Abstract

Intestinal barrier dysfunction and dysbiosis contribute to development of diseases in liver and other organs. Physical, immunological, and microbiologic (bacterial, fungal, archaeal, viral, and protozoal) features of the intestine separate its nearly one hundred trillion microbes from the rest of the human body. Failure of any aspect of this barrier can result in translocation of microbes into the blood and sustained inflammatory response that promote liver injury, fibrosis, cirrhosis, and oncogenic transformation. Alterations in intestinal microbial populations or their functions can also affect health. We review the mechanisms that regulate intestinal permeability and how changes in the intestinal microbiome contribute to development of acute and chronic liver diseases. We discuss individual components of the intestinal barrier and how these are disrupted during development of different liver diseases. Learning more about these processes will increase our understanding of the interactions among the liver, intestine, and its flora.

Keywords: liver disease, hepatic disorders, gut permeability, microbiome, leaky gut, alcoholic liver disease (ALD), non-alcoholic liver disease (NAFLD), drug induced liver injury (DILI), primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC)

Changes in intestinal permeability and the intestinal microbiome have been associated with many diseases1–5. Intestinal physiology can vary, even among genetically identical animals6. Due to the close anatomical and physiologic connections between the intestine and the liver, there have been many studies of how changes in one affect the other.

The intestinal tract is colonized by nearly one-hundred trillion bacteria, more than 90% of which belong to the phyla Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes). In fact, the human body contains as many bacterial cells as human cells5, 7. The complex network of microbes that reside in animals regulate their health and are maintained by a balance of genetic and dietary factors1, 5. A tightly regulated barrier is required for proper compartmentalization of microbe populations8. In the intestine, disruption of this barrier can result in systemic dissemination of microbes and entry into the hepatic portal circulation1. Furthermore, the intestinal lamina propria is highly enriched in lymphatic vessels, which allow access to the mesenteric lymph nodes (MLNs) and eventual drainage into systemic circulation1, 9. Finally, the gut is innervated by several hundred million neurons. Although this is a less understood and less conventional route, retrograde traffic along enteric neurons can disseminate microbes that leak through the intestinal barrier10. A comprehensive understanding of intestinal barrier physiology is required to understand how alterations can lead to disease. We review the components of the intestinal barrier and mechanisms of pathological changes in the gut barrier, increased intestinal permeability, and pathogenesis of liver diseases.

The Intestinal Barrier

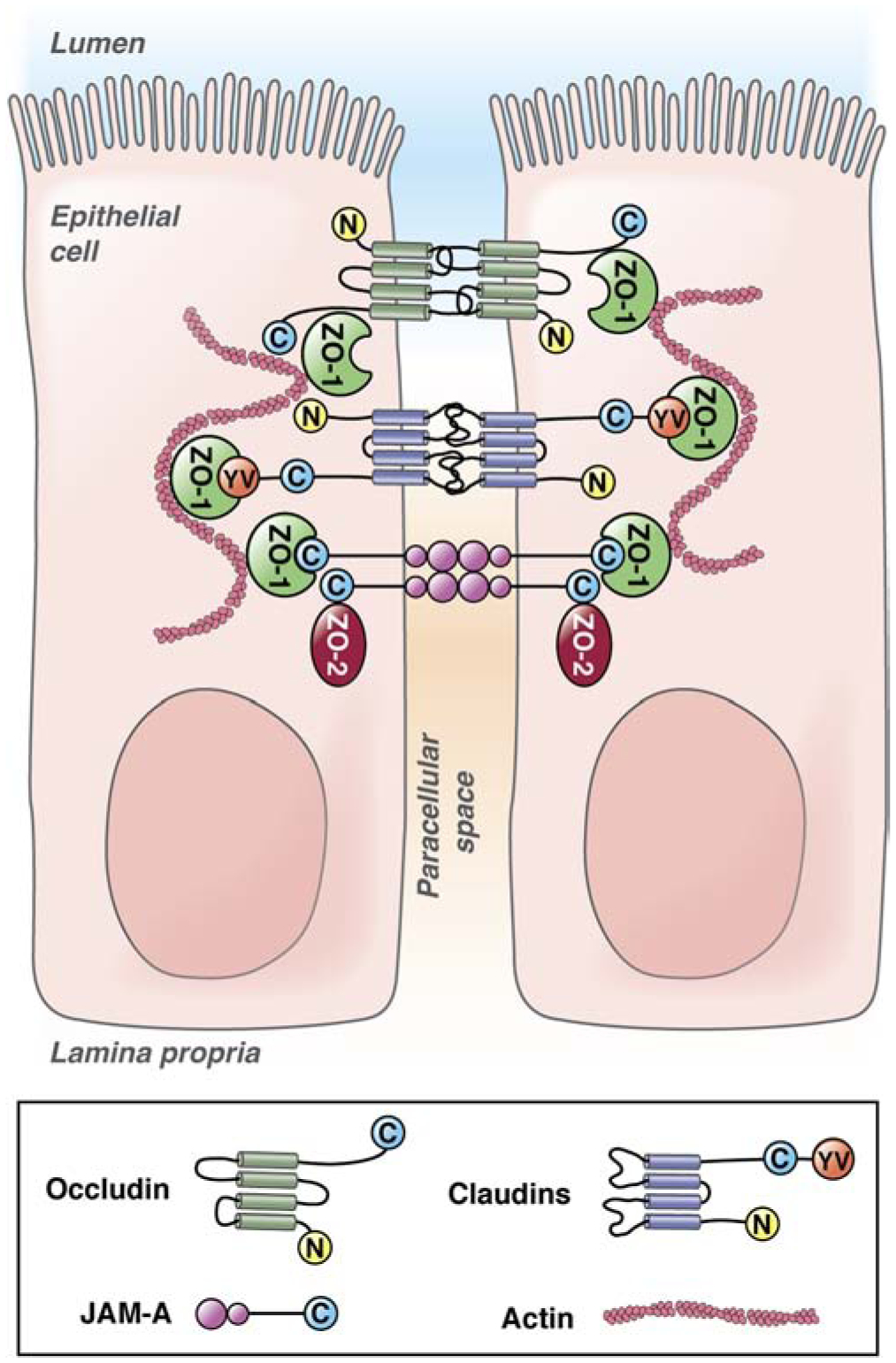

The intestinal barrier comprises physical, immunologic, and microbial components (Figure 1). The physical barrier has epithelial and mucus elements. The intestinal epithelium contains resilient, occlusive intracellular junctions called tight junctions (TJs)11. TJs are found at the apical surface of cells and are composed of transmembrane proteins, signaling molecules, and membrane-associated scaffolding proteins that anchor TJ to the actin cytoskeleton12, 13. TJ transmembrane proteins include tight junction-associated MARVEL proteins (TAMPs), claudins, and junctional adhesion molecules (JAMs)12 (Figure 2). TAMPs such as occludin are well studied, yet their functions have not been completely characterized. TJs can form in the absence of occludin, so this protein might have functions other than contributing to TJ structure14. Other TAMP family members, such as MARVELD2 and MARVELD3, can partially compensate for loss of occludin, so further studies are needed to determine the functional niches of these proteins15.

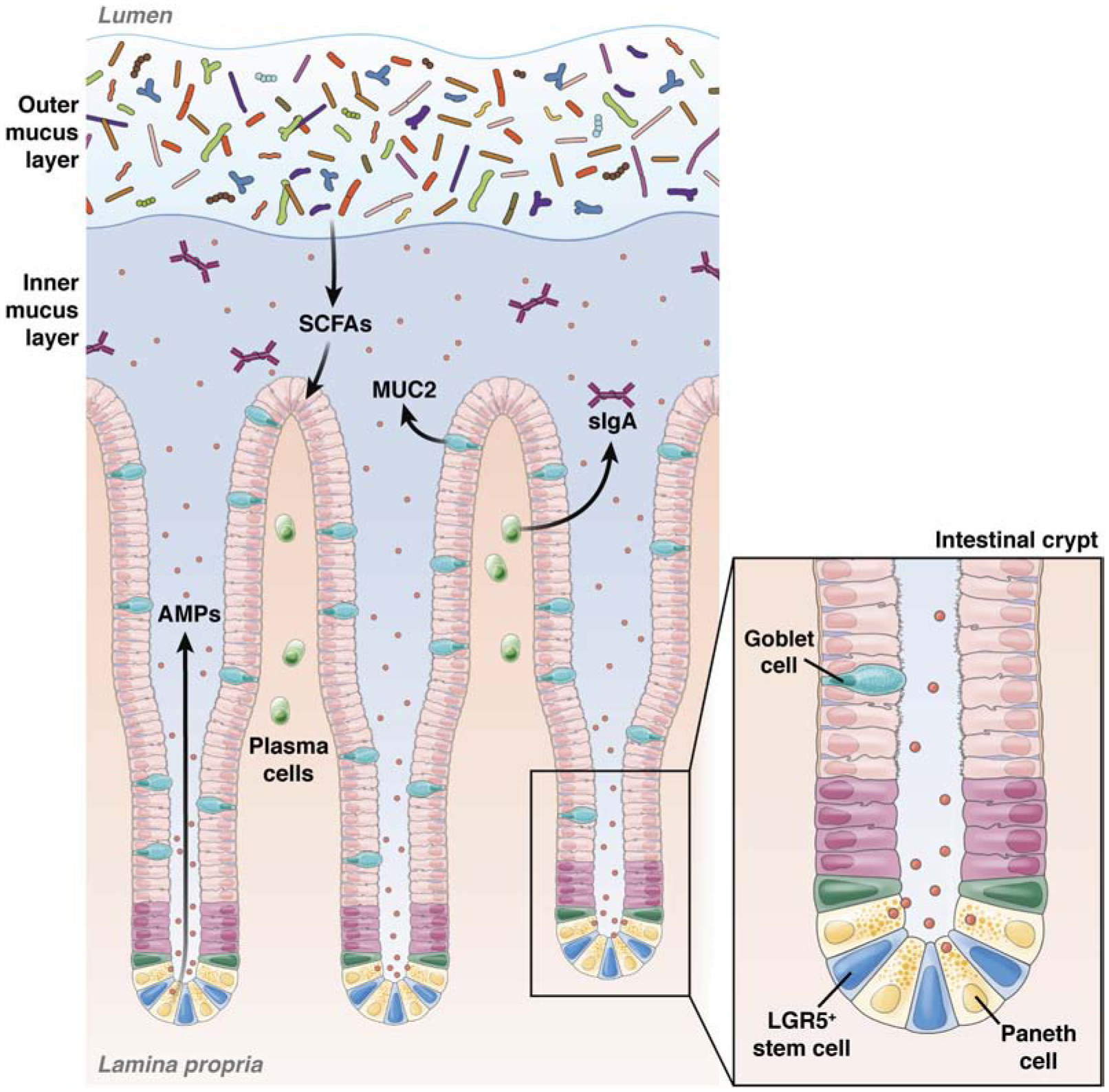

Figure 1. Components of the gut barrier.

The intestinal barrier comprises mucus, microbial, epithelial, and immunological components. Within the colon the mucus forms 2 layers—a more loose, outer layer where most of the intestinal bacteria reside, and a dense, inner layer that does not contain bacteria. The commensal microbiota reinforce the gut barrier by preventing colonization by pathogens and producing useful metabolites such as SCFAs, which promote epithelial health and integrity. Goblet cells are scattered through the intestinal epithelial monolayer and produce mucus. Additional specialized cellular populations are found within the bases of the intestinal crypts. LGR5+ cells are a source of continuous cell renewal to maintain epithelial integrity. These stem cells give rise to differentiated Paneth cells, which remain at the base of the crypts and produce large amounts of antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) and growth factors. Plasma cells within the lamina propria also secrete dimeric Ig A, which is transported across epithelial cells and contributes to immune exclusion of the luminal microbiota. MUC2, mucin 2; sIgA, secretory IgA.

Figure 2. Intestinal epithelial tight junctions.

Intestinal epithelial tight junctions are composed of 3 classes of transmembrane proteins that associate with scaffolding proteins that link to the actin cytoskeleton. The transmembrane proteins include occludin, claudins, and JAMA. Occludin and claudin proteins have cytoplasmic N- and C-termini and 4 transmembrane domains. JAMA has a cytoplasmic C-terminus and 2extracellular V-type Ig domains. Importantly, JAMA can dimerize in cis (molecules on the same cell) and in trans (molecules on adjacent cells).

Claudins are the primary contributor to TJ structure and morphology16, 17. These charge-selective pores regulate the movement of ions and small solutes across epithelial barriers18, 19. There are more than 27 claudin family members, each with their own charge selectivity and molecular pairing capabilities20. JAMs could have accessory roles in TJ function, similar to TAMPs21. However, JAMs have been associated with signaling pathways that regulate cell polarity and maintenance of barrier function, regulating permeability via non-selective pathways22–25. TAMPs, claudins, and JAMs bind scaffolding proteins, such as zonula occludens 1 (ZO1), ZO2, and ZO3, which link them to the actin cytoskeleton12, 13, 19. For reviews of TJ architecture and physiology, see refs 12, 13.

The intestinal epithelium must be able to withstand considerable force as fecal content moves toward the rectum. Many cells die in this process—the human gastrointestinal tract sheds an estimated 1011 epithelial cells per day26. Maintenance of a continuous epithelium throughout this controlled process of cell sloughing is critical for barrier function and necessitates a well-regulated source of cell renewal. Adult stem cell populations in intestinal crypts continuously divide and renew the intestinal epithelium every 3–5 days26, 27.

The rapidly dividing crypt base columnar stem cells that express the leucine rich repeat containing G protein-coupled receptor 5 (LGR5) give rise to most mature intestinal epithelial cells26, 28. Single LGR5-positive cells can form self-renewing organoids with complete crypt-villus architecture29. Due to their rapidly dividing nature, LGR5+ cells are susceptible to radiation-induced injury and cytotoxic drugs30, 31. New stem cell markers and tools, such as LGR5-green fluorescent protein reporter mice, will increase studies of intestinal stem cells and their importance in gut-liver interactions28, 32, 33.

The intestinal epithelium is supported by a thick layer of mucus that contains highly glycosylated glycoproteins called mucins (MUCs), primarily produced by specialized epithelial cells called goblet cells34. Secreted MUCs (the most abundant is MUC2) and transmembrane MUCs (MUC1, MUC3, MUC4) are part of a dual system in the colon comprising an inner, dense layer that contains few microbes and a loose, outer layer, where most of the colonic microbiota reside35. In addition to acting as a physical barrier and lubricant, the mucus provides carbohydrates for commensal bacteria36–38, inhibits epithelial cell apoptosis39, and facilitates the action of factors secreted by immune cells, acting as a viscous trap for antimicrobial peptides and immunoglobulins (Igs)40.

The intestine contains the most immune cells in the body, including type-I interferon-producing plasmacytoid dendritic cells, innate lymphoid cells, mucosa-associated invariant T cells, and γδT cells41, which combat potential pathogens but maintain tolerance to commensal microbes and ingested food. The immune system contributes to the intestinal barrier by secreting antimicrobial peptides and IgA. Antimicrobial peptides are small and cationic, with innate antimicrobial activities, and are secreted by Paneth cells located at the intestinal crypt base, between LGR5+ stem cells42, 43. Antimicrobial peptides include lysozyme, α-defensins and β-defensins, C-type lectins such as regenerating family member 3 gamma (REG3G), and cathelicidins such as LL37 (ref42). Antimicrobial peptides control commensal microbes and limit colonization by pathogenic microbes42. Due to the diversity of antimicrobial peptides and their ability to target bacterial membranes, most bacteria do not develop resistance to these proteins42. Secreted IgA, alternatively, is a component of the adaptive immune response, produced by lamina propria plasma cells44. It is the most abundantly produced Ig class—about 3g are secreted into the intestinal lumen each day in the average human45. Importantly, IgA is secreted as a dimer and can facilitate crosslinking and entrapment of bacteria, limiting colonization and growth of potential pathogens46. However, some commensal microbes, such as Bacteroides fragilis, use IgA crosslinking to facilitate colonization47. In addition to binding pathogens themselves, secretory IgA neutralizes secreted bacterial toxins45, 48.

Commensal Microbes and Gut Barrier Function

Intestinal commensal microbes promote health, in part, by reinforcing the gut barrier via direct and indirect mechanisms5, 49. Commensals provide a direct barrier to colonization by pathogenic microbes through competition for space and nutrients, called colonization resistance8, 50, 51. Moreover, commensals provide continuous stimulation of pathogen recognition receptors such as toll-like receptors (TLRs) on enterocytes and Paneth cells to increase the production of MUCs and antimicrobial peptides34, 42. Mucosal adherent commensal bacterial populations, such as the mucolytic Akkermansia muciniphila, are important for homeostatic epithelial cell stimulation5, 52, 53. Mucosal adherent bacteria are less abundant than luminal bacteria and are a different population of organisms5. Furthermore, commensal microorganisms contribute to adaptive immunity by providing low levels of immune stimulation; this induces IgA production and modulates baseline expression of anti-inflammatory factors that promote maintenance of the epithelial barrier and TJs5, 45. Finally, many commensal bacterial strains produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) such as butyrate from the metabolic breakdown of insoluble fiber. Butyrate is a nutrient for enterocytes that promotes regeneration, and TJ barrier function and maintenance, and has anti-inflammatory properties5, 49, 54.

Hiippala et al explain that it is a challenge to associate specific protective and beneficial effects with specific commensal species, because these are likely to vary among microbe strains and patients5. However, bacteria of the phyla Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes are generally associated with health, whereas increased proportions of Proteobacteria, which are usually at lower frequency in human intestine, are associated with inflammation and disease5. This might be because Proteobacteria, which are gram negative, produce a hexa-acylated form of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) that promotes intestinal inflammation5, 55, 56. Alternatively, gram-negative commensals of other phyla have been associated with health, such as A muciniphila5. In healthy human gut, Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes account for up to 90% of the luminal bacterial load49. Members of these phyla that have also been associated with health include Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and Bacteroides spp.57. F prausnitzii accounts for up to 15% of intestinal bacteria and is a substantial producer of butyrate5, 58.

There are believed to be more than 1000 species of bacteria in the intestine, most of which cannot be cultured, along with commensal viruses, fungi, protozoa, and phage which are far less understood5, 49. Comprehensive approaches that include machine learning, systems biology, and metabolome and microbiology analyses are needed to fully understand this ecosystem.

Disruptions in Intestinal Barrier Function and Liver Disease

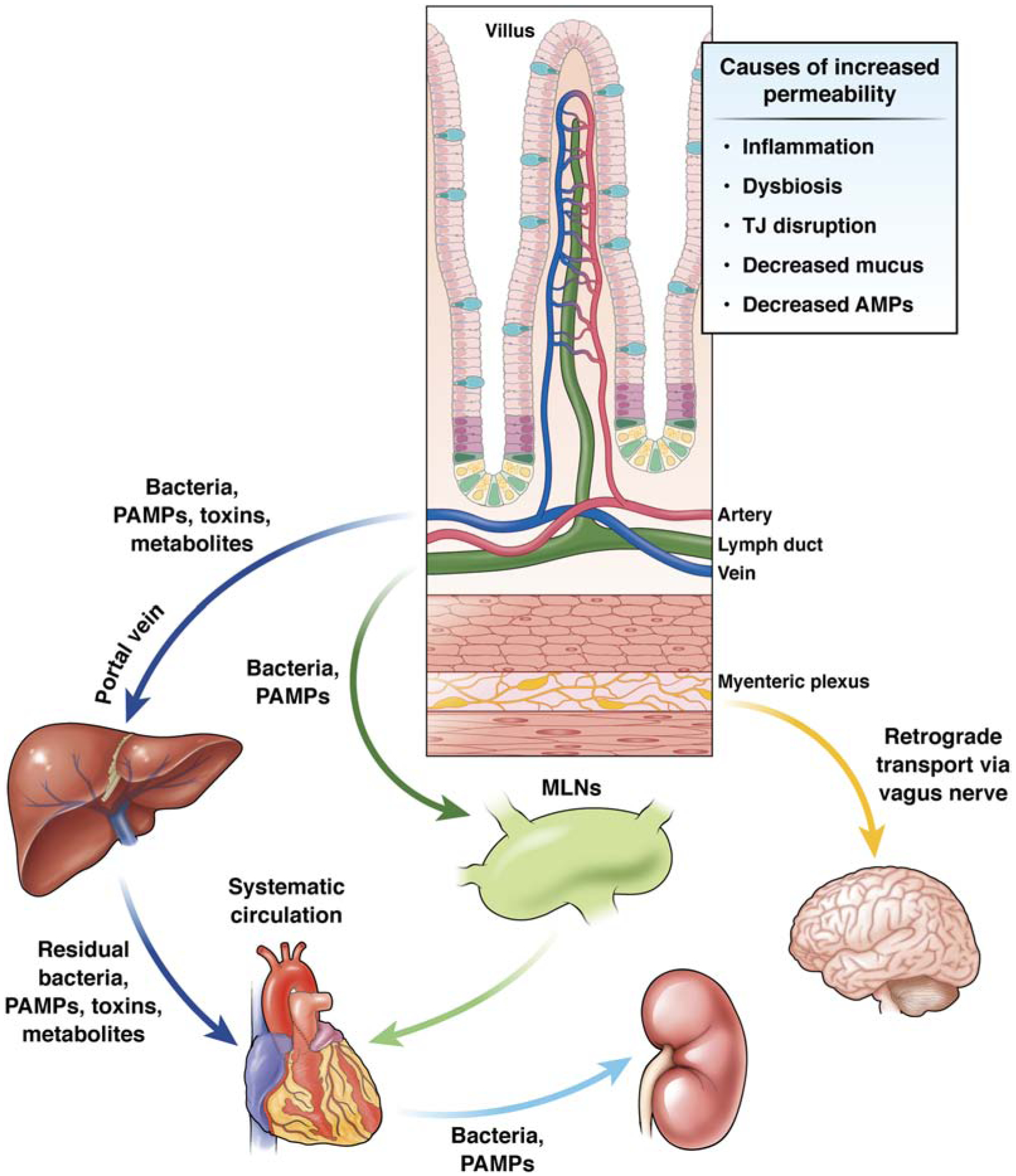

When any aspect of the intestinal barrier fails, even bacteria that generally promote health can wreak havoc and contribute to disease development and injury. For example, the pathobiont B fragilis causes infections and abscesses when it escapes from the gut59. Increased intestinal permeability upon barrier compromise also results in movement of pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) into the blood1, which activate the innate immune response. Release of PAMPS has consequences for organs including brain and kidney10, 60, but also for liver1.

The liver and gut are linked through the portal circulation. In this system, blood flows from the intestine through the portal vein, the sinusoids of the liver for detoxification, and into the hepatic vein before returning to the heart and lungs. PAMPs in portal blood are therefore first encountered by the immune cells in the liver (Figure 3)1. PAMPS such as LPS and bacterial and viral RNAs activate pathogen recognition receptors such as TLR4 on Kupffer cells (liver resident macrophages) and other immune cells to induce the innate immune response. Hepatic inflammation contributes to development of liver injury and disease1, 9.

Figure 3. Mechanisms of gut barrier dysfunction and routes for systemic entry of translocated bacteria and toxins.

Conditions such as dysbiosis, inflammation, and TJ dysfunction can increase gut permeability. When the intestinal barrier is compromised, translocated bacteria and microbial toxins can gain axis to distant sites. Bacteria and PAMPs can enter the portal circulation and access to the liver. The liver contains large populations of immune cells that induce an inflammatory response to these stimuli. A portion of these bacteria, PAMPS, and metabolites pass through the liver where they gain access to the systemic circulation. In parallel, a number of translocated bacteria and PAMPs from the intestine gain access to the lymphatic vasculature, where they first pass through the MLNs. A portion of these intra-lymphatic toxins will enter the systemic circulation. Intestine-derived bacteria, PAMPs, toxins, and metabolites affect the function of organs including the heart, kidney, and brain. Translocated gut pathogens also affect the brain via retrograde transport along fibers of the vagus nerve that contribute to the myenteric plexus.

Mechanisms of intestinal leakiness vary and are incompletely understood. For instance, disruptions to the epithelium can be caused by physical trauma, TJ disruption, and alterations in epithelial stem cell turn over, among other causes8. Alterations in mucus layer thickness, character, or quality contributes affect access of bacteria to nutrients and oxygen, and therefore their survival and proliferation37. Deficiencies in either innate or adaptive immune control can also contribute to translocation of microbes8, 61. Overgrowth and alterations in the diversity of the intestinal bacterial populations (dysbiosis) can lead to intestinal inflammation and gut barrier compromise1, 49. Quantitative and qualitative changes in gut microbial populations have been associated with diseases—it might be possible to assess intestinal dysbiosis by calculation of the ratio of autochthonous to nonautochthonous taxa62. To do this, we need to increase our understanding of the mutual and competitive relationships among commensal strains that maintain stability in this ecosystem63.

Although the intestine has effects on the liver, via the portal circulation, the liver also communicates back to the gut, via hepatic bile flow and the release of mediators into the circulation1. Therefore, it is not always evident whether the gut leakiness and dysbiosis are causes or results of liver disease. For example, biological and environmental factors that affect liver function (age, sex, diet, toxins, etc) also affect intestine physiology and gut microbial diversity5, 8, 49. It is not clear whether gut leakiness and/or intestinal dysbiosis occur during early stages of liver injury or result from altered liver function. There is evidence that gut leakiness contributes to systemic inflammation and disease progression, if it is not the direct cause8.

Alcohol-induced liver disease (ALD)

Alcohol consumption was estimated to contribute to 3 million deaths worldwide (5.3% of total deaths) in 201664. A significant proportion of these deaths were ascribed to ALD—a spectrum of liver disorders that range from steatosis to steatohepatitis, cirrhosis, and eventually cancer65. Nearly half of liver cirrhosis-related mortality is due to alcohol abuse64. The mechanisms by which alcohol consumptions leads to liver injury and progression are incompletely understood—only about 30% of heavy drinkers develop clinically significant ALD such as steatohepatitis and cirrhosis65, 66.

Increased intestinal permeability contributes to pathogenesis of ALD. Serum samples from patients with ALD have increased levels of endotoxin, and binge drinking causes transient endotoxemia in healthy subjects67–69. Ethanol, and its metabolite acetaldehyde, disrupt epithelial TJs66. Junction proteins affected by exposure to these toxins include transmembrane proteins (occludin, JAMA, and claudins), scaffolding proteins (ZO1), and associated signaling molecules such as myosin light chain kinase (MLCK), RHOA, and RAP266, 70–73. For example, expression of occludin is significantly reduced intestinal tissues of mice after ethanol feeding74. Mice deficient in occludin are more susceptible to ethanol-induced liver injury75.

ALD has also been associated with altered intestinal epithelial stem cell functions and direct epithelial injury. Cho et al reported increased intestinal apoptosis alongside TJ protein degradation in ethanol-fed rodents70. Moreover, Lu et al observed a decrease in LGR5 in the small intestines of ethanol-fed mice32. Additional cell surface markers and strains of reporter mice are needed to better study the effects of ethanol on intestinal stem cells. Changes in cell adhesion and epithelial regeneration might increase the susceptibility of the intestinal mucosa to the effects of chronic alcohol consumption76.

Alcohol consumption can increase intestinal bacterial and fungal dysbiosis, which contribute to disease susceptibility, loss of gut barrier function, and progression of liver injury77–80. Mice given antibiotics develop less severe liver injury, and do not have intestinal reductions in occludin expression, with ethanol feeding74, 81. However, germ-free mice, which lack commensal bacteria, develop more severe ethanol-induced injury than conventionally housed mice (with commensal bacteria). This might be because germ-free mice metabolize ethanol faster than conventionally housed mice82.

Intestinal tissues from mice with ethanol feeding have reduced expression of the antimicrobial peptide REG3G, and mice deficient in REG3G develop more severe liver disease with ethanol feeding83, 84. This finding indicates that alterations in the innate immune response contribute to intestinal barrier dysfunction and liver injury in response to ethanol. Antimicrobial peptides might therefore be developed as therapeutics for patients with ALD. For example, gavage of mice with engineered bacteria that express recombinant interleukin 22 (IL22) induces expression of REG3G and reduces the severity of ethanol-induced liver injury85.

Patients with ALD have reduced gut motility and small intestinal bacterial overgrowth76. Colon biopsies from patients with ALD were enriched in Proteobacteria whereas the abundances of Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes were reduced86. However, fecal samples from patients with severe alcohol-associated hepatitis had higher proportions of Bifidobacteteria, Streptococci, and Enterobacteria than samples from controls78. Furthermore, use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), which promotes small intestinal bacterial overgrowth87, is a risk factor for spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, more severe hepatic encephalopathy, and greater mortality88, 89. Llorente et al demonstrated that ethanol-fed mice treated with PPIs had overgrowth and increased gut translocation of Enterococcus spp. whereas human patients with ALD who used PPIs also had enrichment of Enterococcus spp. in their feces.90.

Duan et al reported that expression of cytolysin by Enterococcus faecalis, rather than just its overgrowth, is associated with ALD severity. The authors found a stronger correlation between detection of cytolysin and severity of liver disease and mortality in patients with alcoholic hepatitis than other prognostic factors, such as model for end-stage liver disease or ABIC scores91. Bacteriophages that target cytolytic E faecalis decreased cytolysin in liver, and reduced the severity of ethanol-induced liver disease, in humanized mice colonized with bacteria from feces of patients with alcoholic hepatitis91. Further clinical studies are needed to verify these findings, which indicate the potential for microbiome-based therapies.

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)

NAFLD can progress from steatosis to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), fibrosis, cirrhosis, and eventually cancer92. NAFLD has become the most common chronic liver disease and a global health concern—the global prevalence of NAFLD is approximately 25%93. The largest risk factors for NAFLD and NASH are obesity and metabolic syndrome; it is estimated that 39% of the adult population worldwide is overweight and 13% is obese93. NAFLD, NASH, and ALD have similarities in mechanisms of pathogenesis. NAFLD and NASH begin with altered lipid metabolism, insulin resistance, and metabolic syndrome which lead to steatosis. Persistent liver inflammation, intestinal dysbiosis, and gut leakiness contribute to progression of NAFLD to NASH, fibrosis, and cirrhosis92, 94. Although this is an oversimplification, altered lipid metabolism and gut leakiness likely work together to initiate and facilitate fatty liver disease.

Turnbaugh et al demonstrated that the intestinal microbiome of genetically obese mice (higher ratio of Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes) had an increased capacity to harvest energy from the diet compared with the intestinal microbiome of lean mice95. Obese mice also have disrupted intestinal TJs, due in part to altered localization and reduced expression of ZO1 and occludin96–99. Furthermore, livers of obese rats are more sensitive to LPS stimulation and their Kupffer cells have reduced phagocytic function100. Patients with NAFLD have a higher prevalence of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth and gut leakiness compared with lean persons. Interestingly, the degree of hepatic steatosis, but not the presence of NASH, correlated with the level of gut leakiness and the presence intestinal bacterial overgrowth101. More recently, mice deficient in JAMA were reported to develop more severe steatohepatitis than control mice when placed on a diet high in saturated fat, cholesterol, and fructose102. Fatty liver and steatohepatitis were prevented in the mice deficient in JAMA by administration of antibiotics or sevelamer hydrochloride, a bile acid-binding resin with LPS binding activity102. Though these findings are similar to those from studies of ALD, it is not clear how the mechanisms of TJ disruption differ with ethanol exposure vs a high-fat diet.

Although patients with NAFLD or NASH have alterations in their intestinal microbiomes, the specific alterations in phyla and species have not been as well defined as they have for patients with ALD77, 103. Changes in the immune response and metabolome shaped by these microbes might have greater effects than the specific microbe strains themselves. Moreover, it is a challenge to compare findings from different studies, because they use different methods for diagnosis of NAFLD (such as ultrasonography, magnetic-resonance imaging, biopsy), and include patients with different stages of disease, which are associated with distinct microbiome profiles77, 103, 104. One of the most common findings is that microbiomes of patients with NAFLD or NASH are enriched in gram-negative bacteria whereas gram-positive bacteria are reduced—specifically, the abundance of butyrate-producing bacteria are reduced77, 103–105.

In mice on a high-fat diet, sodium butyrate feeding reduced dysbiosis, endotoxemia, and liver inflammation and fat106. Alternatively, mice given subcutaneous infusions of LPS increased fasting glycemia; insulinemia; and whole-body, liver, and adipose tissue weight gain, to a similar extent as in mice on a high-fat diet107. Microbiomes of patients with NASH and obese mice are also enriched in Escherichia coli, which are associated with increased endogenous production of ethanol, which can increase intestinal permeability108–110. Moreover, alterations in bile acid metabolism brought about by obesity-associated microbiota profiles contribute to pathogenesis of NAFLD and NASH (for reviews, see refs 111, 112). However, germ-free mice are more and less susceptible to fatty liver and steatohepatitis, depending on the strain and the diets administered77. It is unclear to what extent intestinal dysbiosis contributes to NAFLD progression.

Uniform composition in diets (sources of fat and protein), rather than consistency in the dietary contribution of macronutrients (percent fat, carbohydrate, and protein), is needed for consistency among studies in mice. Dietary studies should also include more robust metabolomic assessments, in relation to the microbiota, during development of liver injury. Meta-analyses must carefully select clinical data for inclusion, in light of differences in patient demographics, severity of NAFLD and NASH, and methods of diagnosis.

Drug-induced liver injury (DILI)

Drugs are a common cause of liver injury, and DILI is one the most frequent reasons for drug non-approval or withdrawal. DILI is frequently caused by high doses of drugs with known hepatotoxic effects, but some patients develop unpredicted or idiosyncratic injury (iDILI)113. Practically any drug is capable of inducing iDILI; there are more than 1000 drugs associated with iDILI cases. iDILI tends to occur after a longer periods of drug use, in a small subset of at-risk persons. Although iDILI is a significant health concern, its unpredictability and broad range of phenotypes makes it difficult to study113, 114.

Acetaminophen is a commonly used antipyretic and analgesic, but its overdose is the leading cause of acute liver failure in western countries115. This drug is widely used, due to its favorable side-effect profile compared with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and opiates. However, the metabolic breakdown of acetaminophen by hepatic cytochrome P4502E1 generates the highly reactive toxic metabolite N-acetyl-p-benzoquinione imine116. At therapeutic doses, N-acetyl-p-benzoquinione imine is reduced by the hepatic antioxidant glutathione and is typically safely tolerated. However, large doses result in depletion of hepatic glutathione, leading to formation and accumulation of protein adducts and widespread liver necrosis116.

However, there is evidence for immune-mediated injury in the liver from acetaminophen overdose, so agents that alter the inflammatory response might be developed for treatment116, 117. Mice given acetaminophen develop transient portal endotoxemia; inhibition of LPS-binding protein by a synthetic peptide, but not disruption of the gene that encodes this protein, reduced acetaminophen hepatotoxicity118, 119. Yang et al demonstrated increased intestinal permeability to 4 kDa fluorescein isothiocyonate-dextran and evidence of bacterial translocation into the MLNs in mice with acetaminophen intoxication120. Neutralization of the cellular damage marker HMGB1 limited bacterial translocation but did not reduce dextran permeability120. The mechanism behind acetaminophen-induced gut permeability is unclear; although Yang et al proposed a role for gut mucosal injury following acetaminophen toxicity, until recently there was no convincing data to demonstrate such an effect120.

Possamai et al reported an increase in serum markers of apoptosis in portal vein blood, compared to hepatic vein blood, from patients with acetaminophen-induced acute liver failure undergoing liver transplantation121. The authors proposed acetaminophen-induced apoptosis of enterocytes, similar to that observed in patients with sepsis, was the likely explanation for these findings121. However, in mice, LGR5+ cells in the intestine undergo rapid and specific apoptosis during acetaminophen intoxication33—these cells might also release markers of apoptosis into the blood of patients. Death of the stem cell niche could have long-lived consequences.

Differences in the intestinal microbiota might contribute to the varying clinical phenotypes of patients with acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity, contributing to differences in acetaminophen metabolism and the overall metabolome. Possamai et al found that within 8 hours of acetaminophen intoxication in germ-free mice, the extent of early liver injury was equivalent to conventionally housed animals. However, in germ-free mice, there was non-significant trend toward lower serum bilirubin and creatinine levels, so it is possible that they have less liver injury at later time points122.

Conversely, diurnal variations in commensal microbiota have been associated with susceptibility to acetaminophen intoxication123. In this study, variations in microbe populations and an increase in cecal concentration of the microbial metabolite 1-phenly-1,2-propanedione were observed at the start of the active cycle compared with the resting cycle in mice. Increasing amounts of this metabolite in mice exacerbated acetaminophen hepatotoxicity, whereas antibiotic pretreatment prevented acetaminophen-induced liver injury123. These findings indicate that circadian variations in the intestinal microbiota affect susceptibility to acetaminophen-induced liver injury. Studies are needed to identify other features of the intestinal microbiota that affect acetaminophen-induced liver injury and iDILI.

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC)

PSC is a chronic idiopathic cholestatic liver disease that involves progressive sclerosis (scarring) of the biliary tree. It is characterized by persistent biliary inflammation that results in periductal fibrosis, destruction of the bile ducts, and liver cirrhosis124, 125. PSC is most common in individuals of Northern European ancestry and the prevalence is nearly twice as high in men than in women124. By definition as a disease of cholestasis, PSC involves accumulation and regurgitation of toxic bile salts that promote liver inflammation and injury.

Genetic, immune system, and environmental factors, including diet, appear to contribute to PSC risk and pathogenesis124. There are also strong contributions from intestinal inflammation, leakiness, and dysbiosis—approximately 75% of patients with PSC also have inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD)126. However, only about 7%–8% of patients with IBD also have PSC124, 126. Interestingly, most patients with PSC-IBD have colon inflammation, and their microbiome profile more closely resembles that associated PSC vs only IBD126–128. Therefore, gut leakiness and intestinal dysbiosis might contribute to PSC pathogenesis. LPS has been detected in cholangiocytes in liver biopsies from patients with PSC129. Patients with PSC have also been reported to have increased gut leakiness, and degree of gut leakiness correlated with worse outcomes130, 131.

The association of PSC with IBD supports the hypothesis that PSC has an autoimmune etiology124. Alterations to the intestinal microbiome might contribute to this etiology, in that immune responses to bacterial antigens sometimes cross react with self-antigens with similar structures132. Auto-antibodies that also react with bacterial proteins have been isolated from patients with PSC and other hepatic disorders of presumed autoimmune etiology (autoimmune hepatitis, primary biliary cholangitis). For example, p-ANCA, isolated from patients with PSC or with autoimmune hepatitis, binds the bacterial cell division protein FtsZ, and anti-mitochondrial antibodies isolated from patients with primary biliary cholangitis cross react with mycoplasma antigens132–134. Further studies of these mechanisms are needed.

Much less is known about the mechanisms that induce PSC-associated gut barrier dysfunction than ALD and NAFLD. However, a recent study that used bile-duct ligation in mice as a model of cholestatic liver injury demonstrated that gut leakiness was associated with increased intestinal endoplasmic reticulum stress, intestinal epithelial cell apoptosis, and reduced expression of epithelial stem cell marker LGR5135. Nakamoto et al demonstrated enrichment of Klebsiella pneumoniae in fecal samples from patients with PSC who also had ulcerative colitis. Colonization of mice with patient-derived fecal microbes showed that specific strains of K pneumoniae invaded the intestinal mucosa and increased gut leakiness, and were also found to induce pore formation in epithelial monolayer in vitro127. The authors also associated intestinal permeability with a hepatic T-helper 17 cell-mediated immune response that contributed to liver injury127.

Analysis of a genetic model of PSC showed that increases in intestinal Lactobacillus gasseri and subsequent translocation to the liver induced IL17-mediated inflammatory injury by hepatic Vγ6+ γδT cells136. So, even commensal microbes typically associated with health, such as L gasseri, can induces pathogenic immune responses once homeostatic compartmentalization is compromised. Liao et al supported these findings, demonstrating dysbiosis-induced intestinal inflammation and gut leakiness, via the NLRP3 inflammasome, in a mouse model of PSC125. These mice had reduced intestinal expression of ZO1 and MUC2125. PSC is also associated with alterations in the entero-hepatic circulation of bile acids and altered bile acid metabolism137, 138. Studies are needed to determine how intestinal dysbiosis and gut leakiness contribute to development of PSC and other cholestatic liver diseases.

Cirrhosis, Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis (SBP), Hepatic Encephalopathy (HE), and Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC)

Prolonged liver inflammation results in cirrhosis and end-stage liver disease (ESLD) that places patients at risk for SBP, HE, and ultimately HCC139. Compared with healthy individuals, patients with cirrhosis have slower intestinal transit time, intestinal bacterial overgrowth, and altered fecal microbial profiles, with enrichment of Proteobacteria and Fusobacteria and reduced Bacteroidetes139–142. Fecal microbial signatures of patients with cirrhosis vary with disease severity (compensated vs uncompensated cirrhosis) and might be used to predict outcomes of hospitalized patients143. Intriguingly, liver transplantation has been correlated with partial reversal of the gut dysbiosis associated with cirrhosis. Although common medications and disease sequelae after transplant (antibiotics, immunosuppressants, infections) affect the gut microbiome and intestinal immune function, the microbiota would also be affected by the functions of the new liver (on energy metabolism, bile acid production, etc)144, 145.

SBP is infection of the ascitic fluid in patients with cirrhosis, which might result from increased translocation of bacteria from the intestine. Higher proportions of patients with cirrhosis have culturable bacteria from MLNs and endotoxemia compared with healthy persons146, 147. This could be due to enrichment of gram-negative bacteria in the intestinal microbiota—particularly of Enterobacteriaceae147. Members of the Enterobacteriaceae family (E coli, K pneumoniae) are also the most commonly identified pathogens in the ascitic fluid from patients with SBP89, 148. Patients with cirrhosis who use PPIs are increased risk of SBP, due to intestinal overgrowth of Enterococcus spp.90, 149.

Support for the concept of interaction between the gut and liver comes from the fact that HE is commonly treated with lactulose and rifaximin, which are poorly absorbed by the intestine but have effects there150. HE is a serious complication of ESLD characterized by neurocognitive impairments including confusion, lethargy, incoherent speech, sleep disturbances, and eventually coma88. The pathogenic mechanisms of HE are incompletely understood but appear to involve intestinal dysbiosis, increased production of ammonia by human cells and microbes, and systemic inflammation148, 151, 152. Kang et al found that germ-free mice with liver fibrosis have lower serum levels of ammonia than conventionally housed mice with liver fibrosis, and unlike the conventional mice, the germ-free mice do not develop a neuroinflammatory response. In the same study, Lactobacillae enrichment correlated with enhanced neuroinflammation in conventionally housed mice with liver fibrosis151.

Patients with cirrhosis with HE have similar fecal microbiota profiles as patients with cirrhosis without HE53, 154. However, comparisons of patients with HE vs healthy controls correlated Porphyromonadaceae and Alcaligeneceae with cognitive impairment. Interestingly, Alcaligeneceae contributes to ammonia production via degradation of urea, but this observation was limited by the fact that over 90% of patients with HE were taking PPIs, whereas none of the control patients were on these medications154. It is therefore likely that changes in either the mucosal adherent bacteria (enrichment in Enterococcus and Burkholderia) or gut microbial function (metabolome) determine risk for HE153. In support of this hypothesis, neither lactulose nor rifaximin causes large changes in gut microbial profiles, but instead these agents increase serum carbohydrate and fatty acid metabolites and alter the bile acid pool150, 155.

Sustained liver inflammation resulting from chronic gut leakiness and intestinal dysbiosis can promote oncogenesis. HCC most frequently develops in patients with advanced ESLD156. Mechanisms by which the intestinal microbiome contributes to development and progression of HCC vary with the etiology of ESLD, but there are notable commonalities. Dapito et al demonstrated that LPS signaling via TLR4 contributes to development of HCC in mice—particularly at the later stages of cirrhosis. The authors showed that conventional mice given antibiotics, and germ-free mice, were protected from hepatic tumorigenesis, and that TLR4 signaling on liver-resident cells mediated hepatic oncogenesis, in part by inhibiting hepatocyte apoptosis and upregulation of growth signals such as epiregulin in hepatic stellate cells157. These findings were supported by the observation that concurrent induction of colitis with dextran sulfate sodium in mice fed a methionine/choline-deficient diet to induce steatohepatitis promoted hepatic tumorigenesis156, 158.

Alterations in the gut microbiome contribute to a tumorigenic environment in the liver via modulation of the intestinal metabolome, bile acid pool, and immune response159. Ma et al demonstrated that the bile acid-metabolizing, gram-positive Clostridium cluster XIV promote growth of liver tumors in mice. Increased production of secondary bile acids (such as taurodeoxycholic acid in mice) was associated with reduced numbers of intrahepatic C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 6 (CXCR6)-positive anti-tumor natural killer T cells. Administration of vancomycin to mice reduced the abundance of Clostridium spp., increased the relative abundance of primary to secondary bile acids, and increased recruitment of CXCR6-poisitive natural killer T cells to liver, reducing tumor burden160. Similar results were observed in models of metastatic cancer, including hepatic melanoma160, 161. Moreover, the composition of the intestinal microbiota has been associated with response to immune checkpoint inhibitors, such as PDL1 inhibitors, in patients with cancer and in mice162. The intestinal microbiome and metabolome are likely to be important components of personalized therapies in oncology.

Therapeutic Strategies

Strategies to alter the intestinal microbiome might be developed for treatment of liver diseases. Antibiotics have non-specific effects on intestinal bacteria, and their use can lead to development of resistant strains, expansion of pathogens such as Clostridium difficile, and drug related toxicities163. Specific bactericidal agents might circumvent the adverse effects of conventional antibiotics. Bacteriophages, which kill specific strains of bacteria, reduced ethanol-induced liver disease in mice91. There have been preclinical studies and case reports of the effects of bacteriophages for treatment of multidrug resistant infections, but the risks are unclear—there could be public health risks if their use becomes widespread164.

Fecal microbiota transplant (FMT) from healthy donors is effective in treatment of refractory C difficile infection165. FMT currently provides the most practical approach to reconstituting a healthy gut microbiome, encompassing nearly all of its members and functionality. Early-stage clinical trials have shown the potential effects of FMT in patients with cirrhosis and HE, but more studies are needed to establish long-term safety and efficacy166–168.

Rather than killing off potentially malicious gut microbes, another approach is to support colonization, growth, and function of beneficial microbes, through the administration of pre- and probiotics163. Some groups are exploring the use of genetically manipulated bacterial strains as drug delivery systems. Bacteria engineered to produce IL22 in intestines of mice reduced ethanol-induced liver disease85. SYNB1020, an E coli Nissle 1917 strain engineered to synthesize large amounts of L-arginine, reduced hyperammonia in mice and was being tested for use in patients with HE but was recently discontinued due to lack of clinical improvement upon interim analysis169.

Small metabolites and proteins produced by gut microbiota, called postbiotics, are also being studied170. The commensal gut microbiome performs metabolic processes that cannot be performed by the human body, such as production of SCFAs from insoluble dietary fibers49. Gao et al demonstrated that supplementation with oral HM0539, a protein secreted by Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG, via a pectin/zein hydrogel delivery system, protected mice from colitis171. Direct supplementation with, or inhibition of, bacterial metabolites might therefore provide health benefits. Secreted bacterial products can be screened, similar to high-throughput screening of other agents, as part of drug discovery processes.

Release of LPS and other bacterial toxins are thought to be the primary means through which intestinal permeability contributes to hepatic injury, so strategies to block their leakage into the circulation might be developed for treatment. Lactulose, used for treatment of HE, causes gut microbes to acidify the colon, transforming the diffusible ammonia into ammonium ions that can no longer diffuse into the blood; the ammonium is excreted feces163. Bile acid-binding sequestrants such as colesevelam have been used for treatment of hypercholesterolemia172. Other compounds in this class, such as sevelamer hydrochloride, bind and sequester LPS and might be used to treat liver diseases102. This therapeutic strategy could be improved with engineering of non-absorbable, porous materials such as Yaq-001, which is being evaluated for safety in trials of patients with cirrhosis173.

There are fewer therapeutics in development for altering the effects of the liver on the intestinal microbiota. Bile composition and flow have effects on the intestinal microbiota, and liver disorders are associated with shifts in the enterohepatic bile acid pool1. Bile acids have pleiotropic effects and synthetic bile acids are being studied as therapeutics for hepatic and metabolic disorders174. The semi-synthetic bile acid obeticholic acid (OCA) was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2016 for treatment, in combination with ursodeoxycholic acid, of primary biliary cholangitis. OCA is being tested in phase 3 trials of patients with NASH-related fibrosis, with positive results from an interim analysis175, 176. However, OCA increases low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and causes pruritis175.

In an effort to minimize adverse effects, non-bile acid compounds that act directly upon bile acid signaling pathways are being explored for therapeutic potential. For example, the intestine-specific farnesoid X receptor agonist fexaramine was shown reduces ethanol-induced liver injury in mice177. Further studies of bile acid receptor signaling pathways will likely identify additional therapeutic targets. For reviews of the interactions between the liver and the intestinal microbiome and potential therapies, see refs 163, 173, 178.

Future Directions

We are only beginning to understand the relationships among the intestinal microbiome, permeability, and liver function. We now need to move beyond association studies to mechanistic studies. As technology progresses, these types of studies could become easier and quicker to perform. We are constantly identifying additional factors that modify the intestinal microbiome, such as hormones and age—all of these will affect development of personalized therapeutics.

Studies of the interactions between the gut and liver remind us that basic science studies should consider the interactions among all parts of the body, rather than events in a single cell or tissue. This is not a novel concept—it has been long taught and applied in clinical medicine. Although this review has focused on the liver, the intestinal microbiome affects other organs, including the brain179. Therapeutic strategies to alter the intestinal microbiome, with probiotics, antibiotics, FMT, hormones, interceptive interventions such as with sevelamer hydrochloride, and even bacteriophage hold exciting possibilities. These might one day be effective, with proper technological advancements74, 91, 102, 123, 152, 180, 181. Even the associations we have identified might be used as biomarkers and to develop functional assays for more timely disease detection and more accurate risk calculation91, 182.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Drs. Manoj Thapa, Jake Choby, and David Weiss for fruitful scientific discussion and mentorship in planning this review. We also acknowledge the contributions of graphic designer Krystel Chopyk in generating the infographic summary figures for this work.

Funding

This project was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants R01AI136533, R01AI124680, R01AI096882 and R01AI126890 to A.G.; Office of Research Infrastructure Programs/Office of the Director (ORIP/OD) P51OD011132 (formerly National Center For Research Resources (NCRR) P51RR000165) to the Yerkes National Primate Research Center (A.G.); and the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) Ruth L. Kirschtein National Research Service Award (NRSA) Individual Predoctoral Fellowship (F31AA024960) to D.M.C.. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Abbreviations:

- PAMPs

Pathogen associated molecular patterns

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- TJs

tight junctions

- TLRs

toll-like receptors

- ALD

alcoholic liver disease

- NAFLD

non-alcoholic liver disease

- DILI

drug induced liver injury

- PSC

primary sclerosing cholangitis

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Potential conflict of interest: Nothing to report.

References

- 1.Tripathi A, Debelius J, Brenner DA, et al. The gut-liver axis and the intersection with the microbiome. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018;15:397–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Powell N, Walker MM, Talley NJ. The mucosal immune system: master regulator of bidirectional gut-brain communications. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;14:143–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pasini E, Aquilani R, Testa C, et al. Pathogenic Gut Flora in Patients With Chronic Heart Failure. JACC Heart Fail 2016;4:220–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang J, Lim SY, Ko YS, et al. Intestinal barrier disruption and dysregulated mucosal immunity contribute to kidney fibrosis in chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2019;34:419–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hiippala K, Jouhten H, Ronkainen A, et al. The Potential of Gut Commensals in Reinforcing Intestinal Barrier Function and Alleviating Inflammation . Nutrients 2018;10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cervantes-Barragan L, Chai JN, Tianero MD, et al. Lactobacillus reuteri induces gut intraepithelial CD4(+)CD8alphaalpha(+) T cells. Science 2017;357:806–810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sender R, Fuchs S, Milo R. Revised Estimates for the Number of Human and Bacteria Cells in the Body. PLoS Biol 2016;14:e1002533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wells JM, Brummer RJ, Derrien M, et al. Homeostasis of the gut barrier and potential biomarkers. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2017;312:G171–G193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang HJ, Gao B, Zakhari S, et al. Inflammation in alcoholic liver disease. Annu Rev Nutr 2012;32:343–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rao M, Gershon MD. The bowel and beyond: the enteric nervous system in neurological disorders. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;13:517–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Farquhar MG, Palade GE. Junctional complexes in various epithelia. J Cell Biol 1963;17:375–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Itallie CM, Anderson JM. Architecture of tight junctions and principles of molecular composition. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2014;36:157–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luissint AC, Parkos CA, Nusrat A. Inflammation and the Intestinal Barrier: Leukocyte-Epithelial Cell Interactions, Cell Junction Remodeling, and Mucosal Repair. Gastroenterology 2016;151:616–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saitou M, Furuse M, Sasaki H, et al. Complex phenotype of mice lacking occludin, a component of tight junction strands. Mol Biol Cell 2000;11:4131–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Raleigh DR, Marchiando AM, Zhang Y, et al. Tight junction-associated MARVEL proteins marveld3, tricellulin, and occludin have distinct but overlapping functions. Mol Biol Cell 2010;21:1200–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Furuse M, Sasaki H, Fujimoto K, et al. A single gene product, claudin-1 or −2, reconstitutes tight junction strands and recruits occludin in fibroblasts. J Cell Biol 1998;143:391–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cording J, Berg J, Kading N, et al. In tight junctions, claudins regulate the interactions between occludin, tricellulin and marvelD3, which, inversely, modulate claudin oligomerization. J Cell Sci 2013;126:554–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Simon DB, Lu Y, Choate KA, et al. Paracellin-1, a renal tight junction protein required for paracellular Mg2+ resorption. Science 1999;285:103–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shen L, Weber CR, Raleigh DR, et al. Tight junction pore and leak pathways: a dynamic duo. Annu Rev Physiol 2011;73:283–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mineta K, Yamamoto Y, Yamazaki Y, et al. Predicted expansion of the claudin multigene family. FEBS Lett 2011;585:606–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martin-Padura I, Lostaglio S, Schneemann M, et al. Junctional adhesion molecule, a novel member of the immunoglobulin superfamily that distributes at intercellular junctions and modulates monocyte transmigration. J Cell Biol 1998;142:117–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Monteiro AC, Sumagin R, Rankin CR, et al. JAM-A associates with ZO-2, afadin, and PDZ-GEF1 to activate Rap2c and regulate epithelial barrier function. Mol Biol Cell 2013;24:2849–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Severson EA, Parkos CA. Mechanisms of outside-in signaling at the tight junction by junctional adhesion molecule A. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2009;1165:10–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mandell KJ, Babbin BA, Nusrat A, et al. Junctional adhesion molecule 1 regulates epithelial cell morphology through effects on beta1 integrins and Rap1 activity. J Biol Chem 2005;280:11665–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ebnet K, Suzuki A, Horikoshi Y, et al. The cell polarity protein ASIP/PAR-3 directly associates with junctional adhesion molecule (JAM). EMBO J 2001;20:3738–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barker N Adult intestinal stem cells: critical drivers of epithelial homeostasis and regeneration. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2014;15:19–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barker N, van Oudenaarden A, Clevers H. Identifying the stem cell of the intestinal crypt: strategies and pitfalls. Cell Stem Cell 2012;11:452–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barker N, van Es JH, Kuipers J, et al. Identification of stem cells in small intestine and colon by marker gene Lgr5. Nature 2007;449:1003–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sato T, Vries RG, Snippert HJ, et al. Single Lgr5 stem cells build crypt-villus structures in vitro without a mesenchymal niche. Nature 2009;459:262–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bhanja P, Norris A, Gupta-Saraf P, et al. BCN057 induces intestinal stem cell repair and mitigates radiation-induced intestinal injury. Stem Cell Res Ther 2018;9:26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yan KS, Chia LA, Li X, et al. The intestinal stem cell markers Bmi1 and Lgr5 identify two functionally distinct populations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012;109:466–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lu R, Voigt RM, Zhang Y, et al. Alcohol Injury Damages Intestinal Stem Cells. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2017;41:727–734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chopyk DM, Stuart JD, Zimmerman MG, et al. Acetaminophen Intoxication Rapidly Induces Apoptosis of Intestinal Crypt Stem Cells and Enhances Intestinal Permeability. Hepatol Commun 2019;3:1435–1449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cornick S, Tawiah A, Chadee K. Roles and regulation of the mucus barrier in the gut. Tissue Barriers 2015;3:e982426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Johansson ME, Ambort D, Pelaseyed T, et al. Composition and functional role of the mucus layers in the intestine. Cell Mol Life Sci 2011;68:3635–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sonnenburg JL, Xu J, Leip DD, et al. Glycan foraging in vivo by an intestine-adapted bacterial symbiont. Science 2005;307:1955–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schroeder BO. Fight them or feed them: how the intestinal mucus layer manages the gut microbiota. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf) 2019;7:3–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sicard JF, Le Bihan G, Vogeleer P, et al. Interactions of Intestinal Bacteria with Components of the Intestinal Mucus. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2017;7:387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ho SB, Dvorak LA, Moor RE, et al. Cysteine-rich domains of muc3 intestinal mucin promote cell migration, inhibit apoptosis, and accelerate wound healing. Gastroenterology 2006;131:1501–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Faderl M, Noti M, Corazza N, et al. Keeping bugs in check: The mucus layer as a critical component in maintaining intestinal homeostasis. IUBMB Life 2015;67:275–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mowat AM, Agace WW. Regional specialization within the intestinal immune system. Nat Rev Immunol 2014;14:667–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mukherjee S, Hooper LV. Antimicrobial defense of the intestine. Immunity 2015;42:28–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nakamura K, Sakuragi N, Takakuwa A, et al. Paneth cell alpha-defensins and enteric microbiota in health and disease. Biosci Microbiota Food Health 2016;35:57–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Inamine T, Schnabl B. Immunoglobulin A and liver diseases. J Gastroenterol 2018;53:691–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Macpherson AJ, Geuking MB, McCoy KD. Homeland security: IgA immunity at the frontiers of the body. Trends Immunol 2012;33:160–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mantis NJ, Rol N, Corthesy B. Secretory IgA’s complex roles in immunity and mucosal homeostasis in the gut. Mucosal Immunol 2011;4:603–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Donaldson GP, Ladinsky MS, Yu KB, et al. Gut microbiota utilize immunoglobulin A for mucosal colonization. Science 2018;360:795–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chairatana P, Nolan EM. Defensins, lectins, mucins, and secretory immunoglobulin A: microbe-binding biomolecules that contribute to mucosal immunity in the human gut. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol 2017;52:45–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Adak A, Khan MR. An insight into gut microbiota and its functionalities. Cell Mol Life Sci 2019;76:473–493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bauer MA, Kainz K, Carmona-Gutierrez D, et al. Microbial wars: Competition in ecological niches and within the microbiome. Microb Cell 2018;5:215–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Litvak Y, Mon KKZ, Nguyen H, et al. Commensal Enterobacteriaceae Protect against Salmonella Colonization through Oxygen Competition. Cell Host Microbe 2019;25:128–139 e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Derrien M, Van Baarlen P, Hooiveld G, et al. Modulation of Mucosal Immune Response, Tolerance, and Proliferation in Mice Colonized by the Mucin-Degrader Akkermansia muciniphila. Front Microbiol 2011;2:166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shin NR, Lee JC, Lee HY, et al. An increase in the Akkermansia spp. population induced by metformin treatment improves glucose homeostasis in diet-induced obese mice. Gut 2014;63:727–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Peng L, Li ZR, Green RS, et al. Butyrate enhances the intestinal barrier by facilitating tight junction assembly via activation of AMP-activated protein kinase in Caco-2 cell monolayers. J Nutr 2009;139:1619–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hajjar AM, Ernst RK, Tsai JH, et al. Human Toll-like receptor 4 recognizes host-specific LPS modifications. Nat Immunol 2002;3:354–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Di Lorenzo F, De Castro C, Silipo A, et al. Lipopolysaccharide structures of Gram-negative populations in the Gut Microbiota and effects on host interactions. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wexler AG, Goodman AL. An insider’s perspective: Bacteroides as a window into the microbiome. Nat Microbiol 2017;2:17026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lopez-Siles M, Duncan SH, Garcia-Gil LJ, et al. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii: from microbiology to diagnostics and prognostics. ISME J 2017;11:841–852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wexler HM. Bacteroides: the good, the bad, and the nitty-gritty. Clin Microbiol Rev 2007;20:593–621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Meijers B, Farre R, Dejongh S, et al. Intestinal Barrier Function in Chronic Kidney Disease. Toxins (Basel) 2018;10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hendrikx T, Schnabl B. Antimicrobial proteins: intestinal guards to protect against liver disease. J Gastroenterol 2019;54:209–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bajaj JS, Heuman DM, Hylemon PB, et al. Altered profile of human gut microbiome is associated with cirrhosis and its complications. J Hepatol 2014;60:940–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Coyte KZ, Schluter J, Foster KR. The ecology of the microbiome: Networks, competition, and stability. Science 2015;350:663–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.WHO. Global status report on alcohol and health 2018. 2018.

- 65.Schwartz JM, Reinus JF. Prevalence and natural history of alcoholic liver disease. Clin Liver Dis 2012;16:659–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Patel S, Behara R, Swanson GR, et al. Alcohol and the Intestine. Biomolecules 2015;5:2573–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bala S, Marcos M, Gattu A, et al. Acute binge drinking increases serum endotoxin and bacterial DNA levels in healthy individuals. PLoS One 2014;9:e96864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Prytz H, Bjorneboe M, Orskov F, et al. Antibodies to Escherichia coli in alcoholic and non-alcoholic patients with cirrhosis of the liver or fatty liver. Scand J Gastroenterol 1973;8:433–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Simjee AE, Hamilton-Miller JM, Thomas HC, et al. Antibodies to Escherichia coli in chronic liver diseases. Gut 1975;16:871–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cho YE, Yu LR, Abdelmegeed MA, et al. Apoptosis of enterocytes and nitration of junctional complex proteins promote alcohol-induced gut leakiness and liver injury. J Hepatol 2018;69:142–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chopyk DM, Kumar P, Raeman R, et al. Dysregulation of junctional adhesion molecule-A contributes to ethanol-induced barrier disruption in intestinal epithelial cell monolayers. Physiol Rep 2017;5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Elamin E, Masclee A, Dekker J, et al. Ethanol disrupts intestinal epithelial tight junction integrity through intracellular calcium-mediated Rho/ROCK activation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2014;306:G677–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ma TY, Nguyen D, Bui V, et al. Ethanol modulation of intestinal epithelial tight junction barrier. Am J Physiol 1999;276:G965–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chen P, Starkel P, Turner JR, et al. Dysbiosis-induced intestinal inflammation activates tumor necrosis factor receptor I and mediates alcoholic liver disease in mice. Hepatology 2015;61:883–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mir H, Meena AS, Chaudhry KK, et al. Occludin deficiency promotes ethanol-induced disruption of colonic epithelial junctions, gut barrier dysfunction and liver damage in mice. Biochim Biophys Acta 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rocco A, Compare D, Angrisani D, et al. Alcoholic disease: liver and beyond. World J Gastroenterol 2014;20:14652–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hartmann P, Chu H, Duan Y, et al. Gut microbiota in liver disease: Too much is harmful, nothing at all is not helpful either. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Llopis M, Cassard AM, Wrzosek L, et al. Intestinal microbiota contributes to individual susceptibility to alcoholic liver disease. Gut 2016;65:830–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bluemel S, Wang L, Kuelbs C, et al. Intestinal and hepatic microbiota changes associated with chronic ethanol administration in mice. Gut Microbes 2019:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yang AM, Inamine T, Hochrath K, et al. Intestinal fungi contribute to development of alcoholic liver disease. J Clin Invest 2017;127:2829–2841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Adachi Y, Moore LE, Bradford BU, et al. Antibiotics prevent liver injury in rats following long-term exposure to ethanol. Gastroenterology 1995;108:218–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chen P, Miyamoto Y, Mazagova M, et al. Microbiota Protects Mice Against Acute Alcohol-Induced Liver Injury. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2015;39:2313–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yan AW, Fouts DE, Brandl J, et al. Enteric dysbiosis associated with a mouse model of alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology 2011;53:96–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wang L, Fouts DE, Starkel P, et al. Intestinal REG3 Lectins Protect against Alcoholic Steatohepatitis by Reducing Mucosa-Associated Microbiota and Preventing Bacterial Translocation. Cell Host Microbe 2016;19:227–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hendrikx T, Duan Y, Wang Y, et al. Bacteria engineered to produce IL-22 in intestine induce expression of REG3G to reduce ethanol-induced liver disease in mice. Gut 2019;68:1504–1515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mutlu EA, Gillevet PM, Rangwala H, et al. Colonic microbiome is altered in alcoholism. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2012;302:G966–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lo WK, Chan WW. Proton pump inhibitor use and the risk of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: a meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013;11:483–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Fasullo M, Rau P, Liu DQ, et al. Proton pump inhibitors increase the severity of hepatic encephalopathy in cirrhotic patients. World J Hepatol 2019;11:522–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Dever JB, Sheikh MY. Review article: spontaneous bacterial peritonitis--bacteriology, diagnosis, treatment, risk factors and prevention. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015;41:1116–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Llorente C, Jepsen P, Inamine T, et al. Gastric acid suppression promotes alcoholic liver disease by inducing overgrowth of intestinal Enterococcus. Nat Commun 2017;8:837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Duan Y, Llorente C, Lang S, et al. Bacteriophage targeting of gut bacterium attenuates alcoholic liver disease. Nature 2019;575:505–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Safari Z, Gerard P. The links between the gut microbiome and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Cell Mol Life Sci 2019;76:1541–1558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Younossi ZM. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease - A global public health perspective. J Hepatol 2019;70:531–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Cui Y, Wang Q, Chang R, et al. Intestinal Barrier Function-Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Interactions and Possible Role of Gut Microbiota. J Agric Food Chem 2019;67:2754–2762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Turnbaugh PJ, Ley RE, Mahowald MA, et al. An obesity-associated gut microbiome with increased capacity for energy harvest. Nature 2006;444:1027–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Brun P, Castagliuolo I, Di Leo V, et al. Increased intestinal permeability in obese mice: new evidence in the pathogenesis of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2007;292:G518–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Luther J, Garber JJ, Khalili H, et al. Hepatic Injury in Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Contributes to Altered Intestinal Permeability. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;1:222–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Pierantonelli I, Rychlicki C, Agostinelli L, et al. Lack of NLRP3-inflammasome leads to gut-liver axis derangement, gut dysbiosis and a worsened phenotype in a mouse model of NAFLD. Sci Rep 2017;7:12200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Chen M, Hui S, Lang H, et al. SIRT3 Deficiency Promotes High-Fat Diet-Induced Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Correlation with Impaired Intestinal Permeability through Gut Microbial Dysbiosis. Mol Nutr Food Res 2019;63:e1800612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Yang SQ, Lin HZ, Lane MD, et al. Obesity increases sensitivity to endotoxin liver injury: implications for the pathogenesis of steatohepatitis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1997;94:2557–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Miele L, Valenza V, La Torre G, et al. Increased intestinal permeability and tight junction alterations in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2009;49:1877–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Rahman K, Desai C, Iyer SS, et al. Loss of Junctional Adhesion Molecule A Promotes Severe Steatohepatitis in Mice on a Diet High in Saturated Fat, Fructose, and Cholesterol. Gastroenterology 2016;151:733–746 e12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Saltzman ET, Palacios T, Thomsen M, et al. Intestinal Microbiome Shifts, Dysbiosis, Inflammation, and Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Front Microbiol 2018;9:61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Caussy C, Tripathi A, Humphrey G, et al. A gut microbiome signature for cirrhosis due to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat Commun 2019;10:1406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Wang B, Jiang X, Cao M, et al. Altered Fecal Microbiota Correlates with Liver Biochemistry in Nonobese Patients with Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Sci Rep 2016;6:32002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Zhou D, Pan Q, Xin FZ, et al. Sodium butyrate attenuates high-fat diet-induced steatohepatitis in mice by improving gut microbiota and gastrointestinal barrier. World J Gastroenterol 2017;23:60–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Cani PD, Amar J, Iglesias MA, et al. Metabolic endotoxemia initiates obesity and insulin resistance. Diabetes 2007;56:1761–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Zhu L, Baker SS, Gill C, et al. Characterization of gut microbiomes in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) patients: a connection between endogenous alcohol and NASH. Hepatology 2013;57:601–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Llorente C, Schnabl B. The gut microbiota and liver disease. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;1:275–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Cope K, Risby T, Diehl AM. Increased gastrointestinal ethanol production in obese mice: implications for fatty liver disease pathogenesis. Gastroenterology 2000;119:1340–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Hu H, Lin A, Kong M, et al. Intestinal microbiome and NAFLD: molecular insights and therapeutic perspectives. J Gastroenterol 2020;55:142–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Chavez-Talavera O, Tailleux A, Lefebvre P, et al. Bile Acid Control of Metabolism and Inflammation in Obesity, Type 2 Diabetes, Dyslipidemia, and Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Gastroenterology 2017;152:1679–1694 e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Iorga A, Dara L, Kaplowitz N. Drug-Induced Liver Injury: Cascade of Events Leading to Cell Death, Apoptosis or Necrosis. Int J Mol Sci 2017;18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Garcia-Cortes M, Ortega-Alonso A, Lucena MI, et al. Drug-induced liver injury: a safety review. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2018;17:795–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Bernal W, Wendon J. Acute liver failure. N Engl J Med 2013;369:2525–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Yoon E, Babar A, Choudhary M, et al. Acetaminophen-Induced Hepatotoxicity: a Comprehensive Update. J Clin Transl Hepatol 2016;4:131–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Krenkel O, Mossanen JC, Tacke F. Immune mechanisms in acetaminophen-induced acute liver failure. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr 2014;3:331–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Su GL, Gong KQ, Fan MH, et al. Lipopolysaccharide-binding protein modulates acetaminophen-induced liver injury in mice. Hepatology 2005;41:187–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Su GL, Hoesel LM, Bayliss J, et al. Lipopolysaccharide binding protein inhibitory peptide protects against acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2010;299:G1319–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Yang R, Zou X, Tenhunen J, et al. HMGB1 neutralization is associated with bacterial translocation during acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. BMC Gastroenterol 2014;14:66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Possamai LA, McPhail MJ, Quaglia A, et al. Character and temporal evolution of apoptosis in acetaminophen-induced acute liver failure*. Crit Care Med 2013;41:2543–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Possamai LA, McPhail MJ, Khamri W, et al. The role of intestinal microbiota in murine models of acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity. Liver Int 2015;35:764–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Gong S, Lan T, Zeng L, et al. Gut microbiota mediates diurnal variation of acetaminophen induced acute liver injury in mice. J Hepatol 2018;69:51–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Fricker ZP, Lichtenstein DR. Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis: A Concise Review of Diagnosis and Management. Dig Dis Sci 2019;64:632–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Liao L, Schneider KM, Galvez EJC, et al. Intestinal dysbiosis augments liver disease progression via NLRP3 in a murine model of primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gut 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Loftus EV Jr., Harewood GC, Loftus CG, et al. PSC-IBD: a unique form of inflammatory bowel disease associated with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gut 2005;54:91–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Nakamoto N, Sasaki N, Aoki R, et al. Gut pathobionts underlie intestinal barrier dysfunction and liver T helper 17 cell immune response in primary sclerosing cholangitis. Nat Microbiol 2019;4:492–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.O’Toole A, Alakkari A, Keegan D, et al. Primary sclerosing cholangitis and disease distribution in inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012;10:439–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Sasatomi K, Noguchi K, Sakisaka S, et al. Abnormal accumulation of endotoxin in biliary epithelial cells in primary biliary cirrhosis and primary sclerosing cholangitis. J Hepatol 1998;29:409–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Tornai T, Palyu E, Vitalis Z, et al. Gut barrier failure biomarkers are associated with poor disease outcome in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. World J Gastroenterol 2017;23:5412–5421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Dhillon AK, Kummen M, Troseid M, et al. Circulating markers of gut barrier function associated with disease severity in primary sclerosing cholangitis. Liver Int 2019;39:371–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Cai W, Ran Y, Li Y, et al. Intestinal microbiome and permeability in patients with autoimmune hepatitis. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2017;31:669–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Terjung B, Sohne J, Lechtenberg B, et al. p-ANCAs in autoimmune liver disorders recognise human beta-tubulin isotype 5 and cross-react with microbial protein FtsZ. Gut 2010;59:808–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Berg CP, Kannan TR, Klein R, et al. Mycoplasma antigens as a possible trigger for the induction of antimitochondrial antibodies in primary biliary cirrhosis. Liver Int 2009;29:797–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Liu R, Li X, Huang Z, et al. C/EBP homologous protein-induced loss of intestinal epithelial stemness contributes to bile duct ligation-induced cholestatic liver injury in mice. Hepatology 2018;67:1441–1457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Tedesco D, Thapa M, Chin CY, et al. Alterations in Intestinal Microbiota Lead to Production of Interleukin 17 by Intrahepatic gammadelta T-Cell Receptor-Positive Cells and Pathogenesis of Cholestatic Liver Disease. Gastroenterology 2018;154:2178–2193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Fuchs CD, Paumgartner G, Mlitz V, et al. Colesevelam attenuates cholestatic liver and bile duct injury in Mdr2(−/−) mice by modulating composition, signalling and excretion of faecal bile acids. Gut 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Jansen PL, Ghallab A, Vartak N, et al. The ascending pathophysiology of cholestatic liver disease. Hepatology 2017;65:722–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Oikonomou T, Papatheodoridis GV, Samarkos M, et al. Clinical impact of microbiome in patients with decompensated cirrhosis. World J Gastroenterol 2018;24:3813–3820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Chander Roland B, Garcia-Tsao G, Ciarleglio MM, et al. Decompensated cirrhotics have slower intestinal transit times as compared with compensated cirrhotics and healthy controls. J Clin Gastroenterol 2013;47:888–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Chen Y, Yang F, Lu H, et al. Characterization of fecal microbial communities in patients with liver cirrhosis. Hepatology 2011;54:562–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Qin N, Yang F, Li A, et al. Alterations of the human gut microbiome in liver cirrhosis. Nature 2014;513:59–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]