Abstract

Background

Phosphatidylethanolamine-binding proteins (PEBPs) constitute a common gene family found among animals, plants and microbes. Plant PEBP proteins play an important role in regulating flowering time, plant architecture as well as seed dormancy. Though PEBP family genes have been well studied in Arabidopsis and other model species, less is known about these genes in perennial trees.

Results

To understand the evolution of PEBP genes and their functional roles in flowering control, we identified 56 PEBP members belonging to three gene clades (MFT-like, FT-like, and TFL1-like) and five lineages (FT, BFT, CEN, TFL1, and MFT) across nine Rosaceae perennial species. Structural analysis revealed highly conserved gene structure and protein motifs among Rosaceae PEBP proteins. Codon usage analysis showed slightly biased codon usage across five gene lineages. With selection pressure analysis, we detected strong purifying selection constraining divergence within most lineages, while positive selection driving the divergence of FT-like and TFL1-like genes from the MFT-like gene clade. Spatial and temporal expression analyses revealed the essential role of FT in regulating floral bud breaking and blooming in P. mume. By employing a weighted gene co-expression network approach, we inferred a putative FT regulatory module required for dormancy release and blooming in P. mume.

Conclusions

We have characterized the PEBP family genes in nine Rosaceae species and examined their phylogeny, genomic syntenic relationship, duplication pattern, and expression profiles during flowering process. These results revealed the evolutionary history of PEBP genes and their functions in regulating floral bud development and blooming among Rosaceae tree species.

Keywords: PEBP gene family, Rosaceae species, Flowering time regulation in perennials, Gene family evolution, Floral bud break

Background

Proper timing of flowering is a key adaptive strategy in plant species, especially temperate woody perennials [1–3]. The flowering time in annual or biennials is largely determined by the timing of the transition from vegetative growth to reproductive growth [4, 5]. However, in temperate tree species, flower buds initiate and develop during summer, undergo a short period of dormancy, exit dormancy after exposure to chilling temperatures and finally bloom in suitable environments [6]. Therefore, the blooming time of temperate woody perennials is mainly determined by intrinsic state of flower buds and external environment [7, 8]. Within the context of global climate change, warm winters and irregular occurrences of extreme weather have disrupted the timing of spring phenological events in tree species, increased the risk of frost damage, and caused abnormal fertility and poor fruit setting due to insufficient winter chill [9–12]. Therefore, it is important to study the flowering time control in perennial species and understand their adaptation mechanisms in synchronizing the timing of floral bud breaking and reproduction with local climate [10, 13, 14].

Phosphatidylethanolamine-binding proteins (PEBPs) form a superfamily of genes containing a PEBP domain, which is highly conserved across taxa, from bacteria and insects to mammals and plants [15–17]. Mammalian PEBPs are globular proteins composed of a functional binding site for acetate, phosphate groups and phosphorylethanolamine [18, 19]. Plant PEBP homologs share similar conserved motifs, except their C-terminal part is deleted [20, 21]. Animal PEBP proteins were reported to function as serine proteases or Raf kinase inhibitors, controlling cell growth and differentiation [22–25]. In plants, PEBP genes are central regulators in determining the flowering time, plant architecture and seed germination [26–30]. In angiosperms, members of the PEBP family fall into three clades of genes: FLOWERING LOCUS T (FT), TERMINAL FLOWER 1 (TFL1) and MOTHER OF FT AND TFL1 (MFT) [31, 32]. It was reported that MFT-like genes exist in both basal land plants and seed plants, while FT-like and TFL1-like genes were only found in gymnosperms and angiosperms, indicating that the MFT clade might be the evolutionary ancestor to FT-like and TFL1-like genes [32, 33]. Despite extensive sequence similarity among PEBP members, their functions have diverged from each other [34].

FT and TFL1 are two major PEBP proteins that are well studied in Arabidopsis and in many other plant species [35–38]. In Arabidopsis, FT acts as a floral signal transducer, moving from leaves to the shoot apical meristem to promote flowering, while TFL1 maintains inflorescence meristem identity in shoot apex by antagonizing FT functions [39–41]. The balance of FT and TFL1 modulates floral transition and inflorescence architecture by affecting determinacy of meristem identity [30, 42]. FT and TFL1 share ∼ 60% of their amino acid sequence identity, but only a few amino acid changes can convert FT from a floral promoter to a TFL1-like floral repressor [37, 43]. In addition to FT and TFL1, the Arabidopsis PEBP gene family includes MOTHER OF FT AND TFL1 (MFT), TWIN SISTER OF FT (TSF), BROTHER OF FT AND TFL1 (BFT), and CENTRORADIALIS (CEN) [27]. MFT integrates abscisic acid (ABA) and gibberellic acid (GA) signaling pathways and acts in a PIF1-dependent manner to repress seed germination under far-red light [28, 44]. TSF encodes the closest homolog of FT and resembles FT as a floral inducer under non-inductive SD conditions [45]. BFT and CEN are two floral repressors in Arabidopsis, and the overexpression of either one resulted in a late flowering phenotype similar to plants overexpressing TFL1 [46–48].

Although the PEBP gene family has been recognized as key floral regulators in model species, their molecular evolution and function remains less clear in woody perennials. The Rosaceae family consists of over 2500 species from approximately 90 genera, most of which are native to temperate zones around the world [49–51]. Prunus is a large genus belonging to the tribe Amygdaleae and contains about 430 species, many of which are important fruit crops, such as plums, cherries, apricots and peaches [52]. Additionally, Prunus includes a large number of spring-blooming trees with high ornamental and economic value. Prunus mume is one of the earliest flowering species, which blooms in late winter or early spring, followed by apricots, peaches, cherries and plums that flower during March to April. Apple and pear trees from the tribe Maleae bloom much later, around April to May in Northern China [53]. With the divergent flowering times among Rosaceae tree species, it is of great interest to investigate the evolution of PEBP family genes and their functional roles in governing flowering time among Rosaceae tree species.

Here, we provide a systematic study on the molecular evolution and function of the PEBP gene family in Rosaceae tree species. We identified 56 PEBP family genes across nine Rosaceae species and analyzed the sequence conservation, protein motifs, gene structures, and codon usage patterns of these genes. We then performed genome synteny and duplication analysis, along with nonsynonymous/synonymous substitution (dN/dS) ratio tests, to determine the evolutionary trajectory of PEBP family genes. We also analyzed the spatial and temporal expression patterns of PEBPs across tissues and in floral buds from floral initiation to bud blooming. Furthermore, we performed weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) to determine the FT coexpressed genes in P. mume. In summary, our study provides insight into the molecular evolution of PEBP genes among Rosaceae tree species and adds information regarding their function in regulating floral bud development and blooming in woody perennials.

Results

Characterization of PEBP genes in Rosaceae species

By combining HMM and BLAST searches, we identified 56 PEBP-like proteins across nine Rosaceae tree species (Table 1). Each putative gene was validated by blasting against SMART, Pfam and NCBI CDD to ensure that they contained complete PEBP domain. We then assigned all Rosaceae PEBPs to their closest Arabidopsis homologs (Fig. 1; Table 1). In total, these Rosaceae PEBPs included 12 FT/TSF-like, 11 TFL1-like, 11 CEN-like, 10 MFT-like and 12 BFT-like genes (Table 1). TFL1 and CEN-like proteins showed the highest identities of 72.25–80.0% with their Arabidopsis orthologs, while BFT-like proteins showed the lowest identities of 62.07 to 67.82% compared with AtBFT. Five to six PEBPs were detected among Prunus species, while the average number of PEBPs almost doubled in M. domestica and Pyrus communis (Table 1). The duplicated paralogous gene pairs, such as MdTFL1 and MdTFL2, PcTFL1 and PcTFL2, were retained in the genomes of M. domestica and Pyrus communis, while only one copy of MFT was present in both species (Table 1).

Table 1.

Detailed information of PEBP genes from A. thaliana and nine Rosaceae species

| Gene lineage | Species | Gene accession number | NCBI accession | Notation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FT | Arabidopsis thaliana | AT1G65480.1; AT4G20370.1 | AtFT; AtTSF | |

| Malus domestica | MD12G1262000 | NM_001293862.1 | MdFT | |

| Pyrus communis | PCP004421.1; PCP023373.1 | PcFT1; PcFT2 | ||

| Rubus occidentalis | Ro04_G00016; Ro06_G09261 | RoFT1; RoFT2 | ||

| Prunus persica | Prupe.6G364900.1 | XM_007205940.2 | PpFT | |

| Prunus mume | Pm003733 | NM_001293253.1 | PmFT | |

| Prunus armeniaca | PARG03266m01 | PaFT | ||

| Prunus yedoensis | PQQ05805.1; PQQ09349.1 | PyFT1; PyFT2 | ||

| Prunus avium | CpS0077204G3m0 | XM_021948448.1 | PvFT | |

| Prunus dulcis | Prudul26A015211P1 | XM_034364192.1 | PdFT | |

| TFL1 | Arabidopsis thaliana | AT5G03840.1 | AtTFL1 | |

| Malus domestica | MD14G1021100; MD12G1023900 | NM_001293865.1; NM_001293958.1 | MdTFL1; MdTFL2 | |

| Pyrus communis | PCP003730.1; PCP025869.1 | PcTFL1; PcTFL2 | ||

| Rubus occidentalis | Ro06_G14897 | RoTFL | ||

| Prunus persica | Prupe.7G112600.1 | XM_007202602.2 | PpTFL | |

| Prunus mume | Pm026188 | XM_008243028.1 | PmTFL | |

| Prunus armeniaca | PARG26714m01 | PaTFL | ||

| Prunus yedoensis | PQP96161.1 | PyTFL | ||

| Prunus avium | CpS0034G256m0 | XM_021954469.1 | PvTFL | |

| Prunus dulcis | Prudul26A021958P1 | XM_034369048.1 | PdTFL | |

| CEN | Arabidopsis thaliana | AT2G27550.1 | AtCEN | |

| Malus domestica | MD11G1163500; MD03G1143000 | NM_001294011.1; NM_001293884.1 | MdCEN1; MdCEN2 | |

| Pyrus communis | PCP019918.1; PCP022206.1 | PcCEN1; PcCEN2 | ||

| Rubus occidentalis | Ro03_G20412 | RoCEN | ||

| Prunus persica | Prupe.6G128400.1 | XM_007205944.2 | PpCEN | |

| Prunus mume | Pm001309 | XM_008230265.2 | PmCEN | |

| Prunus armeniaca | PARG01261m01 | PaCEN | ||

| Prunus yedoensis | PQQ12971.1 | PyCEN | ||

| Prunus avium | CpS00116G158m0 | XM_021966077.1 | PvCEN | |

| Prunus dulcis | Prudul26A027558P1 | XM_034364411.1 | PdCEN | |

| MFT | Arabidopsis thaliana | AT1G18100.1 | AtMFT | |

| Malus domestica | MD06G1229900 | XM_008376608.2 | MdMFT | |

| Pyrus communis | PCP033759.1 | PcMFT | ||

| Rubus occidentalis | Ro05_G03590 | RoMFT | ||

| Prunus persica | Prupe.5G230900.1 | XM_007209625.2 | PpMFT | |

| Prunus mume | Pm025099 | XM_008241952.1 | PmMFT | |

| Prunus armeniaca | PARG25179m01 | PaMFT | ||

| Prunus yedoensis | PQQ05244.1; PQQ15508.1 | PyMFT1; PyMFT2 | ||

| Prunus avium | CpS0021G127m0 | XM_021947485.1 | PvMFT | |

| Prunus dulcis | Prudul26A015523P1 | XM_034360958.1 | PdMFT | |

| BFT | Arabidopsis thaliana | AT5G62040.1 | AtBFT | |

| Malus domestica | MD01G1198400; MD07G1265900 | NM_001293841.1; XM_008378317.3 | MdBFT1; MdBFT2 | |

| Pyrus communis | PCP030682.1; PCP007692.1 | PcBFT1; PcBFT2 | ||

| Rubus occidentalis | Ro07_G09463 | RoBFT | ||

| Prunus persica | Prupe.2G291900.1 | XM_007221111.2 | PpBFT | |

| Prunus mume | Pm019359 | XM_008236052.2 | PmBFT | |

| Prunus armeniaca | PARG19444m01 | PaBFT | ||

| Prunus yedoensis | PQQ01551.1; PQM34355.1 | PyBFT1; PyBFT2 | ||

| Prunus avium | CpS0033G388m0 | XM_021971342.1 | PvBFT | |

| Prunus dulcis | Prudul26A027512P1 | XM_034348832.1 | PdBFT |

Rosaceae species include M. domestica, Pyrus communis, R. occidentalis, P. persica, P. mume, P. armeniaca, P. yedoensis, P. avium and P. dulcis. Gene notations were assigned to Rosaceae PEBPs based on their Arabidopsis ortholog

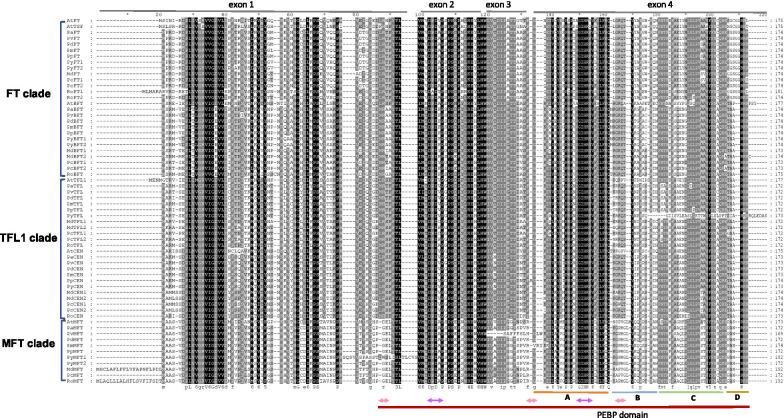

Fig. 1.

Sequence alignment of 62 PEBP family proteins from nine Rosaceae species and A. thaliana. The sequences were aligned using Muscle. The conserved protein motif 14-3-3 interaction interface and anion-binding site are underlined in pink and purple, respectively [29]. A, B, C, and D represent four segments in exon 4 [35], which are underlined in orange, blue, green and brown

Phylogenetic analyses

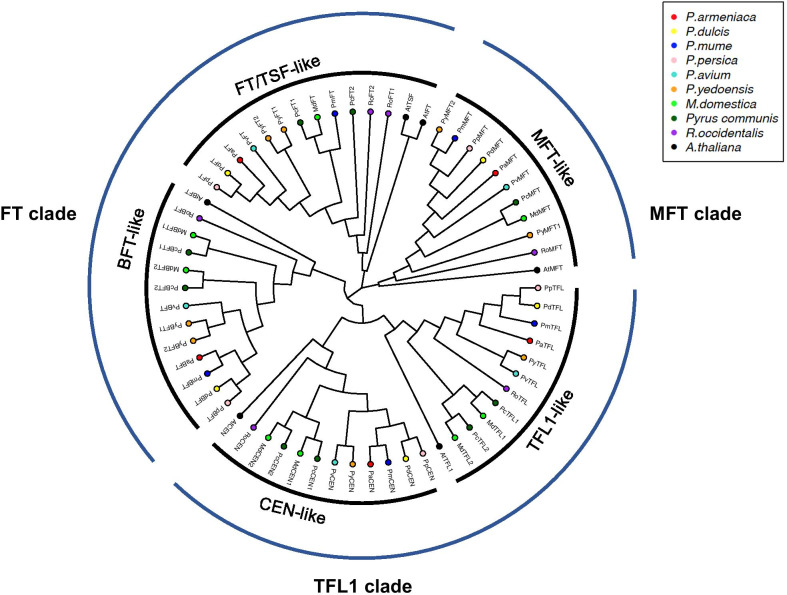

Phylogenetic trees were constructed based on protein sequence alignment of Arabidopsis and Rosaceae PEBPs using three approaches: the neighbor-joining, maximum likelihood, and Bayesian inference methods (Fig. 2; Additional file 1: Fig. S1). All three phylogenetic trees shared similar topologies (Fig. 2; Additional file 1: Fig. S1). The phylogenetic trees showed that the 62 PEBP proteins can be clustered into three major clades, which are the FT-clade, TFL1-clade, and MFT-clade (Fig. 2). The FT-clade could be further split into FT/TSF-like genes and BFT-like genes, and the TFL1-clade can be split into TFL1-like and CEN-like subfamily genes (Fig. 2). Within each subfamily, the genes of Prunus species first group closely together, then group with the genes of Maleae species including M. domestica and Pyrus communis, and finally group with genes of R. occidentalis and Arabidopsis (Fig. 2). Among Prunus PEBPs, proteins within the same subgenus tend to group together, for example, P. dulcis and P. persica from the Amygdalus subgenus, P. armeniaca and P. mume from the Prunus subgenus, and proteins of P. yedoensis and P. avium from the Cerasus subgenus (Fig. 2). The duplicated paralogous gene pairs from M. domestica and Pyrus communis within the TFL1, CEN, and BFT subfamilies were grouped separately, for example, PcTFL1-MdTFL1 and PcTFL2-MdTFL2 form separate clusters, rather than genes of the same species grouping together (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic tree of PEBPs from Rosaceae species and A. thaliana constructed by the neighbor-joining method. All PEBP proteins can be clustered into three clades and five subfamilies

Structural analysis of PEBP family genes

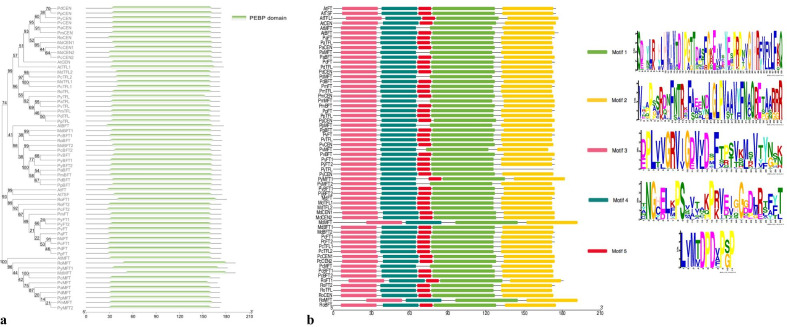

Rosaceae PEBP family genes displayed conserved gene structures and high amino acid sequence similarity (Fig. 3; Additional file 2: Fig. S2). The length of the coding regions of PEBPs ranged from 507 to 576 bps, with FT-like genes falling between 522 to 543 bps, MFT-like genes between 507 to 576 bps, BFT-like genes between 519 to 525 bps, TFL1-like genes between 516 to 519 bps, and CEN-like genes between 519 to 522 bps. All PEBP genes have a rather loose gene structure consisting of four exons and three introns (Additional file 2: Fig. S2). For example, BFT-like genes harbor the shortest intron total lengths, ranging from 522 to 534 bp (Additional file 2: Fig. S2).

Fig. 3.

Sequence conservation of the PEBP protein domains within 62 PEBP genes. a Phylogenetic analysis of sequences within the PEBP domain; b Five major motifs were predicted with MEME and visualized with TBtools

Sequence alignment revealed a high degree of conservation across the entire protein and within the PEBP domains present in all 65 genes (Figs. 1, 3). The phylogeny structure inferred from the alignment of PEBP domains was generally in accordance with that of the whole protein sequence alignment, suggesting the PEBP domain as the major factor driving the evolution of Rosaceae PEBPs (Fig. 3a). Five motifs covering 160 amino acids were identified by the MEME program among Rosaceae PEBP proteins (Fig. 3b). Among these, Motifs 1, 2, 4, and 5 together spread over the whole PEBP domain (Fig. 3b). Motifs DPDXP (Asp-Pro-Asp-X-Pro) and GIHR (Gly-Ile-His-Arg), which are essential for anion-binding activity, were present in the fourth exon of the PEBPs (Fig. 1). We also found that residues distinguishing FT-like from TFL1-like proteins were conserved among the two gene lineages (Additional file 3: Fig. S3). Previously reported key residues conferring the flowering-promoting role of FT including V76, Y91, E115, L134, Y140, G144, W145, Q147, and N159 were present in all Rosaceae FT-like proteins (Additional file 3: Fig. S3) [20, 43, 54]. The corresponding residues (I/T)76, H91, E115, (K/N/T)134, (F/N)140, (P/S)144, S145, D147, and D159 were found in all TFL1-like proteins (Additional file 3: Fig. S3). Residues determining the 14-3-3 receptor binding interface (R68, F107, R137) were shared by both protein types (Additional file 3: Fig. S3).

Microsynteny and duplication analysis of PEBP genes

To understand the evolution origin of PEBP family genes, we performed inter- and intra-genomic synteny analysis with MCScanX for Arabidopsis and seven Rosacea species with chromosome-level genome assemblies. We observed large interspecies collinear blocks between four Prunus species, P. avium, P. persica, P. armeniaca, and P. mume, which indicates high level of macrosynteny among Prunus species (Additional file 4: Fig. S4). The genome comparisons between R. occidentalis and M. domestica and between M. domestica and P. avium revealed large-scale chromosomal rearrangements including translocation and fusion-fission events that possibly occurred during the genome evolution of Rubus, Malus, and Prunus genera (Additional file 4: Fig. S4). Based on intra-genomic comparisons, we classified the duplication origin of orthologous gene pairs for Arabidopsis and other Rosacea species (Additional file 11: Table S1). Among all duplication types, whole-genome duplication (WGD)/segmental duplication was the major type for M. domestica, tandem duplicated genes were mostly found in A. thaliana, P. armeniaca, and P. persica, and dispersed duplication events were enriched in the genomes of R. occidentalis, P. mume, P. avium, and P. dulcis (Additional file 12: Table S1).

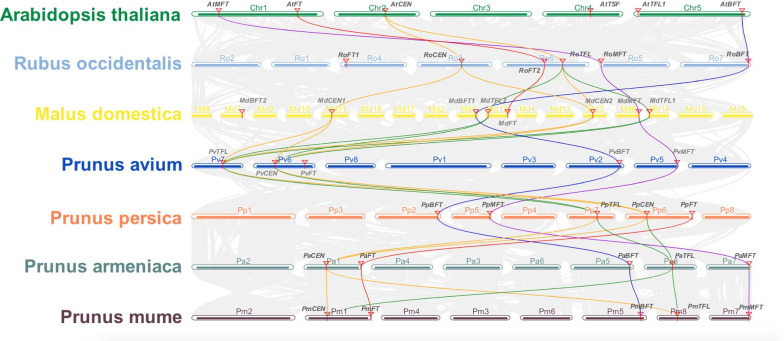

Furthermore, we characterized the duplication modes of PEBP family genes across species (Additional file 12: Table S2; Fig. 4; Additional file 5: Fig. S5). In Arabidopsis, R. occidentalis, and P. armeniaca, all PEBP gene members were predicted to be originated from dispersed duplications (Additional file 5: Fig. S5; Additional file 12: Table S2). In four Prunus species, FTs, MFTs, and BFTs were classified as having dispersed duplication, while TFL1-like and CEN-like genes were classified as exhibiting WGD/segmental duplication (Additional file 5: Fig. S5; Additional file 12: Table S2). The inter-genomic comparison of Prunus species confirmed that TFL1 and CEN genes were within shared syntenic blocks between species, indicating a shared duplication origin of TFL1-like and CEN-like genes in Prunus species (Fig. 4). Within the genome of M. domestica, we detected seven syntenic blocks consisting of three WGD/segmental duplication gene pairs, including MdTFL1-MdTFL2, MdCEN1-MdCEN2, and MdBFT1-MdBFT2, and two dispersed duplication events related to MdFT and MdMFT (Additional file 5: Fig. S5; Additional file 12: Table S2). The inter-genomic comparisons between M. domestica and R. occidental and between M. domestica and P. avium also confirmed that the duplicated gene pairs MdCEN1-MdCEN2, MdTFL1-MdTFL2, and MdBFT1-MdBFT2 are likely resulted from an independent WGD event unique to the Malus tribe (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Inter-genomic synteny blocks related to PEBP family genes in A. thaliana, R. occidentalis, M. domestica, P. avium, P. persica, P. armeniaca and P. mume. Chromosomes of Rosaceae species are labeled as Ro, Md, Pv, Pp, Pa, and Pm and are colored differently. We used purple, red, orange, green, and blue lines to connect collinear blocks containing MFTs, FTs, CENs, TFL1s, and BFTs, respectively

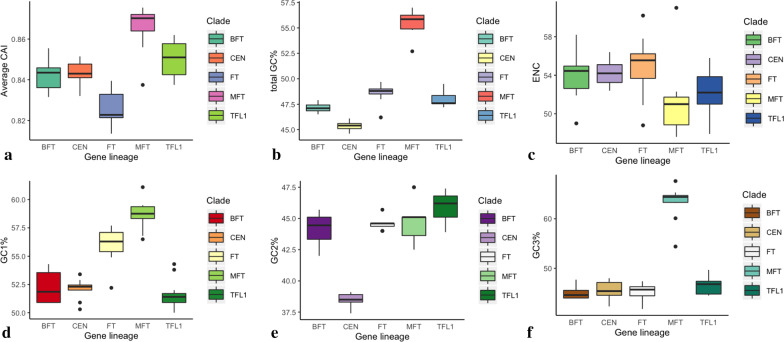

Codon usage bias and other gene parameters

We observed differentially preferred codons and different gene features across five Rosaceae PEBP gene lineages (Fig. 5; Additional file 6: Fig. S6; Table 2). For arginine, codons AGA and AGG were most frequently used by all lineages compared with other codons (Additional file 6: Fig. S6). Codon UCC encoding serine was mostly used in CEN-like and MFT-like proteins, while codon UCU was mostly employed by the FT and TFL1 lineages (Additional file 6: Fig. S6). We also observed significant differences in other gene parameters among different PEBP lineages (all Kruskal–Wallis tests pval < 0.01) (Fig. 5; Table 2). The codon adaptive index (CAI) of MFT and TFL1 genes is significantly larger than those of the other gene groups (Kruskal–Wallis test pval = 2.75e−7) (Fig. 5; Table 2). In contrast, the effective number of codons (ENC) estimated for MFT and TFL1 genes is much lower than those of the other groups (Kruskal–Wallis test pval = 0.005) (Fig. 5; Table 2). The average ENC values ranging from 51.24 to 54.95 indicated weak codon bias among PEBP genes. Analysis of the GC content revealed that MFT lineage genes had much higher GC content indices compared to other genes (Fig. 5; Table 2). In contrast, TFL1 and BFT lineage genes appear to have lower GC1% and GC3% but relatively higher GC2% compared to other groups (Fig. 5; Table 2). All gene parameters showed no variation among species (Additional file 7: Fig. S7; Kruskal–Wallis test pval > 0.05). Strong pairwise correlations between gene parameters were observed (Additional file 13: Table S3). For example, the CAI was positively correlated with the total GC% and GC3% (both correlation coefficient r ≥ 0.56), but was negatively correlated with the ENC (r = − 0.62) (Additional file 13: Table S3). On the other hand, the ENC displayed a negative correlation with the total GC content and GC3% (Additional file 13: Table S3).

Fig. 5.

Comparison of gene parameters including the a CAI, b total GC%, c ENC, d GC1%, e GC2%, and f GC3% estimated for BFT, CEN, FT, MFT, and TFL1 genes

Table 2.

Average gene parameters estimated for FT, TFL1, CEN, BFT, and MFT gene lineages

| Name | Length | CAI | Total GC% | GC1% | GC2% | GC3% | ENC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BFT | 524.500 | 0.842 | 47.142 | 52.158 | 44.133 | 45.142 | 54.133 |

| CEN | 523.364 | 0.843 | 45.327 | 52.118 | 38.427 | 45.491 | 54.264 |

| FT | 526.750 | 0.826 | 48.583 | 56.058 | 44.533 | 45.108 | 54.950 |

| MFT | 533.700 | 0.866 | 55.500 | 58.660 | 44.600 | 63.240 | 51.240 |

| TFL1 | 519.273 | 0.851 | 47.982 | 51.627 | 45.891 | 46.427 | 52.291 |

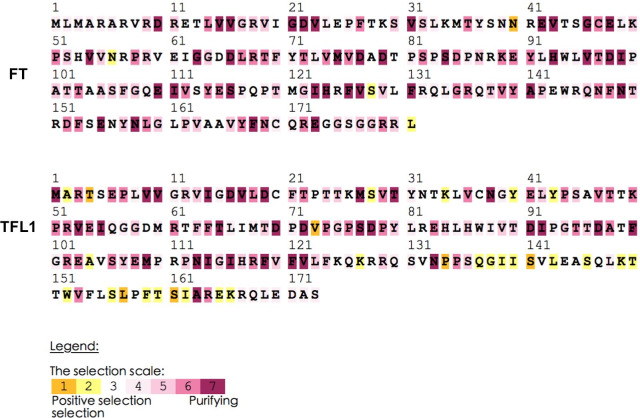

Molecular evolution of different PEBPs lineages

To investigate the evolution of PEBP genes in Rosaceae species, we performed selection scans on coding sequences of all PEBPs using the branch model, site model, and branch site model in the CODEML program of PAML (Table 3; Additional file 14: Table S4; Additional file 15: Table S5). Branch models with different ω parameters specified for foreground lineages (i.e., FT-like, TFL1-like, CEN-like, and BFT-like lineages and FT/TFL1 clades) were compared with the fixed ratio model (Additional file 14: Table S4). The likelihood ratio tests (LRT) on models specifying individual lineages of FT, TFL1, CEN, and BFT genes as the foreground branch showed no significant difference in ω between the foreground and background branch (P > 0.05) (Additional file 14: Table S4). However, the LRT test on the branch model specifying the FT and TFL1 clades as the foreground branch suggested significant divergence among FT/TFL1 and MFT clade genes (P < 0.001) (Additional file 14: Table S4). We then applied the site model LRT test and detected signs of positive selection among sites of PEBP proteins (Additional file 15: Table S5). The branch-site LRT tests further revealed strong positive selection within TFL1 lineage and slight positive selection within FT lineages at specific protein sites (Table 3). The Empirical Bayes model suggested modest selection at positions 19 and 106 when FT lineage was set as the foreground branch and at positions 11 and 18 when TFL1 lineage was set as the foreground branch (Table 3). We further validated the results by performing selective pressure analysis on five gene lineages separately with the software Selecton. Only the FT and TFL1 lineages showed the signature of positive selection, in which residues 40N, 56N, 128S, and 181L in the FT lineage (with RoFT1 as the reference gene) and 4T, 73V, 134P, 141S, 157L, and 161S in the TFL1 lineage (with PyTFL as the reference gene) were mostly selected (Fig. 6). In contrast, the genes of the other three lineages all showed signs of purifying selection across most sites (Additional file 8: Fig. S8).

Table 3.

Parameter estimates and likelihood values for branch-site models among sites and lineages of PEBP

| Branch-site model | Foreground branch | Estimate of parameters | Model comparison | 2*|lnL1 − lnL2| | df | pLRT | Selected sites |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model A | FT | proportion P = 0.54412, 0.44507, 0.00595, 0.00486 |

Model A vs Model Aa |

3.816 | 1 | 0.05 | 19,106 |

| background ω = 0.13622, 1.00000, 0.13622, 1.00000 | |||||||

| foreground ω1 = 0.13622, 1.00000, 26.81509, 26.81509 | |||||||

| TFL1 | proportion P = 0.16400, 0.49980, 0.08306, 0.25314 |

Model A vs Model Aa |

10.381 | 1 | 0.0013** | 11,18 | |

| background ω = 0.14566, 1.00000, 0.14566, 1.00000 | |||||||

| foreground ω = 0.14566, 1.00000, 999.00000, 999.00000 | |||||||

| CEN | proportion P = 0.23775, 0.76225, 0.00000, 0.00000 |

Model A vs Model Aa |

2E-06 | 1 | P > 0.05 | – | |

| background ω = 0.14634, 1.00000, 0.14634, 1.00000 | |||||||

| foreground ω = 0.14634, 1.00000, 1.00000, 1.00000 | |||||||

| BFT | proportion P = 0.20425, 0.66599, 0.03046, 0.09930 |

Model A vs Model Aa |

2.878 | 1 | P > 0.05 | – | |

| background ω = 0.12885, 1.00000, 0.12885, 1.00000 | |||||||

| foreground ω = 0.12885, 1.00000, 7.38132, 7.38132 | |||||||

| (FT, TFL1, CEN, BFT) | proportion P = 0.23291, 0.72041, 0.01140, 0.03528 |

Model A vs Model Aa |

0.521 | 1 | P > 0.05 | – | |

| background ω = 0.15263, 1.00000, 0.15263, 1.00000 | |||||||

| foreground ω = 0.15263, 1.00000, 10.76576, 10.76576 |

Significant chi-squared comparisons are indicated with * (pLRT < 0.05), ** (pLRT < 0.01), and *** (pLRT < 0.001). Positively selected sites in the foreground lineages were detected by Bayes Empirical Bayes analysis with a probability ≥ 0.7

Fig. 6.

Selective pressure analysis of FT and TFL1 lineage genes identified positively selected sites. Amino acids colored with yellow/purple indicate sites of positive/purifying selection, respectively

Cis-acting element analysis of the FT promoter

We extracted the 2000 bp region of FT genes and scanned for putative cis-elements by searching against the PlanPan and the PlantCARE databases (Table 4). We compared the type and copy number of cis-elements for 11 FT genes from A. thaliana, P. trichocarpa, M. domestica, Pyrus communis, R. occidentalis, P. armeniaca, P. avium, P. mume, and P. persica (Table 4). Within the promoter region of the investigated FTs, three to ten CCACA boxes (binding site for CO) were identified across nine species, while none were found for PtFT2 (Table 4). CArG boxes, the binding site for the MADS-box transcription factor, were present in all FT promoters, among which the AtFT promoter contained the most (Table 4). Light-response elements including the G-box, AE-box, GATA-motif, GT1-motif, and TCT-motif were present within all FT genes but in different types (Table 4). In addition, binding sites for MYB, MYC transcription factor, ethylene-responsive transcription factor, and abscisic-acid responsive element (ABRE) were present in all FT promoters (Table 4). Gibberellin-responsive elements of different types were detected in FT promoters, with GARE-motif in the promoters of MdFT, PcFT1, RoFT1, PvFT and P-box in the promoters of AtFT, PtFT2, PaFT, PvFT, PmFT, and PpFT. We also observed some cis-elements with species-specific distribution patterns. For example, the low-temperature responsiveness (LTR) element was only detected within the promoters of AtFT, PcFT1, RoFT1, PvFT and PmFT (Table 4). The W-box, which is the binding site for WRKY transcription factor, was detected exclusively in RoFTs, PtFT2, and Prunus FT promoter regions (Table 4).

Table 4.

Summary statistics of putative cis-elements present in the 2 kb upstream promoter region of FTs across nine species

| TF Family | Organism | Motif | Description | A. thaliana | Populus trichocarpa | M. domestica | Pyrus communis | R. occidentalis | P. armeniaca | P. avium | P. mume | P. persica | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AtFT | PtFT1 | PtFT2 | MdFT | PcFT1 | RoFT1 | RoFT2 | PaFT | PvFT | PmFT | PpFT | ||||

| CCACA box | A. thaliana | CCACA | Binding site for CO | 5 | 4 | 0 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 10 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| CArG box | A. thaliana | CC[A/T]6GG | Binding site for MADS-domain transcription factor | 10 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 5 |

| MYB | A. thaliana | CAACAG | Binding site for MYB transcription factor | 5 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| bHLH | A. thaliana | ATGTG/AGGTG | Binding site for MYC | 7 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 16 | 8 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 4 |

| TCT-motif | A. thaliana | TCTTAC | Part of a light-responsive element | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| GATA-motif | A. thaliana | AAGATAAGATT | Part of a light-responsive element | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| AE-box | A. thaliana | AGAAACAA | Part of a module for light response | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| G-box | A. thaliana | TACGTG | Cis-acting regulatory element involved in light responsiveness | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 2 |

| GT1-motif | A. thaliana | GGTTAA | Light-responsive element | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| MSA-like | (T/C)C(T/C)AACGG(T/C)(T/C)A | Cis-regulatory element involved in cell cycle regulation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| GARE-motif | Brassica oleracea | TCTGTTG | Gibberellin-responsive element | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| P-box | Oryza sativa | CCTTTTG | Gibberellin-responsive element | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| AP2; ERF | A. thaliana | CCGAC | Ethylene-responsive transcription factor | 7 | 3 | 5 | 8 | 6 | 8 | 6 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| ABRE | A. thaliana | ACGTG | Cis-acting element involved in the abscisic acid responsiveness | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| LTR | Hordeum vulgare | CCGAAA | Cis-acting element involved in low-temperature responsiveness | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| W box | A. thaliana | CCGAAA | Binding site for WRKY transcription factor | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

The organism column indicates in which organism the motif was characterized

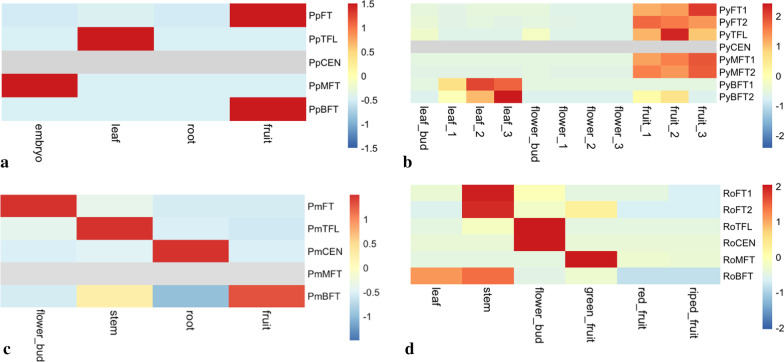

Tissue-specific expression patterns of PEBPs

To explore the functional roles of PEBP genes, we examined their expression patterns in different tissues of four Rosaceae species, P. persica, P. mume, P. yedoensis, and R. occidentalis (Fig. 7a–d). In general, we observed a differentiated expression preference of PEBP genes across different tissues (Fig. 7). Among the five PEBP subfamilies, FT-like and TFL1-like genes were expressed in both vegetative tissues such as leaf and stem, and reproductive organs such as flower bud and fruit (Fig. 7). The transcription of CENs, as the closest paralogs of TFL1, was barely detected in any organs, except in the root tissues of P. mume (Fig. 7). MFT was only detected in seed embryos of P. persica and fruit tissues of P. yedoensis and R. occidentalis (Fig. 7). BFT was detected in the fruit tissues of all species but was relatively highly expressed in leaf and stem tissues in P. yedoensis and R. occidentals, respectively (Fig. 7). We validated the tissue-specific expressions of five PEBP genes by real-time quantitative PCR (qRT-PCR) in P. mume (Additional file 9: Fig. S9). PmFT is highly expressed in floral buds compared with its expression in leaf and stem, which is consistent with result of the above tissue transcriptome sequencing in P. mume (Fig. 7; Additional file 9: Fig. S9). PmTFL and PmCEN were relatively highly expressed in root tissues (Additional file 9: Fig. S9). PmBFT and PmMFT was barely detected in the four examined tissue types (Additional file 9: Fig. S9). The somewhat inconsistent tissue-specific expression patterns of PEBP orthologs across examined species are likely a result of non-uniformity in the sampling time, plant physiological state, and tissue specificity across four independent studies. Despite the inconsistency, the divergent expression of PEBP members across different tissue types indicates significant functional differentiation of PEBP gene lineages.

Fig. 7.

Tissue-specific expression of PEBP genes in four Rosaceae species including a P. persica, b P. yedoensis, c P. mume and d Rubus occidentalis

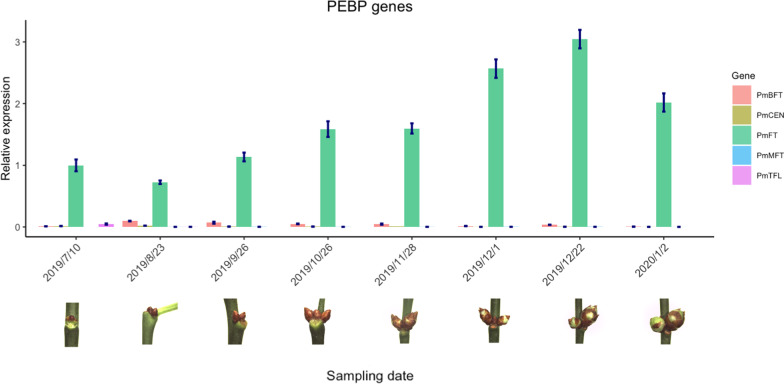

Expression analysis of PEBP genes during floral bud development in P. mume

We analyzed the expression of PEBP genes in flower buds of different developmental stages from July 10th, 2019 to January 12th, 2020 by qRT-PCR analysis. The expression of PmFT first decreased as the bud initiated the floral meristem from July to August, increased as floral organ initiated and developed (from August to October), slightly decreased during bud dormancy, and then significant increased as the floral bud exited dormancy and bloomed (Fig. 8). PmBFT maintained a low expression level throughout the whole process, with only a minor increase during floral bud development in August and September (Fig. 8). The other PEBP members retained barely detected expression levels in floral buds of all developmental stages (Fig. 8). These results imply that PmFT is possibly the primary PEBP member participating in regulating floral bud development and bud flushing in P. mume.

Fig. 8.

Relative expression levels of PEBP genes during floral bud development and bud blooming in P. mume

Co-expression network analysis of FT during the blooming process in P. mume

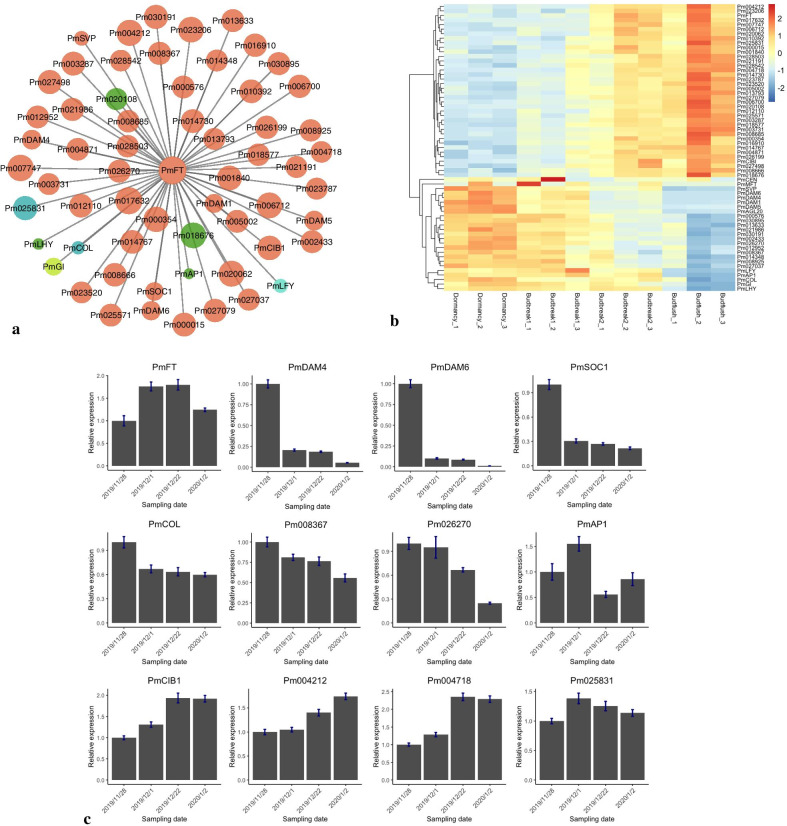

To explore the regulatory network of FT in flowering regulation in trees, we reanalyzed the transcriptome changes of P. mume during dormancy release and the floral bud opening process [55] and performed a weighted co-expression network analysis (WGCNA). We identified 23 modules with distinct expression patterns (Additional file 10: Fig. S10a). Module-trait association analysis revealed four modules, ‘brown’, 'turquoise', ‘dark green’, and ‘salmon’, associated with the progression of bud flushing (R2 > 0.8). Among them, module ‘brown’ showed the strongest correlation with the FPKM of PmFT (Additional file 10: Fig. S10b). The ‘brown’ module genes were significantly enriched in biological processes including cell cycle (GO: 0007049), flower development (GO: 0009908), glucan metabolic process (GO: 0009251), auxin transport (GO: 0060918), and responses to abiotic stimulus (GO: 0009628). We further identified the top 50 genes most associated with PmFT and 15 known flowering-related genes such as PmLFY, PmAP1, and PmCOL (Additional file 16: Table S6) [56, 57]. Among genes in the ‘brown’ module, SVP (SHORT VEGETATIVE PHASE), SOC1 (SUPPRESSOR OF OVEREXPRESSION OF CO 1), GI (GIGANTEA), and CIB1 (CRYPTOCHROME-INTERACTING BASIC-HELIX-LOOP-HELIX 1) were previously identified as key players in the FT-dependent floral regulation in Arabidopsis [58, 59] (Fig. 9a). Four tandem-duplicated PmDAMs (PmDAM1, PmDAM4, PmDAM5, PmDAM6) from the ‘brown’ module also exhibited expression patterns negatively correlated with that of PmFT (Fig. 9a, b). The expression patterns of other known floral regulators such as COL (CONSTANS-LIKE) from the ‘turquoise’, LHY1 (LATE ELONGATED HYPOCOTYL 1) and AP1 (APETALA1) from ‘dark green’ module were not highly correlated with PmFT (R2 < 0.62) (Fig. 9b). PmFT showed a relatively weak transcription level in endodormant floral buds (Fig. 9b). As the floral bud continued accumulating chilling units and exiting dormancy, PmFT expression significantly increased and showed the highest expression in flushing buds (Fig. 9b). PmCIB1 and 37 other genes showed similar expression patterns to that of PmFT, while PmPHYB (Pm008367), PmGI, PmLHY, PmCOL, PmSVP, PmSOC1, and four PmDAMs displayed contrasting expression patterns, with their expression decreasing as the floral buds exited endodormancy (Fig. 9b). The expression patterns of FT and its coexpressed genes were further verified by qRT-PCR analysis (Fig. 9c).

Fig. 9.

Co-expression network of FT during floral bud blooming in P. mume. a Cytoscape visualization of candidate genes co-expressed with PmFT during dormancy release. Candidate genes from the ‘brown’, ‘dark green, ‘green-yellow, ‘turquoise’, and ‘cyan’ modules are colored in brown, green, green-yellow, turquoise, and cyan, respectively. The circle size represents the significance of gene expression correlation with PmFT. b Expression patterns of PmFT and putative co-expressed genes during floral bud blooming. c Relative expression of PmFT and putative co-expressed genes verified by qRT-PCR analysis

Discussion

Evolution trajectory of PEBP family genes in Rosaceae genomes

PEBPs form an ancient gene family central to many plant developmental processes, including floral transition, plant architecture, and seed germination [30, 32, 60]. In Arabidopsis, the PEBP family constitutes six genes grouped into three distinct clades, FT-like (FT and TSF), TFL1-like (TFL1 and CEN), and MFT-like genes [31]. Though previous studies have characterized the functions of PEBP family genes in model plants, none have focused on a comparative analysis of the PEBP family in tree species. Our study conducted a systematic search across nine Rosaceae genomes and identified 56 PEBP family genes orthologous to six Arabidopsis genes, FT/TSF, TFL1, CEN, BFT, and MFT. The number of PEBP family members in Prunus species (chromosome 2n = 2x = 16) was approximately the same as that in Arabidopsis (five to six copies), while PEBP members were expanded in M. domestica and Pyrus communis (chromosome 2n = 2x = 34). Genome synteny and duplication analyses together supported that duplicated ortholog pairs MdTFL1-MdTFL2, MdCEN1-MdCEN2, and MdBFT1-MdBFT2 are likely originated from a recent whole-genome duplication (WGD) event that occurred in the Maleae clade after splitting from Prunus [61]. However, only one copy of MdFT, MdMFT, and PcMFT was retained in apples and pears, indicating that the duplicated copy may have been lost during species evolution after the WGD [62]. The duplication mode analysis also suggested a shared origin of TFL1 and CEN from segmental or WGD duplication in Prunus species (Additional file 12: Table S2). Previous studies reported that the angiosperm TFL1-like gene experienced duplication after splitting from basal angiosperms, followed by functional divergence, resulting in TFL1 and CEN gene lineages in eudicots [63]. Given the conserved sequence alignment of Prunus TFL1/CEN orthologs with other Rosaceae species, it is unlikely that Prunus TFL1/CEN arose from a recent segmental duplication or WGD unique to Prunus species. Therefore, the syntenic relationship may have been caused by the preservation of genomic segments containing TFL1, CEN, and their neighboring genes through rounds of chromosome rearrangements during Prunus species evolution. In Arabidopsis, the TSF gene, which is a homolog of FT, highly resembles FT in its coding sequence and flowering promoting role [64]. The absence of TSF in the Rosaceae genome suggests that the gene duplication of FT/TSF possibly occurred in Brassicaceae after splitting from their common ancestors [65].

The PEBP gene family experienced two ancient duplications, giving rise to three types: FT-like genes promoting flowering, TFL1-like genes repressing flowering and maintaining indeterminate state of meristems, and MFT-like genes controlling seed germination [17, 27, 32]. The phylogenetic analysis suggests that Rosaceae PEBPs can be clustered into three distinct clades (FT, TFL1, and MFT), which is consistent with other species [17, 27, 32]. The FT-like clade can be further divided into FT and BFT lineages, and the TFL1-like clade can be divided into TFL1 and CEN lineages. Based on maximum-likelihood test on branch models specifying different gene lineages (FT, TFL1, CEN, MFT, and BFT) as the foreground branch, we detected no evidence of positive selection acting on any of them. However, we observed significant selection acting on FT/TFL1 clade genes with the MFT clade specified as the background branch, which supports the theory that functional divergence of the FT/TFL1 clade occurred after splitting from the MFT clade [33]. Through likelihood ratio tests on branch-site models, we detected a few slightly selected codons within the FT lineage and a few strongly selected codons in the TFL1 lineage, which is consistent with results of Selecton analysis on individual lineages. In summary, these results indicate that adaptive evolution is driving the divergence of the FT and TFL1 clades from the MFT clade, as well as the diversification among FTs and TFL1s in Rosaceae species. These result are consistent with a previous study reporting that positive selection on FT-like genes especially within the fourth exon is driving their divergence from MFT and TFL1 clade [17]. We also observed strong purifying selection constraining protein evolution within the MFT, CEN, and BFT lineages in Rosaceae species. However, this does not rule out the possibility of positive selection acting on a few codons masked by strong purifying selection in preserving the other sites [17].

Additionally, we examined the codon usage patterns of PEBP genes across Rosaceae species. Codon usage bias refers to the nonrandom choice of synonymous codons in specific genes or species and can affect the translation efficiency and accuracy, protein folding, and biological functions [66, 67]. The codon usage pattern usually reflects the balanced effect of mutation pressure and selection constraints during long-term evolution [68, 69]. Several codons for amino acids were differentially preferred across five PEBP lineages. Among all codons, the most frequently used codon for arginine was AGG for FT, CEN, and MFT and AGA for the BFT and TFL1 lineages (Additional file 6: Fig. S6). Several other codons, including TCC, TCA, TCT for serine and CCT for proline, were preferred by specific PEBP gene lineages, indicating differentially selected codons by different PEBP gene lineages. To further understand the factors influencing codon usage patterns, we compared the GC content, gene length, CAI, and ENC of different PEBP lineages and species. The CAI measures the optimal codon usage for a gene and is commonly used as an index for the expression level [70]. The ENC has been widely used to determine the level of codon bias for individual genes [71]. We observed significant differences in these gene features estimated for different gene lineages but not for species. Despite the differences, all genes had a relatively high CAI (range 0.81–0.87) and moderate ENC (above 47), indicating high translational efficiency and slightly biased codon usage among PEBP genes. Furthermore, the strong pairwise correlations between ENC and GC content, ENC and CAI indicate that the nucleotide composition and gene expression level are two factors possibly contributing to the differentiated codon preference among different PEBP gene lineages [69].

Functional role of FT/TFL1 genes in Rosaceae tree species

Structural analysis of Rosaceae PEBP proteins revealed a highly conserved gene structure and amino acid sequence, especially within the PEBP functional domain (Figs. 1, 3; Additional file 2: Fig. S2). All PEBP family genes shared a common gene structure with exactly four exons of similar sizes. Among the conserved protein motifs, the anion-binding D-P-D-x-P and G-x-H-R motifs are important for the conformation of the ligand binding site in PEBP proteins [72]. Mutations close to this region may affect the binding of FT protein with phosphate ions and thus alter its interaction with FD (FLOWERING LOCUS D) [73]. Segment B on exon 4 encodes an external loop, and together with its adjacent segment C, determines the opposite functions of FT and TFL1 in Arabidopsis [35]. Another key protein motif is the 14-3-3 binding domain that is essential for FT/TFL1 interaction with 14-3-3 receptors to modulate flowering [20]. Key residues within these motifs are critical in determining FT/TFL1 functions. For example, the substitution of an amino acid (replacing His-88 in TFL1 with Tyr) can convert TFL1 into a floral promoter [37]. In another study, specific mutations at four residues—Glu-109, Trp-138, Gln-140, and Asn-152—converted FT into a TFL1-like repressor [43]. The amino acids at each of these critical positions were highly conserved and specific to FT-like and TFL1-like proteins, which suggests that the floral promoting and repressing role of FT/TFL1 genes in Rosaceae species is possibly conserved.

Recent molecular studies have characterized the function of Rosaceae FT/TFL-like genes in several Rosaceae perennials [33]. The overexpression of MdFT in both Arabidopsis and apple lead to precocious flowering [74]. The ectopic expression of PmFT and RoFT in tobacco leads to extremely advanced flowering [75]. Similarly, the late-flowering phenotype of Arabidopsis ft mutant can be rescued by overexpressing PpFT, indicating the conserved floral promoting role of FT in examined Rosaceae species [76]. On the other hand, prolonged vegetative growth and a late-flowering phenotype were observed for transgenic Arabidopsis/tobacco overexpressing PpTFL1, PmTFL1, RoTFL1, MdTFL1-1/2, suggesting that the Rosaceae TFL1-like genes can complement the TFL1 function in Arabidopsis [77–79].

Despite the conservative function of Rosaceae FT/TFL1-like genes in herbaceous plant systems, their regulatory roles in perennial trees may differ. For example, two homologs of PcFTs showed differed annual expression patterns in the apical buds of Pyrus communis [80]. The ectopic expression of PcFT2 caused early flowering in tobacco but delayed dormancy and leaf senescence in M. domestica [80]. Another study in pears reported that the expression of FTs was not induced in the reproductive meristem prior to floral initiation, while the transcripts of TFL1s rapidly decreased and maintained a very low level, indicating the essential role of TFL1 in floral induction in Pyrus pyrifolia [36]. In our study, the minimal level of TFL1 throughout all floral bud stages may indicate that the repression of TFL1 is necessary for determinate floral meristem identity and terminal flower formation during floral bud development in P. mume. The multifaceted role of FT/TFL1-like genes was also observed in other tree species [33]. In poplar, PtFT1 functions as a floral promoter activated by chilling temperatures, while vegetative growth and dormancy breaking are promoted by PtFT2 [81]. Plum trees transformed with PtFT1 displayed a shrub-like growth habit, a reduced chilling requirement, and insensitivity to short-day signals [82]. In gymnosperms, FT-like genes exhibited contrasting roles in regulating growth cycling and bud setting [83]. For example, expression of FT/TFL1-like genes in Norway spruce (PaFTL2) and Scots pine (PsFTL2) increase during bud setting in autumn and decrease during bud bursting in the next spring [84–86]. Thus, FT/TFL1-like genes may undertake some novel functions concerning floral transition, plant architecture, and growth-dormancy cycling during the evolution of tree species.

Regulatory role of FT in promoting bud break and blooming in perennial trees

Flowering is a major developmental process that is key to the fitness and reproduction of higher plants [87]. Plants have synchronized their seasonal timing of flowering with favorable environmental conditions to ensure sexual reproduction success and seed production [87, 88]. The regulation of flowering times requires an intricate network of signaling pathways, which has been studied in many plant species but is best characterized in Arabidopsis [57, 87, 89]. FT functions as a gene hub integrating five major floral induction pathways, including the photoperiodic pathway, vernalization pathway, autonomous pathway, gibberellin pathway, and age pathway [56, 59]. In Arabidopsis, the transcription of FT is activated by the transcription factor CONSTANS (CO), which is affected by the circadian regulatory GI [90, 91]. The GI-CO-FT module not only is used to regulate photoperiod-dependent flowering in Arabidopsis and temperate cereals [92, 93] but also showed a conserved function in regulating short-day induced bud dormancy in poplar [94]. In addition to CO, SVP, FLC (FLOWERING LOCUS C), and PIF4 (PHYTOCHROME INTERACTING FACTOR 4) from the vernalization pathway can also regulate FT transcription through directly binding the FT promoter or intronic regions [90, 95–97]. Upon induction by long-photoperiod signals, FT, together with other floral pathway integrators SOC1 and LFY (LEAFY), activates floral meristem identity genes such as AP1, APETALA2 (AP2), FRUITFULL (FUL), CAULIFLOWER (CAL), and LFY, which convert the vegetative meristem to floral meristem in Arabidopsis [59, 98, 99].

Though flowering regulation is well understood in model species, it is still unclear in temperature tree species. Unlike annual or biennials, many trees in temperate environments initiate floral buds in the preceding summer, cease growth in autumn, with floral buds remaining dormant during winter, and then bloom early in spring after exposure to chilling temperatures [6, 10]. Therefore, perennial flowering marks the event of the floral bud exiting dormancy and flushing instead of the time of floral meristem initiation in annual species [6]. So far, many studies on floral bud breaking regulation have been reported; however, the molecular mechanism is still far from complete. Apart from regulating floral initiation, FT has been suggested to participate in regulating bud dormancy in temperate trees [100]. Poplar exhibited constitutive expression of FT1 initiated flower-like structures directly from tissue culture and showed delayed growth cessation in short-days [81, 94], while FT2 was predominantly expressed during vegetative growth and is likely responsible for growth cessation and vegetative bud set [81]. Moreover, Rinne et al. (2011) reported that FT is hyper-induced during bud breaking in poplar, indicating that FT may also participate in regulating dormancy release in poplar [101]. In pear, chilling reduces the expression of DAM genes, which are well-known floral repressors, releasing the repression of FT and promoting floral bud breaking [102, 103]. Our expression analysis confirmed that FT is significantly induced during chilling-mediated floral bud breaking in P. mume.

To further understand the regulatory module of FT during floral bud breaking, we used WGCNA and identified a number of candidate genes whose expression patterns strongly correlated with FT in P. mume. Among these candidates, PmDAM1, PmDAM4, PmDAM5, and PmDAM6 were found to be downregulated during the progression of bud breaking. Another MADS-box gene PmSVP displaying a similar expression pattern to that of PmDAMs was reported to maintain bud dormancy in apples [104]. Thus, PmDAMs and PmSVP may function as FT repressors in the same manner as in Arabidopsis by binding to the CArG box in the promoter region of PmFT [105]. A number of genes previously identified upstream FT, including PmCOL, PmGI, and PmCIB1, were found to be induced by chilling in endodormant buds before the activation of PmFT. These genes may act directly or indirectly to activate FT expression during dormancy release in P. mume. We also observed that some known FT regulated genes, namely, AP1, SOC1, and LFY, peaked before the induction of FT, indicating their functional role during flower bud development prior to bud breaking [6, 106]. Additionally, a number of FT co-expressed genes were annotated to pathways that did not show relatedness to bud breaking or flowering in previous studies. Future functional studies are required to characterize the regulatory mechanisms of FT in floral induction and bud breaking in Rosaceae tree species.

Conclusions

In this study, we systemically characterized the PEBP gene family in nine Rosaceae species and examined their gene structure, protein features, evolutionary trajectories, and expression profiles. The 56 PEBP genes can be divided into three major clades, namely, FT-like, TFL1-like, and MFT-like genes. We observed highly conserved protein motifs and gene structure among PEBP genes. Selection scans showed that positive selection is driving the divergence of the FT and TFL1 clades, while strong purifying selection is restraining diversification within most lineages. Expression analysis of PEBP genes suggested the essential role of FT in floral bud development and blooming. Furthermore, we identified a number of FT co-expressed genes, revealing a FT-related regulatory model in Prunus species different from those in annual or biennial plants. In summary, the comprehensive analysis of the PEBP family in our study provided evidence of structural and functional conservation of PEBP genes among Rosaceae woody perennials and provided insight into the adaptive evolution of the PEBP gene family over the evolutionary history of perennial trees.

Methods

Identification of the PEBP gene family

We obtained the most recent versions of genomes for P. persica [107], P. mume [108], P. yedoensis [109], P. avium [110], P. dulcis, P. armeniaca [111], M. domestica [112], Pyrus communis [113], and R. occidentalis [114] from GDR (Genome Database For Rosaceae) [115]. To identify the PEBP genes of each species, we retrieved the HMM model PF01161 of PBP domain from the Pfam database (https://pfam.xfam.org) and searched the genome protein databases with an e-value cutoff of 1.0 × e−5 using HMMER 3.1 software [116]. In addition, we used protein sequences AtFT (At1g65480.1), AtTSF (At4g20370.1), AtTFL1 (At5g03840.1), AtBFT (At5g62040.1), and AtMFT (At1g18100.1) downloaded from TAIR (The Arabidopsis Information Resource) (www.arabidopsis.org) as query sequences to blast against the local protein databases of nine species, and we only retained putative PEBP proteins with identities > 40% and e-values ≤ 1.0 × e−10. The genes identified by both methods were considered as candidate PEBP family genes and were then verified with SMART [117], Pfam [118], and the CDD database [119] to ensure the completeness of the PBP domain. Redundant sequences or sequences with incomplete PEBP domain were excluded from the following analyses.

Phylogenetic analysis

Multiple sequence alignment was performed using the protein sequences with software MUSCLE v3.8 [120] and was visualized with GeneDoc v2.6 [121]. Phylogenetic trees were constructed using neighbor-joining (NJ) method with MEGA7 [122], maximum likelihood (ML) analysis with RAxML v8.1 [123], and Bayesian inference (BI) with MrBayes 3.1 [124]. Bayesian inference was performed with 100,000 generations of Markov-chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) simulations, discarding the first 2500 trees as ‘burn-in’. With consistent tree topologies inferred by these three approaches, the neighbor-joining tree was chosen to display the phylogeny of Rosaceae full PEBP protein sequences. Furthermore, amino acids within the regions of predicted PEBP domains were extracted and used to construct a PEBP domain tree by the NJ method.

Gene structure and protein motif detection

The exon and intron locations of PEBP genes were analyzed by comparing the coding sequences with their genome sequences. The MEME (Multiple Expectation Maximization for Motif) online tool (http://meme-suite.org/tools/meme) was used to predict protein motifs [125]. The protein motifs were further annotated with the Pfam [118], SMART [117] and CDD [119] online tools. The chromosome distributions of PEBP genes were obtained based on genome GFF3 files. Finally, the gene structures, protein motifs, and chromosome locations were visualized with the software TBtools [126].

Microsynteny analysis and codon usage evaluation

To identify the synteny of PEBP family genes among species, we performed all-to-all BLASTP between the genomes of A. thaliana, R. occidentalis, M. domestica, P. avium, P. persica, P. armeniaca, and P. mume. We also performed self-blast by comparing protein-coding genes against their own genome using BLASTP. All BLASTP hits with e-values < 1e−10 were used as input for software MCScanX (Multiple Collinearity Scan toolkit) [127] to identify possible collinear blocks within and between genomes of different species. Based on the self-blast results, we classified the duplication origin of orthologous genes pairs including PEBP family genes with the ‘duplicate_gene_classifier’ toolkit built in MCScanX for each species. All intra/inter-genomic synteny relationships were visualized with TBtools [126].

Gene parameters including the GC content (total GC%, GC1%, GC2%, and GC3%), CAI, and ENC were computed using CAICal (http://genomes.urv.cat/CAIcal/) [128, 129]. CAI provides an estimate of directional translational selection in optimizing the codon usage patterns of genes and is used to predict highly expressed genes [70]. ENC is a number between 20 to 61 that measures the degree of codon usage bias (where ENC = 20 refers to the preference of only one codon per amino acid, while ENC = 61 refers to complete unbiased codon usage) [130]. We compared these gene parameters for FT, TFL1, CEN, BFT, and MFT gene lineages and across species using the Kruskal Wallis Test with the ‘kruskal.test’ function in R. The relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU) is defined as the ratio of the observed codon frequency to the expected frequency of all synonymous codons per amino acid and is calculated using software MEGA7 [131].

Molecular evolution of PEBP genes

To investigate the signatures of positive selection on Rosaceae PEBP genes, we extracted the coding sequences of PEBP genes and aligned them with MUSCLE v3.8 [120]. The sequence alignment was then trimmed with Gblocks [132] in ‘codon’ mode, and the resulting alignments were used to infer phylogenetic relationships with RAxML [123]. The ratios (ω) of nonsynonymous substitution sites (dN) and synonymous substitution sites (dS) were computed for each PEBP lineage gene using the branch model, site model and branch-site model with the codeml package in PAML 4.0 [133]. To test the hypothesis of adaptive evolution in specific PEBP lineages and across sites, we performed likelihood ratio tests to evaluate the fit of branch models (FT, TFL1, CEN, BFT and (FT, TFL1, CEN, BFT) set as foreground branch), site models, and branch site models. The positively selected sites were detected by Bayes Empirical Bayes analysis in PAML 4.0 [133]. To better visualize the site-specific selection on amino acids within each PEBP lineage, we performed a selection pressure test with site model M8 and visualized the results with Selecton Server [134].

Cis-element analysis of the FT promoter region

To investigate the conservation of the cis-regulatory model of FT genes across different species, we extracted the 2 kb upstream region of the start codon (ATG) and submitted the sequences to the PlantCARE [135] and PlantPan 2.0 databases [136]. The cis-acting elements predicted by both methods were integrated and considered as putative cis-acting elements.

Tissue-specific expression profiles of PEBP genes

The tissue transcriptome sequencing data of P. mume, P. yedoensis, P. persica, and R. occidentalis was retrieved from four independent studies: GSE4760162 from the GEO database [108] and SRP136962, SRA053230, and SRP149938 from the NCBI SRA database [109, 137]. The raw SRA files were first dumped to FASTQ format using SRA toolkit and preprocessed with Trimmomatic v0.38 [138] to trim off poor-quality reads. Clean paired reads were aligned with the reference genomes of P. mume, P. yedoensis, P. persica, and R. occidentalis, respectively, with software HISAT2 [139]. The genic count was computed with HTSeq [140] and normalized to RPKM with R package ‘edgeR’ [141]. The RPKM value of each PEBP gene across different tissues of P. mume, P. persica, P. yedoensis, and R. occidentalis was extracted and visualized using the ‘pheatmap’ package in R. The relative expression of PEBP genes in leaf, stem, root, and floral bud tissues was tested in P. mume using real-time PCR analysis with detailed procedure described below.

Expression analysis of PEBP genes during the flower bud development process

To further understand the functional role of PEBP genes in floral bud initiation and the bud flushing process, we performed real-time quantitative PCR analysis to examine the temporal expression patterns of PEBP genes. Lateral floral bud samples were collected from P. mume ‘Fei Lve’ tree grown in the Jiufeng sunlight greenhouse approximately every four weeks from July 10th, 2019 to January 12th, 2020. The total RNA was extracted from mixed bud samples using the E.Z.N.A.® Plant RNA Kit following the manufacturer’s instructions (Omega Bio-tek, Norcross) and was reverse-transcribed into cDNA using the PrimeScript RT reagent kit with gDNA Eraser (Takara, Japan). We performed real-time PCR experiments with at least three technical replicates on the PikoReal real-time PCR platform (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Germany). The temperature was set as follows: 95 °C for 30 s; 40 cycles of 95 °C for 5 s, 60 °C for 30 s; 60 °C for 30 s; and ending 20 °C. We used protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) as an internal reference and calculated the relative transcription levels of target genes using the 2 − ΔΔCt method [142]. The primers used for qRT-PCR experiments are listed (Additional file 17: Table S7).

Co-expression network of FT during the blooming process in P. mume

To investigate the functional role of FT during floral bud flushing, we obtained the transcriptome data of four successive stages during dormancy release and blooming in P. mume from a previous study reported by Zhang et al. (2018) [55]. The procedure of sample collection, RNA extraction, sequencing library construction, quality control, and gene expression quantification was described in detail [55]. We normalized the gene expression and performed weighted gene co-expression network analysis with WGCNA v1.67 package in R [143]. The Dynamic Tree Cut algorithm was applied to detect gene modules (power β of 4; height cutoff of 0.3; minimal module size of 30). To identify the key modules coexpressed with FT, we calculated the module-trait association and ranked genes by their correlation with the FPKM value of PmFT. Finally, the top 50 candidate genes (R2 > 0.6) coexpressed with PmFT and 15 FT interacting factors identified in Arabidopsis flowering pathways [56, 57] were selected to construct the coexpression network of FT. The FT regulatory network was visualized with Cytoscape 3.1 [144]. The expression levels of FT and putative co-expressed genes were further validated by qRT-PCR analysis. The primers are described in the supplementary data (Additional file 18: Table S8).

Supplementary Information

Additional file1: Fig. S1. Phylogenetic trees were constructed using three different algorithms.

Additional file2: Fig. S2. Exon-intron distributions of PEBP family genes from nine Rosaceae species and A. thaliana.

Additional file 3: Fig. S3. Protein sequence alignment of FT and TFL1-like proteins in Arabidopsis and nine Rosaceae species.

Additional file4: Fig. S4. Inter-genomic synteny blocks between species.

Additional file 5: Fig. S5. Distribution and collinearity of PEBP family genes within genomes of nine Rosaceae species.

Additional file 6: Fig. S6. Heatmap of average RSCU scores estimated for different codons in five Rosaceae PEBP gene lineages.

Additional file 7: Fig. S7. Comparison of gene parameters including the (a) CAI, (b) total GC%, (c) ENC, (d) GC1%, (e) GC2%, (f) GC3% for all PEBP genes across nine Rosaceae species.

Additional file 8: Fig. S8. Selective pressure analysis of the BFT, CEN, and MFT lineages and PEBP genes as a whole identified strong purifying selection across protein sites.

Additional file 9: Fig. S9. Relative expression of PEBP family genes in floral bud, leaf, stem, and root tissues of P. mume.

Additional file 10: Fig. S10. Weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) during four stages of floral bud blooming in P. mume.

Additional file 11: TableS1. Numbers of genes originated from different types of duplication events in the genomes of Arabidopsis and seven Rosaceae species.

Additional file 12: TableS2. The duplication modes of PEBP genes in the genomes of Arabidopsis and seven Rosaceae species.

Additional file 13: TableS3. Pearson correlation between gene parameters estimated for 56 Rosaceae PEBP genes.

Additional file 14: TableS4. Parameter estimates and likelihood values for branch models among PEBP lineages.

Additional file 15: TableS5. Parameter estimates and likelihood values for site models across PEBP protein sites.

Additional file 16: TableS6. Candidate genes co-expressed with PmFTduring dormancy release in P. mume.

Additional file 17: TableS7. Primers used in qRT-PCR analysis for PEBPfamily genes in P. mume.

Additional file 18: TableS8. Primers used in qRT-PCR analysis for FTco-expressed genes in P. mume.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Jason Holliday (Virginia Tech) for his help in revising the manuscript.

Authors' contributions

MZ designed and conducted the study; PL performed the blast analysis and sequence curation; XY assisted in sample collection; JW and TC provided help with transcriptome analysis; QZ supervised the project and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, China (Grant No. BLX201828) and Special Fund for Beijing Common Construction Project.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that no competing interests exist.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12862-021-01762-4.

References

- 1.Ågren J, Oakley CG, Lundemo S, Schemske DW. Adaptive divergence in flowering time among natural populations of Arabidopsis thaliana: estimates of selection and QTL mapping. Evolution. 2017;71(3):550–564. doi: 10.1111/evo.13126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gaudinier A, Blackman BK. Evolutionary processes from the perspective of flowering time diversity. New Phytol. 2019;225(5):1883–1898. doi: 10.1111/nph.16205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Townsend T, Albani M, Wilkinson M, Coupland G, Battey N: The diversity and significance of flowering in perennials. In: Annual plant reviews volume 20: Flowering and its manipulation. 2006. p. 181–97.

- 4.Khan MRG, Ai XY, Zhang JZ. Genetic regulation of flowering time in annual and perennial plants. Wiley Interdiscip Rev. 2014;5(3):347–359. doi: 10.1002/wrna.1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huijser P, Schmid M. The control of developmental phase transitions in plants. Development. 2011;138(19):4117–4129. doi: 10.1242/dev.063511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilkie JD, Sedgley M, Olesen T. Regulation of floral initiation in horticultural trees. J Exp Bot. 2008;59(12):3215–3228. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ern188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Basler D, Korner C. Photoperiod and temperature responses of bud swelling and bud burst in four temperate forest tree species. Tree Physiol. 2014;34(4):377–388. doi: 10.1093/treephys/tpu021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rohde A, Bastien C, Boerjan W. Temperature signals contribute to the timing of photoperiodic growth cessation and bud set in poplar. Tree Physiol. 2011;31(5):472–482. doi: 10.1093/treephys/tpr038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rafferty NE, Scaven VL. Physiological effects of climate warming on flowering plants and insect pollinators and potential consequences for their interactions. Curr Zool. 2013;59(3):418–426. doi: 10.1093/czoolo/59.3.418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abbott AG, Zhebentyayeva T, Barakat A, Liu Z. Chapter six - the genetic control of bud-break in trees. In: Plomion C, Adam-Blondon A-F, editors. Advances in botanical research. Boca Raton: Academic Press; 2015. pp. 201–28. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dirlewanger E, Quero-García J, Le Dantec L, Lambert P, Ruiz D, Dondini L, Illa E, Quilot-Turion B, Audergon JM, Tartarini S, et al. Comparison of the genetic determinism of two key phenological traits, flowering and maturity dates, in three Prunus species: peach, apricot and sweet cherry. Heredity. 2012;109(5):280–292. doi: 10.1038/hdy.2012.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vitasse Y, Lenz A, Körner C. The interaction between freezing tolerance and phenology in temperate deciduous trees. Front Plant Sci. 2014;5:1–8. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ladwig LM, Chandler JL, Guiden PW, Henn JJ. Extreme winter warm event causes exceptionally early bud break for many woody species. Ecosphere. 2019;10(1):1–9. doi: 10.1002/ecs2.2542. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cattani AM, Sartor T, da Silveira Falavigna V, Porto DD, Silveira CP, Diasde Oliveira PR, Revers LF. The control of bud break and flowering time in plants. Adv Bot Res. 2018;88:277–325. doi: 10.1016/bs.abr.2018.10.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chautard H, Jacquet M, Schoentgen F, Bureaud N, Bénédetti H. Tfs1p, a member of the PEBP family, inhibits the Ira2p but not the Ira1p Ras GTPase-activating protein in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Eukaryot Cell. 2004;3(2):459–470. doi: 10.1128/EC.3.2.459-470.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yeung K, Seitz T, Li S, Janosch P, McFerran B, Kaiser C, Fee F, Katsanakis KD, Rose DW, Mischak H, et al. Suppression of Raf-1 kinase activity and MAP kinase signalling by RKIP. Nature. 1999;401(6749):173–177. doi: 10.1038/43686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zheng X-M, Wu F-Q, Zhang X, Lin Q-B, Wang J, Guo X-P, Lei C-L, Cheng Z-J, Zou C, Wan J-M. Evolution of the PEBP gene family and selective signature on FT-like clade. J Syst Evol. 2016;54(5):502–510. doi: 10.1111/jse.12199. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Serre L, Vallée B, Bureaud N, Schoentgen F, Zelwer C. Crystal structure of the phosphatidylethanolamine-binding protein from bovine brain: a novel structural class of phospholipid-binding proteins. Structure. 1998;6(10):1255–1265. doi: 10.1016/S0969-2126(98)00126-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Banfield MJ, Barker JJ, Perry ACF, Brady RL. Function from structure? The crystal structure of human phosphatidylethanolamine-binding protein suggests a role in membrane signal transduction. Structure. 1998;6(10):1245–1254. doi: 10.1016/S0969-2126(98)00125-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsuji H, Taoka K-I. Chapter five - florigen signaling. In: Machida Y, Lin C, Tamanoi F, editors. The enzymes. London: Academic Press; 2014. pp. 113–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vallee BS, Coadou G, Labbe H, Sy D, Vovelle F, Schoentgen F. Peptides corresponding to the N- and C-terminal parts of PEBP are well-structured in solution: new insights into their possible interaction with partners in vivo. J Peptide Res. 2008;61(2):47–57. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3011.2003.21039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hengst U, Albrecht H, Hess D, Monard D. The phosphatidylethanolamine-binding protein is the prototype of a novel family of serine protease inhibitors. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(1):535–540. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002524200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keller ET, Fu Z, Brennan M. The role of Raf kinase inhibitor protein (RKIP) in health and disease. Biochem Pharmacol. 2004;68(6):1049–1053. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lorenz K, Lohse MJ, Quitterer U. Protein kinase C switches the Raf kinase inhibitor from Raf-1 to GRK-2. Nature. 2003;426(6966):574–579. doi: 10.1038/nature02158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Odabaei G, Chatterjee D, Jazirehi AR, Goodglick L, Yeung K, Bonavida B. Raf-1 kinase inhibitor protein: structure, function, regulation of cell signaling, and pivotal role in apoptosis. Adv Cancer Res. 2004;91:169–200. doi: 10.1016/S0065-230X(04)91005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bradley D, Carpenter R, Copsey L, Vincent C, Rothstein S, Coen E. Control of inflorescence architecture in Antirrhinum. Nature. 1996;379(6568):791–797. doi: 10.1038/379791a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karlgren A, Gyllenstrand N, Kallman T, Sundstrom JF, Moore D, Lascoux M, Lagercrantz U. Evolution of the PEBP gene family in plants: functional diversification in seed plant evolution. Plant Physiol. 2011;156(4):1967–1977. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.176206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vaistij FE, Barros-Galvão T, Cole AF, Gilday AD, He Z, Li Y, Harvey D, Larson TR, Graham IA. MOTHER-OF-FT-AND-TFL1 represses seed germination under far-red light by modulating phytohormone responses in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115(33):8442–8447. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1806460115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mackenzie KK, Coelho LL, Lütken H, Müller R. Phylogenomic analysis of the PEBP gene family from Kalanchoë. Agronomy. 2019;9(4):171. doi: 10.3390/agronomy9040171. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jin S, Nasim Z, Susila H, Ahn JH: Evolution and functional diversification of FLOWERING LOCUS T/TERMINAL FLOWER 1 family genes in plants. Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology. 2021;109:20–30. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Hedman H, Källman T, Lagercrantz U. Early evolution of the MFT-like gene family in plants. Plant Mol Biol. 2009;70(4):359–369. doi: 10.1007/s11103-009-9478-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu Y-Y, Yang K-Z, Wei X-X, Wang X-Q. Revisiting the phosphatidylethanolamine-binding protein (PEBP) gene family reveals cryptic FLOWERING LOCUS T gene homologs in gymnosperms and sheds new light on functional evolution. New Phytol. 2016;212(3):730–744. doi: 10.1111/nph.14066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wickland Daniel P, Hanzawa Y. The FLOWERING LOCUS T/TERMINAL FLOWER 1 gene family: functional evolution and molecular mechanisms. Mol Plant. 2015;8(7):983–997. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2015.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang Z, Zhou Z, Liu Y, Liu T, Li Q, Ji Y, Li C, Fang C, Wang M, Wu M, et al. Functional evolution of phosphatidylethanolamine binding proteins in soybean and Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Online. 2015;27(2):323–336. doi: 10.1105/tpc.114.135103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ahn JH, Miller D, Winter VJ, Banfield MJ, Lee JH, Yoo SY, Henz SR, Brady RL, Weigel D. A divergent external loop confers antagonistic activity on floral regulators FT and TFL1. EMBO J. 2006;25(3):605–614. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bai S, Tuan PA, Saito T, Ito A, Ubi BE, Ban Y, Moriguchi T. Repression of TERMINAL FLOWER1 primarily mediates floral induction in pear (Pyrus pyrifolia Nakai) concomitant with change in gene expression of plant hormone-related genes and transcription factors. J Exp Bot. 2017;68(17):4899–4914. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erx296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hanzawa Y, Money T, Bradley D. A single amino acid converts a repressor to an activator of flowering. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(21):7748–7753. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500932102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Koskela EA, Sønsteby A, Flachowsky H, Heide OM, Hanke M-V, Elomaa P, Hytönen T. TERMINAL FLOWER1 is a breeding target for a novel everbearing trait and tailored flowering responses in cultivated strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa Duch.) Plant Biotechnol J. 2016;14(9):1852–1861. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baumann K, Venail J, Berbel A, Domenech MJ, Money T, Conti L, Hanzawa Y, Madueno F, Bradley D. Changing the spatial pattern of TFL1 expression reveals its key role in the shoot meristem in controlling Arabidopsis flowering architecture. J Exp Bot. 2015;66(15):4769–4780. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erv247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen Q, Payyavula RS, Chen L, Zhang J, Zhang C, Turgeon R. FLOWERING LOCUS T mRNA is synthesized in specialized companion cells in Arabidopsis and Maryland Mammoth tobacco leaf veins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115(11):2830–2835. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1719455115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Luccioni L, Krzymuski M, Sánchez-Lamas M, Karayekov E, Cerdán PD, Casal JJ. CONSTANS delays Arabidopsis flowering under short days. Plant J. 2019;97(5):923–932. doi: 10.1111/tpj.14171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee C, Kim S-J, Jin S, Susila H, Youn G, Nasim Z, Alavilli H, Chung K-S, Yoo SJ, Ahn JH. Genetic interactions reveal the antagonistic roles of FT/TSF and TFL1 in the determination of inflorescence meristem identity in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2019;99(3):452–464. doi: 10.1111/tpj.14335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ho WWH, Weigel D. Structural features determining flower-promoting activity of Arabidopsis FLOWERING LOCUS T. Plant Cell. 2014;26(2):552–564. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.115220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Footitt S, Ölçer-Footitt H, Hambidge AJ, Finch-Savage WE. A laboratory simulation of Arabidopsis seed dormancy cycling provides new insight into its regulation by clock genes and the dormancy-related genes DOG1, MFT, CIPK23 and PHYA. Plant Cell Environ. 2017;40(8):1474–1486. doi: 10.1111/pce.12940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]