Abstract

Background

The full utility of an acute treatment requires examination of the entire time course of effect during a migraine attack. Here the time course of effect of ubrogepant is evaluated.

Methods

ACHIEVE-I and -II were double-blind, single-attack, Phase 3 trials. Adults with migraine were randomised 1:1:1 to placebo or ubrogepant (50mg or 100mg, ACHIEVE-I; 25 mg or 50 mg, ACHIEVE-II). Pain freedom, absence of most bothersome symptom, and pain relief were assessed at various timepoints. Samples were collected for pharmacokinetic analysis. Data were pooled for this post-hoc analysis.

Results

Participants’ (n = 912 placebo, n = 887 ubrogepant 50 mg, pooled analysis population) mean age was 41 years, with a majority female and white. Pain relief separated from placebo by 1 h (43% versus 37% [OR, 95% CI: 1.30, 1.0–1.59]), absence of most bothersome symptom by 1.5 h (28% versus 22% [1.42, 1.14–1.77]), and pain freedom by 2 h (20% vs. 13% [1.72, 1.33–2.22]). Efficacy was sustained from 2–24 h (pain relief: 1.71, 1.1–2.6; pain freedom: 1.71, 1.3–2.3) and remained separated at 48 h (pain relief: 1.7, 1.1–2.6; pain freedom: 1.31, 1.0–1.7). Pharmacokinetic analysis demonstrated maximum plasma concentrations were achieved at 1 h, with pharmacologically active concentrations reached within 11 min and remaining above the EC90 for nearly 12 h.

Conclusions

Evaluation of the time course of effect of ubrogepant showed pain relief as the most sensitive and earliest measure of clinical effect, followed by absence of most bothersome symptom, and pain freedom. Efficacy was demonstrated out to 48 h, providing evidence of the long-lasting effect of ubrogepant. This evaluation supports the role of examining the entire time course of effect to understand fully the utility of an acute treatment for migraine.

Trial registration: ACHIEVE I (ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT02828020) and ACHIEVE II (ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT02867709)

Keywords: Migraine, acute, calcitonin gene-related peptide

Introduction

Despite the highly prevalent and debilitating nature of migraine, there are still considerable unmet treatment needs (1,2). Several acute treatments for migraine, often divided into migraine-specific and non-specific, are currently available and recommended at some level (3). Migraine-specific treatments include triptans and ergots, and have evidence of efficacy in reducing migraine headache pain and associated symptoms (4,5). Non-specific treatments address the pain associated with migraine, and also treat other forms of pain or nausea. Non-specific treatments include simple analgesics, such as aspirin, acetaminophen, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; anti-emetics such as metoclopramide and phenothiazines; and opioids and combination analgesics.

For some people with migraine, however, currently available acute treatments have limitations including challenges with tolerability and/or achieving sufficient or consistent efficacy (6). Others, such as triptans and ergots, have cardiovascular contraindications (7). Furthermore, most available acute medications are complicated by their association with medication overuse (8,9). Thus, there remains a need for new acute treatment options for migraine that expand the eligible patient population, as well as providing rapid and sustained response with minimal side effects and consistent benefits from attack to attack (10).

Recently, efficacy endpoints have evolved in acute treatment trials for migraine. Current trial guidance specifies assessment of pain freedom and absence of most bothersome symptom at 2 h post dose as the co-primary endpoints (11,12). However, with a median duration of untreated migraine attacks in the population being approximately 24 h, long duration of efficacy is also important but not captured in primary endpoints (13). Characterisation of an acute treatment’s time course and magnitude of clinical response can be examined based on an individual’s response over time or on a group level. When group levels are investigated, response rates can be assessed for each of the measures at different time points and may require large sample sizes to evaluate meaningful differences. Group level data do not necessarily inform the response of an individual patient, so some caution in interpretation is warranted. More important in some ways, as use of rescue medication and/or a second dose of trial treatment after the 2-h primary timepoint are often allowed in acute treatment trials, the data after 2 h are confounded. Correlating pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic data can also help to understand further the time course and magnitude of efficacy that may be expected with a novel acute treatment for migraine and may offer insights into mechanism of action.

Ubrogepant is a small molecule, orally available CGRP receptor antagonist (gepant), approved in the United States for the acute treatment of migraine, with established efficacy and safety across two double-blind, placebo-controlled trials and a long-term safety trial (14–16). In the phase 3 trials examining ubrogepant 25 mg, 50 mg, and 100 mg, the primary endpoints of 2-h pain freedom and 2-h absence of most bothersome symptom were achieved by 19–22% and 34–39% of ubrogepant-treated participants versus 12–14% and 27–28% for placebo, respectively, with minimal adverse events reported.

The goal of this analysis was to examine the time course of efficacy of ubrogepant to assess the earliest signals, magnitude, and duration of effect from two phase 3 trials, ACHIEVE I (ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT02828020) and ACHIEVE II (ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT02867709). This analysis focuses on the pooled 50 mg dose of ubrogepant as it was the only dose common to both trials and provides stable and highly relevant data on the time course of efficacy. The data have been presented in preliminary form for the first time at the Annual Scientific Meeting of the American Headache Society (11–14 July 2019, Philadelphia, PA) (17).

Methods

Trial design

The full trial methods for ACHIEVE I and ACHIEVE II have been reported previously (14,15). Briefly, adults with a history of migraine with or without aura were enrolled and randomised to placebo, ubrogepant 50 mg, or ubrogepant 100 mg in ACHIEVE I and placebo, ubrogepant 25 mg, or ubrogepant 50 mg in ACHIEVE II. ACHIEVE I was conducted at 89 centres in the United States from 22 July 2016 to 14 December 2017. ACHIEVE II was conducted at 99 centres in the United States from 26 August 2016 to 26 February 2018. In both trials, there were four clinic visits including screening (visit 1) and randomisation (visit 2). After randomisation, participants had up to 60 days to treat a migraine of moderate or severe pain intensity. Visit 3 occurred 2–7 days after treatment of the qualifying migraine. Follow-up phone calls occurred 14 days after treatment. The safety follow-up visit (visit 4) occurred at 4 weeks post-treatment.

The trials were approved by properly constituted local or central Institutional Review Boards for each participating centre. Written consent was obtained from all participants prior to enrolment in the trials. This paper focuses on the post-hoc analysis of the pooled placebo and ubrogepant 50 mg treatment groups.

Participants

Both trials included adults 18–75 years of age, with migraine onset before 50 years of age, and with at least a 1-year history of migraine with or without aura, diagnosed using the International Classification of Headache Disorders 3rd edition, beta version (18). Participants’ history included migraine lasting 4–72 h when left untreated or when treatment was unsuccessful, migraine with at least 48 h of pain freedom between attacks, and 2 to 8 migraine attacks per month with moderate to severe pain in each of the 3 months prior to screening. The trials excluded those with a history of 15 or more headache days per month, on average, within 6 months prior to screening, or a diagnosis of chronic migraine. However, participants with a previous diagnosis of chronic migraine who, in the opinion of the investigator, had fewer than 15 headache days per month due to concomitant preventive treatment were allowed in the trial. Participants were not allowed to have taken an acute treatment for migraine on 10 or more days in any of the 3 months prior to screening or to have participated in a trial with an injectable anti-CGRP monoclonal antibody. A complete list of inclusion and exclusion criteria can be found in the primary publications (14,15).

Treatment

Trial treatment was allocated using an interactive web response system; participants, site personnel, and the trial sponsor personnel were blinded to the treatment assignment.

Treatment was administered as two tablets of placebo/placebo, ubrogepant 50 mg/placebo, or ubrogepant 50 mg/ubrogepant 50 mg in ACHIEVE I and one tablet of placebo, ubrogepant 25 mg, or ubrogepant 50 mg in ACHIEVE II. An optional second dose of trial treatment or rescue medication was allowed 2–48 h after the initial dose for moderate or severe headache pain. Rescue medication was not allowed for at least 2 h after an optional second dose of trial treatment. For participants who took an optional second dose of trial treatment, those who were randomised to ubrogepant for their initial dose were re-randomised to placebo or ubrogepant. Those who were randomised to placebo initially received placebo for their optional second dose of trial treatment. If a participant took rescue medication rather than the optional second dose of trial treatment, a second dose of trial treatment was not allowed.

Efficacy endpoints

In ACHIEVE I and ACHIEVE II, the two co-primary efficacy endpoints were pain freedom and absence of the most bothersome non-headache migraine-associated symptom, both at 2 h after the initial dose. Pain freedom was defined as reduction of a headache with moderate or severe pain to no pain at 2 h after the initial dose. The most bothersome migraine-associated symptom of either nausea, photophobia, or phonophobia, was identified by the participant prior to treating their migraine attack. Secondary efficacy endpoints included pain relief, sustained pain freedom from 2–24 h, and sustained pain relief from 2–24 h. Pain relief was defined as reduction of a headache with moderate or severe pain to mild or no pain. Sustained pain relief was defined as pain relief at 2 h with no administration of an optional second dose of trial treatment or rescue medication and with no occurrence of a moderate or severe headache up to 24 h post dose. Sustained pain freedom was defined similarly, as pain free at 2 h with no administration of an optional second dose of trial treatment or rescue medication and with no occurrence of a mild, moderate, or severe headache up to 24 h post dose. Other efficacy analyses included pain freedom, pain relief, and absence of most bothersome symptom at 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 3, 4, 6, 8, 24, and 48 h post initial dose. Analyses presented were pre-specified in the individual trials except for the censoring of data after use of an optional second dose or rescue medication using a multiple imputation method, test of treatment by study interaction, linear trend test, and the pooling of data between trials. Data collected after the 2-h time point included those who took rescue medication or an optional second dose of trial treatment. Since endpoints were assessed at prespecified, fixed timepoints, the precise time of onset of efficacy cannot be determined from these trials.

Pharmacokinetic analyses

A detailed pharmacokinetic analysis was conducted on a subset of participants who provided consent at all participating sites. Pharmacokinetic samples were collected using a dried blood spot (DBS) method (19). Six samples were collected for pharmacokinetic analysis at the post-treatment visit (visit 3) in conjunction with the administration of an additional single dose of trial treatment at the clinic (one pre-dose sample and five post dose samples at 0.5, 1, 2, 4, and at any time between 5 and 12 h). Participants were allowed to collect the 2, 4, and 5–12-h samples at home. Participants were not required to have a headache at the time of the pharmacokinetic analysis.

Non-compartmental analysis was performed using Phoenix WinNonlin® software (Version 8.0. Princeton, NJ: Certara; 2019). For serial pharmacokinetic analyses, a non-compartmental approach is preferred as it provides an unbiased presentation of the data, requiring fewer assumptions (20). The pharmacokinetic parameters were calculated using a model-independent approach based on standard equations and included area under the blood concentration versus time curve from time 0 to time t (AUC0-last), where t is the last collected time point, maximum blood concentration (Cmax), and time at the maximum blood concentration (Tmax). Pharmacokinetic parameters were only generated for those who had a sufficient concentration-time profile established. Missing and undetectable values were not included in the analyses.

Safety and tolerability

Adverse events were evaluated 48 h and 30 days after administration of trial treatment. Clinical laboratory tests, vital signs, electrocardiograms, and Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating scale were also evaluated.

Statistical analysis

A full description of the statistical analyses used in ACHIEVE I and ACHIEVE II has been reported (14,15). The population described as the modified intent-to-treat (mITT) population was used to conduct efficacy analyses. This population was defined, per protocol, as all randomised participants who received at least one dose of trial treatment, recorded a baseline migraine headache severity measurement, and had at least one post-dose migraine headache severity or migraine-associated symptom measurement at or before the 2-h timepoint. This paper focuses on a post-hoc analysis of the pooled ubrogepant 50 mg and placebo data from both ACHIEVE trials. Data were pooled to increase sample size as the individual trials were not powered to detect differences for this efficacy-by-timepoint analysis. The safety population included all randomised participants who received at least one dose of trial treatment. The pharmacokinetic analysis population consisted of those participants who consented to participate in the pharmacokinetic sub-study at visit 3 and provided up to six serial pharmacokinetic samples to allow for calculation of pharmacokinetic parameters. Descriptive statistics were calculated for all pharmacokinetic parameters. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS® software (Version 9.4. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc.; 2013)

Due to the different test objectives, the data were handled in two ways to address data collected after rescue medication or an optional second dose of trial treatment. The first method aimed to test the treatment regimen effect. It imputed missing data (i.e. data not reported) using last observation carried forward (LOCF) regardless of the use of rescue medication or optional second dose of trial treatment. This was the primary, pre-specified missing data imputation method. The second method aimed to test the first dose effect by removing data after the use of an optional second dose or rescue medication. It set data collected after taking rescue medication or an optional second dose as “missing” if the second dose or rescue mediation was taken before the diary window open time for each timepoint. The missing data, including data not reported and data after the use of an optional second dose or rescue medication, were then imputed using multiple imputation. A fully conditional specification method was used to create 100 imputations. The same logistic regression model was used to analyse each imputation dataset. The final estimates were produced by pooling estimates across the imputation datasets. For pain freedom, pain relief, and absence of most bothersome non-headache migraine-associated symptom at various timepoints after the initial dose, the proportions were summarised by time point and treatment group. Response difference and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) are reported. The treatment comparisons were conducted using a logistic regression model with categorical terms for treatment group, historical triptan response, use of medication for migraine prevention, and baseline headache pain severity. For the absence of most bothersome non-headache migraine-associated symptom, an additional categorical term of the symptom identified as the most bothersome (i.e. phonophobia, photophobia, or nausea) was included in the model. Odds ratios and the corresponding 95% CI and raw p-values with no multiplicity adjustment are reported arising from the model for the pooled analyses. Heterogeneity of the trials was tested using the interaction of the trials and treatment. Type 1 error rate was not controlled in these post-hoc analyses. For sustained pain relief and sustained pain freedom, analyses were based on determinable cases. Raw p-values are provided to allow evaluation of the evidence against the null hypothesis, but due to the post-hoc nature of the analysis, conservative statistical significance threshold may be used.

In order to explore further the trends, a linear trend test was used to assess the continued increase observed in treatment response. The trend was tested at 2, 3, and 4 h as this was the time frame where the greatest response differences were generally observed across efficacy endpoints. To test for linear trends across 2, 3, and 4 h after the initial dose, a generalised linear mixed model was fitted with using observed data at 2, 3, and 4 h after the initial dose. The model specifies a binomial distribution with a logit link and includes terms for treatment group, historical triptan response, use of medication for migraine prevention, baseline headache severity, and hour as fixed effects, and treatment by hour as interaction terms, with an unstructured covariance matrix for within-subject repeated measures. A linear contrast was used to test the linear trend across 2, 3 and 4 h. For the most bothersome endpoint analysis, an additional underlying symptom fixed effect was added in the model for the identified symptom.

Results

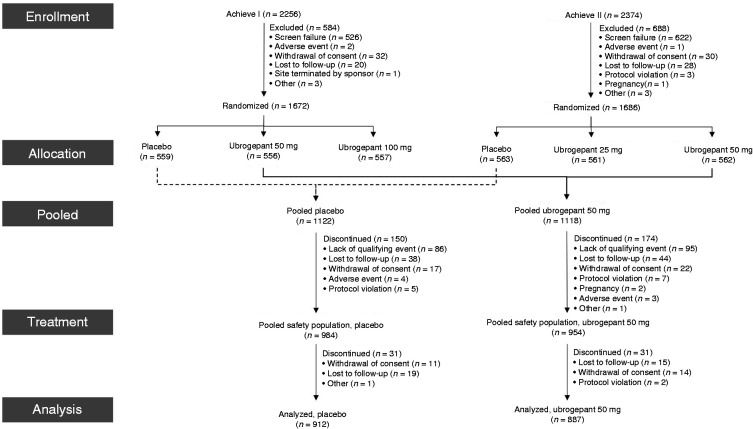

A total of 3358 participants were randomised into the ACHIEVE I and ACHIEVE II trials (Figure 1). Across both trials, 2240 participants were randomised to either placebo or ubrogepant 50 mg. The pooled safety population included 1938 participants and the analysis population included 1799 participants, with 912 randomised to placebo and 887 randomised to ubrogepant 50 mg. No major differences were observed in participant discontinuation rates and reasons for discontinuation between groups. Following treatment, 31 participants discontinued from both the placebo and ubrogepant 50 mg groups with the most common reasons being withdrawal of consent and loss to follow-up (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Participant disposition.

Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics were similar between the pooled treatment groups (Table 1). Mean age was 41 years (SD = 12) for placebo and 40 years (SD = 12) for ubrogepant 50 mg, with the majority being female (89%) and white (82%). Approximately a quarter of the participants were using a concomitant preventive medication (e.g. beta-blockers, tricyclic antidepressants, topiramate, valproic acid, onabotulinumtoxinA). More participants treated a migraine with moderate headache pain in comparison to severe pain for both placebo (60% vs. 40%) and ubrogepant 50 mg (62% vs. 38%) groups. Photophobia was the most commonly reported most bothersome non-headache migraine-associated symptom.

Table 1.

Baseline participant demographics and clinical characteristics (pooled mITT population for ACHIEVE I and ACHIEVE II).

| Parameter | Placebo(n = 912) | Ubrogepant50 mg (n = 887) |

|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) Age, years | 41.1 (11.9) | 40.4 (12.1) |

| Female, n (%) | 809 (88.7) | 803 (90.5) |

| White, n (%) | 754 (82.7) | 728 (82.1) |

| Concomitant preventive medication, n (%) | 217 (23.8) | 212 (23.9) |

| Headache severity, n (%) | ||

| Moderate | 545 (59.8) | 549 (61.9) |

| Severe | 367 (40.2) | 338 (38.1) |

| MBS, n (%) | ||

| Photophobia | 499 (54.7) | 513 (57.8) |

| Phonophobia | 234 (25.7) | 197 (22.2) |

| Nausea | 177 (19.4) | 173 (19.5) |

| Missing | 2 (0.2) | 4 (0.5) |

MBS: most bothersome migraine-associated symptom; SD: standard deviation.

Time course of efficacy

In the logistic regression analysis, a test of the heterogeneity of the trials showed no significant variability in effect between trials by treatment for all timepoints of the three endpoints reported (p ≥ 0.09) (Supplementary Table 1).

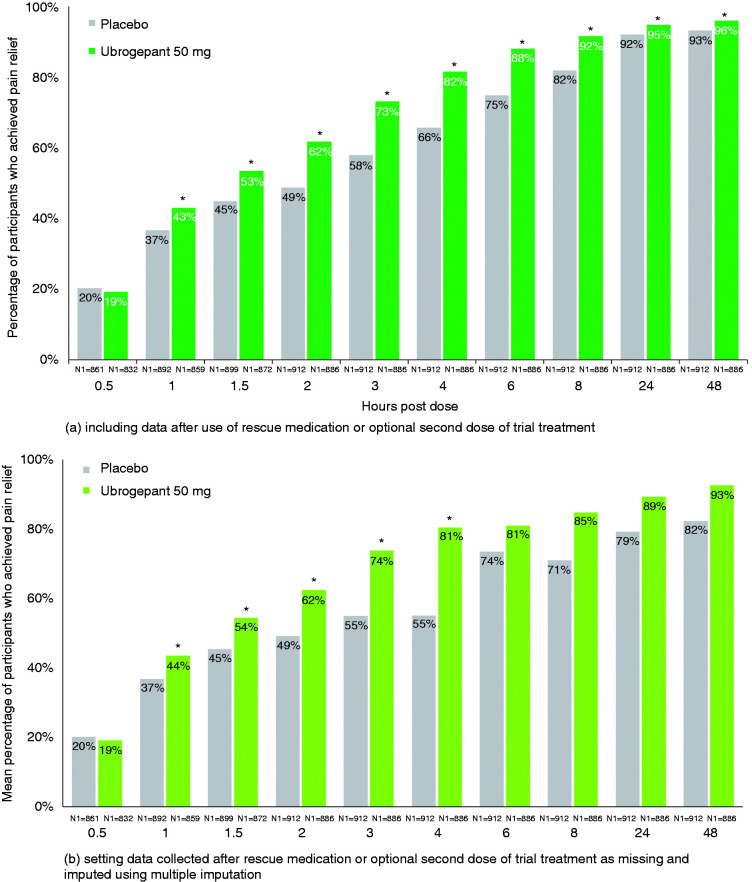

Pain relief

For pain relief, the earliest statistical separation from placebo was achieved at 1 h, with 43% of ubrogepant 50 mg-treated participants (OR [95% CI]: 1.30 [1.06–1.59], p = 0.010 versus placebo) versus 37% of placebo-treated participants achieving reduction of their moderate to severe headache pain to mild or no pain in the pooled analyses (Figure 2(a), Table 2). After 1 h, differences from placebo continued to increase, with a maximum difference observed at 4 h (OR [95% CI]: 2.36 [1.89–2.95], p < 0.001). The linear trend test confirmed this observation and indicated a linear trend at 2, 3, and 4 h (p = 0.006) for ubrogepant 50 mg versus placebo. The separation between ubrogepant and placebo decreased at 24 h (OR [95% CI]: 1.58, 1.08–2.32; p = 0.019) and 48 h (1.71,1.12–2.62; p = 0.013), however remaining in favour of ubrogepant-treated participants through 48 h. These results include data collected after rescue medication or an optional second dose of trial treatment. For the analyses that excluded data after use of rescue medication or optional second dose and used multiple imputation, which examined the efficacy of a single, initial dose of trial treatment, trends were similar, with earliest separation from placebo at 1 h and a maximum difference at 4 h (Figure 2(b), Table 3).

Figure 2.

Pain relief by timepoint – pooled mITT population from ACHIEVE I and ACHIEVE II.

*Indicates p < 0.05 versus placebo. N1 = number of patients with non-missing post-dose pain severity assessment at or prior to the timepoint in the modified intent-to-treat population. For the analysis that included data after use of rescue medication or optional second dose of trial treatment, missing data were handled using last observation carried forward. Response rates presented following multiple imputation represent a mean across 100 imputations. Odds ratio (95% CI) and p-value are based on logistic regression with treatment group, historical triptan response, use of medication for migraine prevention, and baseline headache severity as explanatory variables; these data are provided in Table 2 and Table 3. Percentages calculated as 100 × (n/N1).

Table 2.

Relative odds of achieving each efficacy outcome by timepoint for ubrogepant 50 mg versus placebo (pooled mITT population from ACHIEVE I and ACHIEVE II) – includes data after use of rescue medication or optional second dose of trial treatment.

|

Pain relief |

Absence of MBS |

Pain freedom |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hours post dose | Odds ratio(95% CI) | p-value | Response differencea% (95% CI) | Odds ratio (95% CI) | p-value | Response differencea% (95% CI) | Odds ratio (95% CI) | p-value | Response differencea% (95% CI) |

| 0.5 | 0.90 (0.70, 1.15) | 0.38 | −1.09 (−4.89, 2.70) | 1.00 (0.67, 1.50) | 0.998 | 0.11 (−2.18, 2.39) | 1.38 (0.60, 3.14) | 0.45 | 0.52 (−0.61, 1.65) |

| 1 | 1.30 (1.06, 1.59) | 0.010 | 6.30 (1.72, 10.88) | 1.11 (0.86, 1.44) | 0.41 | 1.53 (−1.93, 5.00) | 0.80 (0.51, 1.25) | 0.32 | −0.85 (−2.84, 1.14) |

| 1.5 | 1.41 (1.16, 1.71) | <0.001 | 8.50 (3.86, 13.14) | 1.42 (1.14, 1.77) | 0.002 | 6.35 (2.31, 10.40) | 1.22 (0.90, 1.67) | 0.20 | 2.01 (−0.84, 4.86) |

| 2 | 1.73 (1.42, 2.10) | <0.001 | 13.05 (8.50, 17.61) | 1.68 (1.37, 2.05) | <0.001 | 11.15 (6.82, 15.48) | 1.72 (1.33, 2.22) | <0.001 | 7.49 (4.05, 10.94) |

| 3 | 2.03 (1.66, 2.49) | <0.001 | 15.24 (10.91, 19.58) | 1.95 (1.61, 2.37) | <0.001 | 16.05 (11.52, 20.59) | 2.03 (1.64, 2.51) | <0.001 | 14.18 (10.04, 18.31) |

| 4 | 2.36 (1.89, 2.95) | <0.001 | 15.92 (11.92, 19.92) | 2.06 (1.70, 2.50) | <0.001 | 17.14 (12.60, 21.68) | 2.06 (1.69, 2.51) | <0.001 | 16.55 (12.13, 20.97) |

| 6 | 2.56 (1.98, 3.31) | <0.001 | 13.37 (9.84, 16.90) | 2.01 (1.64, 2.46) | <0.001 | 15.43 (11.05, 19.81) | 1.99 (1.64, 2.40) | <0.001 | 16.79 (12.23, 21.35) |

| 8 | 2.44 (1.82, 3.27) | <0.001 | 9.74 (6.65, 12.83) | 2.00 (1.62, 2.48) | <0.001 | 13.66 (9.55, 17.76) | 2.12 (1.75, 2.57) | <0.001 | 17.71 (13.24, 22.19) |

| 24 | 1.58 (1.08, 2.32) | 0.019 | 2.81 (0.52, 5.10) | 1.73 (1.34, 2.24) | <0.001 | 7.42 (4.01, 10.84) | 1.51 (1.22, 1.87) | <0.001 | 8.11 (4.00, 12.21) |

| 48 | 1.71 (1.12, 2.62) | 0.013 | 2.74 (0.65, 4.82) | 1.34 (1.01, 1.79) | 0.043 | 3.19 (0.14, 6.25) | 1.31 (1.04, 1.66) | 0.022 | 4.32 (0.63, 8.01) |

Note: Odds ratio (95% CI) and p-value are based on logistic regression with treatment group, historical triptan response, use of medication for migraine prevention, and baseline headache severity as explanatory variables.

aPlacebo-corrected response difference (ubrogepant vs. placebo).

Table 3.

Relative odds of achieving each efficacy outcome by timepoint for ubrogepant 50 mg versus placebo (pooled mITT population from ACHIEVE I and ACHIEVE II) – data after use of rescue medication or optional second dose of trial treatment set as missing and imputed multiple imputation.

|

Pain relief |

Absence of MBS |

Pain freedom |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hours post dose | Odds ratio (95% CI) | p-value | Response differencea% (95% CI) | Odds ratio (95% CI) | p-value | Response differencea% (95% CI) | Odds ratio (95% CI) | p-value | Response differencea% (95% CI) |

| 0.5 | 0.91 (0.71, 1.16) | 0.44 | −0.98 (−4.72, 2.76) | 1.02 (0.68, 1.52) | 0.94 | 0.13 (−2.16, 2.43) | 1.38 (0.61, 3.14) | 0.44 | 0.55 (−0.66, 1.77) |

| 1 | 1.33 (1.08, 1.63) | 0.006 | 6.77 (2.17, 11.37) | 1.13 (0.87, 1.46) | 0.36 | 1.68 (−1.86, 5.23) | 0.81 (0.52, 1.27) | 0.35 | −0.83 (−2.95, 1.29) |

| 1.5 | 1.45 (1.19, 1.76) | <0.001 | 9.00 (4.32, 13.69) | 1.45 (1.16, 1.82) | 0.001 | 6.90 (2.75, 11.04) | 1.23 (0.90, 1.69) | 0.19 | 2.19 (−0.83, 5.22) |

| 2 | 1.74 (1.43, 2.13) | <0.001 | 13.19 (8.56, 17.82) | 1.68 (1.37, 2.06) | <0.001 | 11.29 (6.86, 15.71) | 1.72 (1.32, 2.24) | <0.001 | 7.64 (4.04, 11.24) |

| 3 | 2.42 (1.63, 3.61) | <0.001 | 18.85 (10.70, 27.01) | 1.80 (1.35, 2.38) | <0.001 | 14.38 (7.58, 21.17) | 2.22 (1.65, 2.97) | <0.001 | 17.9 (11.6, 24.3) |

| 4 | 3.55 (2.14, 5.89) | <0.001 | 25.40 (15.98, 34.82) | 2.01 (1.48, 2.74) | <0.001 | 16.46 (9.37, 23.56) | 2.20 (1.62, 3.00) | <0.001 | 19.10 (11.89, 26.32) |

| 6 | 1.57 (0.77, 3.22) | 0.22 | 7.53 (−4.48, 19.53) | 2.43 (1.65, 3.58) | <0.001 | 19.68 (11.05, 28.30) | 1.74 (1.21, 2.48) | 0.003 | 13.42 (4.79,22.05) |

| 8 | 2.37 (0.95, 5.93) | 0.065 | 13.78 (−0.81, 28.38) | 3.07 (1.96, 4.81) | <0.001 | 21.40 (12.82,29.97) | 2.45 (1.67, 3.59) | <0.001 | 19.61 (11.33, 27.89) |

| 24 | 2.35 (0.74, 7.47) | 0.15 | 10.02 (−3.67, 23.71) | 2.21 (1.26, 3.89) | 0.006 | 10.79 (2.60, 18.98) | 1.36 (0.82, 2.26) | 0.23 | 5.19 (−3.58, 13.97) |

| 48 | 3.08 (0.73, 12.92) | 0.12 | 10.38 (−3.52, 24.28) | 1.44 (0.71, 2.90) | 0.31 | 4.15 (−3.85, 12.16) | 1.31 (0.69, 2.48) | 0.41 | 3.9 (−5.5, 13.4) |

Note: Odds ratio (95% CI) and p-value are based on logistic regression with treatment group, historical triptan response, use of medication for migraine prevention, and baseline headache severity as explanatory variables.

aPlacebo-corrected response difference (ubrogepant vs. placebo).

Table 4.

Treatment Emergent Adverse Events (Pooled Safety Population for ACHIEVE I and ACHIEVE II).

| Parameter | Placebo (N = 984) | Ubrogepant 50 mg (N = 954) |

|---|---|---|

| At least one TEAE within 48h post any dose | 113 (11.5) | 107 (11.2) |

| Treatment-related | 71 (7.2) | 69 (7.2) |

| SAE | 0 | 0 |

| TEAEs reported in ≥1% participants within 48 hours | ||

| Nausea | 18 (1.8) | 18 (1.9) |

| Dizziness | 11 (1.1) | 11 (1.2) |

| At least one TEAE within 30d post any dose | 225 (22.9) | 259 (27.1) |

| Treatment-related | 88 (8.9) | 90 (9.4) |

| SAE | 0 | 3 (0.3) |

| Treatment-related SAE | 0 | 0 |

| TEAEs reported in ≥1% participants within 30 days | ||

| Nausea | 22 (2.2) | 21 (2.2) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 17 (1.7) | 18 (1.9) |

| Dizziness | 14 (1.4) | 18 (1.9) |

TEAE: treatment-emergent adverse event.

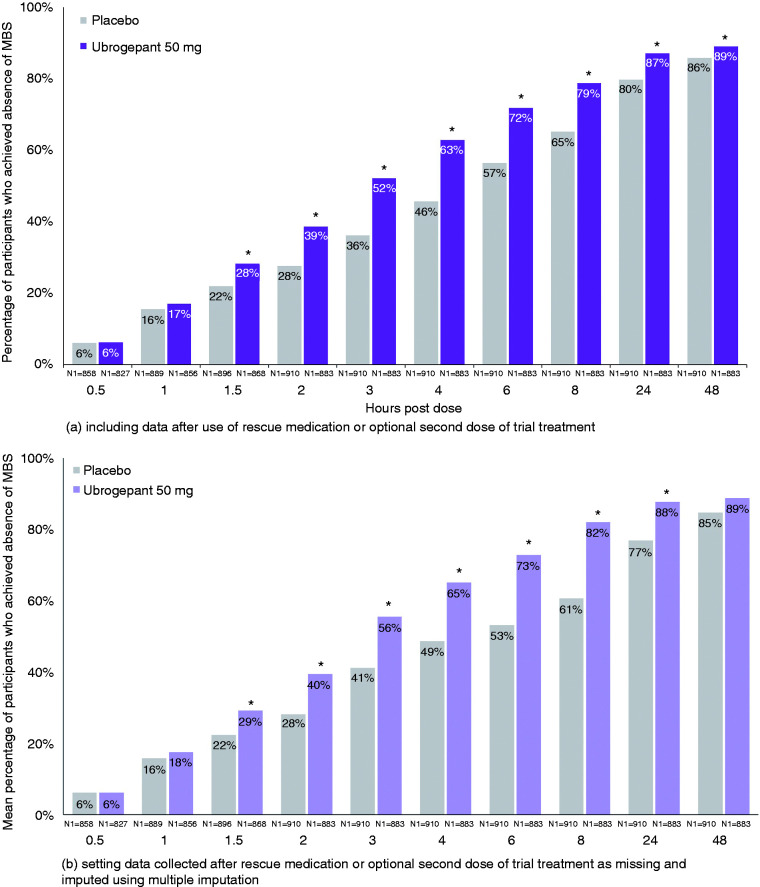

Most bothersome symptom

For most bothersome non-headache migraine-associated symptom, the earliest separation from placebo was achieved at 1.5 h in 28% of ubrogepant 50 mg-treated participants (OR, 95% CI: 1.42, 1.14–1.77; p = 0.002 vs. placebo) versus 22% of placebo-treated participants in the pooled analyses (Figure 3(a), Table 2). After 1.5 h, separation between ubrogepant and placebo increased, with a maximum difference favouring ubrogepant-treated participants reported at 4 h (2.09, 1.70–2.56; p < 0.001). This finding was confirmed with a linear trend reported at 2, 3, and 4 h (p = 0.0425) for ubrogepant 50 mg versus placebo. At 24 h (1.73, 1.34–2.24; p < 0.001) and 48 h (1.34, 1.01–1.79; p = 0.043), the separation decreased yet remained in favour of ubrogepant versus placebo. Data after 2 h included those who took rescue medication or an optional second dose of trial treatment. When data after the optional second dose or rescue medication were excluded, observations were similar, with earliest separation from placebo at 1.5 h and response differences continuing to increase and maximise at 8 h (3.07, 1.96–4.81; p < 0.001) (Figure 3(b), Table 3). Separation from placebo was observed up to 24 h.

Figure 3.

Absence of MBS by timepoint – pooled mITT population from ACHIEVE I and ACHIEVE II.

*Indicates p < 0.05 versus placebo. N1 = number of patients with non-missing post dose pain severity assessment at or prior to the timepoint in the modified intent-to-treat population. For the analysis that included data after use of rescue medication or optional second dose of trial treatment, missing data were handled using last observation carried forward. Response rates presented following multiple imputation represent a mean across 100 imputations. Odds ratio (95% CI) and p-value are based on logistic regression with treatment group, historical triptan response, use of medication for migraine prevention, and baseline headache severity as explanatory variables; these data are provided in Table 2 and Table 3. Percentages calculated as 100 × (n/N1).

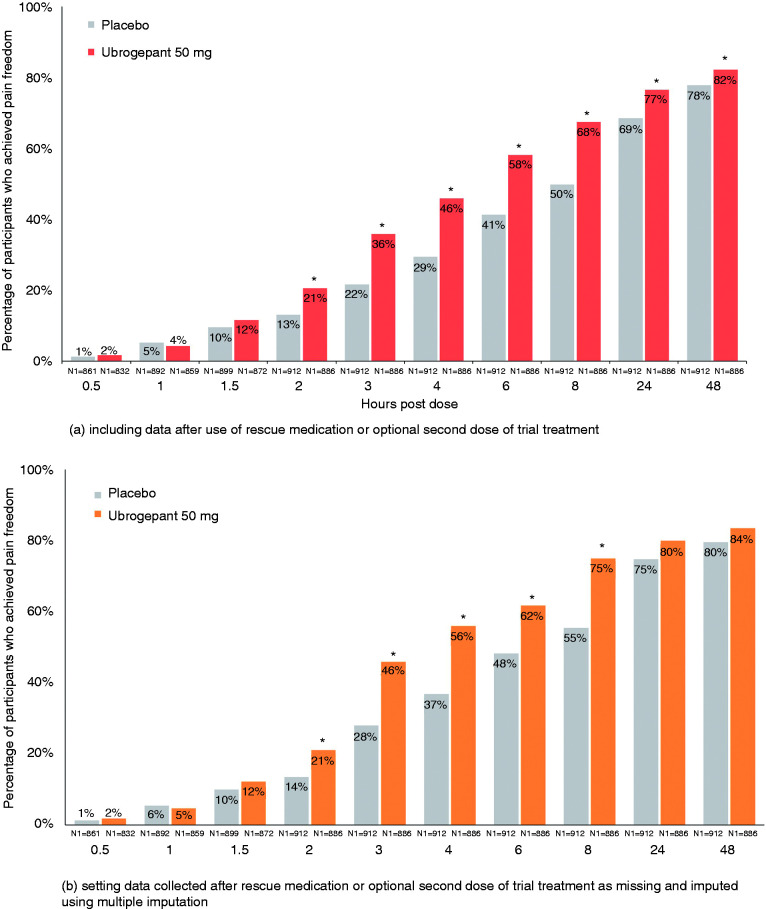

Pain freedom

For pain freedom, the earliest separation from placebo was achieved at 2 h in 21% of ubrogepant 50 mg-treated participants (OR, 95% CI: 1.72, 1.33–2.22; p < 0.001 versus placebo) compared to 13% of placebo-treated participants in the pooled analyses (Figure 4(a), Table 2). After 2 h, the separation between ubrogepant and placebo continued to increase, favouring ubrogepant-treated participants and was greatest at 8 h post dose (2.43, 1.96–3.00; p < 0.001), and remained in favour of ubrogepant through 24 h (1.51, 1.22–1.87; p < 0.001) and 48 h (1.31, 1.04–1.66; p = 0.022); however, a linear trend test at 2, 3, and 4 h for ubrogepant versus placebo did not confirm the observed trend (p = 0.17). Data from these analyses included those who took rescue medication or an optional second dose of trial treatment. When data from these participants were excluded (see Methods), earliest separation was again seen at 2 h and maximal at 8 h (Figure 4(b), Table 3).

Figure 4.

Pain freedom by timepoint – pooled mITT population from ACHIEVE I and ACHIEVE II.

*Indicates p < 0.05 versus placebo. N1 = number of patients with non-missing post dose pain severity assessment at or prior to the timepoint in the modified intent-to-treat population. For the analysis that included data after use of rescue medication or optional second dose of trial treatment, missing data were handled using last observation carried forward. Response rates presented following multiple imputation represent a mean across 100 imputations. Odds ratio (95% CI) and p-value are based on logistic regression with treatment group, historical triptan response, use of medication for migraine prevention, and baseline headache severity as explanatory variables; these data are provided in Table 2 and Table 3. Percentages calculated as 100 × (n/N1).

Time course data for ubrogepant 25 mg and 100 mg, doses that were studied in only one of the two ACHIEVE trials, were generally similar to the pooled ubrogepant 50 mg data (Supplementary Tables 2–4, Supplementary Figures 1–3).

Magnitude and duration of effect

Though the primary endpoints of these pivotal trials were pre-specified at 2 h, the magnitude of the treatment response difference between ubrogepant and placebo increased after this point in time in the pooled analyses (Table 2). For pain relief, the response difference between ubrogepant and placebo more than doubled from the 1-h (6.3%) to the 2-h time point (13.0%) and reached a maximum by 4 h (15.9%). For absence of most bothersome non-headache migraine-associated symptom, the treatment response difference between ubrogepant and placebo nearly doubled from 1.5 h (6.3%) to 2 h (11.1%) and was greatest by 4 h (17.1%). For pain freedom, the ubrogepant and placebo treatment response difference nearly doubled from 2 h (7.5%) to 3 h (14.2%) and was maximal at 8 h (17.7%). These results include data from participants who took rescue medication or an optional second dose of trial treatment. In the analyses that excluded these data (see Methods), similar trends were observed across all three endpoints (Table 3).

Measures of duration of effect (e.g. sustained pain relief, sustained pain freedom) were also superior in the ubrogepant-treated participants versus placebo. A higher proportion of participants treated with ubrogepant 50 mg (36.5% [315/862]; OR, 95% CI: 2.20, 1.78–2.74; p < 0.001) achieved sustained pain relief from 2 to 24 h versus placebo (20.9% [186/890]). For sustained pain freedom from 2 to 24 h, the proportion of responders were greater for ubrogepant-treated participants (13.6% [119/875]; OR [95% CI]: 1.71 [1.26–2.32], p < 0.001) versus placebo (8.4% [76/903]). These analyses included data collected after rescue medication or an optional second dose of trial treatment. In addition, efficacy was maintained through 48 h for all reported endpoints regardless of data handling method regarding rescue medication or second dose (Figures 2–4, Tables 2–3).

Data from the individual trials showed that the magnitude (Supplementary Tables 2–4, Supplementary Figures 1–3) and duration of effect (Supplementary Table 5) were generally greater for participants treated with ubrogepant 100 mg versus ubrogepant 25 mg, based on pain and symptom endpoints.

Pharmacokinetics

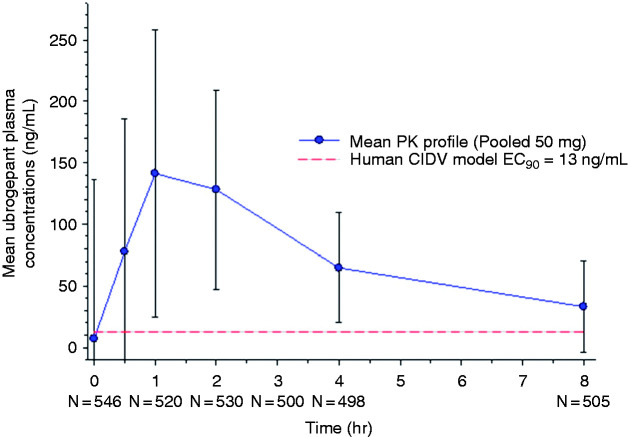

A total of 642 participants provided at least one pharmacokinetic sample at a clinic visit (i.e. not during the treated migraine attack), with 603 providing sufficient samples for a full pharmacokinetic profile to allow for calculation of pharmacokinetic parameters (Figure 5). A total of 34 participants had no detectable ubrogepant in their collected pharmacokinetic samples at the terminal phase following treatment with ubrogepant 50 mg, likely reflecting inter-person variability in systemic drug exposure and rate of elimination. For the pooled ubrogepant 50 mg group, in participants where levels were detected, the mean maximum ubrogepant concentration (Cmax) was 182 ng/mL with an average systemic exposure (AUC) of 441 ng·h/mL. The median time to reach the maximum ubrogepant blood concentration (Tmax) was 1 h (range = 0–26.5). Based on an EC90 of 13 ng/mL (23 nM) from a human capsaicin-induced dermal blood flow model, pharmacologically active concentrations were reached within 11 min and remained above the threshold for nearly 12 h (21).

Figure 5.

Mean ubrogepant 50 mg plasma concentration-time curve (n = 498; pooled data from ACHIEVE I and ACHIEVE II). Represents data collected from participants who took an additional single dose of trial treatment at the clinic for pharmacokinetic analysis at visit 3. Trendline indicates EC90 value derived from a human capsaicin-induced dermal vasodilation model.

Pharmacokinetic data from the individual trials showed a dose-dependent trend across ubrogepant doses with an increase in Cmax and AUC with an increase in dose (Supplementary Table 6, Supplementary Figure 4). The overall median Tmax was approximately 1.5 h across the individual trials with a Tmax of 1 h reported for ubrogepant 25 mg and 50 mg and 2 h for ubrogepant 100 mg.

Safety and tolerability

The proportion of participants who reported a treatment emergent adverse event (TEAE) was similar between the ubrogepant 50 mg and placebo groups (Table 3). Within 48 h after any dose of trial treatment, 7% of participants in both groups had a TEAE recorded that was considered related to treatment by the investigator; no serious adverse events were recorded at this timepoint. Within 30 days after any dose of trial treatment, 9% of participants in both groups had a TEAE recorded that was considered related to treatment by the investigator. Three participants in the ubrogepant 50 mg group had a serious adverse event recorded (i.e. appendicitis, pericardial effusion, spontaneous abortion); none were considered related to treatment by the investigator. In both the pooled ubrogepant 50 mg and placebo groups, the most commonly reported TEAE was nausea.

Discussion

Data from the pooled ACHIEVE I and ACHIEVE II trials showed that separation of ubrogepant 50 mg and placebo began with pain relief 1 h post treatment, followed by absence of most bothersome non-headache migraine-associated symptom at 1.5 h, and pain freedom at 2 h, with maximum differences versus placebo observed at 4 h post dose for pain relief and absence of most-bothersome symptom and at 8 h for pain freedom. Once separation was achieved, it was maintained for all three efficacy endpoints through 48 h, demonstrating the long duration of action of ubrogepant. Findings were similar in analyses that included or excluded data from participants following use of rescue medication or optional second dose of trial treatment.

The pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profile of a novel drug provides additional information to aid in the understanding of efficacy. Based on a human capsaicin-induced dermal vasodilation (CIDV) model, which studies the impact of CGRP blockade on blood flow in the forearm, the potential pharmacologically active concentration (EC90) of ubrogepant is 13 ng/mL (21). From this estimate, the EC90 is achieved within approximately 11 min after oral administration of ubrogepant 50 mg and remains above this threshold for nearly 12 h (Figure 3). The first clinical effect, pain relief, was observed at 1 h, when plasma concentrations were >10-fold higher than the EC90 and well after peripheral vascular antagonism is achieved. Furthermore, plasma levels of ubrogepant remain above the EC90 beyond 8 h post dose and with pain and symptom relief observed out to 24 and 48 h. Since the CIDV model only assesses the effect of peripheral vascular CGRP antagonism and not peripheral or central neural sites of ubrogepant action, it is not entirely surprising that the efficacy of ubrogepant for migraine relief does not uniformly align with pharmacologically active plasma concentrations in this model (22,23). A dissociation between predicted and controlled trial-established dosing is also seen with the canonical CGRP receptor monoclonal antibody, erenumab (24,25). There may be several steps required between peripheral vascular blockade and terminating the peripheral and central neuronal processes involved in maintaining a migraine attack or there may be a need for drug action in a different, restricted compartment, such as the central nervous system.

The route of administration also has the potential to impact efficacy profile including the onset, magnitude, and duration of effect. Olcegepant was a gepant developed as an intravenous acute treatment for migraine. While onset of efficacy was not reported, the magnitude of efficacy increased between 1 to 2 h and was shown to be maximal at 4 h, similar to data presented for the oral gepants, despite differences in route of administration (26–28). These findings further demonstrate that several factors are involved in the efficacy profile.

The primary endpoints used for regulatory marketing approval, pain freedom and absence of the most bothersome symptom at 2 h post dose, do not provide a complete assessment of treatment effect. Pain relief, return to function, and patient satisfaction are important patient-centred endpoints as well (10). Surveys of patient preferences and physician ratings of acute treatment attributes show rapid onset of effect is highly desired (10). In studies of over-the-counter medications, patients were satisfied if pain relief was achieved within 1 h after treatment administration and in a post-hoc analysis of rizatriptan randomised, controlled trials, 60–70% of patients with pain relief at 2 h were satisfied (29,30). Data presented here showed that pain relief was achieved within 1 h post dose. Further, efficacy beyond 2 h demonstrating duration of effect throughout the course of a migraine attack is also an important consideration. This was also demonstrated with ubrogepant with a sustained effect observed through 24 and 48 h.

Strengths and limitations

There are several strengths to these trials and analyses. The ACHIEVE trials were double-blind trials with a comprehensive safety evaluation that included adverse events evaluated and reported within 48 h and 30 days post initial or optional second dose of trial treatment. In addition, the trials were designed to mimic real-world practice and use, including the option for a second dose of trial treatment and the allowance of a broad range of rescue medications including triptans, ergotamines, NSAIDs, acetaminophen, and opioids.

As with many analyses, there are several limitations to consider when interpreting these data. The design of the trials, particularly the method of collecting data at prespecified timepoints, does not allow for the measurement of an actual onset of clinical effect. Rather, these trials provide data on the first measured clinical effect, which acts as a proxy for onset and is dependent on sample size. To measure optimally the onset, a trial participant would need to indicate the exact time that pain relief or pain freedom was achieved by using a stopwatch approach (31). In addition, due to differences in trials, including trial design, statistical methods, and participant populations, these data were not compared across drug trials and caution should be taken when interpreting differences in findings. The treatment of moderate or severe pain limits the generalisability of this data, as clinically the recommendation is to treat migraine when pain is mild. In addition, the reported p-values are not adjusted for multiple comparisons; however, these data show that once separation was achieved, it continued to separate at subsequent timepoints, indicating a lesser likelihood that the findings were by chance. Also, the combination of ubrogepant with other acute medications with different mechanisms of action and/or non-pharmacological techniques such as biofeedback, relaxation therapy, mindfulness, or cognitive behavioural therapy, was not evaluated in these clinical trials. In addition, the consistency with which ubrogepant achieves the outcomes assessed in this analysis across multiple attacks was not evaluated in either ACHIEVE I or ACHIEVE II.

Furthermore, this examination includes two methods of handling data following the use of rescue medication or an optional second dose of trial treatment. As both methods introduce bias in different ways, the inclusion of data using both methods increase the reliability of the findings as consistent trends were observed. However, there are additional limitations when using the multiple imputation method to handle data after the use of an optional second dose or rescue medication. The multiple imputation is based on a low percentage of available data. Furthermore, the trial was designed to test the treatment regimen (i.e. first dose plus optional second dose and/or rescue medication) and not designed to test the one dose effect.

Conclusions

The results suggest that pain relief was the most sensitive endpoint to detect early clinical effect, followed by absence of most bothersome non-headache migraine-associated symptom, and pain freedom. Further, efficacy observed out to 24 and 48 h provides evidence of ubrogepant’s long duration of action. The findings support the importance of assessing both pain and symptom endpoints across the entire time course of a migraine attack to fully understand the utility of ubrogepant as an acute treatment for migraine.

Clinical implications

Pain relief is the most sensitive endpoint to detect early clinical effect of ubrogepant.

After pain relief, absence of most bothersome symptom and pain freedom are achieved.

Efficacy of ubrogepant is observed out to 24 and 48 h.

The entire time course of effect is needed to understand fully the utility of ubrogepant for the acute treatment of migraine.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-cep-10.1177_0333102420970523 for Time course of efficacy of ubrogepant for the acute treatment of migraine: Clinical implications by Peter J Goadsby, Andrew M Blumenfeld, Richard B Lipton, David W Dodick, Kavita Kalidas, Aubrey M Adams, Abhijeet Jakate, Chengcheng Liu, Armin Szegedi and Joel M Trugman in Cephalalgia

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-2-cep-10.1177_0333102420970523 for Time course of efficacy of ubrogepant for the acute treatment of migraine: Clinical implications by Peter J Goadsby, Andrew M Blumenfeld, Richard B Lipton, David W Dodick, Kavita Kalidas, Aubrey M Adams, Abhijeet Jakate, Chengcheng Liu, Armin Szegedi and Joel M Trugman in Cephalalgia

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-3-cep-10.1177_0333102420970523 for Time course of efficacy of ubrogepant for the acute treatment of migraine: Clinical implications by Peter J Goadsby, Andrew M Blumenfeld, Richard B Lipton, David W Dodick, Kavita Kalidas, Aubrey M Adams, Abhijeet Jakate, Chengcheng Liu, Armin Szegedi and Joel M Trugman in Cephalalgia

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-4-cep-10.1177_0333102420970523 for Time course of efficacy of ubrogepant for the acute treatment of migraine: Clinical implications by Peter J Goadsby, Andrew M Blumenfeld, Richard B Lipton, David W Dodick, Kavita Kalidas, Aubrey M Adams, Abhijeet Jakate, Chengcheng Liu, Armin Szegedi and Joel M Trugman in Cephalalgia

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-5-cep-10.1177_0333102420970523 for Time course of efficacy of ubrogepant for the acute treatment of migraine: Clinical implications by Peter J Goadsby, Andrew M Blumenfeld, Richard B Lipton, David W Dodick, Kavita Kalidas, Aubrey M Adams, Abhijeet Jakate, Chengcheng Liu, Armin Szegedi and Joel M Trugman in Cephalalgia

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-6-cep-10.1177_0333102420970523 for Time course of efficacy of ubrogepant for the acute treatment of migraine: Clinical implications by Peter J Goadsby, Andrew M Blumenfeld, Richard B Lipton, David W Dodick, Kavita Kalidas, Aubrey M Adams, Abhijeet Jakate, Chengcheng Liu, Armin Szegedi and Joel M Trugman in Cephalalgia

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-7-cep-10.1177_0333102420970523 for Time course of efficacy of ubrogepant for the acute treatment of migraine: Clinical implications by Peter J Goadsby, Andrew M Blumenfeld, Richard B Lipton, David W Dodick, Kavita Kalidas, Aubrey M Adams, Abhijeet Jakate, Chengcheng Liu, Armin Szegedi and Joel M Trugman in Cephalalgia

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-8-cep-10.1177_0333102420970523 for Time course of efficacy of ubrogepant for the acute treatment of migraine: Clinical implications by Peter J Goadsby, Andrew M Blumenfeld, Richard B Lipton, David W Dodick, Kavita Kalidas, Aubrey M Adams, Abhijeet Jakate, Chengcheng Liu, Armin Szegedi and Joel M Trugman in Cephalalgia

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-9-cep-10.1177_0333102420970523 for Time course of efficacy of ubrogepant for the acute treatment of migraine: Clinical implications by Peter J Goadsby, Andrew M Blumenfeld, Richard B Lipton, David W Dodick, Kavita Kalidas, Aubrey M Adams, Abhijeet Jakate, Chengcheng Liu, Armin Szegedi and Joel M Trugman in Cephalalgia

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-10-cep-10.1177_0333102420970523 for Time course of efficacy of ubrogepant for the acute treatment of migraine: Clinical implications by Peter J Goadsby, Andrew M Blumenfeld, Richard B Lipton, David W Dodick, Kavita Kalidas, Aubrey M Adams, Abhijeet Jakate, Chengcheng Liu, Armin Szegedi and Joel M Trugman in Cephalalgia

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the ACHIEVE I and ACHIEVE II trial participants, investigators, and site staff for their participation in these trials and Amy Kuang, PhD, of AbbVie, for medical writing support.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The authors declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: PJG received grants and personal fees from Amgen and Eli Lilly and Company, grant from Celgene, and personal fees from Aeon Biopharma, Alder Biopharmaceuticals, Allergan (now AbbVie), Biohaven Pharmaceuticals Inc., Clexio, ElectroCore LLC, eNeura, Epalex, Impel Neuropharma, MundiPharma, Novartis, Pfizer, Santara Therapuetics, Teva Pharmaceuticals, Trigemina Inc., WL Gore, MedicoLegal work, Up-to-Date, Oxford University Press, Massachusetts Medical Society, and Wolters Kluwer; and a patent magnetic stimulation for headache assigned to eNeura without fee.

AMB received fees from Allergan (now AbbVie), Aeon, Amgen, Alder, Biohaven, Eli Lilly and Company, ElectroCore, Novartis, Revance, Theranica, and Teva Pharmaceuticals.

RBL reports the following conflicts from within the past 48 months: Serves on the editorial boards of Neurology and Cephalalgia and as senior advisor to Headache. He has received research support from the NIH. He also receives support from the Migraine Research Foundation and the National Headache Foundation. He has reviewed for the NIA and NINDS; serves as consultant, advisory board member, or has received grant support or honoraria from Alder, Allergan (now AbbVie), Amgen, Autonomic Technologies, Avanir, Boston Scientific, Dr. Reddy’s, Electrocore, Eli Lilly, eNeura Therapeutics, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Novartis, Teva, and Vedanta. He receives royalties from Wolff’s Headache, 8th Edition, Oxford University Press, 2009, and Informa. He holds stock options in eNeura Therapeutics and Biohaven.

DWD reports consulting: Amgen, Association of Translational Medicine, University Health Network, Daniel Edelman Inc., Autonomic Technologies, Axsome, Aural Analytics, Allergan (now AbbVie), Alder BioPharmaceuticals, Biohaven, Charleston Laboratories, Dr Reddy's Laboratories/Promius, Electrocore LLC, Eli Lilly, eNeura, Neurolief, Novartis, Ipsen, Impel, Satsuma, Supernus, Sun Pharma (India), Theranica, Teva, Vedanta, WL Gore, Nocira, PSL Group Services, University of British Columbia, XoC, Zosano, ZP Opco, Foresite Capital, Oppenheimer; Upjohn (Division of Pfizer), Pieris, Revance, Equinox, Salvia, Amzak Health. CME fees or royalty payments: HealthLogix, Medicom Worldwide, MedLogix Communications, Mednet, Miller Medical, PeerView, WebMD Health/Medscape, Chameleon, Academy for Continued Healthcare Learning, Universal Meeting Management, Haymarket, Global Scientific Communications, Global Life Sciences, Global Access Meetings, UpToDate (Elsevier), Oxford University Press, Cambridge University Press, Wolters Kluwer Health; Stock options: Precon Health, Aural Analytics, Healint, Theranica, Second Opinion/Mobile Health, Epien, GBS/Nocira, Matterhorn/Ontologics, King-Devick Technologies; Consulting without fee: Aural Analytics, Healint, Second Opinion/Mobile Health, Epien; Precon Health, Board of Directors: Epien, Matterhorn/Ontologics, King-Devick Technologies. Patent: 17189376.1-1466:vTitle: Botulinum Toxin Dosage Regimen for Chronic Migraine Prophylaxis without fee; research funding: American Migraine Foundation, US Department of Defense, PCORI, Henry Jackson Foundation; Professional society fees or reimbursement for travel: American Academy of Neurology, American Brain Foundation, American Headache Society, American Migraine Foundation, International Headache Society, Canadian Headache Society.

KK received personal fees from Amgen, Eli Lilly and Company, Allergan (now AbbVie), Novartis, and Theranica.

AMA is a full-time employee and stockholder of AbbVie.

AJ was a full-time employee and stockholder of AbbVie at the time of the trial conduct and drafting of the manuscript.

CL is a full-time employee and stockholder of AbbVie.

AS was a full-time employee and stockholder of AbbVie at the time of the trial conduct and drafting of the manuscript.

JMT is a full-time employee and stockholder of AbbVie.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This analysis was sponsored by Allergan plc (prior to its acquisition by AbbVie).

ORCID iD: Peter J Goadsby https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3260-5904

References

- 1.GBD 2016 Parkinson’s Disease Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of migraine and tension-type headache, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol 2018; 17: 954–976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wells RE, Markowitz SY, Baron EP, et al. Identifying the factors underlying discontinuation of triptans. Headache 2014; 54: 278–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marmura MJ, Silberstein SD, Schwedt TJ. The acute treatment of migraine in adults: The American Headache Society evidence assessment of migraine pharmacotherapies. Headache 2015; 55: 3–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferrari MD, Roon KI, Lipton RB, et al. Oral triptans (serotonin 5-HT(1B/1D) agonists) in acute migraine treatment: A meta-analysis of 53 trials. Lancet 2001; 358: 1668–1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tfelt-Hansen P, Saxena PR, Dahlof C, et al. Ergotamine in the acute treatment of migraine: A review and European consensus. Brain 2000; 123: 9–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goadsby PJ, Dodick DW, Ferrari MD, et al. TRIPSTAR: Prioritizing oral triptan treatment attributes in migraine management. Acta Neurol Scand 2004; 110: 137–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dodick D, Lipton RB, Martin V, et al. Consensus statement: Cardiovascular safety profile of triptans (5-HT agonists) in the acute treatment of migraine. Headache 2004; 44: 414–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diener HC, Limmroth V. Medication-overuse headache: A worldwide problem. Lancet Neurol 2004; 3: 475–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diener HC, Holle D, Solbach K, et al. Medication-overuse headache: Risk factors, pathophysiology and management. Nat Rev Neurol 2016; 12: 575–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lipton RB, Hamelsky SW, Dayno JM. What do patients with migraine want from acute migraine treatment? Headache 2002; 42: 3–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diener HC, Tassorelli C, Dodick DW, et al. Guidelines of the International Headache Society for controlled trials of acute treatment of migraine attacks in adults: Fourth edition. Cephalalgia 2019; 39: 687–710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Migraine: Developing drugs for acute treatment – guidance for industry. 2018.

- 13.Kelman L. Pain characteristics of the acute migraine attack. Headache 2006; 46: 942–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dodick DW, Lipton RB, Ailani J, et al. Ubrogepant for the treatment of migraine. New Eng J Med 2019; 381: 2230–2241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lipton RB, Dodick DW, Ailani J, et al. Effect of ubrogepant vs placebo on pain and the most bothersome associated symptom in the acute treatment of migraine: The ACHIEVE II randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2019; 322: 1887–1898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ailani J, Hutchinson S, Lipton RB, et al. Long-term safety evaluation of ubrogepant for the acute treatment of migraine. Neurology 2019; 92: P2.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dodick DW, Goadsby PJ, Lakkis H, et al. 61st Annual Scientific Meeting American Headache Society® 11–14 July 2019 Pennsylvania Convention Center Philadelphia, PA. Headache 2019; 59: 1–208. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (beta version). Cephalalgia 2013; 33: 629–808. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Li CC, Dockendorf M, Kowalski K, et al. Population PK analyses of ubrogepant (MK-1602), a CGRP receptor antagonist: Enriching in-clinic plasma PK sampling with outpatient dried blood spot sampling. J Clin Pharmacol 2018; 58: 294–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gabrielsson J, Weiner D. Non-compartmental analysis. Methods Mol Biol (Clifton, NJ) 2012; 929: 377–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moore E, Fraley ME, Bell IM, et al. Characterization of ubrogepant: A potent and selective antagonist of the human calcitonin gene-related peptide receptor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2020; 373: 160–166. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Li CC, Vermeersch S, Denney WS, et al. Characterizing the PK/PD relationship for inhibition of capsaicin-induced dermal vasodilatation by MK-3207, an oral calcitonin gene related peptide receptor antagonist. Brit J Clin Pharmacol 2015; 79: 831–837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van der Schueren BJ, de Hoon JN, Vanmolkot FH, et al. Reproducibility of the capsaicin-induced dermal blood flow response as assessed by laser Doppler perfusion imaging. Brit J Clin Pharmacol 2007; 64: 580–590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Hoon J, Van Hecken A, Vandermeulen C, et al. Phase I, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, single-dose, and multiple-dose studies of erenumab in healthy subjects and patients with migraine. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2018; 103: 815–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sun H, Dodick DW, Silberstein S, et al. Safety and efficacy of AMG 334 for prevention of episodic migraine: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Neurol 2016; 15: 382–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lupi C, Benemei S, Guerzoni S, et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of new acute treatments for migraine. Exp Opin Drug Metab Toxicol 2019; 15: 189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Olesen J, Diener HC, Husstedt IW, et al. Calcitonin gene-related peptide receptor antagonist BIBN 4096 BS for the acute treatment of migraine. New Eng J Med 2004; 350: 1104–1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lipton RB, Croop R, Stock EG, et al. Rimegepant, an oral calcitonin gene-related peptide receptor antagonist, for migraine. New Eng J Med 2019; 381: 142–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davies GM, Santanello N, Lipton R. Determinants of patient satisfaction with migraine therapy. Cephalalgia 2000; 20: 554–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pageler L, Diener HC, Pfaffenrath V, et al. Clinical relevance of efficacy endpoints in OTC headache trials. Headache 2009; 49: 646–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bell CF, Foley KA, Barlas S, et al. Time to pain freedom and onset of pain relief with rizatriptan 10 mg and prescription usual-care oral medications in the acute treatment of migraine headaches: a multicenter, prospective, open-label, two-attack, crossover study. Clin Ther 2006; 28: 872–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-cep-10.1177_0333102420970523 for Time course of efficacy of ubrogepant for the acute treatment of migraine: Clinical implications by Peter J Goadsby, Andrew M Blumenfeld, Richard B Lipton, David W Dodick, Kavita Kalidas, Aubrey M Adams, Abhijeet Jakate, Chengcheng Liu, Armin Szegedi and Joel M Trugman in Cephalalgia

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-2-cep-10.1177_0333102420970523 for Time course of efficacy of ubrogepant for the acute treatment of migraine: Clinical implications by Peter J Goadsby, Andrew M Blumenfeld, Richard B Lipton, David W Dodick, Kavita Kalidas, Aubrey M Adams, Abhijeet Jakate, Chengcheng Liu, Armin Szegedi and Joel M Trugman in Cephalalgia

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-3-cep-10.1177_0333102420970523 for Time course of efficacy of ubrogepant for the acute treatment of migraine: Clinical implications by Peter J Goadsby, Andrew M Blumenfeld, Richard B Lipton, David W Dodick, Kavita Kalidas, Aubrey M Adams, Abhijeet Jakate, Chengcheng Liu, Armin Szegedi and Joel M Trugman in Cephalalgia

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-4-cep-10.1177_0333102420970523 for Time course of efficacy of ubrogepant for the acute treatment of migraine: Clinical implications by Peter J Goadsby, Andrew M Blumenfeld, Richard B Lipton, David W Dodick, Kavita Kalidas, Aubrey M Adams, Abhijeet Jakate, Chengcheng Liu, Armin Szegedi and Joel M Trugman in Cephalalgia

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-5-cep-10.1177_0333102420970523 for Time course of efficacy of ubrogepant for the acute treatment of migraine: Clinical implications by Peter J Goadsby, Andrew M Blumenfeld, Richard B Lipton, David W Dodick, Kavita Kalidas, Aubrey M Adams, Abhijeet Jakate, Chengcheng Liu, Armin Szegedi and Joel M Trugman in Cephalalgia

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-6-cep-10.1177_0333102420970523 for Time course of efficacy of ubrogepant for the acute treatment of migraine: Clinical implications by Peter J Goadsby, Andrew M Blumenfeld, Richard B Lipton, David W Dodick, Kavita Kalidas, Aubrey M Adams, Abhijeet Jakate, Chengcheng Liu, Armin Szegedi and Joel M Trugman in Cephalalgia

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-7-cep-10.1177_0333102420970523 for Time course of efficacy of ubrogepant for the acute treatment of migraine: Clinical implications by Peter J Goadsby, Andrew M Blumenfeld, Richard B Lipton, David W Dodick, Kavita Kalidas, Aubrey M Adams, Abhijeet Jakate, Chengcheng Liu, Armin Szegedi and Joel M Trugman in Cephalalgia

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-8-cep-10.1177_0333102420970523 for Time course of efficacy of ubrogepant for the acute treatment of migraine: Clinical implications by Peter J Goadsby, Andrew M Blumenfeld, Richard B Lipton, David W Dodick, Kavita Kalidas, Aubrey M Adams, Abhijeet Jakate, Chengcheng Liu, Armin Szegedi and Joel M Trugman in Cephalalgia

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-9-cep-10.1177_0333102420970523 for Time course of efficacy of ubrogepant for the acute treatment of migraine: Clinical implications by Peter J Goadsby, Andrew M Blumenfeld, Richard B Lipton, David W Dodick, Kavita Kalidas, Aubrey M Adams, Abhijeet Jakate, Chengcheng Liu, Armin Szegedi and Joel M Trugman in Cephalalgia

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-10-cep-10.1177_0333102420970523 for Time course of efficacy of ubrogepant for the acute treatment of migraine: Clinical implications by Peter J Goadsby, Andrew M Blumenfeld, Richard B Lipton, David W Dodick, Kavita Kalidas, Aubrey M Adams, Abhijeet Jakate, Chengcheng Liu, Armin Szegedi and Joel M Trugman in Cephalalgia