Abstract

Protozoan parasites acquire essential ions, nutrients and other solutes from their insect and vertebrate hosts by transmembrane uptake. For intracellular stages, these solutes must cross additional membranous barriers. At each step, ion channels and transporters mediate not only this uptake, but also the removal of waste products. These transport proteins are best isolated and studied with patch-clamp, but these methods remain accessible to only a few parasitologists due to specialized instrumentation and the required training into both theory and practice. Here, we provide an overview of patch-clamp, describing the advantages and limitations of the technology and highlighting issues that may lead to incorrect conclusions. We aim to help non-experts understand and critically assess patch-clamp data in basic research studies.

Keywords: parasite, membrane transport, ion channel, transporter, patch-clamp, antimalarial drug discovery

Parasite channels and transporters serve essential functions and are important drug targets

Single-celled parasites cause human morbidity and mortality through bloodstream infections and remain important global health problems. Disease burden may be exacerbated in the future by acquired resistance to approved antiparasitic drugs and insecticides. Partly because vaccines against parasites have proven to be less effective than those that target bacteria and viruses [1], identification and characterization of novel parasite drug targets is a pressing need [2,3].

Ion channels and transporters, collectively referred to as transport proteins, represent an important class of unexploited parasite drug targets. These two types of enzymes have important differences (Box 1), but both typically consist of proteins embedded in biological membranes to allow solute passage across otherwise impermeable lipid bilayers. Plasmodium spp. and other parasites rely heavily on transport proteins for growth and survival in host plasma during bloodstream infections (Figure 1). These proteins are even more critical during intracellular parasite stages because there are multiple membrane barriers that solutes must cross. Parasite ion channels and transporters serve a range of essential functions including acquisition of nutrients and essential ions [4–6], waste and metabolite elimination [7], protein translocation [8,9], regulation of cell ion content including transient changes used for intracellular signaling [10–14], volume regulation [15–17], drug extrusion to mediate acquired resistance [18], immune evasion [19], and formation of ion gradients across membranes to produce a membrane potential (see Glossary) and chemical energy [10,20,21].

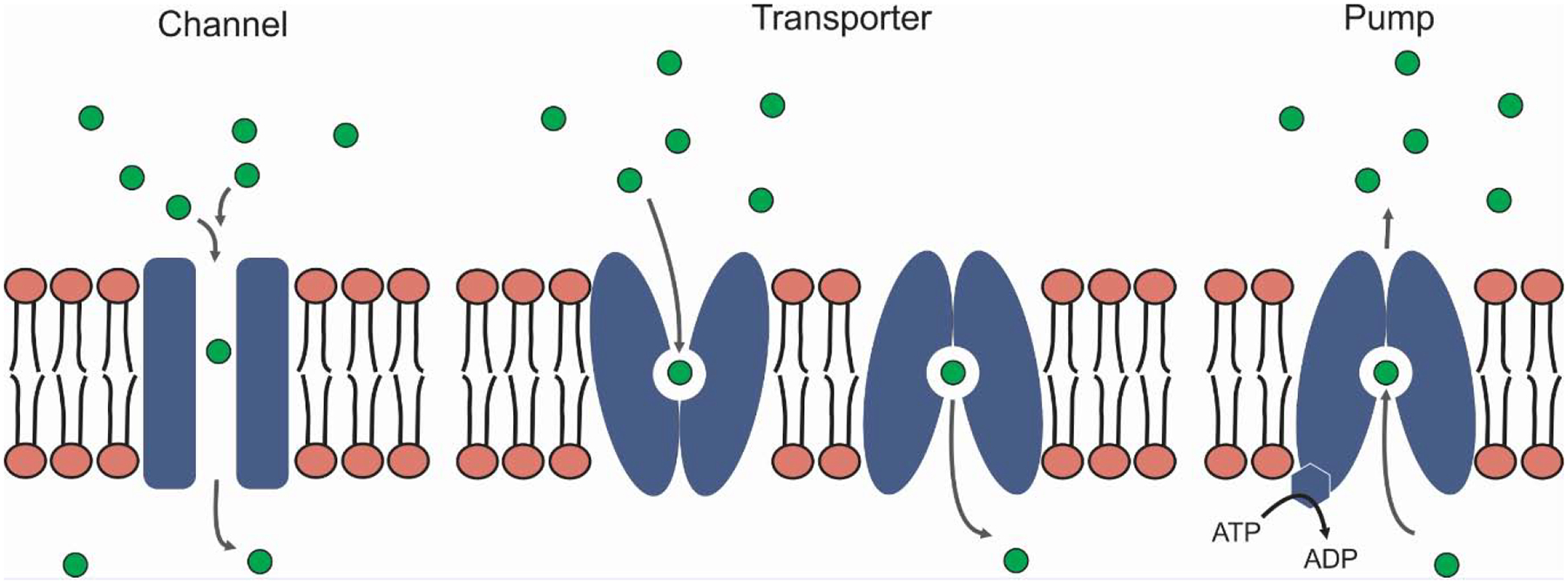

Box 1. Categories of transport proteins: ion channels, transporters, and pumps.

Transport proteins can be subdivided into ion channels, transporters (also referred to as carriers or permeases), and pumps. Ion channels can be modeled as water-filled pores that span the membrane to allow rapid diffusion of solutes in both directions (Figure I). Though channels may produce very high flux rates (106‒1010 ions/s), permeating ions often require interaction with one or more sites in the pore to allow recognition by the channel’s selectivity filter and passage. Diffusion through channel pores is necessarily passive, so net movement is only down the solute’s electrochemical gradient.

The defining feature of transporters is that they are accessible to specific solutes at only one membrane face at a time; this “alternating access” is achieved through conformational changes in the transporter protein with each cycle of transport (Figure I). Because these changes take time, the rate of solute translocation is necessarily slower (≤ 103/s). Like ion channels, transporters allow solute transport in both directions and may also be passive. However, alternating access can allow coupled movement of two or more solutes. For example, the Na+-glucose cotransporter allows cells to absorb glucose at higher levels by coupling uptake to the inward Na+ gradient; this coupling also stimulates water uptake and is critical to the success of oral rehydration therapy for cholera [93]. Parasites also appear to use cotransporters to couple nutrient uptake to ion gradients, allowing them to meet their metabolic needs [94–96].

Pumps represent a special type of transporter; they retain the alternating access constraint and utilize chemical energy (e.g. from ATP hydrolysis) to drive uphill movement of specific solutes. As ATP hydrolysis also requires protein conformational changes, pumps have amongst the lowest transport rates of all membrane transport proteins (< 200 cycles/s). Importantly, these differences in transport rates and capacity for solute coupling have driven the evolution of these divergent transport mechanisms. Cells therefore need both channels and transporters. Although channels and transporters are conveniently modeled as rigid pores and flip-flopping proteins respectively, recent biochemical and structural studies suggest that the differences are more subtle [97].

Figure I (in Box 1).

Types of transport proteins.

Figure 1. Key parasite transport activities identified and characterized with patch-clamp.

In Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes, patch-clamp identified the ion and nutrient-permeable PSAC ①[4,24], a low-copy number Ca++ channel at the host membrane ②[23], and a large conductance, non-selective channel at the PVM ③[46–48,82]. In Toxoplasma gondii, capacitance measurements have implicated invagination of the host membrane as the primary source of lipids for PVM formation ④[99]; patch-clamp has also provided a molecular candidate for a large conductance pore at the PVM ⑤[6] and confirmed previous dye uptake studies [41]. Babesia-infected erythrocytes have increased permeabilities that suggest low-conductance channels ⑥[5], which may be linked to exported parasite proteins [100]. In Trypanosoma spp., two different plasma membrane K+ channels have been identified after reconstitution into giant liposomes ⑦[13]; Ca++ channels at the plasma membrane ➇ and on acidocalcisomes ⑨ have also been supported with electrical measurements [14,84]. Channels at the Leishmania promastigote and amastigote plasma membranes have been studied through heterologous expression ⑩⑫; channels at the PVM of Leishmania-infected macrophages have been identified by direct patch-clamp of the large intracellular vacuole ⑪[17]. In each cartoon, membranes that presumably carry yet unidentified parasite-specific channels are included; organelles not shown, e.g. endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondrion, also have essential membrane transport activities, based on studies in other organisms. RBC, red blood cell; PVM, parasitophorous vacuolar membrane; PPM, parasite plasma membrane, Nuc, nucleus; Api, apicoplast; DV, digestive vacuole; Mic, microneme; SB, spherical body; Kin, kinetoplast.

Identification and characterization of unusual and parasite-specific channels and transporters is critical to our understanding of pathogen biology. For example, the P. falciparum genome lacks clear orthologs of known Cl−, Na+, and Ca++ channels and has only two K+ channel orthologs even though these ions mediate specific cellular activities and are required for in vitro parasite cultivation [11,22,23]. This and other protozoan parasites appear to have evolved novel transport proteins that often evade detection by computational analyses [6,9,12,24]. Moreover, the extraordinary properties of parasite-specific transporters can provide a fresh perspective into how ion channels work. For example, studies of the plasmodial surface anion channel (PSAC) at the host membrane of Plasmodium-infected cells have revealed an unprecedented combination of broad selectivity for diverse solutes and stringent Na+ exclusion [4,25]. This unusual combination appears to have evolved to meet the parasite’s need to acquire nutrients without excess Na+ uptake, which would cause osmotic lysis of its host erythrocyte. Study of PSAC and other unusual parasite channels can, therefore, provide a deeper understanding of how ion channels pass specified solutes with high selectivity.

Parasite channels and transporters are also important targets for new therapies. Human channels and transporters have proven to be outstanding therapeutic targets, with more than 18% of all approved drugs acting directly on transport proteins [26,27]. While channels and transporters remain largely unexploited targets in parasitic diseases, technological advances in transport measurements and improved inhibitor screens should enable development of new and effective drugs against these pathogens [28–33].

Acquired resistance against many antiparasitic drugs is also mediated by transport proteins, with reduced uptake or active extrusion of unmodified drugs a recurring mechanism of action [34–38]. A clearer understanding of how parasite transport proteins alter drug uptake and efflux while maintaining their essential physiological roles may lead to new therapies that subvert acquired resistance.

Despite broad availability and use of tracer flux, osmotic fragility, and fluorescent indicator assays for studying solute transport in parasites [12,39–43], these methods are limited to macroscopic measurements on populations of cells, hindering rigorous mechanistic insights and therapy development. Patch-clamp can address this and other limitations as it measures ion flow on single cells and, under specific conditions, through single ion channel molecules. Here, we review patch-clamp methods and their application to parasitology research. We emphasize the strengths and limitations of this technology and provide general guidelines for use. We aim to make these methods broadly comprehensible so parasitologists with diverse areas of expertise can understand and critically evaluate patch-clamp data.

Key advantages of patch-clamp

Patch-clamp methods offer several fundamental advantages and limitations when compared to traditional, macroscopic transport method like tracer flux. Here, beginning with the major advantages, we list these and provide examples of how they affect the achievable insights into parasite biology.

Ability to delimit measured transport to a specific membrane

Patch-clamp measures ion transport across a single membrane because it directly attaches a glass pipette to a small piece of lipid membrane (the “patch”) on a cell or organelle. The cell and region for study are selected visually in a microscope. A pipette is then filled with salt solution and brought into contact with the chosen membrane using micromanipulators. With luck, this contact yields a tight seal (a “gigaseal”) between the pipette tip and the underlying bilayer [44]. Although how gigaseals form remains poorly understood, calculations based on leak currents reveal that the separation between glass and membrane is measured in angstroms, indicative of a chemical reaction to form a covalent bond along the entire pipette tip circumference. Under these circumstances, the measured currents reflect ion transport across the small patch of membrane under the tip because the pipette functions as an insulator. Depending on the specific configuration used (Box 2), we can measure ion flow through individual channel molecules or across the entire surface membrane in real time. Based on the geometry of pipettes fabricated and used in our laboratory, the membrane patch may be as small as 0.1 μm2. When compared to the mean surface area of a human erythrocyte of 136 μm2, the area of our patch under study corresponds to about 1/1,000th of the cell’s surface.

Box 2. Distinct patch-clamp configurations.

Patch-clamp methods can be used in several different ways to study membrane transport on a single cell or organelle. When a pipette is first sealed on a biological membrane, the “cell-attached” configuration is obtained (Figure I). This configuration measures ion flow across the membrane patch under the pipette and is generally used to obtain single-channel recordings. Here, the exterior channel face is exposed to a defined pipette solution while the inner face is bathed in native cell cytosol. From this configuration, the “whole-cell” configuration can be obtained by mechanical suction or high voltage pulses to disrupt the membrane under the pipette. Whole-cell recordings measure the current across the entire surface membrane, which corresponds to the net flow of ions through channels and transporters on this membrane. For relatively small cells, the cell cytosol is quickly replaced by the pipette solution in this configuration; the “perforated-patch” variant uses pore-forming antibiotics added to the pipette solution to achieve effective whole-cell measurements without full replacement of the cell cytosol (not illustrated, [98]).

Two additional variants of the cell-attached configuration are used for single-channel recordings while allowing greater experimental manipulation of the solution at one or the other channel face [90]. In the “inside-out” recording configuration, the pipette is quickly pulled away from the cell or briefly exposed to air to separate the membrane patch from the rest of the cell. This configuration exposes the cytoplasmic or inner channel surface, which can then be selectively exposed to inhibitors or candidate modulators through perfusion. The “outside-out” recording configuration is similar but permits perfusion at the outer channel surface; this configuration is achieved by slowing withdrawing the pipette from a stationary cell clamped in the whole-cell configuration. These variant single-channel recording configurations are more difficult to obtain for small free-floating cells such as Plasmodium-infected erythrocytes.

Figure I (in Box 2).

Common patch-clamp configurations.

Why is restricting ion transport measurements to a small membrane patch so powerful and informative? Nutrient uptake studies in Plasmodium-infected erythrocytes provide a prime example of why this advantage can be transformative. Although increased solute uptake by infected cells was already well-established through tracer flux and osmotic fragility studies performed over many decades [39,45], the site of this transport activity remained uncertain because endocytosis and a debated parasitophorous duct could also have yielded this uptake without changes at the host erythrocyte membrane [42,43]. Only by isolating the host membrane with patch-clamp was it possible to definitively establish the site of transport and define an ion channel mechanism [4].

Confident isolation of a single membrane is also important when working with incompletely enriched cell populations. In macroscopic uptake measurements, contaminating leukocytes or organelles from lysed cells may accumulate tracer at rates higher than the cells of interest. These contaminants may therefore drastically alter permeability estimates or yield mixed transport properties that may be erroneously attributed to the cells of interest. While filtration or centrifugation may reduce these unwanted contaminants, these procedures are never perfect. Macroscopic tracer or indicator studies are therefore forced to make tenuous assumptions about transport contributions from relevant vs. contaminating membranes. Patch-clamp avoids this problem entirely through microscope-guided selection of a single cell for isolated transport measurements.

As another example of precise targeting of a single membrane, patch-clamp of the parasitophorous vacuolar membrane (PVM) is not complicated by the closely apposed parasite plasma membrane (PPM, Figure 1). Patch-clamp allows us to isolate the PVM because the vacuolar contents provide a low-resistance path for exit currents and bypasses transport at the PPM. With this advantage in mind, single-channel recordings on this membrane identified the PVM channel [46], which functions as a molecular sieve at the outer of two barriers between the parasite and erythrocyte cytosol. These studies provided an early understanding of solute uptake from the host cell [47]; this channel has also been linked to the Plasmodium translocon of exported proteins (PTEX) and appears to have a functional ortholog in intracellular Toxoplasma gondii parasites [6,41,48]. The current model of PVM biology has therefore been shaped, in large measure, by the ability to isolate a single membrane with patch-clamp.

Ability to identify the unitary molecular mechanism of transport

In contrast to macroscopic assays, patch-clamp can measure ion flow through single ion channel molecules present in the membrane patch through the use of sensitive instrumentation that can record picoampere currents.

How do we know that the measured current reflects flow through a single ion channel molecule? Ion channels undergo conformational changes that correspond to “open” and “closed” states of the pore (Figures 2A and 2B). When the pore is open, ions flow through the channel, constrained by driving forces acting on the ions and limitations imposed by the pore. Opening and closing is generally a stochastic process, driven by the internal kinetic energy of the channel protein, but it may also be regulated by specific ligands (so called “ligand-gated channels”), membrane potential (“voltage-dependent channels”), or membrane tension (“mechanosensitive channels”). In either case, transitions between open and closed states produce discrete, real-time changes in measured current (Figures 2C and 2D). Discrete and reproducible transitions between two states can only be seen with single ion channel molecules; a greater number of observed levels would implicate a corresponding increase in the number of functional channels in the membrane patch (Figure 2C). As a notable exception to this rule, some channels exhibit multiple, intermediate rates of ion flow, so-called “subconductance” states that be distinguished through careful analysis.

Figure 2. Broad range of ion channel types and properties.

(A) Common mechanisms used to regulate flow rates through channels. Ion channels with high conductances (flow rates) may have larger pores (top row, flow rates indicated by number of arrows). They may, instead, use charged residues to attract or repel permeating ions and alter conductance (electrostatics). Anions are shown attracted to and concentrated at a channel with a positively charged pore mouth, increasing flow; these charge effects also apply to cations, but with reversed sign. As other options, channels may use ion-ion repulsion within a narrow pore to increase flow, as observed in K+ channels (ion-ion interactions). Relatively high affinity binding sites for permeating ions may increase residence in the pore and reduce conductance (ion-pore interactions). (B) Common gating mechanisms. Ion channels may have a mobile gate that occludes the pore (closed); such gates may be present at any site along the pore. Larger conformational changes such as twisting helices could also lead to pore occlusion. These changes may depend on physiological modulators or ligands that bind at any site on the channel protein. They may also be regulated by membrane voltage or lateral membrane tension (not shown). (C) Cell-attached patch-clamp recordings from P. falciparum-infected erythrocyte membranes. Top trace shows currents associated with a single PSAC molecule. This patch had only one functional channel because there are two observed levels for the measured current: closed (red dotted line) and open (green dotted line). Bottom trace shows a recording from a patch with two functional PSAC molecules, with the red line indicating both channels closed and green lines reflecting either one or both channels open (middle and bottom, respectively). Channel opening amplitudes are identical for these two channels and for the single-channel patch in the top trace. These channels exhibit similar gating, further implicating a single type of channel in these recordings. Both recordings were obtained with identical bath and pipette solutions (1000 mM choline chloride, 115 NaCl, 10 MgCl2, 5 CaCl2, 20 Na-HEPES, pH 7.4) and membrane potential (Vm) of −100 mV; recordings were digitized at 100 kHz and filtered at 5 kHz. The illustrations on the right represent the channel closed and open states. (D) Cell-attached patch-clamp recordings on the P. falciparum-infected erythrocyte membrane and the PVM (top and bottom traces, respectively), showing single PSAC and PVM channel activities under identical recording conditions (bath and pipette solutions as in panel C) and Vm of +40 mV. Closed channel levels are indicated with flanking red dashes; opening events are upgoing at this Vm. Notice that the PVM channel exhibits different gating and larger current transitions; PSAC opening events are less frequent at this voltage, are difficult to resolve at this scaling, and are marked with arrows. While axes and labels are shown in panel C, panel D shows a more conventional scale bar at bottom right.

Because channel proteins have defined sequences and structure in the membrane, these single molecule recordings have highly reproducible properties for a given ion channel type (Figure 2). Just as height, eye color, shape of face, etc. uniquely identify a person, the rate of ion movement through a channel (termed “conductance”), the frequency and duration of openings and closings (“gating”), voltage-dependence, and other features represent unique functional signatures of each ion channel type. Consideration of these features readily distinguishes PSAC and PVM channel properties at the host and parasitophorous vacuolar membranes (Figure 2D). The level of reproducibility possible with single molecule measurements is a critical, defining property of patch-clamp.

As a consequence, patch-clamp can exclude membrane defects such as unstable holes in the lipid bilayer because they do not produce reproducible transport activity. Furthermore, the magnitude of ionic currents in these unitary measurements distinguishes channels from transporters (Box 1), which generally do not produce the relatively large currents required for single molecule recordings. Finally, patch-clamp methods can determine how many types of ion channels are needed to account for observed transport. Again, the infected erythrocyte host membrane provides a prime example because macroscopic measurements led to complicated proposals of multiple channels, transporters, and/or membrane defects before introduction of patch-clamp. While some studies still favor upregulation of multiple channel types [49–51], highly specific inhibitors, channel mutants, and DNA transfection studies of channel subunits have validated the model of a single broad-selectivity, parasite-encoded channel [24,29,52–55]. In converse, studies on some other parasite membranes have revealed that multiple distinct channels are used to transport specific ions [13,17].

Mechanistic insights possible only with single-molecule and single-cell measurements

Patch-clamp can provide unparalleled information about how channels work. The term “permeation” encompasses the step-by-step process of ion movement through a pore and is, ideally, based on a known atomic structure of the channel protein. The following mechanistic insights are possible only with patch-clamp.

Single-channel “conductance” quantifies the rate of ion passage through a channel and is proportional to the increase in current when the channel opens (Figure 2A). Some channels appear to violate the generally recognized biochemical trade-off between an enzyme’s reaction rate and its substrate specificity: the BK (big potassium) channel is highly specific for K+ and yet has a very large conductance, limited only by K+ diffusion to the pore mouth [56]. It achieves this remarkable feat by combining an optimally-designed binding pocket for quickly distinguishing K+ from other cations and charge-charge repulsion between K+ ions to propel ions single-file through the pore [57]. At the other end of the spectrum, PSAC’s small single-channel conductance is equally remarkable when one considers that this channel can pass a broad collection of bulky solutes [4,58]. This small conductance contradicts the assumption that large solutes can only pass through large pores with high conductances [59]. This unusual finding suggests one or more rate-limiting steps in passage through the PSAC pore. Without direct measurement of flow through individual channel molecules, we would be unaware of these complexities in permeation and unable to study how ions interact with pore-lining residues during their transit.

Another feature of single-channel recordings is that they allow us to follow channel openings and closings in real time. This behavior, known as “gating”, reflects conformational changes in the channel protein and can provide important structure-function insights (Figure 2B). Some channels open only at certain voltages or under membrane tension, providing clues into the channel’s physiological role(s) [60,61]. Complex gating, such as rapid flickering between open or closed states under certain experimental conditions, may uncover channel blockers or modulators [62]; channel “run-down”, the loss of activity upon continued recording, may also reflect depletion of a soluble modulator. Single-channel recordings obtained with an added inhibitor can define whether the chemical plugs the pore directly (“a pore blocker”) or works via an allosteric mechanism at a remote site on the channel protein [63,64], a distinction with clear implications for therapy development. Gating analysis may also suggest multi-barreled pores and lead to improved models of channel structure and function [65,66].

Patch-clamp methods also provide an unparalleled opportunity to examine the voltage-dependence of transport proteins because the experimentalist can impose different membrane potentials and measure ion flow through the channel at each voltage. Changes in membrane potential produce a straightforward driving force for ion movement and, more interestingly, may alter the behavior of the channel protein because its charged amino acids are also affected by the imposed electric field. Because these charged amino acids may determine the channel’s ion selectivity or govern channel gating, the ability to make sequential measurements at a range of voltages can provide critical information about the channel.

Greater temporal and spatial control of experiments

Patch-clamp instrumentation can measure small electrical currents with a temporal resolution under one millisecond, yielding kinetic information unavailable with any other transport method. As one example, sub-millisecond resolution permits detection of rapid changes in response to addition of ligands or modulators. Transient responses in ion channel activity and subsequent inactivation occurring over milliseconds can be faithfully tracked. Fast, sensitive measurements are always necessary for detecting gating charges, which reflect movement, not of ions, but of charged residues on a channel protein to open the pore [67].

Another key advantage is that we can select the precise composition of solutions at each membrane face of the channel, at least in some patch-clamp configurations (Box 2). By choosing “bath” and “pipette” solutions that differ from one another, we can quantify the relative flow of candidate ions moving in opposite directions through the pore and assess the channel’s ability to distinguish amongst ions, referred to as its “selectivity”. Such selectivity studies are often too damaging to perform on intact cells in tracer accumulation experiments because many desired solutions (e.g. high K+ or Ca++ concentrations) may trigger apoptosis. With patch-clamp, these concerns are largely eliminated as the membrane patch can be excised for the isolated study of individual channel molecules in a desired nonphysiological solution. Additionally, electronically-controlled, small-volume perfusion setups have enabled measurement of instantaneous channel response to application of ligands, modulators, or inhibitors, providing unparalleled kinetic data [68].

The combined use of multiple available patch-clamp configurations can provide additional useful information (Box 2). For example, comparison of properties in single-channel and whole-cell recordings can quantify a specific channel’s precise contribution to the cell’s total permeability [4]; it can also accurately estimate the number of functional channel molecules/cell. While some of the configurations in Box 2 have not yet been reported in parasite patch-clamp studies, persistence and creative problem-solving may help capture more of patch-clamp’s promises.

Key limitations of patch-clamp

Patch-clamp methods have a distinct set of limitations that should be carefully considered; these limitations can help determine when other methods may be more suitable for specific questions.

Required expertise and cost

Although patch-clamp of small cells such as human erythrocytes is often described as technically difficult [69], diligent practice under the guidance of an experienced supervisor is usually rewarded. In contrast to questions we have received from colleagues, technical mastery of patch-clamp does not require steady hands.

A more daunting challenge is the conceptual expertise needed for design, execution, and interpretation of patch-clamp recordings. To be successful, practitioners must understand basic electrical circuit theory to assure that systematic errors are not introduced and obtain low-noise recordings that reflect biology [70]. Maintaining a good patch-clamp rig requires regular troubleshooting based on circuit theory as several components must be regularly cleaned and adjusted to minimize noise. Experimental errors such as unwanted voltage dividers or inappropriate sampling and filter frequencies should be understood and addressed. Unfortunately, data can still be acquired if these errors are neglected; in this case, serious flaws in interpretation may go unrecognized. In addition to electrical circuit design, the researcher must also have a working knowledge of transport protein structure and function, rooted in a rich history of electrophysiological research. While much of the relevant classical research was performed on K+ and Na+ channels on excitable cells (e.g. neurons and muscle), the foundations laid provide a critical framework for models of transmembrane transport in P. falciparum and other pathogens.

The cost of required instrumentation and software may also have limited broad use of patch-clamp in parasitology. Typically, the required components must be purchased by an individual laboratory because, unlike confocal microscopes and ultracentrifuges, they are not considered shared equipment to be purchased by departmental funds. There is a substantial upfront expense for required hardware: pipette puller, microforge, amplifier, digitizer, microscope, vibration isolation table, manipulators, etc. [71]. Software for data acquisition and analysis is also an upfront cost. Fortunately, after this initial investment, the costs associated with patch-clamp experiments are generally lower than those for radioisotope or fluorescent dye uptake experiments. With care and regular maintenance, a patch-clamp rig can be used for decades. The cost should therefore not be considered a serious limitation for basic molecular and cellular biology laboratories.

Transport activities not easily measured with patch-clamp

Because patch-clamp measures electrical currents resulting from net ion flow across membranes, these methods cannot be used to directly measure the transport of uncharged solutes such as sugars or zwitterionic amino acids that lack a net charge. As it quantifies net movement of charge, patch-clamp is also unable to measure transport via electroneutral exchangers such as a 1:1 Na+/H+ exchange or 1:2 Ca++/Na+ exchange [72,73]. Notable, creative exceptions include the detection and tracking of uncharged solutes through either their osmotic effects or their ability to compete with ions for space in the pore [74]. For example, competition between uncharged polyethylene glycols and ions provided a working estimate of the PVM channel pore size in P. falciparum [47].

Even if transport produces a net movement of charged ions, the rate must be high enough to produce currents greater than the background noise. Electrical noise in patch-clamp recordings is generated by the required instrumentation and by materials that behave as antennae, picking up industrial and other atmospheric interference. Modern patch-clamp amplifiers utilize multiple strategies to reduce instrument noise to very low levels (0.06 to 0.1 pA rms at useful filter frequencies). The materials acting as antennae include the tissue preparation, aqueous solutions, patch-clamp pipette and holder, and the microscope and other hardware. With care, we and others have achieved biological recordings with < 0.15 pA rms noise over a 5 kHz bandwidth [75]. Under these optimal conditions, it is possible to detect somewhat below 1 pA current, which corresponds to the movement of ~ 6 million monovalent ions across the membrane patch each second. Many ion channels, including low conductance channels such as PSAC [58], have transport rates above this threshold, permitting faithful detection of individual channel molecules. Notably, confident PSAC detection required use of molar salt solutions to increase the signal by raising Cl− flux through the channel and reduce background noise by lowering pipette and ground electrode resistances (Figure 2 and supplementary Figure S1)[4]. Nevertheless, transport through some channel proteins remains below the detection threshold. An instructive example is the voltage-gated proton channel [76,77], whose currents are too small to detect in single-channel recordings. These channels have been studied with whole-cell patch-clamp, which sums the currents through the large number of channels on a typical cell (Box 2). One reason for this low conductance is that the H+ concentration in physiological solutions is very low (pH 7.4 ≈ 40 nM H+), which limits the number of ions that can enter the channel pore and be transported each second; physiological Na+ and K+ concentrations (140 mM and 4 mM, respectively in human plasma) are much higher, allowing more straightforward detection of their channels.

Comparatively low throughput and need for reproducibility

Interestingly, a disadvantage of patch-clamp arises from one of its advantages: the ability to measure transport through individual molecules. This one-molecule-at-a-time approach produces a lower experimental throughput than possible with macroscopic measurements like tracer flux. Many membrane patches yield either no channels or multiple active channels, neither of which is suitable for rigorous analysis; it is a random process to find patches that have exactly one functional channel molecule. Depending on cell type and channel properties, it may take days or weeks of working at the patch-clamp rig to get a single-channel recording that answers specific questions about ion permeation or pharmacological properties. As this molecule counts as a single biological replicate, patch-clampers are often forced to think carefully about which questions are worth pursuing. In our studies of unusual parasite channels, we have learned that recordings from multiple channel molecules, acquired one at a time, are usually needed to build reliable models. This low throughput is a critical limitation of patch-clamp. Channels with very low copy numbers on a cell, such as a proposed parasite-induced Ca++ channel on infected erythrocytes [23], are difficult to identify and characterize with patch-clamp because it may take prohibitively long to find and record from several single molecules. Technological advances, such as planar patch-clamp and high-throughput recording systems [78], partially address this limitation by allowing simultaneous measurements from multiple cells and reducing required hands-on time.

Not all membranes are equally accessible

Two technical issues limit the ability to form the required seals on some membranes. First, some membranes are either not accessible to the pipette tip or are too small or deformable for seal formation. To obtain useful data, one must identify the membrane to be targeted and then bring a prepared, filled pipette into direct contact. Although this process is facilitated by micromanipulators, a cell or organelle that is too small to be clearly resolved with available inverted microscope optics cannot be reliably patched. With diligence and appropriate motivation, various groups have successfully patched small or narrow cells such as platelets and neuronal dendrites [79–81]. The membrane must also be directly accessible to the pipette. For example, although the intracellular P. falciparum parasite plasma membrane (PPM) is not prohibitively small, it is covered by the overlying PVM. While we and others have characterized channel activity on the PVM [46–48,82], it has not yet been possible to record from the PPM as it cannot be accessed by the pipette.

Second, once the pipette has been brought into contact with the membrane of interest, we must wait for a poorly understood chemical reaction between the pipette tip and the membrane, as described above. For gigaseal formation, the pipette tip must be kept clean. It cannot be dirtied by prior contact with lipid, dissolved proteins, or some dissolved organic chemicals as these inhibit the desired chemical reaction. We generally pull pipettes and use within the hour; we also prepare protein- and lipid-free salt solutions and filter immediately before use to reduce debris that can dirty the pipette tip. Cells with an extracellular matrix or a thick glycocalyx may require enzyme treatments or other manipulations to facilitate seal formation [83], with the caveat that these treatments may alter the activity of channels under study. Furthermore, some membranes do not readily undergo the desired chemical reaction with the pipette tip. Trial-and-error experimentation with different pipette glass compositions is often required to find one that forms good seals on a new membrane of interest. While this can be challenging, systematic examination often rewards the persistent scientist.

Although size and accessibility appear to limit patch-clamp’s utility, there are several alternatives to direct recordings on intact cells or organelles. One option involves functional reconstitution of purified transport protein or enriched membranes of interest into planar lipid bilayers [47]. A variant of this approach, reconstitution into giant unilamellar vesicles accessible to a traditional patch pipette, has also been used to identify parasite ion channels [13,14]. Another approach uses heterologous expression in more accessible cells [6,84,85]; here, Xenopus oocytes, Sf9 insect cells, and HEK293 cells are favorites choices of electrophysiologists because of facile patch-clamp, low background currents, and a robust capacity for membrane protein expression.

Nonphysiological recording conditions

We often receive questions about interpreting patch-clamp recordings obtained under nonphysiological patch-clamp conditions. In the case of P. falciparum-infected cells, our recordings are obtained in simple salt solutions without serum proteins and lipids because these additives interfere with seal formation. We also often use hypertonic salt solutions to increase detection of single-channel currents, as described above. These solutions may also have higher-than-physiological levels of divalent cations such as Ca++ or Mg++ to facilitate seal formation. When a seal forms, mechanical effects of the pipette or trace ions or minerals that leach from the pipette glass might alter channel behavior. The concerns raised about these nonphysiological recording conditions are legitimate and can only be addressed with multiple control experiments. It is often helpful to confirm the channel’s properties with independent methods, such as a quantitative osmotic lysis assay we developed and have used for independent measurement of solute flux [40]. Concordant results with these independent methods, as well as the new insights gained into PSAC behavior and molecular basis, have reassured us that use of nonphysiological conditions can provide valid results [58,86–88]. Notably, macroscopic assays such as tracer flux, loading with fluorescent dyes, and osmotic fragility methods are also performed under nonphysiological conditions and require appropriate controls.

Critical assessment of patch-clamp data

Because patch-clamp is more challenging for small, deformable cells or organelles such as those associated with apicomplexan parasites, careful design of experiments and interpretation of recordings are essential. While the many advantages of patch-clamp provide strong motivation for use of this technology, the limitations and possible sources of error require critical assessment. We propose the following guidelines for publications that use patch-clamp.

Provide detailed recording conditions

Details of cell preparation, buffers, and applied treatments are important in all biological research, but may more fundamentally alter data acquisition and interpretation in single molecule and single cell recordings. The precise composition of bath and pipette solutions is important not only for evaluating possible effects on cellular activities, but also because the concentrations of ions in these solutions determine the chemical gradients that govern channel-mediated transport. To determine a channel’s ion selectivity, the bath and pipette solutions generally must have different compositions that meet several constraints. Cl− must be present in each solution to produce a low-resistance connection to a Ag:AgCl electrode, but this anion may be excluded if a 3 M KCl-agar bridge is used. When solutions with different compositions are used, errors that result from liquid junction potentials must be considered and specified [89]; if corrections are made for this error, they should be described.

The pipette glass composition, resistance when filled with recording solution, and use of coatings such as silicone elastomers must also be specified [90]. For small cells or membranes that are difficult to patch, it is useful to tally and report success rates. Experimental variables that affect seal formation and detection of channels should be considered and reported to help ensure that the measurements reflect cellular biology. The obtained seal resistances must be reported to help ascertain background noise and durability of the recording, especially when studying small conductance channels [58]; higher seal resistances are always better. Data acquisition sampling rate and filter frequencies are also essential parameters that dictate whether the recording has faithfully captured ion channel gating and other time-variant properties, as governed by the Nyquist sampling theorem [91].

Several other experimental details may be important, depending on the type of recording and interpretations made. Recordings on small cells, such as malaria parasites and infected erythrocytes, are prone to several errors as a result of a relatively high exit resistance, which can exacerbate leak currents and lead to underestimated single-channel conductances [89]. In other systems, these and other errors have led to notoriously flawed conclusions.

Show sufficient unprocessed data

Publications reporting patch-clamp should show enough primary electrical recordings to allow readers to assess data quality and reproducibility, with both the number of traces from separate cells and their durations as important considerations (Figure 2). Because it is possible to select 10–20 milliseconds of recording from many hours of recording to support a favorite hypothesis, quantitative measures of reproducibility are important for avoiding unintentional selection bias. Is the chosen segment of recording representative of the entire recording from that membrane patch? Are the conductance, gating, and voltage-dependence reproducible in multiple patches? Many of these questions can be rigorously quantified through analyses like dwell time analysis of single-channel recordings [92].

We consider it unacceptable to only show a short trace with only a few channel transitions because such events could reflect a mechanical or electrical artifact; multiple consecutive opening and closing events provide more compelling evidence for a gated ion channel. An additional recording from a patch with two functional channels of the same type not only establishes reproducibility but also suggests a reasonably abundant channel (Figure 2C)[4]. Authors can also take advantage of the increased use of supplementary online figures at most journals to show larger datasets and demonstrate unbiased selection of traces. For example, the PSAC recording shown in Figure 2B represents a “zoomed-in” view of 300 ms from 82.1 seconds of recording at −100 mV from a single patch on an infected cell. Supplementary Figure S1 shows nearly this full dataset; data such as these could be added as a supplementary file to confirm that selected traces are representative and to provide more information about channel behavior.

Depending on the channels under study, a range of secondary analyses may be required to support a reliable model of channel behavior or biological role. These may include all-points histograms of raw data, current-voltage relationships, inhibitor dose-response data, kinetic measurements of responses to applied chemicals, gating analyses, noise analysis, and other types of analyses. When performed, a clear description of how data were selected, the details of how the analyses were performed, and measures of statistical significance should all be specified.

Concluding remarks

Patch-clamp methods have been increasingly used to study ion transport in basic parasitology research, yielding fundamental insights into biology and host-pathogen interactions. These methods are more difficult with small deformable cells such as free-living protozoa and human erythrocytes, but consideration of advantages and limitations continues to justify their continued use. When used in combination with other molecular and biochemical technologies, the many remaining questions in parasite transport biology can be addressed (see Outstanding Questions). The recent development of conditional mutant approaches will facilitate molecular studies of essential ion channels and increase the importance of single-channel and single-cell measurements [48,54,82]. The unique biology of these parasites and the unusual ion channels that enable survival within their hosts should attract greater interest and use of patch-clamp methods. Careful consideration of these methods’ strengths and limitations will raise the caliber of parasite transport studies.

Outstanding Questions.

Can additional parasite-encoded channels be identified and characterized using patch-clamp methods? Technological advances may be required to permit study of channels on free-living parasites because of their small size and surface glycocalyx; channels on intracellular membranes such as unique parasite organelles may also be discovered through reconstitution or heterologous expression.

What unique transport activities are expressed at other parasite stages, such as those within insect vectors and solid host organs? Because these activities are not well-characterized, tracer flux and other macroscopic assays should be undertaken to guide patch-clamp.

Parasite channels and transporters found through patch-clamp are often very different from channels in higher organisms. When relevant homologs of known transport proteins are not detected in the parasite genome, can biochemical studies be used to guide identification of the responsible genes?

Do intracellular parasites other than Plasmodium spp. insert ion channels on their host membranes? What role does the resulting increase in host cell permeability serve?

How can the identified ion channels and transporters be prioritized for antiparasitic therapies? Biochemical studies including patch-clamp should be combined with conditional mutant and knockout studies to validate ion channel targets. Will therapies that target parasite-specific channels match the remarkable success of drugs targeting human channels and transporters?

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Ion channels, transporters, and pumps mediate transmembrane movement of ions, nutrients, and drugs in apicomplexan parasites including Plasmodium spp. These proteins represent important, underexploited targets for development of therapies.

Patch-clamp methods have key advantages and limitations when compared to macroscopic transport assays. With proper use, patch-clamp can provide unparalleled insights into the mechanisms and druggability of membrane transport proteins.

Patch-clamp technologies have remained poorly accessible to most parasitologists. We provide a framework for understanding and interpreting patch-clamp data. We also propose guidelines for analysis and presentation of results obtained with these methods.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ryan Kissinger for artwork. This study was supported by the Intramural Research Program of National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Glossary

- Conductance

a measure of flow through an ion channel per unit time. Ion channel conductance is calculated as the open channel current divided by the applied membrane voltage and is typically measured in picosiemens (pS)

- Current

the flow of ions through an open channel. Ion channel currents are typically measured in picoamperes (pA)

- Filter frequency

The cut-off frequency on a low-pass filter used to reduce noise in patch-clamp recordings. This filtering is used to improve detection of ion channel events but improper settings may compromise the desired signal

- Gating

the study of how ion channels open and close. Transitions between the open and closed state may occur stochastically or may depend on a stimulus such as voltage, a soluble ligand, or membrane tension

- Inhibitor

A chemical that prevents transport through an ion channel, either by blocking the pore or by preventing the channel from opening

- Membrane potential (Vm)

difference in electric potential at the two sides of a membrane. For plasma membranes, Vm is defined as potential inside the cell minus the extracellular potential. Membrane potentials, which result from small differences in charge, provide a driving force for ion movement through membrane transport proteins

- Parasitophorous vacuolar membrane (PVM)

A lipid bilayer that surrounds many intracellular apicomplexan parasites. The PVM forms during erythrocyte invasion and is a barrier between the parasite and host cell cytosol

- Patch-clamp pipette

a hollow glass or quartz capillary with a narrow tip. The pipette is filled with a salt solution and sealed on the membrane of interest. Ions that flow through the membrane patch are detected by an electrical amplifier

- Permeation

the step-by-step process of ion or solute diffusion through an ion channel

- Plasmodial surface anion channel (PSAC)

An ion and nutrient uptake channel at the host erythrocyte membrane of Plasmodium-infected cells. PSAC accounts for nearly all increases in host cell permeability and has been linked to RhopH proteins, as expressed by all examined Plasmodium spp

- PVM channel

a large conductance, nonselective ion channel on the PVM of P. falciparum. This channel has been linked to the PTEX protein translocon, but other proteins may also contribute to this activity by unclear mechanisms. A similar channel appears to be present on the T. gondii PVM

- Sampling rate

The frequency at which patch-clamp data are digitized and saved. Based on Nyquist sampling theorem, this rate should be 3–5 times faster than a time-variant signal under study

- Seal resistance

A measure of the quality of the seal between the patch-clamp pipette and the membrane under study, calculated as the ratio of the applied membrane potential to the leak current and typically reported in gigaohms. Higher seal resistances correspond to lower leak currents and improve measurement of channel-mediated transport

- Selectivity

An ion channel’s relative preferences for transporting different ions. Some channels are highly specific for one ion (e.g. a K+ channel) while others allow all solutes smaller than the pore to permeate (e.g. a bacterial porin)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Mutapi F et al. (2013) Infection and treatment immunizations for successful parasite vaccines. Trends Parasitol. 29, 135–141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burrows JN et al. (2013) Designing the next generation of medicines for malaria control and eradication. Malar. J 12, 187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zulfiqar B et al. (2017) Leishmaniasis drug discovery: recent progress and challenges in assay development. Drug Discov. Today 22, 1516–1531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Desai SA et al. (2000) A voltage-dependent channel involved in nutrient uptake by red blood cells infected with the malaria parasite. Nature 406, 1001–1005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alkhalil A et al. (2007) Babesia and plasmodia increase host erythrocyte permeability through distinct mechanisms. Cell Microbiol. 9, 851–860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gold DA et al. (2015) The Toxoplasma dense granule proteins GRA17 and GRA23 mediate the movement of small molecules between the host and the parasitophorous vacuole. Cell Host. Microbe 17, 642–652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Golldack A et al. (2017) Substrate-analogous inhibitors exert antimalarial action by targeting the Plasmodium lactate transporter PfFNT at nanomolar scale. PLoS. Pathog 13, e1006172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Koning-Ward TF et al. (2009) A newly discovered protein export machine in malaria parasites. Nature 459, 945–949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ho CM et al. (2018) Malaria parasite translocon structure and mechanism of effector export. Nature 561, 70–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spillman NJ et al. (2013) Na(+) regulation in the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum involves the cation ATPase PfATP4 and is a target of the spiroindolone antimalarials. Cell Host. Microbe 13, 227–237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pillai AD et al. (2013) Malaria parasites tolerate a broad range of ionic environments and do not require host cation remodeling. Mol. Microbiol 88, 20–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kushwaha AK et al. (2018) Increased Ca(++) uptake by erythrocytes infected with malaria parasites: Evidence for exported proteins and novel inhibitors. Cell Microbiol, 20, e12853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jimenez V et al. (2011) Electrophysiological characterization of potassium conductive pathways in Trypanosoma cruzi. J. Cell Biochem 112, 1093–1102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rodriguez-Duran J et al. (2019) Identification and electrophysiological properties of a sphingosine-dependent plasma membrane Ca(2+) channel in Trypanosoma cruzi. FEBS J. 286, 3909–3925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hansen M et al. (2002) A single, bi-functional aquaglyceroporin in blood-stage Plasmodium falciparum malaria parasites. J. Biol. Chem 277, 4874–4882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lew VL et al. (2003) Excess hemoglobin digestion and the osmotic stability of Plasmodium falciparum-infected red blood cells. Blood 101, 4189–4194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Camacho M (2012) Electrical Membrane Properties in the Model Leishmania-Macrophage. In Patch Clamp Technique (Kaneez FS, ed), IntechOpen. DOI: 10.5772/38075. Available from: https://www.intechopen.com/books/patch-clamp-technique/electrical-membrane-properties-in-the-model-leishmania-macrophage [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wurtz N et al. (2014) Role of Pfmdr1 in in vitro Plasmodium falciparum susceptibility to chloroquine, quinine, monodesethylamodiaquine, mefloquine, lumefantrine, and dihydroartemisinin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 58, 7032–7040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Quintana E et al. (2010) Changes in macrophage membrane properties during early Leishmania amazonensis infection differ from those observed during established infection and are partially explained by phagocytosis. Exp. Parasitol 124, 258–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Allen RJ and Kirk K (2004) The membrane potential of the intraerythrocytic malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. J. Biol. Chem 279, 11264–11272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Balabaskaran NP et al. (2011) ATP synthase complex of Plasmodium falciparum: dimeric assembly in mitochondrial membranes and resistance to genetic disruption. J. Biol. Chem 286, 41312–41322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ellekvist P et al. (2004) Molecular cloning of a K(+) channel from the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 318, 477–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Desai SA et al. (1996) A novel pathway for Ca++ entry into Plasmodium falciparum-infected blood cells. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg 54, 464–470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nguitragool W et al. (2011) Malaria parasite clag3 genes determine channel-mediated nutrient uptake by infected red blood cells. Cell 145, 665–677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cohn JV et al. (2003) Extracellular lysines on the plasmodial surface anion channel involved in Na+ exclusion. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol 132, 27–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Santos R et al. (2017) A comprehensive map of molecular drug targets. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 16, 19–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hutchings CJ et al. (2019) Ion channels as therapeutic antibody targets. MAbs. 11, 265–296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hughes JP et al. (2011) Principles of early drug discovery. Br. J. Pharmacol 162, 1239–1249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pillai AD et al. (2012) Solute restriction reveals an essential role for clag3-associated channels in malaria parasite nutrient acquisition. Mol. Pharmacol 82, 1104–1114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jimenez-Diaz MB et al. (2014) (+)-SJ733, a clinical candidate for malaria that acts through ATP4 to induce rapid host-mediated clearance of Plasmodium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 111, E5455–E5462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heitmeier MR et al. (2019) Identification of druggable small molecule antagonists of the Plasmodium falciparum hexose transporter PfHT and assessment of ligand access to the glucose permeation pathway via FLAG-mediated protein engineering. PLoS One. 14, e0216457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pace DA et al. (2014) Calcium entry in Toxoplasma gondii and its enhancing effect of invasion-linked traits. J. Biol. Chem 289, 19637–19647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Benaim B and Garcia CR (2011) Targeting calcium homeostasis as the therapy of Chagas’ disease and leishmaniasis - a review. Trop. Biomed 28, 471–481 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Basore K et al. (2015) How do antimalarial drugs reach their intracellular targets? Front Pharmacol. 6, 91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ecker A et al. (2012) PfCRT and its role in antimalarial drug resistance. Trends Parasitol. 28, 504–514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Volkman SK et al. (1995) Functional complementation of the ste6 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae with the pfmdr1 gene of Plasmodium falciparum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 92, 8921–8925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Campos MC et al. (2013) P-glycoprotein efflux pump plays an important role in Trypanosoma cruzi drug resistance. Parasitol. Res 112, 2341–2351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leandro C and Campino L (2003) Leishmaniasis: efflux pumps and chemoresistance. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 22, 352–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ginsburg H et al. (1985) Characterization of permeation pathways appearing in the host membrane of Plasmodium falciparum infected red blood cells. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol 14, 313–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wagner MA et al. (2003) A two-compartment model of osmotic lysis in Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes. Biophys. J 84, 116–123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schwab JC et al. (1994) The parasitophorous vacuole membrane surrounding intracellular Toxoplasma gondii functions as a molecular sieve. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 91, 509–513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pouvelle B et al. (1991) Direct access to serum macromolecules by intraerythrocytic malaria parasites. Nature 353, 73–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kirk K et al. (1994) Transport of diverse substrates into malaria-infected erythrocytes via a pathway showing functional characteristics of a chloride channel. J. Biol. Chem 269, 3339–3347 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Suchyna TM et al. (2009) Biophysics and structure of the patch and the gigaseal. Biophys. J 97, 738–747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Overman RR (1948) Reversible cellular permeability alterations in disease. In vivo studies on sodium, potassium and chloride concentrations in erythrocytes of the malarious monkey. Am. J. Physiol 152, 113–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Desai SA et al. (1993) A nutrient-permeable channel on the intraerythrocytic malaria parasite. Nature 362, 643–646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Desai SA and Rosenberg RL (1997) Pore size of the malaria parasite’s nutrient channel. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 94, 2045–2049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Garten M et al. (2018) EXP2 is a nutrient-permeable channel in the vacuolar membrane of Plasmodium and is essential for protein export via PTEX. Nat. Microbiol 3, 1090–1098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Staines HM et al. (2007) Electrophysiological studies of malaria parasite-infected erythrocytes: current status. Int. J Parasitol 37, 475–482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bouyer G et al. (2011) Erythrocyte peripheral type benzodiazepine receptor/voltage-dependent anion channels are upregulated by Plasmodium falciparum. Blood 118, 2305–2312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Akkaya C et al. (2009) The Plasmodium falciparum-induced anion channel of human erythrocytes is an ATP-release pathway. Pflugers Arch. 457, 1035–1047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sharma P et al. (2013) An epigenetic antimalarial resistance mechanism involving parasite genes linked to nutrient uptake. J. Biol. Chem 288, 19429–19440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sharma P et al. (2015) A CLAG3 mutation in an amphipathic transmembrane domain alters malaria parasite nutrient channels and confers leupeptin resistance. Infect. Immun 83, 2566–2574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ito D et al. (2017) An essential dual-function complex mediates erythrocyte invasion and channel-mediated nutrient uptake in malaria parasites. Elife. 6, e23485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gupta A et al. (2020) Complex nutrient channel phenotypes despite Mendelian inheritance in a Plasmodium falciparum genetic cross. PLoS. Pathog 16, e1008363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Latorre R et al. (2017) Molecular determinants of BK channel functional diversity and functioning. Physiol Rev. 97, 39–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhou M and MacKinnon R (2004) A mutant KcsA K(+) channel with altered conduction properties and selectivity filter ion distribution. J. Mol. Biol 338, 839–846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Alkhalil A et al. (2004) Plasmodium falciparum likely encodes the principal anion channel on infected human erythrocytes. Blood 104, 4279–4286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Colombini M (1980) Structure and mode of action of a voltage dependent anion-selective channel (VDAC) located in the outer mitochondrial membrane. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci 341, 552–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Guy HR and Conti F (1990) Pursuing the structure and function of voltage-gated channels. Trends Neurosci. 13, 201–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Booth IR (2014) Bacterial mechanosensitive channels: progress towards an understanding of their roles in cell physiology. Curr. Opin. Microbiol 18, 16–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pusch M et al. (2000) Gating and flickery block differentially affected by rubidium in homomeric KCNQ1 and heteromeric KCNQ1/KCNE1 potassium channels. Biophys. J 78, 211–226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sigworth FJ and Sine SM (1987) Data transformations for improved display and fitting of single-channel dwell time histograms. Biophys. J 52, 1047–1054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhang P et al. (2006) Gating of acid-sensitive ion channel-1: release of Ca2+ block vs. allosteric mechanism. J. Gen. Physiol 127, 109–117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hunter M and Giebisch G (1987) Multi-barrelled K channels in renal tubules. Nature 327, 522–524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kim DM and Nimigean CM (2016) Voltage-gated potassium channels: a structural examination of selectivity and gating. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol 8, a029231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bezanilla F (2018) Gating currents. J. Gen. Physiol 150, 911–932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Brett RS et al. (1986) A method for the rapid exchange of solutions bathing excised membrane patches. Biophys. J 50, 987–992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hamill OP (1983) Potassium and chloride channels in red blood cells. In Single Channel Recording (Sakmann B and Neher E, eds), pp. 451–471, Plenum Press [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sigworth FJ (1995) Electronic design of the patch clamp. In Single-channel recording (Sakmann B and Neher E, eds), pp. 95–127, Springer [Google Scholar]

- 71.Levis RA and Rae JL (1992) Constructing a patch clamp setup. Methods Enzymol. 207, 14–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Semplicini A et al. (1989) Kinetics and stoichiometry of the human red cell Na+/H+ exchanger. J. Membr. Biol 107, 219–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Brand MD (1985) The stoichiometry of the exchange catalysed by the mitochondrial calcium/sodium antiporter. Biochem. J 229, 161–166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nestorovich EM et al. (2002) Designed to penetrate: time-resolved interaction of single antibiotic molecules with bacterial pores. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 99, 9789–9794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Levis RA and Rae JL (1993) The use of quartz patch pipettes for low noise single channel recording. Biophys. J 65, 1666–1677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sasaki M et al. (2006) A voltage sensor-domain protein is a voltage-gated proton channel. Science 312, 589–592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ramsey IS et al. (2006) A voltage-gated proton-selective channel lacking the pore domain. Nature 440, 1213–1216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Obergrussberger A et al. (2020) Automated patch clamp in drug discovery: major breakthroughs and innovation in the last decade. Expert. Opin. Drug Discov, 1–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Maruyama Y (1987) A patch-clamp study of mammalian platelets and their voltage-gated potassium current. J. Physiol 391, 467–485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Usowicz MM et al. (1992) P-type calcium channels in the somata and dendrites of adult cerebellar Purkinje cells. Neuron 9, 1185–1199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Stuart GJ et al. (1993) Patch-clamp recordings from the soma and dendrites of neurons in brain slices using infrared video microscopy. Pflugers Arch. 423, 511–518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mesen-Ramirez P et al. (2019) EXP1 is critical for nutrient uptake across the parasitophorous vacuole membrane of malaria parasites. PLoS Biol. 17, e3000473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Izu YC and Sachs F (1991) Inhibiting synthesis of extracellular matrix improves patch clamp seal formation. Pflugers Arch. 419, 218–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Potapenko E et al. (2019) The acidocalcisome inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor of Trypanosoma brucei is stimulated by luminal polyphosphate hydrolysis products. J. Biol. Chem 294, 10628–10637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Mosimann M et al. (2010) A Trk/HKT-type K+ transporter from Trypanosoma brucei. Eukaryot. Cell 9, 539–546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hill DA et al. (2007) A blasticidin S-resistant Plasmodium falciparum mutant with a defective plasmodial surface anion channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104, 1063–1068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lisk G et al. (2008) Changes in the plasmodial surface anion channel reduce leupeptin uptake and can confer drug resistance in P. falciparum-infected erythrocytes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 52, 2346–2354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lisk G and Desai SA (2005) The plasmodial surface anion channel is functionally conserved in divergent malaria parasites. Eukaryot. Cell 4, 2153–2159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Barry PH and Lynch JW (1991) Liquid junction potentials and small cell effects in patch-clamp analysis. J. Membr. Biol 121, 101–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hamill OP et al. (1981) Improved patch-clamp techniques for high-resolution current recording from cells and cell-free membrane patches. Pflugers Arch. 391, 85–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sachs F and Auerbach A (1983) Single-channel electrophysiology: use of the patch clamp. Methods Enzymol. 103, 147–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Desai SA (2005) Open and closed states of the plasmodial surface anion channel. Nanomedicine 1, 58–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Rao MC (2004) Oral rehydration therapy: new explanations for an old remedy. Annu. Rev. Physiol 66, 385–417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wu B et al. (2015) Identity of a Plasmodium lactate/H(+) symporter structurally unrelated to human transporters. Nat. Commun 6, 6284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Potapenko E et al. (2019) Pyrophosphate stimulates the phosphate-sodium symporter of Trypanosoma brucei acidocalcisomes and Saccharomyces cerevisiae vacuoles. mSphere. 4, e00045–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Singh A and Mandal D (2011) A novel sucrose/H+ symport system and an intracellular sucrase in Leishmania donovani. Int. J. Parasitol 41, 817–826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ashcroft F et al. (2009) Introduction. The blurred boundary between channels and transporters. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond B Biol. Sci 364, 145–147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Horn R and Marty A (1988) Muscarinic activation of ionic currents measured by a new whole-cell recording method. J. Gen. Physiol 92, 145–159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Suss-Toby E et al. (1996) Toxoplasma invasion: the parasitophorous vacuole is formed from host cell plasma membrane and pinches off via a fission pore. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 93, 8413–8418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Hakimi H et al. (2020) Novel Babesia bovis exported proteins that modify properties of infected red blood cells. PLoS Pathog. 16, e1008917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.