Abstract

Some infectious diseases, including COVID-19, can undergo airborne transmission. This may happen at close proximity, but as time indoors increases, infections can occur in shared room air despite distancing. We propose two indicators of infection risk for this situation, that is, relative risk parameter (Hr) and risk parameter (H). They combine the key factors that control airborne disease transmission indoors: virus-containing aerosol generation rate, breathing flow rate, masking and its quality, ventilation and aerosol-removal rates, number of occupants, and duration of exposure. COVID-19 outbreaks show a clear trend that is consistent with airborne infection and enable recommendations to minimize transmission risk. Transmission in typical prepandemic indoor spaces is highly sensitive to mitigation efforts. Previous outbreaks of measles, influenza, and tuberculosis were also assessed. Measles outbreaks occur at much lower risk parameter values than COVID-19, while tuberculosis outbreaks are observed at higher risk parameter values. Because both diseases are accepted as airborne, the fact that COVID-19 is less contagious than measles does not rule out airborne transmission. It is important that future outbreak reports include information on masking, ventilation and aerosol-removal rates, number of occupants, and duration of exposure, to investigate airborne transmission.

Keywords: COVID-19, airborne transmission, outbreaks, indoor air, risk assessment, mitigation

Introduction

Some respiratory infections can be transmitted through the airborne pathway in which aerosol particles (<100 μm) are shed by infected individuals and inhaled by others, causing disease in susceptible individuals.1–4 It is widely accepted that measles, tuberculosis, and chickenpox are transmitted in this way,5,6 and acceptance is growing that this is a major and potentially the dominant transmission mode of COVID-19.7–13 There is substantial evidence that smallpox,14 influenza,3 SARS,15 MERS,6 and rhinovirus16 are also transmitted via inhalation of aerosols.

There are three airborne transmission scenarios of interest in which infectious and susceptible people: (a) are in close proximity to each other (<1–2 m), so-called “short-range airborne transmission,” with overlapping breathing zones, 17 which is effectively mitigated by physical distancing; (b) are sharing air in the same room, that is, “shared-room airborne;” and (c) are not sharing a room, far apart in a very large room, or even in different buildings as in the Amoy Gardens SARS outbreak, called “longer-distance airborne transmission.”15 Often (b) and (c) are lumped together under “long-range transmission,” but in Scenario (c) transport of pathogen-containing air is more complex, so that the approximation of well-mixed air is less valid. It is thus useful to separate these scenarios given the substantial differences in the risk of these situations and actions needed to abate the risk of transmission.

Airborne diseases vary widely in transmissibility, but all of them are most easily transmitted in a short range because of the higher concentration of pathogen-containing aerosols close to the infected person. For SARS-CoV-2, a pathogen of initially moderate infectivity (more recently increased by some variants such as Delta or Omicron), many instances have been reported implicating transmission in shared indoor spaces. Indeed, multiple outbreaks of COVID-19 have been reported in crowded spaces that were relatively poorly ventilated and that were shared by many people for periods of half an hour or longer. Examples include choir rehearsals,11 religious services,18 buses,19 workshop rooms,19 restaurants,4,20 and gyms,21 among others. There are only a few documented cases of longer-distance transmission of SARS-CoV-2, in buildings. 22–24 However, cases of longer-distance transmission are harder to detect as they require contact tracing teams to have sufficient data to connect cases together and rule out infection acquired elsewhere. Historically, it was only possible to prove longer-distance transmission in the complete absence of community transmission (e.g., ref 14).

Being able to quickly assess the risk of infection for a wide variety of indoor environments is of utmost importance given the impact of the continuing pandemic (and the risk of future pandemics) on so many aspects of life in almost every country of the world. We urgently need to improve the safety of the air that we breathe across a range of environments including child-care facilities, kindergartens, schools, colleges, shops, offices, homes, eldercare facilities, factories, public and private transportation, restaurants, gyms, libraries, cinemas, concert halls, places of worship, and mass outdoor events across different climates and socio-economic conditions. There is limited evidence to specify to minimum ventilation rates required to mitigate airborne transmission in buildings.25 However, data from COVID-19 outbreaks consistently show that a large fraction of buildings worldwide have very low ventilation rates despite the requirements set in national building standards. A host of policy questions—from how to safely reopen schools to how to prevent transmission in high-risk occupational settings—require accurate quantification of the multiple interacting variables that influence airborne infection risk.

Qualitative guidance to reduce the risk of airborne transmission has been published.26–28 Different mathematical models have been proposed to help manage risk of airborne transmission,29,30 and several models have been adapted to COVID-19.31–34 It is important to define quantitative infection risk criteria for different spaces and types of events to more effectively manage the pandemic.35 Such criteria could then be used by authorities and policy makers to assist in deciding which activities are permitted under what conditions, so as to limit infection risk across a society. To our knowledge, no such quantitative criteria have been proposed. In addition, often recommendations are complex and vague, for example, “reduce duration and density of occupancy and increase ventilation.” However, it is not clear how to combine the different measures together (e.g., is half the duration equivalent to doubling the ventilation?), and it is also not clear what level of mitigation is sufficient to reduce outbreak probability to a low level.

Here, we use a box model to estimate the viral aerosol concentration indoors and combine it with the Wells—Riley infection model.29 The combined model is used to derive two quantitative risk parameters that allow comparing the relative risk of transmission in different situations when sharing room air. We explore the trends in infections observed in outbreaks of COVID-19 and other diseases as a function of these parameters. Finally, we use the parameters to quantify a graphical display of the relative risk of different situations and mitigation options.

Materials And Methods

Box Model of Infection

The box model considers a single enclosed space in which virus-containing aerosols are assumed to be rapidly uniformly mixed compared with the time spent by the occupants in the space. This assumption is approximately applicable in many outbreaks, but there are some exceptions such as rooms where clear directional flow causes transmission.18,20 Infection in close proximity (overlapping breathing zones) is not included. The mathematical notation used in the paper is summarized in Table S1. The mass balance equation is first written in terms of c, the concentration of infectious quanta in the air in the enclosed space (units of quanta m−3). Compared with a model written in terms of aerosol or viral particle concentrations, c has the advantage of implicitly including effects such as the deposition efficiency of the aerosol particles in the lungs of a susceptible person, as well as the efficiency with which such deposited particles may cause infection, the multiplicity of infection, and so on. The balance of quanta in the space can be written as:

| (1) |

where Ep is the emission rate of quanta into the indoor air from an infected person present in the space (quanta/h); fe is the penetration efficiency of virus-carrying particles through masks or face coverings for exhalation (which takes into account the impact of whether the infector wears a face covering); V is the volume of the space; λ0 is the first-order rate of removal of quanta by ventilation with outdoor air (h−1); λcle is the removal of quanta by air cleaning devices (e.g., recirculated air with filtering, germicidal UV, portable air cleaners, etc.); λdec is the infectivity decay rate of the virus; λdep is the deposition rate of airborne virus-containing particles onto surfaces, which is in theory size-dependent but not treated in a size-resolved manner in this study. Ep is a critical parameter that depends strongly on the disease, and it can be estimated with a forward model based on aerosol emission rates and pathogen concentration in saliva and respiratory fluid32,36 or by fitting a model such as the one used here to real transmission events.11,32

This equation can be solved analytically or numerically for specific situations. Given the enormous number of possible situations, and given the prevalence of outbreaks resulting from events where air is shared for a significant period of time, we consider a simplified situation where the presence of all occupants is stable and continuous. Writing λ = λ0 + λcle + λdec + λdep for simplicity leads to a steady-state infectious quanta concentration of:

| (2) |

Under the assumption of no infectious quanta at the beginning of the event, a multiplicative factor, rss, can be applied for events too short to approximately reach steady state (see Section S1 for details) to correct the deviation of the quanta concentration averaged over the event (cavg) from that at the steady state:

| (3) |

Because the goal is to analyze outbreaks, we assume that only a single infectious person is present in the space, which is thought to be applicable to the outbreaks analyzed below. This allows calculation of the probability of infection, conditional to one infectious person being present. The model can also be formulated to calculate the absolute probability of infection, if we assume that the probability of an infectious person being present reflects the prevalence of a disease at a given location and time (e.g., refs 31, 37).

The infectious dose inhaled by a susceptible person present in the space (n) is expressed in quanta (one quantum is defined as the infectious dose corresponding to a probability of infection of 1 – 1/e) below:

| (4) |

where fi is the penetration efficiency of virus-carrying particles through masks or face coverings for inhalation (which takes into account the effect of the fraction of occupants wearing face coverings) (see the description of eq 1 for the definition of the other penetration efficiency used in this paper, i.e., fe); B is the breathing volumetric flow rate of susceptible persons; D is the duration of exposure, assumed to be the same for all the susceptible persons. Substituting:

| (5) |

The number of expected secondary infections increases monotonically with increasing n. For an individual susceptible person, by definition of an infectious quantum, the probability of infection is:29

| (6) |

For low values of n, the use of the Taylor expansion for an exponential allows approximating P as:

| (7) |

The total number of secondary infections expected, which may also be regarded as the effective reproduction number (Re) in a given situation, is then:

| (8) |

where Nsus is the number of susceptible individuals present, which is generally lower than the number of occupants because of vaccination or immunity from past infection. All the outbreaks studied here occurred before COVID-19 vaccines became available. Thus, the number of secondary infections increases linearly with n at lower values and nonlinearly at higher values. We retain the simplified form to define and calculate the risk parameters but use eq 6 for fitting the outbreak results in Figure 1b.

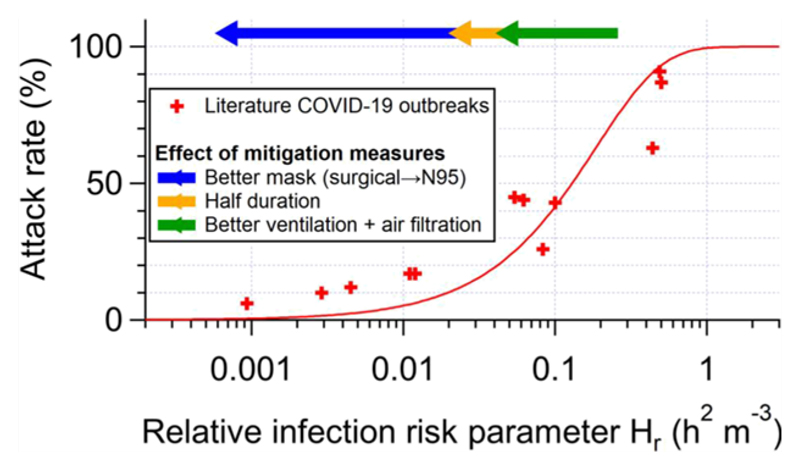

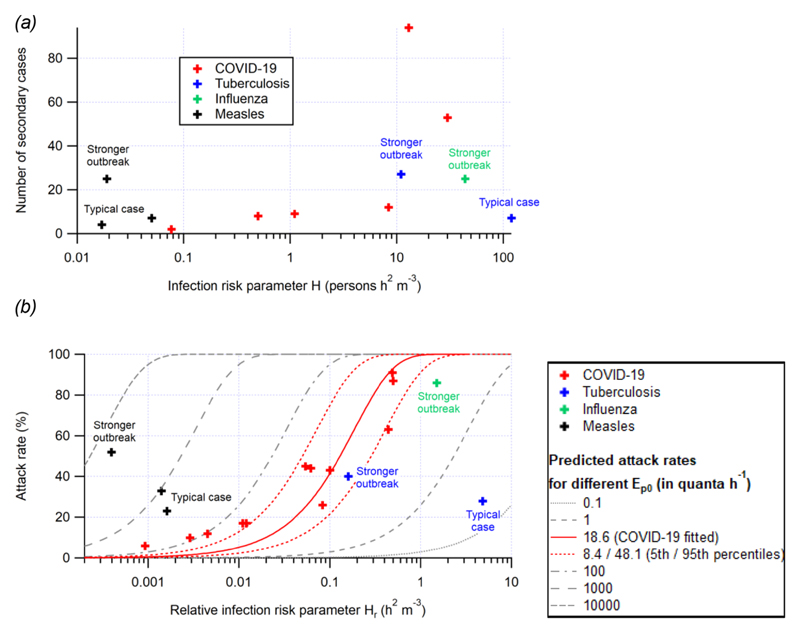

Figure 1.

(a) Number of secondary cases vs. the risk parameter H and (b) attack rate vs. the relative risk parameter Hr for outbreaks of COVID-19, tuberculosis, influenza, and measles reported in the literature. A stronger outbreak in this figure refers to (i) more secondary infections, (ii) a higher attack rate, and (iii) a more infectious index case than typical outbreaks. The fitted trend line of attack rate as a function of Hr and its estimated uncertainty range (5th and 95th percentiles) are also shown in (b). All of the outbreaks investigated here involve the original variants of the virus. A variant twice as contagious (Ep0 × 2) should shift the fitted line to the left by a factor of two and displace the points of individual outbreaks upward.

Risk Parameters for Airborne Infection

We define the relative risk parameter, Hr, and the risk parameter, H, for airborne infection in a shared space. The purpose of Hr and H is to capture the dependency of P and Nsi, respectively, on the parameters that define an event in a given space, in particular those parameters that can be controlled to reduce the risk of shared-room airborne transmission. To better capture the controllable actions, Ep and B were split into factors that can and cannot be controlled. Ep can be expressed as the product Ep0 × rE where Ep0 and rE are, respectively, the quanta shedding rate of an infectious person resting and only orally breathing (no vocalization), which takes into account the amount of virus shedded, the infectivity of each virus shed, and the susceptibility of the person who became infected; and the shedding rate enhancement factor relative to Ep0 for an activity with a certain degree of vocalization and physical intensity (see Table S2a for details). B can be expressed as B0 × rB, where B0 and rB are the average volumetric breathing rate of a sedentary susceptible person (under the assumption of the same size of all age groups) and the relative breathing rate enhancement factor (vs B0) for an activity with a certain physical intensity and for a certain age group (see Table S2b for details). Ep0 is uncertain, likely highly variable across the population, and variable over time during the period of infectiousness.32,36,38 It may also increase due to new virus variants such as the SARS-CoV-2 Delta and Omicron variants, that are more contagious, assuming that the increased contagiousness is due to increased viral emission or reduced infectious dose (both of which would increase the quanta emission rate).39,40 We note that some variants could in principle also increase transmissibility by lengthening the period of infectiousness for a given person, which by itself would not increase the quanta emission rate in a given situation. B0 is relatively well known and varies with a susceptible person's age, sex, and body weight, in addition to the physical activity level. rE and rB are less uncertain than Ep0 and are functions of the specific physical and vocalization activities.32,36,41 Thus, they are useful in capturing the quantitative impact of specific controllable factors. There could be factors beyond those considered here that lead to variation of viral emissions, such as the respiratory effort of patients with breathing disorders, such as emphysema or asthma.42 Such factors can be incorporated into updated tables and computations from the model in the future.

Then P can be expressed as a function of Ep0, B0, and the product of the other controllable factors as:

| (9) |

Where Hr is the relative risk parameter:

| (10) |

It has a unit of h2 m−3, which indicates the increase of risk with duration (h), the inverse of the ventilation rate expressed as air changes per hour (1/h−1 = h), and the inverse of the volume of the space (1/m3). The other parameters such as the effect of masking are dimensionless. Hr includes the relative increase of the emission with activity (rE), but not the quanta emission rate by a resting and orally breathing infector (Ep0). This allows using the same risk parameters for different diseases, which will naturally separate in the graphs according to their transmissibility. The four terms that make up λ may vary in relative importance for different diseases and conditions. λdec ∼ 1.1 h−143 has been reported for COVID-19. λdec depends on temperature and relative humidity.44,45 λdep depends on the particle size and the geometry and airflow in a given space. Respiratory particle sizes in the range from 1 – 5 μ/m are thought to play a role in aerosol transmission of COVID-19, because of a combination of high emission rates by activities such as talking46 and low deposition rates. λdep for a typical furnished indoor space spans 0.2—2h−1 over this size range, with faster deposition for larger particles.47 λ0 varies from ∼12 h−1 for airborne infection isolation rooms,48 ∼6h−1 for laboratories, ∼0.5 h−1 for residences,49 ∼1h−1 for offices,1,5° and ∼2h−1 for classrooms.50,51 Limited ventilation data are available for many semipublic spaces such as shops, restaurants, and bars or transportation. λcle can vary from 0, if such systems are not in use, to several h−1 for adequately sized systems. Ventilation with clean outdoor air will be important in most situations, while virus decay and deposition likely contribute but are more uncertain for COVID-19, based on current information. In particular, the size distribution of aerosols containing infectious viruses is uncertain.

We consider a worst-case scenario where rates of deposition and infectivity decay are small compared with ventilation and air cleaning and can therefore be neglected. This also allows using the same relative risk parameter to compare different airborne diseases. This yields:

| (11) |

Hr can be recast as:

| (12) |

where:

| (13) |

Assuming that all of the people present in a space are susceptible to infection, L is equivalent to the ventilation plus air cleaning rate per person present in the space, (typically expressed in liters s −1 person −1 in standards and guidelines such as from refs 52−54). If some fraction of the people present are immune to the disease, then L is larger than the corresponding personal ventilation rate in the guidance. While this recasting will be useful to persons familiar with ventilation guidelines, we keep the form in eq 11 for most further analyses, because the number of people allowed in a space is one of the critical variables that can be examined with this relative risk parameter.

We insert eq 9 into eq 8 and obtain

| (14) |

where we define the risk parameter

| (15) |

When there is only one infector present and n is small, H is proportional to Nsi, that is, the outbreak size. When it is unknown whether an infector is present, H is an approximate indicator of the absolute probability of infection (Pa), because the expected value of the number of infectors (Ni) is the product of the number of occupants (N) and probability of an occupant being infectious, a measure of prevalence of infectious individuals in local population (ηI), as shown below:

| (16) |

The precise estimation of (ηI) is complex for several reasons. Most transmission may be associated with those infected with high viral loads,55,56 as many infected individuals may not shed virus into the air.38 Also much spread is by individuals with few or no symptoms who may not know that they are infected;57 however, a fraction of symptomatic infectious individuals are typically in isolation. There is also significant variation in viral load and infectivity during the course of the disease.58 For these reasons, it is very difficult to determine ηI precisely based on test data. For a situation with multiple potential infectors present (e.g., a COVID-19 ward in a hospital), the risk parameters should be multiplied by the number of infectors.

For the analysis later in the paper that does not involve the activity type or face covering choice (and thus does not involve rE, rB, fe, or fi), we define another parameter (H'), which is closely related to H′:

| (17) |

This parameter only captures the characteristics of susceptible individuals' presence in the indoor space, not of their behavior.

Results

Value of the Risk Parameters for Documented Outbreaks of COVID-19

An important advantage of the simple risk parameters is that their values can be calculated for outbreaks that are documented in the scientific literature. Values for documented COVID-19 outbreaks are shown in Table 1 (rE and rB are estimated based on the likely types of activities in each case,32,36,41 see Table S2 for typical values). Also included are values for outbreaks documented in the literature for tuberculosis and measles, which are widely accepted to transmit through the air, and an influenza outbreak that was clearly due to airborne transmission. We have included all the outbreaks known to us for which sufficient information was available to estimate airborne infection risk. Most public health investigations so far in this pandemic have neglected to report ventilation rates, the volume of the space, filter and air cleaner efficiencies, and other building science details, and thus, their airborne risk cannot be estimated. It is important that future outbreak reports include this information, to allow expanding our knowledge of the circumstances conducive to airborne transmission of different diseases.

Table 1. Parameters for Outbreaks Documented in the Literature, but Missing Parameters Could Not Be Calculated from the Information Given in the Literature References.

| disease | outbreak (reference) | rE relative shedding rate factor | rB relative breathing rate factor | D (h) | Nsus | V (m3) | λ0 (h–) | L (L s−1 person-1) | rss | H (persons h2 m−3) | H′ (persons h2 m−3) | Hr (h2 m−3) | attack rate (%) | number of secondary cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 | Guangzhou restaurant4 | 9.3a | 1 | 1.2 | 20 | 97 | 0.67 | 0.9 | 0.31 | 1.1 | 0.11 | 0.054 | 45 | 9 |

| big bus outbreak59 | 1 | 1 | 3.3 | 46 | 60 | 4.7 | 1.7 | 0.94 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.011 | 17 | 8 | |

| small bus outbreak59 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 17 | 22 | 8.9 | 3.2 | 0.89 | 0.077 | 0.077 | 0.0045 | 12 | 2 | |

| Skagit choir11 | 85b | 2.5c | 2.5 | 60 | 810 | 0.7 | 2.6 | 0.53 | 30 | 0.14 | 0.5 | 87 | 53 | |

| call center60 | 30d | 1 | 8 | 216 | 630 | 6 | 4.9 | 0.98 | 13 | 0.45 | 0.062 | 44 | 94 | |

| aircraft61 | 50e | 1 | 11 | 19f | 60 | 21 | 18 | 1 | 8.4 | 0.17 | 0.44 | 63 | 12 | |

| slaughterhouse62 | 4.3g | 5h | 8 | 3000 | 0.53 | 0.77 | 0.083 | 26 | ||||||

| Berlin choir63 | 85b | 2.5c | 2.5 | 1200 | 0.17 | 0.19 | 0.49 | 91 | ||||||

| Berlin school 163 | 1 | 1 | 4.5 | 180 | 8.3 | 0.97 | 0.0029 | 10 | ||||||

| Berlin school 2 63 | 1 | 1 | 1.5 | 150 | 10 | 0.93 | 0.00093 | 6 | ||||||

| Israel school 64 | 5.7i | 1.1j | 4.5 | 150 | 2.7 | 0.92 | 0.1 | 43 | ||||||

| Germany | meeting63 | 1.7k | 1 | 2 | 170 | 1.2 | 0.62 | 0.012 | 17 | |||||

| tuberculosis | office65 | 1.7k | 1 | 160 | 67 | 7.1 | 1l | 11 | 6.3 | 0.16 | 40 | 27 | ||

| hospital 66 | 1.9m | 1.7n | 1800 | 25 | 200 | 6 | 13 | 1l | 120 | 37.5 | 4.8 | 28 | 7 | |

| influenza | aircrafte67 | 50 | 1 | 4.3 | 29 | 168 | 0.5 | 0.45 | 0.59 | 44 | 0.88 | 1.5 | 86 | 25 |

| measles | school29 | 1 | 1 | 10 | 48 | 150 (7.6)o | 1l | 0.019 | 0.019 | 0.0004 | 52 | 25 | ||

| school29,p | 1 | 1 | 30 | 31 | 170 (5.5)o | 1l | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.0016 | 23 | 7 | |||

| physician’s office68 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 12 | 250 | 1.2 | 6.9 | 0.42 | 0.017 | 0.017 | 0.0014 | 33 | 4 |

Footnotes: choice of parameters for specific cases. Talking during half of the time and half normal/half loud talking assumed.

Light exercise - loudly speaking

Light intensity for 61- <71 years.

Resting - loudly speaking.

Estimate for coughing. The value is the product of rE for resting - speaking and the ratio of the average expired aerosol counts for coughing and talking.69

Only the business class cabin is considered

Moderate exercise - oral breathing.

Moderate intensity for all age groups.

Standing - speaking for the infectious teacher

Sedentary/passive for students aged 12-18.

Resting - speaking during 1/3 of the time assumed.

Event long enough for the assumption of unity for rss.

Half resting - oral breathing/half light exercise - oral breathing assumed.

Half sedentary/passive/half light intensity assumed.

Ventilation rate per susceptible person. The number in parentheses is for the ventilation rate per occupant, estimated based on a teacher-to-student ratio of 11.3% for Monroe County, NY (according to National Center for Education Statistics Common Core of Data (https://nces.ed.gov/ccd/)).

Scaled to the single-infector condition.

We see that the COVID-19 outbreaks that have been documented span ∼2.5 orders of magnitude range of the risk parameter H ∼ 0.09—30 persons h2 m−3.Numbers of secondary cases of these outbreaks generally increase with H (Figure 1a). Aiming to maintain values far below the threshold of 0.05 persons h2 m 3 should help reduce outbreaks.

Hr correlates well with the attack rates for the outbreaks reported in Table 1 (Figure 1b, Hr can be calculated for more reported outbreaks than H because the number of susceptible occupants is needed for the calculation of H, but not for that of Hr). COVID-19 outbreaks are observed for Hr > 0.001 h2 m−3, and thus, indoor activities should be limited to conditions below this value during the pandemic whenever possible.

A trend line can be fitted to the attack rate vs Hr with the Box/Wells—Riley model based on eq 9 (Figure 1b), with the fitting parameter being Ep0, that is, the basic quanta shedding rate (when breathing only, no vocalization). A best-fit Ep0 of 18.6 quanta h−1 was obtained (with B0 = 0.288 m3 h−1 assumed for all occupants for simplicity). When the uncertainties of Hr and attack rates are considered, the uncertainty of Ep0 can also be estimated through Monte Carlo uncertainty propagation, described in detail in Section S2. The 5th and 95th percentiles of the Ep0 values are 8.4 and 48.1 quanta h−1, respectively. This range is higher than that suggested by Buonanno et al. (2 quanta h −1),32,36 but overlapping with the uncertainty range provided by those authors. Note that outbreaks are typically only observed for individuals with higher quanta emission rates; many infected individuals have low emission rates, and the risk in those situations will be lower than that estimated here.32,36 The attack rates estimated according to this trend line have a high correlation with the actual attack rates (r2 = 0.90; Figure S1). Given the small size of the dataset of Hr and attack rates, we cross-validate this fitting by the leave-one-out method.70 The 12 values of Ep0 obtained in the cross validation have maximum and mean relative absolute deviations of 20 and 6%, respectively, from the best-fitvalue, showing the robustness of the fitting.

Close alignment supports the dominant shared-room airborne character of these COVID-19 outbreaks. If the outbreaks had major components of other transmission modes (e.g., fomite or close-range transmission), we would expect a dependence on other parameters not considered here and overall much lower correlation with the risk parameters. Nevertheless, it can be observed that the attack rates of the outbreaks at low Hr (∼0.01 h2 m−3 or lower) are higher than the fitted curve. This can be due to several factors, including (i) other transmission routes (e.g., short-range airborne transmission, for which the risk cannot be well captured by the model in this study and can still be significant at low Hr)or (ii) the detection of only outlier cases of long-range airborne transmission resulting from the variability of Ep0 (e.g., cases where the infector's actual quanta emission rate was extremely high), as the other cases may have too few secondary infections to be documented in the literature.

Effect of Building Parameters vs. Human Activities

The type of activity performed in each case (captured by the product of rE and rB) contributes substantially to the difference in H between these cases. When human activities are not taken into account, the parameter H only spans a narrow range of 0.09–0.56 person h2 m 3. This is probably due to similar per-person ventilation rates in many public indoor spaces (on the order of a few liter s−1 person−1)52 and similar lengths of common events (in hours).

Similar to H, the variation in the values of Hr for the outbreaks in Table 1 is also largely determined by rE and rB.If they are not taken into account, Hr for all outbreaks would vary in the narrow range of 0.001 to ∼0.01 h2 m−3, as V and À0 are building characteristics and D, as discussed above, is usually in hours. This implies that, in the presence of a single infector, reducing vocalization and.or physical intensity levels of the indoor activity is a very effective way to lower the infection risk of susceptible individuals. Reducing the event length can also help, while reducing occupancy cannot in this case, as shown by eq 10.

It is possible that some of the most visible outbreaks are associated with super-emitter individuals, who shed virus particles at higher rates than others.42,71−73 If that is the case, the actual Hr values at which significant transmission starts to appear in the presence of individuals that are not super emitters may be higher than those determined here. However, if super-emitters are important, so will be their contribution to total spread, and thus one should try to reduce the risk to reduce the probability of such events occurring.

Values of the Risk Parameters for Outbreaks of Other Airborne Diseases

In Table 1 and Figure 1, we also include a few reported indoor outbreaks of three other diseases with significant airborne transmission, that is, tuberculosis, influenza, and measles. For outbreaks to have a similar number of secondary cases or attack rate, H or Hr needs to be higher for tuberculosis and influenza and lower for measles than that for COVID-19 (Figure 1). Note that many of the children present in the measles outbreak were vaccinated, but the risk parameter framework can still be applied by considering the number of susceptible children present. This difference is mainly due to differences in Ep0 (lower for tuberculosis and influenza and higher for measles; Figure 1b). A higher Ep0 for measles may indicate a larger amount of airborne measles virus in breath or a steeper dose response curve for the measles virus than SARS-CoV-2, or both. A novel disease as contagious as measles would make almost any indoor situation prone to superspreading. On the other hand, tuberculosis and influenza are less contagious. Tuberculosis transmission is propagated because untreated infected people remain contagious for years.74 The influenza outbreak occurred in an airplane without ventilation with the index case constantly coughing and represents an extreme for this disease.67 Most influenza patients are thought to emit significantly less virus.75 More discussions about quanta emission rates of different diseases can be found elsewhere.36,76

Given that both the measles and tuberculosis pathogens are widely accepted as airborne, the intermediate risk profile for COVID-19 in Figure 1b is not inconsistent with airborne transmission, contrary to frequently made arguments.77,78 Contagiousness of a disease does not necessarily indicate the transmission route.79 Airborne diseases can vary in their contagiousness depending on parameters such as the amount of virus shed, the survival of the virus in the air, the dose—response relationship for infection, and other parameters. The only fundamental requirement is that transmission needs to be sufficient for the disease to survive as such, something COVID-19 has had no trouble with so far.

Graphical Representation of Relative Risks of Different Situations

When it is not known whether infectors are present at an indoor event, all occupants must be considered possible infectors. We assume that the probability of an occupant being infectious is the same as the fraction of infectious people in the local population H indicates the risk of an outbreak. Consequently, the risk also depends on the number of occupants in addition to the vocalization level, event duration, ventilation, and mask wearing. Jones et al.26 estimated the dependency of the infection risk on these factors and tabulated it in a manner similar to Table 2. However, they only did so qualitatively. Having defined H as a risk parameter, we can assess the risk more quantitatively based on H values (as well as contact times allowed until outbreak risk is significant (H = 0.05 persons h2 m−3) and attack rates) under different conditions (Table 2). Although the actual risk also depends on ηI and the choice of the threshold for high risk (red cells in Table 2) is subjective, the risk parameter (H value) in Table 2 seems to vary in a smaller range than the corresponding table in the study by Jones et al.26 We also show that being outdoors (with much better ventilation than indoors) has a greater expected benefit than they estimated.

Table 2. (a) Values of the Airborne Infection Risk Parameter (H, in Persons h2 m−3), (b) Exposure Times Corresponding to H = 0.05 Persons h2 m−3, and (c) Predicted Attack Rates with 0.1% Infectious People in Local Population for (Equivalent) Shared-Room Airborne Transmission under Different Conditions in the Similar Format of Figure 3 of ref 25.a.

| Low occupancy | High occupancy | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type and level of group activity | Outdoor and well ventilated | Indoor and well ventilated | Poorly ventilated | Outdoor and well ventilated | Indoor and well ventilated | Poorly ventilated |

| Wear face coverings, contact for short time | ||||||

| Silent | 2.3E-05 | 1.9E-03 | 1.2E-02 | 8.2E-05 | 6.8E-03 | 4.1E-02 |

| Speaking | 1.2E-04 | 9.7E-03 | 5.8E-05 | 4.1E-04 | 3.4E-02 | 2.0E-01 |

| Shouting, singing | 7.0E-04 | 5.8E-02 | 3.5E-01 | 2.5E-03 | 2.0E-01 | 1.2E+00 |

| Heavy exercise | 1.6E-03 | 1.4E-01 | 8.2E-01 | 5.7E-03 | 4.8E-01 | 2.9E+00 |

| Wear face coverings, contact for prolonged time | ||||||

| Silent | 2.3E-04 | 1.9E-02 | 1.2E-01 | 8.2E-04 | 6.8E-02 | 4.1E-01 |

| Speaking | 1.2E-03 | 9.7E-02 | 5.8E-01 | 4.1E-03 | 3.4E-01 | 2.0E+00 |

| Shoutins, Singig | 7.0E-03 | 5.8E-01 | 3.5E-03 | 2.5E-02 | 2.0E+00 | 1.2E+01 |

| Heavy Excercise | 1.6E-03 | 1.4E-00 | 8.2E+00 | 5.7E-02 | 4.8E+00 | 2.9E+00 |

| No face coverings, contact for short time | ||||||

| Silent | 6.7E-05 | 5.6E-03 | 3.3E-02 | 2.3E-04 | 1.9E-02 | 1.2E-01 |

| Speaking | 3.3E-04 | 2.8E-02 | 1.7E-01 | 1.2E-03 | 9.7E-02 | 5.8E-01 |

| Shoutins, Singig | 2.0E-03 | 1.7E-01 | 1.0E-01 | 7.0E-03 | 5.8E-01 | 3.5E+00 |

| Heavy Excercise | 4.7E-03 | 3.9E-01 | 2.3E+00 | 1.6E-02 | 1.4E+00 | 8.2E+00 |

| No face coverings, contact for prolonged time | ||||||

| Silent | 6.7E-04 | 5.6E-03 | 3.3E-02 | 2.3E-04 | 1.9E-02 | 1.2E-01 |

| Speaking | 3.3E-03 | 2.8E-01 | 1.2E+00 | 1.2E-02 | 9.7E-01 | 5.8E+00 |

| Shoutins, Singig | 2.0E-02 | 1.7E+00 | 1.0E+01 | 7.0E-02 | 5.8E+00 | 3.5E+01 |

| Heavy Excercise | 4.7E-03 | 3.9E-01 | 2.3E+01 | 1.6E-01 | 1.4E+01 | 8.2E+01 |

| Low occupancy | High occupancy | |||||

| Type and level of group activity | Outdoor and well ventilated | Indoor and well ventilated | Poorly ventilated | Outdoor and well ventilated | Indoor and well ventilated | Poorly ventilated |

| Wear face coverings | ||||||

| Silent | 2100 | 26 | 4.3 | 610 | 7.3 | 1.22 |

| Speaking | 430 | 5.1 | 0.86 | 120 | 1.5 | 0.24 |

| Shouting, singing | 71 | 0.86 | 0.14 | 20 | 0.24 | <0.050 |

| Heavy exercise | 31 | 0.37 | 0.061 | 8.7 | 0.10 | <0.050 |

| No face coverings | ||||||

| Silent | 750 | 9.0 | 1.5 | 210 | 2.6 | 0.43 |

| Speaking | 150 | 1.8 | 0.30 | 43 | 0.51 | 0.086 |

| Shouting, singing | 25 | 0.30 | 0.050 | 7.1 | 0.086 | <0.050 |

| Heavy exercise | 11 | 0.13 | <0.050 | 3.1 | <0.050 | <0.050 |

| Low occupancy | High occupancy | |||||

| Type and level of group activity | Outdoor and well ventilated | Indoor and well ventilated | Poorly ventilated | Outdoor and well ventilated | Indoor and well ventilated | Poorly ventilated |

| Wear face coverings, contact for short time | ||||||

| Silent | <0.001% | 0.001% | 0.006% | <0.001% | 0.004% | 0.022% |

| Speaking | <0.001% | 0.005% | 0.031% | <0.001% | 0.018% | 0.11% |

| Shouting, singing | <0.001% | 0.031% | 0.19% | 0.001% | 0.018% | 0.11% |

| Heavy exercise | <0.001% | 0.07% | 0.44% | 0.003% | 0.25% | 1.5% |

| Wear face coverings, contact for prolonged time | ||||||

| Silent | <0.001% | 0.010% | 0.06% | <0.001% | 0.036% | 0.22% |

| Speaking | 0.001% | 0.05% | 0.31% | 0.002% | 0.18% | 1.1% |

| Shoutins, Singig | 0.004% | 0.031% | 1.9% | 0.013% | 1.1% | 6.4% |

| Heavy Excercise | 0.009% | 0.73% | 4.3% | 0.031% | 2.5% | 14% |

| No face coverings, contact for short time | ||||||

| Silent | <0.001% | 0.003% | 0.018% | <0.001% | 0.010% | 0.06% |

| Speaking | <0.001% | 0.015% | 0.09% | 0.001% | 0.05% | 0.31% |

| Shoutins, Singig | 0.001% | 0.09% | 0.53% | 0.004% | 0.31% | 1.9% |

| Heavy Excercise | 0.002% | 0.21% | 1.2% | 0.009% | 0.73% | 4.3% |

| No face coverings, contact for prolonged time | ||||||

| Silent | <0.001% | 0.030% | 0.018% | 0.001% | 0.010% | 0.62% |

| Speaking | 0.002% | 0.15% | 0.89% | 0.006% | 0.52% | 3.1% |

| Shoutins, Singig | 0.011% | 0.89% | 5.2% | 0.037% | 3.1% | 17% |

| Heavy Excercise | 0.025% | 2.1% | 12% | 0.09% | 7.0% | 35% |

S3 details the specific choices of the conditions in Table 2. Note that these specifications can be changed as needed, which is easy to implement in the COVID-19 Aerosol Transmission Estimator (Figure S2). Color of a cell varies (a) with H value from green (0 persons h2 m–3) via yellow (0.05 persons h2 m–3) to red (.0.5 persons h2 m–3), (b) with exposure time from red (0.1 h) via yellow (1 h) to green (10 h), and (c) with predicted attack rate from green (0) via yellow (0.0001) to red (0.001). The selection of the colors in Table 2a was based on the following considerations: (i) no risk (H = 0 persons h2 m–3) for green; (ii) no documented outbreaks when H < 0.05 persons h2 m–3 (Figure 1a) (thus 0.05 persons h2 m–3 for yellow); (iii) outbreaks with significant numbers of secondary infections when H. 0.5 persons h2 m–3 (Figure 1a) (thus red). For that in Table 2b, relatively simple numbers are chosen for the thresholds that correspond to the thresholds for H in Table 2a. As probability of infection is given in Table 2c, its colors are chosen based on the personal risk tolerance of the authors. Note that significant uncertainties remain in the parameters for the table (which are for the wild-type SARS-CoV-2) and that the colors should be interpreted in relative terms. These tables are available in the online transmission risk estimator, and all of their aspects can be modified depending on specific situations and preferences.

Note that, although occupancy has no impact on the attack rate if an infector is present, occupancy affects the risk in two ways when the presence of infector(s) is unknown, that is, (i) the probability of the presence of an infector in a certain locality and (ii) the size (number of secondary cases) of the outbreak if it occurs. Therefore, lowering occupancy has double benefits.

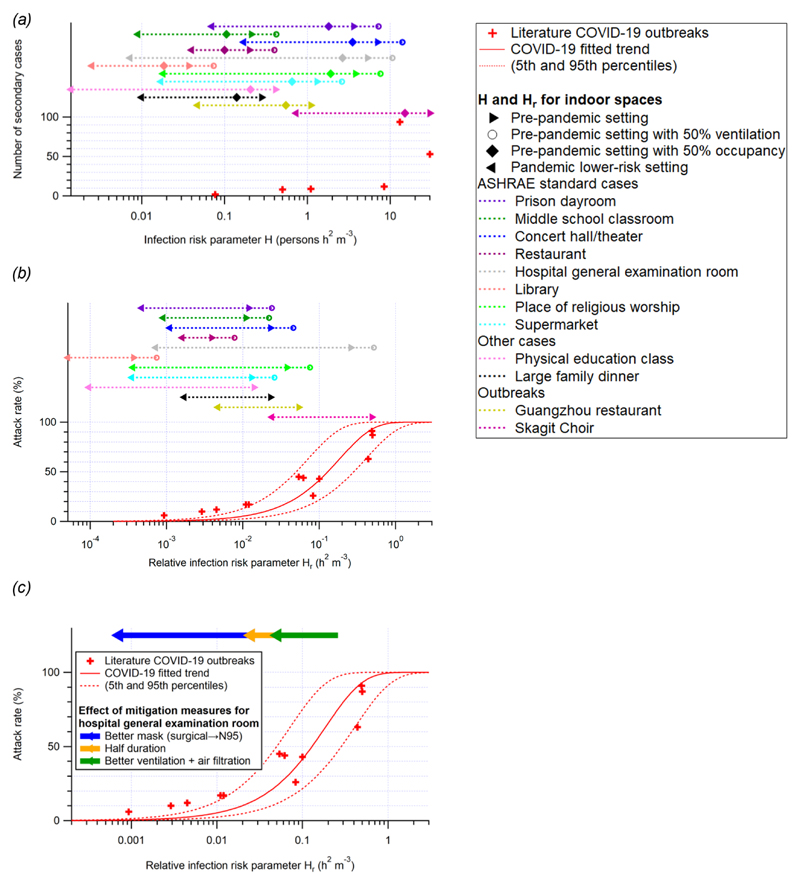

Risk Evaluation for Indoor Spaces with Prepandemic and Mitigation Scenarios

Values of the risk parameter H for some typical public spaces under prepandemic conditions are tabulated in Table S4 and shown in Figure 2. H in all prepandemic settings is on the order of 0.05 persons h2 m −3 or higher, implying a significant risk of outbreak during the pandemic (Figure 2a). Often, ventilation rates may be lower than official guidance due to many factors including malfunction, lack of maintenance, or attempts to save energy.80 Substandard ventilation, coupled with poor air distribution, substantially increases the risk and size of an outbreak through shared-room airborne transmission (Figure 2a,b). This is consistent with observations that indicate that COVID-19 outbreaks are disproportionately observed in poorly ventilated environments, which are specifically spaces with little to no added outdoor air or adequately filtered air.81 However, H and Hr of all of the prepandemic spaces are in a regime highly sensitive to mitigation efforts (Figure 2a,b). Therefore, mitigation measures such as increasing ventilation or air cleaning, reducing voice volume when speaking, reducing occupancy, shortening duration of occupancy, and mask wearing are required to reduce the risk of transmission in similar settings (Table S4). With mitigation measures implemented, H in these settings can be lowered to the order of 0.01 persons h2 m −3, low enough to avoid major outbreaks (Figure 2a). Particularly, for hospital general examination room, a high-risk setting where there can be coughing infectors emitting quanta at a high rate, a combination of an improvement of ventilation rate to 6 h −1, application of higher efficiency air filters, a halved duration, and a requirement of fit-tested N95 respirators can lower the attack rate from ∼90% to negligible (Figure 2c). Use of high-quality masks (e.g., N95/FFP3) that fit well is highly effective as a mitigation measure.

Figure 2.

(a and b) Same format as Figure 1, but for COVID-19 only. Also shown are the H and Hr values for several common indoor situations (both prepandemic and pandemic) listed in Table S4. The H values for the cases with prepandemic settings except for a lower occupancy and the H and Hr values for the ASHRAE standard cases52 (not other cases or outbreaks) with prepandemic settings except for a lower ventilation rate are shown for comparison. The standalone legend box is for (a) and (b) only. (c) Approximately multiplicative effects of various mitigation measures for the hospital general examination room case are also shown as an example.

Calculation of Risk Parameters for Specific Situations

The calculation of H, H′, and Hr for specific situations of interest has been implemented in the COVID-19 aerosol transmission estimator, which is freely available online.31 The estimator is a series of spreadsheets that implement the same aerosol transmission model described by Miller et al.11 It allows the user to make a copy into an online Google spreadsheet or download it as a Microsoft Excel file for adaptation to the situations of interest to each user. The model can be used to estimate the risk of specific situations, to explore the reduction in transmission because of different control measures (e.g., increased ventilation, masking, etc.), and to understand aerosol transmission modeling for incorporation into more complex models. The model also allows the estimation of the average CO2 concentration during an activity, as an additional indicator of indoor risk, and to facilitate the investigation ofthe relationship between infection risk and CO2 concentrations.37,82 A screenshot ofthe estimator is shown in Figure S2.

In addition, a sheet allows recalculating Table 2 in this paper for sets of parameters different from those used here (and shown in Table S2).

Discussion

We have explored the relationship between airborne infection transmission when sharing indoor spaces with distance between occupants greater than their breathing zones and the parameters of the space using a box/Wells—Riley model. We have derived an expression for the number of secondary infections and isolated the controllable terms in this expression in two airborne transmission risk parameters, H and Hr.

We find a consistent relationship, with increasing attack rate in the known COVID-19 outbreaks, as the value of Hr increases. This provides some confidence that airborne transmission is important in these outbreaks and that the models used here capture the key processes important for airborne transmission.

Outbreaks have been observed when Hr is on the order of 0.001 h2 m −3 and higher. A criterion based on Hr (e.g., Hr > 0.01 or 0.1 h2 m−3, depending on available contact tracing resources) can also be used to determine if an occupant of an indoor space is a “close contact” of an identified infector in the same space through the shared-room air airborne transmission (note that this criterion does not apply to close contacts at risk of infection through short-range (<2 m) airborne transmission). The lowest H for the major COVID-19 outbreaks in indoor settings reported in the literature is ∼0.1 person h2 m−3. Note that all the outbreaks investigated here concern the early to mid-2020 variants of SARS-CoV-2, and a variant twice as contagious as those should reduce the tolerable values of the parameters by about a factor of 2. H can be orders of magnitude higher for the superspreading events where most attendees were infected (e.g., the Skagit Valley choir rehearsal).11 However, if human activity-dependent factors are not taken into account, H for all the outbreaks discussed in this paper is ∼0.1 − 0.5 person h2 m−3. H′ values for public indoor spaces usually fall in or near this range primarily due to similar per-person ventilation rates and public event durations. Substandard ventilation, coupled with poor air distribution, is associated with substantial increases in the risk of outbreak. However, all of the prepandemic example spaces analyzed are in a regime in which they are highly sensitive to mitigation efforts.

The relative risk of COVID-19 infection falls between that of two well-known airborne diseases: the more transmissible measles and the less transmissible tuberculosis. This shows that the fact that COVID-19 is less transmissible than measles does not rule out airborne transmission. These risk parameters can be applied to other airborne diseases, if outbreaks are characterized in this framework. This approach may be useful in the design and renovation of building systems. For a novel disease that was as transmissible as measles, it would be very difficult to make any indoor activities safe aside from highly effective/protective vaccination.

Our analysis shows that mitigation measures to limit shared-room airborne transmission are needed in most indoor spaces whenever COVID-19 is spreading in a community. Among effective measures are reducing vocalization, avoiding intense physical activities, shortening the duration of occupancy, reducing the number of occupants, wearing high-quality well-fitting masks, increasing ventilation, improving ventilation effectiveness, and applying additional virus removal measures (such as HEPA filtration and UVGI disinfection). The use of multiple “layers of protection” is needed in many situations, while a single measure (e.g., masking) may not be able to reduce risk to low levels. We have shown that combinations of some or all of these measures are able to lower H close to 0.01 person h2 m 3, so that the expected number of secondary cases is substantially lower than 1 even in the presence of an infectious person, hence would be likely to avoid major outbreaks.

Supplementary Material

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.est.1c06531.

Derivation of the factor accounting for the deviation from the steady state, details of Monte Carlo uncertainty propagation for the fitting of attack rates vs Hr, evaluation of the fitting in Figure 1b, rE and rB for different vocalization and physical intensity levels, details of the conditions for Table 2, details of the setting in Figure 2, and screenshot of the COVID-19 Aerosol Transmission Estimator (PDF)

Acknowledgments

Z.P. and J.L.J. were partially supported by NSF AGS-1822664. T.G. was supported by ESRC ES/V010069/1. L.B. acknowledges CIHR and Fields, and NSF.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

This paper has been previously submitted to medRxiv, a preprint server for Health Sciences. The preprint can be cited as: Z.P., A.L.P.R., E.K., W.B., G.B., S.J.D., J.K., Y.L., M.G.L.C.L., L.C.M., L.M., W.N., C.N., X.Q., C.S., R.T., T.G., L.B., A.B., J.W.T., S.L.M., J.L.J. Practical Indicators for Risk of Airborne Transmission in Shared Indoor Environments and their Application to COVID-19 Outbreaks. 2021, medRxiv. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.04.21.21255898 (accessed November 22, 2021).

Contributor Information

Z. Peng, Dept. of Chemistry and CIRES, University of Colorado, Boulder, Colorado 80309, United States

A.L. Pineda Rojas, CIMA, UMI-IFAECI/CNRS, FCEyN, Universidad de Buenos Aires—YUBA/CONICET, Buenos Aires C1428EGA, Argentina

E. Kropff, Leloir Institute—IIBBA/CONICET, CBA, Buenos Aires C1405BWE, Argentina

W. Bahnfleth, Dept. of Architectural Engineering, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, Pennsylvania 16802, United States

G. Buonanno, Dept. of Civil and Mechanical Engineering, University of Cassino and Southern Lazio, Cassino 03043, Italy

S.J. Dancer, Dept. of Microbiology, NHS Lanarkshire, Glasgow, Scotland G75 8RG, U.K.; School of Applied Sciences, Edinburgh Napier University, Edinburgh, Scotland EH11 4BN, U.K

J. Kurnitski, REHVA Technology and Research Committee, Tallinn University of Technology, Tallinn 19086, Estonia

Y. Li, Dept. of Mechanical Engineering, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong 999077, China

M.G.L.C. Loomans, Dept. of the Built Environment, Eindhoven University of Technology, Eindhoven 5612 AZ, The Netherlands

L.C. Marr, Dept. of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, Virginia 24061, United States

L. Morawska, International Laboratory for Air Quality and Health, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Queensland 4001, Australia

W. Nazaroff, Dept. of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of California, Berkeley, California 94720, United States

C. Noakes, School of Civil Engineering, University of Leeds, Leeds LS2 9JT, U.K

X. Querol, Institute of Environmental Assessment and Water Research, IDAEA, Spanish Research Council, CSIC, Barcelona 08034, Spain

C. Sekhar, Dept. of the Built Environment, National University of Singapore, 117566, Singapore

R. Tellier, Dept. of Medicine, McGill University and McGill University Health Centre, Montreal, Québec H4A 3J1, Canada

T. Greenhalgh, Nuffield Dept. of Primary Care Health Sciences, University of Oxford, Oxford OX2 6GG, U.K

L. Bourouiba, The Fluid Dynamics of Disease Transmission Laboratory, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139, United States

A. Boerstra, REHVA (Federation of European Heating, Ventilation and Air Conditioning Associations), BBA Binnenmilieu, The Hague 2501 CJ, The Netherlands

J.W. Tang, Dept. of Respiratory Sciences, University of Leicester, Leicester LE1 7RH, U.K

S.L. Miller, Dept. of Mechanical Engineering, University of Colorado, Boulder, Colorado 80309, United States

References

- (1).Nazaroff WW. Indoor Bioaerosol Dynamics. Indoor Air. 2016;26:61–78. doi: 10.1111/ina.12174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Morawska L, Cao J. Airborne Transmission of SARS-CoV-2: The World Should Face the Reality. Environ Int. 2020;139:105730. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.105730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Tellier R. Review of Aerosol Transmission of Influenza A Virus. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:1657–1662. doi: 10.3201/eid1211.060426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Li Y, Qian H, Hang J, Chen X, Cheng P, Ling H, Wang S, Liang P, Li J, Xiao S, Wei J, et al. Probable Airborne Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in a Poorly Ventilated Restaurant. Build Environ. 2021;196:107788. doi: 10.1016/j.buildenv.2021.107788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Public Health England. Varicella. The Green Book; London, UK: 2015. Chapter 34: Immunisation against Infectious Disease; pp. 421–442. [Google Scholar]

- (6).Tellier R, Li Y, Cowling BJ, Tang JW. Recognition of Aerosol Transmission of Infectious Agents: A Commentary. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19:101. doi: 10.1186/s12879-019-3707-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Morawska L, Milton DK. It Is Time to Address Airborne Transmission of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:2311–2313. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Lednicky JA, Lauzardo M, Fan ZH, Jutla A, Tilly TB, Gangwar M, Usmani M, Shankar SN, Mohamed K, Eiguren-Fernandez A, Stephenson CJ, et al. Viable SARS-CoV-2 in the Air of a Hospital Room with COVID-19 Patients. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;100:476–482. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).National Academies of Sciences, Engineering; Medicine; Others. Airborne Transmission of SARS-CoV-2: Proceedings of a Workshop in Brief. The National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Prather KA, Marr LC, Schooley RT, McDiarmid MA, Wilson ME, Milton DK. Airborne Transmission of SARS-CoV-2. Science. 2020;370:303–304. doi: 10.1126/science.abf0521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Miller SL, Nazaroff WW, Jimenez JL, Boerstra A, Buonanno G, Dancer SJ, Kurnitski J, Marr LC, Morawska L, Noakes C. Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 by Inhalation of Respiratory Aerosol in the Skagit Valley Chorale Superspreading Event. Indoor Air. 2021;31:314–323. doi: 10.1111/ina.12751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Greenhalgh T, Jimenez JL, Prather KA, Tufekci Z, Fisman D, Schooley R. Ten Scientific Reasons in Support of Airborne Transmission of SARS-CoV-2. Lancet. 2021;397:1603–1605. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00869-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Tang JW, Marr LC, Li Y, Dancer SJ. Covid-19 Has Redefined Airborne Transmission. BMJ. 2021;373:n913. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Gelfand HM, Posch J. The Recent Outbreak of Smallpox in Meschede, West Germany. Am J Epidemiol. 1971;93:234–237. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a121251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Yu ITS, Li Y, Wong TW, Tam W, Chan AT, Lee JHW, Leung DYC, Ho T. Evidence of Airborne Transmission of the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Virus. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1731–1739. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Dick EC, Jennings LC, Mink KA, Wartgow CD, Inborn SL. Aerosol Transmission of Rhinovirus Colds. J Infect Dis. 1987;156:442–448. doi: 10.1093/infdis/156.3.442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Chen W, Zhang N, Wei J, Yen H-L, Li Y. Short-Range Airborne Route Dominates Exposure of Respiratory Infection during Close Contact. Build Environ. 2020;176:106859. doi: 10.1016/j.buildenv.2022.109166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Katelaris AL, Wells J, Clark P, Norton S, Rockett R, Arnott A, Sintchenko V, Corbett S, Bag SK. Epidemiologic Evidence for Airborne Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 during Church Singing, Australia, 2020. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021;27:1677–1680. doi: 10.3201/eid2706.210465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Shen Y, Li C, Dong H, Wang Z, Martinez L, Sun Z, Handel A, Chen Z, Chen E, Ebell MH, Wang F, et al. Community Outbreak Investigation of SARS-CoV-2 Transmission Among Bus Riders in Eastern China. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180:1665–1671. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.5225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Kwon KS, Park JI, Park YJ, Jung DM, Ryu KW, Lee JH. Evidence of Long-Distance Droplet Transmission of SARSCoV-2 by Direct Air Flow in a Restaurant in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2020;35:e415. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Jang S, Han SH, Rhee JY. Cluster of Coronavirus Disease Associated with Fitness Dance Classes, South Korea. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26:1917–1920. doi: 10.3201/eid2608.200633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Eichler N, Thornley C, Swadi T, Devine T, McElnay C, Sherwood J, Brunton C, Williamson F, Freeman J, Berger S, Ren X, et al. Transmission of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 during Border Quarantine and Air Travel, New Zealand (Aotearoa) Emerg Infect Dis. 2021;27:1274–1278. doi: 10.3201/eid2705.210514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Nissen K, Krambrich J, Akaberi D, Hoffman T, Ling J, Lundkvist A, Svensson L, Salaneck E. Long-Distance Airborne Dispersal of SARS-CoV-2 in COVID-19 Wards. Sci Rep. 2020;10:19589. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-76442-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Hwang SE, Chang JH, Oh B, Heo J. Possible Aerosol Transmission of COVID-19 Associated with an Outbreak in an Apartment in Seoul, South Korea, 2020. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;104:73–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.12.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Li Y, Leung GM, Tang JW, Yang X, Chao CYH, Lin JZ, Lu JW, Nielsen PV, Niu J, Qian H, Sleigh AC, et al. Role of Ventilation in Airborne Transmission of Infectious Agents in the Built Environment - a Multidisciplinary Systematic Review. Indoor Air. 2007;17:2–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0668.2006.00445.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Jones NR, Qureshi ZU, Temple RJ, Larwood JPJ, Greenhalgh T, Bourouiba L. Two Metres or One: What Is the Evidence for Physical Distancing in Covid-19? BMJ. 2020;370:m3223. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Morawska L, Tang JW, Bahnfleth W, Bluyssen PM, Boerstra A, Buonanno G, Cao J, Dancer S, Floto A, Franchimon F, Haworth C, et al. How Can Airborne Transmission of COVID-19 Indoors Be Minimised? Environ Int. 2020;142:105832. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.105832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Bond TC, Bosco-Lauth A, Farmer DK, Francisco PW, Pierce JR, Fedak KM, Ham JM, Jathar SH, VandeWoude S. Quantifying Proximity, Confinement, and Interventions in Disease Outbreaks: A Decision Support Framework for Air-Transported Pathogens. Environ Sci Technol. 2021;55:2890–2898. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.0c07721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Riley EC, Murphy G, Riley RL. Airborne Spread of Measles in a Suburban Elementary School. Am J Epidemiol. 1978;107:421–432. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Noakes CJ, Sleigh PA. Mathematical Models for Assessing the Role of Airflow on the Risk of Airborne Infection in Hospital Wards. J R Soc Interface. 2009;6(Suppl 6):S791. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2009.0305.focus. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Jimenez JL, Peng Z. COVID-19 Aerosol Transmission Estimator. [accessed Mar 26, 2021]. https://tinyurl.com/covid-estimator .

- (32).Buonanno G, Morawska L, Stabile L. Quantitative Assessment of the Risk of Airborne Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 Infection: Prospective and Retrospective Applications. Environ Int. 2020;145:106112. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.106112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Lelieveld J, Helleis F, Borrmann S, Cheng Y, Drewnick F, Haug G, Klimach T, Sciare J, Su H, Pöschl U. Model Calculations of Aerosol Transmission and Infection Risk of COVID-19 in Indoor Environments. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:8114. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17218114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Jones B, Sharpe P, Iddon C, Hathway EA, Noakes CJ, Fitzgerald S. Modelling Uncertainty in the Relative Risk of Exposure to the SARS-CoV-2 Virus by Airborne Aerosol Transmission in Well Mixed Indoor Air. Build Environ. 2021;191:107617. doi: 10.1016/j.buildenv.2021.107617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Han E, Tan MMJ, Turk E, Sridhar D, Leung GM, Shibuya K, Asgari N, Oh J, Garcia-Basteiro AL, Hanefeld J, Cook AR, et al. Lessons Learnt from Easing COVID-19 Restrictions: An Analysis of Countries and Regions in Asia Pacific and Europe. Lancet. 2020;396:1525–1534. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32007-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Buonanno G, Stabile L, Morawska L. Estimation of Airborne Viral Emission: Quanta Emission Rate of SARS-CoV-2 for Infection Risk Assessment. Environ Int. 2020;141:105794. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.105794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Peng Z, Jimenez JL. Exhaled CO2 as a COVID-19 Infection Risk Proxy for Different Indoor Environments and Activities. Environ Sci Technol Lett. 2021;8:392–397. doi: 10.1021/acs.estlett.1c00183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Ma J, Qi X, Chen H, Li X, Zhang Z, Wang H, Sun L, Zhang L, Guo J, Morawska L, Grinshpun SA, et al. COVID-19 Patients in Earlier Stages Exhaled Millions of SARS-CoV-2 per Hour. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;72:e652–e654. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Volz E, Mishra S, Chand M, Barrett JC, Johnson R, Geidelberg L, Hinsley WR, Laydon DJ, Dabrera G, O’Toole A, et al. Assessing Transmissibility of SARS-CoV-2 Lineage B.1.1.7 in England. Nature. 2021;593:266–269. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03470-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Kidd M, Richter A, Best A, Cumley N, Mirza J, Percival B, Mayhew M, Megram O, Ashford F, White T, Moles-Garcia E, et al. S-Variant SARS-CoV-2 Lineage B1.1.7 Is Associated with Significantly Higher Viral Loads in Samples Tested by Thermo Fisher Taq Path RT-qPCR. J Infect Dis. 2021;223:1666. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiab082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).EPA. Exposure Factors Handbook. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency; 2011. Chapter 6—YInhalation Rates. [Google Scholar]

- (42).Edwards DA, Ausiello D, Salzman J, Devlin T, Langer R, Beddingfield BJ, Fears AC, Doyle-Meyers LA, Redmann RK, Killeen SZ, Maness NJ, et al. Exhaled Aerosol Increases with COVID-19 Infection, Age, and Obesity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118:e2021830118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2021830118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).van Doremalen N, Bushmaker T, Morris DH, Holbrook MG, Gamble A, Williamson BN, Tamin A, Harcourt JL, Thornburg NJ, Gerber SI, Lloyd-Smith JO, et al. Aerosol and Surface Stability of SARS-CoV-2 as Compared with SARS-CoV-1. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1564–1567. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2004973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Chan KH, Peiris JSM, Lam SY, Poon LLM, Yuen KY, Seto WH. The Effects of Temperature and Relative Humidity on the Viability of the SARS Coronavirus. Adv Virol. 2011;2011:734690. doi: 10.1155/2011/734690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Dabisch P, Schuit M, Herzog A, Beck K, Wood S, Krause M, Miller D, Weaver W, Freeburger D, Hooper I, Green B, et al. The Influence of Temperature, Humidity, and Simulated Sunlight on the Infectivity of SARS-CoV-2 in Aerosols. Aerosol Sci Technol. 2021;55:142–153. doi: 10.1080/02786826.2020.1829536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Johnson GR, Morawska L, Ristovski ZD, Hargreaves M, Mengersen K, Chao CYH, Wan MP, Li Y, Xie X, Katoshevski D, Corbett S, et al. Modality of Human Expired Aerosol Size Distributions. J Aerosol Sci. 2011;42:839–851. doi: 10.1016/j.jaerosci.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Thatcher TL, Lai ACK, Moreno-Jackson R, Sextro RG, Nazaroff WW. Effects of Room Furnishings and Air Speed on Particle Deposition Rates Indoors. Atmos Environ. 2002;36:1811–1819. [Google Scholar]

- (48).Ninomura P, Bartley J. New Ventilation Guidelines for Health-Care Facilities. ASHRAE J. 2001;43:29–33. [Google Scholar]

- (49).Nazaroff WW. Residential Air-Change Rates: A Critical Review. Indoor Air. 2021;31:282–313. doi: 10.1111/ina.12785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Persily AK, Gorfain J, Brunner G. Survey of Ventilation Rates in Office Buildings. Build Res Inf. 2006;34:459–466. [Google Scholar]

- (51).Batterman S, Su F-C, Wald A, Watkins F, Godwin C, Thun G. Ventilation Rates in Recently Constructed U.S. School Classrooms. Indoor Air. 2017;27:880–890. doi: 10.1111/ina.12384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).ASHRAE. Ventilation for Acceptable Indoor Air Quality ANSI/ASHRAE Standard. ANSI/ASHRAE; 2019. pp. 62–1. [Google Scholar]

- (53).ASHRAE. ASHRAE Position Document on Infectious Aerosols; American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers. 2020.

- (54).REHVA. How to Operate HVAC and Other Building Service Systems to Prevent the Spread of the Coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) Disease (COVID-19) in Workplaces. Federation of European Heating, Ventilation and Air Conditioning Associations; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- (55).Chen PZ, Bobrovitz N, Premji Z, Koopmans M, Fisman DN, Gu FX. Heterogeneity in Transmissibility and Shedding SARS-CoV-2 via Droplets and Aerosols. Elife. 2021;10:e65774. doi: 10.7554/eLife.65774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Yang Q, Saldi TK, Gonzales PK, Lasda E, Decker CJ, Tat KL, Fink MR, Hager CR, Davis JC, Ozeroff CD, Muhlrad D, et al. Just 2% of SARS-CoV-2.positive Individuals Carry 90% of the Virus Circulating in Communities. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118:e2104547118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2104547118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Wu SL, Mertens AN, Crider YS, Nguyen A, Pokpongkiat NN, Djajadi S, Seth A, Hsiang MS, Colford JM, Reingold A, Arnold BF, et al. Substantial Underestimation of SARS-CoV-2 Infection in the United States. Nat Commun. 2020;11:4507. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18272-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Jones TC, Biele G, Mühlemann B, Veith T, Schneider J, Beheim-Schwarzbach J, Bleicker T, Tesch J, Schmidt ML, Sander LE, Kurth F. Estimating Infectiousness throughout SARS-CoV-2 Infection Course. Science. 2021;373:eabi5273. doi: 10.1126/science.abi5273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Ou C, Hu S, Luo K, Yang H, Hang J, Cheng P, Hai Z, Xiao S, Qian H, Xiao S, Jing X, et al. Insufficient Ventilation Led to a Probable Long-Range Airborne Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 on Two Buses. Build Environ. 2022;207:108414. doi: 10.1016/j.buildenv.2021.108414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Park SY, Kim YM, Yi S, Lee S, Na BJ, Kim CB, Kim JI, Kim HS, Kim YB, Park Y, Huh IS, et al. Coronavirus Disease Outbreak in Call Center, South Korea. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26:1666–1670. doi: 10.3201/eid2608.201274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Khanh NC, Thai PQ, Quach H-L, Thi N-AH, Dinh PC, Duong TN, Mai LTQ, Nghia ND, Tu TA, Quang LN, Quang TD, et al. Transmission of SARS-CoV 2 During Long-Haul Flight. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26:2617–2624. doi: 10.3201/eid2611.203299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Günther T, Czech-Sioli M, Indenbirken D, Robitaille A, Tenhaken P, Exner M, Ottinger M, Fischer N, Grundhoff A, Brinkmann MM. SARS-CoV-2 Outbreak Investigation in a German Meat Processing Plant. EMBO Mol Med. 2020;12:e13296. doi: 10.15252/emmm.202013296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Kriegel M, Buchholz U, Gastmeier P, Bischoff P, Abdelgawad I, Hartmann A. Predicted Infection Risk for Aerosol Transmission of SARS-CoV-2. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.10.08.20209106. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Stein-Zamir C, Abramson N, Shoob H, Libal E, Bitan M, Cardash T, Cayam R, Miskin I. A Large COVID-19 Outbreak in a High School 10 Days after Schools’ Reopening, Israel, May 2020. Eurosurveillance. 2020;25:1–5. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.29.2001352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Nardell EA, Keegan J, Cheney SA, Etkind SC. Airborne Infection: Theoretical Limits of Protection Achievable by Building Ventilation. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991;144:302–306. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/144.2.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).Gammaitoni L, Nucci MC. Using a Mathematical Model to Evaluate the Efficacy of TB Control Measures. Emerg Infect Dis. 1997;3:335–342. doi: 10.3201/eid0303.970310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (67).Moser MR, Bender TR, Margolis HS, Noble GR, Kendal AP, Ritter DG. An Outbreak of Influenza Aboard a Commercial Airliner. Am J Epidemiol. 1979;110:1–6. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (68).Remington PL, Hall WN, Davis IH, Herald A, Gunn RA. Airborne Transmission of Measles in a Physician’s Office. JAMA. 1985;253:1574–1577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (69).Wilson NM, Marks GB, Eckhardt A, Clarke AM, Young FP, Garden FL, Stewart W, Cook TM, Tovey ER. The Effect of Respiratory Activity, Non-Invasive Respiratory Support and Facemasks on Aerosol Generation and Its Relevance to COVID-19. Anaesthesia. 2021;76:1465. doi: 10.1111/anae.15475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (70).James G, Witten D, Hastie T, Tibshirani R. An Introduction to Statistical Learning: With Applications in R, Springer texts in statistics. 1st ed. Springer; New York, NY: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- (71).Milton DK, Fabian MP, Cowling BJ, Grantham ML, McDevitt JJ. Influenza Virus Aerosols in Human Exhaled Breath: Particle Size, Culturability, and Effect of Surgical Masks. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003205. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (72).Lindsley WG, Noti JD, Blachere FM, Thewlis RE, Martin SB, Othumpangat S, Noorbakhsh B, Goldsmith WT, Vishnu A, Palmer JE, Clark KE, et al. Viable Influenza A Virus in Airborne Particles from Human Coughs. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2015;12:107–113. doi: 10.1080/15459624.2014.973113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (73).Yan J, Grantham M, Pantelic J, Bueno de Mesquita PJ, Albert B, Liu F, Ehrman S, Milton DK, EMIT Consortium Infectious Virus in Exhaled Breath of Symptomatic Seasonal Influenza Cases from a College Community. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115:1081–1086. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1716561115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (74).Tiemersma EW, van der Werf MJ, Borgdorff MW, Williams BG, Nagelkerke NJD. Natural History of Tuberculosis: Duration and Fatality of Untreated Pulmonary Tuberculosis in HIV Negative Patients: A Systematic Review. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17601. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (75).Bueno de Mesquita PJ, Noakes CJ, Milton DK. Quantitative Aerobiologic Analysis of an Influenza Human Challenge transmission Trial. Indoor Air. 2020;30:1189–1198. doi: 10.1111/ina.12701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (76).Mikszewski A, Stabile L, Buonanno G, Morawska L. The Airborne Contagiousness of Respiratory Viruses: A Comparative Analysis and Implications for Mitigation. Geosci Front. 2021:101285. doi: 10.1016/j.gsf.2021.101285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (77).Conly J, Seto WH, Pittet D, Holmes A, Chu M, Hunter PR, on behalf of the WHO Infection Prevention and Control Research and Development Expert Group for COVID-19. Conly J, Cookson B, Pittet D, Holmes A, et al. Use of Medical Face Masks versus Particulate Respirators as a Component of Personal Protective Equipment for Health Care Workers in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2020;9:126. doi: 10.1186/s13756-020-00779-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (78).Klompas M, Baker MA, Rhee C. Airborne Transmission of SARS-CoV-2: Theoretical Considerations and Available Evidence. JAMA. 2020;324:441–442. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.12458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (79).Tang JW, Bahnfleth WP, Bluyssen PM, Buonanno G, Jimenez JL, Kurnitski J, Li Y, Miller S, Sekhar C, Morawska L, Marr LC, et al. Dismantling Myths on the Airborne Transmission of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) J Hosp Infect. 2021;110:89–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (80).Chan WR, Li X, Singer BC, Pistochini T, Vernon D, Outcault S, Sanguinetti A, Modera M. Ventilation Rates in California Classrooms: Why Many Recent HVAC Retrofits Are Not Delivering Sufficient Ventilation. Build Environ. 2020;167:106426 [Google Scholar]

- (81).WHO. Roadmap to Improve and Ensure Good Indoor Ventilation in the Context of COVID-19. World Health Organization; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- (82).Rudnick SN, Milton DK. Risk of Indoor Airborne Infection Transmission Estimated from Carbon Dioxide Concentration. Indoor Air. 2003;13:237–245. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0668.2003.00189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.est.1c06531.

Derivation of the factor accounting for the deviation from the steady state, details of Monte Carlo uncertainty propagation for the fitting of attack rates vs Hr, evaluation of the fitting in Figure 1b, rE and rB for different vocalization and physical intensity levels, details of the conditions for Table 2, details of the setting in Figure 2, and screenshot of the COVID-19 Aerosol Transmission Estimator (PDF)