We fully agree with Marisa Dolhnikoff and colleagues that we should aim to understand COVID-19 pathophysiology. However, their arguments directed at our Correspondence,1 which should support their Case Report2 on ultrastructural identification of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in patient tissue, are not convincing. As in other fields of ultrastructural research, identification of subcellular structures is made on the basis of ultrastructural features, which are characteristic for each structure. The putative virus particles in the publication by Dolhnikoff and colleagues2 lack essential and distinct ultrastructural features, such as biomembranes and surface structures, for an unambiguous identification of SARS-CoV-2. Their electron micrographs suggest poor structural preservation (eg, biomembranes are not detectable), for an unknown reason. Hence, the identification of enveloped viruses is very difficult and most likely impossible. We acknowledge the application of complementary techniques for viral detection, but their RT-PCR indicated a low viral load and immunohistochemistry was not directed to viral components.2

Detection of SARS-CoV-2 by electron microscopy might be impossible if there is an insufficient concentration of viral particles, which is further complicated in cases of focal infections. Thus, it cannot be generally expected to find many and evenly distributed locations in RT-PCR-positive samples, which show a significant number of viral particles. The localisation of hot spots of virus particle assembly in tissue might be guided by immunohistochemistry or in-situ hybridisation.3, 4 Identification of SARS-CoV-2 at the ultrastructural level requires characteristic morphological features (figure ). Autolysis and necrosis might negatively affect these features1 but even in suboptimal samples, including formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissue, coronavirus particle identification is possible if the characteristic ultrastructure is preserved.3, 4 Generally, coronavirus particle profiles should show the characteristic size (∼60–160 nm without spikes), shape (round to oval), biomembrane (at least partly visible), granular or dense interior space, and surface projections (at least partly visible), whereas additional features such as grouped or regular localisation within membrane compartments or in the extracellular space might help to identify SARS-CoV-2.

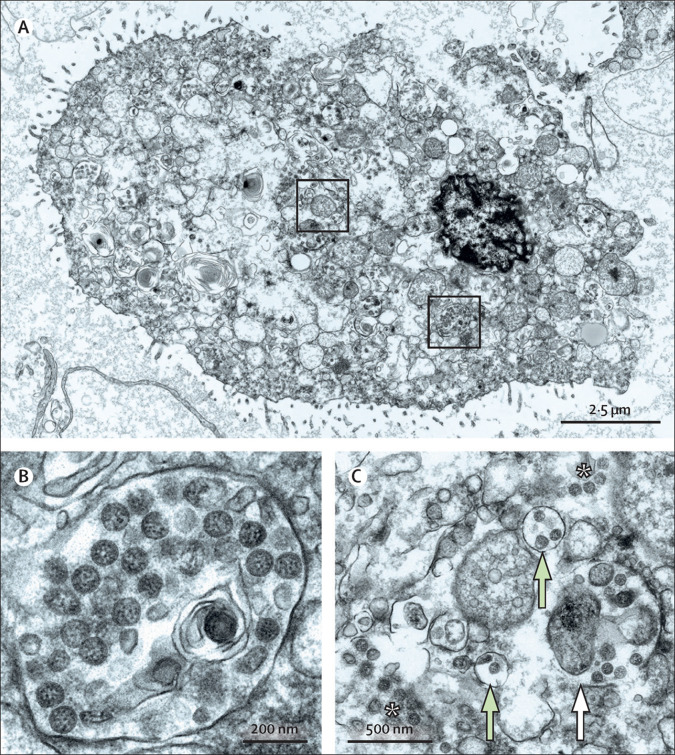

Figure.

SARS-CoV-2 ultrastructural morphology in autolytic autopsy lung

In lung autopsy tissue showing marked autolysis, we found single cells with numerous well preserved SARS-CoV-2 particles. (A) The ultrastructure of the cell is severely affected and does not clearly identify the cell type. Boxed regions are magnified in panels B and C, in which many of the round and oval particles show characteristic morphological features of SARS-CoV-2. (C) The white asterisks show well preserved viral particles that appeared free within the cytoplasm, probably due to rupture of membrane compartments. The white arrow points to well preserved viral particles within ruptured membrane compartments, and the green arrows point to viral particles within intact membrane compartments. These images were acquired with a scanning electron microscope in transmission mode. A high-resolution dataset of the cell (A, C), digitised at 1 nm pixel size, is available online for open access pan-and-zoom analysis, also allowing for measurements of structures of interest to provide a positive control of coronavirus identification in autopsy tissue. SARS-CoV-2=severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

At least 30 publications, many also peer-reviewed, showed putative coronavirus, which lacked either sufficient image quality or ultrastructural features for clear identification as SARS-CoV-2. We only discussed two in our Correspondence1 as examples to precisely address our concerns. The extent of misinterpretations or insufficiently founded interpretations of putative coronavirus particles was recently shown in a detailed review.5 Similarly, we believe that electron micrographs that were published during the SARS pandemic in the early 2000s require further discussion.

We agree with Dolhnikoff and colleagues that some concerns could be directly addressed to the authors. However, disputable publications spread very quickly, which can flaw the basis for a precise ultrastructural characterisation of SARS-CoV-2; thus, we are convinced that this crucial discussion required publication.

Acknowledgments

We declare no competing interests. We thank the Core Facility for Electron Microscopy of the Charité for support in acquisition of the data.

References

- 1.Dittmayer C, Meinhardt J, Radbruch H, et al. Why misinterpretation of electron micrographs in SARS-CoV-2-infected tissue goes viral. Lancet. 2020;396:e64–e65. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32079-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dolhnikoff M, Ferreira Ferranti J, de Almeida Monteiro RA, et al. SARS-CoV-2 in cardiac tissue of a child with COVID-19-related multisystem inflammatory syndrome. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020;4:790–794. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30257-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meinhardt J, Radke J, Dittmayer C, et al. Olfactory transmucosal SARS-CoV-2 invasion as a port of central nervous system entry in individuals with COVID-19. Nat Neurosci. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41593-020-00758-5. published online Nov 30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shieh WJ, Hsiao CH, Paddock CD, et al. Immunohistochemical, in situ hybridization, and ultrastructural localization of SARS-associated coronavirus in lung of a fatal case of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Taiwan. Hum Pathol. 2005;36:303–309. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2004.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hopfer H, Herzig MC, Gosert R, et al. Hunting coronavirus by transmission electron microscopy—a guide to SARS-CoV-2-associated ultrastructural pathology in COVID-19 tissues. Histopathology. 2020 doi: 10.1111/his.14264. published online Sept 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]