Abstract

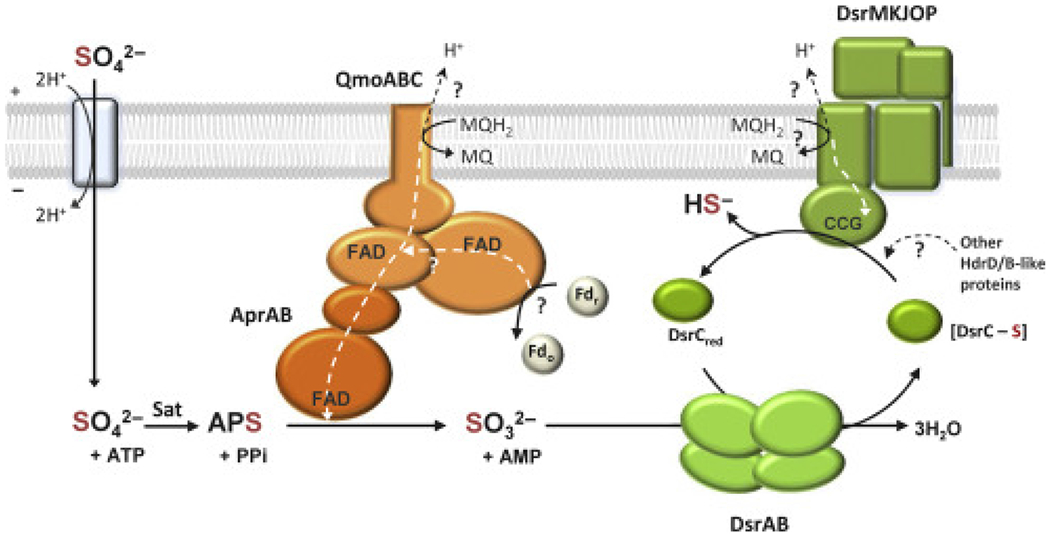

Heme-copper oxidases (HCO), nitric oxide reductases (NOR), and sulfite reductases (SiR) catalyze the multi-electron and multi-proton reductions of O2, NO, and SO32−, respectively. Each of these reactions is important to drive cellular energy production through respiratory metabolism and HCO, NOR, and SiR evolved to contain heteronuclear active sites containing heme/copper, heme/nonheme iron, and heme-[4Fe-4S] centers, respectively. The complexity of the structures and reactions of these native enzymes, along with their large sizes and/or membrane associations, make it challenging to fully understand the crucial structural features responsible for the catalytic properties of these active sites. In this review, we summarize progress that has been made to better understand these heteronuclear metalloenzymes at the molecular level though study of the native enzymes along with insights gained from biomimetic models comprising either small molecules or proteins. Further understanding the reaction selectivity of these enzymes is discussed through comparisons of their similar heteronuclear active sites, and we offer outlook for further investigations and areas of ongoing study.

1. Introduction

Respiratory metabolism is the cornerstone of cellular energy processes.1–3 To drive cellular energy production, organisms utilize a wide variety of so-called “terminal electron acceptors”4–8 that are often simple small molecules or ions that are prevalent throughout the organism’s immediate environment and possess thermodynamically favorable reduction potentials. For example, anaerobic respiration using sulfate (SO42−) as the terminal electron acceptor in oxidative phosphorylation can be traced to some of the earliest lineages of bacterial life.9,10 These organisms, and extant sulfate-reducing organisms, release sulfide (H2S) as a byproduct and play a crucial part in the biogeochemical cycle of sulfur.1,10 Similarly, the globally-relevant process of respiratory denitrification uses nitrate (NO3−) for this purpose, ultimately yielding gaseous nitrogen (N2) and water.11,12 Eventually, molecular oxygen (O2), an energetically potent terminal electron acceptor, became sufficiently abundant on the planet to allow for the developing prevalence of cellular aerobic respiration—reducing O2 to H2O.13,14 The greater amounts of energy that cellular respiration can provide to the organism is considered to be an underlying cause for the development of higher organisms.15,16

While these small molecules are good terminal electron acceptors for cellular energy processes, efficiently reducing them can be challenging due to high energetic barriers for their activations. To address this issue, nature has recruited metal ions as cofactors because they possess tuneable thermodynamic reduction potentials and electron configurations to catalyze the activation of these small molecules that cannot be achieved easily with nonmetals. Therefore, metalloproteins are ubiquitous components of cellular respiratory pathways and serve roles both in electron transfer (ET) processes and as catalysts for bond-breaking/bond-forming chemical transformations. These metalloenzymes have evolved to efficiently catalyze small molecule redox transformations, in many cases with high degrees of energy conservation and selectivity while avoiding the release of toxic or reactive intermediates. As a result, many different metal ions and coordination environments have been discovered in these proteins to perform a variety of reactions involved in cellular respiration. Even though the building-blocks for the construction of these metalloproteins are limited to 20 natural amino acids, a handful of naturally-derived organic cofactors (e.g. porphyrin), and Earth abundant metal ions—considerably less diverse than the vast number of building-blocks which can be used to prepare synthetic inorganic and organometallic compounds—metalloenzymes display remarkably high activity and efficiency while operating under relatively mild reaction conditions. The protein structures that produce these remarkable metal catalysts, each specialized for a particular reaction, are an inspiration to chemists interested in the development of effective catalysts relevant to the current needs of society.

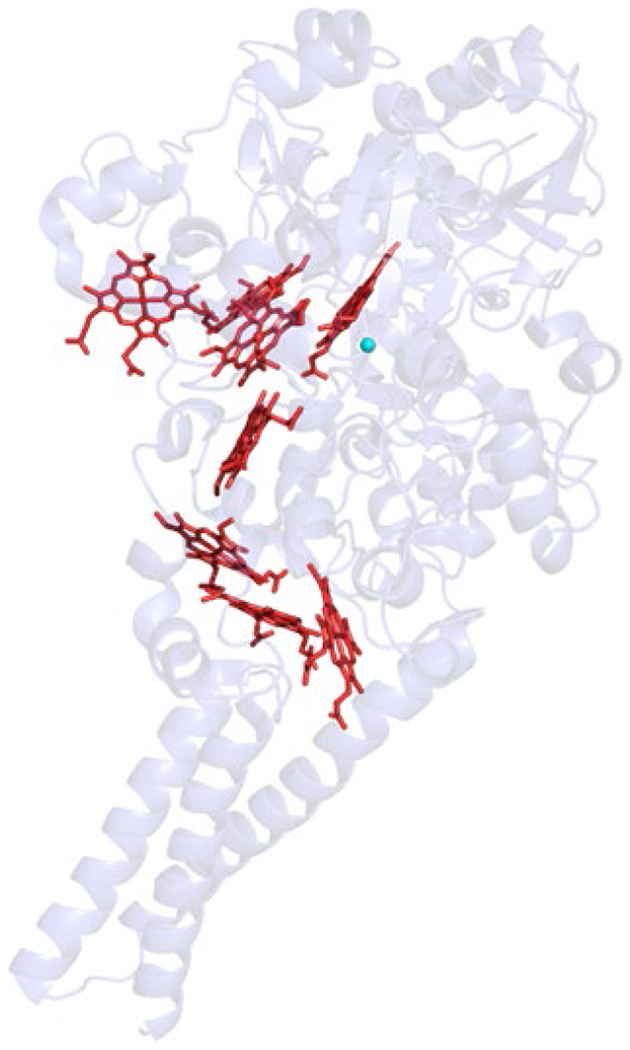

A type of reaction central to nearly all cellular respiratory pathways, including sulfate reduction, denitrification, and aerobic respiration, is multi-electron, multi-proton small molecule transformation. Most metalloenzymes that catalyze these reactions use multiple redox-active metal centers in close proximity within the enzyme active site (Figure 1). The precise reasons why these complex heteronuclear catalysts evolved for these reactions and how they carry out these complex reactions efficiently and selectively pose some of the greatest unknowns in biochemistry. Recent advances have begun to fill in many of the blanks through increasingly versatile and inexpensive molecular biology tools available today, along with the development and advancement of multiple computational, spectroscopic and crystallographic techniques, which have allowed more detailed studies of complex native enzymes than ever before. In parallel, numerous bio-inspired synthetic, small molecular model complexes, including functional catalysts, have been created to reconstruct the core features of these metalloenzymes. Their ability to go beyond the relatively confined space of biological coordination chemistry has allowed us to begin to understand the deeper underlying chemical principles at work within these complex metalloenzymes. In a complementary approach to studying native enzymes and their synthetic models, our lab and others have used small and robust proteins as scaffolds to design “biosynthetic” models, or artificial metalloenzymes (ArMs), to recreate the complex catalytic centers of native metalloenzymes from the bottom-up while preserving the advantages of facile design and stability inherent to biomimetic modelling.17–21 Biosynthetic modelling of metalloproteins has also been pursued through new-to-nature de novo designed protein scaffolds, further expanding the structural diversity of protein-based models.17,22–26 Both synthetic and biosynthetic models provide several opportunities to complement the study of native enzymes: targeted construction of minimal catalytic components have led to models that helped identify specific, local factors that lead to efficient bond activation and reactivity and these models have allowed for the isolation and characterization of catalytic intermediates whose presence in the enzyme mechanism is implied but has otherwise not been possible to directly interrogate in the native system. The variety of available functional groups, many of which are non-biological, has led to a number of probing, systematic studies. The approach to model native enzymes by redesigning smaller proteins has further provided experimental support for the catalytic roles of complex protein structures beyond the metal primary coordination sphere.

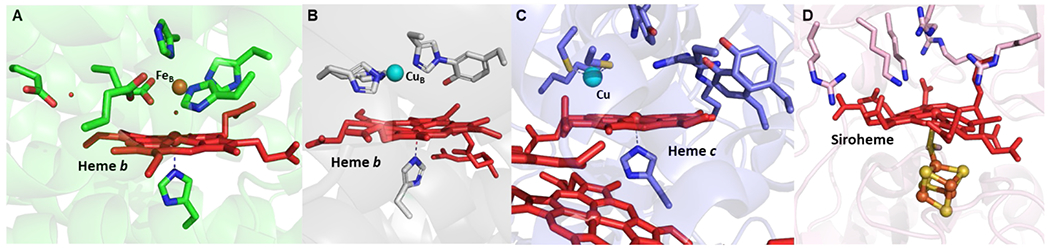

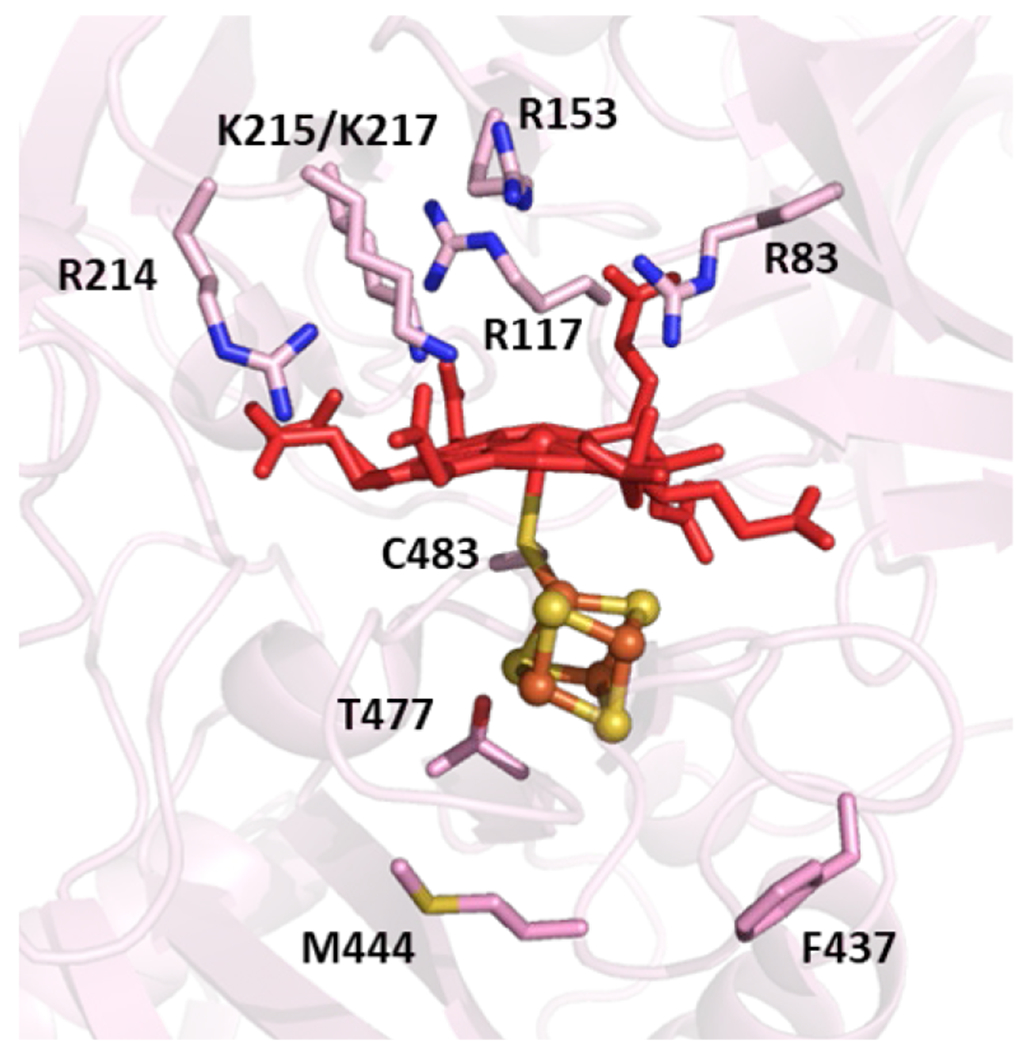

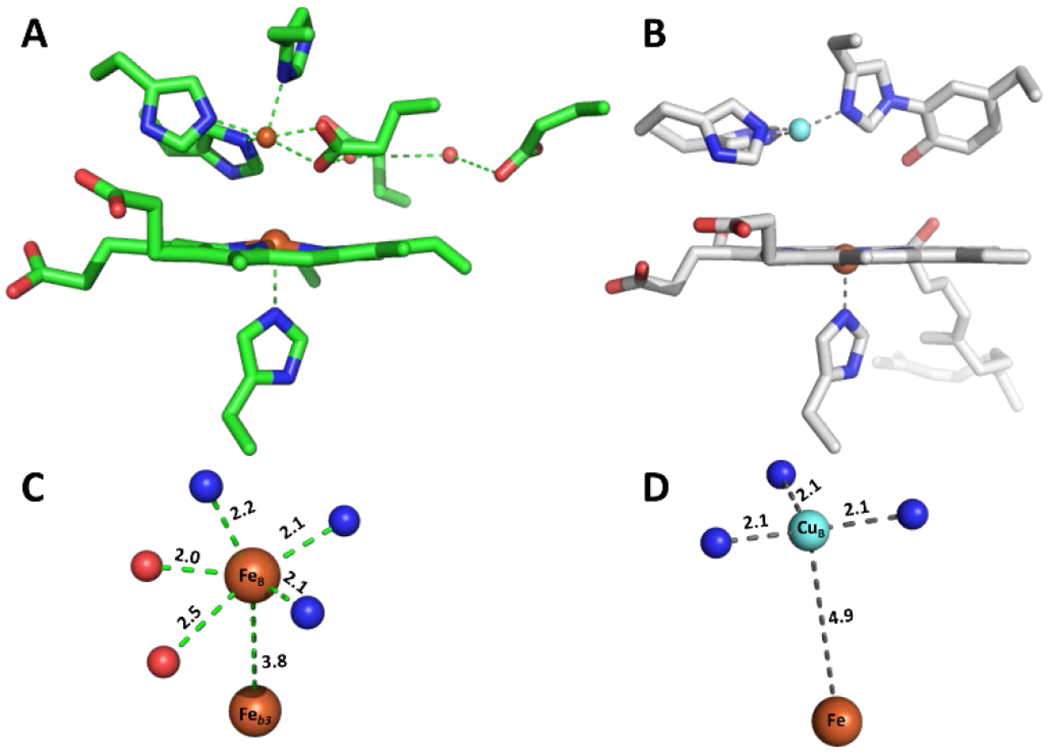

Figure 1.

Active site structures of heteronuclear metalloenzymes (A) NOR (PDB ID: 3O0R), (B) HCO (PDB ID: 5B1B), (C) Heme/Cu SiR (SiRA; PDB ID: 4RKM), and (D) siroheme-[4Fe-4S] SiR (PDB ID: 1AOP).

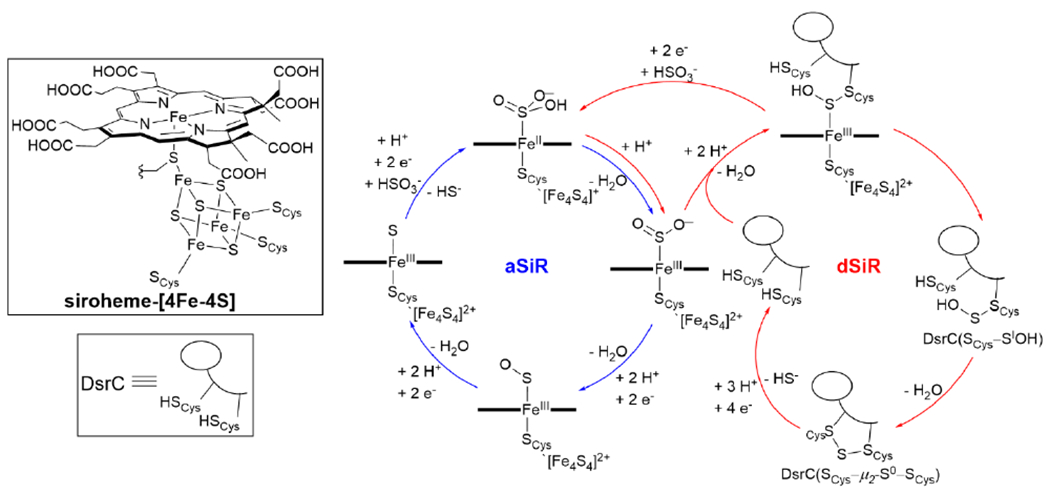

In this review we will focus on recent advances in our molecular understanding of the heteronuclear metallocofactor-containing nitric oxide reductase (NOR), terminal oxidase (heme-copper oxidase, HCO), and sulfite reductase (SiR), along with insights gained from the study of biomimetic transition metal complexes. Each of these enzymes catalyzes a key multi-electron reduction reaction relevant to their respective respiratory pathways in the cell: the 2 e− reduction of nitric oxide (NO) to nitrous oxide (N2O) by NOR, the 4 e− reduction of O2 to water by HCO, and the 6 e− reduction of sulfite (SO32−) to hydrogen sulfide (H2S) in SiR. Notably, these metalloenzymes share a number of structural similarities within their active sites and highlight the way similar building-blocks and catalyst design strategies can accomplish distinct chemical transformations. All three classes of proteins use a heme cofactor to bind and activate the substrate molecule. In the case of NOR and HCO, which are closely related proteins that fall within the same enzyme superfamily, their active sites display a neighboring nonheme metal center that participates in the reduction reaction. A recently determined structure of a multiheme class of SiR has shown a similar heme/nonheme active site structure, although little is currently known about the functional role of this nonheme metal. Regardless, another group of SiRs also utilize a heme cofactor, which is part of a different heteronuclear active site structure, by virtue of a covalent link to a [4Fe-4S] cluster. These native heteronuclear metallocofactor active sites and their biomimetic models have proved to be a challenging but fruitful area of study for structural and computational biologists, biochemists, spectroscopists, and synthetic chemists.

2. Heme-Copper Oxidase (HCO) and Related Biomimetic Models

2.1. The Active Site of Heme-Copper Oxidases.

Aerobic cellular respiration utilizes terminal oxidases, which couple the 4e− reduction of O2 to water with proton translocation, to generate potential energy in the form of a proton gradient that leads to ATP production by ATP synthase (eq 1).14,27

| (1) |

One of the most prevalent groups of terminal oxidases are integral membrane proteins present across all kingdoms of life collectively known as heme-copper oxidases (HCO). They belong to the heme-copper oxidase superfamily, which also include the heme/FeB-containing NOR enzymes (section 3). During O2 reduction, electron and proton transfer steps are highly regulated, which is achieved through precise interactions between the metallocofactors and residues in the proton transfer (PT) channel(s) located across different protein subunits. This synergy helps ensure that harmful, partially reduced oxygen species (PROS)–1e−-, 2e−-, and 3e−-reduced superoxide, peroxide, and hydroxyl radical, respectively–are not released while maintaining energy conservation necessary for proton translocation. HCOs are divided into three main types (A, B, and C), based on their subunit compositions and proton-pumping functions (Figure 2).14,28,29 HCOs are also divided into two distinct classes: one is quinol oxidase (QO) which obtain electrons from quinol, and the other is cytochrome c oxidase (CcO), which obtains reducing equivalents from cytochrome c.14 Due to the wide diversity of their protein structures, electron donors, proton pathways, and metallocofactors, the evolutionary lineage between members in the HCO superfamily remains challenging to fully elucidate.14,30,31

Figure 2.

Sub-classes of HCO protein superfamily. Figure adapted from ref32. Copyright American Chemical Society 2014.

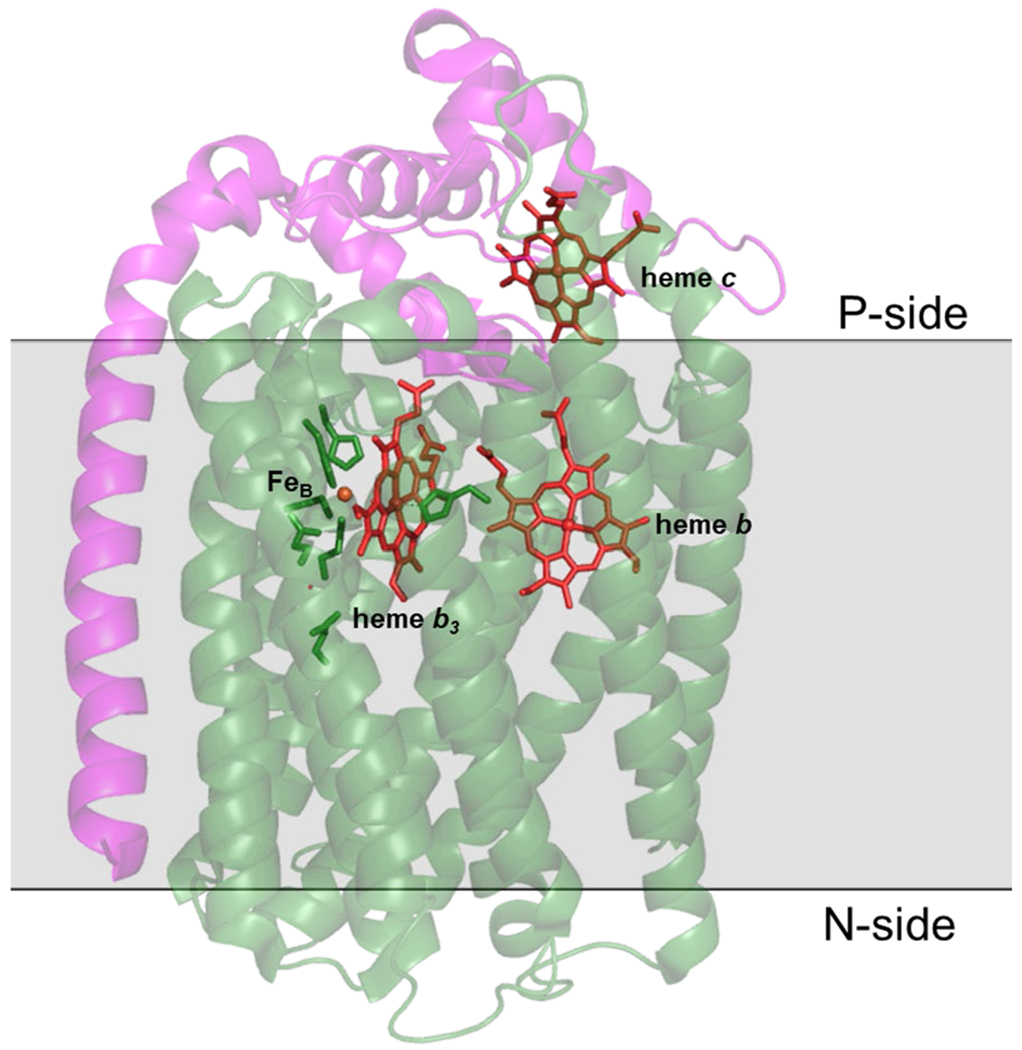

All HCOs share a similar subunit I, which contains the catalytic binuclear center (BNC) that is composed of a high spin heme and copper ion (CuB). Arguably, the most well-studied is the A1 subfamily, particularly aa3-type HCO that can be found in mitochondria, Rhodobacter sphaeroides, and Paracoccus denitrificans.14 HCOs from the B subfamily have been found mainly in archaea but some bacterial B-type HCOs have also been identified and characterized, including ba3 oxidases from Thermus thermophilus and Rhodothermus marinus.33 In A- and B-type CcO, electrons are transferred from cytochrome c to a CuA site in subunit II on the P side of the membrane (Figure 3). These electrons are then passed to a six-coordinate heme a in aa3 oxidase or heme b in ba3 oxidase, which are transferred to the BNC composed of the high-spin heme a3 or b3 and CuB. Other versions of A- and B-type HCOs contain a high-spin heme o3 cofactor in the BNC (Scheme 1).34 The C type HCO is comprised only of cbb3 oxidases, which have been purified from several species, including R. sphaeroides, Vibrio cholerae, Paracoccus denitrificans and Pseudomonas stutzeri.35–37 These enzymes are commonly expressed under conditions of low O2. Among the different types of HCOs, cbb3 oxidase has more in common structurally with bacterial NOR.31 Unlike aa3 and ba3 oxidase, cbb3 oxidase contains heme b3 at the BNC.27 These oxidases contain a subunit N, which is the central subunit containing the BNC, and either an O subunit which has one heme c or both O and P subunits where subunit P contains two heme c cofactors.38

Figure 3.

ET and PT Pathways in subunit I and II of bovine aa3 CcO (PDB ID 5B1B). The schematic diagram depicts chemical protons transferred to the BNC through the D and K pathways while pumped protons are translocated from N- to P-side of the membrane via the H pathway. HCO types without the H pathway are proposed to translocate pumped protons via spatial analogues of the D and K pathways near the BNC, and then to the P-side through a poorly understood PT pathway.

Scheme 1.

Observed metallocofactors in HCO and ET Pathway

Besides differences in their ET pathways, there is also a wide variation between the PT channel(s) among HCO families. Protons that are transferred from the N-side of the membrane to the BNC active site to form water from O2 are called “chemical” protons, while the remainder of protons are separately translocated to the P-side of the membrane to generate the so-called electrochemical gradient for ATP synthase, known as the “pumped” protons.35,36,39 Type A oxidases such as aa3 oxidase can have three PT pathways named D, K, and H pathways (Figure 3). The D and K pathways are named for the residues, Asp and Lys, respectively, which define these channels.28,33 The H pathway only exists in A type CcOs (not QOs), and a standing hypothesis is that this pathway serves as “dielectric well” to help compensate for the thermodynamically unfavorable ET from the P side of the membrane.40 Several articles and reviews have discussed the structure and potential roles of the H pathway.34,40–42 It has been suggested that the H pathway is responsible for translocating all the pumped protons in mammalian A type CcO, while the D and K channels transfer the chemical protons to the BNC.34,43–45 Bacterial A-type CcOs do not rely on the H pathway and it has been established that the K pathway transfers two chemical protons while D pathway is thought to transfer the remaining chemical and pumped protons.43 A recent mutagenesis study has also shown that S. cerevisiae mitochondrial CcO potentially use a similar D pathway for translocation of pumped protons.44 On the other hand, in the B and C type HCOs, including ba3 and cbb3 oxidase, only a single PT pathway is present, which spatially aligns with the A-type K pathway, and is responsible for transferring all of the chemical and pumped protons.28,38,46,47 It has been speculated that the single PT pathway in type B and C oxidases contributes to their lower proton pump stoichiometry, along with differences in ligand binding (O2, NO, CO, etc.) since the D pathway in aa3 oxidase overlaps with hydrophobic residues essential for O2 transfer to the BNC.33,35,48 Regardless of the type of HCO, pumped protons are transferred to a hypothesized “proton loading site” close to the BNC; the exact identity of this loading site is unknown, although it is speculated to be propionate A of heme a3 which receives protons from E242 (Figure 3); therefore, the precise PT pathway for pumped protons to enter the P-side is not currently well understood.49,50 Since this review focuses on insights gained from biomimetic models of native enzyme active sites, which is principally concerned with the efficient and selective O–O activation in HCO (see section 2.4), detailed discussion concerning the proposed mechanisms of the proton pumping activity of HCOs will not be included. Other recent reviews have extensively covered the proton pumping aspect of HCO.49–51

There are many reported structures of type A and B HCO.46,52–54 Currently, there is only one structure of a type C oxidase reported.38 All three types of HCO enzymes display a highly conserved BNC active site structure buried within the transmembrane domain of the catalytic subunit. The heme cofactor is bound by a single His residue, and the distal pocket contains the CuB center ~ 5 Å away, which is coordinated by three conserved His residues. Diffusion of O2 to the BNC has been studied crystallographically with bovine aa3 and Tt ba3 oxidase.55–57 By collecting X-ray diffraction (XRD) data of Xe-pressurized crystals of HCO, these studies demonstrate that O2 migrates through a hydrophobic channel in HCO enzymes (Figure 4) to reach the active site.

Figure 4.

XRD structure of Xe-pressurized cyrstals of HCO, showing the hydrophobic channel for O2 transfer. Figure adapted from ref. 55 Copyright American Chemical Society 2012.

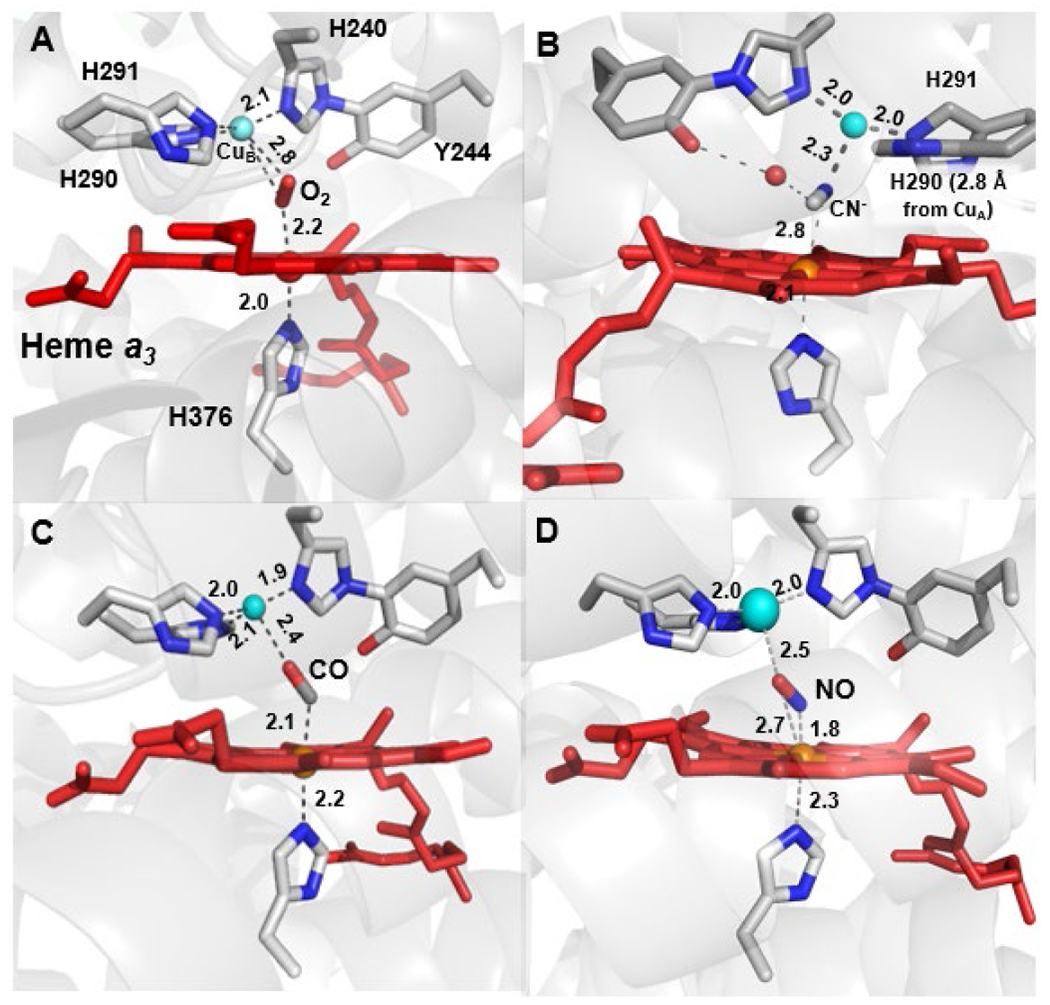

Structures of bovine CcO with various substrate analogues (NO, CO, CN−) suggest there may be functionally significant variation in CuB binding modes (Figure 5).58,59 Largely, the CuB center adopts a trigonal planar geometry in the absence of any ligand, or a pseudo-tetrahedral geometry when a ligand bridging to heme is present. Binding of NO to the heme a3 of bovine CcO has little effect on the Cu geometry; however, in one instance, CN− binding leads to dissociation of a His ligand with CuB and a pseudo trigonal planar geometry by binding to the cyanide nitrogen (PDB ID: 3AG4). Changes to the coordination of CuB have been implicated in modulating the reduction potential of the metal for ET during O–O cleavage or maintaining energy conservation during particular steps of catalytic turnover.58,60

Figure 5.

Structures of (A) O2- (PDB ID: 2Y69)-, (B) CN−- (PDB ID: 3AG4), (C) CO- (PDB ID: 5X1F), and (D) NO-bound (PDB ID 3AG3) forms of bovine HCO. The BNC in (A) is in the oxidized state while (B), (C) and (D) are in the fully reduced state.

Another notable feature in HCO is a His-Tyr crosslink–a covalent bond between one of the His residues that binds CuB and a functionally crucial Tyr residue. This Tyr residue serves as a proton and electron donor during catalysis. Small organic models of the phenol-imidazole crosslink suggest it raises the pKa and reduction potential of the Tyr phenol sidechain in HCO.61,62 Implications of the structural and electron donating effect of the cross-linked His to CuB coordination have also been considered.63 This residue is also part of the K PT channel (vide supra), and has H-bonding interactions with a water network in the BNC that interacts with the substrate O2, suggesting it has an important role in PT during turnover.33,58 The position of this Tyr residue in the polypeptide sequence is not conserved, however; C-type cbb3 oxidase displays a His-Tyr crosslink at a different position, where the Tyr is further away in sequence and located on a neighboring helix.38,63 A phylogeny study of HCO sequences has revealed groups of oxidases that lack Tyr at either of these two positions.64 Homology modelling of these sequences reveal two other possible sites near the BNC that can have Tyr residues, which may or may not be covalently linked to one of the CuB His residues. The observation of functionally conserved, but sequentially dissimilar Tyr residues in HCO is interesting from the perspective of understanding the evolution of HCOs.31

2.2. Other Oxidases that Reduce O2 to Water

There are a multitude of metalloenzymes that bind and reduce O2. Along with respiratory enzymes that utilize O2 as an electron acceptor, there are numerous enzymes that couple O2 reduction to the oxidation of organic substrates. Similar to HCOs, the large majority of these metalloproteins use Fe or Cu centers to activate O2. Covering the vast literature concerning these proteins is outside the scope of this review. Instead, we refer the reader to recent reviews that have focused on these other O2 activating metalloenzymes containing heme,65–67 nonheme Fe,68–70 and Cu32,66,71 active sites. This section will focus on metalloenzymes that selectively catalyze the complete 4 e− reduction of O2 to two molecules of water as their native reaction.

2.2.1. bd Oxidase.

These integral membrane proteins exist in a number of prokaryotes and are involved in O2 scavenging and respiratory pathways.72,73 Specifically, all known bd oxidases are quinol oxidases which belong to a family distinct from HCOs.72 These enzymes do not pump protons across the membrane, but are able to generate a proton gradient during O2 reduction by consuming protons from the N-side of the membrane, while oxidizing quinol reducing equivalents near the P-side of the membrane. The bd oxidase contains three heme cofactors, a six-coordinate heme b558 involved in ET, along with a high-spin heme b595 and a heme d (Figure 6A). The heme d cofactor binds to the protein through a weakly-coordinating Glu and displays high O2 affinity.74 Heme d is typically invoked as the site of O2 reduction; however, the high-spin heme b595 appears to be capable of reacting with O2 and other various ligands, leading some to propose it also plays a role in O2 activation.72,75 Flow-flash kinetics experiments of O2 reduction by bd oxidase are consistent with a mechanism similar to HCO (see section 2.3), with a notable difference that there is evidence for an observable FeIII-OOH (hydroperoxide) intermediate.76

Figure 6.

Active site structures of non-HCO oxidase enzymes (A) bd oxidase from Geobacillus thermodenitrificons (PDB ID 5IR6), (B) alternative oxidase (AOX) from Trypanosoma brucei (PDB ID 5ZDP) with ferulenol bound, (C) a flavodiiron oxidase (FDP) from Giardia intestinalis showing its diiron binding site (PDB ID 2Q9U), and (D) laccase, a multi-copper oxidase (MCO) from Trametes versicolor containing a T1 and a trinuclear copper center (T2 and T3 Cu) (PDB ID 1GYC).

2.2.2. Alternative Oxidase (AOX).

These membrane-associated enzymes are found in all domains of life and are closely linked to aerobic respiration, although these oxidoreductases are distinct in being incapable of generating any electrochemical gradient. These enzymes are thought to have various regulatory roles: for example, heat generation in tissue, metabolic homeostasis, defense against oxidative stress, and regulation of cellular signaling pathways.77,78 AOX contain a diiron active site (Figure 6B), which has been unambiguously confirmed recently by the first reported crystal structure.79 The proposed O2-activating mechanism is similar to other carboxylate-bridged diiron proteins, and also shares some features reminiscent to HCO, like a universally conserved Tyr residue near the binuclear active site, which may serve as an electron donor during turnover.80

2.2.3. Flavodiiron Protein (FDP).

FDPs, like the HCO superfamily, are a large family of metalloproteins that catalyze either O2 or NO reduction.81–83 Many FDPs are capable of catalyzing both of these reactions with nearly equivalent activities, while some appear to be selective for one reaction. FDP are globular proteins typically found in anaerobic organisms and are thought to play a role in O2 detoxification. Some FDPs have also been identified in photosynthetic cyanobacteria and are involved in regulating the pool of photosynthetic reducing equivalents under changing light conditions.81,84 Like AOX, the FDP active site comprises a carboxylate bridged diiron center (Figure 6C). Crystal structures of A-type FDPs shows that the diiron metal center is on the opposite end of the flavin mononucleotide cofactor. In order to maintain close proximity for efficient electron transfer, the monomers can form dimer pairs in which the C-terminus of one monomer interacts with the N-terminus of the other.83,85

2.2.4. Multicopper Oxidase (MCO).

MCOs are a large family of enzymes that couple the reduction of dioxygen to water with the oxidation of organic molecules or metal ions.32,86 The site of substrate oxidation is distinct from the O2-reducing site, making MCOs unique from most enzymes that couple O2 reduction to substrate oxidation. MCOs have a mononuclear type 1 (T1) Cu center, which serves as the primary electron acceptor from the substrate molecule, along with the O2-reducing trinuclear copper center (TNC), comprised of a binuclear type 3 (T3) site and neighboring type 2 (T2) Cu (Figure 6D). Complete O2 reduction occurs from the fully reduced form (four CuI), which cleaves the O–O bond in two steps, forming a transient peroxy intermediate (PI), followed by the so-called native intermediate (NI).87 In the presence of substrate, the NI form is re-reduced and H2O is released. One turnover of the O2 reduction catalytic cycle leads to multiple turnovers of substrate oxidation.

2.3. Mechanism of O2 Reduction by HCOs.

Although certain aspects of the O2 reduction mechanism by HCO remain unclear, a general consensus of the basic steps has emerged through extensive structural and spectroscopic studies of bovine aa3 oxidase and other HCOs (Scheme 2). In this section, we will summarize the mechanistic steps of O2 reduction by bovine aa3 oxidase, along with discussion of some remaining mechanistic uncertainties. For more detailed information of the spectroscopic and kinetics data pertaining to our understanding of the mechanism of O2 reduction and proton translocation in HCO, we refer the reader to other recent reviews.34,49,88 In brief, much of the mechanistic insight into O2 reduction at the BNC comes from time-resolved spectroscopies, including resonance Raman (rR) and UV-Vis absorption. One particular method that has been key to our understanding of the mechanism is flow-flash spectroscopy.34,49,89,90 This technique starts with a reduced, or partially reduced, CO-bound HCO in O2 saturated buffer. Time-resolved spectra of O2 reduction are obtained upon photolysis of the CO ligand from the BNC. A drawback of this technique is that it relies on fast dissipation of CO from the active site, which happens to be the case for bovine aa3 oxidase but not all HCOs.91 More recently, analogous experiments have been performed without CO, using a photolabile O2-carrier, which have determined an overall identical O2-reduction process.92

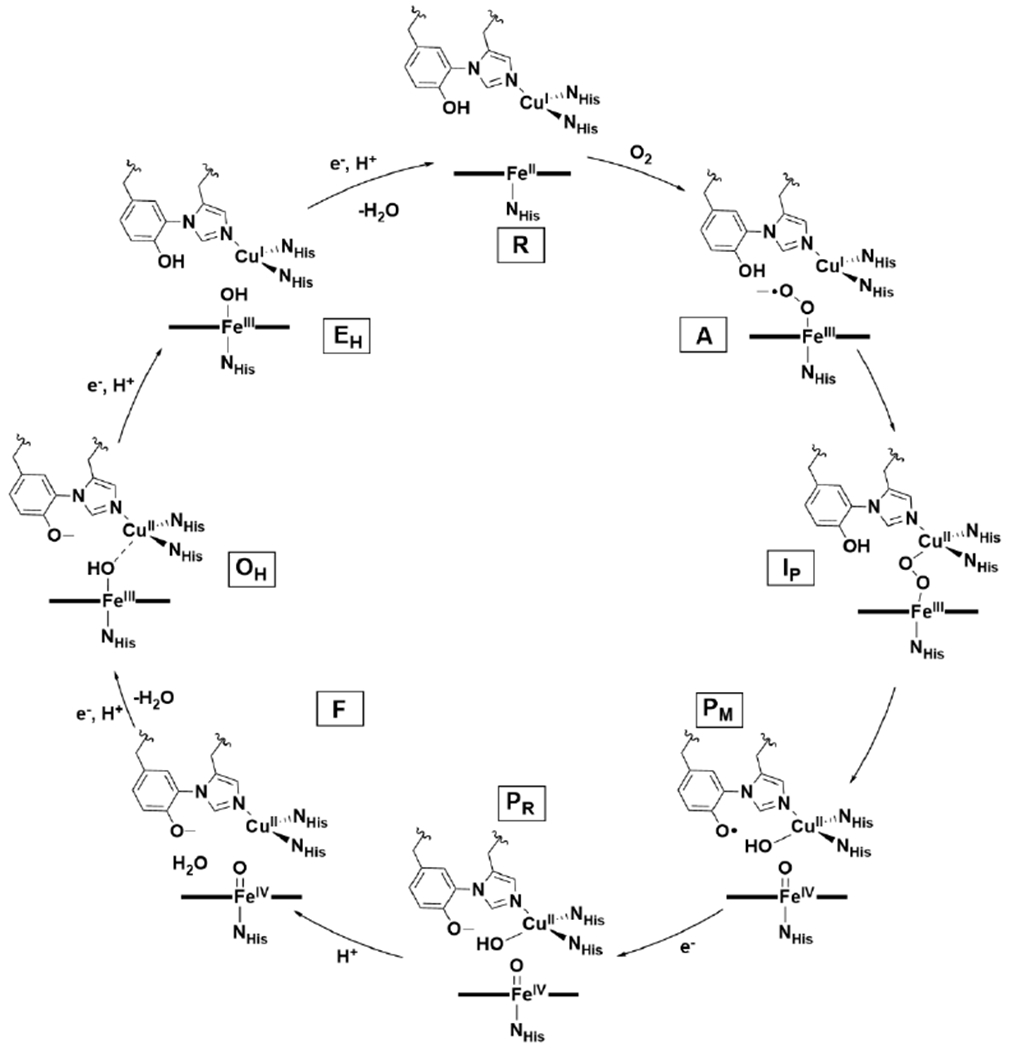

Scheme 2.

Proposed Mechanism of O2 Reduction by HCO.

2.3.1. O2 binding in HCO.

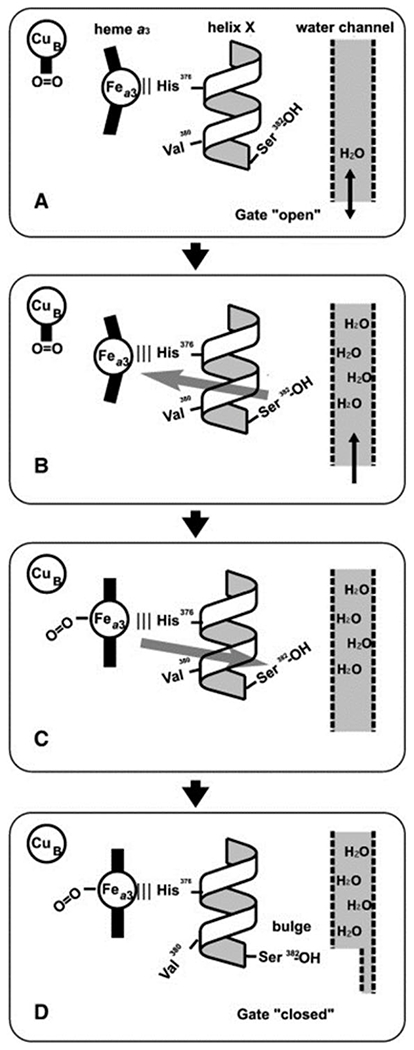

In flow-flash experiments with fully reduced bovine aa3 oxidase (R), the photolabile CO leaves with an apparent lifetime of ~1 μs, and the process of O2 binding can be observed with a lifetime about an order of magnitude greater, corresponding to a rate constant of ~108 M−1 s−1.90 In the absence of O2, CO still dissociates from the BNC relatively quickly but heme a3 will rebind exogenous CO after tens of milliseconds.93 Time-resolved vibrational spectroscopic studies reveal formation of a transient CuB–CO adduct, concomitant with protein conformational changes that affect the ligand affinity of heme a3, along with solvent access to a nearby water channel.91 Based on these observations, it is proposed that CuB serves as the initial site of O2 binding, which is coupled to protein conformational changes that ensure that there is no back-flow of four proton equivalents, before O2 is transferred and reduced at heme a3 (Figure 7).93

Figure 7.

Proposed mechanism of gated O2 binding to BNC with protein conformational changes. (A) O2 binds initially to CuB since the conformation of helix X lowers the O2-affinity of Fea3. The neighboring water channel is based on the helix X conformation. (B) Ser382 is proposed to act as a sensor of H2O and, once it hydrogen bonds with the water channel, it leads to a change in protein structure which increases Fea3 O2-affinity through changes to helix X and the Fe-His376 bond (gray arrow). (C) In this manner, the O2-affinity of Fea3 is highest when enough H2O is present in the water channel. Ligand binding to Fea3 leads to further changes to helix X (gray arrow): a ‘bulge’ conformation on Val380 shifts to Ser382 ‘closing’ the water channel (D).Figure adapted from ref. 93 Copyright Elsevier 2015.

2.3.2. O–O Cleavage Steps (Oxidative Phase‡).

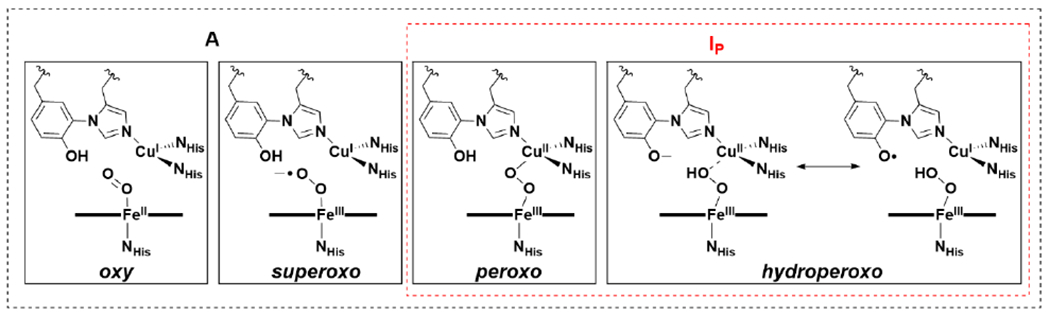

After O2 binding, the next stage of the HCO mechanism is complete O–O bond cleavage, which is known as the oxidative phase of the catalytic cycle.66,94 Coordination of O2 to reduced heme a3 leads to a species with an O2-sensitive rR signal at 571 cm−1, which is characteristic of the so-called A state.34 This rR peak is indicative of the Fe–O stretching vibration (νFe–O) of an end-on Fe–O2 species, but the structure can be Fea3II–O2 (oxy), Fea3III–O2− (superoxo), Fea3III–O–O–CuII (peroxo), or Fea3II–OOH (hydroperoxo) (Scheme 3). The oxy or superoxo assignments for the A state have been favored, due to its similar νFe–O to oxymyoglobin (569 cm−1)—an end-on FeII–O2 or FeIII–O2− hemoprotein;34 however, vibrational studies of heme model complexes are consistent with the peroxo or hydroperoxo forms being equally plausible.66

Scheme 3.

Possible Structures of A and IP Intermediates.

The intermediate of the A state decays forming a so-called P state intermediate with a process lifetime of 32 – 40 μs. It was named the P state because it was initially thought to contain a peroxide; however, rR with isotopic labeling ruled this possibility out. In fact, spectroscopic data is consistent with complete O–O bond cleavage at this stage, to yield an Fea3IV=O/CuII–OH/Tyr-O• species (PM state).34 The exact formulation of the P state depends on whether O2 is introduced at the fully reduced (R) state, or the two-electron reduced state (where CuA and heme a have no reducing equivalents to transfer to the BNC). When heme a is reduced, Tyr-O• is not observed in the P state, instead heme a is oxidized and Tyr is anionic (PR state). Therefore, there is uncertainty whether the PM state is a relevant catalytic intermediate, but the answer likely depends largely on the specific physiological concentrations of O2 and reducing equivalents in vivo.95 Evidence for the relevance of the Tyr-O• in the HCO mechanism has only been indirectly supported through an iodine radical trapping experiment.96 The PM state is EPR silent;49 however, treatment of oxidized bovine aa3 oxidase with H2O2 produces an intermediate that bears weak EPR signals consistent with a delocalized radical on Tyr244, Trp236, and Tyr129, supporting the notion that a Tyr-O• is a feasible intermediate in HCO during turnover.97

No other intermediates have been observed during the A to P state transition, although often a transient peroxo-containing state, IP, is invoked as a logical species between these intermediates.49,66,98 The exact nature of this peroxo intermediate is debated, specifically whether CuB binds to the distal oxygen, and whether this oxygen is protonated (Scheme 3). Computational studies suggest proton transfer is necessary to lower the barrier to O–O bond cleavage.99,100 Numerous crystallographic studies of HCO enzymes have purportedly isolated peroxo complexes within the BNC, which would correspond to this IP state, initially casting doubt on its catalytic relevance; however, analysis of these structures by Adam et al. have identified inconsistencies of the proposed peroxo assignments from a general coordination chemistry perspective in all but one of these structures, warranting caution in taking these HCO structure assignments at face-value.66 Numerous models of HCO display observable bridging peroxo-intermediates, FeIII–O22−CuII, and their relevance to O–O cleavage processes are further discussed in section 2.4.

2.3.3. Reductive Phase.

The remaining steps of the catalytic cycle involve transfer of protons and electrons to regenerate the R state. Each of these steps in the ‘reductive phase’ are coupled to a proton translocation (for the A type oxidases), which is discussed more extensively elsewhere.34,49–51 Single electron injection experiments have been useful for studying the processes of this phase and these studies conclude that the intermediates in the reductive phase proceed through mostly the same steps: reduction of heme a, followed by proton transfer to BNC, which raises the potential of heme a3 to allow for reduction of the active site.34,101 Studies of the mechanism of proton pumping by type A oxidase suggests it is triggered by the oxidation of heme a, which occurs four times during the reductive cycle, and based on the general principle of Coulombic balance of the electron injection into the BNC at a nearby “proton loading site” (Figure 3).49,50,102 This process is separate from the transfer of protons to the BNC to produce water. The protons that are used to form H2O are denoted “chemical protons”, and, for the remainder of this discussion, only the chemical protons will be considered.

In the PM state, the BNC is fully oxidized, which, in the presence of a reducing equivalent from heme a, will instead rapidly form the previously discussed PR state. Transition from the PR to the F state occurs through transfer of a proton, leading to formation of a BNC structure of Fea33IV=O/CuBII-OH2/TyrO−. Another series of electron and proton transfers produce the fully oxidized (OH) state of HCO. This state is poorly understood due to the lack of direct experimental data for it. It is known that the OH state structurally differs from the as-isolated fully oxidized HCO state that can be structurally and spectroscopically characterized (O) since the O state has a reduction potential too low for the energy conservation function of HCO to be catalytically relevant.103,104 Computational studies of HCO suggest potential structures of OH are Fea3III–OH---CuBII/TyrO−, Fea3III–OH/CuBI/TyrO•, or Fea3III–μ2–O–CuBII/TyrOH (Scheme 4).105,106 It is hypothesized that the OH state readily converts to O under conditions where reducing equivalents are limiting. Theoretical studies suggest either proton transfer105,107 or some other structural rearrangement, like change in metal coordination number,99,106 is responsible for the lower reduction potential in O. For further discussion of the O/OH states, we refer the reader to recent comprehensive reviews of HCO.49,66

Scheme 4.

Possible Structures of the High Potential OH and Lower Potential O States in HCO.

Transition from OH to the partially reduced (E) state has been studied through electron injection experiments with P. denitrificans aa3 oxidase, with reduction and proton translocation occurring on the sub-millisecond timescale.104,108 The exact structure of the E state is unknown, but proposed to be Fea3III–OH/CuI/TyrOH, based on the reduction potentials of each redox active center in the BNC.66 The final E to R state conversion has also been examined with Pd aa3 oxidase, through two-electron reduction of the F state with CO, showing a similar series of steps as the other protonation/reduction/proton translocation steps in the reductive phase.34,109

2.4. Insights Gained from Biomimetic Models of HCO.

HCOs have been studied structurally and mechanistically for several decades and these studies have helped establish an overall view of the H-bonding network at the BNC, the ET pathway that carries electrons to the active site, and the PT channel(s) that transfer protons from the N-side of the membrane towards the BNC, and across the membrane to the P-side. Despite this progress, many aspects of the structural features responsible for such an efficient and selective reduction of O2 to water are still not fully understood (see section 2.3) because it is quite challenging to purify and study these megadalton-sized membrane proteins with multi-domain structures. There are structural features of HCO that are hypothesized to be essential but are difficult to directly interrogate due to the limitations of site-directed mutagenesis using just 20 natural amino acids. In addition to these substitutional limitations, mechanistic studies are also limited to available spectroscopy or crystallographic techniques compatible with these membrane-bound proteins. Furthermore, it can be difficult to capture and study intermediates in HCO due to presence of spectroscopic features of other cofactors that may interfere or even dominate those of BNC where the O2 reduction occurs. These challenges motivate researchers to prepare biomimetic models of HCO as a means to gain deeper insight into the O2 reduction process by this enzyme. These models are much smaller, and can be easier to study because they are free of other cofactors. In addition, it is possible to introduce non-native metal ions or ligands in these models, to probe the roles of each functional group more systematically.

A recent review comprehensively covers studies of synthetic Fe/Cu complexes relevant to HCO and other O2-reducing metalloenzymes.66 The goal of this section is to provide an overview of how these models have helped our understanding of the underlying structural features of native HCO relevant for efficient and selective O2 reduction. Specifically, we will focus on biomimetic studies relevant towards O2 binding, O–O cleavage, and catalytic dioxygen reduction.

Many approaches to mimicking the heme/Cu active site structure of HCO have been employed.19,66,110,111 One is to chemically synthesize heme and Cu complexes separately and then combine them in the presence of O2 or H2O2. This approach has been useful for understanding how the coordination of Fe and Cu affect the structure and stability of reduced O2 intermediates. A notable recent example is the preparation of a “naked” copper-heme peroxo complex, which can serve as a starting point to generate a variety of heme-Cu assemblies.112 A second approach is the synthesis and study of tethered heme/Cu complexes. While most heme/Cu complexes are highly reactive towards O2, and require low temperatures for spectroscopic study, one tethered heme/Cu-peroxo complex has been synthesized which is stable enough to be structurally characterized.113 These systems have also been applied to electrocatalytic O2 reduction reaction (ORR), which has been a useful way to interrogate O2 activation.114–116 Lastly, another approach to model the HCO active site is to use a smaller and robust protein, such as sperm whale myoglobin (swMb), as a scaffold to engineer structural features which mimic those of HCOs. This approach, called biosynthetic modelling, can take advantage of the well-defined protein scaffolds to introduce amino acids in the secondary coordination to probe the roles of weak non-covalent interactions, such as hydrogen bonding networks involving water, more precisely which facilitates systematic study of their structure-property relationships.117–119

2.4.1. O2 Binding of Biomimetic HCO Models.

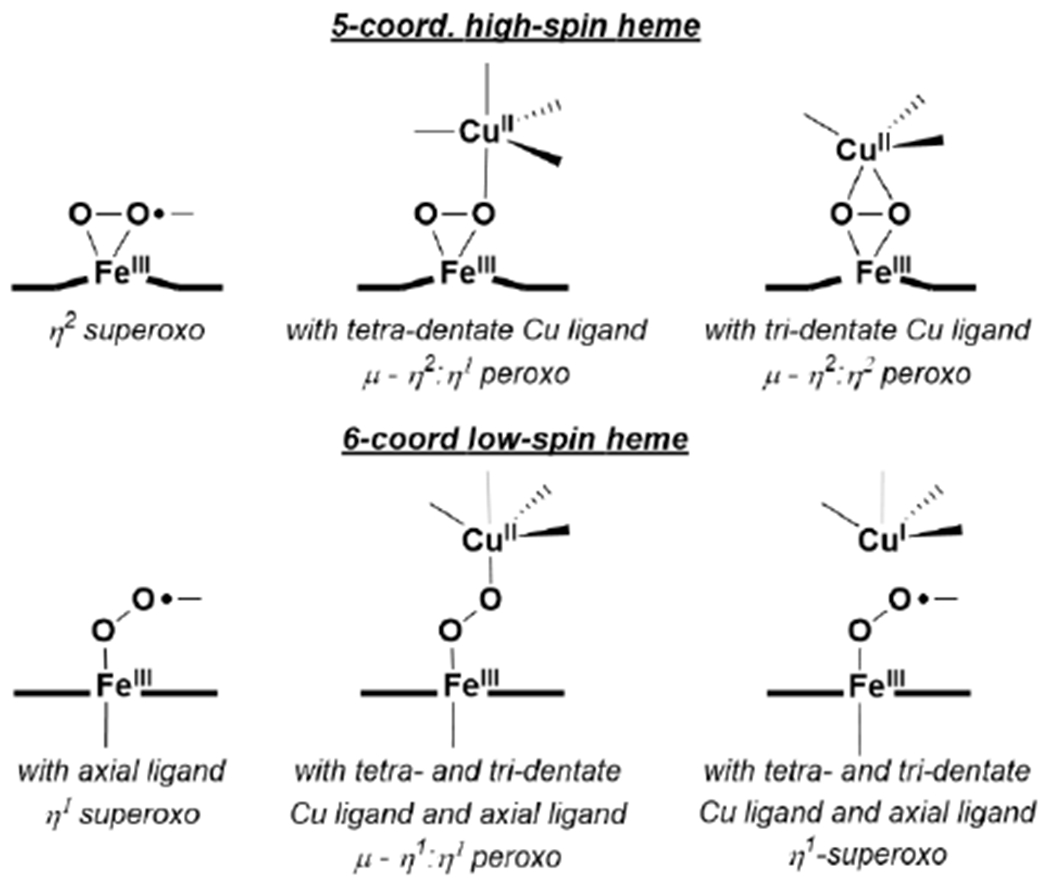

Studies of simple synthetic Fe porphyrin complexes show that reactions with O2 are commonly encountered in the reduced FeII state.66 The greater propensity of small molecule complexes towards intermolecular reactions often leads to formation of unreactive bridging-oxo complexes with sterically unencumbered porphyrins ((porph)FeIII–μ2–O–FeIII(porph)). Reactivity with O2 at a single Fe site has been examined through the use of sterically demanding porphyrins, to disfavor dimerization, along with the use of cryogenic temperatures to stabilize the early Fe–O2 intermediates. These studies reveal that O2 readily reacts with FeII and typically yields a side-on or end-on FeIII–O2−, depending on whether a trans axial ligand is present. In the presence of CuI, further activation of O2 is often observed, leading to bridging-peroxo intermediates (FeIII-(O22−)-CuII) (see section 2.4.2) (Scheme 5).

Scheme 5.

Characterized Synthetic Fe and Fe/Cu O2 Species Relevant to HCO.

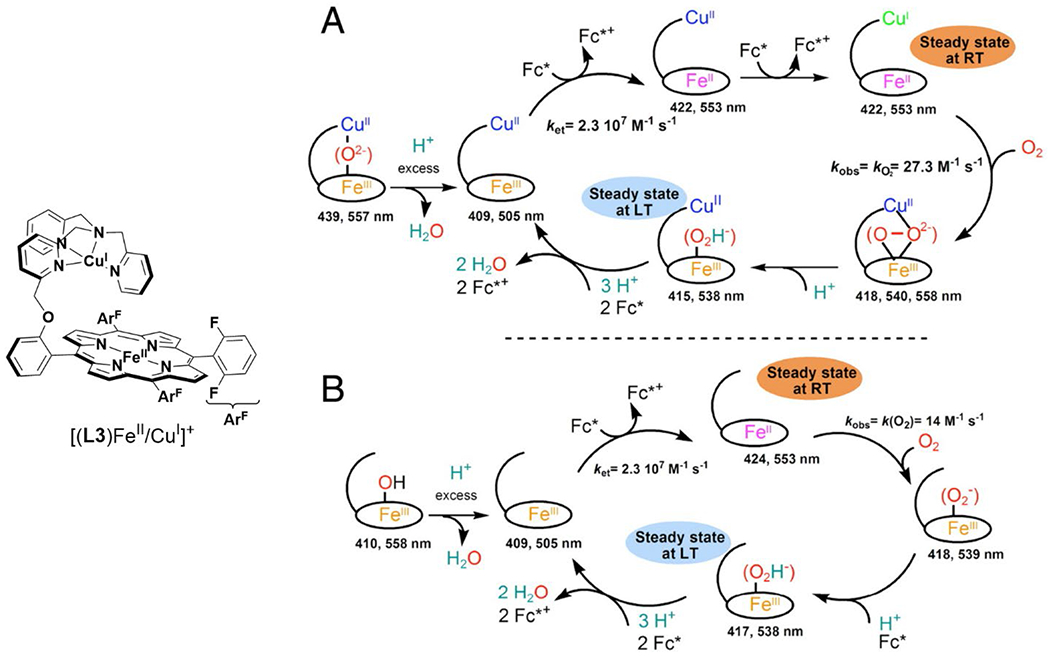

Tethered heme/Cu ligand scaffolds have been useful tools to compare the effect of Cu on O2 binding, since the Fe porphyrin can be prepared with or without the nonheme metal. For example, Collman et al. have reported a study of (L1)FeII and [(L1)FeII/CuI]+, which both form an FeIII–O2− upon reaction with O2 (Scheme 6).120 With CuI, irreversible binding of O2 occurs at room temperature, and the superoxo complex is stable to multiple degassing freeze-pump-thaw cycles. On the other hand, the Fe-only complex only binds O2 once cooled −60 °C. Related model complexes that are able to electrocatalytically reduce O2, [(L2)FeII/CuI]+ and (L2)FeII, display rate limiting O2 binding.121 Further study of the L2 system showed that ZnII has a similar effect as CuI on the rate constant of O2 binding (kon). Interestingly, the corresponding kon for the Fe-only complex was higher, but also highly sensitive to the presence of H2O, which inhibits O2 binding.122 Halime et al. reported a HCO model system, comprised of a tethered high-spin Fe porphyrin and appended Cu, [(L3)FeII/CuI]+, and its Cu-free form, (L3)FeII, are competent for O2 reduction catalysts (Figure 8).123 The rate limiting step of O2 reduction of both complexes is O2 binding at room temperature, and the ORR rate of [(L3)FeII/CuI]+ is higher than (L3)FeII under these conditions. At low temperature, O–O cleavage is the rate limiting step and there is no difference in rate between [(L3)FeII/CuI]+ and (L3)FeII. These results are consistent with Cu principally promoting O2 binding in this system, but having a negligible role in the subsequent O–O bond cleavage.

Scheme 6.

Tethered Heme/Cu Complexes Which Display Effect of Nonheme Metal on O2 Binding Reported by Collman et al. 120,121

Figure 8.

Proposed mechanisms of homogenous catalytic O2 reduction by (A) [(L3)FeII/CuI]+ and (B) (L3)FeII. Mechanism reproduced from ref. 123 Copyright National Academy of Sciences 2011.

The Lu group has used a rationally-designed mutant of sperm-whale myoglobin (Leu29His, Phe43His swMb; CuBMb) to model aspects of the BNC structure in HCO (Figure 9). By incorporating different heme cofactors into CuBMb, the influence of heme reduction potential on O2 binding was investigated.119 Both the kon and koff O2 binding rate constants increase with higher heme reduction potential, but koff displays a steeper dependence on potential, thus making the O2 affinity decrease overall. The presence of a nonheme metal also leads to higher O2 affinity, based on studies using AgI as a redox-inactive analogue of CuI.124 A related biosynthetic protein (Leu29His, Phe43His, Val68Glu swMb; FeBMb), that differs by the presence of a coordinating Glu residue to the nonheme metal, demonstrate that the Lewis acidity of the nonheme metal impacts O2 binding. The rate of formation and stability of oxyheme species was shown to depend on the identity of the nonheme metal (FeII, CuI, CoII, MnII, and ZnII), and could be directly compared when the nonheme metal was not able to be oxidized.117,118

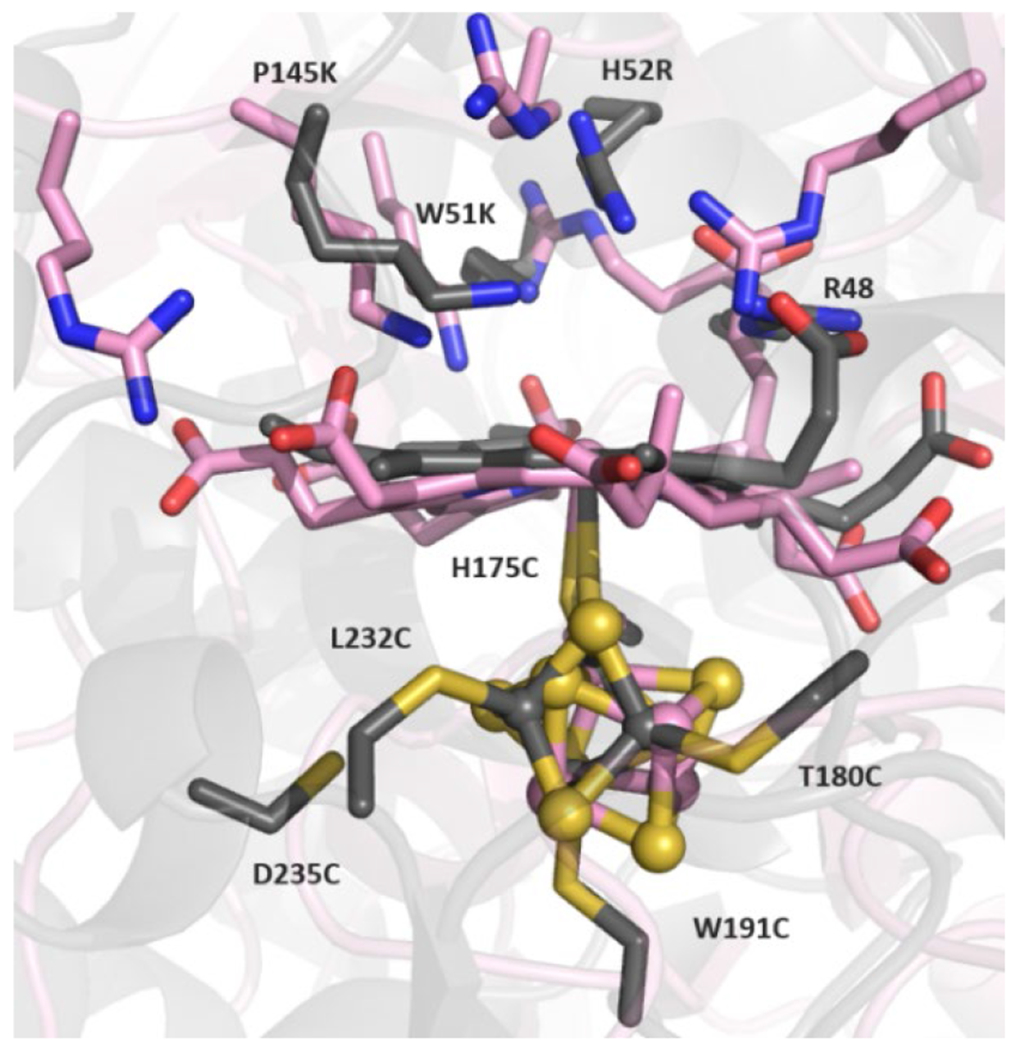

Figure 9.

Overlay of structure of Phe33Tyr CuBMb (magenta) with HCO active site (white).

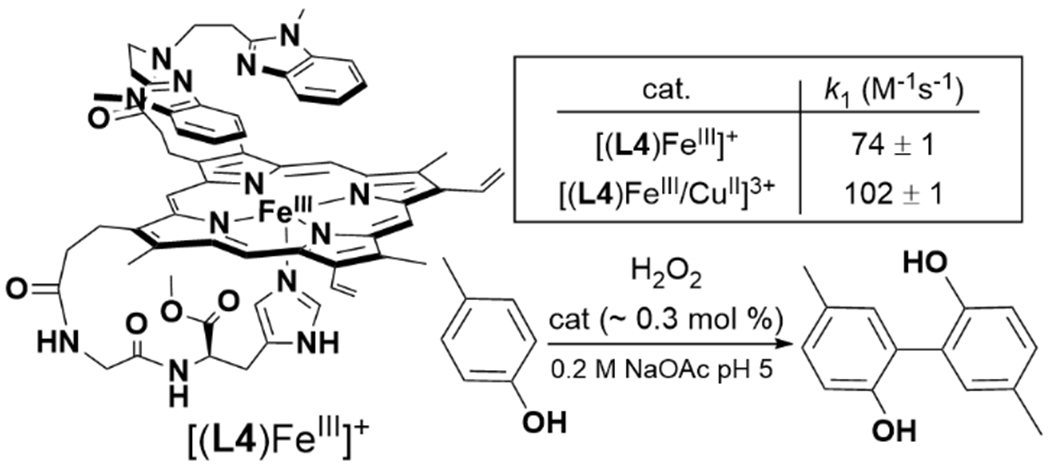

In native HCO, insight into the effect of CuB on O2 binding are informed by CO photolysis studies (see section 2.3.1), which reveal that when CO dissociates from heme a3 it transiently binds to CuB. This is thought to model, in reverse, the steps of O2 binding to the BNC active site. Similar studies have been carried out with biomimetic model complexes, which generally display this same property as the native enzyme.125–128 Other examples of model substrate binding studies include the [(L4)FeIII/CuII]3+ complex reported by Dallacosta et al., which displays a fivefold increase in azide binding affinity relative to [(L4)FeIII]+ (Scheme 7).129

Scheme 7.

Protoporphyrin IX-Derived Tethered Heme HCO Model Complex and Catalytic H2O2-mediated para-Cresol Oxidation.129

2.4.2. O–O Activation and Cleavage.

Direct studies of the effect of CuI on the properties of the initial heme-O2 intermediates are challenging, due to their propensity for oxidation of CuI and formation of bridging-peroxo complexes. As previously mentioned, examination of redox-inactive metals in place of CuI has been useful for probing the early stages of O2 binding and activation. In FeBMb, increased Lewis acidity of the nonheme metal increases the observed νFe–O of the oxyheme, which indicates a strengthened Fe–O interaction, and subsequent weakening of the O–O bond.118 Only a few stable FeIII-O2−/CuI HCO model complexes have been characterized, although short-lived Fe-superoxo species have been observed in stopped-flow kinetic studies of FeIII–(O22−)–CuII formation.130 The previously discussed picket-fence porphyrin complex L1 with Fe and Cu forms a stable FeIII-O2−.120 Studies of the corresponding Co-porphyrin complex with an empty distal pocket, or with nonheme CuI, CoII, or ZnII, show that these nonheme metals have only a small effect on the νO–O of the CoIII–O2−.131 In an intriguing example of a FeIII-O2−/CuI complex, Liu et al. reported that this species forms in [(L5)FeII/CuI]+ through a transient bridging-peroxo intermediate, seemingly the reverse of the formation pathways of a majority of FeIII–(O22−)–CuII complexes (Scheme 8).132 Two factors were proposed to be crucial for the shift in equilibrium towards FeIII-O2−/CuI with L5: (i) the ‘push’ effect of the axial imidazolyl weakens the binding interactions between Cu and the peroxide and (ii) the relative order of reduction potentials of Fe and Cu in this system thermodynamically favor CuI. This conclusion is corroborated by a report of a stable peroxide in a related system that bears no heme axial ligand, which would both raise the heme potential and remove any ‘push’ effect.133

Scheme 8.

Formation of FeIII-O2− Through a Transient FeIII–(O22−)–CuII. 132

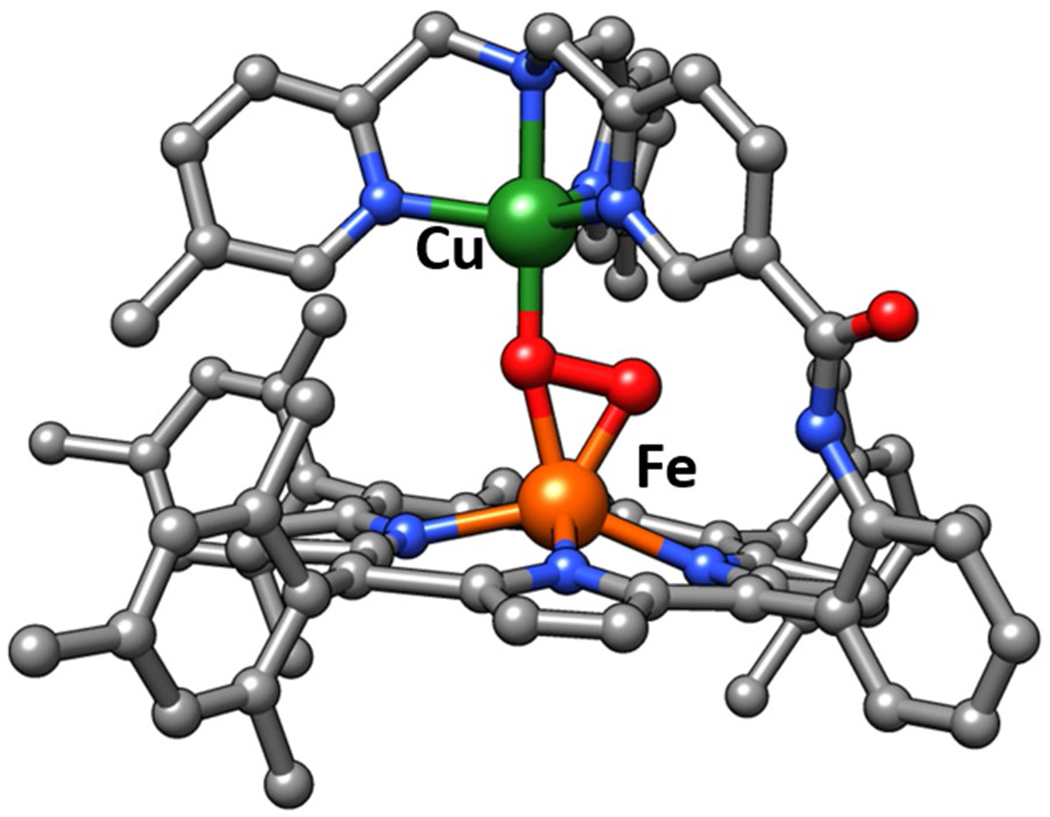

Numerous studies of biomimetic FeIII–(O22−)–CuII intermediates have been performed to gain a deeper understanding of how the coordination environment of the metals influence the binding and reactivity of the peroxide moiety.66,130 For example, the properties of a series of (L)(L6)FeIII–(O22−)–CuII(L’) complexes were investigated, where the presence of an axial ligand (L = DCHIm [1,5-dicyclohexylimidazole] or nothing) and chelating ligand to Cu (L’ = TMPA [tris(2-pyridylmethyl)amine] or AN [bis(3-[dimethylamino]propyl)amine]) had significant impact on the peroxo moiety (Scheme 9).112,134–136 The HS-TMPA (no L, L’ = TMPA) complex displays a side-on binding between Fe and O22−,134,137 which is confirmed by characterization of a tethered complex that has a highly similar ligand architecture and spectroscopic properties (Figure 10).113 The related HS-AN complex displays a greater degree of O–O activation, a consequence of the Cu center shifting from binding end-on to the peroxide in HS-TMPA to side-on in HS-AN due to the change in coordination number about Cu.135,137 Addition of an axial ligand to Fe leads to a change in its spin state, and loss of one Fe–O interaction, resulting in end-on binding in LS-TMPA and LS-AN for both Fe and Cu centers.112,136,138 The consequences of the end-on/end-on binding mode include decreased activation of O22− (based on vibrational spectroscopy) and an increased Fe–Cu distance.

Scheme 9.

Influence of Fe and Cu Coordination Environment on Peroxo-Moiety.

Figure 10.

XRD structure of stable Fe/Cu-peroxo complex reported by Chishiro et al.113.

The characterization of heme/Cu-superoxo and -peroxo complexes discussed here have important implications for understanding the cooperativity between Fea3 and CuB in HCO during O2 activation. A major conclusion from these HCO model studies is that the precise role of CuB will be highly dependent on its coordination geometry, distance from the heme, and protonation state of the reduced O2 species. Whether the early intermediates in HCO involve end-on bridging peroxo species, like LS-AN, or if the protein environment shifts the equilibrium towards an FeIII–O2−/CuI, similar to what has been observed for other tethered heme/Cu assemblies, would effect our perspective of a number of aspects of HCO catalysis, such as the role of protons in formation of the P state, and the selectivity the native enzyme displays for complete O2 reduction to water.

We can consider most of the discussed FeIII–O2−/CuI and FeIII–(O22−)–CuII complexes as models of HCO active site in the early A or IP states. Further activation to completely cleave the O–O bond in synthetic biomimetic complexes nearly always requires the addition of some form of reducing equivalent. Interestingly, this observation is despite the fact that there are available electrons from the metal centers, or porphyrin ligand. An exception of complete O–O bond cleavage of H2O2 with an FeIII/CuII complex has been reported by the Casella group: the tethered protoporphyrin IX/Cu complex demonstrates peroxidase-like activity with (L4)FeIII/CuII for the oxidation of para-cresol (Scheme 7).129 Further study of the effect of nonheme metal on this peroxidase-like activity confirm the major role of the metal is to enhance H2O2 binding to heme, and promote heterolytic cleavage to form the compound I-like active oxidant, (porph•+)FeIV=O.139 Although this reaction is not totally relevant to O2 reduction in HCO, it demonstrates that obtaining additional reducing equivalents from the ligand is a viable way to cleave the O–O bond. In contrast, in initial attempts to promote O–O cleavage in HS-AN and HS-TMPA, the addition of strong acid to these FeIII–(O22−)–CuII intermediates simply leads to release of H2O2 (Scheme 10).135 This is a different outcome from related mononuclear FeIII–O22− complexes, which can form analogues to compound I upon addition of acid.66,140 Complete O–O cleavage from HS-AN and HS-TMPA requires addition of at least two equivalents of reductant, yielding the corresponding bridging-oxo product [(L6)FeIII–μ2-O–CuIIL’]+.135

Scheme 10.

Reactivity of HS-TMPA and HS-AN Towards Acid and Reductant to Yield H2O2 and H2O, Respectively.135

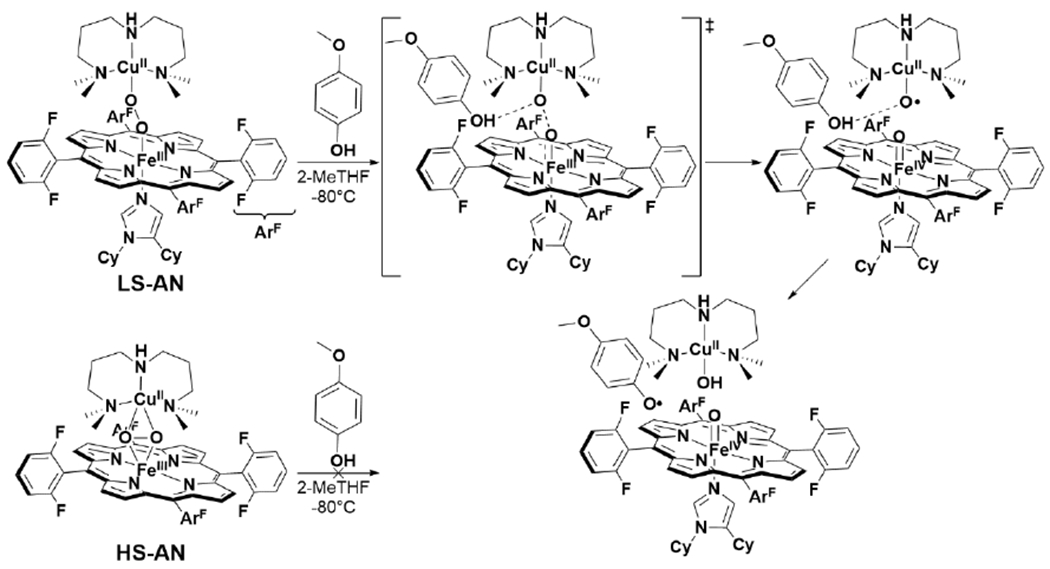

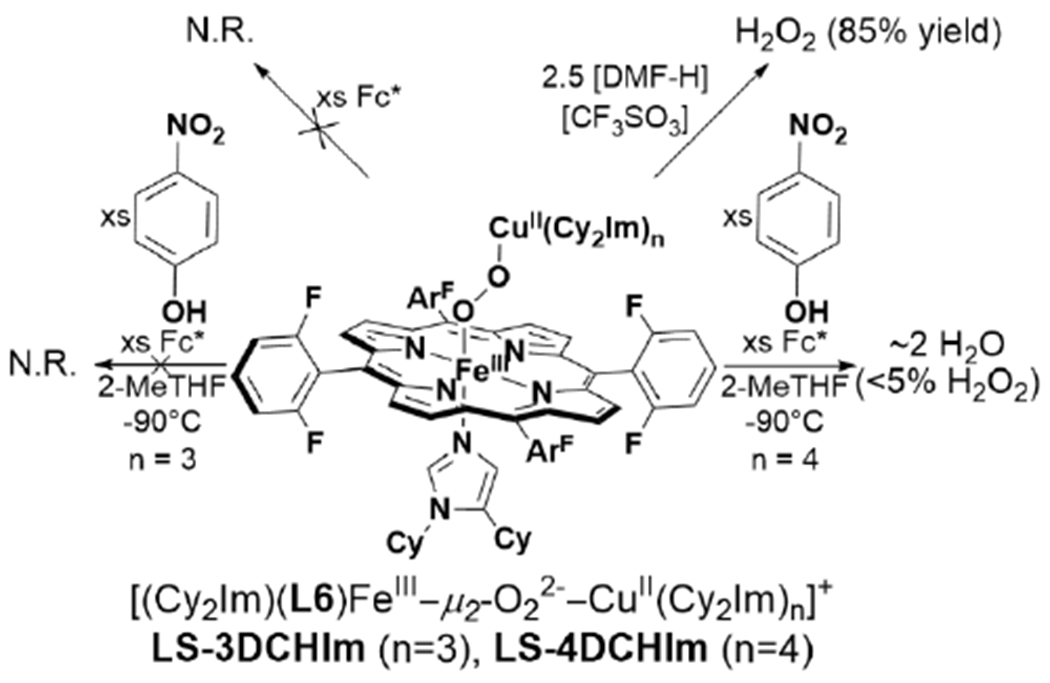

There are examples of phenols being used to promote complete O–O cleavage in heme/Cu assemblies, which can support the important role of the active site Tyr as a proton and electron donor in HCO. Collman et al. reported the reaction of [(L1)FeIII–O2−/CuI]+ with sterically-hindered phenols generates a phenoxyl radical along with [(L1)FeIv=O/CuII–OH]+, analogous to the PM state of HCO (Scheme 11).141 In a later study, they showed that a modified tethered ligand (L2), bearing a mimic of the His-Tyr crosslink could similarly achieve complete O–O cleavage of O2 with intramolecular PCET from the appended phenol.142 More recently, a detailed computational and kinetic isotope effect study of the reaction between LS-AN with phenol has provided insight to the mechanism of the phenol-promoted O–O cleavage.143 A mechanism involving hydrogen-bond assisted homolytic cleavage of the bridging peroxo was favored over an alternative that involved initial proton transfer from phenol to generate a transient hydroperoxo (Scheme 12). The potential relevance of this mechanism to HCO was discussed, and it was concluded that proton transfer from the His-Tyr crosslink is an essential prerequisite for its capacity to serve as an electron donor for O–O cleavage.143 On the other hand, many other reported heme/Cu assemblies do not display complete O–O cleavage in the presence of phenols, or appended phenol moieties. It is thought that the low spin ferric heme of [(L1)FeIII–O2−/CuI]+ is crucial for its difference in observed reactivity.137 It is surprising, then, that a similar phenol-appended ferric-superoxo complex reported by Liu et al. is unreactive (Scheme 8).132 Furthermore, Adam et al. have recently demonstrated that two low spin FeIII–(O22−)–CuII complexes (LS-4DCHIm and LS-3DCHIm) display different reactivity towards weak phenolic acid and reductant, based on differences in Cu coordination (Scheme 13).144 There are likely other important structural and electronic features of heme/Cu assemblies which determine their propensity to completely cleave the double-bond of O2 which remain to be elucidated.

Scheme 11.

O–O Cleavage Induced by Inter- and Intramolecular Proton Coupled Electron Transfer from Phenol.141,142

Scheme 12.

Hydrogen Bond-Assisted Mechanism of O–O Cleavage in LS-AN.143

Scheme 13.

Reactivities of Low-Spin FeIII–(O22−)–CuII Complexes with Different Cu Coordination Number.144

2.4.3. Catalytic Dioxygen Reduction by HCO Models.

Study of the catalytic performance of biomimetic heme/Cu assemblies has been complementary to low-temperature spectroscopic studies of heme/Cu O2 intermediates relevant to HCO, as discussed in the previous sections. In particular, the application of biomimetic heme/Cu complexes to electrocatalysis has been particularly useful in understanding the importance of reduction potentials and electron flux on efficient and selective O2 reduction. More extensive reviews covering the breadth of (electro)catalytic O2 reduction by synthetic complexes related to HCO have been published.66,145–147 Here we will highlight insights gained relevant to our understanding of the mechanism of the native enzyme. Catalytic studies are useful for investigating key structural features that are relevant for high ORR activity, with high selectivity (low PROS formation), and, in some cases, can also be studied using in situ spectroscopic techniques to directly examine the nature of reactive, catalytically-relevant intermediates.

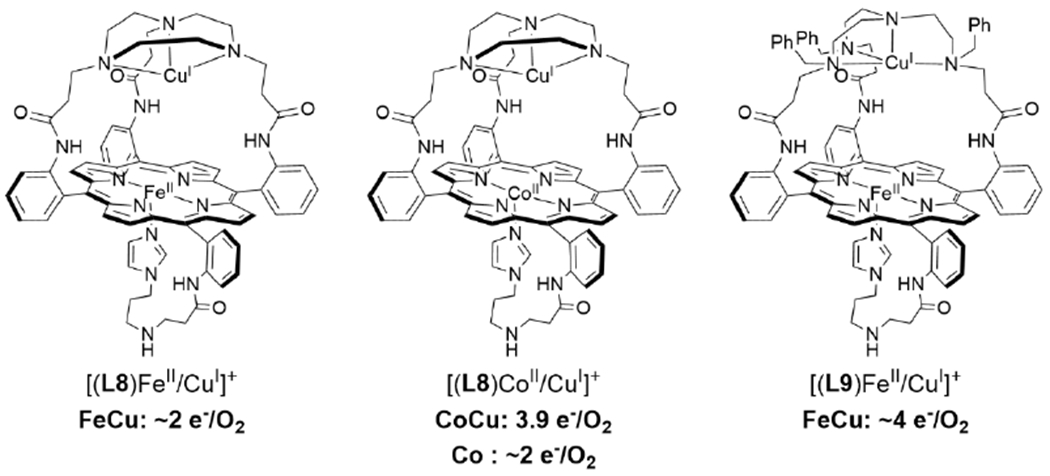

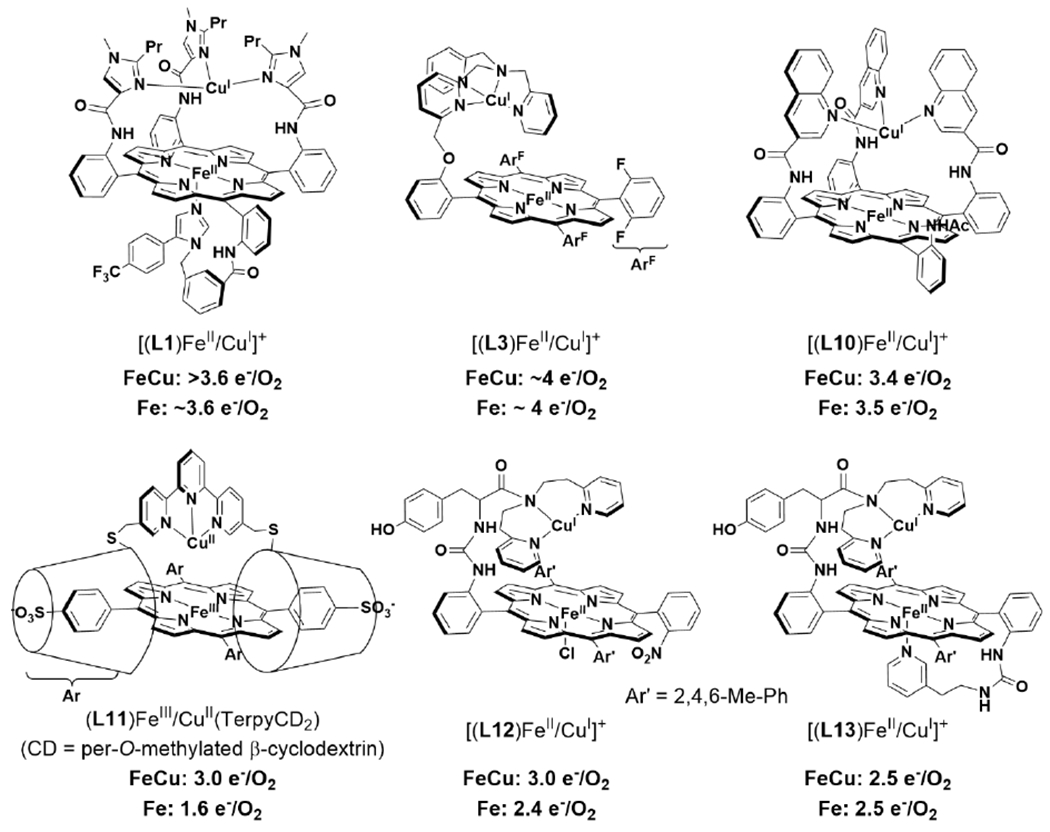

Many relatively complex synthetic porphyrin structures have been examined for catalytic ORR activity. Among these that are relevant to HCO, interesting dependences (or lack thereof) of the Cu center on the extent of PROS formation have been observed. For example, a series of ‘capped’ porphyrin complexes reported by Collman et al. are able to electrocatalytically reduce O2 to form 2 or 4 e− reduced products (Scheme 14).148 The complexes where the Cu is easier to reduce than the Fe porphyrin display mixtures of 2 and 4 e− O2 reduction, where the 2 e− reduced products are attributed to reaction pathways that only involve Cu. Substitution of Fe for Co, which is easier to reduce than the Cu center, leads to exclusive formation of H2O.149 Interestingly, many other heme/Cu ORR catalysts display no increase in selectivity with Cu, likely due to the catalytic conditions that employ a large excess of reducing equivalents (Scheme 15).114,123,150,151 In other examples of electrocatalytic ORR by tethered and supramolecular heme/Cu assemblies, Cu has been shown to slightly increase the average electrons transferred under electrocatalytic conditions, suggesting the Cu is playing a role in storing electrons (Scheme 15; (L11)FeIII/CuII(TerpyCD2) and [(L12)FeII/CuI]+);116,152,153 however, no dramatic rate enhancement comes from the presence of Cu.

Scheme 14.

Selectivity of Electrocatalytic ORR By Heme/Cu Complexes.148,149

Scheme 15.

Effect of Cu on Catalytic ORR Selectivity for Various HCO Model Complexes. 114,116,123,150–153

Another structural feature of HCO that has been mimicked in a number of ORR catalysts is the active site Tyr residue. Electrocatalytic ORR studies of synthetic tethered heme/Cu complexes containing a pendant phenol demonstrate that, in some cases, the phenol moiety has no effect on ORR,154 while, in slightly different metal coordination environments under different catalytic conditions, the phenol can help reduce PROS formation.115 In the latter case, the phenol is postulated to reduce PROS through mimicking the role of the His-Tyr in HCO, which is supported through single-turnover studies (Scheme 11).142

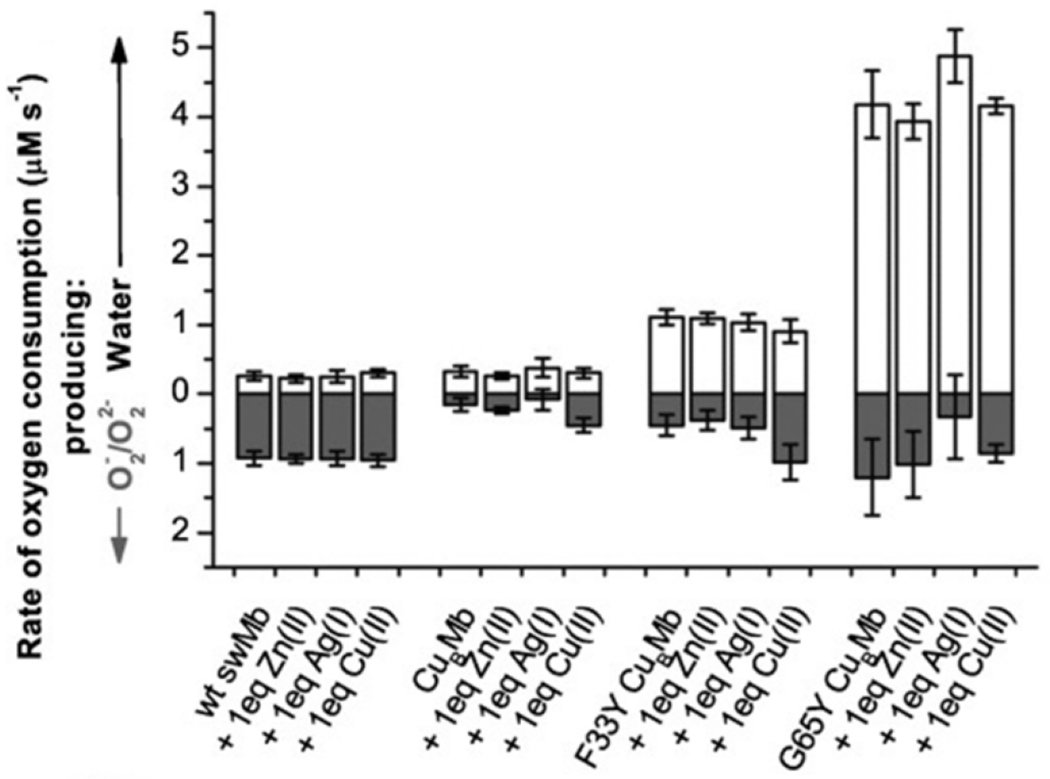

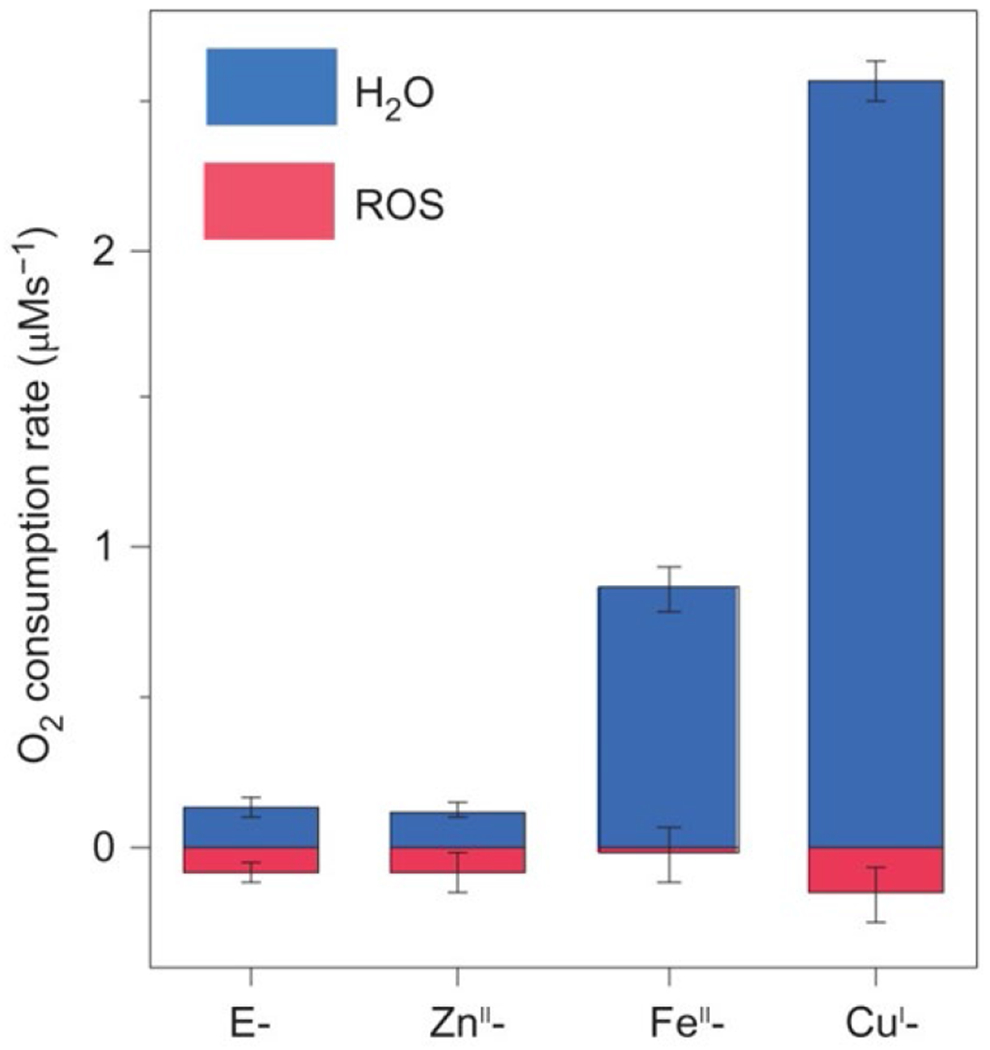

The effect of the active site Tyr, and the His-Tyr crosslink, on catalytic ORR has been thoroughly investigated through the biosynthetic CuBMb system. Miner et al. demonstrated that introducing a Tyr residue near the active site (Phe33Tyr or Gly65Tyr) dramatically increases the rate and turnover number (Figure 11).150 The Gly65Tyr CuBMb mutant displays more than double the activity relative to Phe33Tyr CuBMb, demonstrating the importance of this residue’s positioning relative to the heme active site. Furthermore, these Tyr-containing mutants display greater selectivity for complete O2 reduction, which was directly confirmed by measuring H217O formation from 17O2. Remarkably, further engineering of Gly65Tyr CuBMb through introducing positively charged residues on the protein surface, in order to facilitate faster ET, produces an ORR enzyme with activity comparable to that of a native HCO.155 An XRD structure of reduced Phe33Tyr CuBMb with O2 shows that the introduced Tyr residue participates in hydrogen-bonding interactions with a water network leading to the bound O2 (Figure 12).156 This proton-delivery pathway was proposed to be a major reason for the higher activity of Phe33Tyr CuBMb, relative to WT swMb. Further investigation of this structural feature in Phe33Tyr was done through replacing the Tyr with unnatural amino acid analogues of Tyr bearing different electron-withdrawing groups.157 Decrease of the pKa of the phenol sidechain leads to an increase in ORR activity, consistent with this residue being involved in PT during turnover. Evidence for Tyr residue also serving as an electron donor, and forming a Tyr-O•, similar to the mechanistic proposals of HCO, were observed by treating oxidized Phe33Tyr CuBMb (or the unnatural Tyr analogues) with H2O2.157,158 An EPR signal consistent with a phenoxyl radical is observed, which is not present in CuBMb without this Phe33Tyr mutation. Lower amounts of this radical are also observed when the reduced biosynthetic protein is incubated with O2, supporting its relevance to the catalytic mechanism.158 Finally, to understand the potential importance of the covalent link between His and Tyr in native HCO, an unnatural amino acid mimicking this cross-link (imidazolyl-tyrosine; imiTyr) was incorporated into CuBMb (imiTyr CuBMb).159 This biosynthetic protein was unique for displaying higher CuII affinity, and higher ORR activity than Phe33Tyr CuBMb (12 μM O2 min−1 for imiTyr CuBMb+CuII versus ~5 μM O2 min−1 for Phe33Tyr CuBMb, under identical conditions). Furthermore, addition of CuII was shown to significantly decrease PROS formation from 30% to 6%, suggesting this crosslink may have a role in retaining and tuning the Cu center for more selective O2 reduction.

Figure 11.

ORR activity of swMb and biosynthetic HCO models. Figure adapted from ref. 150 Copyright Wiley-VHC 2012

Figure 12.

H-bonding network in O2-bound Phe33Tyr CuBMb crystal structure. Figure adapted from ref. 156 Copyright American Chemical Society 2016.

As mentioned previously, the majority of direct electrocatalytic or homogenous ORR studies of heme/Cu systems show little benefit from Cu or, in some cases, display greater propensity for PROS production when Cu is present. Collman et al. hypothesized that to observe HCO-like ORR catalysis, the nature of ET rate and active site isolation should be closer to the conditions of the native enzyme.160 Indeed, depositing the [(L1)FeII/CuI]+ complex into a phosphtidylcholine film on the electrode surface ensures site-isolation of the catalyst and reduces the rate of ET to being diffusion limited.160 Under these conditions, [(L1)FeII/CuI]+ displays selective 4 e-reduction of O2. Further control of the ET rate from electrode to catalyst could be accomplished by covalent attachment of heme/Cu complexes onto self-assembled monolayer (SAM) films on Au electrodes.114,115 These studies use functionalized SAM components that facilitate fast (~103 - 104 e− s−1) or slow (4 - 6 e− s−1) ET to various HCO mimics. Comparison studies of related picket-fence porphyin complexes, (L1)FeII,[(L1)FeII/CuI]+, and [(L2)FeII/CuI]+, demonstrate that the catalyst with all 3 redox active centers, [(L2)FeII/CuI]+ (FeCuArOH), produces the least amount of PROS under fast and slow ET regimes, however the difference between the three catalysts is much more pronounced when ET is slow (Figure 13).115 Analogous studies with (L3)FeII, [(L3)FeII/CuI]+, and [(Im)(L3)FeII/CuI]+ show similar effects: Cu decreases PROS formation, which is further reduced when an addition axial heme ligand is present, but only under low ET rates with C16SH (Figure 14).114 Together, these results demonstrate that, under conditions where reducing equivalents are transferred slowly, structural features that more faithfully model the features of HCO (nonheme CuI, nearby phenol, and low-spin ferric heme) produce a more selective ORR catalyst.

Figure 13.

Effect of Cu and phenol on electrocatalytic ORR selectivity under ‘fast’ and ‘slow’ ET regimes, through covalent tethering of catalyst to different Au SAM electrodes. Figure adapted from ref. 115 Copyright the American Association for the Advancement of Science 2007.

Figure 14.

Effect of Cu and axial ligand on PROS formation on electrocatalytic ORR with (L3)FeIII (6L-Fe) and related complexes. Electron flux is controlled by measuring catalysis with different electrodes: fast ET with edge-plane graphite (EPG), slow ET with 1-octanethiol SAM on Au (C8SH), and very slow ET with 1-1-hexadecanethiol SAM on Au (C16SH). Figure adapted from ref. 114 Copyright American Chemical Society 2015.

An advanced spectroscopic technique, known as surface-enhanced resonance Raman spectroscopy (SERRS) has been used by the Dey group for the study of catalytic intermediates of some of these biomimetic ORR catalysts.147 Using SERRS to examine the mechanism of ORR by (L3)FeII, [(L3)FeII/CuI]+, and [(Im)(L3)FeII/CuI]+ the authors observed [(Im)(L3)FeII/CuI]+ produces a six-coordinate low-spin (l.s.) FeII species upon reduction, with or without O2 present (Scheme 16).114 The sluggish substitution of the sixth ligand (presumably H2O) for O2 was attributed to this complex’s higher PROS at high electron flux, due to side reactions of CuII-O2− species. Furthermore, spectroscopic evidence for significant formation of the (L3)FeIII–O22−–CuII intermediate is observed, with and without an imidazole axial ligand. Build-up of FeIV=O is observed with (L3)FeII, but not the other two complexes, which the authors attributed to a high-potential compound I analogue forming upon heterolytic cleavage of the peroxo intermediates.114,147 A similar mechanistic study of ORR by Gly65TyrCuBMb yielded SERRS spectra of numerous oxidized Fe signals under catalytic turnover, including l.s. FeIII—possibly superoxo or peroxo intermediates—and FeIV=O.161 By attaching Gly65Tyr CuBMb to this electrode, this biosynthetic protein is able to display ORR activity over 100 times faster than other synthetic models, and 10 times faster than electrode-immobilized native HCO.

Scheme 16.

Proposed Mechanism of ORR by [(Im)(L3)FeII/CuI]+ Based on intermediates Observed Via SERRS. Figure Adapted from Ref. 147. Copyright American Chemical Society 2016.

2.5. Summary and Outlook of HCO and Biomimetic Models.

Through decades of studying native HCO and biomimetic models, we have improved our understanding of key structural features responsible for efficient and selective reduction of O2 to H2O through the proposed mechanism that has been illustrated in Scheme 2. Probing the O2 reactivity of heme/Cu assemblies has demonstrated that both the primary coordination sphere (i.e., the heme with axial ligand and tridentate coordination of CuB) and the surrounding secondary coordination sphere (including hydrogen-bonding interactions with water molecules anchored by the phenol of the highly conserved His-Tyr moiety) is crucial for various aspects of catalytic O2 reduction, including O2 binding and O–O cleavage. Specifically, while the precise role of Cu is highly dependent on its coordination geometry, distance from the heme, and protonation state of the reduced O2 species, it has a functional role in promoting O2 binding through its Lewis acidity, along with increasing the binding affinity of the heme to various other ligands. In addition, coordination of an axial ligand to heme can lead to a change in the Fe spin state, affecting the binding properties towards O2; this axial ligand also has an effect on the binding interactions between Cu and O2. Synthetic heme/Cu systems have been observed with a range of O2 binding modes, from close side-on/side-on binding (μ-η2,η2) to negligible Cu-O2 interactions, favoring a FeIII–O2− complex. Furthermore, the active site Tyr residue in HCO is an essential proton and electron donor for O–O cleavage and its covalent crosslink to the Cu-coordinating His residue tunes the reactivity of the phenol and CuB that further promote O2 activate. Interestingly, while many catalytic ORR studies of heme/Cu systems show little benefit from Cu, conditions where reducing equivalents are transferred slowly reveal that models with structural features that more faithfully model the core components of HCO (nonheme Cu, nearby phenol, and low-spin ferric heme) produce a more selective ORR catalyst. The application of biomimetic HCO models towards catalytic ORR has not only improved our understanding of these enzymes, but has shown that, by incorporating these crucial structural features from the native active site, catalytic activity that matches, or even surpasses, native enzymes can be accomplished. One crucial characteristic of the native HCO mechanism that is relatively underdeveloped in biomimetic complexes, however, is that it is capable of ORR with considerable energy conservation, to generate potential energy though proton translocation. This functional feature of HCO is derived from precise control of the reduction potentials and pKa values of the BNC during turnover. Learning how to mimic these aspects in simpler models would further improve our molecular understanding of HCOs.

While significant progress has been made concerning our mechanistic understanding of HCO, there remain a number of key questions:

What is the nature of the (transient) peroxo intermediate, IP? Is this intermediate protonated prior to O–O cleavage? Does Cu bind to this intermediate prior to transition to P state?

What structural features in the OH state lead to its high reduction potential?

How is the His-Tyr cross-link formed?

While it is challenging to trap these intermediates in the native system, synthetic models have been an invaluable means to interrogate these proposed intermediates. Further study of these model systems may inform how the structural aspects of these proposed intermediates impact their reactivity and potential catalytic relevance.

3. Bacterial Nitric Oxide Reductase (NOR) and Related Biomimetic Models

3.1. The Heme/FeB Active Site of Bacterial NORs.

Certain bacteria are able to reduce NO to nitrous oxide (N2O) during a metabolic process known as denitrification, which converts nitrate (NO3−) and nitrite (NO2−) to N2.162,163 Denitrification can be considered an anaerobic version of respiration—the corresponding aerobic respiration process performs 4 e− reduction of O2 to H2O by heme-Cu oxidase enzymes (HCO), which generates chemical potential energy through proton translocation (see section 2). HCO and bacterial NORs belong to the same enzyme superfamily known as the heme-Cu oxidase superfamily, which are a diverse group of integral transmembrane proteins that share a relatively similar catalytic subunit, with a diverse array of secondary subunits involved in proton and electron transfer (Figure 2).164,165 The NOR enzyme class has been sub-divided principally on the initial electron donors (Scheme 17): cytochrome c for cNOR and quinol for qNOR. A third sub-class of NOR has been discovered which contains a CuA cofactor and obtains its electrons from either cytochrome c or quinol, denoted CuANOR. The CuANOR subclass is further subdivided into bNOR, eNOR, and sNOR, based on homology models of predicted genes.30 XRD and cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM) structures of cNORs and qNORs have been obtained from various bacteria.166–172 To date, no structures of CuANORs have been reported, but biochemical studies from a CuANOR from Bacillus azotoformans have been described.173,174

Scheme 17.

Various Cofactors Observed in NORs and ET Pathway to the BNC Active Site.

The study of bacterial NORs have been challenging due to being integral membrane proteins that contain multiple redox active transition metal cofactors. The first in vitro study of NO-reducing activity of membrane fractions of extracts from Alcaligenes faecalis IAM 1015 was reported in 1971.164,175 However, it wasn’t until 1989 that a preparation of purified, active NOR, cNOR from Pseudomonas stutzeri (PsNOR) was established by Heiss et aI., using Triton X-100 detergent as a stabilizing agent.176 Biochemical studies of PsNOR, and later purified NORs from other bacteria, confirmed that these enzymes selectively catalyze the 2 e− reductive coupling of two NO molecules to form N2O (eq 2),176–178 avoiding alternative reactions, including reductive NO disproportionation (eq 3) which is considered a more common reaction that occurs between NO and transition metal complexes.179

| (2) |

| (3) |

Later efforts established that cNOR contains three heme cofactors (heme c, b, and b3, where b3 denotes a high spin heme b cofactor), along with a nonheme Fe (FeB).180,181 In 1994, analysis of the available sequences from bacterial NORs and multiple HCOs established for the first time an evolutionary link between these two enzyme classes.182 A suitably high resolution XRD structure of a bacterial NOR enzyme was not obtained until 2010,166 but by 1998 the overall protein structure of NOR—and the positioning of its metallocofactors—had been inferred via homology modelling to a published HCO crystal structure.183 By this time, it was widely accepted that bacterial NORs had an architecture similar to the catalytic subunit of HCO, including an analogous bimetallic active site, denoted the binuclear center (BNC), where a histidine-coordinated high-spin heme cofactor is positioned next to a nonheme metal that is bound to three conserved His residues.163 A distinguishing feature of NOR sequences, compared to HCO, is the presence of multiple conserved glutamate residues near the BNC, including Glu211 (the numbering from Pseudomonas aeruginosa cNOR; PaNOR) which was proposed to be an additional ligand to FeB, to satisfy a preferred octahedral geometry.184 Biochemical studies by Butland et al. in the early 2000’s demonstrated that some of the conserved Glu residues in P. denitirificans cNOR (PdNOR) are essential for enzymatic activity (Glu198 and Glu125, PdNOR numbering), while not significantly disrupting the assembly and coordination of the metal cofactors (including FeB).185 Glu198 of PdNOR corresponds to Glu211 in PaNOR, the potential FeB binding residue.

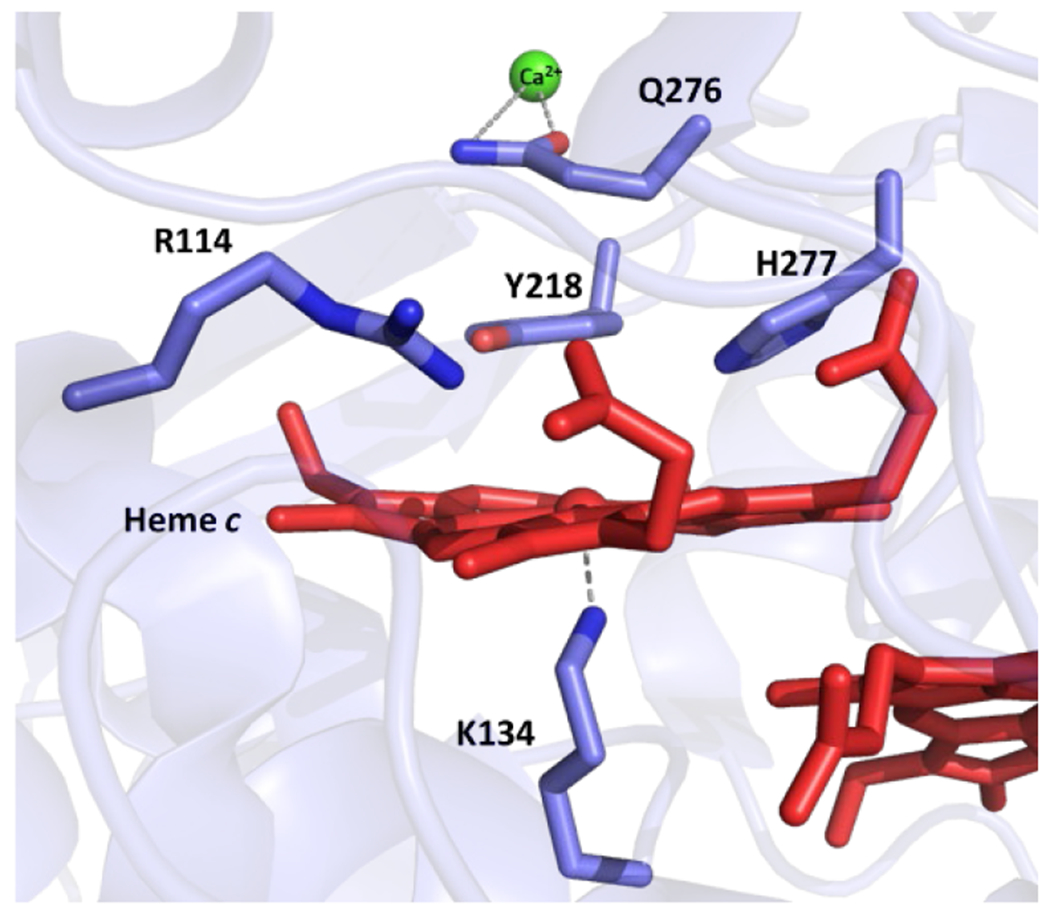

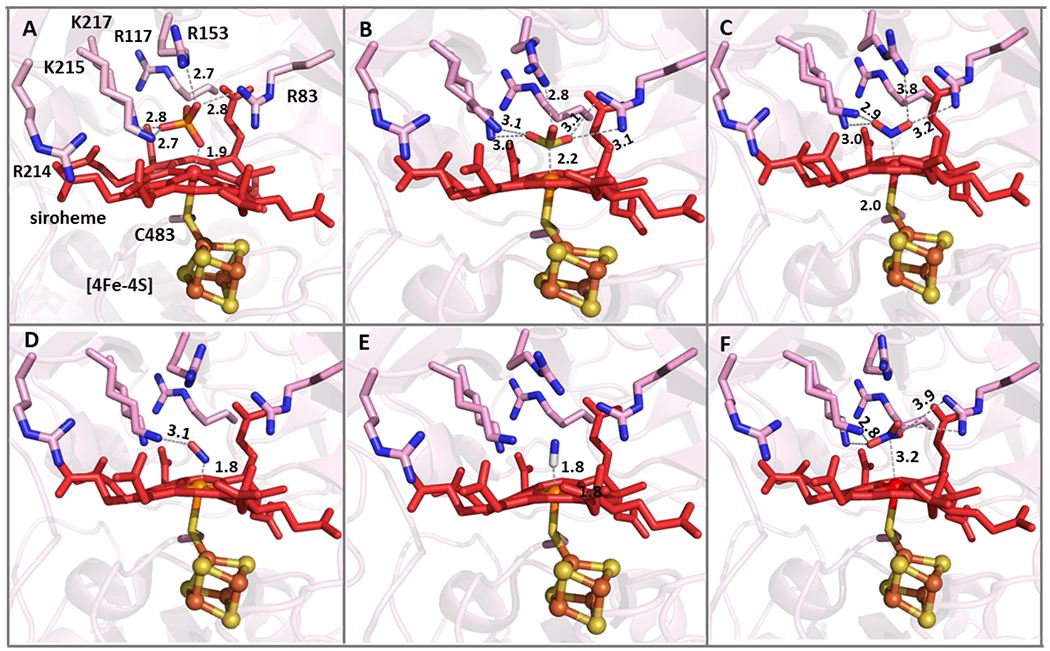

When the first XRD structure of a bacterial NOR, PaNOR, was disclosed by Hino et al. in 2010, it confirmed much of the prevailing ideas concerning the general organization of the polypeptide backbone, and the molecular arrangement of the BNC active site (PDB ID: 3O0R).166 PaNOR is composed of two subunits, NorB (56 kDa), which displays 12 transmembrane α-helices that contain the BNC and the heme b cofactor, coordinated by two His residues, and NorC (17 kDa), a single transmembrane α-helix attached to a periplasmic-facing domain that contains the heme c center coordinated by His and Met residues (Figure 15). An ET pathway from the periplasmic surface of PaNOR can be traced from the heme c, b, and b3 centers, with a CaII ion bridging the propionates of hemes b and b3, which is thought to aid in arranging these cofactors for efficient ET. The enzyme was crystallized in its oxidized state, leading the BNC to contain a μ2-O ligand between heme b3 and FeB (Figure 16A). The Fe–Fe distance of the BNC is relatively short, 3.9 Å, compared to the Fe–Cu distance of 4.4 Å in Tt ba3 oxidase (an HCO).166 FeB is 5- or 6-coordinate, with either k1-O or k2-O,O’ binding to the carboxylate side chain of Glu211 (Fe–O distances of 2.04 and 2.47 Å), along with bonds to the μ2-O and the three conserved His residues (His207, 258, and 259). Multiple Glu residues near FeB (Glu 211, 215, and 280) lead to a relatively electronegative distal pocket for heme b3, significantly lowering its reduction potential in PdNOR to ~ 60 mV (vs NHE), compared to the potentials of heme c and heme b, (310 mV and 345 mV, respectively).186 These Glu residues are also thought to be part of a putative PT pathway from the periplasm to the buried active site (Figure 17). The distance between one of the heme b3 propionates and the next hydrogen-bonding residue (Thr330) is 8.0 Å in the crystal structure, suggesting conformational changes in PaNOR are necessary to form a complete PT pathway.166 Molecular dynamics simulations of PaNOFt suggest two possible PT pathways, based on protein structural rearrangements over time.187

Figure 15.

XRD structure of PaNOR (PDB ID: 3O0R), comprised of NorB (green) and NorC (magenta) subunits.

Figure 16.

Different XRD structures of BNC of NORs. (A) Resting state PaNOR (PDB ID 300R) with μ2-O, (B) reduced PaNOR (PDB ID 3WFB) with μ2-Cl−, (C) reduced PaNOR (PDB ID 3WFC) with CO bound, (D) reduced PaNOR (PDB ID 3WFD) with acetaldoxime, (E) GsNOR (PDB ID 3AYF) with ZnII at the FeB site, (F) NmNOR (PDB ID 6LIX) with ZnII inhibitor coordinating 3 Glu residues, (G) cryo-EM structure of NmNOR (PDB ID 6L3H), and (H) cryo-EM structure of AxNOR (PBD ID 6QQ5).

Figure 17.

Structure of PaNOR showing the putative PT channels (1 and 2), along with the hydrophobic channel for NO transfer (yellow). Figure adapted from ref. 166 Copyright the American Association for the Advancement of Science 2010.

PaNOR has also been crystallized in reduced and ligand-bound forms, to gain further insight into the possible BNC structures during turnover.169 The reduced structure (PDB ID: 3WFB) contains a bridging Cl− between heme b3 and FeB and displays a slightly increased distance between the Fe centers (Fe–Fe distance of 4.2 Å, compared to 3.9 Å of oxidized form) (Figure 16B). This greater distance is still significantly shorter than the Fe–Cu distances in structures of most HCO enzymes (see Table 3 in section 5),188 leading to speculation that two diatomic molecules may not be able to bind the metals simultaneously within the BNC. On the other hand, the CO-bound structure of reduced PaNOR contains an ovoid electron density between heme b3 and FeB, which is difficult to model (PDB ID: 3WFC), but detailed analysis by Sato et al. concluded that, while ambiguous, the electron density is only suitably accounted for with four non-hydrogen atoms in the active site (a CO and two H2O, or two CO ligands) (Figure 16C).169 Similarly, acetaldoxime (CH3CHNOH) binds to the BNC in PaNOR, and it can be considered an analogue to hyponitrite (ONNO2−), a key intermediate in all major NOR mechanistic proposals (see section 3.3). The acetaldoxime-bound structure (PDB ID: 3WFD) more clearly demonstrates that four non-hydrogen atoms can fit within the BNC of NOR, although the binding mode displays a relatively short Feb3–N(R)–O(H)–FeB bridging motif, which doesn’t necessarily support an interpretation where each metal can bind NO simultaneously (Figure 16D). It has been proposed that Glu211 may dissociate from FeB to increase the Fe–Fe distance, and facilitate binding of a second NO molecule during catalysis;185,189 despite this proposal, all three of these reduced PaNOR XRD structures show Glu211 bound to FeB, with relatively short Fe–Fe distances of 4.2 – 4.4 Å.169 Interestingly, flash photolysis vibrational spectroscopy of CO-bound CuANOR from B. azotoformans clearly demonstrates that two CO molecules bind to heme b3 and FeB simultaneously (see section 3.3.3);190 although it should be noted that, based on the sequence and homology structure of this CuANOR, there may be no fifth residue to coordinate FeB.174

Table 3.

Representative NOR and HCO Heme-Nonheme Distances.

| Class | PDB Code | Form | Nonheme metal | Distance (Å) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| cNOR (Pa) | 3O0R | oxidized | Fe | 3.8 |

| cNOR (Pa) | 3WFB | reduced | Fe | 4.2 |

| cNOR (Pa) | 3WFC | reduced, CO-bound | Fe | 4.4 |

| qNOR (Ax) | 6QQE | oxidized | Fe | 4.1 |

| qNOR (Nm) | 6L1X | oxidized, Zn(II)-inhibited | Fe | 3.8 |

| qNOR (Gs) | 3AYF | oxidized, inactive | Zn | 4.6 |

| A-type CcO (Rs) | 1M56 | oxidized | Cu | 4.8 |

| A-type CcO (Rs) | 3FYE | reduced | Cu | 5.3 |

| B-type CcO (Tt) | 1EHK | oxidized | Cu | 4.4 |

| B-type CcO (Tt) | 3EH3 | reduced | Cu | 5.1 |

| C-type CcO (Ps) | 3MK7 | oxidized | Cu | 4.6 |

Variations in the FeB coordination geometry have been observed in crystal structures of qNORs from Geobacillus stearothermophilus (GsNOR), Neisseria meningitidis (NmNOR), and Acaligenes xylosoxidans (AxNOR), that may be relevant to our mechanistic understanding of NOR.167,170–172 qNOR proteins are single subunit (~85 kDa), with 14 transmembrane α-helices arranged in a pattern similar to the NorB/NorC architecture of cNORs. The ZnII-inhibited crystal structure of NmNOR (PDB ID: 6L1X) displays FeB coordinated by only three His residues and a μ2-O to heme b3, where conserved Glu residues near the BNC bind to a ZnII ion instead (Glu494, 498, and 563 with NmNOR numbering) (Figure 16F).172 While this structure is not catalytically relevant due to the presence of ZnII interacting with residues in the PT pathway to the BNC, it demonstrates that FeB remains present in NOR without Glu coordination. A recent cryo-EM structure of active NmNOR without ZnII, although at a very low resolution of 9 Å, appears to display a relatively weak monodentate Glu494–FeB interaction (Fe–O ~ 2.4 Å), while also having a relatively large Fe–Fe distance (~4.5 Å), which supports the hypothesis that ZnII interferes with Glu494 binding to FeB in the previous NmNOR structure (Figure 16G).172 A separate cryo-EM structure of AxNOR (3.2 Å resolution) further demonstrates that Glu coordination is not necessary for FeB binding (Figure 16H).171 The structure of the oxidized enzyme also displays a larger Fe–Fe distance of 4.1 Å, compared to 3.9 Å in PaNOR, supporting the notion that Glu dissociation could play a role in increasing the distance between the Fe centers in the BNC. Importantly, this structure is a catalytically active form of qNOR. It is known that mutation of the nearby Glu490 residue in AxNOR (analogous to Glu211 in PaNOR) greatly diminishes catalytic activity, consistent with a crucial role of this residue during catalysis, either in stabilizing FeB and/or facilitating PT.185,189 while the structural studies of NOR have revealed a range of coordination geometries that FeB can adopt, it is currently unclear whether this possible lability in Glu coordination has any functional significance.

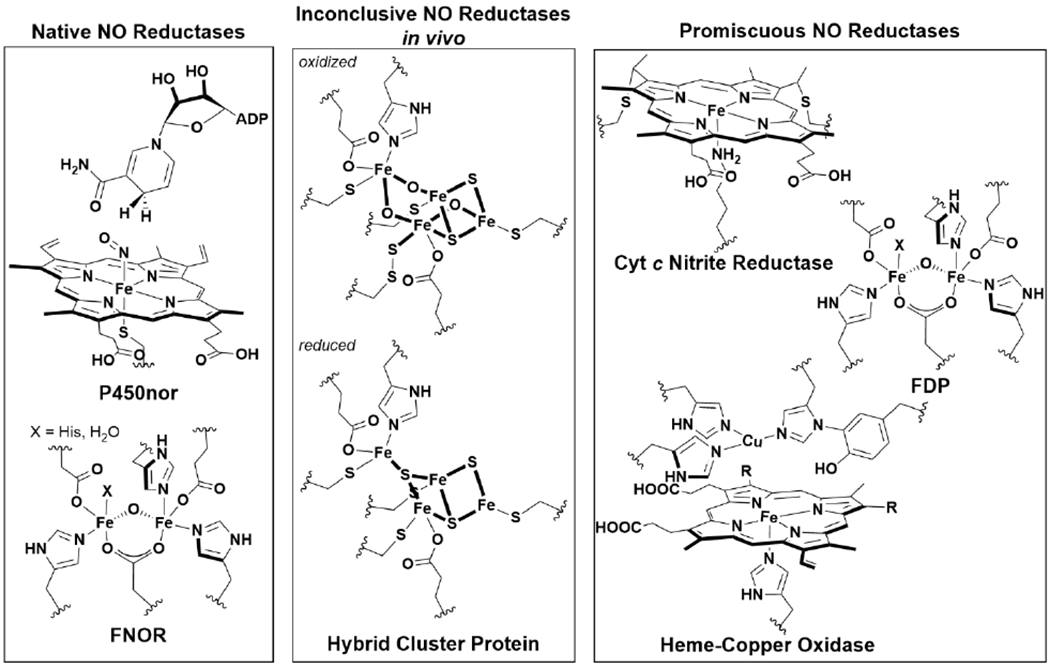

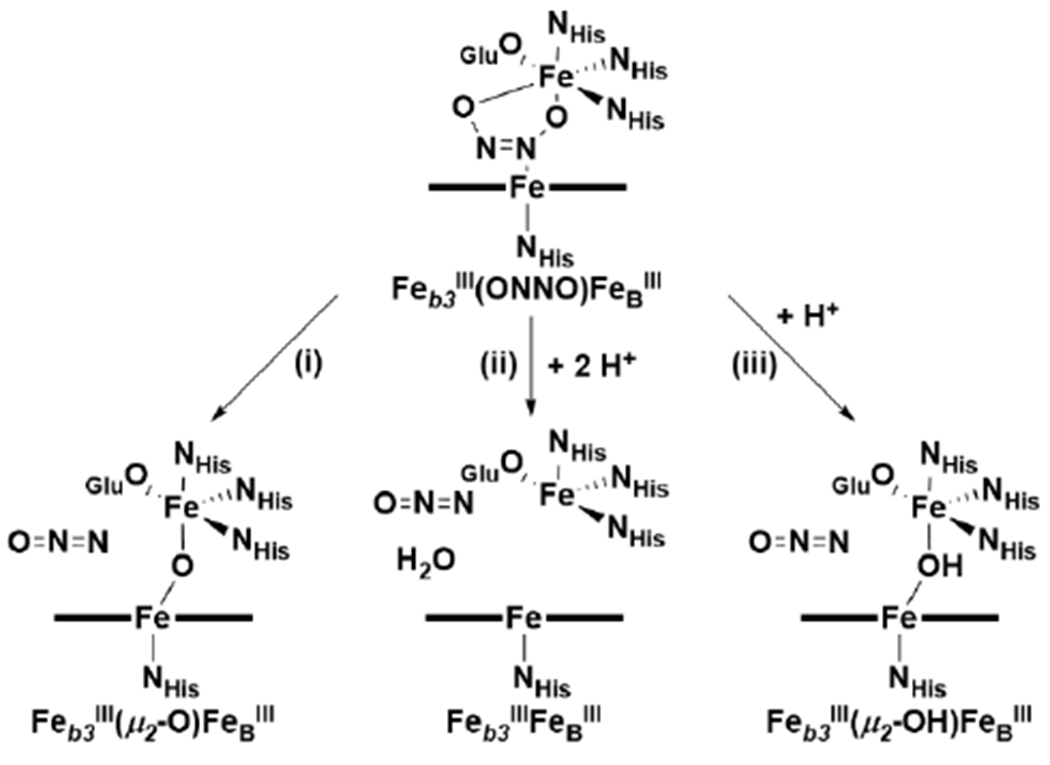

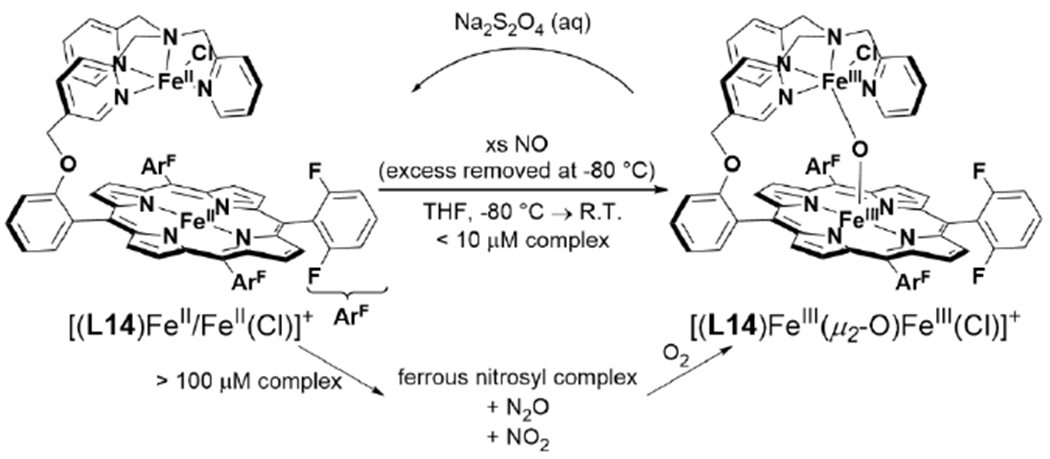

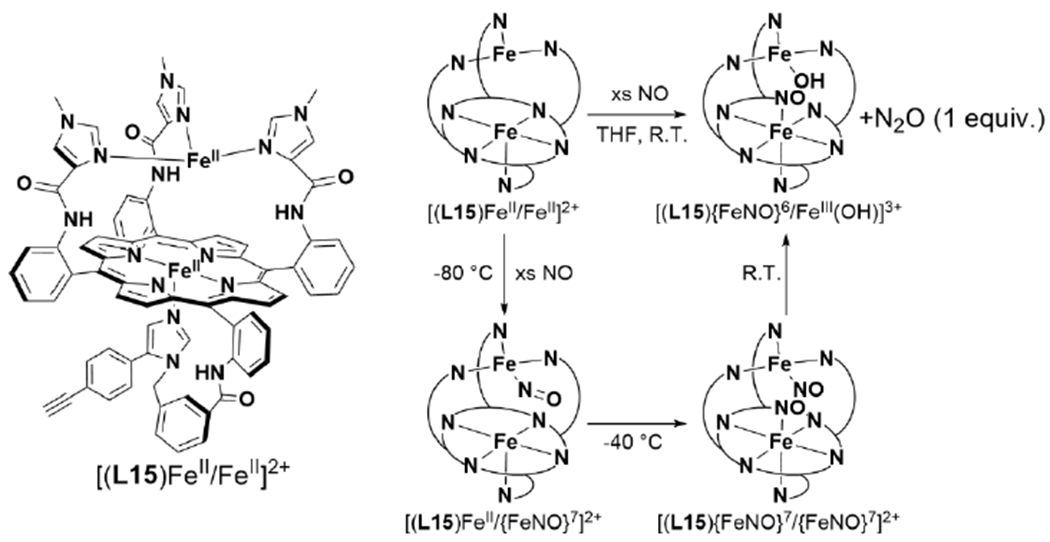

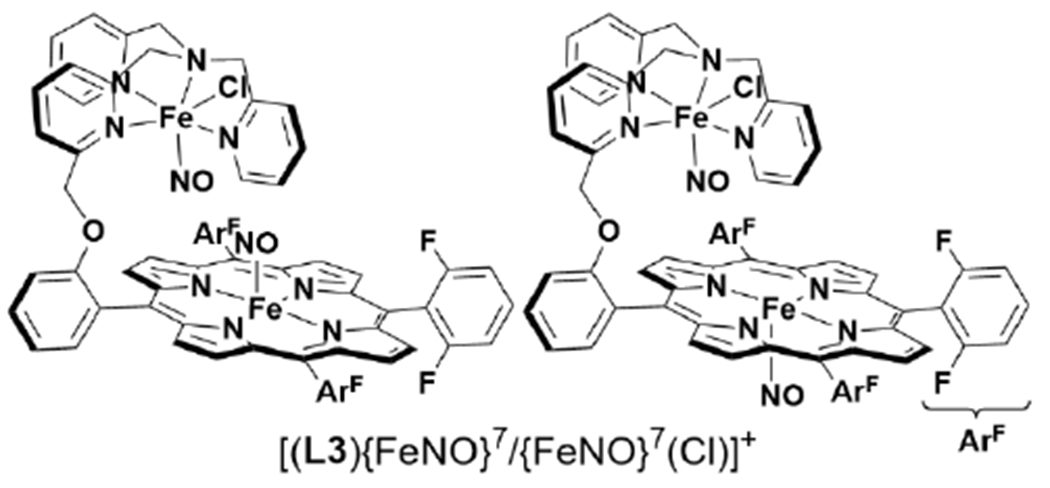

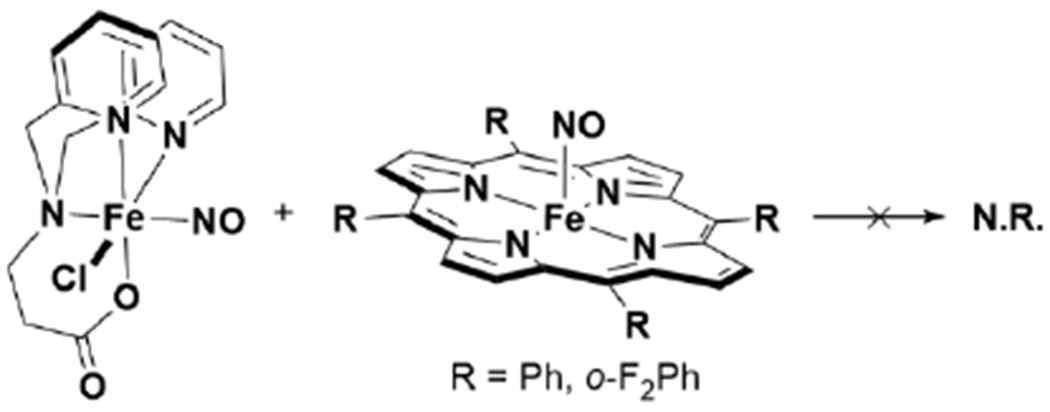

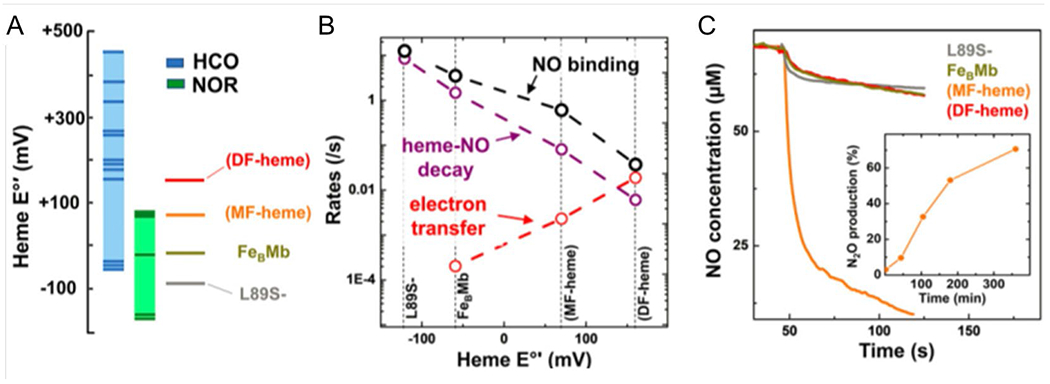

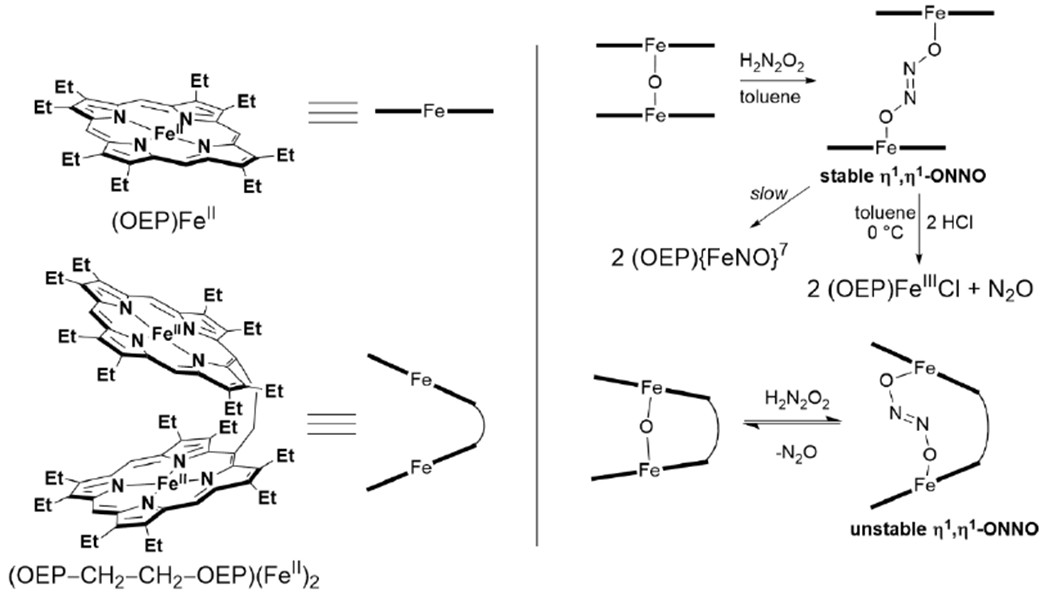

3.2. Other Enzymes that Catalyze NO Reduction.