Abstract

Background:

Kidney transplantation (KT), a treatment option for end-stage kidney disease (ESKD), is associated with longer survival and improved quality of life compared with dialysis. Inequities in access to KT, and specifically, living donor kidney transplantation (LDKT), have been documented in Canada, along various demographic dimensions. In this article, we review existing evidence about inequitable access to KT and LDKT for patients from communities marginalized by race and ethnicity in Canada.

Objective:

To characterize the currently published data on rates of KT and LDKT among East Asian, South Asian, and African, Caribbean, and Black (ACB) Canadian communities and to answer the research question, “what factors may influence inequitable access to KT among East Asian, South Asian, and ACB Canadian communities?.”

Eligibility criteria:

Databases and gray literature were searched in June and November 2020 for full-text original research articles or gray literature resources addressing KT access or barriers in East Asian, South Asian, and ACB Canadian communities. A total of 25 articles were analyzed thematically.

Sources of evidence:

Gray literature and CINAHL, OVID Medline, OVID Embase, and Cochrane databases.

Charting methods:

Literature characteristics were recorded and findings which described rates of and factors that influence access to KT were summarized in a narrative account. Key themes were subsequently identified and synthesized thematically in the review.

Results:

East Asian, South Asian, and ACB communities in Canada face barriers in accessing culturally appropriate medical knowledge and care and experience inequitable access to KT. Potential barriers include gaps in knowledge about ESKD and KT, religious and spiritual concerns, stigma of ESKD and KT, health beliefs, social determinants of health, and experiences of systemic racism in health care.

Limitations:

This review included literature that used various methodologies and did not assess study quality. Data on ethnicity and race were not reported or defined in a standardized manner. The communities examined in this review are not homogeneous and views on organ donation and KT vary by individual.

Conclusions:

Our review has identified potential barriers for communities marginalized by race and ethnicity in accessing KT and LDKT. Further research is urgently needed to better understand the barriers and support needs of these communities, and to develop strategies to improve equitable access to LDKT for the growingly diverse population in Canada.

Keywords: living donor kidney transplantation, end-stage kidney disease, kidney transplantation, deceased donor kidney transplantation, healthy equity, access to care, social determinants of health

Abrégé

Contexte:

La transplantation rénale (TR), une des options de traitement de l’insuffisance rénale terminale (IRT), est associée à une meilleure qualité de vie et à une prolongation de la survie comparativement à la dialyse. Au Canada, les inégalités dans l’accès à la transplantation et plus particulièrement à la transplantation d’un rein provenant d’un donneur vivant (TRDV) ont été documentées selon diverses dimensions démographiques. Cet article fait état des données existantes sur les inégalités d’accès à la TR et à la TRDV des Canadiens issus de communautés marginalisées en raison de la race et de l’ethnicité.

Objectifs:

L’objectif est bipartite: 1) caractériser les données publiées sur les taux de TR et de TRDV parmi les Canadiens des communautés noires originaires d’Afrique et des Caraïbes (NAC) et les Canadiens originaires de l’Asie de l’Est et de l’Asie du Sud; 2) répondre à la question de recherche « Quels facteurs pourraient mener à un accès inéquitable à la TR pour les Canadiens des communautés NAC et des communautés est-asiatiques et sud-asiatiques? ».

Critères d’admissibilité:

Les bases de données et la littérature grise ont été passées en revue en juin et novembre 2020 à la recherche d’articles de recherche originaux (texte intégral) ou de ressources de la littérature grise traitant de l’accès à la TR ou des obstacles rencontrés par les Canadiens des communautés NAC et des communautés est-asiatiques et sud-asiatiques. En tout, 25 articles ont été analysés de façon thématique.

Sources:

La littérature grise et les bases de données CINAHL, OVID Medline, OVID Embase et Cochrane.

Méthodologie:

Les caractéristiques tirées de la littérature ont été consignées et les conclusions décrivant les taux de TR et les facteurs influençant l’accès ont été résumées sous forme de compte rendu. Les principaux thèmes ont été dégagés puis synthétisés thématiquement.

Résultats:

Les Canadiens des communautés NAC, est-asiatiques et sud-asiatiques se heurtent à divers obstacles dans l’accès à des informations et des soins médicaux adaptés à leur culture, ce qui entraîne un accès inéquitable à la TR. Le manque de connaissances concernant l’IRT et la TR, les préoccupations religieuses et spirituelles, la stigmatisation de l’IRT et de la TR, les croyances en matière de santé, les déterminants sociaux de la santé et les expériences de racisme systémique dans les soins de santé figurent parmi les possibles obstacles rencontrés.

Limites:

Cette revue inclut de la documentation dont la méthodologie varie, et la qualité des études retenues n’a pas été évaluée. Les données sur la race et l’ethnicité n’étaient pas consignées ou définies de façon normalisée. Les communautés examinées ne sont pas homogènes, les avis individuels sur le don d’organes et la TR pourraient varier.

Conclusion:

Cet examen de la portée a permis de cerner les obstacles dans l’accès à la TR et à la TRDV rencontrés par les patients des communautés marginalisées en raison de la race et de l’ethnicité. Il est urgent de poursuivre la recherche afin de mieux comprendre les obstacles et les besoins de soutien de ces communautés et pour élaborer des stratégies qui permettront un accès plus équitable à la TRDV à la population de plus en plus diversifiée du Canada.

Introduction

The benefits of kidney transplantation (KT)1-7 and living donor kidney transplantation (LDKT)1 for patients with end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) have been documented in the literature, as summarized in part 1 of this review.8 However, groups marginalized by race and ethnicity face substantial inequities in accessing KT and LDKT.9,10

The recent wave of international migration and globalization of the world have led to the development of diasporic communities, transnational identities, and the evolution of international cultural diversity.11 Canada has a foreign-born population of 7 540 830 (21.9% of the total population), and 22.3% of Canadians identify as visible minorities with an additional 4.9% identifying as Indigenous.12,13 Individuals who identify as Indigenous, East Asian, South Asian, and African, Caribbean, and Black (ACB) Canadian make up the largest populations marginalized by race and ethnicity in Canada.12 The unique histories of each community have shaped complex identities which are dependent on a multitude of factors. Part 18 of this review focused on Indigenous, whereas this Part focuses on East Asian, South Asian, and ACB Canadian communities. We chose to use these categories due to the sizes of their respective populations and the common use of these categorizations in research. We use the terminology “populations marginalized by race and ethnicity” to refer to multiple communities; rationale for the use of this terminology has been described in Part 1.8

As of 2016, more than 2 million Canadians were of East Asian (largely Chinese) origin.14 East Asian communities have lived in Canada since the 1800s, when individuals from China and Japan migrated mainly to British Columbia (BC) in search of economic opportunities in gold mining, the natural resources sector, and building the Canadian Pacific Railway.15,16 East Asian Canadians have faced discriminatory laws, policies, and practices, such as the Chinese Immigration Act and the internment of Japanese Canadians during World War II.15,16 Immigration from East Asia continues to this day, with the current East Asian community representing a diverse mosaic of multigenerational Canadians from China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Japan, and Korea.17

South Asian Canadians represent almost 6% of the Canadian population.14 The first South Asians (primarily Sikhs) arrived to Canada in the early 1900s and settled in BC.18 South Asian Canadians faced years of immigration restrictions and disenfranchisement until the 1940s.18 Less restrictive immigration policies in the 1960s allowed more South Asians to immigrate to Canada. Most of the South Asian Canadians today are first-generation individuals, with a growing proportion of second- and third-generation individuals with ancestral origins in India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, and other countries.14

The ACB Canadian population includes diverse communities which represent almost 4% of the Canadian population.14 The ACB communities have had a rich but tumultuous history in Canada. Canada participated in the transatlantic trading of stolen people, which brought thousands of Africans to Canada as slaves during the 17th and 18th centuries.19,20 During the movement to abolish slavery in the 1800s, Canada shifted its stance on slavery and became a safe haven for enslaved people fleeing the United States through passages such as the Underground Railroad. This contributed to the establishment of multigenerational Black Canadian communities.19,20 Immigration policies in the early 1900s resulted in very few Africans being permitted entry to Canada, but as restrictions were slowly lifted in the 1960s, immigration of skilled individuals from Africa and the Caribbean increased.20 The ACB communities in Canada today comprise individuals of Afro-Indigenous origin, generational Canadians, recent immigrants from and ancestral descendants of continental Africa, and diasporic ACB communities who identify with a medley of ethnic and geographic influences. These communities include 750 000 individuals of Caribbean origin who are part of a global diaspora.14,19,20

While inequitable access to health and health care has been noted for individuals belonging to populations marginalized by race and ethnicity in Canada, most of the internationally published studies describing inequitable access to KT are from the United States.21-25 Only a few studies have assessed inequitable access to KT in Canada.9,10,26,27 We described our use of “access to KT” in part 1.8

The aim of this scoping review is to characterize the currently published data on rates of KT and LDKT among East Asian, South Asian, and ACB Canadian communities and to answer the research question, “what factors may influence inequitable access to KT among East Asian, South Asian, and ACB Canadian communities?” While the review explores the broader topic of KT, there is a focus on LDKT due to the large disparity in access to LDKT among populations marginalized by race and ethnicity in Canada. A scoping review summarizing data on Indigenous communities in Canada is presented in a separate manuscript8 to allow for thorough exploration of existing evidence while considering publication word limits. A scoping review was conducted to identify and map out the available evidence and knowledge gaps on rates of and barriers to KT and LDKT among populations marginalized by race and ethnicity in Canada. With these reviews, we hope to inform further research and the development of culturally safe health care practices—those which recognize and address the roles of racism, colonialism, personal biases, and power dynamics in disadvantaging the health of populations marginalized by race and ethnicity in Canada.28 Although each community and jurisdiction have its special sets of characteristics, inequities and potential underlying factors may be somewhat generalizable. Lessons learned in one jurisdiction may inform research and actions to improve equitable access to health care resources in others.

Methods

Detailed methods for this scoping review have been described in part 1.8 Briefly, a comprehensive database search was conducted in June 2020 to identify peer-reviewed research articles and a gray literature search was conducted in November 2020. A total of 809 resources were identified and screened by N.E-D. The KT and LDKT rates and key findings which described factors that influence access to KT for East Asian, South Asian, and ACB Canadian communities were summarized here. See Supplement for database search strategies.

Results

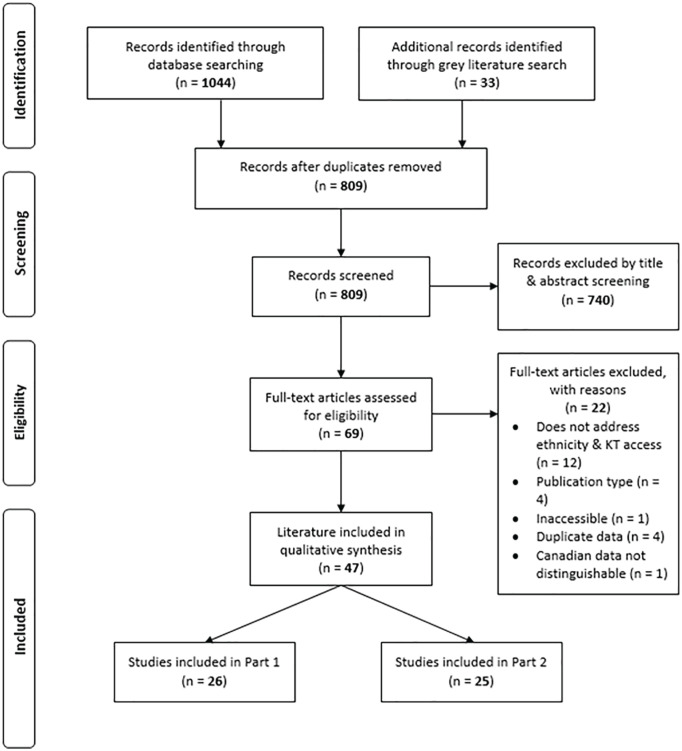

The full text of the 25 literature resources that examined East Asian, South Asian, or ACB Canadian communities was reviewed in detail (Figure 1). Of those, 48% were published within 5 years of this review (2015-2020) and 96% were published in the past 20 years. Studies mainly reported data from Ontario (48%), BC (20%), and national databases (20%). While our focus is on KT and LDKT, 48% of the articles explored the broader question of organ donation (OD) and transplantation. Key findings were summarized (Table 1); rates of KT and LDKT are presented followed by a description of the following themes which represent potential barriers identified for each community: (1) knowledge about KT and kidney disease; (2) religion and spirituality; (3) social, cultural, and family considerations; and (4) concerns related to systemic factors.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram for study screening and inclusion.

Note. PRISMA = Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Table 1.

Summary of Findings of Included Studies.

| Study | Population of interest | Study design | Literature type | Data source | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ali et al29 | South Asian, non-Muslim patients | Retrospective | Conference Abstract | Patients in Toronto | South Asian non-Muslim patients with ESKD were 52% less likely than white non-Muslims to have received an offer of living donation. |

| Alsahafi et al30 | East Asian and South Asian communities | Retrospective Cohort | Peer-Reviewed Research Article | BC Transplant Database | No significant changes in OD rates in East Asian or South Asian communities after implementation of targeted educational campaign. |

| Bansal et al31 | ACB, East Asian, and South Asian patients | Retrospective | Conference Abstract | Patients in Toronto | ACB patients with ESKD were 79% less likely, East Asian patients were 61% less likely, and South Asian patients were 58% less likely than white patients to be referred for preemptive KT. ACB patients were 77% less likely, East Asian patients were 73% less likely, and South Asian patients were 69% less likely than white patients to receive preemptive KT. |

| Canadian Council for Donation and Transplantation32 | East Asian community | Qualitative | Data Report | Chinese communities in Toronto | General lack of knowledge of OD process, criteria, and outcomes. Concerns about accepting living donation due to unknown impacts on donor. Fear of pain or disrespect during OD. Traditional, spiritual, and cultural beliefs may support and/or conflict with OD. Donation decision should be made by individuals, but important to discuss wishes with family. Age may play a role in accepting OD. Race-matching donation may be important for some. Logistical challenges may make living donation difficult (ie, employer sick leave policies). |

| Canadian Council for Donation and Transplantation33 | South Asian community | Qualitative | Data Report | South Asian communities in Vancouver and the Lower Mainland | General lack of awareness of OD in community, with potential language barriers to raising awareness. Variety of spiritual beliefs around OD. Strong willingness to donate to children or younger relatives. Challenges exist in discussing OD with family. Mistrust in health care system contributes to misconceptions about safety of living donation. |

| Coles34 | South Asian community | N/A | News Article | Unspecified | There are lower OD rates in Ontario communities that have larger proportions of populations marginalized by race. Lower awareness of the ability to register for OD, misconception and taboos around OD, and trauma (such as coming from countries with an organ trade black market) that creates worries around OD may lead to lower registration rates among South Asian communities. Language barriers and computer literacy skills may cause challenges in accessing online organ donor registration. |

| Ebrahim et al35 | Sikh community | Qualitative | Peer-Reviewed Research Article | Sikh community in Toronto | Participants believed OD to be important and in line with tenets of Sikhism (eg, selfless giving and service, sharing good fortune with the needy). Noted that some Sikh community members may be against OD. |

| Gill36 | Communities marginalized by ethnicity | N/A | Conference Presentation | Unspecified | It is understood that cultural or religious objections to donation, mistrust, and a lack of understanding of the donation process may result in disparate access to KT for communities marginalized by ethnicity. |

| Gupta et al37 | ACB patients | Retrospective | Conference Abstract | Patients in Toronto | ACB KT candidates were 63% less likely to have received an offer of living donation and 62% less likely to have a living donor identified than white KT candidates. ACB patients were more hesitant than white patients to engage in actions such as talking to others about their need for LDKT, asking a donor directly, or sharing educational materials about LDKT with potential donors. |

| Li et al38 | ACB, East Asian, and South Asian immigrant communities | Cross-sectional | Peer-Reviewed Research Article | Ontario Registered Persons Database, IRCC Permanent Resident Database | Immigrants born in sub-Saharan Africa and East Asia were least likely groups to be registered for OD. |

| Li et al39 | East Asian and South Asian communities | Retrospective Cross-sectional, Retrospective Cohort | Peer-Reviewed Research Article | Ontario Registered Persons Database, Trillium Gift of Life Network Database, CIHI Discharge Abstract Database | Chinese and South Asian Canadians were 2 to 3 times less likely to register their consent for deceased OD compared with the general public. Families of potential Chinese or South Asian donors were less likely to provide consent for deceased OD compared with the general public, although the differences were not large. |

| Li et al40 | ACB, East Asian, and South Asian immigrant donor families | Retrospective Cohort | Peer-Reviewed Research Article | Ontario Registered Persons Database, Trillium Gift of Life Network Database, CIHI Discharge Abstract Database, IRCC Permanent Resident Database | Families of South Asian, East Asian, North African, and sub-Saharan African immigrants were less likely to provide consent for OD compared with families of long-term residents. |

| Molzahn et al41 | South Asian community | Qualitative | Peer-Reviewed Research Article | Indo-Canadian community members in British Columbia | General knowledge about OD in community, but not about provincial system. Religion not perceived as barrier to OD, but important to consider rituals and practices at time of death for deceased donation. Family and community context influences attitudes around OD. General dislike of communicating about death and OD. OD decision may individual or may involve family. Conditional willingness to be a living donor, especially to a child or emotionally close recipient. OD seen as a good thing to do. Positive view of healthcare system but fear of receiving inadequate health care during donation. |

| Molzahn et al42 | East Asian community | Qualitative | Peer-Reviewed Research Article | Chinese community members in Vancouver | General lack of knowledge of provincial OD system. Traditional beliefs, spiritual views, and religious values intermingle to shape attitudes around OD. Greater level of comfort in being a living donor to family, child, or emotionally close recipient. Donation decisions would likely be individual. Willingness to donate differs by age, length of immigration, and how beliefs have been influenced by “Western culture.” Filial piety and respect for parents/ancestors as a deterrent to donation. Fears about physicians being too hasty to remove organs from donors. |

| Mucsi et al9 | ACB, East Asian, and South Asian patients | Retrospective Cohort | Peer-Reviewed Research Article | Toronto General Hospital Database | ACB patients were 22% less likely to complete kidney transplant evaluation within 2 years of referral than white patients. ACB, East Asian, and South Asian Canadian patients were 65%, 73%, and 57% less likely to receive LDKT, respectively, than white patients. |

| Schaubel et al43 | ACB, East Asian, and South Asian patients | Retrospective | Peer-Reviewed Research Article | Canadian Organ Replacement Register | Sex disparities in KT access exist in all communities in Canada. White and East Asian men are 18% and 23% more likely to receive KT than women from the communities, and Black, South Asian, and Indigenous men are 66%, 67%, and 42% more likely to receive KT than women from the communities, respectively. |

| Sherry et al44 | ACB community | Qualitative | Peer-Reviewed Research Article | Haitian community members in Montreal | General knowledge of OD in community. OD seen as a taboo topic. Strong level of mistrust in research and health care, with concerns that physicians would save organs but not patients. Beliefs about body wholeness and the act of OD interfering with going to heaven in conflict with OD. Variation in OD attitudes by age. Donation seen as a personal decision that should not be made by family. |

| Singh et al45 | ACB living kidney donors | Retrospective | Conference Abstract | Donors in Toronto | Between 2006 and 2015, ACB living kidney donor candidates were less likely to donate their kidney than non-ACB living kidney donor candidates. |

| Tonelli et al27 | East Asian and South Asian patients | Retrospective Cohort | Peer-Reviewed Research Article | Canadian Organ Replacement Register | East Asian and South Asian patients significantly less likely to receive KT than white patients, with differences more pronounced for LDKT. |

| University Health Network46 | ACB and South Asian patients | N/A | News Article | Unspecified | Language and cultural differences, trust and representation in the healthcare system, and fear of being misjudged can all impact how patients are able to access healthcare related to LDKT. Saving a life is a way to manifest the honor that is valued in South Asian cultures. It is difficult to debunk preconceptions that people have around transplant. |

| Vedadi et al26 | ACB, East Asian, and South Asian patients | Retrospective Cohort | Peer-Reviewed Research Article | Toronto General Hospital Database | ACB, East Asian, and South Asian patients were 51%, 66%, and 33% less likely than white patients to have a potential living donor identified at the first pretransplant assessment, respectively. Patients who did not have a potential living donor identified at the first pretransplant assessment were 86% less likely to receive LDKT or any KT within 8 years of referral than patients who had at least one potential LD identified at that time. |

| Wong et al47 | ACB and Asian patients | Retrospective | Conference Abstract | Patients in Toronto | ACB patients with ESKD had lower transplant knowledge than white patients after adjusting for confounding factors. |

| Yeates et al48 | ACB patients | Retrospective Cohort | Peer-Reviewed Research Article | Canadian Organ Replacement Register | Black patients were significantly less likely to receive DDKT, LDKT, or either, in comparison with white patients. |

| Yeates et al10 | ACB, East Asian, South Asian, and Indigenous patients | Retrospective Cohort | Peer-Reviewed Research Article | Canadian Organ Replacement Register | South Asians, ACB, and Indigenous patients had lower rates of DDKT and LDKT compared with white patients, with rates even lower for LDKT and worsening over time. |

| Yoshida et al49 | ACB, East Asian, South Asian, and Indigenous patients | Retrospective | Peer-Reviewed Research Article | BC Transplant Database | White patients represented 65%, East Asian patients represented 19.8%, ACB Canadian patients represented 1.7%, Indigenous patients represented 4.1%, and South Asian patients represented 7.2% of total KT recipients in the province. KT recipients exhibited the most racial heterogeneity compared with other organ transplant groups. |

Note. ESKD = end-stage kidney disease; OD = organ donation; ACB = African, Caribbean, and Black; KT = kidney transplantation; LDKT = living donor kidney transplantation; DDKT = deceased donor kidney transplantation ; IRCC = Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada; CIHI = Canadian Institute for Health Information; LD = living donor.

The data describe how East Asian, South Asian, and ACB Canadian patients have a lower likelihood of receiving KT and LDKT compared with white patients. A variety of factors related to knowledge, spirituality, culture, family, and systems may influence how patients and communities access OD, KT, and LDKT.

East Asian Communities in Canada

Rates of KT and LDKT

East Asian Canadians have a lower likelihood of receiving a KT compared with white patients.9,27,49 An analysis of BC data49 reported that East Asian and white patients represented 20% and 65% of all KT recipients, respectively. However, authors did not report a reference prevalence of ESKD in the different communities. National and local-level data have shown that East Asian compared with white Canadians were 29% and 73% less likely to receive KT and LDKT, respectively.27,31 Data from Toronto indicated that East Asian compared with white patients were also 66% less likely to have a potential living donor identified at their first pretransplant assessment, which predicted a significantly lower likelihood of subsequently receiving LDKT.26 In addition, East Asian patients were 61% less likely to be referred for preemptive KT and 73% less likely to receive preemptive KT than white patients.31

Knowledge about KT and kidney disease

Qualitative studies have identified questions and concerns around the OD process in focus groups with Chinese communities, including eligibility for deceased and living donation and the unknown, negative long-term health effects of living donation.32,42 Participants felt that additional information was necessary to make decisions about donation, especially around age cut-offs and health status of donors.32 However, there was no significant change in donation rates after the implementation of a targeted public education campaign about OD in East Asian communities in BC.30 This demonstrates the need for more research to understand the specific concerns and support needs of the community.

Religion and spirituality

Traditional beliefs, spiritual views, and religious values shape both positive and negative attitudes toward OD.32,36,42 The commonly held Confucian value of caring for the body out of respect for elders and ancestors and the virtue of filial piety have been noted32,42 to influence beliefs around OD in East Asian cultures. Specifically, the importance of maintaining an intact body after death and the impact that donation may have on reincarnation can lead to opting out from both deceased and living OD.32,42 Furthermore, death is often seen as taboo in Chinese culture, making it difficult to discuss deceased OD and transplantation.42 While these concerns must be addressed sensitively, the value of generosity in Chinese culture and the view that OD is seen as an act of kindness has also been documented.32,42 Similarly, receiving a transplant is considered an event of good fortune in Chinese culture.42

Social, cultural, and family considerations

Although health care decision making is a family-involved process in traditional Chinese culture, qualitative studies showed that OD is generally considered an individual choice.32,42 This may be in part because of the difficulty associated with having discussions about death and deceased OD.42 Such challenges may be implicated in a series of studies which showed that Chinese Canadian individuals and families were less likely than the general public to register or provide their consent for OD and that East Asian immigrants were the least likely group to have registered their consent for OD.38,39,40 Despite these difficulties, discussing one’s last wishes beforehand are thought to potentially mitigate the possibility of a veto of a donation decision by families.32,42 In addition, requests for OD were thought to be more well-received if presented by a physician and/or spiritual leader.42

Living OD to family members or close friends was considered more acceptable, and participants were unanimously willing to donate to a child if needed.42 While older Chinese Canadians may be less willing to donate than younger generations, it was noted that parents would be more willing to donate to their children, but the reverse would not be well accepted.42 Age and time since immigration impacted attitudes toward donation and transplant; acculturation of younger Chinese Canadians was thought to favor OD, which is considered to be associated with Western culture.32,42 Knowing the characteristics of the potential recipient—including whether they were of Chinese origin or whether they were a “good person”—was important to some but not all participants.32 In addition, sex disparities in access to KT persist across many communities, including East Asian communities across Canada, although reasons for this remain unclear.43

Concerns related to systemic factors

Mistrust, fears, concerns, and a lack of understanding about the OD process can act as potential deterrents to both living and deceased donation.36 Focus group participants expressed worry about experiences of pain and disrespect during the OD surgery and process.32 Similar to the general public, Chinese community members in Vancouver expressed fears around the potential hastiness of physicians to remove organs from registered donors without ensuring that all life-saving measures had taken place.42 There is also a clear need for supports for living donors in the workplace, as study participants expressed concerns around the feasibility of donating if an employer would not support sick leave required after living OD.32

South Asian Communities in Canada

South Asian Canadians continue to experience inequitable access to KT and LDKT. South Asian Canadians represented 7.2% of all KT recipients in BC,49 although no reference prevalence of ESKD was provided. National and local analyses have shown that South Asian patients with ESKD were 29% to 31% less likely to receive KT and 57% to 75% less likely to receive LDKT compared with white patients.10,27,31 Data from Toronto showed that South Asian compared with white patients were 33% less likely to have a potential donor identified at their first pretransplant assessment.26 South Asian, non-Muslim compared with white, non-Muslim patients with ESKD were 52% less likely to have received a donation offer from a potential living donor.29 South Asian compared with white patients were 58% less likely to be referred for and 69% less likely to receive preemptive KT.31

Knowledge about KT and kidney disease

Qualitative studies have shown that while OD is generally understood in the community, many individuals have a low level of awareness of OD, its importance in the South Asian community, and how the process works.33,41 Individuals have concerns about living OD, including safety and long-term outcomes.33 Organ donation was noted to be a topic not commonly discussed unless compelled by the need for a transplant in a close acquaintance.33 Low awareness of the OD registration process may also lead to lower registration rates among South Asian communities.34 Although education may help to raise awareness of OD, donation rates in the South Asian community did not change following a targeted educational campaign.30

Religion and spirituality

In general, OD is considered to be a good deed.41 While some community members highlighted the importance of individual perceptions and understandings in shaping their beliefs around OD, others emphasized the ways in which their religious values either supported or opposed OD.33,41 For example, Sikh and Hindu values around selfless giving and sharing were seen to be supportive of OD33,35 although some community members may still oppose it.35 In addition, a lack of clarity regarding the Islamic rulings on OD led to some hesitance among Muslim participants, who felt it important to understand the religion’s position on OD before making a decision.50 These findings underscore the need for open dialogue about OD in diverse religious communities.33,51

The idea that donation may be considered an unwanted interference in a divine plan for one’s life and death was a concern to some South Asian Canadians.33,41 Both donating and accepting an organ were considered by some to be a way of prolonging life in a manner that might oppose the will of God.33 Ultimately, living and dying in a manner consistent with religious values was an important consideration.41 With deceased donation in particular, participants noted the need to consider and understand the different rituals and practices around death and burial to allow donation to proceed in a respectful and noninterfering manner.41

Social, cultural, and family considerations

Family and community are important in South Asian cultures.41 Living donation to family members and children was largely supported by focus group participants41 and saving a life through living donation may be considered a form of honor which is valued in many South Asian cultures.46 Although participants indicated that their decision to donate would likely be made individually, the opinions of older family members were noted to be influential and needed to be respected.41 However, discussing OD, and particularly deceased donation, with family members was viewed as challenging,33,41 which may help explain why South Asian Canadians were only half as likely to register,39 and why their families were less likely to consent for deceased OD, compared with others.39,40 Common misconceptions and taboos around OD, in combination with language barriers, may be implicated in reduced OD rates and access to KT among South Asian communities.34,46 Sex disparities in KT, as in other communities, were present among South Asian Canadians.43 The reasons for these disparities, however, remain unclear.

Concerns related to systemic factors

A mix of views around the health care system was documented in qualitative studies.33,41 While some participants expressed positive views and indicated trust in health care professionals, they also had concerns about receiving adequate healthcare if they decided to become an organ donor.33,41 While systemic trust was reinforced by positive personal experiences, fears—specifically regarding OD—were noted by participants who had negative personal experiences.33 Anecdotes and traumatic experiences related to illegal organ trade practices abroad can create skepticism and worry around the OD process33,34 and have the power to foster general mistrust of health care and OD systems regardless of the country in which the practice occurred.

ACB Communities in Canada

Barriers that African Americans face in accessing KT and LDKT have been well documented in the United States52; research on ACB Canadians has been limited. Despite their shared experiences of systemic racism, there are substantial differences between the 2 populations. Canadian data demonstrated that ACB compared with white patients with ESKD were 65% to 69% less likely to receive LDKT.10,48 The ACB patients compared with white patients in Toronto were also half as likely to have a potential living donor identified at the time of their first pretransplant assessment26 and 63% less likely to have received an offer of donation from a potential living donor.37 There was a greater expressed hesitance around talking to others about one’s need for LDKT, asking someone directly to consider donation, or sharing educational materials on LDKT with potential donors among ACB compared with white patients.37 The ACB patients were also more than 70% less likely to be referred for or to receive preemptive KT.31 Interestingly, ACB compared with white living kidney donor candidates were also less likely to undergo donation.45

Knowledge about KT and kidney disease

There is a paucity of literature on knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs regarding OD in ACB Canadian communities. Haitian community members in Montreal44 displayed varying levels of knowledge about OD, ranging from a limited understanding of the concept and process to some knowledge based on anecdotal or personal experience.44 Study participants expressed a general willingness and interest in learning more about OD.44 However, this sample may not be representative of the broader ACB Canadian communities, and further exploration with a more diverse sample is required.

Religion and spirituality

Cultural and religious objections to OD are posited to contribute to disparate rates of KT among communities marginalized by race and ethnicity.36 A range of beliefs both supporting and opposing OD underscored the importance of religion in the Haitian Canadian community; some participants preferred to “go to God whole,” whereas others were willing to become donors as long as doing so did not interfere with their going to heaven.44

Social, cultural, and family considerations

While some qualitative study participants were supportive of OD in general, others were not.44 Some noted that OD is viewed as primarily benefiting white people, indicating potential systemic mistrust and a possible lack of understanding of the need for OD in the Haitian Canadian community.44 Nevertheless, OD was seen as an ultimately personal decision that should be made by the potential donor.44 However, Canadian immigrants from sub-Saharan Africa also had lower rates of registration for OD than the general public, and families of immigrants from North or sub-Saharan Africa were less likely to consent for OD compared with long-term residents.38,40 Factors such as language barriers and cultural differences are suspected to be implicated in disparate access to KT.36,46 In the Haitian Canadian community, older generations were seen to be less open to donation than younger generations, who may have been influenced by “Canadian societal values.”44 Sex disparities in KT access were more pronounced in ACB Canadian than other communities, although the reasons for these findings are unclear.43

Concerns related to systemic factors

A recent analysis found that ACB Canadian patients were uniquely less likely to complete transplant evaluation than white patients, indicating potential systemic barriers in the transplant pathway specifically affecting ACB patients.9 Mistrust of the health care system was noted in qualitative research with Haitian Canadians, who expressed reservations about providing focus group consent due to concerns that it would be interpreted as consent for OD.44 These concerns were rooted in participants’ expressed personal experiences of being “taken advantage of.”44 Similarly, study participants voiced a belief that registered organ donors received inadequate treatment by physicians, who may be more interested in saving organs than saving the donor’s life.44 Participants suggested including Haitian community leaders and health care professionals to lead education on OD in the community, indicating a greater level of trust within rather than with the “outside” community.44 Mistrust, lack of representation in the health care system, and a fear of being misjudged have all been noted to negatively impact access to KT among ACB patients and communities.36,46

Discussion

We summarized the published evidence about inequitable access to KT and LDKT for patients from populations marginalized by race and ethnicity in Canada. Research across the country has shown that patients from Indigenous, East Asian, South Asian, and ACB Canadian communities are substantially less likely to receive KT or LDKT compared with white patients,9,10,26,27,48,49 although a recent publication indicates that disparities in KT referral rates may not be the culprit.53 However, there remain a paucity of recent data on the prevalence of ESKD, KT, and LDKT in these communities. Efforts to systematically and safely collect and report race-disaggregated data on the topic are needed.

While some research has been conducted to understand factors which influence attitudes, opinions, and behaviors around OD and KT in specific cultures and religions, there is a clear need for more research, especially for ACB Canadian communities. The existing research shows that while personal and anecdotal experience with KT provides individuals and communities with some understanding of the concept, gaps in knowledge remain across all groups about the OD process, donor eligibility, and donation safety.32,33,41,42,44,54 However, considering the lack of impact of a standard educational campaign on OD targeted to populations marginalized by race and ethnicity in BC,30 traditional educational approaches may not be sufficient. Culturally appropriate education on OD and KT that is and designed and delivered in ways that are in line with cultural ways of being is needed to facilitate effective uptake. Organ procurement organizations (OPOs) and transplant programs must work to understand the specific concerns and needs of diverse communities to implement culturally appropriate public education on OD.55

One such important factor is religion and spirituality. Each community examined in this review has certain unique and shared religious and spiritual views that influence perceptions of the acceptability and appropriateness of OD and KT. For example, commonly held values such as filial piety or caring for the body out of respect for ancestors are unique deterrents to OD in East Asian communities, whereas in South Asian communities, respect for rituals and rites around death and lack of clarity around the religious permissibility of OD can create hesitation to accept OD.32,33,41,42 Multiple communities voiced concerns about maintaining an intact body after death or worries that OD constitutes an interference with fate.32,33,42,44,54,56 Ultimately, religious, spiritual, and cultural beliefs regarding charity, generosity, benevolence in relation to OD, and good luck associated with receiving an organ, were critical supporting values that encouraged OD and KT across communities.32,33,35,42,54 In addition, supporting the continuation of one’s culture through donation was a unique factor which influenced views on the acceptability of KT among Indigenous communities.54 Although emphasizing spiritual beliefs that support OD could help improve its acceptability, it is important to approach religiously tailored health behavior change in an ethically responsible manner which supports a balanced consideration of OD.57

In addition to religious concerns, various groups expressed preferences to donate an organ to someone with whom the donor had a close relationship, to a “good person,” and in certain instances, to someone belonging to the same community.32,41,54 Preferences for directed donation to the same community may be rooted in the history of colonialism, experiences of racism and oppression, and systemic mistrust which are responsible for many of the inequities faced by communities in Canada.54,58,59 These preferences may also be influenced by motivations such as one’s connection to their community and desire to support the continuation of their culture, as described for Indigenous communities.55 Directed living donation similar to the RENEWAL model employed by the Jewish community in New York60 could be considered to enhance communities’ comfort with OD and increase the number of living donations in communities. This would also shorten the waitlist and improve access to deceased donor kidney transplantation for others. However, such a model would require thorough ethical consideration and an implementation and monitoring plan that ensured equitable and improved access for communities experiencing the greatest disparities to avoid widening the gap.

Studies noted age-, generation-, and immigration-related variation in views on the acceptability and appropriateness of OD and KT. A common theme within East Asian, Indigenous, and some ACB Canadian communities was that younger individuals may be more open to OD, as they may be more influenced by Western values than older generations.32,42,44,61 While acculturation can influence the values and beliefs of individuals,62-64 it is important to recognize the role that Eurocentric biases play in acculturation such that non-Western ways (ie, values and beliefs opposing OD and transplantation) are viewed as primitive or unfavorable.65 This stance may alienate potential transplant recipients and donor candidates, as feeling that their values are rejected by the system can impact their ability and willingness to engage with the transplant system. Culturally safe approaches need to establish and strengthen the alignment between potentially conflicting values and practices.

Spanning generations and immigration status, systemic concerns regarding OD were common among members of all communities marginalized by race and ethnicity included in this review. Worries about experiences of pain and disrespect during OD surgery, respect for the body, and concerns that doctors would not do everything possible to preserve the donor’s life may be related to negative experiences in the health care system.32,33,42 Personal and anecdotal experience of the illegal organ trade in other countries is often cited as a source of mistrust in the Canadian medical system among South Asian Canadians.33 Experiences of lived and historical anti-Black and anti-Indigenous racism within and outside of health care, the history of colonialism in Canada, and intergenerational trauma contribute to mistrust in the healthcare system in ACB Canadian and Indigenous communities, and it is important to acknowledge the different sources of such mistrust.44,66 Additional concerns about the affordability and availability of KT and LDKT were noted most prominently among Indigenous communities in Canada, who may experience challenges in traveling to transplant centers due to forced relocation as well as in the KT reimbursement process stemming from colonialist policies.67-69 Understanding the historic, lived, and social context of beliefs regarding the acceptability, appropriateness, affordability, and availability of OD and KT provides valuable insight into why populations marginalized by race and ethnicity experience inequitable access to OD, KT, and LDKT.40 This is also a key step in starting to address systemic concerns and enable the provision of culturally safe, equitable care to historically disadvantaged communities.

Limitations

This review is an overview of the existing literature on access to KT and LDKT in populations marginalized by race and ethnicity in Canada; however, its limitations need to be considered. The quality of the included literature has not been systematically evaluated. The reviewed literature employed a wide range of methodologies with their own inherent limitations. Data on ethnicity or race were not collected or reported in a standardized manner, nor did all studies state whether ethnicity or race was self-identified. The groups included are also very diverse in and of themselves, and attitudes and opinions on OD may differ significantly from person to person and are not limited to those documented in the literature. We also acknowledge that there are additional ethnic groups in Canada that are not represented in this review.

Conclusions

From our 2 reviews, it is evident that Indigenous, East Asian, South Asian, and ACB Canadians with ESKD are less likely to receive KT or LDKT compared with white and non-Indigenous patients. In addition to barriers imposed by systemic racism and socioeconomic disparities in these communities, a variety of cultural and spiritual values, beliefs, and experiences relevant to health impact individuals’ and communities’ views regarding the acceptability, appropriateness, affordability, and availability of OD, KT, and LDKT. Importantly, future work is needed to understand the systemic barriers that limit access to KT for these communities in order for health care providers, transplant programs, and OPOs to identify, codevelop with affected communities, and implement sustainable strategies to improve equitable access to KT and LDKT. Acknowledging that patients from Indigenous, East Asian, South Asian, and ACB Canadian communities experience inequitable access to KT and LDKT, the health care system must assume responsibility for building meaningful relationships with these communities to work together toward an improved understanding of the factors, including systemic racism, that create health inequities and to design community-informed frameworks to enable equitable access to transplant care for all Canadians.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-cjk-10.1177_2054358121996834 for Barriers to Accessing Kidney Transplantation Among Populations Marginalized by Race and Ethnicity in Canada: A Scoping Review Part 2—East Asian, South Asian, and African, Caribbean, and Black Canadians by Noor El-Dassouki, Dorothy Wong, Deanna M. Toews, Jagbir Gill, Beth Edwards, Ani Orchanian-Cheff, Paula Neves, Lydia-Joi Marshall and Istvan Mucsi in Canadian Journal of Kidney Health and Disease

Footnotes

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate: Ethics approval and consent were not obtained as secondary data were used for this scoping review.

Consent for Publication: All co-authors reviewed this final manuscript and consented to its publication.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data and materials that support the findings of this scoping review are available from the corresponding author I.M. upon reasonable request.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: J.G., P.N. and I.M. are the recipient of a research grant from the Health Care Policy Contribution Program of Health Canada (1920-HQ-000109) entitled: “Improving Access to Living Donor Kidney Transplantation (LDKT) in Communities Marginalized by Race and Ethnicity in Canada.”

ORCID iDs: Ani Orchanian-Cheff  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9943-2692

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9943-2692

Istvan Mucsi  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4781-4699

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4781-4699

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. de Groot IB, Veen JI, van der Boog PJ, et al. Difference in quality of life, fatigue and societal participation between living and deceased donor kidney transplant recipients. Clin Transplant. 2013;27(4):E415-E423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Evans RW, Manninen DL, Garrison LP. The quality of life of patients with end-stage renal disease. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:553-559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Molnar MZ, Novak M, Mucsi I. Sleep disorders and quality of life in renal transplant recipients. Int Urol Nephrol. 2009;41(2):373-382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Neipp M, Karavul B, Jackobs S. Quality of life in adult transplant recipients more than 15 years after kidney transplantation. Transplantation. 2006;81:1640-1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ortiz F, Aronen P, Koskinen PK. Health-related quality of life after kidney transplantation: who benefits the most. Transpl Int. 2014;27(11):1143-1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pinson CW, Feurer ID, Payne JL. Health-related quality of life after different types of solid organ transplantation. Ann Surg. 2000;232(4):597-607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. KSC Network. Alberta annual kidney care report: prevalence of severe kidney disease and use of dialysis and transplantation across Alberta from 2004–2013. Edmonton, AB: Alberta Health Services; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 8. El-Dassouki N, Wong D, Toews D, et al. Barriers to accessing kidney transplantation among populations marginalized by race and ethnicity in Canada: A scoping review part 1—indigenous communities in Canada. Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2021;8:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mucsi I, Bansal A, Famure O, et al. Ethnic background is a potential barrier to living donor kidney transplantation in Canada: a single-center retrospective cohort study. Transplantation. 2017;101(4):e142-e151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yeates KE, Schaubel DE, Cass A, Sequist TD, Ayanian JZ. Access to renal transplantation for minority patients with ESRD in Canada. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;44(6):1083-1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Investing in cultural diversity and intercultural dialogue: UNESCO World Report. UNESCO; 2009. https://en.unesco.org/interculturaldialogue/resources/130. Accessed February 10, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Statistics Canada. Immigration and ethnocultural diversity: key results from the 2016 Census. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/171025/dq171025b-info-eng.htm. Published 2017. Accessed February 10, 2021.

- 13. Aboriginal peoples in Canada: Key results from the 2016 Census. Statistics Canada. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/171025/dq171025a-info-eng.htm. Published October 25, 2017. Accessed February 10, 2021.

- 14. Statistics Canada. Ethnic origin (279), single and multiple ethnic origin responses (3), generation status (4), age (12) and sex (3) for the population in private households of Canada, provinces and territories, census metropolitan areas and census agglomerations, 2016 census—25% sample data. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/dt-td/Rp-eng.cfm?TABID=1&LANG=E&A=R&APATH=3&DETAIL=0&DIM=0&FL=A&FREE=0&GC=12&GL=-1&GID=1341682&GK=1&GRP=1&O=D&PID=110528&PRID=10&PTYPE=109445&S=0&SHOWALL=0&SUB=0&Temporal=2017&THEME=120&VID=0&VNAMEE=&VNAMEF=&D1=0&D2=0&D3=0&D4=0&D5=0&D6=0. Published 2016. Accessed February 10, 2021.

- 15. Japanese Canadian History. Japanese Canadian history: historical overview. https://japanesecanadianhistory.net/historical-overview/general-overview/. Published 2020. Accessed February 3, 2020.

- 16. Statistics Canada. History of Canada’s early Chinese immigrants. https://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/discover/immigration/history-ethnic-cultural/early-chinese-canadians/Pages/history.aspx. Published April 19, 2017. Accessed February 10, 2021.

- 17. Statistics Canada. Census in brief—ethnic and cultural origins of Canadians: portrait of a rich heritage. https://hive.utsc.utoronto.ca/public/principal/Ethnic%20and%20cultural%20origins.pdf. Published October 25, 2017. Accessed February 10, 2021.

- 18. South Asian Canadian Heritage. History of South Asians in Canada: timeline. https://www.southasiancanadianheritage.ca/history-of-south-asians-in-canada/. Accessed February 10, 2021.

- 19. Library and Archives Canada. Black history in Canada. Library and Archives. https://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/discover/immigration/history-ethnic-cultural/Pages/blacks.aspx. Published 2019. Accessed February 10, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 20. The Canadian Encyclopedia. Timeline: Black history. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/timeline/black-history. Accessed February 10, 2021.

- 21. Klassen AC, Hall AG, Saksvig B, Curbow B, Klassen DK. Relationship between patients’ perceptions of disadvantage and discrimination and listing for kidney transplantation. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(5):811-817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Purnell TS, Powe NR, Troll MU, et al. Measuring and explaining racial and ethnic differences in willingness to donate live kidneys in the United States. Clin Transplant. 2013;27(5):673-683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ayanian JZ, Cleary PD, Weissman JS, Epstein AM. The effect of patients’ preferences on racial differences in access to renal transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(22):1661-1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Purnell TS, Hall YN, Boulware LE. Understanding and overcoming barriers to living kidney donation among racial and ethnic minorities in the United States. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2012;19(4):244-251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Waterman AD, Peipert JD, Hyland SS, McCabe MS, Schenk EA, Liu J. Modifiable patient characteristics and racial disparities in evaluation completion and living donor transplant. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8(6):995-1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Vedadi A, Bansal A, Yung P, et al. Ethnic background is associated with no live kidney donor identified at the time of first transplant assessment-an opportunity missed? a single-center retrospective cohort study. Transpl Int. 2019;32(10):1030-1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tonelli M, Hemmelgarn B, Gill JS, et al. Patient and allograft survival of Indo Asian and East Asian dialysis patients treated in Canada. Kidney Int. 2007;72(4):499-504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ballon D. Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy for English-Speaking People of Caribbean Origin: A Manual for Enhancing the Effectiveness of CBT for English-Speaking People of Caribbean Origin in Canada. Toronto, ON, Canada: Centre for Addictions and Mental Health; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ali A, Ayub A, Richardson C, et al. South Asian and Muslim Canadian patients are less likely to receive living donor kidney transplant offers compared to Caucasian, non-Muslim patients. Transplantation. 2018; 102(7 suppl 1):S502. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Alsahafi M, Leung L, Partovi N, Yee J, Yoshida EM. Racial differences between solid organ transplant donors and recipients in British Columbia 2005-2009: a follow-up study since the last analysis in 1993-1997. Transplantation. 2013;95(11):e70-e71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bansal A, Kwok M, Cao S, Famure O, Kim S, Mucsi I. Ethnocultural barriers to pre-emptive kidney transplantation: a single centre retrospective cohort study. Am J Transplant. 2017;17(suppl 3):631. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Canadian Council for Donation and Transplantation. Consultation to explore peoples’ views on organ and tissue donation: Discussion with Chinese Canadians—summary report to participants. Edmonton, AB: Canadian Council for Donation and Transplantation; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Canadian Council for Donation and Transplantation. Consultation to explore peoples’ views on organ and tissue donation: discussions with South Asian Canadians—summary report to participants. Edmonton, AB: Canadian Council for Donation and Transplantation; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Coles T. Why GTA cities drag down Ontario’s organ donation rates. TVO. Published October 24, 2016. https://www.tvo.org/article/why-gta-cities-drag-down-ontarios-organ-donation-rates.

- 35. Ebrahim S, Bance S, Bowman KW. Sikh perspectives towards death and end-of-life care. J Palliat Care. 2011;27(2):170-174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gill J. Addressing disparities in kidney transplantation. Paper presented at the BC Kidney Days. Vancouver, BC; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gupta V, Richardson C, Belenko D, et al. Attitudes of African Canadian patients with end stage kidney disease toward living donor kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2018;18(suppl 4):817. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Li A, Dixon S, Prakash V, Garg A. Registration for deceased organ and tissue donation amongst new Canadians: a population based study. Transplantation. 2015;99(10):S98. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Li AH, McArthur E, Maclean J, et al. Deceased organ donation registration and familial consent among Chinese and South Asians in Ontario, Canada. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(7):e0124321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Li AH, Al-Jaishi AA, Weir M, et al. Familial consent for deceased organ donation among immigrants and long-term residents in Ontario, Canada: a population-based retrospective cohort study. Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2017;4:2054358117735564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Molzahn AE, Starzomski R, McDonald M, O’Loughlin C. Indo-Canadian beliefs regarding organ donation. Prog Transplant. 2005;15(3):233-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Molzahn AE, Starzomski R, McDonald M, O’Loughlin C. Chinese Canadian beliefs toward organ donation. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(1):82-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Schaubel DE, Stewart DE, Morrison HI, et al. Sex inequality in kidney transplantation rates. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2000;160(15):2349-2354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sherry W, Tremblay B, Laizner AM. An exploration of knowledge, attitudes and beliefs toward organ and tissue donation among the adult Haitian population living in the Greater Montreal Area. Dynamics. 2013;24(1):12-18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Singh S, DiCecco V, Luo M, Li Y, Famure O. Temporal trends in living kidney donor candidates. Am J Transplant. 2018;18(suppl 4):820-821. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Representation matters, also in healthcare. University Health Network. https://www.uhn.ca/corporate/News/Pages/Representation_matters_also_in_healthcare.aspx. Published October 8, 2020. Accessed February 10, 2021.

- 47. Wong D, Ford H, Lok C, et al. Ethnicity and transplant knowledge among Canadian ESKD patients. Am J Transplant. 2017;17(suppl 3). [Google Scholar]

- 48. Yeates K, Wiebe N, Gill J, et al. Similar outcomes among black and white renal allograft recipients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20(1):172-179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Yoshida EM, Partovi N, Ross PL, Landsberg DN, Shapiro RJ, Chung SW. Racial differences between solid organ transplant donors and recipients in British Columbia: a five-year retrospective analysis. Transplantation. 1999;67(10):1324-1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Consultation to explore people’s views on organ and tissue donation: discussions with South Asian Canadians. Edmonton, AB: Canadian Council for Donation and Transplantation; 2005. http://www.publications.gc.ca/site/eng/9.507316/publication.html. Accessed February 10, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ali A, Ahmed T, Ayub A, et al. Organ donation and transplant: the Islamic perspective. Clin Transplant. 2020;34(4):e13832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Navaneethan S, Singh S. A systematic review of barriers in access to renal transplantation among African Americans in the United States. Clin Transplant. 2006;20(6):769-775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kim SJ, Gill J, Knoll G, et al. Referral for kidney transplantation in Canadian provinces. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019;30(9):1708-1721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Consultation to explore people’s views on organ and tissue donation: discussions with indigenous peoples. Edmonton, AB: Canadian Council for Donation and Transplantation; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kreuter MW, Lukwago SN, Bucholtz DC, Clark EM, Sanders-Thompson V. Achieving cultural appropriateness in health promotion programs: targeted and tailored approaches. Health Educ Behav. 2003;30(2):133-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Vescera Z. Doctors and elders unite to pursue equity in organ donations. Saskatoon Starphoenix. June 16, 2020. https://thestarphoenix.com/news/local-news/sask-network-pushes-for-equity-in-organ-donations. Accessed February 10, 2021.

- 57. Padela AI, Malik S, Vu M, Quinn M, Peek M. Developing religiously-tailored health messages for behavioral change: introducing the reframe, reprioritize, and reform (“3R”) model. Soc Sci Med. 2018;204:92-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Adelson N. The Embodiment of Inequity. Can J Public Health. 2005;96(suppl 2):S45-S61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future: Summary of the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. https://opentextbc.ca/indigenizationcurriculumdevelopers/back-matter/appendix-a/. Published 2015. Accessed February 10, 2021.

- 60. Renewal. Renewal: What We Do. https://www.renewal.org/whatwedo. Published 2017. Accessed February 10, 2021.

- 61. Molzahn AE, Starzomski R, McDonald M, O’Loughlin C. Aboriginal beliefs about organ donation: some Coast Salish viewpoints. Can J Nurs Res. 2004;36(4):110-128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Marin G, Gamba RJ. Acculturation and changes in cultural values. In: Chun KM, Balls Organizsta P, Marin G, eds. Acculturation: Advances in Theory, Measurement, and Applied Research. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2003:83-93. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Wu Q, Ge T, Emond A, et al. Acculturation, resilience, and the mental health of migrant youth: a cross-country comparative study. Public Health. 2018;162:63-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Berry JW, Hou F. Acculturation, discrimination and wellbeing among second generation of immigrants in Canada. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 2017;61:29-39. [Google Scholar]

- 65. Rudmin F, Wang B, de Castro J. Acculturation research critiques and alternative research designs. In: Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, eds. Oxford Library of Psychology. The Oxford Handbook of Acculturation and Health. Oxford University Press; 2017:75-95. [Google Scholar]

- 66. Jaiswal J, Halkitis PN. Towards a more inclusive and dynamic understanding of medical mistrust informed by science. Behav Med. 2019;45(2):79-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Smith M. Nagweyaab Geebawug: a retrospective autoethnography of the lived experience of kidney donation. CANNT J. 2015;25(4):13-18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Mollins C. The Impact of Urban Relocation on Native Kidney Transplant Patients and Their Families: A Retrospective Study. Winnipeg, MB, Canada: Department of Anthropology, University of Manitoba; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 69. Schulz N. The Meaning of Caring for a Child Who has Renal Failure: A Phenomenological Study of Urban Aboriginal Caregivers: Faculty of Graduate Studies. Winnipeg, MB: Canada: University of Manitoba; 1996. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-cjk-10.1177_2054358121996834 for Barriers to Accessing Kidney Transplantation Among Populations Marginalized by Race and Ethnicity in Canada: A Scoping Review Part 2—East Asian, South Asian, and African, Caribbean, and Black Canadians by Noor El-Dassouki, Dorothy Wong, Deanna M. Toews, Jagbir Gill, Beth Edwards, Ani Orchanian-Cheff, Paula Neves, Lydia-Joi Marshall and Istvan Mucsi in Canadian Journal of Kidney Health and Disease