Abstract

Background:

Stopping antidepressants commonly causes withdrawal symptoms, which can be severe and long-lasting. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance has been recently updated to reflect this; however, for many years withdrawal (discontinuation) symptoms were characterised as ‘usually mild and self-limiting over a week’. Consequently, withdrawal symptoms might have been misdiagnosed as relapse of an underlying condition, or new onset of another medical illness, but this has never been studied.

Method:

This paper outlines the themes emerging from 158 respondents to an open invitation to describe the experience of prescribed psychotropic medication withdrawal for petitions sent to British parliaments. The accounts include polypharmacy (mostly antidepressants and benzodiazepines) but we focus on antidepressants because of the relative lack of awareness about their withdrawal effects compared with benzodiazepines. Mixed method analysis was used, including a ‘lean thinking’ approach to evaluate common failure points.

Results:

The themes identified include: a lack of information given to patients about the risk of antidepressant withdrawal; doctors failing to recognise the symptoms of withdrawal; doctors being poorly informed about the best method of tapering prescribed medications; patients being diagnosed with relapse of the underlying condition or medical illnesses other than withdrawal; patients seeking advice outside of mainstream healthcare, including from online forums; and significant effects on functioning for those experiencing withdrawal.

Discussion:

Several points for improvement emerge: the need for updating of guidelines to help prescribers recognise antidepressant withdrawal symptoms and to improve informed consent processes; greater availability of non-pharmacological options for managing distress; greater availability of best practice for tapering medications such as antidepressants; and the vital importance of patient feedback. Although the patients captured in this analysis might represent medication withdrawal experiences that are more severe than average, they highlight the current inadequacy of health care systems to recognise and manage prescribed drug withdrawal, and patient feedback in general.

Keywords: antidepressant, benzodiazepines, discontinuation, informed consent, lean thinking, patient feedback, prescribed drug dependence, withdrawal

Introduction

Antidepressant withdrawal symptoms

Although National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance has for many years indicated that withdrawal from antidepressants is ‘mild and self-limiting’,1 and the Royal College of Psychiatrists (RCPsych) and the Royal College of General Practitioners (GPs) widely promulgated the idea that discontinuing antidepressants ‘will not be a problem’ during the ‘Defeat Depression Campaign’ of the 1990s,2 there is now increasing recognition of the problems faced by patients withdrawing from antidepressants.3–6 Recent systematic reviews of withdrawal symptoms from antidepressants have drawn attention to the fact that withdrawal symptoms are more common, more severe and longer-lasting than previously supposed,5,7,8 30 years after antidepressant withdrawal symptoms from the new generation antidepressants were first reported,7 and 20 years after they were first demonstrated in a double-blind, placebo-substitution randomised trial.9

Despite heated debate, there is general consensus that withdrawal affects at least a third or a half of patients stopping antidepressants5,10; evidence indicates that this is likely to be less common for short term users,11 and more common for long-term users.5,12,13 Surveys of patients suggest that in about half of cases of withdrawal the symptoms experienced will be severe, with severity also found to be related to duration of use,5,12 although some commentators have suggested that survey data may have captured patients with more severe symptoms than average.11 Dissenting views have tended to focus on studies in short term antidepressant use (about 12 weeks),11 in which the withdrawal symptoms are, unsurprisingly, less common, given the recognised relationship between duration of use and severity of withdrawal symptoms.12,13 Notably, in the reported surveys about half of respondents were on antidepressants for more than 3 years,5 very similar to the general British population of antidepressant users, of whom at least half have been on antidepressants for more than 2 years,14 with about a million people taking them for more than 3 years.3

Although data for establishing the duration of withdrawal effects are sparser, there is evidence to suggest that patients who have withdrawn from antidepressants can experience symptoms that last for months, and, sometimes, for years.5,15,16 Consequently, both RCPsych and NICE have updated their guidance to recognise that antidepressant withdrawal can be more severe and long-lasting than previously recognised; symptoms can last ‘months or more’ and can be ‘more severe for some patients’.1,4,17

Mistaking withdrawal for relapse or another medical condition

It has also been noted in several reviews of antidepressant withdrawal symptoms that such reactions can be mistaken for relapse of the underlying condition for which the antidepressant was originally prescribed,18–20 and this has been highlighted in the DSM-521; however, the degree to which this occurs has never been quantified.22 Furthermore, previous accounts have highlighted that when antidepressant withdrawal is not recognised it may be mistaken for the onset of another medical illness, including stroke, other neurological conditions, infectious disease and adverse effects of other medications the patient is taking, leading to unnecessary and expensive interventions and management.23,24

It is probable that misdiagnosis of withdrawal as relapse or other medical illness occurs often because NICE guidance has, for more than a decade, characterised antidepressant withdrawal symptoms as ‘usually mild and self-limiting over about a week’.1 It would be understandable, following this characterisation of withdrawal symptoms, for GPs, or psychiatrists to believe that patients presenting with severe or long-lasting symptoms following reducing or stopping their antidepressant could not be explained by withdrawal symptoms but must be due to an alternative, such as relapse or new onset of another medical disorder. This understanding of withdrawal symptoms as mild and transient may also account for why doctors rarely inform patients of the risk of withdrawal symptoms when they are started on an antidepressant.12,25

The experience of patients with antidepressant withdrawal symptoms and their interaction with the health system

The experience of withdrawal symptoms by patients has been revealed by a series of studies over the last few years,12,25 which have found that withdrawal symptoms are often experienced as severe,12 and that GPs have differing responses to patient requests to come off their medication.26 Previous studies have also found that GPs lack confidence in their ability to manage antidepressant withdrawal and find existing guidance inadequate.27,28

However, previous research has not investigated the experience of patients who suffer antidepressant withdrawal symptoms and seek help for these problems from the health system. The occasion of a general call for accounts of patients who experienced dependence and withdrawal from prescribed drugs (of which two-thirds concerned antidepressants) and their interaction with the health system for inclusion in petitions for the Scottish and Welsh parliaments provided rich, qualitative accounts of the trajectory of patients though the health system, outlined in this paper.

Methods

Study design

People impacted by prescribed drug withdrawal symptoms were invited to submit personal accounts of their experiences as part of the process for two petitions lodged with parliamentary Committees in Scotland in 2017 and in Wales in 2018.29,30

For the Scottish petition, participants were invited to submit their experience in the form of emails to petition clerks, who then processed these submissions. There was no prescribed structure to their accounts, allowing them to describe their experience in their own words. There was no restriction on age or country of origin. The opportunity to participate was circulated via social media and relevant online platforms.

Participants in the Welsh petition were invited to submit views by email to the Senedd Petitions team between February and March 2018.30 Responders were invited to respond to four prompts about their experience:

Your experience of prescribed drug dependence and withdrawal.

What support services are available to people experiencing prescribed drug dependence and withdrawal, particularly in Wales, and whether these are sufficient?

The extent to which prescribed drug dependence and withdrawal is a recognised issue amongst health professionals and the general public.

Any actions that can be taken to improve the experience of those affected by prescribed drug dependence and withdrawal, including in terms of prevention, management and support.

The opportunity to submit views was circulated by email to relevant patient, medical and interest groups and posted on relevant patient social media groups. The country of origin was restricted to Welsh citizens only, but the age of participants was not restricted.

An earlier analysis of the material captured in these petitions was included in the Public Health England review on ‘Dependence and withdrawal associated with some prescribed medicines’ in the category of ‘grey literature’3; the National Guideline Centre described the accounts as ‘a reasonable representation of patients’ experiences’, with ‘high confidence in the findings’.31

Research team and reflexivity

Thematic analysis was performed by AG (PsychD), psychotherapist; MB (MBA), retired psychotherapist; SL [BA (Hons), PG DipIM], lived experience expert, with additional support from Susan Reid (PGDip), psychotherapist and ex-nurse, and Karen Espley (MBA), business consultant and ex-nurse, for response analysis, and David Cope (BSc) process mapping improvement consultant and Catherine Maryon (MA) for data analysis. The lead researcher has a doctorate in psychotherapy (PsychD) as well as a background in process improvement in the financial services industry. Whilst some of the petition responders were known to the petitioners, the idea to analyse submissions only arose after they were all made – there was no direct contact with any petition responder.

Methodological orientation and theory

Mixed qualitative and quantitative methods were used to analyse the accounts collected. Formal thematic analysis was applied using a ‘lean thinking’ approach,32 a process analysis and improvement philosophy now commonly adopted across private and public sectors, including the NHS.33 This analysis aims to identify systemic ‘failure points’ which generate significant process ‘waste’ (that is, anything which does not improve or add value to patient care and experience). The two questions framing thematic analysis were ‘what went wrong?’ and ‘what are the points for improvement?’ A thematic data capture tool was created based on common themes emerging from the patient data, consensually agreed upon by the three principal analysts. A cyclical process was employed whereby patient accounts were used to generate further themes until thematic saturation was achieved. Patient accounts were then analysed using the resultant thematic framework. Only one researcher had personal experience of prescribed drug dependence and withdrawal and analysed 6% of the sample. Results from the data capture were summarised, reviewed and overlaid on a framework of two representative patient ‘journeys’ covering initial prescription and withdrawal experiences, summarised as maps (see Supplemental Figures).

Results

Demographic characteristics of respondents

As the petition was not structured, demographic details were given at the respondents’ discretion. There were 158 participants. Of the 80% who reported gender, 75% were female, and 25% were male. Of the 21% who reported age, the average age (+/– SD) was 49.2 (+/–14.6) years (range 21–73). Participants were mostly from the United Kingdom (UK; 28%), the United States (US; 8%), Europe (3%), elsewhere (8%), with 54% not specifying where they were from.

Thematic summary

Thematic analysis was divided into two representative patient ‘journeys’ – ‘Initial prescription and outcomes’, and ‘Withdrawal’. Each of these representative journeys revealed sub-themes, which are outlined below.

Initial prescription and outcomes

Description of initial prescription

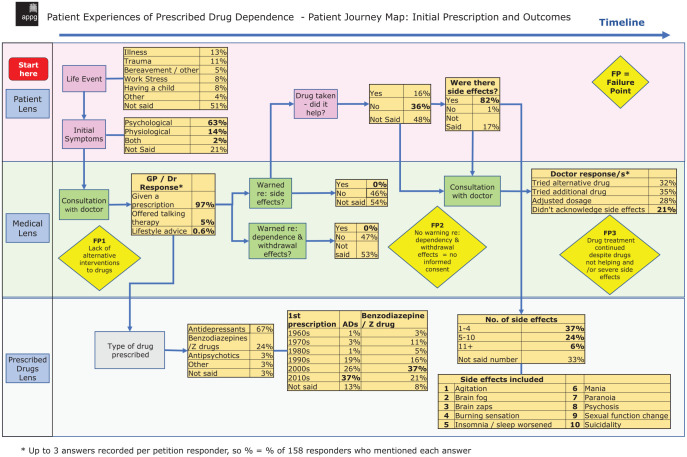

Almost half of participants (44%) identified a significant life event as the precipitant that led to the initial prescription of a psychotropic agent, with the remaining proportion not specifically addressing this issue in their account (Figure 1): 13% reported illness, 11% reported trauma, 8% reported work stress, 8% reported having a child, 5% reported bereavement and 4% reported ‘other’ as the life events that prompted seeking help from a doctor.

Figure 1.

Patient Experiences of Prescribed Drug Dependence – Patient Journey Map: Initial Prescription and Outcomes.

A total of 97% of respondents were offered a prescription on their initial consultation with a doctor, 5% reported being offered talking therapy and 0.6% were offered lifestyle advice (with some patients offered more than one option).

Prescription characteristics

A total of 67% of patients were initially prescribed antidepressants, 24% were prescribed benzodiazepines and z-drugs, 3% were prescribed antipsychotics, 3% were prescribed ‘other’ and 3% did not specify. For patients prescribed antidepressants the modal decade of prescription was 2010–2020 (37% of respondents), whereas for patients prescribed benzodiazepines the modal decade of prescription was 2000–2010 (37%). In the 44% of patients who provided both starting year and ending year of their prescription, and so allowed calculation of duration of use, average period of use was 9.8 years, with a standard deviation of 10.3 years. The duration of use varied from less than 1 year to 41 years of total use.

Patient counselling about side effects and withdrawal

On receiving their first prescription, 46% of responders reported that they were not warned about side effects, 0% reported being warned and 54% of patients did not address this issue in their account. One patient said:

‘GPs and psychiatrists have never warned me of the side effects [of venlafaxine] or difficulties I might face in withdrawal. They have all however been very keen to increase dosage and discharge me.’

On initiation of their prescription 47% of responders reported not being warned about withdrawal issues, 0% said they had been warned and 53% did not mention this in their account. Patient accounts include:

‘My baby. . .had convulsions at 8 h after birth directly attributed to withdrawal from maternal Anafranil [anti-depressant]. Psychiatrist unaware this could be a problem’.

After I stopped the drug….To this day I do not experience actual [sexual] arousal. . .Doctors didn’t tell me about such severe side effects, not to mention about them persisting for years on.

Antidepressant therapeutic effect and side effects

In terms of the therapeutic effects of the medication prescribed, 16% of respondents reported that the medication was helpful, 36% reported that it was not helpful and 48% did not mention efficacy.

In terms of side effects, 82% of patients reported side effects that arose from the medication they were prescribed, 1% reported there were no side effects and 17% did not mention side effects. Some of the side effects reported were agitation, ‘brain fog’, ‘brain zaps’, burning sensation, insomnia, mania, paranoia, psychosis, sexual function impacted and suicidality. Of the patients who experienced side effects, 37% reported 1–4 side effects, 24% reported 5–10 side effects, 6% reported 11 or more side effects and 33% did not report the number of side effects. One patient reported:

‘When I started taking Venlafaxine around July I was suffering low mood and migraine pain. By October my mood was completely haywire. Big highs followed by big drops. I went to my local GP who increased the dose. My mood deteriorated rapidly and my mood which was already highly unstable became totally unstable and I was experiencing highs and deep lows within a matter of hours as opposed to over the week. I thought I was losing my mind.’

When patients reported side effects to their physician, the response of their doctor varied widely: 32% tried an alternative drug, 35% added another drug, 28% adjusted the dosage and in 21% of cases the doctor dismissed the idea that the side effects were related to the prescribed drug.

Withdrawal and outcome

Process of withdrawal

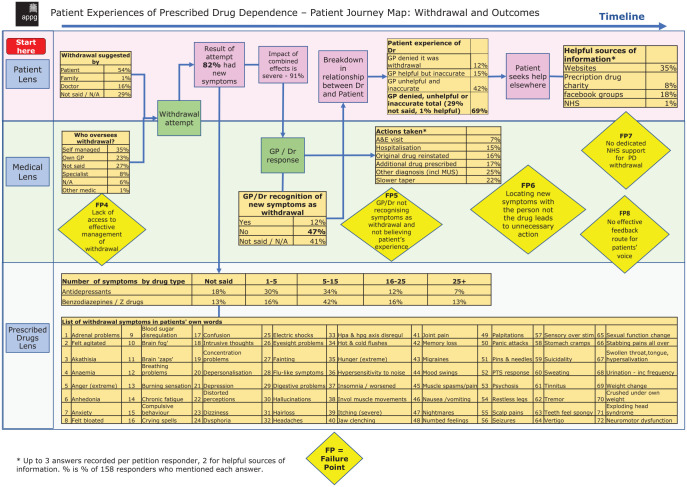

In terms of the decision to withdraw from their medication, 54% of patients made the decision themselves, family members suggested this course of action in 1% of cases and doctors in 16% of cases; 29% of respondents did not include this in their accounts.

In terms of supervision of the medication withdrawal process, 35% of responders self-managed their withdrawal, 23% were overseen by a GP, 8% by a specialist and 1% by another doctor; 33% of patients did not specify who oversaw their withdrawal.

Following reduction of their psychotropic dose, 82% of respondent reported the onset of new symptoms. Some of the symptoms experienced by patients include: agitation, akathisia, anhedonia, anxiety, ‘brain fog’, brain ‘zaps’, compulsive behaviour, difficulty concentrating, confusion, crying spells, de-personalisation, depression, dizziness, hallucinations, insomnia, muscle spasms, gastrointestinal upset, numbed feelings, panic attacks, psychosis, seizures, sweating and vertigo, with further symptoms shown in Figure 2. For people who reduced their antidepressant, 7% reported experiencing 25 or more new onset symptoms, 12% reported 16–25 symptoms, 34% reported 5–15 symptoms and 30% reported 1–5 symptoms (with 18% not specifying this); 91% of respondents described that these symptoms in overall effect were ‘severe’.

Figure 2.

Patient Experiences of Prescribed Drug Dependence – Patient Journey Map: Withdrawal and Outcomes.

Response of the health system

Many patients approached their doctors for assistance with their withdrawal symptoms, and discussed the response of their doctors to their complaints. Whilst 47% of responders reported that their treating doctors did not recognise their symptoms as being related to medication withdrawal, 12% did; 41% of respondents did not mention this issue.

The response of the doctor to the onset of withdrawal symptoms following reduction of their dose of antidepressant (or benzodiazepine) was to recommend attendance at the accident and emergency department (7%), to recommend hospitalisation (15%), to offer additional medication (17%), to re-instate the original drug (16%) or to make the diagnosis of onset of a new medical condition, such as medically unexplained symptoms (25%). In 22% of cases, the doctor recommended a slower taper to manage the withdrawal symptoms.

Some representative responses include:

‘I got no help from my doctors. Due to the extreme involuntary movements, my neurologists diagnosed me with a “functional movement disorder”, migraines, and chronic fatigue syndrome. I had none of these issues before taking and stopping the Venlafaxine.’

‘The doctor started talking to me and acting like I was a junky - he advised that I stop taking them immediately.’ ‘My psychiatrist wouldn’t entertain the idea of protracted withdrawal. My psychiatrist kept saying my symptoms were somatic or medically unexplained.’

The patients’ reports about the helpfulness and accuracy of prescribers’ knowledge about psychotropic drug withdrawal varied: in 12% of cases the doctor denied that the symptoms were related to withdrawal, in 15% the doctors were helpful but inaccurate, 42% were unhelpful and inaccurate and 1% were helpful (Figure 2).

Some representative responses included:

‘Whilst on and trying to get off these meds (mainly SSRIs) I’ve experienced incredible denial and confusion amongst GPs and psychiatrists. At the point where four different psychiatrists gave me four different diagnoses and prescriptions in the same month this became very clear. You’re essentially on your own on this journey, and no, your friends and family probably won’t understand.’

‘The first time that I felt some sort of control over my condition was when we went for the second opinion – and everything that I said was believed. That…is vital to coping with dependence and, again, in withdrawal.’

As a result of their interaction with their treating doctor, many patients sought help elsewhere: 25% of responders sought help from websites (e.g. Surviving Antidepressants and BenzoBuddies), 8% sought help from a prescription drug charity, 18% of responders sought advice from Facebook groups and 1% sought advice from the National Health Service (NHS). Respondents commented:

‘I have nobody I can discuss any of this with and I am really shocked that there is no support or information whatsoever available to people in my position.’

‘The Surviving Antidepressants group [online discussion board regarding tapering from antidepressants] has been an oasis for me.

The impact of withdrawal

The responders reported a significant impact of their withdrawal symptoms: 47% reported loss of a job as a consequence of their withdrawal, 9% reported loss of their home, 20% reported loss of friends, 17% lost their relationship, 35% experienced financial hardship, 27% lost hope and 82% experienced a loss of health and wellbeing (Figure 2). Those who described these matters reported, on average, that 15 years of their life had been impacted.

Patients said:

‘If I had been offered a talking therapy 17 [years] ago instead of mind numbing, habit-forming drugs that my life, career and health would be in a much better place than it now is.’

‘I regressed from an amateur international athlete to a very ill, depressed and withdrawn individual. At low points I considered suicide.’ ‘I continue to fight to get my life back, I could write a novel on the amount of suffering I have endured thanks to SSRI use. It has effected (sic) every part of my life, I can’t work, I am not able to be active and even worse I can’t get help because the prescribers are in the dark about the true harms of the drugs they prescribe.’ ‘Before I was put in this situation I was a “normal” person doing things like most people are doing, have always supported myself, working full time. I have lost all savings, small investment and close to losing my home.’ ‘Words cannot describe the utter hell, torment and terror that I have lived [through] and continue to battle through every single day and not one ounce of help, empathy or sympathy from any doctor.’

Discussion

In the patient accounts analysed, there were several common themes that emerged. These are discussed in terms of the common ‘failure points’ (that is, where the process generated ‘non-value’ added outcomes), and potential solutions to each of these are proposed.

Initial prescription

A prescription was offered as an apparent first course of action with little evidence of alternatives having been offered, including psychotherapy, social prescribing or ‘active monitoring’, as recommended by the NICE guidelines.17 In a cohort of patients prescribed antidepressants in New Zealand, 82% of patients were offered at least one recommendation of a non-pharmacological therapy (mostly psychotherapy) when prescribed antidepressants,34 much greater than the 5.6% in the cohort presented here, suggesting that this cohort received less holistic care than usual.

There is ongoing debate about whether the small differences in depression scores after several weeks of treatment between antidepressants and placebo are clinically significant.35–37 These small effects should be placed in context with the risk of harms, including withdrawal effects from the medication.38 Treatment with these medications often occurs over many months or years so short-term studies are of limited relevance, and there are few long-term studies. Consequently, it has been suggested that it is not evidence-based to recommend these medications for long-term use in the treatment of depression.39

Specifically, the current NICE guidance17 recommending antidepressant use is based on a methodologically flawed meta-analysis examining ‘relapse prevention’ studies.40 In these discontinuation studies, patients are switched either abruptly or very rapidly (most between 1 day and 4 weeks) from antidepressant to placebo, and their relapse rate compared with patients maintained on antidepressants. Relapse rates recorded in the group switched to placebo exceed those in group maintained on antidepressants and this forms the basis of the evidence for relapse prevention properties of antidepressants.17 However, in these studies, withdrawal effects from the rapid discontinuation of antidepressants are ignored, inflating the apparent rate of relapse recorded in this group, therefore exaggerating the perceived ‘relapse prevention’ properties of antidepressants.20,41 Given these methodological flaws this evidence has been described as ‘uninterpretable’ and NICE guidance based on this evidence should be updated appropriately, acknowledging the lack of robust evidence for relapse prevention properties.20

Minimisation of these methodological flaws has led to antidepressants being presented as more effective than is warranted by existing data.20,38,42,43 As a consequence of the minimisation of their withdrawal effects, as well as a number of their other side effects (perhaps reflected in the infrequency with which GPs discuss these issues with patients), antidepressants have also been regarded as more safe that is warranted by existing data.42–45 Moreover, the theory that depression is caused by a monoamine deficiency, now largely abandoned by academic psychiatry due to a lack of evidence,4 continues to prevail in wider society influencing the decision to prescribe antidepressant medication, unjustifiably.44,46 An exaggeration of the benefits of antidepressants and a minimisation of their harms has led to an overall impression that this class of medication is safe and effective, and GPs have therefore been encouraged to prescribe them widely, and have done so. Some of the consequences of these actions have been outlined in these patients’ reports.

Therefore, preventative actions would involve updated guidance that reflects the methodological flaws of existing research into antidepressant use, and the recommendation and provision of increased availability of non-pharmacological interventions for depression and anxiety, such as talking therapy or social prescribing. Further education of the public and GPs about the benefits and risks of antidepressant medication would also manage expectations about what might be most helpful when people experience distress.

Lack of informed consent

There was a lack of information provided to patients about the side effects of antidepressants and the risk of withdrawal symptoms, with no respondents reporting that they had been informed about potential side effects and none about potential withdrawal effects (although many patients did not mention this issue explicitly). Other studies have found that a lack of informed consent around antidepressants is highly prevalent, including one study in UK adults which found that 40% of patients reported that they were not given enough information about adverse effects or withdrawal (although 48% felt they had received enough information).26 In an international cohort, 0.6% of patients were told about the possibility of withdrawal effects when they started antidepressants,12 and 1% were informed in a cohort in New Zealand.25 The number of respondents in our sample who felt they had been given enough information about side effects was much lower than in other cohorts, perhaps reflecting the earlier period at which many of them had been started on medication. However, the finding in our sample that patients are routinely not warned about withdrawal effects seems consistent across different samples.

All doctors should endeavour to provide patients considering antidepressants enough information to make an informed decision, and this includes information about potential adverse effects, the potential for withdrawal effects (including the possibility that these can be severe and long-lasting). In order for the updated NICE guidance on withdrawal effects to be adequately communicated to patients, this information should be incorporated into medical education and continuing professional education.

Ongoing prescription of medication despite unfavourable harm/benefit ratio

Despite a proportion of patients having a significant side effect burden in the context of minimal benefits from their medication, prescriptions were continued for long periods. Previous studies have identified a lack of regular reviews by GPs of patients on long-term antidepressant treatment and this may be one barrier to appropriate de-prescribing of these medications.47 Furthermore, in response to reports of side effects in our sample, doctors either added another drug, switched to another drug, altered dose or dismissed the connection between the effect and the drug. In no case did the doctor stop the drug and consider alternative approaches; such an approach may have been beneficial.

Preventative actions therefore include regular review of antidepressant prescriptions, especially soon after initiation, and better training for doctors regarding side effects, including manic symptoms. In the case of unfavourable balance of harm and benefit GPs should feel confident in stopping medication and re-evaluating the role of non-pharmacological interventions before considering switching to another medication or increasing the dose.

Lack of access to effective management/informed medical oversight of the withdrawal process

A common theme amongst respondents was a lack of access to effective management or supervision of the medication discontinuation process from their treating doctor. Many patients resorted to self-management or advice through online websites, prescription drug charities or Facebook groups. Only 1% felt that their GPs were helpful sources of information. Few GPs correctly suggested that patients may need to reduce their dose more gradually in response to their withdrawal symptoms.48

Patients reported that GPs recommended tapers that were too quick, causing intolerable withdrawal symptoms. Previous research has identified that GPs do not feel confident in their knowledge of helping patients to come off antidepressants49; in particular, they described being dissatisfied with current NICE guidance, indicating that ‘it is unclear (especially regarding tapering regimes), limited, not accessible and at times not applicable to real patients’,50 with one GP describing the current NICE guidance on discontinuing antidepressants ‘as a bit pants’.50 A lack of sufficient information on discontinuation was also identified as a key issue for GPs.27,49 The same concerns were reported by GPs in Holland.28,51

This suggests that the NICE guidance on how to discontinue antidepressants needs to be updated, and new guidance on Safe Prescribing and Withdrawal from prescribed drugs associated with dependence will hopefully contribute to best practice in this area.52 Overall, there has been scant attention paid to the issue of antidepressant tapering previously in the academic literature,48,53–56 which has been focused primarily on starting medication.57 The ANTLER and REDUCE trials are ongoing, but further trials will be required in order to provide detailed advice to GPs on how to taper medications. It is notable that there is vast expertise that has been accrued by patients in peer support networks managing the issues of antidepressant and benzodiazepine withdrawal.56,58,59 It is also concerning that so many patients found that their treating physician dismissed the notion that their symptoms could be due to antidepressant withdrawal, meaning many patients were forced to turn to these peer support networks for support and medical advice.

Further training of GPs in this area is needed,54 including planning for treatment ending when treatment is initiated; training in up-to-date information on tapering strategies (that these patients predominantly accessed through online patient communities); and the need to warn patients about possible withdrawal effects and the need for slow tapering. A useful guide for GPs to discuss antidepressant discontinuation with their patients has been developed.54

Failure to recognise withdrawal symptoms

A common theme amongst respondents was the failure of their doctors to recognise their symptoms as related to antidepressant withdrawal. Most patients said that their doctor had either not correctly identified the new onset of symptoms following dose reduction as withdrawal, denied withdrawal, were unhelpful or gave inaccurate information, with only 1% of patients reporting that their doctor was helpful. It is perhaps understandable that doctors form this view because of the inherited understanding that withdrawal symptoms are ‘usually mild and self-limiting’ as articulated in NICE guidelines for many years, concluding that severe and long-lasting symptoms could not be withdrawal but must represent relapse or the onset of new illness.

The issue of ‘relapse’ being mistaken for withdrawal symptoms has been a long-running issue of concern amongst experts,18 including the DSM-5 explicitly warning about this possibility.21 The experience of this sample brings to light, for the first time, the extent to which antidepressant withdrawal symptoms are mistaken for relapse, due to the widespread lack of awareness of withdrawal symptoms amongst GPs. There were several consequences of this misdiagnosis. Respondents reported that the relationship with their treating doctor was undermined, with many losing faith in the ability of their doctor to manage their issues, leading to 51% of respondents seeking help from unregulated, non-medical sources, most often online.

Preventative action would include better education of doctors about the likelihood of withdrawal symptoms, the possibility of severe and long-lasting reactions and the wide variety of symptoms that can be experienced by patients. The update to the NICE guidance is one step towards this; however, it needs to be bolstered by widespread updating of medical education and continuing professional development. GPs should be aware that withdrawal symptoms from antidepressants are common, and can be severe and long-lasting; the most useful response to this should be to recommend slower tapers of medication at a rate that is tolerable to the patients.4,48 Given estimates that withdrawal occurs in up to 50% of patients stopping antidepressants,5,10 while relapse has been detected in 41% of such patients (with this value undoubtedly inflated by misdiagnosis of withdrawal symptoms),20 it should be recognised that withdrawal reactions are as common or more likely than relapse, and the index of suspicion adjusted accordingly. There are two withdrawal scales that may help physicians in monitoring withdrawal symptoms – the Discontinuation-Emergent Signs and Symptoms (DESS) and the Diagnostic Clinical Interview for Drug Withdrawal 1 (DID-W1).9,60

The lack of recognition of withdrawal led to unnecessary tests and referrals

A further consequence of this misdiagnosis of antidepressant withdrawal was that patients were diagnosed with a variety of conditions including ‘medically unexplained symptoms’ (MUS), or ‘functional neurological disorder’. The original petitioners felt that this had the effect of ‘disempowering and demoralising these patients still further’.29,30 Furthermore, this led to emergency presentations, hospitalisations, and further investigations all causing unnecessary costs to the healthcare system and distress to the patient. This phenomenon has been identified before,23 but how widespread this might be has not been quantified; the current sample suggests that this issue may more prevalent than previously supposed.

In this sample, 25% of patients with antidepressant withdrawal presenting to their GP were diagnosed with MUS, a ‘functional neurological disorder’ or ‘chronic fatigue syndrome.’ Many of the signs and symptoms associated with these medically unexplained disorders, captured in the often used PHQ-15,61 overlap with the symptoms of antidepressant withdrawal, including insomnia, feeling tired, nausea, indigestion, racing heart, dizziness, headaches and back pain.62 For physicians who have been systematically educated to regard antidepressant withdrawal symptoms as ‘mild and self-limiting’, the description of a wide constellation of symptoms persisting for long periods by patients who have stopped antidepressant may be more recognisable under the rubric of MUS. In addition to the unnecessary costs to the health system, many patients highlighted in their accounts how invalidating and distressing it was to not be believed by their doctors, while experiencing incapacitating and severe symptoms.

If withdrawal had been identified accurately, and managed appropriately, resources would have been saved, and exposure of patients to unnecessary investigation and treatment, and the distress caused by this process could have been avoided. This further emphasises the benefits of training doctors to accurately recognise and manage withdrawal.

No dedicated nationwide NHS services to access for help

A near-universal theme amongst these respondents was a lack of support for withdrawal. One way to remediate this need would be to institute a nationwide service, specialising in withdrawal from prescribed medications. This was recommended by Public Health England (PHE) review in 2019,3 including the following policy recommendations:

the creation of a national helpline and associated website to provide expert advice for prescribed drug dependence;

an increase in provision of specialist ‘tiered support’ services

revised guidance for doctors on safe prescribing, management and withdrawal of prescription drugs.

There is an urgent need to identify existing patients (including those given diagnoses such as ‘medically unexplained symptoms’) and to reach out to them to provide appropriate dedicated services.

There have been are varying responses in the UK following the submission of the petition that this survey was based upon.3 In England, NHS England and NHS Improvement have established a prescribed medicines oversight group to oversee implementation of the NHS recommendations from the PHE review on prescription drug dependence. In Wales, while the Petitions Committee was clear in its recommendations that the government should as a priority investigate the national rollout of a prescribed medications support service (currently operating only in North Wales), the Health Secretary in his reply indicated his preference that ‘primary care should be the first point of access’ and ‘drug treatment services should provide support where necessary’ – drug treatment services here refers to the substance misuse sector.63 The Scottish Government is currently progressing its own Short Life Working Group investigation to incorporate the results of the PHE review. Notably, deprescribing services exist outside of the UK – for example in Florence, Italy.64

Feedback from patients on their experience

A final ‘failure point’ is that there currently appears to be no effective review of performance for this system as a whole, involving collection of feedback from patients. This underlies many of the failure points outlined above, leading to patients being caught in a loop where their concerns are not heard, services are not designed to match their needs and they resort to pursuing healthcare outside of traditional contexts.

This issue is not confined to patients suffering antidepressant withdrawal and is generalised to other conditions. For example, the Scottish Parliament commented during an inquiry into transvaginal meshes on: ‘the difficulties that patients face in being believed when they tell clinicians what they are experiencing’, expressed ‘alarm at the apparent disregard of patients’ evidence of the devastating and debilitating impact that mesh has had on their lives’ and recommended that the Scottish Government undertake an exercise to ‘understand why this is such a common concern and what steps can be taken to ensure that patient voices are listened to and heard’.65 This is echoed in the findings of the Cumberledge report regarding the response of the health system to patients’ experience of harm from medical treatments: ‘The lack of such vigilant, long-term monitoring has been a predominant thread throughout our work. Its absence means that the system does not know the scale of the problems we were asked to investigate’.66 This report found that patients harmed by medical treatments reported a lack of information to make informed choices, a ‘struggle to be heard’, ‘not being believed’, ‘dismissive and unhelpful attitudes on the part of some clinicians’, a sense of abandonment, life changing consequences, clinicians not knowing how to learn from patients, and ‘a lack of interest in, and an inability to deliver, the monitoring of adverse outcomes and long-term follow-up across the healthcare system’, mirroring many of the themes in the present analysis.66 Baroness Cumberledge cautioned ‘The system is not good enough at spotting trends in practice and outcomes that give rise to safety concerns. Listening to patients is pivotal to that’.66

Strengths and limitations

The cohort reported in this study is a self-selected sample of patients that volunteered their stories for two parliamentary petitions and not for a formal research study. The major strength of this study is that it has given an opportunity for the ‘patient voice’ to be heard, distinct from previous studies which have examined withdrawal symptoms using rigid lists of symptoms, allowing patients to convey the impact that withdrawal from prescribed drugs has had on their lives and the inadequacy of the help they have received from medical professionals in their own voice. Another strength of this study was that no structure was imposed on respondents, allowing a collection of theme-rich data.

However, the limitations of this approach are that demographic and treatment characteristics were not robustly captured and that respondents had not commented on many aspects of the patient ‘journey’, meaning that there is a significant proportion of responses recorded as ‘not said.’ Given the theme of the petition it is probable that patients with negative experiences of medication withdrawal were more likely to respond. Therefore, it is possible that this cohort represents cases of more severe and protracted withdrawal than the average patient experiences. However, it should be noted that a recent systematic review has found that at least half of patients experience withdrawal symptoms from antidepressants, and half of those reported in surveys are severe,5 so while the experiences reported here may be more severe than usual, they are unlikely to be isolated cases. There is also likely to be a large group of patients who were told that they were relapsing when experiencing withdrawal symptoms (as were many of the patients in this cohort) and who accepted this diagnosis and were therefore put back on medication, who are therefore unaware that they experienced withdrawal symptoms.

In part the severity of symptoms reported in this cohort may be related to the long period of time for which these patients were on medication before discontinuation, known to be associated with worse withdrawal symptoms.12 The average period of use in this cohort was 9.8 years, although it included patients with use of less than 1 year, with the longest period of use of 41 years. However, it has been estimated that 3.5 million people in Britain have been on antidepressants for more than 2 years and almost a million people have been on them for more than 3 years,14,3 suggesting that a portion of people may be susceptible to the effects captured in these reports, though perhaps not quite as severely.

A variety of different psychotropic medications were prescribed to respondents to this survey. The most common class of drug used was antidepressants, in two-thirds of respondents, and it was experience with this class of medication that was highlighted throughout. However, there is some confounding with the effects of using and stopping benzodiazepines, z-drugs, and, much less commonly, antipsychotics. It is noteworthy that although these drugs have different pharmacological mechanisms of action, the withdrawal symptoms from both benzodiazepine and antidepressants are phenomenologically remarkably similar,67 although there are distinctions between them.6

A portion of patients captured in this cohort were from countries outside the UK and therefore have given accounts of medical systems that are different from the NHS. However, the majority of respondents who reported country of origin were from the UK meaning lessons can be taken from this survey to apply to the NHS, reflected in the designation of ‘high confidence’ in this evidence by the National Guideline Centre.31

Conclusion

We report here on a cohort of patients who were significantly affected by withdrawal from antidepressant (and other prescribed psychotropic) medication and found the response of the health system to their condition inadequate and distressing. This inadequate response led to misdiagnosis, investigations and further treatment, and caused many respondents to lose faith in the health system and seek help in unregulated peer-led services. It is hoped that lessons can be taken from these experiences and, in line with the recent PHE recommendations, remediations should include: updated guidance about identification of withdrawal symptoms and optimal tapering schedules, which should be widely disseminated and integrated into physician education; dedicated services for those with prescribed drug dependence and withdrawal, including a national help line and appropriately trained staff in primary and secondary care; and an improved feedback mechanism for patients. In this way, patients currently suffering from dependence and withdrawal issues from antidepressants, and other prescribed psychotropic medication, as well as the large group of patients at risk of these problems, can have their health needs managed appropriately by health services, rather than compounded by them.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, Figure_1 for The ‘patient voice’: patients who experience antidepressant withdrawal symptoms are often dismissed, or misdiagnosed with relapse, or a new medical condition by Anne Guy, Marion Brown, Stevie Lewis and Mark Horowitz in Therapeutic Advances in Psychopharmacology

Supplemental material, Figure_2 for The ‘patient voice’: patients who experience antidepressant withdrawal symptoms are often dismissed, or misdiagnosed with relapse, or a new medical condition by Anne Guy, Marion Brown, Stevie Lewis and Mark Horowitz in Therapeutic Advances in Psychopharmacology

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: Anne Guy is a psychotherapist and the co-ordinator for the secretariat of the All-Party Parliamentary Group for Prescribed Drug Dependence. Marion Brown is the originator of the Scottish Petition. Stevie Lewis is the originator of the Welsh Petition.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Anne Guy  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5582-5697

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5582-5697

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

Contributor Information

Anne Guy, Psychotherapist, Secretariat Co-ordinator for the All-Party Parliamentary Group for Prescribed Drug Dependence, Basingstoke, Hampshire, UK.

Marion Brown, Retired Psychotherapist and Co-Founder of a Patient Support Group ‘Recovery and Renewal’, Helensburgh, UK.

Stevie Lewis, Lived Experience of Prescribed Drug Dependence, Cardiff, UK.

Mark Horowitz, University College London, London, UK.

References

- 1. Iacobucci G. NICE updates antidepressant guidelines to reflect severity and length of withdrawal symptoms. BMJ 2019; 367: l6103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Priest RG, Vize C, Roberts A, et al. Lay people’s attitudes to treatment of depression: results of opinion poll for defeat depression campaign just before its launch. BMJ 1996; 313: 858–859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Public Health England. Dependence and withdrawal associated with some prescribed medicines. An evidence review. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/prescribed-medicines-review-report (2019, accessed 5 August 2019).

- 4. Royal College of Psychiatrists. Position statement on antidepressants and depression. London: Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Davies J, Read J. A systematic review into the incidence, severity and duration of antidepressant withdrawal effects: are guidelines evidence-based? Addict Behav 2019; 97: 111–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cosci F, Chouinard G. Acute and persistent withdrawal syndromes following discontinuation of psychotropic medications. Psychother Psychosom 2020; 89: 283–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fava GA, Gatti A, Belaise C, et al. Withdrawal symptoms after selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor discontinuation: a systematic review. Psychother Psychosom 2015; 84: 72–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fava GA, Benasi G, Lucente M, et al. Withdrawal symptoms after serotonin-noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor discontinuation: systematic review. Psychother Psychosom 2018; 87: 195–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rosenbaum JF, Fava M, Hoog SL, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor discontinuation syndrome: a randomized clinical trial. Biol Psychiatry 1998; 44: 77–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jauhar S, Hayes J. The war on antidepressants: what we can, and can’t conclude, from the systematic review of antidepressant withdrawal effects by Davies and Read. Addict Behav 2019; 97: 122–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jauhar S, Hayes J, Goodwin GM, et al. Antidepressants, withdrawal, and addiction; where are we now? J Psychopharmacol 2019; 33: 655–659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Read J, Williams J. Adverse effects of antidepressants reported by a large international cohort: emotional blunting, suicidality, and withdrawal effects. Curr Drug Saf 2018; 13: 176–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Weller I, Ashby D, Chambers M, et al. Report of the CSM expert working group on the safety of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressants. Oxford: MHRA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Johnson CF, Macdonald HJ, Atkinson P, et al. Reviewing long-term antidepressants can reduce drug burden: a prospective observational cohort study. Br J Gen Pract 2012; 62: e773–e779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Stockmann T, Odegbaro D, Timimi S, et al. SSRI and SNRI withdrawal symptoms reported on an internet forum. Int J Risk Saf Med 2018; 29: 175–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Davies J, Regina P, Montagu L. All-party parliamentary group for prescribed drug dependence. Antidepressant withdrawal: a survey of patients’ experience by the all-party parliamentary group for prescribed drug dependence. APPG, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 17. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Depression in adults: recognition and management. (NICE Guideline 90). London: NICE, 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Haddad PM, Anderson IM. Recognising and managing antidepressant discontinuation symptoms. Adv Psychiatr Treat 2007; 13: 447–457. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Young A, Haddad P. Discontinuation symptoms and psychotropic drugs control of meningococcal disease in West Africa. Lancet 2000; 355: 1184–1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hengartner MP. How effective are antidepressants for depression over the long term? A critical review of relapse prevention trials and the issue of withdrawal confounding. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol 2020; 10: 2045125320921694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. American Psychiatric Association. The diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Groot PC, van Os J. Antidepressant tapering strips to help people come off medication more safely. Psychosis 2018; 10: 142–145. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Haddad P, Devarajan S, Dursun S. Antidepressant discontinuation (withdrawal) symptoms presenting as ‘stroke’. J Psychopharmacol 2001; 15: 139–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Warner CH, Bobo W, Warner C, et al. Antidepressant discontinuation syndrome. Am Fam Physician 2006; 74: 449–456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Read J, Cartwright C, Gibson K. How many of 1829 antidepressant users report withdrawal effects or addiction? Int J Ment Health Nurs 2018; 27: 1805–1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Read J, Gee A, Diggle J, et al. Staying on, and coming off, antidepressants: the experiences of 752 UK adults. Addict Behav 2019; 88: 82–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Maund E, Dewar-Haggart R, Williams S, et al. Barriers and facilitators to discontinuing antidepressant use: a systematic review and thematic synthesis. J Affect Disord 2019; 245: 38–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bosman RC, Huijbregts KM, Verhaak PFFM, et al. Long-term antidepressant use: a qualitative study on perspectives of patients and GPs in primary care. Br J Gen Pract 2016; 66: e708–e719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. The Scottish Parliament. Scottish Parliamentary Petition PE01561: prescribed drug dependence and withdrawal, http://www.parliament.scot/GettingInvolved/Petitions/PE01651 (2017, accessed June 23, 2020).

- 30. Welsh Parliament. Welsh Parliamentary Petition - P-05-784: prescription drug dependence and withdrawal - recognition and support, https://business.senedd.wales/mgIssueHistoryHome.aspx?IId=19952 (2019, accessed June 23, 2020).

- 31. Carville S, Ashmore K, Cuyàs A, et al. Patients’ experience: review of the evidence on dependence, short term discontinuation and longer term withdrawal symptoms associated with prescribed medicines. https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/file/13705/download?token=F3JJ3PKJ. (2019, accessed 5 July 2020).

- 32. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006; 3: 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Westwood N, Moore MJ, Cooke M. Going lean in the NHS: how lean thinking will enable the NHS to get more out of the same resources. NHS Inst Innov Improv, https://www.england.nhs.uk/improvement-hub/wp-content/uploads/sites/44/2017/11/Going-Lean-in-the-NHS.pdf (2007, accessed 5 August 2019).

- 34. Read J, Gibson K, Cartwright C. Do GPs and psychiatrists recommend alternatives when prescribing anti-depressants? Psychiatry Res 2016; 246: 838–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hengartner MP. Methodological flaws, conflicts of interest, and scientific fallacies: Implications for the evaluation of antidepressants’ efficacy and harm. Front Psychiatry 2017; 8: 275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Goodwin GM, Nutt D. Antidepressants; what’s the beef? Acta Neuropsychiatr 2019; 31: 59–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lewis G, Duffy L, Ades A, et al. The clinical effectiveness of sertraline in primary care and the role of depression severity and duration (PANDA): a pragmatic, double-blind, placebo-controlled randomised trial. Lancet Psychiatry 2019; 6: 903–914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Fava GA. Rational use of antidepressant drugs. Psychother Psychosom 2014; 83: 197–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Jakobsen JC, Gluud C, Kirsch I. Should antidepressants be used for major depressive disorder? BMJ Evidence-Based Med 2020; 25: 130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Geddes JR, Carney SM, Davies C, et al. Relapse prevention with antidepressant drug treatment in depressive disorders: a systematic review. Lancet 2003; 361: 653–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Récalt AM, Cohen D. Withdrawal confounding in randomized controlled trials of antipsychotic, antidepressant, and stimulant drugs, 2000–2017. Psychother Psychosom 2019; 88: 105–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Middleton H, Moncrieff J. ‘They won’t do any harm and might do some good’: time to think again on the use of antidepressants? Br J Gen Pract 2011; 61: 47–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Warren JB. The trouble with antidepressants: why the evidence overplays benefits and underplays risks — an essay by John B Warren. BMJ. Epub ahead of print 3 September 2020. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.m3200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Moncrieff J. Against the stream: antidepressants are not antidepressants – an alternative approach to drug action and implications for the use of antidepressants. Psychiatrist 2018; 42: 42–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bet PM, Hugtenburg JG, Penninx BWJH, et al. Side effects of antidepressants during long-term use in a naturalistic setting. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2013; 23: 1443–1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Eveleigh R, Speckens A, van Weel C, et al. Patients’ attitudes to discontinuing not-indicated long-term antidepressant use: barriers and facilitators. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol 2019; 9: 204512531987234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Middleton DJ, Cameron IM, Reid IC. Continuity and monitoring of antidepressant therapy in a primary care setting. Qual Prim Care 2011; 19: 109–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Horowitz MA, Taylor D. Tapering of SSRI treatment to mitigate withdrawal symptoms. The Lancet Psychiatry 2019; 6: 538–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Read J, Renton J, Harrop C, et al. A survey of UK general practitioners about depression, antidepressants and withdrawal: implementing the 2019 Public Health England report. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol 2020; 10: 204512532095012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Bowers HM, Williams SJ, Geraghty AWA, et al. Helping people discontinue long-term antidepressants: views of health professionals in UK primary care. BMJ Open 2019; 9: 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Eveleigh R, Muskens E, Lucassen P, et al. Withdrawal of unnecessary antidepressant medication: a randomised controlled trial in primary care. BJGP Open 2017; 34: 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. NICE. Safe prescribing and withdrawal management of prescribed drugs associated with dependence and withdrawal, https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/indevelopment/gid-ng10141 (2019, accessed 6 November 2019).

- 53. Maund E, Stuart B, Moore M, et al. Managing antidepressant discontinuation: a systematic review. Ann Fam Med 2019; 17: 52–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Wentink C, Huijbers MJ, Lucassen PL, et al. Enhancing shared decision making about discontinuation of antidepressant medication: a concept-mapping study in primary and secondary mental health care. Br J Gen Pract 2019; 69: e777–e785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Groot PC, van Os J. Outcome of antidepressant drug discontinuation with taperingstrips after 1–5 years. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol 2020; 10: 204512532095460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Groot PC, van Os J. How user knowledge of psychotropic drug withdrawal resulted in the development of person-specific tapering medication. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol 2020; 10: 204512532093245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet 2018; 391: 1357–1366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Surviving antidepressants. https://www.survivingantidepressants.org/ (2018, accessed 10 October 2018).

- 59. The Withdrawal Project. https://withdrawal.theinnercompass.org/. (accessed 5 August 2019).

- 60. Cosci F, Chouinard G, Chouinard VA, et al. The diagnostic clinical interview for drug withdrawal 1 (DID-W1). New symptoms of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) or serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRI): Inter-rater reliability. Riv Psichiatr 2018; 53: 95–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Kocalevent R-D, Hinz A, Brähler E. Standardization of a screening instrument (PHQ-15) for somatization syndromes in the general population. BMC Psychiatry 2013; 13: 91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Pfizer. PHQ-15 physical symptoms, https://www.phqscreeners.com/images/sites/g/files/g10060481/f/201412/English_0 (1).pdf (accessed June 26, 2020).

- 63. Welsh Parliament. Written response by the Welsh government to the report of the petitions committee - petition P-05-784 prescription drug dependence and withdrawal – recognition and support, https://senedd.wales/laid documents/gen-ld12521/gen-ld12521-e.pdf (2020, accessed June 23, 2020).

- 64. Cosci F, Guidi J, Tomba E, et al. The emerging role of clinical pharmacopsychology. Clin Psychol Eur 2019; 1: 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 65. The Scottish Parliament. PE1517 - Polypropylene mesh medical devices, https://www.parliament.scot/GettingInvolved/Petitions/scottishmeshsurvivors (2018, accessed June 23, 2020).

- 66. Independent Medicines and Medical Devices Safety Review. First do no harm, https://immdsreview.org.uk/downloads/IMMDSReview_Web.pdf (2020, accessed 20 July 2020). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 67. Nielsen M, Hansen EH, Gotzsche PC. What is the difference between dependence and withdrawal reactions? A comparison of benzodiazepines and selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors. Addiction 2012; 107: 900–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, Figure_1 for The ‘patient voice’: patients who experience antidepressant withdrawal symptoms are often dismissed, or misdiagnosed with relapse, or a new medical condition by Anne Guy, Marion Brown, Stevie Lewis and Mark Horowitz in Therapeutic Advances in Psychopharmacology

Supplemental material, Figure_2 for The ‘patient voice’: patients who experience antidepressant withdrawal symptoms are often dismissed, or misdiagnosed with relapse, or a new medical condition by Anne Guy, Marion Brown, Stevie Lewis and Mark Horowitz in Therapeutic Advances in Psychopharmacology