Programmable artificial cilia arrays enable metachronal coordination for enhanced fluid pumping at the low Reynolds number regime.

Abstract

Coordinated nonreciprocal dynamics in biological cilia is essential to many living systems, where the emergentmetachronal waves of cilia have been hypothesized to enhance net fluid flows at low Reynolds numbers (Re). Experimental investigation of this hypothesis is critical but remains challenging. Here, we report soft miniature devices with both ciliary nonreciprocal motion and metachronal coordination and use them to investigate the quantitative relationship between metachronal coordination and the induced fluid flow. We found that only antiplectic metachronal waves with specific wave vectors could enhance fluid flows compared with the synchronized case. These findings further enable various bioinspired cilia arrays with unique functionalities of pumping and mixing viscous synthetic and biological complex fluids at low Re. Our design method and developed soft miniature devices provide unprecedented opportunities for studying ciliary biomechanics and creating cilia-inspired wireless microfluidic pumping, object manipulation and lab- and organ-on-a-chip devices, mobile microrobots, and bioengineering systems.

INTRODUCTION

Cilia broadly exist in a wide range of organisms on the micrometer scale and can induce notable net fluid flows at very low Reynolds number (Re; ~0.001 to 0.01). Their ability of producing net fluid flows plays an essential role in many living systems, such as the self-propulsion of Paramecium (1); inducing vortical fluid flows for enhancing the feeding function in coral reefs (2); and pumping biofluids in the respiratory (3), brain ventricle (4), and reproductive systems (5) in the human body. In addition to the nonreciprocal dynamics of a single cilium, metachronal coordination of cilia arrays is another fascinating behavior of cilia observed in various biological systems (6–9), which has been hypothesized to be critical to enhance net fluid flows (10–15). However, experimental validation is still missing, and the fundamental relationship between metachronal coordination and the induced fluid flow has not yet been resolved. This is because biological ciliary systems are not fully viable for controlled experiments, limiting the flexibility of investigating biological hypotheses.

One promising solution is to use small-scale soft devices with programmable motions (16–20) as a bioinspired platform to model and study their biological counterparts by more controlled experiments at a larger length scale while keeping the essential nondimensional parameters (e.g., Re) the same (21–23). These bioinspired soft devices can also enable unprecedented microfluidic functionalities for lab-on-a-chip (24, 25) and other bioengineering applications (26). So far, many small-scale artificial cilia (27–33) have been proposed for emulating motions produced by biological cilia arrays. However, at small-length scales, designing and controlling both the complex individual ciliary motion and the overall coordinated dynamics within collective artificial cilia arrays pose an enormous conceptual challenge. Metachronal coordination has been mostly investigated in numerical studies (10–15, 27). For example, Khaderi et al. (27) did not experimentally create metachronal waves in artificial cilia, but numerically studied metachronal waves and experimentally demonstrated pumping water by a paramagnetic artificial cilia array with synchronized motions. This may be due to the challenge of controlling locally distributed magnetic fields at small scales. Recent works have proposed several ways to experimentally create metachronal coordination including using the length-dependent buckling motions of paramagnetic sheets (30) and magnetic anisotropy in paramagnetic rods (31) or ferromagnetic rod arrays (33). However, these existing works have focused on the fabrication methods and only demonstrated simple fluid pumping with non-optimized designs. In contrast, we developed design and fabrication methodologies to encode different nonreciprocal kinematics profiles into single-cilium motions and arbitrary phase shifts in a cilia array, even with two-dimensional (2D) metachronal waves and on curved surfaces like their biological counterparts. Moreover, we can optimize both the single-cilium dynamics and cilia array coordination independently to achieve the highest pumping performance by artificial cilia arrays with optimal metachronal coordination. We systematically investigate the quantitative relationship between metachronal waves and their induced fluid flows. These findings also enable us to create cilia-inspired fluidic soft devices with unique capabilities of pumping and mixing viscous synthetic and biological fluids at low Re. For example, we can pump even viscous syrup, synthetic mucus, and mouse blood in narrow channels.

RESULTS

Design artificial cilia arrays with programmable nonreciprocal motion and metachronal coordination

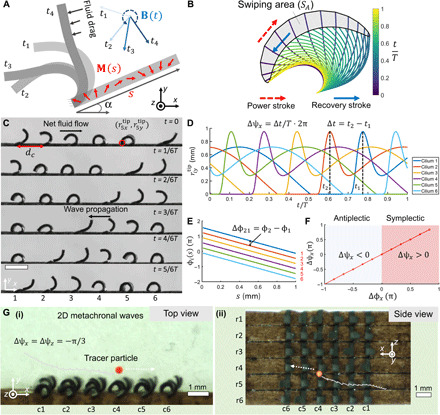

Here, we present a class of soft miniature devices consisting of multiple submillimeter-scale ferromagnetic-elastic sheets [see fig. S1 (A to C) and the “Fabrication of ferromagnetic cilia,” “Simultaneous encoding of cilia magnetization profiles,” and “Assembly of artificial cilia arrays” sections in Materials and Methods] with identical geometries and nonidentical magnetization profiles. Figure 1 and movie S1 show that these magnetically actuated artificial cilia arrays are capable of creating both programmable nonreciprocal cilia motion and collective metachronal coordination. The complex nonreciprocal oscillating dynamics of a ferromagnetic-elastic sheet (referred as “cilium” later on) in viscous fluids emerges from the nonlinear relations between internal macroscopic elastic stress, hydrodynamic forces, and exerted external magnetic torques at low Re, which emulates the regulation of molecular motors in a real cilium. By proper design of the material elastic properties and individual cilium magnetization profiles M(s) (s, material coordinate) as well as the time-varying external actuation magnetic field B(t) (t, time), ferromagnetic-elastic cilia arrays can produce complex but still deterministic ciliary dynamics (Fig. 1A). In particular, with an encoded M(s) and a rotating B(t) (see fig. S2 and the “Magnetic actuation of ferromagnetic cilia” section in Materials and Methods for creating such a magnetic field), complex nonlinear oscillations emerge from a rotational buckling instability (30) when a cilium undergoes a so-called phase-locking motion (14) until it reaches a critical deformed state (t/T, 0.3 to 1; T, beating cycle; Fig. 1B) and then rapidly snaps back in the reverse direction (t/T, 0 to 0.3; Fig. 1B). This buckling-based motion with two strokes i.e., the power and recovery strokes, results in a nonzero swiping area , which is the contour area (the gray area in Fig. 1B) of a single cilium’s tip trajectory rtip. Specifically, Fig. 1B illustrates a cilium dynamics with a positive swiping area by programming a specific M(s). Please note that the net fluid flow is independent of the timing of cilium motion at low Re but rather depends on the trajectory of an artificial cilium (8).

Fig. 1. Artificial magnetic cilia with programmable nonreciprocal motions and metachronal waves.

(A) Schematics of 2D rotational buckling motion of a ferromagnetic-elastic cilium (sheet). M(s), cilium magnetization profile; B(t), external rotating magnetic field; s ∈ [0, L], material coordinate in the cilium length direction (L = 1 mm); α, cilium initial body angle. (B) Illustration of ciliary nonreciprocal dynamics obtained by numerical simulation. SA represents the swiping area of the cilium tip within a beating cycle T. (C) Video snapshots of an artificial cilia array with metachronal waves pumping viscous fluids (glycerol). B(t): frequency f = 1 Hz and magnitude Bm = 38 mT. (D) Illustration of metachronal waves by the shifts in (i = 1 to 6) obtained by numerical simulation. (E) The magnetization phase profiles ϕ(s) for the cilia in (C) and (D). The neighboring cilia have the same constant magnitude in their M(s). (F) The linear mapping from Δϕx to Δψx in the metachronal waves. (G) Snapshots and overlapped trajectories of transporting neutrally buoyant particles by an artificial cilia carpet with 2D metachronal waves. (i), top view; (ii), side view. In (G), B(t): f = 2.5 Hz and Bm= 40 mT. Scale bars, 1 mm. Photo credit: Xiaoguang Dong, Max Planck Institute for Intelligent Systems.

By encoding different M(s) of a cilium (see fig. S3 and the “Simultaneous encoding of cilia magnetization profiles” section in Materials and Methods for encoding a specific magnetization profile), cilia dynamics with either a positive or negative swiping area can be produced as shown in fig. S4, which leads to a net fluid flow in different directions. The swiping area is a common metric to quantify the nonreciprocal motion and the induced net fluid flow (11, 27, 32). We define the swiping area ratio (SAR) as a metric to quantify the effectiveness of producing a net fluid flow within a unit time by a single cilium of length L, where . SAR is the normalized swiping area per unit time. Therefore, as SAR increases, the motion becomes more nonreciprocal, leading to increased fluid flows at low Re. A computer-aided method based on a fluid-structure interaction (FSI) model (see the “Summary of the used coordinate systems” and “FSI model of single cilium dynamics” sections in Materials and Methods) was developed to optimize SAR. The single-cilium dynamics mainly depends on the material elastic modulus, M(s), and B(t). We specifically optimized M(s) and B(t) to maximize SAR, as shown in fig. S5 and described in the “Optimizing a single cilium by maximizing the SAR” section in Materials and Methods. The notable advantage of our design method and system is that the individual cilium beating dynamics can be designed separately from their metachronal waves, giving substantial flexibility and viability of the collective motion.

Figure 1 (C and D) shows that arbitrary 1D metachronal waves can be further produced within an array of magnetic artificial cilia, by encoding phase shifts Δϕx = ϕi + 1(s) − ϕi(s) in M(s) (Fig. 1E) and applying a rotating B(t). The dynamics of each cilium remains the same for one period (see the “Mechanics and design methodology of metachronal waves” section in Materials and Methods for the mechanics). These 1D metachronal waves can be quantified by the lags in the motions of neighboring cilia, such as the lag time Δt in the periodic beating dynamics when each cilium tip reaches the maximal y position as shown in Fig. 1D. The phase shift in motions can be defined as (Δt ∈ [0, T)). The x component of the wave vector is thus given by kx = Δψx/dc for quantifying the spatiotemporal coordination. Consequently, Fig. 1F shows that Δϕx can be linearly mapped to Δψx and kx, which suggests that arbitrary 1D metachronal waves can be encoded into neighboring cilia. Figure 1F also shows the so-called symplectic (Δψx > 0) and antiplectic (Δψx < 0) metachronal waves (7), where the direction of the wave propagation and the power stroke are in the same and opposite directions, respectively.

Similar to biological cilia, Figure 1G and movie S2 show that our method also allows designing and fabricating artificial cilia arrays to emulate the propagation of 2D metachronal waves in both the x-y and x-z planes with arbitrary 2D wave vectors, by encoding both nonzero Δϕx and Δϕz into a 2D array. Different from the emergence of metachronal waves due to hydrodynamic interaction (12) and distal coupling (34) in biological systems, the metachronal waves in our system emerge from the rotational shift in the magnetization phase profile of each magnetic cilium subject to a rotating uniform magnetic field. Nonetheless, the resulting metachronal waves resemble those of their biological counterparts and can be used for investigating the function of metachronal coordination in producing fluid flows at low Re.

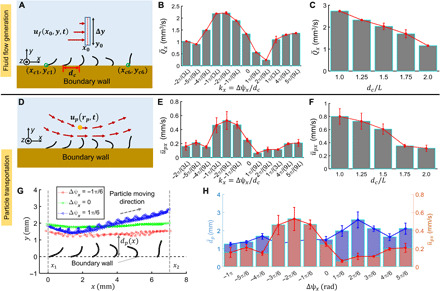

Optimal metachronal waves for pumping fluid flows efficiently

To find the optimal metachronal waves for pumping directional fluid flows, Fig. 2 (A to C) compares the directional fluid flow produced by our artificial magnetic cilia arrays with different kx (or Δψx) (Fig. 2B) and intercilium spacing dc (Fig. 2C), based on the particle image velocimetry (PIV) measurements inside glycerol (dynamic viscosity, 0.876 Pa·s; see the “Fluid flow measured by PIV” section in Materials and Methods for more details). Because of a small number of cilia at low Re, fluidic boundary/wall effects (11, 35) could be substantial if the cilia are placed inside confined fluidic channels or other confined spaces. Here, we avoided such effects by using nearly semi-indefinite boundary configuration as shown in Fig. 2A and fig. S2F. To quantify the performance of pumping directional fluid flows, we use the widely used average volume flow rate (11–13) in the direction of transportation (+x direction). In Fig. 2B, kx is varied from −2π/(3L) to 5π/(9L) when Δψx is varied from –π to 5π/6, while dc equals to 1.5L and other parameters are kept identical. It is found that antiplectic waves produce a maximal directional fluid flow when Δψx ∈ [−π/2, −π/6]. For example, artificial cilia arrays with Δψx = −π/3 achieve a of 4 mm3·s−1, which is about 1.6 times of that produced by arrays with synchronized motions and 4 times of the minimal net fluid flow produced by arrays with a symplectic wave (Δψx = π/3). In addition, Fig. 2C shows that artificial cilia arrays with denser spacing yield a larger , by varying the intercilium spacing dc from L to 2L while keeping Δψx = − π/3 and other parameters identical. The quantitative relationship between kx and is evident from Fig. 2 (B and C). Figure 2B shows that there exists an optimal wave vector between −π/(3L) and −π/(9L), which yields the maximal . At the same time, when increasing the magnitude of kx from π/(6L) to π/(3L), by reducing dc from 2L to L, an increase of can be visualized in Fig. 2C. Our experiments are in good agreement with computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulations (see fig. S6 and the “CFD simulations in comparison with experimental data” section in Materials and Methods) in terms of the overall trends, confirming the effect of the phase shift Δψx and intercilium spacing dc on the observed fluid flow. Our experiments prove the key role of antiplectic metachronal waves in enhancing fluid transportation. The finding is in accordance with that in biological systems (7, 36) and numerical works (12, 13) and introduces extra insights into the special function of antiplectic waves by reporting the specific range of wave factors for producing optimal net fluid flows.

Fig. 2. Optimal metachronal waves for pumping viscous fluids.

(A) Illustration of average volume flow rates . is the average fluid flow flux ufx(x0, y, t) passing through a selected plane x = x0 within m periods. The average volume flow rate is given by . (B) as a function of the wave vector kx with dc fixed at 1.5L. (C) as a function of intercilium spacing dc with Δψx fixed at . (D) Schematics of particle transportation by an artificial cilia array. up(rp, t), instant velocity of a neutrally buoyant particle at time t and position rp. (E) The average particle transportation speed in the +x direction as a function of the wave vector kxwith dc fixed at 1.5L. . (F) as a function of dc with Δψx fixed at . (G) Representative x-y trajectories of particles pumped by representative arrays . (H) The average distances () from particles to the boundary wall. . The avage particle transportation speed in (E) are replotted to the right axis for comparison. In all experiments, glycerol (dynamic viscosity, 0.876 Pa·s) is used. B(t): f = 2.5 Hz and Bm = 40 mT. Error bars indicate the SDs of n = 4 measurements.

While quantify the fluid transportation ability of artificial cilia arrays in the Eulerian space, we further investigate the effect of different metachronal waves and intercilium spacing on transporting and attracting particles in the Lagrangian space. In Fig. 2 (D to H) and movie S3, we compare the average transportation velocities of a tracer particle in the +x direction (Fig. 2D). Tracer particles (300 to 330 μm in diameter; density, 1.2 g·cm−3) are transported in the +x direction by artificial cilia arrays with kx varying from −2π/(3L) to 5π/(9L) when Δψx ∈ [− π,5π/6] and dc equaling to 1.5L (see the “Particle transportation using cilia arrays” section in Materials and Methods for experimental details). The Lagrangian coherent structures of the local time-periodic fluid flow guarantee consistent trajectories of neutrally buoyant tracer particles (37). Figure 2E shows that the artificial cilia arrays with kx ∈ [−π/(3L), −π/(9L)] when Δψx ∈ [−π/2, −π/6] could pump particles with a maximal average speed (~0.45 mm/s), agreeing with the trend in Fig. 2B. At the same time, artificial cilia arrays with denser spacing result in larger particle transportation speeds as shown in Fig. 2F, consistent with the results in Fig. 2C.

Comparing the particle transportation trajectories shows that another function of the optimal antiplectic waves is attracting free particles. Figure 2G shows that metachronal waves with Δψx varying from to attract particles closer to the ciliary surfaces compared with other designs. Figure 2H shows a negative correlation between (replotted from Fig. 2B) and the distance of particles to the boundary wall dp(x). Such a result could support the finding that biological cilia provide a key functionality of predation by attracting specific microbiomes toward their surfaces (38).

Mechanism of antiplectic waves enhancing fluid flows

The reason of the superior ability of enhancing fluid flows by antiplectic waves is further investigated. Figure 3 shows that metachronal waves can modulate local fluid flows by producing different time-varying boundary conditions to the fluid, thereby varying the overall fluid transportation performance. This observation is obtained by the PIV data of artificial cilia arrays with representative metachronal waves. The PIV results in Fig. 3A show that the local fluid flow around cilium no. 3 is strongly influenced by its neighboring cilia nos. 2 and 4. Compared with an artificial cilia array showing a symplectic wave, such as , the fluid flow induced by an artificial cilia array with an antiplectic wave, such as , is less blocked from neighboring cilia during the power stroke (t1 = 0.12T; Fig. 3A). This leads to an increased and more continuous local flow in the power stroke direction. Meanwhile, the flow is more blocked from neighboring cilia during the recovery stroke (t2 = 0.45T; Fig. 3A), resulting in a reduced and blocked local fluid flow in the recovery stroke direction.

Fig. 3. Local fluid flow modulated by the time-varying boundaries of artificial cilia arrays with different metachronal waves.

(A) Experimentally observed fluid flow distribution of representative artificial cilia arrays with antiplectic, synchronized, and symplectic waves (). The cilia in an array with antiplectic waves have less blocked local fluid flow from their neighbors during the power stroke, while more blocked local fluid flow during the recovery stroke, compared with the cases with symplectic waves. (B) Time-varying volume flow rate Qx passing through the cross section marked in (A) within a full period. (C) Metrics for quantifying time-varying boundary conditions, using the average intercilium tip distances within the power (dpower) and recovery (drecovery) strokes. (D) The time-varying intercilium tip distances of cilium no. 3 () in representative arrays (). The small variation of in the synchronized case is caused by imperfect synchronization due to fabrication errors. (E) Experimental data of and its predicted value. . p = 0.25 is a fitting variable. Error bars indicate SDs for n = 4 cilia (index, 2 to 5). In all experiments, glycerol (dynamic viscosity, 0.876 Pa·s) is used. B(t): f = 2.5 Hz and Bm = 40 mT. Scale bar, 1 mm.

To quantitatively see such a difference in local flows, Fig. 3B compares the instant volume flow rate Qx passing through a selected cross section within a full period. The observation is that although an artificial cilia array with synchronized motion induces a large and single peak value of Qx due to the superposition effect of all cilia, artificial cilia arrays with metachronal coordination yield smaller but multiple peak values of Qx. Therefore, to make a fair comparison, we compare Qx produced by two artificial cilia arrays with opposite phase shifts ( and ) to see the difference of their induced fluid flows. In these two representative cases, the artificial cilia array with an antiplectic wave () has a larger value of Qx during the power stroke and a smaller value of Qx during the recovery stroke, resulting in a larger net fluid flow within a period.

Simple metrics are further proposed to quantify the boundary conditions and predict the net fluid flow by artificial cilia arrays with different metachronal waves. To compare different instant boundary conditions, in Fig. 3C, we choose the instant inter-tip spacing (i = 2 to 5) between a selected cilium and its two neighbors to measure the no-slip boundary conditions. Figure 3D shows that antiplectic waves yield a larger during the power stroke and a smaller during the recovery stroke, compared with synchronized motions. In contrast, symplectic waves have a smaller during the power stroke and a larger during the recovery stroke. To compare different average boundary conditions and predict the corresponding average net fluid flows, we define the average within power and recovery strokes as dpower and drecovery, respectively, which quantify the average boundary conditions produced by different cases of metachronal coordination. In Fig. 3E, experimental data show that the overall trend of the quantitative relationship between and Δψx presented in Fig. 2B could be captured by a proportional law given by . This metric correlates the average volume flow rate to the intercilium spacing of artificial cilia with different metachronal waves.

Functional artificial cilia as fluidic devices by encoding optimal coordination

The established quantitative relationship and mechanism between fluid flows and metachronal coordination further allow creating bioinspired cilia arrays as versatile fluidic devices with unique and important functionalities at low Re. We demonstrate multiple functional fluidic devices by encoding diverse metachronal coordination and nonreciprocal motions.

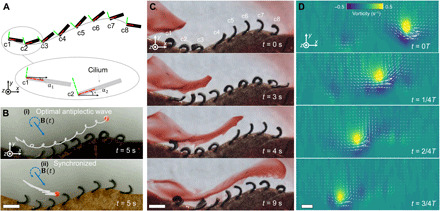

In Fig. 4 and movie S4, we first demonstrate a bioinspired cilia array with optimal metachronal waves propagating on curved surfaces inspired by coral reefs (2). Existing artificial cilia are only capable of pumping on flat surfaces (27–29, 32, 33), which does not resemble their biological counterparts in terms of boundary morphologies (7). In contrast, our developed artificial cilia array is capable of transporting particles along arbitrary curved surfaces, such as an S-shaped surface, as shown in Fig. 4A. To create bioinspired cilia planted on a boundary wall with much more complex curvatures, we generalize our method to include the cilium-attached coordinates {Lsi} and the individual dynamics of each cilium as two extra sets of design variables (see the “Encoding metachronal waves in cilia arrays on curved surfaces” section in Materials and Methods). The key design rule is to compensate the rotation of the cilium-attached coordinates when encoding the magnetization profile of each cilium such that a desired constant phase shift is kept between neighboring cilia even on curved surfaces (fig. S7).

Fig. 4. Bioinspired cilia arrays with optimal metachronal waves propagating on curved surfaces.

(A) Illustration of encoding metachronal waves in artificial cilia on curved surfaces. The key design rule is to compensate the rotation of the cilium-attached coordinate of each cilium by designing their magnetization phase profiles (see fig. S7). The red and green lines represent the +X and +Y axes of the cilium-attached coordinates, respectively. Cilia magnetization profiles: , where Δϕ = −π/4. Boundary wall positions:, where xci (i = 1,2, …,8) is chosen with an equal spacing from −4L to 4L. (B) Comparison of the particle transportation performance between bioinspired cilia arrays with an (i) optimal metachronal wave (Δψs = −π/4) and (ii) synchronized motion (Δψs = 0). (C) Video snapshots of the fluid flow induced by an artificial cilia array (Δψs = −π/4) visualized by a food dye. Each column in an array has three identical cilia in the z direction. (D) Sequence of fluid flow vorticity and velocity distributions produced by the bioinspired cilia array with an optimal metachronal wave within a full period. Fluid flow data were measured using PIV. B(t): f = 2.5 Hz and Bm = 40 mT. Scale bars, 1 mm. Photo credit: Xiaoguang Dong, Max Planck Institute for Intelligent Systems.

With this design methodology, we develop a bioinspired cilia array with optimal metachronal waves, which can pump viscous fluids along curved surfaces. Figure 4B shows that such a bioinspired cilia array could transport particles tangentially to the attaching surface more efficiently, compared with an array with the same boundary wall but with synchronized motions due to the locally enhanced vortical flow, as visualized by dye and PIV in Fig. 4 (C and D, respectively). More bioinspired cilia arrays could be constructed with various complex boundary morphologies, such as large-polyped, mounding, and encrusting colony morphologies (39). Important scientific questions, such as how geometrical details of colony morphology affect the transportation performance of coral reefs (2) and similar cilia-covered organisms, can be potentially answered in the future to help researchers better understand the active mass transportation in ambient aquatic environments.

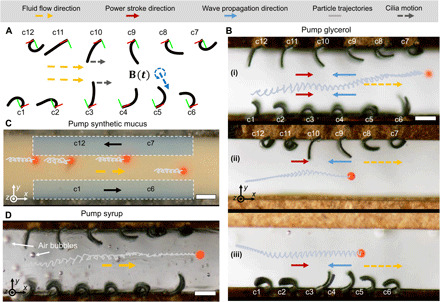

Pumping viscous fluids in narrow channels at low Re is challenging because of the no-slip boundary conditions (40) but is important in many biological systems, such as tubal transportation of ova in female fallopian tubes, where ciliary motion contributes to efficient transportation in addition to muscular contractility (5). In Fig. 5 and movie S5, we demonstrate efficient transportation of particles in narrow channels filled with glycerol, by mimicking the natural cilia in tubal transportation. As shown in Fig. 5A, we jointly designed two cilia arrays with opposite SARs (see fig. S4), as their pumping directions are in the same direction (in {La}) subject to the same rotating B(t). Within each array, an optimal antiplectic metachronal wave is further encoded. In this way, the device transports fluids and particles faster () than single cilia arrays only on the top () and bottom () side of the channel wall (Fig. 5B). We also demonstrate pumping synthetic mucus (; Fig. 5C) and syrup (; Fig. 5D) in narrow channels using such a device, which could potentially help understand tubal transport of viscous biofluids in physiologically optimized environment for fertilization and early embryonic development (41).

Fig. 5. Transportation of viscous fluids in narrow channels.

(A) Illustration of designing an artificial cilia array for pumping fluids in narrow channels. Designed magnetization phase profiles ϕi(s) of each cilium in c1 to c6: , where ; c7 to c12: , where . Cilia in two arrays are designed to have opposite SAR (see fig. S4). The red and green lines represent the +X and +Y axes of the cilium-attached coordinate, respectively. (B) Viscous fluids (glycerol) pumping in a narrow channel visualized by particle transportation. (i) Cilia in the two arrays (three layers) with the design illustrated in (A). (ii) Single array with a negative SAR. (iii) Single array with a positive SAR. The duration of particle trajectories is 16 s. B(t): f = 2 Hz and Bm = 38 mT. (C) Snapshot of the fluid flow during pumping synthetic mucus with multiple tracer particles inside. B(t): f = 2.5 Hz and Bm = 40 mT. (D) Trajectories of tracer particles in syrup pumped by two artificial cilia arrays in a narrow channel. B(t): f = 2 Hz and Bm = 40 mT. Scale bars, 1 mm. Photo credit: Xiaoguang Dong, Max Planck Institute for Intelligent Systems.

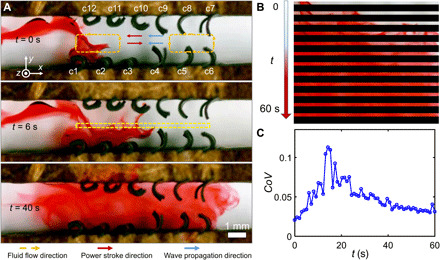

In addition to the functionality of transportation, in Fig. 6 and movie S6, we demonstrate that optimal metachronal coordination can be encoded into two arrays of artificial cilia for efficient fluid mixing function. Mixing adjacent laminar flow completely and rapidly at low Re is difficult while important for many applications (25). At low Re (<0.1), passive mixing devices usually require specific design of channel geometries, using chemical reactions, limiting the applicable scenarios. Other active mixing devices, such as magnetic micropillars, have limited mixing thoroughness between vertical layers due to their cone-shaped stirring motions (28). Here, we demonstrate a mixing device capable of mixing viscous fluids thoroughly and rapidly by encoding optimal coordination into two artificial cilia arrays. The cilia in the bottom array in Fig. 6A have an optimal metachronal wave () for inducing a directional flow. Meanwhile, the cilia in the top array are producing a transverse flow by periodically beating opposite to their faced cilia in the bottom array. Visualized by a dye, the viscous glycerol can be rapidly mixed with a coefficient of variation (25) less than 0.05 within 35 s in a channel across a volume of 43 mm3 at a local Re < 0.03, as shown in Fig. 6 (B and C).

Fig. 6. Mixing viscous fluids efficiently and completely at low Re.

(A) Mixing of viscous fluids by producing directional and transverse flows visualized by the dye. Cilia in the bottom array (cilia in columns c1 to c6, ) have an optimal metachronal wave for creating a directional flow. Cilia in the top array (cilia in columns c7 to c12, ) are creating a transverse flow by beating oppositely to the faced cilia in the top array. Magnetization phase profiles: c1 to c6,; c7 to c12, . In both arrays, . Photo credit: Xiaoguang Dong, Max Planck Institute for Intelligent Systems. (B) Snapshots of the mixing process in a sample region. The sample region is enclosed with yellow dashed lines marked in (A). (C) Coefficient of variation (CoV) as a metric for quantifying the mixing performance. CoV = σ/μ, where σ and μ are the SD and mean value of the gray scale value across the region marked by yellow dashed lines in (A). B(t): f = 2.5 Hz and Bm = 40 mT.

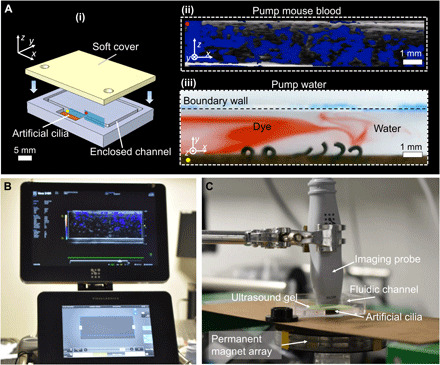

Last, the wireless magnetic actuation of our fluidic devices combined with ultrasound medical imaging could allow remote pumping and imaging of body fluids in enclosed small spaces with no physical contact, potentially applicable in the human body in the future for biomedical applications. As a proof of concept, in Fig. 7 and movie S7, we demonstrate the ability of pumping body fluids, such as fresh whole mouse blood in narrow channels (see the “Preparation and characterization of fluids” section in Materials and Methods), showing the promising function of pumping biofluids ex vivo and in vivo in future biomedical applications. They could potentially be deployed by a medical catheter or locomote by remote actuation (16) to target sites in the human body for delicate and minimally invasive noncontact fluidic or object/cell manipulation (42). These devices have potential to be applied in health care for patients with specific ciliary dysfunctions, such as assisting in pumping mucus in human respiratory systems and transporting ovum in female fallopian tubes for improving fertilization (5).

Fig. 7. Pumping and imaging biofluids in enclosed channels.

(A) The cilia array pumping in enclosed channels. (i) Schematics of the enclosed channel. (ii) Pumping fresh mouse blood visualized by ultrasound imaging. The color indicates flow velocity of mouse blood flow ( and ). The red dots mark the same position in (i) and (ii). B(t): f = 7 Hz and Bm = 40 mT. Contrast enhancement particles/microbubbles are used for enhancing ultrasound imaging quality. (iii) Pumping water visualized by dye ( and ). The yellow dots mark the same position in (i) and (ii). B(t): f = 2 Hz and Bm = 40 mT. (B) Photo of an ultrasound imaging system (Vevo 3100, VisualSonics Inc.). (C) Photo of the experimental setup for actuating the artificial cilia and imaging fluid flow via an ultrasound probe. Ultrasound gel is used between the ultrasound probe and the top surface of the fluidic channel for enhancing the imaging signal. Photo credit: Xiaoguang Dong and Wenqi Hu, Max Planck Institute for Intelligent Systems.

DISCUSSION

We have developed bioinspired ciliary devices, which not only provide remarkable insights of how the time-varying boundaries of ciliary surfaces by different metachronal coordination could lead to different cooperatively generated ciliary flows but also use these findings to enable unprecedented optimized engineering applications. The reported design methodology is applicable in principle to scale the artificial cilia down to the size of real cilia (~10 μm in length). A scaling analysis (see the “Scaling analysis of single cilium dynamics” section in Materials and Methods) shows the feasibility of scaling down the overall size of ferromagnetic sheets to the micrometer scale. Microfabrication of ferromagnetic materials using recent advance of fabrication methods (43) could potentially allow manufacturing smaller artificial cilia arrays with metachronal waves in the future, although challenges of weaker magnetization, limited geometry, and limited material properties still need to be overcome.

Biological cilia are densely packed rod structures capable of nonreciprocal 2D or 3D motions (44), with a length scale of ~10 μm, beating at 5 to 30 Hz (7). In our system, instead of mimicking the biological cilia, we aim at developing artificial cilia with metachronal coordination similar to their biological counterparts, by keeping the critical dimensionless number (e.g., Re) similar. As the fundamental physical law is the same, we can study a scientific question in cilia mechanics: the function of the metachronal coordination in inducing fluid flows at low Re. With such a platform, we find that antiplectic waves can indeed enhance fluid flows within the scope of our investigation space. This finding agrees with that in biological systems (7, 36) and numerical studies reported before (12, 13), bringing extra insights into the ciliary biological systems.

In addition, the developed artificial cilia array with programmable nonreciprocal motion and metachronal coordination could be used as a scientific tool to further investigate many interesting scientific questions, such as how the fluid flow patterns would be different when varying the cilia beating dynamics (45), boundary geometries (38), location of topological defects (6), and the conditions of the surrounding fluidic environment (46). We anticipate our design method and developed soft miniature devices that could open a wide range of unprecedented opportunities for studying ciliary biomechanics and creating cilia-inspired wireless microfluidic pumping, object manipulation and lab- and organ-on-a-chip devices, mobile microrobots, and bioengineering systems.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fabrication of ferromagnetic cilia

The ferromagnetic-elastic sheet–based artificial cilia were made of composite materials of silicone rubber (Ecoflex 00-30, Smooth-On Inc.) and NdFeB hard magnetic microparticles (average diameter, 5 μm; MQFP-15-7, Neo Magnequench) with a weight ratio of 1:1. The two materials were mixed together and then poured on to a poly(methyl methacrylate) substrate with tapes as spacers for controlling the thickness to be 100 μm. The top surface of the mixed material was scraped by a single-edge razor blade (fig. S1A). The composite material was cured in room temperature for about 4 hours or cured in 1 hour by putting it on a hot plate at 60°C. After curing, as illustrated in fig. S1B, the ferromagnetic cilia were cut by a laser machine (LPKF ProtoLaser R3, LPKF Laser & Electronics AG) according to a designed dimension of 1 mm by 550 μm by 100 μm (L × w × tb) marked in fig. S1C. Other dimension parameters in fig. S1C are given by L1 = 300 μm, w1 = 850 μm, and w2 = 200 μm. The material has a density of (2.00 ± 0.056) × 103 kg·m−3 and an average Young’s modulus of 144 kPa measured by a tensile testing machine (5940 series, Instron GmbH). In the experiments, we observed that the performance of the device is quite robust without any degradation issue. The dynamics of the artificial cilia array do not change even several months after its first use, when actuated with the same control signals in the same fluids. According to a previous study, structures made of Ecoflex 00-30 can maintain their mechanical properties after being subjected to cyclic loads for over 106 cycles (47).

Simultaneous encoding of cilia magnetization profiles

We used a jig-assisted method reported in our previous work (18) but extended it to simultaneously encode the desired different M(s) of multiple ferromagnetic cilia using one magnetizing jig. Figure S1D illustrates the principle and process to encode the desired different M(s) on multiple cilia simultaneously. To obtain a desired magnetization profile, multiple ferromagnetic cilia are prebent into a jig with multiple cutout parts in designed shapes. They are then magnetized by applying a large magnetizing B (magnitude, 1.2 T) in the +x direction inside a vibrating sample magnetometer (EZ7 VSM, MicroSense LLC). The shape of the cutout part corresponding to each cilium is parameterized with a local slope angle profile , which is the tangent angle at each element along the middle line in the cutout part (fig. S1D). To encode ϕi(s) = ϕ0(s) + (i − 1)Δϕ for a given cilium, we have . For multiple cilia, to encode desired Mi(s) in an array simultaneously, the inverse design of the cutout part of the magnetizing jig is thus given by

| (1) |

| (2) |

Figure S3 shows that we encoded the desired M(s) by comparing the measured and predicted magnetic fields produced by a magnetized single cilium and array of cilia at their surfaces.

Assembly of artificial cilia arrays

Figure S1 (E and F) illustrates the procedure of assembling ferromagnetic cilia into an array. The magnetized cilia were manually attached to an assembly fixture and fixed by glue (Loctite 401, Henkel AG) under a stereomicroscope (Stemi 508, Carl Zeiss AG). Motorized micromanipulators could be potentially incorporated for automating such a task in the future.

Magnetic actuation of ferromagnetic cilia

As shown in fig. S2 (A and B), a rotating Halbach array composed of 12 cubic ferromagnets (12 mm by 12 mm by 12 mm; N42, Supermagnet.de) was used for generating a rotating uniform magnetic field. The rotational motion was actuated by a dc motor (Parallax Continuous Rotation Servo, Parallax Inc.) and controlled by an embedded controller (Arduino Uno, Arduino.cc). B(t) was characterized in fig. S2 (C to E). The magnetic field strength was about 40 mT (at 15 mm above the surface of the magnet array). On this plane, the uniformity of the magnetic field in the workspace was ~95% within a circular area of 10 mm in diameter, which covered the whole artificial cilia array in the experiments. The artificial cilia array was fixed in a container (43 mm by 32 mm by 11 mm; fig. S2F) filled with glycerol (99.8% volume ratio) and supported on a customized sample holder above the Halbach array. We used glycerol as a viscous liquid in the experiments because it has a high viscosity to create a low Re environment and does not cause swelling of the elastic cilia. The fluid had a density of 1.257 ×103 kg·m−3 and a dynamic viscosity of 0.876 Pa·s at the room temperature 25°C.

General design methodology

Summary of the used coordinate systems

Three coordinate systems in this work are presented in fig. S2 (A and G) and summarized as below. First, the global coordinate system {Gb} (xb, yb, zb) is located at the center of the Halbach array for expressing the global actuation magnetic field and location of the artificial cilia arrays. Second, the array-attached coordinate system {La} (x, y, z) is located on the base of the artificial cilia array, which is used to express the dynamics of artificial cilia, fluid flow, and particle transportation. Last, the cilium-attached coordinate system {Lsi} (X, Y, Z) of the i-th cilium in an array is located on the body of the cilium, which is used to describe its relative orientation and position within an array and to express the magnetization profile of each cilium.

FSI model of single-cilium dynamics

An FSI model in 2D is presented to guide the design of single ferromagnetic-elastic cilia. The motion of a given cilium is modeled using the Euler-Bernoulli beam theory for large deflections (18) while considering fluid drags. At quasi-static states, the governing equations are given below for a cilium with one end fixed to the boundary wall. For an infinitesimal element [s s + ds] of the i-th cilium (i = 1,2, …, n) in an array, the moment balance equation at a quasi-static state in the Eulerian space is given by

| (3) |

where θi(s, t) is the rotation angle at time t, E is the Young’s modulus, Across = wtb is the cross-sectional area, is the second moment of area, nz is the unit vector along the +Z axis, B(t) = Bm[cos (ωt) sin (ωt) 0 ]T is the rotational external magnetic field in the X-Y plane, Mi(s) = [Mix(s) Miy(s) 0]T is the magnetization profile function, and F(s, t) = [Fh Fv]T is the internal force of the cilium.

The force balance equation is given by

| (4) |

where Anormal = wds is the side area of the infinitesimal element and Fd is the fluid drag force per volume on the infinitesimal element. Fd is a function of the local drag coefficient Cd assuming a cylinder geometry based on local curvatures (48) and the relative velocity between the element and fluid flow. Fd is further given by

| (5) |

| (6) |

where ρf is the density of the fluid and β is a scaling factor to calibrate the damping coefficient, as it is generally difficult to exactly match the local drag coefficient Cd (48, 49). The local Re is given by , where μf is the dynamic viscosity of fluids. In addition, the Cartesian position us(s, t) of the cilium is given by

| (7) |

The boundary conditions are given by a set of equations

| (8) |

The initial conditions are given by another set of equations

| (9) |

The cilia motions are assumed to be planar by imposing a large width-to-length ratio (w/L = ~0.6) to minimize the out-of-plane twisting and bending motions. The single-cilium oscillating beating dynamics under a rotating B(t) can be predicted using the above model as shown in fig. S8.

Optimizing a single cilium by maximizing the SAR

The SAR is optimized on the basis of the discussed FSI model in the above section. The dynamics of a single cilium in viscous fluids is a function of M(s), its physical dimensions, and B(t). The 2D magnetization profile along the i-th cilium with a length L, is given by

| (10) |

| (11) |

We first fix the magnitude of M(s), as 40 kA·m−1 and assume that the magnitude of external magnetic field is Bm = 40 mT. Then, for simplicity, ϕi(s) is represented in a general continuous polynomial function with a first-order approximation as since the high-order terms are less important in determining the cilium dynamics. As shown in fig. S5 (A and B), we carried out a systematic parameter sweeping for the total phase span ϕi(0) − ϕi(L) of a single cilium. We found that a maximal positive SAR could be obtained when ϕi(0) − ϕi(L) = 1.75π (used in all experiments if not explicitly mentioned) and a maximal negative SAR could be obtained when ϕi(0) − ϕi(L) = 0 (used in Fig. 5). These two magnetization profiles are optimal within a practical range (−1.75π to 1.75π) constrained by the template-based magnetizing method.

The magnitude Bm and frequency f of B(t) are another two control inputs of the dynamics of a single cilium. Increasing f will increase SAR, but the maximal Re will also increase (fig. S5C). Therefore, we constrained f to ensure that our cilia arrays operate at the low Re regime in the experiments. In addition, a larger Bm yields a larger SAR (fig. S5D) until the cilium’s deformation is limited by the boundary walls.

In addition, the dimensions of the artificial cilium also affect the motion. We defined two ratios, the thickness-to-length ratio (rtl) and the width-to-length ratio (rwl), to explain their effect based on our models. rtl has a major effect on the magnitude of the cilia motion. With the same actuation magnetic fields, artificial cilia with a larger rtl will exhibit a smaller maximal bending angle and a smaller SAR, as shown in fig. S9, while the buckling motion is more evident, yielding a larger output force during the power stroke after being deformed to the same state. In addition, rwl has less effect on the planar cilia motion according to Eq. 3 in the “FSI model of single cilium dynamics” section, while mainly affecting the out-of-plane motion of a single cilium. By increasing the width to length ratio (~0.6), the undesired out-of-plane motions could be minimized.

Mechanics and design methodology of metachronal waves

Each member within an array of ferromagnetic cilia is a distributed oscillator subject to a rotating magnetic field B(t) = Rz(ωt)B(0). The phases of these oscillators can be represented by their body slope angles θi(s, t). For two neighboring cilia, we have the following moment-balancing equations

| (12) |

| (13) |

The temporal differences in the time-varying and spatially distributed external magnetic torques create the metachronal waves. To be more specific, the external magnetic torques applied on the i-th and (i + 1)-th cilia are given by

| , | (14) |

| (15) |

The phase shift Δϕ in M(s) can be equivalently represented as Δϕ in B(t) due to the mathematical properties of the cross product in 2D as shown in Eq. 15. Therefore, the phase shifts are equivalently produced in the oscillating motions of neighboring cilia.

CFD simulations in comparison with experimental data

To model the fluid flow created by the artificial cilia arrays, we use a 3D bidirectional CFD model (15), which can accurately describe the magnetic torque on the cilia, the deformation of the cilia, and the deformation-induced fluid flow at low Re [see fig. S6 (A and B)]. The model accounts for the fully coupled bidirectional solid-fluid interaction between cilia and fluid, including the cilia deformation induced by the fluid. The computational framework is briefly summarized here. In the CFD model, the cilia are represented by an assemblage of shell elements, which act as an internal boundary to the fluid. The FSI is considered by implicitly coupling the fluid dynamics and solid mechanics equations, where the Stokeslet method is used to account for the viscous drag and implemented using a boundary-element approach. To model the ciliary deformation, we use shell elements with the bending and membrane behavior accounted for by using triangular Kirchhoff elements (50) and constant strain triangles with drilling degrees of freedom (51), respectively. The large and geometrically nonlinear deformation of the cilia is modeled by adopting an updated Lagrangian approach. We focus on flows at low Re and use Green’s functions (52) to simulate fluid motion in the Stokes regime. The solid and fluid are implicitly coupled through a no-slip boundary condition.

We compared the effect of the phase shift Δψx (fig. S6C) and intercilium spacing dc (fig. S6D) on inducing fluid flow in the simulated and experimental scenarios. The simulations also show that the antiplectic waves produce a maximal directional fluid flow when and artificial cilia arrays with a denser spacing generate a larger. Although a discrepancy exists in the absolute quantitative values due to the simplified assumption and approximated parameters of the CFD model, as well as experimental uncertainties, the simulation results can support our findings in experiments in terms of the overall trends.

Encoding metachronal waves in cilia arrays on curved surfaces

The metachronal coordination can be encoded into cilia arrays planted on a curved boundary wall using the design rule of Δβ = Δϕ + Δα. Here, Δα = αi + 1 − αi describes the variation of the slope angles along the curved surface by defining the rotational difference between the cilium-attached coordinates {Ls(i+1)} and {Lsi} of two neighboring cilia. The distributed magnetic torques induced on these cilia have a relationship of Therefore, the magnetization phase profiles of two neighboring cilia in the global frame are given by

| (16) |

| (17) |

To create metachronal waves on arbitrary curved surfaces, ϕi(s) of each cilium is inversely designed together with {Lsi} as

| (18) |

| (19) |

where is the angle between the +Xi axis of {Lsi} relative to the surface tangent vector direction along the boundary wall surface. Specifically, in the bioinspired cilia array in Fig. 4, , , and , where xci (i = 1,2, …,8) was chosen with an equal spacing from −4L to 4L.

Scaling analysis of single-cilium dynamics

We first define VE to quantify the relative scaling of viscous drag and elastic stress on an infinitesimal element, which is given by

| (20) |

where the derivative of cilium curvature is scaling to L−2. This equation shows that the viscosity of the fluid needs to be decreased for reducing the damping effect, , when L scales down.

We then define ME to quantify the relative scaling of magnetic torque and elastic stress on an infinitesimal element, which is given by

| (21) |

This equation shows that the same M(s) and B(t) can induce similar elastic stress within the cilium when L scales down.

One practical limitation of our system is that the intercilium spacing dc cannot be less than a body length. As dc further decreases, the dynamics of artificial cilia may be affected by magnetic local interactions. The critical distance between neighboring cilia is a complex function of the magnetization profile M(s), the material stiffness, and the magnitude of external magnetic fields B(t). To alleviate such an effect, it is found that we could reduce the magnitude of M(s), increase the material Young’s modulus E, or increase the magnitude of B(t). More research on this critical distance will be carried out in the future.

Fluid flow measured by PIV

A PIV system (Dantec Dynamics, Dantec Inc.) was integrated with the magnetic actuation setup for visualizing and quantifying the induced fluid flows (fig. S1A). The fluorescent tracing particles (Cospheric Inc.) used in the PIV experiments had an average diameter of 2 μm. A high-speed camera (Phantom MicroLab 140, Vision Research, Ametek Inc.) with a framerate up to 5000 frames per second (fps) was used for recording the dynamics of cilia and the motion of tracing particles. The acquired image sequences were further analyzed using the software DynamicStudio 6.1 (Dantec Dynamics, Dantec Inc.) and customized codes implemented in MATLAB 2017a (MathWorks Inc.). As illustrated in Fig. 2A, we obtained the average volume flow rate by integrating the average fluid flow flux passing through a cross plane perpendicular to the +x direction at x = x0. Three layers of identically designed arrays are stacked in the z direction to emulate a ciliary carpet that has a larger fluid flow than a single layer. The image plane is selected as the middle plane of three layers (see fig. S1B and Materials and Methods for more details). The key parameters for calculating in Fig. 2 (B and C) included y0 = 0.5L, Δy = 3L, Δz = 3w, ϵ = 0.1L, and m = 4. All variables were represented in the array-attached coordinate system {La}.

Particle transportation using cilia arrays

Fluorescent polyethylene microspheres (1.20 g·cm−3, 300 to 355 μm in diameter) were used as neutrally buoyant tracer particles because their densities are close to glycerol (1.257 g·cm−3), so that the particle’s motion reflects the fluid velocity by minimizing the effect from the gravity and buoyancy. Two cameras (Flea 3 USB3, FLIR Systems Inc.) were used for recording the trajectories of particles at about 30 fps. Particles trajectories were extracted by segmenting particle contours from the video sequences using color-based filtering algorithms implemented in MATLAB R2017a (MathWorks Inc.). The average speeds of particles were calculated along a trajectory with a displacement of 7 mm in the + x direction (Fig. 2G). The SDs were for n = 5 trials using each artificial cilia array. For each trial of the experiment, the particle was released from the same position.

Preparation and characterization of fluids

The fluids used for pumping demonstrations included deionized water, mouse blood, synthetic mucus, and syrup. Fluids of low viscosity include fresh mouse blood (Innovative Grade US Origin Mouse CD 1 Whole Blood; Fig. 7A) and deionized water (Fig. 7B). The mouse blood is shear-thinning with a dynamic viscosity of ~10 mPa·s at a shear rate of 2.4 s−1 (53). Viscous fluids in addition to glycerol include synthetic mucus (synthetic nasal mucus, Kryolan Professional Make-up GmbH; Fig. 5C) and syrup (rice syrup, Serapis Culinary; Fig. 5D). Figure S10 shows the rheology properties of the synthetic mucus and syrup. The rheology test is carried out in a Discovery HR-2 rheometer from TA Instruments Inc.

Statistical analysis

The SDs are indicated in the figure captions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank all members of the Physical Intelligence Department at the Max Planck Institute for Intelligent Systems for their comments. Funding: This work is funded by the Max Planck Society and European Research Council (ERC) Advanced Grant SoMMoR project with grant no. 834531. Author contributions: X.D., G.Z.L., W.H., and M.S. proposed the research. X.D. designed the experiments. X.D., W.H., and Z.R. performed the experiments. X.D. analyzed the data. R.Z. and P.R.O. performed the CFD simulations. M.S. planned and supervised the research. X.D., W.H., and M.S. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors. All authors commented on or edited the manuscript. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data and material availability: The modeling and design of the single-cilium dynamics was performed using customized codes implemented in MATLAB R2017a (MathWorks Inc.). The CFD analysis was performed using customized codes using FORTRAN (IFORT 13.1.2). These codes are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author. All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/6/45/eabc9323/DC1

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Tamm S. L., Ciliary motion in Paramecium: A scanning electron microscope study. J. Cell Biol. 55, 250–255 (1972). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shapiro O. H., Fernandez V. I., Garren M., Guasto J. S., Debaillon-Vesque F. P., Kramarsky-Winter E., Vardi A., Stocker R., Vortical ciliary flows actively enhance mass transport in reef corals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 13391–13396 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Knowles M. R., Boucher R. C., Mucus clearance as a primary innate defense mechanism for mammalian airways. J. Clin. Invest. 109, 571–577 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Faubel R., Westendorf C., Bodenschatz E., Eichele G., Cilia-based flow network in the brain ventricles. Science 353, 176–178 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lyons R. A., Saridogan E., Djahanbakhch O., The reproductive significance of human fallopian tube cilia. Hum. Reprod. Update 12, 363–372 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fliegauf M., Benzing T., Omran H., When cilia go bad: Cilia defects and ciliopathies. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 880–893 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gilpin W., Bull M. S., Prakash M., The multiscale physics of cilia and flagella. Nat. Rev. Phys. 2, 74–88 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Purcell E. M., Life at low Reynolds number. Am. J. Phys. 45, 3 (1977). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elgeti J., Winkler R. G., Gompper G., Physics of microswimmers—Single particle motion and collective behavior : A review. Rep. Prog. Phys. 78, 056601 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gueron S., Levit-Gurevich K., Energetic considerations of ciliary beating and the advantage of metachronal coordination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 12240–12245 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khaderi S. N., den Toonder J. M. J., Onck P. R., Microfluidic propulsion by the metachronal beating of magnetic artificial cilia: A numerical analysis. J. Fluid Mech. 688, 44–65 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elgeti J., Gompper G., Emergence of metachronal waves in cilia arrays. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 10, 4470–4475 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Osterman N., Vilfan A., Finding the ciliary beating pattern with optimal efficiency. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 15727–15732 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Niedermayer T., Eckhardt B., Lenz P., Synchronization, phase locking, and metachronal wave formation in ciliary chains. Chaos 18, 037128 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khaderi S. N., Onck P. R., Fluid-structure interaction of three-dimensional magnetic artificial cilia. J. Fluid Mech. 708, 303–328 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu W., Lum G. Z., Mastrangeli M., Sitti M., Small-scale soft-bodied robot with multimodal locomotion. Nature 554, 81–85 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ren Z., Hu W., Dong X., Sitti M., Multi-functional soft-bodied jellyfish-like swimming. Nat. Commun. 10, 2703 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lum G. Z., Ye Z., Dong X., Marvi H., Erin O., Hu W., Sitti M., Shape-programmable magnetic soft matter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, E6007–E6015 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu T., Zhang J., Salehizadeh M., Onaizah O., Diller E., Millimeter-scale flexible robots with programmable three-dimensional magnetization and motions. Sci. Robot. 4, eaav4494 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim Y., Yuk H., Zhao R., Chester S. A., Zhao X., Printing ferromagnetic domains for untethered fast-transforming soft materials. Nature 558, 274–279 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ijspeert A. J., Biorobotics: Using robots to emulate and investigate agile locomotion. Science 346, 196–203 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gravish N., Lauder G. V., Robotics-inspired biology. J. Exp. Biol. 221, jeb138438 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pfeifer R., Lungarella M., Iida F., Self-organization, embodiment, and biologically inspired robotics. Science 318, 1088–1093 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cacucciolo V., Shintake J., Kuwajima Y., Maeda S., Floreano D., Shea H., Stretchable pumps for soft machines. Nature 572, 516–519 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stone H. A., Stroock A. D., Ajdari A., Engineering flows in small devices. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 36, 381–411 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sitti M., Miniature soft robots—Road to the clinic. Nat. Rev. Mater. 3, 74–75 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khaderi S. N., Craus C. B., Hussong J., Schorr N., Belardi J., Westerweel J., Prucker O., Rühe J., den Toonder J. M. J., Onck P. R., Magnetically-actuated artificial cilia for microfluidic propulsion. Lab Chip 11, 2002–2010 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shields A. R., Fiser B. L., Evans B. A., Falvo M. R., Washburn S., Superfine R., Biomimetic cilia arrays generate simultaneous pumping and mixing regimes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 15670–15675 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vilfan M., Potočnik A., Kavčič B., Osterman N., Poberaj I., Vilfan A., Babič D., A. Self-assembled artificial cilia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 1844–1847 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hanasoge S., Hesketh P. J., Alexeev A., Metachronal motion of artificial magnetic cilia. Soft Matter 14, 3689–3693 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tsumori F., Marume R., Saijou A., Kudo K., Osada T., Miura H., Metachronal wave of artificial cilia array actuated by applied magnetic field. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 55, 06GP19 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Khaderi S. N., Baltussen M. G. H. M., Anderson P. D., Ioan D., den Toonder J. M. J., Onck P. R., Nature-inspired microfluidic propulsion using magnetic actuation. Phys. Rev. E 79, 046304 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gu H., Boehler Q., Cui H., Secchi E., Savorana G., De Marco C., Gervasoni S., Peyron Q., Huang T.-Y., Pane S., Hirt A. M., Ahmed D., Nelson B. J., Magnetic cilia carpets with programmable metachronal waves. Nat. Commun. 11, 2637 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wan K. Y., Goldstein R. E., Coordinated beating of algal flagella is mediated by basal coupling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, E2784–E2793 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blake J. R., Liron N., Aldis G. K., Flow patterns around ciliated microorganisms and in ciliated ducts. J. Theor. Biol. 98, 127–141 (1982). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blake J., A model for the micro-structure in ciliated organisms. J. Fluid Mech. 55, 1–23 (1972). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haller G., Lagrangian coherent structures. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 47, 137–162 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gilpin W., Prakash V. N., Prakash M., Vortex arrays and ciliary tangles underlie the feeding-swimming trade-off in starfish larvae. Nat. Phys. 13, 380–386 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lewis J. B., Price W. S., Patterns of ciliary currents in Atlantic reef corals and their functional significance. J. Zool. 178, 77–89 (1976). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dunne P., Adachi T., Dev A. A., Sorrenti A., Giacchetti L., Bonnin A., Bourdon C., Mangin P. H., Coey J. M. D., Doudin B., Hermans T. M., Liquid flow and control without solid walls. Nature 581, 58–62 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ezzati M., Djahanbakhch O., Arian S., Carr B. R., Tubal transport of gametes and embryos: A review of physiology and pathophysiology. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 31, 1337–1347 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ye Z., Sitti M., Dynamic trapping and two-dimensional transport of swimming microorganisms using a rotating magnetic microrobot. Lab Chip 14, 2177–2182 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cui J., Huang T.-Y., Luo Z., Testa P., Gu H., Chen X.-Z., Nelson B. J., Heyderman L. J., Nanomagnetic encoding of shape-morphing micromachines. Nature 575, 164–168 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.M. J. Sanderson, Cilia, in Biology of the Integument, J. Bereiter-Hahn, A. G. Matoltsy, K. S. Richards, Eds. (Springer, 1984). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brennen C., Winet H., Fluid mechanics of propulsion by cilia and flagella. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 9, 339–398 (1977). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Machemer H., Ciliary activity and the origin of metachrony in Paramecium: Effects of increased viscosity. J. Exp. Biol. 57, 239–259 (1972). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mosadegh B., Polygerinos P., Keplinger C., Wennstedt S., Shepherd R. F., Gupta U., Shim J., Bertoldi K., Walsh C. J., Whitesides G. M., Pneumatic networks for soft robotics that actuate rapidly. Adv. Funt. Mater. 24, 2163–2170 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Taylor G., Analysis of the swimming of microscopic organisms. Proc. R. Soc. A 209, 447–461 (1951). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Baumgart J., Friedrich B. M., Fluid dynamics: Swimming across scales. Nat. Phys. 10, 711–712 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Batoz J.-L., Bathe K.-J., Ho L.-W., A study of three-node triangular plate bending elements. Int. J. Numer. Methods Eng. 15, 1771–1812 (1980). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Allman D. J., A compatible triangular element including vertex rotations for plane elasticity analysis. Comput. Struct. 19, 1–8 (1984). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Blake J. R., A note on the image system for a Stokeslet in a no-slip boundary. Math. Proc. Camb. Philos. Soc. 70, 303–310 (1971). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Windberger U., Bartholovitsch A., Plasenzotti R., Korak K. J., Heinze G., Whole blood viscosity, plasma viscosity and erythrocyte aggregation in nine mammalian species: Reference values and comparison of data. Exp. Physiol. 88, 431–440 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/6/45/eabc9323/DC1