Abstract

Background

Volunteers are increasingly promoted to improve health-related outcomes for community-dwelling elderly without synthesized evidence for effectiveness. This systematic review and meta-analysis evaluates the effects of unpaid volunteer interventions on health-related outcomes for such seniors.

Methods

MEDLINE, EMBASE and Cochrane (CENTRAL) were searched up to November 2018. We included English language, randomized trials. Two reviewers independently identified studies, extracted data, and assessed evidence certainty (using GRADE). Meta-analysis used random-effects models. Univariate meta-regressions investigated the relationship between volunteer intervention effects and trial participant age, percentage females, and risk of bias.

Results

28 included studies focussed on seniors with a variety of chronic conditions (e.g., dementia, diabetes) and health states (e.g., frail, palliative). Volunteers provided a range of roles (e.g., counsellors, educators and coaches). Low certainty evidence found that volunteers may improve both physical function (MD = 3.2 points on the 100-point SF-36 physical component score [PCS]; 95% CI: 1.09, 5.27) and physical activity levels (SMD = 0.5, 95% CI: 0.14 to 0.83). Adverse events were not increased.

Conclusion

Volunteers may increase physical activity levels and subjective ratings of physical function for seniors without apparent harm. These findings support the WHO call to action on evidence-based policies to align health systems in support of older adults.

Keywords: volunteers, geriatrics, community

INTRODUCTION

Increasing longevity is a main driver of population aging worldwide. This trend has major implications for the health-care sector, particularly human health resources where traditional family structures have changed dramatically with increased numbers of older people living alone and without informal caregivers.(1) The world’s population aged 60 years and older will double and total about two billion by 2050, and is expected to carry the highest burden of chronic disease, requiring increasingly complex care management across multiple sectors of primary, community, and home-based care.(2)

As community builders and cultivators of social connectedness, volunteers are needed and increasingly recruited and trained to work within the health-care system to add relational support, improve connection with social and health-care systems, and augment health professional resources and services.(3) New programs (e.g., home-based care and treatment support) emphasizing the volunteer role in the community to improve health-care integration and health outcomes for older adults are emerging;(4–7) however, this entire body of evidence has not been synthesized to date.

Previous reviews have summarized separately some aspects of volunteer impact for those living with cancer, depression, and diabetes among children and general adult populations (not specifically adults over 55 years of age).(8–10) Closer to our population of interest, a narrative subgroup analysis from a Cochrane review found that community lay health workers improved subjective well-being, happiness, physical health, and contentment, with no improvement in mortality, disability, or mental health status for the elderly(11) (although these interventions included paid lay health workers).

Based on the overarching hypothesis from the Health TAPESTRY(12) study, we proposed (aprior) that community volunteer activity, comparable to community or lay health worker activities, would improve patient-reported outcomes for older adults. To that end, we reviewed the literature in older populations to assess the impact specifically of unpaid volunteers on physical activity, self-reported mental and physical health, quality of life, falls, hospitalization, and harms (adverse events) experienced by elderly persons residing in the community. Our broad outcomes of interest (physical health and mental well-being) were not only limited to recipients of volunteer care and could include such impacts on volunteers who may themselves be older adults. It is important to acknowledge that, in addition to our outcomes of interest, there are deep and meaningful social gains (e.g., companionship, camaraderie, self-esteem) that are experienced particularly by older volunteers, as well as instrumental benefits of volunteering (e.g., skills development and employability) as experienced by younger volunteers.(13)

Aligned with the WHO strategy on aging to “maintain functional ability and well-being in older age”,(1) this paper aims to support the development of evidence-informed policy for clinical leaders, health system planners, volunteer organizations, and citizens regarding health and social system planning for the increasing populations of seniors residing in the community.

METHODS

Protocol Registration

A protocol for this review was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42019116541).

Data Sources

We searched MEDLINE, EMBASE and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) for relevant published randomized control trials (RCTs), from database inception to November 2018, without language restriction. Appendix A provides the search strategy. We also searched the reference lists of included studies and relevant reviews for additional eligible trials.

Study Selection

Reviewers screened the titles and abstracts of all identified studies, independently and in duplicate, using a priori selection criteria. Subsequently, reviewers assessed full texts for potentially eligible studies, and resolved disagreements through consensus or third-party consultation with the authorship team. We screened for inclusion, English language trials that randomized adults residing in the community aged 55 years or older to volunteer interventions or to usual/standard of care, waitlist control, or no intervention. To be included, volunteers were the primary intervention. We excluded studies where participants were hospitalized or resided in institutional settings (e.g., hospitals, long-term care, prison) or workplace settings. We also excluded studies that compensated volunteers (paid volunteer personnel) or did not report any of our outcomes of interest.

Our outcomes of interest were: subjective reports from older adults of physical health (physical function, physical activity levels), mental health (emotional function, anxiety, depression), and quality of life, as well as objective outcomes of frequency of falls, hospital admissions, and lastly, adverse events associated with volunteer interventions. Specifically, we were interested in the following outcomes, as measured by these six metrics:

Physical Health

Physical functioning as reported using the ‘physical functioning’ domains from validated tools such as: the 36-Item and 12-Item Short Form Health Surveys (SF-36, SF-12),(14) the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC),(15) and the WHO Quality of Life-BREF (WHOQOL-BREF).(16) If the ‘physical functioning’ domain was not available, the physical component summary scores of the SF-36 or SF-12 (which incorporate the domains of physical functioning and role physical) were used.(14)

Physical activity as reported using validated metrics such as: time spent in moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA)(17) (e.g., minutes of exercise per week) or the metabolic equivalent of task (MET) (e.g., energy spent in activity per kg of weight).(18)

Mental Health

Emotional functioning as reported using the ‘emotional functioning’ domain from validated tools such as the SF-36 and SF-12(14) or the WHOQOL-BREF.(16) If the ‘emotional functioning’ domain was not available, the mental component summary scores (which include emotional functioning) from the SF-36 or SF-12(14) were used.

Anxiety as reported using the anxiety subscales of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS),(19) the Mental Health Inventory (MHI),(20) or other validated tools.

Depression as reported using the depression subscales of the HADS,(19) the MHI, the Centre for Epidemiological Studies-Depression (CES-D) scale,(21) the Geriatric Depression Scale, or other validated tools were used.(22)

Quality of Life

Quality of life as reported using the EuroQol-5D (EQ-5D),(23) WHOQOL-BREF,(16) or other validated tools were used.

Falls (as reported)

Hospitalizations (as reported)

Adverse Events (as reported by study authors)

Data Extraction and Risk of Bias Assessment

Two reviewers (BS and SM) extracted the following data, independently and in duplicate: general study information (first author’s name, publication year, and trial design), participants’ details (sample size, age, number of male/female participants, participants’ health status/clinical conditions), details on the intervention and comparison (characteristics of volunteers, setting), and outcomes as listed above (Appendix B). In three- or four-arm randomized trials with two active arms, if both interventions were delivered by unpaid volunteers but with different intensity or duration, we combined outcome data using methods suggested by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions.(24) When studies reported their results in multiple follow ups, we extracted data from the longest follow-up time.

The same two reviewers independently assessed risk of bias using a modified Cochrane risk of bias instrument for RCTs that addressed the following issues: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of study participants, health-care providers, and outcome assessors, incomplete outcome data (> 20% missing participant data), and other potential sources of bias.(25,26)

Certainty of Evidence Assessment

To assess the certainty of evidence, we used the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) approach that classifies evidence as high, moderate, low, or very low certainty on the basis of considerations of risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias.(27) We resolved disagreements between reviewers in data extraction, risk of bias assessments, and assessments of evidence certainty by consensus. We used the MAGIC Authors Publishing Platform (https://app.magicapp.org) to generate the GRADE summary of findings table.

Data Synthesis and Statistical Methods

Continuous measures were converted to common scales on a domain-by-domain basis as follows:(28)

Physical functioning was converted to the 100-point SF-36 physical component score.

Emotional functioning was converted to the 100-point SF-36 mental component score.

Quality of life was converted to 0–1 point EQ-5D score.

Depression and anxiety were converted to 10-point HADS (range from 11–21).

For the above-mentioned outcomes, we calculated the mean difference (MD) and its corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI). The median of the control group of included trials was used as the baseline risk. Due to the nature of measurements for physical activity, we decided to use standardized mean difference (SMD) for pooling these results due to various reporting metrics (e.g., MET, MVPA). For frequency of falls and hospitalizations, we used narrative description to summarize these results, as quantitative pooling was not feasible due to variation in reporting (e.g., total number of individuals experiencing an event and number of falls events). For cluster randomized trials, we used the method suggested by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions to calculate effective sample size, using the intracluster correlation coefficient or variance inflation factor reported in the original trial.(24)

Statistical heterogeneity was assessed using the Q statistic and I2. We used the DerSimonian–Laird random-effects model for the meta-analysis of all outcomes.(24) We performed subgroup analysis for risk of bias on an item-by-item basis. Subgroup analyses were performed when two or more studies were in a given subgroup. We conducted tests of interaction to establish whether the subgroups differed significantly from each other.(29) We performed univariate meta-regressions to assess the effects of participant’s age and percentage of female participants on the intervention effects. We examined publication bias using funnel plots for outcomes when 10 or more studies were available.(30) We used Stata software (Version 15.1, StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA) for all statistical analysis.

RESULTS

Description of Included Studies

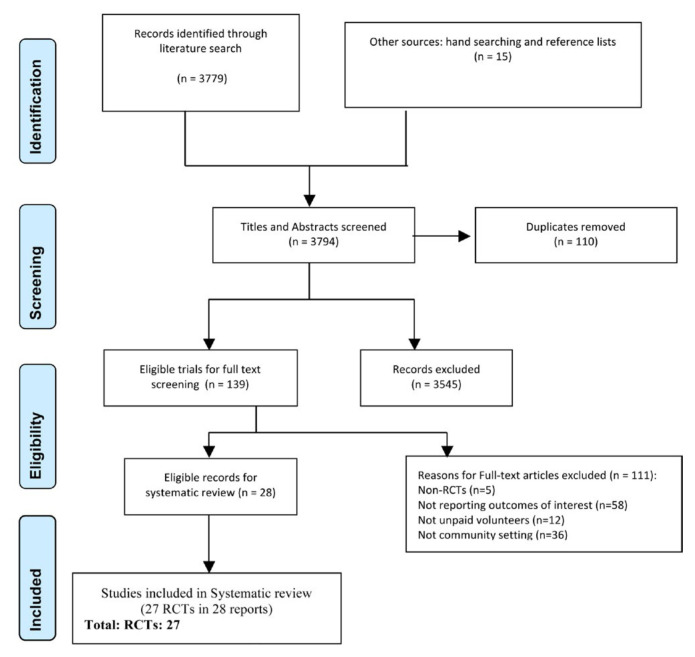

We identified 3,794 titles and abstracts from our searches, of which 139 were deemed eligible for full-text evaluation. Figure 1 provides the details of study selection. We included 27 trials in 28 reports that proved eligible, enrolling 146,937 individuals. The median age of study participants among the included studies was 66.4 years (interquartile range [IQR]: 61.4 to 76.1), on average 65.0% of trial participants were female (IQR: 52.2% to 82.7%). One study took place in a lower-middle income country (Philippines), the remainder took place in high income countries: the USA (9 studies), followed by the United Kingdom (5 studies), Canada and Austria (3 studies each), Australia and Hong Kong (2 studies each), and one study from each of Scotland, Finland, and Argentina (Table 1).

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA flow diagram for study selection

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of Studies

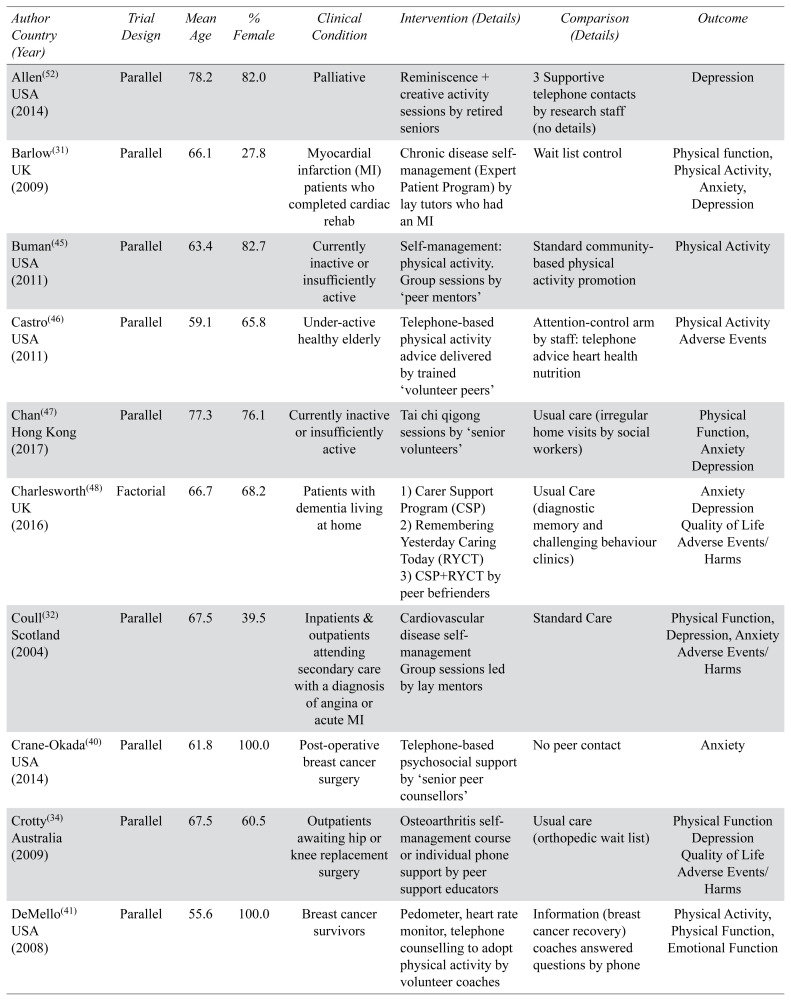

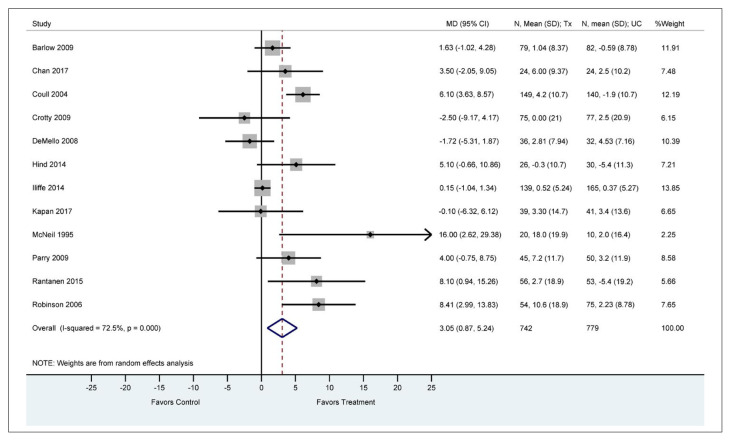

| Author Country (Year) | Trial Design | Mean Age | % Female | Clinical Condition | Intervention (Details) | Comparison (Details) | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allen(52) USA (2014) | Parallel | 78.2 | 82.0 | Palliative | Reminiscence + creative activity sessions by retired seniors | 3 Supportive telephone contacts by research staff (no details) | Depression |

| Barlow(31) UK (2009) | Parallel | 66.1 | 27.8 | Myocardial infarction (MI) patients who completed cardiac rehab | Chronic disease self-management (Expert Patient Program) by lay tutors who had an MI | Wait list control | Physical function, Physical Activity, Anxiety, Depression |

| Buman(45) USA (2011) | Parallel | 63.4 | 82.7 | Currently inactive or insufficiently active | Self-management: physical activity. Group sessions by ‘peer mentors’ | Standard community-based physical activity promotion | Physical Activity |

| Castro(46) USA (2011) | Parallel | 59.1 | 65.8 | Under-active healthy elderly | Telephone-based physical activity advice delivered by trained ‘volunteer peers’ | Attention-control arm by staff: telephone advice heart health nutrition | Physical Activity Adverse Events |

| Chan(47) Hong Kong (2017) | Parallel | 77.3 | 76.1 | Currently inactive or insufficiently active | Tai chi qigong sessions by ‘senior volunteers’ | Usual care (irregular home visits by social workers) | Physical Function, Anxiety Depression |

| Charlesworth(48) UK (2016) | Factorial | 66.7 | 68.2 | Patients with dementia living at home | 1) Carer Support Program (CSP)2) Remembering Yesterday Caring Today (RYCT) 3) CSP+RYCT by peer befrienders |

Usual Care (diagnostic memory and challenging behaviour clinics) | Anxiety Depression Quality of Life Adverse Events/Harms |

| Coull(32) Scotland (2004) | Parallel | 67.5 | 39.5 | Inpatients & outpatients attending secondary care with a diagnosis of angina or acute MI | Cardiovascular disease self-management Group sessions led by lay mentors | Standard Care | Physical Function, Depression, Anxiety Adverse Events/Harms |

| Crane-Okada(40) USA (2014) | Parallel | 61.8 | 100.0 | Post-operative breast cancer surgery | Telephone-based psychosocial support by ‘senior peer counsellors’ | No peer contact | Anxiety |

| Crotty(34) Australia (2009) | Parallel | 67.5 | 60.5 | Outpatients awaiting hip or knee replacement surgery | Osteoarthritis self-management course or individual phone support by peer support educators | Usual care (orthopedic wait list) | Physical Function Depression Quality of Life Adverse Events/Harms |

| DeMello(41) USA (2008) | Parallel | 55.6 | 100.0 | Breast cancer survivors | Pedometer, heart rate monitor, telephone counselling to adopt physical activity by volunteer coaches | Information (breast cancer recovery) coaches answered questions by phone | Physical Activity, Physical Function, Emotional Function |

| Escolar(53) Philippines (2014) | Parallel | 60.0 | Healthy elderly | Third Age Learning Program (wellness, physical fitness, and livelihood training by volunteer university faculty) | No exposure to intervention | Depression | |

| Gagliardino(37) Argentina (2013) | Parallel | 60.9 | 51.5 | Diabetic patients | Peer diabetic educators (group sessions) | Professional diabetic educators | Hospital Admissions (not pooled) |

| Haider(50) Austria (2018) | Parallel | 82.8 | 83.8 | Prefrail and frail older adults | Home based physical training, nutritional and social support by lay volunteers (buddies) | Social home visits (lay volunteers) | Physical Performance Battery (not pooled) |

| Hind(57) UK (2014) | Parallel | 80.9 | 58.6 | Independently living elderly | Individual and group phone calls to support social connection by befrienders | Usual health and social care provision | Physical Function Emotional Function Depression Quality of Life Adverse Events/Harms |

| Iliffe(54) UK (2014) | cluster | 71.9 | 63.0 | Healthy elderly | Class-based or home-based exercise program by peer mentors | Usual primary care | Physical Function Quality of Life Falls Adverse Events/Harms |

| Johansson(38) Austria (2016) | cluster | 63.0 | 51.3 | Diabetic patients | Physical activity sessions & diabetes self–management groups by peer supporters | Usual primary care practices | Quality of Life |

| Kaczorowski (58) Canada (2011) | cluster | 74.8 | 52.2 | Community dwelling residents > 65 years of age | Cardiovascular risk assessment and education sessions by peer health educators | Communities not exposed to intervention | Hospital Admissions (not pooled) |

| Kapan (51) Austria (2017) | Parallel | 82.6 | 83.8 | Prefrail or frail elderly | Home based physical training & nutritional advice by lay volunteers (buddies) | Social home visits (lay volunteers) | Physical Function Physical activity Falls Quality of Life |

| Leone(42) USA (2016) | Cluster | 62.8 | 68.6 | Older African Americans (average risk for colon cancer) | Telephone calls to motivate physical activity and adhere to colon cancer screening by Church-based peer counsellors | Comparison churches (Newsletters promoting fruit and vegetable consumption) | Physical Activity |

| McNeil(49) Canada (1995) | Parallel | 72.5 | 86.7 | Community-dwelling, unhealthy and unhappy elderly | Home visits (conversations and or walking activities (psychology student volunteers) | Wait list control | Subjective Physical Health score (1 item) Happiness scale (Not pooled) |

| Mountain(55,57) UK (2014) | Parallel | 81.0 | 58.6 | Elderly living independently | Individual and group phone calls to promote social connection by befrienders | Usual health and social care provision | Physical Function Emotional Function Quality of Life |

| Parry(33) Canada (2009) | Parallel | 63.0 | 16.8 | First-time nonemergency coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery patients | Individualized education & support via telephone by cardiac surgery peers | Usual care (‘standard’ pre and post CABG education) | Physical Function Emotional Function |

| Rantanen(35) Finland (2015) | Parallel | 81.9 | 90.1 | Elderly with severe mobility limitations (otherwise healthy) | Out of home activities (walking, cultural events, daily errands) by retired volunteers | Waitlist control | Physical Function Quality of Life Adverse Events/Harms |

| Robinson(36) USA (2006) | Parallel | 58.6 | 100.0 | Middle-aged and older women with chronic physical disabilities | Workshops health-related goal setting, social connection by peer supporters | Waitlist control | Physical Function |

| Safford(39) USA (2015) | Cluster | 60.2 | 75.3 | Diabetic patients selected for interest in self-management | One-to-one planning for diabetic primary care visits by ‘peer coaches’ | Group diabetes education class | Quality of Life |

| Thomas(56) Hong Kong (2012) | Cluster | 72.1 | 66.2 | Healthy elderly | Pedometry use plus individual and group support for physical activity motivation by ‘peer buddy’ supporters | 1) Non-pedometry 2) Non-peer support 3) Non-pedometry and non-peer support |

Physical activity |

| White(44) Australia (2012) | Parallel | 64.6 | 40.5 | Outpatients with recent (< 3 months) colorectal cancer diagnosis | Telephone support to address (pre-identified unmet health needs) by peer supporters | Usual care (patients informed of this allocation) | Proportion Depressed and Anxious (not pooled) |

| Weber(43) USA (2007) | Parallel | 60.0 | 0.0 | Prostate cancer patients 6 weeks post radical prostatectomy | One-to-one in-person discussions (thoughts, feelings, surgical side effects) by peer supporters | Usual care (provided by urologist) | Depression |

Studies focused on seniors living with a variety of conditions and health states, including: cardiovascular disease,(31–33) osteoarthritis,(34–36) diabetes,(37–39) cancer,(40–44) inactivity,(45–47) dementia,(48) depression,(49) frailty,(50,51) end of life status,(52) and healthy seniors(35,53–56) (Table 1).

Volunteers were most commonly described as ‘peers’ in various roles including: general support,(34,38,43,45,48) mentoring,(32,41,55,57) educating,(37) coaching,(39,41) advising,(45) and counseling.(40,42) Volunteers were frequently described as non-proessionally trained, lay-tutors,(31) lay health workers,(50) and general ‘volunteers’,(55,57) as well as variously described as: retired seniors,(35,52) befrienders,(48,55,57) volunteer professors,(53) students,(49) and facilitators(55,57) (Table 1). Two of the included studies reported impact on senior volunteers themselves who described value and meaning in their own engagement with older adults, relating to their ability to connect and make a contribution.(48,57)

Study interventions intended to support a range of health goals, most commonly improving physical activity levels,(35,41,42,50,51,54,56) followed by chronic disease self-management skills,(31–33,37–39) and coping with cancer,(40,41,43,44) care giving,(48) and end of life state,(52) as well as improving overall mental well-being,(36,42,49) social connectedness,(55,57) and capacity for aging at home(55,57) (Table 1).

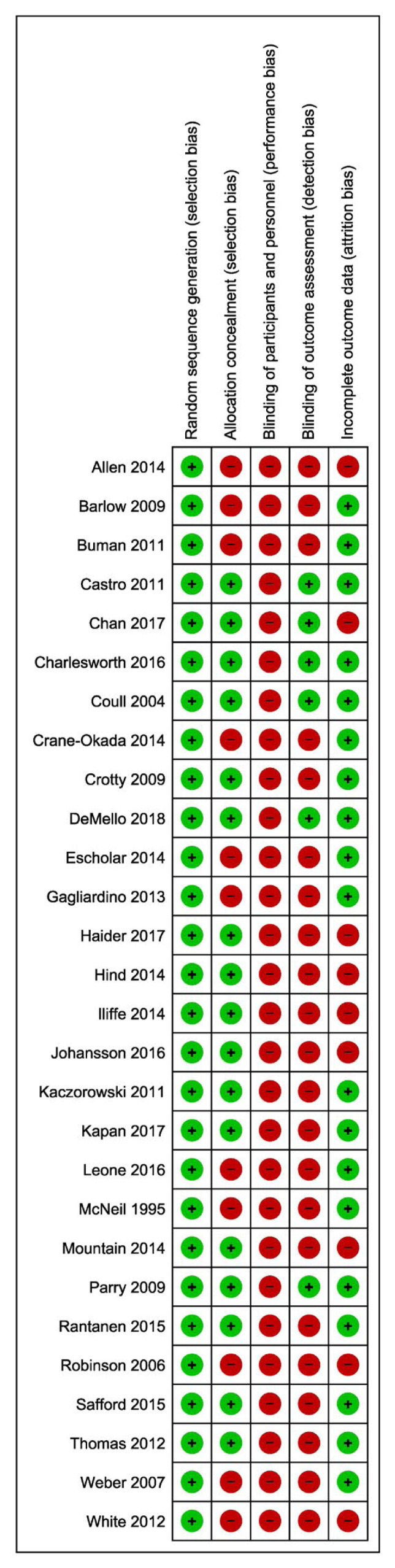

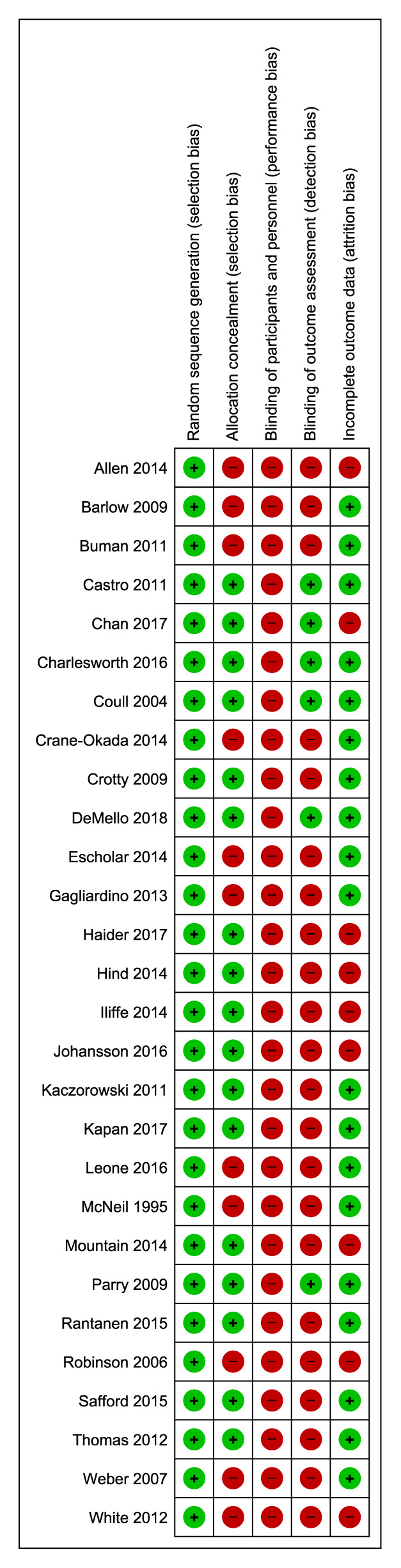

Blinding of participants is not considered feasible in this context and, therefore, the main concerns of bias were related to lack of assessor blinding affecting 22 included studies,(31,34–40,42–45,49–58) inadequate allocation concealment in 11 studies,(31,36,37,40,42–45,49,52,53) and incomplete outcome data (>20% of participants) in 9 studies(38,44,47,50,52,54–57) (Figure 2) with individual study risk of bias reported in Appendix C.

FIGURE 2.

Risk of bias-included studies

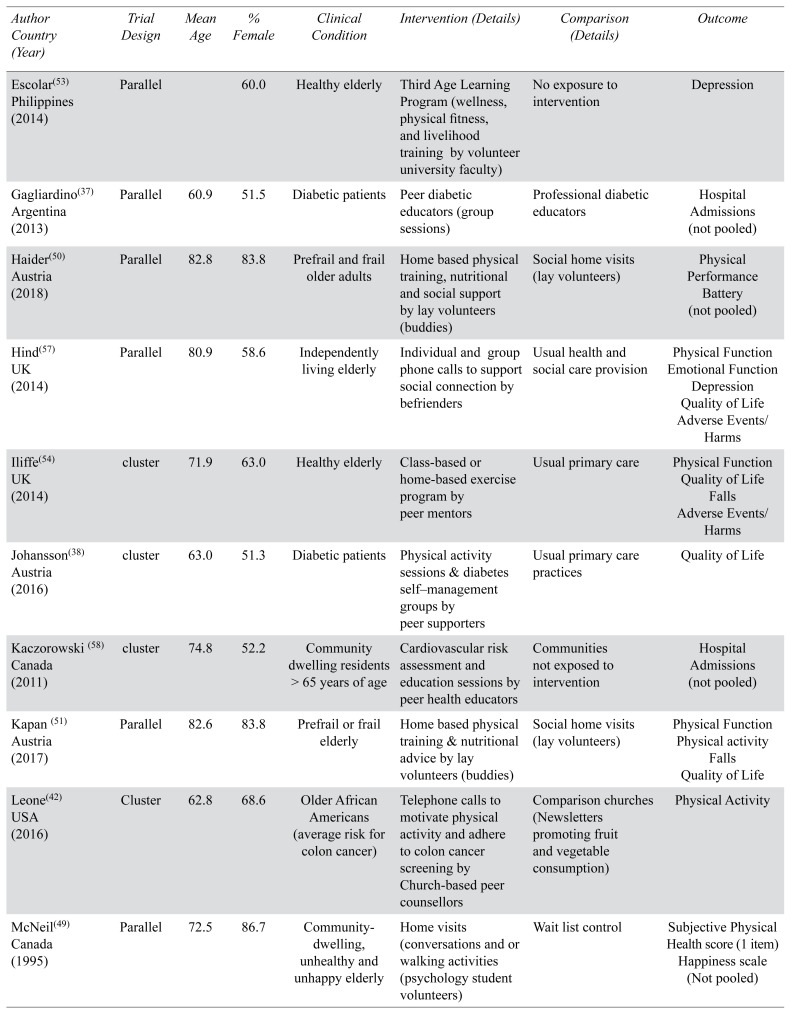

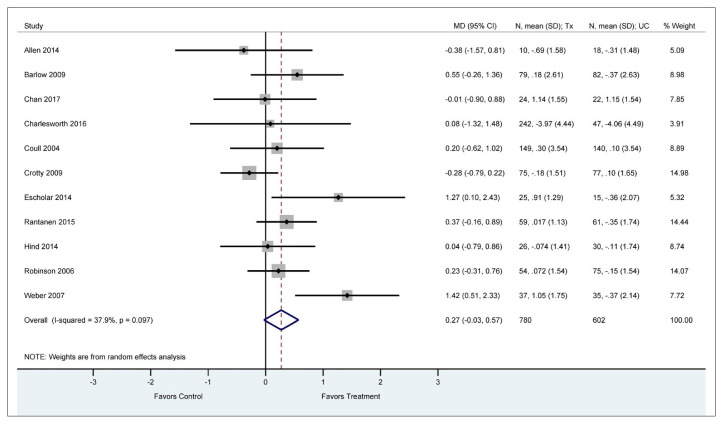

Physical Health

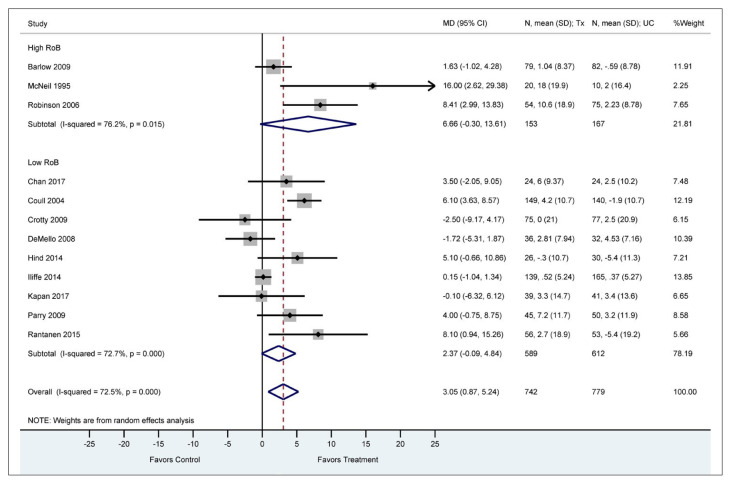

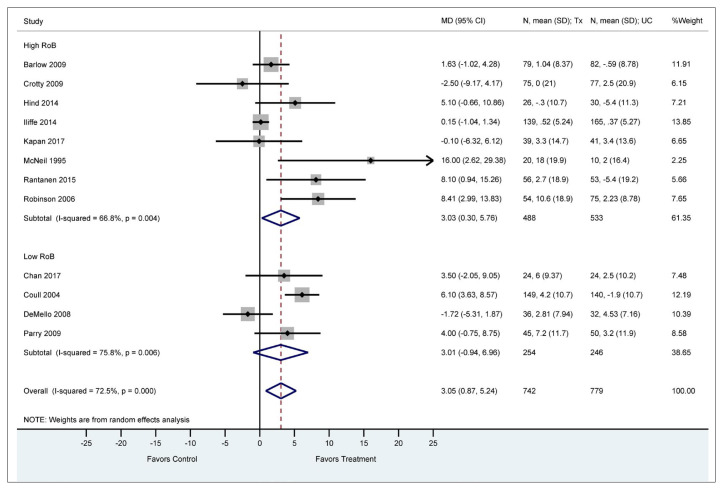

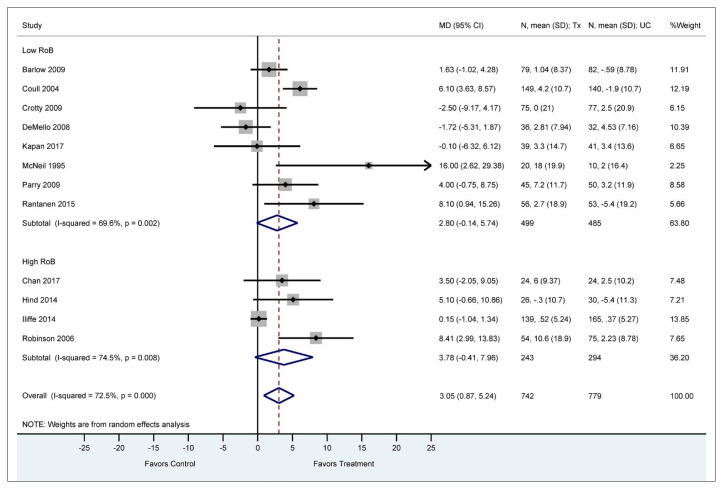

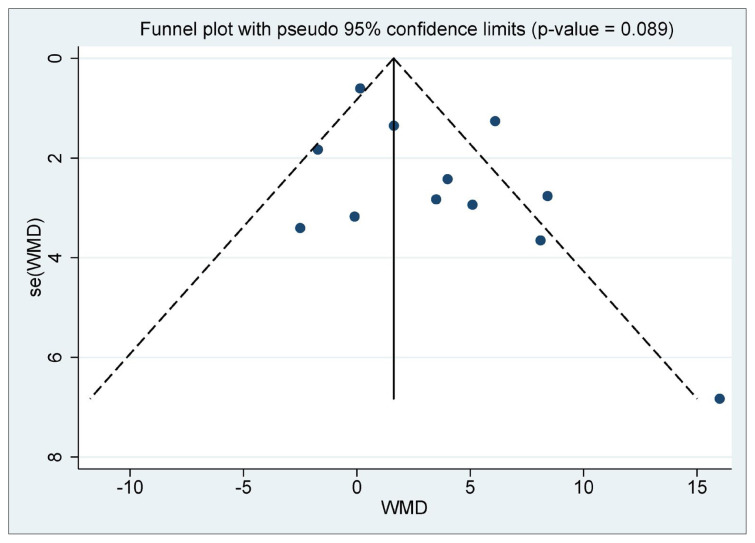

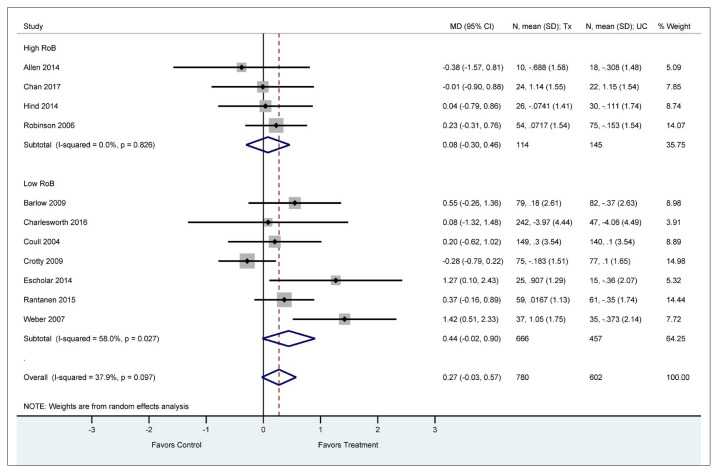

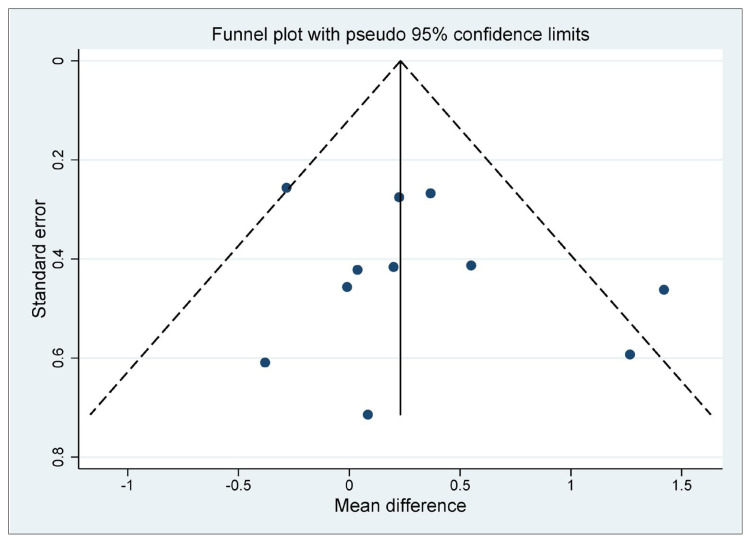

Meta-analysis of 12 trials (n = 1,521) that reported physical functioning(31–36,41,47,49,51,54,57) showed that participants who received volunteer support had statistically significant improvement in physical function compared to those who received usual care (MD = 3. 1 points [95% CI: 0.87 to 5.24 points] on a 100-point SF-36 physical component score; I2 = 72.0%, low certainty evidence) (Figure 3, Table 2). We found no evidence of subgroup effect (Appendix D, Figures D.1, D.2, D.3, D.4) or a small study effect (p value for the Egger’s test = 0.089, Appendix D, Figure D.5).

FIGURE 3.

Physical function (mean difference SF-36 PCS)

TABLE 2.

GRADE summary of findings

| Outcome Timeframe | Study Results and Measurements | Absolute Effect Estimates Usual Care Volunteers | Certainty of Evidence | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxietya Longest follow-up | Measured by: HADS-A1 Scale: 11–21 Lower better Based on data from 920 patients in 5 studies Follow up longest follow-up (average 34.4 wks) |

0.36 Mean |

0.32 Mean |

Moderate Due to serious risk of biasb |

| Difference: MD 0.04 lower (CI 95% 0.56 higher to 0.65 lower) | ||||

|

| ||||

| Depressionc Longest follow-up | Measured by: HADS-D Scale: 11–21 Lower better Based on data from 1382 patients in 11 studies Follow up longest follow-up (average 24.2 wks) |

0.43 Mean |

0.16 Mean |

Low Due to serious risk of bias, Due to serious imprecisiond |

| Difference: MD 0.27 lower (CI 95% 0.03 higher to 0.57 lower) | ||||

|

| ||||

| Emotional Functioninge Longest follow-up | Measured by: Mental Component Summary score (SF-36) Scale: 0–100 High better Based on data from 1341 patients in 10 studies Follow up longest follow-up (average 26.6 wks) |

1.84 Mean |

1.50 Mean |

Moderate Due to serious risk of biasf |

| Difference: MD −0.34 lower (CI 95% 1.22 lower to 0.54 higher) | ||||

|

| ||||

| Physical Functioningg Longest follow-up | Measured by: Physical Component Summary score (SF-36) Scale: 0–100 High better Based on data from 1521 patients in 12 studies Follow up longest follow-up (average 25.1 wks) |

0.62 Mean |

3.67 Mean |

Low Due to serious risk of bias, Due to serious inconsistency leading to imprecisionh |

| Difference: MD 3.05 higher (CI 95% 0.87 higher to 5.24 higher) | ||||

|

| ||||

| Quality of lifei Longest follow-up | Measured by: EQ-5D total score Scale: 0–1 High better Based on data from 1437 patients in 8 studies Follow up longest follow-up (average 39.2 wks) |

−0.02 Mean |

0.01 Mean |

Low Due to serious risk of bias, and publication bias (i.e. small study effect)j |

| Difference: MD 0.00 lower (CI 95% 0.02 lower to 0.01 higher) | ||||

| Physical Activity Longest follow-up | Measured by: MET (energy/kg/mns/wk); MVPA per week; minutes spent on exercise Scale: - High better Based on data from 1349 patients in 6 studies (average 10.2 months) |

Mean | Mean | Low Due to serious risk of bias and indirectnessk |

| Difference: SMD 0.48 more (CI 95% 0.14 more – 0.83 more) | ||||

|

| ||||

| Frequency of Hospital Admissions | Measured by: Narrative report: Admission rate not provided(37) and mean hospital admission rate per 1000 participants(58) | 2 studies reported hospitalization frequency. One qualitative report of no significant difference between groups.(37) Another study reported the incidence of hospitalization as (27.9/1000) in the intervention group versus (30.13/1000) control group (p = < .01) (58) | Low Due to serious risk of bias and inconsistencyl |

|

|

| ||||

| Falls | Measured by: Narrative report: Proportion of participants reporting one or more falls in the past 3 months (fallers)(51) and the incidence of falls(54) | 2 studies reported falls. One RCT reported the difference between proportion of fallers in the intervention group (14/35) versus (8/19) in the control group (P= 0.11)(51) Another study (cluster RCT) reported the incidence of falls in the intervention population (100/183) versus (158/217) in the control population (p = < .01)(54) | Low Due to serious risk of bias and inconsistencym |

|

|

| ||||

| Adverse Events | Narrative summary (results not pooled) | 6 studies reported adverse events, no events or no difference between groups was found(32,34,46,54,57) | Low Due to serious risk of bias and inconsistencyn |

|

HADS = Hospital Anxiety-Depression-Depression; HADS-A = Hospital Anxiety Depression-Anxiety; MET = Metabolic Equivalent Task, Energy used/per Kg/minute/week; MVPA +Time spent in moderate to vigorous physical activity.

All Measures converted to HADS-A.

Anxiety: Risk of bias: Serious. Inadequate/lack of blinding of outcome assessors, resulting in potential for detection bias, Incomplete data and/or large loss to follow up; Inconsistency: Serious. Imprecision: Not serious. Wide confidence intervals; decided not to rate down further for imprecision as it is due to inconsistency.; Publication bias: Not serious. Not assessed due to small number of studies.

All measures converted to HADS-D.

Depression: Risk of bias: Serious. Inadequate/lack of blinding of outcome assessors, resulting in potential for detection bias, Incomplete data and/or large loss to follow up.; Inconsistency: Serious. Point estimates vary widely, The confidence interval of some of the studies do not overlap with those of most included studies/ the point estimate of some of the included studies.; Imprecision: Not serious. Decided not to rate down for imprecision as it is mostly due to inconsistency.

Emotional Function: Risk of bias: Serious. Inadequate concealment of allocation during randomization process, resulting in potential for selection bias, Inadequate/lack of blinding of outcome assessors, resulting in potential for detection bias, Incomplete data and/or large loss to follow up; Inconsistency: Not serious. Decided not to rate further down as the observed heterogeneity seems to be due to risk of bias; Imprecision: Serious. Wide confidence intervals.

All measures converted to PCS score.

Physical Function: Risk of bias: Serious. Inadequate concealment of allocation during randomization process, resulting in potential for selection bias, Inadequate/lack of blinding of outcome assessors, resulting in potential for detection bias, Incomplete data and/or large loss to follow up.

All measures converted to EQ-5D total score.

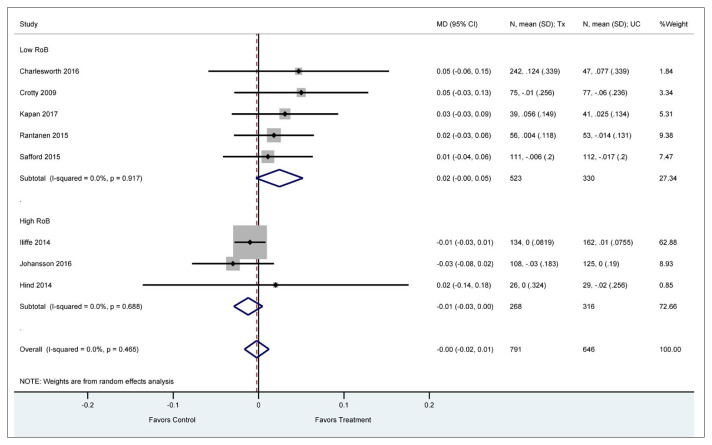

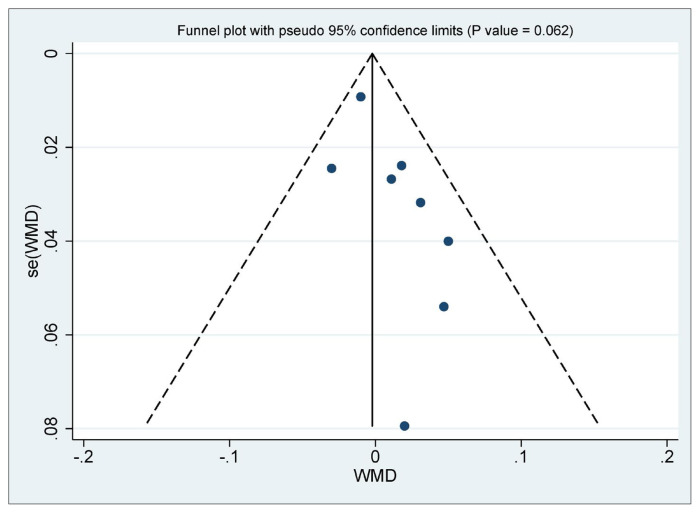

Quality of Life: Risk of bias: Serious. Incomplete data and/or large loss to follow up; significant test of interaction for the subgroup of low vs. high risk of bias due to missing participants data.; Publication bias: Serious. Asymmetrical funnel plot with evidence of small study effect.

Physical Activity: Risk of bias: Serious. Inadequate concealment of allocation during randomization process, resulting in potential for selection bias, Inadequate/lack of blinding of outcome assessors, resulting in potential for detection bias, Incomplete data and/or large loss to follow up; Inconsistency: Not serious. Decided not to rate further down as the observed heterogeneity seems to be due to risk of bias; Indirectness: Serious, Publication bias: Not serious. Less than 10 studies.

All measures converted to MCS.

Hospital admission: Risk of bias: Serious. Inadequate concealment of allocation during randomization process, resulting in potential for selection bias, inadequate/lack of blinding of outcome assessors; Inconsistency: Serious Uncertain effects narrative summary.

Falls: Risk of bias: Serious. Inadequate concealment of allocation during randomization process resulting in potential for selection bias; Inconsistency: Serious. Uncertain effects with narrative summary.

Averse events: Risk of bias: Serious. Inadequate/lack of blinding of assessors resulting in potential for detection bias, incomplete outcome reporting. Inconsistency: Serious Uncertain effects narrative summary.

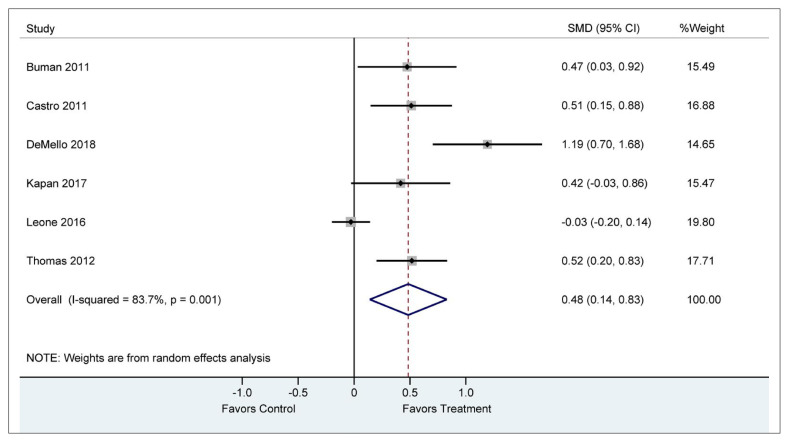

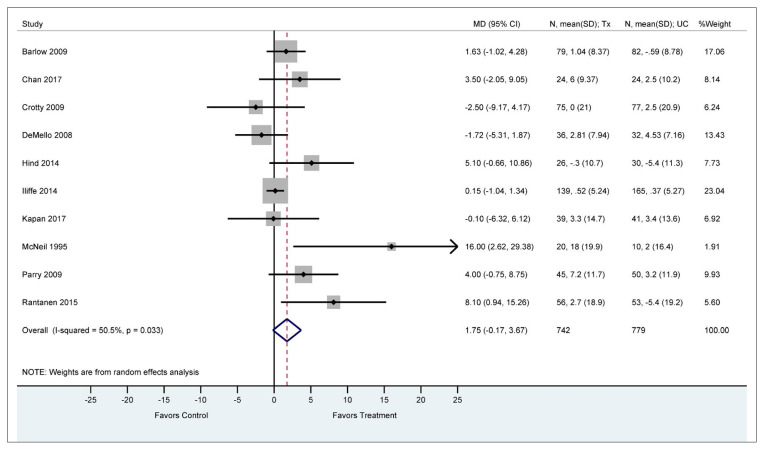

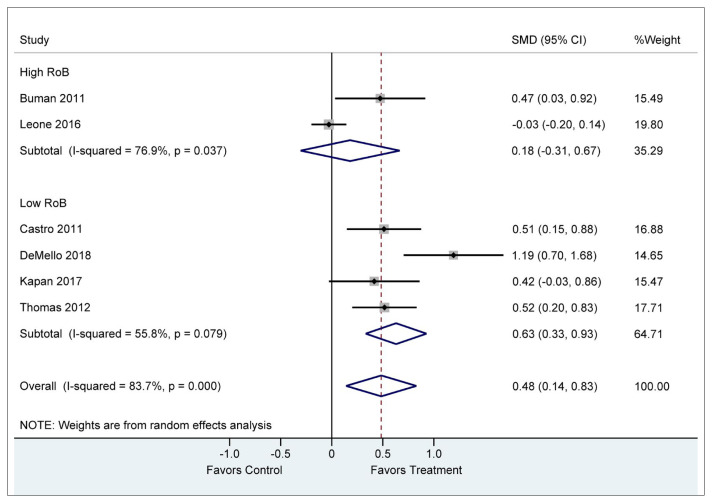

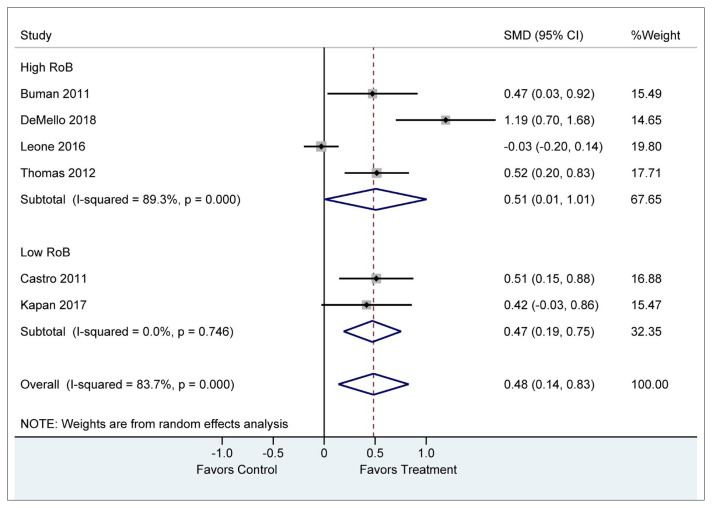

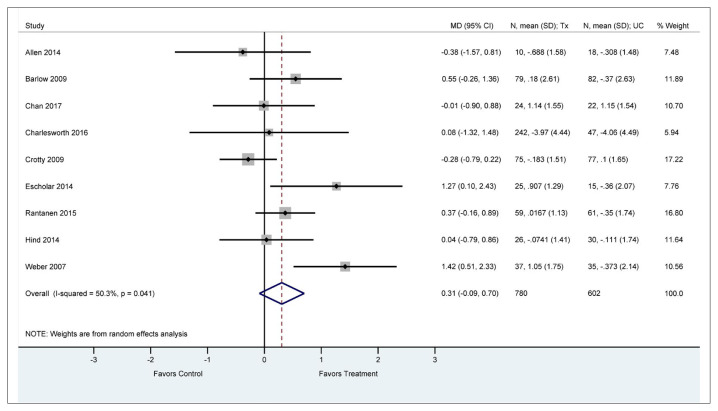

Among six included RCTs (n = 1,349) that reported physical activity, meta-analysis showed that participants who received volunteer support had statistically significant improvement in their physical activity levels compared to those who received usual care or no physical activity intervention(41,42,45,46,51,56) (SMD = 0.5 points [95% CI: 0.14 to 0.83]; I2 = 83.7%, low certainty evidence) (Figure 4, Table 2). We found no evidence of subgroup effect for adequate allocation concealment or blinding of assessors (Appendix E, Figures E.1, E.2).

FIGURE 4.

Physical activity (standardized mean differences)

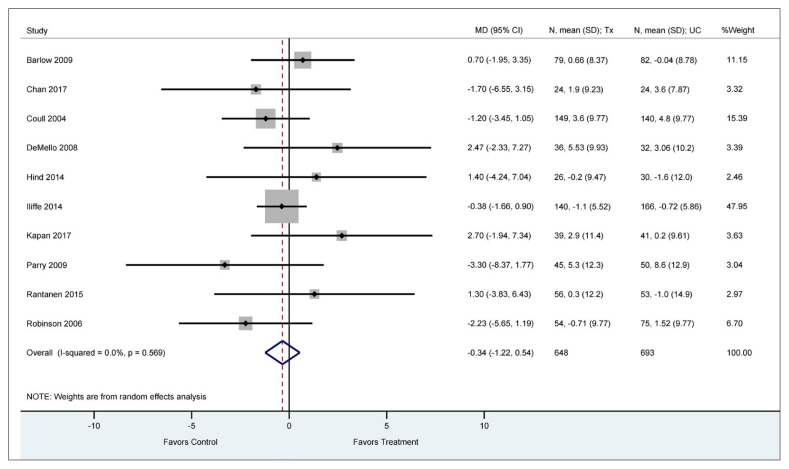

Mental Health

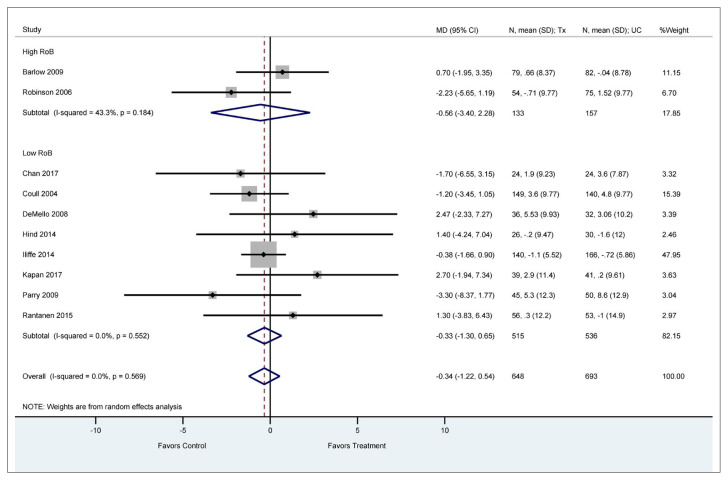

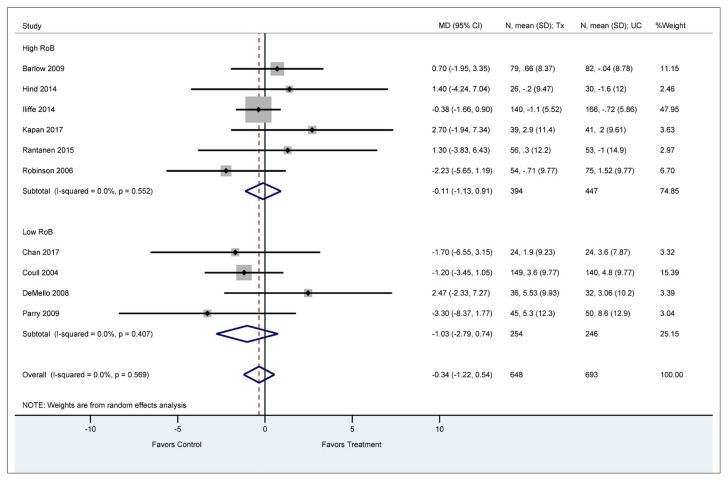

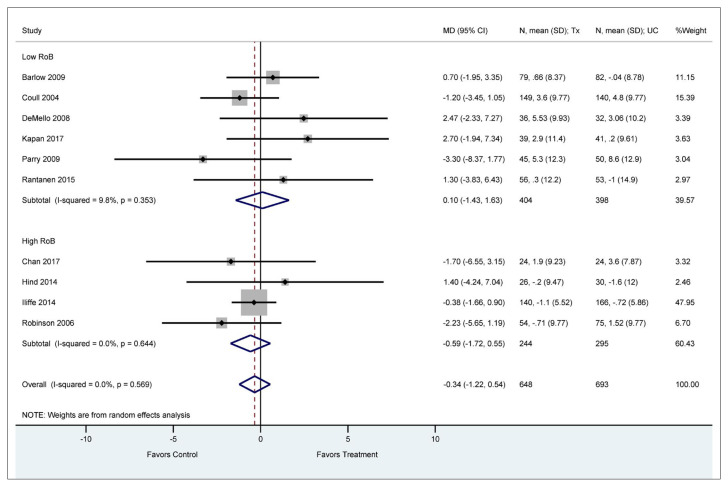

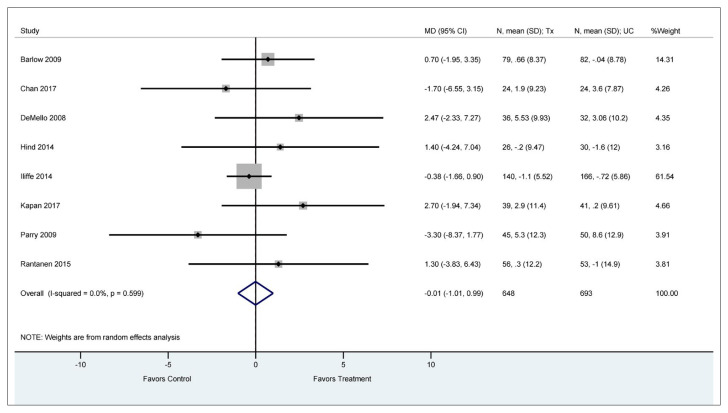

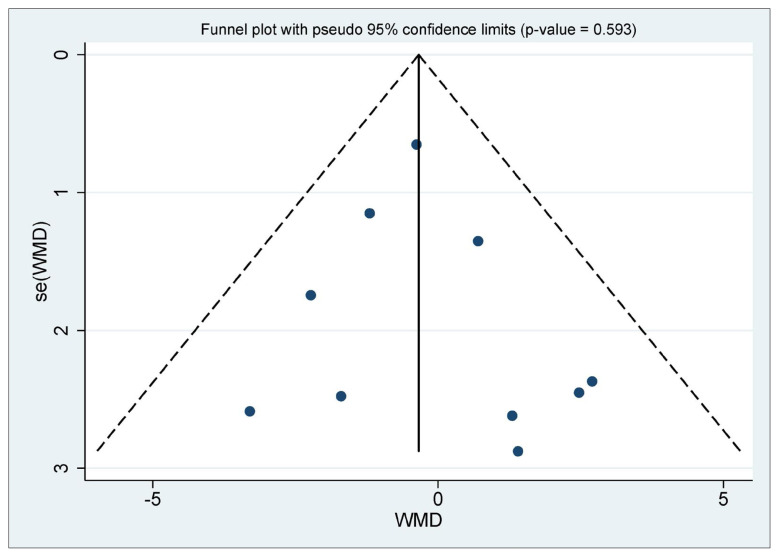

Meta-analysis of 10 trials (n = 1,341) that reported emotional functioning(31–36,41,47,51,54,57) showed no difference between participants receiving volunteer support compared to those who received usual care (MD = −0.34 points [95% CI: −1.22 to 0.54 points] on a 100-point SF-36 mental component score; I2 = 0%, low certainty evidence) (Figure 5, Table 2). We found no evidence of subgroup effect (Appendix F, Figures F.1, F.2, F.3, F.4) or small study effect (p value for the Egger’s test = 0.593, Appendix F, Figure F.5).

FIGURE 5.

Emotional function (mean difference SF-36 MCS)

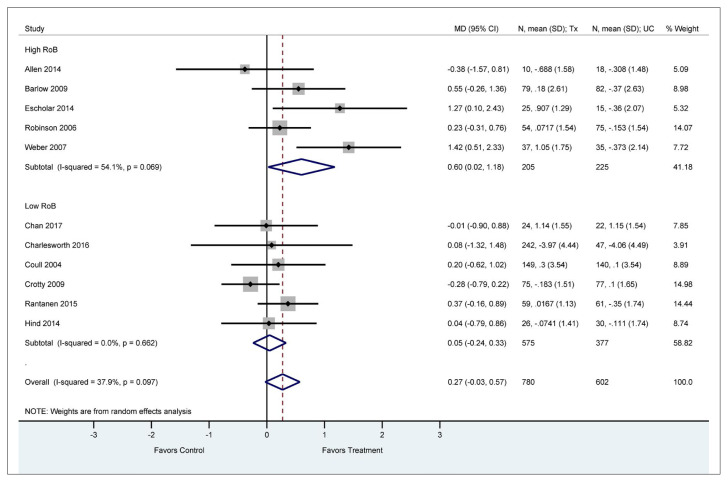

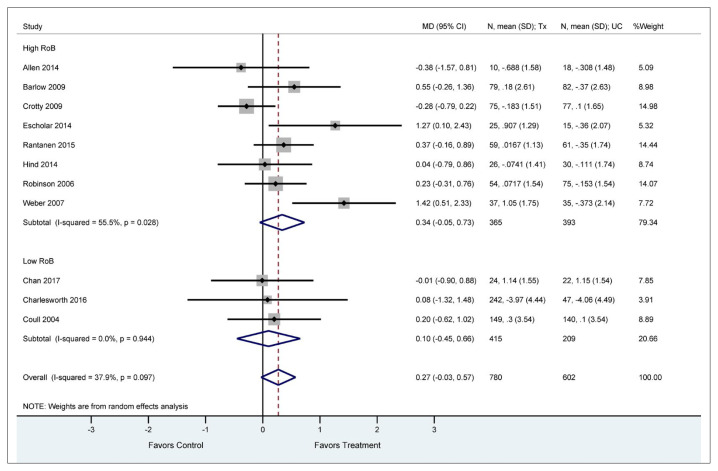

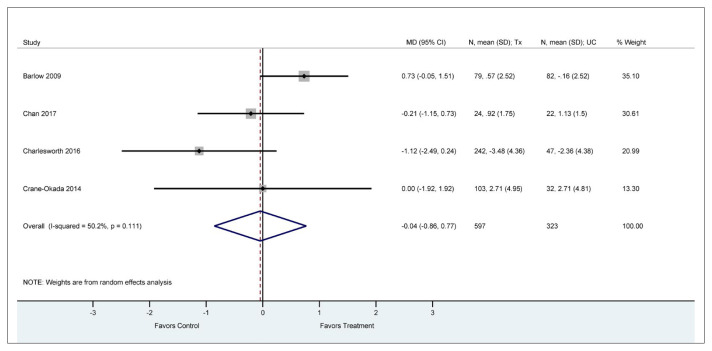

Meta-analysis of 11 trials (n = 1,382) that reported depression scores(31,32,34–36,43,47,48,52,53,57) showed no difference between participants receiving volunteer support compared to those who received usual care (MD = 0.3 points lower [95% CI: −1.17 to 0.58 points] on a 10-point HADS-depression subscale; I2 = 0%, low certainty evidence) (Figure 6, Table 2). We found no evidence of subgroup effect (Appendix G, Figures G.1, G.2, G.3, G.4) or small study effect (p value for the Egger’s test = .356, Appendix G, Figure G.5).

FIGURE 6.

Depression (mean difference HADS)

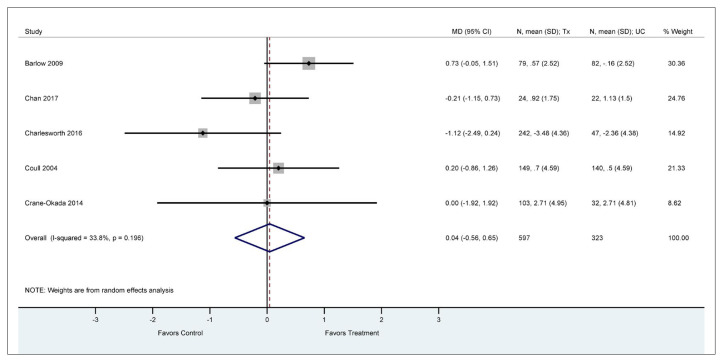

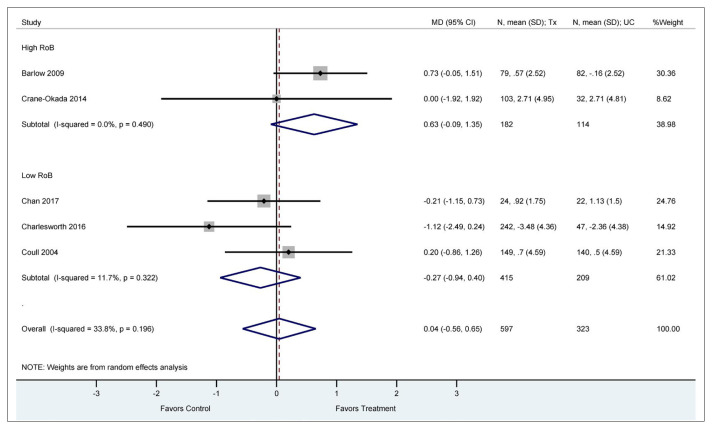

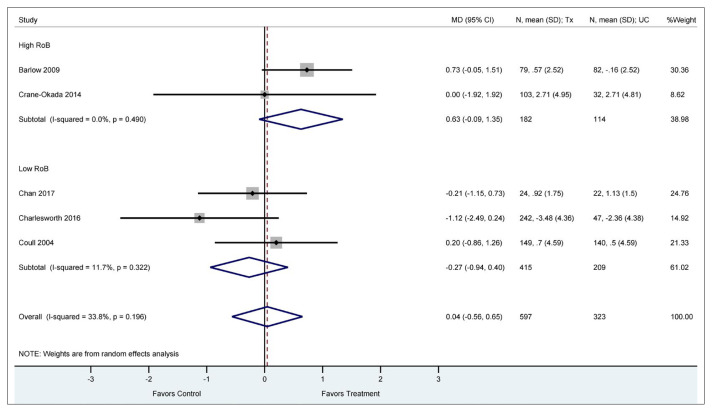

Meta-analysis of 5 trials (n = 920) that reported anxiety scores(31,32,40,47,48) showed no difference between participants receiving volunteer support compared to those who received usual care (MD = 0.04 points lower [95% CI: −0,56 to 0.65 points] on the 10-point HADS-anxiety subscale; I2 = 33.8%, low certainty evidence) (Figure 7, Table 2). We found no evidence of subgroup effect (Appendix H, Figures H.1, H.2, H.3).

FIGURE 7.

Anxiety (mean difference HADS)

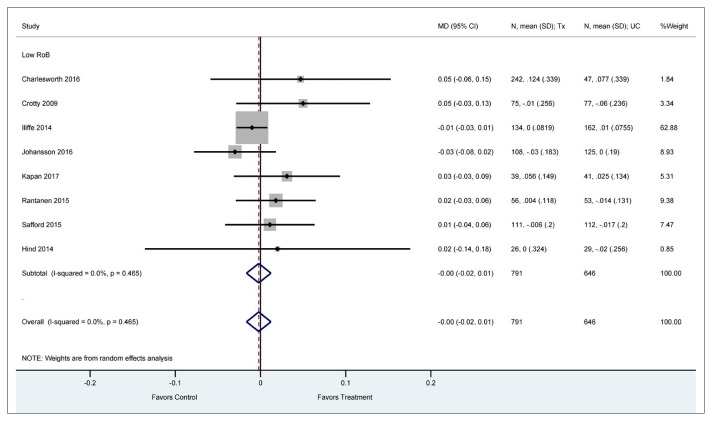

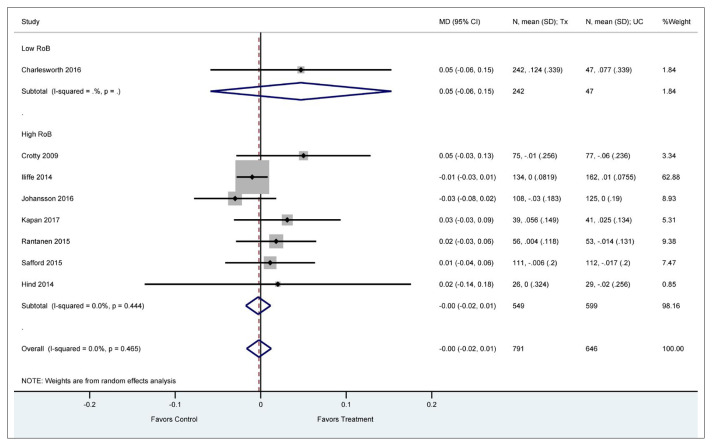

Quality of Life

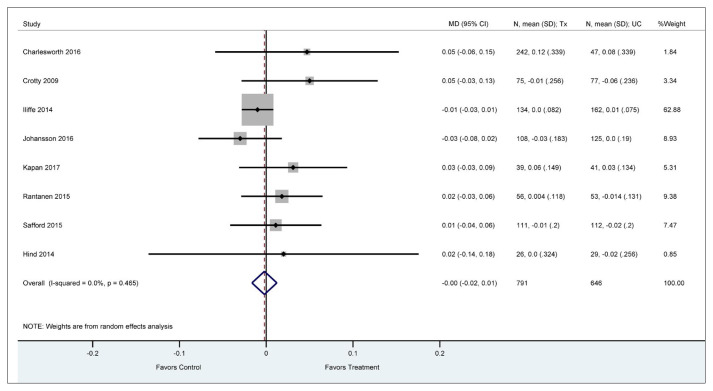

Meta-analysis of 8 studies (n = 1,437) that reported quality of life(34,35,38,39,48,51,54,57) showed no difference between participants receiving volunteer support compared to those who received usual care or no intervention (MD = 0.00 points [95% CI: −0.02 to 0.01 points] on a 1 point EQ-5D Scale; I2 = 0%, low certainty evidence) (Figure 8, Table 2). We found evidence of a significant test of interaction for the subgroup of low versus high risk of bias due to missing participants data (p = .012). Studies at low risk of bias for missing participant data were not significantly associated with volunteer improvement in Quality of Life (>20%) (MD = 0.02 points [95% CI: 0.00 to 0.05 points]); I2 = 0%, p = .917. No other evidence for subgroup effects were noted (Appendix I, Figures I.1, I.2, I.3). Small study effect (publication bias) was not detected (Eggers Test = 0.062) (Appendix I, Figure I.4).

FIGURE 8.

Quality of life (mean difference EQ5D)

Falls

Two included RCTs reported falls using different metrics, the incidence of falls(54) and the proportion of fallers,(51) and were not pooled, but summarized narratively, as follows. For frail older adults, a 12-week structured physical training and nutrition intervention carried out by lay volunteers showed a decrease in the proportion of fallers, but not reaching significance (p = .11).(51) For seniors over 65 years of age drawn from a general practice population (stable chronic health conditions), a class-based community falls management exercise program delivered by peer mentors significantly reduced falls by 18% (p < .01)(54) and increased self-reported physical activity 12 months after the intervention.

Hospitalization

Two included RCTs reporting hospitalization were not pooled, as one study reported the mean admission rate per 1000 population(58) and the other provided a descriptive report of admission (quantitative rate not provided).(37) A cluster randomized trial of a cardiovascular health awareness program delivered by volunteers versus no intervention reported a 9% adjusted relative reduction in cardiac-related admissions (95% confidence interval 0.86 to 0.97; p = .002), although all cause admissions were not reduced.(58) A diabetes education program provided by professionals versus peer volunteers reported that “few hospitalizations were recorded in the overall population sample, with no significant difference between groups during the study.”(37)

Adverse Events

Six included studies reported surveillance for adverse events or harms, three reported no adverse events occurring for patients or volunteers,(34,46,57) and two studies reported no difference between study arms.(32,54) One non-critical event occurred when one volunteer experienced discomfort when a caregiver stepped out of the boundaries of a befriending role.(48)

DISCUSSION

We identified 27 unique RCTs addressing the impact of unpaid volunteers on the health of older adults residing in the community, almost all taking place in high-income countries, focusing on seniors living with a range of health conditions and health states. Volunteers addressed a diversity of health needs and goals and represented a variety of roles. Despite this diversity (moderate to high heterogeneity) that was not explained by study risk of bias or participants’ age or sex, our results support the role of volunteers to improve physical function and physical activity levels for seniors. This benefit for increased physical activity and self-reported physical health was identified regardless of the health condition being targeted (e.g. recent myocardial infarction,(31,32), dysphoria,(49) severe physical disabilities,(36) cancer,(40–42,44) or recent hip surgery,(34) or the volunteer role provided (e.g., lay tutor,(31) lay mentor,(32) volunteer student,(49) or peer support(36,38)).

Analysis for depression trended toward favouring volunteer support, although, it did not reach statistical significance. There was no volunteer effect noted for anxiety or for senior’s emotional function. Anxiety levels were particularly worse for carers of people with dementia who were supported by friendship volunteers (compared to usual care), and this study appears to be driving the overall effect on anxiety; however, anxiety was a secondary outcome in this study. Of note, depression scores from this study (a primary outcome) approached statistically significant improvement for these befriended carers (95% CI −0.09 to 2.84, p = .06).(48) Quality of life as measured by five studies with low risk of bias for missing participant data (<20%) trended toward a volunteer effect, although it was not significant. For the two studies which reported falls, the incidence of falls was significantly reduced in one, but the proportion of fallers was not significantly reduced in the other.(51,54) This may be explained by differences in the study population and/or differences in the type and duration of volunteer intervention. The proportion of fallers among frail elderly individuals who received home-based physical training from volunteer buddies for 12 weeks was not significantly reduced.(51) Whereas the number of falls was significantly reduced for more robust seniors who received a class-based community exercise plus walking program for 24 weeks.(54) Hospitalization rates were no different for professional diabetic educators compared to peer volunteer educators,(37) while cardiovascular related admissions were significantly reduced for a volunteer delivered, community-based cardiovascular awareness intervention.(58) Adverse events were monitored in six studies and reported as either no events or no significant event difference. Heterogeneity was not explained by any analyses conducted.

Findings in Context

To our knowledge this is the first review to specifically synthesize trial-level data for the impact of unpaid volunteers on health-related outcomes for older adults living in the community with a variety of primary care conditions. Although indirect from our intervention of interest for unpaid volunteers, one review that focused on peer-supporters (paid and unpaid) for those living with diabetes (no age specification), also found a positive association with improvements in physical activity.(59) Other reviews of paid lay health workers in primary and community care provided a narrative report of improved health-related behavior, including increased physical activity,(60) with mixed results for mental and physical function.(13) Other outcomes of interest were not summarized in these reviews, however participants were generally satisfied with lay health worker encounters and increased their knowledge of disease and self-management.(60)

These findings of physical health benefit have implications for functional ability and independence for older adults in the community. Both regular physical activity and short-term exercise programs are associated with significantly reduced risk of functional limitations and disability in older adults across a range of functional measures.(61) Relatedly, robust evidence from two Cochrane reviews support exercise as effective falls prevention interventions;(62,63) this was achieved with only half of community-dwelling older participants adhering to exercise interventions.(61) Since falls represent the leading cause of fatal and non-fatal injuries among adults aged 65 and older, it is conceivable that trained volunteers supporting adherence to exercise guidance(62) could reduce falls and associated disability, thereby maintaining independence for aging in place. Consistent with this supposition, we also found that falls were significantly reduced for community-based seniors over 65 years of age (with stable chronic health conditions), who received a six-month falls management exercise program,(54) and for frail elderly receiving a 12-week structured physical training and nutrition program, although not reaching significance in this population (p = .10).(51)

Although heterogeneity across volunteer interventions limits identification of specific predictors of improved health outcomes, the observed benefit may be attributed to both the natural motivation of volunteers to help, and to the frequently used volunteer interventions of informational and emotional support, social connection and feedback on goal progress, which are consistent with social support(64) and self-efficacy theories.(65) Given that analyses for depression and possibly quality of life (considering low risk of bias studies) favoured volunteer interventions but were not statistically significant, further study of how volunteers can be best integrated into delivery processes of community-based care is warranted.

Limitations

Certainty of evidence was low mainly due to high risk of bias and inconsistency, and generalizability is limited to high-income countries. Heterogeneity (moderate to high) was not explained by study risk of bias items, imputed variability estimates, mean participant age, or proportion of female participants. Diverse volunteer characteristics and contexts (e.g., roles, activities, volunteer support and training, recipient health conditions, underlying theoretical basis for volunteer interventions), as well as the variety of terms used to describe such volunteer characteristics, limited subgroup analyses of ‘like’ studies that would allow for inference about volunteer variables and their impact on outcomes of interest. Agreed upon terms and definitions to describe volunteers (e.g., peer, mentor, counselor, tutor, educator, buddy, befriender, facilitator, guide), as well as development of a volunteer taxonomy (e.g., roles, activities, theoretical basis for volunteer interventions, duration of volunteer training and contact with recipients), would allow for better understanding of optimal volunteer conditions and their impacts.

CONCLUSIONS

We found evidence to support the role of volunteers to increase physical activity levels for seniors and to improve their subjective ratings of physical health, without harm. As relevant indicators of therapeutic success, particularly for independent living in older people, these findings align with the WHO call to action on aging. Policymakers, clinical leaders, health system planners, volunteer organizations, and others could make use of this synthesized evidence to consider the role of volunteers in health system planning for aging populations.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We wish to acknowledge the following individuals for their assistance with database searching and initial study screening: Mehreen Bhamani, Jennifer Longaphy, Steve Dragos, Stephanie Di Pelino, and Fiona Parascandalo. We are particularly grateful to Lynda Nash for her logistics expertise and administrative leadership.

APPENDIX A. Search strategy, including Ovid MEDLINE(R) and Epub Ahead of Print, In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, Daily and Versions(R), 1946 to November 1, 2018

| Searches | Results | Type |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Aged/ | 2832463 |

| 2 | “Aged, 80 and over”/ | 819963 |

| 3 | *Aging/ | 137261 |

| 4 | *Geriatrics/ | 25515 |

| 5 | ((55 year? or 65 year? or 75 year?) adj2 (above or older or over or plus)).ti,ab,kw. | 27254 |

| 6 | (“55 and over” or “65 and over” or “75 and over”).ti,ab,kw. | 3586 |

| 7 | ((aged or elderly or geriatric* or old or older or senior?) adj2 (adult? or citizen? or individual? or people or person?)).ti,ab,kw. | 193136 |

| 8 | 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 | 3033016 |

| 9 | * Community Health Workers / | 3151 |

| 10 | *Health Auxiliary/ | 0 |

| 11 | Hospital Volunteers/ | 1295 |

| 12 | *Mentors/ | 5337 |

| 13 | *Mentor/ | 5337 |

| 14 | PEER GROUP/ | 18404 |

| 15 | Counseling/ or Peer Group/ | 51411 |

| 16 | Peers/ | 0 |

| 17 | exp Peer Group/ | 18670 |

| 18 | VOLUNTEERS/ | 9083 |

| 19 | “Voluntary Worker”.mp. or Volunteers/ | 9087 |

| 20 | (lay worker? or voluntary worker? or volunteer* or peer* or (train* adj2 student?)).ti,ab,kw. | 259231 |

| 21 | 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 or 20 | 309427 |

| 22 | 8 and 21 | 43546 |

| 23 | limit 22 to humans | 42659 |

| 24 | HOSPITALIZATION/ | 95288 |

| 25 | Accidental Falls/ | 21340 |

| 26 | “Quality of Life”/ | 168131 |

| 27 | Mental Health/ | 32075 |

| 28 | Physical Health.mp. [mp=title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, floating sub-heading word, keyword heading word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier, synonyms] | 17414 |

| 29 | “EQ5D”.mp. | 456 |

| 30 | Quality-Adjusted Life Years/ or Cost-Benefit Analysis/ or “Quality of Life”/ | 239968 |

| 31 | 23 and (24 or 25 or 26 or 27 or 28 or 29 or 30) | 2412 |

| 32 | limit 31 to (humans and randomized controlled trial) | 565 |

| 33 | limit 31 to (humans and systematic reviews) | 152 |

| 34 | Exercise/ | 94722 |

| 35 | Physical activity.mp. | 92922 |

| 36 | 23 and (24 or 25 or 26 or 27 or 28 or 29 or 30 or 34 or 35) | 3779 |

| 37 | limit 36 to (humans and randomized controlled trial) | 879 |

| 38 | limit 37 to (humans and systematic reviews) | 18 |

APPENDIX B. Data extraction form

| Data Item |

|---|

| Study ID |

| Study (First Author Name) |

| Trial Arm (Intervention/Control) |

| Number Randomized |

| Comments |

| Scale (add outcome definition if necessary) |

| Direction of Scoring (1 higher = better, 2 higher = worse) |

| Range of Scale |

| Follow up Time (weeks) |

| Other Follow Up Times |

| Number Analyzed |

| Baseline Mean |

| Baseline SD |

| Follow Up (Effect Size) |

| Follow Up (Standard deviation) |

| Change (Effect Size) |

| Change (Standard Deviation) |

APPENDIX C. Risk of bias (individual studies)

APPENDIX D. Physical function (mean difference SF-36 physical component score-100 point scale)

D.1.

Physical function (subgroup analysis—allocation concealed adequately)

D.2.

Physical function (subgroup analysis—outcome assessors adequately blinded)

D.3.

Physical function (subgroup analysis—incomplete reporting, >20%, missing participant data)

D.4.

Physical function (sensitivity analysis—excluding studies with imputed SD)

D.5.

Physical function funnel plot (small study effect not significant; p value for Egger’s test = .06); meta-regression: no covariates (physical health) explained observed heterogeneity

APPENDIX E. Physical activity (standardized mean difference)

E.1.

Physical activity (subgroup analysis—adequately concealed allocation)

E.2.

Physical activity (subgroup analysis—outcome assessors blinded); analyses for incomplete outcome reporting and imputed standard deviation not relevant (no studies affected); not enough studies to test for small study effect (publication bias)

APPENDIX F. Emotional function (mean difference SF-36 mental component score-100 point scale)

F.1.

Emotional function (subgroup analysis—adequately concealed allocation)

F.2.

Emotional function (subgroup analysis—outcome assessor adequately blinded)

F.3.

Emotional function (subgroup analysis—incomplete reporting >20% missing participant data)

F.4.

Emotional function (subgroup analysis—excluding studies with imputed standard deviation)

F.5.

Emotional function funnel plot (small study effect not significant; p value for Egger’s test = .589)

APPENDIX G. Depression (mean difference HADS-10 point scale)

G.1.

Depression (subgroup analysis—adequately concealed allocation)

G.2.

Depression (subgroup analysis—outcome assessors adequately blinded)

G.3.

Depression (subgroup analysis—incomplete reporting >20% missing participant data)

G.4.

Depression (sensitivity analysis—excluding studies with imputed standard deviation)

G.5.

Depression funnel plot (small study effect not significant; p value for Egger’s test = .356)

APPENDIX H. Anxiety (mean difference HADS-10 point scale)

H.1.

Anxiety (subgroup analysis—adequately concealed allocation)

H.2.

Anxiety (subgroup analysis—outcome assessors adequately blinded)

H.3.

Anxiety (sensitivity analysis—excluding studies with imputed standard deviation)

APPENDIX I. Quality of life (EQ 5D; 0–1 point scale)

I.1.

Quality of life (subgroup analysis—adequately concealed allocation)

I.2.

Quality of life (subgroup analysis—outcome assessors adequately blinded)

I.3.

Quality of life (subgroup analysis—incomplete reporting >20% missing participant data)

I.4.

Quality of life funnel plot (small study effect significant; p value Egger’s test = .054)

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

The authors declare that no conflicts of interest exist.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. Global strategy and action plan on ageing and health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2017. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3, 0 IGO. Available from: https://www.who.int/ageing/WHO-GSAP-2017.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.United Nations DoEaSA, Population Division. World population prospects: comprehensive tables (ST/ESA/SER.A/399) New York: United Nations; 2017. Available from: https://population.un.org/wpp/Publications/Files/WPP2017_Volume-I_Comprehensive-Tables.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gilburt H, Buck D, Smith J. Volunteering in general practice: opportunities and insights. London, UK: The King’s Fund; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dorgo S, King GA, Bader JO, et al. Comparing the effectiveness of peer mentoring and student mentoring in a 35-week fitness program for older adults. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2011;52(3):344–49. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2010.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rantakokko M, Pakkala I, Äyräväinen I, et al. The effect of out-of-home activity intervention delivered by volunteers on depressive symptoms among older people with severe mobility limitations: a randomized controlled trial. Aging Ment Health. 2015;19(3):231–38. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2014.924092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dorgo S, Robinson KM, Bader J. The effectiveness of a peer-mentored older adult fitness program on perceived physical, mental, and social function. J Am Acad Nurse Prac. 2009;21(2):116–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2008.00393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luger E, Dorner TE, Haider S, et al. Effects of a home-based and volunteer-administered physical training, nutritional, and social support program on malnutrition and frailty in older persons: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016;17(7):671.e9–e16. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2016.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dale J, Caramlau IO, Lindenmeyer A, et al. Peer support telephone calls for improving health. Cochrane Db Syst Rev. 2008;(4) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meyer A, Coroiu A, Korner A. One-to-one peer support in cancer care: a review of scholarship published between 2007 and 2014. Eur J Cancer Care. 2015;24(3):299–312. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Avery A, Bostock L, McCullough F. A systematic review investigating interventions that can help reduce consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages in children leading to changes in body fatness. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2015;28(Suppl 1):52–64. doi: 10.1111/jhn.12267. Epub 09/19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lewin S, Dick J, Pond P, et al. Lay health workers in primary and community health care. Cochrane Db Syst Rev. 2005;(1) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004015.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dolovich L, Oliver D, Lamarche L, et al. Combining volunteers and primary care teamwork to support health goals and needs of older adults: a pragmatic randomized controlled trial. CMAJ. 2019;191(18):E491–E500. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.181173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rutherford A, Bu F, Dawson A, et al. Literature review to inform the development of Scotland’s volunteering outcomes framework: People, communities and places. Edinburgh: Govt. of Scotland; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ware JE, Dewey JE, Kosinski M. How to score Version 2 of the SF-36 Health Survey (Standard and Acute forms) 3rd ed. ed. Lincoln, RI: QualityMetric; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Theiler R, Spielberger J, Bischoff HA, et al. Clinical evaluation of the WOMAC 3.0 OA Index in numeric rating scale format using a computerized touch screen version. Osteoarthr Cartilage. 2002;10(6):479–81. doi: 10.1053/joca.2002.0807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Skevington SM, Lotfy M, O’Connell KA. The World Health Organization’s WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment: psychometric properties and results of the international field trial. A report from the WHOQOL Group. Qual Life Res. 2004;13(2):299–310. doi: 10.1023/B:QURE.0000018486.91360.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moore SC, Patel AV, Matthews CE, et al. Leisure time physical activity of moderate to vigorous intensity and mortality: a large pooled cohort analysis. PLoS Med. 2012;9(11):e1001335. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001335. Epub 11/06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jetté M, Sidney K, Blümchen G. Metabolic equivalents (METS) in exercise testing, exercise prescription, and evaluation of functional capacity. Clin Cardiol. 1990;13(8):555–65. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960130809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Veit CT, Ware JE. The structure of psychological distress and well-being in general populations. J Consult Clin Psych. 1983;51(5):730–42. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.51.5.730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR, Roberts RE, et al. Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) as a screening instrument for depression among community-residing older adults. Psychol Aging. 1997;12(2):277–87. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.12.2.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, et al. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res. 1982;17(1):37–49. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(82)90033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ravens-Sieberer U, Wille N, Badia X, et al. Feasibility, reliability, and validity of the EQ-5D-Y: results from a multinational study. Qual Life Res. 2010;19(6):887–97. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9649-x. Epub 04/17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, et al. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. 2nd ed. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 2019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Akl EA, Sun X, Busse JW, et al. Specific instructions for estimating unclearly reported blinding status in randomized trials were reliable and valid. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65(3):262–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336(7650):924–26. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thorlund K, Walter SD, Johnston BC, et al. Pooling health-related quality of life outcomes in meta-analysis—a tutorial and review of methods for enhancing interpretability. Res Synthesis Meth. 2011;2(3):188–203. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Altman DG, Bland JM. Interaction revisited: the difference between two estimates. BMJ. 2003;326(7382):219. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7382.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sterne JAC, Sutton AJ, Ioannidis JP, et al. Recommendations for examining and interpreting funnel plot asymmetry in meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d4002. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d4002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barlow JH, Turner AP, Gilchrist M. A randomised controlled trial of lay-led self-management for myocardial infarction patients who have completed cardiac rehabilitation. Eur J Cardiovasc Nur. 2009;8(4):293–301. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coull AJ, Taylor VH, Elton R, et al. A randomised controlled trial of senior Lay Health Mentoring in older people with ischaemic heart disease: The Braveheart Project. Age Ageing. 2004;33(4):348–54. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afh098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parry MJ, Watt-Watson J, Hodnett E, et al. Cardiac home education and support trial (CHEST): a pilot study. Can J Cardiol. 2009;25(12):e393–e398. doi: 10.1016/S0828-282X(09)70531-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Crotty M, Prendergast J, Battersby MW, et al. Self-management and peer support among people with arthritis on a hospital joint replacement waiting list: a randomised controlled trial. Osteoarthr Cartilage. 2009;17(11):1428–33. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2009.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rantanen T, Äyräväinen I, Eronen J, et al. The effect of an outdoor activities’ intervention delivered by older volunteers on the quality of life of older people with severe mobility limitations: a randomized controlled trial. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2015;27(2):161–69. doi: 10.1007/s40520-014-0254-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Robinson-Whelen S, Hughes RB, Taylor HB, et al. Improving the health and health behaviors of women aging with physical disabilities: a peer-led health promotion program. Women’s Health Issues. 2006;16(6):334–45. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2006.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gagliardino JJ, Arrechea V, Assad D, et al. Type 2 diabetes patients educated by other patients perform at least as well as patients trained by professionals. Diabetes/Metabol Res Rev. 2013;29(2):152–60. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.2368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Johansson T, Keller S, Winkler H, et al. Effectiveness of a Peer Support Programme versus Usual Care in Disease Management of Diabetes Mellitus Type 2 regarding Improvement of Metabolic Control: A Cluster-Randomised Controlled Trial. J Diabetes Res. 2016;2016:10. doi: 10.1155/2016/3248547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Safford MM, Andreae S, Cherrington AL, et al. Peer coaches to improve diabetes outcomes in rural Alabama: a cluster randomized trial. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13(Suppl 1):S18–S26. doi: 10.1370/afm.1798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Crane-Okada R, Freeman E, Kiger H, et al. Senior peer counselling by telephone for psychosocial support after breast cancer surgery: effects at six months. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2012;39(1):78–89. doi: 10.1188/12.ONF.78-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.DeMello MM, Pinto BM, Mitchell S, et al. Peer support for physical activity adoption among breast cancer survivors: Do the helped resemble the helpers? Eur J Cancer Care. 2018;27(3):e12849. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12849. Epub 04/10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Leone LA, Allicock M, Pignone MP, et al. cluster randomized trial of a church-based peer counselor and tailored newsletter intervention to promote colorectal cancer screening and physical activity among older African Americans. Health Educ Behav. 2016;43(5):568–76. doi: 10.1177/1090198115611877. Epub 10/29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weber BA, Roberts BL, Yarandi H, et al. The impact of dyadic social support on self-efficacy and depression after radical prostatectomy. J Aging Health. 2007;19(4):630–45. doi: 10.1177/0898264307300979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.White V, Macvean M, Grogan S, et al. Can a tailored telephone intervention delivered by volunteers reduce the supportive care needs, anxiety and depression of people with colorectal cancer? A randomised controlled trial. Psychooncology. 2012;21(10):1053–62. doi: 10.1002/pon.2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Buman MP, Giacobbi PR, Jr, Dzierzewski JM, et al. Peer volunteers improve long-term maintenance of physical activity with older adults: a randomized controlled trial. J Phys Act Health. 2011;8(Suppl 2):S257–S266. doi: 10.1123/jpah.8.s2.s257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Castro CM, Pruitt LA, Buman MP, et al. Physical activity program delivery by professionals versus volunteers: the TEAM randomized trial. Health Psychol. 2011;30(3):285–94. doi: 10.1037/a0021980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chan AW, Yu DS, Choi KC. Effects of tai chi qigong on psychosocial well-being among hidden elderly, using elderly neighborhood volunteer approach: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Clin Interv Aging. 2017;12:85–96. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S124604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Charlesworth G, Shepstone L, Wilson E, et al. Does befriending by trained lay workers improve psychological well-being and quality of life for carers of people with dementia, and at what cost? A randomised controlled trial. Health Technol Assess. 2008;12(4) doi: 10.3310/hta12040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McNeil JK. Effects of nonprofessional home visit programs for subclinically unhappy and unhealthy older adults. J Appl Gerontol. 1995;14(3):333–42. doi: 10.1177/073346489501400307. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Haider S, Dorner TE, Luger E, et al. Impact of a home-based physical and nutritional intervention program conducted by lay-volunteers on handgrip strength in prefrail and frail older adults: a randomized control trial. PloS one. 2017;12(1):e0169613. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kapan A, Winzer E, Haider S, et al. Impact of a lay-led home-based intervention programme on quality of life in community-dwelling pre-frail and frail older adults: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17(1):154. doi: 10.1186/s12877-017-0548-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Allen RS, Harris GM, Burgio LD, et al. Can senior volunteers deliver reminiscence and creative activity interventions? Results of the legacy intervention family enactment randomized controlled trial. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2014;48(4):590–601. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.11.012. Epub 03/22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Escolar Chua RL, de Guzman AB. Effects of third age learning programs on the life satisfaction, self-esteem, and depression level among a select group of community dwelling Filipino elderly. Educ Gerontol. 2014;40(2):77–90. doi: 10.1080/03601277.2012.701157. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Iliffe S, Kendrick D, Morris R, et al. Multicentre cluster randomised trial comparing a community group exercise programme and home-based exercise with usual care for people aged 65 years and over in primary care. Health Technol Assess. 2014;18(49) doi: 10.3310/hta18490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mountain GA, Hind D, Gossage-Worrall R, et al. ‘Putting Life in Years’ (PLINY) telephone friendship groups research study: pilot randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2014;15(1):141. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-15-141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Thomas GN, Macfarlane D, Guo B, et al. Health promotion in older Chinese: a 12-month cluster randomized controlled trial of pedometry and “peer support”. Med Sci Sports Exercise. 2012;44(6):1157–66. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318244314a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hind D, Gossage-Worral R, Walters S, et al. Putting Life in Years (PLINY): a randomised controlled trial and mixed-methods process evaluation of a telephone friendship intervention to improve mental well-being in independently living older people. Public Health Resh. 2014;2(7) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kaczorowski J, Chambers LW, Dolovich L, et al. Improving cardiovascular health at population level: 39 community cluster randomised trial of Cardiovascular Health Awareness Program (CHAP) BMJ. 2011;342:d442. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tang TS, Ayala GX, Cherrington A, et al. A review of volunteer-based peer support interventions in diabetes. Diabetes Spectrum. 2011;24(2):85–98. doi: 10.2337/diaspect.24.2.85. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Norris SL, Chowdhury FM, Van Le K, et al. Effectiveness of community health workers in the care of persons with diabetes. Diabetic Med. 2006;23(5):544–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.01845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Paterson DH, Warburton DE. Physical activity and functional limitations in older adults: a systematic review related to Canada’s Physical Activity Guidelines. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Activity. 2010;7(1):1–22. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-7-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cameron ID, Murray GR, Gillespie LD, et al. Interventions for preventing falls in older people in nursing care facilities and hospitals. Cochrane Db Syst Rev. 2010;(1) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005465.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gillespie LD, Robertson MC, Gillespie WJ, et al. Interventions for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Db Syst Rev. 2012;(9) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007146.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Langford CPH, Bowsher J, Maloney JP, et al. Social support: a conceptual analysis. J Adv Nurs. 1997;25(1):95–100. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.1997025095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bandura A, Cervone D. Self-evaluative and self-efficacy mechanisms governing the motivational effects of goal systems. J Personality Soc Psychol. 1983;45(5):1017–28. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.45.5.1017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]