Abstract

Objectives

The Imaginator study tested the feasibility of a short mental imagery-based psychological intervention for young people who self-harm, and used a stepped-wedge design to investigate effects on self-harm frequency reduction at 3 and 6 months.

Method

38 participants aged 16-25 were recruited via community self-referral and mental health services. Participants were randomised to immediate delivery of Functional Imagery Training (FIT) or usual care followed by delayed delivery after 3 months. FIT comprised two face-to-face sessions, five phone sessions and use of a smartphone app. Outcomes assessment was blind to allocation.

Results

Three-quarters of those who began treatment completed face-to-face sessions, and 57% completed five or more sessions in total. Self-harm frequency data was obtained on 76% of the sample at 3 months (primary outcome) and 63% at 6 months. FIT produced moderate reductions in self-harm frequency at 3 months after immediate (d = 0.65) and delayed delivery (d = 0.75). The Immediate FIT group maintained improvements from 3-6 months (d = 0.05). Participants receiving usual care also reduced self-harm (d = 0.47).

Conclusions

A brief mental imagery-based psychological intervention targeting self-harm in young people is feasible, and may comprise a novel transdiagnostic treatment for self-harm.

Keywords: self-harm, mental imagery, young people, digital app, psychological intervention

Introduction

Targeting self-harm behaviour in young people is a clinical, research and public health priority (Hawton et al., 2012; McPin Foundation, 2018). Lifetime prevalence rates for self-harm are now reported to be around 15-20% in young people under the age of 25 (Pisinger, Hawton, & Tolstrup, 2018; Swannell, Martin, Page, Hasking, & St John, 2014). Self-harm is associated with poor health and functional outcomes (Mars et al., 2014), and increased suicide risk (Zahl & Hawton, 2004), even after controlling for comorbid psychopathology and psychosocial risks (Whitlock et al., 2013; Wilkinson, Kelvin, Roberts, Dubicka, & Goodyer, 2011). It is a manifestation of distress present in both those with and without a mental illness and across different mental disorders (Mcmanus et al., 2016). Multiple studies have now confirmed a so-called “iceberg model” of self-harm (McMahon et al., 2014; Geulayov et al., 2018) whereby it is estimated that self-harm is far more common than suicide and most episodes of self-harm are undetected (the submerged part of the iceberg). Therefore, it is important to consider both the visible and the submerged levels of the “iceberg”.

Around 1 in 5 young people who self-harm are still doing it after 5 years (Carroll, Metcalfe, & Gunnell, 2014), often with increasing severity (Andrews, Martin, Hasking, & Page, 2013), whether they have sought help or not (Hawton, Rodham, Evans, & Weatherall, 2002). However, we do not have good predictors of who will continue self-harming over time (De Cates & Broome, 2016). To address the high personal and societal costs of this behaviour (Zahl & Hawton, 2004; Borschmann et al., 2017), we need to reach both those with a mental disorder and in contact with mental health services and those who are not in contact with mental health services (who may or may not have mental disorder).

Delivering support to young people who would like to reduce self-harm brings several challenges. Firstly, because treatments and services may exclude those who self-harm but do not have a ‘diagnosis’. Second, self-harm remains a mostly secretive behaviour and stigma attached to traditional psychiatric settings may exacerbate difficulties in help seeking (Wadman et al., 2017). Most evidence-based interventions targeting self-harm in young people have only shown limited effects to date and may reflect some of the above challenges (Ougrin, Tranah, Stahl, Moran, & Asarnow, 2015). Group-based dialectic-behavioural therapy (DBT) has been shown to reduce self-harm in adolescents in two high quality trials (Mehlum et al., 2016; McCauley et al., 2018) conducted in girls with emerging personality disorder. Such interventions may not be applicable to those who would not like therapy in a group setting and are long and expensive (Wilkinson, 2018). Other interventions in adolescents show promise, but require replication (e.g. mentalisation-based therapy, Rossouw & Fonagy, 2012; for a review, Cox & Hetrick, 2017). Studies in adults indicate that cognitive-behavioural therapies (CBTs) including brief versions (3-5 sessions) are effective in reducing frequency of self-harm (for a review, Hawton, Witt, Salisbury, et al., 2016), but data is limited to participants following their presentation to a health service (Hawton, Witt, Salisbury, et al., 2016).

Hence, there is a compelling need for treatment innovation that: 1) focuses on self-harm per se, taking a transdiagnostic approach rather than one focused only on specific diagnostic groups; and 2) can be easily delivered outside standard mental health services and treatment formats in order to minimize stigmatization and be more attractive to young people who are ‘in the submerged part of the iceberg’.

Treatments that draw on novel mechanistic hypotheses offer new ways to innovate psychological treatment, as these may help target and modify underlying processes maintaining symptoms (Holmes et al., 2018). Emerging evidence suggests that dysfunctional mental imagery may play a role in self-harm behaviour as both an emotional and motivational driver, similar to other psychopathology (Holmes, Geddes, Colom, & Goodwin, 2008; May, Andrade, & Kavanagh, 2015; Hales, Deeprose, Goodwin, & Holmes, 2011). Mental imagery is the experience commonly referred to as “seeing through the mind’s eye”, a form of “weak perception” (Pearson, Naselaris, Holmes, & Kosslyn, 2015). Individuals who self-harm report vivid imagery of hurting themselves, such as details of tools, or of the consequence (blood gushing), or the sensory impression conveying the intense sense of relief generated by the actual act. This type of self-harm imagery has been identified in community and student samples (McEvoy, Hayes, Hasking, & Rees, 2017; Hasking, Di Simplicio, McEvoy, & Rees, 2018; Weßlau, Cloos, Höfling, & Steil, 2015; Batey, May, & Andrade, 2010). Furthermore, imagery-based appraisals of the behavior (e.g. “this is stressful and wrong” or “this will make me feel better”) may contribute to acting or not acting on urges to self-harm (McEvoy et al., 2017). For example, a daily diary study showed that self-harm images are more compelling and comforting on the days when individuals self-harm than on days when they do not (Cloos, Di Simplicio, Hammerle, & Steil, under review). Mental imagery-based interventions that harness alternative, functional emotional and motivational imagery could therefore hold potential to help individuals develop more adaptive behaviour instead of self-harm. Rather than engaging in repetitive maladaptive imagery, they may rehearse more adaptive imagery instead.

Functional Imagery Training (FIT, Kavanagh, Andrade, May, & Connor, 2014) encourages participants to use functional imagery during a motivational interview (Miller & Rollnick, 2002). If they are committed to making a behaviour change, it teaches them to use motivational imagery in their natural environment as a way to accentuate proximal incentives, articulate plans and strengthen self-efficacy. It is based on a cognitive theory of desire and motivation (Elaborated Intrusion Theory, Kavanagh, Andrade, & May, 2005) and a related body of research (e.g. May, Kavanagh, & Andrade, 2015). FIT has already obtained empirical support in elite sporting performance (Rhodes, May, Andrade, & Kavanagh, 2018), dietary control (Andrade, Khalil, Dickson, May, & Kavanagh, 2016) and weight reduction (Solbrig et al., 2018).

In this study (called “Imaginator”), we adapted a face-to-face FIT protocol to help young people develop more adaptive behavioural alternatives to self-harm using functional mental imagery. We combined 2 face-to-face sessions with a smartphone app (the Imaginator app), which was co-developed with a group of young people who had lived experience of self-harm. The app aimed to enhance the focus on self-management for an age group where individuals strive for autonomy and value understanding how they can best help themselves (McPin Foundation, 2018). We also hoped this would engage more young people, given their familiarity (Ofcom, 2015) and expressed preference for phone apps (Dubad, Winsper, Meyer, Livanou, & Marwaha, 2018; Slater, Campbell, Stinson, Burley, & Briggs, 2017).

The primary aims of the Imaginator study were to: (a) assess the feasibility of recruitment and delivery of a brief psychological intervention, FIT, to reduce self-harm in a sample of young people aged 16-25; and (b) investigate effects at 3 and 6 months on the self-harm frequency, self-harm severity and self-efficacy for control over self-harm, comparing usual care (UC) plus FIT that was delivered either immediately (Immediate FIT) or after 3 months (Delayed FIT). We also: (c) explored whether retention in therapy and change in the self-harm frequency after FIT were associated with participants’ baseline characteristics. In particular, we were interested in examining associations between changes in self-harm frequency and self-harm cognitions at baseline, including mental imagery.

Methods

Ethical approval for the study was given by the NHS REC Bromley South: 16/LO/1311. The study was preregistered on Clinicaltrials.gov: NCT02914847.

Study design

This was an assessor-blind randomised controlled proof-of-concept feasibility trial with a stepped wedge design, comparing immediate Functional Imagery Training plus usual care (Immediate FIT) with Delayed FIT (where only usual care was received over the initial 3 months). This was followed by examining whether effects of Immediate FIT were maintained and effects of FIT could be replicated in the Delayed FIT condition between 3 and 6 months.

Participants

Participants were recruited via: (a) self-referral from the community via posters and social media and (b) direct referral from primary care services (general practitioners, psychology), secondary mental health care services, or university/school counsellors. Inclusion criteria were: aged 16-25; adequate English fluency; at least two episodes of self-harm in the previous 3 months; not currently psychotic; no current substance dependence; not under care of the local mental health services personality disorders team or crisis resolution and home treatment team; and not taking part in other research on treatment of self-harm.

Measures

Screening measures

Socio-demographic and clinical measures were collected via: the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI, Sheehan et al., 1998), the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS, Posner et al., 2011), the Young People Service Use Schedule (YP-SUS), a semi-structured interview adapted from clinical trials in adolescents (Goodyer et al., 2008) and routine NHS clinical records.

Primary outcome

Self-harm frequency was assessed by utilising the open-ended question: “In the last 3 months, have you tried to hurt yourself on purpose? If yes, how many times approximately?” Cues related to life events were used to help participants remember the last 3 episodes of self-harm (timing, methods and characteristics, any intervention received) and whether the nature and frequency of these episodes was typical of the last 3 months. This method (Timeline Followback, Sobell & Sobell, 2008) has been used reliably for substance use frequency estimation (Robinson, Sobell, Sobell, & Leo, 2014) and provided a retrospective estimate of the total number of self-harm episodes over a 3-month period. Self-harm severity was assessed by asking participants: “In the last 3 months, how severe was the worst injury that you inflicted on yourself? Can you list all the ways that you have used to harm yourself in the last 3 months?”. Answers were rated using an adaptation of the Clinician-rated Severity of Non-suicidal Self-Injury Scale (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), where non-severe = injuries not requiring intervention; severe = injuries requiring surgical treatment or medical intervention; and very severe = injuries requiring resuscitation / intensive care unit treatment. The total number of methods used to self-harm was also recorded.

Secondary outcomes

Self-harm cognitions

Self-Efficacy for Control (SEC) of self-harm. Participants were asked: ‘If you felt each level of distress below, how confident are you that you would not self-harm?’ For each level of distress, from 0 (not at all) to 10 (extremely), participants rated their self-efficacy from 0 (not at all confident I wouldn’t harm myself) to 100 (absolutely confident I wouldn’t self-harm). Participants’ confidence over the 11 items was averaged to calculate Self-Efficacy Strength, and the highest distress at which they were at least 50% sure they will not harm themselves formed their Self-Efficacy Level (Bandura & Bandura, 2006).

Self-Harm Imagery Interview adapted from (Hales et al., 2011): This interview investigated mental images that occur at the time of undertaking self-harm (whether the content is of self-harm or not; from now on referred to as ‘self-harm related imagery’). Participants were asked to bring to mind briefly the most typical or recurrent image associated with recent self-harm episodes and report its content (see Supplementary Material). They were then asked to rate the extent to which they usually experience each emotion on the Positive and Negative Affective Schedule (PANAS, Watson & Clark, 1988) right after the self-harm related imagery occurs (‘immediately after the image’). Finally, they were asked to rate imagery characteristics (vivid / compelling / controllable / distressing / comforting) on a 1 (‘not at all’) to 9 (‘extremely’) scale. Ratings on the PANAS were summed to form the scores for positive and negative affect at the time of self-harm related imagery.

The Craving Experience Questionnaire for Self-Harm (CEQ-SH), adapted from (May et al., 2014), assessed Frequency and Strength of desires to self-harm over the previous week, via 11 items giving sub-scales of Intensity, Imagery and Intrusiveness (from 0, not at all, to 10, constantly). Items were averaged to provide a summary score.

The Strength of Motivation for reducing Self-Harm (SM-SH) scale assessed motivation to control self-harm (Robinson, Kavanagh, Connor, May & Andrade, 2016; Parham et al., 2017) via 12 items rating the strength of their motivational cognitions “right now”, from 0 (never) to 10 (constantly). Items were averaged to provide a summary score.

Affect was measured with the Depression Anxiety and Stress Scales Brief Version (DASS-21; Henry & Crawford, 2005).

General mental imagery characteristics were assessed via the Impact of Future Events Scale (IFES; Deeprose & Holmes, 2010) assessing the presence and emotional impact of prospective mental imagery, and the Plymouth Sensory Imagery Questionnaire (PSI-Q; Andrade, May, Deeprose, Baugh, & Ganis, 2014) assessing the ability to generate vivid imagery.

Mental health services use data was collected from routine NHS clinical records of local mental health services on the number of contacts with acute emergency and urgent mental health services over 6 months before and after the baseline assessment.

Interventions

All participants in the study had access to usual care, which could include psychiatric assessment, pharmacotherapy, psychological interventions and/or counselling.

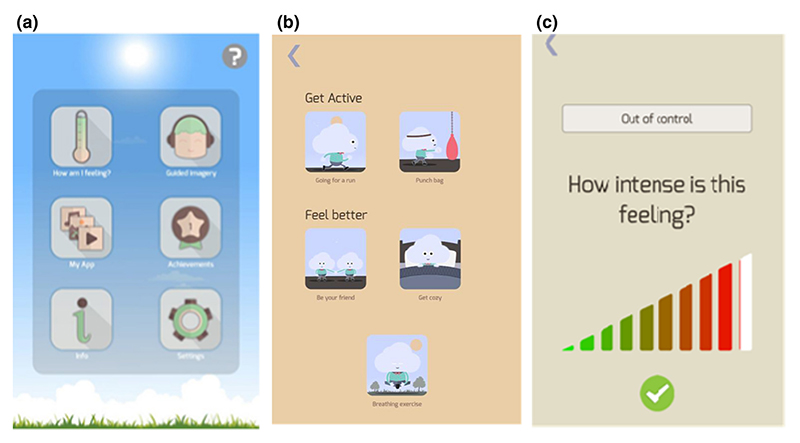

Functional Imagery Training (FIT) comprised of two face-to-face sessions (90 mins each), and five phone support calls (each 15-30 mins) over 8 weeks, delivered in either a research centre, a general hospital or a charity’s location. The FIT protocol (Kavanagh, Connolly, Andrade, & May, 2016) had the following elements: a) formulation of personal motives for addressing self-harm behaviours; b) motivational interviewing combined with mental imagery to enhance motivation to change; c) refinement of goals for change and strategies to achieve them (including imagery-based emotion regulation) and d) practice of functional imagery to support goal achievement. At the end of the second FIT session, participants downloaded the Imaginator app on their smartphone (or a smartphone provided by the researchers) and were instructed how the app could be used to support the plan developed in session. The app included audios guiding participants to imagine adaptive activities, a “how are you feeling” thermometer to rate emotional states, followed by suggestions of behaviours to address moderate distress, personalisation via upload of media, gamification via a reward badge system and the ability to set basic reminders to use the app via notifications (see Figure 2). Phone support calls reviewed successful or problematic use of imagery-based strategies and gave suggestions on how to personalise the app, facilitate its use, and maximise its impact.

Figure 2.

Procedures

Baseline assessment

After giving informed consent, eligible participants completed the screening measures and primary and secondary outcomes measures. At the end of the baseline assessment session, participants were assigned to receive FIT either immediately (Immediate FIT) or after 3 months (Delayed FIT) via a randomisation code independently prepared by the study statistician. Participants were informed of the assigned intervention by the psychiatrist who delivered the therapy sessions. Participants repeated measures of craving and motivation (CEQ-SH, May et al., 2014; SM-SH, Robinson et al., 2016) in the second FIT session.

Follow up assessments

A research assistant blind to treatment allocation conducted follow-up assessments of self-harm frequency and severity (primary outcomes), and self-efficacy for control of self-harm (secondary outcome) over the phone. Participants were also asked about any other mental health support they had received since the last assessment. All other secondary outcome measures were collected online. At the end of study, participants were reimbursed for the time employed to complete the research assessments (£6/hour).

Statistical analyses

The target sample size for the study was 40 recruited participants, allowing for an estimated 25% drop-out. This study was designed as a feasibility study, to provide an estimate of the differential effect size of the intervention, which could support planning of the sample size for a full-scale trial. The target sample was consistent with sample sizes in similar proof-of-concept research on novel psychological interventions (Litz, Engel, Bryant, & Papa, 2007).

Feasibility was assessed by calculating the average number of FIT sessions completed by participants, the percentage of participants completing different components of the intervention and the percentage who completed the 3- and 6-months assessments of the primary outcomes. Differences between conditions at baseline were assessed using t- tests, Mann-Whitney tests or chi-squares as appropriate. To obtain estimates of effect sizes for the primary outcome using intention-to-treat, we used a generalized linear mixed model with a Poisson distribution, with the number of self-harm episodes as the dependent variable, subjects as a random effect with time (baseline/3 months/6 months) and condition (Immediate FIT / Delayed FIT) as fixed effects. The focal effects involved the interaction of time and condition. Effect sizes were calculated using: Cohen’s d = T * √(1/N1 + 1/N2), where T= t of within-group comparison between baseline/3 months/6 months, N1 = n in Immediate FIT group and N2 = n in Delayed FIT group. For secondary outcomes of continuous data for which a linear distribution is assumed a general linear model analysis with the same independent factors was planned. Exploratory analyses using Pearson correlations and t-tests examined associations between number of FIT sessions completed (feasibility) and individual characteristics at baseline. Exploratory analyses using Pearson and Spearman Rank correlations were conducted to identify individual characteristics at baseline 1) associated with self-harm frequency at baseline and 2) associated with changes in self-harm frequency after FIT. A self-harm change variable was calculated by subtracting the number of self-harm episodes over 3 months at baseline from the number of self-harm episodes over 3 months after FIT (i.e. from baseline to 3 months in Immediate FIT, 3 to 6 months in Delayed FIT). To adjust for non-linear distribution of data, outliers > 3SD were winsorised.

Results

Recruitment and sample characteristics at baseline assessment

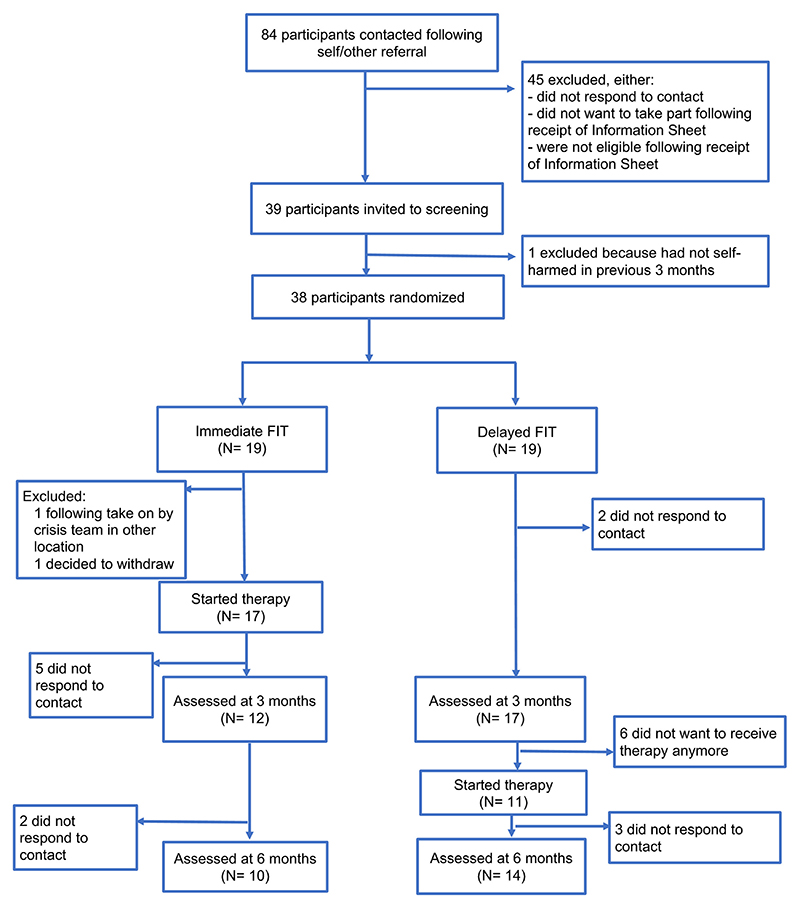

We received 84 referrals over 7 months (recruitment rate: 5.4/month) from both community and clinicians. Thirty-eight participants (31 females and 7 males) were recruited, 25 (65%) of which, importantly, had never had any previous psychological treatment. Details are reported in Figure 1 and Supplementary Material. Nineteen participants were randomly allocated to Immediate FIT and 19 to Delayed FIT. Thirty-six self-identified as white, 1 asian, and 1 mixed – white and black Caribbean. There were no significant difference in clinical and services use (Table 1), socio-demographic (Table 1 Supplementary Material), self-harm cognitions, general mental imagery and affect (Table 2 Supplementary Material) measures at baseline between the two groups.

Figure 1.

Table 1. Clinical characteristics and mental health service use of participants recruited to the Imaginator study at baseline assessment.

| Immediate FIT | Delayed FIT | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MINI diagnosis (lifetime) | N | % | N | % |

| Major Depressive Episode | 11 | 57.9 | 13 | 68.4 |

| Dysthymia | 9 | 47.4 | 5 | 26.3 |

| (Hypo)manic Episode | 6 | 31.6 | 2 | 10.5 |

| Panic Disorder/Agoraphobia | 11 | 58 | 7 | 36.9 |

| Social Phobia | 10 | 52.6 | 9 | 50 |

| Obessive-Compulsive Disorder | 4 | 23.5 | 4 | 21.1 |

| Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder | 6 | 31.6 | 7 | 36.8 |

| Alcohol/substance Misuse Dependence | 6 | 31.6 | 2 | 10.5 |

| Eating Disorder | 2 | 11.8 | 1 | 5.3 |

| Generalised Anxiety Disorder | 3 | 15.8 | 4 | 21.1 |

| Mental Health (MH) services use | N | % | N | % |

| Under MH team care, current | 5 | 26.3 | 2 | 10.5 |

| Lifetime contact with MH services | 14 | 73.7 | 11 | 57.9 |

| Contacted emergency MH services (prior 6 months) | 9 | 47.4 | 8 | 44.4 |

Self-harm

The mean number of self-harm episodes over the previous 3 months was 19.4 (SD = 28.9; range: 2 - 124); of these, there was a mean of 2.0 (SD = 1.2; range: 1 - 6) different types of self-harm per participant (e.g. cutting, burning, overdoses). Twenty-four (63%) participants reported non-severe, 14 (37%) severe and none reported very severe self-harm (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Over the previous month, 33 (87%) had also experienced suicidal ideation, with 21 (55%) reporting making a suicidal plan, and 12 (32%) describing an active suicide attempt over the previous 3 months.

Self-harm cognitions

On the self-efficacy for control of self-harm measure, participants reported that on average across all distress levels, they felt 57% confident (SD = 16) that they would not self-harm. The highest level of distress at which they were at least 50% confident not to self-harm was rated at 5.9 on the 0-10 scale (SD = 2.1). Thirty-one participants (82%) reported a recurrent typical mental image prior to self-harming, of which 25 images were of self-harm, while the remainder included imagery of negative (e.g. being blanked by friends) or potentially traumatic (e.g. assault) events. Other self-harm cognitions, affect and general imagery measures are reported in Table 2 Supplementary Material.

Mental health services use

Based on routine clinical records, 17 (45%) participants had used emergency / urgent psychiatric services over the previous 6 months.

Associations between self-harm and other measures at baseline

Associations between individual characteristics at baseline (socio-demographic, clinical, self-harm cognitions, general mental imagery and affect) and self-harm frequency were explored. The number of self-harm episodes at baseline was only associated with self-harm cognitions, including self-harm related imagery. In particular, baseline self-harm frequency was negatively correlated with self-efficacy at controlling self-harm (self-efficacy strength: ρ = -.36, p = .025; self-efficacy level: ρ = -.44, p = .006), and positively correlated with levels of desire to self-harm on the CEQ (ρ = .52, p = .006) and with attentiveness to self-harm related imagery on the Self-Harm Imagery Interview (ρ = .41, p = .021).

Engagement and retention

Two participants allocated to the Immediate FIT condition dropped out prior to starting the intervention (Figure 1). Six participants in the Delayed FIT group decided not to have the intervention when contacted after 3 months. Their reported reasons included having received/undergoing other therapy, logistical reasons, and feeling they no longer needed the intervention. Of those starting therapy, 23 (77%) completed at least the 2 face-to-face sessions; 19 (63%) also completed at least 2 phone follow-up calls and 17 (57%) completed the intervention per protocol (5/7 sessions). The mean number of sessions completed was 4.6 (SD = 2.7). The number of sessions completed was positively associated with participants’ age (ρ = .35, p = .037). There were no other significant correlations between retention in treatment and individual characteristics at baseline (including diagnosis or general imagery ability).

Attrition for the outcome measures collected over the phone, including the primary outcome was 24% at 3 months and 37% at 6 months follow-up. Attrition for the online questionnaires was 50% at 3 months and 71% at 6 months, preventing their inclusion in analyses.

Concurrent treatment

There was no difference in intensity of usual care received alongside FIT between intervention groups: 17 (57%) participants had no other intervention. Six participants (17%) received low intensity care (e.g. outpatient psychiatric reviews) either during or after FIT. Eight (23%) received high intensity care (individual CBT, group DBT, counselling in school or via a charity) either during the waiting period before FIT, during or after FIT.

Primary outcomes: self-harm frequency and severity

The average number of self-harm episodes at 3 and 6 months within each condition is reported in Table 3. The generalized mixed model analysis revealed a significant main effect of time, but no statistically significant difference between treatment groups (time: F(2,85) = 5.36, p = .006, η2 = 0.11; time x intervention: F(2,85)=.94, p = .40, η2 = .022). Self-harm episodes were reduced between baseline and 3 months in both the Immediate FIT (t = 1.77, d = 0.65 [CI: 0.9 - 16.1]) and Delayed FIT group (t = 1.41, d = 0.47 [CI: -2.2 - 13.2]). Reduction in self-harm was maintained in the Immediate FIT group between 3 and 6 months (t = 0.13, d = 0.05 [CI: -7.3 - 8.4]). Self-harm episodes reduced in the Delayed FIT group between 3 and 6 months after receiving the intervention (t = 2.07, d = 0.75 [CI: 0.3 - 15.4]).

Maximum self-harm severity was also reduced over time, with no statistically significant differential change between groups (time: F(2,83)=12.74, p = <.001, η2 = 0.23; time x intervention: F(2,85)=.35, p = .71, η2 = .007). Self-harm severity was reduced between baseline and 3 months in both the Immediate FIT (t = 2.68, d = 1.01 [CI: 0.09 - 1.2]) and Delayed FIT group (t = 2.44, d = 0.81 [CI: 0.03 - 1.05]), and between 3 and 6 months in both the Immediate FIT group (t = 0.96, d = 0.41 [CI: -0.2 - 0.7]) and the Delayed FIT group (t = 0.61, d = 0.22 [CI: -0.3 - 0.5]). No participant reported episodes of very severe self-harm.

Secondary outcomes

Mental health services use

At 6 months follow-up, only 6 (17%) participants had received emergency or urgent psychiatric services care (11 fewer than at baseline, 28% reduction).

Self-efficacy at controlling self-harm

Self-efficacy measures showed a significant main effect of time (Strength: F(2,36) = 6.5, p = .004, η2 = .25.; Level: F(2,45) = 7.31, p = .002, η2 = .23), but no significant time x intervention interaction (F(2,36) = .042, p = .95, η2 = .002; Level: F(2,45) = .56, p = .58, η2 = .021). Details are reported in the Supplementary Material.

Prediction of response to FIT

Exploratory analyses indicated that greater self-harm frequency reduction after FIT was correlated with self-harm cognitions, clinical measures and general mental imagery at baseline. In particular, on the Self-harm Imagery Interview, response to FIT was associated with greater negative affect experienced immediately after self-harm related imagery (r = .47, p = .049), including greater nervousness (r = .46, p = .045) and jitteriness (r = .52, p = .022). A better treatment response was also seen in participants with greater baseline psychopathology, measured by higher number of diagnosis met on the MINI (r = .51, p = .013), and in those with a higher number of negative intrusive imagery measured on the IFES (r = .45, p = .047). Greater falls in self-harm frequency following FIT were associated with greater motivation to stop self-harm (r = .54, p = .017) measured on the SH-MS.

Discussion

This is the first study to test offering a brief imagery-based psychological intervention (FIT) for young people who self-harm, regardless of diagnosis and contact with mental health services.

First, our recruitment success from both health services and the general community indicates that FIT combining face-to-face contact, phone support and a digital app was met favourably by care professionals, young people accessing care and those in the community, including some who had never accessed available mental health support. The recruitment suggest that for some young people social media is an acceptable route into research and interventions for self-harm (Jarvi et al., 2013; Prescott, Hanley, & Ujhelyi, 2017).

Although initial engagement was strong in the referred sample (78% of referrals from health services were recruited), two-thirds of the self-referred sample that made initial contact did not attend the baseline assessment. Self-referring individuals who did not enter the study offered interesting insights for further treatment development. For example, some only wanted the Imaginator app but not the face-to-face sessions, suggesting a potential scope for an entirely digital-based intervention. Whether blended or digital interventions are preferable remains debatable. Systematic review evidence supports the role for therapist’s guidance to enhance adherence and effectiveness of mental health digital interventions for young people (Hollis et al., 2017), and the high incidence of suicidal ideation may suggest a need for caution in relation to dropping therapist contact.

Second, the fact that three-quarters of participants completed at least the first two (face-to-face) sessions was also very encouraging, although the level of phone follow-up completion (at 57%) left room for improvement. Notably, referral type had no impact on retention into therapy suggesting that this intervention could be implemented in different settings and for individuals from different layers of the ‘self-harm iceberg’ (Geulayov et al., 2018). Diagnosis also appeared to have no influence on retention rates, which was promising in terms of developing a transdiagnostic intervention. Interestingly, neither self-harm cognitions nor the ability to use mental imagery (Andrade, May, Deeprose, Baugh, & Ganis, 2014) influenced retention in therapy, although the small sample size means that this result should be interpreted with caution.

Third, our findings suggest that FIT may be a safe intervention for young people who self-harm, although this conclusion requires replication in a larger sample. Even though most participants reported making a suicidal plan in the previous month, there was no increase in use of urgent / emergency mental health services associated with receiving the intervention (including participants dropped out from phone follow-up assessments).

Finally, FIT provided reductions in self-harm episodes over 3 months with a medium effect size in the Immediate FIT condition, and gains were maintained at 6 months. When FIT was delivered after waiting in the Delayed FIT condition, reductions in self-harm were again observed with a moderate to large effect size. Individuals in the Delayed FIT condition receiving usual care over the first 3 months presented greater variability in self-harm change in that period, with a small to moderate effect size reduction. This is in keeping with the natural history of this behaviour, which tends to spontaneously diminish over time in some individuals (Moran et al., 2012). A key priority in self-harm research remains to identify reliable predictors of self-harm remission/repetition to optimize treatment delivery (De Cates & Broome, 2016). Reduction in self-harm in the Delayed FIT group while waiting may have also resulted from potential non-specific effects of the baseline assessment and taking part in a study, which may induce motivation to change. A small number of individuals also received high intensity interventions (such as DBT) during this period.

Exploratory observations indicated that FIT was equally effective on the primary outcome regardless of baseline self-harm frequency and possibly more so in those with more severe psychopathology. Future studies with larger samples are needed to clarify whether FIT could be a suitable intervention across the heterogeneous presentations of self-harm (from occasional to weekly frequency) or better for young people with comorbid mental disorders.

Our study also confirmed that self-harm related imagery is common and relevant to young people who self-harm across a variety of presentations, while previous studies were limited to students or community surveys (McEvoy et al., 2017; Weßlau et al., 2015). Most participants described their imagery as images of actual self-harm, from intrusive rapid pictures of their hand holding a blade, to mental ‘movies’ rehearsing every step of an action (e.g. taking pills out of a drawer, lining them up etc.), in line with growing evidence on the role of imagery in self-harm (Ng, Di Simplicio, McManus, Kennerley, & Holmes, 2016; Wetherall et al., 2018). Our exploratory analysis on associations between self-harm and baseline characteristics suggested that greater attentiveness to such self-harm imagery may be associated with engaging in self-harm. This is interesting in view of previous evidence that reduced aversion to self-harm stimuli (which may include internal mental representations) may predict self-harm behaviour (Franklin et al., 2014), and a game that increases aversion to self-harm pictures may reduce self-harm (Franklin et al., 2016). Consistently, we also found that FIT appeared more helpful in the presence of more negative intrusive future imagery and more negatively arousing self-harm-related imagery. We speculate that individuals who were more familiar with the emotional and motivational impact of imagery at baseline, and found this imagery distressing, may have been more motivated or found it easier to engage in alternative adaptive imagery (e.g. imagining an energetic bike ride, having ice cream and laughing with a friend, walking the dog under lush green trees). Whilst these are tentative observations, they open the way for future studies investigating mechanistic processes, including whether adaptive motivational imagery developed via FIT has a direct impact on self-harm behaviour, or operates indirectly by competing with self-harm imagery or changing its emotional appraisal (McEvoy, Hayes, Hasking, & Rees, 2017).

Finally, our study confirmed a role of self-efficacy cognitions in self-harm (Hasking, Whitlock, Voon, & Rose, 2017) and reported for the first time that craving may be relevant to engaging in self-harm. Whilst preliminary, these findings highlight a possible overlap between constructs relevant to addiction and self-harm (Blasco-Fontecilla et al., 2016; Sauder, Derbidge, & Beauchaine, 2015; Oldershaw et al., 2009), and support our rationale for developing an intervention adapted from work in alcohol dependence and including motivation-based strategies. Further research should investigate craving characteristics in self-harm and how this could be targeted by treatment.

Limitations

Our study was not powered to establish the actual efficacy of FIT, and did not include an active comparator, which is important to estimate reliable effect sizes that can inform treatment selection (Witt et al., 2018). While the FIT group showed a much larger effect size compared to usual care after 3 months, there was also a large degree of individual variation of effects (see CIs). This and the small sample size may have resulted in small estimates of group x time effects. A refinement of the intervention to reduce the variation in response might be needed for a further trial. While we have shown that FIT with the Imaginator app holds promise across the heterogeneous presentations of self-harm (age, setting, diagnosis, help-seeking), this also makes it challenging to identify a valid comparator for future studies. The small sample size means that the correlations in this paper need to be regarded with caution, and a test replication should be sought in a larger study. Another limitation in our study was high attrition in the secondary outcome data, which was collected online. Consequently, we could not measure whether FIT had any impact on other clinical outcomes, such as affect. We also did not assess symptoms of personality disorders. Retrospective exploration of routine clinical records revealed that a mention of borderline personality disorder was present in 14 individuals in the study. Finally, qualitative feedback interviews indicated a good acceptability for FIT (Aveyard et al., in prep), but we did not collect specific quantitative acceptability and usability data around the Imaginator app. It will be important to evaluate app use data in the future, to establish the relative impact and importance of the digital component of the Imaginator intervention.

Conclusions

In summary, we have shown that a brief imagery-based psychological intervention (Functional Imagery Training supported by the Imaginator smartphone app) targeting reductions in self-harm was well received by young people. We demonstrated that it is an acceptable treatment for those in the community and those who present to services across a range of self-harm and psychopathology presentations. Mental imagery-based approaches may hold promise as transdiagnostic, flexible, youth-focused interventions to expand our repertoire of treatment / self-management options and warrant further testing in larger populations.

Supplementary Material

Table 2. Self-harm episodes over 3 months, following Immediate Functional Imagery Training + Usual Care and Delayed Functional Imagery Training + Usual Care.

Reported values represent estimates from the generalised mixed-model analysis of number of self-harm episodes over the previous 3 months collected at baseline, 3 and 6 months follow up assessments.

| Immediate FIT | Delayed FIT | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | S.E. | CI (95%) | Mean | S.E. | CI (95%) | |

| Baseline | 18.9 | 7.5 | 8.5 - 41.7 | 19.9 | 7.7 | 9.2 - 43.1 |

| 3 months follow up | 11.3 | 6.2 | 3.8 - 33.6 | 14.4 | 6.7 | 5.7 - 36.1 |

| 6 months follow up | 10.8 | 6.2 | 3.4 - 33.7 | 6.6 | 4.6 | 1.7 - 26.3 |

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all study participants. We would like to thank the Young People Advisory Group and John Harper, AppShine ltd. CEO, for the enthusiastic work on developing the Imaginator app. For supporting recruitment and running of the study, we would like to thank: Dr Cathy Walsh, Dr Isabel Clare, all clinicians at the Cambridgeshire and Peterborough NHS Foundation Trust First Response Service, the Cambridgeshire and Peterborough NHS Foundation Trust Liaison Psychiatry team in Huntingdon, the Richmond Fellowship in Peterborough, Romsey Mill in Cambridge, Pinpoint Cambridgeshire, the Cambridge University Students Union, and all participating local Sixth Form Colleges and GP surgeries in Huntingdon and Cambridge.

Funding disclosure

This study was funded by an East of England Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research & Care | CLAHRC grant [EDD 24] and Cambridgeshire and Peterborough NHS Foundation Trust Research and Development funding to Martina Di Simplicio. Emily A. Holmes and Martina Di Simplicio were also funded by the Medical Research Council intramural programme to Emily A. Holmes previously at the MRC [MRC-A060-5PR50].

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

Martina Di Simplicio and Emily A. Holmes are co-authors of a book on imagery-based cognitive therapy (Guildford press, 2019)

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders 5. American Psychiatric Association; Washington DC: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Andrade J, May J, Deeprose C, Baugh S-J, Ganis G. Assessing vividness of mental imagery: The Plymouth Sensory Imagery Questionnaire. British Journal of Psychology. 2014;105(4):547–563. doi: 10.1111/bjop.12050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrade J, Khalil M, Dickson J, May J, Kavanagh DJ. Functional Imagery Training to reduce snacking: Testing a novel intervention for weight management based on Elaborated Intrusion theory. Appetite. 2016;100:256–262. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2016.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews T, Martin G, Hasking P, Page A. Predictors of Continuation and Cessation of Nonsuicidal Self-Injury. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2013;53:40–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aveyard B, Appiah-Kusi E, Barnicot K, Wilkinson P, Kavanagh DJ, Holmes EA, Di Simplicio M. Young people’s experiences of an imagery-based intervention targeting self-harm, supported by a digital app. (in preparation) [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A, Bandura A. In: Self-Efficacy Beliefs of Adolescents. Urdan T, Pajares F, editors. Information Age Publishing; Greenwich, Connecticut: 2006. Guide for Constructing Self-Efficacy Scale; pp. 307–337. [Google Scholar]

- Batey H, May J, Andrade J. Negative Intrusive Thoughts and Dissociation as Risk Factors for Self-Harm. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2010;40(1):35–49. doi: 10.1521/suli.2010.40.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blasco-Fontecilla H, Fernández-Fernández R, Colino L, Fajardo L, Perteguer-Barrio R, de Leon J. The Addictive Model of Self-Harming (Non-suicidal and Suicidal)Behavior. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2016;7:8. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2016.00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borschmann R, Becker D, Coffey C, Spry E, Moreno-Betancur M, Moran P, Patton GC. 20-Year Outcomes in Adolescents Who Self-Harm: a Population-Based Cohort Study. The Lancet Child and Adolescent Health. 2017;1(3):195–202. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(17)30007-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll R, Metcalfe C, Gunnell D. Hospital Presenting Self-Harm and Risk of Fatal and Non-Fatal Repetition: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(2):e89944. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloos M, Di Simplicio M, Hammerle F, Steil R. Mental images in the daily life of young adults with nonsuicidal self-injury disorder (NSSID) doi: 10.1186/s40479-019-0117-0. (under review) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox G, Hetrick S. Psychosocial interventions for self-harm, suicidal ideation and suicide attempt in children and young people: What? How? Who? and Where? Evidence Based Mental Health. 2017;20(2):35–40. doi: 10.1136/eb-2017-102667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Cates AN, Broome MR. Can we use neurocognition to predict repetition of self-harm, and why might this be clinically useful? A perspective. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2016 JAN;7:1–7. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2016.00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deeprose C, Holmes EA. An Exploration of Prospective Imagery: The Impact of Future Events Scale. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2010;38(02):201. doi: 10.1017/S1352465809990671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubad M, Winsper C, Meyer C, Livanou M, Marwaha S. A systematic review of the psychometric properties, usability and clinical impacts of mobile mood-monitoring applications in young people. Psychological Medicine. 2018;48(2):208–228. doi: 10.1017/S0033291717001659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin JC, Puzia ME, Lee KM, Prinstein MJ. Low implicit and explicit aversion toward self-cutting stimuli longitudinally predict nonsuicidal self-injury. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2014;123(2):463–469. doi: 10.1037/a0036436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin JC, Fox KR, Franklin CR, Kleiman EM, Ribeiro JD, Jaroszewski AC, Nock MK. A Brief Mobile App Reduces Nonsuicidal and Suicidal Self-Injury: Evidence From Three Randomized Controlled Trials. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2016;84(6):544–557. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geulayov G, Mcdonald KC, Foster H, Keith P, Hawton K. Incidence of suicide, hospital-presenting non-fatal self-harm, and community-occurring non-fatal selfharm in adolescents in England (the iceberg model of self-harm): a retrospective study. Articles Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5:167–174. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30478-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hales SA, Deeprose C, Goodwin GM, Holmes EA. Cognitions in bipolar affective disorder and unipolar depression: imagining suicide. Bipolar Disorders. 2011;13(7-8):651–661. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2011.00954.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasking P, Whitlock J, Voon D, Rose A. A cognitive-emotional model of NSSI: using emotion regulation and cognitive processes to explain why people self-injure. Cognition and Emotion. 2017;31(8):1543–1556. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2016.1241219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasking PA, Di Simplicio M, McEvoy PM, Rees CS. Emotional cascade theory and non-suicidal self-injury: the importance of imagery and positive affect. Cognition and Emotion. 2018;32(5):941–952. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2017.1368456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawton K, Rodham K, Evans E, Weatherall R. Deliberate self-harm in adolescents: self-report survey in schools in England. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed) 2002;325(7374):1207–1211. doi: 10.1136/BMJ.325.7374.1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawton K, Bergen H, Kapur N, Cooper J, Steeg S, Ness J, Waters K. Repetition of self-harm and suicide following self-harm in children and adolescents: findings from the Multicentre Study of Self-harm in England. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2012;53(12):1212–1219. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawton K, Witt KG, Salisbury TLT, Arensman E, Gunnell D, Hazell P, van Heeringen K. Psychosocial interventions following self-harm in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(8):740–750. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30070-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry JD, Crawford JR. The short-form version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21): construct validity and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. The British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2005;44(Pt 2):227–239. doi: 10.1348/014466505X29657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes EA, Geddes JR, Colom F, Goodwin GM. Mental imagery as an emotional amplifier: Application to bipolar disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2008;46(12):1251–1258. doi: 10.1016/J.BRAT.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes EA, Ghaderi A, Harmer CJ, Ramchandani PG, Cuijpers P, Morrison AP, Craske MG. The Lancet Psychiatry Commission on psychological treatments research in tomorrow’s science. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(3):237–286. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30513-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvi S, Jackson B, Swenson L, Crawford H. The Impact of Social Contagion on Non-Suicidal Self-Injury: A Review of the Literature. Archives of Suicide Research. 2013;17(1):1–19. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2013.748404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavanagh DJ, Andrade J, May J. Imaginary relish and exquisite torture: The elaborated intrusion theory of desire. Psychological Review. 2005;112(2):446–467. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.112.2.446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavanagh DJ, Andrade J, May J, Connor JP. Motivational interventions may have greater sustained impact if they trained imagery-based self-management. Addiction. 2014;109(7):1062–1063. doi: 10.1111/add.12507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavanagh DJ, Connolly J, Andrade J, May J. Functional Imagery Training manual for telephone-based treatment of alcohol misuse. Queensland University of Technology; Brisbane: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lilley R, Owens D, Horrocks J, House A, Noble R, Bergen H, Kapur N. Hospital care and repetition following self-harm: Multicentre comparison of self-poisoning and self-injury. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;192(06):440–445. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.043380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litz BT, Engel CC, Richard Bryant MA, Papa A. Article A Randomized, Controlled Proof-of-Concept Trial of an Internet-Based, Therapist-Assisted Self-Management Treatment for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:1676–1683. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06122057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mars B, Heron J, Crane C, Hawton K, Lewis G, Macleod J, Gunnell D. Clinical and social outcomes of adolescent self-harm: population-based birth cohort study. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed) 2014;349:g5954. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g5954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May J, Andrade J, Kavanagh DJ, Feeney GFX, Gullo MJ, Statham DJ, Connor JP. The Craving Experience Questionnaire: a brief, theory-based measure of consummatory desire and craving. Addiction. 2014;109(5):728–735. doi: 10.1111/add.12472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May J, Andrade J, Kavanagh DJ. An Imagery-Based Road Map to Tackle Maladaptive Motivation in Clinical Disorders. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2015;6:14. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2015.00014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCauley E, Berk MS, Asarnow JR, Adrian M, Cohen J, Korslund K, Linehan MM. Efficacy of dialectical behavior therapy for adolescents at high risk for suicide a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(8):777–785. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEvoy PM, Hayes S, Hasking PA, Rees CS. Thoughts, images, and appraisals associated with acting and not acting on the urge to self-injure. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 2017;57:163–171. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2017.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon EM, Keeley H, Cannon M, Arensman E, Perry IJ, Clarke M, Corcoran P. The iceberg of suicide and self-harm in Irish adolescents: a populationbased study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2014;49(12):1929–1935. doi: 10.1007/s00127-014-0907-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mcmanus S, Hassiotis A, Jenkins R, Dennis M, Aznar C, Appleby L. Suicidal thoughts, suicide attempts, and self-harm. ADULT PSYCHIATRIC MORBIDITY SURVEY 2014 CHAPTER. 2016 https://files.digital.nhs.uk/publicationimport/pub21xxx/pub21748/apms-2014-suicide.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- McPin Foundation. Right People, Right Questions. Research Priorities for Children and Young People’s Mental Health: Interventions and Services. 2018. http://mcpin.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/McPin-Foundation-RPRQ-Main-Report.pdf

- Mehlum L, Ramberg M, Tørmoen AJ, Haga E, Diep LM, Stanley BH, Grøholt B. Dialectical Behavior Therapy Compared With Enhanced Usual Care for Adolescents With Repeated Suicidal and Self-Harming Behavior: Outcomes Over a One-Year Follow-Up. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2016;55(4):295–300. doi: 10.1016/J.JAAC.2016.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change. 2nd. Guilford Press; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Moran P, Coffey C, Romaniuk H, Olsson C, Borschmann R, Carlin JB, Patton GC. The natural history of self-harm from adolescence to young adulthood: a population-based cohort study. The Lancet. 2012;379(9812):236–243. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61141-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng RMK, Di Simplicio M, McManus F, Kennerley H, Holmes EA. ‘Flash-forwards’ and suicidal ideation: A prospective investigation of mental imagery, entrapment and defeat in a cohort from the Hong Kong Mental Morbidity Survey. Psychiatry Research. 2016;246:453–460. doi: 10.1016/J.PSYCHRES.2016.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ofcom. The Communications Market Report 2015 2015

- Oldershaw A, Grima E, Jollant F, Richards C, Simic M, Taylor L, Schmidt U. Decision making and problem solving in adolescents who deliberately self-harm. Psychological Medicine. 2009;39(1):95–104. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708003693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ougrin D, Tranah T, Stahl D, Moran P, Asarnow JR. Therapeutic Interventions for Suicide Attempts and Self-Harm in Adolescents: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2015;54(2):97–107.:e2. doi: 10.1016/J.JAAC.2014.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parham S, Kavanagh DJ, Gericke CA, King N, May J, Andrade J. Assessment of Motivational Cognitions in Diabetes Self-Care: the Motivation Thought Frequency Scales for Glucose Testing, Physical Activity and Healthy Eating. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2017;24(3):447–456. doi: 10.1007/s12529-016-9607-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson J, Naselaris T, Holmes EA, Kosslyn SM. Mental Imagery: Functional Mechanisms and Clinical Applications. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2015;19(10):590–602. doi: 10.1016/J.TICS.2015.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisinger VSC, Hawton K, Tolstrup JS. School-and class-level variation in self-harm, suicide ideation and suicide attempts in Danish high schools. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health. 2018 March 1; doi: 10.1177/1403494818799873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, Brent DA, Yershova KV, Oquendo MA, Mann JJ. The Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale: Initial Validity and Internal Consistency Findings From Three Multisite Studies With Adolescents and Adults. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;168(12):1266–1277. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10111704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prescott J, Hanley T, Ujhelyi K. Peer Communication in Online Mental Health Forums for Young People: Directional and Nondirectional Support. JMIR Mental Health. 2017;4(3):e29. doi: 10.2196/mental.6921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes J, May J, Andrade J, Kavanagh DJ. Enhancing grit through functional imagery training in professional soccer. The Sport Psychologist. 2018;32:220–225. doi: 10.1123/tsp.2017-0093. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson SM, Sobell LC, Sobell MB, Leo GI. Reliability of the Timeline Followback for cocaine, cannabis, and cigarette use. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2014;28(1):154–162. doi: 10.1037/a0030992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson N, Kavanagh D, Connor J, May J, Andrade J. Assessment of motivation to control alcohol use: The motivational thought frequency and state motivation scales for alcohol control. Addictive Behaviors. 2016;59:1–6. doi: 10.1016/J.ADDBEH.2016.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossouw TI, Fonagy P. Mentalization-Based Treatment for Self-Harm in Adolescents: A Randomized ControlledTrial. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2012;51(12):1304–1313.:e3. doi: 10.1016/J.JAAC.2012.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauder CL, Derbidge CM, Beauchaine TP. Neural responses to monetary incentives among self-injuring adolescent girls. Development and Psychopathology. 2015;28(1):277–291. doi: 10.1017/S0954579415000449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders KE, Smith KA. Interventions to prevent self-harm: What does the evidence say? Evidence-Based Mental Health. 2016;19(3):69–72. doi: 10.1136/eb-2016-102420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scoliers G, Portzky G, Madge N, Hewitt A, Hawton K, de Wilde EJ, van Heeringen K. Reasons for adolescent deliberate self-harm: a cry of pain and/or a cry for help? Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2009;44(8):601–607. doi: 10.1007/s00127-008-0469-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, Dunbar GC. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): The Development and Validation of a Structured Diagnostic Psychiatric Interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1998;59(20):22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slater H, Campbell JM, Stinson JN, Burley MM, Briggs AM. End User and Implementer Experiences of mHealth Technologies for Noncommunicable Chronic Disease Management in Young Adults: Systematic Review. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2017;19(12):e406. doi: 10.2196/jmir.8888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell L, Sobell M. In: Textbook of Psychiatric Measures. American Psychiatric Association, editor. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 2008. Alcohol Timeline Followback (TLFB) pp. 477–479. [Google Scholar]

- Solbrig L, Whalley B, Kavanagh DJ, May J, Parkin T, Jones R, Andrade J. Functional Imagery Training versus Motivational Interviewing for weight loss: A randomised controlled trial of brief individual interventions for overweight and obesity. International Journal of Obesity. 2018 doi: 10.1038/s41366-018-0122-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swannell SV, Martin GE, Page A, Hasking P, St John NJ. Prevalence of Nonsuicidal Self-Injury in Nonclinical Samples: Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis and Meta-Regression. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2014;44(3):273–303. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadman R, Clarke D, Sayal K, Vostanis P, Armstrong M, Harroe C, Townsend E. An interpretative phenomenological analysis of the experience of self-harm repetition and recovery in young adults. Journal of Health Psychology. 2017 doi: 10.1177/1359105316631405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA. Development and Validation of Brief Measures of Positive and Negative Affect: The PANAS Scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54(6):1063–1070. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weßlau C, Cloos M, Höfling V, Steil R. Visual mental imagery and symptoms of depression-results from a large–scale web-based study. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15(1):308. doi: 10.1186/s12888-015-0689-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetherall K, Cleare S, Eschle S, Ferguson E, O’Connor DB, O’Carroll RE, O’Connor RC. From ideation to action: Differentiating between those who think about suicide and those who attempt suicide in a national study of young adults. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2018;241:475–483. doi: 10.1016/J.JAD.2018.07.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitlock J, Muehlenkamp J, Eckenrode J, Purington A, Baral Abrams G, Barreira P, Kress V. Nonsuicidal Self-Injury as a Gateway to Suicide in Young Adults. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2013;52(4):486–492. doi: 10.1016/J.JADOHEALTH.2012.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson P, Kelvin R, Roberts C, Dubicka B, Goodyer I. Clinical and Psychosocial Predictors of Suicide Attempts and Nonsuicidal Self-Injury in the Adolescent Depression Antidepressants and Psychotherapy Trial (ADAPT) American Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;168(5):495–501. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10050718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson PO, Qiu T, Neufeld S, Jones PB, Goodyer IM. Sporadic and recurrent non-suicidal self-injury before age 14 and incident onset of psychiatric disorders by 17 years: prospective cohort study. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2018;212(4):222–226. doi: 10.1192/bjp.2017.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson PO. Dialectical Behavior Therapy—A Highly Effective Treatment for Some Adolescents Who Self-harm. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(8):786. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witt K, de Moraes DP, Salisbury TT, Arens man E, Gunnell D, Hazell P, Hawton K. Treatment as usual (TAU) as a control condition in trials of cognitive behavioural-based psychotherapy for self-harm: Impact of content and quality on outcomes in a systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2018;235:434–447. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.04.025. April. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahl DL, Hawton K. Repetition of deliberate self-harm and subsequent suicide risk: Long-term follow-up study of 11 583 patients. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;185(01):70–75. doi: 10.1192/bjp.185.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.