Abstract

While it has been established that course-based undergraduate research experiences (CUREs) lead to student benefits, it is less clear what aspects of CUREs lead to such gains. In this study, we aimed to understand the effect of students analyzing their own data, compared with students analyzing data that had been collected by professional scientists. We compared the experiences of students in a CURE investigating whether the extinction risk status of terrestrial mammals and birds is associated with their ecological traits. Students in the CURE were randomly assigned to analyze either data that they had collected or data previously collected by professional scientists. All other aspects of the student experience were designed to be identical. We found that students who analyzed their own data showed significantly greater gains in scientific identity and emotional ownership than students who analyzed data collected by professional scientists.

INTRODUCTION

National calls to engage students in undergraduate research have resulted in a proliferation of course-based undergraduate research experiences, or CUREs (1–3). CUREs are learning experiences in which students conduct real research in the context of a formal course; this research needs to be both novel and broadly relevant, or important to others outside of the course, to be considered a CURE (4, 5). CUREs have emerged as a popular model to broaden the opportunities for students to participate in research (6) and are associated with an array of benefits for students that are similar to what they can achieve in independent research experiences in faculty labs (3, 7).

However, there is still much that we do not know about what components of CUREs lead to specific outcomes. Although there have been calls to use backward design when creating CUREs by first considering student learning outcomes and planning course activities that will lead to such outcomes (8), there have been few attempts at designing or assessing courses so that one can identify what specific elements of CUREs are important for a specific outcome (9). Key design elements of CUREs have been proposed to be scientific practices, collaboration, iteration, discovery, and broad relevance (4, 5). The few CURE studies that have assessed what elements of CUREs lead to specific outcomes have focused on the impact of these key design elements, with the most attention being paid to collaboration, iteration, discovery, and broad relevance (10–13). Researchers have likely focused on these specific key design elements because they can be measured by the Laboratory Course Assessment survey (14). However, given the myriad of decisions that CURE instructors make about how to implement a CURE (15), there is a need for additional research to help delineate how elements of CURE design can impact student outcomes.

While it is generally assumed that the scientific practices that students conduct in a CURE replicate the types of scientific practices that professional scientists use, there is much variation in terms of which scientific practices are implemented in a CURE. Some CUREs are designed so that students collect data and then analyze the data they collect (13, 16), while others focus on students analyzing a large dataset that was collected by someone else (17–19). Some CUREs include creating posters or disseminating the work through written artifacts (20). Additionally, in some CUREs, students work through most stages of a research project, meaning that they engage in an array of scientific practices including question development, data collection and analysis, and dissemination of findings (12, 21, 22). With the range of possible scientific practices that students can complete in a CURE, and the variations in how they can complete them, CURE developers have few insights into which scientific practices lead to which outcomes.

In this study, we set out to identify the impact of scientific practices on student outcomes. Specifically, we focused on the impact of students analyzing their own data versus their analyzing data that were collected by someone else, because it is an open question as to whether it is important for students to analyze their own data (10, 23). We assessed outcomes that we hypothesized may be influenced by students analyzing their own data, including scientific self-efficacy, scientific identity, and scientific community values, all of which have been shown to positively predict students’ interest in pursuing a science-related research career (24). We also predicted that analyzing one’s own data may positively affect students’ cognitive ownership or the degree to which students feel as though they have intellectual responsibility over their work, and emotional ownership, or the strength of students’ emotions toward their work (11, 25, 26). Finally, we examined whether analyzing one’s own data affected students’ interest in pursuing a career in science.

Study focus and context

This study was conducted in an upper-level evolution course that was taught in the fall semesters of 2018 and 2019 at a primarily undergraduate institution that is a rural, regional campus of a larger university system. This course, required for biology majors, was designed to both cover the fundamental principles of evolutionary biology and provide a research experience for all students in the biology major. A portion of this course was designed to be a CURE, where the students in the course engaged in conducting novel, broadly relevant scientific research (4). The CURE was performed over 12 weeks with 75 minutes of class time devoted to the CURE each week. The 2018 and 2019 iterations of the course were identical in that students engaged in the same research project, and both iterations were taught by the same instructor and teaching assistant. The instructor (M.L.K.) was an assistant professor, and the teaching assistant (M.J.M.) was a master’s degree student whose thesis research was on the same topic as the CURE. Data were pooled over both semesters to maximize the number of participants in the study.

Students in the CURE investigated whether the current extinction risk status of terrestrial mammals and birds is associated with the ecological traits they possess, as has been previously demonstrated for the marine vertebrates and molluscs that have been studied (27). Students worked with the same partner throughout the project on species that were included in the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List (28); the IUCN Red List is a systematic hierarchical classification system for the extinction risk status of species, from species of least concern to those that have already become extinct in historical times. This allowed students to test for associations between ecological traits and extinction risk status. Specifically, students collected the ecological data from entries in wildlife encyclopedias (29, 30), based on the concept of ecological modes of life (31). Ecological modes of life were defined by the combination of a species habitat association, mode of locomotion, and feeding mode. Students entered the data into a class-wide shared Google spreadsheet. These data that students collected are henceforth referred to as the “students’ own data.”

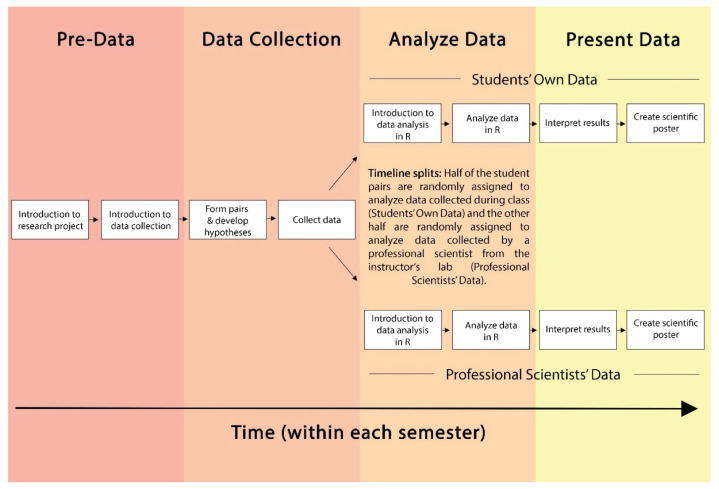

After the data collection phase, students were randomly assigned to one of two groups. In one group, students analyzed the data that the class as a whole collected as described above (students’ own data). In the other group, students analyzed data that was previously collected in an identical way on other terrestrial mammal and bird species by professional researchers in the research lab of the instructor (professional scientists’ data). Students in both conditions analyzed the data for possible associations between ecological traits and extinction risk status by logistic regression (in a general linear model) in the computer programming environment R (32). All student pairs presented a scientific poster at an end-of-the-semester research symposium, which was open to the greater university community. A representation of the progression of the CURE is illustrated in Figure 1. All other course design features were identical for the two groups. Students were told which condition they were randomly assigned to after the data collection phase of the project was completed. All phases of the research project were performed in the classroom and only required students to have access to a laptop computer.

FIGURE 1.

Timeline of activities for students in the CURE. All students engaged in the same scientific practices with one exception: students in one group analyzed the data they had collected (students’ own data) while students in the other group analyzed data collected by professional scientists (professional scientists’ data).

Our research questions were as follows:

To what extent do students in the CURE perceive they are conducting real scientific research? Are there differences between students who analyzed their own data and those who analyzed professional scientists’ data?

To what extent do students’ scientific self-efficacy, scientific identity, and scientific community values increase over the course of the CURE? If there are gains in any of these measures, to what extent do students who analyzed their own data show greater gains than students who analyzed professional scientists’ data?

To what extent does a student’s intent to pursue a career in science change over the course of the CURE? Compared with students who analyzed professional scientists’ data, are students who analyzed their own data more likely to want to pursue a career in science at the end of the semester?

To what extent did students who analyzed their own data develop more cognitive and emotional project ownership than students who analyzed professional scientists’ data?

METHODS

This study was conducted with approved IRB protocol IRB2018-00728.

Participants

We collected data from students enrolled in the CURE in fall 2018 and fall 2019. Twenty-six of the 29 students (92.9%) enrolled in the 2018 CURE and all 39 students enrolled in the 2019 CURE consented to participate in this study and were included in the data set. In total, 65 students in the CURE agreed to participate in the study.

Measures

Just prior to beginning the research project, students in the CURE were asked to complete an online pre-CURE survey in exchange for a small amount of extra credit. The survey consisted of a scientific self-efficacy scale, a scientific identity scale, a scientific community values scale, and a single item measuring the extent to which students plan to pursue a research-related science career.

During the final week of the course, students in the CURE were asked to complete an online post-CURE survey in exchange for a small amount of extra credit. The post-CURE survey consisted of the identical scales, comprised of identical questions, as the pre-CURE survey: a scientific self-efficacy scale, a scientific identity scale, a scientific community values scale, and a single item measuring the extent to which students plan to pursue a research-related science career. In addition, the post-CURE survey also included the Laboratory Class Assessment survey, a single item measuring the extent to which students perceived they were participating in scientific research during their lab course, the Project Ownership survey, and a list of demographic questions. We briefly describe each measure below. A more detailed description of each measure, the internal consistency, and the specific items can be found in the supplemental materials.

Scientific self-efficacy

A previously developed six-item scale (24) was used to measure students’ scientific self-efficacy or their perceptions of their abilities to perform different research-related tasks. The questions were identical to those used in the original paper.

Scientific identity

Students’ scientific identity was measured using a previously developed five-item scale (24). The questions were identical to those used in the original paper and asked students to report the extent to which they agreed with statements, which would indicate a strong scientific identity.

Scientific community values scale

Students’ scientific community objective values, or the extent to which students value objectives of the scientific community, were measured using a previously developed four-item scale (24). This scale asks students to rate their identification with four statements describing people who value objectives of the scientific community. The questions were identical to those used in the original paper.

Intent to pursue a scientific research career

Students’ intent to pursue a scientific research career was measured using a previously developed single item (24). The question, taken verbatim from the original paper, was rated on a Likert-type scale: “To what extent do you intend to pursue a science-related research career?”

The Laboratory Class Assessment survey

The Laboratory Class Assessment survey (LCAS) consists of three subscales to measure students’ perceptions of the extent to which they engaged in three design elements of biology lab courses: collaboration, iteration, and discovery/relevance (14). (i) Collaboration: The LCAS collaboration subscale consists of six items that evaluate the frequency with which students engage in collaboration-related activities, such as discussing work with other students. For all analyses, we used the five-item adapted collaboration scale to improve the internal consistency of the scale. (ii) Iteration: The LCAS iteration subscale consists of six items about the extent to which students have time to experience iterative processes, such as repeating or revising their work. (iii) Discovery/Relevance: The LCAS discovery/relevance subscale uses five items to measure students’ experiences of broadly relevant novel discoveries by asking students to rate the extent to which they agree that their work could lead to new discoveries and whether their data are of interest to the scientific community. All questions were taken verbatim from the original survey.

Perception of scientific research

We measured the extent to which students perceived they were engaging in scientific research in the context of the course using a previously developed question (13). The question defines scientific research for the students as the type of research that is done in faculty members’ labs and asked students to rate their agreement with the statement “I conducted scientific research in the Evolution course.” The question was taken verbatim from the original paper, with the exception that our question specified students’ “Evolution course.”

Project ownership

Students’ ownership of their research projects was measured using a 16-item survey developed by Hanauer and Dolan (26). The project ownership scale contains two subscales measuring cognitive ownership and emotional ownership (11, 26). (i) Cognitive ownership: Students’ cognitive ownership was measured using 10 items that ask students to what extent they agree that they had intellectual ownership of or responsibility for their lab work. (ii) Emotional ownership: Students’ emotional ownership was measured using six items that assess the strength of students’ emotion toward their lab work. The questions were taken verbatim from the original paper, with the exception that, for each question, we replaced “the laboratory course” with “the Evolution course.”

Demographic questions

Students completed a set of demographic questions about their gender, race/ethnicity, major, year in college, and prior research experience. Students’ demographics are reported in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Demographics of students in the CURE.

| Demographics | % (n) of Students with Response | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Students who analyzed scientists’ data (N=34) | Students who analyzed their own data (N=31) | |

| Gendera | ||

| Woman | 61.8 (21) | 58.1 (18) |

| Man | 35.3 (12) | 38.7 (12) |

| Other | 2.9 (1) | 0.0 (0) |

| Declined to state | 0.0 (0) | 3.2 (1) |

|

| ||

| Race/ethnicityb | ||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 2.9 (1) | 6.5 (2) |

| Asian | 35.3 (12) | 35.5 (11) |

| Black or African American | 2.9 (1) | 3.2 (1) |

| Latinx | 8.8 (3) | 3.2 (1) |

| Native Hawaiian | 8.8 (3) | 16.1 (5) |

| Pacific Islander | 0.0 (0) | 3.2 (1) |

| White | 35.3 (12) | 25.8 (8) |

| Other | 2.9 (1) | 3.2 (1) |

| Declined to state | 2.9 (1) | 3.2 (1) |

|

| ||

| Majorc | ||

| Anthropology | 2.9 (1) | 0.0 (0) |

| Biology | 85.3 (29) | 90.3 (28) |

| Environmental studies | 5.9 (2) | 6.5 (2) |

| Kinesiology | 5.9 (2) | 0.0 (0) |

| Declined to state | 0.0 (0) | 3.2 (1) |

|

| ||

| Year in college | ||

| Junior | 29.4 (10) | 32.3 (10) |

| Senior | 70.6 (24) | 67.7 (21) |

|

| ||

| Prior research experience | ||

| No | 47.1 (16) | 58.1 (18) |

| Yes | 52.9 (18) | 41.9 (13) |

In all analyses, we only included students who identified as men or women. While we recognize that gender is not binary, there were too few students who identified as a gender other than man or woman to analyze a third category.

In all analyses, we collapsed students who identify as Black or African American, Hispanic, Latino/a or of Spanish Origin, Pacific Islander, and American Indian or Alaska Native into one category, which we call BLPA students. These students share the experience of being underserved by institutions of higher education; we recognize that the experiences of these students are different, but the small sample sizes necessitated that we pool these identities as a single factor in our analyses.

In all analyses, we collapsed students into “biology” or “not biology” majors. We predicted that students’ self-efficacy or science identity in a biology course may be affected by whether they were biology majors or not, and it was necessary to pool non-biology majors because of small sample sizes.

Data analysis

To what extent do students in the CURE perceive they are conducting real scientific research? Are there differences in perceptions between students who analyzed their own data and those who analyzed professional scientists’ data?

Collaboration, iteration, and discovery/relevance are hypothesized to be key features of CUREs (4). We conducted independent samples t tests to compare scores on these subscales between students who analyzed their own data and students who analyzed professional scientists’ data; we also conducted independent samples t tests to compare ratings of the extent to which students perceived they were conducting research in their evolution course. Additionally, we used a linear regression model to compare the ratings of the extent to which students perceived they were conducting real research between students who analyzed their own data and students who analyzed professional scientists’ data, controlling for whether a student had previously participated in an undergraduate research experience in a faculty member’s lab (Y/N), (model: scientific.research ~ data.analyzed + prior.research). We did not include demographic variables, including gender or race/ethnicity, in this model testing whether there are differences in students’ perceptions of whether they were conducting real research because we have no reason to believe that demographics influence students’ perceptions of whether they are conducting scientific research.

To what extent do students’ self-efficacy, science identity, and scientific community values increase over the course of the CURE? Do students who analyzed their own data show greater gains than students who analyzed professional scientists’ data?

We conducted paired sample t tests to compare students’ scores on the self-efficacy, science identity, and scientific community values scales from the beginning and end of the CURE. We used linear regression models to test for whether there were differences in pre/post gains in these scores between students who analyzed their own data and students who analyzed professional scientists’ data. In each model, we included student demographics and our outcome variable was students’ post-scores. Specifically, we controlled for students’ pre-score, students’ major (biology/non-biology), whether they had prior research experience (yes/no), their gender (man/woman), and their race/ethnicity (white/Asian/BLPA) (model: post-score ~ type.of.data + pre.score + major + prior.reseach + gender + race.ethnicity). We recognize that not all students identify as gender binary (man or woman) (33); however, there were too few students who identified as non–gender binary to include this category in the analysis. We grouped students who identified as Black, Latinx, Pacific Islander, and American Indian or Alaska Native into one category (BLPA). These students share the experience of being underserved by institutions of higher education; we recognize that the experiences of these students are different, but the small sample sizes necessitated that we pool these identities as a single factor in our analyses.

To what extent do students’ intents to pursue a career in science change over the course of the CURE? Are students who analyzed their own data more likely to want to pursue a career in science at the end of the semester?

At the beginning and end of the semester, students reported their intent to pursue a science-related research career. We used linear regression models to assess whether there were differences in the extent of this intent at the end of the semester between students who analyzed their own data and students who analyzed professional scientists’ data. Students’ post- score was the outcome variable, and in the model, we controlled for students’ intention to pursue a career in scientific research at the beginning of the semester, as well as for their self-efficacy, science identity, and scientific community value scores at the end of the semester (model: pursue.science.post ~ type.of.data + pursue.science.pre + self.efficacy.post + science.identity.post + community.values.post). We ran a second model where we controlled for students’ major, whether they had prior research experience, gender, and race/ethnicity (model: post- score ~ type.of.data + pre.score + major + prior.research + gender + race.ethnicity).

To what extent did students who analyzed their own data develop more cognitive and emotional project ownership than students who did not?

At the end of the semester, students completed the cognitive and emotional ownership scales. We used a linear regression model to test whether there were differences in cognitive and emotional ownership between students who analyzed their own data and students who analyzed professional scientists’ data. In each model, either students’ cognitive or emotional ownership was the outcome variable, and we controlled for students’ collaboration, iteration, and discovery/relevance subscores, since these have been shown to predict student cognitive and emotional ownership (11, 13) (e.g., model: cognitive.ownership ~ type.of.data + collaboration + iteration + discovery.relevance). We ran a second set of models controlling for student major, prior research experience, gender, and race/ethnicity (e.g., model: cognitive.ownership ~ type.of.data + major + prior.research + gender + race.ethnicity).

RESULTS

There was no statistical difference in the extent to which students who analyzed their own data and students who analyzed professional scientists’ data perceived they were conducting real research

We found no significant differences in students’ perceptions of collaboration, iteration, or discovery/relevance between students who analyzed their own data and students who analyzed professional scientists’ data (Table 2). Additionally, there was no significant difference in the extent to which students perceived they were conducting real research between students who analyzed their own data and students who analyzed professional scientists’ data (Table 2). There was also no difference when we controlled for whether a student had previously participated in an undergraduate research experience (see the Supplemental Materials for the results of this regression).

TABLE 2.

Student scores on the LCAS collaboration, iteration, and discovery/relevance subscales and student perceptions that they conducted real researcha.

| Outcome | Response (mean ± SD) among students who: | t | p | Cohen’s d | Possible range of scores | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analyzed scientists’ data | Analyzed their own data | |||||

| Collaboration subscale | 18.5 ± 2.2 | 19.2 ± 1.8 | −1.5 | 0.14 | −0.4 | 5–20 |

| Iteration subscale | 31.5 ± 4.0 | 32.0 ± 3.3 | −0.5 | 0.61 | −0.1 | 6–36 |

| Discovery/relevance subscale | 26.3 ± 3.8 | 26.9 ± 3.0 | −0.8 | 0.46 | −0.2 | 5–30 |

| Conducting real research | 8.4 ± 1.9 | 8.8 ± 1.7 | −0.9 | 0.40 | −0.2 | 1–10 |

The five-item collaboration scale measures how often students engage in collaborative activities in lab using four response options ranging from never (1) to weekly (4). The six-item iteration scale and five-item discovery/relevance scale measure the extent to which students agree that they experience these elements, with six response options ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (6). The extent to which students perceived they conducted real research was measured using one item, with responses ranging from (1) strongly disagree to (10) strongly agree.

Students’ scientific self-efficacy and scientific identity significantly increased over the course of the CURE, and students who analyzed their own data showed greater gains in science identity

Over the semester, all students’ scientific identity and self-efficacy increased significantly (Table 3). There was no significant change in students’ scientific community values.

TABLE 3.

All students’ scientific self-efficacy, identity, and community values scores, measured at the beginning and end of the CUREa.

| Outcome | Pre-CURE score (mean ± SD) | Post-CURE score (mean ± SD) | t | p | Cohen’s d | Possible range of scores |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scientific self-efficacy | 21.1 ± 3.7 | 24.5 ± 4.1 | −8.1 | <0.0001 | −0.9 | 6–30 |

| Scientific identity | 18.2 ± 3.9 | 20.1 ± 3.8 | −4.8 | <0.0001 | −0.5 | 5–25 |

| Scientific community values | 20.6 ± 3.0 | 21.0 ± 3.2 | −1.3 | 0.20 | −0.1 | 4–24 |

Students’ scientific self-efficacy and identity significantly increased over the course of the CURE. However, students’ scientific community values did not significantly change. The six-item scientific self-efficacy scale measures students’ confidence in their ability to perform scientific tasks from (1) not confident at all to (5) absolutely confident. The five-item scientific identity scale measures students’ agreement with statements about science identity using a scale ranging from (1) strongly disagree to (5) strongly agree. The four-item scientific community values scale measures whether students perceive themselves to be like people who value objectives of the scientific community, using a scale ranging from (1) not like me at all to (6) very much like me.

Students who analyzed their own data were no more likely to show gains in scientific self-efficacy than students who analyzed professional scientists’ data. However, BLPA students were more likely to show gains in scientific self-efficacy than white students (Table 4). We did find that students who analyzed their own data were more likely to show gains in scientific identity than students who analyzed professional scientists’ data (Table 4). There were no demographic differences with regard to gains in student scientific identity.

TABLE 4.

Summary of linear regression models exploring the relationship between the type of data students analyzed and their post-CURE scientific self-efficacy and scientific identify scores, controlling for students’ pre-CURE scores and demographicsa.

| Variable | Model A: Self-Efficacy | Model B: Science Identity | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE B | β | p | B | SE B | β | p | |

| Intercept | 8.8 | 2.9 | <0.01 | 9.5 | 2.4 | <0.001 | ||

| Type of data analyzed (own) | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.1 | 0.56 | 1.6 | 0.8 | 0.2 | <0.05 |

| Pre-CURE score | 0.8 | 0.1 | 0.7 | <0.0001 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.6 | <0.001 |

| Major (other) | −1.7 | 1.4 | −0.1 | 0.22 | −1.1 | 1.3 | −0.1 | 0.43 |

| Prior research (yes) | −0.6 | 0.9 | −0.1 | 0.51 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 0.3 | 0.80 |

| Gender (woman) | −1.3 | 0.9 | −0.2 | 0.14 | −0.7 | 0.8 | −0.1 | 0.38 |

| Race/ethnicity (Asian) | 0.2 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.83 | −0.7 | 1.0 | −0.1 | 0.50 |

| Race/ethnicity (BLPA) | 2.1 | 1.0 | 0.2 | 0.05 | −0.6 | 1.0 | −0.1 | 0.57 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.43 | 0.39 | ||||||

B represents unstandardized coefficients and β represents standardized coefficients. Focus categories are provided in parentheses in column 1.

Students’ intentions to pursue a career in scientific research did not statistically change over the course of the semester, and there was no statistical difference between the intentions of students who analyzed their own data and those of students who analyzed professional scientists’ data

Controlling for students’ intention to pursue a career in scientific research at the beginning of the semester, as well as for their scientific self-efficacy, identity, and community value scores at the end of the semester, there was no significant difference in students’ intentions to pursue a career in research at the end of the CURE between students who analyzed their own data and students who did not (Table 5). However, students’ scientific identity significantly predicted their intent to pursue a science-related research career. There was also no difference between the intent of students who analyzed their own data and students who analyzed professional scientists’ data when we controlled for students’ major, prior research experience, gender, and race/ethnicity. The mean intent to pursue a career in scientific research from the pre- and post-survey for each group is presented in Table 6. The results from this regression are reported in the Supplemental Materials.

TABLE 5.

Summary of linear regression model exploring the relationship between the type of data students analyzed and their post-CURE intent to pursue a science-related research careera.

| Variable | Pursue a career in science | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE B | β | p | |

| Intercept | 0.3 | 1.9 | 0.87 | |

| Type of data analyzed (own) | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.49 |

| Intention to pursue research career pre-CURE | 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.6 | <0.001 |

| Scientific self-efficacy post- score | −0.0 | 0.1 | −0.0 | 0.93 |

| Scientific identity post- score | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.02 |

| Scientific community values post- score | −0.1 | 0.1 | −0.1 | 0.28 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.52 | |||

B represents unstandardized coefficients and β represents standardized coefficients. In the analysis we controlled for students’ pre-CURE intent as well as their scientific self-efficacy, scientific identity, and scientific community value scores. Focus categories are shown in parentheses in column 1.

TABLE 6.

Intent to pursue research score and cognitive and emotional ownership scores of students who analyzed professional scientists’ data and students who analyzed their own dataa.

| Pre-CURE score (mean ± SD) among students who analyzed: | Post-CURE (mean ± SD) among students who analyzed: | Possible range of scores | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| Outcome | Scientists’ data | Their own data | Scientists’ data | Their own data | |

| Intent to pursue a research career | 5.7 ± 2.6 | 5.9 ± 3.1 | 5.7 ± 2.7 | 6.4 ± 2.6 | 1–10 |

| Cognitive ownership | — | — | 41.4 ± 6.0 | 43.2 ± 4.8 | 10–50 |

| Emotional ownership | — | — | 21.5 ± 4.5 | 24.3 ± 3.9 | 6–30 |

Students’ intent to pursue a research career was measured on the pre- and post-CURE survey with one item with 10 response options ranging from definitely will not (1) to definitely will (10). Cognitive ownership was measured on the post-CURE survey using 10 items with five response options ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). Emotional ownership was measured on the post-CURE survey using six items with five response options ranging from very slightly (1) to very strongly (5).

Students who analyzed their own data developed greater emotional ownership than students who analyzed professional scientists’ data

Controlling for the extent to which students experienced collaboration, iteration, and discovery/relevance, as well as students’ major and whether they had prior research experience, we found that students who analyzed their own data were more likely to have higher emotional project ownership than students who analyzed professional scientists’ data (Table 7). However, there was no difference in students’ cognitive ownership. We also identified that students’ scores on the discovery/relevance subscale significantly predicted both their emotional and cognitive ownership and students’ scores on the iteration subscale predicted their cognitive ownership. We ran a second model controlling for students’ major, prior research experience, gender, and race/ethnicity and found the same results; students who analyzed their own data demonstrated higher emotional ownership but not cognitive ownership than students who analyzed professional scientists’ data. The mean cognitive and emotional ownership score for each group is presented in Table 6. The results of this regression are reported in the Supplemental Materials.

TABLE 7.

Summary of linear regression model exploring the relationship between the type of data students analyzed and their emotional and cognitive ownership, controlling for students’ collaboration, iteration, and discovery/relevance scoresa.

| Variable | Model A: Emotional ownership | Model B: Cognitive ownership | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE B | β | p | B | SE B | β | p | |

| Intercept | −0.9 | 5.2 | 0.86 | 5.7 | 5.4 | 0.29 | ||

| Type of data analyzed (own) | 2.2 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 0.03 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 0.33 |

| Collaboration | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.14 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.78 |

| Iteration | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.41 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.05 |

| Discovery | 0.41 | 0.15 | 0.3 | <0.01 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 0.6 | <0.0001 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.29 | 0.50 | ||||||

B represents unstandardized coefficients and β represents standardized coefficients. Focus categories are shown in parentheses in column 1.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we assessed the impact of students analyzing their own data versus analyzing data that professional scientists collected. We created the CURE so that the experiences of students in the two groups were designed to be identical with the exception of which data they analyzed. Indeed, we found that students in both groups perceived they engaged in similar levels of collaboration, iteration, and discovery/relevance, three key design elements of CUREs (4). We hypothesized that students who analyzed their own data may be more likely to perceive that they conducted real scientific research because students sometimes perceive research to be inauthentic if others are doing an aspect of their project or if they do not see all the steps of the research process in a linear way (13). However, we found this was not true in this study. Both groups of students in our study collected data, despite one group then analyzing data that was collected by professional scientists. Since students who analyzed professional scientists’ data still went through the process of collecting data and were aware that their data were analyzed by the other group of students, this may have bolstered their sense that they were doing scientific research. Further investigations would need to be conducted to understand how analyzing data collected by others without being involved at all in data collection affects students’ perceptions that they are doing authentic research.

CUREs have been hypothesized to lead to increased student scientific identity (25, 34, 35). Additionally, CUREs have been shown to improve student research self-efficacy or students’ perceptions of their ability to perform research-related tasks (18, 19, 36). On average, students in the CURE that we studied showed gains in both self-efficacy and scientific identity. However, students who analyzed their own data showed a significantly greater gain in scientific identity than students who analyzed scientists’ data. Researchers have hypothesized that gains in scientific identity in CUREs could be due to a sense of belonging to the larger scientific community as they receive validation from the community (37), or because of an increased tolerance for obstacles and recognizing one’s scientific disposition (12, 35, 38–40). It is possible that students who analyzed their own data felt more confident in the data that they collected because they were able to analyze it, which could contribute to their positive thoughts about themselves as a scientist.

In addition to scientific identity, we also identified that, compared with students who analyzed professional scientists’ data, students who analyzed their own data showed greater gains in emotional ownership or the strength of students’ emotions towards their work (11, 25, 26). It has been well established that mere exposure can enhance familiarity and that familiarity leads to liking, and in some cases, happiness as well (41–43). We suspect that students who analyzed their own data may have felt more emotional ownership toward the overall research project because they were more familiar with their own dataset that they collected. However, these hypotheses need to be further explored in future research.

CONCLUSION

In this study, we examined the impact of students in a CURE analyzing data they collected versus analyzing data collected by professional scientists. We found that students who analyzed their own data showed greater gains in scientific identity and emotional ownership than their counterparts who analyzed data collected by professional scientists. This study highlights the importance of students analyzing their own data in CUREs.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the CURE students for participating in the study and the ASU Biology Education Research lab for their feedback on earlier versions of the manuscript. This work was supported by the U.S. National Science Foundation under grant 1345247 to M.L.K. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Footnotes

Supplemental materials available at http://asmscience.org/jmbe

REFERENCES

- 1.American Association for the Advancement of Science. Vision and change in undergraduate biology education: a call to action. 2011. 2010. [Online.] http://www.visionandchange.org/VC_report.pdf.

- 2.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Integrating discovery-based research into the undergraduate curriculum: report of a convocation. The National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Undergraduate research experiences for STEM students: successes, challenges, and opportunities. The National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Auchincloss LC, Laursen SL, Branchaw JL, Eagan K, Graham M, Hanauer DI, Lawrie G, McLinn CM, Pelaez N, Rowland S. Assessment of course-based undergraduate research experiences: a meeting report. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2014;13:29–40. doi: 10.1187/cbe.14-01-0004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brownell SE, Kloser MJ. Toward a conceptual framework for measuring the effectiveness of course-based undergraduate research experiences in undergraduate biology. Stud Higher Educ. 2015;40:525–544. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2015.1004234. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bangera G, Brownell SE. Course-based undergraduate research experiences can make scientific research more inclusive. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2014;13:602–606. doi: 10.1187/cbe.14-06-0099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Linn MC, Palmer E, Baranger A, Gerard E, Stone E. Undergraduate research experiences: impacts and opportunities. Science. 2015;347:1261757. doi: 10.1126/science.1261757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cooper KM, Soneral PA, Brownell SE. Define your goals before you design a CURE: a call to use backward design in planning course-based undergraduate research experiences. J Microbiol Biol Educ. 2017;18(2) doi: 10.1128/jmbe.v18i2.1287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shortlidge EE, Brownell SE. How to assess your CURE: a practical guide for instructors of course-based undergraduate research experiences. J Microbiol Biol Educ. 2016;17:399. doi: 10.1128/jmbe.v17i3.1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ballen CJ, Thompson SK, Blum JE, Newstrom NP, Cotner S. Discovery and broad relevance may be insignificant components of course-based undergraduate research experiences (CUREs) for non-biology majors. J Microbiol Biol Educ. 2018;19(2) doi: 10.1128/jmbe.v19i2.1515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corwin LA, Runyon CR, Ghanem E, Sandy M, Clark G, Palmer GC, Reichler S, Rodenbusch SE, Dolan EL. Effects of discovery, iteration, and collaboration in laboratory courses on undergraduates’ research career intentions fully mediated by student ownership. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2018;17:ar20. doi: 10.1187/cbe.17-07-0141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gin LE, Rowland AA, Steinwand B, Bruno J, Corwin LA. Students who fail to achieve predefined research goals may still experience many positive outcomes as a result of CURE participation. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2018;17:ar57. doi: 10.1187/cbe.18-03-0036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cooper KM, Blattman JN, Hendrix T, Brownell SE. The impact of broadly relevant novel discoveries on student project ownership in a traditional lab course turned CURE. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2019;18(4):ar57. doi: 10.1187/cbe.19-06-0113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Corwin LA, Runyon C, Robinson A, Dolan EL. The laboratory course assessment survey: a tool to measure three dimensions of research-course design. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2015;14:ar37. doi: 10.1187/cbe.15-03-0073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shortlidge EE, Bangera G, Brownell SE. Each to their own CURE: faculty who teach course-based undergraduate research experiences report why you too should teach a CURE. J Microbiol Biol Educ. 2017;18(2) doi: 10.1128/jmbe.v18i2.1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brownell SE, Hekmat-Scafe DS, Singla V, Seawell PC, Imam JFC, Eddy SL, Stearns T, Cyert MS. A high-enrollment course-based undergraduate research experience improves student conceptions of scientific thinking and ability to interpret data. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2015;14:ar21. doi: 10.1187/cbe.14-05-0092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lopatto D. Undergraduate research experiences support science career decisions and active learning. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2007;6:297–306. doi: 10.1187/cbe.07-06-0039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shaffer CD, Alvarez C, Bailey C, Barnard D, Bhalla S, Chandrasekaran C, Chandrasekaran V, Chung H-M, Dorer DR, Du C. The genomics education partnership: successful integration of research into laboratory classes at a diverse group of undergraduate institutions. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2010;9:55–69. doi: 10.1187/09-11-0087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kloser MJ, Brownell SE, Shavelson RJ, Fukami T. Effects of a research-based ecology lab course: a study of nonvolunteer achievement, self-confidence, and perception of lab course purpose. J Coll Sci Teach. 2013;42:72–81. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kerr MA, Yan F. Incorporating course-based undergraduate research experiences into analytical chemistry laboratory curricula. J Chem Educ. 2016;93:658–662. doi: 10.1021/acs.jchemed.5b00547. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cooper KM, Hendrix T, Stephens MD, Cala JM, Mahrer K, Krieg A, Agloro ACM, Badini GV, Barnes ME, Eledge B, Jones R, Lemon EC, Massimo N, Martin A, Ruberto T, Simonson K, Webb EA, Weaver J, Zheng Y, Brownell SE. To be funny or not to be funny: gender differences in student perceptions of instructor humor in college science courses. PLOS One. 2018;13:e0201258. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0201258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cooper KM, Gin LE, Akeeh B, Clark CE, Hunter JS, Roderick TB, Elliott DB, Gutierrez LA, Mello RM, Pfeiffer LD, Scott RA, Arellano D, Ramirez D, Valdez E, Vargas C, Velarde K, Zheng Y, Brownell SE. Factors that predict life sciences student persistence in undergraduate research experiences. PLOS One. 2019;14 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0220186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wooten MM, Coble K, Puckett AW, Rector T. Investigating introductory astronomy students’ perceived impacts from participation in course-based undergraduate research experiences. Phys Rev Phys Educ Res. 2018;14:010151. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevPhysEducRes.14.010151. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Estrada M, Woodcock A, Hernandez PR, Schultz PW. Toward a model of social influence that explains minority student integration into the scientific community. J Educ Psychol. 2011;103:206. doi: 10.1037/a0020743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hanauer DI, Frederick J, Fotinakes B, Strobel SA. Linguistic analysis of project ownership for undergraduate research experiences. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2012;11:378–385. doi: 10.1187/cbe.12-04-0043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hanauer DI, Dolan EL. The project ownership survey: measuring differences in scientific inquiry experiences. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2014;13:149–158. doi: 10.1187/cbe.13-06-0123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Payne JL, Bush AM, Heim NA, Knope ML, McCauley DJ. Ecological selectivity of the emerging mass extinction in the oceans. Science. 2016;353:1284–1286. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf2416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.International Union for Conservation of Nature. The IUCN red list of threatened species. Version 2018–2. International Union for Conservation of Nature; Gland, Switzerland: 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hutchins M, Jackson JA, Bock WJ, Olendorf D. Grzimek’s animal life encyclopedia: birds. 2nd ed. Gale Group; Farmington Hills, MI: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hutchins M, Kleiman DG, Geist V, McDade MC. Grzimek’s animal life encyclopedia: mammals. 2nd ed. Gale Group; Farmington Hills, MI: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bambach RK, Bush AM, Erwin DH. Autecology and the filling of ecospace: key metazoan radiations. Palaeontology. 2007;50:1–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-4983.2006.00611.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2018. http://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cooper KM, Auerbach AJJ, Bader JD, Beadles-Bohling AS, Brashears JA, Cline E, Eddy SL, Elliott DB, Farley E, Fuselier L. Fourteen recommendations to create a more inclusive environment for LGBTQ+ individuals in academic biology. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2020;19:es6. doi: 10.1187/cbe.20-04-0062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alkaher I, Dolan EL. Integrating research into undergraduate courses. In: Sunal D, Sunal C, Wright E, Mason C, Zollman D, editors. Research-based undergraduate science teaching. Information Age Publishing; Charlotte, NC: 2014. pp. 403–434. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Corwin LA, Graham MJ, Dolan EL. Modeling course-based undergraduate research experiences: an agenda for future research and evaluation. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2015;14:es1. doi: 10.1187/cbe.14-10-0167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shaffer CD, Alvarez CJ, Bednarski AE, Dunbar D, Goodman AL, Reinke C, Rosenwald AG, Wolyniak MJ, Bailey C, Barnard D. A course-based research experience: how benefits change with increased investment in instructional time. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2014;13:111–130. doi: 10.1187/cbe-13-08-0152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lave J, Wenger E. Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1991. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seymour E, Hunter AB, Laursen SL, DeAntoni T. Establishing the benefits of research experiences for undergraduates in the sciences: first findings from a three-year study. Sci Educ. 2004;88:493–534. doi: 10.1002/sce.10131. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thiry H, Laursen SL. The role of student-advisor interactions in apprenticing undergraduate researchers into a scientific community of practice. J Sci Educ Technol. 2011;20:771–784. doi: 10.1007/s10956-010-9271-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thiry H, Weston TJ, Laursen SL, Hunter AB. The benefits of multi-year research experiences: differences in novice and experienced students’ reported gains from undergraduate research. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2012;11:260–272. doi: 10.1187/cbe.11-11-0098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Whittlesea BW, Price JR. Implicit/explicit memory versus analytic/nonanalytic processing: rethinking the mere exposure effect. Memory Cogn. 2001;29:234–246. doi: 10.3758/BF03194917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Titsworth BS. The effects of teacher immediacy, use of organizational lecture cues, and students’ notetaking on cognitive learning. Commun Educ. 2001;50:283–297. doi: 10.1080/03634520109379256. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.De Vries M, Holland RW, Chenier T, Starr MJ, Winkielman P. Happiness cools the warm glow of familiarity: psychophysiological evidence that mood modulates the familiarity–affect link. Psychol Sci. 2010;21:321–328. doi: 10.1177/0956797609359878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.