Abstract

Purpose of review:

The skeletal system provides an important role to support body structure and protect organs. The complexity of its architecture and components makes it challenging to deliver the right amount of the drug into bone regions, particularly avascular cartilage lesions. In this review, we describe the recent advance of bone-targeting methods using bisphosphonates, polymeric oligopeptides, and nanoparticles on osteoporosis and rare skeletal diseases.

Recent findings:

Hydroxyapatite (HA), a calcium phosphate with the formula Ca10(PO4)6(OH)2, is a primary matrix of bone mineral that includes a high concentration of positively charged calcium ion and is found only in bone. This unique feature makes HA a general targeting moiety to the entire skeletal system. We have applied bone-targeting strategy using acidic amino acid oligopeptides into lysosomal enzymes, demonstrating the effects of bone-targeting enzyme replacement therapy and gene therapy on bone and cartilage lesions in inherited skeletal disorders. Virus or no-virus gene therapy using techniques of engineered capsid or nanomedicine has been studied preclinically for skeletal diseases.

Summary:

Efficient drug delivery into bone lesions remains an unmet challenge in clinical practice. Bone targeting therapies based on gene transfer can be potential as new candidates for skeletal diseases.

Keywords: bone-targeting, osteoporosis, metabolic rare skeletal disorders, acidic amino acid oligopeptide, nanoparticles

1. Introduction

Bone has many functions in the body, such as supporting the body structure and movement, protecting organs, regulating mineral homeostasis, and providing bone marrow cells which are differentiated to leukocytes, red blood cells, and platelets. The skeletal organ system consists of inorganic and organic materials, as well as bone cells which synthesize, remodel, and maintain bone [1]. Common skeletal and genetic disorders include osteoporosis, osteoarthritis, bone cancer, metabolic skeletal dysplasia, and infectious bone disease. The increasing number of patients with osteoporosis is a serious problem in an aging society. For instance, osteoporosis is a disease that is characterized by the disruption of bone mass and microarchitecture, which causes nearly 1.3 million fractures each year [2]. Population with osteoporosis and low bone mass based on bone mineral density is estimated at over 50 million older adults in the USA [3]. In addition, patients with unique, inherited skeletal diseases have severe osteoporosis since childhood. However, bone diseases can be difficult to treat, mainly because of a complicated anatomical nature, particularly in the avascular cartilage region [4]. After the administration of a drug, visceral organs will capture most of it, and a limited amount will be available for bone and cartilage distribution. Although high doses can improve the delivery of drugs into skeletal lesions, it may induce adverse effects in multiple organs [4][5]. Thus, effective bone-targeting systems are still required to improve the benefits of drugs on skeletal lesions.

Hydroxyapatite (HA) is a calcium phosphate with the formula Ca10(PO4)6(OH)2, which is found only in both bone and teeth. This unique feature makes HA be an ideal therapeutic target [6] [7], which has led to the development of several bone-targeting techniques to HA. Modification of drugs with bisphosphonate (BP) or acidic amino acid oligopeptide is the major method of bone-targeted drug delivery to the skeletal system. Nanoparticles (NPs) are also used for targeted drug delivery since NPs increase drug stability, improve its solubility, and prevent its degradation [4] [8]. Thus, nanoparticle-based drugs can be delivered to avascular lesions of bone and cartilage more effectively than non-targeted drugs. These specific tissue targeting systems may decrease the systemic side effects by reducing the dose amount or off-target effect.

In this review article, we summarize bone-targeting approaches using bisphosphonate, acidic oligopeptide, and nanoparticles for osteoporosis and related metabolic skeletal disorders. We also describe the effects of bone-targeting therapies on these bone disorders in recent preclinical studies.

2. Bone targeting strategy

2.1. Bisphosphonates (BPs)

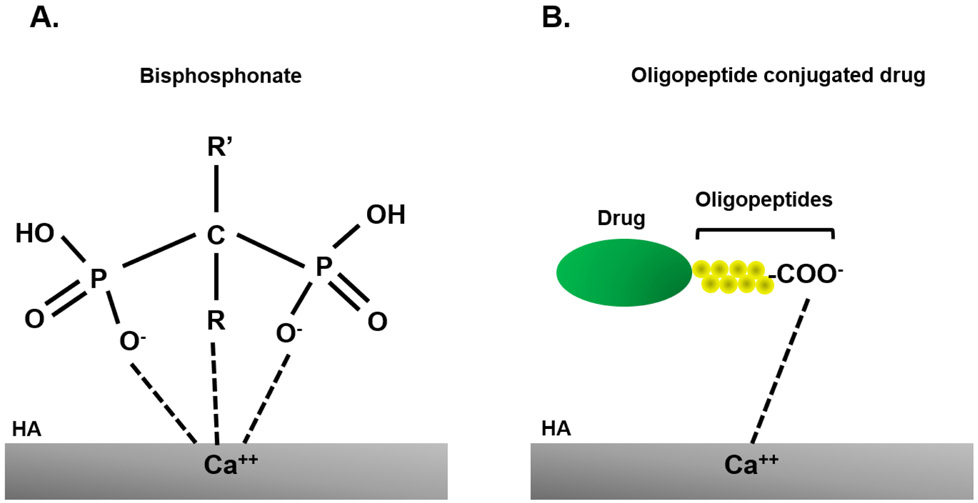

BPs are a group of bone-seeking compounds that have been traditionally utilized for preventing the loss of bone density to treat osteoporosis and similar bone disorders since the effects of BPs on osteoporosis were described in 1968-1969 [9]. As a mechanism of the action of BPs, this chemical can strongly inhibit osteoclastic bone resorption and simultaneously enhance osteoblast differentiation. All BPs, and associated chemicals, share two terminal phosphate bonds (P-C-P) structure in common (Figure 1A). These side chains or R groups can influence binding interactions with bone. BPs have a strong affinity with calcium phosphate in HA by charge, which is a major bone matrix. Nitrogen-containing BPs (N-BPs), such as alendronate (ALN), zoledronic acid, and pamidronate, showed a higher binding affinity with HA than non-nitrogen containing ones [10]. Non-nitrogen-containing BPs are metabolized to cytotoxic ATP analogs and lead to osteoclast apoptosis. On the other hand, N-BPs are not metabolized and inhibit farnesyl pyrophosphate synthase, which is required for osteoclast function [11]. Due to the preferential binding to the bone, BPs considered very useful in the development of targeting moieties aimed at treating diseases with skeletal symptoms, particularly alveolar bone loss. However, BPs still have risks of adverse side effects of atrial fibrillation and gastrointestinal problems.

Figure 1. Binding of bisphosphonate and oligopeptide conjugated drug to bone.

(A) Chemical structure of bisphosphonates. Two side chains (R and R’) determine the chemical prosperities of bisphosphonates. Bisphosphonates specifically bind to HA via coordination between two phosphate groups (and a hydroxyl group in R) and calcium ions of the crystal structure. (B) Negatively-charged acidic amino acid tagged drugs circulate in blood for longer time and delivered into bone more efficiently. These negatively-charged drugs bind with calcium site on HA. HA: hydroxyapatite.

The modification of proteins with BPs should be useful to target skeletal lesions since most protein drugs seeking the bone do not have a high affinity with HA in physiological conditions. Previous studies showed that BP modification improved the bone-targeting delivery of osteoprotegerin, which is a decoy receptor for activator of nuclear factor κB ligand (RANKL) inhibitor that prevents osteoclastogenesis in a rat model [12]. Intravenous administration of BP-modified bovine catalase suppressed bone metastasis in mice [13] Furthermore, Katsumi et al. showed that ALN modification of bovine serum albumin and glutathione reductase, high molecular-weight protein, successfully achieved bone targeting and also demonstrated that approximately 3 to 4 ALN per protein is an optimal degree of modification for bone targeting of these proteins [14].

2.2. Acidic amino acid oligopeptide

HA is an ideal bone-targeted site since HA is a major inorganic component in bone and does not exist in soft tissues. Bone noncollagenous proteins, osteopontin and bone sialoprotein, bind to HA, and these proteins have a repeated sequence of acidic amino acid, asparatic acid (Asp) and glutamic acid (Glu) in their structure [15][16][17]. Based on these reports, Fujisawa et al. showed that poly glutamic peptides (six Glu) preferentially bound to HA [18]. Thus, acidic amino acid-conjugates have been developed as bone-targeted drugs to enhance therapeutic effects (Figure 1B).

The number of residues of Asp and Glu favors the affinity with HA, and, therefore, the in vivo study showed that the oligopeptides with six and more residues long attached to fluorescent probe 9-fluorenylmethylchloroformate (Fmoc) were detected primarily in bone [19]. Additionally, in vitro experiments showed that the acidic oligopeptide affinity for HA did not depend on the isoforms L-peptides or D-peptides; however, D-isoform showed better compatibility with the bone and a low immune system recognition [20] [21] [19]. Taking advantage of biocompatible features of acidic oligopeptides, the studies in various fields have been performed with the conjugate of D- and L-peptides for selective delivery to the bone. These included 1) enzymes used for enzyme replacement therapy (ERT), 2) hormones, 3) antibiotics, 4) small interfering RNAs (siRNAs), and 5) gene therapy [4][22][23][24] [25][26].

Oligopeptides conjugated with si-RNA treatment showed a successful target for osteoclasts located in bone surfaces. In 2012, Zhang et al. treated an osteoporotic rat model by using a delivery system form by dioleoyl trimethylammonium propane (DOTAP)-based cationic liposomes attached to oligopeptide (AspSerSer)6 as specific bone moiety. The small interfering RNA (siRNA) against casein kinase-2 interacting protein-1 (Plekho1), an inhibitor of bone formation, was delivered to the bone [22][27]. The results of immunohistochemistry and flow cytometry showed that (AspSerSer)6 –liposome allowed delivery of the Plekho1-siRNA and knockout of Plekho1 in osteogenic cells, even in healthy rats and that liposome plus (AspSerSer)6 moiety improved the longevity and activated of osteoblasts [22][27][28]. These results proved the acidic oligopeptides as a system delivery for siRNA that is specific to osteogenic cells in the bone.

In 2012, Bo et al. used the acidic oligopeptide with D6 (L-Asp hexapeptide; Asp6) as bone target moiety in combination with a RGD7 (R-G-D-D-D-D-D-D-D) like a tumor target for direct delivery of the anti-cancer drug, 5-fluorouracil, to the bone cancer cells [29]. Both in vitro and in vivo results showed the stability and release of the active drug as well as the high affinity to the bone. Oligopeptides, as a ligand or receptor, demonstrated the affinity and selectivity for the bone. This strategy would be applied to treat different bone lesions like cancer or osteoporosis [29].

In summary, the oligopeptide system presents advantages and disadvantages; the authors describe the great advantages of this system are the high biocompatible to the bone, the efficacy and specificity delivery of drugs [4] [20] [30] [29]. Additionally, in vitro and in vivo results concluded that the oligopeptide system has low immune system recognition, thus reducing the undesired side effects [21]. For those reasons, the L- and D-peptides isoforms are a potential system to treat osteoporosis and bone diseases. However, oligopeptide-based delivery to bone have some problems to tendency of aggregation and/or low stabili [5][31].

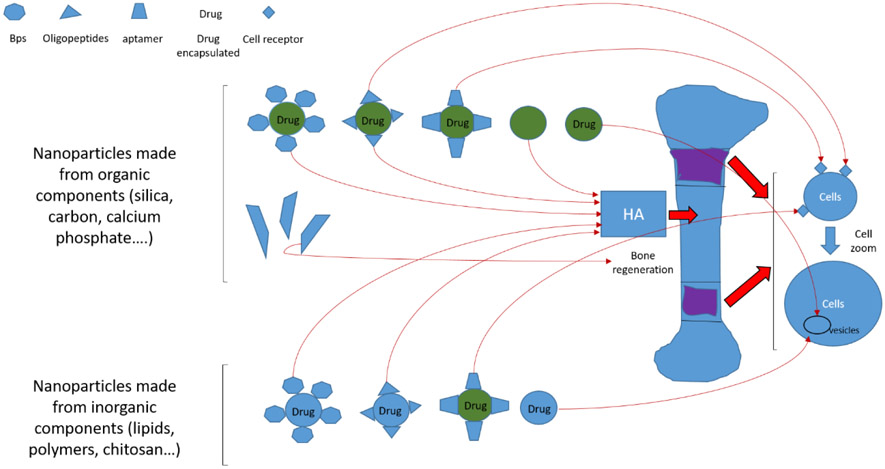

2.3. Nanoparticle

Nanotechnology is being used as another alternative method for bone-targeted treatment. Because of its small size feature and similarity in components found in tissues [32], the nanoparticle materials can be delivered to specific tissues, organelles or cells where the medicine will be released [33]. The advantage of nanoparticles provides a large capacity of the drug concerning size [34] [35], improves solubility [36], gives stability to the drug [37], reduces adverse effects [38], and improves transport to internalize in specific organelles [39]. Another advantage is that the nanoparticles, which are made of calcium phosphate, gold, and nanodiamonds, can help to activate functions in the cells, improve the mineralization, and stimulate bone growth [38]. Thus, nanotechnology can overcome the limitations of conventional bone therapy, such as adverse effects and poor penetration to skeletal lesions. Moreover, adding targeting ligands such as peptides, aptamers, or small molecules can improve bone-targeting ability [40].

Nanoparticles can be classified into two groups: organic and inorganic. Organic nanoparticles are solid particles composed of organic compounds such as polymers, protein, peptide, or lipid [41]. The advantage of organic nanoparticles is that they have low toxicity and improve passive and active transport to target lesions. Inorganic nanoparticles are composed of silica, silicon materials, metals (gold, titanium, silver), Oxides (ZnO, TiO2, SiO2) semiconductor metals (CdS and CdSe -quantum dots-) carbon (nanodiamond, nanotubes) and iron oxides or other magnetic elements as nickel or cobalt (magnetic nanoparticles). For certain applications, there are several advantages of inorganic nanoparticles over organic ones, including high stability and precise control over shape and size [42]. These two types of nanoparticles have been applied to bone-targeting methods, and the effects of this strategy on bone disorders have been reported in many preclinical studies (Table 1).

Table 1.

Different combinations of nanoparticle systems

| Ligands | Materials | types drugs encapsulated | Therapeutic uses |

|---|---|---|---|

| BPs | CaP | Anti-inflammatories drugs Antibiotics drug Growth factors Genes Small molecules |

Osteogenesis, inflammation, infections, post-surgery, osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, analgesics, osteoporosis, gene therapy, cancer |

| Silica | Genes | Gene therapy | |

| Nanotubes | Implants Small molecules |

Surgeries, bone repair, osteoporosis | |

| Metals | antimicrobial | ||

| Nanodiamonds | Small molecules | osteoporosis | |

| Chitosan | Genes | Gene therapy | |

| BPs Oligopeptides Aptamer |

Polymers | Proteins Hormones Growth factors Small molecules Scaffold |

Osteogenesis, bone repair, osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, osteoporosis, cancer. |

| BPs Oligopeptides Aptamer |

Lipid | Proteins Hormones Growth factors Small molecules |

Osteogenesis, mucopolysaccharidosis, osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, cancer. |

Abbreviation

BPs, biosphosphonates; CaP, calcium phosphate

BP conjugates nanoparticles have been developed because this bone target moiety can act as a useful drug delivery system to bone. Poly (D, L-lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) nanoparticles modified with both, polyethylene glycol (PEG) and ALN, showed a strong absorption with increased ALN concentration [43]. Zoledronate tagged PLGA NPs conjugated with docetaxel also showed prolong blood circulation and higher retention at the bone site [44]. Doxorubicin conjugated with PLGA and ALN demonstrated a significant reduction of incidence of bone metastases compared with the free drug [45] [46]. Doxorubicin-loaded liposomes modified with ALN and an aqueous polyelectrolyte, poly (acrylic acid) showed the prolonged presence of doxorubicin in osteosarcoma tumor and significantly improved efficacy in a xenograft mouse model [47]. Swami et al. demonstrated the effect of bortezomib conjugated with PLGA, PEG, and BPs in mouse models of multiple myeloma. These targeted NPs enhanced survival and decreased tumor burden in the model mice more efficiently than the free drug [48].

3. Bone targeting for diseases

3.1. Osteoporosis

Osteoporosis is a common health problem, especially in older women, leading to the loss of bone mineral density (BMD) and the increase in the risk of fractures. Some of risk factors can increase the likelihood of developing osteoporosis, including age, hormone imbalance, life-style, and medical conditions. The reduction of estrogen level at menopause in women or testosterone level in men is a strong risk factor for this disease. Hormonal changes during the menopause cause the elevation of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) level and the reduction of estradiol (E2) level, resulting in a progressive decline in BMD [23] [49][50]. Treatment for the regeneration of bone in postmenopausal women was initiated with estrogen replacement therapy; however, this treatment could develop endometritis and breast and uterus cancer if used for a long period [4] [23]. Therefore, development of bone-targeting treatment for osteproposis should be required to enhance therapeutic efficacy and to alleviate the side effects of conventional therapy.

Bone targeting therapy using the oligopeptide with BPs and NPs has been developed in preclinical studies. Yokogawa et al. used the oligopeptide, L-Asp-hexapeptide (3D6), attached with E2 for specific delivery to the bone in ovariectomized (OVX) mice [24] [51] [52]. The weekly administration of E2·3D6 (0.11 to 1.1 mmol/kg·sc) showed a high affinity for bone and specific delivery of E2 to the osteoblasts. Consequently, an increase of bone matrix proteins as osteopontin, type I collagen α, and sialoprotein after 4 hours of injection was detected [51]. In addition, this treatment increased the BMD and improved the architecture of bone. Moreover, E2·3D6 showed a low affinity to ERα and ERα and decreased the risk of cancer and endometritis [51] [52]. These results postulate the acidic oligopeptides as a right candidate for specific delivery to the osteoporotic bone.

BP-modified drugs for osteoporosis have been developed in preclinical studies. PEG-conjugated hormones such as parathyroid hormone (PTH) or calcitonin were prepared, and BP-mediated conjugates were synthesized. The effects of these hormones mediated by BP were tested in animal models, and these bone targeting drugs showed significant improvement of bone strength and formation of osteoporosis model rats [53] [54]. BP-conjugated prodrugs of prostaglandin E2 and 17β-estradiol were also developed [55][56]. Repeated administration of either of these conjugated compounds in animal models of osteoporosis showed specific delivery to bone and improvement of BMD compared with that of free compounds.

3.2. Inherited metabolic diseases causing osteoporosis

3.2.1. Mucopolysaccharidoses (MPS IVA)

Mucopolysaccharidoses (MPS) are a group of inherited lysosomal metabolic diseases caused by the deficiency of lysosomal enzymes, leading to excessive accumulation of glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) in multiple tissues, including bone and cartilage. Types of GAG are dermatan sulfate (DS), chondroitin sulfate (CS), heparan sulfate (HS), keratan sulfate (KS), and/or hyaluronan. In general, clinical symptoms do not appear in newborn patients with MPS, and growth impairments start during the first 2 to 4 years of age [57][58]. Skeletal deformities are common symptoms in any types of patients with MPS, including kyphoscoliosis, lumbar gibbus, flaring of the rib cage, pectus carinatum, abnormal joint mobility (rigidity or laxity of joint), short stature, and genu valgum.

MPS IVA (also called Morquio syndrome type A) is caused by a deficiency of N-acetylgalactosamine-6-sulfate sulfatase (GALNS), leading to KS and chondroitin-6-sulfate (C6S) accumulation. This disease shows the most severe skeletal dysplasia among all types of MPS with incomplete ossification and successive thin cortical bone. Most patients with MPS IVA show marked low bone mineral density and osteoporotic status [59][60]. This skeletal disorder often causes airway compromise such as trachea obstruction and respiratory infection and sometimes provides the risks of dying of sleep apnea and related complications. ERT and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) are available for patients with MPS IVA. We have followed the therapeutic efficacy of conventional ERT and HSCT on growth, activity of daily living (ADL), and frequency of surgery [61]. Doherty et al. showed that conventional ERT did not have an impact on bone growth of MPS IVA patients even if ERT started at 2 years of age [62]. We also showed that HSCT is likely to have more effects on bone and cartilage lesions of patients with this disease than ERT since HSCT improved an ADL and a surgical frequency compared to ERT [49]. However, HSCT did not provide a significant impact on the bone growth of patients with MPS IVA, even if HSCT started at 4 years of age [63][64]. Nevertheless, it remains unknown if ERT and HSCT may provide a benefit in bone growth if they start before one year of age. Therefore, the approach for bone and cartilage lesions of MPS IVA is still an unmet challenge.

We have applied bone-targeting approaches using the acidic amino acid oligopeptide to ERT and have examined the effects of this bone-targeted ERT on bone and cartilage lesions of murine models, including MPS IVA and MPS VII [65][66]. The human GALNS enzyme was bioengineered with N-terminal extension conjugated by hexa-glutamate sequence (E6), and this modified enzyme was administered to the MPS IVA mouse. Half-life time of this enzyme was markedly prolonged compared with a native enzyme, and the enzyme activity in bone was also retained longer in bone after a single administration of enzymes, indicating that the modified enzyme was circulated for a longer time and was selectively delivered into bone lesions. After weekly administration of 1 mg/kg of this enzyme for 12 or 24 weeks, the pathological findings in this mouse model showed substantial clearance of storage materials from chondrocyte in the growth plate and improvement of column structure [65]. These improvements of skeletal lesions were also seen when we administered E6-β-glucuronidase into MPS VII mice [66].

Nanomedicine should be another candidate treatment option for MPS IVA. Alvarez et al. developed nanostructured lipid carriers (NLC) containing the GALNS enzyme. They studied its stability, efficacy, and distribution pattern of the enzyme immobilized in NLC by both in vitro and in vivo experiments. The results showed that the NLC stabilized the GALNS enzyme, reached to the lysosome, and reduced GAG accumulation in cartilage cells. After the intravenous administration of the NLC, the GALNS enzyme was also distributed to hard-to-accessible organs such as bone and cartilage regions [67][68].

3.2.2. Hypophosphatasia (HPP)

Hypophosphatasia (HPP) is characterized by defective mineralization of bone and/or teeth in the presence of low activity of serum and bone alkaline phosphatase (TNSALP). HPP comprises six clinical forms usually recognized based on age at diagnosis and severity of features. HPP is caused by mutations in the ALPL gene [69][70][71]. Perinatal and infantile HPP are inherited in an autosomal recessive manner. The milder forms, especially adult forms and odontohypophosphatasia, may be inherited in an autosomal recessive or autosomal dominant manner. Mornet et al. have shown that the more frequent mutation within HPP patients is a missense mutation and that patients with several phenotypes had less activity while patients with the mid phenotypes had low levels of enzymatic activity [72]. TNSALP is expressed in bone, liver, kidney, adrenal tissues, and teeth, and this enzyme hydrolyzes inorganic pyrophosphate (PPi) in the bone. Unmetabolized PPi inhibits the growth of the HA crystals, which are important molecules for calcification of chondrocytes with the correct bone mineralization [69][70][71]. As a result of the accumulation of PPi in the bone, HPP causes low bone mineralization, leading to variable clinical manifestations such as osteoporosis, premature loss of detention, rickets, calcific arthropathies during adulthood, hypercalcemia and severe hypomineralization, respiratory failure due to lung hypoplasia lung, hypercalcemia, vitamin-B6-dependent seizures and death in utero or few days after the birth [69][70][71][73].

ERT has been a potential to treat HPP since this metabolic disease is caused by a single enzyme deficiency. The study of the therapeutic efficacy of the ERT for HPP started since the 1990s with an enzyme purified from human tissues [74][70][71]. These studies showed an improvement in visceral organs and normalization of the enzyme level in blood circulation; however, the outcomes from these studies did not show any significant improvement in bone mineralization [69][70][71][75][76][74]. In 2006, Nishioka et al. reported the improvement in bone mineralization after the administration of the C-terminal-anchorless TNSALP enzyme with an oligopeptide. This modified enzyme works as a motif to allow the specific delivery to bone in in vitro affinity experiments. The in vitro assays showed that labeled enzymes with L-Asp had a 30-fold higher affinity to HA, and in vivo biodistribution analysis revealed that the labeled-enzyme was retained in bone of AKP−/− mice after 18 hours intravenous (IV) administration. Additionally, in vitro assays in bone marrow from HPP patients showed that the TNSALP-L-Asp enzyme could mineralize the bone marrow. Taken together, Nishioka et al. showed that TNSALP-L-Aspenzyme was delivered to the bone with high specificity and with the bioactivity to mineralize the bone [69]. Based on further investigation of the TNSALP combined with the acidic oligopeptide, clinical trials of ERT for HPP were conducted, and asfotase alfa (human TNSALP-Strensiq™) was approved in 2015 in Japan, Canada, United States, and Europe Union for perinatal, infants, and childhood (under 18 ages) HPP patients [77] [70][71]. Asfotase alfa is composed of TNSALP, FC fragment of IgG1, and (ASP)10 (a deca-aspartate) motif [70][71]. The IV administration of asfotase alfa in preclinical and clinical studies showed normalization of TNSALP in blood and organs, improvement of clinical complications related to skeletal and dental defects, and reduction of the accumulation of PPi in lung and muscle [70][71][77][78].

The therapeutic efficacy of ERT in adults or in HPP patients with mild symptoms has not been studied in-depth since gene therapy carrying TNSALP has been explored in the animal model. Alternative treatment using stem cells and gene therapy is currently being investigated. The first studies have shown that the genetic correction in two childhood HPP patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells recovers enzyme activity and calcification in vitro [70][77][79]. Several studies showed that a single injection of vectors with TNALP with deca-aspartates (D10) at the C-terminus in newborn AKP−/− mice corrected the expression of TNALP level and improved some clinical manifestations [80][81][82].

In 2011, Matsumoto et al. reported that the AKP−/− mice treated with single postnatal IV injection of adeno-associated virus 8 (AAV8) vectors carrying TNALP-D10 improved the survival rate with correct mineralization of the epiphyses. However, high levels of ALP activity detected in plasma decreased with time from 165.1 ± 79.8 U/ml in day 10 to 13.7 ± 1.1 U/ml on day 28. This consequence led to the interference of the treatment in bone mineralization [80].

Continuing with the studies of the efficacy of the AAV8-TNALP-D10 vector and better clinical applicability, Ikeue et al. developed a self-complementary AAV8 (scAAV8) vector that carrying TNALP-D10 under the control of the muscle creatine kinase (MCK) promoter and they treated the scAAV8 vector with AKP2−/− neonatal mice. In this study, 2.5 x 1012 vg/body of scAAV8-MCK-TNALP-D10 vector was injected into the bilateral quadriceps and showed the effectivity of expression of the vector in bone and muscle [83]. The ALP activity in plasma increased over 1 U/ml during 90 days post-injection, and physical activity, facial appearance, and mineralization of dentin structure were improved. The bone structure also showed improvements evaluated by radiology analysis [81][83]. Nevertheless, the micro-CT analysis still showed low bone mineralization and abnormal bone architecture [81]. These data indicate that the vector used allowed the delivery safely to bone and muscle in AKP2−/− mice. Still, the therapeutic effect remained incomplete in the improvement of bone mineralization and architecture. A further study on the effects of scAAV8-MCK-TNALP-D10 showed a high doses of 4.5 x 1012 vg/body injected into the bilateral quadriceps in newborn AKP2−/− mice could increase ALP activity to 20 U/ml in blood and improved the mineralization and bone structure analyzed by micro-CT and radiological analysis. In addition, the histological analysis in growth plate showed normal growth and well-organized cartilage arrangement of AKP2−/− mice treated with 4.5 x 1012 vg/body [84].

4. Future directions

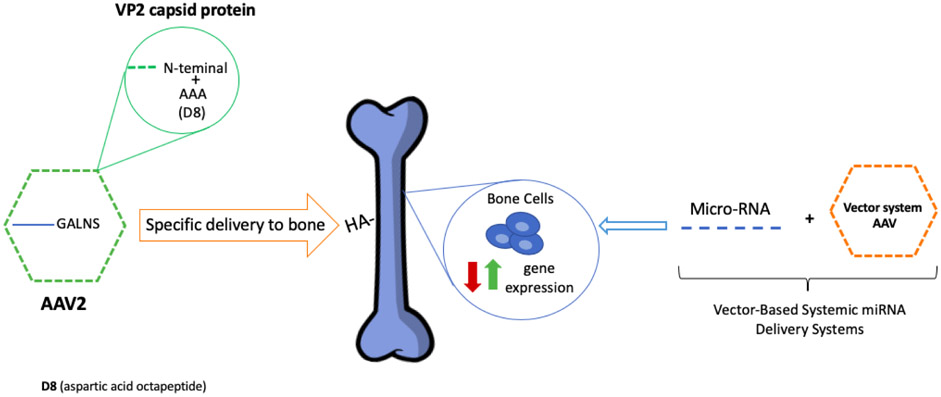

The recent results from different studies on the metabolic disorders showed that gene therapy as an excellent candidate to treat skeletal manifestations. In 2018, Almeciga et al. demonstrated a novel strategy for specific delivery of AAV vector to the bone by introducing an aspartic acid octapeptide (D8) in the N-terminal region of the VP2 capsid protein of AAV2 vector. After the administration into MPS IVA mice, the AAV2-D8 vector showed a high affinity to HA, a high number of copies of the viral vector, and an increased GALNS enzyme activity in bone after 3 months after IV injection [25][26] (Figure 3). These results showed that the bone-targeting peptide in the capsid vector was a possible retargeting of the AAV vector, leading to the treatment of bone diseases.

Figure 3. Future directions for osteoporosis treatment.

AAV gene therapy with acidic oligopeptides (aspartic octapeptide-D8) in the capsid protein increases the specificity of the treatment in bone lesions. Additionally, miRNAs treatment with the AAV vector system increases the expression of the underlying gene directly in the bone.

On the other hand, to lead the gene therapy to molecular and metabolic regulation levels, modified microRNA (miRNA) therapy started to treat bone diseases. In 2019, Sun et al. reviewed the potency of miRNA-base gene therapies for bone regeneration, improving the bone structure and preventing osteoporosis and its osteoporotic fracture. The miRNAs played an important role in a variety of cell processes like proliferation and differentiation in bone cells [85][86]. The miRNAs treatment provides two roles; 1) reduce the expression of pathological genes related to bone formation and 2) increase the expression of genes that lose the activity during pathological bone development. However, this kind of treatment could result in low stability in the organism, low specificity to bone, and off-target effects [85]. To resolve the limitations of specificity and efficacy delivery of miRNAs, the recent studies made the combination with the vector like AVV or Baculovirus vector increased the specificity of the delivery to bone. These kinds of systems are called Viral Vector- Based Systemic miRNA Delivery Systems (Figure 3) [85][86]. The miRNAs-based treatment needs to be investigated further with an excellent potency for bone treatment. For future directions in gene therapy, we have to generate clinically effective drugs for bone degeneration without the off-targeting effect.

5. Conclusion

Prevention and resolution of bone and cartilage lesions remain an unmet challenge in patients with skeletal diseases, causing osteoporosis. Bone-targeted therapy provides several advantages of delivering the right amount of drug to skeletal lesions, decreasing drug dosage, reducing adverse effects, and increasing therapeutic efficacy over non-targeting treatment. Bone-targeting approaches using polymeric oligopeptides and nanoparticles have been developed all over few decades; however, these achievements remain in the preclinical phase. Further studies should be required to move forward to the clinical level. Gene therapy combined with a bone-targeting strategy such as acidic amino acid oligopeptide and nanomedicine can be potential as the next generation of one-time therapy to correct the systemic bone diseases.

Figure 2.

Different components for targeting organic and inorganic nanoparticles to the bone. There are more unspecific nanoparticles whose targets are the vesicles inside cells or receptors on the cell surface. Organic materials as a family of CaP are more specific for targeting bone. These materials bind with the ligands like BPs, acidic oligopeptides, and aptamers to target bone. Other organic materials as silica, nanotubes of carbon, and magnetic nanoparticles are alternatives binding with the ligands and targeting bone lesions.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by grants from National MPS Society Research Grant, Austrian MPS society, The Carol Ann Foundation, Deborah McClellan and Brant Cali Foundation, The Radiant Hope donation, Angelo R. Cali & Mary V. Cali Family Foundation, Inc., The Vain and Harry Fish Foundation, Inc., The Bennett Foundation, Jacob Randall Foundation, Help Morquio Foundation, Vice family, Lubert Family Foundation, Straughan Family, Paidipalli Family, and Nemours Funds. S.T. was supported by an Institutional Development Award (IDeA) from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of NIH under grant numbers P20GM103464 and P30GM114736. CJAD was supported by the Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation (Contract 120380763212 – PPTA # 8352).

Abbreviations:

- AAV

adeno-associated virus

- ADL

activity of daily living

- ALN

alendronate

- Asp

aspartic acid

- BMD

bone mineral density

- BPs

bisphosphonates

- C6S

chondroitin-6-sulfate

- D8

aspartic acid octapeptide

- E2

estradiol

- ERT

enzyme replacement therapy

- GAG

glycosaminoglycans

- GALNS

N-acetylgalactosamine 6-sulfate sulfatase

- Glu

glutamic acid

- HA

hydroxyapatite

- HPP

hypophosphatasia

- HS

heparan sulfate

- HSCT

hematopoietic stem cell transplantation

- IV

intravenous

- KS

keratan sulfate

- miRNA

microRNA

- MPS

mucopolysaccharidosis

- N-BPs

nitrogen-containing BPs

- NLC

nanostructured lipid carriers

- NPs

nanoparticles

- OVX

ovariectomized

- PEG

polyethylene glycol

- PLGA

poly (D,L-lactic-co-glycolic acid)

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of a an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Reference:

- 1.Farrell KB, Karpeisky A, Thamm DH, Zinnen S. Bisphosphonate conjugation for bone specific drug targeting [Internet] Bone Reports. Elsevier Inc; 2018. [cited 2020 Apr 16]. p. 47–60. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29992180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Riggs BL, Melton LJ. Involutional Osteoporosis. N. Engl. J. Med 1986. p. 1676–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wright NC, Looker AC, Saag KG, Curtis JR, Delzell ES, Randall S, et al. The recent prevalence of osteoporosis and low bone mass in the United States based on bone mineral density at the femoral neck or lumbar spine J Bone Miner Res [Internet]. John Wiley and Sons Inc.; 2014. [cited 2020 Apr 16];29:2520–6. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24771492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stapleton M, Sawamoto K, Almeciga-Diaz CJ, Mackenzie WG, Mason RW, Orii T, et al. Development of Bone Targeting Drugs. Int J Mol Sci. Department of Biological Sciences, University of Delaware, Newark, DE 19716, USA. mstaple@udel.edu; Nemours/Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children, Wilmington, DE 19803, USA. mstaple@udel.edu; Nemours/Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children, Wilmington, ; 2017;18: 10.3390/ijms18071345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carbone EJ, Rajpura K, Allen BN, Cheng E, Ulery BD, Lo KWH. Osteotropic nanoscale drug delivery systems based on small molecule bone-targeting moieties Nanomedicine Nanotechnology, Biol. Med Elsevier Inc.; 2017. p. 37–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang D, Miller SC, Kopečková P, Kopeček J. Bone-targeting macromolecular therapeutics. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2005. p. 1049–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clarke B Normal bone anatomy and physiology Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol American Society of Nephrology; 2008. p. S131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khan I, Saeed K, Khan I. Nanoparticles: Properties, applications and toxicities Arab. J. Chem Elsevier B.V.; 2019. p. 908–31. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Russell RGG. Bisphosphonates: The first 40 years. Bone. 2011. p. 2–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nancollas GH, Tang R, Phipps RJ, Henneman Z, Gulde S, Wu W, et al. Novel insights into actions of bisphosphonates on bone: Differences in interactions with hydroxyapatite. Bone. 2006;38:617–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drake MT, Clarke BL, Khosla S. Bisphosphonates: Mechanism of action and role in clinical practice Mayo Clin. Proc Elsevier Ltd; 2008. p. 1032–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doschak MR, Kucharski CM, Wright JEI, Zernicke RF, Uludag H. Improved bone delivery of osteoprotegerin by bisphosphonate conjugation in a rat model of osteoarthritis. Mol Pharm [Internet], 2009. [cited 2020 Apr 16];6:634–40. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19718808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zheng Y, Nishikawa M, Ikemura M, Yamashita F, Hashida M. Development of bone-targeted catalase derivatives for inhibition of bone metastasis of tumor cells in mice J Pharm Sci [Internet]. John Wiley and Sons Inc.; 2012. [cited 2020 Apr 16]; 101:552–7. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21953593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Katsumi H, Sano JI, Nishikawa M, Hanzawa K, Sakane T, Yamamoto A. Molecular design of bisphosphonate-modified proteins for efficient bone targeting in vivo PLoS One. Public Library of Science; 2015;10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Butler WT. The nature and significance of osteopontin Connect Tissue Res. Informa Healthcare; 1989;23:123–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oldberg A, Franzen A, Heinegard D. Cloning and sequence analysis of rat bone sialoprotein (osteopontin) cDNA reveals an Arg-Gly-Asp cell-binding sequence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:8819–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oldberg A, Franzen A, Heinegard D. The primary structure of a cell-binding bone sialoprotein. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:19430–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fujisawa R, Wada Y, Nodasaka Y, Kuboki Y. Acidic amino acid-rich sequences as binding sites of osteonectin to hydroxyapatite crystals Biochim Biophys Acta - Protein Struct Mol Enzymol. Elsevier B.V; 1996;1292:53–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sekido T, Sakura N, Higashi Y, Miya K, Nitta Y, Nomura M, et al. Novel Drug Delivery System to Bone Using Acidic Oligopeptide: Pharmacokinetic Characteristics and Pharmacological Potential J Drug Target [Internet]. Taylor & Francis; 2001;9:111–21. Available from: 10.3109/10611860108997922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Low SA, Kopecek J. Targeting polymer therapeutics to bone Adv Drug Deliv Rev. Department of Bioengineering, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT 84112, USA.: Elsevier B.V; 2012;64:1189–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vinay R, KusumDevi V Potential of targeted drug delivery system for the treatment of bone metastasis Drug Deliv [Internet]. Taylor & Francis; 2016;23:21–9. Available from: 10.3109/10717544.2014.913325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang G, Guo B, Wu H, Tang T, Zhang BT, Zheng L, et al. A delivery system targeting bone formation surfaces to facilitate RNAi-based anabolic therapy Nat Med. Musculoskeletal Research Laboratory, Department of Orthopaedics & Traumatology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China.; 2012;18:307–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sipila S, Tormakangas T, Sillanpaa E, Aukee P, Kujala UM, Kovanen V, et al. Muscle and bone mass in middle-aged women: role of menopausal status and physical activity J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. Gerontology Research Center, Faculty of Sport and Health Sciences, University of Jyvaskyla, Jyvaskyla, Finland.; Gerontology Research Center, Faculty of Sport and Health Sciences, University of Jyvaskyla, Jyvaskyla, Finland.; Gerontology Research Center, : The Authors. Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia and Muscle published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd on behalf of Society on Sarcopenia, Cachexia and Wasting Disorders; 2020; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luhmann T, Germershaus O, Groll J, Meinel L. Bone targeting for the treatment of osteoporosis J Control Release. Institute for Pharmacy and Food Chemistry, University of Wurzburg, Am Hubland, DE-97074 Wurzburg, Germany.: Elsevier B.V; 2012;161:198–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alméciga-Díaz CJ, Montaño AM, Barrera LA, Tomatsu S. Tailoring the AAV2 capsid vector for bone-targeting. Pediatr Res [Internet]. 2018;84:545–51. Available from: 10.1038/s41390-018-0095-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alméciga-Diaz CJ, Barrera LA. Design and applications of gene therapy vectors for mucopolysaccharidosis in Colombia. Gene Ther [Internet]. 2020;27:104–7. Available from: 10.1038/s41434-019-0086-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ray K Silencing inhibitors of bone formation. Nat Rev Rheumatol [Internet]. 2012;8:122 Available from: 10.1038/nrrheum.2012.17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alencastre I, Sousa D, Alves C, Leitão L, Neto E, Aguiar P, et al. Delivery of pharmaceutics to bone: Nanotechnologies, high-throughput processing and in silico mathematical models. Eur Cell Mater. 2016;31:355–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jiang B, Cao J, Zhao J, He D, Pan J, Li Y, et al. Dual-targeting delivery system for bone cancer: synthesis and preliminary biological evaluation Drug Deliv [Internet]. Taylor & Francis; 2012;19:317–26. Available from: 10.3109/10717544.2012.714809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li CJ, Liu XZ, Zhang L, Chen LB, Shi X, Wu SJ, et al. Advances in Bone-targeted Drug Delivery Systems for Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy for Osteosarcoma. Orthop Surg. Department of Orthopaedics, School of Medicine, Jinling Hospital, Nanjing University, Nanjing, China.; Department of Orthopaedics, School of Medicine, Jinling Hospital, Nanjing University, Nanjing, China.; Department of Orthopaedics, School of Medicine, J: Chinese Orthopaedic Association and John Wiley & Sons Australia, Ltd; 2016;8:105–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aoki K, Alles N, Soysa N, Ohya K. Peptide-based delivery to bone [Internet]. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. Adv Drug Deliv Rev; 2012. [cited 2020 Jul 13]. p. 1220–38. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22709649/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nguyen TBL, Min YK, Lee B-T. Nanoparticle biphasic calcium phosphate loading on gelatin-pectin scaffold for improved bone regeneration. Tissue Eng Part A [Internet]. 2015;21:1376–87. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25602709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ma X, Gong N, Zhong L, Sun J, Liang X-J. Future of nanotherapeutics: Targeting the cellular sub-organelles. Biomaterials [Internet]. 2016;97:10–21. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0142961216301375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parent M, Baradari H, Champion E, Damia C, Viana-Trecant M. Design of calcium phosphate ceramics for drug delivery applications in bone diseases: A review of the parameters affecting the loading and release of the therapeutic substance. J Control Release Off J Control Release Soc [Internet]. 2017;252:1–17. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28232225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Melville AJ, Rodríguez-Lorenzo LM, Forsythe JS. Effects of calcination temperature on the drug delivery behaviour of Ibuprofen from hydroxyapatite powders. J Mater Sci Mater Med [Internet]. 2008;19:1187–95. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17701302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Matsumoto T, Okazaki M, Inoue M, Yamaguchi S, Kusunose T, Toyonaga T, et al. Hydroxyapatite particles as a controlled release carrier of protein. Biomaterials [Internet]. 2004;25:3807–12. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15020156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lin K, Wu C, Chang J. Advances in synthesis of calcium phosphate crystals with controlled size and shape. Acta Biomater [Internet]. 2014;10:4071–102. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24954909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Uskoković V, Batarni SS, Schweicher J, King A, Desai TA. Effect of calcium phosphate particle shape and size on their antibacterial and osteogenic activity in the delivery of antibiotics in vitro. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces [Internet]. 2013;5:2422–31. Available from: http://files/1174/Uskoković et al - 2013 - Effect of calcium phosphate particle shape and siz.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Feng B, Weng J, Yang BC, Qu SX, Zhang XD. Characterization of surface oxide films on titanium and adhesion of osteoblast. Biomaterials [Internet]. 2003;24:4663–70. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0142961203003661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chou LYT, Ming K, Chan WCW. Strategies for the intracellular delivery of nanoparticles. Chem Soc Rev [Internet]. 2011;40:233–45. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20886124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kruger CA, Abrahamse H. Utilisation of targeted nanoparticle photosensitiser drug delivery systems for the enhancement of photodynamic therapy [Internet] Molecules. MDPI AG; 2018. [cited 2020 Apr 17]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30322132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ojea-Jimenez I, Comenge J, Garcia-Fernandez L, Megson Z, Casals E, Puntes V. Engineered Inorganic Nanoparticles for Drug Delivery Applications Curr Drug Metab. Bentham Science Publishers Ltd.; 2013;14:518–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Choi S-W, Kim J-H. Design of surface-modified poly(D,L-lactide-co-glycolide) nanoparticles for targeted drug delivery to bone. J Control Release. 2007;122:24–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ramanlal Chaudhari K, Kumar A, Megraj Khandelwal VK, Ukawala M, Manjappa AS, Mishra AK, et al. Bone metastasis targeting: A novel approach to reach bone using Zoledronate anchored PLGA nanoparticle as carrier system loaded with Docetaxel. J Control Release [Internet]. 2012. [cited 2020 Apr 17]; 158:470–8. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22146683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Salerno M, Cenni E, Fotia C, Avnet S, Granchi D, Castelli F, et al. Bone-Targeted Doxorubicin-Loaded Nanoparticles as a Tool for the Treatment of Skeletal Metastases Curr Cancer Drug Targets [Internet]. Bentham Science Publishers Ltd.; 2010. [cited 2020 Apr 17];10:649–59. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20578992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pignatello R, Sarpietro MG, Castelli F. Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of a New Polymeric Conjugate and Nanocarrier with Osteotropic Properties J Funct Biomater. MDPI AG; 2012;3:79–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Morton SW, Shah NJ, Quadir MA, Deng ZJ, Poon Z, Hammond PT. Osteotropic therapy via targeted layer-by-layer nanoparticles Adv Healthc Mater. Wiley-VCH Verlag; 2014;3:867–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Swami A, Reagan MR, Basto P, Mishima Y, Kamaly N, Glavey S, et al. Engineered nanomedicine for myeloma and bone microenvironment targeting Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A [Internet]. National Academy of Sciences; 2014. [cited 2020 Apr 17]; 111:10287–92. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24982170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rannevik G, Jeppsson S, Johnell O, Bjerre B, Laurell-Borulf Y, Svanberg L. A longitudinal study of the perimenopausal transition: altered profiles of steroid and pituitary hormones, SHBG and bone mineral density. Maturitas. 1995;21:103–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sowers MFR, Jannausch M, McConnell D, Little R, Greendale GA, Finkelstein JS, et al. Hormone predictors of bone mineral density changes during the menopausal transition. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:1261–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yokogawa K, Miya K, Sekido T, Higashi Y, Nomura M, Fujisawa R, et al. Selective delivery of estradiol to bone by aspartic acid oligopeptide and its effects on ovariectomized mice. Endocrinology. Department of Hospital Pharmacy, School of Medicine, Kanazawa University, Kanazawa 920-8641, Japan.; 2001;142:1228–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ishizaki J, Waki Y, Takahashi-Nishioka T, Yokogawa K, Miyamoto K. Selective drug delivery to bone using acidic oligopeptides. J Bone Miner Metab [Internet]. 2009;27:1–8. Available from: 10.1007/s00774-008-0004-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yang Y, Aghazadeh-Habashi A, Panahifar A, Wu Y, Bhandari KH, Doschak MR. Bone-targeting parathyroid hormone conjugates outperform unmodified PTH in the anabolic treatment of osteoporosis in rats Drug Deliv Transl Res [Internet]. Springer Verlag; 2017. [cited 2020 Apr 16];7:482–96. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28721611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bhandari K, Asghar W, Newa M, Jamali F, Doschak M. Evaluation of Bone Targeting Salmon Calcitonin Analogues in Rats Developing Osteoporosis and Adjuvant Arthritis Curr Drug Deliv. Bentham Science Publishers Ltd.; 2015;12:98–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gil L, Han Y, Opas EE, Rodan GA, Ruel R, Seedor JG, et al. Prostaglandin E2-bisphosphonate conjugates: Potential agents for treatment of osteoporosis. Bioorganic Med Chem. 1999;7:901–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.TSUSHIMA N, YABUKI M, HARADA H, KATSUMATA T, KANAMARU H, NAKATSUKA I, et al. Tissue Distribution and Pharmacological Potential of SM-16896, a Novel Oestrogen-bisphosphonate Hybrid Compound* J Pharm Pharmacol. Wiley; 2000;52:27–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tomatsu S, Montaño AM, Oikawa H, Giugliani R, Harmatz PR, Smith M, et al. Chapter 126 Impairment of Body Growth in Mucopolysaccharidoses. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Melbouci M, Mason RW, Suzuki Y, Fukao T, Orii T, Tomatsu S. Growth impairment in mucopolysaccharidoses Mol. Genet. Metab Academic Press Inc.; 2018. p. 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tomatsu S, Alméciga-Díaz CJ, Montaño AM, Yabe H, Tanaka A, Dung VC, et al. Therapies for the bone in mucopolysaccharidoses Mol. Genet. Metab. Academic Press Inc.; 2015. p. 94–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kecskemethy HH, Kubaski F, Harcke HT, Tomatsu S. Bone mineral density in MPS IV A (Morquio syndrome type A) Mol Genet Metab. Academic Press Inc.; 2016;117:144–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yasuda E, Suzuki Y, Shimada T, Sawamoto K, Mackenzie WG, Theroux MC, et al. Activity of daily living for Morquio A syndrome Mol Genet Metab. Academic Press Inc.; 2016; 118:111–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Doherty C, Stapleton M, Piechnik M, Mason RW, Mackenzie WG, Yamaguchi S, et al. Effect of enzyme replacement therapy on the growth of patients with Morquio A J Hum Genet. Nature Publishing Group; 2019;64:625–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yabe H, Tanaka A, Chinen Y, Kato S, Sawamoto K, Yasuda E, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for Morquio A syndrome Mol Genet Metab [Internet]. Academic Press Inc.; 2016. [cited 2020 Apr 17]; 117:84–94. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26452513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chinen Y, Higa T, Tomatsu S, Suzuki Y, Orii T, Hyakuna N. Long-term therapeutic efficacy of allogenic bone marrow transplantation in a patient with mucopolysaccharidosis IVA Mol Genet Metab Reports. Elsevier Inc.; 2014;1:31–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tomatsu S, Montão AM, Dung VC, Ohashi A, Oikawa H, Oguma T, et al. Enhancement of drug delivery: Enzyme-replacement therapy for murine morquio a syndrome Mol Ther. American Society of Gene & Cell Therapy; 2010;18:1094–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tomatsu S, Montaño AM, Ohashi A, Gutierrez MA, Oikawa H, Oguma T, et al. Enzyme replacement therapy in a murine model of Morquio A syndrome. Hum Mol Genet [Internet]. 2008;17:815–24. Available from: 10.1093/hmg/ddm353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Víctor Álvarez J, Bravo SB, García-Vence M, De Castro MJ, Luzardo A, Colón C, et al. Proteomic analysis in morquio a cells treated with immobilized enzymatic replacement therapy on nanostructured lipid systems Int J Mol Sci. MDPI AG; 2019;20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sawamoto K, González JVÁ, Piechnik M, Otero FJ, Couce ML, Suzuki Y, et al. Mucopolysaccharidosis IVA: Diagnosis, treatment, and management Int. J. Mol. Sci MDPI AG; 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nishioka T, Tomatsu S, Gutierrez MA, Miyamoto K, Trandafirescu GG, Lopez PLC, et al. Enhancement of drug delivery to bone: Characterization of human tissue-nonspecific alkaline phosphatase tagged with an acidic oligopeptide [Internet]. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2006. p. 244–55. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1096719206000758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Whyte MP. Hypophosphatasia: An overview For 2017 Bone. Center for Metabolic Bone Disease and Molecular Research, Shriners Hospital for Children, Division of Bone and Mineral Diseases, Department of Internal Medicine, Washington University School of Medicine at Barnes-Jewish Hospital, St. Louis, Missouri, USA.: Elsevier Inc; 2017;102:15–25.28238808 [Google Scholar]

- 71.Whyte MP. Hypophosphatasia: Enzyme Replacement Therapy Brings New Opportunities and New Challenges J Bone Miner Res [Internet]. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2017;32:667–75. Available from: 10.1002/jbmr.3075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mornet E Genetics of Hypophosphatasia. Clin Rev Bone Miner Metab [Internet]. 2013;11:71–7. Available from: 10.1007/s12018-013-9140-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Castells L, Cassanello P, Muñiz F, De Castro MJ, Couce ML. Neonatal lethal hypophosphatasia A case report and review of literature Med (United States). Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2018;97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Whyte MP, Habib D, Coburn SP, Tecklenburg F, Ryan LM, Fedde K, et al. Failure of hyper-phosphatasemia by intravenous infusion of purified placental alkaline phosphatase (ALP) to correct severe hypophosphatasia: Evidence against. JBone Miner Res. 1992;7. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Whyte MP, Landt M, Ryan LM, Mulivor RA, Henthorn PS, Fedde KN, et al. Alkaline phosphatase: placental and tissue-nonspecific isoenzymes hydrolyze phosphoethanolamine, inorganic pyrophosphate, and pyridoxal 5’-phosphate. Substrate accumulation in carriers of hypophosphatasia corrects during pregnancy. J Clin Invest. Metabolic Research Unit, Shriners Hospital for Crippled Children, St. Louis, Missouri 63131, USA.; 1995;95:1440–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Whyte MP, Magill HL, Fallon MD, Herrod HG. Infantile hypophosphatasia: normalization of circulating bone alkaline phosphatase activity followed by skeletal remineralization. Evidence for an intact structural gene for tissue nonspecific alkaline phosphatase J Pediatr. United States; 1986;108:82–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mornet E. Hypophosphatasia Metabolism. Unite de Genetique Constitutionnelle, Service de Biologie, Centre Hospitalier de Versailles, 177 rue de Versailles, 78150 Le Chesnay, France. Electronic address: emornet@ch-versailles.fr: Elsevier Inc; 2018;82:142–55.28939177 [Google Scholar]

- 78.Millan JL, Whyte MP. Alkaline Phosphatase and Hypophosphatasia. Calcif Tissue Int. Sanford Children’s Health Research Center, Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute, La Jolla, CA, 92037, USA. millan@burnham.org; Center for Metabolic Bone Disease and Molecular Research, Shriners Hospital for Children, St. Louis, MO, 63110, U; 2016;98:398–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Nakano C, Kitabatake Y, Takeyari S, Ohata Y, Kubota T, Taketani K, et al. Genetic correction of induced pluripotent stem cells mediated by transcription activator-like effector nucleases targeting ALPL recovers enzyme activity and calcification in vitro Mol Genet Metab [Internet], Academic Press Inc.; 2019. [cited 2020 Apr 20]; 127:158–65. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31178256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Matsumoto T, Miyake K, Yamamoto S, Orimo H, Miyake N, Odagaki Y, et al. Rescue of severe infantile hypophosphatasia mice by AAV-mediated sustained expression of soluble alkaline phosphatase. Hum Gene Ther. Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Nippon Medical School, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 113-8602, Japan.; 2011;22:1355–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Nakamura-Takahashi A, Miyake K, Watanabe A, Hirai Y, Iijima O, Miyake N, et al. Treatment of hypophosphatasia by muscle-directed expression of bone-targeted alkaline phosphatase via self-complementary AAV8 vector [Internet]. Mol. Ther. - Methods Clin. Dev 2016. p. 15059 Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2329050116301498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yamamoto S, Orimo H, Matsumoto T, Iijima O, Narisawa S, Maeda T, et al. Prolonged survival and phenotypic correction of Akp2−/− hypophosphatasia mice by lentiviral gene therapy J Bone Miner Res [Internet]. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2011;26:135–42. Available from: 10.1002/jbmr.201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ikeue R, Nakamura-Takahashi A, Nitahara-Kasahara Y, Watanabe A, Muramatsu T, Sato T, et al. Bone-Targeted Alkaline Phosphatase Treatment of Mandibular Bone and Teeth in Lethal Hypophosphatasia via an scAAV8 Vector [Internet], Mol. Ther. - Methods Clin. Dev 2018. p. 361–70. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2329050118300810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nakamura-Takahashi A, Tanase T, Matsunaga S, Shintani S, Abe S, Nitahara-Kasahara Y, et al. High-Level Expression of Alkaline Phosphatase by Adeno-Associated Virus Vector Ameliorates Pathological Bone Structure in a Hypophosphatasia Mouse Model. Calcif Tissue Int. Department of Pharmacology, Tokyo Dental College, 2-9-18, Kandamisaki-cho, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo, 101-0061, Japan. atakahashi@tdc.ac.jp.; Tokyo Dental College Research Branding Project, Tokyo Dental College, Tokyo, Japan. atakahashi@tdc.ac.jp.; Department of ; 2020; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sun X, Guo Q, Wei W, Robertson S, Yuan Y, Luo X. Current Progress on MicroRNA-Based Gene Delivery in the Treatment of Osteoporosis and Osteoporotic FractureDufau ML, editor. Int J Endocrinol [Internet]. Hindawi; 2019;2019:6782653 Available from: 10.1155/2019/6782653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yang Y-S, Xie J, Wang D, Kim J-M, Tai PWL, Gravallese E, et al. Bone-targeting AAV-mediated silencing of Schnurri-3 prevents bone loss in osteoporosis. Nat Commun [Internet]. 2019; 10:2958 Available from: 10.1038/s41467-019-10809-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]