Abstract

Biofilms are closely packed cells held and shielded by extracellular matrix composed of structural proteins and exopolysaccharides (EPS). As matrix components are costly to produce and shared within the population, EPS-deficient cells can act as cheaters by gaining benefits from the cooperative nature of EPS producers. Remarkably, genetically programmed EPS producers can also exhibit phenotypic heterogeneity at single-cell level. Previous studies have shown that spatial structure of biofilms limits the spread of cheaters, but the long-term influence of cheating on biofilm evolution is not well understood. Here, we examine the influence of EPS nonproducers on evolution of matrix production within the populations of EPS producers in a model biofilm-forming bacterium, Bacillus subtilis. We discovered that general adaptation to biofilm lifestyle leads to an increase in phenotypical heterogeneity of eps expression. However, prolonged exposure to EPS-deficient cheaters may result in different adaptive strategy, where eps expression increases uniformly within the population. We propose a molecular mechanism behind such adaptive strategy and demonstrate how it can benefit the EPS producers in the presence of cheaters. This study provides additional insights on how biofilms adapt and respond to stress caused by exploitation in long-term scenario.

Subject terms: Biofilms, Microbial ecology

Introduction

Cooperative interactions are prevalent for all life forms [1], even for simple microbes that often exist in communities of matrix bound surface-attached cells called biofilms [2–6]. However, when costly products such as siderophores [7, 8], extracellular polymeric substances [9, 10], digestive enzymes [11], and signaling molecules [12, 13] are secreted and shared, cooperative behavior becomes susceptible to cheating [2, 14–16], where mutants defective in cooperation can still benefit from cooperative community members [4, 5, 17]. It has been shown that spatially structured biofilms, where interactions with clone mates are common and diffusion of public goods is limited, may serve as natural defense against cheating [18–20]. However, long time scale studies have recently reported that biofilm defectors can spontaneously emerge and spread in biofilms by exploiting other matrix-proficient lineages [21–24]. In fact, a pioneering microbial evolution study on Pseudomonas fluorescens has already pointed toward dynamic evolutionary interplay between cooperation and exploitation in a biofilm mat [25], where emergence of cellulose overproducer (wrinkly) allowed mat formation, but also created an opportunity for exploitation by nonproducers (smooth), eventually leading to so-called “tragedy of the commons” [4, 26, 27].

Taken together, biofilms are a suitable model to understand social interactions in an evolutionary time scale [23, 28–31]. Modeling and empirical data confirm that mutualism (beneficial to both actor and recipient) and altruism (beneficial to recipient but not to actor) play crucial roles in biofilm enhancement [32], but at the same time can lead to biofilm destabilization [25]. Can cooperators evolve tactics to evade exploitation and, in turn, can cheats utilize evolution to enhance their selfish actions?

Recent studies showed that in well-mixed environment, cooperators adapt to cheats by reducing cooperation [14, 15, 33]. Such reduction could be achieved by various strategies, for instance decrease in motility [15], downregulation or minimal production in public goods [14, 15, 33], upregulation of other alternative public goods [14], or bi-stable expression in virulence gene [2]. Interestingly, populations of cooperators often exhibit phenotypic heterogeneity at the single-cell level [34, 35]. Therefore, an alternative and simple mechanism to modulate levels of cooperation in a population would be through changes in phenotypic heterogeneity pattern. However, the long-term effects of cheats on costly goods’ expression at individual cell level have never been examined. Understanding how heterogeneity of gene expression within the population is affected in the presence of cheats would provide better insight on microbial adaptation and stress response mechanisms.

Here, we address this question using pellicle biofilm model of Bacillus subtilis (B. subtilis) [36, 37]. Pellicle formation in B. subtilis involves, among others, aerotaxis-driven motility and subsequent matrix production [38]. Aerotaxis is important for oxygen sensing to aid cells reach the surface, while matrix formation is significant to sustain cells to adhere to the surface and to each other. Exopolysaccharide (EPS) is a costly public good in B. subtilis biofilms [10, 18, 39] and is heterogeneously expressed during biofilm formation with ~40% of cells exhibiting the ON state [39, 40]. We aimed to investigate the cheat-dependent alteration related to phenotypic heterogeneity in eps expression by the producer.

We reveal that cheating mitigation by the EPS producers involves a shift in phenotypic heterogeneity toward stronger eps expression, which can be achieved by a loss-of-function mutation in a single regulatory gene. Our study uncovers an alternative anti-cheating mechanism based on changes in public goods’ expression pattern and highlights meandering trajectories prior cooperation collapse.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains and culture conditions

Strain B. subtilis 168 Phyperspank-mKATE Peps-GFP (TB869) was obtained by transforming the laboratory strain, B. subtilis 168 Phyperspank-mKATE (TB49) [10, 18], with genomic DNA from NRS2243 (sacA::PepsA-gfp(Km)hag::cat) and selecting for Km resistance. The ∆rsiX strain with fluorescence reporters (TB959) was obtained by transforming TB869 with genomic DNA isolated from BKE23090 (168 trpC2 ∆rsiX::erm) [41]. Strains were maintained in LB medium (Lysogeny Broth (Lennox), Carl Roth, Germany), while 2 × SG medium was used for biofilm induction [10]. The ∆eps strains (TB608) were created previously [10].

Experimental evolution

Eight biological replicates of the cocultures of 1:1 ratio of B. subtilis TB869 and TB608 were grown in 48-well plate containing 1 ml 2 × SG medium at 30 °C for 2 days. Pellicles were harvested into Eppendorf tubes containing 500 μl sterile 2 × SG medium and 100 μl of sterile glass sand, vortexed for 90 s, 10 μl fraction was transferred into 1 ml 2 × SG medium of a 48-well plate and incubated at 30 °C static condition for 2 days. Such growth cycle was continuously repeated 35 times. As a control treatment, four biological replicates of mono-cultures of B. subtilis TB869 were evolved using the same transfer method. Every fifth transfer (five growth cycles), harvested cultures were mixed with 15% glycerol and stored at –80 °C.

Population ratio assay

At every fifth transfer, pellicle biofilm productivities and relative frequencies of mutants and wild type (WT) were qualitatively assessed (colony forming units (CFU)/ml) using LB agar containing selective antibiotics. LB agar plates were incubated at 37 °C for 16 h and colonies were counted. Three single clones of WT and of ∆eps per population per time point were isolated from plates and stored at –80 °C in the presence of 15% glycerol.

Pellicle competition assay/fitness assay

Competition assays were performed as previously described [10]. Specifically, strains of interest were premixed at 1:1 ratio based on their OD600 values and the mixture was inoculated into 2 × SG medium at 1%. Cultures were grown for 48 h under static conditions at 30 °C and their relative frequencies were accessed using CFU counts (and selective antibiotics).

Stereomicroscopy to assess competition of WT and ΔrsiX against Δeps

Fluorescent images of pellicles were obtained with an Axio Zoom V16 stereomicroscope (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany) equipped with a Zeiss CL 9000 LED light source and an AxioCam MRm monochrome camera (Carl Zeiss) and HE eGFP (excitation at 470/40 nm and emission at 525/50 nm), and HE mRFP (excitation at 572/25 nm and emission at 629/62 nm) filter sets. Images were taken at 3.5× and 55× magnifications. The exposure times for green and red fluorescence were set up to maximal possible values before reaching overexposure, using range indicator function. Zeiss software was used to obtain overlaid, artificially colored images of both fluorescence channels.

Qualitative assessment of eps expression pattern via laser scanning confocal microscopy

Single isolates of evolved WT (TB869) obtained from population ratio assay were allowed to form 1-day-old pellicle. Harvested pellicles were subjected to microscopic analysis using an Axio Observer 780 Laser Scanning Confocal Microscope (Carl Zeiss) equipped with a Plan-Apochromat 63 × /1.4 Oil DIC M27 objective, an argon laser for stimulation of fluorescence (excitation at 488 nm for green fluorescence and 561 nm for red fluorescence, with emission at 528/26 and 630/32 nm, respectively). Zen 2012 Software (Carl Zeiss) and FIJI Image J Software [42] were used for image recording and processing, respectively.

Flow cytometry and data analysis

Frozen stocks of evolved populations were transferred onto LB-agar plates containing kanamycin (5 µg/ml) to select solely for WT colonies. The plates were incubated overnight at 37 °C, followed by inoculation of ten randomly selected single colonies into 2 × SG medium. After 24h-incubation at 30 °C, the pellicles were harvested, sonicated, and diluted accordingly. Flow cytometry was performed using BD FACSCanto II (BD Biosciences). To separate bacterial cells from noise, mKate-fluorescence (constitutively expressed reporter) and GFP fluorescence (Peps-GFP promoter fusion) were recorded, gating was setup for mKate-positive objects, and GFP signal was measured within these objects. Histograms of Peps-GFP were created in OriginPro using the same binning intervals for all samples. To remove sample size differences (different amounts of measured objects), histograms were normalized to maximum count, described as Normalized Frequency.

To obtained an average distribution image of eps expression within populations, a mean count for each histogram bin was calculated (by averaging individual counts within this bin obtained for single isolates), resulting in mean distribution of single-cell level eps expression per population. Such “averaged” histograms were used solely for visual representation of data and not for statistical analysis.

Genome re-sequencing and genome analysis

Genomic DNA of single isolates from selected evolved populations were extracted using Bacterial and Yeast Genomic DNA kit (EURx) directly from –80 °C stocks grown in LB medium for 5 h at 37 °C with shaking at 220 rpm. For population sequencing analysis, ~100 colonies belonging to the evolved populations were harvested into 2 ml LB broth and incubated at 37 °C shaking at 220 rpm for 2–3 h. Re-sequencing was performed on an Illumina NextSeq instrument using V2 sequencing chemistry (2 × 150 nt). Base calling was carried out with “bcl2fastq” software (v.2.17.1.14, Illumina). Paired-end reads were further analyzed in CLC Genomics Workbench Tool 9.5.1. Reads were quality-trimmed using an error probability of 0.05 (Q13) as the threshold. Reads that displayed ≥80% similarity to the reference over ≥80% of their read lengths were used in mapping. Quality-based SNP and small In/Del variant calling were carried out requiring ≥10× read coverage with ≥25% variant frequency. Only variants supported by good quality bases (Q ≥ 30) on both strands were considered. Gene functions (product names) in SI Appendix Datasets were reported based on SubtiWiki [43].

Statistical analysis

Statistical differences between two experimental time-points of the same experimental groups (e.g., changes in relative frequencies of WT and Δeps during evolution) were accessed using pair-sample t-test. Statistical differences between two experimental groups were calculated using two-sample t-test. To compare multiple samples with WT, we used one-way repeated measures ANOVA and Dunnett test. ANOVA and Tukey test were used for multiple samples comparisons.

For analysis of Peps-GFP expression in evolved populations, we used ten randomly picked single colonies, cultivated from the frozen stocks (tenth transfer) on LB-agar plate with appropriate selection marker (selecting against Δeps). All flow cytometry data of Peps-GFP expression were transferred to histograms, and fitted to Gauss function. Differences in average eps expression per population compared with WTanc and differences in single-cell level distribution of eps expression compared with WTanc were calculated using one-way repeated measures ANOVA and mean comparison by Dunnett test. Deviation from WT-like distribution was assessed from changes in adjusted R-squared (Adj. R. Sq) values for Gauss fitting of flow cytometry data. All evolved populations, where average Adj. R. Sq was significantly lower compared with WT ancestor, were suspected to have evolved different phenotypic heterogeneity pattern of eps expression. Corresponding histograms were visually inspected, classified as potentially bimodal, and subjected to multiple peak fitting. In all such cases, fit quality was improved (Adj. R. Sq > 0.98). Mean expression for eps-low and eps-high subpopulations was compared by ANOVA, Tukey test. No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample size and the experiments were not randomized. One data point was removed from the Peps-GFP flow cytometry dataset of ΔrsiX as a significant outlier (P < 4.5 × 10−7) confirmed by Grubbs test. All statistical tests and data fitting were performed using OriginPro 2018 software.

Results

Cheaters modulate evolution of phenotypic heterogeneity of eps expression in the WT

EPS is one of the major components of B. subtilis biofilm matrix and mutants deficient in EPS production (∆eps) are not able to form pellicle biofilms (Supplementary Fig. 1). In line with previous results [10, 18, 39], we confirmed that the ∆eps can take advantage of EPS-producing WT and incorporate into the pellicle biofilm, resulting in lower productivity of the WT (Supplementary Fig. 1b) and reduced surface complexity of the pellicle (Supplementary Fig. 1a). Interestingly, despite pellicles formed by the WT + Δeps lacked surface complexity and were more fragile compared with the WT monoculture pellicles (as easily observed during sampling), the total numbers of viable cells (our productivity measure) in the WT and mixed pellicles were similar (Supplementary Fig. 1b). This indicates high carrying capacity of the WT to support surface colonization by Δeps.

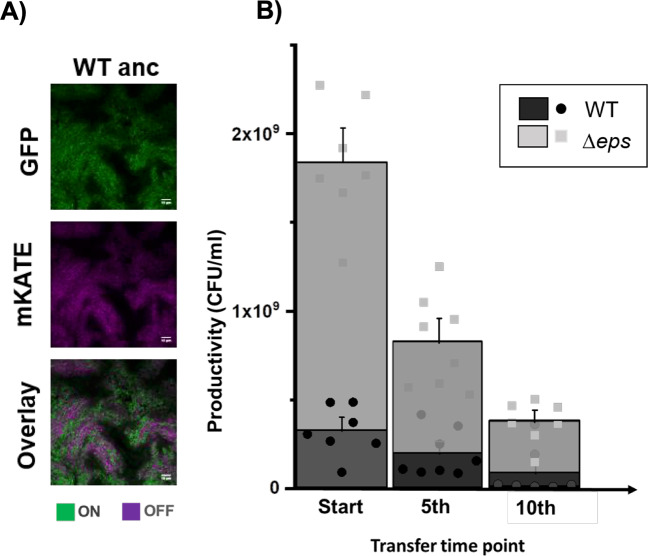

We were further interested if such social cheating could leave a phenotypic or genetic fingerprint in the population of the WT B. subtilis. Previous studies have shown that cooperators can adapt to presence of cheats, for example, by decreasing the amount of released public goods and therefore minimizing cheating opportunities [2, 14, 15]. As B. subtilis exhibits phenotypic heterogeneity in eps matrix gene expression [39, 40] (Fig. 1a), we investigated how such heterogeneous expression is influenced by the presence of cheats in an evolutionary perspective.

Fig. 1. Pellicle productivity and phenotypic heterogeneity.

a Total colony forming unit per ml of WT and ∆eps in 48-h-old pellicles non-evolved (start) (n = 9), after experimental evolution at fifth (n = 8 populations), and tenth transfer (n = 7 populations). One population after tenth transfer was unable to form pellicle attributed to WT being totally outnumbered by ∆eps. Dots represent data obtained for all individual populations, while columns represent averages. Error bars correspond to standard error. Levels of Δeps at the start, fifth, and tenth transfers were 82%, 76% (p < 0.29 compared with start, pair-sample t-test), and 83% (p < 0.42 compared with start, pair-sample t-test). b Pellicles formed by WTmKATE Peps-GFP viewed under the confocal laser scanning microscope. Cells constitutively expressing mKATE are represented in magenta (OFF cells) and eps-expressing cells (ON cells) are represented in green. Scale bar 10 µm. (Color figure online).

To address this question, we cocultured the EPS producers (WT) and cheaters (∆eps) for ten biofilm growth cycles (~60 generations) starting at 1:1 ratio (see “Methods”). Based on previous studies [21, 44], we assumed that this evolutionary timeframe will be sufficient for evolution of adaptive mechanisms in the WT in response to social cheating, at the same time preventing the diversification of the WT into a biofilm-deficient morphotype, which can be observed on longer evolutionary timescales [21].

During ten-cycle cocultivation of WT and Δeps strain, we observed a general trend of declining pellicle productivity (Fig. 1b). The relative frequency of EPS nonproducers in biofilms was maintained at the high level across all parallel populations (82% at the start, 76% after fifth transfer with p < 0.29, and 83% after tenth transfer with p < 0.42) (Fig. 1b), indicating that the WT strain was constantly exposed to social cheating throughout the experiment.

Using confocal laser scanning microscopy, qualitative assessment of randomly selected isolates revealed that early populations of the EPS producers (5–10 transfers) exhibited different phenotypes compared with the WT ancestral strain (WTanc) (Supplementary Fig. 2). To obtain a quantitative comparison of single-cell level expression of eps in the WTanc vs. evolved WT populations, we performed flow cytometry measurements of Peps-GFP harboring strains in pellicles formed by ten randomly selected isolates per population (Supplementary Fig. 3).

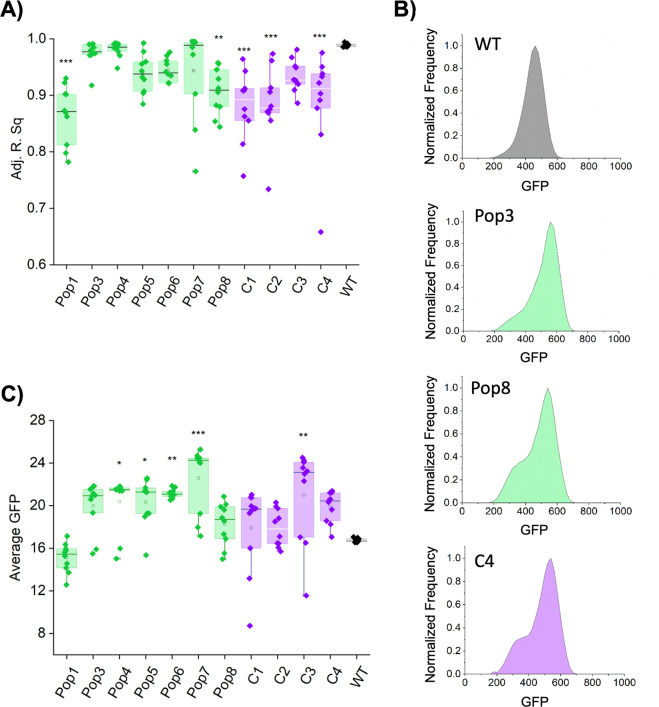

First, we noticed that in most strains isolated from the control evolved populations exhibited an increase in phenotypic heterogeneity in eps expression as compared with the WT ancestor (Fig. 2a, b; Supplementary Fig. 3, Supplementary Dataset 1). Increased level of phenotypic heterogeneity was evident from frequency distributions of single-cell Peps-GFP expression data (Fig. 2b). Specifically, while single-cell level distribution of Peps-GFP in the WT ancestor, ideally fitted the Gauss function (Adj. R. Sq = 0.99 ± 0.01), indicating presence of a single population of eps-expressing cells (Fig. 2a, b; Supplementary Fig. 3). This was no more the case for the populations of WT evolved without cheater (C1, C2, and C4; Adj. R. Sq: 0.88–0.93), where distributions of Peps-GFP shifted away from the unimodal distribution (as could be quantitatively expressed in significantly lower Adj. R. Sq values, therefore lower percentage of data points fitting into Gauss model) toward bimodal distributions (Fig. 2a, b; Supplementary Fig. 3; Supplementary Dataset 1). Presence of two frequency peaks, one at low and second at high Peps-GFP fluorescence levels, was particularly evident in some of the control populations (Supplementary Fig. 3). Similar change was noticed for two WT populations evolved with cheaters (Fig. 2a; Supplementary Fig. 3, Pop1 and Pop8; Adj. R. Sq: 0.87–0.94). In the aforementioned populations, the eps expression was also rather bimodal, distributed between low-eps and high-eps subpopulations (Fig. 2a, b; Supplementary Fig. 3; Supplementary Dataset 1). Importantly, these bimodal populations evolved alone (C1, C2, and C4) or co-evolved with Δeps (Pop1 and Pop8), were similar in terms of eps expression levels or ratios of low-eps and high-eps subpopulations (Supplementary Dataset 1). In addition, an average within-population eps expression increased in four out of seven populations that evolved with cheater, but only in one control population evolved without cheats (Fig. 2c, Supplementary Dataset 1). Finally, higher levels of eps expression positively correlated with lower levels of within-population heterogeneity (therefore higher Adj. R. Sq values) (Pearson correlation coefficient 0.33; p < 0.0004).

Fig. 2. Evolutionary changes in phenotypic heterogeneity pattern and expression of eps.

a Changes in distribution of Peps-GFP signal in co-evolved (Pop1–Pop8) and evolved (C1–C4) WT populations compared with the WTanc manifested as a decline of adjusted R-square values for Gauss model fitting. b Flow cytometry analysis showing average distributions of Peps-GFP in WTanc (dark gray), WT evolved with cheaters, Pop3 and Pop8 (green) and WT evolved without cheaters, C4 (purple). c Average Peps-GFP expression levels in co-evolved (Pop1–Pop8) and evolved (C1–C4) WT populations compared with the WTanc, calculated from mean values of Peps-GFP expression within ten single isolates. For a and c panels *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001 compared with the WTanc (one-way repeated measures ANOVA, Dunnett test). All data and corresponding p values are provided in Supplementary Data 1. (Color figure online).

Altogether, most populations co-evolved with cheater showed a significant increase in eps expression levels, retaining WT-like phenotypic heterogeneity pattern (no significant changes in Adj. R. Sq for unimodal Gauss distribution fitting); we define this evolved phenotype as high eps. On the contrary, in majority of control populations (evolved without cheaters) phenotypic heterogeneity level increased, without significant increase in mean eps expression (Fig. 2; Supplementary Fig. 3; Supplementary Dataset 1); we define this evolved phenotype as heterogenous eps.

Mutations in rsiX lead to high-eps phenotype

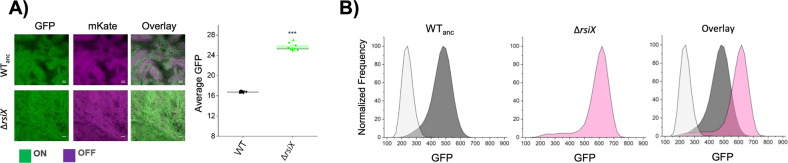

To unravel the genetic basis of the high-eps phenotype that evolved in presence of cheats, several single isolates from the evolved populations were subjected to genome re-sequencing (for details see “Methods”). The comparative analysis of sequencing data revealed that Population 3 and Population 7, co-evolved with Δeps, shared mutations in rsiX gene (Supplementary Dataset 2). The rsiX gene encodes for an anti-sigma factor that controls the activity of extracellular cytoplasmic function (ECF) sigma factor X which is involved in cationic antimicrobial peptide resistance important for cell envelope stress response [45]. Detected mutations resulted either in substitution of Valine 106 to Alanine or frameshift mutations in Serine 104 or Isoleucine 347 that could lead to change or loss of anti-SigX function. Indeed, we were able to recreate the evolved high-eps phenotype in the pellicle solely by deleting the rsiX gene in the WT ancestor (Fig. 3a, b). Interestingly, a different type of frameshift mutation in Lysine 200 was found in one population of evolved WT alone but this population demonstrated a bimodal phenotypic heterogeneity pattern (Fig. 2; Supplementary Fig. 3; Supplementary Dataset 1), suggesting that only certain types of mutations in rsiX lead to the uniform shift in eps expression or additional mutations have antagonistic effects in this isolate.

Fig. 3. Effect of rsiX deletion on eps expression in pellicles.

a Qualitative assessment of eps gene expression based on confocal laser scanning microscopy of pellicles formed by ∆rsiX showing high eps compared with WTanc. Cells constitutively expressing mKATE (OFF) are shown in magenta and eps-expressing cells (ON) are represented in green. Scale bar 10 µm. Right panel: average Peps-GFP expression levels in WTanc and ΔrsiX the WTanc calculated from mean values of Peps-GFP expression within ten single isolates. ***p < 0.001 (two-sample t-test). All data and corresponding p values are provided in Supplementary Data 1. b Flow cytometry results showing average distribution of fluorescence intensities of WTanc cells (dark gray), ∆rsiX cells (pink), and overlay of the two in comparison to WT non-labeled (light gray). (Color figure online).

Mutation in rsiX contributes to competitive advantage of producer strains against cheats

As mutation in rsiX resulted in high-eps phenotype that may be linked to elevated secretion of EPS, we hypothesized that ΔrsiX producers could support the spread of cheats. To better understand how ancestor WT and ΔrsiX interact with Δeps, we cultivated the Δeps in presence of EPS-containing supernatants obtained from the WT and ΔrsiX (Supplementary Fig. 4). Both supernatants could partially restore pellicle formation by Δeps resulting in similar productivities of Δeps, thereby not supporting our hypothesis on improved performance of the mutant in presence of high-eps ΔrsiX strain.

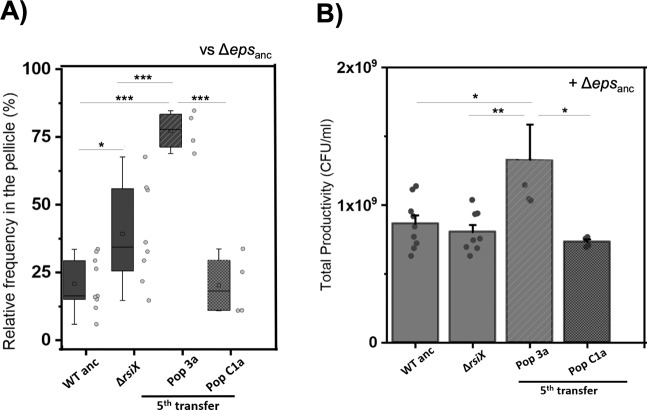

In order to determine the effect of rsiX deletion on fitness of the WT in presence of cheats, we performed a series of competition assays. Apparently, the ∆rsiX showed two-fold increase in relative frequency (40%) (Fig. 4a; Supplementary Fig. 5) when competed against the ∆eps, as compared with the WT ancestor (20%). In addition, even higher fitness improvement was observed for the WT co-evolved with cheats fifth transfer and tenth transfer, mutually with occurrence of high-eps phenotype in those populations. This was not the case for the WT evolved alone at fifth transfer (20%) (Fig. 4a; Supplementary Fig. 5). These results suggest that rsiX mutation, which is associated with high-eps phenotype, does not fully explain, but contributes to the early improvement of WT competitive strategies against cheats.

Fig. 4. Performance of evolved WT and ΔrsiX in cocultures with Δepsanc.

a Relative frequencies of single isolates belonging to producer populations (WTanc (n = 9), ∆rsiX (n = 8), WT evolved with (Pop3a; n = 4) and without cheaters (PopC1a; n = 4)) in mixed pellicles with ∆epsanc. b Productivity assay based on total CFU/ml of pellicles of cocultures of ∆epsanc and single isolates belonging to producer populations (WTanc (n = 9), ∆rsiX (n = 8), WT evolved with (Pop3a; n = 4) and without cheaters (PopC1a; n = 4)). Mean is represented in square within the box plots; median is denoted by horizontal line inside the boxes; whiskers represent the min and max; error bars in bar graph are based on standard error; single dots represent the individual data points. For a and b panels: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001 (ANOVA, Tukey test).

It is worth to mention that we could not detect any significant fitness costs or benefits linked to rsiX deletion in pairwise competition between ΔrsiX and WT in the liquid medium (Supplementary Fig. 6; relative fitness of ΔrsiX = 1.00 ± 0.02 SD). Furthermore, we did not observe significant differences in productivities of WT and the ΔrsiX mutant, when grown in monoculture pellicles (Fig. 4b), indicating that positive effect of rsiX mutation only manifests in presence of cheats. Similarly, different relative frequencies of Δeps in pellicles formed by the ancestor or evolved matrix producers, did not result in different productivities of mixed pellicles (Supplementary Fig. 7). These results suggest that high-eps phenotypes are vested on the increase in eps-expressing cells or limiting the spread of cheats but do not result in an increase in total yield.

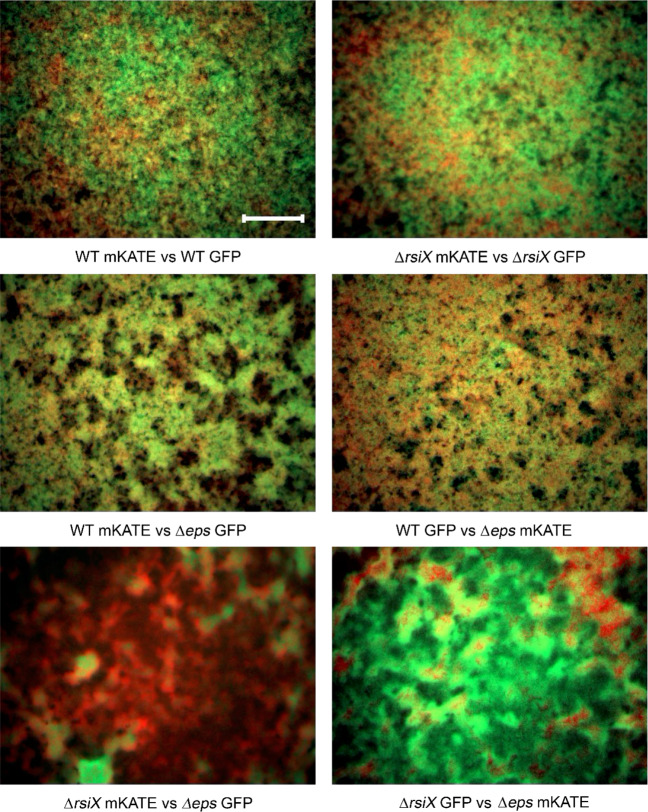

It was previously demonstrated that increased matrix production can allow favorable positioning of a bacterial strain in the biofilm, thereby providing fitness advantage [46]. To test whether high-eps phenotype can allow better positioning of the ΔrsiX in presence of Δeps, we visualized 48 h grown pellicles formed by ΔrsiX:Δeps and WT:Δeps mixtures inoculated at 1:1 initial frequencies (Fig. 5; Supplementary Fig. 8). While WT and Δeps were “well-mixed” with both strains present on the oxygen-rich surface of the pellicle, the ΔrsiX strain clearly dominated over the Δeps occupying majority of the biofilm surface and marginalizing the Δeps into small clusters (Fig. 5; Supplementary Fig. 8). Therefore, deletion of rsiX and an associated high-eps phenotype provides fitness advantage in the presence of Δeps most likely by allowing the EPS producers to occupy upper, oxygen-rich layers of the pellicle. Therefore, rsiX frameshift mutation found in certain co-evolved WT populations could be an adaptive mechanism to resist cheating by EPS-deficient strain.

Fig. 5. Effect of rsiX deletion on positioning of EPS producers in the pellicle.

Competition assay between WT + Δeps and ΔrsiX + Δeps. Strains labeled with constitutively expressed GFP and mKate proteins were inoculated in 1:1 initial frequency, pellicles were cultivated for 48 h at 30 °C and visualized using stereomicroscope. Upper panels represent controls (two isogenic WT or ΔrsiX strains labeled with different fluorescent markers), middle panel represents pellicles formed by WT + Δeps, and bottom panels represent pellicles formed by ΔrsiX + Δeps, each in two alternative combinations of fluorescent markers. Scale bar corresponds to 500 µm.

High-eps phenotype serves as a transient adaptive response to cheating

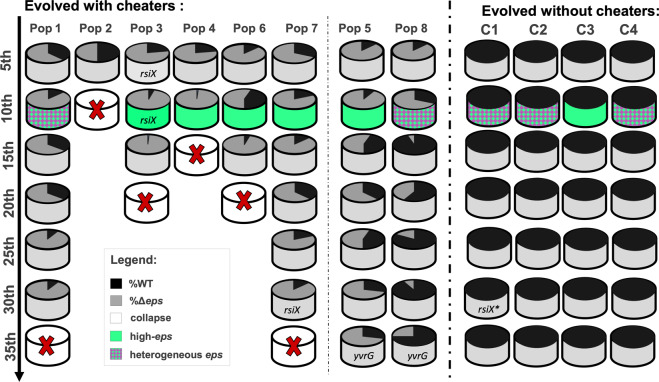

As the evolved WT isolates carrying point mutation in rsiX as well as the recreated ΔrsiX mutant (in ancestral genetic background) performed better in competition with Δeps as compared with the WTanc, we reasoned that loss-of-function mutation in rsiX together with an associated high-eps phenotype might be an efficient evolutionary strategy against social cheating. Surprisingly, however, prolonged evolution experiment eventually led to so-called “tragedy of the commons” as the Δeps mutant took over in six out of eight populations, completely abolishing the pellicle formation (Fig. 6; Supplementary Fig. 9).

Fig. 6. Changes in relative frequencies and eps expression pattern during evolution with and without cheaters.

Summary figure shows the population dynamics based on producer and cheater frequency per population from 5th transfer to 35th transfers for populations evolved with cheaters with collapse (Pop1–4, 6, and 7) and without collapse (Pop5 and 8) and populations evolved without cheaters (C1–C4) with indications of phenotypes based on high-eps or heterogenous-eps expression. Key mutations on single clone level of evolved WT and evolved ∆eps or population level are specified. The *rsiX mutation differs from mutation observed in strains evolved with cheaters.

To investigate the genetics behind this phenomenon all evolved WT populations from the last evolutionary time point (or the last time point prior the collapse) were re-sequenced. Curiously, in contrast to the WT populations that were outcompeted by Δeps, both WT populations which resisted the invasion (Pop5 and Pop8), carried mutations in yvrG gene (Supplementary Fig. 9; Supplementary Dataset 2) encoding for two-component histidine kinase involved in cell wall process. Finally, the rsiX mutation was not detected neither in the last populations before the collapse, with an exemption of population 7, nor at the last transfer point for the non-collapse populations (Supplementary Dataset 2), implying that this mutation was lost in the late populations.

Discussion

Studies on evolution of cooperative behavior are important to understand how social behaviors are shaped in longer time scale. Moreover, exploring long-term consequences of exposure to cheating allows to better understand how cooperation prevails in nature where environmental stress and exploitation exist inherently. Here, we took a reductionist approach, focusing on evolution of a single cooperative trait—the expression of eps, which plays a crucial role in biofilm lifestyle of B. subtilis and other bacteria. As we focused on the single-cell level expression of eps in multiple single strain, isolated from the ancestral or evolved populations, we could obtain a multi-level insight into evolutionary changes in eps expression. Our study revealed previously observed population-level diversification of matrix genes expression, indicating the strain-independence and reproducibility of adaptation in biofilms [21, 24]. Strikingly, next to population-level diversification, we also observe an increase in phenotypic heterogeneity of eps expression within single isolates. Based on coculture studies performed for WT and Δeps (this work), as well as for WT and spontaneously evolved biofilm-deficient lineage [21], we believe that low-eps subpopulations may be acting as conditional cheater, supported by “hyper-cooperative” subpopulations of high eps. The observation that isolates with the most pronounced phenotypic diversification pattern tend to show lower average eps expression, clearly depicts the latter as a consequence of diversification, and specifically emergence of low eps. It remains to be determined whether increased/reduced levels of eps expression translate into higher/lower amount of released EPS, but based on previous studies it is likely to be the case [44].

Previous evolution studies on cheater-cooperator interactions in spatially structured environment showed cheater mitigation via minimization of the cooperative trait [2, 14, 15]. On the contrary, here we show that cooperators respond to cheating by intensifying the cooperative behaviors through uniform shift toward higher eps expression. Further molecular analysis of the high-eps isolates strongly suggests that this phenotype is triggered by loss-of-function mutation in rsiX gene. The product of rsiX represses the activity of ECF sigma factor, SigX that is involved in cell envelope stress response against cationic antimicrobial peptides [47]. Importantly, SigX has been previously shown to induce expression of epsA-O in B. subtilis via a complex regulatory pathway involving Abh and SlrR [48], explaining the observed enhanced in eps gene expression in rsiX mutant. Another example of matrix overproduction via ECF adaptation was also reported in gram-negative bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa) where mutations in another ECF called AlgT led to alginate overproduction and increased resistance to antimicrobials [49]. Therefore, adaptive boosts in matrix production through modulation of ECF are not exclusive for B. subtilis, but seem to occur also in medically relevant gram-negative pathogens like P. aeruginosa.

In contrast to previous studies that addressed long-term cheating on diffusible siderophores [50–53], we explored evolutionary interplay between biofilm producers and nonproducers in structured environment. Our results support previous observations on evolution of specific cheating-resisting mechanisms in cooperators, pointing toward ubiquity of this phenomenon. In addition, our work brings up three major findings: (1) matrix producers can adapt to matrix nonproducers by shifting phenotypic heterogeneity toward increased levels of matrix expression, (2) high-eps phenotype is associated with favorable positioning of the matrix producers in the biofilm in presence of cheats, thereby limiting their numbers, (3) high-eps anti-cheating strategy is a short-term solution followed by tragedy of the commons. As EPS-deficient strain took over in all but two mixed populations (including populations, without rsiX mutation and homogenous shift toward higher eps expression), we do not interpret the collapse as a direct consequence of mutation in rsiX gene. However, we argue that an emergence of several matrix overproducing lineages, may facilitate the spread of cheats [21], especially if a substantial number of cells within the high-eps lineage serves as facultative (phenotypic) cheaters. As recently demonstrated, EPS deficiency is not a dead-end strategy for B. subtilis population, because alternative EPS-independent biofilm formation strategies can emerge by single amino acid change is TasA [44]. It remains to be discovered whether shifts in phenotypic heterogeneity in response to long-term cheating is general phenomenon that applies to different types of public goods.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Figure and Dataset legends

Acknowledgements

The authors thank James Gurney and other anonymous reviewers for their suggestions. This work was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) to ÁTK (KO4741/2.1) within the Priority Program SPP1617. MM was supported by a FEMS Research and Training Grant (FEMS-RG-2017-0054). This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 713683 (H.C. Ørsted COFUND to AD). Work in the laboratory of ÁTK is partly supported by the Danish National Research Foundation (DNRF137) for the Center for Microbial Secondary Metabolites.

Author contributions

ÁTK conceived the project. MM, AD, SB, and DS performed the experiments. GM contributed with methods. MM, AD, and ÁTK wrote the paper, with all authors contributing to the final version.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version of this article (10.1038/s41396-020-0685-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Bourke A. Principals of social evolution: Oxford series in ecology and evolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diard M, Garcia V, Maier L, Remus-Emsermann MNP, Regoes RR, Ackermann M, et al. Stabilization of cooperative virulence by the expression of an avirulent phenotype. Nature. 2013;494:353–6. doi: 10.1038/nature11913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nadell CD, Xavier JB, Foster KR. The sociobiology of biofilms. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2009;33:206–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2008.00150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.West SA, Diggle SP, Buckling A, Gardner A, Griffin AS. The social lives of microbes. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst. 2007;38:53–77. [Google Scholar]

- 5.West Sa, Griffin AS, Gardner A. Evolutionary explanations for cooperation. Curr Biol. 2007;17:661–72. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xavier J, Foster KR. Cooperation and conflict in microbial biofilms. Proc Natl Adac Sci USA. 2007;104:876–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607651104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luján AM, Gómez P, Buckling A. Siderophore cooperation of the bacterium Pseudomonas fluorescens in soil. Biol Lett. 2015;11:20140934. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2014.0934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weigert M, Kümmerli R. The physical boundaries of public goods cooperation between surface-attached bacterial cells. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci. 2017;284:20170631. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2017.0631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dragoš A, Kovács ÁT. The peculiar functions of the bacterial extracellular matrix. Trends Microbiol. 2017;25:257–66. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2016.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin M, Dragoš A, Hölscher T, Maróti G, Bálint B, Westermann M, et al. De novo evolved interference competition promotes the spread of biofilm defectors. Nat Commun. 2017;8:15127. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Folse HJ, Allison SD. Cooperation, competition, and coalitions in enzyme-producing microbes: social evolution and nutrient depolymerization rates. Front Microbiol. 2012;3:338. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Popat R, Crusz SA, Messina M, Williams P, West SA, Diggle SP. Quorum-sensing and cheating in bacterial biofilms. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci. 2012;279:4765–71. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2012.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dogsa I, Oslizlo A, Stefanic P, Mandic-mulec I. Social interactions and biofilm formation in Bacillus subtilis. Food Technol Biotechnol. 2014;52:149–57. [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Brien S, Luján AM, Paterson S, Cant MA, Buckling A. Adaptation to public goods cheats in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci. 2017;284:20171089. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2017.1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kümmerli R, Santorelli LA, Granato ET, Dumas Z, Dobay A, Griffin AS, et al. Co-evolutionary dynamics between public good producers and cheats in the bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Evol Biol. 2015;28:2264–74. doi: 10.1111/jeb.12751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harrison F. Dynamic social behaviour in a bacterium: Pseudomonas aeruginosa partially compensates for siderophore loss to cheats. J Evol Biol. 2013;26:1370–8. doi: 10.1111/jeb.12126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hamilton WD. The genetical evolution of social behaviour. I. J Theor Biol. 1964;7:1–16. doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(64)90038-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Gestel J, Weissing FJ, Kuipers OP, Kovács ÁT. Density of founder cells affects spatial pattern formation and cooperation in Bacillus subtilis biofilms. ISME J. 2014;8:2069–79. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2014.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nadell CD, Foster KR, Xavier JB. Emergence of spatial structure in cell groups and the evolution of cooperation. PLoS Comput Biol. 2010;6:e1000716. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Momeni B, Waite AJ, Shou W. Spatial self-organization favors heterotypic cooperation over cheating. Elife. 2013;2:e00960. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dragoš A, Lakshmanan N, Martin M, Horváth B, Maróti G, García CF, et al. Evolution of exploitative interactions during diversification in Bacillus subtilis biofilms. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2018;94:fix155. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Ellis CN, Traverse CC, Mayo-Smith L, Buskirk SW, Cooper VS. Character displacement and the evolution of niche complementarity in a model biofilm community. Evolution. 2015;69:283–93. doi: 10.1111/evo.12581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Poltak SR, Cooper VS. Ecological succession in long-term experimentally evolved biofilms produces synergistic communities. ISME J. 2011;5:369–78. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2010.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goymer P, Kahn SG, Malone JG, Gehrig SM, Spiers AJ, Rainey PB. Adaptive divergence in experimental populations of Pseudomonas fluorescens. II. Role of the GGDEF regulator WspR in evolution and development of the wrinkly spreader phenotype. Genetics. 2006;173:515–26. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.055863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rainey PB, Rainey K. Evolution of cooperation and conflict in experimental bacterial populations. Nature. 2003;425:72–4. doi: 10.1038/nature01906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.West SA, Griffin AS, Gardner A, Diggle SP. Social evolution theory for microorganisms. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2006;4:597–607. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hardin G. The tragedy of the commons. Science. 1968;162:1243–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martin M, Hölscher T, Dragoš A, Cooper VS, Kovács ÁT. Laboratory evolution of microbial interactions in bacterial biofilms. J Bacteriol. 2016;198:2564–71. doi: 10.1128/JB.01018-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Traverse CC, Mayo-Smith LM, Poltak SR, Cooper VS. Tangled bank of experimentally evolved Burkholderia biofilms reflects selection during chronic infections. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:E250–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1207025110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Madsen JS, Lin YC, Squyres GR, Price-Whelan A, Torio A, de S, et al. Facultative control of matrix production optimizes competitive fitness in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14 biofilm models. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2015;81:8414–26. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02628-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rainey PB, Travisano M. Adaptive radiation in a heterogeneous environment. Nature. 1998;394:69–72. doi: 10.1038/27900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kreft JU. Biofilms promote altruism. Microbiology. 2004;150:2751–60. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26829-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lyons NA, Kolter R. A single mutation in rapP induces cheating to prevent cheating in Bacillus subtilis by minimizing public good production. Commun Biol. 2018;1:133. doi: 10.1038/s42003-018-0136-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Veening JW, Igoshin OA, Eijlander RT, Nijland R, Hamoen LW, Kuipers OP. Transient heterogeneity in extracellular protease production by Bacillus subtilis. Mol Syst Biol. 2008;4:1–15. doi: 10.1038/msb.2008.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Davidson FA, Seon-Yi C, Stanley-Wall NR. Selective heterogeneity in exoprotease production by Bacillus subtilis. PLoS One. 2012;7:e38574. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kovács ÁT. Bacillus subtilis. Trends Microbiol. 2019;27:724–5. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2019.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kovács ÁT, Dragoš A. Evolved biofilm: review on the experimental evolution studies of Bacillus subtilis pellicles. J Mol Biol. 2019;431:4749–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2019.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hölscher T, Bartels B, Lin Y-C, Gallegos-Monterrosa R, Price-Whelan A, Kolter R, et al. Motility, chemotaxis and aerotaxis contribute to competitiveness during bacterial pellicle biofilm development. J Mol Biol. 2015;427:3695–708. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2015.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dragoš A, Kiesewalter H, Martin M, Hsu C-Y, Hartmann R, Wechsler T, et al. Division of labor during biofilm matrix production. Curr Biol. 2018;28:1903–13. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2018.04.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chai Y, Chu F, Kolter R, Losick R. Bistability and biofilm formation in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol. 2008;67:254–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.06040.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koo BM, Kritikos G, Farelli JD, Todor H, Tong K, Kimsey H, et al. Construction and analysis of two genome-scale deletion libraries for Bacillus subtilis. Cell Syst. 2017;4:291–305.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2016.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rueden CT, Schindelin J, Hiner MC, DeZonia BE, Walter AE, Arena ET, et al. ImageJ2: ImageJ for the next generation of scientific image data. BMC Bioinforma. 2017;18:529. doi: 10.1186/s12859-017-1934-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhu B, Stülke J. SubtiWiki in 2018: from genes and proteins to functional network annotation of the model organism Bacillus subtilis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:D743–8. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dragoš A, Martin M, Garcia CF, Kricks L, Pausch P, Heimerl T, et al. Collapse of genetic division of labour and evolution of autonomy in pellicle biofilms. Nat Microbiol. 2018;3:1451–60. doi: 10.1038/s41564-018-0263-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Helmann JD. Bacillus subtilis extracytoplasmic function (ECF) sigma factors and defense of the cell envelope. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2016;30:122–32. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2016.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim W, Racimo F, Schluter J, Levy SB, Foster KR. Importance of positioning for microbial evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:E1639–47. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1323632111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cao M, Helmann JD. The Bacillus subtilis extracytoplasmic-function σX factor regulates modification of the cell envelope and resistance to cationic antimicrobial peptides. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:1136–46. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.4.1136-1146.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Murray EJ, Strauch Ma, Stanley-Wall NR. SigmaX is involved in controlling Bacillus subtilis biofilm architecture through the AbrB homologue Abh. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:6822–32. doi: 10.1128/JB.00618-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hentzer M, Teitzel GM, Balzer GJ, Heydorn A, Molin S, Givskov M, et al. Alginate overproduction affects Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm structure and function. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:5395–401. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.18.5395-5401.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stilwell P, Lowe C, Buckling A. The effect of cheats on siderophore diversity in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Evol Biol. 2018;31:1330–9. doi: 10.1111/jeb.13307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kümmerli R, Brown SP. Molecular and regulatory properties of a public good shape the evolution of cooperation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:18921–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011154107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Niehus R, Picot A, Oliveira NM, Mitri S, Foster KR. The evolution of siderophore production as a competitive trait. Evolution. 2017;71:1443–55. doi: 10.1111/evo.13230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dumas Z, Kümmerli R. Cost of cooperation rules selection for cheats in bacterial metapopulations. J Evol Biol. 2012;25:473–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2011.02437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure and Dataset legends