 602 (268; 1,216) | 853 (362; 1,862) | <0.001 |

| Liver fat fraction, median (95% range), % | 2.0 (1.2; 5.3) | 1.8 (1.1; 3.1) | 2.0 (1.2; 4.1) | 2.5 (1.4; 8.7) | 3.1 (1.7; 17.9) | <0.001 |

| Prevalence nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, n (%) | 90 (2.8) | 1 (0.5) | 26 (1.0) | 41 (9.1) | 23 (25.0) | <0.001 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mean (SD), mm Hg | 103.3 (8.0) | 99.3 (7.6) | 102.4 (7.5) | 107.3 (7.8) | 113.0 (8.8) | <0.001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mean (SD), mm Hg | 58.6 (6.4) | 57.6 (6.3) | 58.4 (6.4) | 59.5 (6.5) | 61.8 (7.6) | <0.001 |

| Insulin, median (95% range), pmol/L | 182 (35.2; 629.1) | 144 (27.9; 471.8) | 172 (34.5; 569.2) | 242 (48.0; 798.2) | 339 (45.2; 1,178.0) | <0.001 |

| Glucose, mean (SD), mmol/L | 5.3 (0.9) | 5.3 (1.0) | 5.3 (1.0) | 5.2 (0.8) | 5.3 (0.7) | 0.114 |

| HOMA‐IR, median (95% range) | 7.0 (1.1; 28.8) | 5.7 (0.9; 22.8) | 6.6 (1.1; 26.9) | 9.3 (1.6; 32.1) | 12.4 (1.5; 50.5) | <0.001 |

| Total cholesterol, mean (SD), mmol/L | 4.3 (0.7) | 4.3 (0.6) | 4.3 (0.6) | 4.4 (0.7) | 4.5 (0.7) | <0.001 |

| HDL cholesterol, mean (SD), mmol/L | 1.5 (0.3) | 1.6 (0.4) | 1.5 (0.3) | 1.4 (0.3) | 1.2 (0.2) | <0.001 |

| LDL cholesterol, mean (SD), mmol/L | 2.3 (0.6) | 2.3 (0.5) | 2.3 (0.6) | 2.5 (0.6) | 2.6 (0.7) | <0.001 |

| Triglycerides, median (95% range), mmol/L | 1.0 (0.4; 2.6) | 0.87 (0.4; 2.2) | 0.9 (0.4; 2.5) | 1.1 (0.5; 2.9) | 1.5 (0.5; 3.8) | <0.001 |

| C‐reactive protein, median (95% range), mg/L | 0.3 (0.3; 5.7) | 0.3 (0.3; 6.1) | 0.3 (0.3; 4.4) | 0.9 (0.3; 10.2) | 1.5 (0.3; 14.2) | <0.001 |

| Prevalence cardiometabolic clustering, n (%) | 254 (13.3) | 2 (1.8) | 106 (7.2) | 114 (42.1) | 32 (72.7) | <0.001 |

Values are observed, but not imput data and represent means (SD), medians (95% range) or numbers of subjects (valid %). Differences between BMI categories were tested using one‐way ANOVA tests for continuous variables and χ2 test for categorical variables. HOMA‐IR was calculated using the formula: insulin resistance = (insulin [μU/L] × glucose [mmol/L])/22.5. LDL cholesterol is calculated according to the Friedewald formula. Cardiometabolic clustering was defined as having three or more risk factors (high [greater than seventy‐fifth percentile] visceral fat mass, high [greater than seventy‐fifth percentile] systolic or diastolic blood pressure, low [less than twenty‐fifth percentile] HDL cholesterol or high [greater than seventy‐fifth percentile] triglycerides, and high [greater than seventy‐fifth percentile] insulin). The prevalence of cardiometabolic clustering was calculated in a subgroup of complete cases (n = 1,906).

Table 2.

Children With and Without Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Among Different BMI Groups with Cardiometabolic Risk Factors

| Systolic Blood Pressure (mm Hg) Mean (SD) | Diastolic Blood Pressure (mm Hg) Mean (SD) | HOMA‐IR Median (95% Range) | Total – Cholesterol (mmol/L) Mean (SD) | Triglycerides (mmol/L) Median (95% range) | C‐Reactive Protein (mg/L) Median (95% Range) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal weight | ||||||

| Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, n (%) | ||||||

| No; 2,384 (99.0) | 102.4 (7.5) | 58.4 (6.4) | 6.6 (1.8;19.6) | 4.3 (0.6) | 0.9 (0.4;2.5) | 0.3 (0.3;4.3) |

| Yes; 26 (1.0) | 104.7 (7.9) | 61.7 (5.9) | 6.5 (1.5;21.4) | 4.4 (0.8) | 1.39 (0.3;3.5) | 0.3 (0.3;34.0) |

| Overweight | ||||||

| Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, n (%) | ||||||

| No; 415 (90.9) | 107.1 (7.6) | 59.3 (6.4) | 8.8 (2.5;23.3) | 4.4 (0.7) | 1.1 (0.5;2.9) | 0.7 (0.3;8.7) |

| Yes; 41(9.1) | 109.2 (9.8) | 60.9 (7.0) | 10.6 (2.5;37.6) | 4.9 (0.8) | 1.4 (0.5;3.0) | 1.8 (0.3;18.1) |

| Obese | ||||||

| Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, n (%) | ||||||

| No; 69(75.0) | 112.6 (8.7) | 61.4 (7.8) | 13.7 (2.3;45.5) | 4.6 (0.7) | 1.4 (0.4;3.8) | 1.4 (0.3;9.6) |

| Yes; 23(25.0) | 114.0 (9.2) | 62.7 (6.9) | 11.4 (4.5;40.7) | 4.3 (0.7) | 1.6 (0.6;3.0) | 1.9 (0.3;18.0) |

Values are observed, but not imput data and represent means (SD), medians (95% range), or numbers of subjects (valid %).

Liver Fat and Cardiometabolic Risk Factors

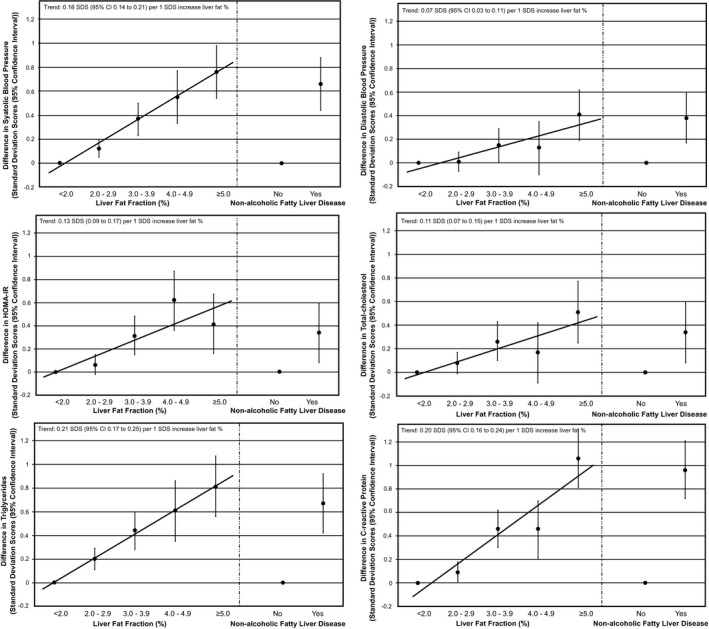

Higher liver fat and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease were associated with higher systolic and diastolic blood pressure, HOMA‐IR, and total cholesterol, triglycerides, and C‐reactive protein concentrations (P values < 0.05; Fig. 1). As compared with the reference group of children with <2.0% of liver fat, children with ≥5.0% of liver fat tended to have the strongest associations with the cardiometabolic risk factors (differences for systolic blood pressure (0.76 [95% confidence interval {CI} 0.55‐0.97] SDS), diastolic blood pressure (0.41 [95% CI 0.19‐0.62] SDS), HOMA‐IR (0.41 (95% CI 0.16‐0.67) SDS, total cholesterol (0.51 [95% CI 1.24‐3.67] SDS), triglycerides (0.81 [95% CI 0.56‐1.07] SDS), and C‐reactive protein (1.06 [95% CI 0.81‐1.31] SDS). Supporting Fig. S2 shows similar results for the basic models. These associations of liver fat and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease with cardiometabolic risk factors were also present after additional adjustment for childhood BMI (Supporting Fig. S3). Liver fat and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease were positively associated with insulin and LDL cholesterol and negatively associated with HDL cholesterol and no associations were observed with glucose (Supporting Table S2). Stratified analyses showed that the associations of liver fat and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease with cardiometabolic outcomes were present among both children who were normal weight and those who were overweight, with a tendency for stronger effect estimates among children who were overweight (Supporting Table S3). The sensitivity analyses using visceral fat instead of BMI showed no consistent differences in associations of liver fat and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease with cardiometabolic risk factors (Supporting Table S4).

Figure 1.

Associations of liver fat fraction and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease with cardiometabolic risk factors at school age. Values are regression coefficients (95% CI) from linear regression models that reflect differences in childhood cardiometabolic risk factors in SDS per SDS change in childhood liver fat fraction as compared with the reference group (children with <2.0% of liver fat; left side of each graph) or for children with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease as compared with the reference group (children with <5.0% of liver fat; right side of each graph). Associations are adjusted for child’s age, sex, ethnicity, maternal prepregnancy BMI, and maternal education. Trend lines are given only when P value for linear trend <0.05.

Liver Fat and Clustering of Cardiometabolic Risk Factors

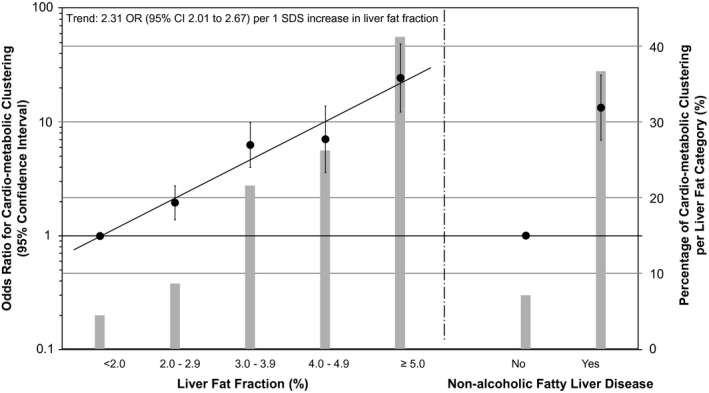

In children with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, the prevalence of cardiometabolic clustering was 66.7% (n = 30) compared with a prevalence of 12.0% (n = 224) in children without nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Supporting Figs. S4 and S5 show liver fat continuously with cardiometabolic clustering present and not present, respectively. Higher liver fat was associated with higher odds of cardiometabolic clustering, already from a liver fat fraction of ≥2.0% onward (P values < 0.05; Fig. 2). As compared with the reference group of children with <2.0% of liver fat, children with ≥5.0% of liver fat had the highest odds of cardiometabolic clustering (odds ratio [OR] 24.43 [95% CI 12.25‐48.60]). The strongest association for liver fat was observed with high visceral fat mass, with an OR 27.80 (95% CI 14.50‐53.30; Supporting Fig. S7). Supporting Fig. S6 shows similar results for the basic models and the associations were not materially affected after further adjustment for childhood BMI (Supporting Fig. S8). Because of the moderate correlation between liver fat and visceral fat, we also performed the analyses for the cardiometabolic clustering excluding visceral fat; these showed slightly smaller but still statistically significant odds ratios (Supporting Table S5).

Figure 2.

Associations of liver fat fraction and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease with odds of clustering of cardiometabolic risk factors at school age. Values are ORs (95% CI) analyzed in a subgroup of cases with complete data for all cardiometabolic variables (n = 1,906) that reflect the risk of cardiometabolic clustering per increase in liver fat fraction as compared with the reference group (<2.0%; left side of the figure) or for children with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease as compared with the reference group (children with <5.0% of liver fat; right side of the figure). Bars represent the percentage of cardiometabolic clustering per liver fat fraction group. Cardiometabolic clustering was defined as having three or more risk factors (high [greater than seventy‐fifth percentile] visceral fat mass, high [greater than seventy‐fifth percentile] systolic or diastolic blood pressure, low [less than twenty‐fifth percentile] HDL cholesterol or high [greater than seventy‐fifth percentile] triglycerides, and high [greater than seventy‐fifth percentile] insulin. Associations are adjusted for child age, sex, ethnicity, maternal prepregnancy BMI, and maternal education. Trend lines are given only when P value for linear trend <0.05.

Discussion

We observed that not only nonalcoholic fatty liver disease but also a higher liver fat across the full range is associated with an adverse cardiometabolic profile in school‐age children. Adverse cardiometabolic clustering was already observed from a liver fat fraction of ≥2.0% onward. The associations were independent of BMI and tended to be stronger in children who were overweight and obese than in children who were normal weight.

Interpretation of main findings

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease has a prevalence of up to 30% in the general adult population.6, 31 Because of the high rates of childhood overweight and obesity, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease has also become the most common chronic liver disease in children in the developed world.3, 18 Studies in selected populations estimated childhood prevalences of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease between 3% and 11%. The differences in prevalences were mainly due to heterogeneity in sample selection and diagnostic methods.2, 8, 9 In a population‐based sample, using a sensitive imaging‐based method for liver fat assessment, we observed a prevalence of 2.8% for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in all children, with the highest prevalence up to 25.0% among children who were obese. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease was not only present among children who were obese but also among children who were normal weight. This high prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in 10‐year‐old children is an important population health problem.

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is strongly associated with cardiovascular disease, dyslipidemia, and type 2 diabetes mellitus in adults.1, 3, 5, 18 A cross‐sectional study in 571 children who were obese aged 8‐18 years showed that, as compared with children without nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, those with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease had higher BMI, insulin resistance, and triglycerides concentrations.5 Three case‐control studies reported that children with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease had a more adverse cardiometabolic profile.11, 12, 14 In line with these previous studies, we observed that nonalcoholic fatty liver disease was associated with higher blood pressure, insulin resistance, adverse lipids profile, and increased C‐reactive protein concentrations at 10 years.

To the best of our knowledge, no previous studies have assessed the associations of liver fat accumulation across the full range. The cutoff point for defining nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in children and adults is originally derived from adult studies.22 We observed that children with liver fat of ≥5.0% had the highest odds of cardiometabolic risk factor clustering. However, we also observed that even small increases in liver fat from ≥2.0% onward were associated with adverse cardiometabolic risk factors. Our results suggest that in children, the cutoff for increased risk of an adverse cardiometabolic risk profile is already between 2.0% and 3.0% liver fat, instead of the current cutoff of ≥5%. We could not test a lower cutoff because in our study group, only 5 children had liver fat <1.0%. These findings suggest that diagnosing nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in children might need a lower threshold than 5.0% liver fat. Current conventional ultrasounds cannot measure this low liver fat percentage, but future improvements in resolution of ultrasound techniques may enable detection of lower fat percentages. We also observed that the associations of liver fat with cardiometabolic risk factors in childhood were independent of BMI and present among both children who were normal weight and overweight, with stronger effect estimates among children who were overweight. The combination of higher liver fat and higher BMI might exacerbate the adverse cardiometabolic health profile. Next to BMI, visceral fat is also known to correlate with liver fat.26 However, our results suggest that the associations of liver fat with cardiometabolic risk factors were independent of visceral fat. Thus, not only nonalcoholic fatty liver disease but also small increases in liver fat accumulation within the normal range are, independent of BMI and visceral fat, related to an adverse cardiometabolic risk profile already in childhood.

The directions of the associations of liver fat with cardiometabolic risk factors cannot be concluded from a cross‐sectional analysis. Future prospective follow‐up studies should explore prospectively whether liver fat in childhood leads to increased risks of cardiovascular disease. In our study, we will perform follow‐up studies in cardiovascular risk factors at age 18 years. Several mechanisms have been described linking liver fat with cardiometabolic risk factors.4 Increased visceral fat mass may alter lipid metabolism and trigger insulin resistance that may subsequently lead to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and cardiovascular disease.4, 32, 33 On the other hand, liver fat can be the source of systemic release of inflammatory cytokines and proatherogenic factors leading to cardiometabolic diseases, including hypertension.3, 4, 26, 33 Findings from other studies suggest a strong association of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease with the metabolic syndrome.4, 33 Also, studies in both adults and children showed associations of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease with hypertension as part of the metabolic syndrome.34, 35, 36 Adults with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease had increased carotid artery intima‐media thickness and increased prevalence of carotid atherosclerotic plaques.35 Possible underlying mechanisms may include chronic inflammation leading to proatherogenic factors leading to arterial damage and hypertension.33 The strong associations of higher liver fat with both systolic blood pressure and C‐reactive protein in our study support this hypothesis. Prospective analyses or mendelian randomization approaches may help to elucidate the directions of the observed associations. Our study suggests that increased levels of liver fat are common and associated with harmful cardiometabolic consequences in childhood, predisposing children to cardiovascular disease later in life. Future studies should focus on specific lifestyle‐related factors influencing liver fat from early childhood onward.

Methodological Considerations

Major strengths of this study are the cross‐sectional analysis performed in an ongoing prospective cohort study with a large sample size, with information on liver fat fraction measured with MRI and on cardiometabolic outcomes in children at a young age.

The nonresponse at MRI visit would lead to biased effect estimates if associations were different between those included and not included in the analyses, but this seems unlikely. We had a relatively small number of children with obesity, which indicates a selection toward a lean population that might affect the generalizability of our findings. The healthy and young study population possibly also explains the small number of children with liver fat fraction above the clinical cutoff of 5.0%. This might have limited our statistical power to detect significant associations. However, little data are available on liver fat in healthy children and its relation to cardiometabolic risk factors. The fasting time before blood sampling was limited to 30 minutes, and thus we consider our samples nonfasting samples.17 The blood samples were collected at different time points during the day, depending on the time of the study visit. Because glucose and insulin levels shift very easily during the day and are sensitive toward carbohydrate intake, this may have led to nondifferential misclassification of children with high or low glucose and insulin levels and thus underestimation of the observed effect estimates. On the other hand, for lipid levels, it has been shown that nonfasting blood sampling is superior to fasting in accurately predicting cardiometabolic events for adults in later life.37 Therefore, we believe our findings for triglycerides and cholesterol are less likely influenced by the nonfasting state. Overall, these results need to be carefully interpreted, and further studies are needed to replicate our findings with fasting blood samples in children. Because we had a young study population, our results are not likely biased by alcohol use, known history of jaundice, hepatitis, smoking, drugs, or medication use. We had no data available on Tanner stages. The pubertal increase of sex hormones may be important in predisposition for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.38 In our population, we did not observe sex differences, possibly because of the young age. Although many covariates were included, there still might be some residual confounding, as in any observational study.

Liver fat across the full range is associated with an adverse cardiometabolic risk profile already in children of school age. The associations were independent of BMI and tended to be stronger in children who were overweight and obese. Future preventive strategies focused on improving cardiometabolic outcomes in later life may need to target liver fat metabolism already in young childhood.

Author Contributions

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows: M.L.G. and V.W.V.J. conceived of the study; M.L.G., S.S., and V.W.V.J. participated in the collection and statistical analysis of the data; M.L.G., S.S., J.F.F., L.D., M.W.V., and V.W.V.J. participated in the interpretation of the results; M.L.G., S.S., and V.W.V.J. drafted the manuscript; J.F.F., L.D., M.W.V., and R.G. critically reviewed the manuscript; and all authors read and approved the final manuscript. M.L.G., S.S., and V.W.V.J. are the guarantors of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Supporting information

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the contribution of general practitioners, hospitals, midwives, and pharmacies in Rotterdam.

Funding: The general design of the Generation R Study is made possible by financial support from the Erasmus MC, University Medical Center, Rotterdam, Erasmus University Rotterdam, Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMw), Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO), Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport, and Ministry of Youth and Families. R. G. received funding from the Dutch Heart Foundation (Grant Number 2017T013), the Dutch Diabetes Foundation (Grant Number 2017.81.002) and ZonMw (Grant Number 543003109). V. J. received grants from the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (VIDI 016.136.361) and the European Research Council (Consolidator Grant, ERC‐2014‐CoG‐648916).

Potential conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Author names in bold designate shared co‐first authorship.

- 1. Neuschwander‐Tetri BA. Non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease. BMC Med 2017;15:45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Anderson EL, Howe LD, Jones HE, Higgins JP, Lawlor DA, Fraser A. The prevalence of non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. PLoS One 2015;10:e0140908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Perry RJ, Samuel VT, Petersen KF, Shulman GI. The role of hepatic lipids in hepatic insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Nature 2014;510:84‐91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Targher G, Day CP, Bonora E. Risk of cardiovascular disease in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. N Engl J Med 2010;363:1341‐1350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bedogni G, Gastaldelli A, Manco M, De Col A, Agosti F, Tiribelli C, et al. Relationship between fatty liver and glucose metabolism: a cross‐sectional study in 571 obese children. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2012;22:120‐126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Diehl AM, Day C. Cause, pathogenesis, and treatment of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. N Engl J Med 2017;377:2063‐2072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Newton KP, Hou J, Crimmins NA, Lavine JE, Barlow SE, Xanthakos SA, et al. Prevalence of prediabetes and type 2 diabetes in children with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. JAMA Pediatr 2016;170:e161971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wiegand S, Keller KM, Röbl M, l'Allemand D, Reinehr T, Widhalm K, et al. Obese boys at increased risk for nonalcoholic liver disease: evaluation of 16 390 overweight or obese children and adolescents. Int J Obes 2010;34:1468‐1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Schwimmer JB, Deutsch R, Kahen T, Lavine JE, Stanley C, Behling C. Prevalence of fatty liver in children and adolescents. Pediatrics 2006;118:1388‐1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Burgert TS, Taksali SE, Dziura J, Goodman TR, Yeckel CW, Papademetris X, et al. Alanine aminotransferase levels and fatty liver in childhood obesity: associations with insulin resistance, adiponectin, and visceral fat. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006;91:4287‐4294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tominaga K, Fujimoto E, Suzuki K, Hayashi M, Ichikawa M, Inaba Y. Prevalence of non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease in children and relationship to metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance, and waist circumference. Environ Health Prev Med 2009;14:142‐149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Schwimmer JB, Pardee PE, Lavine JE, Blumkin AK, Cook S. Cardiovascular risk factors and the metabolic syndrome in pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Circulation 2008;118:277‐283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sartorio A, Del Col A, Agosti F, Mazzilli G, Bellentani S, Tiribelli C, et al. Predictors of non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease in obese children. Eur J Clin Nutr 2007;61:877‐883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fonvig CE, Chabanova E, Andersson EA, Ohrt JD, Pedersen O, Hansen T, et al. 1H‐MRS measured ectopic fat in liver and muscle in Danish lean and obese children and adolescents. PLoS ONE 2015;10:e0135018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bohte AE, van Werven JR, Bipat S, Stoker J. The diagnostic accuracy of US, CT, MRI and 1H‐MRS for the evaluation of hepatic steatosis compared with liver biopsy: a meta‐analysis. Eur Radiol 2011;21:87‐97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schwimmer JB, Middleton MS, Behling C, Newton KP, Awai HI, Paiz MN, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging and liver histology as biomarkers of hepatic steatosis in children with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2015;61:1887‐1895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kooijman MN, Kruithof CJ, van Duijn CM, Duijts L, Franco OH, van IJzendoorn MH, et al. The Generation R Study: design and cohort update 2017. Eur J Epidemiol 2016;31:1243‐1264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Vos MB, Abrams SH, Barlow SE, Caprio S, Daniels SR, Kohli R, et al. NASPGHAN clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in children: recommendations from the expert committee on NAFLD (ECON) and the North American society of pediatric gastroenterology, hepatology and nutrition (NASPGHAN). J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2017;64:319‐334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Reeder SB, Cruite I, Hamilton G, Sirlin CB . Quantitative assessment of liver fat with magnetic resonance imaging and spectroscopy. J Magn Reson Imaging 2011;34:729‐749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hu HH, Nayak KS, Goran MI. Assessment of abdominal adipose tissue and organ fat content by magnetic resonance imaging. Obes Rev 2011;12:e504‐e515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Awai HI, Newton KP, Sirlin CB, Behling C, Schwimmer JB. Evidence and recommendations for imaging liver fat in children, based on systematic review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;12:765‐773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Petaja EM, Yki‐Jarvinen H. Definitions of normal liver fat and the association of insulin sensitivity with acquired and genetic NAFLD‐A systematic review. Int J Mol Sci 2016;17:633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wong SN, Tz Sung RY, Leung LC. Validation of three oscillometric blood pressure devices against auscultatory mercury sphygmomanometer in children. Blood Press Monit 2006;11:281‐291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Onyenekwu CP, Hoffmann M, Smit F, Matsha TE, Erasmus RT. Comparison of LDL‐cholesterol estimate using the Friedewald formula and the newly proposed de Cordova formula with a directly measured LDL‐cholesterol in a healthy South African population. Ann Clin Biochem 2014;51:672‐679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wallace TM, Levy JC, Matthews DR. Use and abuse of HOMA modeling. Diabetes Care 2004;27:1487‐1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Monnereau C, Santos S, van der Lugt A, Jaddoe VWV, Felix JF. Associations of adult genetic risk scores for adiposity with childhood abdominal, liver and pericardial fat assessed by magnetic resonance imaging. Int J Obes (Lond) 2018;42:897‐904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jaddoe VW, de Jonge LL, Hofman A, Franco OH, Steegers EA, Gaillard R. First trimester fetal growth restriction and cardiovascular risk factors in school age children: population based cohort study. BMJ 2014;348:g14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Steinberger J, Daniels SR, Eckel RH, Hayman L, Lustig RH, McCrindle B, et al. Progress and challenges in metabolic syndrome in children and adolescents: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Atherosclerosis, Hypertension, and Obesity in the Young Committee of the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; and Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism. Circulation 2009;119:628‐647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fredriks AM, van Buuren S, Wit JM, Verloove‐Vanhorick SP. Body index measurements in 1996‐7 compared with 1980. Arch Dis Child 2000;82:107‐112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cole TJ, Bellizzi MC, Flegal KM, Dietz WH. Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: international survey. BMJ 2000;320:1240‐1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Byrne CD, Patel J, Scorletti E, Targher G. Tests for diagnosing and monitoring non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease in adults. BMJ 2018;362:k2734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cantero I, Abete I, Monreal JI, Martinez JA, Zulet MA . Fruit fiber consumption specifically improves liver health status in obese subjects under energy restriction. Nutrients 2017;9:667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rinella ME. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review. JAMA 2015;313:2263‐2273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ballestri S, Zona S, Targher G, Romagnoli D, Baldelli E, Nascimbeni F, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is associated with an almost twofold increased risk of incident type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome. Evidence from a systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;31:936‐944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sookoian S, Pirola CJ. Non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease is strongly associated with carotid atherosclerosis: a systematic review. J Hepatol 2008;49:600‐607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Schwimmer JB, Behling C, Newbury R, Deutsch R, Nievergelt C, Schork NJ, et al. Histopathology of pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2005;42:641‐649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Langsted A, Nordestgaard BG. Nonfasting versus fasting lipid profile for cardiovascular risk prediction. Pathology 2019;51:131‐141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Roberts EA. Pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): a "growing" problem? J Hepatol 2007;46:1133‐1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials