Highlights

-

•

c-Myb attenuates NF-κB activity in breast cancer.

-

•

Interaction with co-activator p300 is required for NF-κB suppression by c-Myb.

-

•

c-Myb negatively regulates IL1a transcription in several ER- breast cancer cell lines.

-

•

Inhibition of IL1α expression mediates the anti-inflammatory effect of c-Myb.

Keywords: Breast cancer, c-Myb, IL1α, NF-κB, Inflammation, Transactivation

Abbreviations: BC, breast cancer; CBA, cytometric bead array; EMT, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition; ER, estrogen receptor; TEM, trans-endothelial migration

Abstract

The transcription factor c-Myb can be involved in the activation of many genes with protumorigenic function; however, its role in breast cancer (BC) development is still under discussion. c-Myb is considered as a tumor-promoting factor in the early phases of BC, on the other hand, its expression in BC patients relates to a good prognosis. Previously, we have shown that c-Myb controls the capacity of BC cells to form spontaneous lung metastasis. Reduced seeding of BC cells to the lungs is linked to high expression of c-Myb and a decline in expression of a specific set of inflammatory genes. Here, we unraveled a c-Myb-IL1α-NF-κB signaling axis that takes place in tumor cells. We report that an overexpression of c-Myb interfered with the activity of NF-κB in several BC cell lines. We identified IL1α to be essential for this interference since it was abrogated in the IL1α-deficient cells. Overexpression of IL1α, as well as addition of recombinant IL1α protein, activated NF-κB signaling and restored expression of the inflammatory signature genes suppressed by c-Myb. The endogenous levels of c-Myb negatively correlated with IL1α on both transcriptional and protein levels across BC cell lines. We concluded that inhibition of IL1α expression by c-Myb reduces NF-κB activity and disconnects the inflammatory circuit, a potentially targetable mechanism to mimic the antimetastatic effect of c-Myb with therapeutic perspective.

Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) is represented by a group of malignancies heterogeneous in their biological and clinical behavior [1]. Whereas overall survival rates improved over the years, the prognosis of patients diagnosed with metastatic disease remains poor, with an estimated 5-year survival rate lower than 30% [2,3]. Therefore, considerable attention is being paid to the investigation of molecular pathways governing the establishment of metastatic lesions.

The transcription factor c-Myb is known as a mammal homologue of the v-Myb oncoprotein causing leukemia in birds, and its expression has been connected with several human malignancies [4]. Studies of leukemia linked c-Myb to worse prognosis [5,6]; however, its role in colon and breast cancer remains controversial [7], [8], [9]. Although c-Myb is a prerequisite for mammary carcinogenesis in murine models in vivo [10], elevated c-Myb expression in BC is linked to excellent prognosis [11,12]. Expression of c-Myb in BC correlates with estrogen receptor (ER) positivity [13] as MYB is identified as a direct target of ER signaling [14]. Survival of patients diagnosed with the ER-positive BC is longer since they may benefit from the adjuvant ER-targeted endocrine therapy [15,16]. In addition, antiestrogens may induce MYB expression [17,18], thus the contribution of c-Myb to patient survival must be assessed with care and may vary in subgroups of BCs [12,19]. There are several studies suggesting that ER may not always be essential for increased c-Myb expression in BC [10,20], it may be induced or suppressed by various microenvironmental cues [21], [22], [23]. Initially, c-Myb was shown to maintain proliferation and impede differentiation of mammary cells [17,24]. Emerging data extended function of the c-Myb protein in adjusting plasticity of BC cells, as high proliferative state endowed by c-Myb was coupled with the acquisition of epithelial traits in some tumor cells [21]. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) occurs in carcinoma cells exiting the primary tumor site, furthermore, the reverse transition (MET) in disseminated cells appears to be required for outgrowth of secondary tumors. The direct transcriptional repression of c-Myb by EMT regulator ZEB1 is required for stabilization of a mesenchymal phenotype, proliferation arrest and possibly precedes seeding of tumor cells in distant locations [21]. However, the role of c-Myb in EMT appears to be more complex, presumably context-dependent, varying with different stimuli and stage of the transition [21,22,25,26]. In our previous report, we have shown that high levels of c-Myb in ER-negative BC cells reduced their lung seeding capacity in vivo accompanied by decreased expression of a specific set of inflammatory genes (Ccl2, Cxcl1, Cxcl2, Cxcl6, Cxcl16, Icam1, Il1a, Tnfrsf9, Lcn2, Ikbke - denoted as the c-Myb-inflammatory signature). Inhibition of Ccl2 expression by c-Myb was detrimental for migration of tumor cells through the lung endothelium, linking the c-Myb-governed transcriptional program with the control of transendothelial migration (TEM) [19]. Whether c-Myb may inhibit the inflammatory circuit by direct binding to the regulatory elements of the remaining signature genes and/or by interfering with relevant signaling pathways in BC cells remains to be elucidated. Here, we show that high c-Myb expression suppressed activity of NF-κB, a key inflammatory mediator, in BC.

The NF-κB protein family comprises pleiotropic transcription factors implicated in the control of expression of genes related to proliferation, survival, angiogenesis, metastasis, and immune response [27]. High NF-κB activity has been linked to worse prognosis in BC patients [28], [29], [30]. The NF-κB activation in cancer cells may be caused by mutations that affect signaling components or by the exposure to inflammatory cytokines in the tumor microenvironment [31]. IL1α is a cytokine that is expressed by epithelial, endothelial, and stromal cells under homeostatic conditions and its expression can be stimulated by a broad spectrum of inflammatory stimuli [32]. IL1α binds to the interleukin 1 receptor type 1 (IL-1R1) which can subsequently lead to NF-κB, c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), and p38 MAPK pathways activation [33]. Autocrine IL1α signaling in malignant BC cells, driven besides other stimuli by HER2, supports cancer stem-like cell maintenance and tumorigenesis by activating NF-κB and STAT3 pathways [34]. Similarly, in ER-positive MCF7 cells overexpression of IL1α lead to NF-κB activation and promoted tumor growth [35], while other studies connect this cytokine with the metastatic spread of BC cells [36,37]. Inhibition of IL-1R1 signaling by anakinra, clinically licensed IL-1R1 antagonist, reduced tumor burden and bone metastases in ER-negative and positive BC cells [38].

Here, we report that c-Myb inhibited cytokine IL1α expression in BC cells, which in turn led to a decline in autocrine signaling affecting the NF-κB pathway and the ability of BC cells to migrate and cross the endothelial barrier.

Material and methods

Cell culture, plasmids and reagents

E0771.LMB cells were kindly provided by Dr. Robin Anderson [39], all other cell lines were purchased from American Type Culture Collection. 4T1, MDA-MB-231, MCF7, T47D, BT-474 and BT-549 were cultured in RPMI-1640 (Sigma-Aldrich), SKBR3 were cultured in McCoy's 5A Modified Medium (Sigma-Aldrich), MDA-MB-468 and E0771.LMB cells were cultured in DMEM (Sigma-Aldrich). The cells of all lines were cultured at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2, media were supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen), 2mM L-glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Lonza). The medium of 4T1 cells was further supplemented with 1 mM sodium pyruvate and 4500 μg/mL D-Glucose (Sigma-Aldrich). HUVECs were cultured in Endothelial Basal Medium supplemented with EGM SingleQuots (Lonza). All cell lines were routinely tested for mycoplasma contamination by PCR. Plasmids are listed in Table S1. All prepared constructs were verified by Sanger sequencing. Il1a and IL1A marked murine and human genes respectively, and uniform IL1α is used for the protein. Similarly, we used Myb (mouse gene), MYB (human gene), and c-Myb for protein.

Recombinant IL1α (211-11A, PeproTech) was used in listed concentrations. JSH-23 (J4455, Sigma-Aldrich) was applied in concentration 20μM, IRAK1/4 inhibitor (I5409, Sigma-Aldrich) in concentration 10μM, and recombinant mouse IL-1ra/IL-1F3 protein (480-RM-010, R&D Systems) in concentration 300 ng/mL.

Transfections

For all transfections, Lipofectamine LTX (Life Technologies) was used. 4T1, E0771.LMB cells with constitutive c-Myb overexpression (Mybhigh) and MDA-MB-231 c-Myb knock-outs were described previously [19]. 4T1 and E0771.LMB cells overexpressing IL1α were prepared by transfection with pcDNA3.mIl1a (Table S1) and selected with G418 (800 μg/mL and 500 μg/mL, respectively) and cloned by limiting dilution. Similarly, MDA-MB-231 cells overexpressing human IL1A were transfected using pCMV14-3xflag_hIL1a (Table S1). Pool of transfected cells was selected with 500 μg/mL G418. To derive 4T1 IL1α knock-outs, 4T1 cells were transfected with one of the lentiCRISPRv2 plasmids (Table S1), selected with puromycin (1 μg/mL) for 2 wk and cloned by limiting dilution. PCR primers spanning potential sites of mutation were designed (Table S2), mutations were confirmed by the Sanger sequencing. IL1α overexpression/knock-out was verified by Cytometric Bead Array (CBA).

Transactivation assay

4T1 and E0771.LMB cells were transfected with the luciferase reporter plasmid pNF-κB-luc/mIl1a-luc, and CMV-βgal concomitant with wt Myb/M303V Myb/mock control vector and processed for luciferase and β-galactosidase assays 18 h after transfection as described elsewhere [40]. The luciferase activity was expressed in relative light units and normalized according to protein content measured by Bradford assay or for transfection efficiency according to the β-galactosidase activity.

RNA isolation and quantitative PCR (qPCR)

Total RNA was isolated using the GenElute Total RNA Purification Kit (Sigma-Aldrich) and cDNA using the QuantiTect RT Kit (Qiagen). qPCR was performed with KAPA SYBR Fast Master mix (KAPA Biosystems) with primers spanning exon-exon junctions (Table S3) using the LightCycler 480 (Roche).

Immunoblotting

Cell lysis and western blot analysis were performed as described elsewhere [41]. Following antibodies were used: c-Myb (05-175, Millipore), α-tubulin (T9026, Sigma), and horse antimouse (7076, CS) secondary antibody conjugated to peroxidase. Densitometry analysis was done using ImageJ (NIH).

Cytometric bead array (CBA)

Supernatants of cells cultured for 48 h were collected and the CBA kits (all from BD Biosciences) were used for determination of the amount of murine IL1α (560157), murine Cxcl1 (558340), and human IL1α (560153) according to manufacturer´s instructions.

Flow cytometry analysis

The following antibodies were used for staining: PE antimouse CD54 (116107, Biolegend), PE antimouse CD137 (106106, Biolegend), and PE Syrian Hamster IgG Isotype Control (402008, Biolegend). For IκBα-miRFP703 reporter detection, cells were transfected with pIκBα-miRFP703 and pEGFP-C1 (GFP). The percentage of IκBα-miRFP703-positive cells was expressed from 5000 GFP-positive cells. Data were collected using a BD FACSVerse and analyzed by FlowJo v10.6.2.

Trans-endothelial migration (TEM) assay

TEM assay was performed as described previously [41].

Data-mining and correlation analysis

Derivation and RNA sequencing of 4T1 Mybhigh were described previously [19,42]. The expression levels of the NF-κB targets/regulators were clustered using FGCZ Heatmap tool (http://fgcz-shiny.uzh.ch). The RNAseq data are available in Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO, NCBI) under the accession number GSE104264 [19]. MYB and IL1A transcript levels were looked up in microarray expression datasets GSE14027 [43] and GSE14405 [44].

The Broad Institute CCLE (https://portals.broadinstitute.org/ccle) was used to correlate MYB and IL1A expression in human BC cell lines. ER expression was evaluated according to Jiang et al. [45] and Dai et al. [46]. Correlations between MYB expression and NF-κB activity were calculated in a panel of 33 BC cell lines from dataset GSE44552, subtyping were done according to the Yamaguchi et al. [47]. Pearson correlations were calculated with the GraphPad Prism v6.07.

To detect the over-representation of transcription binding sites (TFBS) for a set of coexpressed genes we used cREMaG database interface with default settings and 47 input genes deregulated in Mybhigh as identified previously [19].

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed with the GraphPad Prism v6.07. All data are presented as mean ±SD and were analyzed with unpaired T-test unless stated otherwise.

Results

c-Myb reduces activity of the NF-κB pathway

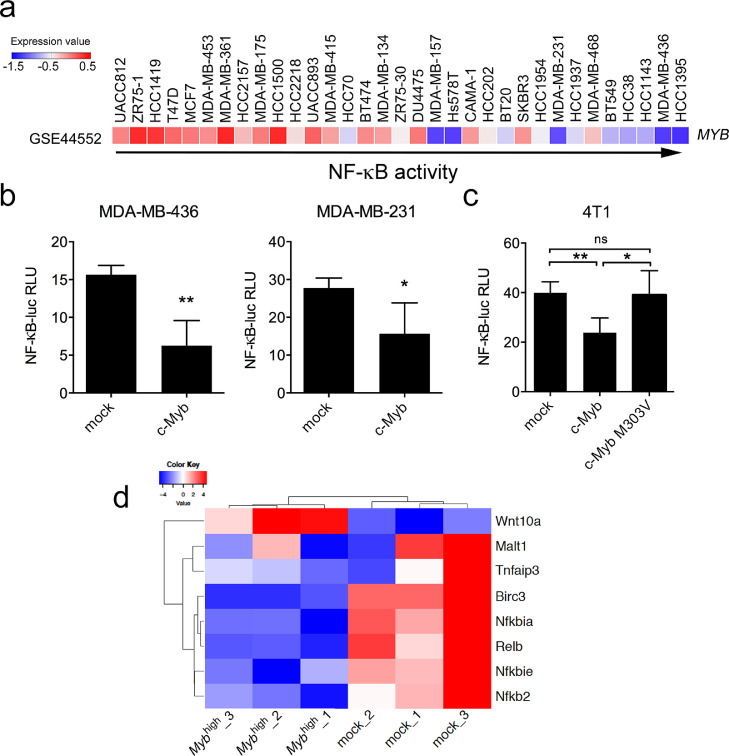

Analysis of expression dataset (GSE44552) showed that MYB expression and constitutive NF-κB activity inversely correlated in human BC cell lines (Fig. 1a). Noting that c-Myb is downstream of the ER signaling in BC [24], we split the cell lines into the ER-positive (specifically luminal) and ER-negative (basal) subtypes. The inverse correlation between MYB expression and NF-κB activity was significant within the cell lines of luminal subtype, and the same trend was apparent for basal subtype, suggesting that c-Myb may provide an ER-independent effect (Fig. S1a). We have previously identified the c-Myb-inflammatory signature consisting of immune response genes that are repressed by c-Myb in ER-negative BCs [19]. In silico analysis using cREMaG database showed that the most over-represented transcription factor-binding sites within the promoters of the c-Myb-inflammatory signature genes are the NF-κB family motifs (Table S4). Therefore, we hypothesized that c-Myb may attenuate the NF-κB signaling.

Fig. 1.

c-Myb overexpression interferes with NF-κB signaling in breast cancer cells lines. (A) Heatmap of MYB mRNA expression in human breast cancer cell lines aligned according to their constitutive NF-κB activity as measured in [47]. (B) Transactivation of NF-κB-luc reporter in human MDA-MB-436 and MDA-MB-231 cells transiently overexpressing MYB, luciferase activity was normalized to β-galactosidase activity and expressed as relative light units. Average normalized relative light units (RLU) from 3 independent experiments are shown, comparison to mock transfected cells. (C) Transactivation of NF-κB-luc reporter in murine 4T1 cells transiently overexpressing wt Myb and Myb harboring M303V amino acid substitution. Luciferase activity was normalized to the protein concentration. Average normalized relative light units (RLU) from 3 independent experiments are shown in comparison to mock-transfected cells. (D) NF-κB target genes [64] that are differentially expressed in 4T1 Mybhigh cells compared to mock control cells, heatmap of RNA sequencing data. Significant differences (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01) are indicated.

To test the effect of c-Myb on activity of NF-κB in a cellular model, we performed luciferase assays using the NF-κB reporter plasmid (NF-κB-luc) containing the firefly luciferase gene under control of the NF-κB response elements. The NF-κB-luc vector was used with the MYB-coding or control plasmids for transient transfection of human MDA-MB-231 and MDA-MB-436 cells. In both cell lines, the NF-κB transactivation activity significantly decreased in the presence of c-Myb (Fig. 1b). We repeated this experiment with a vector coding for a mutant c-Myb harboring an amino acid substitution in its transactivation domain (M303V) that abrogates transcriptional activation/repression of the c-Myb target genes [48,49]. The NF-κB-luc plasmid was used together with vectors coding for wild-type (wt) c-Myb, M303V c-Myb, or mock control for transfection of mouse 4T1 and E0771.LMB cell lines. The NF-κB transactivation activity significantly decreased in the presence of wild-type c-Myb, but not M303V c-Myb (Fig. 1c, S1b), suggesting that suppression of NF-κB by c-Myb required trans-activation/repression of either directly NF-κB family member(s) or NF-κB pathway regulator(s).

To confirm our hypothesis that c-Myb suppresses activity of NF-κB, we analyzed expression levels of the NF-κB family members and targets in unstimulated 4T1 and E0771.LMB cells exhibiting high ectopic c-Myb expression (Mybhigh cells) [19]. A significant decrease of several of these genes in Mybhigh cells (Fig 1d, S1c) support the hypothesis that c-Myb has a negative impact on the activity of the NF-κB pathway.

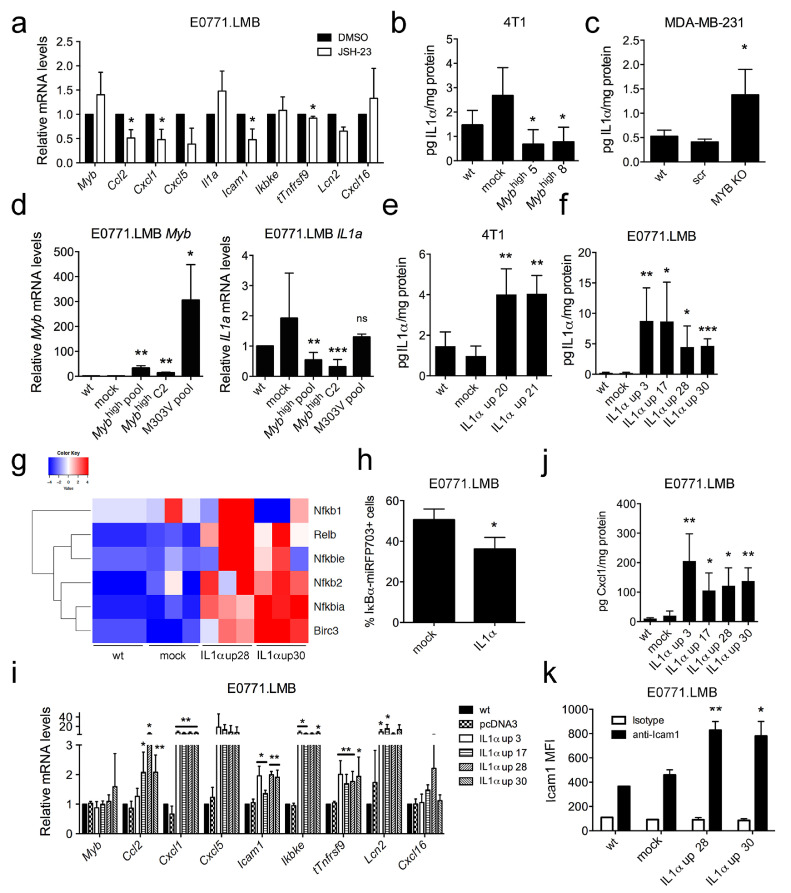

IL1α expression is reduced by c-Myb but not by the NF-κB inhibitor JSH-23

The link between NF-κB signaling and c-Myb expression has been described for colorectal cancer, where the NF-κB proteins trigger transcription of Myb [50]. To test whether expression of Myb itself could be stimulated by NF-κB in our experimental settings, we treated 4T1 cells with the NF-κB-specific inhibitor JSH-23 [51]. Inhibition of NF-κB did not affect the Myb transcription but resulted in attenuation of the inflammatory signature gene expression (Fig. 2a), thereby resembling an effect of c-Myb overexpression [19]. Since expression of some genes from the signature (Il1a, Ikbke, and Cxcl16) were not altered by the NF-kB inhibition, these genes may act upstream of NF-κB.

Fig. 2.

IL1α is downregulated by c-Myb and its overexpression inversely impacts the inflammatory signature and NF-κB pathway. (A) mRNA levels of indicated genes in JSH-23-treated (20 µM, 24 h) E0771.LMB cells were normalized to Gapdh, relative fold change to DMSO-treated cells is shown for each gene. An average of 3 independent experiments is shown. Secreted IL1α protein levels in 4T1 cells overexpressing wt c-Myb (Mybhigh 5 and 8) (B) and MDA-MB-231c-Myb knock-out cells (MYB KO) (C) as measured by Cytometric Bead Array (CBA). An average of 3 independent experiments is shown, comparison to mock-transfected and scrambled-transfected cells, respectively (D) Myb (left) and Il1a (right) mRNA expression in E0771.LMB cells overexpressing wt c-Myb (Mybhigh pool, Mybhigh C2) and M303V mutant c-Myb (M303V pool). Data were normalized to Gapdh, fold change values relative to wt cells from 3 independent experiments are shown, comparison to mock-transfected cells. Clones overexpressing mouse Il1a (IL1α up) were derived from 4T1 (E) and E0771.LMB (F) cells. Secreted IL1α protein levels were measured in 3 biological replicates by CBA, higher IL1α concentrations are compared to mock-transfected cells. (G) Expression of selected NF-κB family members/targets in E0771.LMB IL1α up cells as determined by qPCR, normalized to Gapdh and shown in triplicates as a heatmap. (H) IκBα levels in E0771.LMB cells cotransfected with pcDNA3.1 (mock), resp. pcDNA3.IL1a (IL1α), and pIκBα-miRFP703 vectors. Graph shows average frequency of miRFP703+ cells from 3 independent experiments. (I) mRNA levels of indicated genes in IL1α up E0771.LMB cells as determined by qPCR were normalized to Gapdh and expressed as fold change to wt cells. Significance calculated from 3 independent experiment is shown, comparison to mock-transfected cells. Proteins levels of Cxcl1 and Icam1 were determined in E0771.LMB IL1α up cells by CBA (J) and flow cytometry, respectively (K). Significant differences (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001) are indicated.

IL1α is a known activator of the NF-κB pathway [52] and has been described as one of the most abundant molecules in triple-negative BC cells upon NF-κB stimulation [53]. Given that transcription of Il1a is significantly reduced in 4T1 Mybhigh cells [19], we investigated the relationship between c-Myb and IL1α. Lower levels of IL1α in the conditioned medium of 4T1 Mybhigh cells were detected using flow-cytometric bead array (CBA) (Fig. 2b). Vice versa, MDA-MB-231 c-Myb knock-out cells showed an increase in IL1α production (Fig. 2c). This reverse relationship between Myb and Il1a expression was also detected in E0771.LMB cells using qPCR (Fig. 2d).

Overexpression of IL1α stimulates the NF-κB pathway and the inflammatory signature

Next, we prepared several independent clones of 4T1 and E0771.LMB stably overexpressing IL1α (IL1α up, Fig. 2e-f). We detected significant increases in the transcription of the NF-κB genes Nfkb2, Nfkbia, Birc3 in E0771.LMB IL1α up clones compared to the mock control (Fig. 2g). To verify IL1α as an NF-κB activator, we used a reporter vector coding for the NF-κB inhibitor (IκBα) fused with miRFP703 fluorescent tag for cotransfection of 4T1 cells with pcDNA3.1 (mock) and pcDNA3.Il1a (IL1α). The increase of NF-κB activity was accompanied by a rapid degradation of IκBα [54]. Thus, the IκBα-miRFP703+ cells were considered as NF-κB inactive, while the IκBα-miRFP703− cells represented the NF-κB-activated population. To exclude nontransfected cells from the analysis, we cotransfected a GFP-coding vector and analyzed only the GFP+ cells. The significant decrease of GFP+ IκBα-miRFP703+ cells in the presence of IL1α showed that IL1α activated the NF-κB pathway, as hypothesized (Fig. 2h). To test, whether exogenous IL1α can also stimulate NF-κB, we determined transactivation of the NF-κB-luc reporter in E0771.LMB cells treated with recombinant IL1α. The NF-κB-luc activity was induced upon IL1α treatment in a dose-dependent manner from 0.1 ng/mL and peaked at 1 ng/mL (Fig. S2a).

Analysis of the effect of IL1α overexpression on transcription of the c-Myb-inflammatory signature revealed a significant increase in the amount of all the transcripts in E0771.LMB IL1α up cells, except for Cxcl16 (Fig. 2i). Flow cytometric analysis confirmed the significant increase of Cxcl1 (Fig. 2j) as well as Icam1 and Tnfrsf9 protein production by E0771.LMB IL1α up cells (Fig. 2k, S2b). Similarly, elevated expression of the signature genes Cxcl1, Cxcl5, Icam1, and Lcn2 was found in 4T1 IL1α up cells by qPCR (Fig. S2c). Elevated secretion of Cxcl1 was confirmed in conditioned media of 4T1 IL1α up cells (Fig. S2d). In contrast, expression of nearly all signature genes declined in 4T1 IL1α KO cells (Fig. S2e-f). To further confirm the effect of human IL1α on expression of the signature genes, we prepared MDA-MB-231 cells overexpressing human IL1α (Fig. S2g). We found CCL2, CXCL1, CXCL2, ICAM1, IKBKE, TNFRSF9 transcripts to be elevated (Fig. S2h). Altogether these results indicate that human and murine IL1α produced by BC cells can be involved in autocrine signaling, leading to elevated expression of a subset of the genes from the NF-κB pathway and its targets.

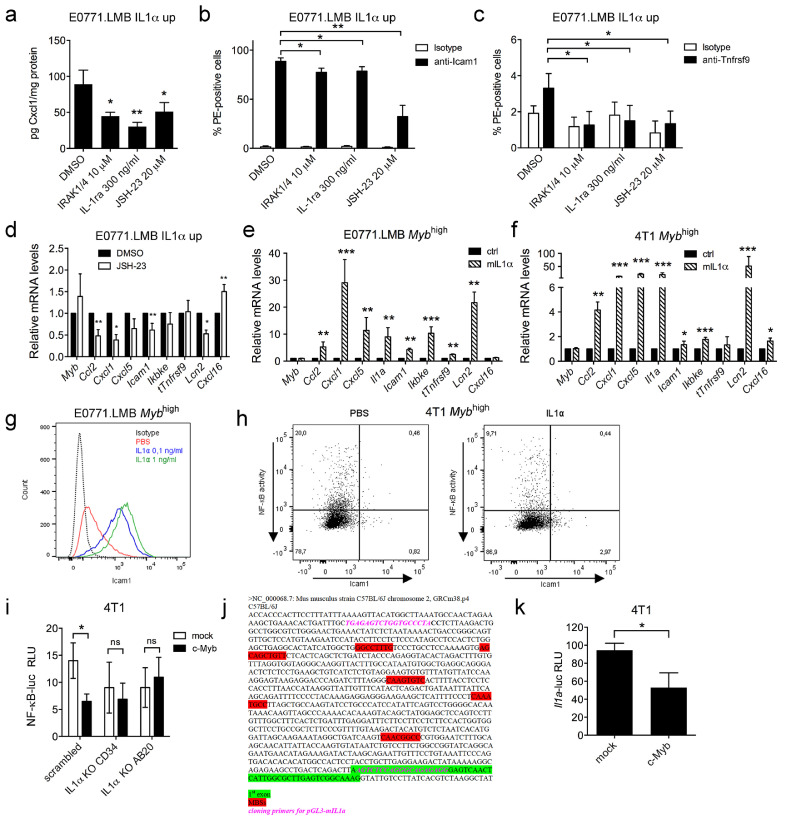

Suppression of the NF-κB inflammatory circuit by c-Myb depends on IL1α

To verify that IL1α stimulates expression of the c-Myb inflammatory genes through activation of NF-κB signaling, we blocked IL1α and NF-κB using specific inhibitors. We used either IRAK1/4 (interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase 1 and 4) inhibitor or IL-1ra (interleukin 1 receptor antagonist) to inhibit IL1α activity and JSH-23 to inhibit NF-κB. All inhibitors significantly reduced the secretion of Cxcl1 (Fig. 3a), and surface levels of Icam1 and Tnfrsf9 in E0771.LMB IL1α up cells (Fig. 3b-c). In addition, inhibition of NF-κB resulted in a significant decline in the expression of the majority of the c-Myb-inflammatory signature genes in E0771.LMB IL1α up cells as determined by qPCR (Fig. 3d). Altogether, these data demonstrate that IL1α-controlled expression of the c-Myb-inflammatory signature genes is sensitive to NF-κB inhibition.

Fig. 3.

Suppression of NF-κB and the inflammatory circuit by c-Myb depends on IL1α. IL1α and NF-κB inhibition in IL1α up cells reversed the up-regulation of inflammatory genes: Cxcl1 (A), Icam1 (B), Tnfrsf9 (C) upon treatment with IRAK1/4, IL1-Ra and JSH-23. An average from 3 independent experiments is shown. Indicated concentration of inhibitors were added to E0771.LMB IL1α up 28 cells (IL1α up 28), after 24 h Cxcl1 concentrations were determined by CBA and Icam1 and Tnfrsf9 surface expression was measured by flow cytometry and expressed as frequency of positive cells, comparison to vehicle (DMSO)-treated cells. (D) qPCR detection of signature genes in JSH-23-treated (10 µM, 24 h) E0771.LMB IL1α up cells (IL1α up 28). Values were normalized to Gapdh and expressed as a fold change of DMSO-treated cells. An average of 3 independent experiments is shown. E0771.LMB (E) and 4T1 (F) cells overexpressing wt c-Myb (E0071.LMB Mybhigh C2, 4T1 Mybhigh 7) supplemented with recombinant mIL1α (1 ng/mL, 24 h) induces the expression of the signature genes. mRNA levels of indicated genes are determined by qPCR relative to vehicle-treated cells (ctrl) and normalized to Gapdh. An average of 3 independent experiments is shown. (G) Dose-dependent increase in surface Icam1 upon IL1α stimulation (24 h) of E0771.LMB cells overexpressing wt c-Myb (Mybhigh C2) as determined by flow cytometry. (H) Surface Icam1 expression is restored by recombinant IL1α in 4T1 cells overexpressing wt c-Myb (Mybhigh 7) concomitant with loss of IκBα-miRFP703. Mybhigh 7 cells cotransfected with pEGFP-C1 (GFP) and pIκBα−miRFP703 were treated with 1 ng/mL IL1α for 24h, Icam1 was stained and determined in GFP+ cells by flow-cytometry in parallel with IκBα levels. (I) Two 4T1 IL1α KO clones (IL1α KO CD34 and AB20), and scrambled control cells, were cotransfected with pcDNA3.c-Myb (c-Myb)/pcDNA3 (mock) and the NF-κB reporter. Luciferase activity (RLU) was measured 18 h later and normalized to β-galactosidase activity. An average of 3 independent experiments is shown. (J) Putative MYB-binding sites (MBSs, red) in the murine Il1a promoter sequence (980 bp upstream TSS, green). Primer pair used for cloning Il1a-luc reporter construct is indicated in pink. (K) Transactivation assay using 4T1 cells cotransfected with c-Myb or empty vector and Il1a-luc reporter. Il1a promoter activity is expressed as luciferase relative light units normalized to total protein levels. An average of 3 independent experiments is shown. Significant differences (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001) are indicated.

To test whether c-Myb inhibits the inflammatory signature by limiting the IL1α expression, we treated Mybhigh cells with recombinant murine IL1α and analyzed the expression of the signature genes. IL1α derepressed the expression of the signature genes in both E0771.LMB (Fig. 3e) and 4T1 (Fig. 3f) Mybhigh cell lines. Of note, Tnfrsf9 expression was induced only in E0771.LMB and Cxcl16 only in 4T1 cells. On protein level, treatment of E0771.LMB Mybhigh cells with IL1α increased the production of Icam1 (Fig. 3g, S3a) and Cxcl1 (Fig. S3b) in a dose-dependent manner. To verify that the effect of IL1α on gene expression is associated with activation of NF-κB signaling, we took advantage of the fluorescent IκBα-miRFP703 reporter and simultaneous staining of the Icam1 protein. After IL1α stimulation, we detected a decrease of GFP+ IκBα-miRFP703+ cells, proving the NF-κB activation in 4T1 Mybhigh cells (Fig. 3h, S3c). IL1α stimulation led to a higher Icam1 expression, importantly, Icam1+ cells were predominantly IκBα-miRFP703 negative (Fig. S3d), confirming that Icam1 expression induced by IL1α was dependent on NF-κB signaling.

To validate the proposed c-Myb-IL1α-NF-κB axis, we determined the effect of c-Myb on the transactivation of the NF-κB-luc reporter in 4T1 cells deficient in IL1α expression (IL1α KO cells). Transactivation by NF-κB was suppressed upon cotransfection with the NF-κB-luc reporter and a vector coding for c-Myb in control (scrambled) cells, but not in IL1α KO cells (Fig. 3i). We analyzed the murine Il1a promoter sequence and found 5 potential Myb-binding sites (Fig. 3j). To test, whether c-Myb directly modulates Il1a expression, we constructed a luciferase reporter vector containing the murine Il1a promoter sequence (Il1a-luc). In 4T1 cells, cotransfected with this Il1a-luc reporter and the c-Myb-expressing plasmid, we detected a significant decrease of Il1a promoter activity (Fig. 3k). We concluded that transactivation of the Il1a promoter is negatively regulated by c-Myb.

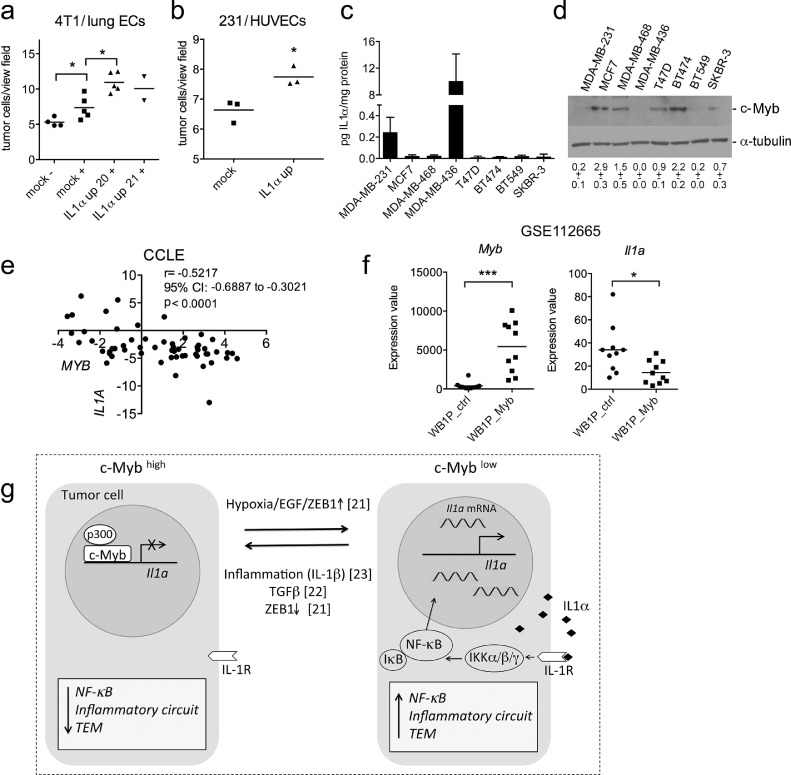

IL1α facilitates TEM and inversely correlates with c-Myb in BC cell lines

To prove the functional significance of c-Myb-IL1α-NF-κB signaling, we inspected the TEM ability of IL1α up cells. We have shown previously that c-Myb has a negative impact on TEM [19]. Here, we found that ectopic expression of IL1α in 4T1 cells enhanced transmigration capacity through primary endothelial cells (Fig. 4a, S4a). Similar results were obtained with MDA-MD-231 IL1α up cells transmigrating through a layer of HUVEC cells (Fig. 4b), underlining the opposite role of IL1α to c-Myb in sustaining transmigration capability in BC cells.

Fig. 4.

IL1A facilitates transendothelial migration and inversely correlates with MYB in BC cells. (A) Monocyte-assisted TEM of 4T1 cells across primary lung ECs in vitro is enhanced by ectopic IL1α (IL1α up clones 20 and 21). –/+ bone marrow derived CD115+ monocytes. (B) Human IL1A overexpressed by MDA-MB-231 potentiates TEM across HUVECs in vitro. (C) Concentrations of IL1α protein in CM from a panel of human BC cell lines as measured by CBA. Average values of 3 independent experiments are shown. (D) Endogenous c-Myb levels in indicated BC cell lines as determined by immunoblotting, α-tubulin was used as a loading control. (E) Inverse correlation between IL1A and MYB mRNA levels as determined by RNAseq in BC cell lines in a Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE). r = Pearson correlation coefficient, CI = confidence interval. (F) Myb and Il1a transcript levels in tumors developed in genetically engineered mouse models of BC overexpressing Myb (WapCre; Brca1F/F; Trp53F/F; Col1a1invCAG-Myb2-IRES-Luc/+ mice, “WB1P_Myb”) and controls (WapCre; Brca1F/F; Trp53F/F mice, “WB1P_ctrl”) as determined by RNAseq involved in GSE112665 [56]. (G) Proposed role of c-Myb protein in the regulation of NF-κB activity in BC. High level of c-Myb repress IL1α expression which in turn leads to a decline in NF-κB activity and TEM ability of the BC cells. Significant differences (*P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001) are indicated.

In order to investigate the expression pattern of c-Myb and IL1α, we analyzed the level of these proteins in several human BC cell lines. We determined the amount of secreted IL1α in the conditioned medium using CBA (Fig. 4c) and the amount of c-Myb in the cell lysates by immunoblotting (Fig. 4d). The highest level of secreted IL1α correlated with almost no detectable expression of c-Myb in MDA-MB-436 and MDA-MB-231 cells. In contrast, cells with strong c-Myb expression (MCF7, BT-474, MDA-MD-468, and T47D) secreted barely detectable IL1α. This corresponds with levels of MYB and IL1A in RNAseq data of the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE), showing a strong negative correlation between these 2 genes (Fig. 4e, S4b). After splitting the lines into ER-negative and ER-positive subgroups (Fig. S4c), the inverse correlation remained only in the ER-negative subgroup. Although the ER-positive subgroup comprises lower number of samples, further variables, such as low IL1A expression in the ER-positive cell lines, may contribute to this outcome.

Recently, ectopic c-Myb expression was induced in a genetically engineered mouse model (GEMM) of spontaneous basal-like BC. In WB1P_Myb (WapCre;Brca1F/F; Trp53F/F;Col1a1invCAG-Myb2-IRES-Luc/+) mice, the mammary-specific expression of Cre is driven by whey acidic protein (Wap) and induces mammary-specific inactivation of Brca1 and Trp53, concomitant with the overexpression of Myb [55,56]. Spontaneous mammary tumors were analyzed by RNA-sequencing [56] and showed a significant downregulation of Il1a expression in the WB1P_Myb mice compared to WB1P control mice (WapCre;Brca1F/F; Trp53F/F) (Fig. 4f). This further supports our results of c-Myb directed inhibition of Il1a. Together, we showed an inverse pattern of c-Myb and IL1α expression in BC cells, which may reflect their opposing roles in the metastatic capability of BC cells (Fig. 4g).

Discussion

Inspection of the MYB expression across BC cell lines revealed that high MYB level correlated with diminished constitutive NF-κB activity. Since the decrease of NF-κB activity is linked to ER signaling [57] and c-Myb expression can be under the control of ER in BC [14], we selected several ER-negative BC cell lines for delineating the proposed role of c-Myb in the NF-κB pathway. To verify the potential inhibitory effect of c-Myb, we used human MDA-MB-231 and MDA-MB-436 cells with high constitutive NF-κB activity [47]. c-Myb decreased the activity of NF-κB in both cell lines, in addition, similar results were obtained from murine 4T1 and E0771.LMB cells. The M303V variant of c-Myb, defective in the control of target genes transcription [48], had no effect on transactivation by NF-κB, indicating an indirect suppression of the NF-κB pathway. M303V c-Myb is unable to interact with the CBP/p300 coactivator, resulting in the abrogation of c-Myb-mediated transactivation, and likewise repression of the c-Myb target genes [49,58]. Although the requirement of p300 for the c-Myb-directed transcriptional repression is not fully understood, the outcome of c-Myb/p300 interaction at regulatory elements can be gene-specific [59]. Depending on the MBS position, it can activate transcription of noncoding RNA molecules, thus leading to post-transcriptional repression [48]. Additional regulatory molecules may be essential to facilitate access of the p300 active site [60] or other interacting partners may be involved [61]. Overall, the effect of p300 recruitment to the gene regulatory elements appears to be context-dependent [62,63]. About half of its target genes are estimated to be repressed by c-Myb [48]. We described earlier that c-Myb acts as a potent inhibitor of a specific subset of genes in BC sharing the NF-κB-responsive elements in their regulatory regions [19]. Here, the crosstalk between c-Myb and NF-κB was further supported by decreased transcription of several genes of the previously published NF-κB signature [64] in cells with elevated c-Myb expression.

We assume that NF-κB signaling in ER-negative BC cells can be attenuated by c-Myb-governed inhibition of IL1α expression. While c-Myb significantly decreased transactivation activity of NF-κB in IL1α producing cells, it had no impact on transactivation activity of NF-κB in IL1α-knock-out cells. IL1α is known as an NF-κB signaling activator as well as a direct target, capable of inducing a positive feedback loop [52]. We confirmed that IL1α efficiently activates the NF-κB pathway and overrules the c-Myb inhibitory effect on the expression of the inflammatory signature genes. Previous studies provide evidence of elevated IL1α autocrine and paracrine production by cancer cells of various origins, including breast cancer cells [65,66]. IL1α expression is predominantly found in ER-negative BC [67,68]. There are studies showing an estradiol-mediated decrease of IL1α production by macrophages [69,70]. Therefore, we can speculate that c-Myb works in cooperation with ER in ER-positive BC, importantly, we showed that c-Myb suppression of IL1α occurs in the absence of ER signaling. In a panel of human BC cell lines, we demonstrated an inverse correlation of c-Myb and IL1α basal protein levels. CCLE showed a strong inverse correlation between MYB and IL1A transcript levels only in a subgroup of the ER-negative cell lines, highlighting the significance of c-Myb as an inhibitor of IL1α in the absence of ER. We showed that upon overexpression of c-Myb, the ER-negative BC cells strongly decreased the production of IL1α and contrariwise, c-Myb knock-out cells showed increased production of IL1α. c-Myb significantly decreased transactivation of the luciferase gene reporter equipped with the Il1a promoter sequence. In line with our hypothesis, IL1A has been described as one of the genes repressed by c-Myb in the human monocytic cell line THP-1 [71]. In addition, affinity of c-Myb to the IL1A promoter region has been observed by ChIP in ERMYB myeloid progenitor cells [48] and BC cell line MCF7 [72]. Together, we propose a mechanism of NF-κB signaling inhibition in ER-negative BC cells determined by the inhibition of IL1α expression governed by c-Myb.

Numerous studies declare importance of the NF-κB pathway in promotion of the metastatic capability of BC cells [73,74]. Similarly, most reports declare IL1α expression in highly metastatic BC cells [35,36]. IL1α belongs to the top upregulated secreted proteins in the metastatic triple negative BC cells compared with the nonmetastatic counterpart [37]. In line with this, metastatic MDA-MB-436 and MDA-MB-231 cells were the most potent producers of secreted IL1α. Moreover, overexpression of IL1α provided 4T1, E0771.LMB as well as MDA-MB-231 cells with increased transmigration capacity. Inflammatory cytokines are essential for endothelial activation and tumor cell extravasation [75,76]. c-Myb has a negative impact on the TEM by limiting CCL2 production in BC cells [19]. The release of Ccl2 transcription in Mybhigh cells by IL1α and increased Ccl2 expression in IL1α up cells further underline the opposite effect of IL1α and c-Myb on TEM capability of BC cells. Furthermore, IL1α secreted by BC cells induces the production of thymic stromal lymphopoietin by myeloid cells that serve as a crucial survival factor for cancer cells in the primary lesion and on the site of metastasis, specifically in the lungs [36]. High IL1α levels are connected with shorter distant metastasis-free survival in BC patients. Vice versa, IL1α knock-out dramatically reduces tumorigenicity of human BC cells HCC1954 [34]. On the contrary, IL1α acts as a tumor suppressor in a PyMT-driven tumorigenesis model [77]. It is noteworthy that in this PyMT model PyMT/IL1α−/− mice have been used, whereas, in the previously mentioned study, IL1α has been selectively knocked-out in HCC1954 cancer cells. This implies that the impact of the IL1α cytokine may depend on the source of its production or its local concentration in the tumor microenvironment.

Importance of the genetic makeup of breast tumors in dictating prometastatic systemic inflammation has been demonstrated by comparison of immune landscapes of series of GEMMs of BC [56]. Deeper understanding of the interactions between cancer cell-intrinsic genetic events and the immune landscape is required to design personalized immune interventions for cancer patients [78]. In this study, we unraveled a novel c-Myb-IL1α-NF-κB signaling axis that takes place in tumor cells and alters an outward inflammatory network that likely modulates heterotypic cell interactions within the tumor/metastatic microenvironment and dictates the outcome of tumor-stromal cell encounter during dissemination. Overall, we showed that high c-Myb restrains the tumor-driven inflammatory circuit and NF-kB pathway in ER-negative BC cells by transcriptional control over IL1α cytokine, thereby prevents efficient transmigration of tumor cells. While in primary tumor c-Myb may be responsible for diverse functions, its anti-inflammatory action may affect circulating disseminated tumor cells and forestall metastatic cascade. Preclinical studies are needed to validate these findings and set the principles for clinical usage.

Authors’ contribution

Dúcka Monika – Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft.

Kučeríková Martina - Data curation.

Trčka Filip - Data curation, Methodology.

Červinka Jakub - Data curation.

Biglieri Elisabetta - Data curation.

Šmarda Jan - Writing – review and editing, Resources.

Borsig Lubor - Writing – review and editing, Resources.

Beneš Petr - Writing – review and editing, Resources.

Knopfová Lucia – Conceptualization, Supervision, Visualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition.

Funding

This work was funded by Czech Science Foundation grant 17-08985Y, by Ministry of Health of the Czech Republic grant NV18-07-00073 and supported by the European Regional Development Fund - Project ENOCH (No. CZ.02.1.01/0.0/16_019/0000868).

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Merel van Gogh for proofreading the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.neo.2021.01.002.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Tsang JYS, Tse GM. Molecular classification of breast cancer. Adv Anat Pathol. 2020;27:27–35. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0000000000000232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones SE. Metastatic breast cancer: the treatment challenge. Clin Breast Cancer. 2008;8:224–233. doi: 10.3816/CBC.2008.n.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mariotto AB, Etzioni R, Hurlbert M, Penberthy L, Mayer M. Estimation of the number of women living with metastatic breast cancer in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2017;26:809–815. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-16-0889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ramsay RG, Gonda TJ. MYB function in normal and cancer cells. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:523–534. doi: 10.1038/nrc2439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calabretta B, Sims RB, Valtieri M, Caracciolo D, Szczylik C, Venturelli D, Ratajczak M, Beran M, Gewirtz AM. Normal and leukemic hematopoietic cells manifest differential sensitivity to inhibitory effects of c-myb antisense oligodeoxynucleotides: an in vitro study relevant to bone marrow purging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:2351–2355. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.6.2351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Waldron T, De Dominici M, Soliera AR, Audia A, Iacobucci I, Lonetti A, Martinelli G, Zhang Y, Martinez R, Hyslop T. c-Myb and its target BMI1 are required for p190BCR/ABL leukemogenesis in mouse and human cells. Leukemia. 2012;26:644–653. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tichý M, Knopfová L, Jarkovský J, Pekarčíková L, Veverková L, Vlček P, Katolická J, Čapov I, Hermanová M, Šmarda J. Overexpression of c-Myb is associated with suppression of distant metastases in colorectal carcinoma. Tumor Biol. 2016;37:10723–10729. doi: 10.1007/s13277-016-4956-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tichý M, Knopfová L, Jarkovský J, Vlček P, Katolická J, Čapov I, Hermanová M, Šmarda J, Beneš P. High c-Myb expression associates with good prognosis in colorectal carcinoma. J Cancer. 2019;10:1393–1397. doi: 10.7150/jca.29530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu LYD, Chang LY, Kuo WH, Hwa HL, Chang KJ, Hsieh FJ. A supervised network analysis on gene expression profiles of breast tumors predicts a 41-gene prognostic signature of the transcription factor MYB across molecular subtypes. Comput Math Methods Med. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/813067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miao RY, Drabsch Y, Cross RS, Cheasley D, Carpinteri S, Pereira L, Malaterre J, Gonda TJ, Anderson RL, Ramsay RG. MYB is essential for mammary tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2011;71:7029–7037. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nicolau M, Levine AJ, Carlsson G. Topology based data analysis identifies a subgroup of breast cancers with a unique mutational profile and excellent survival. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:7265–7270. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102826108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thorner AR, Parker JS, Hoadley KA, Perou CM. Potential tumor suppressor role for the c-Myb oncogene in luminal breast cancer. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13073. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guérin M, Sheng ZM, Andrieu N, Riou G. Strong association between c-myb and oestrogen-receptor expression in human breast cancer. Oncogene. 1990;5:131–135. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2181374/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mitra P, Pereira LA, Drabsch Y, Ramsay RG, Gonda TJ. Estrogen receptor-α recruits P-TEFb to overcome transcriptional pausing in intron 1 of the MYB gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:5988–6000. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weide R, Feiten S, Friesenhahn V, Heymanns J, Kleboth K, Thomalla J, van Roye C, Köppler H. Metastatic breast cancer: prolongation of survival in routine care is restricted to hormone-receptor- and Her2-positive tumors. SpringerPlus. 2014;3:535. doi: 10.1186/2193-1801-3-535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mitra P. Transcription regulation of MYB: a potential and novel therapeutic target in cancer. Ann Transl Med. 2018;6:443. doi: 10.21037/atm.2018.09.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Drabsch Y, Robert RG, Gonda T J. MYB suppresses differentiation and apoptosis of human breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res. 2010;12:R55. doi: 10.1186/bcr2614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hodges LC, Cook JD, Lobenhofer EK, Li L, Bennett L, Bushel PR, Aldaz CM, Afshari CA, Walker CL. Tamoxifen functions as a molecular agonist inducing cell cycle-associated genes in breast cancer cells. Mol Cancer Res. 2003;1:300–311. https://mcr.aacrjournals.org/content/1/4/300 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knopfová L, Biglieri E, Volodko N, Masařík M, Hermanová M, Glaus Garzón JF, Dúcka M, Kučírková T, Souček K, Šmarda J. Transcription factor c-Myb inhibits breast cancer lung metastasis by suppression of tumor cell seeding. Oncogene. 2018;37:1020–1030. doi: 10.1038/onc.2017.392. [GSE104264] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kauraniemi P, Hedenfalk I, Persson K, Duggan DJ, Tanner M, Johannsson O, Olsson H, Trent JM, Isola J, Borg A. MYB oncogene amplification in hereditary BRCA1 breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2000;60:5323–5328. https://cancerres.aacrjournals.org/content/60/19/5323 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hugo HJ, Pereira L, Suryadinata R, Drabsch Y, Gonda TJ, Gunasinghe NPAD, Pinto C, Soo ETL, van Denderen BJW, Hill P. Direct repression of MYB by ZEB1 suppresses proliferation and epithelial gene expression during epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition of breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res. 2013;15:R113. doi: 10.1186/bcr3580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cesi V, Casciati A, Sesti F, Tanno B, Calabretta B, Raschella G. TGFβ-induced c-Myb affects the expression of EMT-associated genes and promotes invasion of ER+ breast cancer cells. Cell Cycle. 2011;10(23):4149–4161. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.23.18346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li Y, Jin K, Van Pelt GW, Van Dam H, Yu X, Mesker WE, ten Dijke P, Zhou F, Zhang L. c-Myb enhances breast cancer invasion and metastasis through the Wnt/β-catenin/Axin2 pathway. Cancer Res. 2016;76:3364–3375. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-2302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Drabsch Y, Hugo H, Zhang R, Dowhan DH, Miao YR, Gewirtz AM, Barry SC, Ramsay RG, Gonda TJ. Mechanism of and requirement for estrogen-regulated MYB expression in estrogen-receptor-positive breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:13762–13767. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700104104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tanno B, Sesti F, Cesi V, Bossi G, Ferrari-Amorotti G, Bussolari R, Tirindelli D, Calabretta B, Raschellà G. Expression of Slug is regulated by c-Myb and is required for invasion and bone marrow homing of cancer cells of different origin. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:29434–29445. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.089045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim D, You E, Jeong J, Ko P, Kim J-W, Rhee S. DDR2 controls the epithelial-mesenchymal-transition-related gene expression via c-Myb acetylation upon matrix stiffening. Sci Rep. 2017;7:6847. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-07126-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Staudt LM. Oncogenic activation of NF-κB. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000109. https://dx.doi.org/10.1101%2Fcshperspect.a000109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bennett L, Quinn J, McCall P, Mallon EA, Horgan PG, McMillan DC, Paul A, Edwards J. High IKKα expression is associated with reduced time to recurrence and cancer specific survival in oestrogen receptor (ER)-positive breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 2017;140:1633–1644. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sirinian C, Papanastasiou AD, Schizas M, Spella M, Stathopoulos GT, Repanti M, Zarkadis IK, King TA, Kalofonos HP. RANK-c attenuates aggressive properties of ER-negative breast cancer by inhibiting NF-κB activation and EGFR signaling. Oncogene. 2018;37:5101–5114. doi: 10.1038/s41388-018-0324-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Espinoza-Sánchez NA, Győrffy B, Fuentes-Pananá EM, Götte M. Differential impact of classical and non-canonical NF-κB pathway-related gene expression on the survival of breast cancer patients. J Cancer. 2019;10:5191–5211. doi: 10.7150/jca.34302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karin M, Cao Y, Greten FR, Li ZW. NF-κB in cancer: from innocent bystander to major culprit. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:301–310. doi: 10.1038/nrc780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Malik A, Kanneganti T-D. Function and regulation of IL-1α in inflammatory diseases and cancer. Immunol Rev. 2018;281:124–137. doi: 10.1111/imr.12615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weber A, Wasiliew P, Kracht M. Interleukin-1 (IL-1) pathway. Sci Signal. 2010;3 doi: 10.1126/scisignal.3105cm1. cm1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu S, Lee JS, Jie C, Park MH, Iwakura Y, Patel Y, Soni M, Reisman D, Chen H. HER2 overexpression triggers an IL1α proinflammatory circuit to drive tumorigenesis and promote chemotherapy resistance. Cancer Res. 2018;78:2040–2051. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-2761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kumar S, Kishimoto H, Chua HL, Badve S, Miller KD, Bigsby RM, Nakshatri H. Interleukin-1α promotes tumor growth and cachexia in MCF-7 xenograft model of breast cancer. Am J Pathol. 2003;163:2531–2541. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63608-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kuan EL, Ziegler SF. A tumor–myeloid cell axis, mediated via the cytokines IL-1α and TSLP, promotes the progression of breast cancer. Nat Immunol. 2018;19:366–374. doi: 10.1038/s41590-018-0066-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roberti MP, Arriaga JM, Bianchini M, Quintá HR, Bravo AI, Levy EM, Mordoh J, Barrio MM. Protein expression changes during human triple negative breast cancer cell line progression to lymph node metastasis in a xenografted model in nude mice. Cancer Biol Ther. 2012;13:1123–1140. doi: 10.4161/cbt.21187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Holen I, Lefley DV, Francis SE, Rennicks S, Bradbury S, Coleman RE, Ottewell P. IL-1 drives breast cancer growth and bone metastasis in vivo. Oncotarget. 2016;7:75571–75584. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.12289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Johnstone CN, Smith YE, Cao Y, Burrows AD, Cross RSN, Ling X, Redvers RP, Doherty JP, Eckhardt BL, Natoli AL. Functional and molecular characterisation of EO771.LMB tumours, a new C57BL/6-mouse-derived model of spontaneously metastatic mammary cancer. Dis Model Mech. 2015;8:237–251. doi: 10.1242/dmm.017830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smarda J, Sugarman J, Glass C, Lipsick J. Retinoic acid receptor α suppresses transformation by v-myb. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:2474–2481. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.5.2474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wolf MJ, Hoos A, Bauer J, Boettcher S, Knust M, Weber A, Simonavicius N, Schneider C, Lang M, Stürzl M. Endothelial CCR2 signaling induced by colon carcinoma cells enables extravasation via the JAK2-Stat5 and p38MAPK pathway. Cancer Cell. 2012;22:91–105. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Volodko N, Gutor T, Petronchak O, Huley R, Dúcka M, Šmarda J, Borsig L, Beneš P, Knopfová L. Low infiltration of tumor-associated macrophages in high c-Myb-expressing breast tumors. Sci Rep. 2019;9:11634. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-48051-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Williams MR, Sakurai Y, Zughaier SM, Eskin SG, McIntire L V. Transmigration across activated endothelium induces transcriptional changes, inhibits apoptosis, and decreases antimicrobial protein expression in human monocytes. J Leukoc Biol. 2009;86:1331–1343. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0209062. GSE14027] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Drake JM, Strohbehn G, Bair TB, Moreland JG, Henry MD. ZEB1 enhances transendothelial migration and represses the epithelial phenotype of prostate cancer cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:2207–2217. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-10-1076. GSE14405] https://dx.doi.org/10.1091%2Fmbc.E08-10-1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jiang G, Zhang S, Yazdanparast A, Li M, Pawar AV, Liu Y, Inavolu SM, Cheng L. Comprehensive comparison of molecular portraits between cell lines and tumors in breast cancer. BMC Genomics. 2016;17:525. doi: 10.1186/s12864-016-2911-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dai X, Cheng H, Bai Z, Li J. Breast cancer cell line classification and its relevance with breast tumor subtyping. J Cancer. 2017;8:3131–3141. doi: 10.7150/jca.18457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yamaguchi N, Ito T, Azuma S, Ito E, Honma R, Yanagisawa Y, Nishikawa A, Kawamura M, Imai J, Watanabe S. Constitutive activation of nuclear factor-κB is preferentially involved in the proliferation of basal-like subtype breast cancer cell lines. Cancer Sci. 2009;100:1668–1674. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01228.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhao L, Glazov EA, Pattabiraman DR, Al-Owaidi F, Zhang P, Brown MA, Leo PJ, Gonda TJ. Integrated genome-wide chromatin occupancy and expression analyses identify key myeloid pro-differentiation transcription factors repressed by Myb. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:4664–4679. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sandberg ML, Sutton SE, Pletcher MT, Wiltshire T, Tarantino LM, Hogenesch JB, Cooke MP. c-Myb and p300 regulate hematopoietic stem cell proliferation and differentiation. Dev Cell. 2005;8:153–166. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pereira LA, Hugo HJ, Malaterre J, Huiling X, Sonza S, Cures A, Purcell DFJ, Ramsland PA, Gerondakis S, Gonda TJ. MYB elongation is regulated by the nucleic acid binding of NFkB p50 to the intronic stem-loop region. PLoS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shin HM, Kim MH, Kim BH, Jung SH, Kim YS, Park HJ, Hong JT, Min KR, Kim Y. Inhibitory action of novel aromatic diamine compound on lipopolysaccharide-induced nuclear translocation of NF-κB without affecting IκB degradation. FEBS Lett. 2004;571:50–54. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.06.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Niu J, Li Z, Peng B, Chiao PJ. Identification of an autoregulatory feedback pathway involving interleukin-1α in induction of constitutive NF-κB activation in pancreatic cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:16452–16462. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309789200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bauer D, Redmon N, Mazzio E, Soliman KF. Apigenin inhibits TNFα/IL-1α-induced CCL2 release through IKBK-epsilon signaling in MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells. PLoS One. 2017;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0175558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mathes E, O'Dea EL, Hoffmann A, Ghosh G. NF-κB dictates the degradation pathway of IκBα. EMBO J. 2008;27:1357–1367. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Annunziato S, de Ruiter JR, Henneman L, Brambillasca CS, Lutz C, Vaillant F, Ferrante F, Drenth AP, van der Burg E, Siteur B. Comparative oncogenomics identifies combinations of driver genes and drug targets in BRCA1-mutated breast cancer. Nat Commun. 2019;10:397. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-08301-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wellenstein MD, Coffelt SB, Duits DEM, van Miltenburg MH, Slagter M, de Rink I, Henneman L, Kas SM, Prekovic S, Hau CS. Loss of p53 triggers WNT-dependent systemic inflammation to drive breast cancer metastasis. Nature. 2019;572:538–542. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1450-6. [GSE112665] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sas L, Lardon F, Vermeulen PB, Hauspy J, Van Dam P, Pauwels P, Dirix LY, Van Laere SJ. The interaction between ER and NFкB in resistance to endocrine therapy. Breast Cancer Res. 2012;14:212. doi: 10.1186/bcr3196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dai P, Akimaru H, Tanaka Y, Hou D-X, Yasukawa T, Kanei-Ishii C, Takahashi T, Ishii S. CBP as a transcriptional coactivator of c-Myb. Genes Dev. 1996;10:528–540. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.5.528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kasper L H, Fukuyama T, Lerach S, Chang Y, Xu W, Wu S, Boyd K L, Brindle P K. Genetic interaction between mutations in c-Myb and the KIX domains of CBP and p300 affects multiple blood cell lineages and influences both gene activation and repression. PLoS One. 2013;8:e82684. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tafessu A, Banaszynski L A. Establishment and function of chromatin modification at enhancers: chromatin landscape at enhancers. Open Biol. 2020;10 doi: 10.1098/rsob.200255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Timblin GA, Xie L, Tjian R, Schlissel MS. Dual mechanism of Rag Gene repression by c-Myb during pre-B cell proliferation. Mol Cell Biol. 2017;37:e00437. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00437-16. 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ledsaak M, Bengtsen M, Molværsmyr AK, Fuglerud BM, Matre V, Eskeland R, Gabrielsen OS. PIAS1 binds p300 and behaves as a coactivator or corepressor of the transcription factor c-Myb dependent on SUMO-status. Biochim Biophys Acta - Gene Regul Mech. 2016;1859:705–718. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2016.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kasper LH, Qu C, Obenauer JC, McGoldrick DJ, Brindle PK. Genome-wide and single-cell analyses reveal a context dependent relationship between CBP recruitment and gene expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:11363–11382. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Annunziata CM, Davis RE, Demchenko Y, Bellamy W, Gabrea A, Zhan F, Lenz G, Hanamura I, Wright G, Xiao W. Frequent engagement of the classical and alternative NF-κB pathways by diverse genetic abnormalities in multiple myeloma. Cancer Cell. 2007;12:115–130. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Streicher KL, Willmarth NE, Garcia J, Boerner JL, Dewey TG, Ethier SP. Activation of a nuclear factor κB/interleukin-1 positive feedback loop by amphiregulin in human breast cancer cells. Mol Cancer Res. 2007;5:847–861. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-06-0427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tjomsland V, Spångeus A, Välilä J, Sandström P, Borch K, Druid H, Falkmer S, Falkmer U, Messmer D, Larsson M. Interleukin 1α sustains the expression of inflammatory factors in human pancreatic cancer microenvironment by targeting cancer-associated fibroblasts. Neoplasia. 2011;13:664–675. doi: 10.1593/neo.11332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bhat-Nakshatri P, Newton TR, Goulet RJ, Nakshatri H. NF-κB activation and interleukin 6 production in fibroblasts by estrogen receptor-negative breast cancer cell-derived interleukin 1α. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:6971–6976. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.6971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pantschenko AG, Pushkar I, Anderson KH, Wang Y, Miller LJ, Kurtzman SH, Barrows G, Kreutzer DL. The interleukin-1 family of cytokines and receptors in human breast cancer : Implications for tumor progression. Int J Oncol. 2003;23:269–284. doi: 10.3892/ijo.23.2.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Morishita M, Miyagi M, Iwamoto Y. Effects of sex hormones on production of interleukin-1 by human peripheral monocytes. J Periodontol. 1999;70:757–760. doi: 10.1902/jop.1999.70.7.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pfeilschifter J, Köditz R, Pfohl M, Schatz H. Changes in proinflammatory cytokine activity after menopause. Endocr Rev. 2002;23:90–119. doi: 10.1210/edrv.23.1.0456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.The FANTOM Consortium and the Riken Omics Science Center The transcriptional network that controls growth arrest and differentiation in a human myeloid leukemia cell line. Nat Genet. 2009;41:553–562. doi: 10.1038/ng.375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Quintana AM, Liu F, O'Rourke JP, Ness SA. Identification and regulation of c-Myb target genes in MCF-7 cells. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:30. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wu Y, Deng J, Rychahou PG, Qiu S, Evers BM, Zhou BP. Stabilization of snail by NF-kB is required for inflammation-induced cell migration and invasion. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:416–428. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Luo M, Hou L, Li J, Shao S, Huang S, Meng D, Liu L, Feng L, Xia P, Qin T, Zhao X. VEGF/NRP-1axis promotes progression of breast cancer via enhancement of epithelial-mesenchymal transition and activation of NF-κB and β-catenin. Cancer lett. 2016;373:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Häuselmann I, Roblek M, Protsyuk D, Huck V, Knopfova L, Grässle S, Bauer AT, Schneider SW, Borsig L. Monocyte induction of E-selectin-mediated endothelial activation releases VE-cadherin junctions to promote tumor cell extravasation in the metastasis cascade. Cancer Res. 2016;76:5302–5312. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-0784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Roblek M, Protsyuk D, Becker PF, Stefanescu C, Gorzelanny C, Glaus Garzon JF, Knopfova L, Heikenwalder M, Luckow B, Schneider SW. CCL2 is a vascular permeability factor inducing CCR2-dependent endothelial retraction during lung metastasis. Mol Cancer Res. 2019;17:783–793. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-18-0530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dagenais M, Dupaul-Chicoine J, Douglas T, Champagne C, Morizot A, Saleh M. The interleukin (IL)-1R1 pathway is a critical negative regulator of PyMT-mediated mammary tumorigenesis and pulmonary metastasis. Oncoimmunology. 2017;6 doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2017.1287247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wellenstein MD, de Visser KE. Cancer-cell-intrinsic mechanisms shaping the tumor immune landscape. Immunity. 2018;48:399–416. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.