Abstract

Dendritic cells are an important link between innate and adaptive immune response. The role of dendritic cells in bone homeostasis, however, is not understood. Osteoporosis medications that inhibit osteoclasts have been associated with osteonecrosis, a condition limited to the jawbone, thus called medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (MRONJ). We propose that disruption of the local immune response renders the oral microenvironment conducive to osteonecrosis. We tested whether zoledronate (Zol) treatment impaired dendritic cell (DC) functions and increased bacterial load in alveolar bone in-vivo and whether DC inhibition alone predisposed the animals to osteonecrosis. We also analyzed the role of Zol in impairment of differentiation and function of migratory and tissue-resident DCs, promoting disruption of T-cell activation in-vitro. Results demonstrated a Zol induced impairment in DC functions and an increased bacterial load in the oral cavity. DC-deficient mice were predisposed to osteonecrosis following dental extraction. Zol treatment of DCs in-vitro caused an impairment in immune functions including differentiation, maturation, migration, antigen presentation, and T-cell activation. We conclude that the mechanism of Zol-induced osteonecrosis of the jaw involves disruption of DC immune functions required to clear bacterial infection and activate T cell effector response.

Keywords: Osteonecrosis, Dendritic cells, alveolar bone healing

INTRODUCTION:

Bisphosphonates (BP) are anti-resorptive drugs widely used in the treatment of osteoporosis and other bone-wasting conditions, such as Paget’s disease, multiple myeloma, and osteogenesis imperfecta (1, 2). One of the uncommon, yet severe, side effects of anti-resorptive medications, known as medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (MRONJ), has caused significant anxiety towards these otherwise useful medications, causing a sharp decline in their use (3, 4).

Unlike other anti-resorptive medications, BP, especially zoledronic acid (Zol) accumulate in the matrix of alveolar bone (5, 6), as well as other locations, for years following the suspension of systemic treatment (7). The highest risk of MRONJ has been reported in patients on high doses of intravenous Zol, and it remained high even after treatment cessation (8). Interestingly, medication-related osteonecrosis is limited to the jawbone and is often triggered by invasive dental procedure and/or periodontitis, suggesting that site-specific factors could be important for the pathogenesis.

While BPs are known to target primarily osteoclasts, immune cells of the same lineage, such as monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells, may also be affected (9). Studies have shown that BPs are taken up by these cells (10). Disruption of the local immune response in the unique microenvironment of alveolar bone may, therefore, contribute to the pathogenesis of osteonecrosis (11).

The oral mucosal barrier features a complex immune system that has to constantly recognize and eliminate pathogens while maintaining tolerance to commensals (12). Dendritic cells (DCs), the most efficient antigen-presenting cells in the immune system, have emerged as key players in initiating and regulating immune responses in the oral cavity (13, 14). Blood samples from melanoma patients receiving Zol treatment have shown defective DC differentiation and maturation (15). Breast cancer patients have shown alteration in their monocyte population, 48 hours after Zol administration (16). Furthermore, osteonecrotic jaw samples from patients have shown heavy colonization with multiple organisms, forming a complex biofilm (17, 18).

We hypothesized that Zol causes disruption of the local immune response in the oral cavity through the inhibition of DC differentiation and function, rendering the microenvironment more conducive to bacterial colonization and contributing to the pathogenesis of osteonecrosis. Our results showed that Zol treatment in the rat led to increased oral bacterial load and a significant decrease of antigen-presenting cells in the gingiva as well as draining lymph nodes. Differentiation, maturation, and functions of both human and rodent DCs were significantly compromised by Zol in-vitro, including phagocytosis, migration, and DC-dependent T cell stimulation. Results from DC-deficient mice confirmed that DC deficiency could predispose the alveolar bone to osteonecrosis following dental extraction. We concluded that DCs play an important role in maintaining the integrity of oral mucosa and alveolar bone and that Zol treatment disrupts such role, rendering the alveolar bone susceptible to subsequent osteonecrosis following dental extraction.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

MRONJ rat model and assessment of oral bacterial load in vivo:

The experimental procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at Augusta University (Protocol #2012–0496; Date: 10/25/2012). Twenty-six female Sprague-Dawley rats (ages 10–12 months) were treated with either intravenous Zol 80 μg/kg/week (experimental; n=13) or saline (control; n=13) for 13weeks, as previously described (5). After the last injection, oral swabs of oral mucosa were collected from both sides of the mandible using sterile cotton Q-tips in a circular motion for 30 seconds on each side (n=10 per group). Q-tips were immersed in DNA lysis buffer, and DNA was extracted using a DNA extraction kit (QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen). Total bacterial DNA was measured using universal 16srRNA qPCR using the CT values. Extractions of the mandibular 1st and 2nd molar were done on week 13. Cervical and submandibular lymph nodes were harvested 2 weeks post-extraction (n=3 per group). Mandibles were harvested 8 weeks post-extraction for mucosal and alveolar bone healing assessment (n=10 per group), and gingival tissues for immunolabelling of DCs (n=5 per group).

Immunohistochemistry (IHC):

IHC was done as previously described (19). Briefly, 5 μm sections of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue were de-paraffinized and rehydrated with ethanol. Antigen retrieval was done in water bath heating at 97° with citrate buffer PH6 (Thermofisher). Immune labeling was done using overnight incubation at 4° with anti ITGAX (CD11C) 1:20 dilution (Myebiosource, San Diego, USA) and anti MHCII 1:100 dilution (abcam, Cambridge, USA). Detection of the primary antibody was done with Horeseradish peroxidase (HRP) and Diaminobenzidine (DAB) substrate (Thermofisher). Multiple random photomicrographs were taken for each lymph node in the paracortex region and gingival tissues in the lamina propria, at 40x objective lens using Zeiss microscope (Zeiss AxioIma, Carl Zeiss Microscopy GmbH, Jena, Germany) and quantification was done blindly using automated Image-J software (https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/) with a set threshold based on the negative control.

Ablation of classical dendritic cells (cDCs) and extraction of maxillary molars in ZDC-DTR mice in vivo:

The experimental procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at Augusta University (Protocol #2013–0586, 10/11/2013). The ablation of cDCs was done as previously described (20). Briefly, C57BL/6 (B6) and Zbtb46 tm1(DTR)Mnz/J (ZDC-DTR) knock-in mice, 20–24 –week old, (Jackson Laboratory, Sacramento, CA) were injected intraperitoneally (i.p) with initial dose of 10ng/kg Diphtheria toxin (DT) (Sigma Aldrich, St Louise, MO, USA) or vehicle (PBS) 12 hours post extraction of maxillary 1st and 2nd molars, then a maintenance dose of 10 ng/kg was given every 3 days for 2 or 3 weeks. (n=5 per group). After 3 weeks, maxillae were harvested for assessment of alveolar bone healing by microcomputed tomography (micro-CT), gingival tissues were enzymatically digested for cell isolation, cervical lymph nodes were harvested and cells were immunolabelled for DCs and T cells to be analyzed by flow cytometry. Genotypic confirmation of ZDC-DTR mice was performed using PCR amplified genomic DNA from ZDC-DTR and WT mice electrophoresis in 2.5% agarose gel according to Jackson laboratory protocols with the following primers:

| 7443 | CTC CCC AGT CAC GAG TCA CA | Wild type Reverse | Reaction A | |||

| 17442 | AGG ATG AGG ATG AGG ACG TG | Common | Reaction A + B | |||

| oIMR7621 | ACC CCT AGG AAT GCT CGT CAA G | Mutant Reverse | Reaction B |

Micro-CT analysis:

Maxillae were scanned using 1272 skyscan System (Bruker, Belgium) at 12μm image pixel size with 0.5 mm Al filter, 0.2 rotation step and averaging frames of 3. 3-D reconstruction was done using NRecon software (Skyscan) and 3-D analysis of alveolar bone healing in maxillary first molar was done using CTAn software (Skyscan). Briefly, ROI of maxillary 1st molar socket was standardized in all samples by taking the cemento-enamel junction of the third molar as a start reference point till the end of the roots (30 slices) in an occluso-apical direction and from the mesial end of maxillary 2nd molar till the mesial end of maxillary 1st molar socket in mesio-distal direction. Greyscale images of the VOI were converted to binary images with a threshold set to 80–255. 3D volume of bone filling in the extraction socket was quantified as BV/TV %.

Uptake of FAM Zol by DCs in vivo:

C57BL/6 mice received an injection of 2.5ng FAM Zol (Biovinc LLC, CA, USA) into palatal gingiva using Hamilton micro syringe with 33 gauge and 10 ul loading capacity (Hamilton, NV, USA). Gingival tissue and cervical lymph nodes were harvested 24-hrs post-injection. Gingival tissues were enzymatically digested for cell isolation and labeled for DCs using anti-CD11c and anti-MHCII for flow cytometry analysis. Gingival frozen tissue sections were immune-labeled with CD11c antibody and visualized by confocal microscopy.

Uptake of Zol by DCs and macrophages in vitro:

Monocyte-derived DC and macrophages were incubated with 10 ng/ml OsteoSense 680 EX (Perkinelmer) at 37°C overnight, then stained with the nuclear stain NucGreen 488 and the membrane tracker rhodamine-conjugated Wheat Germ Agglutinin. Stained cells were mounted with anti-fade mounting medium (Vectashield; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA), cover-slipped and examined using a Leica TCS-SP2 AOBS confocal laser scanning microscope. Three lasers were used: 488nm for nuclear stain, 543nm for the cell membrane, and 647 for Osteosense. Parameters were adjusted to scan at 1024×1024 pixel density and 8-bit pixel depth. Emissions were recorded in three separate channels, and digital images were captured and processed using Leica Confocal and LCS Lite software (Leica Microsystems Inc., Bannockburn, IL, USA).

Generation and culture of Murine bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDCs):

Bone marrow cells were isolated from C57BL/6 mice (6–12 weeks old) as previously described (21). Briefly, cells were flushed from femurs and tibiae of mice under sterile conditions then allowed to differentiate in RPMI 1640 10% FBS with 20ng/ml GM-CSF and 20ng/ml IL-4 (Pepro Tech Inc, Rocky Hill, NJ, USA) at a density of 1×106 cells/ml and incubated at 5% CO2 and 37° for 8 days, changing the medium at day 3, and 6 with addition of fresh growth factors. DC phenotype was then confirmed by flow cytometry using CD11c, CD11b, MHCII, and CD86 markers and by the exclusion of macrophage using F4/80, CD68 markers, granulocytes using CD11b/LY6G(Gr-1) markers, and natural killer cells using CD94.

Generation and culture of human monocyte-derived dendritic cells (moDCs):

Monocytes were enriched from peripheral blood mononuclear cells from three healthy donors using Rossette Sep Monocyte enrichment cocktail through Ficoll separation (STEMCELL Technologies, Vancouver, Canada) as previously described (22). Purified monocytes were then differentiated in X-vivo15 medium (Lonza, Walkersville, MD, USA), with GMCSF 1000U/ml and IL4 1000U/ml (Pepro Tech Inc, Rocky Hill, NJ, USA) with the change of media every other day.

Generation and culture of human monocyte derived macrophages:

CD14 MicroBeads (130-050-201) from Miltenyi Biotec (Auburn, CA, USA) were used for isolation of monocytes. In brief, monocytes were isolated from gradient-separated peripheral blood leukocytes (PBLs) where the CD14+ cells were magnetically labeled with CD14 MicroBeads, then loaded onto a magnetic cell separation (MACS) columns placed in the magnetic field of a MACS Separator (Miltenyi Biotec). The magnetically labeled CD14+ cells were retained within the column, while the unlabeled cells were run through. After removing the column from the magnetic field, the magnetically retained CD14+ cells were eluted as the positively selected cell fraction. Binding of antibody to CD14 does not trigger signal transduction because CD14 lacks a cytoplasmatic domain. Monocytes were cultured for 5 days in medium enriched with 10% fetal calf serum containing 50 ng/ml M-CSF.

Treatment of DCs:

For murine BMDCs, Zol (0 μM, 1μM, 5 μM, or 10 μM) was either added to the medium before differentiation, at day 0 and day3 (treatment from day 0) or added after the completion of differentiation, at day6 (treatment at day 6). For Human moDCs, Zol (0 μM, 1μM, 5 μM, or 10 μM) was added once at day 0.

Apoptosis assay:

Cell apoptosis was assessed for cells with treatment from day 0 and treatment at day 6, using Annexin V and Propidium iodide PI (eBioscience, Thermofisher Scientific, West Columbia, SC, USA) staining and flow cytometry analysis.

Antibodies and Flow Cytometry:

Flow data were acquired using BD FACS DIVA software (BD Bioscience, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) on FACSCanto (BD bioscience). Flow data were analyzed by Flowjo software vs 10.2. Flow cytometry antibodies used; anti-mouse CD11c PerCp-cyanine5.5, PE; clone N418, MHC classII (I-A/I-E) APC; cloneM5/114.15.2, CD86(B7–2) PE; clone GL1, CD83 FITC; clone Michel-17, CD11b PerCP-Cyanine5.5; clone M1/70, LY-6G(Gr-1) APC; clone1A8-LY6g, CD94 FITC; clone 18d3, F4/80 PerCP-Cyanine5.5; clone BM8, CD68 PE; clone FA-11, CD3e PE; clone 145–2C11, CD4 APC; clone GK1.5, CD8 PerCP-Cyanine 5.5; clone 53–6.7, CD9 APC; clone eBioKMC8 (KMC8), CCR7 APC; clone 4B12. (affymetrix, eBioscience, Thermofisher Scientific, Waltham MA, USA) and Isotype controls; American Hamster IgG isotype control PE, FITC; clone eBio299Arm, Rat IgG2b Isotype control PE; clone eB149/10H5, Rat IgG2b K Isotype control APC; clone eB149/10H5, Rat IgG2a K Isotype control APC, FITC, Percp-cyanine5.5; clone eBR2a (affymetrix, eBioscience, Thermofisher Scientific, Waltham MA, USA). Unconjugated CD11c monoclonal antibody; clone N418 (Thermofisher Scientific, Waltham MA, USA). Rabbit anti Hamster IgG (H+L) secondary antibody TRITC conjugate. (Thermofisher Scientific, Waltham MA, USA)

Rt-PCR:

RNA isolation was done as described previously (23). Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) was performed using iTAQ universal probe supermix (BIO-RAD, Hercules, CA,USA) and Taq-Man Gene Expression assay (Applied Biosystem, Foster City, CA, USA) specific for IL-6 assay (Mm00446190_m1), IL-12b (Mm01288989_m1), IL-23a (Mm00518984_m1), IL-10 (Mm01288386_m1), IFN-g (Mm1950217_m1), CD9 (Mm00514275_g1), H2-Ab1 (Mm00439216_m1), and internal control Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH Mm99999915_m1). RT-PCR was run in StepOnePlus™ Real-Time PCR System. Relative gene expression was calculated using delta-delta CT and plotted as relative fold change.

Bacterial culture:

Wild-type Porphorymonas gingivalis (P.gingivalis) 381 (ATCC) was grown and maintained anaerobically (10% H2, 10% CO2 and 80% N2) in a Coy Laboratory vinyl anaerobic system glovebox at 37°C in Wilkins-chalgren anaerobe broth.

Phagocytosis assay:

The uptake of P. ginigivalis was assessed in immature DCs treated with Zol (0 μM, 5μM, or 10μM) at day 7 of culture. Bacteria were stained with 10μM carboxyfluoresceine succinimidyl ester (CFSE ebioscience, Invitrogen, Thermofisher Scientific West Columbia, SC, USA) for 1 hour at 37° with shaking, followed by thorough washing for 3 times. 5×105 DCs were infected with CFSE stained bacteria at 30 MOI and incubated at 37° for 6 hours in serum-free media. Negative controls were incubated on ice at 4° or in the presence of Cytochalasin D (Sigma Aldrich, St Louise, MO, USA) to exclude any bacteria on the external surface of the cell. Cells were then washed and stained with anti CD11c antibody for DC gating and analyzed by flow cytometry. Confirmation of the P.gingivalis uptake by DCs was done using confocal microscopy, by fixation of cells with 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilization with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS and staining of cells with actin ActinRed™ 555 ReadyProbes™ Reagent and nucleus with DAPI mounting medium; ProLong™ Gold Antifade Mountant (Invitrogen, Thermofisher scientific, Waltham MA, USA), then images were taken using Zeiss 780 upright confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss AG, Oberkochen, Germany).

FITC dextran macropinocytosis assay:

On day 7, immature DCs treated with Zol (0 μM, 1μM, 5μM, or 10μM) were washed and re-suspended in PBS. FITC dextran 70,000 mwt (Sigma Aldrich, St Louise, MO, USA) was added (1mg/ml) for 1 hour at 37° or 4° (negative control). Uptake was then stopped by adding ice-cold PBS with 2%FBS and 0.01 % NaN3. After this, cells were washed 3 times, stained with anti CD11c antibody for gating of DCs and analyzed by flow cytometry. The amount of uptake was measured by subtracting uptake at 4 ° from 37 ° to exclude any FITC dextran on the surface of the cell. FITC percentage and MFI of FITC dextran were measured in the CD11c positive cells.

DCs maturation:

To induce DCs maturation, 100 ng/ml lipopolysaccharide from Escherichia Coli (LPS E Coli; Sigma Aldrich, St Louise, MO, USA) was added to immature DCs on day 7 for 24 hours.

Migration assay:

Migration assays were performed according to manufacturer instructions using the 96-Well Fluorimetric Cell Migration Assay kit (CytoSelect; Cell Biolabs, San Diego, CA, USA). Briefly, cells treated with Zol (0 μM, 1μM, 5μM, or 10μM) were stimulated with LPS at day 7 for 24 hrs and then seeded into the upper chamber of the trans-well plate on top of a 5 μm pore membrane at a density of (1×105 /well). The lower chambers received increasing doses of chemokine-CC motif-ligand 19 [0ng/ml, 50ng/ml, 100ng/ml, or 500ng/ml] (CCL19/MIP-3beta; Pepro Tech Inc, Rocky Hill, NJ, USA). The plates were incubated for 18 hours at 37° and 5% CO2. The migrated cells were lysed and quantified by CyQUANT GR fluorescent dye using a fluorescence microplate reader (BioTek, Northern Vermont, USA).

DC morphology by scanning electron microscopy (SEM):

On day 7, immature DCs with or without Zol were seeded onto acid-washed Poly-L- lysine coated coverslips to allow for cell attachment in a 12 well plate. Then, LPS (100ng/ml) was added to the medium. After 24 hours, coverslips were washed with PBS, and DCs were fixed using 2% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4) overnight at 4–8 °C, and post-fixed in 2% osmium tetroxide in NaCac buffer and dehydrated in ethanol. The dried coverslips were mounted on aluminum stubs with carbon adhesive tabs and sputter-coated 6 minutes with gold-palladium (Anatech Hummer™6.2, Union City, CA). Cells were observed and imaged at 10 kV using an FEI XL30 scanning electron microscope (FEI, Hillsboro, OR).

Antigen presentation and T cell activation:

OVA antigen-specific T cells were isolated from OT-II transgenic mice using negative selection with Mouse T-cell Enrichment Kit (MagniSort; Thermofisher Scientific, West Columbia, SC, USA). T cell purity was assessed by flow cytometry analysis, using anti CD3, CD4, and CD8 antibodies. T cells were stained with 0.5 μM CFSE for 15 minutes at 37°, after which cells were washed 2 times. Zol pre-treated DCs (0 μM, 5μM, or 10μM) were pre-pulsed with 3ug/ml OVA323–339 peptide ISQAAVHAAHAEINEAGRE (Synthetic Biomolecules, San Diego, CA) for 24 hours, thoroughly washed and then co-cultured with T cells at 1:10 DC: T cell ratio in 96-well round-bottom plates with complete RPMI 1640 (10% fetal bovine serum FBS,1% Pen Strep, 1x non- essential amino acids, 0.1% b-mercaptoetanol). After a 72-hr incubation at 37°C with 5% CO2, the proliferation of CFSE-labeled CD4+ T cells was then assessed by flow cytometry. T cell activity was also assessed by measuring secreted IFN-γ and IL-2 in the supernatants using the Quantikine ELISA Kit (R&D, Minneapolis, MN, USA). For direct T cells stimulation, 96 round-bottom plate was coated and incubated overnight at 4° with 10μg/ml anti-CD3 antibody (Invitrogen, Thermofisher Scientific West Columbia, SC, USA). The plate was then washed twice with PBS and CFSE-stained T Cells were added to the plate in complete RPMI 1640 media containing 10μg/ml anti CD28 antibody (Invitrogen, Thermofisher Scientific West Columbia, SC, USA) and incubated at 37° and 5% CO2 for 72 hours. T cell proliferation was assessed by flow cytometry by gating on the CD4-positive cells.

Transfection of siRNA into DCs:

Transfection of siRNA was performed as described previously (24). Briefly, at day 6 of culture, DCs were washed at 4° with reduced Minimal Essential Medium (Opti-MEM) (Gibco, Thermofisher Scientific, Waltham MA, USA), then re-suspended in Opti MEM at 40 × 106 cells/mL. Transfection was performed in 4 mm cuvette (Fisher Scientific, Thermofisher Scientific, Waltham MA, USA), using 20 μM CD9 siRNA (OriGene, Rockville, MD, USA) in a100 μL of siRNA-cell suspension containing 2 × 10 6cells. The electroporation took place in a Gene Pulser Xcell™ (BIO-RAD, Hercules, CA, USA). Pulse conditions are 400V (volts), 150 μF (Farad), and 100 Ω (ohms).

Statistical analysis:

Statistical analysis was done using Graph Pad Prism software version 6 (Graph Pad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). In-vitro experiments were repeated at least three times. Data values were reported as means ± SD. Normality assumption was evaluated when applicable, using the Shapiro-Wilk test. When normality assumptions were not met, an alternative non-parametric test was done. A one-way ANOVA test with significance defined as p < 0.05, a confidence level of 95% confidence interval and Bonferroni post-hoc comparison was used to compare multiple groups. Unpaired T-test was used to compare 2 groups in the in vivo experiments.

RESULTS:

Impaired DC activity and increased oral bacterial load in MRONJ rat model:

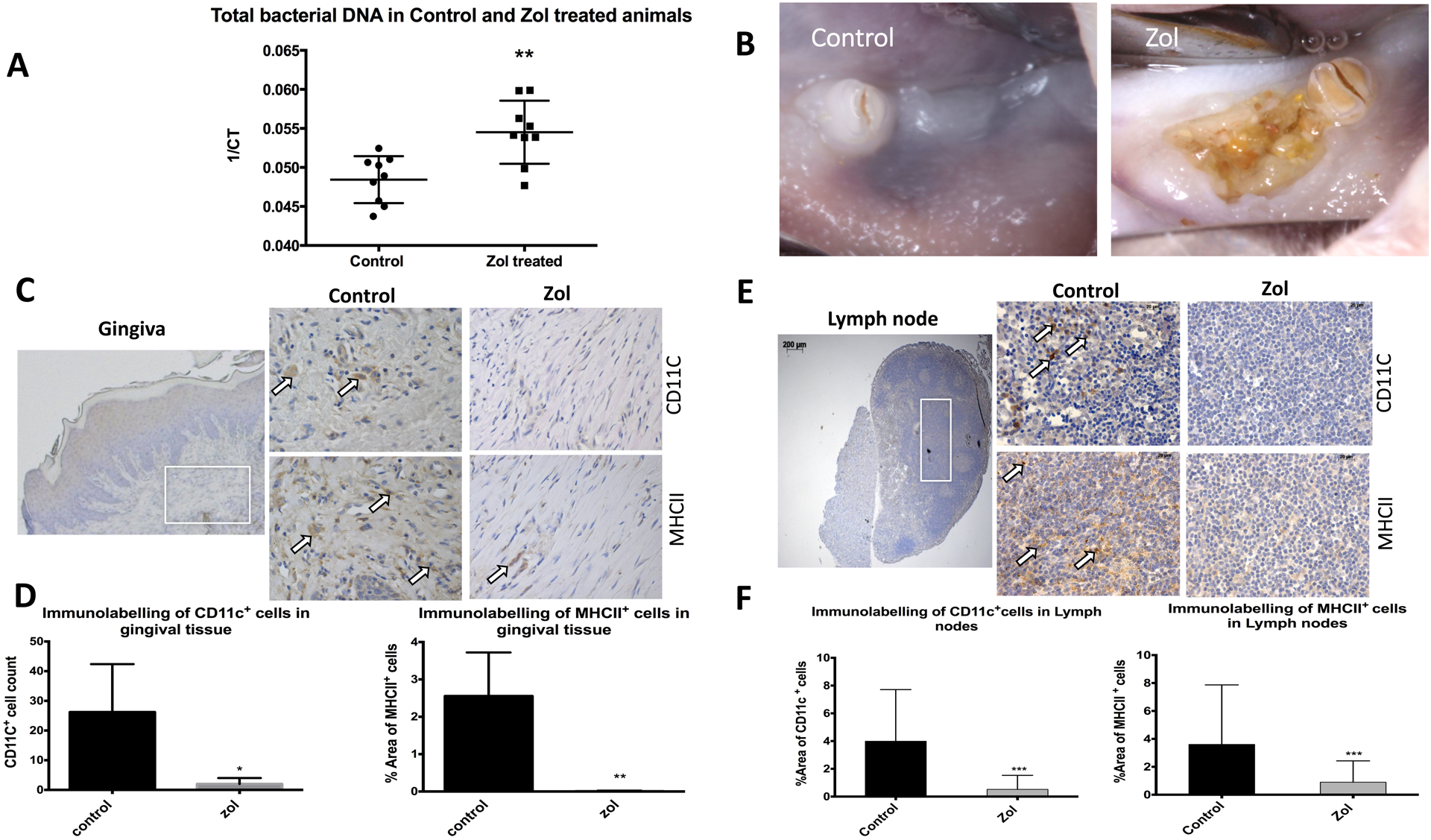

Previous studies have shown that MRONJ lesions were heavily colonized with bacteria (17, 18). However, little is known about the effect of Zol treatment on oral bacterial colonization before dental extraction. Therefore, oral swabs were collected for analysis of bacterial content from the oral mucosa of control or Zol treated rats (80ug/kg Zol for 13 weeks)(5). This was followed by extractions of 1st and 2nd mandibular molars. Oral swabs showed an increase in bacterial 16s rRNA expression (p=0.0023; Fig. 1A). Consistent with our previous studies (5, 23), Zol-treated animals showed exposed necrotic bone, persistent for 8 weeks after extraction, compared with complete healing and mucosal coverage in control animals (Fig.1B). To study the effect of Zol on DC activity, isolation of cervical lymph nodes was performed at 2 weeks, and harvest of mandibles and gingival tissues at 8 weeks following extraction. Gingival tissues of Zol-treated rats showed a significant decrease in DC number in the lamina propria area, evident by a decrease in the CD11c-positive cell count and MHCII-positive area fraction by immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis, (p< 0.0001, p=0.0083 respectively; Fig. 1C& D). There was also a significant decrease in DC number in the paracortex area of submandibular lymph nodes of Zol-treated rats, using the same markers, (p< 0.0105, p=0.0012 respectively; Fig. 1E& F).

Fig 1: Zol impaired DCs’ activity in vivo leading to increased bacterial load in MRONJ rat model:

Rats were treated with 80ug/kg Zol for 13 weeks (n=13 per group), oral swabs were taken for analysis of bacterial content followed by extractions of 1st and 2nd mandibular molars and isolation of cervical lymph nodes 2 weeks post extraction (n= 3 per group) and harvest of mandibles (n=10 per group) and gingival tissues (n=5 per group) 8 weeks after extraction. A: Universal 16SrRNA qPCR showing difference in bacterial content on oral mucosa of Zol and control animals; gene expression of the 16srRNA was assessed with the CT values and graph plotted as I/CT on the y-axis. B: Representative clinical pictures of extraction sites (8 weeks post extraction) of Zol and control animals. C: IHC labeling of DCs in gingival tissues using anti CD11c and anti MHCII in consecutive sections (2.5x photomicrograph of the gingival tissue was taken to show the area of analysis in lamina propria as indicated by white box, which was further magnified at 40x) and quantified using ImageJ software as shown with bar graphs in D. E: IHC labeling of DCs in cervical lymph nodes using anti CD11c and anti MHCII in consecutive sections, (2.5x photomicrograph of the lymph node was taken to show the area of analysis in paracortex as indicated by white box, which was further magnified at 40x) and quantified using ImageJ software as shown bar graphs in F. (* p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001)

Impaired post-extraction alveolar bone regeneration in DC-deficient mice:

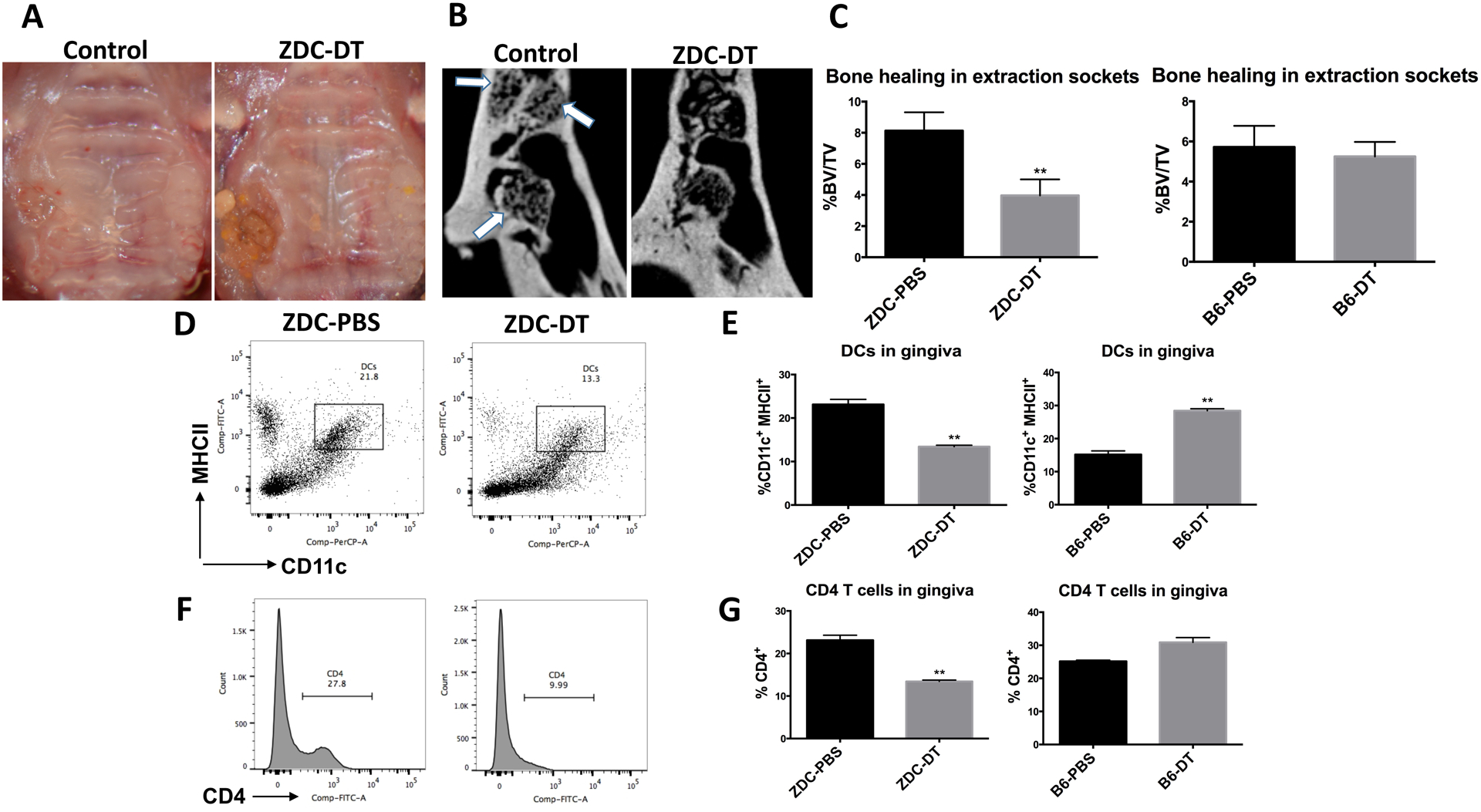

To test whether the DC inhibition can contribute to osteonecrosis, we performed maxillary molar extraction in DC-deficient mice (ZDC-DTR; Fig. S1). The regimen and dosing used have previously been shown to spare neutrophil counts (20). ZDC-DTR and B6 mice received intraperitoneal (i.p) injection with 10ng/kg diphtheria toxin (DT) (ZDC-DT and B6-DT respectively), or vehicle (ZDC-PBS and B6-PBS respectively) 12 hours post-extraction and every 3 days as a maintenance dose for 2 or 3 weeks. Maxillae, gingival tissues, and cervical lymph nodes were harvested 2 or 3 weeks post-extraction. At two weeks following the extraction, mucosal healing was deficient in ZDC-DT compared to control (Fig. 2A). The epithelium recovered at week 3; however, the underlying bone was deficient in DCs-ablated mice by micro-CT analysis (Fig. 2B). Bone volume at the extraction socket of maxillary 1st molar showed a significant decrease in the ZDC-DT group compared to ZDC-PBS group (P=0.0019), while there was no significant difference in the B6 mice injected with either DT or vehicle. (Fig. 2C). Disruption in the DC population in gingival tissues in ZDC-DT animals was confirmed by flow cytometry (p=0.0002; Fig. 2D & E). Interestingly, there was an increase in DCs in B6-DT compared to B6-PBS (p=0.0001), suggesting that DT toxin by itself may stimulate DC in wild-type animals. A similar pattern was observed with T cell population, where CD4+ T cell population increased upon DT injection in B6 mice, but significantly decreased with DT injection in ZDC-DTR mice (p=0.0307 and p=0.0002, respectively; Fig. 2F, &G). Similar results were found in the draining cervical lymph nodes (Fig S1). Collectively, our data indicate that DC deficiency could lead to impaired dental socket healing following dental extraction, suggesting an important role in alveolar bone healing. Inhibition of DC functions by Zol, as shown in subsequent results, may, therefore, contribute to the pathogenesis of osteonecrosis.

Fig 2: Impaired healing of alveolar bone extraction sockets in DC-ablated mice:

ZDC-DTR and B6 mice were injected i.p with DT (10ng/kg) or vehicle 12 hours post extraction and every 3 days as a maintenance dose for 2 or 3 weeks. Maxillae, gingival tissues and cervical lymph nodes were harvested 3 weeks post extraction. A: Representative clinical pictures of mucosal healing of extraction sockets in ZDC-DT mice and control mice 2 weeks post extraction. B: Representative μCT sections showing bone healing in the extraction socket of maxillary 1st molar (arrows pointing to the sockets of 3 roots). C: 3D analysis of bone volume in the extraction sockets, data are presented as BV/TV% (n=5 per group). D: Flow cytometry plots showing difference in the DCs population in gingiva of ZDC-DTR mice injected with DT or vehicle, gingival tissues were enzymatically digested and cells were stained with anti CD11c and anti MHCII and analyzed by flow cytometry. E: Graphs demonstrating the % of CD11c+ MHCII+ population in gingiva of either ZDC-DTR or B6 mice injected with DT or vehicle. F: Flow cytometry histograms showing difference in CD4 T cells in gingiva of ZDC-DTR mice injected with DT or vehicle. G: Graphs demonstrating the % of CD4+ T cell population in gingiva of either ZDC-DTR or B6 mice injected with DT or vehicle. (Experiment was repeated twice and data represent means of tissues pooled from five mice per group ± SD * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001)

Zol is taken up by DCs in-vivo and in-vitro:

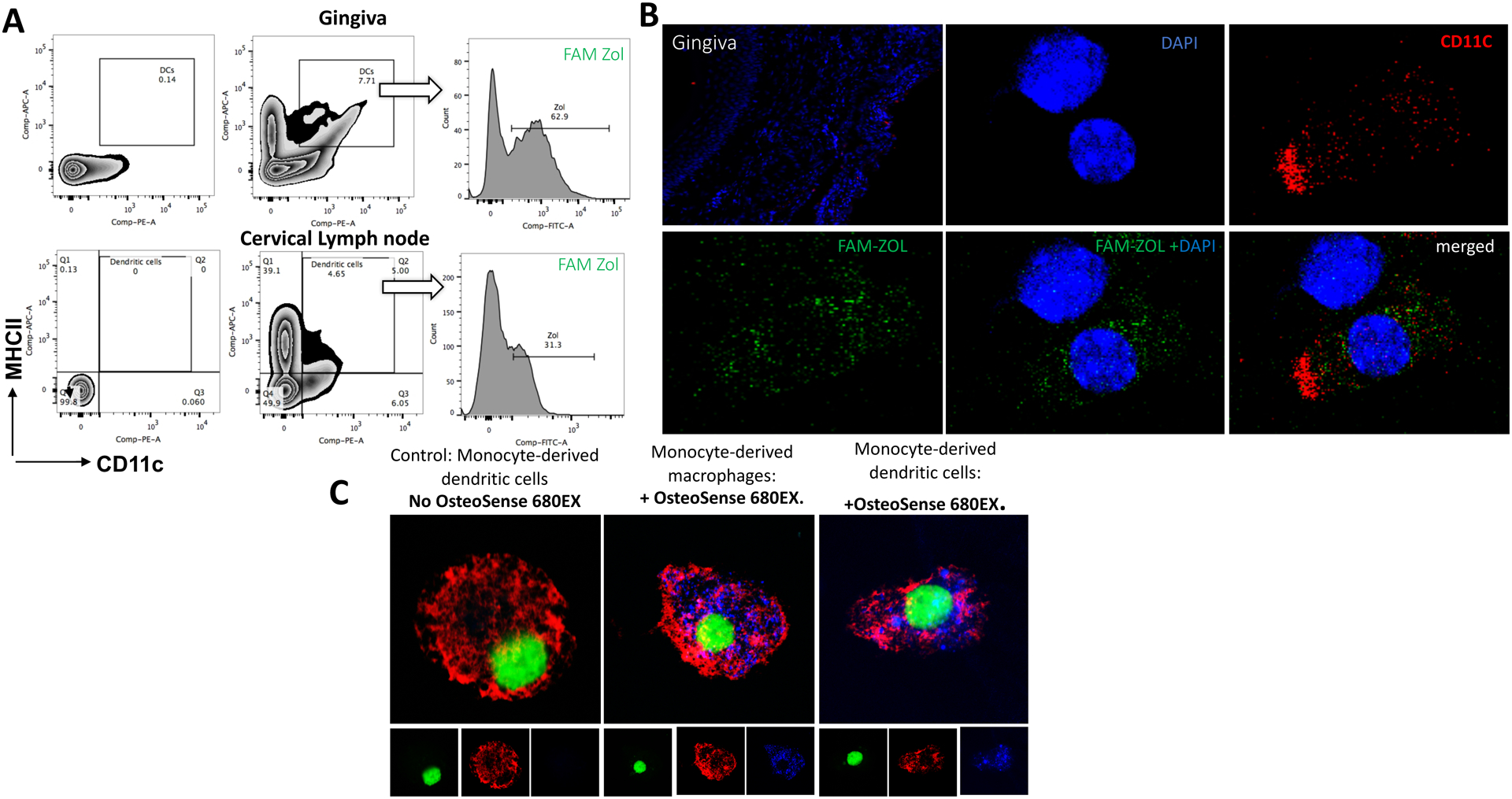

To investigate the mechanism by which Zol impairs DCs, we first confirmed that Zol is taken up by DCs both in-vitro and in-vivo. C57BL/6 mice received an injection of fluorescent Zol (FAM Zol; 2.5ng) into palatal gingiva. Gingival tissue and cervical lymph nodes were harvested 24 hrs post-injection and FAM Zol was detected in DC population (CD11c+/MHCII+) by flow cytometry analysis (Fig. 3A). The uptake was further confirmed in gingival frozen tissue sections immunolabelled with CD11c (red) and visualized by confocal microscopy showing zol (green) inside the DCs (red) (Fig. 3B). We also confirmed the uptake of Zol by DCs and macrophages in vitro (Fig. 3C).

Fig 3: Zol uptake by DCs in vivo and invitro:

C57BL/6 mice received injection of FAM Zol (2ng) into palatal gingiva using Hamilton micro syringe with 33 gauge and 10 ul loading capacity. Gingival tissue and cervical lymph nodes were harvested 24-hrs post injection and cells were labelled for DCs using anti CD11c and anti MHCII for flow cytometry analysis and gingival frozen tissue sections immunolabelled with CD11c and visualized by confocal microscopy. A: Flow cytometry plots showing gating of cells on DCs population (CD11c+ MHCII+) and detection of FAM Zol within the DCs gate in gingival cells (upper panel) and cervical lymph node cells (lower panel). B: confocal microscopy images showing the uptake of FAM Zol (green) into DCs immunolabelled with CD11c (red) and nucleus labelled with DAPI (blue). C: Confocal microscopy images showing Uptake of Zol by human monocyte derived DCs and macrophages in vitro; nucleus in green color, Rhodamine-conjugated Wheat Germ Agglutinin –Membrane Tracker in red and osteosense 680EX (Zol) in blue.

Zol impaired the differentiation and phagocytic capacity of murine bone marrow-derived dendritic cell (BMDCs):

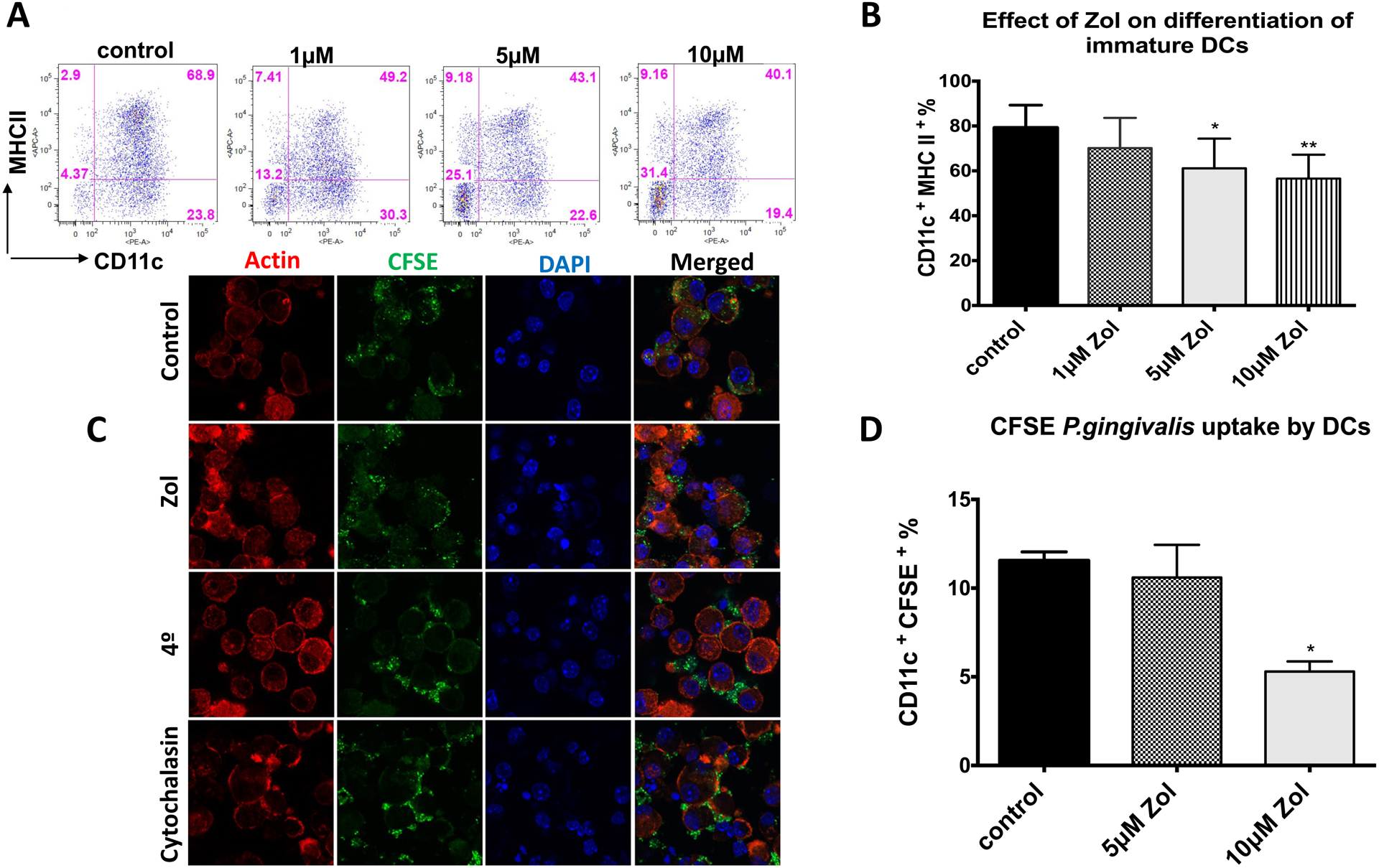

We have demonstrated the decreased DC number in gingival tissues and cervical lymph nodes in Zol-treated rats. To better understand if this decrease can be due to a decrease in the differentiation of DCs from its precursors, we tested the effect of Zol on the differentiation of DCs. The phenotype of DCs generated from murine bone marrow was first confirmed (Fig S2). Results showed a dose-dependent inhibition of DC differentiation, evident by the decrease in the % of CD11c+ MHCII+ in flow cytometry analysis at 5μM and 10μM Zol (p= 0.0153, 0.0021, respectively; Fig 4A, B). These results were consistent with that observed in human monocyte-derived dendritic cells (moDCs; Fig S3. A, B). AnnexinV assay showed no significant difference in apoptosis between control and all doses of treatment used in this study (Fig S3E), suggesting that the effect of Zol was mostly due to specific inhibition of DC differentiation and maturation, rather than killing the cells. Furthermore, we tested the effect of Zol on phagocytic capacity of murine BMDCs by infecting cells with CFSE labeled Porphorymonas gingivalis (P.gingivalis), one of the most common periodontal pathogens, at 30 MOI for 6 hrs. Flow cytometry analysis showed a significant decrease in phagocytosis (p=0.0243; Fig. 4C, D). Macropinocytosis was also not significantly inhibited by Zol treatment, although a trend was observed (Fig S3 C, D). These findings lent support to the hypothesis that increased bacterial load in-vivo could be attributed to defective bacterial clearance by DCs.

Fig 4: Zol impaired the differentiation and phagocytic capacity of murine BMDCs:

Bone marrow cells were isolated from C57BL/6 mice (6–12 weeks old) and differentiated into DCs using 20ng/ml GM-CSF and 20ng/ml IL-4 with Zol treatment (0μM, 1μM, 5μM, 10 μM). Cells were harvested at day 8 and analyzed by flow cytometry for differentiation markers using anti CD11c and anti MHCII or infected with CFSE labelled P.gingivalis at 30 MOI for 6 hrs and analyzed by flow cytometry and confocal microscopy to assess the phagocytic capacity of DCs. A, B: Flow cytometry analysis of BMDCs differentiation showing % of CD11c+MHCII+ population in representative FACS plot and its corresponding bar graph. C: Representative confocal microscopy images showing internalization of CFSE stained P.gingivalis into control or Zol treated DCs incubated at 37° or 4° or in the presence of Cytochalasin D, images taken at 40x, red color indicates actin, blue; nucleus and green; P.gingivalis D: FACS analysis of CFSE-stained P.gingivalis uptake by control or Zol treated DCs at 37° normalized to its negative control at 4°. (* p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001)

Zol impaired maturation and migratory capacity of murine BMDCs:

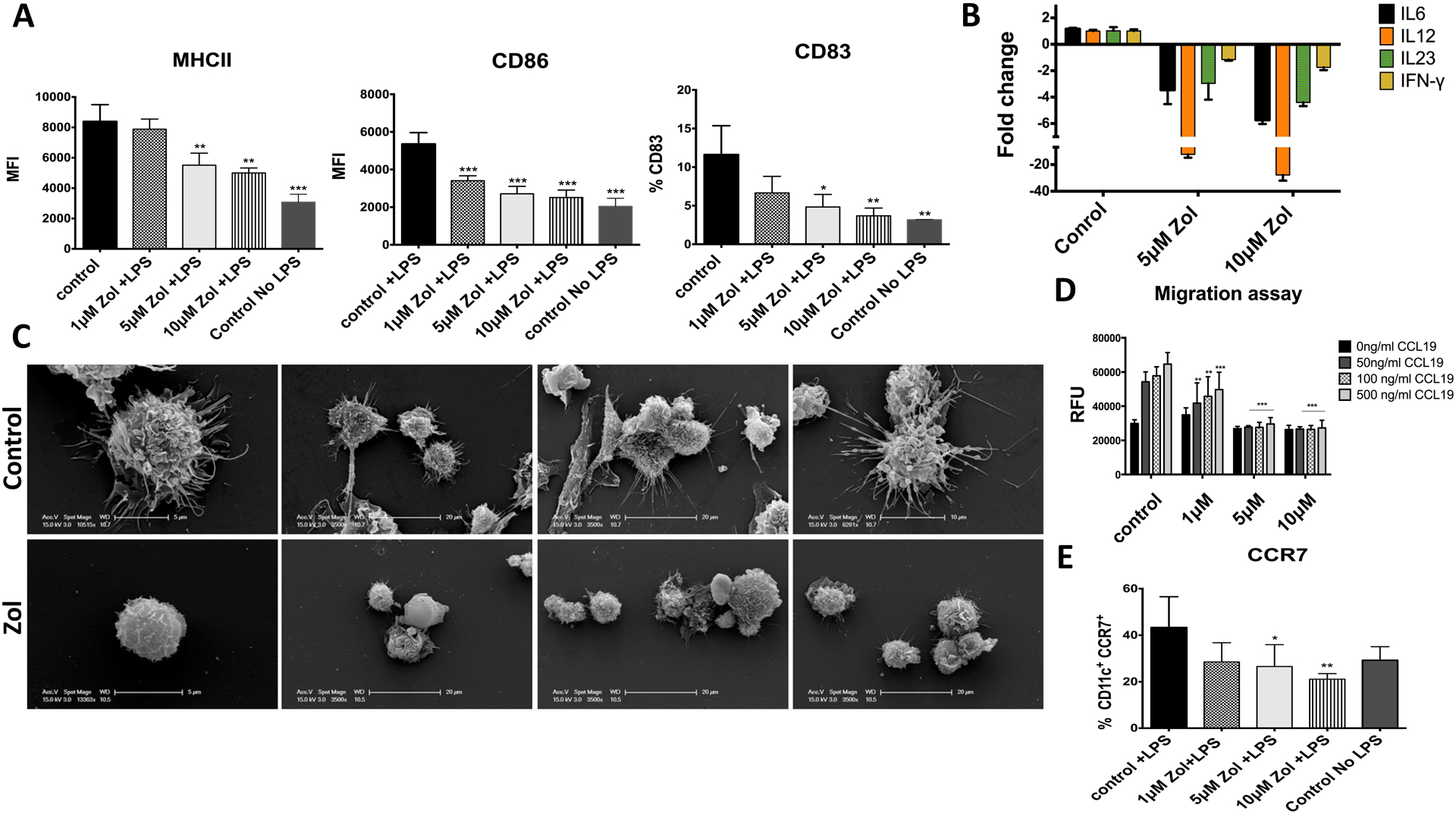

Since DCs’ ability to migrate is one of the key features that distinguished DCs from other antigen-presenting cells (APCs), and is critical for the initiation of an immune response, we tested the effect of Zol on maturation and migratory capacity of DCs. Results showed that Zol inhibited the lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced DC maturation, evident by deficient expression of MHCII and costimulatory molecules CD86 and CD83 by flow cytometry analysis (Fig. 5A), as well as downregulation of inflammatory cytokines, IL-6, IL-12, IL-23, and IFN-g by gene expression analysis (P<0.05; Fig. 5B). A dose-dependent decrease was consistent whether Zol was added at day 0 or day 6 of culture, evident by the decrease in % of CD11c+ MHCII high population and MFI of MHCII and CD86 (P<0.05; Fig. S4 A, B, C, D). Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis showed defective dendrite formation in Zol-treated DCs (Fig. 5C). Maturation of DCs involves the upregulation of CCR7 expression, which enables them to migrate towards CCL19 and CCL21 in the draining lymph nodes. Migration of LPS-induced DCs towards a concentration gradient of CCL19 was deficient (Fig. 5D), at 1μM Zol with 50, 100 and 500ng/ml concentration of CCL19 compared to control group (p=0.0038, 0.0016, and <0.0001, respectively), and at 5μM and 10μM Zol (p<0.0001) with all CCL19 concentrations, compared to control. There was also a decrease in the % of CD11c+ CCR7+ cells at 5μM, and 10μM Zol (p=0.0357, 0.0045, respectively; Fig. 5E). (Flow cytometry plot is included in Fig. S4E).

Fig 5: Zol impaired maturation and migratory capacity of murine BMDCs:

LPS E-Coli (100 ng/ml) was added to differentiated DCs on day 7 for 24 hours. DC maturation markers were assessed using anti anti MHCII, anti CD86 and anti CD83 and analyzed by flow cytometry. Inflammatory cytokine release was assessed using qPCR and migratory capacity was analyzed using trans-well plate towards concentration gradient of CCL19 as a chemoattractant. A: Flow cytometry analysis showing expression of MHCII, CD86 and CD83 in LPS stimulated DCs. B: qPCR showing relative fold change in inflammatory cytokines, IL-6, IL-12, IL-23 and IFN-g. C: Representative EM images of control of Zol treated DCs after LPS stimulation. D: Trans-well migration assay showing migratory capacity of mature DCs towards different concentrations of CCL19 ligand. E: graph showing flow cytometry analysis of CCR7 receptor expression upon LPS maturation in Control and Zol treated DCs shown as % of CD11C+ CCR7+ cells. . (* p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001)

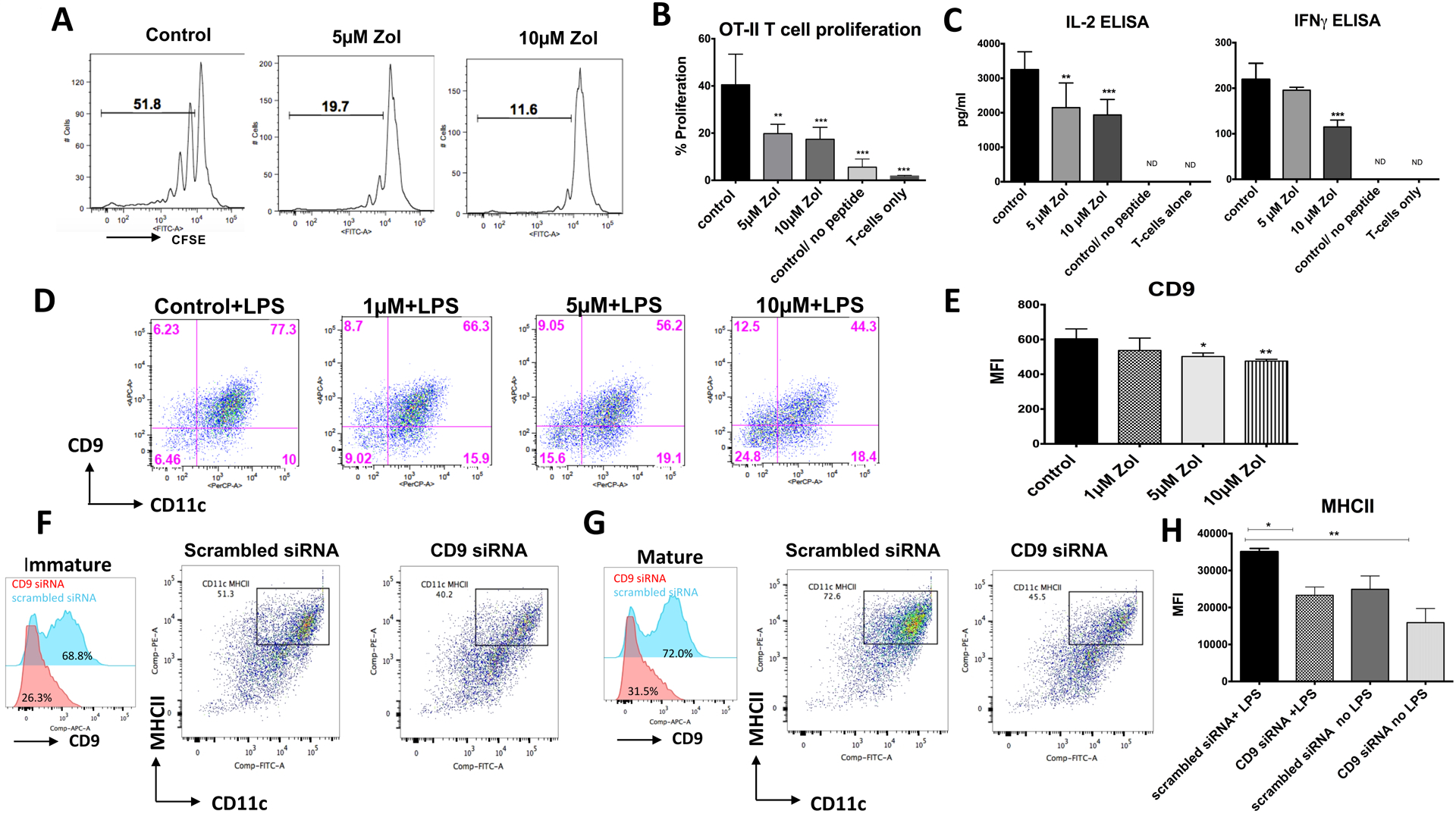

Zol compromised DC-induced T cell activation:

Next, we tested the effect of Zol on the immunogenicity of DCs and their ability to stimulate T cells. Zol-treated murine BMDCs were pre-pulsed with OVA323–339 peptide for 24 hrs prior to co-culture with OTII derived T cells that are specific for OVA antigen. The purity of T cells was >90% (Fig. S5A). Flow cytometry analysis was performed by gating on CD4+ T cells (Fig. S5B). Zol impaired DC-dependent T cell proliferation and activation, at 5μM and 10μM Zol (p=0.0132, 0.0071, respectively, Fig. 6A, B), confirmed with a decreased T cell secretion of IL-2 (p=0.0018, 0.0003; and IFN-γ (NS, p=0.0002) at 5μM and 10μM Zol, respectively (Fig 6C). Importantly, there was no direct effect of Zol on T cell proliferation, tested using anti CD3/CD28 antibodies (Fig. S5 C, D), confirming that Zol-induced deficiency of T cell function, in this case, is DC-dependent. Previous studies have shown the critical role of tetraspanin, CD9 in the trafficking and association of MHCII on the surface of DCs (25, 26). Thus, we investigated the impact of Zol on CD9 expression on DCs surface. Our data showed a decrease in the % population double-positive cells for CD11C and CD9 (Fig.6D), and MFI of CD9 within DCs (Fig. 6E), at 1μM, 5μM and 10μM (p=0.0258, 0.0026, 0.0009, respectively). To test the effect of a decrease in CD9 expression on maturation and antigen presentation of DCs, we knocked down CD9 expression using siRNA. Transfection was confirmed with fluorescently-labeled siRNA (Fig. S5E), with a knock-down of CD9 by more than 90% by qPCR (Fig. S5G) and flow cytometry (Fig. S5F). Knocking down the CD9 in DCs, led to a decrease in MHCII expression as shown by flow cytometry analysis in both immature (Fig.6F) and mature DCs (Fig.6G) with statistical significance in mature DCs (p=0.0142; Fig.6H). These results suggest that impaired MHCII expression and defective antigen presentation by Zol involves disruption of CD9 expression.

Fig 6: Zol disruption to tetraspanin CD9 leads to impaired MHCII expression, impaired antigen presentation and DC-dependent T-cell activation:

At day 6 of culture Zol treated DCs (0 μM, 5μM, or 10μM) were pre-pulsed with 3ug/ml OVA peptide for 24 hours, thoroughly washed and then combined with T cells at 1:10 DC: T-cell ratio. After a 72-hr, the proliferation of CFSE-labeled CD4+ T cell was assessed by flow cytometry. T cell activity was also assessed by measuring secreted IFN-γ and IL-2 in the supernatants using ELISA. A, B: Flow cytometry analysis showing % of T cell proliferation after co-culture with OVA pulsed DC pretreated with Zol or DCs with no OVA peptide or no DCs (T cells only) C: ELISA of secreted IL-2 and IFN-g in the supernatant of activated T cells. D: Representative Flow cytometry plot showing CD9 expression by DCs as represented with % of CD11C+CD9+ in the upper right quadrant of the plots. E: Graph showing flow cytometry analysis of MFI of CD9 in DCs. F: Left panel: Flow cytometry histograms showing CD9 knock down in immature DCs using siRNA transfection (CD9 siRNA shown in red histogram and scrambled non-specific siRNA shown in blue histogram), Middle Panel: Flow cytometry plots showing MHCII surface expression in immature DCs transfected with scrambled siRNA. Right Panel: Flow cytometry plots showing MHCII surface expression in immature DCs transfected with CD9 siRNA. G: Left panel: Flow cytometry histograms showing CD9 knock down in mature DCs using siRNA transfection (CD9 siRNA shown in red histogram and scrambled non-specific siRNA shown in blue histogram), Middle Panel: Flow cytometry plots showing MHCII surface expression in mature DCs transfected with scrambled siRNA. Right Panel: Flow cytometry plots showing MHCII surface expression in mature DCs transfected with CD9 siRNA. H. Graph showing MHCII expression in immature and mature DCs transfected with CD9 or control siRNA.

(* p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001)

DISCUSSION:

The main therapeutic mechanism of anti-resorptive medications is osteoclast inhibition (1, 2). Such mechanism, and others confirmed in the literature (27), are all systemic and could explain why alveolar bone is uniquely susceptible to osteonecrosis associated with anti-resorptive medications. In our studies, we focused on Zol, since it is associated with the highest incidence of osteonecrosis, which remains high long after treatment has stopped. Zol is known to have the highest affinity to the bone matrix, where it accumulates for years (1). We previously showed that matrix-bound Zol molecules play an important role in making the alveolar bone susceptible to osteonecrosis (23). However, the question remained as to why other bone sites that have similarly high levels of matrix-bound Zol, such as the proximal end of the tibia, are not comparably vulnerable. Our studies showed that even with significant trauma to the proximal tibia in Zol-treated animals, osteonecrosis could not be induced there (data not shown). Other factors unique to the oral micro-environment must, therefore, be investigated.

Previous studies reported deficient innate immune response, as well as colonization of unique oral bacterial communities, in patients afflicted with bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (17, 18). Dendritic cells, the most efficient antigen-presenting cells, and the link between innate and adaptive immunity, have emerged as key players in initiating and regulating adaptive immune responses in the oral cavity (1, 2). They play a major role in the oral mucosal barrier immunity in the oral cavity and the gut mucosa (3), preserving the balance between immune surveillance against pathogens and at the same time maintaining tolerance towards commensals, hence their major role in oral diseases, such periodontitis (2, 4).

On the other hand, DCs are not thought to play a role in normal bone remodeling in appendicular skeleton (5, 6). Disruption of DCs functions may, therefore, be a localizing factor that makes the jawbones more susceptible to osteonecrosis than long bones, especially within a background of invasive dental trauma and/or chronic periodontitis. Such “localized” immune-suppression, added to the already high bacterial load in the oral cavity, high levels of matrix-bound bisphosphonates in alveolar bone (7), dental trauma, and osteoclast inhibition, may provide a clue as to why MRONJ is exclusive to the jawbone. We hypothesized that Zol causes disruption of the local immune response in the oral cavity through the inhibition of DC differentiation and function, rendering the microenvironment more conducive to bacterial colonization and subsequent osteonecrosis.

Our in-vivo results showed that Zol impaired DC infiltration in the gingival lamina propria, as well as the draining lymph nodes, following dental extraction. Zol-treated animals had impaired bacterial clearance in the oral cavity. DCs, which can be exposed to Zol through the crevicular fluid, or possibly following the release of matrix-bound molecules after dental extraction, were shown to internalize these molecules.

Results in DC-deficient mice confirmed that DC deficiency could contribute to osteonecrosis following dental extraction. Tissue-resident DCs have been previously shown to have an important role in alveolar bone loss, demonstrated in the Langerhans-ablated mice model (Langerin –DTR) (30). We used a classical dendritic cell (cDCs) ablation mouse model, in which a DTR transgene is inserted into the 3’ untranslated region of the Zbtb46 (ZDC) gene (ZDC-DTR). Zbtb46 gene expression was shown to be limited to cDCs and distinct activated monocytes and is not expressed by pDCs, macrophages or other immune cells (31). To minimize the off-target effect on other erythroid progenitor cells (31), we previously optimized the dose of DT to produce a non-lethal sustainable deletion of cDCs without neutropenia and neutrophilia (20).

It is important to mention that DCs have been identified as an important osteo-immune player through their role in inflammation-induced bone loss (5). DCs have been shown to localize in inflammatory synovial and periodontal tissues, where they form aggregations with activated T cells in lymphoid foci (2, 4, 5, 8, 9). They seemed to play an indirect role in inflammation-induced bone loss through the activation of T cells (5, 9). A direct role has also been suggested in the literature, through the potential ability of some DC subsets to directly develop into osteoclasts (4). Although osteo-imunology research has focused mainly on the role of DC in inflammation-induced bone loss, little is known about their role in alveolar bone healing and repair. Our results suggested that DCs play an important role in post-extraction homeostasis in alveolar bone and that Zol treatment disrupts such role, resulting in increased bacterial load and impaired regeneration, thus rendering the alveolar bone susceptible to subsequent osteonecrosis.

Our in-vitro results demonstrated that Zol impaired the differentiation of DCs from murine bone marrow precursors as well as human peripheral blood monocytes. Bone-marrow-derived DCs (BMDCs) and monocyte-derived DCs (moDCs) phenotypically resemble the inflammatory DCs that are recruited to the site of inflammation and are crucial for wound healing after dental trauma and infection, both considered top risk factors for osteonecrosis (32). Zol also impaired the maturation of DCs when treatment was added from day 0 or day 6, suggesting that Zol could affect both the de novo synthesis of DCs from its precursors and the tissue-resident DCs.

DCs are the most efficient antigen-presenting cells (APCs) that capture, process and present antigens to T cells (33). Capturing antigens can either be through non-specific macropinocytosis, receptor-mediated endocytosis or phagocytosis of bacteria (34). Our results showed that Zol treatment impaired phagocytosis by DC, which might explain the increased bacterial burden on the alveolar bone of Zol-treated rats. Previous studies have shown that increased bacterial load could contribute to the pathogenesis of osteonecrosis, through the accumulation of bacterial toxins and secretion of mediators of osteolysis, such as acids, porins, collagenases, proteases, and lipopolysaccharides (LPS) (17, 35). The buildup of metabolites from tissue damage and bacterial toxins could lead to further impairment of local blood supply and favors the growth of more bacteria.

Osteonecrosis of the jaw has been reported with other anti-resorptive medications, such as Denosumab, a human monoclonal antibody targeting receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand (RANKL). The RANK/RANKL axis has been known for its pivotal role in bone homeostasis; however, recent evidence has shown its importance in immune homeostasis and T cell activation (36). RANKL deficiency in animal models has emphasized its important role in immune cell activation and maturation (37). Thus, immune suppression could be a common pathway for both classes of drugs in the induction of osteonecrosis.

The importance of immune modulation in MRONJ pathogenesis has been debated in the literature. Some studies suggested that BP treatment caused immune suppression, due to decreased availability and/or function of immune cells, leading to impaired wound healing and persistence of infection (38). Other studies suggested that BP treatment caused dysregulation of inflammatory cytokines, leading to hyper inflammation (39). It has been reported that Zol treatment induces the activation of gamma-delta (γδ) T cells (40, 41). However, other studies showed significant depletion of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells in patients with osteoporosis receiving BP treatment, with no underlying malignancy. (42) The results of the current study were concordant with previous findings on DCs and other immune cells of the same lineage (43–45).

We concluded that DCs play an important role in maintaining the integrity of oral mucosa and alveolar bone and that Zol treatment disrupts such role, resulting in increased bacterial load and impaired post-extraction regeneration, rendering the alveolar bone susceptible to subsequent osteonecrosis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

This project was supported by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research award number 2R15DE025134-02, National Institute of Health award number 1-S10 OD025177-01, and the National Institute of Aging award number 2P01AG036675-06A1.

ABREVIATIONS:

- Zol

Zoledronate

- DC

Dendritic Cell

- BMDCs

Bone marrow derived dendritic cells

- moDCs

Monocyte derived dendritic cells

- MRONJ

Medication related osteonecrosis of the jaw

- BP

Bisphosphonate

- IHC

Immunohistochemistry

- cDCs

Classical dendritic cell

- DT

Deptheria toxin

- CFSE

Carboxyfluoresceine succinimidyl ester

- MOI

Multiplicity of infection

- MFI

Mean fluorescent intensity

- P.gingivalis

Porphorymonas gingivalis

- FBS

Fetal Bovine serum

- PBS

Phosphate buffered saline

- HRP

Horeseradish peroxidase

- DAB

Diaminobenzidine

REFERENCES:

- 1.Drake MT, Clarke BL, and Khosla S (2008) Bisphosphonates: Mechanism of Action and Role in Clinical Practice. Mayo Clinic proceedings. Mayo Clinic 83, 1032–1045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Russell RG (2011) Bisphosphonates: the first 40 years. Bone 49, 2–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abbasi J (2018) Amid osteoporosis treatment crisis, experts suggest addressing patients’ bisphosphonate concerns. JAMA [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khosla S, and Shane E (2016) A Crisis in the Treatment of Osteoporosis. J. Bone Miner. Res 31, 1485–1487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Howie RN, Borke JL, Kurago Z, Daoudi A, Cray J, Zakhary IE, Brown TL, Raley JN, Tran LT, Messer R, Medani F, and Elsalanty ME (2015) A Model for Osteonecrosis of the Jaw with Zoledronate Treatment following Repeated Major Trauma. PLoS One 10, e0132520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kozloff KM, Volakis LI, Marini JC, and Caird MS (2010) Near-infrared fluorescent probe traces bisphosphonate delivery and retention in vivo. J. Bone Miner. Res 25, 1748–1758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Papapoulos SE, and Cremers SCLM (2007) Prolonged Bisphosphonate Release after Treatment in Children. N. Engl. J. Med 356, 1075–1076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosella D, Papi P, Giardino R, Cicalini E, Piccoli L, and Pompa G (2016) Medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: Clinical and practical guidelines. Journal of International Society of Preventive & Community Dentistry 6, 97–104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roelofs AJ, Thompson K, Ebetino FH, Rogers MJ, and Coxon FP (2010) Bisphosphonates: molecular mechanisms of action and effects on bone cells, monocytes and macrophages. Curr. Pharm. Des 16, 2950–2960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roelofs AJ, Coxon FP, Ebetino FH, Lundy MW, Henneman ZJ, Nancollas GH, Sun S, Blazewska KM, Bala JL, Kashemirov BA, Khalid AB, McKenna CE, and Rogers MJ (2010) Fluorescent risedronate analogues reveal bisphosphonate uptake by bone marrow monocytes and localization around osteocytes in vivo. J. Bone Miner. Res 25, 606–616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lombard T, Neirinckx V, Rogister B, Gilon Y, and Wislet S (2016) Medication-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw: New Insights into Molecular Mechanisms and Cellular Therapeutic Approaches. Stem Cells Int 2016, 8768162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu R-Q, Zhang D-F, Tu E, Chen Q-M, and Chen W (2014) The mucosal immune system in the oral cavity—an orchestra of T cell diversity. International Journal of Oral Science 6, 125–132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nudel I, Elnekave M, Furmanov K, Arizon M, Clausen BE, Wilensky A, and Hovav AH (2011) Dendritic cells in distinct oral mucosal tissues engage different mechanisms to prime CD8+ T cells. J. Immunol 186, 891–900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cutler CW, and Jotwani R (2006) Dendritic cells at the oral mucosal interface. J. Dent. Res 85, 678–689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Failli A, Legitimo A, Orsini G, Romanini A, and Consolini R (2014) The effects of zoledronate on monocyte-derived dendritic cells from melanoma patients differ depending on the clinical stage of the disease. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother 10, 3375–3382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kyrgidis A, Yavropoulou MP, Lagoudaki R, Andreadis C, Antoniades K, and Kouvelas D (2017) Increased CD14+ and decreased CD14- populations of monocytes 48 h after zolendronic acid infusion in breast cancer patients. Osteoporos. Int 28, 991–999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sedghizadeh PP, Kumar SK, Gorur A, Schaudinn C, Shuler CF, and Costerton JW (2008) Identification of microbial biofilms in osteonecrosis of the jaws secondary to bisphosphonate therapy. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 66, 767–775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pushalkar S, Li X, Kurago Z, Ramanathapuram LV, Matsumura S, Fleisher KE, Glickman R, Yan W, Li Y, and Saxena D (2014) Oral microbiota and host innate immune response in bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw. Int J Oral Sci 6, 219–226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Palani CD, Ramanathapuram L, Lam-Ubol A, and Kurago ZB (2018) Toll-like receptor 2 induces adenosine receptor A2a and promotes human squamous carcinoma cell growth via extracellular signal regulated kinases (1/2). Oncotarget 9, 6814–6829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Finger Stadler A, Patel M, Pacholczyk R, Cutler CW, and Arce RM (2017) Long-term sustainable dendritic cell-specific depletion murine model for periodontitis research. J. Immunol. Methods 449, 7–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muccioli M, Pate M, Omosebi O, and Benencia F (2011) Generation and labeling of murine bone marrow-derived dendritic cells with Qdot nanocrystals for tracking studies. J Vis Exp [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lam-ubol A, Hopkin D, Letuchy EM, and Kurago ZB (2010) Squamous carcinoma cells influence monocyte phenotype and suppress lipopolysaccharide-induced TNF-alpha in monocytes. Inflammation 33, 207–223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elsayed R, Abraham P, Awad ME, Kurago Z, Baladhandayutham B, Whitford GM, Pashley DH, McKenna CE, and Elsalanty ME (2018) Removal of matrix-bound zoledronate prevents post-extraction osteonecrosis of the jaw by rescuing osteoclast function. Bone 110, 141–149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Siegert I, Schatz V, Prechtel AT, Steinkasserer A, Bogdan C, and Jantsch J (2014) Electroporation of siRNA into mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages and dendritic cells. Methods Mol. Biol 1121, 111–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Unternaehrer JJ, Chow A, Pypaert M, Inaba K, and Mellman I (2007) The tetraspanin CD9 mediates lateral association of MHC class II molecules on the dendritic cell surface. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 104, 234–239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rocha-Perugini V, Martinez Del Hoyo G, Gonzalez-Granado JM, Ramirez-Huesca M, Zorita V, Rubinstein E, Boucheix C, and Sanchez-Madrid F (2017) CD9 Regulates Major Histocompatibility Complex Class II Trafficking in Monocyte-Derived Dendritic Cells. Mol. Cell. Biol 37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Svejda B, Muschitz C, Gruber R, Brandtner C, Svejda C, Gasser RW, Santler G, and Dimai HP (2016) [Position paper on medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (MRONJ)]. Wien. Med. Wochenschr 166, 68–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Caetano-Lopes J, Canhao H, and Fonseca JE (2009) Osteoimmunology--the hidden immune regulation of bone. Autoimmun Rev 8, 250–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hardy R, and Cooper MS (2009) Bone loss in inflammatory disorders. J. Endocrinol 201, 309–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arizon M, Nudel I, Segev H, Mizraji G, Elnekave M, Furmanov K, Eli-Berchoer L, Clausen BE, Shapira L, Wilensky A, and Hovav AH (2012) Langerhans cells down-regulate inflammation-driven alveolar bone loss. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 109, 7043–7048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Blijswijk J, Schraml BU, and Reis e Sousa C (2013) Advantages and limitations of mouse models to deplete dendritic cells. Eur. J. Immunol 43, 22–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ruggiero SL, Dodson TB, Fantasia J, Goodday R, Aghaloo T, Mehrotra B, and O’Ryan F American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons Position Paper on Medication-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw—2014 Update. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg 72, 1938–1956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Banchereau J, and Steinman RM (1998) Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature 392, 245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu Z, and Roche PA (2015) Macropinocytosis in phagocytes: regulation of MHC class-II-restricted antigen presentation in dendritic cells. Front. Physiol 6, 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reid IR (2009) Osteonecrosis of the jaw: who gets it, and why? Bone 44, 4–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cheng ML, and Fong L (2014) Effects of RANKL-Targeted Therapy in Immunity and Cancer. Front. Oncol 3, 329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ferrari-Lacraz S, and Ferrari S (2011) Do RANKL inhibitors (denosumab) affect inflammation and immunity? Osteoporos. Int 22, 435–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bringmann A, Schmidt SM, Weck MM, Brauer KM, von Schwarzenberg K, Werth D, Grunebach F, and Brossart P (2007) Zoledronic acid inhibits the function of Toll-like receptor 4 ligand activated monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Leukemia 21, 732–738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Muratsu D, Yoshiga D, Taketomi T, Onimura T, Seki Y, Matsumoto A, and Nakamura S (2013) Zoledronic acid enhances lipopolysaccharide-stimulated proinflammatory reactions through controlled expression of SOCS1 in macrophages. PLoS One 8, e67906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Santini D, Martini F, Fratto ME, Galluzzo S, Vincenzi B, Agrati C, Turchi F, Piacentini P, Rocci L, Manavalan JS, Tonini G, and Poccia F (2009) In vivo effects of zoledronic acid on peripheral gammadelta T lymphocytes in early breast cancer patients. Cancer Immunol. Immunother 58, 31–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roelofs AJ, Thompson K, Gordon S, and Rogers MJ (2006) Molecular mechanisms of action of bisphosphonates: current status. Clin. Cancer Res 12, 6222s–6230s [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kalyan S, Wang J, Quabius ES, Huck J, Wiltfang J, Baines JF, and Kabelitz D (2015) Systemic immunity shapes the oral microbiome and susceptibility to bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaw. J. Transl. Med 13, 212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wolf AM, Rumpold H, Tilg H, Gastl G, Gunsilius E, and Wolf D (2006) The effect of zoledronic acid on the function and differentiation of myeloid cells. Haematologica 91, 1165–1171 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pazianas M (2011) Osteonecrosis of the jaw and the role of macrophages. J. Natl. Cancer Inst 103, 232–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Orsini G, Failli A, Legitimo A, Adinolfi B, Romanini A, and Consolini R (2011) Zoledronic acid modulates maturation of human monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood) 236, 1420–1426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fujii S. i., Liu K, Smith C, Bonito AJ, and Steinman RM (2004) The Linkage of Innate to Adaptive Immunity via Maturing Dendritic Cells In Vivo Requires CD40 Ligation in Addition to Antigen Presentation and CD80/86 Costimulation. The Journal of Experimental Medicine 199, 1607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wilensky A, Segev H, Mizraji G, Shaul Y, Capucha T, Shacham M, and Hovav AH (2014) Dendritic cells and their role in periodontal disease. Oral Dis. 20, 119–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cutler CW, and Teng YT (2007) Oral mucosal dendritic cells and periodontitis: many sides of the same coin with new twists. Periodontol. 2000 45, 35–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Howie RN, Bhattacharyya M, Salama M, El Refaey M, Isales C, Borke J, Daoudi A, Medani F, and Elsalanty M (2015) Removal of pamidronate from bone in rats using systemic and local chelation. Arch. Oral Biol 60, 1699–1707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.