Abstract

Background.

White matter hyperintensities (WMH) are a radiological marker of brain health that has been associated with language status in post-stroke aphasia; however, its association with language treatment outcomes remains unknown.

Objective.

To determine whether WMH in the right hemisphere (RH) predict response to language therapy independently from demographics and stroke lesion-related factors in post-stroke aphasia.

Methods.

We used the Fazekas scale to rate WMH in the RH in 30 patients with post-stroke aphasia who received language treatment. We developed ordinal regression models to examine language treatment effects as a function of WMH severity after controlling for aphasia severity, stroke lesion volume, time post onset, age and education level. We also evaluated associations between WMH severity and both pre-treatment naming ability and executive function.

Results.

The severity of WMH in the RH predicted treatment response independently from demographic and stroke-related factors such that patients with less severe WMH exhibited better treatment outcome. WMH scores were not significantly correlated with pre-treatment language scores, but they were significantly correlated with pre-treatment scores of executive function.

Conclusion.

We suggest that the severity of WMH in the RH is a clinically relevant predictor of treatment response in this population.

Keywords: white matter hyperintensities, leukoaraiosis, stroke, aphasia, language treatment, small vessel disease

Introduction

Aphasia, the loss or impairment of language function due to brain damage, affects one third of stroke survivors1 leading to poor functional communication and quality of life2. Although aphasia recovery occurs even in the chronic phase3 and despite the effectiveness of language therapy4, not all people with post-stroke aphasia (PWA) improve after therapy5.

The prediction of aphasia recovery has largely focused on left hemisphere lesion-related factors including lesion size and location6 and pre-treatment cognitive skills7. However, the integrity of the brain tissue spared by the stroke may contribute to neural plasticity and influence treatment response independently of left hemisphere damage8. White matter hyperintensities of presumed vascular origin (WMH) is a relevant radiological marker of brain health. WMH severity has been associated with aging and cognitive impairment9,10 and language status in post-stroke aphasia, although relevant evidence in this group is limited11–13.

Here, we sought to determine whether WMH in the right hemisphere (RH) predicts response to language therapy in post-stroke aphasia independently from demographics and stroke-related factors. We hypothesized that WMH severity in the RH would predict treatment gains, after controlling for age and education, aphasia severity, left hemisphere stroke lesion volume (i.e., lesion volume hereafter), and time post onset. We also hypothesized that WMH severity in the RH would not be associated with stroke-related measures (i.e., lesion volume, time post onset and aphasia severity) and pre-treatment naming performance. The rationale is that WMH are an MRI marker of small vessel disease14 which can be indicative of the brain state prior to stroke, whereas stroke-related measures and pre-treatment naming performance reflect post-stroke effects in the affected hemisphere. Finally, several population-based studies have provided clear evidence that WMH are related to cognitive impairment, particularly to reductions in information processing speed and executive dysfunction10,15–17. This is probably because WMH may cause secondary loss of communication between critical cortical regions leading to subsequent loss in function15,18. WMH have also been associated with worse cognitive performance and recovery after stroke19,20. Based on this literature, we expected WMH in the RH to be associated with pre-treatment non-verbal executive function in PWA.

Methods

Participants

The study included a retrospective sample of 30 participants (10 female; mean age = 61 ± 10.73 years; mean education level = 15 ± 2.11 years) with persistent aphasia following a single left hemisphere stroke (time post-stroke onset = 52 ± 50.12 months). No participant reported major psychiatric disorders, neurological disease other than stroke, or any active medical condition that precluded participation. They all primarily spoke English and had normal or corrected-to-normal vision and adequate hearing. All participants provided informed consent to undergo study procedures approved by the Boston University and Massachusetts General Hospital Institutional Review Boards.

Language assessments and treatment

Prior and after treatment, participants completed language standardized assessments including the Western Aphasia Battery-Revised (WAB-R) to determine aphasia type and overall language severity (aphasia quotient, AQ)21, the Boston Naming Test (BNT)22, and the Pyramids and Palm Trees Test (PAPT)23 to assess picture naming and semantic processing respectively. The subtests symbol trails, mazes, and design generation of the Cognitive-Linguistic Quick Test (CLQT)24 were also administered to generate a composite score of non-verbal executive function.

Participants received semantic feature analysis treatment25 for up to 12 weeks. They attended up to 24 two-hour treatment sessions either two or three times per week or until they reached ≥ 90% accuracy on two consecutive weekly probes tracking change in naming throughout treatment. Treatment effects were determined by calculating individual proportion of potential maximal gain (PMG) with the following formula: [(mean post-treatment score – mean pretreatment score)/(total number of trained items – mean pre-treatment score)]. PMG has been utilized in previous research26 including prior reports on the same patient cohort27,28. Further assessment and treatment protocol details are available elsewhere27,28.

Participants’ demographics as well as stroke and WMH lesion data and behavioural data are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic, behavioral and stroke and WMH lesion data for all PWA.

| ID | Sex | Hand. | Age | Edu. | MPO | Lesion Volume (cc) | WAB-R AQ | Aphasia type | BNT | PAPT | Executive Function | PMG | PVWMH | DWMH | DWMH count | WMH global load | WMH Count-based load |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | M | R | 55 | 16 | 12 | 57.246 | 87.2 | Anomic | 50 | 50 | 22 | 0.89 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| P2 | F | L | 50 | 13 | 29 | 249.934 | 25.2 | Global | 1 | 49 | 21 | 0.00 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| P3 | F | R | 63 | 12 | 62 | 175.378 | 52 | Conduction | 10 | 46 | 17 | 0.36 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 6 |

| P4 | M | R | 79 | 16 | 13 | 84.778 | 74.1 | Conduction | 52 | 49 | 22 | 1.00 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| P5 | M | R | 67 | 18 | 8 | 171.944 | 30.8 | Wernicke’s | 4 | 48 | 17 | −0.07 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 8 |

| P6 | M | R | 49 | 16 | 113 | 298.967 | 66.6 | Broca | 44 | 42 | 26 | 0.74 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| P7 | M | R | 55 | 16 | 137 | 181.973 | 48 | Broca’s | 6 | 50 | 21 | 0.27 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 6 |

| P8 | M | R | 49 | 12 | 52 | 87.587 | 82.8 | Anomic | 51 | 48 | 25 | 1.00 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| P9 | F | R | 71 | 16 | 37 | 11.66 | 95.2 | Anomic | 45 | 50 | 23 | 0.83 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| P10 | F | R | 53 | 16 | 12 | 76.553 | 80.4 | Anomic | 37 | 49 | 22 | 0.83 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 5 |

| P11 | M | R | 78 | 18 | 22 | 32.114 | 92.1 | Anomic | 41 | 49 | 15 | 0.39 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| P12 | M | R | 68 | 12 | 104 | 186.845 | 40 | Broca’s | 1 | 46 | 21 | 0.03 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| P13 | M | L | 42 | 13.5 | 18 | 12.131 | 92.7 | Anomic | 43 | 49 | 25 | 0.98 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| P14 | F | R | 64 | 13 | 24 | 96.932 | 64.4 | Broca’s | 41 | 49 | 22 | 0.77 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| P15 | F | R | 71 | 12 | 74 | 189.309 | 87.2 | Anomic | 43 | 44 | 7 | 0.28 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 8 |

| P16 | M | R | 49 | 12 | 70 | 317.071 | 33.6 | Broca’s | 1 | 41 | 29 | 0.00 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| P17 | M | R | 61 | 16 | 152 | 163.488 | 74.3 | Anomic | 54 | 51 | 24 | 0.98 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| P18 | F | R | 70 | 16 | 152 | 69.643 | 78 | Anomic | 24 | 50 | 15 | 0.76 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 8 |

| P19 | M | R | 80 | 18 | 22 | 89.026 | 28.9 | Broca’s | 1 | 43 | 23 | 0.22 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| P20 | F | R | 48 | 16 | 14 | 164.327 | 13 | Broca’s | 0 | 40 | 16 | 0.42 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| P21 | M | R | 65 | 18 | 16 | 247.593 | 11.7 | Broca’s | 0 | 43 | 17 | 0.06 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 7 |

| P22 | M | R | 62 | 16 | 12 | 100.019 | 65.4 | Transcortial Motor |

1 | 37 | 16 | 0.11 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 7 |

| P23 | M | R | 60 | 16 | 24 | 172.812 | 45.2 | Wernice’s | 6 | 42 | 16 | 0.04 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| P24 | M | R | 69 | 16 | 170 | 183.449 | 40.4 | Broca’s | 3 | 49 | 25 | 0.14 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| P25 | F | R | 76 | 18 | 33 | 184.39 | 37.5 | Broca’s | 2 | 34 | 6.5 | 0.06 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 9 |

| P26 | F | R | 64 | 12 | 115 | 127.704 | 58 | Broca’s | 15 | 48 | 7 | 0.20 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 8 |

| P27 | M | R | 65 | 12 | 17 | 34.148 | 84.3 | Anomic | 41 | 50 | 23 | 0.63 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 6 |

| P28 | M | R | 62 | 12 | 15 | 76.654 | 56 | Broca’s | 21 | 49 | 21 | 0.42 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| P29 | M | R | 40 | 16 | 26 | 26.221 | 90.1 | Anomic | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 0.23 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| P30 | M | R | 59 | 14 | 29 | 186.52 | 60 | Broca’s | 16 | 51 | 25 | 0.37 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| AVG | 61.47 | 14.92 | 52.80 | 135.21 | 59.84 | 22.55 | 46.41 | 19.64 | 0.43 | 1.83 | 1.17 | 1.53 | 3 | 4.53 | |||

| SD | 10.74 | 2.21 | 50.13 | 82.41 | 24.97 | 20.54 | 9.53 | 6.68 | 0.36 | 0.70 | 0.83 | 1.20 | 1.34 | 2.42 | |||

Hand. Handedness, Edu. Education, M male, F female, L left-handed, R right-handed, MPO months post onset, WAB-R AQ Western Aphasia Battery-Revised Aphasia Quotient, BNT Boston Naming Test, PAPT Pyramids and Palm Trees Test, PMG Proportion of potential maximal gain, PVWMH periventricular white matter hyperintensities, DWMH deep white matter hyperintensities, WMH white matter hyperintensities, AVG average, SD standard deviation

MRI data acquisition and analysis

Imaging data were collected just before the beginning of treatment at the Athinoula A. Martinos Center in Charlestown, MA, USA on a 3T Siemens Trio Tim MRI scanner using a 20-channel head and neck coil. The MRI protocol included a high resolution T1-weighted 3D sagittal volume (parameters: TR/TE = 2300/2.91 msec, T1 = 900 msec, flip angle = 9°, matrix = 256 × 256 mm, slice thickness = 1 mm3, 176 sagittal slices) and a T2-FLAIR 2D axial volume sequence (parameters: TR/TE/TI = 9000/90/2500 msec, matrix = 220 mm, FOV = 220 mm, slice thickness = 5 mm with 0 mm gap, 35 slices, with a parallel imaging acceleration factor of 2).

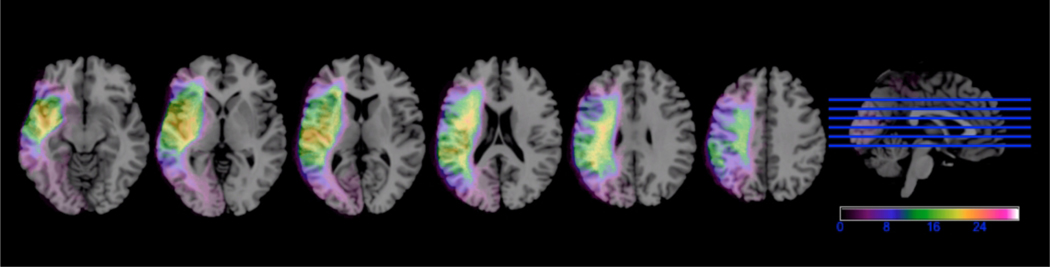

Lesion maps were manually drawn slice-by-slice on T1 structural images by trained research assistants blinded to patient’s behavioural scores using MRIcron (www.mccauslandcenter.sc.edu/crnl/mricron/) (see Figure 1 for a lesion overlay map for all participants). Lesion maps and T1-weighted images were normalized to MNI space using SPM12. Normalized lesion maps were filtered at 50% and lesion volumes were calculated using in-house Matlab scripts28.

Figure 1. Left hemisphere lesion overlay map for all 30 PWA.

The heat colors represent higher number of PWA with overlapping lesions. Left hemisphere is presented on the left.

WMH in the RH were defined following the recent STandards for Reporting Vascular changes on nEuroimaging (STRIVE)14 as signal abnormality of variable size in the white matter that shows hyperintensity on T2-FLAIR weighted images without cavitation. T2-FLAIR images were rated for WMH severity in the right hemisphere only, using the Fazekas scale29. Periventricular WMH (PWMH) were graded as 0 (absent), 1 (caps or pencil-thin periventricular lining), 2 (smooth haloing or thick lining) and 3 (irregular WMH extending into the deep white matter). Deep WMH (DWMH) were graded as 0 (absent), 1 (small punctate or nodular lesions), 2 (beginning confluent lesions) and 3 (confluent lesions). The number of DWMH lesions (DWMH count) was also computed for a more fine-grained quantitative approach. Following previous literature, two composite scores were calculated to capture overall WMH burden: (a) WMH global load (PVWMH score + DWMH score), and (b) WMH count-based load score (PVWMH score + DWMH score + DWMH count score1). These composite scores allow assessing the total severity and extent of WMH in the hemisphere of interest (see Table 1 for individual patients’ rating scores). Scans were rated by the first and second author achieving high interrater reliability (Cohen’s κ: PVWMH = 0.79, DWMH = 0.90, DWMH count = 0.95). Rating discrepancies were resolved by the third author.

Statistical analyses

PMG was the dependent treatment outcome variable. Because PMG scores were not normally distributed (see Supplemental Figure 1), they were divided into quartiles as done in previous research 12,30,31 resulting in meaningful groups (i.e., low to high gradient of treatment response) for statistical analyses. WMH scores were dichotomized into absent-mild and moderate-to-severe as follows: PVWMH: absent-mild = 0–1, moderate-to-severe = 2–3; DWMH: absent-mild = 0–1, moderate-to-severe = 2–3; DWMH count: absent-mild = 0–1, moderate-to-severe = 2–3; WMH global load: absent-mild = 1–2, moderate-to-severe = 3–6; WMH count-based load: absent-mild = 1–4, moderate-to-severe = 5–9.

Five multivariable ordinal regression models evaluated the effects of WMH in the RH on language treatment outcomes (i.e., one model for each WMH score). In all models, age, education, time post onset, total lesion volume and aphasia severity were included as covariates to assess whether WMH predict treatment outcomes independently from demographics and stroke-related factors. Spearman correlations between WMH and both BNT and CLQT scores assessed the relationship between WMH severity and pre-treatment naming and non-verbal executive function. Raw scores were used in all correlation analyses.

Results

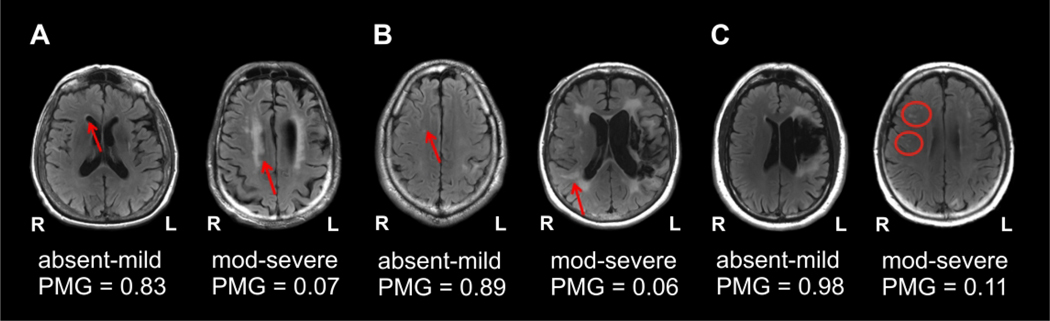

The participants’ demographics, time post onset, aphasia severity, lesion volume, PMG scores, and WMH ratings in the RH are reported according to PMG quartiles on Table 2. Multivariate analyses were conducted after excluding collinearity (see Supplemental Table 1 for univariate analyses showing non-significant correlations between WMH scores and covariates: age, education, time post onset, total lesion volume, aphasia severity). Importantly, Models 2 and 3 (Table 3) revealed that both deep WMH scores (i.e., DWMH and DWMH count respectively) were significant predictors of PMG scores. Specifically, PWA with more severe DWMH and more lesions, presented with lower odds of belonging to a higher PMG quartile (i.e., better response to treatment) compared to PWA with absent-to-mild DWMH and fewer lesions, after controlling for stroke-related and demographic factors. When considering total WMH burden, both composite scores (i.e., WMH global load and WMH count-based load) were also significant predictors of PMG (Models 4 and 5 respectively) with higher composite scores being associated with lower odds of belonging to a higher PMG quartile compared to lower scores (see Figure 2 A–C for example cases). Also, stroke-related factors but not demographic factors were associated with PMG scores. Aphasia severity was a significant predictor of PMG in all models such that higher WAB-AQ scores (i.e., lower aphasia severity) were associated with higher odds of belonging to a higher PMG quartile relative to lower WAB-AQ scores. Lesion volume was a significant predictor in Model 4 only, indicating that PWA with larger lesions had lower odds of being in a higher PMG quartile compared to PWA with smaller lesions.

Table 2.

Median and range of demographics, aphasia severity, PMG, and WMH ratings per PMG quartile.

| 1st PMG quartile (lowest) n = 8 (6 male) | 2nd PMG quartile n = 7 (4 male) | 3rd PMG quartile n = 8 (5 male) | 4th PMG quartile (highest) n = 7 (5 male) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | Range | Median | Range | Median | Range | Median | Range | |

| PVWMH | 2 | 1 – 3 | 2 | 1 – 3 | 1.5 | 1 – 3 | 2 | 1 – 2 |

| DWMH | 1.5 | 0 – 3 | 1 | 0 – 2 | 1 | 1 – 2 | 1 | 0 – 2 |

| DWMH count | 2 | 0 – 3 | 3 | 0 – 3 | 1 | 1 – 3 | 1 | 0 – 2 |

| WMH global load | 3 | 1 – 5 | 3 | 1 – 5 | 3 | 2 – 5 | 2 | 1 – 4 |

| WMH count-based load | 5 | 1 – 9 | 6 | 1 – 8 | 4 | 3 – 8 | 3 | 1 – 6 |

| Age (years) | 63.5 | 49 – 76 | 64 | 40 – 80 | 63 | 49 – 78 | 55 | 42 – 79 |

| Education (years) | 16 | 12 – 18 | 16 | 12 – 18 | 15 | 12 – 18 | 16 | 12 – 16 |

| MPO | 26.5 | 8 – 104 | 74 | 22 – 170 | 23 | 14 – 152 | 18 | 12 – 152 |

| Lesion volume (cm3) | 185.61 | 100.01 – 317.07 | 175.37 | 26.22 – 189.3 | 86.79 | 32.11 – 298.96 | 76.55 | 11.66 – 163.48 |

| WAB-R AQ (%) | 35.55 | 11.7 – 65.4 | 52 | 28.9 – 90.1 | 65.5 | 13 – 92.1 | 82.8 | 74.1 – 95.2 |

| PMG | 0.035 | −0.07 – 0.11 | 0.23 | 0.14 – 0.36 | 0.52 | 0.37 – 0.77 | 0.98 | 0.83 – 1 |

PVWMH periventricular white matter hyperintensities, DWMH deep white matter hyperintensities, WMH white matter hyperintensities, MPO months post onset, WAB-R AQ Western Aphasia Battery-Revised Aphasia Quotient, PMG proportion of potential maximal gain

Table 3.

Results of ordinal regressions.

| Odds Ratio | 95% | Conf. Interval | Std. Error | z | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | ||||||

| PVWMH | 0.59 | 0.11 | 2.92 | 0.48 | −0.64 | 0.52 |

| WAB-R AQ | 1.05 | 1.00 | 1.10 | 0.02 | 2.28 | 0.02 |

| MPO | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.01 | 0.007 | 0.65 | 0.51 |

| Total lesion volume | 0.99 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 7.32e-06 | −1.75 | 0.08 |

| Age | 0.94 | 0.85 | 1.03 | 0.04 | −1.27 | 0.20 |

| Education | 1.11 | 0.78 | 1.56 | 0.19 | 0.61 | 0.54 |

| Model 2 | ||||||

| DWMH | 0.11 | 0.01 | 0.79 | 0.11 | −2.20 | 0.02 |

| WAB-R AQ | 1.07 | 1.01 | 1.12 | 0.02 | 2.59 | 0.01 |

| MPO | 1.00 | 0.98 | 1.02 | 0.008 | 0.65 | 0.51 |

| Total lesion volume | 0.99 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 7.40e-06 | −1.73 | 0.08 |

| Age | 0.96 | 0.87 | 1.06 | 0.04 | −0.77 | 0.44 |

| Education | 1.07 | 0.74 | 1.55 | 0.20 | 0.41 | 0.68 |

| Model 3 | ||||||

| DWMH count | 0.11 | 0.01 | 0.69 | 0.10 | −2.35 | 0.01 |

| WAB-R AQ | 1.06 | 1.01 | 1.11 | 0.02 | 2.44 | 0.01 |

| MPO | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.02 | 0.008 | 0.99 | 0.32 |

| Total lesion volume | 0.99 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 7.46e-06 | −1.86 | 0.06 |

| Age | 0.96 | 0.87 | 1.05 | 0.04 | −0.79 | 0.43 |

| Education | 0.98 | 0.67 | 1.43 | 0.19 | −0.09 | 0.92 |

| Model 4 | ||||||

| WMH global load | 0.15 | 0.02 | 1.02 | 0.14 | −1.94 | 0.05 |

| WAB-R AQ | 1.06 | 1.01 | 1.11 | 0.02 | 2.61 | 0.009 |

| MPO | 1.00 | 0.98 | 1.01 | 0.007 | 0.51 | 0.60 |

| Total lesion volume | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 7.90e-06 | −2.00 | 0.04 |

| Age | 0.94 | 0.86 | 1.04 | 0.04 | −1.05 | 0.29 |

| Education | 1.05 | 0.73 | 1.51 | 0.19 | 0.27 | 0.78 |

| Model 5 | ||||||

| WMH count-based load | 0.19 | 0.03 | 0.98 | 0.15 | −1.98 | 0.04 |

| WAB-R AQ | 1.06 | 1.01 | 1.11 | 0.02 | 2.45 | 0.01 |

| MPO | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.02 | 0.007 | 0.82 | 0.41 |

| Total lesion volume | 0.99 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 7.40e-06 | −1.84 | 0.06 |

| Age | 0.94 | 0.86 | 1.04 | 0.04 | −1.05 | 0.29 |

| Education | 1.04 | 0.72 | 1.49 | 0.19 | 0.21 | 0.83 |

PVWMH periventricular white matter hyperintensities, DWMH deep white matter hyperintensities, WMH white matter hyperintensities, WAB-R AQ Western Aphasia Battery-Revised Aphasia Quotient, MPO months post onset

Figure 2. Examples of the association between WMH and treatment outcomes.

Panels A-C present the MRI scans (radiological convention) of six PWA showing from left to right, that absent-mild WMH are associated with higher PMG scores whereas moderate-severe WMH are associated with worse PMG scores across all three classifications of WMH lesions: periventricular WMH (A), deep WMH (B) and deep WMH lesion count (i.e., based on the number of lesions) (C).

WMH scores were not significantly correlated with pre-treatment naming scores although they were significantly correlated with pre-treatment scores of executive function. Post-hoc correlations showed that executive function scores were not significantly associated with total lesion volume, aphasia severity and performance on the BNT but they were significantly correlated with both PMG raw scores and PMG quartiles (Table 4).

Table 4.

Results of correlation analyses B: Spearman’s Rho values.

| Executive function | WAB-R AQ | BNT | PMG | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total lesion volume | −0.01 | −0.69 (p<0.0001) | −0.52 (p=0.003) | −0.61 (p=0.0003) |

| Executive function | - | 0.17 | 0.31 | 0.36 (p=0.5) |

| WAB-R AQ | - | - | 0.85 (p<0.0001) | 0.69 (p<0.0001) |

| BNT | - | - | - | 0.83 (p<0.0001) |

P values are provided in parenthesis when statistically significant.

WAB-R AQ Western Aphasia Battery-Revised Aphasia Quotient, BNT Boston Naming Test, PMG proportion of potential maximal gain

Discussion

Our main findings revealed that the severity of WMH in the RH, particularly deep WMH, predicted language treatment outcome in PWA independently from demographic factors and stroke-related factors. Furthermore, WMH in the RH were not associated with stroke-related measures, including time post onset and lesion volume, which is not unexpected given that WMH reflects a chronic degenerative process unrelated to stroke insult. These results are consistent with prior research showing that WMH in the noninfarcted hemisphere can predict post-stroke naming outcomes12 and longitudinal changes in aphasia severity13. While these studies highlight the critical role of WMH in language recovery, no previously published research has examined their impact on treatment-induced recovery in post-stroke aphasia. Our study provides initial evidence that WMH also play a critical role in modulating treatment-dependent recovery in post-stroke aphasia beyond the effects of stroke on language brain regions in the left hemisphere.

A number of potential mechanisms might explain the association between WMH and treatment response in our cohort. WMH are a well-established neuroimaging biomarker of progressive small vessel disease related to cumulative brain damage and associated cognitive impairment29,32. The presumed underlying pathophysiology is reduced microscopic white matter connectivity leading to a loss of communication between different cortical regions via long white matter tract damage18,32 and hence loss of function15. Therefore, their presence and severity could index the overall status of brain health signalling the integrity of brain tissue beyond the stroke lesion12. Crucially, language reorganization and neural plasticity in post-stroke aphasia rely on the integrity of bilateral white matter tracts8 and treatment success has been associated with increased reliance on perilesional or spared brain regions in one or both hemispheres18,33. Therefore, increased WMH burden may negatively impact treatment outcomes by reducing global network connectivity and efficiency34 and disrupting white matter connections between key regions that sustain language-specific and domain-general processes shown to support language recovery33.

In line with this interpretation, our findings revealed that WMH in the RH (both DWMH and PVWMH) were associated with non-verbal executive function at pre-treatment which was further associated with PMG scores reflecting direct treatment outcomes. These results align with previous evidence for the detrimental effects of WMH on executive function and other aspects of domain-general cognition in stroke-fee individuals10,15,35,36 and individuals with other neurological conditions37, as well as the association between pre-treatment executive function scores and anomia therapy outcomes in PWA26. As in prior research13, we did not find a relationship between WMH in the RH and pre-treatment aphasia severity or pre-treatment language scores. Although more recent research has provided evidence for such association38, the contrast in findings across studies might be related to differences in sample size and WMH severity between patient cohorts and require further investigation. Altogether, our findings suggest that the cumulative effects of WMH on otherwise stroke-spared brain tissue in post-stroke aphasia may lead to poor therapy outcomes by decreasing neural and cognitive resources that are essential for recovery, thus reducing their functionality and availability to support improvement during language treatment.

Of note, although PWMH were accounted for in the composite scores reflecting overall WMH burden, they were not a significant independent predictor of treatment response. This is in agreement with the suggestion that distinct WMH patterns have differing pathogenesis, risk factors, effects on the brain and hence clinical consequences39. Indeed, postmortem MRI-histopathological studies suggest that each type of WMH reflects distinct neuropathological changes and severity. In brief, higher DWMH load is associated with increasing severity of demyelination and axonal damage, hence more severe disconnection and microstructural damage, compared to PWMH39.

Studying the role of WMH on treatment-induced recovery in aphasia has important clinical implications40. Our findings contribute to our current understanding of relevant anatomical factors that modulate treatment response in aphasia, that have been otherwise traditionally focused on just patient-related and stroke-related factors6. Determining relevant predictors of therapy outcome can inform individual prognosis, treatment planning and prompt allocation of additional care and support resources. Importantly, the detection of high WMH severity in poor-responders to treatment can help identifying PWA at risk for cognitive decline in order to track their long-term language and cognitive status and consider additional neuropsychological stimulation in their rehabilitation programs.

Despite the cross-sectional nature of our study, it is worth considering that the accumulation of WMH over time can lead to long-term negative cognitive effects. Both population-based and hospital-based cohort studies indicate that the progression of WMH is related to a parallel decline in cognitive function and a considerable risk of developing dementia10,40–42. Given the high prevalence of WMH in the older adult population and their relationship with cognitive function and recovery in PWA, we argue that WMH should be identified and assessed for prognostic purposes. Longitudinal studies capturing the progression of WMH in PWA after stroke may provide further insights into the relationship between WMH and responsiveness to language therapy.

A few limitations in the present study should be considered for future research. We evaluated WMH in the RH using the Fazekas scale, a validated and widely used metric in the small vessel disease field of research43. While visual rating scales provide limited measurements of WMH, they have excellent intraobserver and interobserver agreement, they can be readily used in clinical settings, and scores on this scale closely correlate with WMH volumetric assessments43. In addition our predefined cut-off used for the distinction between absent-mild vs. moderate-severe WMH in different locations (i.e., PVWMH and DWMH) was sensitive enough to capture the topographic differences and independent associations consistently across different statistical models. Advanced volumetric methods adapted to measure WMH in patients with large stroke lesions could be used to obtain exact WMH volumes and localization. These metrics may allow to identify more subtle associations between WMH and treatment outcomes, and to examine regional variability in WMH location by assessing the relationship between the specific topography of WMH and cognitive impairment as done in prior research with other populations44,45. Our findings require further replication with larger samples to rule out the possibility of selection bias and with patient cohorts receiving different types of treatment to ensure generalization of our findings. Also, future research should examine other neuroanatomical markers of small vessel disease to evaluate its overall effects on therapy response in PWA as a whole-brain disorder18. Finally, due to the retrospective nature of our study, we could not control for the time-post-onset at which treatment was initiated across patients. Although all PWA were in the chronic phase of stroke and time-post-onset was included in our models as a confound variable, the range of time-post-onset at which therapy was initiated is broad in our cohort, which may affect the magnitude of treatment responsiveness, especially in more chronic patients. Future research should examine the relationship between WMH severity and response to language therapy in more homogeneous cohorts in this respect and at time points closer to the stroke event.

Conclusions

Our findings indicate that WMH in the RH can predict treatment-induced recovery in post-stroke aphasia independently from well-established individual-dependent and stroke-related factors and suggest that WMH burden may impact the availability of neural and cognitive resources that support language improvement. We support the use of WMH of presumed vascular origin on MRI, as a proxy of neural tissue integrity and overall brain health that should be further studied as a neuroanatomical marker of language recovery in intervention trials and general aphasia research.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all participants for their time and commitment to this study.

Funding

This study has been supported by the Dudley Allen Sargent Research Fund of Boston University, post-doctoral grant awarded to Maria Varkanitsa and Claudia Peñaloza and by NIH/NIDCD grant P50DC012283 (Center for the Neurobiology of Language Recovery).

Footnotes

Both DWMH metrics were included to account for cases with mild DWMH and several lesions (i.e., severe DWMH count) and cases with severe DWMH and fewer lesions (i.e., mild DWMH count).

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

Swathi Kiran serves as a consultant for The Learning Corporation with no scientific overlap with the present study.

References

- 1.Engelter ST, Gostynski M, Papa S, et al. Epidemiology of aphasia attributable to first ischemic stroke: Incidence, severity, fluency, etiology, and thrombolysis. Stroke. 2006;37(6):1379–1384. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000221815.64093.8c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hilari K, Needle JJ, Harrison KL. What Are the Important Factors in Health-Related Quality of Life for People With Aphasia? A Systematic Review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;93(1):S86-S95.e4. doi: 10.1016/J.APMR.2011.05.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holland A, Fromm D, Forbes M, MacWhinney B. Long-term Recovery in Stroke Accompanied by Aphasia: A Reconsideration. Aphasiology. 2017;31(2):152–165. doi: 10.1080/02687038.2016.1184221.Long-term [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brady M, Kelly H, Godwin J, Enderby P, Campbell P. Speech and language therapy for aphasia following stroke In: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2016. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laganaro M, Di Pietro M, Schnider A. Computerised treatment of anomia in acute aphasia: Treatment intensity and training size. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2006;16(6):630–640. doi: 10.1080/09602010543000064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Plowman E, Hentz B, Ellis C. Post-stroke aphasia prognosis: A review of patient-related and stroke-related factors. J Eval Clin Pract. 2012;18(3):689–694. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2011.01650.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gilmore N, Meier EL, Johnson JP, Kiran S. Nonlinguistic Cognitive Factors Predict Treatment-Induced Recovery in Chronic Poststroke Aphasia. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2019;100(7):1251–1258. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2018.12.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Forkel SJ, De Schotten MT, Dell’Acqua F, et al. Anatomical predictors of aphasia recovery: A tractography study of bilateral perisylvian language networks. Brain. 2014;137(7):2027–2039. doi: 10.1093/brain/awu113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Habes M, Erus G, Toledo JB, et al. White matter hyperintensities and imaging patterns of brain ageing in the general population. Brain. 2016;139(4):1164–1179. doi: 10.1093/brain/aww008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prins ND, Scheltens P. White matter hyperintensities, cognitive impairment and dementia: An update. Nat Rev Neurol. 2015;11(3):157–165. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2015.10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flowers HL, Alharbi MA, Mikulis D, et al. MRI-Based Neuroanatomical Predictors of Dysphagia, Dysarthria, and Aphasia in Patients with First Acute Ischemic Stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis Extra. 2017;7:21–34. doi: 10.1159/000457810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wright A, Tippett D, Saxena S, et al. Leukoaraiosis is independently associated with naming outcome in poststroke aphasia. Neurology. 2018;91:526–532. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000005945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Basilakos A, Stark BC, Johnson L, et al. Leukoaraiosis Is Associated With a Decline in Language Abilities in Chronic Aphasia. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2019;33(9):718–729. doi: 10.1177/1545968319862561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wardlaw JM, Smith EE, Biessels GJ, et al. Neuroimaging standards for research into small vessel disease and its contribution to ageing and neurodegeneration. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(8):822–838. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70124-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Langen CD, Cremers LGM, De Groot M, et al. Disconnection due to white matter hyperintensities is associated with lower cognitive scores. Neuroimage. 2018;183(August):745–756. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.08.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tuladhar AM, Van Norden AGW, De Laat KF, et al. White matter integrity in small vessel disease is related to cognition. NeuroImage Clin. 2015;7:518–524. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2015.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prins ND, Van Dijk EJ, Den Heijer T, et al. Cerebral small-vessel disease and decline in information processing speed, executive function and memory. Brain. 2005;128(9):2034–2041. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wardlaw JM, Smith C, Dichgans M. Small vessel disease: mechanisms and clinical implications. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18(7):684–696. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30079-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zheng Z, Wenwei R, Bei S, et al. Leukoaraiosis is Associated with Worse Short-Term Functional and Cognitive Recovery after Minor Stroke. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2017;57(3):136–143. doi: 10.2176/nmc.oa.2016-0188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Banerjee G, Chan E, Ambler G, et al. Effect of small-vessel disease on cognitive trajectory after atrial fibrillation-related ischaemic stroke or TIA. J Neurol. 2019;266(5):1250–1259. doi: 10.1007/s00415-019-09256-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kertesz A Western Aphasia Battery (Revised). San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corp; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goodglass H, Kaplan E, Weintraub S. The Revised Boston Naming Test. Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febiger; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Howard D, Patterson K. The Pyramids and Palm Trees Test: A Test of Semantic Access 403 from Words and Pictures. Thames Valley Test Company; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Helm-Estabrooks N Cognitive Linguistic Quick Test: Examiner’s Manual. Psychological Corp; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boyle M Semantic feature analysis treatment for aphasic word retrieval impairments: What’s in a name? Top Stroke Rehabil. 2010;17(6):411–422. doi: 10.1310/tsr1706-411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lambon MA, Snell C, Fillingham JK, et al. Predicting the outcome of anomia therapy for people with aphasia post CVA : Both language and cognitive status are key predictors. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2010;20(2):289–305. doi: 10.1080/09602010903237875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gilmore N, Meier EL, Johnson JP, Kiran S. Typicality-based semantic treatment for anomia results in multiple levels of generalisation. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2018;0(0):1–27. doi: 10.1080/09602011.2018.1499533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meier E, Johnson J, Pan Y, Kiran S. The utility of lesion classification models in predicting language abilities and treatment outcomes in persons with aphasia. Front Hum Neurosci. 2019;12. doi: 10.3389/conf.fnhum.2018.228.00083 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fazekas F, Chawluk JB, Alavi A, Hurtig HI, Zimmerman RA. MR Signal Abnormalities at 1 . 5 T in Alzheimer ‘ s Dementia and Normal Aging deficiency. Am J Roentgenol. 1987;149(August):351–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arsava EM, Lu J, Smith EE. Severity of leukoaraiosis correlates with clinical outcome after ischemic stroke. Neurology. 2009;72(16):1403–1410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maniega SM, Valdés Hernández MC, Clayden JD, et al. White matter hyperintensities and normal-appearing white matter integrity in the aging brain. Neurobiol Aging. 2015;36(2):909–918. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.07.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wardlaw JM, Valdés Hernández MC, Muñoz-Maniega S. What are white matter hyperintensities made of? Relevance to vascular cognitive impairment. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4(6):001140. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.001140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hartwigsen G, Saur D. Neuroimaging of stroke recovery from aphasia - Insights into plasticity of the human language network. Neuroimage. 2017;190(November 2017):14–31. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.11.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lawrence AJ, Chung AW, Morris RG, Markus HS, Barrick TR. Structural network efficiency is associated with cognitive impairment in small-vessel disease. Neurology. 2014;83(4):304–311. doi: 10.1212/wnl.0000000000000612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.De Groot JC, De Leeuw FE, Oudkerk M, Hofman A, Jolles J, Breteler MMB. Cerebral white matter lesions and subjective cognitive dysfunction: The Rotterdam scan study. Neurology. 2001;56(11):1539–1545. doi: 10.1212/WNL.56.11.1539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Van Den Heuvel DMJ, Ten Dam VH, De Craen AJM, et al. Increase in periventricular white matter hyperintensities parallels decline in mental processing speed in a nondemented elderly population. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77(2):149–153. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2005.070193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Debette S, Bombois S, Bruandet A, et al. Subcortical hyperintensities are associated with cognitive decline in patients with mild cognitive impairment. Stroke. 2007;38(11):2924–2930. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.488403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wilmskoetter J, Marebwa B, Basilakos A, et al. Long-range fibre damage in small vessel brain disease affects aphasia severity. Brain. 2019:3190–3201. doi: 10.1093/brain/awz251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gouw AA, Seewann A, Van Der Flier WM, et al. Heterogeneity of small vessel disease: A systematic review of MRI and histopathology correlations. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2011;82(2):126–135. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2009.204685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Debette S, Markus HS. The clinical importance of white matter hyperintensities on brain magnetic resonance imaging: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2010;341(7767):288. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c3666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jokinen H, Kalska H, Ylikoski R, et al. Longitudinal cognitive decline in subcortical ischemic vascular disease -the ladis study. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2009;27(4):384–391. doi: 10.1159/000207442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Van Dijk EJ, Prins ND, Vrooman HA, Hofman A, Koudstaal PJ, Breteler MMB. Progression of cerebral small vessel disease in relation to risk factors and cognitive consequences: Rotterdam scan study. Stroke. 2008;39(10):2712–2719. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.513176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pantoni L, Simoni M, Pracucci G, Schmidt R, Barkhof F, Inzitari D. Visual rating scales for age-related white matter changes (leukoaraiosis): Can the heterogeneity be reduced? Stroke. 2002;33(12):2827–2833. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000038424.70926.5E [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smith EE, Salat DH, Jeng J, et al. Correlations between MRI white matter lesion location and executive function and episodic memory. Neurology. 2011;76(17):1492–1499. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318217e7c8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tullberg M, Fletcher E, DeCarli C, et al. White matter lesions impair frontal lobe function regardless of their location. Neurology. 2004;63(2):246–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.