Abstract

Background

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most common cancers worldwide; it is the fourth leading cause of death in the world and the third in Brazil. Mutations in the APC, DCC, KRAS and TP53 genes have been associated with the progression of sporadic CRC, occurring at defined pathological stages of the tumor progression and consequently modulating several genes in the corresponding signaling pathways. Therefore, the identification of gene signatures that occur at each stage during the CRC progression is critical and can present an impact on the diagnosis and prognosis of the patient. In this study, our main goal was to determine these signatures, by evaluating the gene expression of paired colorectal adenoma and adenocarcinoma samples to identify novel genetic markers in association to the adenoma-adenocarcinoma stage transition.

Methods

Ten paired adenoma and adenocarcinoma colorectal samples were subjected to microarray gene expression analysis. In addition, mutations in APC, KRAS and TP53 genes were investigated by DNA sequencing in paired samples of adenoma, adenocarcinoma, normal tissue, and peripheral blood from ten patients.

Results

Gene expression analysis revealed a signature of 689 differentially expressed genes (DEG) (fold-change> 2, p< 0.05), between the adenoma and adenocarcinoma paired samples analyzed. Gene pathway analysis using the 689 DEG identified important cancer pathways such as remodeling of the extracellular matrix and epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Among these DEG, the ETV4 stood out as one of the most expressed in the adenocarcinoma samples, further confirmed in the adenocarcinoma set of samples from the TCGA database. Subsequent in vitro siRNA assays against ETV4 resulted in the decrease of cell proliferation, colony formation and cell migration in the HT29 and SW480 colorectal cell lines. DNA sequencing analysis revealed KRAS and TP53 gene pathogenic mutations, exclusively in the adenocarcinomas samples.

Conclusion

Our study identified a set of genes with high potential to be used as biomarkers in CRC, with a special emphasis on the ETV4 gene, which demonstrated involvement in proliferation and migration.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12885-021-07857-x.

Keywords: Adenoma, Adenocarcinoma, Colorectal, Genetic markers, ETV4

Background

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer worldwide. It represents 10.6 and 9.4% of the total number of cancers in men and women, respectively [1]. Among the different causes of CRC, approximately 75% appears sporadically, that is, without any apparent etiological predisposition [2]. Most sporadic CRC (80%) develops from tubular/villous adenoma [3, 4], and approximately 15% develops from serrated polyps [5]. These tumors, although rare, can also arise from M-cells of the gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) [6–9].

The frequency of transformation of an advanced adenoma into a carcinoma can range from 2.6 to 5.6% depending on the age of the patients [10]. Although this frequency is apparently low, CRC was responsible for 935.173 deaths worldwide and represented about 1.931.590 new cases in 2020 [1]. Despite the high incidence of CRC, and the extensive molecular profiling of these tumors, there are still no available molecular markers that can predict the progression from adenoma to adenocarcinoma.

The goal of this study was to identify a gene signature able to discriminate between adenoma and adenocarcinoma and potentially identify novel CRC biomarkers. To achieve our goal, we performed gene expression profiling in ten paired colorectal adenomas and adenocarcinomas samples. Among the differentially expressed genes (DEG), the ETV4 gene, a variant transcription factor of the ETS family, showed high upregulated expression in the adenocarcinoma samples as compared to adenoma. The overexpression of this gene was further confirmed in the TCGA databases adenocarcinoma samples. Moreover, we observed that the ETV4 knockdown led to decrease in cell proliferation and migration on CRC cell lines, suggesting its potential role in CRC tumorigenesis. Finally, DNA sequencing analysis of the paired samples revealed mutations in the KRAS and TP53 genes in the adenocarcinomas.

Materials and methods

Samples

Paired adenoma, adenocarcinoma and adjacent normal tissue samples from 10 patients were obtained during the surgical procedure at the Clinical Hospital of the Faculty of Medicine, University of São Paulo, Ribeirão Preto (HC-FMRP/USP) under the approval of the HC-FMRP/USP Research Ethics Committee (No 12636/2010). Initially, during the colonoscopy exam, adenomas were collected from patients who also had a second lesion with a clinical characteristic of adenocarcinoma and surgical indication. Each adenoma specimen was divided into two parts: one part was sent for histopathological analysis and the other part was frozen immediately after collection in liquid nitrogen. Patients who underwent the surgical procedure had the tumor resected including a safety margin. Fragments of the tumor and from the margin were also removed and divided in half; one-half was placed in formalin for histopathological analysis and the other half was immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, still in the operating room. Only patients who had histopathological confirmation for the simultaneous presence of adenoma, adenocarcinoma and non-tumor tissue, were selected for molecular analysis. During the collections, all the polyps found were only within adenomas.

Additionally, fifteen adenomas and six adenocarcinoma samples were collected to validate the microarray gene expression profiling by RT-qPCR. The fifteen adenoma samples were isolated from seven males and eight females, with an average age and SD of 66.4±8.683 years (range 48–79). The six adenocarcinoma samples were isolated from five males and one female, with an average age and SD of 74.3±8.500 years (range 62–87). Adenoma samples were collected by colonoscopy and adenocarcinoma samples, by surgery. Using the same methodology used in the matched samples, half of each fragment was sent for histopathological analysis and the other half was frozen in liquid nitrogen for subsequent DNA and RNA isolation.

The inclusion criteria for the selection of samples were based on the clinical and histopathological diagnosis and it included: positive diagnosis for colorectal cancer and presence of adenoma and the agreement to participate in the study, by a signed consent form. Exclusion criteria were: previous treatment (chemo or radiotherapy) and history of Familial Adenomatous Polyposis (FAP), Hereditary Non-Polyposis Syndrome (HNPCC) or inflammatory bowel disease. Clinical data from the patients are shown in Table S1, Additional File 1.

DNA and RNA isolation

Total RNA and DNA were isolated from frozen tissue using TRIzol® Reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions (DNAse and RNAse were used, respectively). The concentrations were evaluated in a NanoVue Plus® spectrophotometer (GE Life Sciences). Specifically for the samples used in the microarrays, the RNA was isolated with RNeasy kit (Qiagen) and its quality assessed by the 2100 Bioanalyzer equipment (Agilent Technologies). Only samples that showed a RIN (RNA Integrity Number) greater than or equal to seven, were considered. The remaining 22 samples, used to validate the microarray results by RT-qPCR, had their RNA integrity assessed on 1.5% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide.

Mutation screening using high resolution melting (HRM) assay

Adenoma and adenocarcinoma samples were subjected to mutational screening using the HRM assay for the entire APC and TP53 gene-coding regions. These regions were amplified with specific sense and antisense primers that flanked each intron/exon, as previously described by Miyoshi et al. (1992) [11] and Bastien et al. (2008) [12] respectively. The HRM analysis was performed in the 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems), using MeltDoctor HRM Master Mix (Applied Biosystems), according to manufacturer’s instructions.

DNA sequencing

DNA fragments amplified by PCR-HRM, showing abnormal melting curves by the HRM assay were subjected to direct sequencing in an automatic capillary sequencing system ABI 3500 XL (Applied Biosystems), using BigDye Terminator kit, following the manufacturer’s instructions. The same methodology was used to sequence exon 2 of the KRAS gene, using specific sense and antisense primers that flanked each intron/exon, as previously described at Fassina et al. (2010) [13]. The sequencing results were analyzed in Chromas Lite v2.1 [14].

The normal paired tissue of the mutated samples was also sequenced, to investigate whether the mutations were of somatic or germline origin. The sequences obtained were compared to the reference from the GenBank NM_000038.5, GenBank NM_000546.5 and GenBank NM_004985.4, respectively to APC, TP53 and KRAS genes.

Pathogenicity prediction was performed in Sift [15] and Mutation Taster [16] online tools and only mutations that were predicted as damaging in both tools were classified as pathogenic.

Microarray hybridizations

To investigate differential gene expression between colorectal adenoma and adenocarcinoma, the platform Whole Human Genome Microarray Kit 4x44K v2 (G4112F, Agilent Technologies) was employed. Prior to the hybridizations, 200 ng of total RNA from each sample were used for cDNA synthesis. The arrays slides were washed following the manufacturer’s guidelines and then scanned using the GenePix 4000B scanner (Axon Instruments) with the GenePix Pro 6.0 software and the hybridization signal intensity of each array was extracted using the Agilent Feature Extraction software 9.5.3.1. (Agilent Technologies).

Microarray data analysis

To evaluate the data quality, we used the array QualityMetrics R/Bioconductor package [17–19]. Normalization was performed by a three-step approach with the R/Bioconductor limma package methods [17, 18, 20]. Initially it was applied as a cyclic loss method between technical replicates, quantile between samples of adenoma and adenocarcinoma group and quantile between arrays [21]. Then, the detection of differentially expressed genes (DEG) was also performed by the limma package, applying the Benjamini-Hochberg method for p-value correction [20, 22]. To evaluate the expression pattern of DEG, Euclidian distance and complete linkage was performed for genes and samples clustering, and then visualized in a heatmap.

Gene expression validation

The reverse transcription reaction was performed using High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After synthesis, the cDNA was diluted 1:5 and then used in quantitative PCR.

TaqMan probes (Applied Biosystems and IDT) were used for RT-qPCR validation of the genes previously selected by microarray. To avoid amplification of genomic DNA (gDNA), no-RT negative control and Taqman probes in exon-exon junction were used. The HPRT1 (4326321E, Applied Biosystems) housekeeping gene was chosen as endogenous control. Primers and probes for gene expression were IL-6 (Hs00174131, Applied Biosystems), IL-8 (Hs00174103, Applied Biosystems), OSM (Hs00171165_M1, Applied Biosystems), SFRP4 (Hs.PT.51.1726538.g, IDT), ETV4 (Hs.PT.56a.23047301.g, IDT), SIM2 (Hs.PT.51.20479148.g, IDT), ESM1 (Hs.PT.51.19279572.g, IDT) e RETNLB (Hs. PT.51.1296566, IDT).

All reactions were performed in an ABI Prism® 7500 Fast Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems). The relative expression for each gene was calculated by the 2-ΔΔCT method [23].

TCGA data analysis

The Hiseq platform gene expression level 3 RNASeqV2 data from normal and tumor samples from Colon Adenocarcinoma (COAD – normal - 41 and tumor - 285) and Rectal Adenocarcinoma (READ - normal - 10 and tumor - 94) were downloaded from the database The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), on March 22, 2017, through the TCGAbiolinks R/Bioconductor package [24]. Differential expression analysis was performed using EdgeR R/Bioconductor package [25]. We considered DEG absolute values of log2 fold-change> 1 and p-value adjusted by FDR≤0.05.

Gene pathways

Gene pathway analysis was performed using the 689 DEG in the MetaCore from Clarivate Analytics. For the analysis in MetaCore we used the fold change of each gene to obtain the enriched gene pathways.

Culture and siRNA assay

For functional assays, HT29 and SW480 colorectal carcinoma cell lines were used (cell lines kindly provided by Prof. Eloiza Helena Tajara da Silva, from UNESP - University of São Paulo State). The cell lines were cultivated in RPMI (Roswell Park Memorial Institute) 1640 medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 0.5% penicillin-streptomycin under controlled temperature and humidity conditions (37 °C, 5% CO2, 95% humidity). For siRNA inhibition studies, cells were transfected with ETV4 siRNA (siETV4) or negative control (siCTRL) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) in a final concentration of 30 nM, using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), according to manufacturer’s instructions. After 48 h of transfection, cells were collected for functional assays, which were all performed in triplicates.

Cell proliferation assay

Cell proliferation assay was performed using CFSE (5,6-carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were transfected (siCTRL and siETV4) and labeled with CFSE simultaneously. A third group of cells with no treatment was used for the cytometer calibration. After 24 h of labeling, cells were evaluated in a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA), and consecutively analyzed every 24 h for a total of 96 h.

Anchorage-dependent colony formation assay

Colorectal cancer cell lines were transfected and cultured in a density of 500 cells/well. After 12 days of culture, the cells were washed with PBS, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, and stained with 0.5% crystal violet. The plates were then photographed on ImageQuant LAS 4000 (GE Healthcare) and colonies were counted.

Transwell migration assay

Cell migration assays were performed on 24-well plates with 8 μm transwell inserts (Greiner Bio One). After 48 h of transfection, 1 × 105 cells were seeded on top of the insert in 200 μl of serum-free medium. In the bottom of the well, cells were seeded in 600 μl of 10% FBS medium. After 24 h of migration, cells were fixed, stained with 0.5% crystal violet and the non-migrating cells from the top of the insert were cleaned with cotton swabs. The inserts were then photographed on ImageQuant LAS 4000 (GE Healthcare) and cells were manually counted.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out in the GraphPad Prism 6.0 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, California, USA) [26]. Mann-Whitney’s test was applied for comparisons between two-independent groups. Statistical analysis of the proliferation assay was determined by two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni multiple comparisons test. P values ≤ 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

DNA sequencing and gene expression analysis of paired samples of colorectal adenoma and adenocarcinoma

DNA sequencing analysis of the ten adenoma-adenocarcinoma sample set, revealed seven mutations in the APC gene, six synonymous and one non-synonymous mutation, all of them germline polymorphisms. Both TP53 and KRAS genes showed three and two somatic damaging mutations (P152L/R273C/R273H and G12A/G2D), in the ten paired samples, respectively. In addition, two polymorphisms were observed in the TP53 gene (Table S2, Additional File 2). Simultaneous mutations co-occurring in the three genes were observed only in three of the ten adenoma/adenocarcinoma samples.

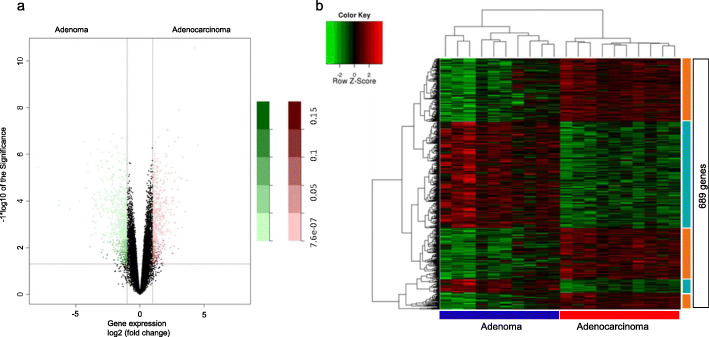

Gene expression analysis from the ten matched colorectal adenoma-adenocarcinoma identified 689 differentially expressed genes (DEG) between these tissue types: 329 genes were upregulated in adenocarcinomas and 360 upregulated in adenomas (Fig. 1a). Unsupervised hierarchical clustering analysis of the 689 DEG was able to delimitate gene clusters specific for each tissue (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

Microarray gene expression analysis in the 10 paired colorectal adenoma and adenocarcinoma samples of this study. A: Volcano Plot representing the set of genes analyzed by gene expression in the ten paired samples of colorectal adenoma and adenocarcinoma. Pink dots represent upregulated genes in adenocarcinoma when compared to adenoma; Green dots represent upregulated genes in adenoma when compared to adenocarcinoma. B: Unsupervised hierarchical clustering analysis in adenoma and adenocarcinoma samples based on the 689 differentially expressed genes (log 2 FC≥2 and FDR≤0,05)

Although we observed some non-synonymous mutations in the TP53 and KRAS genes, those genes were not differentially expressed in our microarray analyses.

The 689 DEGs were used to evaluate the enrichment of gene pathways potentially related to the adenoma-adenocarcinoma transition. Of the ten pathways with the highest number of genes, the pathways of cell adhesion and remodeling, epithelial-mesenchymal transition and the IGF family pathway (related to CRC) stood out.

In order to select genes with a potential role in the adenoma-adenocarcinoma transition process, we applied two filters: first the top 50 most DEG between colorectal adenoma and adenocarcinoma samples (Table 1) were selected. A second filter selected the top 50 genes DEG across all the ten adenocarcinoma-adenoma paired samples (Table 2).

Table 1.

Top 50 DEG genes, 25 upregulated and 25 downregulated, between the paired colorectal adenocarcinoma and adenoma samples (presented by FC)

| Gene | RefSeq | Description | FCa | FDRb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upregulated | ||||

| SFRP4 | NM_003014.3 | secreted frizzled-related protein 4 | 4.51 | 0.00072 |

| SIM2 | NM_005069.3 | single-minded family bHLH transcription factor 2 | 4.26 | 7.63E-07 |

| EREG | NM_001432.2 | epiregulin | 3.54 | 0.01111 |

| FAP | NM_001291807.1 | fibroblast activation protein, alpha | 3.34 | 0.00112 |

| COL11A1 | NM_001190709.1 | collagen, type XI, alpha 1 | 3.09 | 0.00228 |

| FUT1 | NM_000148.3 | fucosyltransferase 1 | 3.04 | 0.00017 |

| ESM1 | NM_001135604.1 | endothelial cell-specific molecule 1 | 2.98 | 0.00060 |

| FABP6 | NM_001040442.1 | fatty acid binding protein 6, ileal | 2.95 | 0.00420 |

| IL8 | NM_000584.3 | interleukin 8 | 2.94 | 0.02829 |

| OSM | NM_020530.4 | oncostatin | 2.87 | 0.00913 |

| IL6 | NM_000600.3 | interleukin 6 | 2.76 | 0.03991 |

| COL1A1 | NM_000088.3 | collagen, type I, alpha 1 | 2.75 | 0.00181 |

| STC2 | NM_003714.2 | stanniocalcin 2 | 2.74 | 0.00060 |

| TDO2 | NM_005651.3 | tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase | 2.69 | 0.00264 |

| OTX1 | NM_001199770.1 | orthodenticle homeobox 1 | 2.68 | 0.01271 |

| WNT2 | NM_003391.2 | wingless-type MMTV integration site family member 2 | 2.65 | 0.00601 |

| CTHRC1 | NM_001256099.1 | collagen triple helix repeat containing 1 | 2.51 | 0.00401 |

| COL8A1 | NM_001850.4 | collagen, type VIII, alpha 1 | 2.50 | 0.00706 |

| NOX4 | NM_001143836.2 | NADPH oxidase 4 | 2.49 | 0.00154 |

| TNFAIP6 | NM_007115.3 | tumor necrosis factor, alpha-induced protein 6 | 2.48 | 0.00776 |

| INHBA | NM_002192.2 | inhibin, beta A | 2.47 | 0.00594 |

| CYR61 | NM_001554.4 | cysteine-rich, angiogenic inducer, 61 | 2.41 | 0.01300 |

| GREM1 | NM_001191322.1 | gremlin 1, DAN family BMP antagonist | 2.40 | 0.03523 |

| CXCL10 | NM_001565.3 | chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 10 | 2.40 | 0.01026 |

| ETV4 | NM_001079675.2 | ets variant 4 | 2.19 | 0.00060 |

| Downregulated | ||||

| CLCA1 | NM_001285.3 | chloride channel accessory 1 | −7.97 | 0.00155 |

| DEFA5 | NM_021010.1 | defensin, alpha 5, Paneth cell-specific | −6.31 | 0.00844 |

| ITLN1 | NM_017625.2 | intelectin 1 | −6.29 | 0.00668 |

| ZG16 | NM_152338.3 | zymogen granule protein 16 | −5.90 | 0.01116 |

| DEFA6 | NM_001926.3 | defensin, alpha 6, Paneth cell-specific | −5.89 | 0.01083 |

| FCGBP | NM_003890.2 | Fc fragment of IgG binding protein | −4.68 | 0.00706 |

| RETNLB | NM_032579.2 | resistin like beta | −4.33 | 0.00060 |

| ITLN2 | NM_080878.2 | intelectin 2 | −4.26 | 0.00391 |

| FAM55D | NM_001077639.1 | neurexophilin and PC-esterase domain family, member 4 | −4.12 | 0.00392 |

| HEPACAM2 | NM_001039372.2 | HEPACAM family member 2 | −4.05 | 0.00131 |

| B3GNT6 | NM_138706.4 | UDP-GlcNAc:betaGal beta-1,3-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase 6 | −4.03 | 0.00177 |

| BEST2 | NM_017682.2 | bestrophin 2 | −3.86 | 0.00099 |

| REG4 | NM_001159352.1 | regenerating islet-derived family member 4 | −3.81 | 0.04009 |

| UGT2B17 | NM_001077.3 | UDP glucuronosyltransferase 2 family, polypeptide B17 | −3.71 | 0.00601 |

| SPINK4 | NM_014471.1 | serine peptidase inhibitor, Kazal type 4 | −3.68 | 0.03954 |

| DPP10-AS1 | NR_036580.1 | DPP10 antisense RNA 1 | −3.67 | 0.01926 |

| SLC4A4 | NM_001098484.2 | solute carrier family 4 | −3.63 | 0.01004 |

| UGT2B15 | NM_001076.3 | UDP glucuronosyltransferase 2 family polypeptide B15 | −3.56 | 0.00500 |

| KLK12 | NM_019598.2 | kallikrein-related peptidase 12 | −3.56 | 0.00633 |

| L1TD1 | NM_001164835.1 | LINE-1 type transposase domain containing 1 | −3.52 | 0.02738 |

| ADH1A | NM_000667.3 | alcohol dehydrogenase 1A (class I) alpha polypeptide | −3.48 | 0.00852 |

| PLA2G2A | NM_000300.3 | phospholipase A2, group IIA (platelets synovial fluid) | −3.43 | 0.01981 |

| VSIG2 | NM_014312.3 | V-set and immunoglobulin domain containing 2 | −3.43 | 0.00681 |

| ADH1C | NM_000669.4 | alcohol dehydrogenase 1C (class I), gamma polypeptide | −3.39 | 0.00776 |

| MB | NM_005368.2 | myoglobin | −3.25 | 0.00144 |

aFC (log2 fold change); bFDR (false discovery rate). The genes in bold were selected for validation by RT-qPCR

Table 2.

Top 50 DEG, 29 upregulated and 21 downregulated, observed exclusively in all the ten samples of adenocarcinoma (presented by FC)

| Gene | RefSeq | Description | FCa | FDRb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upregulated | ||||

| SIM2 | NM_005069.3 | single-minded family bHLH transcription factor 2 | 4.26 | 7.63E-07 |

| FAP | NM_001291807.1 | fibroblast activation protein, alpha | 3.34 | 0.00112 |

| FUT1 | NM_000148.3 | fucosyltransferase 1 | 3.04 | 0.00017 |

| ESM1 | NM_001135604.1 | endothelial cell-specific molecule 1 | 2.98 | 0.00060 |

| FABP6 | NM_001040442.1 | fatty acid binding protein 6, ileal | 2.95 | 0.00420 |

| COL1A1 | NM_000088.3 | collagen, type I, alpha 1 | 2.75 | 0.00181 |

| WNT2 | NM_003391.2 | wingless-type MMTV integration site family member 2 | 2.65 | 0.00601 |

| ELN | NM_000501.3 | elastin | 2.22 | 0.00072 |

| ETV4 | NM_001079675.2 | ets variant 4 | 2.18 | 0.00060 |

| ACAN | NM_001135.3 | aggrecan | 2.12 | 0.00107 |

| LARP6 | NM_001286679.1 | La ribonucleoprotein domain family, member 6 | 2.00 | 0.00111 |

| FADS1 | NM_013402.4 | fatty acid desaturase | 2.00 | 0.00099 |

| SCRN1 | NM_001145513.1 | secernin 1 | 1.97 | 0.00188 |

| LY6E | NM_001127213.1 | lymphocyte antigen 6 complex, locus E | 1.95 | 0.00691 |

| TCFL5 | NM_006602.2 | transcription factor-like 5 (basic helix-loop-helix) | 1.91 | 0.00426 |

| PROCR | NM_006404.4 | protein C receptor, endothelial | 1.90 | 0.00745 |

| FAM150A | NM_001195732.1 | family with sequence similarity 150 member A | 1.87 | 0.00283 |

| COL5A2 | NM_000393.3 | collagen, type V, alpha 2 | 1.73 | 0.00601 |

| FAM72D | NM_207418.2 | family with sequence similarity 72 member D | 1.62 | 0.00262 |

| SPARC | NM_003118.3 | secreted protein, acidic, cysteine-rich (osteonectin) | 1.62 | 0.00420 |

| PARVB | NM_001003828.2 | parvin, beta | 1.56 | 0.01610 |

| VEGFA | NM_001025366.2 | vascular endothelial growth factor A | 1.46 | 0.00123 |

| UBE2C | NM_001281741.1 | ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme | 1.45 | 0.00060 |

| AUNIP | NM_001287490.1 | aurora kinase A and ninein interacting protein | 1.35 | 0.00177 |

| GK | NM_000167.5 | glycerol kinase | 1.26 | 0.00437 |

| LRP8 | NM_001018054.2 | low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 8, apolipoprotein e receptor | 1.15 | 0.01137 |

| DIAPH3 | NM_001042517.1 | diaphanous-related formin 3 | 1.11 | 0.00178 |

| FAM162B | NM_001085480.2 | family with sequence similarity 162 member B | 1.05 | 0.04851 |

| CENPJ | NM_018451.4 | centromere protein J | 1.04 | 0.00243 |

| Downregulated | ||||

| CLCA1 | NM_001285.3 | chloride channel accessory 1 | −7.97 | 0.00155 |

| HEPACAM2 | NM_001039372.2 | HEPACAM family member 2 | −4.05 | 0.00131 |

| B3GNT6 | NM_138706.4 | UDP-GlcNAc:betaGal beta-1,3-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase 6 | −4.03 | 0.00177 |

| BEST2 | NM_017682.2 | bestrophin 2 | −3.86 | 0.00099 |

| L1TD1 | NM_001164835.1 | LINE-1 type transposase domain containing 1 | −3.52 | 0.02738 |

| ADH1A | NM_000667.3 | alcohol dehydrogenase 1A (class I) alpha polypeptide | −3.48 | 0.00852 |

| ADH1C | NM_000669.4 | alcohol dehydrogenase 1C (class I), gamma polypeptide | −3.39 | 0.00776 |

| GALNT8 | NM_017417.1 | polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase 8 | −3.24 | 0.00084 |

| SPTLC3 | NM_018327.2 | serine palmitoyltransferase, long chain base subunit 3 | −2.99 | 0.00244 |

| SPINK2 | NM_001271718.1 | serine peptidase inhibitor, Kazal type 2 (acrosin-trypsin inhibitor) | −2.49 | 0.01166 |

| ATOH8 | NM_153778.3 | atonal homolog 8 | −2.32 | 0.00643 |

| KCNMA1 | NM_001014797.2 | potassium large conductance calcium-activated channel, subfamily M, alpha member 1 | −2.27 | 0.00060 |

| NEURL | NM_004210.4 | neuralized E3 ubiquitin protein ligase 1 | −2.19 | 0.00109 |

| PIGR | NM_002644.3 | polymeric immunoglobulin receptor | −2.14 | 0.01272 |

| MFSD4 | NM_181644.4 | major facilitator superfamily domain containing 4 | −2.11 | 0.00201 |

| ARHGAP44 | NM_014859.4 | Rho GTPase activating protein 44 | −2.06 | 0.00060 |

| SERTAD4 | NM_019605.3 | SERTA domain containing 4 | −1.82 | 0.00072 |

| PLA2G10 | NM_003561.1 | phospholipase A2, group X | −1.73 | 0.04438 |

| NEDD4L | NM_001144964.1 | eural precursor cell expressed, developmentally down-regulated 4-like, E3 ubiquitin protein ligase | −1.61 | 0.00123 |

| ACADVL | NM_000018.3 | acyl-CoA dehydrogenase, very long chain | −1.20 | 0.00099 |

| PID1 | NM_001100818.1 | phosphotyrosine interaction domain containing 1 | −1.19 | 0.01212 |

aFC (log2 fold change); bFDR (false discovery rate). The genes in bold are the same ones selected in Table 1 for validation by RT-qPCR

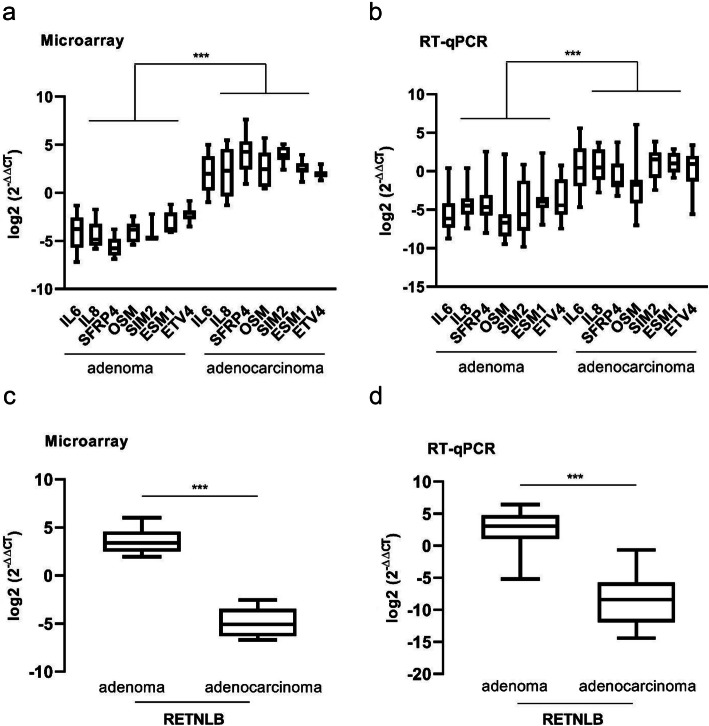

To confirm the gene expression data obtained from microarray analysis, eight genes were selected for validation by RT-qPCR (SIM2, ESM1, SFRP4, IL8, IL6, OSM, ETV4 and RETNLB) on 25 adenomas and 16 adenocarcinomas (the initial 10 adenoma/adenocarcinoma paired samples and additional 15 adenomas and 6 adenocarcinoma samples). The RT-qPCR results were in agreement with the microarray data. In addition, genes presented a very similar expression pattern between the adenoma-adenocarcinoma pairs in both techniques (Fig. 2a-d), reinforcing the robustness of the data.

Fig. 2.

Validation of microarray data by RT-qPCR. a Microarray data of the 10 paired adenoma/adenocarcinoma paired samples, showing the upregulation of seven genes in adenocarcinomas compared to adenomas. b RT-qPCR results showing the validation of the microarray results of the same set of genes in a larger set of samples (25 adenoma and 16 adenocarcinoma samples, of which 10 adenoma/adenocarcinoma paired samples and 15 adenoma and 6 adenocarcinoma additional new samples). c and d Relative expression of the RETNLB gene found downregulated in adenocarcinomas when compared to adenomas by microarray (10 paired adenoma-adenocarcinoma samples) and RT-qPCR (10 adenoma/adenocarcinoma paired samples plus 15 adenoma and 6 adenocarcinoma samples) analysis, respectively. Fold changes (log2 FC) between the expression means in adenomas and adenocarcinomas were A = 6.75, B=4.93, C=8.50 and D=11.12. Mann-Whitney’s test was used for statistical analysis (A and B: ***p < 0.0006; C and D: ***p < 0.0001)

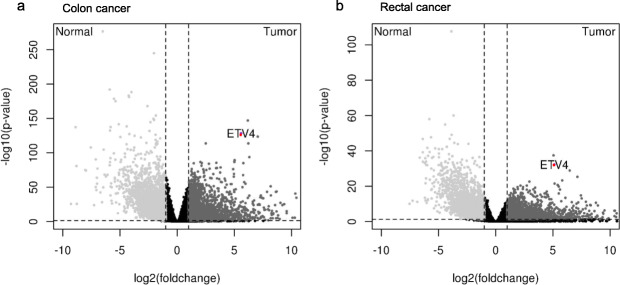

To further validate our findings in a different cohort using non-neoplastic tissue, we performed an in silico gene expression analysis between normal colorectal tissue and both colon and rectal adenocarcinoma, using data available at TCGA.

Gene expression analyses were performed separately. First, normal colon tissue and colon adenocarcinoma were compared (Fig. 3a). A second analysis compared the normal rectal tissue with the rectal adenocarcinoma (Fig. 3b). In both analyses, ETV4 was overexpressed in adenocarcinoma samples (Fig. 2a-b). As this gene was also found to be upregulated in our cohort (Table 1), we proceeded with a functional investigation of its role in colorectal tumorigenesis.

Fig. 3.

Gene expression analysis of the colon and rectum normal or cancer samples from the TCGA database. a Volcano plot representing the differentially expressed genes between 41 normal tissue and 285 colon adenocarcinomas samples (FDR=4.91e-129 and log2 fold change = 5.59). b Volcano plot representing the differentially expressed genes between 10 normal tissue samples and 94 colon adenocarcinomas samples (FDR= 5.544394e-33 and log2 fold change = 5.13). Red dot: ETV4 gene overexpressed in cancer samples

ETV4 acts in the proliferation, colony formation and cellular migration

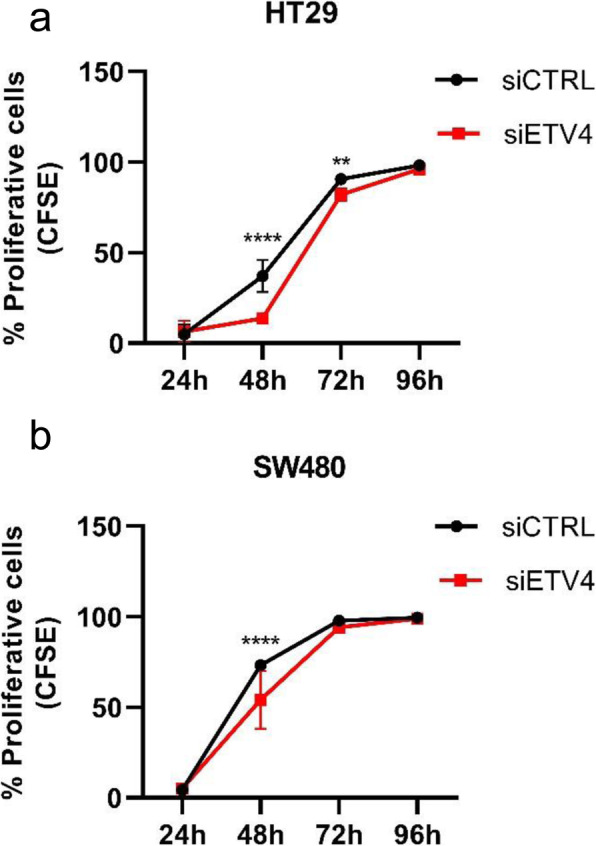

To investigate the possible role of ETV4 in colorectal carcinoma tumorigenesis, HT29 and SW480 colorectal cancer cell lines were used in functional assays. Transient transfection using siRNA oligos efficiently knocked down 80% of the ETV4 gene expression levels in HT29 cell line and 88% in SW480 cell line, as confirmed by RT-qPCR (Supplementary Figure 1, Additional File 3). Cell proliferation rates were analyzed by CFSE labelling and evaluated by flow cytometry every 24 h during 96 h. The results showed a significant reduction of HT29 cell proliferation rates at 48 h and 72 h after transfection with ETV4-siRNA (Fig. 4a). Accordingly, in SW480 cells depleted for ETV4 expression, cell proliferation was significantly reduced after 48 h (Fig. 4b). Downregulation of ETV4 expression in colorectal cell lines did not affect cell apoptosis or viability, (Supplementary Figure 2A-B, Additional File 4), indicating that the results observed are exclusively due to the modulation of cell proliferation.

Fig. 4.

The knockdown of the ETV4 gene led to decrease of cell proliferation in both CRC cell lines: HT29 (a) and SW480 (b). Cells were simultaneously transfected with siRNAs and stained for CFSE, and then plated in 24 well plates. Flow cytometry analysis of CFSE staining were performed every 24 h during 96 h (**p< 0.05; ****p< 0.0001 Two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni correction)

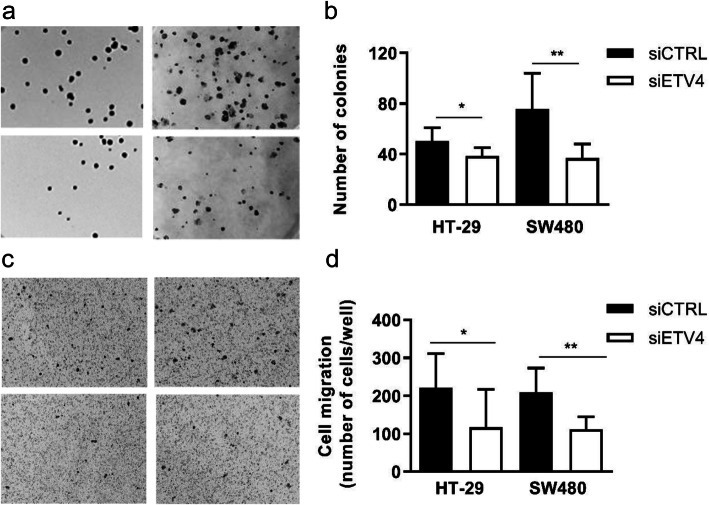

Colony formation assays were also performed by counting the number of colonies formed by sparsely cultured cells after 12 days. ETV4 gene knockdown in HT29 and SW480 cells impaired their ability to grow as colonies in 20 and 50%, respectively (Fig. 5a-b). We also evaluated the effect of ETV4 gene knockdown on the migratory capacity of colorectal tumor cell lines. The migration assay was performed on transwell membranes 24 h after the ETV4 knockdown in the HT29 and SW480 cell lines. As it can be seen in Fig. 5c-d, depletion of ETV4 expression decreased cell migration in both cell lines. Taken together, these results suggest an important role of ETV4 in diverse tumorigenic processes, such as cell proliferation, migration, and colony formation.

Fig. 5.

Knockdown of the ETV4 gene reduced the clonogenic ability and cell migration in the CRC cell lines HT29 and SW480. a Representative images of cell colonies formed after 12 days of culture. b Bar graph representing the mean of three independent experiments. CRC cells were sparsely plated in 6 well plates (500 cells/well), allowed to grow for 12 days, fixed and stained for manual counting (HT29: p=0.0402; SW480: p=0.0015, Mann-Whitney statistical test). c Representative images of cell migration. d Bar graph representing the mean of three independent experiments. Cells were seeded on the top of the insert (1 × 105), fixed 24 h, and stained for manual counting (HT29: p= 0.0231; SW480: p=0.0152, Mann-Whitney statistical test)

Discussion

Adenoma and adenocarcinoma colorectal gene signatures

In this study, the analysis of gene expression profiles of adenomas and adenocarcinomas by microarrays and signaling pathways analysis revealed many pathways and cellular processes associated with extracellular matrix remodeling, angiogenesis and epithelial-mesenchymal transition, as well as the IGF (Insulin-like growth factor) signaling pathway, which is known to be directly linked to colorectal cancer (Metacore from Clarivate Analytics) (Table S3, Additional File 5).

The strategy of comparing adenoma-adenocarcinoma samples from the same patient reduces sample and tumor heterogeneity, increasing the power of the study to generate a potential gene signature for the adenoma-adenocarcinoma transition.

Several studies on differentially expressed genes in CRC are found in the literature. However, the different microarray platforms and statistical methods used in these studies hamper the discovery of reliable biomarkers to be used in clinical practice. To overcome this limitation, some research groups [27–30] applied meta-analysis approaches, comparing different microarray analysis in samples from normal tissue, adenoma and adenocarcinoma or only between normal tissue and adenocarcinoma. Some of the genes described in these meta-analysis studies were also found in our data and are briefly discussed below. FcGBP, was found to be downregulated in our study and in normal-adenoma-carcinoma sequence according to Lee and colleagues [31]. FcGBP was also indicated as a prognosis marker in gallbladder cancer [32]. CLCA1 has been described as a marker of the transition from proliferation to differentiation in CRC [33]. CLCA1 decreased expression was also described in serum and CRC tissues, showing an inverse correlation with CRC metastasis and tumor stage [34]. CLCA1 and ADH1C were shown to be downregulated in familial adenomatous polyposis [35]. SLC4A4 associated with proliferation and migration in colon and breast cancer [36]. COL1A1 was overexpressed in tumor tissues from colorectal adenocarcinomas and its silencing significantly inhibited proliferation, migration and invasion, while cell apoptosis was promoted [37]. ZG16 has been associated with stemness and progression in CRC [38] and its expression has been shown to be sequentially reduced from normal tissue to adenoma and to carcinoma [39]. ETV4 and FABP6 were co-expressed in tumor samples and significantly associated with metastasis in CRC [40]. DEFA6 was shown to be associated with overall survival rate and is an independent prognostic marker for CRC [41]. L1TD1 has been described as a good prognosis marker candidate in CRC, but its elevated expression has also been associated with poor prognosis in other cancer types. These distinctive roles are dependent on its interaction partners. Several co-expression partners of L1TD1 already described in CRC have also been observed in our study, such as SPINK4, RETNLB, CLCA1, FcGBP, HEPACAM2, ITLN1 and, DEFA5 [42]. The common genes observed in our study with previous meta-analysis and other studies reinforces the importance of our findings.

ETV4 functional validation

The ETV4 gene (E1AF/PEA3 - ets variant 4) is a transcription factor member of the ETS oncogene family that comprises a conserved amino acid sequence, the ETS domain, the DNA binding site to the ETS oncogenes [43]. Its elevated expression has been described in several types of cancer, such as breast, ovary, prostate, gastric and colorectal [44–48].

Our assays demonstrated that ETV4 silencing in the HT29 and SW480 CRC cell lines reduced proliferation, colony formation and cell migration. Previous studies have shown the effects of ETV4 silencing in the reduction of cell proliferation, migration and invasion, in both colon and prostate cancer cell lines, but no data on colony formation has been previously associated with ETV4 in CRCs [49, 50]. Hence, our results suggest that ETV4 is important for the growth of CRC cells.

The reduction in proliferation demonstrated by Hollenhorst et al (2011) [51] in prostate cancer cell lines after ETV4 inhibition was found in combination with a decreased MYC gene expression, due to the direct regulation of MYC by ETV4. Our findings are in agreement with the reduced proliferation after ETV4 inhibition however, we identified an increase in MYC gene expression in adenocarcinomas as compared to adenomas.

Previous studies have shown that activation of multiple matrix metalloproteinases plays an important role in tumor invasion by degradation of the extracellular matrix in colorectal cancer [52–55]. MMP1 was identified as a direct or indirect ETV4 target acting on the CRC progression [56]. In a study carried out in non-small cell lung cancer [57] the ETV4-MMP1 axis was associated with a poor prognosis. A similar relationship was observed in breast cancer, but for ETV4 and MMP13 [58].

In our samples, only MMP11 (stromelysin-3) was upregulated in adenocarcinoma compared with paired adenoma samples. This metalloproteinase is described in several types of cancer, acting in the proliferation, migration and invasion control [59–61]. In CRC, elevated MMP11 expression was associated with poor prognosis and reduced survival in stage II patients [62]. Serum levels of MMP11 were previously shown to be significantly higher in patients with lymph node metastasis and was also identified as an independent prognostic factor for 5-year mortality in CRC [63]. MMP11 upregulation has also been related to lymph node metastasis in non-small cell lung cancer and colorectal cancer [64, 65]. Accordingly, MMP11 was upregulated in all our cases that also had compromised lymph nodes. To our knowledge, there is no information available about the relationship between ETV4 and MMP11, so one might speculate that both genes may be involved in lymph node metastasis in CRC. Indeed, ETV4 is related to the embryonic development of different organs, but it is also closely linked to carcinogenesis, especially in metastasis development [66].

Several studies indicate the activation of MMPs by ETV4 [58, 67, 68]. However, it is likely that this activation occurs in dependence of expression and/or functional alterations in other genes involved in the MMP/ETV4 axis.

Conclusions

In summary, this study identified a set of differentially expressed genes in CRC, including FcGBP, CLCA1, ADH1C, COL1A1, ZG16, which could be strong candidates to be used as biomarkers of colorectal adenoma-adenocarcinoma progression. Among those genes, ETV4 was further investigated and was shown to act on proliferation and migration of CRC cell lines, indicating that ETV4 could be a robust adenocarcinoma biomarker and a potential target for gene therapy studies in CRC.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1 Table S1. Location and pathological tissue of each patient.

Additional file 2 Table S2. Observed mutations in APC,TP53 and KRAS genes.

Additional file 3 Figure S1. Relative expression of the ETV4 gene after its silencing in HT29 and SW480 CRC cell lines. The silencing was efficient with p < 0,0001.

Additional file 4 Figure S2. Apoptosis assay. The HT29 and SW480 cell lines did not show any changes in the apoptosis’ rates (A) and cell viability (B).

Additional file 5 Table S3. Enrichment of signaling pathways analysis.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the medical and nursing staff of the department of proctology HC-FMRP-USP for the excellent work in collecting the samples. We wish to thank Amelia Goes Araújo and Adriana Marques Apª technical support in microarray and sequencing respectively. We thank Wagner Nagib de Souza Birbeire for the preparation of the images. We also thank Dr. Luciane R. Cavalli for the comments and final reading of the text.

Abbreviations

- CRC

Colorectal cancer

- GALT

Gut-associated lymphoid tissue

- HC-FMRP/USP

Hospital of the Faculty of Medicine of Ribeirão Preto/University of São Paulo

- FAP

Familial adenomatous polyposis

- HNPCC

Hereditary Non-Polyposis Syndrome

- HRM

High Resolution Melting

- PCR

Polymerase Chain Reaction

- DEG

Differentially expressed genes

- RT-qPCR

Reverse transcription quantitative real time PCR

- COAD

Colon adenocarcinoma

- READ

Rectal adenocarcinoma

- TCGA

The cancer genome atlas

- UNESP

University of São Paulo State

- RPMI

Roswell Park Memorial Institute

- FBS

Fetal bovine serum

- siRNA

Small interfering RNA

- siCTRL

Small interfering negative control

- CFSE

5(6)-carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester

- PBS

Phosphate buffered saline

- FDR

False Discovery rate

- ECM

Extracellular matrix

Authors’ contributions

ASF, CPA, DLZ, DOV, MAZ participated in the study design. MCB, JESS, JRP performed bioinformatics analysis. RAP performed microarray hybridization. ASF, AR, GAM, ARDS, GMA performed the experiments. ASF, AR, LFA, RBLB, analyzed the data. GEBS performed the pathological examination. FMP, OF, JJRR contributed in sample collecting. ASF wrote the paper. GAM, LFA, AR, DLZ helped with manuscript preparation. WASJr supervised the entire project. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

AFFILIATIONS.

Department of Genetics, Ribeirão Preto Medical School, University of São Paulo, USP, Ribeirão Preto, SP, Brazil.

Aline Simoneti Fonseca, Anelisa Ramão, Dalila Lucíola Zanette, Greice Andreotti de Molfetta, Luiza Ferreira de Araújo, Rafaela de Barros e Lima Bueno & Wilson Araújo Silva Jr.

Center for Cell Based Therapy and National Institute of Science and Technology in Stem Cell and Cell Therapy, Ribeirão Preto, SP, Brazil.

Aline Simoneti Fonseca, Anelisa Ramão, Matheus Carvalho Bürger, Jorge Estefano Santana de Souza, Dalila Lucíola Zanette, Greice Andreotti de Molfetta, Luiza Ferreira de Araújo, Rafaela de Barros e Lima Bueno, Graziela Moura Aguiar, Jessica Rodrigues Plaça, Cleidson de Pádua Alves, Anemari Ramos Dinarte dos Santos, Daniel Onofre Vidal, Rodrigo Alexandre Panepucci, Marco Antonio Zago & Wilson Araújo Silva Jr.

Center for Integrative Systems Biology - CISBi, NAP/USP Ribeirão Preto, SP, Brazil.

Aline Simoneti Fonseca, Dalila Lucíola Zanette, Greice Andreotti de Molfetta, Luiza Ferreira de Araújo & Wilson Araújo Silva Jr.

Research Institute Pelé Pequeno Príncipe, Curitiba, PR, Brazil.

Aline Simoneti Fonseca.

Departament of Medical Clinic, Medical School of Ribeirão Preto, University of São Paulo, USP, Ribeirão Preto, SP, Brazil.

Fernanda Maria Peria.

Laboratory of Immunofluorescence and Electron Microscopy (LIME), Presidente Dutra University Hospital (HUUFMA), São Luís, MA, Brazil.

Gyl Eanes Barros Silva.

Departament of Surgery and Anatomy, Medical School of Ribeirão Preto, University of São Paulo, USP Ribeirão Preto, SP, Brazil.

Omar Feres & José Joaquim Ribeiro da Rocha.

Laboratory of Applied Science and Technology in Health (LASTH), Instituto Carlos Chagas, Fundação Oswaldo Cruz, Curitiba, Brazil.

Dalila Luciola Zanette.

CORRESPONDING AUTHORS.

Correspondence to: Wilson Araújo Silva Jr. and Aline Simoneti Fonseca

Funding

This work was jointly supported by Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior - Brasil (CAPES/PROEX), grant no. 801084; São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP), grant no. 2013/08135–2 and by Research Support of the University Sao Paulo, CISBi-NAP/USP, grant no. 12.1.25441.01.2./08135–2.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Clinical Hospital of FMRP/USP Research Ethics Committee (No 12636/2010). The consent form was signed by all participants in this study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Aline Simoneti Fonseca, Email: aline.fonseca@pelepequenoprincipe.org.br.

Wilson Araújo Silva, Jr, Email: wilsonjr@usp.br.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Global Cancer Observatory. International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). https://gco.iarc.fr/today/home. Accessed 23 December 2020.

- 2.Hisamuddin IM, Yang VW. Genetics of Colorectal Cancer. MedGenMed. 2004;6(3):13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muto T, Bussey HJR, Morson BC. The evolution of cancer of the colon and rectum. Cancer. 1975;36:2251–2270. doi: 10.1002/cncr.2820360944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shinya H, Wolff WI. Morphology, Anatomic Distribution and Cancer Potential of Colonic Polyps. Ann Surg. 1979;190(6):679–683. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197912000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mäkinen MJ, George SMC, Jernvall P, Mäkelä J, Vihko P, et al. Colorectal carcinoma associated with serrated adenoma - prevalence, histological features, and prognosis. J Pathol. 2001;193(3):286–294. doi: 10.1002/1096-9896(2000)9999:9999<::AID-PATH800>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamada M, Sekine S, Matsuda T, Yoshida M, Taniguchi H, et al. Dome-type carcinoma of the colon; a rare variant of adenocarcinoma resembling a submucosal tumor: a case report. BMC Gastroenterol. 2012;12:21. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-12-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Puppa G, Molaro M. Dome-Type: A Distinctive Variant of Colonic Adenocarcinoma. Case Rep Pathol. 2012;2012:284064. doi: 10.1155/2012/284064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Orłowska J. Serrated Polyps of the Colorectum: Histological Classification and Clinical Significance. Pol J Pathol. 2010;1:8–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rubio CA, Puppa G, de Petris G, Kis L, Schmidt PT. The third pathway of colorectal carcinogenesis. J Clin Pathol. 2017;0:1–5. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2017-204660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brenner H, Hoffmeister M, Stegmaier C, Brenner G, Altenhofen L, Haug U. Risk of progression of advanced adenomas to colorectal cancer by age and sex: estimates based on 840 149 screening colonoscopies. Gut. 2007;56(11):1585–1589. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.122739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miyoshi Y, Ando H, Nagase H, Nishisho I, Horii A. Germ-line mutations of the APC gene in 53 familial adenomatous polyposis patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1992;89:4452–4456. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.10.4452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bastien R, Lewis TB, Hawkes JE, Quackenbush JF, Robbins TC, et al. High-Throughput Amplicon Scanning of the TP53 Gene in Breast Cancer Using High-Resolution Fluorescent Melting Curve Analyses and Automatic Mutation Calling. Hum Mutation. 2008;29(5):757–764. doi: 10.1002/humu.20726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fassina A, Gazziero A, Zardo D, Corradin M, Aldighieri E, Rossi GP. Detection of EGFR and KRAS mutations on transthoracic needle aspiration of lung nodules by high resolution melting analysis. J Clin Pathol. 2009;62:1096–1102. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2009.067587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chromas Lite version 2.1 . Technelysium Pty Ltd, South Brisbane, Queensland, Australia. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumar P, Henikoff S, Ng PC. Predicting the effects of coding non-synonymous variants on protein function using the SIFT algorithm. Nat Protoc. 2009;4(7):1073–1081. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schwarz JM, Cooper DN, Schuelke M, Seelow D. MutationTaster2: mutation prediction for the deep-sequencing age. Nat Methods. 2014;11(4):361–362. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.R Core Team . R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gentleman RC, Carey VJ, Bates DM, Bolstad B, Dettling M, et al. Bioconductor: Open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics. Genome Biol. 2004;5(10):R80. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-10-r80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kauffmann A, Gentleman R, Huber W. arrayQualityMetrics--a bioconductor package for quality assessment of microarray data. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(3):415–416. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smyth GK. Limma: linear models for microarray data. In: Gentleman R, Carey V, Dudoit S, Irizarry R, Huber W, editors. Bioinformatics and Computational Biology Solutions using R and Bioconductor. New York: Springer; 2005. pp. 397–420. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bolstad BM, Irizarry RA, Astrand M, Speed TP. A comparison of normalization methods for high density oligonucleotide array data based on bias and variance. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:185–193. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/19.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc B. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2-DDCT method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Colaprico A, Silva TC, Olsen C, Garofano L, Cava C, Garolini D, Sabedot TS, Malta TM, Pagnotta SM, Castiglioni I, Ceccarelli M, Bontempi G, Noushmehr H. TCGAbiolinks: na R/Bioconductor package for integrative analysis of TCGA data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(8):e71. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(1):139–140. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Swift ML. GraphPad prism, data analysis, and scientific graphing. J Chem Inform Comput Sci. 1997;37(2):411−2.

- 27.Chan SK, Griffith OL, Tai IT, Jones SJM. Meta-analysis of Colorectal Cancer Gene Expression Profiling Studies Identifies Consistently Reported Candidate Biomarkers. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17(3):543–552. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jung Y, Lee S, Choi H-S, Kim S-N, Lee E, et al. Clinical Validation of Colorectal Cancer Biomarkers Identified from Bioinformatics Analysis of Public Expression Data. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(4):700–709. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chu CM, Yao CT, Chang YT, Chou HL, Chou YC, et al. Gene expression profiling of colorectal tumors and normal mucosa by microarrays metaanalysis using prediction analysis of microarray, artificial neural network, classification, and regression trees. Dis Markers. 2014;(2014):634123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Hauptman N, Boštjančič E, Žlajpah M, Ranković B, Zidar N. Bioinformatics Analysis Reveals Most Prominent Gene Candidates to Distinguish Colorectal Adenoma from Adenocarcinoma. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:9416515. doi: 10.1155/2018/9416515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee S, Bang S, Song K, Lee I. Differential expression in normal-adenoma-carcinoma sequence suggests complex molecular carcinogenesis in colon. Oncol Rep. 2006;16(4):747–754. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xiong L, Wen Y, Miao X, Yang Z. NT5E and FcGBP as key regulators of TGF-1-induced epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) are associated with tumor progression and survival of patients with gallbladder cancer. Cell Tissue Res. 2014;355:365–374. doi: 10.1007/s00441-013-1752-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang B, Cao L, Liu B, McCaig CD, Pu J. The transition from proliferation to differentiation in colorectal cancer is regulated by the calcium activated chloride channel a1. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(4):e60861. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li X, Hu W, Zhou J, Huang Y, Peng J, et al. CLCA1 suppresses colorectal cancer aggressiveness via inhibition of the Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway. Cell Commun Signal. 2017;15(1):38. doi: 10.1186/s12964-017-0192-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thiruvengadam SS, O’Malley M, La Guardia L, Lopez R, Wang Z, et al. Gene Expression Changes Accompanying the Duodenal Adenoma-Carcinoma Sequence in Familial Adenomatous Polyposis. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2019;10(6):e00053. doi: 10.14309/ctg.0000000000000053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parks SK, Pouyssegur J. The Na+/HCO3− Co-transporter SLC4A4 plays a role in growth and migration of colon and breast cancer cells. J Cell Physiol. 2015;230:1954–1963. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu W, Yang Z, Long F, Luo L, Deng Q, et al. COL1A1 and MZB1 as the hub genes influenced the proliferation, invasion, migration and apoptosis of rectum adenocarcinoma cells by weighted correlation network analysis. Bioorg Chem. 2020;95:103457. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2019.103457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen X, Du P, She J, Cao L, Li Y, et al. Loss of ZG16 is regulated by miR-196a and contributes to stemness and progression of colorectal cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7(52):86695–86703. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.13435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meng H, Li W, Boardman LA, Wang L. Loss of ZG16 is associated with molecular and clinicopathological phenotypes of colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1):433. doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-4337-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eskandari E, Mahjoubi F, Motalebzadeh J. An integrated study on TFs and miRNAs in colorectal cancer metastasis and evaluation of three co-regulated candidate genes as prognostic markers. Gene. 2018;679:150–159. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2018.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jeong D, Kim H, Kim D, Ban S, Oh S, et al. Defensin alpha 6 (DEFA6) is a prognostic marker in colorectal cancer. Cancer Biomark. 2019;24(4):485–495. doi: 10.3233/CBM-182221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chakroborty D, Emani MR, Klén R, et al. L1TD1 - a prognostic marker for colon cancer. BMC Cancer. 2019;19(1):727. doi: 10.1186/s12885-019-5952-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Higashino F, Yoshida K, Fujinaga Y, Kamio K, Fujinaga K. Isolation of a cDNA encoding the adenovirus ElA enhancer binding protein: a new human member of the ets oncogene family. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21(3):547–553. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.3.547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Davidson B, Goldberg I, Gotlieb WH, Kopolovic J, Ben-Baruch G, et al. PEA3 Is the Second Ets Family Transcription Factor Involved in Tumor Progression in Ovarian Carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9(4):1412–1419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Clementz AG, Rogowski A, Pandya K, Miele L, Osipo C. NOTCH-1 and NOTCH-4 are novel gene targets of PEA3 in breast cancer: novel therapeutic implications. Breast Cancer Res. 2011;13(3):R63. doi: 10.1186/bcr2900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Keld R, Guo B, Downey P, Cummins R, Gulmann C, et al. PEA3/ETV4-related transcription factors coupled with active ERK signalling are associated with poor prognosis in gastric adenocarcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2011;105(1):124–130. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Aytes A, Mitrofanova A, Kinkade CW, Lefebvre C, Lei M, et al. ETV4 promotes metastasis in response to activation of PI3-kinase and Ras signaling in a mouse model of advanced prostate cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(37):E3506–E3515. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1303558110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mesci A, Taeb S, Huang X, Jairath R, Sivaloganathan D, et al. Pea3 expression promotes the invasive and metastatic potential of colorectal carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(46):17376–17387. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i46.17376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moss AC, Lawlor G, Murray D, Tighe D, Madden SF, et al. ETV4 and Myeov knockdown impairs colon cancer cell line proliferation and invasion. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;345(1):216–221. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.04.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pellecchia A, Pescucci C, De Lorenzo E, Luceri C, Passaro N, et al. Overexpression of ETV4 is oncogenic in prostate cells through promotion of both cell proliferation and epithelial to mesenchymal transition. Oncogenesis. 2012;1:e20. doi: 10.1038/oncsis.2012.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hollenhorst PC, Ferris MW, Hull MA, Chae H, Kim S, et al. Oncogenic ETS proteins mimic activated RAS/MAPK signaling in prostate cells. Genes Dev. 2011;25(20):2147–2157. doi: 10.1101/gad.17546311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Deng J, Chen W, Du Y, et al. Synergistic efficacy of Cullin1 and MMP-2 expressions in diagnosis and prognosis of colorectal cancer. Cancer Biomark. 2017;19(1):57–64. doi: 10.3233/CBM-160341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu H, Zhou B, Wang L, Li Y, Zhou ZG, et al. Association of E1AF mRNA expression with tumor progression and matrilysin in human rectal cancer. Oncology. 2007;73(5–6):384–388. doi: 10.1159/000136158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang W, Li D, Xiang L, Lv M, Tao L, et al. TIMP-2 inhibits metastasis and predicts prognosis of colorectal cancer via regulating MMP-9. Cell Adh Migr. 2019;13(1):273–284. doi: 10.1080/19336918.2019.1639303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yan Q, Yuan Y, Yankui L, et al. The Expression and Significance of CXCR5 and MMP-13 in Colorectal Cancer. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2015;73(1):253–259. doi: 10.1007/s12013-015-0624-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Horiuchi S, Yamamoto H, Min Y, Adachi Y, Itoh F. Association of ets-related transcriptional factor E1AF expression with tumour progression and overexpression of MMP-1 and matrilysin in human colorectal cancer. J Pathol. 2003;200(5):568–576. doi: 10.1002/path.1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang Y, Ding X, Liu B, et al. ETV4 overexpression promotes progression of non-small cell lung cancer by upregulating PXN and MMP1 transcriptionally. Mol Carcinog. 2020;59(1):73–86. doi: 10.1002/mc.23130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dumortier M, Ladam F, Damour I, et al. ETV4 transcription factor and MMP13 metalloprotease are interplaying actors of breast tumorigenesis. Breast Cancer Res. 2018;20(1):73. doi: 10.1186/s13058-018-0992-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang Z, Dong T, Fu Y, et al. MMP-11 promotes papillary thyroid cell proliferation and invasion via the NF-κB pathway [published online ahead of print, 2018 Sep 1]. J Cell Biochem. 2018. 10.1002/jcb.27500. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 60.Hsin CH, Chou YE, Yang SF, et al. MMP-11 promoted the oral cancer migration and Fak/Src activation. Oncotarget. 2017;8(20):32783–32793. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Su C, Wang W, Wang C. IGF-1-induced MMP-11 expression promotes the proliferation and invasion of gastric cancer cells through the JAK1/STAT3 signaling pathway. Oncol Lett. 2018;15(5):7000–7006. doi: 10.3892/ol.2018.8234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Eiro N, Carrión JF, Cid S, et al. Toll-Like Receptor 4 and Matrix Metalloproteases 11 and 13 as Predictors of Tumor Recurrence and Survival in Stage II Colorectal Cancer. Pathol Oncol Res. 2019;25(4):1589–1597. doi: 10.1007/s12253-019-00611-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pang L, Wang DW, Zhang N, Xu DH, Meng XW. Elevated serum levels of MMP-11 correlate with poor prognosis in colon cancer patients. Cancer Biomark. 2016;16(4):599–607. doi: 10.3233/CBM-160601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Delebecq TJ, Porte H, Zerimech F, Copin MC, Gouyer V, et al. Overexpression level of stromelysin 3 is related to the lymph node involvement in non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6(3):1086–1092. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tian X, Ye C, Yang Y, Guan X, Dong B, et al. Expression of CD147 and matrix metalloproteinase-11 in colorectal cancer and their relationship to clinicopathological features. J Transl Med. 2015;27(13):337. doi: 10.1186/s12967-015-0702-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.de Launoit Y, Chotteau-Lelievre A, Beaudoin C, Coutte L, Netzer S, et al. The PEA3 group of ETS-related transcription factors. Role in breast cancer metastasis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2000;480:107–116. doi: 10.1007/0-306-46832-8_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Qi M, Liu Z, Shen C, Wang L, Zeng J, et al. Overexpression of ETV4 is associated with poor prognosis in prostate cancer: involvement of uPA/uPAR and MMPs. Tumour Biol. 2015;36(5):3565–3572. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-2993-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yamamoto H, Horiuchi S, Adachi Y, Taniguchi H, Nosho K, et al. Expression of ets-related transcriptional factor E1AF is associated with tumor progression and over-expression of matrilysin in human gastric cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2004;25(3):325–332. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgh011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1 Table S1. Location and pathological tissue of each patient.

Additional file 2 Table S2. Observed mutations in APC,TP53 and KRAS genes.

Additional file 3 Figure S1. Relative expression of the ETV4 gene after its silencing in HT29 and SW480 CRC cell lines. The silencing was efficient with p < 0,0001.

Additional file 4 Figure S2. Apoptosis assay. The HT29 and SW480 cell lines did not show any changes in the apoptosis’ rates (A) and cell viability (B).

Additional file 5 Table S3. Enrichment of signaling pathways analysis.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.