Key Points

Question

What are the comparative efficacies and acceptability of psychosocial interventions for the treatment of self-harm and suicidality among children and adolescents?

Findings

In this systematic review and network meta-analysis of pooled data from 44 randomized clinical trials of psychotherapies for children and adolescents that involved 5406 total participants, the investigated psychotherapies were found to be acceptable to patients, but the evidence was inconsistent with regard to self-harm and suicidality measures across therapeutic modalities.

Meaning

The findings indicate that, although some psychotherapeutic modalities appeared to be acceptable and efficacious for reducing self-harm and suicidality among children and adolescents, methodological issues and high risk of bias suggest a need for additional randomized clinical trials.

Abstract

Importance

Self-harm and suicidal behavior are associated with substantial morbidity and mortality among children and adolescents. The comparative performance of psychotherapies for suicidality is unclear because few head-to-head clinical trials have been conducted.

Objective

To compare the efficacy of psychotherapies for the treatment of self-harm and suicidality among children and adolescents.

Data Sources

Four major bibliographic databases (PubMed, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, and Embase) were searched for clinical trials comparing psychotherapy with control conditions from inception to September 2020.

Study Selection

Randomized clinical trials comparing psychotherapies for suicidality and/or self-harm with control conditions among children and adolescents were included after a blinded review by 3 independent reviewers (A.B., M.P., and J.W.).

Data Extraction and Synthesis

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) reporting guideline was followed for data abstraction, and the Cochrane risk of bias tool was used to evaluate study-level risk of bias. Data abstraction was performed by 1 reviewer (A.B.) and confirmed by 2 independent blinded reviewers (J.W. and M.P.). Data were analyzed from October 15, 2020, to February 15, 2021.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcomes were dichotomized self-harm and retention in treatment. The secondary outcomes were dichotomized all-cause treatment discontinuation and scores on instruments measuring suicidal ideation and depressive symptoms. Effect sizes were pooled using frequentist random-effects network meta-analysis models to generate summary odds ratios (ORs) and Cohen d standardized mean differences (SMDs). Negative Cohen d SMDs or ORs less than 1 indicated that the treatment reduced the parameter of interest relative to the control condition (eg, signifying a beneficial association with suicidal ideation).

Results

The systematic search generated 1272 unique records. Of those, 44 randomized clinical trials (5406 total participants; 4109 female participants [76.0%]) from 49 articles were selected (5 follow-up studies were merged with their primary clinical trials to avoid publication bias). The selected clinical trials spanned January 1, 1995, to December 31, 2020. The median duration of treatment was 3 months (range, 0.25-12.00 months), and the median follow-up period was 12 months (range, 1-36 months). None of the investigated psychotherapies were associated with increases in study withdrawals or improvements in retention in treatment compared with treatment as usual. Dialectical behavioral therapies were associated with reductions in self-harm (OR, 0.28; 95% CI, 0.12-0.64) and suicidal ideation (Cohen d SMD, −0.71; 95% CI, −1.19 to −0.23) at the end of treatment, while mentalization-based therapies were associated with decreases in self-harm (OR, 0.38; 95% CI, 0.15-0.97) and suicidal ideation (Cohen d SMD, −1.22; 95% CI, −2.18 to −0.26) at the end of follow-up. The quality of evidence was downgraded because of high risk of bias overall, heterogeneity, publication bias, inconsistency, and imprecision.

Conclusions and Relevance

Although some psychotherapeutic modalities appear to be acceptable and efficacious for reducing self-harm and suicidality among children and adolescents, methodological issues and high risk of bias prevent a consistent estimate of their comparative performance.

This systematic review and network meta-analysis uses pooled data from randomized clinical trials to compare the efficacy and acceptability of psychotherapies for the treatment of self-harm and suicidal behavior among children and adolescents.

Introduction

Over the past 2 decades, there has been an increase in research exploring diverse aspects of self-harm and suicidal behavior among youths.1 Self-harm appears to peak in adolescence,2 with recent global surveys indicating that between 10% and 20% of adolescents reported past-year suicidal ideation and suicide attempts.3 In addition to sex and gender considerations,4 genetic vulnerability and several psychiatric, psychosocial, familial, and cultural factors may mediate suicide risk.5 Substance use, particularly cannabis, has also been implicated as a risk factor for self-harm and mortality risk among young adults.6,7

Despite the advances in research on the prevalence, correlates, classification, and function of self-harm and suicidal behaviors, there has been limited progress in reducing suicide rates for almost 60 years.8,9 Self-harm and suicidality among youths continue to be substantial burdens for patients, families, communities, and health systems.1,10,11,12,13,14 Evidence-based self-harm and suicide prevention efforts aimed at young people are needed.5,15

At present, there are insufficient data from randomized clinical trials (RCTs) to recommend targeted pharmacological treatments for self-harm or suicidal behavior in youths. However, some nonpharmacological interventions, including psychotherapies, appear to improve some aspects of suicidal behavior. Several meta-analyses have synthesized data from RCTs examining psychotherapies for self-harm and suicidality in youth populations. Ougrin et al8 found the largest effect sizes with dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT), cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and mentalization-based therapy (MBT). Nonetheless, they noted a lack of independent replications of efficacy for any intervention.

Hawton et al15 reported preliminary data indicating that MBT may be associated with reductions in self-harm and recommended further evaluation of therapeutic assessment and DBT. However, no evidence was found to indicate that group-based therapies, compliance enhancement, CBT, family-based therapy, or provision of an emergency card was associated with decreases in suicidal behaviors. Robinson et al16 reported no differences between treatment and control groups across 15 RCTs, with the exception of 1 study that compared CBT with treatment as usual. Storebø et al17 found that DBT and MBT had some beneficial consequences for reducing self-harm among individuals with borderline personality disorder (BPD) but noted that these conclusions were based on low-quality evidence. Jørgensen et al18 reported a significant association between DBT and self-harm at the end of treatment compared with control interventions but no association between cognitive analytic therapy or MBT and reductions in self-harm among adolescents with BPD or BPD features compared with treatment as usual, emphasizing the need for more high-quality clinical trials with larger samples.

Kothgassner et al2 found that the pooling of psychological treatments was associated with improvements in self-harm, suicidal ideation, and depressive symptoms compared with active control conditions, with subgroup analyses indicating that DBT and family-based therapy may be associated with decreases in self-harm and suicidal ideation. Previous authors of systematic reviews have cited the small number of RCTs, limited direct comparisons between treatments, low quality of evidence, and lack of independent replication of individual RCT findings as key limitations.2,8 Given the inconsistency across previous reviews, the most appropriate type of psychotherapy for the treatment of adolescents who present with self-harm or suicidality remains unclear.

An alternative approach, termed network meta-analysis (NMA), might alleviate some of these previous challenges, particularly the shortage of head-to-head studies.19,20,21 An NMA is a meta-analysis of multiple treatments that simultaneously compares treatments across direct and indirect evidence sources in a single network.22 Network meta-analysis can be used to pool the samples across many small RCTs to increase the power for detecting differences across outcomes. Network meta-analyses may be preferable to standard meta-analyses in some situations, as the network's indirect comparisons can mitigate study-specific biases that are not identifiable in head-to-head RCTs.22 A network meta-analysis can also incorporate more data into the analysis, allowing researchers to tackle the bigger picture, while a traditional meta-analysis often provides a fragmented view.22 However, the valid application of NMA depends on the satisfaction of several statistical requirements, such as a similar distribution of effect modifiers across clinical trials and comparisons.20 The present NMA aimed to reexamine the comparative efficacy and safety of psychotherapies for the treatment of self-harm and suicidal behaviors among children and adolescents.

Methods

This review was registered with the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/zcwvk) and adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) reporting guideline and its extension for NMAs.23,24

Eligibility Criteria

We used the populations-interventions-comparators-outcomes-study design framework to define review eligibility. We considered RCTs that measured self-harm or suicidal behavior among children or adolescents aged 10 to 19 years. We defined self-harm as any intentional injury to oneself, regardless of suicidal motivation.2 To categorize interventions, we coded therapy protocols using the following groups: brief intervention, cognitive analytic therapy, CBT, DBT, family-based therapy, interpersonal therapy, MBT, mode deactivation therapy, supportive therapy, and short-term psychoanalytic psychotherapy (eTable 1 in the Supplement). Clinical trials blending 3 or more modalities were categorized as eclectic therapies.

To facilitate our analyses, we collapsed some interventions into larger categories. For example, brief motivational interviewing sessions, hospital admission tokens, brief app-based interventions, and youth-nominated support teams were categorized as brief interventions. Subcomponents of established psychotherapy were collapsed into the parent modality (eg, emotion regulation training and mindfulness interventions into DBT), and variants of an established modality were collapsed into the main classification (eg, MBT for adolescents into MBT). We defined nondirective nonspecific interventions as supportive therapy. Therapies were categorized as either individual or group rather than considering group therapy as a separate modality. We considered treatment as usual, enhanced usual care, waitlist control, and active comparators; however, we collapsed enhanced usual care into treatment as usual.

The primary outcomes were self-harm frequency (participants with ≥1 deliberate episodes of self-harm, including suicide attempts and nonsuicidal self-injury) and retention in treatment (participants who completed the primary treatment protocol). Secondary outcomes were study withdrawals (the number of participants who withdrew from the clinical trial for any reason) and suicidal ideation and depression severity, measured using clinician- or self-rated instruments. We excluded nonrandomized designs, crossover RCTs, and studies with missing or unobtainable data.

Search Strategy, Selection, and Data Collection

We developed a comprehensive search strategy in PubMed, MEDLINE, Embase, and PsycINFO from the date of their inception to September 15, 2021 (eTable 2 in the Supplement). Search terms included self-harm, self-injury, suicidal ideation, or suicidal behavior and therapy or intervention. We reviewed the bibliographies of included records and previous reviews to supplement the electronic search.

Our review relied on Covidence, a web-based systematic review manager,25,26 to facilitate study selection by 2 investigators (A.B. and M.P.) who independently screened all records for the eligibility criteria by title and/or abstract and full text. Discrepancies were resolved through consensus.

Three reviewers (A.B., M.P., and J.W.) independently abstracted data and performed quality assessments using a spreadsheet (Microsoft Excel; Microsoft Corp). Extracted variables included sample size, demographic characteristics, intervention characteristics (modality and number of sessions), outcome measures, study name and authors, study location, and treatment duration and follow-up.

Risk of Bias

To evaluate risk of bias within studies, 3 reviewers (A.B., M.P., and J.W.) independently appraised RCT quality using the Cochrane risk of bias tool,27 which assigns a low, high, or unclear rating to 6 domains: randomization, allocation concealment, blinding of participants, blinding of evaluators, incomplete outcome reporting, and selective reporting. We also considered allegiance, adherence, and attention biases.18 Allegiance bias occurs when the developer of a treatment is also an RCT investigator. Adherence bias concerns the fidelity of a treatment to protocol. Attention bias is produced by discrepant therapy doses (ie, sessions) between RCT arms. Overall study-level bias was considered high if any individual domain received a high score or had 2 or more unclear fields.

To assess the risk of bias across studies, we evaluated publication bias by graphing funnel plots28 and applying the Egger test.29 We used Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) guidelines,30 and we downgraded the quality of evidence if we detected a high risk of bias, imprecision in outcomes, or heterogeneity.

Summary Measures and Statistical Analysis

We used Cohen d standardized mean differences (SMDs) and odds ratios (ORs) to summarize effect sizes for continuous and dichotomous variables. Standardized mean differences of 0.2, 0.5, and 0.8 corresponded to small, medium, and large effect sizes.31 Negative Cohen d SMDs or ORs less than 1 indicated that the treatment reduced the parameter of interest relative to the control condition (eg, signifying a beneficial effect for suicidal ideation).31,32

We followed the same analytic approaches used in previous NMAs of studies examining psychiatric disorders (eMethods in the Supplement).33,34,35,36,37,38 We used the RStudio netmeta package, version 3.5.1 (RStudio).39,40 Forest plots were graphed for each outcome measure (self-harm, retention in treatment, study withdrawals, suicidality, and depression), and treatment rankings were created to represent each therapy’s effect size compared with treatment as usual. To preserve randomization, we used frequentist random-effects models, which accommodate different measures for the same outcome (eg, alternative instruments measuring suicidal ideation).41 To maximize available data, outcomes presented as dichotomous were pooled with continuous data using an inverse variance method. We assumed a jointly randomizable network, in which participants were equally likely to be randomized to any of the treatments.21,41,42,43 To determine NMA goodness of fit, transitivity (the extent of network heterogeneity) and consistency (the extent of agreement between direct and indirect comparisons)44 were assessed. To quantify transitivity, τ2 (total variation) and I2 (percentage of τ2 not caused by random error) were measured, with higher values indicating more heterogeneity.45,46 The Cochrane Q statistic was used to evaluate consistency, with the assumption of a full design-by-treatment interaction random-effects model; P > .05 indicated that the model was consistent. Dual analyses were conducted by distinguishing outcomes at the end of treatment from outcomes at the end of follow-up.

Network-level subgroup or meta-regression analyses could not be performed owing to limitations in the currently available RStudio packages. Data were analyzed from October 15, 2020, to February 15, 2021.

Results

Study Selection and Characteristics

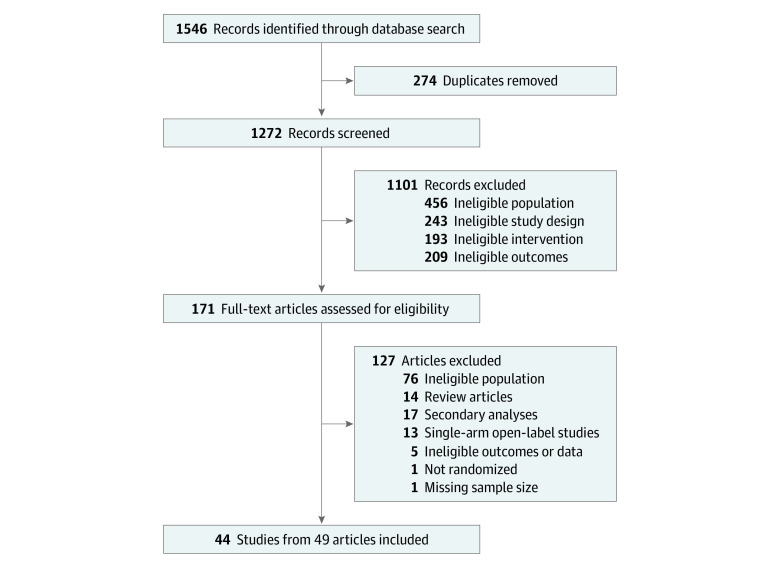

The systematic search identified 1272 unique records (Figure 1). After exclusion of 1101 records for ineligible study population, design, intervention, and/or outcomes, 171 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. Of those, 44 RCTs (5406 total participants; 4109 female participants [76.0%]) from 49 articles were selected. To avoid publication bias, we merged 5 follow-up RCTs47,48,49,50,51 with their primary clinical trials.52,53,54,55

Figure 1. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) Flowchart of Study Selection Process.

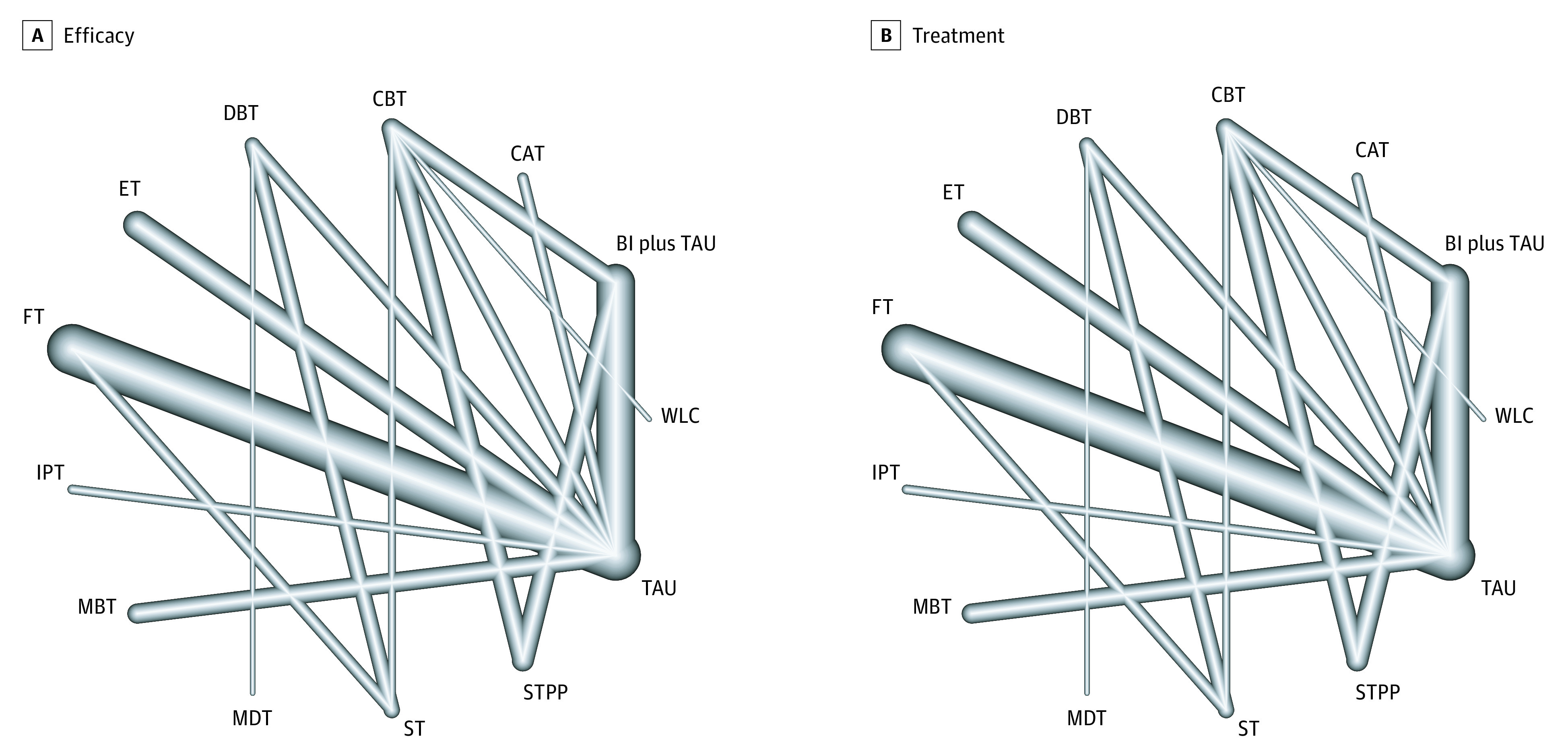

The RCTs included in our review47,48,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95 spanned 1995 to 2020, with most studies conducted in the US (Table 1). With regard to clinical samples, 31 RCTs examined any patient who presented with self-harm behaviors, and 8 RCTs involved adolescents with BPD. The median duration of treatment and follow-up was 3 months (range, 0.25-12.00 months) and 12 months (range, 1-36 months), respectively. Among the 44 RCTs included, 33 studies offered individual psychotherapy, and the most common modalities were brief intervention, family-based therapy, and DBT (Figure 2).

Table 1. Characteristics of Randomized Clinical Trials Included in Network Meta-analysis.

| Source | Treatment group (No. of participants) | Country | Age range, y | Clinical group |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alavi et al,56 2013 | CBT (15) vs WLC (15) | Iran | 12-18 | Depression |

| Apsche et al,57 2006 | Group DBT (10) vs MDT (10) | US | 15-18 | Aggression and conduct |

| Asarnow et al,58 2011 | FT (89) vs EUC (92) | US | 10-18 | Transdiagnostic |

| Asarnow et al,59 2017 | FT (20) vs EUC (22) | US | 12-18 | Transdiagnostic |

| Beck et al,52 2020 and Jørgensen et al,47 2020 | Group MBT (55) vs TAU (56) | Denmark | 14-17 | BPD |

| Britton et al,60 2014 | DBT (52) vs TAU (58) | US | 11-12 | Transdiagnostic |

| Chanen et al,61 2008 | CAT (44) vs GCC (42) | Australia | 15-18 | BPD |

| Cooney et al,62 2010 | DBT (15) vs TAU (15) | New Zealand | 13-19 | Transdiagnostic |

| Cotgrove et al,63 1995 | BI plus TAU (47) vs TAU (58) | UK | 10-16 | Transdiagnostic |

| Cottrell et al,51 2020 and Cottrell et al,53 2018 | FT (415) vs TAU (417) | UK | 11-17 | Transdiagnostic |

| Diamond et al,64 2010 | FT (35) vs EUC (31) | UK | 12-17 | Transdiagnostic |

| Diamond et al,65 2019 | FT (66) vs ST (63) | US | 12-18 | Transdiagnostic |

| Donaldson et al,66 2005 | SBT (15) vs ST (16) | US | 12-17 | Transdiagnostic |

| Esposito-Smythers et al,67 2011 | CBT (20) vs EUC (20) | US | 13-17 | SUD |

| Esposito-Smythers et al,68 2017 | FB-CBT (41) vs AAU (40) | US | 13-18 | SUD |

| Gleeson et al,69 2012 | CAT (8) vs TAU (8) | Australia | 15-25 | BPD plus psychosis |

| Goodyer et al,70 2017 | CBT (155) vs STPP (157) vs BI plus TAU (158) | UK | 11-17 | Depression |

| Green et al,71 2011 | Group ET (183) vs EUC (183) | UK | 12-17 | Transdiagnostic |

| Griffiths et al,72 2019 | Group MBT (26) vs TAU (27) | UK | 12-18 | Transdiagnostic |

| Harrington et al,73 1998 | FT (85) vs TAU (77) | UK | 10-16 | Transdiagnostic |

| Hazell et al,74 2009 | Group ET (35) vs TAU (37) | Australia | 12-16 | Transdiagnostic |

| Hetrick et al,75 2017 | CBT (26) vs TAU (24) | Australia | 13-19 | Transdiagnostic |

| Hill et al,76 2019 | IPT (41) vs TAU (39) | US | 13-19 | Transdiagnostic |

| Kaess et al,77 2020 | CBT plus DBT (37) vs TAU (37) | Multicenter | 12-17 | Transdiagnostic |

| Kennard et al,78 2018 | BI plus TAU (34) vs TAU (32) | US | 12-18 | Transdiagnostic |

| King et al,79 2006 | BI plus TAU (151) vs TAU (138) | US | 12-17 | Transdiagnostic |

| King et al,80 2009 | BI plus TAU (223) vs TAU (225) | US | 13-17 | Transdiagnostic |

| King et al,81 2015 | MI (27) vs EUC (22) | US | 14-19 | Transdiagnostic |

| McCauley et al,82 2018 | Group DBT (86) vs ST (87) | US | 12-18 | BPD |

| Mehlum et al,48 2016 and Mehlum et al,54 2014 | Group DBT (39) vs EUC (38) | Norway | 12-18 | BPD |

| Ougrin et al,50 2013 and Ougrin et al55 2011 | BI plus TAU (35) vs TAU (35) | Norway | 12-18 | Transdiagnostic |

| Ougrin et al,83 2018 | BI plus TAU (53) vs TAU (53) | UK | 10-18 | Transdiagnostic |

| Pineda et al,84 2013 | FT (24) vs TAU (24) | Australia | 12-17 | Transdiagnostic |

| Robinson et al,85 2012 | BI plus TAU (81) vs TAU (83) | Australia | 15-24 | Transdiagnostic |

| Rossouw et al,86 2012 | MBT (40) vs TAU (40) | UK | 13-18 | BPD |

| Santamarina-Perez et al,87 2020 | DBT (18) vs TAU (17) | Spain | 12-17 | Transdiagnostic |

| Schuppert et al,88 2009 | Group DBT (23) vs TAU (20) | Netherlands | 14-19 | BPD |

| Schuppert et al,89 2012 | Group DBT (54) vs TAU (55) | Netherlands | 14-19 | BPD |

| Sinyor et al,90 2020 | CBT (12) vs ST (12) | Canada | 16-26 | Transdiagnostic |

| Tang et al,91 2009 | IPT (35) vs TAU (38) | Taiwan | 12-18 | Transdiagnostic |

| Van Voorhees et al,92 2009 | MI (42) vs TAU (40) | US | 14-21 | Transdiagnostic |

| Wharff et al,93 2019 | FT (68) vs TAU (71) | US | 13-18 | Transdiagnostic |

| Wood et al,94 2001 | Group ET (32) vs TAU (37) | UK | 12-16 | Transdiagnostic |

| Yen et al,95 2019 | FT (27) vs TAU (27) | US | 12-18 | Transdiagnostic |

Abbreviations: BI, brief intervention; BPD, borderline personality disorder; CAT, cognitive analytic therapy; CBT, cognitive behavioral therapy; DBT, dialectical behavioral therapy; ET, eclectic therapy; EUC, enhanced usual care; FT, family-based therapy; IPT, interpersonal therapy; MBT, mentalization-based therapy; MDT, mode deactivation therapy; ST, supportive therapy; STPP, short-term psychoanalytic psychotherapy; TAU, treatment as usual; UK, United Kingdom; WLC, wait-list control group.

Figure 2. Network Plot of Eligible Psychotherapy Comparisons for Retention in Treatment.

Line width corresponds with the number of clinical trials comparing psychotherapy pairs. BI indicates brief intervention; CAT, cognitive analytic therapy; CBT, cognitive behavioral therapy; DBT, dialectical behavioral therapy; ET, eclectic therapy; FT, family-based therapy; IPT, interpersonal therapy; MBT, mentalization-based therapy; MDT, mode deactivation therapy; ST, supportive therapy; STPP, short-term psychoanalytic psychotherapy; TAU, treatment as usual; and WLC, wait-list control group.

Risk of Bias

With regard to risk of bias within studies, most of the 44 RCTs reported adequate randomization (39 studies), adequate allocation concealment (33 studies), and blinded outcome assessors (36 studies). Only 27 RCTs were preregistered, and only 13 RCTs provided published protocols; 31 studies therefore had a high risk of bias for selective reporting. The risk of incomplete outcome reporting was increased in 11 RCTs because of insufficient details on attrition. Most RCTs reported information on funding (41 studies) and therapist adherence or fidelity (28 studies). However, a high risk of allegiance bias was found in 38 RCTs, and a high risk of attention bias was found in at least 10 RCTs (the risk of attention bias was unclear in an additional 27 studies). As a consequence, a high overall risk of bias was present in all 44 RCTs (eTable 3 in the Supplement).

To evaluate risk of bias across studies, we downgraded the quality of evidence for all outcomes owing to the high risk of bias in all included RCTs. We also downgraded the overall quality of evidence because of high heterogeneity in suicidal ideation and mood symptoms and imprecision for psychotherapies that had few representative RCTs (eg, mode deactivation therapy and short-term psychoanalytic psychotherapy had only 1 representative RCT each). Although inconsistency was low, publication bias was found for self-harm frequency at the end of treatment (Table 2).

Table 2. Network Meta-analysis Indices.

| Variable | No. of studies | No. of treatments | No. of pairwise comparisons | τ2a | I2, %b | Q betweenc | P value for Q betweend | Egger P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retention in treatment | 44 | 13 | 46 | 0.15 | 32.6 | 3.06 | .38 | .21 |

| Study withdrawals | 44 | 13 | 46 | 0.16 | 33.7 | 2.95 | .40 | .23 |

| End of treatment | ||||||||

| Self-harm | 16 | 10 | 18 | 0.09 | 14.5 | 5.66 | .06 | .01 |

| Suicidal ideation | 31 | 12 | 31 | 0.17 | 81.8 | 0.65 | .72 | .24 |

| Mood | 28 | 13 | 30 | 0.12 | 75.6 | 3.59 | .17 | .12 |

| Follow-up | ||||||||

| Self-harm | 25 | 10 | 27 | <0.01 | 1.2 | 4.40 | .11 | .07 |

| Suicidal ideation | 19 | 11 | 19 | 0.63 | 94.9 | 0.07 | .80 | .53 |

| Mood | 19 | 12 | 21 | 0.06 | 71.4 | <0.01 | .97 | .05 |

Heterogeneity between designs.

Heterogeneity within designs.

Inconsistency between designs.

Significance of heterogeneity for Q-between statistic.

Synthesis of Findings

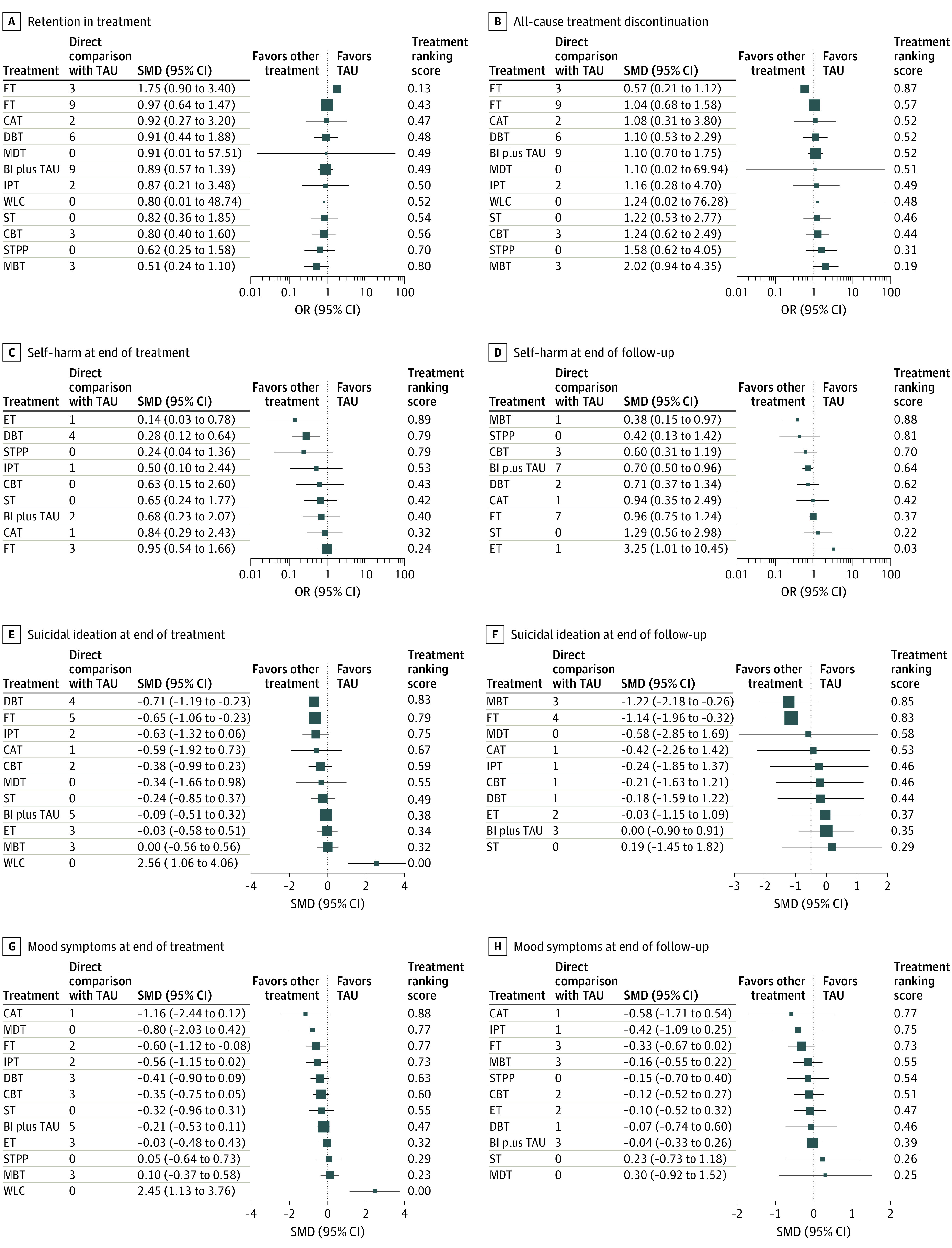

None of the investigated psychotherapies were associated with more study withdrawals compared with treatment as usual (Figure 3A and Figure 3B). However, efficacy was inconsistent across outcomes and psychotherapies. For example, eclectic therapy and DBT were associated with reductions in self-harm at the end of treatment (OR, 0.14 [95% CI, 0.03-0.78] for eclectic therapy and 0.28 [95% CI, 0.12-0.64] for DBT) (Figure 3C), while DBT and family-based therapy were associated with reductions in suicidal ideation at the end of treatment (Cohen d SMD, −0.71 [95% CI, −1.19 to −0.23] for DBT and −0.65 [95% CI, −1.06 to −0.23] for family-based therapy) compared with treatment as usual (Figure 3E). For depressive symptoms, only family-based therapy was associated with reductions in symptom severity at the end of treatment (Cohen d SMD, −0.60; 95% CI, −1.12 to −0.08) (Figure 3G).

Figure 3. Forest Plots of Treatment Acceptability Across All Clinical Trials in Network Meta-analysis.

All psychotherapies were compared with treatment as usual (TAU) using a random-effects model. For treatment ranking score, treatments at the top of the plots have higher ranking. OR indicates odds ratio; SMD, Cohen d standardized mean difference. All other definitions appear in the Figure 2 caption.

In extended follow-up, only MBT and brief intervention plus treatment as usual were associated with decreases in self-harm (OR, 0.38 [95% CI, 0.15-0.97] for MBT and 0.70 [95% CI, 0.50-0.96] for brief intervention plus treatment as usual) (Figure 3D), and only MBT and family-based therapy were associated with reductions in suicidal ideation (Cohen d SMD, −1.22 [95% CI, −2.18 to −0.26] for MBT and −1.14 [95% CI, −1.96 to −0.32] for family-based therapy) compared with treatment as usual (Figure 3F). None of the investigated therapies were associated with improvements in depressive symptoms over longer follow-up periods (Figure 3H). Participants in the wait-list control groups experienced worsening conditions, with increases in self-harm, mood symptoms, and suicidal ideation compared with participants receiving treatment as usual.

Discussion

Although the present NMA found that most psychotherapies were reasonably well tolerated and some psychotherapies indicated efficacy for particular measures of self-harm or suicidality, caution is recommended to avoid overinterpretation of these findings owing to low RCT quality, lack of consistency across outcome measures and treatment periods, and publication bias. When significant, most psychotherapies had small to medium effects compared with treatment as usual. Substantial reductions in self-harm and suicidal behavior were often observed in both the treatment and control groups, and group differences were subsequently small and nonsignificant for many RCTs.

The present NMA is not the first, and is unlikely to be the last, study to review psychotherapeutic efficacy for self-harm and suicidality among children and adolescents.8,9,15,16,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103 Although the present review did not focus on a specific clinical sample, relevant insights can be drawn from studies of adolescents with particular diagnoses, such as BPD. For example, Wong et al104 reported that a range of psychotherapies, including DBT and MBT, were associated with short-term, but not long-term, reductions in BPD symptomatology. However, as in previous reviews, Wong et al104 observed diminishing therapeutic efficacy over time, as psychotherapy effect sizes decreased during follow-up relative to the end of treatment. In addition, the clinical trials included in the review by Wong et al104 were of varying lengths and reported variable outcome measures for different dimensions of BPD symptomatology and functioning, which introduced several limitations in the formulation of firmer conclusions about the relative benefits of other therapies. In the present NMA, decreasing efficacy during follow-up compared with the end of treatment was also observed. Although it was more challenging to directly assess this pattern in the present NMA because of the varying numbers of studies reporting data on end of treatment and follow-up for particular psychotherapies, this challenge is not unique to our review.

Most previous meta-analyses of psychotherapies for children and adolescents with suicidal behaviors have identified similar limitations, highlighting the need for additional research and large-scale RCTs.2 Conducting research on self-harm and suicidal behavior among adolescents is intrinsically challenging because of the distinct trajectory of self-harm, the transient nature of some suicidal behaviors, and the nature of control interventions, which can often confer therapeutic benefits.2 Despite these challenges, the present review does not intend to downgrade the overall utility of psychotherapies, which remain useful for the treatment of a range of mental disorders, often as first-line interventions. However, the diverse array of psychotherapies and their evaluation in individual RCTs produced methodological challenges in creating a clear hierarchy of treatment rankings, which was the intended aim of this review. In part, the most challenging aspect of this review was synthesizing the data across a range of diverse RCTs that explored different psychotherapeutic modalities. Thus, the high risk of bias in the individual RCTs of psychotherapies for self-harm and suicidality among children and adolescents may have had implications for the findings.

Several approaches have emerged in studies of child and adolescent psychiatry that may support future comparative effectiveness research involving psychotherapies for self-harm. For example, a 2021 review by Jørgensen et al18 extended previous meta-analyses of BPD studies by conducting a trial sequential analysis, which aids the interpretation of meta-analyses involving sparse data and helps to address type 1 and type 2 errors. An alternative approach involves individual participant-level analyses and comprises pooling individual-level data to arrive at a single estimate of a treatment’s efficacy rather than a summary of aggregate RCT-level estimates. As a consequence, using data from large longer-term observational studies, such as phase 4 clinical trials, could be another option, which may also provide more real-world estimates of treatment effectiveness rather than efficacy.105

Strengths and Limitations

This study has strengths. To our knowledge, this review is the first to apply NMA to evaluate psychotherapies for the treatment of self-harm and suicidality among children and adolescents. Given the abundance of single-treatment RCTs and the shortage of head-to-head RCTs, the use of NMAs can provide a novel approach to synthesizing knowledge with the data available.106,107

This study also has several limitations. Although NMA is a powerful tool for comparative effectiveness research, it can produce misleading results when misapplied or misinterpreted. Most of our evidence relied on indirect treatment comparisons; when using head-to-head comparisons, indirect observations are more susceptible to bias. For a subset of psychotherapies (eg, mode deactivation therapy, short-term psychoanalytic psychotherapy, and supportive therapy), the availability of few RCTs and the use of small samples creates imprecise and potentially underpowered estimates. Although we pooled studies regardless of diagnostic classification to maximize statistical power, the findings of this review are less generalizable to specific clinical populations, such as adolescents with BPD.108,109 As a consequence, high heterogeneity was observed in some outcomes; however, given the lack of standardized protocols for RCTs investigating psychotherapy, this heterogeneity was, to a certain extent, unavoidable and not a specific limitation of this review.110 Although the RCTs examining family-based therapy were similar, the number of sessions ranged from 1 to 12; this difference may have produced additional heterogeneity. The duration of psychotherapy is another possible source of heterogeneity. We used the random-effects model to estimate effect sizes across different instruments measuring suicidality or depression, and we assumed that these instruments measured the same construct. However, this assumption was not definitively assessed and could have increased heterogeneity.

In addition to the challenges inherent in blinded clinical trials of psychotherapies,111 the risk of bias in individual RCTs was high because of other factors, particularly allegiance,112 selective reporting, and incomplete outcome reporting biases. Response and social desirability biases could have produced biased self-reported subjective measures, to which self-harm and suicidal ideation are particularly susceptible.113 Despite an extensive search, we may have missed relevant RCTs, given the publication bias in one of our primary outcomes. Although we did not detect network-level publication bias for most other outcomes, individual psychotherapies may have been subject to publication bias, as only 1 study was conducted for some interventions (eg, mode deactivation therapy and short-term psychoanalytic psychotherapy). Therapy-comparator differences could have been diminished by the active therapeutic nature of some comparator conditions, such as treatment as usual and enhanced usual care, which often provide unstructured psychotherapy sessions independent of a particular psychological modality.2

Conclusions

Although the findings of this review suggest that some psychotherapies are well tolerated and have some efficacy for specific measures of self-harm or suicidality, the estimates indicated that the evidence quality was low to very low for most psychotherapies. A lack of consistent evidence precludes a definitive hierarchy of treatments and suggests a need for additional high-quality RCTs.

eMethods. Network Meta-analysis Code

eTable 1. Psychotherapy Definitions

eTable 2. Search Strategy

eTable 3. Risk of Bias

eReferences

References

- 1.Klonsky ED, Victor SE, Saffer BY. Nonsuicidal self-injury: what we know, and what we need to know. Can J Psychiatry. 2014;59(11):565-568. doi: 10.1177/070674371405901101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kothgassner OD, Robinson K, Goreis A, Ougrin D, Plener PL. Does treatment method matter? a meta-analysis of the past 20 years of research on therapeutic interventions for self-harm and suicidal ideation in adolescents. Borderline Personal Disord Emot Dysregul. 2020;7(1):9. doi: 10.1186/s40479-020-00123-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campisi SC, Carducci B, Akseer N, Zasowski C, Szatmari P, Bhutta ZA. Suicidal behaviours among adolescents from 90 countries: a pooled analysis of the global school-based student health survey. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1102. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09209-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McLoughlin AB, Gould MS, Malone KM. Global trends in teenage suicide: 2003-2014. QJM. 2015;108(10):765-780. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcv026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hawton K, Saunders KEA, O’Connor RC. Self-harm and suicide in adolescents. Lancet. 2012;379(9834):2373-2382. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60322-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fontanella CA, Steelesmith DL, Brock G, Bridge JA, Campo JV, Fristad MA. Association of cannabis use with self-harm and mortality risk among youths with mood disorders. JAMA Pediatr. Published online January 19, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gobbi G, Atkin T, Zytynski T, et al. Association of cannabis use in adolescence and risk of depression, anxiety, and suicidality in young adulthood: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(4):426-434. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.4500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ougrin D, Tranah T, Stahl D, Moran P, Asarnow JR. Therapeutic interventions for suicide attempts and self-harm in adolescents: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2015;54(2):97-107. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2014.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iyengar U, Snowden N, Asarnow JR, Moran P, Tranah T, Ougrin D. A further look at therapeutic interventions for suicide attempts and self-harm in adolescents: an updated systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:583. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.MHASEF Research Team . The Mental Health of Children and Youth in Ontario: A Baseline Scorecard. Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences; 2015. Accessed April 3, 2020. https://www.ices.on.ca/flip-publication/MHASEF_Report_2015/files/assets/basic-html/index.html#4

- 11.MHASEF Research Team . The Mental Health of Children and Youth in Ontario: 2017 Scorecard. Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences; 2017. Accessed April 3, 2020. https://www.ices.on.ca/Publications/Atlases-and-Reports/2017/MHASEF

- 12.Centre for Suicide Prevention . Self-harm and suicide. Centre for Suicide Prevention; 2020. Accessed April 4, 2020. https://www.suicideinfo.ca/resource/self-harm-and-suicide/

- 13.Klonsky ED, Glenn CR. Resisting urges to self-injure. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2008;36(2):211-220. doi: 10.1017/S1352465808004128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Renaud J, Berlim MT, Séguin M, McGirr A, Tousignant M, Turecki G. Recent and lifetime utilization of health care services by children and adolescent suicide victims: a case-control study. J Affect Disord. 2009;117(3):168-173. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hawton K, Witt KG, Taylor Salisbury TL, et al. Interventions for self-harm in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(12):CD012013. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robinson J, Hetrick SE, Martin C. Preventing suicide in young people: systematic review. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2011;45(1):3-26. doi: 10.3109/00048674.2010.511147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Storebø OJ, Stoffers-Winterling JM, Völlm BA, et al. Psychological therapies for people with borderline personality disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;5(5):CD012955. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012955.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jørgensen MS, Storebø OJ, Stoffers-Winterling JM, Faltinsen E, Todorovac A, Simonsen E. Psychological therapies for adolescents with borderline personality disorder (BPD) or BPD features—a systematic review of randomized clinical trials with meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. PLoS One. 2021;16(1):e0245331. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0245331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miura T, Noma H, Furukawa TA, et al. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of pharmacological treatments in the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1(5):351-359. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70314-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yildiz A, Vieta E, Correll CU, Nikodem M, Baldessarini RJ. Critical issues on the use of network meta-analysis in psychiatry. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2014;22(6):367-372. doi: 10.1097/HRP.0000000000000025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet. 2018;391(10128):1357-1366. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32802-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jansen JP, Naci H. Is network meta-analysis as valid as standard pairwise meta-analysis? it all depends on the distribution of effect modifiers. BMC Med. 2013;11(1):159. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hutton B, Salanti G, Caldwell DM, et al. The PRISMA extension statement for reporting of systematic reviews incorporating network meta-analyses of health care interventions: checklist and explanations. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(11):777-784. doi: 10.7326/M14-2385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000100. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media website. 2018. Accessed July 19, 2019. https://rrchnm.org/

- 26.Covidence systematic review software. Veritas Health Innovation; 2019. Accessed July 19, 2019. https://www.covidence.org/

- 27.Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, et al. ; Cochrane Bias Methods Group; Cochrane Statistical Methods Group . The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sedgwick P, Marston L. How to read a funnel plot in a meta-analysis. BMJ. 2015;351:h4718. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h4718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629-634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, et al. ; GRADE Working Group . GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336(7650):924-926. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lipsey MW, Wilson DB. Practical Meta-analysis. Sage Publications; 2001. Hedrick TE, Bickman L, Rog DJ, eds. Applied Social Research Methods Series; vol 49. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bahji A, Ermacora D, Stephenson C, Hawken ER, Vazquez G. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of pharmacological treatments for the treatment of acute bipolar depression: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2020;269:154-184. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.03.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bahji A, Ermacora D, Stephenson C, Hawken ER, Vazquez G. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of adjunctive pharmacotherapies for acute bipolar depression: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Can J Psychiatry. 2021;66(3):274-288. Published online November 11, 2020. doi: 10.1177/0706743720970857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bahji A, Meyyappan AC, Hawken ER. Efficacy and acceptability of cannabinoids for anxiety disorders in adults: a systematic review & meta-analysis. J Psychiatr Res. 2020;129:257-264. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.07.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bahji A, Stephenson C, Tyo R, Hawken ER, Seitz DP. Prevalence of cannabis withdrawal symptoms among people with regular or dependent use of cannabinoids: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(4):e202370. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.2370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bahji A, Vazquez GH, Zarate CA Jr. Comparative efficacy of racemic ketamine and esketamine for depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2021;278:542-555. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.09.071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wong J, Bahji A, Khalid-Khan S. Systematic review and meta-analyses of psychotherapies for adolescents with subclinical and borderline personality disorder: a reply to the commentary by Jørgensen, Storebø, and Simonsen. Can J Psychiatry. 2020;65(5):356-357. doi: 10.1177/0706743719898328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.RStudio: integrated development for R. RStudio; 2020. Accessed October 15, 2020. https://www.rstudio.com/

- 40.Rücker G, Krahn U, König J, Efthimiou O, Schwarzer G. Netmeta: network meta-analysis using frequentist methods. Version 1.3-0. CRAN.R Project; 2019. Accessed October 8, 2019. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/netmeta/index.html

- 41.Salanti G. Indirect and mixed-treatment comparison, network, or multiple-treatments meta-analysis: many names, many benefits, many concerns for the next generation evidence synthesis tool. Res Synth Methods. 2012;3(2):80-97. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Salanti G, Higgins JPT, Ades AE, Ioannidis JPA. Evaluation of networks of randomized trials. Stat Methods Med Res. 2008;17(3):279-301. doi: 10.1177/0962280207080643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huhn M, Nikolakopoulou A, Schneider-Thoma J, et al. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 32 oral antipsychotics for the acute treatment of adults with multi-episode schizophrenia: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet. 2019;394(10202):939-951. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31135-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rouse B, Chaimani A, Li T. Network meta-analysis: an introduction for clinicians. Intern Emerg Med. 2017;12(1):103-111. doi: 10.1007/s11739-016-1583-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557-560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR. A basic introduction to fixed-effect and random-effects models for meta-analysis. Res Synth Methods. 2010;1(2):97-111. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jørgensen MS, Storebø OJ, Bo S, et al. Mentalization-based treatment in groups for adolescents with borderline personality disorder: 3- and 12-month follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. Published online May 9, 2020. doi: 10.1007/s00787-020-01551-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mehlum L, Ramberg M, Tørmoen AJ, et al. Dialectical behavior therapy compared with enhanced usual care for adolescents with repeated suicidal and self-harming behavior: outcomes over a one-year follow-up. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016;55(4):295-300. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2016.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mehlum L, Ramleth RK, Tørmoen AJ, et al. Long term effectiveness of dialectical behavior therapy versus enhanced usual care for adolescents with self-harming and suicidal behavior. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2019;60(10):1112-1122. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.13077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ougrin D, Boege I, Stahl D, Banarsee R, Taylor E. Randomised controlled trial of therapeutic assessment versus usual assessment in adolescents with self-harm: 2-year follow-up. Arch Dis Child. 2013;98(10):772-776. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2012-303200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cottrell DJ, Wright-Hughes A, Eisler I, et al. Longer-term effectiveness of systemic family therapy compared with treatment as usual for young people after self-harm: an extended follow up of pragmatic randomised controlled trial. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;18:100246. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2019.100246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Beck E, Bo S, Jørgensen MS, et al. Mentalization-based treatment in groups for adolescents with borderline personality disorder: a randomized controlled trial. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2020;61(5):594-604. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.13152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cottrell DJ, Wright-Hughes A, Collinson M, et al. Effectiveness of systemic family therapy versus treatment as usual for young people after self-harm: a pragmatic, phase 3, multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(3):203-216. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30058-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mehlum L, Tørmoen AJ, Ramberg M, et al. Dialectical behavior therapy for adolescents with repeated suicidal and self-harming behavior: a randomized trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;53(10):1082-1091. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2014.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ougrin D, Zundel T, Ng A, Banarsee R, Bottle A, Taylor E. Trial of therapeutic assessment in London: randomised controlled trial of therapeutic assessment versus standard psychosocial assessment in adolescents presenting with self-harm. Arch Dis Child. 2011;96(2):148-153. doi: 10.1136/adc.2010.188755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Alavi A, Sharifi B, Ghanizadeh A, Dehbozorgi G. Effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy in decreasing suicidal ideation and hopelessness of the adolescents with previous suicidal attempts. Iran J Pediatr. 2013;23(4):467-472. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Apsche JA, Bass CK, Houston MA. A one year study of adolescent males with aggression and problems of conduct and personality: a comparison of MDT and DBT. Int J Behav Consult Ther. 2006;2(4):544-552. doi: 10.1037/h0101006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Asarnow JR, Baraff LJ, Berk M, et al. An emergency department intervention for linking pediatric suicidal patients to follow-up mental health treatment. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62(11):1303-1309. doi: 10.1176/ps.62.11.pss6211_1303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Asarnow JR, Hughes JL, Babeva KN, Sugar CA. Cognitive-behavioral family treatment for suicide attempt prevention: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;56(6):506-514. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.03.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Britton WB, Lepp NE, Niles HF, Rocha T, Fisher NE, Gold JS. A randomized controlled pilot trial of classroom-based mindfulness meditation compared to an active control condition in sixth-grade children. J Sch Psychol. 2014;52(3):263-278. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2014.03.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chanen AM, Jackson HJ, McCutcheon LK, et al. Early intervention for adolescents with borderline personality disorder using cognitive analytic therapy: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;193(6):477-484. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.048934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cooney E; New Zealand Ministry of Health; Wise Group (N.Z.), Te Pou o te Whakaaro Nui . Feasibility of Evaluating DBT for Self-harming Adolescents: A Small Randomised Controlled Trial. Te Pou o Te Whakaaro Nui–The National Centre of Mental Health Research and Workforce Development; 2010. Accessed September 12, 2020. https://www.worldcat.org/title/feasibility-of-evaluating-dbt-for-self-harming-adolescents-a-small-randomised-controlled-trial/oclc/679320661

- 63.Cotgrove A, Zirinsky L, Black D, Weston D. Secondary prevention of attempted suicide in adolescence. J Adolesc. 1995;18(5):569-577. doi: 10.1006/jado.1995.1039 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Diamond GS, Wintersteen MB, Brown GK, et al. Attachment-based family therapy for adolescents with suicidal ideation: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49(2):122-131. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2009.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Diamond GS, Kobak RR, Krauthamer Ewing ES, et al. A randomized controlled trial: attachment-based family and nondirective supportive treatments for youth who are suicidal. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2019;58(7):721-731. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2018.10.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Donaldson D, Spirito A, Esposito-Smythers C. Treatment for adolescents following a suicide attempt: results of a pilot trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44(2):113-120. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200502000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Esposito-Smythers C, Spirito A, Kahler CW, Hunt J, Monti P. Treatment of co-occurring substance abuse and suicidality among adolescents: a randomized trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2011;79(6):728-739. doi: 10.1037/a0026074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Esposito-Smythers C, Hadley W, Curby TW, Brown LK. Randomized pilot trial of a cognitive-behavioral alcohol, self-harm, and HIV prevention program for teens in mental health treatment. Behav Res Ther. 2017;89:49-56. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2016.11.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gleeson JFM, Chanen A, Cotton SM, Pearce T, Newman B, McCutcheon L. Treating co-occurring first-episode psychosis and borderline personality: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2012;6(1):21-29. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7893.2011.00306.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Goodyer IM, Reynolds S, Barrett B, et al. Cognitive behavioural therapy and short-term psychoanalytical psychotherapy versus a brief psychosocial intervention in adolescents with unipolar major depressive disorder (IMPACT): a multicentre, pragmatic, observer-blind, randomised controlled superiority trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4(2):109-119. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30378-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Green JM, Wood AJ, Kerfoot MJ, et al. Group therapy for adolescents with repeated self harm: randomised controlled trial with economic evaluation. BMJ. 2011;342:d682. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Griffiths H, Duffy F, Duffy L, et al. Efficacy of mentalization-based group therapy for adolescents: the results of a pilot randomised controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry. 2019;19(1):167. doi: 10.1186/s12888-019-2158-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Harrington R, Kerfoot M, Dyer E, et al. Randomized trial of a home-based family intervention for children who have deliberately poisoned themselves. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37(5):512-518. doi: 10.1016/S0890-8567(14)60001-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hazell PL, Martin G, Mcgill K, et al. Group therapy for repeated deliberate self-harm in adolescents: failure of replication of a randomized trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48(6):662-670. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181a0acec [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hetrick SE, Yuen HP, Bailey E, et al. Internet-based cognitive behavioural therapy for young people with suicide-related behaviour (Reframe-IT): a randomised controlled trial. Evid Based Ment Health. 2017;20(3):76-82. doi: 10.1136/eb-2017-102719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hill RM, Pettit JW. Pilot randomized controlled trial of LEAP: a selective preventive intervention to reduce adolescents’ perceived burdensomeness. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2019;48(sup1)(suppl 1):S45-S56. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2016.1188705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kaess M, Edinger A, Fischer-Waldschmidt G, Parzer P, Brunner R, Resch F. Effectiveness of a brief psychotherapeutic intervention compared with treatment as usual for adolescent nonsuicidal self-injury: a single-centre, randomised controlled trial. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020;29(6):881-891. doi: 10.1007/s00787-019-01399-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kennard BD, Goldstein T, Foxwell AA, et al. As Safe As Possible (ASAP): a brief app-supported inpatient intervention to prevent postdischarge suicidal behavior in hospitalized, suicidal adolescents. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(9):864-872. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.17101151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.King CA, Kramer A, Preuss L, Kerr DCR, Weisse L, Venkataraman S. Youth-Nominated Support Team for suicidal adolescents (version 1): a randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74(1):199-206. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.1.199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.King CA, Klaus N, Kramer A, Venkataraman S, Quinlan P, Gillespie B. The Youth-Nominated Support Team–Version II for suicidal adolescents: a randomized controlled intervention trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77(5):880-893. doi: 10.1037/a0016552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.King CA, Gipson PY, Horwitz AG, Opperman KJ. Teen options for change: an intervention for young emergency patients who screen positive for suicide risk. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66(1):97-100. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201300347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.McCauley E, Berk MS, Asarnow JR, et al. Efficacy of dialectical behavior therapy for adolescents at high risk for suicide: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(8):777-785. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.1109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ougrin D, Corrigall R, Poole J, et al. Comparison of effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of an intensive community supported discharge service versus treatment as usual for adolescents with psychiatric emergencies: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(6):477-485. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30129-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Pineda J, Dadds MR. Family intervention for adolescents with suicidal behavior: a randomized controlled trial and mediation analysis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013;52(8):851-862. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Robinson J, Yuen HP, Gook S, et al. Can receipt of a regular postcard reduce suicide-related behaviour in young help seekers? a randomized controlled trial. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2012;6(2):145-152. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7893.2011.00334.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rossouw TI, Fonagy P. Mentalization-based treatment for self-harm in adolescents: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51(12):1304-1313. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.09.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Santamarina-Perez P, Mendez I, Singh MK, et al. Adapted dialectical behavior therapy for adolescents with a high risk of suicide in a community clinic: a pragmatic randomized controlled trial. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2020;50(3):652-667. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Schuppert HM, Giesen-Bloo J, van Gemert TG, et al. Effectiveness of an emotion regulation group training for adolescents—a randomized controlled pilot study. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2009;16(6):467-478. doi: 10.1002/cpp.637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Schuppert HM, Timmerman ME, Bloo J, et al. Emotion regulation training for adolescents with borderline personality disorder traits: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51(12):1314-1323. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sinyor M, Williams M, Mitchell R, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for suicide prevention in youth admitted to hospital following an episode of self-harm: a pilot randomized controlled trial. J Affect Disord. 2020;266:686-694. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.01.178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Tang TC, Jou SH, Ko CH, Huang SY, Yen CF. Randomized study of school-based intensive interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed adolescents with suicidal risk and parasuicide behaviors. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2009;63(4):463-470. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2009.01991.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Van Voorhees BW, Fogel J, Reinecke MA, et al. Randomized clinical trial of an internet-based depression prevention program for adolescents (Project CATCH-IT) in primary care: 12-week outcomes. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2009;30(1):23-37. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3181966c2a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wharff EA, Ginnis KB, Ross AM, White EM, White MT, Forbes PW. Family-based crisis intervention with suicidal adolescents: a randomized clinical trial. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2019;35(3):170-175. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000001076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wood A, Trainor G, Rothwell J, Moore A, Harrington R. Randomized trial of group therapy for repeated deliberate self-harm in adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40(11):1246-1253. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200111000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Yen S, Spirito A, Weinstock LM, Tezanos K, Kolobaric A, Miller I. Coping long term with active suicide in adolescents: results from a pilot randomized controlled trial. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2019;24(4):847-859. doi: 10.1177/1359104519843956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Robinson J, Bailey E, Witt K, et al. What works in youth suicide prevention? a systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine. 2018;4-5:52-91. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2018.10.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Dray J, Bowman J, Campbell E, et al. Systematic review of universal resilience-focused interventions targeting child and adolescent mental health in the school setting. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;56(10):813-824. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.07.780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Fonagy P, Target M, Cottrell D, et al. What Works for Whom? A Critical Review of Treatments for Children and Adolescents. 1st ed. Guilford Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Glenn CR, Franklin JC, Nock MK. Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for self-injurious thoughts and behaviors in youth. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2015;44(1):1-29. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2014.945211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Merz J, Schwarzer G, Gerger H. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of pharmacological, psychotherapeutic, and combination treatments in adults with posttraumatic stress disorder: a network meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(9):904-913. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.0951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Milner A, Spittal MJ, Kapur N, Witt K, Pirkis J, Carter G. Mechanisms of brief contact interventions in clinical populations: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16(1):194. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-0896-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Weisz JR, Kuppens S, Ng MY, et al. What five decades of research tells us about the effects of youth psychological therapy: a multilevel meta-analysis and implications for science and practice. Am Psychol. 2017;72(2):79-117. doi: 10.1037/a0040360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Werner-Seidler A, Perry Y, Calear AL, Newby JM, Christensen H. School-based depression and anxiety prevention programs for young people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2017;51:30-47. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2016.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Wong J, Bahji A, Khalid-Khan S. Psychotherapies for adolescents with subclinical and borderline personality disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Can J Psychiatry. 2020;65(1):5-15. doi: 10.1177/0706743719878975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Cesana BM, Biganzoli EM. Phase IV studies: some insights, clarifications, and issues. Curr Clin Pharmacol. 2018;13(1):14-20. doi: 10.2174/1574884713666180412152949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Eccleston C, Fisher E, Craig L, Duggan GB, Rosser BA, Keogh E. Psychological therapies (internet-delivered) for the management of chronic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2014(2):CD010152. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010152.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Haugh S, O’Connor L, Slattery B, et al. The relative effectiveness of psychotherapeutic techniques and delivery modalities for chronic pain: a protocol for a systematic review and network meta-analysis. HRB Open Res. 2020;2:25. doi: 10.12688/hrbopenres.12953.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Willis BH, Riley RD. Measuring the statistical validity of summary meta-analysis and meta-regression results for use in clinical practice. Stat Med. 2017;36(21):3283-3301. doi: 10.1002/sim.7372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Riley RD, Jackson D, Salanti G, et al. Multivariate and network meta-analysis of multiple outcomes and multiple treatments: rationale, concepts, and examples. BMJ. 2017;358:j3932. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j3932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Thorlund K, Mills EJ. Sample size and power considerations in network meta-analysis. Syst Rev. 2012;1(1):41. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-1-41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Shean G. Limitations of randomized control designs in psychotherapy research. Adv Psychiatry. 2014;2014:561452. doi: 10.1155/2014/561452 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Munder T, Flückiger C, Gerger H, Wampold BE, Barth J. Is the allegiance effect an epiphenomenon of true efficacy differences between treatments? a meta-analysis. J Couns Psychol. 2012;59(4):631-637. doi: 10.1037/a0029571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Rosenman R, Tennekoon V, Hill LG. Measuring bias in self-reported data. Int J Behav Healthc Res. 2011;2(4):320-332. doi: 10.1504/IJBHR.2011.043414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods. Network Meta-analysis Code

eTable 1. Psychotherapy Definitions

eTable 2. Search Strategy

eTable 3. Risk of Bias

eReferences