Abstract

Background

Corynebacterium glutamicum thrives under oxidative stress caused by the inevitably extreme environment during fermentation as it harbors antioxidative stress genes. Antioxidant genes are controlled by pathway-specific sensors that act in response to growth conditions. Although many families of oxidation-sensing regulators in C. glutamicum have been well described, members of the xenobiotic-response element (XRE) family, involved in oxidative stress, remain elusive.

Results

In this study, we report a novel redox-sensitive member of the XER family, MsrR (multiple stress resistance regulator). MsrR is encoded as part of the msrR-3-mst (3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase) operon; msrR-3-mst is divergent from multidrug efflux protein MFS. MsrR was demonstrated to bind to the intergenic region between msrR-3-mst and mfs. This binding was prevented by an MsrR oxidation-mediated increase in MsrR dimerization. MsrR was shown to use Cys62 oxidation to sense oxidative stress, resulting in its dissociation from the promoter. Elevated expression of msrR-3-mst and mfs was observed under stress. Furthermore, a ΔmsrR mutant strain displayed significantly enhanced growth, while the growth of strains lacking either 3-mst or mfs was significantly inhibited under stress.

Conclusion

This report is the first to demonstrate the critical role of MsrR-3-MST-MFS in bacterial stress resistance.

Keywords: Oxidative stress, MsrR, Transcription regulation, Corynebacterium glutamicum

Background

Reactive oxygen species (ROS), including hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), superoxide anion (O2·−), hydroxyl radical (·OH), hydroperoxy radical (HO2·), singlet oxygen (1O2), and organic hydroperoxides (OHPs), are inevitable byproducts of aerobic respiration that are also generated under environmental stress by perturbation of the electron transfer chain [1]. ROS can react with the membrane, free fatty acids, and other macromolecules via free radical chain reactions, resulting in the production of a wide spectrum of detrimental carbonyl-containing compounds [2, 3]. The excessive production of ROS is harmful to living systems as it induces oxidative stress and causes subsequent cellular damage to molecules such as DNA, proteins, and lipids [4]. To ensure survival in a hostile environment, versatile resistance defense mechanisms, such as eliminating ROS, deterring the transformation of ROS into more toxic compounds and repairing damaged biomacromolecules, have been developed [5–7]. Low-molecular-weight (LMW) thiols and multiple antioxidant enzymes play crucial roles in defense mechanisms. When bacteria encounter oxidative stress due to a specific ROS, they modulate the expression of the corresponding resistance enzymes [8, 9]. To achieve this, bacteria use pathway-specific transcription factors that act in response to specific ROS and coordinate the appropriate oxidative stress-associated genetic response. Thus, the regulation of antioxidant expression is an important issue. The constant sensing of ROS can be mediated by oxidation of one or more thiolates in regulators [10].

Many of the best characterized bacterial sensors of ROS, such as the LysR (DNA-binding transcriptional dual-lysine regulator) family regulator OxyR (the thiol-based redox sensor for peroxides) [11, 12], zinc-associated extracytoplasmic function (ECF)-type sigma factor H (SigH) [13, 14], the ferric uptake regulator (Fur) family regulator PerR (a peroxide regulon repressor) [15], the MarR (multiple antibiotics resistance regulators) family regulator OhrR (an organic hydroperoxide resistance regulator) [16], the TetR (a tetracycline repressor protein) family regulator NemR (a N-ethylmaleimide regulator) [17], and the AraC (cytosine β-d-arabinofuranoside) family regulator RclR (a regulator of hypochlorous acid (HOCl)-specific resistance) [18], have been shown to contribute to or to modulate antioxidant gene expression [11–18]. These sensors specifically sense ROS via a thiol-based mechanism [11–18]. Upon exposure to oxidative stress, these regulators are activated or inhibited by morphological changes caused by cysteine oxidation, after which they are released from or bind the promoters of target genes, leading to the upregulation of these target genes. Interestingly, more recently, Hu et al. found that the xenobiotic response element (XRE) family transcriptional regulator SrtR (stress response transcriptional regulator) in Streptococcus suis is also involved in oxidative stress tolerance, the only report of stress resistance in a member of the XRE family thus far [19]. Unfortunately, its exact molecular mechanism related to oxidant sensing, its target genes, and its interplay with other regulators have not yet been described. XREs, which are widely distributed in living organisms, control the expression of virulence factors, antibiotic synthesis and resistance genes, and stress response genes [20]. Although the XRE family is the second most common family of regulators in bacteria, XRE family members have been reported in only a limited number of bacteria, such as Staphylococcus aureus [21], Rhizobium etli [22], S. suis [19], and Chloroflexus aurantiacus [23]. Until now, research on XREs has mainly focused on XREs in eukaryotes. In eukaryotes, the regulatory mechanism of XREs is well known but different from that of ROS-sensing regulators; many xenobiotics acting as inducers, such as oxidants, heavy metals, antibiotics, and toxins, bind aromatic hydrocarbon (Ah) receptors in the cytoplasm to form an Ah receptor-ligand complex, which then interacts with XREs in the nucleus, finally stimulating the transcription of the target genes [24, 25]. However, the functions of XREs in eukaryotes were not reported to be related to oxidative stress or other tolerance to other stresses. Thus, much research about XREs remains to be carried out, especially on the functions and mechanisms of XREs related to oxidative stress and tolerance to other stresses in bacteria.

Corynebacterium glutamicum, a nonpathogenic, GC-rich, and gram-positive bacterium, is not only an important industrial strain for the production of amino acids, nucleic acids, organic acids, alcohols, and biopolymers but also a key model organism for the study of the evolution of pathogens [26]. During the fermentation process, C. glutamicum inevitably encounters a series of unfavorable conditions [27, 28]. However, C. glutamicum thrives under the adverse stresses of the fermentation process using several antioxidant defenses, such as millimolar concentrations of mycothiol (MSH) and antioxidant enzymes [29–32]. Although many thiol-based redox-sensing regulators from different transcription factor families, including LysR (OxyR), MarR [RosR (regulator of oxidative stress response)/OhsR (organic hydroperoxides stress regulator)/CosR (C. glutamicum oxidant-sensing regulator)/QorR (quinone oxidoreductase regulator)], TetR [OsrR(Oxidative stress response regulator)], ArsR [CyeR (Corynebacterium yellow enzyme regulator)], and SigH, have been well studied [14, 29–31, 33–35], whether the XRE proteins of C. glutamicum play a role in protecting against oxidative stress by directly regulating antioxidant genes remains obscure. The putative XRE family transcriptional regulator NCgl2679, named MsrR (multiple stress resistance regulator) due to the results of this study, is not only located immediately downstream and in the opposite direction of the multidrug efflux protein NCgl2680 (MFS) but also organized in an operon with 3-Mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase (NCgl2678, 3-MST) and the putative protein NCgl2677. This genetic organization allowed us to investigate the function of C. glutamicum MsrR in response to environmental stresses. In the present study, MsrR was found to directly control expression of the msrR-3-mst-ncgl2677 operon and the mfs gene as a thiol-based redox-sensing transcriptional repressor. The expression of msrR, 3-mst and mfs was induced by oxidative stress. MsrR contains only one cysteine residue at position 62 (Cys62). Upon oxidative stress induced by various xenobiotics, MsrR underwent dimerization and lost its DNA-binding activity through the formation of an intermolecular disulfide bond between the Cys62 residue of each subunit. These findings suggest that MsrR is a redox-sensing transcriptional regulator involved in the oxidative stress response of C. glutamicum by its regulation of 3-mst and mfs expression.

Methods

Strains and culture conditions

Bacterial strains and plasmids used this study were listed in Additional file 1: Table S1. Escherichia coli and C. glutamicum were cultured in Luria–Bertani (LB) broth aerobically or on LB agar plates as previously reported [36]. ΔmsrR, Δ3-mst and Δmfs in-frame deletion mutants were produced as described [37]. Briefly, the pK18mobsacB-ΔmsrR plasmid was transformed into C. glutamicum wild type (WT) through electroporation to carry out single crossover. The transconjugants were selected on LB agar medium containing 40 µg/ml nalidixic acid and 25 µg/ml kanamycin. Counter-selection for markerless in-frame deletion was performed on LB agar plates with 40 µg/ml nalidixic acid and 20% sucrose [37]. Strains growing on this plate were tested for kanamycin sensitivity (KANS) by parallel picking on 40 µg/ml nalidixic acid-containing LB plate supplemented with either 25 µg/ml kanamycin or 20% sucrose. Sucrose-resistant and kanamycin-sensitive strains were tested for deletion by PCR using the DMsrR-F1/DMsrR-R2 primer pair (Additional file 1: Table S2) and confirmed by DNA sequencing. The Δ3-mst and Δmfs in-frame deletion mutants were constructed in similar manners by plasmid pK18mobsacB-Δ3-mst and pK18mobsacB-Δmfs using primers listed in Additional file 1: Table S2. For performing sensitivity assays, bacteria growth in LB broth containing 0.3 mM cumene hydroperoxide (CHP), 0.9 mM menadione (MEN), 45 mM H2O2, 0.4 mM HOCl, 1.5 mM tert-butyl hydroperoxide (t-BHP), 5 mM iodoacetamide (IAM), 0.1 µg/ml gentamicin, or 17 µM cadmium chloride (CdCl2) was measured according to Helbig et al. [38].

Cloning, expression, and recombinant protein purification

The genes encoding C. glutamicum MsrR (NCgl2679), 3-MST (NCgl2678), MFS (NCgl2680) were amplified using primers listed in Additional file 1: Table S2 by PCR. The amplified DNA fragments were digested and subcloned into similar digested pET28a, pXMJ19, or pXMJ19-His6 vectors, obtaining pET28a-msrR, pXMJ19-msrR, pXMJ19-His6-msrR, pXMJ19-3-mst, and pXMJ19-mfs, respectively.

The plasmids pK18mobsacB-ΔmsrR, pK18mobsacB-Δ3-mst, and pK18mobsacB-Δmfs were constructed by overlap-PCR [39]. Briefly, primer pairs DMsrR-F1/DMsrR-R1 and DMsrR-F2/DMsrR-R2 listed in Additional file 1: Table S2 were used to amplify the 806-bp upstream fragment and the 820-bp downstream fragment of msrR, respectively. The primer pair DMsrR-F1/DMsrR-R2 was used to fuse the upstream and downstream fragments together by overlap extension PCR [39]. The obtained PCR products were digested with EcoRI and BamHI, and cloned into similar digested pK18mobsacB to produce pK18mobsacB-ΔmsrR. The knock-out plasmid pK18mobsacB-Δ3-mst and pK18mobsacB-Δmfs were constructed in a similar manner by using the primers listed in Additional file 1: Table S2.

The lacZY fusion reporter vectors pK18mobsacB-PmsrR::lacZY and pK18mobsacB-Pmfs::lacZY were obtained by fusion of the msrR or mfs promoter to the lacZY reporter gene via overlap-PCR [40]. Firstly, the primers PmsrR-F/PmsrR-R and lacZY-F/lacZY-R were used in the first round of PCR to amplify the 232-bp msrR promoter DNA fragments (corresponding to nucleotides + 12 to – 220 relative to the translational start codon (ATG) of msrR gene) and the lacZY DNA fragments, respectively. Secondly, PmsrR-F/lacZY-R as primers and the first round PCR products as templates were used to perform the second round of PCR, and the resulting fragments were digested with SmaI and PstI, and inserted into similar digested pK18mobsacB to obtain the pK18mobsacB-PmsrR::lacZY fusion construct [29]. A similar process was used to construct pK18mobsacB-Pmfs::lacZY. Briefly, the 235-bp mfs promoter DNA fragments (corresponding to nucleotides + 15 to − 220 relative to the translational start codon (ATG) of mfs gene) was amplified with the primers listed in Additional file 1: Table S2 and fused to the lacZY reporter genes. The resulting Pmfs::lacZY was inserted into similar digested pK18mobsacB.

For obtaining pK18mobsacB-PmsrRM::lacZY, 232-bp msrR promoter DNA containing mutagenesis sequence of the predicted MsrR binding site (PmsrRM) was first directly synthesized by Shanghai Biotechnology Co., Ltd.. Start and stop sites of PmsrRM were the same as those of PmsrR in PmsrR::lacZY. Then, the resulting 232-bp PmsrRM was fused to a lacZY reporter gene. Finally, PmsrRM::lacZY was inserted into similar digested pK18mobsacB. A similar process was used to construct pK18mobsacB-PmfsM::lacZY. Briefly, 235-bp mfs promoter DNA containing a mutagenesis sequence of the predicted MsrR binding site (PmfsM) was directly synthesized and its start and stop sites were the same as those of Pmfs in Pmfs::lacZY. Then, 235-bp PmfsM was fused to a lacZY reporter gene to obtain PmfsM::lacZY. Finally, PmfsM::lacZY was inserted into similar digested pK18mobsacB.

For complementation or overexpression in C. glutamicum strains, pXMJ19 or pXMJ19-His6 derivatives were transformed into the corresponding C. glutamicum strains by electroporation, and the transformants were selected on 10 µg/ml chloramphenicol and 40 µg/ml nalidixic acid-containing LB agar plates. The transformant’s expression was induced by adding 0.5 mM isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) into medium [40].

To make the cysteine residue at position 62 of MsrR into a serine residue (MsrR:C62S), site-directed mutagenesis was made by two rounds of PCR [41]. In brief, in the first round of PCR, primer pairs DMsrR-F1/MsrR-C62S-R and MsrR-C62S-F/DMsrR-R2 were used to amplify segments 1 and 2, respectively. The second round of PCR was performed by using CMsrR-F/CMsrR-R or OMsrR-F/OMsrR-R as primers and fragment 1 and fragment 2 as templates to produce the msrR:C62S DNA segment. The msrR:C62S segment was digested and subcloned into digested pET28a, pXMJ19 or pXMJ19-His6 plasmid, obtaining the corresponding plasmids. To express and purify His6-tagged recombinant proteins, the pET28a derivatives were transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3). Recombinant proteins were purified according to previously described method [40]. Primers used in this study were listed in Additional file 1: Table S2.

The fidelity of all constructs was confirmed by DNA sequencing (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China).

Construction of chromosomal fusion reporter strains and β-galactosidase assay

The lacZY fusion reporter plasmids pK18mobsacB-PmsrR::lacZY, pK18mobsacB-Pmfs::lacZY, pK18mobsacB-PmsrRM::lacZY, and pK18mobsacB-PmfsM::lacZY were transformed into C. glutamicum parental strain containing the high copy number of empty plasmid pXMJ19 (the strains were named WT), ∆msrR (strains lacking msrR gene containing empty pXMJ19) and ∆msrR+ (ΔmsrR was complemented with pXMJ19 plasmids carrying the wild-type msrR gene) by electroporation, respectively. The introduced pK18mobsacB derivatives were integrated into the chromosome using fusion promoter regions homologous to the genome of C. glutamicum by single crossover and then the chromosomal WT(PmsrR::lacZY), ∆msrR(PmsrR::lacZY), ∆msrR+(PmsrR::lacZY), WT(PmsrRM::lacZY), ∆msrR(PmsrRM::lacZY), ∆msrR+(PmsrRM::lacZY), WT(Pmfs::lacZY), ∆msrR(Pmfs::lacZY), ∆msrR+(Pmfs::lacZY), WT(PmfsM::lacZY), ∆msrR(PmfsM::lacZY), and ∆msrR+(PmfsM::lacZY) fusion reporter strains were selected by plating on LB agar plates containing 40 µg/ml−1 nalidixic acid, 25 µg/ml−1 kanamycin, and 10 µg/ml−1 chloramphenicol [37]. The resulting strains were grown in LB medium to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.6–0.7 and then treated with different reagents of various concentrations at 30 °C for 30 min. β-galactosidase activities were assayed with o-Nitrophenyl-β-d-Galactopyranoside (ONPG) as the substrate [39]. The standard assay for quantitating the amount of β-galactosidase activity in cells, originally described by Miller for assay of bacterial cultures, involves spectrophotometric measurement of the formation of the yellow chromophore ο-nitrophenol (ONP) as the hydrolytic product of the action of β-galactosidase on the colorless substrate ο-Nitrophenyl β-d-galactopyranoside (ONPG) [42]. All β-galactosidase experiments were performed with at least three independent biological replicates.

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analysis

Total RNA was isolated from exponentially growing WT, ΔmsrR and ΔmsrR+ strains exposed to different toxic agents of indicated concentrations for 30 min using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) along with the DNase I Kit (Sigma-Aldrich, Taufkirchen, Germany). Purified RNA was reverse-transcribed with random 9-mer primers and MLV reverse transcriptase (TaKaRa, Dalian, China). Quantitative RT-PCR analysis (7500 Fast Real-Time PCR; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) was performed as described previously [40]. The primers used were listed in Additional file 1: Table S2. To obtain standardization of results, the relative abundance of 16S rRNA was used as the internal standard.

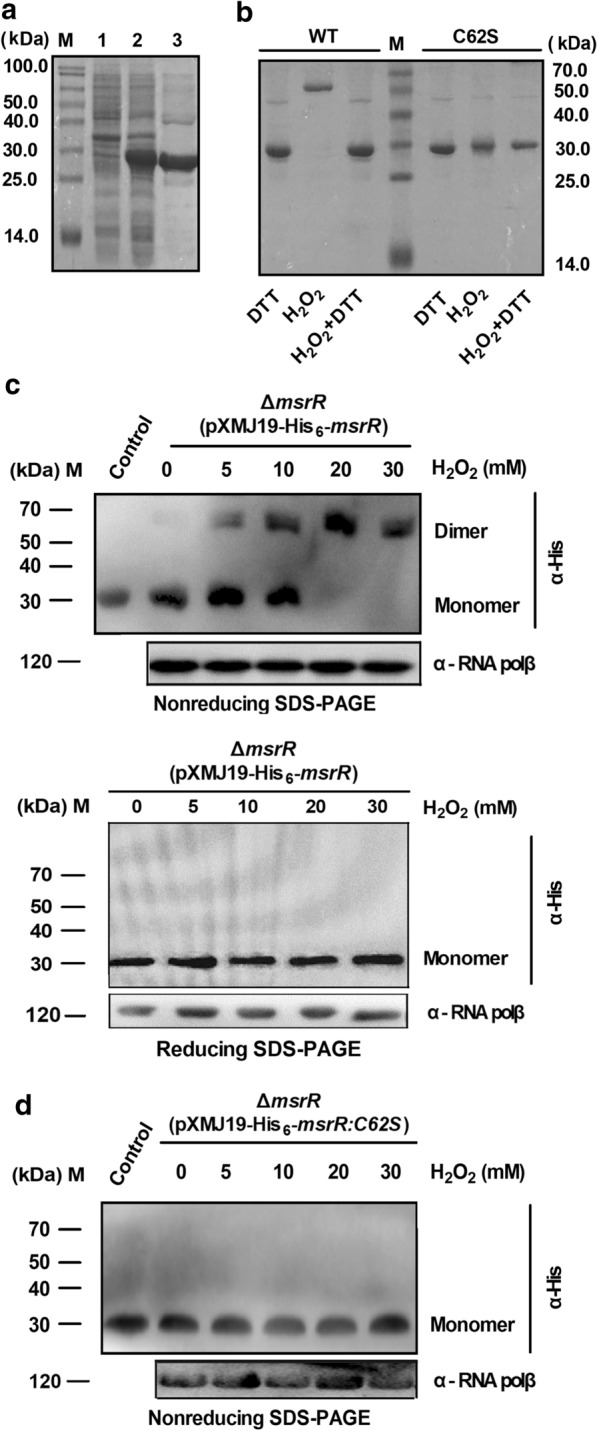

H2O2-dependent structural change of MsrR in vivo

The H2O2-dependent structural change of MsrR and its variant in vivo were determined by a previously reported method [39]. ΔmsrR (pXMJ19-His6-msrR) and ΔmsrR (pXMJ19-His6-msrR:C62S) strains were cultured in LB containing 0.5 mM IPTG, 10 µg/ml chloramphenicol, and 40 µg/ml nalidixic acid at 30 °C. Cells were grown to mid-exponential phase and split into 100 ml aliquots for H2O2 treatment (0–30 mM, 60 min). The treated samples were harvested immediately by centrifugation, broken through ultrasound on ice, and then crude cell lysates were centrifuged. Obtained supernatants were subjected to nonreducing sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) or reducing SDS-PAGE, and the structural properties of MsrR and its variant were visualized by immunoblotting using the anti-His antibody.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA)

EMSA was performed using the method of Si et al. [30]. Briefly, a 162-bp msrR promoter sequence [PmsrR; corresponding to nucleotides − 154 to + 8 relative to the translational start codon (GTG) of the cssR ORF] containing the predicted MsrR binding site was amplified using primer pair EMsrR-F/EMsrR-R (Additional file 1: Table S2). The binding reaction mixture (20 μl) contained 10 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.4), 5 mM MgCl2, 50 mM KCl, 5% glycerol, 0.1% Nonidet P 40 (NP40), 1 μg poly(dI:dC), 0–60 nM of MsrR, and 40 ng PmsrR. 162-bp DNA fragments amplified from MsrR ORF (40 ng) instead of PmsrR were used as a negative control. A 162-bp EMSA promoter DNA containing the mutated sequence of the predicted MsrR-binding site and having the same start and stop sites as PmsrR (PmsrRM) was directly synthesized by Shanghai Biotechnology Co., Ltd.. After the binding reaction mixture was incubated at room temperature for 30 min, the mixture was subjected to electrophoresis on 8% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel made with 10 mM Tris buffer containing 50 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2 and 10% glycero1 in 0.5× TBE electrophoresis buffer [50 mM Tris, 41.5 mM borate (pH 8.0), 10 mM Na2EDTA.H2O], and stained either with a 10,000-fold diluted Synergy Brand (SYBR) Gold nucleic acid staining solution (Molecular Probes) or GelRed™ and photographed. The DNA bands were visualized with UV light at 254 nm.

The reversibility of the loss of binding due to oxidation was tested as follows. H2O2 was added to MsrR solution to a final concentration of 10 mM, immediately aliquots were taken and incubated with 40 ng PmsrR for EMSA. In the next step, dithiothreitol (DTT) was added to the H2O2-treated MsrR solutions to a final concentration of 50 mM, and again aliquots were taken for EMSA. All aliquots were incubated in binding buffer with 40 ng PmsrR for 30 min at room temperature and separated on an 8% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel and the gel was stained using SYBR Gold nucleic acid staining solution.

For the determination of apparent KD values, increasing concentrations of the MsrR (0–100 nM) were incubated for 30 min at room temperature with 40 ng PmsrR. The samples were applied onto an 8% native polyacrylamide gel and separated at 180 V for 1 h on ice. The gels stained with GelRed™ and photographed were quantified using ImageQuant software (GE Healthcare), and the percentage of shifted DNA was calculated. These values were plotted against the MsrR concentration in log10 scale, and a sigmoidal fit was performed using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software, San Diego California USA), considering the error bars as well as 0 and 100% shifted DNA as asymptotes, the turning point of the curve was defined as the apparent KD value. All determinations were performed in triplicate.

Western blot analysis

Western blot analysis was conducted as previously described [29]. The cytosolic RNA polymerase β (RNA polβ) was used as a loading control as in our previous study [29].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses of survival rate, transcription level and protein level were determined with paired two-tailed Student’s t-test. GraphPad Prism Software was used to carry out statistical analyses (GraphPad Software, San Diego California USA).

Results and discussion

The ΔmsrR C. glutamicum strain showed reduced sensitivity to challenge by oxidants, antibiotics, heavy metals, and alkylating agents

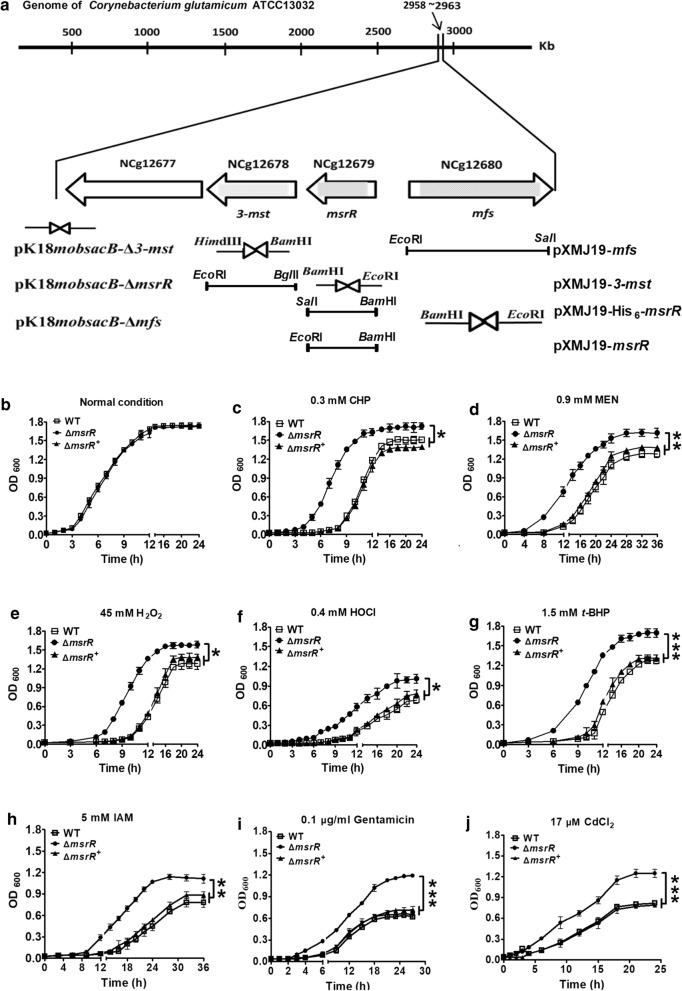

The 723-bp C. glutamicum ncgl2679 gene is located from bp 2,960,466 to 2,961,188 (Fig. 1a, upper panel) and encodes a hypothetical transcriptional regulator consisting of 240 amino acid residues with a molecular mass of 26.2 kDa. The putative protein product, which contains a helix-turn-helix motif, shares similarity with XRE (xenobiotic response element) family transcription factors from Corynebacterium crudilactis, Corynebacterium efficiens, Corynebacterium callunae, Corynebacterium epidermidicanis, and Corynebacterium minutissimum (80%, 68%, 64%, 42%, and 40% amino acid sequence identity, respectively) (Additional file 1: Figure S1). A recent study showed that the transcriptional regulator SrtR, an XRE family member, is involved in oxidative and high temperature stress tolerance [19]. This finding prompted us to examine whether NCgl2679 plays a role in protecting the soil bacterium C. glutamicum from various stresses. The functions of NCgl2679 were identified by gene disruption and complementation (Fig. 1a, lower panel). Growth analysis of different C. glutamicum strains on LB medium in the absence of stress revealed that the wild-type C. glutamicum strain (WT, C. glutamicum transformed with the empty plasmid pXMJ19), the Δncgl2679 mutant strain (the ncgl2679 deletion mutant expressing pXMJ19) and the Δncgl2679+ strain (the ncgl2679 deletion mutant expressing the wild-type ncgl2679 gene in the shuttle vector pXMJ19) showed almost the same growth rates (Fig. 1b). However, the growth of the WT strain in LB medium containing oxidants, alkylating agents, antibiotics, or heavy metals was markedly inhibited relative to the growth of the Δncgl2679 mutant strain (Fig. 1c–j). The complementary strain Δncgl2679+ exhibited a growth rate equivalent to that of the wild-type strain under various stresses, consistent with a previous evaluation of XREs under stress [19]. These results indicated that NCgl2679 is involved in the resistance of C. glutamicum to various stresses. Thus, we named NCgl2679 multiple stress response regulator (MsrR).

Fig. 1.

MsrR was required for optimal growth under various stress. a Physical map of the msrR-3-mst-ncgl2677 genetic cluster and mfs gene in Corynebacterium glutamicum (upper panel) and construction of plasmids for gene disruption (pK18mobsacB derivatives) and complementation (pXMJ19 derivatives) (lower panel). Open reading frames (ORFs) were marked by open arrows, and the deleted regions were in gray. The restriction sites were indicated. msrR, 3-mst, and mfs represented ncgl2679, ncgl2678, and ncgl2680 genes, encoding multiple stress resistance regulator, 3-Mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase, and a major facilitator superfamily protein, respectively. b Growth of the indicated three strains in LB broth without stress was used as control. c–j Growth of indicated strains in LB broth with 0.3 mM cumene hydroperoxide (CHP), 0.9 mM menadione (MEN), 45 mM hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), 0.4 mM hypochlorous acid (HOCl), 1.5 mM tert-butyl hydroperoxide (t-BHP), 5 mM iodoacetamide (IAM), 0.1 µg/ml gentamicin, or 17 µM cadmium chloride (CdCl2), respectively. Data show the averages of three independent experiments, and error bars indicated the SDs from three independent experiments. ***P ≤ 0.001; **P ≤ 0.01; *P ≤ 0.05

MsrR negatively regulates expression of the divergently oriented genes mfs and msrR-3-mst

In the C. glutamicum genome, msrR (ncgl2679) is organized in a putative operon with ncgl2678 and ncgl2677, which were shown to be co-transcribed by reverse transcription PCR (Additional file 1: Figure S2). Further downstream from ncgl2679 is the ncgl2680 gene, which was annotated as the multidrug efflux protein MFS. The mfs and msrR genes are oriented in opposite directions. By bioinformatics molecular analysis, two putative overlapping and divergent promoter sequences in the intergenic region between the start codons of mfs and msrR were found (Additional file 1: Figure S3), and one of these promoter sequences was found to be located upstream of the msrR gene. Neighboring mfs is a putative − 10 and − 35 promoter sequence, which was found to be the mfs promoter.

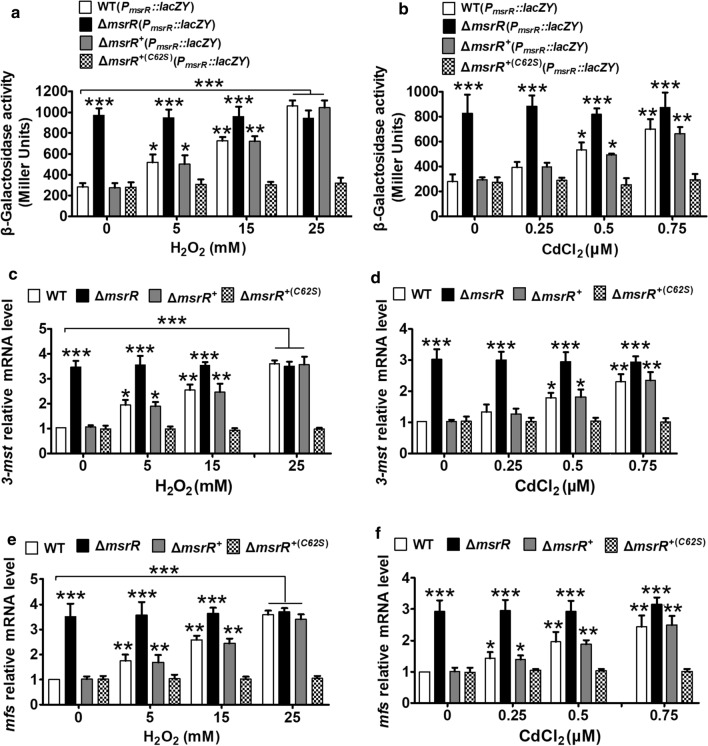

On the basis of bioinformatics analysis, a putative MsrR-binding site in the putative overlapping, divergent promoters of the msrR-ncgl2678 locus and mfs gene was found (Additional file 1: Figure S3). Thus, we speculated that MsrR negatively regulates the msrR-ncgl2678-ncgl2677 locus and represses transcription of the adjacent, oppositely oriented mfs gene. To verify this speculation, msrR, ncgl2678 and mfs transcription levels in the WT, ΔmsrR mutant, and ΔmsrR+ strains were analyzed by qRT-PCR and determination of the lacZY activity of the chromosomal promoter fusion reporter. Notably, to study the expression of msrR in the ΔmsrR mutant strain by qRT-PCR, a 104-bp msrR transcript (corresponding to nucleotides + 1 to + 104 relative to the translational start codon (GTG) of the msrR gene) was amplified from the remaining msrR ORF in the ΔmsrR mutant strain with the primers QmsrR-F and QmsrR-R (Additional file 1: Figure S4). As expected, msrR, ncgl2678 and mfs transcription levels in the ΔmsrR mutant strain were obviously higher than those in the WT and ΔmsrR+ strains (Fig. 2 and Additional file 1: Figure S5). These results indicated that MsrR negatively controls the expression of NCgl2678, MFS, and its structural gene.

Fig. 2.

Negative regulation of msrR-3-mst and mfs expressions by MsrR. a, b β-galactosidase analysis of the msrR promoter activity was performed using the transcriptional PmsrR::lacZY chromosomal fusion reporter expressed in indicated strains exposed to H2O2 and CdCl2. c–f qRT-PCR assay was performed to analyze the expression of 3-mst and mfs in indicated strains exposed to H2O2 and CdCl2. The mRNA levels were presented relative to the value obtained from WT cells without treatment. Relative transcript levels of WT strains without stress treatment were set at a value of 1.0. Data show the averages of three independent experiments, and error bars indicated the SDs from three independent experiments. ***P ≤ 0.001; **P ≤ 0.01; *P ≤ 0.05

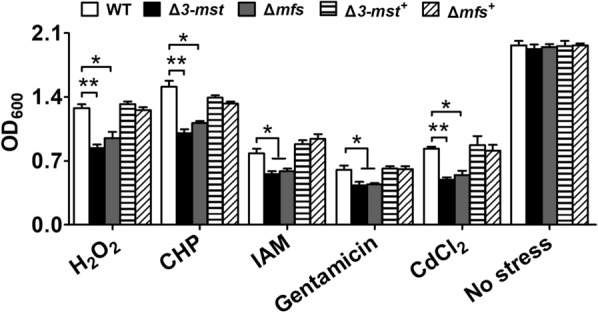

ncgl2678, which was annotated as 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase (3-MST), is mainly responsible for hydrogen sulfide (H2S) production [43]. Previous studies found that H2S made by nonsulfur bacteria alleviates oxidative stress imposed by diverse stresses through increasing levels of intracellular antioxidants, including glutathione (GSH); antioxidant enzymes; and glutamate uptake [44, 45]. This finding suggests that the absence of 3-mst probably cause the decrease of H2S content, which in turn reduction of the antioxidant capacity of C. glutamicum strains. In addition, many reports have revealed that cells expressing MFS can excrete various poisons [46, 47], suggesting that C. glutamicum MFS is also important for resistance to diverse stresses. Thus, the functions of 3-mst and mfs were identified by gene disruption and complementation with C. glutamicum (Fig. 1a, lower panel). As shown in Fig. 3, while deletion of 3-mst or mfs did not affect bacterial growth under normal conditions, compared to the WT strain, the Δ3-mst and Δmfs mutant strains devoid of 3-mst or mfs, respectively, exhibited obvious growth inhibition under challenge with various diverse stresses. The growth of 3-mst or mfs deletion mutant strains under diverse stresses was restored to a level similar to that of the WT strain by transformation with the plasmid-encoded wild type 3-mst or mfs gene (Δ3-mst+or Δmfs+), in agreement with the results of Li et al. regarding MST [48] (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

3-MST and MFS were involved in oxidative stress resistance. Effect of deletion of 3-mst and mfs genes on various stress resistance. The growth (OD600) of the indicated strains after over 24 h at 30 °C in LB medium containing various stress was recorded. Data show the averages of three independent experiments, and error bars indicated the SDs from three independent experiments. **P ≤ 0.01; *P ≤ 0.05

Expression of msrR, 3-mst and mfs was induced by oxidative stress via MsrR

Previous studies revealed that the transcriptional activation of target genes controlled by XREs is mediated by xenobiotics, which act as inducers [49, 50]. The mechanism by which various xenobiotics act as inducers and affect the conformation of XREs is a key feature for induction activity. Thus, these studies, combined with the above finding that MsrR is involved in tolerance to various stresses, led us to investigate whether MsrR participates in the induction of its own gene and the 3-mst and mfs genes by xenobiotics. For simplicity, we used H2O2 and CdCl2 as inducers in the following experiments. As shown in Fig. 2a and Additional file 1: Figure S5c, in the absence of H2O2, the ΔmsrR strain had significantly higher msrR and mfs expression levels than the WT and ΔmsrR+ strains, whereas the lacZY activities of msrR and mfs in the WT strain exposed to H2O2 were obviously higher than those in the untreated-H2O2 WT strain. The addition of H2O2 did not change the lacZY activities of msrR or mfs in the ΔmsrR strain, which were maintained at the same levels observed in the ΔmsrR strain without H2O2 treatment. Moreover, analysis of the lacZY activities showed a dose-dependent change in expression in the WT and ΔmsrR+ strains in response to H2O2 (Fig. 2a and Additional file 1: Figure S5c). A similar regulatory pattern of msrR, 3-mst or mfs by MsrR was also observed at the mRNA transcriptional level by qRT-PCR analysis (Fig. 2c, e and Additional file 1: Figure S5a). These results clearly demonstrated that msrR, 3-mst and mfs were upregulated in response to increasing H2O2 concentration, indicating that oxidation inhibited the DNA binding of MsrR, inducing the expression of its own gene and the 3-mst and mfs genes. This derepression of msrR, 3-mst and mfs transcription by CdCl2 was mediated via MsrR in a matter similar to that of H2O2 (Fig. 2b, d, f and Additional file 1: Figure S5b, d).

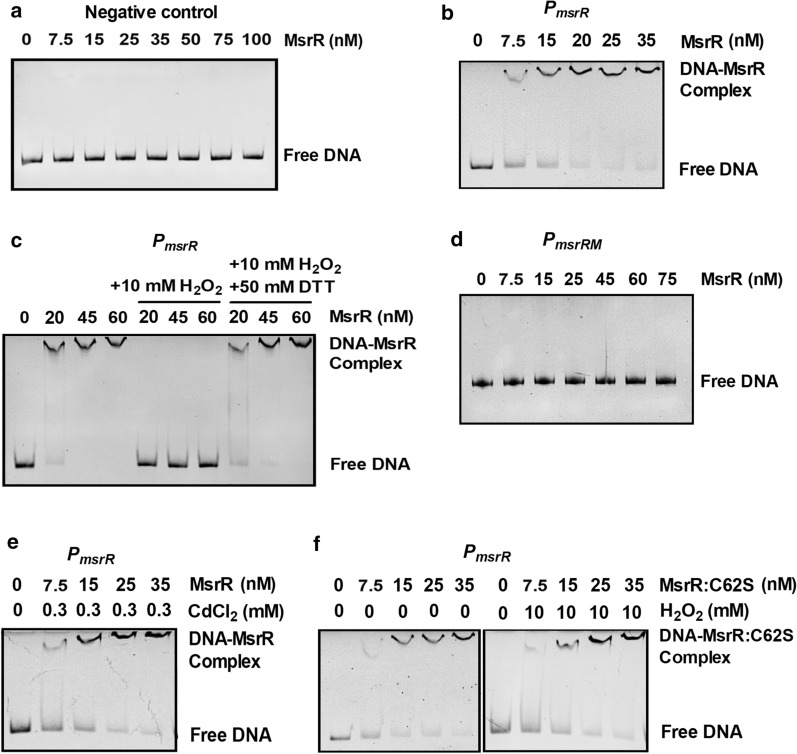

The ability of MsrR to bind the intergenic region between msrR and mfs was reversibly inhibited by ROS

To determine whether MsrR directly regulates its own transcription and the transcription of 3-MST and MFS, we examined the interaction between purified MsrR and a DNA promoter fragment in the intergenic region between msrR and mfs (named PmsrR) using EMSA. Incubation of PmsrR with His6-MsrR caused a clear delay in promoter DNA migration, and PmsrR migrated in a manner dependent on the concentration of His6-MsrR (Fig. 4b and Additional file 1: Figure S6b). The apparent KD value for PmsrR was about 17 nM MsrR (Additional file 1: Figure S7a), which is within the range found for other transcriptional regulators [33]. Moreover, this effect was specific because the combination of His6-MsrR and DNA fragments amplified from the MsrR ORF did not delay migration (Fig. 4a and Additional file 1: Figure S6a). However, the binding of His6-MsrR to PmsrR was prevented by the addition of 10 mM H2O2 (Fig. 4c and Additional file 1: Figure S6c). Importantly, the impaired DNA-binding activity of His6-MsrR by H2O2 could be restored via the addition of an excess of the reducing agent DTT (50 mM), indicating that the effects of oxidation and reduction on the DNA-binding activity of MsrR were reversible. (Fig. 4c and Additional file 1: Figure S6c). Mutations in the predicted MsrR-binding site (a 162-bp EMSA promoter DNA contained the mutated sequence of the predicted MsrR-binding site (PmsrRM), which had the same start and stop sites as PmsrR) (Additional file 1: Figure S3) disrupted the formation of DNA–protein complexes (Fig. 4d and Additional file 1: Figure S6d), and promoter DNA mutations in the predicted MsrR-binding site (a 232-bp DNA fragment contained the mutated sequence of the predicted MsrR-binding site for lacZY activity, which had the same start and stop sites as a 232-bp DNA fragment on PmsrR::lacZY; a 235-bp DNA fragment contained the mutated sequence of the predicted MsrR-binding site for lacZY activity, which had the same start and stop sites as a 235-bp DNA fragment on Pmfs::lacZY) caused extremely high PmsrRM::lacZY and PmfsM::lacZY activities in the WT and ΔmsrR+ strains, similar to those in the ΔmsrR mutant strain (Additional file 1: Figure S8), further indicating the recognition of DNA elements by MsrR. Interestingly, the addition of CdCl2 did not induce the dissociation of MsrR from PmsrR, inconsistent with the finding that derepression of msrR transcription by CdCl2 was mediated via MsrR in vivo (Fig. 4e and Additional file 1: Figure S6e). Combined with the discovery that expression of msrR was affected by H2O2 (Fig. 2), we speculated that this was related to CdCl2-mediated perturbation of the electron transfer chain, resulting in the formation of ROS in vivo, which inactivated XRE DNA-binding activity by the oxidation of cysteine residues [51, 52]. In fact, many studies have reported that the most potent xenobiotics, including oxidants, alkylating agents, antibiotics, and heavy metals, can generate ROS by redox cycling to produce oxidative stress inside bacteria [1, 51–56]. Thus, we speculated that MsrR does not directly sense ligands such as CdCl2, gentamicin, MEN and IAM.

Fig. 4.

Reversible inhibition of the DNA binding activity of MsrR by H2O2 and role of Cysteine residue. a The interaction between His6-MsrR and DNA fragments amplified from MsrR’s ORF. b The interaction between His6-MsrR and the promoter fragment in the intergenic region between msrR and mfs (named PmsrR). c Inhibition of the DNA binding activity of MsrR by H2O2 and reversal of the inhibition by DTT. MsrR was prepared in three different concentrations, and aliquots were taken for EMSAs (control). Then H2O2 was added to the binding reaction mixture to a final concentration of 10 mM, and aliquots were taken for EMSA. In the next step DTT (a final concentration of 50 mM) was added to 10 mM H2O2-containing binding reaction mixture, and aliquots were taken for EMSAs. All aliquots were incubated in binding buffer, pH 8.0, with 40 ng PmsrR and then separated on an 8% native polyacrylamide gel. d The interaction between His6-MsrR and the promoter mutating the predicted MsrR binding region (PmsrRM). e CdCl2 was added to the binding reaction mixture to a final concentration of 0.3 mM, and the interaction between His6-MsrR and PmsrR was performed. f The interaction between the mutated derivatives MsrR:C62S and PmsrR in the absence (left panel) or presence (right left) of 10 mM H2O2. Results were obtained in three independent experiments, and data show one representative experiment done in triplicate

Together, these results show that MsrR specifically recognized operators and then directly bound the msrR and mfs intergenic region in a sequence-specific manner. Upon exposure to oxidative stress, MsrR was inhibited by changes in conformation caused by ROS and released from the promoter, leading to the upregulation of target genes.

Oxidation promoted MsrR dimerization and inaction

Many redox-sensitive regulators, such as RosR, CosR, and OhsR, exist as homodimers via intersubunit disulfide bonds upon oxidation [29, 30, 33]. The amino acid sequence of MsrR shows that it contains one cysteine residue at position 62 (Additional file 1: Figure S1). Thus, we thought it might share a similar oxidation-sensing mechanism and that MsrR is oxidized to form an intersubunit disulfide-containing dimer. As shown in Fig. 5a, nonreducing SDS-PAGE showed that the native MsrR protein was monomeric with an apparent MW of approximately 30 kDa, corresponding well to the molecular mass of MsrR deduced from its amino acid sequence, while MsrR incubated with H2O2 migrated as a band of approximately 60 kDa, as judged by its behavior on 15% nonreducing SDS-PAGE, which corresponded to MsrR in its dimeric form. This dimeric formation was reversed by an excess of DTT (Fig. 5b). Moreover, dimers of H2O2-treated MsrR:C62S were not observed. These results suggested that the formation of dimeric MsrR occurs via a disulfide bond between MsrR proteins.

Fig. 5.

Redox response of MsrR in vitro and in vivo. a Nonreducing SDS-PAGE analysis of proteins expressed in E. coli containing pET28a-msrR plasmid. M, broad-range protein marker; lane 1, crude extract (5 μg) without IPTG induction; lane 2, crude extract (5 μg) with induction; lane 3 purified His6-MsrR protein. b Redox response of MsrR and its variant detected by nonreducing SDS-PAGE. 15 μM proteins treated with 50 mM DTT were further incubated with or without 50 μM H2O2, or 50 μM H2O2 and 50 mM DTT, and then samples were separated by 15% nonreducing SDS-PAGE. c, d Oxidative stress-dependent structural changes of relevant MsrR in vivo. Proteins extracted from cells exposed to different concentrations of H2O2 for 30 min were resolved on nonreducing or reducing SDS-PAGE, and analyzed with Western blotting by using the anti-His antibody. RNA polymerase β (RNA polβ) was used as a loading control. Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments, and data show one representative experiment done in triplicate

To further examine whether the formation of MsrR dimers can be induced under H2O2 treatment in vivo, we treated cells of the ΔmsrR (pXMJ19-His6-msrR) and ΔmsrR (pXMJ19-His6-msrR:C62S) strains with H2O2 at various concentrations and probed the forms of MsrR by immunoblotting with anti-His antibody after nonreducing SDS-PAGE separation (Fig. 5c, d; Additional file 1: Figure S9). Under normal conditions (no stress), MsrR in the ΔmsrR (pXMJ19-His6-msrR) strain existed as monomers, but upon exposure to different concentration of H2O2, the monomeric form changed into an intermolecular disulfide bond-containing dimeric form (Fig. 5c, upper panel and Additional file 1: Figure S9a, upper panel). The dimeric form completely disappeared on reducing SDS-PAGE, indicating that dimeric MsrR in vivo could be also reversed, which was consistent with the results in vitro (Fig. 5c, lower panel and Additional file 1: Figure S9a, lower panel). However, whether under H2O2 treatment or not, MsrR in the ΔmsrR (pXMJ19-His6-msrR:C62S) strain existed in a monomeric form (Fig. 5d and Additional file 1: Figure S9b). These results indicated that H2O2 causes a structural change in MsrR and that Cys62 is responsible for the morphological changes in MsrR observed under H2O2 treatment.

Inactivation of the DNA binding of MsrR by ROS is dependent on the oxidation state of Cys62

The reduction and oxidation of cysteine residues is involved in the control of ROS-sensing sensor activity [10]. It would be interesting to know whether Cys62 of MsrR plays an important role in the H2O2-sensing and transcription mechanisms of MsrR. Thus, the ability of the MsrR:C62S variant to suppress msrR, 3-mst and mfs expression in response to H2O2 was evaluated in the ΔmsrR strain using promoter lacZY activity and qRT-PCR analysis. Analysis of the transcriptional levels revealed that ΔmsrR+(C62S) (the ΔmsrR strain containing the pXMJ19-msrR:C62S plasmid) inhibited msrR, 3-mst and mfs expression under H2O2 treatment conditions to equal degrees, similar to that in the untreated-H2O2 WT strain, indicating that Cys62 plays a role in the dissociation of MsrR from the promoter under H2O2 treatment conditions (Fig. 2 and Additional file 1: Figure S5).

To further probe whether Cys62 is responsible for the observed dissociation of MsrR under oxidation, MsrR:C62S was used instead of WT MsrR to perform the EMSA experiment. As shown in Fig. 4f and Additional file 1: Figure S6f, in the presence or absence of 10 mM H2O2, MsrR:C62S still exhibited obviously retarded mobility. Although its affinity constant for PmsrR (KD = 23.08) was slightly high than that of MsrR, MsrR:C62S behaved high similarly to MsrR without H2O2 condition (Additional file 1: Figure S7b). These results mean that oxidation of Cys62 was important for inhibition of DNA binding by H2O2. The above results further showed that the inhibition of DNA binding by H2O2 was caused by the oxidation of cysteine residue.

Conclusions

Thiol-based redox-sensing regulators are recognized as an efficient way to combat diverse ROS-inducing stress conditions and enhance the survival of bacteria under oxidative stress. The XRE family is involved in the control of the response to environmental stress, but the functions of XREs related to oxidative stress tolerance, especially their antioxidative molecular mechanisms, are very rarely reported. In this study, we found a MsrR-binding site in the intergenic region between two divergent gene clusters, msrR-3-mst and mfs. β-galactosidase activity assay and qRT-PCR analysis showed that MsrR is indeed negatively autoregulated and also negatively controls the adjacent 3-mst and mfs. In vivo, expression of msrR is induced by H2O2 and CdCl2, and the msrR-deleted (ΔmsrR) mutant displays increased resistance to H2O2 and CdCl2. However, EMSA experiment shows the ability of MsrR to bind the promoter DNA is inhibited by H2O2 but not CdCl2. Many studies reported that the most potent xenobiotics, including oxidants, alkylating agents, antibiotics, or heavy metals, are capable of generating ROS by redox-cycling to produce oxidative stress inside bacteria [51–56]. Thus, CdCl2 might contribute indirectly to ROS production, thereby leading to the derepression of the MsrR operon. Considering high gentamicin- and alkylating agents-resistant phenotype of ΔmsrR strains, we speculated that antibiotics and alkylating agents might also mediate the DNA binding of MsrR with a mechanism similar to CdCl2. We further verified that the XRE-type regulatory MsrR senses and responds to oxidative stress by a derepression of the msrR, 3-mst and mfs genes via intermolecular disulfide formation. Mutational analysis of the sole cysteine in MsrR showed that Cys62 is critical for inactivation of the DNA binding of MsrR, distinguishing it from previously discovered stress response properties of XREs in eukaryotes. On the contrary, the regulatory mechanism of MsrR is similar to those of the ROS sensors OxyR, PerR, and OhrR, which are activated or inhibited by changes in conformation caused by cysteines oxidation.

The XRE family is the second most common family of regulators in bacteria, only four members of which have been reported in previous researches, including S. suis SrtR [19], S. aureus XdrA (XRE-like DNA-binding regulator, A) [21], R. etli RHE-CH00371 [22], and C. aurantiacus MltR (MmyB-like transcription regulator) [23]. Except for SrtR, no obvious effect on oxidative stress resistance for any of the previously studied examples has been reported so far. S. aureus XdrA is shown to play an important role in the β-lactam stress response. Expression of R. etli RHE-CH00371 is reported to be down-regulated in an H2O2-sensitive R. etli mutant. C. aurantiacus MltR is described as being involved in the regulation of antibiotic biosynthesis and thus represents an example for a rather specialized XRE-type regulator. Sequence analysis clearly indicates that the similarity between MsrR and the XREs of bacteria mentioned above is very low, and Cys62 of MsrR is not very conserved (Figure S1b–e), which only appears in position 66 of S. suis SrtR and 55 of S. aureus XdrA. The result is consistent with the previous report that the XRE family contains more than 35,000 proteins and more than 70 structures are available [23]. We suggested that differences in structure may cause versatile features and regulatory mechanisms. It is important to point out, despite their low sequence similarity to MsrR (about 30% identity), we thought S. suis SrtR and S. aureus XdrA might share an oxidation-sensing mechanism as they not only contain the cysteine presumed to serve for oxidation sensing in a relatively conserved position, but they confer resistance to oxidant and β-lactam, respectively, which is similar to MsrR. Combining a phenomenon that β-lactam antibiotics, such as penicillin, can also generate ROS by redox-cycling to produce oxidative stress inside bacteria [55], we speculate that S. suis SrtR and S. aureus XdrA act as a transcriptional sensor via cysteine oxidation-based thiol modifications. Thus, our results provided, for the first time, insight into a new regulatory mechanism adopted by an XRE protein in which DNA-binding ability is regulated by the oxidation of a cysteine residue in the MsrR protein in response to oxidants but not directly bound ligands, such as antibiotics, heavy metals, and alkylating agents. Our data further confirmed the results of Hu et al. showing a member of the XRE family of transcriptional regulators responsible for oxidant tolerance in bacteria [19], facilitating understanding of antioxidant mechanisms in bacteria and providing initial insight into the molecular mechanisms of XREs involved in oxidative stress tolerance. In addition, MsrR is found to be widely distributed in several species of the genera Corynebacterium, such as C. crudilactis, C. efficiens, C. callunae, C. epidermidicanis, and C. minutissimum. Therefore, our study on the regulatory mechanism of MsrR may lead to a better understanding of the stress response mechanisms of these species. Together, our data show that C. glutamicum MsrR acts as a thiol-based redox sensor and, with 3-MST and MFS, comprises an important pathway for protection against oxidative stress.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Table S1. Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study. Table S2. Primers used in this study. Figure S1. Multiple sequence alignment of MsrR with XREs from other organisms. Figure S2. Assays for the ncgl2679-ncgl2678-ncgl2677 co-transcription by reverse transcription PCR. Figure S3. Detailed genetic maps of the regulatory region of MsrR. Figure S4. 104-bp msrR transcript (from the translational start codon (GTG) of msrR gene to 104th nucleotide) was amplified from the remaining msrR ORF (Open Reading Frame) in ΔmsrR mutant with primers QmsrR-F and QmsrR-R. Figure S5. Negative regulation of msrR and mfs by MsrR. Figure S6. Reversible inhibition of the DNA binding activity of MsrR by H2O2 and role of Cysteine residue. Figure S7. Determination of the apparent KD values of MsrR and MsrR:C62S for PmsrR. Figure S8. Mutations in the predicted MsrR binding site derepressed the msrR expression. Figure S9. Oxidative stress-dependent structural changes of relevant MsrR in vivo.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- CHP

Cumene hydroperoxide

- t-BHP

t-Butyl hydroperoxide

- H2O2

Hydrogen peroxide

- MSH

Mycothiol

- GSH

Tripeptide glutathione

- MEN

Menadione

- DMPD

N,N-dimethyl-p-phenylenediamine

- ONPG

ο-Nitrophenyl β-d-galactopyranoside

- DTT

Dithiothreitol

- 3-MST

3 Mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase

- XRE

Xenobiotic response element

- HOCl

Hypochlorous acid

Authors’ contributions

MS and CC designed the research. MS, CC, JZ, XL, YL, and TS performed the research and analyzed the data. GY supervised the research. MS and GY wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31970034), the Key Scientific and Technological Project of Henan Province, China (192102310493), Doctoral Start Fund of Zhoukou Normal University (ZKNUC2018013), and Qufu Normal University Young Teacher Ability Enhancement Program Country (Overseas) Overseas Study (1 year).

Availability of data and materials

All the data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the manuscript and its additional file.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

All authors have agreed to submit this manuscript to microbial cell factories.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Meiru Si and Can Chen contributed equally to this work

Contributor Information

Meiru Si, Email: smr1016@126.com.

Ge Yang, Email: yangge100@126.com.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s12934-020-01444-8.

References

- 1.Mols M, Abee T. Primary and secondary oxidative stress in Bacillus. Environ Microbiol. 2011;13(6):1387–1394. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akaike T, Sato K, Ijiri S, Miyamoto Y, Kohno M, Ando M, Maeda H. Bactericidal activity of alkyl peroxyl radicals generated by heme-iron-catalyzed decomposition of organic peroxides. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1992;294(1):55–63. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(92)90136-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mongkolsuk S, Praituan W, Loprasert S, Fuangthong M, Chamnongpol S. Identification and characterization of a new organic hydroperoxide resistance (ohr) gene with a novel pattern of oxidative stress regulation from Xanthomonas campestris pv. Phaseoli. J Bacteriol. 1998;180(10):2636–2643. doi: 10.1128/JB.180.10.2636-2643.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Valko M, Izakovic M, Mazur M, Rhodes CJ, Telser J. Role of oxygen radicals in DNA damage and cancer incidence. Mol Cell Biochem. 2004;266(1–2):37–56. doi: 10.1023/B:MCBI.0000049134.69131.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dalle-Donne I, Milzani A, Gagliano N, Colombo R, Giustarini D, Rossi R. Molecular mechanisms and potential clinical significance of S-glutathionylation. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2008;10(3):445–473. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anderson ME. Glutathione: an overview of biosynthesis and modulation. Chem Biol Interact. 1998;111–112:1–14. doi: 10.1016/S0009-2797(97)00146-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim IS, Shin SY, Kim YS, Kim HY, Yoon HS. Expression of a glutathione reductase from Brassica rapa subsp. pekinensis enhanced cellular redox homeostasis by modulating antioxidant proteins in Escherichia coli. Mol. Cells. 2009;28(5):479–487. doi: 10.1007/s10059-009-0168-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Storz G, Imlay JA. Oxidative stress. Curr Opin Microbiol. 1999;2(2):188–194. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5274(99)80033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Imlay JA. Pathways of oxidative damage. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2003;57:395–418. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.57.030502.090938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee JW, Soonsanga S, Helmann JD. A complex thiolate switch regulates the Bacillus subtilis organic peroxide sensor OhrR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104(21):8743–8748. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702081104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seth D, Hausladen A, Wang YJ, Stamler JS. Endogenous protein S-Nitrosylation in E. coli: regulation by OxyR. Science. 2012;336(6080):470–473. doi: 10.1126/science.1215643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Storz G, Tartaglia LA, Ames BN. Transcriptional regulator of oxidative stress-inducible genes: direct activation by oxidation. Science. 1990;248(4952):189–194. doi: 10.1126/science.2183352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ehira S, Teramoto H, Inui M, Yukawa H. Regulation of Corynebacterium glutamicum heat shock response by the extracytoplasmic-function sigma factor SigH and transcriptional regulators HspR and HrcA. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:2964–2972. doi: 10.1128/JB.00112-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Busche T, Silar R, Pičmanová M, Pátek M, Kalinowski J. Transcriptional regulation of the operon encoding stress-responsive ECF sigma factor SigH and its anti-sigma factor RshA, and control of its regulatory network in Corynebacterium glutamicum. BMC Genomics. 2012;13:445. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hahn JS, Oh SY, Chater KF, Cho YH, Roe JH. H2O2-sensitive fur-like repressor CatR regulating the major catalase gene in Streptomyces coelicolor. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:38254–38260. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006079200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chi BK, Gronau K, Mäder U, Hessling B, Becher D, Antelmann H. S-bacillithiolation protects against hypochlorite stress in Bacillus subtilis as revealed by transcriptomics and redox proteomics. Mol. Cell Proteomics. 2011;10 (11):M111.009506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Gray MJ, Wholey WY, Parker BW, Kim M, Jakob U. NemR is a bleach-sensing transcription factor. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(19):13789–13798. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.454421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parker BW, Schwessinger EA, Jakob U, Gray MJ. The RclR protein is a reactive chlorine-specific transcription factor in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(45):32574–32584. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.503516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hu Y, Hu Q, Wei R, Li R, Zhao D, Ge M, Yao Q, Yu X. The XRE family transcriptional regulator SrtR in Streptococcus suis is involved in oxidant tolerance and virulence. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2019;8:452. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2018.00452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Novichkov PS, Kazakov AE, Ravcheev DA, Leyn SA, Kovaleva GY, Sutormin RA, Kazanov MD, Riehl W, Arkin AP, Dubchak I, Rodionov DA. RegPrecise 3.0—a resource for genome-scale exploration of transcriptional regulation in bacteria. BMC Genomics. 2013;14(745). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.McCallum N, Hinds J, Ender M, Berger-Bächi B, Stutzmann MP. Transcriptional profiling of XdrA, a new regulator of spa transcription in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 2010;192(19):5151–5164. doi: 10.1128/JB.00491-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martínez-Salazar JM, Salazar E, Encarnación S, Ramírez-Romero MA, Rivera J. Role of the extracytoplasmic function sigma factor RpoE4 in oxidative and osmotic stress responses in Rhizobium etli. J Bacteriol. 2009;191(13):4122–4132. doi: 10.1128/JB.01626-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu Q, van Wezel GP, Chiu HJ, Jaroszewski L, Klock HE, Knuth MW, Miller MD, Lesley SA, Godzik A, Elsliger MA, Deacon AM, Wilson IA. Structure of an MmyB-like regulator from C. aurantiacus, member of a new transcription factor family linked to antibiotic metabolism in actinomycetes. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(7):e41359. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoffman EC, Reyes H, Chu FF, Sander F, Conley LH, Brooks BA, Hankinson O. Cloning of a factor required for activity of the Ah (dioxin) receptor. Science. 1991;252(5008):954–958. doi: 10.1126/science.1852076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reyes H, Reisz-Porszasz S, Hankinson O. Identification of the Ah receptor nuclear translocator protein (Arnt) as a component of the DNA binding form of the Ah receptor. Science. 1992;256(5060):1193–1195. doi: 10.1126/science.256.5060.1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kimura E. l-Glutamate production. In: Eggeling L, Bott M, editors. Handbook of Corynebacterium glutamicum. Boca Raton: Taylor & Francis Group; 2005. pp. 439–464. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee JY, Seo J, Kim ES, Lee HS, Kim P. Adaptive evolution of Corynebacterium glutamicum resistant to oxidative stress and its global gene expression profiling. Biotechnol Lett. 2013;35(5):709–717. doi: 10.1007/s10529-012-1135-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bott M, Niebisch A. The respiratory chain of Corynebacterium glutamicum. J Biotechnol. 2003;104(1–3):129–153. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1656(03)00144-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Si M, Su T, Chen C, Liu J, Gong Z, Che C, Li G, Yang G. OhsR acts as an organic peroxide-sensing transcriptional activator using an S-mycothiolation mechanism in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Microb Cell Fact. 2018;17(1):200. doi: 10.1186/s12934-018-1048-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Si M, Chen C, Su T, Che C, Yao S, Liang G, Li G, Yang G. CosR is an oxidative stress sensing a MarR-type transcriptional repressor in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Biochem J. 2018;475(24):3979–3995. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20180677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Teramoto H, Inui M, Yukawa H. OxyR acts as a transcriptional repressor of hydrogen peroxide-inducible antioxidant genes in Corynebacterium glutamicum R. FEBS J. 2013;280(14):3298–3312. doi: 10.1111/febs.12312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu YB, Long MX, Yin YJ, Si MR, Zhang L, Lu ZQ, Wang Y, Shen XH. Physiological roles of mycothiol in detoxification and tolerance to multiple poisonous chemicals in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Arch Microbiol. 2013;195(6):419–429. doi: 10.1007/s00203-013-0889-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bussmann M, Baumgart M, Bott M. RosR (Cg1324), a hydrogen peroxide-sensitive MarR-type transcriptional regulator of Corynebacterium glutamicum. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(38):29305–29318. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.156372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ehira S, Ogino H, Teramoto H, Inui M, Yukawa H. Regulation of quinone oxidoreductase by the redox-sensing transcriptional regulator QorR in Corynebacterium glutamicum. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(25):16736–16742. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.009027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hong EJ, Kim P, Kim ES, Kim Y, Lee HS. Involvement of the osrR gene in the hydrogen peroxide-mediated stress response of Corynebacterium glutamicum. Res Microbiol. 2016;167(1):20–28. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2015.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tauch A, Kirchner O, Löffler B, Götker S, Pühler A, Kalinowski J. Efficient electrotransformation of Corynebacterium diphtheriae with a mini-replicon derived from the Corynebacterium glutamicum plasmid pGA1. Curr Microbiol. 2002;45(5):362–367. doi: 10.1007/s00284-002-3728-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shen XH, Jiang CY, Huang Y, Liu ZP, Liu SJ. Functional identification of novel genes involved in the glutathione-independent gentisate pathway in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71(7):3442–3452. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.7.3442-3452.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Helbig K, Bleuel C, Krauss GJ, Nies DH. Glutathione and transition-metal homeostasis in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2008;190(15):5431–5438. doi: 10.1128/JB.00271-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Si M, Su T, Chen C, Wei Z, Gong Z, Li G. OsmC in Corynebacterium glutamicum was a thiol-dependent organic hydroperoxide reductase. Int J Biol Macromol. 2019;136:642–652. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.06.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Su T, Si M, Zhao Y, Liu Y, Yao S, Che C, Chen C. A thioredoxin-dependent peroxiredoxin Q from Corynebacterium glutamicum plays an important role in defense against oxidative stress. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(2):e0192674. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0192674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Si M, Zhao C, Burkinshaw B, Zhang B, Wei D, Wang Y, Dong TG, Shen X. Manganese scavenging and oxidative stress response mediated by type VI secretion system in Burkholderia thailandensis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114(11):2233–E2242. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1614902114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Miller JH. A short course in bacterial genetics: a laboratory manual and handbook for Escherichia coli and related bacteria. Cold Spring Harbor: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kimura Y, Toyofuku Y, Koike S, Shibuya N, Nagahara N, Lefer D, Ogasawara Y, Kimura H. Identification of H2S3 and H2S produced by 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase in the brain. Sci Rep. 2015;5:4774. doi: 10.1038/srep14774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sagara Y, Schubert D. The activation of metabotropic glutamate receptors protects nerve cells from oxidative stress. J Neurosci. 1998;18(17):6662–6671. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-17-06662.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lu M, Hu LF, Hu G, Bian JS. Hydrogen sulfide protects astrocytes against H2O2-induced neural injury via enhancing glutamate uptake. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;45(12):1705–1713. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Putman M, van Veen HW, Konings WN. Molecular properties of bacterial multidrug transporters. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2000;64(4):672–693. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.64.4.672-693.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Saier MH, Jr, Paulsen IT. Phylogeny of multidrug transporters. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2001;12(3):205–213. doi: 10.1006/scdb.2000.0246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li K, Xin Y, Xuan G, Zhao R, Liu H, Xia Y, Xun L. Escherichia coli uses separate enzymes to produce H2S and reactive sulfane sulfur from l-cysteine. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:298. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ferro D, Franchi N, Bakiu R, Ballarin L, Santovito G. Molecular characterization and metal induced gene expression of the novel glutathione peroxidase 7 from the chordate invertebrate Ciona robusta. Comp Biochem Physiol C Toxicol Pharmacol. 2018;205:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpc.2017.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cho JS, Chang MS, Rho HM. Transcriptional activation of the human Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase gene by 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin through the xenobiotic-responsive element. Mol Genet Genomics. 2001;266(1):133–141. doi: 10.1007/s004380100536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Halliwell B, Gutteridge J. Oxygen toxicity, oxygen radicals, transition metals and disease. Biochem J. 1984;219:1. doi: 10.1042/bj2190001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hu KH, Li WX, Sun MY, Zhang SB, Fan CX, Wu Q, Zhu W, Xu X. Cadmium induced apoptosis in MG63 cells by increasing ROS, activation of p38 MAPK and inhibition of ERK 1/2 pathways. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2015;36(2):642–654. doi: 10.1159/000430127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Carmel-Harel O, Storz G. Roles of the glutathione- and thioredoxin-dependent reduction systems in the Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae responses to oxidative stress. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2000;54:439–461. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.54.1.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Si M, Zhao C, Zhang B, Wei D, Chen K, Yang X, Xiao H, Shen X. Overexpression of mycothiol disulfide reductase enhances Corynebacterium glutamicum robustness by modulating cellular redox homeostasis and antioxidant proteins under oxidative stress. Sci Rep. 2016;6:29491. doi: 10.1038/srep29491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kohanski MA, Dwyer DJ, Hayete B, Lawrence CA, Collins JJ. A common mechanism of cellular death induced by bactericidal antibiotics. Cell. 2007;130:797–810. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen H, Hu J, Chen PR, Lan L, Li Z, Hicks LM, Dinner AR, He C. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa multidrug efflux regulator MexR uses an oxidation-sensing mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(36):13586–13591. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803391105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study. Table S2. Primers used in this study. Figure S1. Multiple sequence alignment of MsrR with XREs from other organisms. Figure S2. Assays for the ncgl2679-ncgl2678-ncgl2677 co-transcription by reverse transcription PCR. Figure S3. Detailed genetic maps of the regulatory region of MsrR. Figure S4. 104-bp msrR transcript (from the translational start codon (GTG) of msrR gene to 104th nucleotide) was amplified from the remaining msrR ORF (Open Reading Frame) in ΔmsrR mutant with primers QmsrR-F and QmsrR-R. Figure S5. Negative regulation of msrR and mfs by MsrR. Figure S6. Reversible inhibition of the DNA binding activity of MsrR by H2O2 and role of Cysteine residue. Figure S7. Determination of the apparent KD values of MsrR and MsrR:C62S for PmsrR. Figure S8. Mutations in the predicted MsrR binding site derepressed the msrR expression. Figure S9. Oxidative stress-dependent structural changes of relevant MsrR in vivo.

Data Availability Statement

All the data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the manuscript and its additional file.