Abstract

Cancer progression is known to be accompanied by changes in tissue stiffness. Previous studies have primarily employed immortalized cell lines and 2D hydrogel substrates, which do not recapitulate the 3D tumor niche. How matrix stiffness affects patient-derived cancer cell fate in 3D remains unclear. In this study, we report a matrix metalloproteinase-degradable poly(ethylene-glycol)-based hydrogel platform with brain-mimicking biochemical cues and tunable stiffness (40–26,600 Pa) for 3D culture of patient-derived glioblastoma xenograft (PDTX GBM) cells. Our results demonstrate that decreasing hydrogel stiffness enhanced PDTX GBM cell proliferation, and hydrogels with stiffness 240 Pa and below supported robust PDTX GBM cell spreading in 3D. PDTX GBM cells encapsulated in hydrogels demonstrated higher drug resistance than 2D control, and increasing hydrogel stiffness further enhanced drug resistance. Such 3D hydrogel platforms may provide a valuable tool for mechanistic studies of the role of niche cues in modulating cancer progression for different cancer types.

Impact statement

Cancer progression has been demonstrated to be accompanied by changes in tissue stiffness; however, how matrix stiffness affects patient-derived glioblastoma xenograft glioblastoma (PDTX GBM) cells in 3D remains elusive. By employing a biomimetic hydrogel platform with brain-mimicking biochemical cues and tunable stiffness (40–26,600 Pa), we demonstrated the effect of varying hydrogel stiffness on PDTX GBM cell proliferation, spreading, and drug resistance in 3D, which cannot be recapitulated using 2D culture. Such 3D hydrogel platforms may provide a valuable tool for mechanistic studies or drug discovery and screening using patient-derived GBM cells.

Keywords: in vitro cancer models, patient-derived cells, glioblastoma, stiffness, hydrogels

Introduction

Matrix stiffness plays an important role in modulating various cellular processes, such as cell proliferation, migration, and differentiation.1–5 Tissue stiffness is modulated by the composition and organization of cells and extracellular matrix (ECM), resulting in stiffness ranging from pascals to megapascals.1 Matrix stiffness cues are processed by cells through cell surface receptors, which signal through intracellular protein complexes and influence downstream signaling.1 When cultured on 2D polyacrylamide hydrogel substrates, endothelial cell proliferation was regulated by substrate stiffness.2 Furthermore, substrate stiffness has been shown to modulate fibroblast directional migration, in a process known as durotaxis.3 When cultured on polyacrylamide substrates with tunable stiffness, fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and neutrophils displayed significant changes in cell morphology and adhesion, and cytoskeletal organization in response to changes in substrate stiffness.4 Moreover, substrate stiffness can directly influence stem cell differentiation, with tissue-mimicking stiffness promoting lineage-specific differentiation.5

Cancer progression is known to induce significant changes in matrix stiffness. In glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) tumors, tissue stiffness is often altered due to changes in cell and ECM composition, density, and organization. Normal brain tissue stiffness has been found to range from 100 to 1000 Pa, and in the tumor niche, increased secretion and remodeling of fibrous ECM proteins, such as laminin, collagen, or fibronectin, can lead to stiffening of the tissue (up to 26 kPa).5–7 However, leaky vasculature found in GBM can contribute to peritumoral edema, which reduces tissue stiffness to that of 45% of normal brain tissue.8 Previous literature has shown that matrix stiffness can influence GBM tumor cell invasion and proliferation in 2D culture.9,10 When GBM cells were plated on 2D fibronectin-coated polyacrylamide substrates, increasing substrate stiffness from 0.08 kPa to 119 kPa led to faster GBM cell migration and proliferation.9 In another study using similar stiffness range (0.8–119 kPa), substrate stiffness regulated GBM tumor cell cycle progression and proliferation through EGFR-dependent signaling.10

While previous studies using 2D culture have provided valuable insights on the intracellular signaling related to tumor progression, 2D culture does not recapitulate the three-dimensionality of the tumor extracellular niche, whereas tumor invasion only occurs in a 3D matrix. To transition tumor culture from 2D to 3D, recent efforts have employed biomimetic materials such as hydrogels for encapsulating tumor cells in 3D.11–14 Compared to 2D culture, such 3D tumor models facilitate tumor growth and invasion, and they provide a valuable tool that better recapitulates aspects of the in vivo tumor microenvironment and enables in vitro mechanistic studies and drug screening. To synthesize hydrogels as 3D niche for GBM cells, most previous studies have utilized naturally derived materials, such as Matrigel,12 collagen,13,14 and hyaluronic acid,11 given their in vivo-mimicking cues. However, naturally derived materials offer limited tunability of biochemical and mechanical cues, and are subject to batch-to-batch variability.15–18 Changing the concentration of the naturally derived material to alter the stiffness will simultaneously induce undesirable change in the biochemical ligand concentration, making it very challenging to perform mechanistic studies of cancer cell-niche interactions. To overcome these limitations, recent efforts from our group and others have employed synthetic materials, such as poly(ethylene-glycol) (PEG), as synthetic 3D tumor niche.19–22 Synthetic materials are bioinert and provide a blank canvas for biological epitope incorporation, allowing enhanced biomimicry and tunability.19

When engineering a biomimetic brain tumor niche using hydrogels, it is important to consider also the choice of tumor cell sources, in addition to the types of materials. Previous work primarily utilized immortalized GBM cell lines, given their availability and ease of expansion.11,13,14 However, recent studies have shown that immortalized tumor cell lines exhibit distinct phenotypes and genotypes when compared to the primary patient-derived tumor cells, likely due to the immortalization process and decades of in vitro expansion in tissue culture plastic dishes.23–25 Specifically, previous literature analyzing genome-wide chromosomal alterations and gene expression analyses of common glioma cell lines and primary human glioma cells demonstrated distinct genomic alterations and gene expression clusters between the cell lines and primary cells.24 When implanted in vivo, cell line-derived xenografts often do not display key characteristics of primary GBM tumors, including single-cell infiltration throughout brain tissue and necroses and microvascular abnormalities.26,27 In contrast to immortalized tumor cell lines, patient-derived tumor xenograft (PDTX) offers an alternative cell source that can better retain the phenotypes and genotypes of the original parental tumor.28 PDTX cells are derived from the patient's primary tumor specimen, followed by implantation into immunodeficient mouse, which allows for better retention of tumor phenotype and genotype. Previous literature has demonstrated that PDTX cells implanted in vivo can recapitulate histopathological and genomic properties of the parental GBMs, and PDTX tumors showed similar treatment response as parental GBMs to different therapies, including irradiation, chemotherapy, and irradiated therapy.28 When cultured on 2D Matrigel-coated substrates, PDTX cells displayed differential response to substrate stiffness in terms of cell shape, motility, and invasion.12 However, how matrix stiffness influences PDTX GBM cell fates in 3D remains largely unknown. Furthermore, most previous 3D GBM models using hydrogels utilized immortalized cell lines, which may not be optimal for PDTX GBM cells.9–11,13,14,19,20,29

The goal of this study is to examine how matrix stiffness modulates PDTX GBM cell proliferation and invasion in 3D, and evaluate the effects of 3D culture on PDTX GBM cell drug response using temozolomide (TMZ), a drug that is commonly administered to GBM patients.30 We hypothesize that varying hydrogel stiffness will lead to differential tumor proliferation and invasion in 3D.To test our hypothesis, we developed a biomimetic hydrogel platform with tunable stiffness as 3D niche to study the effects of matrix stiffness on PDTX GBM cell fates in 3D. Our research group has recently reported a matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-degradable PEG-based hydrogel platform that supported the proliferation and invasion of an immortalized GBM cell line.19 In this study, hydrogel stiffness was modulated by tuning the concentration of PEG (w/v %) to achieve stiffness relevant to GBM tumor progression (40–26,600 Pa) to mimic edematous, normal brain, and GBM stiffened tissue.5,6,8 PDTX cell fates in response to hydrogel stiffness were analyzed by monitoring cell proliferation and morphology. Furthermore, PDTX cell response to chemotherapeutic drug was analyzed in 2D culture and 3D hydrogels with varying stiffnesses.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Eight-arm PEG (MW ∼40 kDa) was purchased from JenKem Technology, USA (Allen, TX). Linear PEG (MW ∼1.5 kDa) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, USA (St. Louis, MO). RGD peptide (CRGDS) and MMP-cleavable peptide (KCGPQGIWGQCK) were purchased from Bio Basic, Inc., (Amherst, NY). Sodium hyaluronate (HA) (MW ∼20–40 kDa) was purchased from Lifecore Biomedical (Chaska, MN). All other reagents were obtained from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA), unless otherwise noted.

Hydrogel fabrication

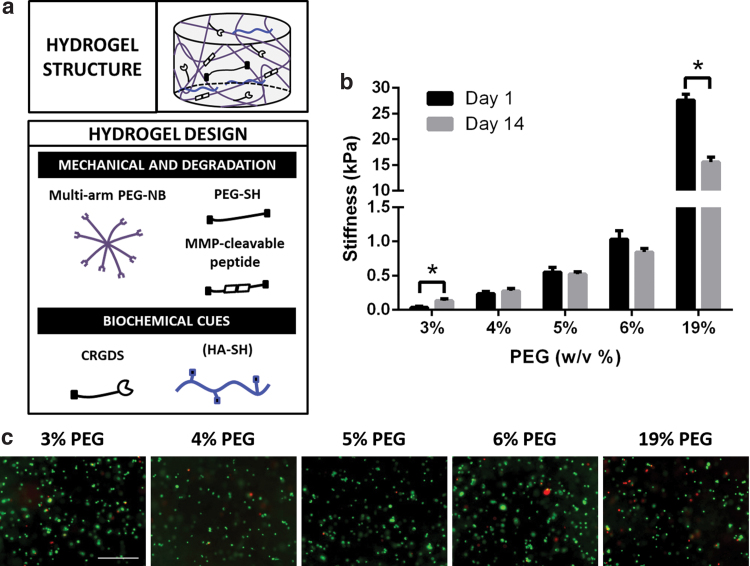

Hydrogels were fabricated using components as shown (Fig. 1a). Eight-arm PEG-norbornene (PEG-NB), linear PEG-dithiol (PEG-SH), and thiolated hyaluronic acid (HA-SH) were synthesized as previously reported.31–33 Out of eight arms on PEG-NB, six arms were used for hydrogel crosslinking, and two arms were used for conjugation of biochemical cues. For hydrogel fabrication, 8-arm PEG-NB (40 kDa) was crosslinked with nondegradable linear PEG-SH (1.5 kDa) and an MMP-cleavable peptide (KCGPQGIWGQCK) at a 2:3:3 ratio. Hydrogel stiffness was modulated by tuning the 8-arm PEG-NB concentration (w/v %) (3%, 4%, 5%, 6%, and 19%). To allow for cell adhesion, RGD peptide (CRGDS) was added at a final concentration of 0.914 mM. To mimic the ECM content of brain tissue, HA-SH was chemically incorporated at a final concentration of 0.004% (w/v), which was selected based on reported values in human brain tissue.34 In 3–6% PEG groups, noncrosslinkable 20 kDa linear PEG was added into the precursor solution as space filler during the hydrogel formation process to further decrease the crosslinking efficiency of multiarm PEG. This strategy is critical for the ability to form hydrogels softer than 1 kPa. Once the hydrogel is crosslinked and placed into media, the 20 kDa linear PEG diffuses out of the hydrogel matrix. We expect the decreased crosslinking density will reduce the physical restriction on the cells. To induce gelation, hydrogels were crosslinked in the presence of photoinitiator Igracure D2959 (0.05% w/v; Ciba Specialty Chemicals, Tarrytown, NY) under UV light (365 nm, 4 mW/cm2) for 5 min at RT.

FIG. 1.

Hydrogels with brain-mimicking biochemical cues and tunable stiffness for encapsulating PDTX GBM cells. (a) Schematic of hydrogel platform structure and design. Hydrogel mechanical and degradation properties were modulated by multiarm PEG-norbonene (8-arm PEG-NB), linear PEG-dithiol (PEG-SH) crosslinker, and MMP-cleavable crosslinker. To permit cell adhesion, CRGDS peptide was chemically incorporated. Thiolated hyaluronic acid (HA-SH) was chemically conjugated to mimic brain extracellular matrix content. Hydrogel crosslinking was achieved through thiol-ene UV photopolymerization. (b) Hydrogels with tunable stiffnesses were fabricated as 3D niche for PDTX GBM cells by varying PEG concentration (w/v %). Stiffness of hydrogels was measured on day 1 and day 14. *p < 0.05 (compared to hydrogel of same PEG concentration on day 1). Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3/group). (c) PDTX GBM cells showed high cell viability in all groups following encapsulation. Live = green. Dead = red. Scale bar = 500 μm. PDTX GBM, patient-derived glioblastoma xenograft; PEG, poly(ethylene-glycol); MMP, matrix metalloproteinase. Color images are available online.

Cell encapsulation in 3D hydrogels

Patient-derived human glioblastoma xenograft (PDTX GBM) cells (D-270 MG, EGFR amplification) were provided by the laboratory of Prof. Gerald Grant at Stanford University Medical Center. D-270 MG cells were obtained under an IRB-approved protocol and were derived as previously reported.35,36 D-270 MG cells were obtained and characterized as we recently reported.37 PDTX GBM cells were expanded in improved minimal essential zinc option medium (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco, Life Technologies) and 0.1% gentamicin (Life Technologies) at 37°C in 5% CO2. For encapsulation in hydrogels, trypsinized PDTX GBM cells were resuspended in hydrogel precursor solution at a final concentration of 0.5 M cells/mL. Seventy-five microliters of cell-containing hydrogel solution was pipetted into a cylindrical-shaped mold (3 mm in height and 5 mm in diameter) and UV crosslinked as described above. We used optimized UV crosslinking parameters to achieve 3D cell encapsulation in hydrogels with high cell viability (Fig. 1b). We have demonstrated previously such UV crosslinking supports high GBM cell viability in PEG-based hydrogels.19,20,37 Other laboratories have also utilized UV crosslinking for GBM cell encapsulation in 3D without adverse effects.14,38 In addition, we have also shown our optimized UV crosslinking protocol supports encapsulation of multiple cell types in 3D, including mesenchymal stem cells,39 smooth muscle cells,40 adipose-derived stem cells, and chondrocytes.41 Samples were cultured in growth media as described above for 14 days at 37°C in 5% CO2 with medium change every other day. Experiment was performed twice (n = 21 for 3% PEG, n = 11 for 4%, 5%, 6%, and 19% PEG).

Hydrogel mechanical testing

Acellular hydrogels (n = 3) prepared as above were allowed to equilibrate overnight for measuring the initial hydrogel stiffness on day 1. Cell-laden hydrogels (n = 3) were cultured for 14 days to measure final hydrogel stiffness. To measure the stiffness of hydrogels, unconfined compressive tests were conducted using an Instron 5944 materials testing system (Instron Corporation, Norwood, MA). The test setup consisted of custom-made aluminum compression plates lined with polytetrafluoroethylene to minimize friction. All tests were conducted in PBS solution at RT. Before each test, a preload of ∼2 mN was applied. The upper plate was then lowered at a rate of 1% strain/sec to a maximum strain of 30%. Load and displacement data were recorded at 100 Hz. The modulus was determined for strain ranges of 10–20% from linear curve fits of the stress vs. strain curve in each strain range.

Cell viability

Initial PDTX GBM cell viability (n = 1) was assessed 2 h after hydrogel encapsulation using Live/Dead Cell Viability Assay kit (Life Technologies). Live/Dead reagent was prepared as per manufacturer's instructions. Hydrogels were immersed in Live/Dead reagent solution for 40 min and imaged using a Zeiss fluorescence microscope (Zeiss, Jena, Germany).

Cell proliferation

PDTX GBM cell proliferation was measured by quantifying the DNA content in hydrogels on days 1 and 14 (n = 3) using Quant-iT PicoGreen assay (Life Technologies). Briefly, lyophilized hydrogel samples were rehydrated and digested using papain (Worthington Biochemical Corp, Lakewood, NJ) at 60°C for 16 h. Samples were then vortexed and centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 5 min at RT. The supernatant was used to measure DNA content as per manufacturer's instructions.

Immunostaining

PDTX GBM cell morphology was assessed using F-actin confocal staining of PDTX cells on day 14 (n = 1). Briefly, hydrogels were fixed in 4% PFA for 1 h at RT and washed in PBS. Cell permeabilization was performed using 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS. Samples were blocked in 1% BSA, and 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS overnight at 37°C. F-actin and nuclei were stained using phalloidin-rhodamine (0.5 μg/mL, Sigma) and Hoechst 33342 dye (6.67 μg/mL; Cell Signaling Technologies, Danvers, MA), respectively, for 1 h at 37°C. Samples were washed with PBS and incubated in mounting media (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) overnight at 4°C. Hydrogels were imaged using Leica SP5 upright laser scanning confocal microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany). Maximal projections were obtained from 200 μm thick Z-stack with 2 μm step size.

RT-polymerase chain reaction

Gene expression levels of mechanotransduction proteins (RhoA, ROCK1), HIF1α, VEGFa, and MMP2 were measured on days 1 and 7. Total RNA was isolated from hydrogels (n = 3) using TRIzol (Life Technologies). cDNA was synthesized using SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis kit (Life Technologies). RT-PCR was then performed using an Applied Biosystems 7900 Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Life Technologies) using Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Life Technologies). Relative expression levels of target genes were determined using the comparative CT method. Target gene expression was first normalized to a housekeeping gene, GAPDH, followed by a second normalization to the gene expression level of PDTX cells on day 1.

TMZ treatment

Before TMZ treatment, PDTX GBM cells were cultured in 3D hydrogels with varying stiffnesses (40, 1000, and 26,600 Pa) for 10 days (n = 3). For 2D culture, cells were seeded in 96-well plates (1000 cells/well) and cultured for 24 h (n = 3). TMZ (Sigma) was added at the following concentrations: 0, 3, 10, 30, 100, and 300 μM. Cell viability was measured after 3 days using tetrazolium-based absorbance assay as per manufacturer's instructions (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) (Promega, Madison, WI).

Statistical analyses

GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA) was used to perform statistical analyses on hydrogel stiffness, cell proliferation, gene expression, and TMZ response data. Unpaired Student's t tests (assuming Gaussian distribution) and one-way and two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) were used to determine statistical significance (p < 0.05). Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) with three biological replicates per group, unless otherwise noted. Sample sizes were selected based on established protocols in the laboratory and published work.19

Results

Fabricating PEG Hydrogels with tunable stiffness

To mimic tissue stiffnesses relevant for GBM tumor progression, hydrogels were synthesized with varying PEG concentrations (w/v %). The initial hydrogel stiffnesses were as follows: 3% PEG (40 ± 15 Pa), 4% PEG (240 ± 30 Pa), 5% PEG (550 ± 70 Pa), 6% PEG (1000 ± 120 Pa), and 19% PEG (26,600 ± 1100 Pa) (Fig. 1b). These initial stiffnesses cover the range previously reported for edematous, normal brain, and GBM tissue stiffnesses.5,6,8 The stiffnesses of cell-laden hydrogels were also measured after 14 days in culture. Hydrogel stiffnesses on day 14 were as follows: 3% PEG (130 ± 30 Pa), 4% PEG (280 ± 30 Pa), 5% PEG (520 ± 30 Pa), 6% PEG (840 ± 55 Pa), and 19% PEG (15,500 ± 930 Pa) (Fig. 1b).

Increasing PEG hydrogel stiffness inhibits PDTX GBM proliferation in 3D

A key hallmark of tumors is abnormal and excessive rates of cell proliferation. The effects of matrix stiffness on tumor cell proliferation were evaluated using bright-field microscopy and changes in DNA content over 14 days. On day 1, no differences in cell viability were observed across all groups (Fig. 1c). PDTX GBM proliferation was monitored using bright-field microscopy imaging over time (Fig. 2a) and quantification of cell DNA content (Fig. 3a). In 26,600 Pa hydrogels, minimal cell proliferation was observed. In contrast, in 1000 Pa hydrogels or softer, significant cell proliferation up to 21-fold was observed over 14 days, and formation of multicellular aggregates was observed throughout the hydrogels. Decreasing hydrogel stiffness from 1000 Pa to 40 Pa further increased cell proliferation (Fig. 3a). In contrast, 26,600 Pa gels led to a 70% decrease in DNA content on day 14 compared to day 1 (Fig. 3a).

FIG. 2.

Decreasing hydrogel stiffness enhanced PDTX GBM cell proliferation and spreading in 3D, as observed using bright-field microscopy. (a) PDTX GBM cell growth in hydrogels with varying stiffness on days 1, 7, and 14. Scale bar = 500 μm. (b) PDTX GBM cell morphology in hydrogels with varying stiffness on days 1, 7, and 14. Scale bar = 50 μm.

FIG. 3.

Decreasing hydrogel stiffness led to significant increase in the fold of PDTX GBM cell proliferation after 14 days in culture; increasing hydrogel stiffness to 26,600 Pa significantly upregulated gene expression of key markers. (a) Fold of cell proliferation on day 14 over day 1, as calculated from cell DNA content in hydrogels on days 1 and 14. *p < 0.05. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3 samples/group). (b–f) Gene expression of PDTX cells in hydrogels on day 7 (n = 3) for mechanotransduction proteins RhoA (b) and ROCK1 (c), HIF1α (d), VEGFa (e), and MMP2 (f) (Normalized to day 1). *p < 0.05.

Effect of hydrogel stiffness on mechanosensing, matrix remodeling, and hypoxia is threshold dependent

We next quantified gene expression levels of mechanotransduction proteins (RhoA and ROCK1) (Fig. 3b, c). Increasing stiffness from 40 Pa to 1000 Pa did not significantly impact gene expressions of these mechanosensing markers. Only when hydrogel stiffness increase to 26,000 Pa did we observe a significant upregulation of RhoA and ROCK1. We observed similar trend in gene expression of HIF1α, which mediates hypoxic response and is involved in apoptotic signaling pathways (Fig. 3d). Expressions of genes related to angiogenesis (VEGFa) and matrix remodeling (MMP2) were also found to be significantly upregulated only in 26,600 Pa hydrogels (Fig. 3e, f).

Increasing PEG hydrogel stiffness inhibits PDTX GBM spreading in 3D

To facilitate GBM cell spreading and invasion in 3D, we incorporated MMP-degradable peptide in PEG hydrogel as we reported previously.19,20 We observed greatest cell spreading in 40 Pa hydrogel with edema-mimicking stiffness, and further increase in hydrogel stiffness led to reduced PDTX GBM cell spreading in 3D (Fig. 2b). On day 1, as expected, cells in all groups were rounded right after encapsulation. In 40 Pa hydrogels, cell spreading was markedly faster and cells displayed a bipolar, elongated morphology by day 7. By day 14, cells in 40 Pa hydrogels continued to spread, forming an extensive interconnected cell network. In 240 Pa hydrogels, cells remained as isolated aggregates with some protrusions at the surface. In 550 and 1000 Pa hydrogels, cell aggregates were mostly spherical with few cell protrusions. In 26,600 Pa hydrogels, no cell spreading was observed by day 14. F-actin cytoskeletal staining performed on day 14 confirmed the bright-field observations (Fig. 4). Cells in 40 Pa hydrogels displayed elongated cell extensions with high interconnectivity between cell aggregates. In 240 Pa hydrogels, cell protrusions were shorter with less interconnectivity. In 550 and 1000 Pa hydrogels, minimal cell spreading was observed with little interconnectivity between aggregates. In 26,600 Pa hydrogels, no actin protrusion was observed.

FIG. 4.

Decreasing hydrogel stiffness enhanced PDTX GBM cell spreading and formation of interconnected cell network in 3D hydrogels. Confocal Z-stack projection of F-actin cytoskeletal staining on day 14. Scale bar = 100 μm. Red = F-actin. Blue = nuclei. Z-stack projection generated from 200 μm stack with 2 μm step size. Color images are available online.

PDTX GBM cells exhibit higher drug resistance in 3D than 2D, and increasing hydrogel stiffness led to higher drug resistance

We next assess the effect of 2D versus 3D culture and varying hydrogel stiffness on drug response of PDTX cells. TMZ was selected as a model drug as it is a commonly used chemotherapeutic for treating GBM patients.30 Before drug treatment, PDTX GBM cells were cultured either in 2D culture or in 3D hydrogels with varying stiffness. Given the peak plasma concentration for TMZ reported in literature is 200 μM,42 we chose to expose PDTX GBM cells to TMZ of varying concentrations ranging from 0 to 300 μM. PDTX cells exhibit significantly higher drug resistance in 3D than 2D, and increasing hydrogel stiffness led to higher drug resistance (Fig. 5). When the TMZ drug concentration was 30 μM, 26,600 Pa hydrogels showed 93% cell viability, whereas 58% cell viability was observed in 40 Pa hydrogels. In 2D, the cell viability was 29% at 30 μM.

FIG. 5.

PDTX GBM cells cultured in 3D hydrogels exhibited higher chemotherapeutic drug resistance compared to 2D control; increasing hydrogel stiffness further enhanced drug resistance in 3D. TMZ drug resistance, as measured by fraction of viable cells normalized to no drug control (0 μM), for tumor cells were cultured in either 3D hydrogels with varying stiffness or in 2D dish. *p < 0.05. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3 samples/group). TMZ, temozolomide.

Discussion

Our previous article established the use of MMP-degradable PEG hydrogels as 3D in vitro models for studying GBM.19 However, only two stiffness were studied (1 and 26 kPa), and an immortalized GBM cell line (U87) was used to show the proof of the principle. Compared to this previous work,19 this article has made several key advances that further improve the physiological relevance of the model. First, previous hydrogel platforms11,13,14,19,20 primarily used immortalized tumor cell lines as model cell types, which poorly represent primary cell genomic and gene expression profiles and fail to fully recapitulate in vivo GBM tumor characteristics.24–27 In this study, we focus on patient-derived GBM xenograft cells, which possess more physiologically relevant phenotype compared to immortalized cell lines. Such GBM models would provide a more physiologically relevant and tunable platform for mechanistic studies and drug screening. Second, given peritumoral edema often leads to softer matrix and correlates with poor patient outcomes,8,43 we specifically added lower range of hydrogel stiffness (40, 240, and 550 Pa), which has not been studied in the previous article. Our results demonstrate that decreasing hydrogel stiffness enhanced PDTX GBM proliferation, and hydrogels with stiffnesses 240 Pa and below supported robust cell spreading and invasion in 3D. Soft hydrogels with stiffness mimicking peritumoral edema (40 Pa) facilitated the most robust tumor cell proliferation and invasion in 3D. Third, we assessed the effect of varying hydrogel stiffness on GBM drug resistance in 3D, which has not been studied before. Using TMZ as a model drug, PDTX GBM cells cultured in 3D had higher drug resistance compared to 2D culture, and increasing hydrogel stiffness led to increased drug resistance.

One key hallmark of GBM tumors is abnormal, excessive cell proliferation. How matrix stiffness modulates tumor cell proliferation in physiologically relevant manner remains poorly understood. Previous literature using 2D hydrogel substrates and 3D naturally derived material-based hydrogels found that increasing hydrogel stiffness led to increased cell proliferation.9,12,14 In contrast, our results indicate that in PEG-based hydrogels, decreasing hydrogel stiffness significantly enhanced tumor cell proliferation (Fig. 3a). In 2D culture, the lack of a 3D matrix can alter cell surface receptor organization, which can lead to differential downstream signaling events than those found in 3D.44 In 3D naturally derived material-based hydrogels, increasing hydrogel stiffness by changing ECM protein concentration will simultaneously alter the ligand density, which may influence receptor-mediated intracellular signaling.45 Similar to our observations, a previous study using PEG-based, MMP-degradable hydrogels as 3D niche for encapsulating epithelial cancer cells showed higher tumor cell proliferation in softer hydrogels.21 In our system, increasing hydrogel stiffness was achieved by increasing PEG concentration. Stiff hydrogels are characterized by higher crosslinking density, imposing greater physical restriction on tumor cells, thereby hindering cell proliferation and migration. In this study, PDTX GBM cell proliferation increased in a dose-dependent manner as hydrogel stiffness decreased from 1000 Pa to 40 Pa (Fig. 3a). Interestingly, in 26,600 Pa hydrogels, a reduction in DNA content was observed after 14 days, suggesting cell apoptosis (Fig. 3a). Although crosslinking density is higher in 26,600 Pa hydrogels, nutrient diffusion is not a limiting factor. Using the equilibrium swell ratio and the Flory-Rehner calculation, the theoretical mesh size of 26,600 Pa hydrogels was calculated to be ∼13 nm (data not shown), which is much larger than the hydrodynamic radius of most growth factors, such as fibroblast growth factor (∼4 nm).46 As such, nutrient diffusion is not responsible for the observed cell apoptosis in stiffer hydrogels. Increased matrix stiffness and physical restriction to 26,600 Pa may have induced cell apoptosis by upregulating HIF1α expression (Fig. 3d),47 which can lead to downstream activation of apoptotic pathways.48

HIF1α is also known to target VEGFa, a prominent proangiogenic factor, in response to environmental stresses such as hypoxia.49 While our platform does not model hypoxia, GBM cells are known to secrete VEGFa to modulate and enable endothelial cell recruitment and proliferation, resulting in vessel sprouting and angiogenesis for nutrient and oxygen supply in the tumor microenvironment.50 Given the reduced cell proliferation (Fig. 3a) and possible necrosis in the increased matrix stiffness of the 26,600 Pa hydrogels, this regional stress may have established potential hypoxic areas resulting in upregulation of HIF1α and thus VEGFa (Fig. 3d, e). HIF1α also targets MMPs,49 which may, in part, explain the consequent upregulation of MMP2 expression observed in the 26,600 Pa hydrogels (Fig. 3f). However, glioma cells also secrete MMPs such as MMP1, MMP2, and MMP9 to overcome barriers through proteolytic degradation to proliferate and invade within the tight extracellular space.51 Given the increased matrix restriction imposed on the cells in the 26,600 Pa hydrogels, GBM cells may have also upregulated MMP2 expression to overcome these barriers independent of HIF1α control, but were unsuccessful as evidenced by reduced cell proliferation (Fig. 3a) and poor cell spreading (Fig. 2b and 4). Overall, it is interesting that the drastic stiffness increase to 26,600 Pa, which mimics stiffened GBM tissue, led to a stark reduction of cell proliferation (Fig. 3a), but correlated with significant upregulation of HIF1α, VEGFa, and MMP2 expression (Fig. 3d–f).

Another key hallmark of GBM tumor cells is their extreme invasiveness, which precludes complete surgical resection and contributes to eventual tumor recurrence. Previous literature using 2D substrates and 3D naturally derived material-based hydrogels found that increasing stiffness enhanced tumor cell spreading and migration.9,52 In contrast, in this study, increasing hydrogel stiffness led to decreased tumor cell spreading in 3D, likely due to the increased crosslinking density and physical restrictions in stiffer matrices. When hydrogel stiffness was 550 Pa or greater, cell spreading was significantly reduced, suggesting that there is a threshold stiffness above which tumor cell spreading and migration are impeded. This phenomenon has also been observed for fibrosarcoma cells cultured in PEG hydrogels.53 Strikingly, PDTX GBM cells in 40 Pa hydrogels formed an interconnected cell network, which was largely absent in stiffer matrices (Fig. 4). The highly elongated actin-rich cell extensions that bridged neighboring cell clusters resemble tumor microtubes (TM) formed by patient-derived GBM cells in the mouse brain.54 TMs are ultra-long actin-rich membrane protrusions that can exceed 500 μm in length and are found in 93% of patient GBM samples.54 GBM cells utilize TMs as routes for proliferation, invasion, and cell-cell communication, which can promote radiotherapy resistance.54

In addition, tumor development is also characterized by changes in tissue stiffness due to extensive matrix remodeling processes that occur in the tumor niche.51 For glioblastoma, these processes include degradation of ECM proteins by enzymes, overproduction of ECM proteins, or secretion of novel ECM proteins by tumor or other stromal cell types.55,56 In this study, GBM cell-mediated matrix remodeling may have contributed to significant hydrogel stiffening of 40 Pa hydrogels after 14 days of culture (Fig. 1b). In 40 Pa hydrogels, degradation of hydrogel MMP crosslinks may have created additional space for deposition of ECM proteins, as well as for accelerated cell proliferation and invasion and formation of interconnected cell aggregates (Figs. 2–4). Compared to normal cells, glioma cells exhibit increased expression of proteases that can open spaces for cell invasion and release ECM protein fragments that act as mitogenic or motogenic factors.56,57 Moreover, glioma cells can also remodel their surrounding matrix by overproduction of brain ECM proteins, such as hyaluronic acid, or deposition of ECM proteins atypical for brain tissue, such as collagen or fibronectin.56,58 In contrast to the stiffening of 40 Pa hydrogels, the significant reduction of stiffness in 26,600 Pa hydrogels may be a result of extensive cell-mediated degradation of MMP-degradable crosslinks (Fig. 1b). Specifically, this may be attributed to MMP2 expression, which was upregulated in 26,600 Pa hydrogels (Fig. 3f), as well as other MMPs secreted, but not measured in this study. However, given the high crosslinking density, the degree of hydrogel degradation after 14 days in culture was insufficient to support extensive GBM cell proliferation or spreading in 26,600 Pa hydrogels (Figs. 3a and 4).

While varying hydrogel stiffness from 40 Pa to 1000 Pa led to a significant decrease in GBM spreading and proliferation (Figs. 2, 3a, and 4), we observed no significant changes in gene expression of mechanotransduction genes (RhoA and ROCK1) (Fig. 3b, c). Based on these results, we speculate the changes in GBM cell spreading and proliferation across this stiffness range is not due to mechanosensing, but likely due to increased physical restriction imposed on the cells as stiffness of PEG hydrogels increase. Interestingly, when hydrogel stiffness further increases to 26,600 Pa, we observed a significant upregulation of mechanosensing genes RhoA and ROCK1. This suggests upregulation of mechanosensing gene in GBM in 3D only occurs when the stiffness is above the threshold of 1000 Pa. When stiffness of PEG hydrogels increases to 26,000 Pa, the crosslinking density is the highest, posing more physical constraints on the encapsulated GBM cells. Indeed, we observed a significant upregulation of matrix remodeling gene MMP2 in this group (Fig. 3f).

Chemotherapeutic drug resistance is a key challenge when treating tumors, and how matrix stiffness affects GBM cell drug resistance remains largely unexplored. Using TMZ as model drug, our results demonstrate that matrix stiffness-induced changes in tumor cell proliferation may modulate chemotherapeutic drug resistance. TMZ is an oral prodrug that methylates DNA, which causes DNA base pair mismatch and triggers downstream apoptotic pathways. This mechanism of action depends on active cell cycle progression and extensive cell proliferation.59,60 To analyze the effects of matrix stiffness on TMZ response, 40, 1000, and 26,600 Pa hydrogels were selected to capture a wide range of cell proliferation behaviors. In the absence of TMZ, tumor cells in 40 and 1000 Pa hydrogels proliferated rapidly (21- and 13-fold, respectively) after 14 days in culture, while cells in 26,600 Pa hydrogels did not proliferate (Figs. 2a and 3). As expected, due to high proliferation rates, cells in 40 Pa hydrogels were the most responsive to TMZ. Moderate proliferation rates in 1000 Pa hydrogels resulted in increased drug resistance. The lack of cell proliferation in 26,600 Pa hydrogels led to minimal change in cell viability across the range of TMZ concentrations tested (0–300 μM) (Fig. 5). Changes in TMZ response across hydrogel groups cannot be attributed to hydrogel pore size effects on TMZ diffusivity, as the pore sizes of these hydrogels (13 nm and greater) are significantly larger than the size of TMZ, which is a small molecular drug with a molecular weight of 194 Da.61 As TMZ's mechanism of action relies on cell proliferation, our results suggest that matrix stiffness can influence tumor cell response to TMZ due to stiffness-induced changes in cell proliferation rates.

When evaluating drugs for clinical use, higher drug resistance is often observed in in vivo models compared to 2D culture. Previous reports have demonstrated that cells cultured in 3D have increased drug resistance, suggesting that 3D models may better recapitulate in vivo cell response.62 In agreement with previous reports, PDTX GBM cells cultured in 3D hydrogels (40 Pa) demonstrated higher drug resistance compared to 2D culture when TMZ drug concentration was 10 μM or higher (Fig. 5). Increased drug resistance in 3D than in 2D may be due to a number of factors, including differences in cell proliferation rates, gene expression, and mass transport. In terms of proliferation, cell proliferation rates in 3D are hindered compared to 2D due to the physical restriction of ECM and time required for degradation and remodeling. As such, decreased tumor cell proliferation in 3D may contribute to higher drug resistance.60 In addition, 3D culture may directly upregulate drug resistance-related genes, such as prolyl 4-hydroxylase beta polypeptide (P4HB), as suggested by previous literature.63 Finally, 3D and 2D culture conditions have different mass transport properties, affecting drug accessibility to the cells. In 2D, cells are equally exposed to the surrounding media, permitting more efficient drug transport. In contrast, in vivo tumors reside in a dense ECM that presents barriers to drug transport, which is better recapitulated under 3D culture conditions.

The findings from this study could be translationally helpful to future GBM research by providing a more physiologically relevant 3D in vitro GBM model for drug discovery or facilitating personalized treatment using patient-specific cells. Based on our findings, we identified 40 Pa PEG hydrogels as the leading formulation for supporting robust PDTX GBM proliferation and invasion in 3D. We further demonstrated PDTX cells exhibit significantly higher drug resistance in 3D than 2D culture using TMZ as a model drug (Fig. 5). As such, we envision this 3D GBM model could offer a much more physiologically relevant model for drug testing to better predict drug responses in patients. Finally, given different patients likely would respond differently to various drug regimen, this model could also be particularly useful for personalized therapeutic optimization by encapsulating patient-specific cells in the optimal hydrogel formulation.

The stiffness of the tumor niche can be impacted by deposition and remodeling of ECM, as well as edema. While some reports suggest the stiffness of GBM tumor can increase up to 26 kPa due to increased ECM deposition,5–7 other literature suggest GBM tumor can also lead to significant decrease in stiffness compared to normal brain due to peritumoral edema caused by leaky vasculature.8 As such, our study exploited stiffness ranging from peritumoral edema (i.e., 40 Pa), to normal brain tissue (i.e., 240–1000 Pa), to stiffened tumor tissues (26 kPa). Using our PEG-based hydrogel platform, we found stiffness mimicking peritumoral edema (i.e., 40 Pa) supports highest GBM cell proliferation and invasion. Furthermore, GBM in 3D hydrogels demonstrated higher drug resistance compared to 2D culture. These results are in line with clinical observation that peritumoral edema predicts poor clinical outcome for GBM patients.43 Furthermore, we found PEG hydrogels with higher stiffness led to decreased tumor proliferation and spreading. While 26 kPa is supposed to mimic the stiffness of GBM tissues, it led to the lowest GBM proliferation and spreading. This apparent contradiction may be explained by several factors. First, tumor cells deposit ECM over time, and 26 kPa is the end result of tumor stiffness after aggressive tumor growth, and does not necessarily represent the initial matrix stiffness that promotes tumor growth. Second, tumor spreading requires degradation of the original matrix,20 and it may be more difficult for GBM cells to degrade our MMP-degradable PEG hydrogels than native brain ECM. Future studies can further optimize the degradation properties of our PEG hydrogel by changing degradable peptides and concentration. In addition, brain tissues are viscoelastic,64 whereas our PEG hydrogel is elastic due to the covalent crosslinking mechanism. Using physically crosslinked alginate hydrogels as a model system, recent studies have shown that viscoelasticity allows cells to spread more easily than elastic hydrogels due to the dynamic bond.64,65 Future studies can incorporate viscoelasticity into PEG hydrogel platform, which can further increase the physiological relevance of the model to mimic the native tumor niche.

Conclusion

In summary, in this study, we have developed a PEG-based hydrogel platform with tunable stiffness as 3D niche for PDTX GBM to study the effects of matrix stiffness on brain tumor cell behavior. Tumor cells exhibited stiffness-dependent behavior in proliferation, spreading, and drug response, providing further evidence for the important role of matrix stiffness in GBM progression. We identified a leading formulation (40 Pa) that enabled robust PDTX GBM cell proliferation, invasion, and formation of interconnected cell network in 3D. Such hydrogels provide a valuable 3D culture platform that enables culture of PDTX cells for personalized drug screening and for screening of novel therapeutics using PDTX cells that better retain disease phenotype. Furthermore, the hydrogel platform reported in this study may provide a useful tool for enabling mechanistic studies to elucidate the effects of niche cues on modulating cancer progression for GBM and other cancer types.

Acknowledgments

C.W. would like to thank Stanford Graduate Fellowship and Stanford Interdisciplinary Graduate Fellowship for support. S.S. would like to thank Stanford Bioengineering Department fellowship and NIH Biotechnology training grant fellowship for support. The authors also appreciate technical assistance from Stanford Cell Sciences Imaging Facility for confocal imaging and Anthony Behn for mechanical testing.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

This work was supported by the following grants: NIH R01DE024772 (F.Y.), NIH 1R01AR074502 (F.Y.), the Stanford Child Health Research Institute Faculty Scholar Award (F.Y.), Stanford Bio-X IIP grant award (F. Y.), and the Alliance for Cancer Gene Therapy Young Investigator award grant (F.Y.).

References

- 1. Wells, R.G. The role of matrix stiffness in regulating cell behavior. Hepatology 47, 1394, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yeh, Y.T., Hur, S.S., Chang, J., et al. Matrix stiffness regulates endothelial cell proliferation through septin 9. PLoS One 7, e46889, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lo, C.M., Wang, H.B., Dembo, M., Wang, Y.L., and Wang, Y.L.. Cell movement is guided by the rigidity of the substrate. Biophys J 79, 144, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yeung, T., Georges, P.C., Flanagan, L.A., et al. Effects of substrate stiffness on cell morphology, cytoskeletal structure, and adhesion. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton 60, 24, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Engler, A.J., Sen, S., Sweeney, H.L., and Discher, D.E.. Matrix elasticity directs stem cell lineage specification. Cell 126, 677, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Polacheck, W.J., Zervantonakis, I.K., and Kamm, R.D.. Tumor cell migration in complex microenvironments. Cell Mol Life Sci 70, 1335, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Netti, P.A., Berk, D.A., Swartz, M.A., Grodzinsky, A.J., and Jain, R.K.. Role of extracellular matrix assembly in interstitial transport in solid tumors. Cancer Res 60, 2497, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kuroiwa, T., Ueki, M., Ichiki, H., et al. Time Course of Tissue Elasticity and Fluidity in Vasogenic Brain Edema. In: James H.E., Marshall, L.F., Reulen, H.J., et al. eds. Brain Edema X. Acta Neurochirurgica Supplements. Vienna, Springer-Verlag Wien, 1997, p. 87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ulrich, T.A., de Juan Pardo, E.M., and Kumar, S.. The mechanical rigidity of the extracellular matrix regulates the structure, motility, and proliferation of glioma cells. Cancer Res 69, 4167, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Umesh, V., Rape, A.D., Ulrich, T.A., and Kumar, S.. Microenvironmental stiffness enhances glioma cell proliferation by stimulating epidermal growth factor receptor signaling. PLoS One 9, e101771, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ananthanarayanan, B., Kim, Y., and Kumar, S.. Elucidating the mechanobiology of malignant brain tumors using a brain matrix-mimetic hyaluronic acid hydrogel platform. Biomaterials 32, 7913, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Grundy, T.J., De Leon, E., Griffin, K.R., et al. Differential response of patient-derived primary glioblastoma cells to environmental stiffness. Sci Rep 6, 23353, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kaufman, L.J., Brangwynne, C.P., Kasza, K.E., et al. Glioma expansion in collagen I matrices: analyzing collagen concentration-dependent growth and motility patterns. Biophys J 89, 635, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pedron, S., and Harley, B.A.. Impact of the biophysical features of a 3D gelatin microenvironment on glioblastoma malignancy. J Biomed Mater Res A 101, 3404, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hughes, C.S., Postovit, L.M., and Lajoie, G.A.. Matrigel: a complex protein mixture required for optimal growth of cell culture. Proteomics 10, 1886, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lutolf, M.P., and Hubbell, J.A.. Synthetic biomaterials as instructive extracellular microenvironments for morphogenesis in tissue engineering. Nat Biotechnol 23, 47, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nemir, S., and West, J.L.. Synthetic materials in the study of cell response to substrate rigidity. Ann Biomed Eng 38, 2, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Miroshnikova, Y.A., Jorgens, D.M., Spirio, L., Auer, M., Sarang-Sieminski, A.L., and Weaver, V.M.. Engineering strategies to recapitulate epithelial morphogenesis within synthetic three-dimensional extracellular matrix with tunable mechanical properties. Phys Biol 8, 026013, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wang, C., Tong, X., and Yang, F.. Bioengineered 3D brain tumor model to elucidate the effects of matrix stiffness on glioblastoma cell behavior using PEG-based hydrogels. Mol Pharm 11, 2115, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wang, C., Tong, X., Jiang, X., and Yang, F.. Effect of matrix metalloproteinase-mediated matrix degradation on glioblastoma cell behavior in 3D PEG-based hydrogels. J Biomed Mater Res A 105, 770, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Loessner, D., Stok, K.S., Lutolf, M.P., Hutmacher, D.W., Clements, J.A., and Rizzi, S.C.. Bioengineered 3D platform to explore cell-ECM interactions and drug resistance of epithelial ovarian cancer cells. Biomaterials 31, 8494, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Singh, S.P., Schwartz, M.P., Tokuda, E.Y., et al. A synthetic modular approach for modeling the role of the 3D microenvironment in tumor progression. Sci Rep 5, 17814, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Huszthy, P.C., Daphu, I., Niclou, S.P., et al. In vivo models of primary brain tumors: pitfalls and perspectives. Neuro-Oncology 14, 979, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Li, A., Walling, J., Kotliarov, Y., et al. Genomic changes and gene expression profiles reveal that established glioma cell lines are poorly representative of primary human gliomas. Mol Cancer Res 6, 21, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ridky, T.W., Chow, J.M., Wong, D.J., and Khavari, P.A.. Invasive three-dimensional organotypic neoplasia from multiple normal human epithelia. Nat Med 16, 1450, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mahesparan, R., Read, T.A., Lund-Johansen, M., Skaftnesmo, K.O., Bjerkvig, R., and Engebraaten, O.. Expression of extracellular matrix components in a highly infiltrative in vivo glioma model. Acta Neuropathol 105, 49, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bigner, S.H., Schold, S.C., Friedman, H.S., Mark, J., and Bigner, D.D.. Chromosomal composition of malignant human gliomas through serial subcutaneous transplantation in athymic mice. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 40, 111, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Joo, K.M., Kim, J., Jin, J., et al. Patient-specific orthotopic glioblastoma xenograft models recapitulate the histopathology and biology of human glioblastomas in situ. Cell Rep 3, 260, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Heffernan, J.M., and Sirianni, R.W.. Modeling Microenvironmental Regulation of Glioblastoma Stem Cells: a biomaterials perspective. Front Mater 5, 7, 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bahadur, S., Sahu, A.K., Baghel, P., and Saha, S.. Current promising treatment strategy for glioblastoma multiform: a review. Oncol Rev 13, 417, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fairbanks, B.D., Schwartz, M.P., Halevi, A.E., Nuttelman, C.R., Bowman, C.N., and Anseth, K.S.. A versatile synthetic extracellular matrix mimic via thiol-norbornene photopolymerization. Adv Mater Weinheim 21, 5005, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Shu, X.Z., Liu, Y., Luo, Y., Roberts, M.C., and Prestwich, G.D.. Disulfide cross-linked hyaluronan hydrogels. Biomacromolecules 3, 1304, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Anderson, S.B., Lin, C.C., Kuntzler, D.V., and Anseth, K.S.. The performance of human mesenchymal stem cells encapsulated in cell-degradable polymer-peptide hydrogels. Biomaterials 32, 3564, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Delpech, B., Maingonnat, C., Girard, N., et al. Hyaluronan and hyaluronectin in the extracellular matrix of human brain tumour stroma. Eur J Cancer 29A, 1012, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bigner S.H., Humphrey, P.A., Wong, A.J., et al. Characterization of the epidermal growth factor receptor in human glioma cell lines and xenografts. Cancer Res 50, 8017, 1990 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wong, A.J., Ruppert, J.M., Bigner, S.H., et al. Structural alterations of the epidermal growth factor receptor gene in human gliomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 89, 2965, 1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wang, C., Li, J., Sinha, S., Peterson, A., Grant, G.A., and Yang, F.. Mimicking brain tumor-vasculature microanatomical architecture via co-culture of brain tumor and endothelial cells in 3D hydrogels. Biomaterials 202, 35, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rao, S.S., Dejesus, J., Short, A.R., Otero, J.J., Sarkar, A., and Winter, J.O.. Glioblastoma behaviors in three-dimensional collagen-hyaluronan composite hydrogels. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 5, 9276, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Conrad, B., Han, L.H., and Yang, F.. Gelatin-Based Microribbon Hydrogels Accelerate Cartilage Formation by Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Three Dimensions. Tissue Eng Part A 24, 1631, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lee, S., Tong, X., Han, L.H., Behn, A., and Yang, F.. Winner of the Young Investigator Award of the Society for Biomaterials (USA) for 2016, 10th World Biomaterials Congress, May 17–22, 2016, Montreal QC, Canada: aligned microribbon-like hydrogels for guiding three-dimensional smooth muscle tissue regeneration. J Biomed Mater Res A 104, 1064, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wang, T., Lai, J.H., and Yang, F.. Effects of hydrogel stiffness and extracellular compositions on modulating cartilage regeneration by mixed populations of stem cells and chondrocytes in vivo. Tissue Eng Part A 22, 1348, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Jiguet Jiglaire, C., Baeza-Kallee, N., Denicolaï, E., et al. Ex vivo cultures of glioblastoma in three-dimensional hydrogel maintain the original tumor growth behavior and are suitable for preclinical drug and radiation sensitivity screening. Exp Cell Res 321, 99, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wu, C.X., Lin, G.S., Lin, Z.X., Zhang, J.D., Liu, S.Y., and Zhou, C.F.. Peritumoral edema shown by MRI predicts poor clinical outcome in glioblastoma. World J Surg Oncol 13, 97, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Rape, A., Ananthanarayanan, B., and Kumar, S.. Engineering strategies to mimic the glioblastoma microenvironment. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 79–80, 172, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Caliari, S.R., and Burdick, J.A.. A practical guide to hydrogels for cell culture. Nat Methods 13, 405, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Berry, R., Jowitt, T.A., Ferrand, J., et al. Role of dimerization and substrate exclusion in the regulation of bone morphogenetic protein-1 and mammalian tolloid. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106, 8561, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. da Silva, R., Uno, M., Marie, S.K., and Oba-Shinjo, S.M.. LOX expression and functional analysis in astrocytomas and impact of IDH1 mutation. PLoS One 10, e0119781, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Piret, J.P., Mottet, D., Raes, M., and Michiels, C.. Is HIF-1alpha a pro- or an anti-apoptotic protein. Biochem Pharmacol 64, 889, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Huang, W.J., Chen, W.W., and Zhang, X.. Glioblastoma multiforme: effect of hypoxia and hypoxia inducible factors on therapeutic approaches. Oncol Lett 12, 2283, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hardee, M.E., and Zagzag, D.. Mechanisms of glioma-associated neovascularization. Am J Pathol 181, 1126, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Cuddapah, V.A., Robel, S., Watkins, S., and Sontheimer, H.. A neurocentric perspective on glioma invasion. Nat Rev Neurosci 15, 455, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Pedron, S., Becka, E., and Harley, B.A.. Spatially gradated hydrogel platform as a 3D engineered tumor microenvironment. Adv Mater Weinheim 27, 1567, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Singh, S.P., Schwartz, M.P., Lee, J.Y., Fairbanks, B.D., and Anseth, K.S.. A peptide functionalized poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) hydrogel for investigating the influence of biochemical and biophysical matrix properties on tumor cell migration. Biomater Sci 2, 1024, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Osswald, M., Jung, E., Sahm, F., et al. Brain tumour cells interconnect to a functional and resistant network. Nature 528, 93, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Cox, T.R., and Erler, J.T.. Remodeling and homeostasis of the extracellular matrix: implications for fibrotic diseases and cancer. Dis Model Mech 4, 165, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Viapiano, M.S., and Lawler, S.E. Glioma Invasion: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Challenges. In: Meir, E., ed. CNS Cancer: Models, Markers, Prognostic Factors, Targets, and Therapeutic Approaches. New York City, Humana Press, 2009, pp. 1219–1252 [Google Scholar]

- 57. Rao, J.S. Molecular mechanisms of glioma invasiveness: the role of proteases. Nat Rev Cancer 3, 489, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Gladson, C.L. The extracellular matrix of gliomas: modulation of cell function. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 58, 1029, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Friedman, H.S., Kerby, T., and Calvert, H.. Temozolomide and treatment of malignant glioma. Clin Cancer Res 6, 2585, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Roos, W.P., Batista, L.F., Naumann, S.C., et al. Apoptosis in malignant glioma cells triggered by the temozolomide-induced DNA lesion O6-methylguanine. Oncogene 26, 186, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Agarwala, S.S., and Kirkwood, J.M.. Temozolomide, a novel alkylating agent with activity in the central nervous system, may improve the treatment of advanced metastatic melanoma. Oncologist 5, 144, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Edmondson, R., Broglie, J.J., Adcock, A.F., and Yang, L.. Three-dimensional cell culture systems and their applications in drug discovery and cell-based biosensors. Assay Drug Dev Technol 12, 207, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. He, W., Kuang, Y., Xing, X., et al. Proteomic comparison of 3D and 2D glioma models reveals increased HLA-E expression in 3D models is associated with resistance to NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity. J Proteome Res 13, 2272, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Chaudhuri, O., Gu, L., Klumpers, D., et al. Hydrogels with tunable stress relaxation regulate stem cell fate and activity. Nat Mater 15, 326, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Wisdom, K.M., Adebowale, K., Chang, J., et al. Matrix mechanical plasticity regulates cancer cell migration through confining microenvironments. Nat Commun 9, 4144. 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]