Abstract

Sensor, wearable, and remote patient monitoring technologies are typically used in conjunction with video and/or in-person care for a variety of interventions and care outcomes. This scoping review identifies clinical skills (i.e., competencies) needed to ensure quality care and approaches for organizations to implement and evaluate these technologies. The literature search focused on four concept areas: (1) competencies; (2) sensors, wearables, and remote patient monitoring; (3) mobile, asynchronous, and synchronous technologies; and (4) behavioral health. From 2846 potential references, two authors assessed abstracts for 2828 and, full text for 521, with 111 papers directly relevant to the concept areas. These new technologies integrate health, lifestyle, and clinical care, and they contextually change the culture of care and training—with more time for engagement, continuity of experience, and dynamic data for decision-making for both patients and clinicians. This poses challenges for users (e.g., keeping up, education/training, skills) and healthcare organizations. Based on the clinical studies and informed by clinical informatics, video, social media, and mobile health, a framework of competencies is proposed with three learner levels (novice/advanced beginner, competent/proficient, advanced/expert). Examples are provided to apply the competencies to care, and suggestions are offered on curricular methodologies, faculty development, and institutional practices (e-culture, professionalism, change). Some academic health centers and health systems may naturally assume that clinicians and systems are adapting, but clinical, technological, and administrative workflow—much less skill development—lags. Competencies need to be discrete, measurable, implemented, and evaluated to ensure the quality of care and integrate missions.

Keywords: Competencies, Monitoring, Training, Sensor, Wearable, Mobile health, Education, Implementation

Introduction

The number of connected wearable devices worldwide is expected to increase from 325 million in 2016 to 929 million by 2021, with 1 in 6 Americans using a wearable by 2021 (Piwek et al. 2016; Statistica 2018). Sensor, wearable, and remote patient monitoring (RPM) technologies are not only being integrated into care but are also increasingly used as the primary assessment and/or treatment modality (Hermens and Vollenbroek-Hutton 2008; Kvedar et al. 2014). Examples of their use include the collection of behavioral data, monitoring symptoms and adherence, and providing preventive and therapeutic interventions (Hilty et al. 2020; Luxton 2016; Silva et al. 2015; Steinhubl et al. 2013), making care more person- and patient-centered.

Sensor, wearable, and RPM technologies can transform care by moving from cross-sectional, manual transfer of data at a healthcare appointment to a 24 × 7, longitudinal framework (Areàn et al. 2016; Luxton 2016; Torous and Roberts 2017; Ariga et al. 2019). Enabling technologies, including cloud computing, ambient sensors, and artificial intelligence (AI) (e.g., machine learning (ML)), make the collection, processing, and sharing of data far more integrated and provides the opportunity for real-time feedback based on the ecology (home, health, lifestyle, social) of patients in natural settings (Seko et al. 2014). These data support “in-time” clinical decision support (Rohani et al. 2018; CDS) (Greenes et al. 2018) and automatic monitoring systems (Garcia-Ceja et al. 2018; National Academy of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine 2020). For example, digital phenotyping or behavioral markers can correlate multimodal sensor data, cognitions and depressive mood symptoms (Mohr et al. 2017) to detect illness and/or predict relapses.

The COVID-19 pandemic forced healthcare providers and systems to rapidly adapt their way of providing services. This also necessitated the need for rapidly attainment of technological capabilities and practical skills to assure competent, legal, and ethical practice. Fortunately, competencies are identified and training and knowledge resources for video-based telehealth services were well established and are generally accessible. However, training and competency resources for wearables, sensors, and remote monitoring technologies are presently limited, and the existing literature mostly describe methods, interventions, technologies, and care outcomes, rather than required clinical skills to use technologies (Hilty et al. 2020). Even clinicians familiar with telehealth may not see that these technologies are part of care, struggle to use them, or fail to realize their limitations (Hilty et al. 2018; Hilty et al. 2019a, b; Hilty et al. 2020). Graduate education, graduate education councils, and professional organizations/boards are providing guidance on use of technology but have not yet put forward competencies to ensure quality care for sensor, wearable, and RPM (Hilty et al. 2017; Maheu et al. 2019).

Given the increasing capabilities and benefits of sensors, wearables, and RPM and the current lack of identified competencies regarding use in clinical care, we aim to identify essential clinical skills and organize them into competencies within an educational theory, implementation science, and evaluation practices framework. We also consider that, like clinical interventions, competency implementation and effectiveness depend on assessment of acceptability, adoption, feasibility, costs, and sustainability (Proctor et al. 2010; Curran et al. 2012; Gargon et al. 2019; Marcolino et al. 2019). Identified and clarified competencies will help healthcare providers and systems adapt to and integrate these technologies into workflow and advance person—and patient-centered care.

This scoping review does not specifically address accreditation, licensing, and other regulatory boards/agencies but briefly summarizes position statements and guidelines on the integration of technology in clinical settings.

Methods

Approach

The original six-stage process (Arksey and O’Malley 2005) and updated modifications (Levac et al. 2010) for scoping reviews were used.

Research Question

This review addresses the overarching question: “What are the skills, attitudes, and knowledge that trainees and clinicians need to incorporate sensors, wearables and RPM into clinical practice?” It synthesizes clinical data based on research findings and considers current and target (i.e., future/ideal) states for those using sensors and wearable technologies.

Identifying Relevant Studies

The literature key word search was conducted for articles published through May 2020 using PubMed/Medline, American Psychological Association (APA) PsycNET, Cochrane, Embase, PsycINFO, Web of Science and Scopus, Science Citation Index, Social Sciences Citation Index, Telemedicine Information Exchange database, Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, and The Cochrane Library Controlled Trial Registry database. The initial search targeted four concept areas and associated search terms:

Competencies (adult, assessment, attitude, behavior, cognition, cognitive, curriculum(a), education(al), evaluation, framework, goals, graduate, improvement, knowledge, learner, learning, literacy, objectives, pedagogy, postgraduate, process, quality, resident, skill, student, supervision, teaching, trainee, training, milestones)

Sensor, wearable, and remote monitoring (actigraphy, activity, assessment, data, diagnosis, ecological, geographical, global, GPS, momentary, monitoring, passive, remote, storage, telemonitoring)

Mobile (android, app, asynchronous, cellular, device, e, ehealth, ebehavioral, e-behavioral, e-mental, health, mhealth, m-health, mobile, phone, smartphone, tablet, text), asynchronous (app, device, eConsult, e-consult, e-mail, mobile, monitoring, sensor, social media, store-and-forward, technology, text, wearable) and synchronous telepsychiatry, telebehavioral or telemental health (video, web-based, Internet)

Behavioral health (BH), psychiatry, and psychology (behavioral, client, clinician, care, diagnosis, emotional, health, intervention, medicine, mental, patient, services, psychiatry(ic), psychology(ical), therapist, treatment)

Study Selection

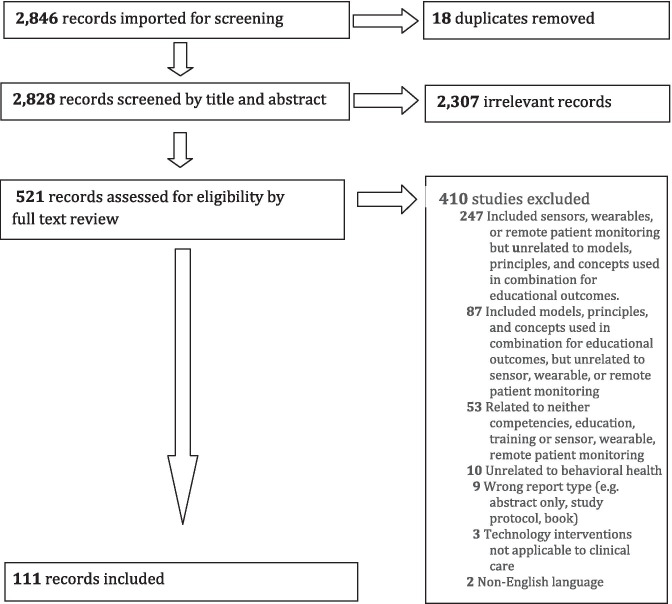

Two authors (DH, CA) searched then screened titles and abstracts for relevant studies. A third reviewer (EK) determined outcomes if disagreements occurred. Full-text articles were reviewed for final inclusion based on the key word search. Reviewers met at the beginning, midpoint, and final stages of review to discuss challenges and uncertainties and refine the search strategy. The flow diagram is in Fig. 1. Inclusion criteria were the terms in combination from the four concept areas: 1 and 2; 1, 2, and 4; or 1, 3, and 4. Exclusion criteria included the following: terms out of context (e.g., abstract use of competency, not mentioning a single skill, non-measurable behavior); data unrelated to BH; not applicable to clinical care; wrong report type (e.g., abstract, editorial, column, literature review); models, principles, and concepts (e.g., cognitive, milestones, patient) with no educational outcomes; non-English language; and other.

Fig. 1.

Search flowchart: diagram of papers reviewed, excluded, and selected

Data Charting

A data charting form was used to extract data, and notes were organized consistent with a narrative review or descriptive analytical method by each reviewer. The reviewers compared and consolidated information using a qualitative content analysis approach. The information was shared with selected experts (see below), their input summarized, and themes extracted.

Analysis, Reporting, and the Meaning of Findings

This phase organized results in a table, with skills outlined and parsed. There were so few papers that findings were reported individually since the depth of existing research was less than expected. Therefore, the reporting used excerpts from published framework tables. The Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Milestone framework was selected as it is well-known across medicine (ACGME 2013). Its six domains are patient care, medical knowledge, system-based practice, professionalism, practice-based learning and improvement, and interpersonal and communication skills. Two authors (DH, CA) examined the ACGME milestones from addiction medicine, clinical informatics, family medicine, internal medicine, psychiatry, and surgery, the CanMEDs roles for physicians (Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons Canada 2015), and the Coalition of Technology in Behavioral Science (CTiBS) telebehavioral health competency framework (Maheu et al. 2018) to build the current competency framework (Hilty et al. 2018). The content was organized into a 3-level learner system (i.e., novice/advanced beginner, competent/proficient, and advanced/expert) (Dreyfus and Dreyfus 1980; ACGME 2013; Hilty et al. 2015).

Expert Opinions

Expert opinions were solicited to review preliminary findings and suggest additional steps for improvement. A list of relevant experts was compiled from (1) recent regional and national presentations (e.g., American Telemedicine Association (ATA), American Psychiatric Association, American Association of Directors of Psychiatry Residency Training), (2) technology-related special interest groups of organizations, (3) national behavioral health organizations (e.g., CTiBS), and (4) authors of recent articles. The goal was to have representatives with mobile health and informatics expertise in behavioral analysis, counseling, couples/marriage/family, psychiatry/medicine, psychology, social work, and substance use professions.

Results

Expert Feedback

Fifty-two experts were invited from the Department of Veterans Affairs, Department of Defense, and academic institutions across four countries (Canada, India, Italy, USA). Disciplines included 29 (55.8%) psychiatrists, 16 (30.8%) psychologists, 3 (5.8%) engineers, 1 (1.9%) social worker, 1 (1.9%) occupational therapist, 1 (1.9%) dietitian, and 1 (1.9%) primary care physician.

Of the 52 experts invited, 26 responded and 24 (46.1%) participated, with 11 (45.8%) via email, 9 (37.5%) via 1 of 4 videoconference sessions, and 4 (16.7%) used both options. Feedback was collated based on previous work using consensus and modified Delphi processes (Hilty et al. 2018, Maheu et al. 2018). The 24 experts were asked to complete a brief 6-item Likert-scale survey and 15 (62.5%) responded. Results showed that the majority agreed or strongly agreed that:

“Table 1 was helpful in understanding the scope of what is currently being used” (100%).

“The competencies provided in Table 3 are in the ballpark and relatively ‘complete’” (85.7%).

3 “The length of Table 3 is good (not too long, not too short)” (78.6%).

“The subdomains in Table 3 are helpful” (92.9%).

“The behaviors/skills in Table 3 are learnable, teachable and measurable” (100%).

“The level of clarity and detail in Table 3 is adequate (not too much, not too little)” (87.6%).

Table 1.

Sensor, wearable, and remote patient monitoring technologies used for mobile health interventions

| Hardware (devices) | Device analytics |

|---|---|

| Blood pressure cuff | Usage, duration, frequency, quality of data transfer |

| Flexible sensors (i.e., patch, printed technology) | Usage, duration, frequency, quality of data transfer |

| Headband/headset | Usage, duration, frequency, quality of data transfer |

| Holter monitor | Usage, duration, frequency, quality of data transfer |

| Pulse oximeter | Usage, duration, frequency, quality of data transfer |

| Smartphone |

Usage, call logs: no., duration, frequency, missed SMS text logs: no. of frequency, characters |

| Textiles with imbedded sensors | Usage, duration, frequency, quality of data transfer |

| Wristband (i.e., smartwatch, band) | Usage, duration, frequency, quality of data transfer |

| Software (apps) | App analytics |

| Mobile app | Downloads, active users, sessions, average visit time, average screen views per visit, app retention (# return users), app churn (%age of users that stop using), app event tracking (actions users take in app (i.e., clicks, purchase), social media tracking |

| Sensors | Sensor analytics |

| Accelerometer | Autocorrelation, distance, speed, stillness/inactivity, time periods, vigorous activity, sleep sensor analytics |

| Actigraph | Physical movement, rest-activity cycles, circadian-rhythm activity cycles, steps |

| Air resistance sensor | Movement in wind field |

| Barometer | Air pressure |

| Barometric altimeter | Air pressure and altitude |

| Bluetooth | Nearby Bluetooth capable devices |

| Blood pressure monitor | Systolic and diastolic blood pressure |

| Camera | Eye gaze, light |

| Electrocardiogram (ECG) | Heart rate activity, heart rate variability |

| Electrodermal sensor | Skin conductance, galvanic skin response, psychogalvanic reflex, sympathetic skin response |

| Electroencephalogram (EEG) | Brain activity |

| Electroglottogram (EGG) | Vibration of vocal folds during voice production |

| Electromyogram (EMG) | Response of muscle against nerve stimulation |

| Electrooculography (EOG) | Drifting eye movements |

| Esophageal pH monitor | Frequency of stomach acid in gastrointestinal tract |

| Fingerprint | Distances and pattern between ridges on finger surface for biometric user verification |

| Global Positioning System (GPS) | Location, circadian rhythm, entropy, location clusters, movement duration, speed, proximity |

| Glucometer | Blood glucose |

| Gyroscope | Device’s rate of rotation |

| Heart rate monitor | Heart rate based on the difference between light intensity between blood vessel pulsations using LED light |

| Incident detection | Sudden deceleration |

| Infrared light | Distance/depth of objects in a spatial area |

| Light Detection and Ranging Sensor (LiDAR) | Distance/depth of objects in a spatial area |

| Light sensor | Ambient and direct light |

| Magnetometer | Geomagnetic field strength |

| Microphone | Loudness of sound, speech recognition, natural language processing, ambient sounds |

| Pedometer | Steps, sedentary activity |

| Photoplethysmogram (PPG) | Perfusion of blood to dermis and subcutaneous tissues of skin, often measured with pulse oximeter |

| Proximity sensor | Detection of any close object using infrared LED and light detector |

| Spirometer | Lung ventilation |

| Tactile sensor | Touch pressure and mapping |

| Thermometer | Skin temperature, ambient temperature |

| Time-of-flight (ToF) camera | Distance/depth of objects in a spatial area |

| Wi-Fi | Location based on service-set identifier (SSID) and signal strength of Wi-Fi networks |

Table 3.

Sensor, wearable, and remote monitoring competencies for clinicians and trainees organized by accreditation council of graduate medical education domains

| Area/topic | Novice/advanced beginner (ACGME milestone levels 1–2) | Competent/proficient (ACGME milestone levels 3–4) |

Advanced/expert (ACGME milestone level 5) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient care | |||

| Patient assessment/evaluation |

Change patient care approach to gather information, develop differential diagnosis and workup common conditions across populations, with supervision Educate patients on technology and inquire about preferences for use Screen use of mobile phone, apps, and for what (e.g., exercise, music, health care) Screen for ability to text, install/ update app and use software Ask for advice/consultation if concerns arise (e.g., data security) and document |

Change patient care approach to develop the diagnostic assessment, workup, and treatment plan independently, including secondary data, for common and complex conditions Evaluate digital literacy and interest in app, text (i.e., generic, motivational or tailored) or wearable Screen use of apps, Bluetooth, wearable (e.g., activity tracker, Holter monitor sensor-imbedded textile) and for what (e.g., glucometer for diabetes) Assess quality of current data via self-report, manual or other process on symptom (i.e., mood, activity, weight) |

Develop/adapt clinical pathways, guidelines and procedures for management of complex conditions for all points-of-service Use/teach/develop evidence-based strategies for clinical, technical, and administrative tasks • Consent, policy, and procedures • Populations and settings • Medico-legal considerations Train/supervise/consult to optimize assessment and flexibility (e.g., activity option to detect depression and/or mania; light, sound, proximity or physiological options) |

| Engagement and interpersonal skills |

Inquire about experience, comfort, and trust with technology Discuss impact on relationships with others, professional life and health care Field questions and requests for use and respond in time (e.g., video, in-person) or asynchronously, with supervision if needed Learn about informational, educational, motivational, tailored and other feeds to patients—and directionality—by discussing with patients, supervision, and if possible, by receiving examples as if a patient |

Encourage reflection on pros/cons (i.e., privacy) and purchases (e.g., compatibility) Gauge interest and capacity for learning to incorporate data/feedback, making a behavior change, responding to clinician/team, sharing new data and responding to clinical recommendations made based on that and other in time data Assess/weigh benefits (e.g., interaction, engagement, change) with concerns (e.g., privacy, being monitored) Assess impact on therapeutic relationship (e.g., communication, intimacy, boundaries Adjust approach to express empathy) and compare to other technologies and in-person care |

Provide guidance to patient, family, clinician and teams on effective communication Instruct on best ways to use technology • Simplicity with purpose • Match use with goal/intention and users’ capacity • Costs for effective use: time, technology, learning, teaching • Compare technologies’ impact on relationships Discuss/clarify expectations of participants Determine/teach alliance-building practices, prevention of problems and responses to barriers |

| Management and treatment planning |

Monitor/adjust ongoing use for issues (e.g., consider speech processing if physical problem) Make clear communications (e.g., text, notifications, symbols) Pilot/monitor/evaluate a technology for a specific purpose • Use supervision to adhere to health system policies and inquire about data feed to EHR • Clarify when data is reviewed “outside” regular appointments to set appropriate expectations |

Assess comfort with wearable in daily life (e.g., ease, fit with contact/water sports) Select option based on patient preference, feasibility and purpose • Sensor to monitor mood, or • Sensor, app and text reminders to self-report data in time (i.e., EMA) by structured (e.g., 9 am), event (e.g., pain) or signal (i.e., random) prompts Survey benefits and satisfaction of use and modify approach if necessary to match treatment objectives with patient preference and capacity |

Tailor recommendations to resources, culture and patient preference Research/disseminate procedures to prevent problems and manage clinical and administrative issues Offer practical, proven options to add Liaison between clinicians, informatics and system administrators • Improved workflow • Trouble-shoot and plan rollouts Teach best practices (e.g., evidence-based sensor or wearable within an evidence-based approach) |

| Administration and medico-legal issues: privacy, confidentiality, safety, data protection/integrity, and security |

Adhere to clinic, health system and professional requirements for in-person care Identify and adhere to relevant laws and regulations in the practice jurisdiction(s) of patient Clarify public or private access related to communication (e.g., email within EHR not non-HIPAA compliant systems) Seek supervision/advice, if needed, to learn the system’s path for use of a technology |

Synthesize applicable ethical guidelines Identify and articulate security and privacy concerns and solutions related to using technology in clinical practice Use standard language for these technologies for consent form, treatment plan and progress notes Identify, and support others to navigate, options for seeking technical help (e.g., mobile phone company, IT system) Verify identity and monitor security, privacy and confidentiality Apply in-person relevant laws and regulations in any/all jurisdiction(s) to these technologies and adjust clinical care |

Promote trust and responsiveness Teach/consult on in-person laws and regulations applied to technologies Develop legal, billing and regulatory strategies (e.g., emergencies) Update and consult with regulatory boards and health authorities Instruct on technology related to documentation, privacy, billing and reimbursement Develop standard language for these technologies for consent form, treatment plan and progress notes, particularly for non-routine telepractice; seek consultation |

| Procedures |

Encourage teaching demonstrations Verify technology type and fit with purpose used Ask for advice/consultation on current and potential options Check settings of software |

Identify how/if the integration of health technology may modify workflow and customize approach to maximize efficiency Enhance continuum of automated data Prevent, identify and manage obstacles Help patient and others obtain assistance Implement and validate options |

Customize technology options into workflow (e.g., EMA) Research/teach/consult on approaches for clinical quality (e.g., hard/software; accessories) Serve as primary assessor of options |

| Decision-making, synthesis, and information systems (IS) |

Effectively locate regular and wearable data in EHR Consider CDS tools of CDSS (e.g., for disease management) Identify basic principles of effective DS and decision science Demonstrate familiarity with how informatics tools coordinate, integrate and document care |

Prioritize EHR–compatible options to facilitate integration of information Adjust parameter(s) for decision-making and documentation using wearable data Help patients, learners and staff use decision support tools and customize when possible (e.g., mood and activity trigger for mania) Weigh accelerometer, actigraphy, GPS and sensor subtype (e.g., light, sound) options |

Teach how to use pre- and intra-platform data feeds into EHR Implement/evaluate patient (e.g., apps, messaging, symptom monitoring) and clinician (e.g., tools, algorithms) tools with clinical informatics Offer regular (e.g., generic/all patients) and customized (e.g., specific to stage, demographic, treatment plan) tools |

| Interpersonal and communication skills | |||

| Therapeutic relationship with patients and families |

Create non-judgmental, safe space Listen, ask questions, and organize information for patients Ask advice/consultation to improve care and resolve problems |

Build rapport that fosters trust, respect and understanding, including discussing problems and managing conflict Identify physical, cultural, psychological and social barriers to communication |

Role model effective, continuous, personal and professional relationships Coach flexibility/coordinate input to identify and resolve conflict Educate/consult on system workflow |

| Patient-centered care |

Ask about goals and preferences Identify positive and negative trends in patient populations using technology (e.g., generation Y) Develop skill with text and e-mail and avoid technical jargon |

Be of service to clarify technology questions Engage patient perspective and clarify goals, values, preferences and expectations to foster shared decision-making Ensure timely documentation, keeping of databases (e.g., problem list, registries) |

Seek family, cultural, language and technology consultants for advice Improve systems and communication with all care participants Develop policies/adapts “best practices” based on aggregate data |

| Interprofessional education (IPE) and team-based care (TBC) (e.g., e-consultation) |

Demonstrate the importance of the team for care and learning Define TBC (i.e., coordination, collaboration, teamwork) and share information Ask advice/consultation on conflicts and communication problems |

Build, re-design and lead team in to share data, share decisions and provide care (i.e., practice/lead TBC via wearables) Present, document and communicate in a clear, concise and organized manner Evaluate if/how communication and workflow are affected and adjust plans |

Teach/consult to IPE TBC via technology in terms of options, roles, practices, and communication Help others manage uncertainty/conflict on virtual care and communication Keep focus on patient during team, technology and system dilemmas |

| Cultural, diversity, and social determinants of health; attend to language issues |

Identify technology utilization patterns across demographic variables (age, ethnicity, race, national origin, literacy level, disability and identify inaccurate biases that are not supported by data Promote reflection and awareness how cultural, diversity issues, and social determinants of health might impact readiness to adopt, availability of, and access to health technology Identify potential biases regarding use and how these could impact delivery of care |

Utilize a cultural competency framework to understand how experiences with technology may impact integration into care Utilize strategies to increase technological cultural competency and decrease biases and/or stereotypes Determine patient regarding readiness of use, and if/how culture impacts use Adjust to preferences based on patient need/interest Observe, adjust and manage language and communication issues (e.g., emoticon use) |

Instruct/use components of a cultural formulation interview, if applicable Instruct on utilization of cultural competency frameworks to shift from ethnocentric to ethno-relative perceptive for use of health technology Instruct on how to adapt assessment and management approaches according to differences |

| Medical knowledge | |||

| Clinical care as it relates to the use of technology |

Learn • Benefits and barriers of the use of a given health technology • Diseases treated with wearables (e.g., depression, diabetes) Ask for advice/consultation for resources to learn |

Assess what works and does not, based on patient, technical and other factors Anticipate clinical requests/dilemmas • If data feed to patient, consider the type, frequency, formatting and “quantity” • Develop plan to review data on/off hours, make decision and communicate |

Research/teach new ways to facilitate/improve care (e.g., AI, machine learning, algorithms) Teach/consult on patients/diagnoses that require special preparation Evaluate need for 24-h, 7-day data review and decision-making |

| Fundamentals of technology and IS | Understand basics of components and IS (e.g., network, Internet, hardware, software, CPOE) workflow |

Understand complex components and healthcare IS (e.g., EHR, algorithms, databases) Reads on wearable, IS and human factors to answer questions and teach others |

Research/teach/consult enterprise-wide architecture, system integration Teach on input, process, output, feedback and control workflows |

| Definitions of technology |

Define SP/device and apps and list some pros/cons Understand “native app” on a SP/device versus others Recognize wearable components |

Define components (e.g., wearable, IS) and educate others on information and data flow from patient to clinician | Teach/consult on multiple SP/devices platforms, app varieties, and selection |

| Evidence-base (e.g., app) | Identify the level of evidence-base for the general technology category in improving health outcomes (i.e., Holter monitor in chronic heart disease) |

Describe the level of available evidence for the specific sensor/wearable technology to colleagues and patients • Content within the technology (interventions, algorithms, etc.) • Results of objective evaluations (i.e., published studies, quality of data) • Evaluate and employ the evidence base available in evidence-based treatment |

Instruct colleagues on best practices (e.g., guidelines) and approaches in the evaluation of the evidence-based for sensor/wearable technology Adapt/translate best practices and approaches from other health and behavioral health professions |

| Problem-solving and prevention |

Recognize and report problems Ask for advice/consultation |

Assess user requirements for fit, diagnose problems and provide technical assistance | Disseminate steps, approaches and/or techniques identify/solve problems |

| Decision support (DS) |

Understands how to help patient learn and for decision-making Pilot tools with supervision |

Use and evaluate ability of mH, SP/device and/or apps to help decision-making Compare manual and technology options |

Teach steps (i.e., gather information, weigh data and alternatives) Use principles and provide resources |

| Systems-based practice | |||

| Patient safety and quality improvement (QI) |

Learn safety/risk issues (e.g., physical, privacy) Use reporting systems for problems Discuss possible quality gaps for care delivery with supervisors Participate in chart review, case conference and other activities |

Outline factors/causal chains contributing to quality gaps, with management Identify problems/unintended consequences Recognize system error and activates others Participate in conferences on errors and uses structured tools (e.g., checklists, hand-off procedures) to prevent adverse events |

Match clinical workflow with IS and technology processes Analyze/teach aggregate data, root cause analysis, and change options Teach/consults on how to analyze, select and evaluate QI options (e.g., quality measures, error prevention) |

| Resource utilization |

Recognize need for efficient and equitable use of resources Inquire about providing options to use short- and/or long-term |

Recognize disparities and know the relative cost (e.g., technology, procedures) versus level of care/benefit to individuals, system and society |

Teach cost-effective, high-value care, using tools and IT for decision making Weigh current and future state quality of care (and life), as well as costs |

| Role in system navigation, workflow, and data |

Communicate data and workflow, via EHR to others for assistance Identify key elements for effective transitions across settings |

Participate in a workflow analysis Coordinate/lead complex transitions Provide patient and system consultations Use sensors/wearables to enhance continuity |

Interpret analyses/devise solutions Role model, advocate and improve transitions across systems Coach others to anticipate future needs |

| Practice-based learning | |||

| Evidence-base of a technology |

Access literature and learn/apply evidence-base specific to a technology intervention Demonstrate an understanding of the benefits and barriers of health technology to support health outcomes |

Evaluate and analyze the evidence-base and employ best current state practices Utilize best practices in interpretation of specific data (e.g., screen activity duration and physical activity, which predict depression severity better than distance travelled or number of SMS text messages) to support treatment goals |

Interpret/teach on disparate data, evidence and healthcare settings Evaluate options for multiple purposes and teach on specificity of data |

| Reflection for practice improvement (PI) | Evaluate regular/ manual versus technology-based care; improve performance with help from others and technology |

Ensure quality care by adjusting options Reflect consistently and integrate performance feedback (e.g., audit), peer input and practice/technology data |

Teach/consult on practice improvement standards and evaluation methods Consult/mentor others gaps between performance and expected practice |

| Learning practices | Add technology-based learning and use wearable to empathize |

Seek out technology-specific education Develop/promote/role model attitudes |

Determine best contexts/venues to emphasize technology resources |

| Professionalism | |||

| Accountability, ethics, and responsibility |

Quantify the impact of technology-based fatigue/stress Adhere to core professional and governmental guidelines for conduct (e.g., boundaries, being sensitive to having data around the clock across life settings/activities) Perform timely patient care (i.e., response to text within business hours, planning for off hours; reviewing data; documentation) Ask for advice/consultation to clarify and manage problems |

Reflect on well-being of self/others and role model healthy habits; inquire about technology fatigue Reflect on and follow institutional policies for conduct (e.g., texting or other asynchronous communication, use of data and its transfer) Perform timely patient care (e.g., analyzing in time data regularly rather than waiting for the next scheduled appointment; being responsive to emergent symptoms; administrative tasks and responsibilities Practice within scope and educate others |

Promote well-being among trainees, clinicians and IPE team members (e.g., offer sensors to monitor employee fitness, wellness and job performance) Role model/teach/consult ethical issues to maintain professional identity Monitor/report/provide feedback on technology errors/lapses Assess/advise if clinical responsibilities shift as care model changes, to ensure practice within license and regulations (e.g., state, federal) |

| Reflection, feedback, and growth |

Demonstrate openness to feedback, both regular and unsolicited Join professional community for peer support and input to embrace technology Learn from/participate in global evaluations to increase perspective |

Participate/lead activities in professional societies, patient advocacy groups and community service organizations Educate/evaluate how technology affects communication and care quality Seek 360-degree evaluation, performance audit and other methodologies |

Compare/contrast information across professions for growth opportunities Provide leadership to colleagues on organizational policy or curricula Promote technology as an opportunity for academic missions (e.g., informatics, competencies) |

| Scope of practice and therapeutic objective(s) |

Attend to in-person scope and learn with supervision how a technology may change it and responsibilities Demonstrate flexibility and openness to learning, but keep focus on shared primary objective of care |

Apply in-person and video principles of scope to other technologies to anticipate and prevent problems Educate patient on reasonable/acceptable options and the direct/indirect potential risks of its use |

Teach/consult on in-person and technology adaptations Evaluate high-risk technologies and use in complex populations, particularly with regard to legal, regulatory and fiscal issues |

app application, AI artificial intelligence, CDS clinical decision support, CDSS clinical decision support system, CPOE computerized provider order entry, EMA ecological momentary assessment, EHR electronic health record, ED emergency department, IS information system, IT information technology, mH mobile health, PCP primary care provider, SP smartphone

The abstract, tables, and manuscript were edited based on the feedback.

Literature

Figure 1 shows that from a total of 2846 potential references, two authors (DH, CA) found 2828 eligible for title/abstract review, and 521 for full text review. The majority of studies were excluded due to terms used out of review context and reviewing references revealed more papers. The final number of papers included in the review was 111 (highlighted in grey in References).

Sensor, Wearable, and Remote Patient Monitoring Technologies Evidence-Based

Technologies

A variety of technologies were used for mood and anxiety disorders (Hilty et al. 2020), with smartphones (66.3%), wristbands or smartwatches (22.8%), and holters (6.5%) the most common (Table 1). The most common sensors (e.g., smartwatches, heart rate monitors, smart glasses; L’Hommedieu et al. 2019) were accelerometers (50.0%), phones (39.1%), GPS (35.9%), microphones (30.4%), actigraphs (25.0%), and electrocardiograms (ECG) (25.0%), and implantable medical devices are used for other conditions (Ferguson and Redish 2011). The sensors convert human biological data into digital signals for a microprocessor to interpret, and then, the flow of information continues (Heikenfeld Jajack et al. 2018).

Most studies used instruments relevant to their application domain, including questionnaires, ecologic momentary assessment (EMA), and clinician assessments. These are objective, accurate (although not always validated as such), and can validate self-report data (e.g., Fitbit). There was significant variation in the timing of validation measures, from one-time measures to many per day or pre-post assessments. For data processing, software applications that communicated with a remote server were used in most studies to save data for processing and, at times, provide within-study feedback to participants.

Remote monitoring and remotely supervised treatment or training (RMT) uses complex distributed information and communication technology (ICT) systems to measure, transport, and store information (ATA 2014). Feedback helps clinicians with clinical decision support and to increase patient awareness of their health status, gives them a feeling of safety and motivate, and enables them to change/improve their health status (Maddison Cartledge et al. 2019).

Evidence-Based

One major subset of studies focused on feedback in the form of applications that display graphs representing mental health status (Abdullah et al. 2016; Faurholt-Jepsen et al. 2016). Many studies found that motivational messages (e.g., specific suggestion for action), tailored messages (e.g., specific to disease, stage of progress, demographic information, treatment plan), and health professional contact-enhanced therapeutic engagement are generally more effective than receiving (typically numeric) health measure feedback (Ma et al. 2014). These individualized (or similar user) models appear more effective (Wahle et al. 2016) than generalized models (e.g., generic message for a depression cohort). Individualized design of training and exercise programs may be helpful to maximize the improvements in performance and avoid risks (Cardinale and Varley 2017).

Another area of research is related to validating diagnosis and/or determining predictors of outcomes. Within the depression studies, cell tower identification (i.e., geographic movement), screen active duration, and activity measurement have the strongest linkage with depression severity compared with distance travelled and SMS text message received, whereas manic patients have longer calls, more messages sent, and more travel (Hilty et al. 2020). For bipolar disorder, studies generally support the interpretation of sensed data by employing traditional measures or assessments for depression (e.g., PHQ-8 or PHQ-9 self-report instruments) and clinician assessment/batteries (Faurholt-Jepsen et al. 2016). Mood and anxiety studies use algorithms to interpret or predict participant’s status (e.g., support vector machine, naïve Bayes classifiers, decision trees, random forests, linear regression, Bayesian networks, logistic regression, and other machine learning methods) (Elgendi and Menon 2019). The College Sleep Project used multi-modal sensors (physiological, behavioral, environmental, social) from smartphones to identify associations among and develop predictors for sleep behaviors, stress, mental health, and academic performance (Sano et al. 2015).

Behavioral Health Profession and International Organization Position Statements and Guidelines on Telehealth and E-health

Our current review builds on past comparisons (Hilty et al. 2017; Hilty et al. 2018; Hilty et al. 2020) of health and behavioral health professional organizations’ documents that pertain to technologies by focusing on sensors and wearables (Table 2). US and Canadian guidelines were reviewed (American Psychiatric Association 2014, 2017, 2018; American Psychiatric Association-ATA 2018; ATA 2009, 2013, 2017; Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons Canada 2015). Only the ATA child and adolescent guideline mentions monitoring and wearables (ATA 2017). The only competencies have come from individual research groups for video (Hilty et al. 2015, 2018), social media (Hilty et al. 2018; Zalpuri et al. 2018), mobile health (Hilty et al. 2019a, b; Hilty et al. 2020), and asynchronous (Hilty et al. 2019a, b; Hilty et al. 2020) technologies.

Table 2.

A comparison of telebehavioral guidelines and position statements across professions related to asynchronous technologies

| Domain/competency | Psychology (Australian, British, Canadian and U.S.) | ACA | Social work | C/MFT | Psychiatry (individual researchers > U.S. or Canadian) | ATA adult | ATA child and adolescent | CTIBS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Synchronous video | ||||||||

| All AGCME domains in summary |

✓ - ✓ ✓ |

✓ - ✓ ✓ |

✓ | ✓ |

✓ ✓ ✓ - ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ |

✓ ✓ | ✓ ✓ |

✓ ✓ ✓ - ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ |

| Asynchronous technologies | ||||||||

| Apps | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ | ✓ | ✓ ✓ ✓ | |||

| Asynchronous | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ ✓ | ||

| Device (mobile/smart) | ✓a | ✓ | ✓ ✓ | ✓ ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ ✓ | |

| E-consultation | ✓a | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ ✓ | ✓ ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Mobile/portable | ✓ | ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ | ✓ | ✓ ✓ ✓ | ||||

| Monitoring (remote) | ||||||||

| Sensor | ✓b | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ ✓ | ||||

| Social media | ✓ ✓ | ✓ ✓ | ✓ ✓ | ✓ | ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ | ✓ | ✓ ✓ ✓ | |

| Store-and-forward | ✓ ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Text | ✓a | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ | ✓ | ✓ ✓ ✓ | |

| ✓ ✓b | ||||||||

| Wearable | ✓b | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Web-based | ✓ | |||||||

✓, important, mentioned and terminology defined; ✓✓, important, discussed in-depth; ✓✓✓, limited scope of measureable behaviors/competencies based on evidence and/or consensus; ✓✓✓✓, broad scope and depth of measureable behaviors/competencies based on evidence and/or consensus

ACA American Counseling Association, C/MFT Couples/Marriage Family Therapists, CTiBS Coalition for Technology in Behavioral Science

aAustralian Psychological Society only

bCanadian Psychological Association only

Contributions from behavioral health come from American, Australian, British, and Canadian psychology associations (APA 2013, 2019; Association of State and Provincial Psychology Boards 2014; Australian Psychological Society 2011; British Association for Counselling and Psychotherapy 2019; Canadian Psychological Association 2006; Goss et al. 2001) and U.S. social work (National Association of Social Workers 2017), counseling (American Counseling Association 2014; Canadian Counselling and Psychotherapy Association 2019), and couples/marriage family therapy (American Association for Marriage and Family Therapy 2015; American Association for Marriage and Family Therapy Regulatory Board 2016). The most commonly discussed technologies were e-mail and social media, followed by texting, with note of sensors and wearables by the Canadians (sensor, text, wearable) and Australians (device, e-consultation, mobile, text). Only the CTiBS competencies for telebehavioral health (Maheu et al. 2018) mentioned briefly sensors and wearables as part of a mobile health domain.

Institutional and professional organizations are overseen by accreditation, licensing and boards/agencies to provide guidance to ensure professionals provide care proficiently, legally and ethically. They proactively inform and collaborate with regulatory boards/agencies to address broad, overarching issues related to quality of care, standards for practice and maintenance of certification. They also employ competency benchmarks (APA 2012), skills-based exams, and decision-making exams (Hilty et al. 2020). They tend to make changes incrementally and adjust to sentinel events one-by-one.

Based on the current review, the landscape related to sensors and wearables reveals several themes regarding mobile health technologies, some of which are concerning with respect to competencies (Seppälä et al. 2019; Hilty et al. 2020). First, there is incremental adaptation of technology added to care systems with the assumption that it is just part of routine delivery rather than a new form of care (Hilty et al. 2013). Second, innovation is siloed within research programs and/or pilot projects. Third, most innovation is related to video, e-mail, and electronic health record (EHR) portals, not mobile health, sensors, and wearables. Fourth, few if any academic health centers have yet to create or adopt technology competencies or install mobile health (apps, text mobile phones) and wearable sensors into clinical decision support systems (CDSS), so impact is limited.

Shifting Perspectives for Patients, Clinicians, Teams, and Systems

Overview

The future state is an “open” mobile health architecture that offers universal data standards and a global interconnected network, with patient and clinician facing dashboards, rather than apps and other technologies limited by siloed or un-integrated proprietary data, management, and analytic tools (Ramkumar et al. 2019). Clinicians may have to reconsider patient’s skills, needs, and preferences to determine suitability for any specific technology as part of the consent process, and again later, when needs/preferences among available choices are understood or care plans change (Hilty et al. 2015; Maheu et al. 2018).

The impact of new technology has increased exponentially (Mermelstein et al. 2017; Sturmberg et al. 2014), with users currently compared as digital natives versus immigrants (Wang et al. 2013). A broader perspective from education, business, health care, and other disciplines suggests that technology plays different roles along an augmentation-exploration-innovation spectrum (Hilty et al. 2019). It may affirm, complement, accentuate, and augment what people do. Further, it may help people explore, engage, and experiment with ideas and partners in new ways, “changing” dynamics or facilitating a different culture, making new things possible.

Paradigm Shifts in Integrating Sensors and Wearables with In-person and Synchronous Care

The first paradigm shift is including technology in traditional health care or adapting that care to technology. This can be difficult for clinicians, training programs, and health systems. The first example of this shift was from in-person to synchronous and asynchronous video (Yellowlees et al. 2018; Hilty et al. 2020). Even low-cost systems can facilitate engagement and “social presence” for participants to share a virtual space, get to know one another, and discuss complex issues (Hilty, Nesbitt et al. 2002). The most important goal with technology is to keep the exchange of information, clarity, responsiveness, and comfort close to real-time experiences (Hilty et al. 2020). Empathy, positive regard, and genuineness play a critical role in therapy effectiveness (Grekin et al. 2019; Kemp et al. 2020). Clinicians must adjust techniques to inquire, engage, communicate, and listen effectively (Hilty et al. 2020).

A second shift is correspondence via technology outside the office visit creating a new sense of continuity, connection, and exchange of information. Patients, clinicians, and healthcare researchers are trying to understand how this affects the therapeutic frame, communication, boundaries, and trust (Hilty et al. 2020; Li et al. 2016). A primary example of this is social media, which became a key part of patients’ lives, and by default part of care, though many clinicians did not understand or embrace it (Hilty et al. 2018). Asynchronous communications have a sense of immediacy and interaction that build “trust” but, despite a sense of control, are not always clear and can lead to ill-intended consequences (Hilty et al. 2020). Administrative planning and training can manage risks (e.g., privacy, self-disclosure, cyberbullying) (Armontrout et al. 2016; Joshi et al. 2019).

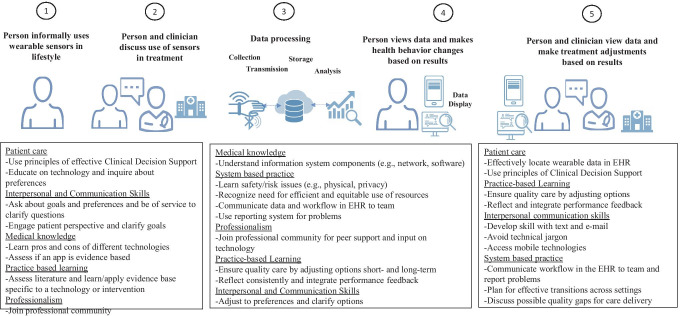

A third shift is how to integrate mobile health, text, sensors, social media, and other technologies into clinical workflow for a virtual office. As apps became popular, clinicians adapted more quickly, and now clinicians need to assess sensors and wearables for potential applications (e.g., entertainment, health care, behavioral health) (Hilty et al. 2019b). This is a key part of the therapeutic relationship, and there is a flow to the process (Fig. 2). For example, in-time data collection can alert a patient to self-assess mood regularly, with data transmitted automatically to the clinician. In-time data collection (e.g., EMA) is more valid, reliable, and meaningful than sporadic, retrospective reflection/recall, as long as the time to input data does not adversely impact patient motivation (Russell and Gajos 2020). This process also facilitates in-time clinical decision-making by adding a cognitive scaffolding and analytic methods that enhance confidence and skills (Clark 2013; Luxton 2016) (e.g., mood and medication management) (Thompson et al. 2014). This requires flexibility, between visit review of data, and supervision for trainees.

Fig. 2.

Data flow visualization from and applicable competency domains across clinical workflow

A fourth shift relates to organizational leadership and change. Many organizations are reluctant to change regarding technology despite telehealth’s impact (Hilty et al. 2020). Progressive businesses integrate core divisions (e.g., research, operations, finance) with information technology (IT) (i.e., shared IT-business framework) to leverage knowledge and capital (Ray et al. 2007). This paradigm has been applied to telehealth to organize/integrate health care rather than adding technology to existing systems (Hilty et al. 2019), suggesting that organizing care with technology will have better outcomes than appending it to health care.

Impact on Clinical, Technological, and Administrative Workflows

For healthcare systems, these new technologies have many implications, including clinical, technical, policy, and other administrative workflows to comply with legal and ethical mandates (American Psychiatric Association-ATA 2018; ATA 2009, 2013, 2017). Technological factors relate to access (i.e., equipment, software) and ease of use, as well as participant literacy and skill. Some tools are only new versions of in-person tools (e.g., smartwatch to collect photoplethysmography (PPG) signals to capture heart rate variability, an index associated with overall emotional and physical well-being), while other technologies shift perspectives dramatically for trainees and clinicians, requiring new competencies. For example, speech recognition and natural language processing (NLP) simplify data processing with a more natural and transparent interaction experience (e.g., Siri, Watson) (Witt et al. 2019) but require new skills.

The PACMAD (People at the Centre of Mobile Application Development) usability model emphasizes seven factors: effectiveness, efficacy, satisfaction, learnability, memorability, errors, and cognitive load (Harrison et al. 2013). A structured approach is needed to fit a sensor, app, or other technology to a user and evaluate its success, impact and value (Caulfield et al. 2019). Steps could include requirement definition (e.g., unobtrusive, body location, degree of measurement accuracy), device search, device evaluation criteria (e.g., human factor measurement tested, regulatory compliance, technical specifications/capabilities), and post-implementation evaluation of fit (or alternatively, use in others who are very similar to a give patient). While most clinicians currently lack these skills, the increased need to offer RPM and telehealth options during the COVID-19 pandemic has now increased utilization, and training should be based on established competencies when possible.

Many fields use human-centered co-design studios to develop and pre-test technological options (Hetrick et al. 2018; Russell et al. 2020). Focus groups, studies, and surveys have suggested ways to improve technology in health care through involvement and supervision of caregiver(s), better visuals, more immediate chat options and feedback between patients and clinicians, gamification and incentives, reminder alarms/alerts (MacKintosh et al. 2019), and seamless integration of data from apps and mobile phones into patient portals (Bennett et al. 2012).

Remote monitoring helps clinicians and trainees see or experience how important technology is for patients (e.g., safety, empowerment, control, convenience), healthcare systems (outpatient/in home, stepped care), and payers (e.g., insurance, cost reduction) (Hermens et al. 2008; Ramkumar et al. 2019). More importantly, they see how interprofessional teams can be effective, efficient, and collaborative in sharing expertise and roles (e.g., care coordinators, nurses) (Barisone et al. 2018; Winters et al. 2018).

Ethical issues related to informed consent, privacy, and data security are important to consider. Ethical issues concern providing and obtaining adequate informed consent from participants, information quality in monitoring apps, personal privacy, and international legal and cultural differences (Luxton 2016; Torous and Roberts 2017). For example, it is possible that with a combination of a great deal of physiological data, a person could theoretically be identifiable. Mobile health may also create privacy issues associated with third parties (e.g., images and sounds from nonparticipants). All of these issues should be evaluated during the technology design process so appropriate encryption and data security features are built in (Luxton et al. 2012). Other technological challenges include sensor precision, power, location, analytic procedure, communication, data acquisition, and processing, as well as performance issues between devices, accuracy of date versus gold standards, error rates, and other parameters (Patel et al. 2002).

Sensor and wearable technologies have not been adopted significantly to date, partly due to security, affordability, user-friendliness, compatibility with EHR systems (Bennett et al. 2012; Dinh-Le et al.2019), and financial and policy issues that have not been resolved even though virtual care codes were approved for some services in the U.S. in 2019 (Hilty et al. 2020). Manufacturers and healthcare providers also must consider certification and approval requirements related to US, European Union, and other international regulatory standards (Loncar-Turukalo et al. 2019; Ravizza De Maria et al. 2019).

Health System and Institutional Approaches to Sensor and Wearable Competencies

Overview

Competency-based education focuses on clinical skill development in addition to knowledge acquisition (Iobst et al. 2010). The Clinical Informatics Milestones have been suggested for the EHR, data use (e.g., safety, quality, privacy), and CDS (Hersh et al. 2014). These were followed by adult telepsychiatry (Hilty et al. 2015, 2018), CTiBS’ telebehavioral health (Maheu et al. 2018), social media (Hilty et al. 2018; Zalpuri et al. 2018), mobile health (Hilty et al. 2019a; Hilty et al. 2020), and asynchronous (Hilty et al. 2020) competency sets. They include suggestions for training, faculty development, and institutional change and use the ACGME domains (ACGME 2013) with novice/advanced beginner, competent/proficient, and expert levels. Sensors and wearables have yet to be addressed.

The slow integration of telehealth into clinical care and curricula may be a revealing story for sensors and wearables (Hilty et al. 2019). Interest by interns, residents, and fellows has significantly increased, but trainees across behavioral health have attributed inadequate experience, false beliefs of teachers, and speculation about technology efficacy as key limiting factors (Glover et al. 2013; Hilty et al. 2015). Residents have had valuable tele-experiences in establishing rapport and engaging with patients, working collaboratively, identifying different approaches used, and becoming aware of how to handle complex cases (Teshima et al. 2016). Many experts have called for more work in telehealth education (Balon et al. 2015; Sunderji et al. 2015; Crawford et al. 2016; Khan and Ramtekkar 2019), and one survey revealed only 21 of 46 programs have a telehealth curriculum or informal clinical experience (Hoffman and Kane 2015). The Veterans Affairs’ national telemental health training program provides a model, with comprehensive web-based modules, national satellite broadcasts, a national teleconferenced journal club, interactive Internet applications, and live real-time simulated remote competency assessments (Gifford et al. 2012; Godleski 2012).

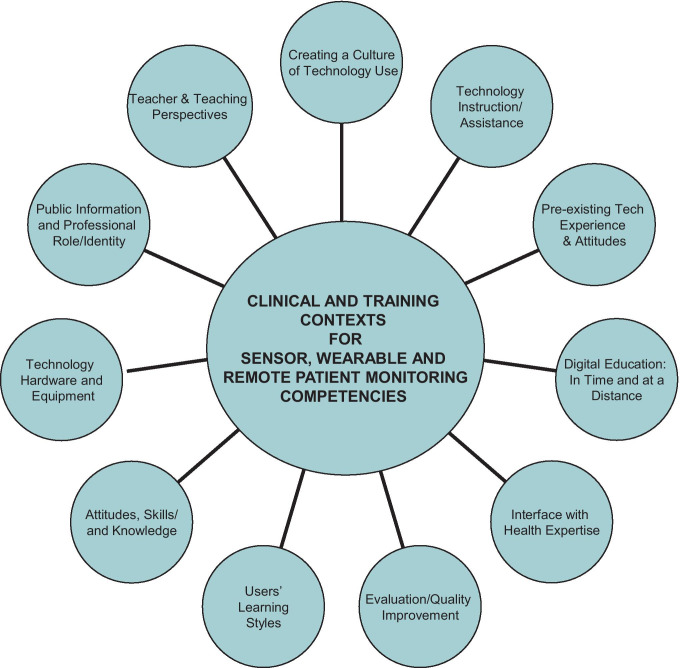

Mobile health, social media, and informatics practices require more substantial planning and organizational change (Hilty et al. 2018; Hilty et al. 2019a, b, 2020; Hilty et al. 2020). Building on the IT-business model, this requires a multi-dimensional shift in training and clinical culture (Fig. 3). It requires positive attitudes in clinicians, teachers, and faculty to positively support learners (Mostaghimi et al. 2017) and reflect on practice change, share information, and adjust curriculum (e.g., courses, rotations, supervisory approaches). For sensors and wearables, health systems need to integrate objective data into clinical workflow (Dogan et al. 2017). EHRs need to develop comprehensive use-case scenarios that include details regarding the type of data needed to support care processes, clinical and community-based personnel, and standardized interventions that are already in place or need to be established to best utilize the information to be collected and integrated. These use-case scenarios should also be specific for different clinical populations (Lobelo et al. 2016).

Fig. 3.

Clinical and training contexts for sensor, wearable, and remote patient monitoring competencies

Sensor and wearable curricular approaches are similar to those for mobile health and asynchronous competencies (Hilty, Chan et al. 2019a, b, 2020; Hilty et al. 2020). In addition to the sensors being the focus (i.e., content) of these competencies, sensors can shape the learning process, teaching learners, and simultaneously giving them experience (e.g., armband to measure proper hand washing via signal processing and ML) (Kutafina et al. 2015). Learning analytics can be applied to cluster, depict, and process data to support a number of objectives (González-Crespo and Burgos 2019), since teachers need to reshape the course plan for different learners (e.g., styles, motivation, performance) and integrate that information with real-time analytical information to supervise, assess, adapt, and offer feedback. Sensors and wearables can be applied to a wide range of educational contexts, including but not limited to:

learning management systems (LMS) or content management systems (CMS) that process user data collected

studying relationships between type of device from which users access LMS and how it affects performance

live or virtual reality (VR)-based sessions with teams or patients so oral and body language skills are shaped and improved

game-based learning with virtual/augmented reality to improve procedures

recommendations to users (e.g., explore impact of order given, behavioral response, impact of choices on engagement via algorithm) (Baldominos and Quintana 2019; Roque et al. 2019)

Many healthcare institutions already provide students with iPads, smartphones, and other technologies (Gaglani and Topol 2014), so adding sensors and wearables is the next logical step, allowing for enhanced guidance from preceptors on technique and interpretation of findings. Inter-institutional collaborations also improve teaching, reduce costs, and integrate a variety of patient populations (Metter et al. 2006).

Sensor, Wearable, and Remote Patient Monitoring Competencies

The proposed framework (Table 3; domains vertically, learner levels horizontally) uses the six ACGME domains (ACGME 2013). Most content came from the telepsychiatry (general themes) (Hilty et al. 2015; Hilty et al. 2018), social media (privacy, security, professionalism) (Hilty et al. 2018; Zalpuri et al. 2018), mobile health (CDS, mobile phones, apps) (Hilty et al. 2019a, b, 2020), and asynchronous care (procedures, resource utilization, role in system navigation and workflow, and accountability, ethics, and responsibility) competencies (Torous and Roberts 2017; Hilty et al. 2020). The CTiBS (Hilty et al. 2017; Maheu et al. 2018), clinical informatics (Torous et al. 2017), and the Clinical Informatics Milestones (ACGME 2013) were also helpful.

Examples are:

Within patient care, the subdomains are patient assessment/evaluation, engagement and interpersonal skills, management and treatment planning, administration and medico-legal issues, procedures, and clinical decision-making, synthesis, and information systems (IS). One challenge is optimizing the match between the sensor and a specific application context, so a structured approach for requirements and evaluation would help a novice/advanced beginner. A healthy middle-aged adult engaging in employee wellness in a large organization will have different needs than a 70-year-old at home suffering from depression (Caulfield et al. 2019). They require different devices, indifferent sensor locations (wrist versus wearable vest), steps for synchronization (from own device to data aggregator), and a software change (from “reliable” to validated measurement). This may proceed smoothly if the healthcare system prepares options, has staff to assist, and trains faculty supervisors.

Also in patient care, a novice/advanced beginner should understand what a device is used for (e.g., behavior, physiology), its capacity (i.e., connection with databases), weigh the value of data, monitor/adjust treatment with supervision, and help patients reflect on use and output. A supervisor would need to adjust teaching, supervision/availability, and workflow (e.g., between visit documentation) based on the technology, learner skill level, and patient care outcomes. The competent/proficient clinician would base the selection of a wearable on patient preference, skill, and need (i.e., purpose), and show proficiency when moving between regular to synchronous, continuous care. They need to remember that the therapeutic frame includes in-person, video, and mobile health engagement, in order to create a positive virtual environment.

Under professionalism, subdomains include attitude, accountability, integrity and ethics, reflection, feedback, and growth. A novice/advanced beginner would be open to learning and adhere to professional guidelines (i.e., timely response to text, documentation). Learning boundaries may come naturally and require small but important adjustments (e.g., learning to see if self-assessments match data reports). A competent/proficient clinician would understand boundaries/ethical dilemmas with technological options and how to engage patients (e.g., sensitively inquire how it feels to have self-assessments double-checked with in-time data or behavior). If symptoms like suicidal thoughts or worsening depression appear linked to a particular geographic setting, the clinician may ask if the patient has noticed a pattern before simply announcing a conclusion. An advanced/expert clinician would provide leadership, teaching, and consultation, including assessing/advising if clinical responsibilities shift as care models changes to ensure practice within license and regulations (e.g., how often clinicians are expected to check data inflow and make decisions).

Teaching, Evaluation and Assessment: Clinical Care and Supervision in Training

Teaching sensor and wearable competencies successfully will require a mix of methods layered and adjusted for increasing skill level over time. This requires evaluation methods that can determine whether competencies have been achieved and for supervisors to provide formative feedback to learners (Table 4) (Tekian et al. 2015). The following case examples illustrate approaches to the teaching and supervising sensor and wearable competencies.

Within the patient care, one subdomain is patient assessment/evaluation. An academic medical center may decide to offer a weight management program to support patient goals by collecting sensor data on step count via an app. Novice/advanced beginners must be able to screen for technology use among eligible patients, educate patients on the use of technology, and monitor/adjust treatment with supervision. The competent/proficient clinician would teach in the curricular for trainees, seminars for interprofessional teams, and on supervisory rounds. A case or simulation could introduce concepts to learners and be linked to clinical workflow. The advanced/expert clinician would develop the educational approach, train teachers, and evaluate process of change, aggregate sensor data, and on clinical quality and cost-effectiveness outcomes.

Within the patient care, the clinical decision-making, synthesis, and IS subdomain focus on EHR and documentation (Table 3). A novice/beginner should effectively read and write in the EHR, consider CDS tools, and use tools to coordinate and document key care events (Fig. 2). If a sensor is inputting data into the EHR between appointments, will the trainee know to review it or understand prompts? Can they adjust treatment plans “in time”, or do they need the supervisor to adjust practices (Table 4)? Typically, trainees wait and review data in a 1-h, scheduled, weekly supervision of a caseload, but “curbside consultations” are frequently needed. This could work better with two, half-hour meetings, more “walk-in” supervision time or more flexible coverage policies (see professional reflection, monitoring and hygiene related to patient care and supervision and subdomain in-time supervision in-person or at distance on critical incident). A competent/proficient clinician should select a wearable to ensure good usability, durability, interactivity (e.g., chat, feedback), and fit with the EHR for decision-making and documentation. They educate patients, trainees, and staff on tools’ pros/cons, and the meaning of the data, and like supervisors, has to consider questions like, “What is reasonable checking of data between visits? What standard of care is sought for?”

Case-based learning (Table 4) uses real life examples or vignettes in seminar, site-based case conferences and other presentations. Trainee’s experience with patients could be presented in a weekly group supervision or site-based case conference with an interprofessional team. Interactive methods like role-play using peers can highlight issues, practice communication skills, identify options for decisions, and propose solutions for patients. This provides an opportunity to build and/or solidify the trainee role as an educator (Table 4), working with an interprofessional team and adapting communication skills to multiple people.

Table 4.

Teaching, assessment and evaluation methods for sensor, wearable and remote patient monitoring clinical competencies

| Learning objective by learner level | Novice/advanced beginner | Competent/proficient | Advanced/expert |

|---|---|---|---|

| Learning and applying new wearable technology to practice | |||

| Learning objective* applied to wearable type | • Remember and understand wearable hardware, software, and sensors |

• Apply wearable hardware, software, and sensors • Analyze impact of wearable type on patient care |

• Understand, apply, and analyze wearables new to provider • Evaluate impact of wearable hardware, software, or sensors on patient outcomes |

| Teaching style | Didactic (e.g., classroom lecture style, grand rounds, continuing education training) | Didactic (e.g., classroom lecture style, grand rounds, continuing education training) | Didactic (e.g., classroom lecture style, grand rounds, continuing education training) |

| Competency domain(s) |

• Medical knowledge • Patient care • Systems-based practice |

• Medical knowledge • Patient care • Systems-based practice • Practice-based learning • Professionalism • Interpersonal and communication skills |

• Patient care • Systems-based practice • Practice-based learning • Professionalism • Interpersonal and communication skills |

| Assessment methods | • Written test (multiple-choice/short answer) |

• Written test (multiple-choice/short answer) • Oral presentation |

• Oral presentation • Clinical outcomes • Chart review |

| Matching wearable to patient | |||

| Learning objective* applied to wearable type | • Understand and apply correct wearable type to clinical disorder | • Apply and evaluate impact of wearable type on patient care |

• Evaluate the impact of new wearable type of patient care and outcomes • Evaluate impact of new wearable has on patient rapport |

| Teaching style | Applied learning with peers (e.g., “flipped” classroom; supervision, faculty; observing faculty, group observation, or co-Interviewing) | Applied learning with peers (e.g., “flipped” classroom; supervision, faculty; observing faculty, group observation, or co-interviewing) | Applied learning with peers (e.g., “flipped” classroom; supervision, faculty; observing faculty, group observation, or co-Interviewing) |

| Competency domain(s) |

• Medical knowledge • Patient care • Systems-based practice |

• Medical knowledge • Patient care • Systems-based practice • Practice-based learning |

• Patient care • Systems-based practice • Interpersonal and Communicate Skill • Professionalism |

| Assessment methods |

-Written test (multiple-choice/short answer) -Oral presentation |

• Oral presentation • Clinical outcomes • Chart review • Formal evaluation (peer, supervisor, administration) |

• Clinical outcomes • Chart review • Formal evaluation (peer, supervisor, administration) |

| Analyze and evaluate effectiveness of wearable | |||

| Learning objective* applied to wearable type | • Analyze and evaluate the effectiveness of wearable type on patient outcomes |

• Analyze and evaluate the effectiveness of wearable type on patient outcomes • Evaluate impact use of wearable in practice |

• Analyze and evaluate the effectiveness of wearable type on patient outcomes • Evaluate impact use of wearable in practice • Publish experience or clinical outcomes from wearable type and its impact on practice • Create new wearable hardware or software to fill a gap in patient care |

| Teaching style | Applied learning with peers (e.g., “flipped” classroom; supervision, faculty; observing faculty, group observation, or co-interviewing) | Professional self-evaluation and supervision | Professional self-evaluation and supervision |

| Competency domain(s) |

• Patient care • Systems-based practice • Practice-based learning |

• Patient care • Systems-based practice • Interpersonal and communication skill • Professionalism |

• Patient care • Systems-based practice • Interpersonal and communication skill • Professionalism |

| Assessment methods | • Oral presentation |

• Clinical outcomes • Chart review • Formal evaluation (peer, supervisor, administration) |

-Clinical outcomes -Informal evaluation (peer-to-peer, student, administration) |

| Evaluate the impact of wearable on outcomes | |||

| Learning objective* applied to wearable type | Evaluate impact of wearable type based on patient feedback | • Evaluate impact of wearable type on patient outcomes across patients |

• Evaluate impact of wearable type on patient outcomes in research • Evaluate impact of self-created new wearable type on patient experience and outcomes |

| Teaching style | Applied learning with peers (e.g., “flipped” classroom; supervision, faculty; observing faculty, group observation, or co-interviewing) | Quality improvement, evaluation, and research | Quality improvement, evaluation, and research |

| Competency domain(s) |

• Patient care • Systems-based practice • Practice-based learning |

• Patient care • System-based practice • Practice-based learning |

• Patient care • System-based practice • Practice-based learning |

| Assessment methods | -Oral presentation |

• Clinical outcomes • Chart review • Formal evaluation (administration) |

• Clinical outcomes • Chart review • Formal evaluation (administration) |

| Teaching effectiveness | |||

| Learning objective* applied to wearable type | • Evaluate student or supervisee learning of wearable type | • Evaluate student or supervisee ability to communicate benefits and barriers of use of wearable type to others | • Evaluate student or supervisee ability to teach use of wearable type to others |

| Teaching style | Applied learning with peers (e.g., “flipped” classroom; supervision, faculty; observing faculty, group observation, or co-interviewing) | Teaching evaluation (e.g., student and peer feedback) | Teaching evaluation (e.g., student and peer feedback) |

| Competency domain(s) |

• Medical knowledge • Practice-based learning • Interpersonal and communication skills |

• Medical knowledge • System-based practice • Professionalism • Interpersonal and communication skills |

• Medical knowledge • System-based practice • Professionalism • Interpersonal and communication skills |

| Assessment methods | • Oral presentation |

• Written tests class average • Formal evaluation |

• Written tests class average • Formal evaluation |

*Learning objective based on Bloom’s taxonomy

Institutional Competencies

The original telepsychiatric competencies suggested that institutions develop an approach for video and other technologies on the e-health (or e-behavioral health) spectrum (Hilty et al. 2015). The IT-business model (Hilty et al. 2019; Hilty et al. 2019; Ray et al. 2007) provides six steps for institutions to implement new technologies: (1) assess readiness; (2) create/hardwire the culture; (3) write policies and procedures; (4) establish the curriculum and competencies; (5) train learners and faculty; and (6) evaluate/manage change. One literature review focused on additional suggestions for synchronous and asynchronous telehealth (Hilty et al. 2020) and organized institutional competencies into 5 focus areas: patient-centered care; evaluation and outcomes; roles/needs of participants (e.g., trainees, faculty, teams, professions); teams, professions and systems within institutions; and the academic health center institutional structure, process, and administration.

Discussion

A variety of sensors and wearables are being used today and they are creating new options for patient care, clinician decision-making, and population health. These options reduce geographical, cost, and temporal barriers (Naslund et al. 2016; Tachakra et al. 2003; Cowan et al 2019) and provide an opportunity to bring patients and clinical teams together for communication, support, and intervention (Kumari et al. 2017; Torous and Roberts 2017). Successful integration of these technologies into care requires a person- and patient-centered approach, with patients moving from mere passengers to valued, responsible drivers of their care. Clinicians also must be aware of required skills, knowledge, and training to assure ethical and competent practice.

Our review of established guidelines and position statements highlights several important questions and concerns. Professional organizations have prioritized and made suggestions on how to integrate video, phones and e-mail, but mobile health (e.g., apps, texts) and wearable sensors are underrepresented or not mentioned at all. Nor are boards, agencies, and other government sectors showing significant movement on mobile health technologies that correspond with current and emerging paradigm shifts.