Abstract

Background

Burnout has adverse implications in healthcare settings, compromising patient care. Allied health professionals (AHPs) are defined as individuals who work collaboratively to deliver routine and essential healthcare services, excluding physicians and nurses. There is a lack of studies on burnout among AHPs in Singapore. This study explored factors associated with a self-reported burnout level and barriers to seeking psychological help among AHPs in Singapore.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional study in a sample of AHPs in a tertiary hospital from October to December 2019. We emailed a four-component survey to 1127 eligible participants. The survey comprised four components: (1) sociodemographic characteristics, (2) Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI-HSS), (3) Areas of Worklife Survey, and (4) Perceived Barriers to Psychological Treatment (PBPT). We performed a multiple logistic regression analysis to identify factors associated with burnout. Adjusted odds ratios (AORs) and associated 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were computed.

Results

In total, 328 participants completed the questionnaire. The self-reported burnout level (emotional exhaustion>27 and/or depersonalization>10) was 67.4%. The majority of the respondents were female (83.9%), Singaporean (73.5%), aged 40 years and below (84.2%), and Chinese ethnicity (79.9%). In the multiple logistic regression model, high burnout level was negatively associated with being in the age groups of 31 to 40 (AOR 0.39, 95% CI 0.16–0.93) and 40 years and older (AOR 0.30, 95% CI 0.10–0.87) and a low self-reported workload (AOR 0.35, 95% CI 0.23–0.52). High burnout level was positively associated with a work experience of three to five years (AOR 5.27, 95% CI 1.44–20.93) and more than five years (AOR 4.24; 95% CI 1.16–16.79. One hundred and ninety participants completed the PBPT component. The most frequently cited barriers to seeking psychological help by participants with burnout (n = 130) were ‘negative evaluation of therapy’ and ‘time constraints.’

Conclusions

This study shows a high self-reported burnout level and identifies its associated factors among AHPs in a tertiary hospital. The findings revealed the urgency of addressing burnout in AHPs and the need for effective interventions to reduce burnout. Concurrently, proper consideration of the barriers to seeking help is warranted to improve AHPs' mental well-being.

Introduction

Burnout is a prolonged response to chronic emotional and interpersonal stressors on the job, comprising three dimensions: exhaustion, cynicism, and inefficiency [1]. These dimensions are further defined as follows: exhaustion of emotional or physical capacity due to stress, a degree of indifference or detachment from various aspects of work, and a sense of inadequacy or reduced personal accomplishment, respectively [1].

In healthcare settings, burnout negatively impacts outcomes at the individual, interpersonal, and institutional levels. At the individual level, burnout is associated with reduced job satisfaction, increased absenteeism, medical errors, sickness, injury, and accidents among healthcare providers [2, 3]. These individual-level impacts may lead to reduced care quality and higher mortality among patients [4, 5]. From an interpersonal perspective, burnout is associated with emotional dissonance due to chronic exhaustion and cynicism [6]. Emotional dissonance is described as a conflict between personal emotions and organizational demands. On an institutional level, burnout is linked to a higher turnover of healthcare workers [7, 8] and decreased workforce efficiency [9], posing a substantial economic burden on the healthcare system [10].

The pernicious nature of burnout in healthcare settings has prompted numerous studies on its prevalence in physicians and nurses in Singapore and internationally. For example, high burnout levels and their associated factors among physicians and nurses have been reported in Singapore [11, 12]. Extensive research involves the barriers to seeking help for doctors, such as fear of stigma, lack of available time, and lack of convenient access [13, 14].

Allied health professionals (AHPs) are defined as individuals who work collaboratively to deliver routine and essential healthcare services, excluding physicians and nurses [15, 16]. AHPs include, but are not limited to, occupational therapists, physiotherapists, pharmacists, medical social workers, and radiographers [17]. This system is similarly adopted in the United Kingdom [18] and the United States [19] and plays an essential role in improving hospital efficiencies and access to care [19]. In Singapore, the Allied Health Professions Council (AHPC) defines and classifies allied health occupations similar to other countries [20].

Studies in other countries have reported a high prevalence of burnout in AHPs. In the United States, physiotherapists and occupational therapists reported high rates of emotional exhaustion (58%), negative feelings about their work and their clients (94%), and an almost non-existent sense of personal accomplishment (1%) [21]. However, there are currently no studies examining burnout levels and their associated risk factors among AHPs in Singapore.

This study aims to identify the self-reported burnout levels and explore their associations with sociodemographic factors and the work environment among AHPs in Singapore. Based on the evidence from studies on doctors and nurses [11, 12, 22], we hypothesized that burnout levels among AHPs in Singapore would be similarly high, and age and work experience would be significantly associated with burnout levels. Our secondary objective is to identify significant barriers in seeking psychological help among AHPs with a high burnout level.

Materials and methods

Study design and sampling

We conducted a cross-sectional study among AHPs working in a tertiary acute care hospital between October 2019 to December 2019. Based on previous studies looking at the prevalence of burnout in AHPs and the total number of AHPs in Singapore [23, 24], we determined the sample size through the application of a single proportion formula with the assumption of 60% prevalence, 5% marginal error, and 95% confidence level (CI). The minimum required sample size for the study was 348.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We defined AHPs according to the definition recommended by Singapore’s AHPC–all healthcare professionals who work collaboratively to deliver routine and essential healthcare services, excluding physicians and nurses [15, 16]. AHPs in a tertiary hospital of all seniority levels were included in this study [16].

Questionnaire design and measurement

We developed an electronic survey and emailed all AHP staff working for the tertiary hospital to request their participation. The survey comprised four components: (1) sociodemographic characteristics, (2) Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI-HSS), (3) Areas of Worklife Survey (AWS), and (4) Perceived Barriers to Psychological Treatment (PBPT).

Sociodemographic questions were adapted from the Singapore National Health Survey 2010 [25], covering residency status, age, gender, ethnicity, income levels, caregiver status, occupation, employment history, physical activity levels, and mental health.

We assessed burnout by using the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI), in particular, the MBI-Human Services Survey for Medical Personnel MBI-HSS(MP) [26]. MBI has been widely used in different settings [27] and is the best-known questionnaire used in most clinical studies assessing burnout [28]. The questionnaire consisted of nine questions under emotional exhaustion (EE), five questions under depersonalization (DP), and eight questions under personal accomplishment (PA). Participants were asked to rate on a Likert scale of 0 (never) to 6 (every day) on how often they experienced the symptoms, and the total scores for each subsection were tallied. Higher EE and DP scores correspond to a higher burnout level, while, conversely, lower PA scores signify a higher burnout level. The scale’s validity has previously been demonstrated in similar studies in Japan and China, countries with strong Asian cultural influence [29–31]. It has also been used to evaluate burnout levels in studies in Singapore [11, 32].

The maximum score was 54 points for EE, 30 points for DP, and 48 points for PA. No universal cut-off score has been recommended to define burnout. In a systematic review of burnout among healthcare professionals, burnout was defined using the cut-offs of EE>27 or DP>10, with PA excluded in the majority of the included studies [27]. PA was also excluded from previous studies because its association with burnout has been more variable and complex [1]. It has been postulated that PA may be a function of EE and DP because a work situation with overwhelming demands may also erode one’s PA [1]. Hence, we defined a high burnout level as experiences of a high level of EE (EE>27), DP (DP>10), or both [33]. We also included an analysis of a high burnout level defined according to EE>27, DP>10, or PA<33 (Appendix 1).

The AWS is a 28-item scale that is part of the MBI toolkit [34]. The scale examines the dimensions of an individual’s work life and predicts their relationship with burnout [35]. The six dimensions assessed in the survey were: workload, control, reward, community, fairness, and values. “Workload” (five items) refers to the employee’s ability to cope with work demands. “Control” (four items) refers to the level of active involvement of an employee in work decisions. “Reward” (four items) refers to rewards that place higher value and recognition on an employee’s work. “Community” (five items) refers to the overall quality of social interaction at work. “Fairness” (six items) refers to the general equity of decisions made at the workplace. Furthermore, “Values” (four items) refers to the dissonance between personal and organizational values [36]. Respondents were asked to rate on a Likert scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) on their perceptions of work setting qualities that play a role in burnout. The item scores in each domain are then averaged. A higher AWS score indicates a more balanced relationship, rather than a conflicted one [35], between the respondent and their work [37].

The last component of the survey comprised the 27-item PBPT questionnaire [38]. Items are classified into nine domains: stigma, lack of motivation, emotional concerns, negative evaluations of therapy, misfit of therapy to needs, time constraints, participation restriction, availability of services, and cost [38]. We asked participants to rate on a 5-point Likert scale the degree to which each item hindered them from seeing a counselor or a therapist. A score of four to five was deemed as “substantial barriers.” A domain is deemed to represent a “substantial barrier” if at least one item within that domain was reflected as a “substantial barrier.” Given the lengthy questionnaire and to improve the overall response rate [39], we made the PBPT questionnaire component optional for participants in this study.

Data analyses

We used R Commander version 2.7.11 to perform all statistical analyses. We computed Cronbach’s alpha for each MBI subscale and AWS domain to assess reliability. We performed bivariate analyses of the demographic factors and the AWS dimensions to examine their association with burnout level using Pearson’s Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact tests (when a cell count was smaller than five). We identified factors associated with burnout levels by using multiple logistic regression analysis. We entered variables with statistical significance (p<0.05) in bivariate analyses simultaneously in the multiple logistic regression model. For respondents who completed the optional component on PBPT, we recorded the incidence of expressing a variable as a “substantial barrier” among participants who experienced a high burnout level.

Ethical considerations

The National Healthcare Group Domain Specific Review Board approved this study (2019/00477). No identifiable information of participants was collected. We stored all data on REDCap, a secure, Health Insurance Portability, and Accountability Act compliant, web-based server. We included a participant information sheet in the email, providing all relevant information on participant anonymity and consent for voluntary participation.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics

Among the 1127 eligible AHPs invited, 345 participated in the survey. However, we excluded 17 questionnaires due to incomplete entries. We included a total of 328 respondents in the analyses, providing a response rate of 29.1%. Compared to those who did not participate, our participants were more likely to be female, non-Singaporeans/non-SPR, 21 to 30 years old, and had more than three years of working experience.

Table 1 shows the sociodemographic characteristics of the respondents. The majority of the respondents were Singaporean (73.5%), aged 40 years and below (84.2%), female (83.9%), and Chinese ethnicity (79.9%). Almost all respondents were working full time (94.2%). More than half of the respondents had worked for more than five years in the same organization. Approximately half of the respondents worked as frontline staff and reported low levels of physical activity. Only a small proportion of the respondents reported a history of mental illness or had sought help from a professional within the past year for mental illness. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for EE, DP, and PA in MBI-HSS in this study were 0.93, 0.81, and 0.85, respectively, suggesting that the overall measurement was reliable.

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of allied health professionals in a tertiary hospital in Singapore.

| Variables | Number (n = 328) | |

|---|---|---|

| n (%) | ||

| Residency status | ||

| Singaporean | 241 (73.5) | |

| Permanent resident | 59 (18.0) | |

| Foreigner | 28 (8.5) | |

| Age group | ||

| 21 to 30 | 137 (41.8) | |

| 31 to 40 | 139 (42.4) | |

| 41 years and above | 52 (15.9) | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 53 (16.1) | |

| Female | 275 (83.9) | |

| Ethnic group | ||

| Chinese | 262 (79.9) | |

| Non-Chinese | 66 (20.1) | |

| Average monthly household income | ||

| Less than S$5000 | 25 (7.6) | |

| S$5000 to S$9000 | 118 (36.0) | |

| S$9000 and above | 109 (33.2) | |

| Not disclosed | 76 (23.2) | |

| Caregiver status | ||

| Yes | 72 (22.0) | |

| No | 229 (69.8) | |

| Do not wish to disclose | 27 (8.2) | |

| Occupation | ||

| Clinical psychologist | 5 (1.5) | |

| Radiographer | 32 (9.8) | |

| Dietician | 19 (5.8) | |

| Medical technologist | 96 (29.3) | |

| Medical social worker | 19 (5.8) | |

| Occupational therapist | 33 (10.0) | |

| Pharmacist | 40 (12.2) | |

| Physiotherapist | 28 (8.5) | |

| Podiatrist | 5 (1.5) | |

| Respiratory therapist | 5 (1.5) | |

| Speech therapist | 17 (5.2) | |

| Others | 29 (8.8) | |

| Duration working at the current organization | ||

| <1 year | 24 (7.3) | |

| 1–2 years | 47 (14.3) | |

| 3–5 years | 64 (19.5) | |

| >5 years | 193 (58.8) | |

| Nature of work | ||

| Front line staff | 175 (53.4) | |

| Administrator | 11 (3.3) | |

| Junior management | 55 (16.8) | |

| Senior management | 20 (6.1) | |

| Others | 67 (20.4) | |

| Employment status | ||

| Full time | 309 (94.2) | |

| Part-time | 19 (5.8) | |

| Average number of night shifts per month | ||

| 1–3 times | 33 (10.0) | |

| 4–6 times | 18 (5.5) | |

| 7 or more times | 4 (1.2) | |

| Not applicable | 273 (83.2) | |

| Level of physical activity† | ||

| Low | 185 (56.6) | |

| Moderate | 74 (22.6) | |

| High | 68 (20.8) | |

| Previous history of mental illness* | ||

| Yes | 7 (2.2) | |

| No | 311 (97.8) | |

| Sough medical help in the past year | ||

| Yes | 15 (4.7) | |

| No | 305 (95.3) | |

*Mental illness refers to a behavioral or psychological syndrome or pattern in an individual that causes clinically significant distress. It warrants diagnosis and management by a medical professional [40, 41].

† Low physical activity refers to sedentary, little, or no exercise. Moderate physical activity refers to a low level of exertion or aerobic exercises for 20–60 min per week. High physical activity refers to aerobic exercises for > 1 h per week.

Burnout level and associated sociodemographic factors

The self-reported burnout level among AHPs in this study was 67.4%. A majority of the respondents reported a high burnout level on EE (n = 203, 61.9%), less than half reported a high level on DP (n = 139, 42.4%), and more than one-third had both high EE and DP (n = 122, 37.1%). Among the occupational groups, dieticians (94.7%) and pharmacists (82.5%) had the highest burnout levels.

Table 2 shows the sociodemographic characteristics of AHPs stratified by burnout levels. Full-time workers were significantly more likely to experience a high burnout level than part-time workers. Respondents with more than one year of work experience were significantly more likely to experience a high burnout level than those with less than one year of work experience. Respondents who had sought professional mental help in the past year were significantly more likely to have a high burnout level than those who did not.

Table 2. Sociodemographic characteristics of allied health professionals stratified by burnout levels.

| Variables | Low burnout (n = 221) | High burnout (n = 107) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | p-value | ||

| Residency status | 0.10 | |||

| Singaporean | 164 (68.0) | 77 (32.0) | ||

| Permanent Resident | 43 (72.9) | 16 (27.1) | ||

| Foreigner | 14 (50.0) | 14 (50.0) | ||

| Age group | <0.01 | |||

| 21 to 30 | 101 (73.7) | 36 (26.3) | ||

| 31 to 40 | 94 (67.6) | 45 (32.4) | ||

| 41 years and above | 26 (50.0) | 26 (50.0) | ||

| Gender | 1.00 | |||

| Male | 36 (67.9) | 17 (32.1) | ||

| Female | 185 (67.3) | 90 (32.7) | ||

| Ethnic group | 0.14 | |||

| Chinese | 182 (69.5) | 80 (30.5) | ||

| Non-Chinese | 39 (59.1) | 27 (40.9) | ||

| Average monthly household income | 0.14 | |||

| Less than S$5000 | 18 (72.0) | 7 (28.0) | ||

| S$5000 to S$9000 | 85 (72.0) | 33 (28.0) | ||

| S$9000 and above | 64 (58.7) | 45 (41.3) | ||

| Not disclosed | 54 (71.1) | 22 (28.9) | ||

| Caregiver status | 0.96 | |||

| Yes | 48 (66.7) | 24 (33.3) | ||

| No | 154 (67.2) | 75 (32.8) | ||

| Do not wish to disclose | 19 (70.4) | 8 (29.6) | ||

| Occupation | 0.07 | |||

| Clinical psychologist | 2 (40.0) | 3 (60.0) | ||

| Radiographer | 19 (59.4) | 13 (40.6) | ||

| Dietician | 18 (94.7) | 1 (5.3) | ||

| Medical technologist | 64 (66.7) | 32 (33.3) | ||

| Medical social worker | 15 (78.9) | 4 (21.1) | ||

| Occupational therapist | 21 (63.6) | 12 (36.4) | ||

| Pharmacist | 33 (82.5) | 7 (17.5) | ||

| Physiotherapist | 17 (60.7) | 11 (39.3) | ||

| Podiatrist | 3 (60.0) | 2 (40.0) | ||

| Respiratory therapist | 2 (40.0) | 3 (60.0) | ||

| Speech therapist | 10 (58.8) | 7 (41.2) | ||

| Others | 17 (58.6) | 12 (41.4) | ||

| Duration working at the current organization | <0.01 | |||

| <1 year | 9 (37.5) | 15 (62.5) | ||

| 1–2 years | 31 (66.0) | 16 (34.0) | ||

| 3–5 years | 53 (82.8) | 11 (17.2) | ||

| >5 years | 128 (66.3) | 65 (33.7) | ||

| Nature of work | 0.98 | |||

| Front line staff | 116 (66.3) | 59 (33.7) | ||

| Administrator | 7 (63.6) | 4 (36.4) | ||

| Junior management | 38 (69.1) | 17 (30.9) | ||

| Senior management | 14 (70.0) | 6 (30.0) | ||

| Others | 46 (68.7) | 21 (31.3) | ||

| Employment status | <0.01 | |||

| Full time | 214 (69.3) | 95 (30.7) | ||

| Part time | 7 (36.8) | 12 (63.2) | ||

| Average number of night shifts per month | 0.24 | |||

| 1–3 times | 25 (75.8) | 8 (24.2) | ||

| 4–6 times | 12 (66.7) | 6 (33.3) | ||

| 7 or more times | 1 (25.0) | 3 (75.0) | ||

| Not applicable | 183 (67.0) | 90 (33.0) | ||

| Level of physical activity† | 0.58 | |||

| Low | 129 (69.7) | 56 (30.3) | ||

| Moderate | 49 (66.2) | 25 (33.8) | ||

| High | 43 (63.2) | 25 (36.8) | ||

| Previous history of mental illness* | 0.43 | |||

| Yes | 6 (85.7) | 1 (14.3) | ||

| No | 206 (66.2) | 105 (33.8) | ||

| Sough medical help in the past year | <0.01 | |||

| Yes | 15 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| No | 198 (64.9) | 107 (35.1) | ||

*Mental illness refers to a behavioral or psychological syndrome or pattern in an individual that causes clinically significant distress. It warrants diagnosis and management by a medical professional [40, 41].

† Low physical activity refers to sedentary, little, or no exercise. Moderate physical activity refers to a low level of exertion or aerobic exercises for 20–60 min per week. High physical activity refers to aerobic exercises for >1 h per week.

AWS domains and association with burnout levels

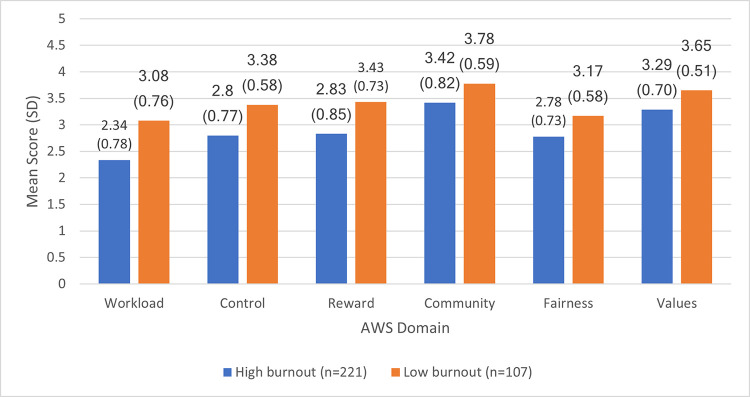

The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for workload, control, reward, community, fairness, and values were 0.78, 0.77, 0.89, 0.86, 0.82, and 0.78, respectively. As shown in Fig 1, all AWS domains were significantly associated with a higher burnout level (p≤0.01), with workload, control, and reward showing the most significant differences in the mean scores between participants with a low and high burnout level.

Fig 1. Comparisons of the mean scores of the Areas of Worklife Survey domains stratified by burnout levels (n = 328).

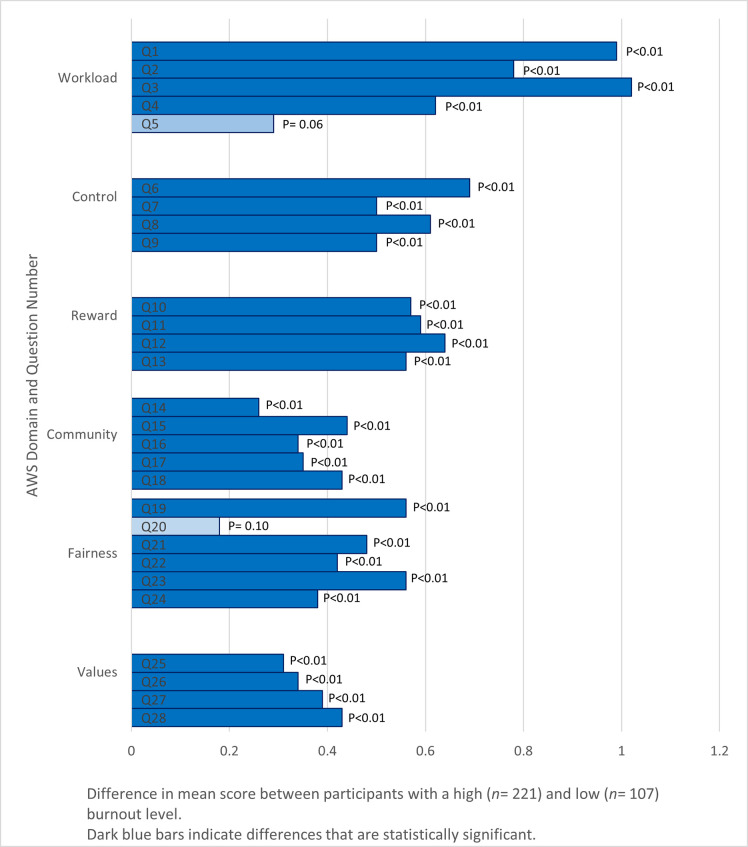

AWS individual statements and association with burnout levels

Fig 2 presents the absolute mean score differences of responses to individual AWS statements between participants with a high and low burnout level. The majority of the mean score differences in all domains were significant. The workload domain had the highest absolute difference compared to the other domains. In particular, the statements “I have so much work to do on the job that it takes me away from my personal interests” (question 3) and “I do not have time to do the work that must be done” (question 1) in the workload domain scored the highest absolute difference in mean scores among all questions.

Fig 2. Comparisons of difference in mean scores of Areas of Worklife Survey statements in all domains between participants with a high (n = 221) and low (n = 107) burnout level.

Factors associated with burnout levels

In the multiple logistic regression model (Table 3), AHPs who had lower mean scores in the workload subdomain of the AWS, indicative of a high workload burden, were almost three times more likely to have a high burnout level than those who had higher mean scores. Compared to respondents aged 30 years and below, older AHPs aged 31 and above were significantly less likely to have a high burnout level. Moreover, respondents who had worked in the current organization for more than three years were approximately five times more likely to experience a higher burnout level than respondents who had worked in the current organization for less than one year.

Table 3. Factors associated with burnout levels in a multiple logistic regression analysis.

| Coefficient (SE) | AOR (95% CI) | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AWS domain | ||||

| Workload | -1.05 (0.21) | 0.35 (0.23, 0.52) | <0.01 | |

| Control | -0.46 (0.29) | 0.63 (0.35, 1.10) | 0.11 | |

| Reward | -0.34 (0.25) | 0.71 (0.43, 1.17) | 0.18 | |

| Community | -0.39 (0.26) | 0.68 (0.40, 1.12) | 0.13 | |

| Fairness | -0.18 (0.32) | 0.83 (0.45, 1.54) | 0.56 | |

| Values | -0.10 (0.30) | 0.90 (0.50, 1.63) | 0.74 | |

| Age group | ||||

| 21 to 30 | Reference | 1.00 | - | |

| 31 to 40 | -0.93 (0.45) | 0.39 (0.16, 0.94) | 0.04 | |

| 41 years and above | -1.20 (0.55) | 0.30 (0.10, 0.87 | 0.03 | |

| Duration working at the current organization | ||||

| <1 year | Reference | 1.00 | - | |

| 1–2 years | 0.61 (0.68) | 1.84 (0.50, 7.23) | 0.37 | |

| 3–5 years | 1.66 (0.68) | 5.27 (1.44, 20.91) | 0.01 | |

| >5 years | 1.44 (0.68) | 4.23 (1.16, 16.76) | 0.03 | |

| Employment status | ||||

| Part-time | Reference | 1.00 | - | |

| Full-time | 0.62 (0.60) | 1.86 (0.58–6.42) | 0.30 | |

| Sought medical help in the past year | ||||

| No | Reference | 1.00 | - | |

| Yes | 17.13 (854.15) | 27398446.44 (NA) | 0.98 | |

Abbreviations: AWS, Areas of Worklife Survey; SE, standard error; CI, confidence interval; AOR, adjusted odds ratio.

Perceived barriers to seeking psychological help

Of the total, 57.9% (n = 190) of participants completed the optional component on PBPT, of which 130 had a high burnout level. Table 4 shows that, among the participants with a high burnout level, the most frequently cited barriers to seeking psychological help were ‘negative evaluation of therapy’ (60%) and ‘time constraints’ (50%).

Table 4. Perceived barriers to seeking psychological help among participants with a high burnout level (n = 130).

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Stigma | 29 (48.3) |

| Lack of motivation | 16 (26.7) |

| Emotional concerns | 16 (26.7) |

| Negative evaluation of therapy | 36 (60.0) |

| Misfit of therapy to needs | 27 (45.0) |

| Time constraints | 30 (50.0) |

| Participation restriction | 27 (45.0) |

| Availability of services | 25 (41.7) |

| Cost | 21 (35.0) |

Discussion

This study is the first to investigate the self-reported burnout level and its related factors among AHPs in Singapore. We found a high burnout level at 67.4% among AHPs in a tertiary hospital. Based on the job demands-resources model of burnout, high EE and DP scores in our study demonstrates a high probability of resource conservation by AHPs. AHPs may spend less time with patients, resulting in increased clinical errors [42] and negatively impacting patient care. However, compared to a study conducted among physical and occupational therapists in the United States, while the EE scores were similar (58% vs. 62% in our study), the DP scores in our study were significantly lower (94% vs. 42% in our study) [21]. The relatively lower depersonalization scores may be attributed to the participants’ organizational factors, such as different healthcare systems and attitudes towards work between AHPs in Asian and Western societies [43]. The lower level could be culturally equivalent to the United State’s higher levels due to differences in the participants’ attitudes towards surveys and response patterns [44–46].

Of note, the high self-reported burnout level in pharmacists (82.5%) and dieticians (94.7%) is concerning. We postulate that pharmacists may be prone to experiencing burnout and lower job satisfaction than other occupations, with more job variety reported in previous studies [47]. However, similar studies have shown that dieticians score lower EE than comparison groups of doctors, nurses, and social workers [23], indicating lower burnout. Hence, the high burnout level among dieticians may be due to other organizational or demographic factors. As the sample size of pharmacists and dieticians in this study was small, these associations were not statistically significant. Further studies will be warranted to identify the associated factors of burnout.

In the multiple regression analysis, we found a higher burnout level in the younger group of 21 to 30 than in AHPs aged 31 years and above. Previous studies have supported this trend of burnout affecting younger employees [2, 3]. The lower burnout level in older participants may be explained by their better coping or occupational handling stress [48, 49]. Work experience may play an essential role in burnout. Employees who have worked for a longer duration (three years and above) in the same organization were more likely to have a high burnout level than those working for less than a year. We postulate that this could be due to long-term exposure to the patient suffering at the workplace, resulting in emotional exhaustion [50, 51].

We found that heavier self-reported workloads are associated with a higher burnout level among the AHPs. It was the only subdomain of the AWS significantly associated with burnout after adjusting for covariates. Previous studies have shown the adverse effects of increased workloads among healthcare workers, manifesting burnout [52, 53]. In our study, we demonstrated that this association holds for AHPs in Singapore. In particular, the association of heavier workload among AHPs with a high burnout level is most apparent when the workload interferes with their “personal interests” and “work that must be done.”

Hence, the identified associated factors of burnout levels highlight the need to address potential stressors at work. Concurrently, given that heavy self-reported workload and more extended work experience is associated with a high burnout level, workplace interventions are crucial. Based on this study, the association of heavier self-reported workload among AHPs with a high burnout level is most apparent when the workload becomes excessive or interferes with their interests. We propose that future studies look at interventions conducted at both personal and workplace levels [54].

Evidence-based strategies have shown the effectiveness of interventions that target personal coping skills such as mindfulness and stress management training [55, 56], and cognitive-behavioral interventions in reducing occupational stress levels [57].

Workplace strategies could be explored in future studies. Protected time, proper shift allocations, flexibility in working structure, and adequate workforce distribution could be highly beneficial [58, 59]. A case example will be the United Kingdom-commissioned review [60]. The review proposes a whole-system workplace intervention, from understanding local staff requirements, multi-level staff engagement, strong visible leadership, support for well-being at board level, and a focus on management capability to improve mental well-being and lower burnout.

Lastly, among participants who completed the PBPT questionnaire and experienced a high burnout level, ‘negative evaluation of therapy’ and ‘time constraints’ were identified as the most frequently cited barriers to seeking psychological help. Firstly, negative evaluation of therapy may be attributed to the high prevalence of negative attitudes towards mental illnesses in Asian societies such as Singapore [61, 62]. Participants may experience similar negative perceptions of therapy for mental health. Hence, interventions in improving the public perception towards mental health and therapy may reduce barriers to seeking help. Secondly, time constraints highlight that the daily responsibilities of AHPs may contribute to burnout and compete for time, hence a barrier in undergoing therapy. Daily responsibilities include formal duties to their patients and adjunct activities such as documentation, communication, following up on treatment, performing roll calls, or handing over. These auxiliary activities underestimate the time spent on the job [63]. Accounting for the adjunct activities and enforcing stricter regulations in total work hours may be essential to improve uptake of AHPs in seeking help for their burnout.

Study limitations

There are a few limitations to this study. First, the response rate to the survey was only 29.1%. The low response rate may translate to a significant non-response bias for the study. Despite utilizing approaches to increase the response rate, such as through the engagement of respective departmental heads and email reminders, the survey response remained low. The low response rate may be due to hospital privacy protocols that limited the survey administration to emails and prevented physical surveys. Second, burnout is multi-factorial, and this study may not capture the full spectrum of variables. Factors that were not covered in this study include the increasing computerization of practice [64] and the participants’ personality traits [65]. Third, this study's cross-sectional nature does not allow the authors to determine causal relationships between the risk factors and burnout. Further longitudinal studies will be needed. Fourth, other inventories such as the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory can be explored in future studies to offer new insights into burnout [66]. Fifth, as there are limited validation studies of MBI in Asian countries, MBI may have limited validity in characterizing burnout as a self-reported tool. Lastly, participant response could have been influenced by social desirability bias due to the highly stigmatized perception of burnout in the workplace.

Conclusions

This study is the first to show a high burnout level and identify its associated factors among AHPs in Singapore. The self-reported burnout level among AHPs in this study was 67.4%. The identified risk factors included increased self-reported workload, lesser work experience, and younger age. Besides, respondents with a high burnout level reported the lack of motivation and time constraints as significant barriers to seeking psychological help for burnout. The findings revealed the significance and urgency of addressing burnout in these vulnerable target groups. There is also a potential need to implement individual and organizational interventions such as mindfulness and stress management training, cognitive-behavioral interventions, or workplace interventions that target organizational, cultural, social, and physical aspects of staff health. These interventions should be implemented with proper consideration of the barriers to reduce burnout risk effectively. Further longitudinal studies will help explore the causal relationship between the risk factors and burnout to characterize burnout's nature better.

Supporting information

(XLSX)

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the faculty members of Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health and the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, whose advice and ideas were integral to this study's success. The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers whose input and feedback significantly improved this manuscript. Lastly, the authors would like to thank the Community Health Project team members for their contributions to the study's conceptualization.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

References

- 1.Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP. Job burnout. Annual review of psychology. 2001;52:397–422. 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Silva SC, Nunes MA, Santana VR, Reis FP, Machado Neto J, Lima SO. Burnout syndrome in professionals of the primary healthcare network in Aracaju, Brazil. Cien Saude Colet. 2015;20(10):3011–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartosiewicz A, Januszewicz P. Readiness of Polish Nurses for Prescribing and the Level of Professional Burnout. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;16(1):35 10.3390/ijerph16010035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Welp A, Meier LL, Manser T. Emotional exhaustion and workload predict clinician-rated and objective patient safety. Frontiers in psychology. 2014;5:1573 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cimiotti JP, Aiken LH, Sloane DM, Wu ES. Nurse staffing, burnout, and health care-associated infection. American journal of infection control. 2012;40(6):486–90. 10.1016/j.ajic.2012.02.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Consiglio C. Interpersonal strain at work: A new burnout facet relevant for the health of hospital staff. Burnout Research. 2014;1(2):69–75. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leiter MP, Maslach C. Nurse turnover: the mediating role of burnout. Journal of nursing management. 2009;17(3):331–9. 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2009.01004.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shanafelt T, Sloan J, Satele D, Balch C. Why do surgeons consider leaving practice? Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2011;212(3):421–2. 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye LN, West CP, Sinsky CA. Potential Impact of Burnout on the US Physician Workforce. Mayo Clinic proceedings. 2016;91(11):1667–8. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Han S, Shanafelt TD, Sinsky CA, Awad KM, Dyrbye LN, Fiscus LC, et al. Estimating the Attributable Cost of Physician Burnout in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170(11):784–90. 10.7326/M18-1422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee PT, Loh J, Sng G, Tung J, Yeo KK. Empathy and burnout: a study on residents from a Singapore institution. Singapore Med J. 2018;59(1):50–4. 10.11622/smedj.2017096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tay WY, Earnest A, Tan SY, Ng MJM. Prevalence of Burnout among Nurses in a Community Hospital in Singapore: A Cross-Sectional Study. 2014;23(2):93–9. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clough BA, March S, Leane S, Ireland MJ. What prevents doctors from seeking help for stress and burnout? A mixed-methods investigation among metropolitan and regional-based australian doctors. Journal of clinical psychology. 2019;75(3):418–32. 10.1002/jclp.22707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guille C, Speller H, Laff R, Epperson CN, Sen S. Utilization and barriers to mental health services among depressed medical interns: a prospective multisite study. Journal of graduate medical education. 2010;2(2):210–4. 10.4300/JGME-D-09-00086.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.(ASAHP) AoSoAHP. What is Allied Health? 2015 [Available from: http://www.asahp.org/what-is.

- 16.K M. Jobs to Careers: Transforming the Front Lines of Health Care: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; December 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 17.SingHealth. The Heartbeat of Healthcare: Allied Health Professionals; Many Talents, One Passion. 2019.

- 18.Davis SF, Enderby P, Harrop D, Hindle L. Mapping the contribution of Allied Health Professions to the wider public health workforce: a rapid review of evidence-based interventions. J Public Health (Oxf). 2017;39(1):177–83. 10.1093/pubmed/fdw023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Committee CW. Allied Health: The Hidden Health Care Workforce: California Hospital Association Leadership in Health Policy and Advocacy; 2009 [Available from: https://www.calhospital.org/general-information/allied-health-hidden-health-care-workforce.

- 20.Welcome to the AHPC Singapore government agency website 2020 [Available from: https://www.healthprofessionals.gov.sg/ahpc.

- 21.Balogun JA, Titiloye V, Balogun A, Oyeyemi A, Katz J. Prevalence and determinants of burnout among physical and occupational therapists. J Allied Health. 2002;31(3):131–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ang SY, Dhaliwal SS, Ayre TC, Uthaman T, Fong KY, Tien CE, et al. Demographics and Personality Factors Associated with Burnout among Nurses in a Singapore Tertiary Hospital. Biomed Res Int. 2016;2016:6960184–. 10.1155/2016/6960184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gingras J, De Jonge LA, Purdy N. Prevalence of dietitian burnout. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics. 2010;23(3):238–43. 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2010.01062.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Annual Report 2019: Allied Health Professions Council; 2019 [Available from: https://www.healthprofessionals.gov.sg/docs/librariesprovider5/forms-and-downloads/ahpc-annual-report-2019_final.pdf.

- 25.Ministry of Health S. National Health Survey 2010. In: Statistics R, editor. 2011.

- 26.Jackson CMSE. MBI: Human Services Survey for Medical Personnel. Maslach Burnout Inventory. 2019.

- 27.Rotenstein LS, Torre M, Ramos MA, Rosales RC, Guille C, Sen S, et al. Prevalence of Burnout Among Physicians: A Systematic Review. JAMA. 2018;320(11):1131–50. 10.1001/jama.2018.12777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kurzthaler I, Kemmler G, Fleischhacker WW. [Burnout in physicians]. Neuropsychiatr. 2017;31(2):56–62. 10.1007/s40211-017-0225-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nishimura K, Nakamura F, Takegami M, Fukuhara S, Nakagawara J, Ogasawara K, et al. Cross-sectional survey of workload and burnout among Japanese physicians working in stroke care: the nationwide survey of acute stroke care capacity for proper designation of comprehensive stroke center in Japan (J-ASPECT) study. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2014;7(3):414–22. 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.113.000159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang Z, Xie Z, Dai J, Zhang L, Huang Y, Chen B. Physician burnout and its associated factors: a cross-sectional study in Shanghai. J Occup Health. 2014;56(1):73–83. 10.1539/joh.13-0108-oa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu H, Liu L, Wang Y, Gao F, Zhao X, Wang L. Factors associated with burnout among Chinese hospital doctors: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:786 10.1186/1471-2458-13-786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.See KC, Lim TK, Kua EH, Phua J, Chua GS, Ho KY. Stress and Burnout among Physicians: Prevalence and Risk Factors in a Singaporean Internal Medicine Programme. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2016;45(10):471–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dyrbye West, Shanafelt. Defining burnout as a dichotomous variable. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2009;24:440 10.1007/s11606-008-0876-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leiter MP, Maslach C. SIX AREAS OF WORKLIFE: A MODEL OF THE ORGANIZATIONAL CONTEXT OF BURNOUT. Journal of Health and Human Services Administration. 1999;21(4):472–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leiter M, Maslach C. Areas of Worklife: A Structured Approach to Organizational Predictors of Job Burnout. 3 2004. p. 91–134. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lourel M, Gueguen N. [A meta-analysis of job burnout using the MBI scale]. Encephale. 2007;33(6):947–53. 10.1016/j.encep.2006.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gascón S, Leiter MP, Stright N, Santed MA, Montero-Marín J, Andrés E, et al. A factor confirmation and convergent validity of the "areas of worklife scale" (AWS) to Spanish translation. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013;11:63–. 10.1186/1477-7525-11-63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mohr DC, Ho J, Duffecy J, Baron KG, Lehman KA, Jin L, et al. Perceived barriers to psychological treatments and their relationship to depression. Journal of clinical psychology. 2010;66(4):394–409. 10.1002/jclp.20659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sahlqvist S, Song Y, Bull F, Adams E, Preston J, Ogilvie D, et al. Effect of questionnaire length, personalisation and reminder type on response rate to a complex postal survey: randomised controlled trial. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11:62–. 10.1186/1471-2288-11-62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stein DJ, Phillips KA, Bolton D, Fulford KWM, Sadler JZ, Kendler KS. What is a mental/psychiatric disorder? From DSM-IV to DSM-V. Psychol Med. 2010;40(11):1759–65. 10.1017/S0033291709992261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ashraf F, Ahmad H, Shakeel M, Aftab S, Masood A. Mental health problems and psychological burnout in Medical Health Practitioners: A study of associations and triadic comorbidity. Pak J Med Sci. 2019;35(6):1558–64. 10.12669/pjms.35.6.444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Linden DVD, Keijsers GPJ, Eling P, Schaijk RV. Work stress and attentional difficulties: An initial study on burnout and cognitive failures. Work & Stress. 2005;19(1):23–36. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yao Y, Yao W, Wang W, Li H, Lan Y. Investigation of risk factors of psychological acceptance and burnout syndrome among nurses in China. Int J Nurs Pract. 2013;19(5):530–8. 10.1111/ijn.12103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dolnicar S, Grün B. Cross-cultural differences in survey response patterns. International Marketing Review. 2007;24(2):127–43. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sanchez-Burks J, Lee F, Choi I, Nisbett R, Zhao S, Koo J. Conversing across cultures: East-West communication styles in work and nonwork contexts. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;85(2):363–72. 10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fila M, Wilson M. Understanding Cross-Cultural Differences in the Work Stress Process: A Review and Theoretical Model. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kang K, Absher R, Granko RP. Evaluation of burnout among hospital and health-system pharmacists in North Carolina. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy. 2020;77(6):441–8. 10.1093/ajhp/zxz339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Scheibe S, Spieler I, Kuba K. An Older-Age Advantage? Emotion Regulation and Emotional Experience After a Day of Work. Work, Aging and Retirement. 2016;2 10.1093/workar/waw004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hsu H-C. Age Differences in Work Stress, Exhaustion, Well-Being, and Related Factors From an Ecological Perspective. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;16(1):50 10.3390/ijerph16010050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yu H, Jiang A, Shen J. Prevalence and predictors of compassion fatigue, burnout and compassion satisfaction among oncology nurses: A cross-sectional survey. Int J Nurs Stud. 2016;57:28–38. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2016.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mason VM, Leslie G, Clark K, Lyons P, Walke E, Butler C, et al. Compassion fatigue, moral distress, and work engagement in surgical intensive care unit trauma nurses: a pilot study. Dimens Crit Care Nurs. 2014;33(4):215–25. 10.1097/DCC.0000000000000056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Salyers MP, Bonfils KA, Luther L, Firmin RL, White DA, Adams EL, et al. The Relationship Between Professional Burnout and Quality and Safety in Healthcare: A Meta-Analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(4):475–82. 10.1007/s11606-016-3886-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Navarro-González D, Ayechu-Díaz A, Huarte-Labiano I. [Prevalence of burnout syndrome and its associated factors in Primary Care staff]. Semergen. 2015;41(4):191–8. 10.1016/j.semerg.2014.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dewa CS, Jacobs P, Thanh NX, Loong D. An estimate of the cost of burnout on early retirement and reduction in clinical hours of practicing physicians in Canada. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:254 10.1186/1472-6963-14-254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chiesa A, Serretti A. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for stress management in healthy people: a review and meta-analysis. J Altern Complement Med. 2009;15(5):593–600. 10.1089/acm.2008.0495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Grossman P, Niemann L, Schmidt S, Walach H. Mindfulness-based stress reduction and health benefits. A meta-analysis. J Psychosom Res. 2004;57(1):35–43. 10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00573-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.West CP, Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD. Physician burnout: contributors, consequences and solutions. Journal of Internal Medicine. 2018;283(6):516–29. 10.1111/joim.12752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Panigrahi A. Managing Stress at Workplace. Journal of Management Research and Analysis. 2017;3:154–60. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bhui K, Dinos S, Galant-Miecznikowska M, de Jongh B, Stansfeld S. Perceptions of work stress causes and effective interventions in employees working in public, private and non-governmental organisations: a qualitative study. BJPsych Bull. 2016;40(6):318–25. 10.1192/pb.bp.115.050823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Brand SL, Thompson Coon J, Fleming LE, Carroll L, Bethel A, Wyatt K. Whole-system approaches to improving the health and wellbeing of healthcare workers: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2017;12(12):e0188418 10.1371/journal.pone.0188418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pang S, Liu J, Mahesh M, Chua BY, Shahwan S, Lee SP, et al. Stigma among Singaporean youth: a cross-sectional study on adolescent attitudes towards serious mental illness and social tolerance in a multiethnic population. BMJ Open. 2017;7(10):e016432–e. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang Z, Sun K, Jatchavala C, Koh J, Chia Y, Bose J, et al. Overview of Stigma against Psychiatric Illnesses and Advancements of Anti-Stigma Activities in Six Asian Societies. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;17(1):280 10.3390/ijerph17010280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hoi SY, Ismail N, Ong LC, Kang J. Determining nurse staffing needs: the workload intensity measurement system. Journal of Nursing Management. 2010;18(1):44–53. 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2009.01045.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.MA LK. Medscape National Physician Burnout, Depression & Suicide Report 2019. Medscape Business of Medicine, Medicine MBo; 2019. January 16, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bakker AB, Van der Zee KI, Lewig KA, Dollard MF. The relationship between the Big Five personality factors and burnout: a study among volunteer counselors. J Soc Psychol. 2006;146(1):31–50. 10.3200/SOCP.146.1.31-50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kristensen TS, Borritz M, Villadsen E, Christensen KB. The Copenhagen Burnout Inventory: A new tool for the assessment of burnout. Work & Stress. 2005;19(3):192–207. [Google Scholar]